Abstract

In this study, we numerically investigate the influence of thermal gradients on the growth and intensification of vortices formed within a rotating cylinder subjected to inhomogeneous cooling at the top or inhomogeneous heating at the bottom. The presence of horizontal thermal inhomogeneities at the upper and lower boundaries determines whether the vortex originates near the top or the bottom of the domain. Moreover, the magnitude of both horizontal and vertical thermal gradients plays a critical role in the vortex’s intensification, vertical stretching, and overall development. The observed phenomena are interpreted through a force balance analysis. Increasing the ambient rotation rate leads to the emergence of periodic structures, such as tilted or double vortices, which also undergo intensification and stretching as thermal gradients increase. These findings highlight the importance of thermal boundary conditions in shaping vortical structures and may contribute to a deeper understanding of the genesis, morphology, and intensification mechanisms of thermoconvective vortices.

1. Introduction

The processes involved in the formation, persistence, and dissipation of atmospheric vortices—such as tornadoes—are highly complex and remain incompletely understood [1,2].

There are different theories for tornadogenesis. While numerous observational studies [3,4,5] and numerical works [6,7] support the “top-down” theory—where tornadoes originate aloft and develop downward—other investigations [5,8,9,10] have documented rotation initiating near the surface and evolving upward, or forming simultaneously across a substantial depth of the lower troposphere. Recent research on tornadogenesis in supercells suggests that rotation often begins close to the ground or emerges concurrently along the entire vertical column [9,10,11].

To explore the fundamental mechanisms behind such atmospheric phenomena, the rotating Rayleigh–Bénard convection (RRBC) model is frequently employed. This model consists of a fluid contained in a rotating cylinder, heated from below and cooled from above [12]. In this model the ambient rotation mimics the parent circulation within supercell tornado models.

Extensive studies have examined the dynamics in rotating fluids subjected to vertical temperature gradients [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. In Refs. [12,17,18] they investigate tornado-like vortices in Coriolis–Centrifugal convection regimes, highlighting the role of centrifugal buoyancy combined with the gravitational one in the production of vorticity within a tornado. Ref. [13] studies heat transport in the geostrophic regime of RRBC. In Ref. [14] they focus on non-Oberbeck–Boussinesq effects, and Ref. [15] presents a comprehensive review of RRBC, summarizing experimental and theoretical advances. In Ref. [16] centrifugal effects in rotating convection, including axisymmetric states and 3D instabilities, are analyzed.

There are also studies considering radial temperature gradients [19,20,21]. In Refs. [19,20], they explore turbulence and regime transitions in a differentially heated rotating annulus. In Ref. [21] the combined influence of horizontal thermal gradients at both the top and bottom boundaries, along with vertical temperature differences, is shown to affect the formation of traditional and reversed funnel-shaped vortices.

The majority of these works are set in a turbulent context, but works in laminar regimes have also been addressed [16,21].

In this paper, we numerically study the role that thermal gradients have in both the intensification of different vortical structures that appear depending on the ambient rotation rate (axisymmetric vortex, tilted vortex, and double vortex) and their vertical growth, bottom-up or top-down.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the physical configuration and presents a mathematical formulation of the problem in dimensionless terms. Section 3 provides a brief overview of the numerical implementation. In Section 4, the numerical results are discussed, including an analysis of the various vortical structures that emerge as the rotation rate changes and an examination of how horizontal and vertical thermal gradients influence both the vertical development and intensification of the vortex. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the main conclusions.

2. Formulation of the Problem

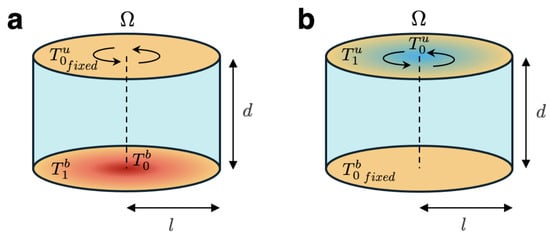

We consider a rotating cylindrical domain of radius l and height d, subjected to a rotation rate . We consider two different configurations:

- Case A: The thermal inhomogeneity is set at the bottom (Figure 1a).

Figure 1. Physical setup considered for each configuration. (a) A thermal inhomogeneity is set at the bottom. (b) A thermal inhomogeneity is set at the top.

Figure 1. Physical setup considered for each configuration. (a) A thermal inhomogeneity is set at the bottom. (b) A thermal inhomogeneity is set at the top. - Case B: The thermal inhomogeneity is imposed at the top boundary (Figure 1b).

In both configurations, horizontal and vertical thermal gradients are imposed. The vertical temperature difference is defined as . At the lower boundary, a central hot region is introduced using a Gaussian temperature profile (see dimensionless mathematical expression in Equation (6)), which reaches a maximum value at and the value at . A lateral thermal variation is introduced at the base of the cylinder, defined as . Similarly, at the upper boundary, a cold region is imposed at the center using another Gaussian temperature profile (see Equation (8)), with a minimum value at and a maximum value at . The horizontal temperature difference at the top is defined as . To characterize the relative strength of the horizontal gradients with respect to the vertical gradient, we introduce the dimensionless parameters and . In case A, the upper reference temperature is held constant, while in case B, the bottom temperature is fixed. In both cases, we denote the fixed reference temperature as .

The governing equations describe the evolution of the velocity field , temperature T, and pressure p. To nondimensionalize the system, we apply the following rescaling: , , and , where is the position vector, is the thermal diffusivity, is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, and is the mean density at temperature . From this point onward, the primes will be omitted, with the understanding that all fields are treated as dimensionless. The computational domain, expressed in cylindrical coordinates , is given as , where denotes the aspect ratio. The governing equations consist of the Navier–Stokes equations, which represent the conservation of mass and momentum, and the heat equation, which describes the conservation of energy. In dimensionless form (with primes now omitted) are

where the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation is used [22,23]. This approximation assumes constant properties for the fluid except for a linearly temperature-dependent density, i.e., , where is the coefficient of volume expansion and is the density at . The use of the Oberbeck–Boussinesq approximation is justified in this context, as compressibility effects are considered negligible for tornado-like vortices [24,25].

The operators in Equations (1)–(3) are expressed in cylindrical coordinates and denote the unit vector in the vertical z direction. Several dimensionless numbers are introduced to characterize the flow: the Prandtl number , the Ekman number , and the Rayleigh number , where is the coefficient of volume expansion and g is the gravitational acceleration.

We summarize next the boundary conditions considered:

At the lateral boundary, a rigid and thermally insulating wall is considered, with no-normal-flow and no-slip conditions imposed,

At both the top and bottom boundaries, no-normal-flow and free-slip conditions are applied

At the bottom, the temperature condition is

for configuration A and

for configuration B. At the top, the condition for the temperature is

for configuration B and

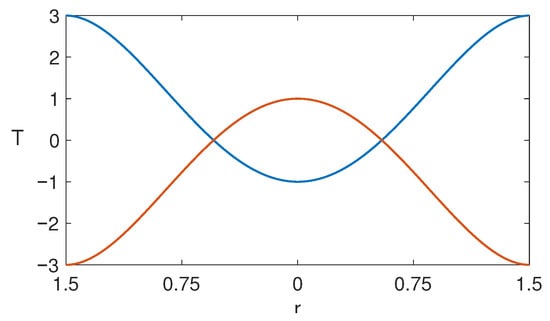

for configuration A. Figure 2 displays a temperature profile at the bottom for case A and at the top for case B.

Figure 2.

Dimensionless temperature profiles at the top (blue line) and at the bottom (red line).

The parameters and control the sharpness of the Gaussian temperature profiles at the top and bottom surfaces of the cylinder, respectively. Small values correspond to sharper, more localized thermal inhomogeneities, while larger values indicate broader distributions along the boundary surfaces. In our simulations, the Prandtl number is set to , which is representative of air, , and . In our simulations we consider and in case A, and and = 0 in case B.

3. Numerical Implementation

Equations (1)–(3), along with the boundary conditions (4)–(6) and (9) (case A) or (4) and (5), (7) and (8) (case B), are solved using direct numerical simulation. A second-order time-splitting scheme combined with spectral collocation is used to numerically solve the governing equations, as described and validated in Ref. [26]:

where n is the index for time.

The procedure consists of the following steps:

- Temperature update: The temperature field is computed using Equation (10).

- Pressure prediction: Applying the divergence operator ∇ to Equation (12) and using Equation (11), a preliminary pressure field is obtained.

- Velocity prediction: A predictor velocity field is calculated from Equation (12) using the predicted pressure .

- Correction step: The final velocity and pressure are obtained by solving the system:

For spatial discretization, a pseudo-spectral method is used, combining Fourier expansion in the azimuthal coordinate with Chebyshev collocation in the radial r and vertical z directions. Each field is expanded as follows:

where and are real and for , with being the complex conjugate of .

The coefficients are further expanded using Chebyshev polynomials:

where is the nth Chebyshev polynomial. We use evaluations at the Gauss–Lobatto collocation points for and for . To accommodate the Chebyshev collocation method, the computational domain is transformed to . Simulations are performed with , , and . In total, the problem is solved numerically on 44.352 nodes, providing a sufficient resolution for all tested Rayleigh numbers. We carried out the serial computations on a 3.6 GHz Intel Core i9 equipped with 128 GB of RAM (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA), using the scientific software package MATLAB (R2024b, The MathWorks, Inc., Natick, MA, USA). For the chosen discretization and a time step of , the time per iteration was 0.4831 s.

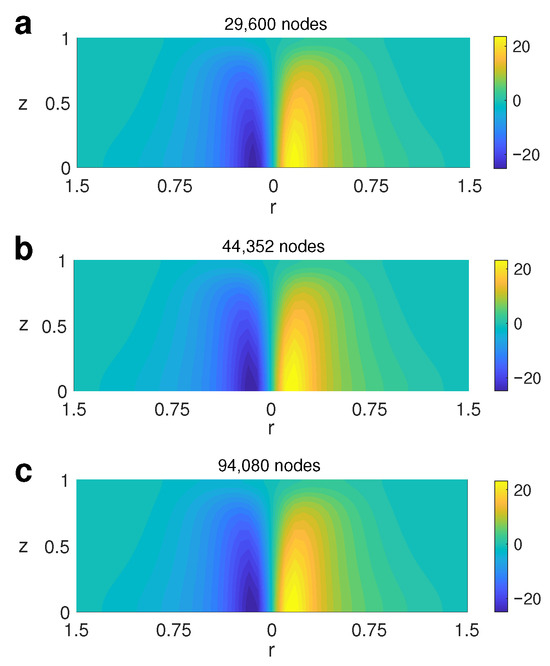

We have performed a mesh independence study, comparing solutions for different expansions in order to test the convergence of the numerical method. Figure 3 shows the profiles of the azimuthal velocity for case A, with , , and different numbers of nodes. As expected, no significant differences are found for the different expansions. Table 1 shows the relative differences between different numbers of nodes in the mesh for the maximum values of each velocity component. The relative difference for each expansion is calculated, taking, as a reference, the expansion with the largest number of nodes (94,080). The convergence is clearly observed as the number of nodes considered increases.

Figure 3.

Contour plot of the azimuthal velocity for case A with and for different numbers of mesh nodes. (a) 29,600 nodes; (b) 44,352 nodes; (c) 94,080 nodes.

Table 1.

Relative differences between different numbers of nodes in the mesh for the maximum values of the velocity components.

The solver has already been validated in Ref. [26] for a rotating cylindrical configuration under thermal gradients. In that work, we test the implemented code by reproducing some of the states arising in thermoconvective problems in a cylinder obtained by several authors using different numerical codes [27,28,29].

Our model considering an inhomogeneous heating at the bottom surface shows the transition from a one-cell vortex to a two-cell vortex when is increased [26,30], reproducing the laboratory experiments in Ref. [31] that show the progression of a vortex structure from a single cell to a two-cell vortex with a downdraft in the center as the swirl ratio (roughly speaking, the ratio of rotation strength to updraft strength) increases. Our numerical results exhibit a very similar behavior to the laboratory tornadoes described in Ref. [31].

4. Numerical Results

Our control parameter in the numerical experiments is the Rayleigh number . As we consider fixed parameters and , the increase in also implies an increase in the horizontal temperature gradients and .

As shown in Refs. [21,26], the setting of vertical and horizontal temperature gradients leads to the development of a vertical vortex. This vertical vortex, axisymmetric and stationary (AV), destabilizes to different periodic vortical structures when increases depending on the rate of the ambient rotation, i.e., depending on the value of .

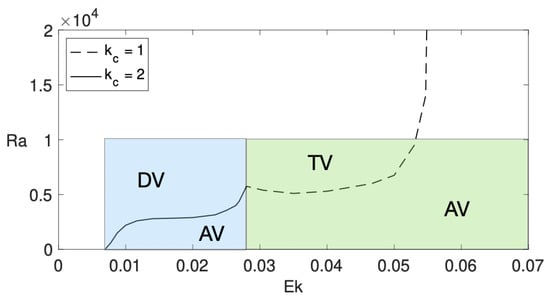

Figure 4 displays the bifurcation diagram in the plane Ra-Ek for case A. The bifurcation diagram for case B is analogous. As observed, there are three clearly differentiated regions, depending on : , , and . For the instability occurs through an oscillatory bifurcation of wave number (solid line), and for , the instability occurs through an oscillatory bifurcation of wave number (dashed line). Below the bifurcation lines the state found is axisymmetric.

Figure 4.

Thermoconvective bifurcation diagram as a function of the Ekman number and the Rayleigh number . The dashed line represents an oscillatory bifurcation with a critical wave number , while the solid line corresponds to an oscillatory bifurcation with . The diagram reveals the emergence of distinct flow structures: an axisymmetric vortex (AV), a tilted vortex (TV), and a double vortex (DV).

4.1. Non-Destabilizing Axisymmetric Vortex

For the axisymmetric vortex is very stable and does not destabilize when increases.

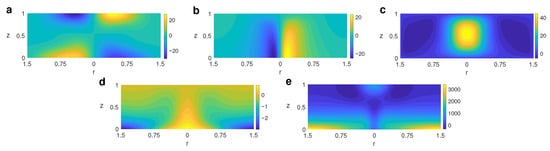

Figure 5 displays the vortex formed when the horizontal temperature gradient is considered at the bottom (case A) for and . The azimuthal movement is combined with an upward motion at the central part of the cell. The air moves towards the center of the cylinder at the bottom and away from it at the top. The hotter region in the central part of the cell coincides with a drop in pressure in that zone.

Figure 5.

Profiles of velocity components, temperature, and pressure of the vortex for and for case A, with thermal inhomogeneity at the bottom. (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) T; (e) p.

Figure 6 shows, for the same parameters, the case where the horizontal temperature gradient is set at the top, where the vortical structure develops. The azimuthal motion is now combined with a descending movement at the central cooler part of the cell, where a pressure gradient occurs. The air moves towards the center of the cylinder at the top, and away from it at the bottom.

Figure 6.

Profiles of velocity components, temperature, and pressure of the vortex for and for case B, with thermal inhomogeneity at the top. (a) ; (b) ; (c) ; (d) T; (e) p.

The effects of increasing the Rayleigh number, corresponding to enhanced temperature gradients, on this stable vortex are now investigated.

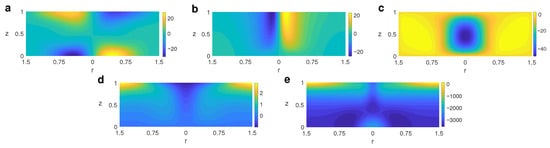

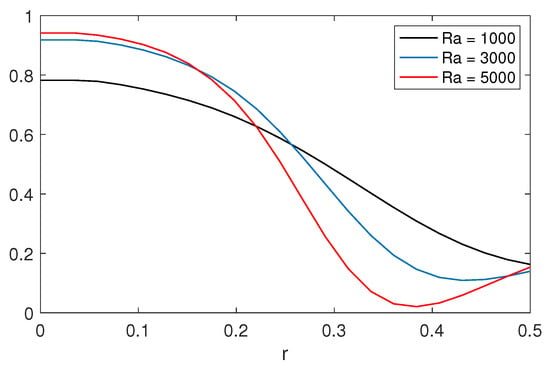

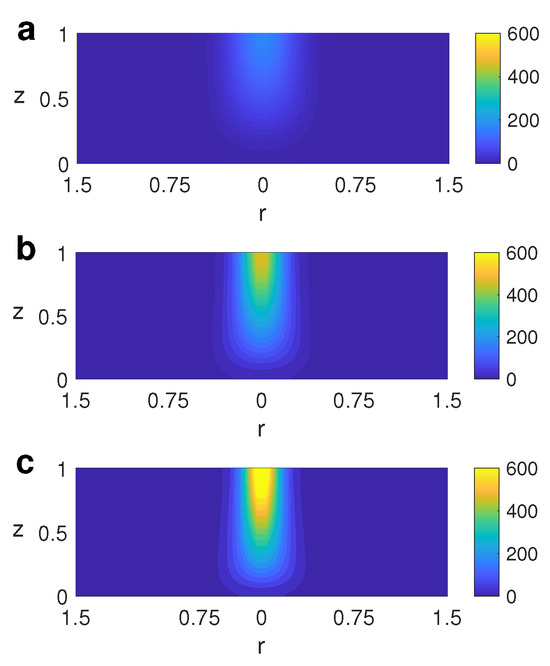

Figure 7 displays the profiles of the vertical component of the vorticity when is varied for the case where a thermal inhomogeneity is located at the bottom (case A). As is expected, the magnitude of the vertical vorticity increases with , which implies a more intense spin of the structure around the cylinder’s axis.

Figure 7.

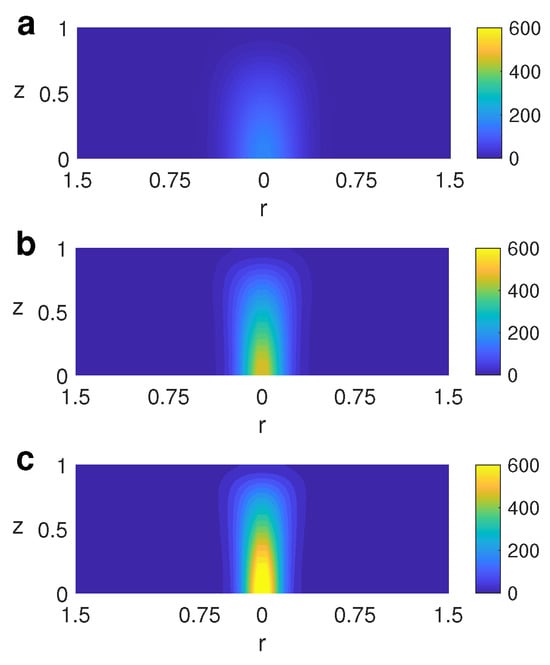

Profiles of the vertical component of the vorticity when is varied for case A for . From top to bottom: (a) ; (b) ; (c) .

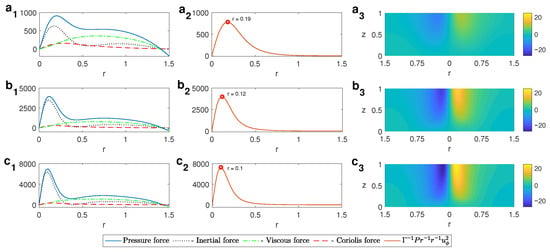

This intensification can be explained by taking a look, at lower z levels, at the terms from the radial component of the momentum equation: the pressure force , the Coriolis force , the inertial or friction force , and the viscous force . As can be seen in the left column in Figure 8 for and different values of , the positive radial pressure gradient is balanced by the Coriolis and inertial forces (the latter essentially corresponds to the centrifugal term displayed in the central column of Figure 8). As the thermal gradients increase, the radial pressure gradient increases, and so does the centrifugal force that balances it in the central region of the cell. This implies a more intense cyclonic motion close to the cylinder axis as the thermal gradients grow, leading, consequently, to a more intense vortex.

Figure 8.

Left column: profiles in the radial direction of the pressure gradient, the inertial force, the Coriolis force, and the viscous force for . Central column: radial profile of the centrifugal force for . Right column: contour plots of the azimuthal velocity in the r-z plane. From top to bottom: () ; () ; () ; . Case A for .

For this range of , the flow is in cyclostrophic balance. Figure 9 displays a plot of the degree of cyclostrophic balance as a function of , showing that the cyclostrophic fraction is approaching unity with increasing .

Figure 9.

Plot of the degree of cyclostrophic balance as a function of for case A for .

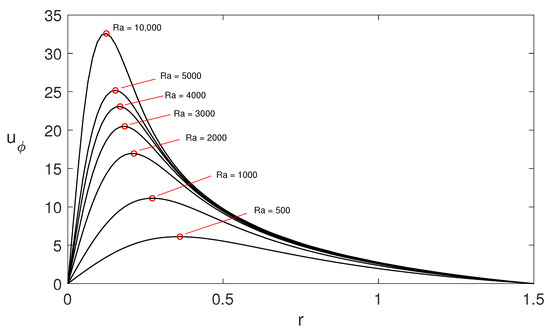

As the Rayleigh number increases—corresponding to stronger thermal forcing and vortex intensification—the radius of maximum centrifugal force and, thus, the radius of maximum azimuthal velocity (RMAV) undergo a noticeable contraction. This behavior is consistent with the diffusion of angular momentum, as illustrated in the central column of Figure 8. The right column of the same figure displays contour plots of the azimuthal velocity for various values, clearly showing the vortex’s intensification and vertical stretching.

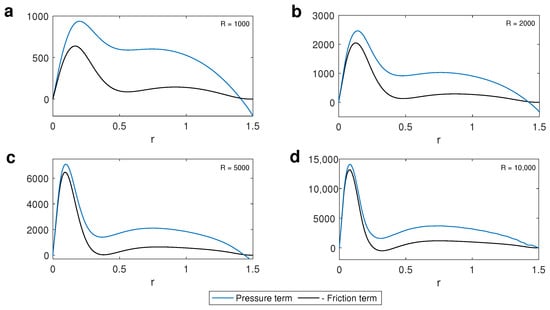

Interestingly, we observe that this contraction eventually halts, even though the azimuthal velocity continues to increase as the vortex intensifies. This phenomenon is depicted in Figure 10, which shows azimuthal velocity profiles for different values. The primary mechanism preventing further contraction of the RMAV is the frictional force, as shown in Figure 11. Once this force balances the inward advection caused by radial inflow—by counteracting the radial pressure gradient—the RMAV stabilizes and maintains a stationary value, despite continued vortex intensification. Although our results correspond to stationary states, they align with the behavior observed in the evolution of hurricanes, particularly the radius of maximum tangential wind (RMW). As reported in Ref. [32], the RMW contracts continuously during the early stages of intensification, slows abruptly midway through the process, and eventually stabilizes, even as rotational flows continue to strengthen.

Figure 10.

Radial profiles of the azimuthal velocity for different values of showing the contraction of the radius of maximum azimuthal for case A for .

Figure 11.

Radial profiles of the pressure force and the frictional force for different values of for case A for .

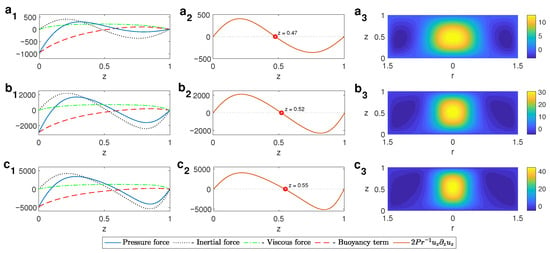

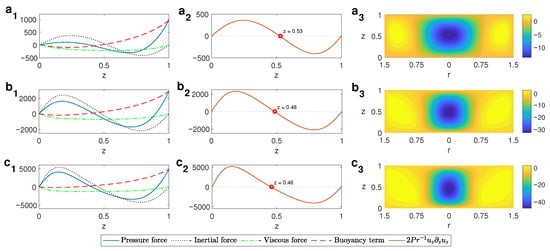

From Figure 7 it is also seen that the vorticity grows vertically when the thermal gradients increase. This growth with height can be explained by looking at the terms of the vertical component of the momentum equation: the pressure force , the inertial force , the viscous force , and the buoyancy force . Inspecting the terms (left column of Figure 12), we observe the balance between them. As increases, the inertial force participating in the balance increases. This inertial force is essentially the term , which is plotted in the central column of Figure 12 for different values of . As the vertical velocity component is positive close to the central part of the cylinder because the fluid goes upwards there, must also be positive (as is positive in the central part of the domain), which means that increases with z in this zone. The height until which remains positive grows with (note the displacement of the point at which to a higher value z), i.e., as the thermal gradients are higher, the velocity continues to grow to a higher height. This can also be observed from the contour profile of the vertical velocity component displayed in the right column of Figure 12. As a consequence, the vortical structure generated develops higher in the vertical direction, i.e., the vortex generated at the lower levels grows further with height (bottom-up vortex). The stretching of the structure can also be observed from the contour profile of the vertical velocity component.

Figure 12.

Left column: profiles in the vertical direction of the pressure gradient, the inertial force, the viscous force, and the buoyancy force for . Central column: profile of term for . Right column: contour plots of the vertical velocity in the r-z plane. From top to bottom: () ; () ; () ; . Case A for .

If the horizontal thermal inhomogeneity is set at the top surface, i.e., a cold pool is present at upper levels (case B), the vortex generates at those levels. The situation of a cold pool aloft is found in the context of tornadogenesis [33] in the cold air funnels, funnel clouds pendant from the base of convective clouds that form in the vicinity of cold pools of air aloft [34]. Figure 13 displays profiles of the vertical component of the vorticity for when is varied. As is observed, the increase in , in this case, means stronger cooling of the central upper part of the domain and implies an increase in the vertical vorticity, i.e., a more intense spin motion in the central region. As for case A, if we have a look at the terms of the radial component of the momentum equation now at a high z level, for instance, (left column in Figure 14), we observe the balance between the radial pressure gradient, the Coriolis force, and the inertial force (essentially, the centrifugal force). When the thermal gradients grow, the pressure gradient increases, and so does the centrifugal force, which implies a growth of the azimuthal velocity, thus leading to an intensification of the vortex. The radius of maximum azimuthal velocity undergoes contraction when grows, as displayed in the central column of Figure 14. This rises to the stretching of the vortical structure formed, as seen in the right column of Figure 14, which displays the contour of the azimuthal velocity component for different values of . As for the case of bottom-up vortices, a later stop of contraction occurs, with the frictional force responsible for preventing the collapse of the RMAV to the center.

Figure 13.

Profiles of the vertical component of the vorticity when is varied for case B at . From top to bottom: (a) , (b) ; (c) .

Figure 14.

Left column: profiles in the radial direction of the pressure gradient, the inertial force, the Coriolis force, and the viscous force for . Central column: radial profile of the centrifugal force for . Right column: contour plots of the azimuthal velocity in the r-z plane. From top to bottom: () ; () ; () ; . Case B for .

From Figure 13 we see how the increase in affects the development of the vortex towards the ground. The stronger the cold pool imposed at the top, the further downward the vortical structure develops. This agrees with observations in atmospheric cold air funnels [33].

This growth of the vortex towards the ground is again explained by observing the terms of the vertical component of the momentum equation in a region close to the axis of the cylinder. To keep the balance between the pressure gradient, inertial force, viscous force, and buoyancy force as grows (left column in Figure 15 for ), the inertial force, which is governed by the positive term , displayed in the central column in Figure 15 grows. As is negative because the fluid moves downwards at the central region, must also be negative, i.e., decreases faster as z grows, which implies more negative values of at lower z. This is also understood by observing the z point at which , which lowers as grows (central column in Figure 15). As the thermal gradients increase and the vortex grows to the ground, it stretches towards the center of the domain.

Figure 15.

Left column: profiles in the vertical direction of the pressure gradient, the inertial force, the viscous force, and the buoyancy force for . Central column: profile of term for . Right column: contour plots of the vertical velocity in the r-z plane. From top to bottom: () ; () ; () ; . Case B for .

4.2. Tilted Vortex

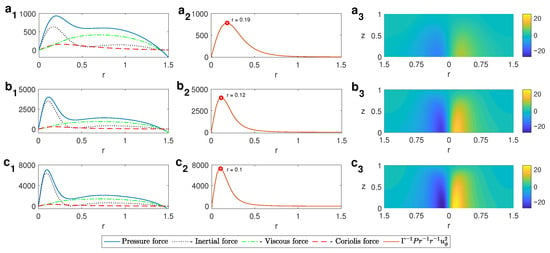

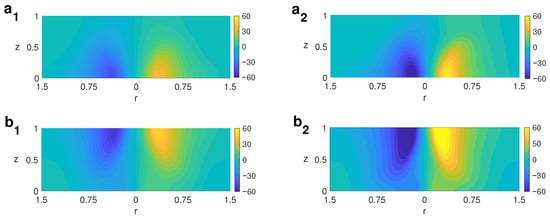

For , the transition from axisymmetric vortex to unsteady flow occurs through a Hopf bifurcation of wavenumber (Figure 4). A periodic structure is found consisting of a tilted vortex (TV) moving periodically around the central axis. Figure 16a shows the profiles of the azimuthal velocity component for two different values of for . The vortical structure is displaced from the center of the cylinder and tilted towards the direction of displacement. As happened with the axisymmetric vortex, if increases, the vortex intensifies, stretches, and grows with height, as shown in Figure 16a. The tilting is reported in observations of some atmospheric vortices [35,36].

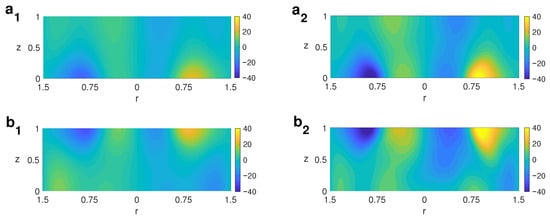

Figure 16.

Contour profile of the azimuthal velocity taken in an angle sectioning the structure, showing the tilted vortex for with two different values of for cases A and B. Left column: ; right column: . (a) Case A; (b) case B.

An analogous situation is found for case B in the regime. A periodic, tilted, displaced vortex, developed now top–bottom, is found. Figure 16b displays the profile of the azimuthal velocity component for two different values of for this case.

4.3. Double Vortex

For larger ambient rotation rates, , the axisymmetric vortex bifurcates through a Hopf bifurcation of wavenumber (Figure 4), and the new periodic structure found consists of a double vortex (DV) spinning around the central axis. The transition occurs this way: the axisymmetric vortex loses its symmetric shape and adopts an elliptic form. The vortex keeps widening as increases, and finally, it splits into two vortices. Figure 17 displays the profile of the azimuthal velocity for two different values of for for both cases A and B, showing the double vortex developing from the bottom up in the case of a heating spike at the bottom (Figure 17a) and from the top down in the case of a cool pool on the top (Figure 17b). It is noted that as increases, the double structure intensifies and grows in the vertical direction. The development of a double vortex is associated with large ambient rotation rates.

Figure 17.

Contour profile of the azimuthal velocity taken in an angle sectioning the structure, showing the double vortex for with two different values of for cases A and B. Left column: ; right column: . (a) Case A; (b) case B.

Observations of atmospheric vortices have reported the development of multiple vortices. In supercell tornadoes, the cases of multiple vortices are related to very intense mesocyclones, that is, a large rate of ambient rotation [37].

5. Discussion and Conclusions

The results presented in this work reveal the importance of horizontal thermal gradients in the development of convective vortices and that the location of this thermal condition determines whether the vortex develops from the bottom up or from the top down. This may be of importance in the context of tornadogenesis and the question of where the vorticity initially appears.

The magnitude of the vertical and horizontal thermal gradients plays a key role in both the intensity of the vortex and its stretching. Larger thermal gradients develop more intense vortices that grow with height from the bottom up in the case of a heating spike at the bottom and from the top down in the case of a cold pool at the top. This growth in the vertical direction is accompanied by a stretching of the structure, a contraction of the radius of the maximum azimuthal velocity, and a subsequent stop in the contraction, even though the vortex keeps intensifying, as our analysis shows. This study is based on a balance force analysis.

Depending on the ambient rotation, the axisymmetric stationary vortex found (AV) can remain axisymmetric when increases (i.e., when the thermal gradients increase), with this happening for smaller rotation rates; it can bifurcates to a tilted vortex (TV) that moves periodically around the cylinder’s axis if the rotation rate is higher; and for largest rotation rates, the axisymmetric vortex splits into a double vortex (DV). This behavior is observed for both top-down and bottom-up structures. The increase in thermal gradients results in intensification, stretching, and growth in the vertical direction, as reported for the axisymmetric vortex.

The results obtained may contribute to the understanding of the genesis, morphology, and intensification processes of developed thermoconductive vortices [32,38,39].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; methodology, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; software, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; validation, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; formal analysis, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; investigation, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; resources, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; data curation, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; writing—review and editing, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; visualization, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; supervision, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; project administration, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H.; funding acquisition, M.C.N., D.C., and H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the research grants PID2023-152004NB-I00, (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and 2022-GRIN-34320 (Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha), which include ERDF funds.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the research grants PID2023-152004NB-I00 (MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and 2022-GRIN-34320 (Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha), which include ERDF funds.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lemon, L.R.; Doswell, C.A., III. Severe thunderstorms evolution and mesocylone structure as related to tornadogenesis. Mon. Weather Rev. 1979, 107, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestein, H.B. Severe Convective Storms and Tornadoes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.A.; Wood, V.T. The tornadic vortex signature: An update. Wea. Forecast. 2012, 27, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, R.J.; Davies-Jones, R. Tornadogenesis with and without a dynamic pipe effect. J. Atmos. Sci. 1997, 54, 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapp, R.J.; Mitchell, E.D.; Tipton, G.A.; Effertz, D.W.; Watson, A.I.; Andra, D.L.; Magsig, M.A. Descending and nondescending tornadic vortex signatures detected by WSR-88Ds. Wea. Forecast. 1999, 14, 625–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.K.; Leslie, L.M. A numerical study of tornadogenesis in a rotating thunderstorm. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 1979, 105, 107–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, L.J.; Wilhelmson, R.B. Simulation and analysis of tornado development and decay within a three-dimensional supercell thunderstorm. J. Atmos. Sci. 1995, 52, 2675–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.M.; Bluestein, H.B.; Popstefanija, I.; Baldi, C.A.; Bluth, R.T. Reexamining the vertical development of tornadic vortex signatures in supercells. Mon. Weather Rev. 2013, 141, 4576–4601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bluestein, H.B. A review of ground-based, mobile, W-band Doppler-radar observations of tornadoes and dust devils. Dyn. Atmos. Oceans 2005, 40, 163–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, M.M.; Bluestein, H.B.; Dowell, D.C.; Wicker, L.J.; Kramar, M.R.; Pazmany, A.L. Mobile, phased-array, Doppler radar observations of tornadoes at X-band. Mon. Weather Rev. 2014, 142, 1010–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houser, J.L.; Bluestein, H.B.; Snyder, J.C. Rapid-scan, polarimetric, doppler radar observations of tornadogenesis and tornado dissipation in a tornadic supercell: The El Reno, Oklahoma storm of 24 May 2011. Mon. Weather Rev. 2015, 143, 2685–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Aurnou, J.M. Tornado-like Vortices in the Quasi-Cyclostrophic Regime of Coriolis-Centrifugal Convection. J. Turbul. 2021, 22, 197–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecke, R.E.; Niemela, J.J. Heat transport in the geostrophic regime of rotating Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 114301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Shishkina, O. Rotating non-Oberbeck-Boussinesq Rayleigh-Bénard convection in water. Phys. Fluids 2014, 26, 055111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecke, R.; Shishkina, O. Turbulent Rotating Rayleigh-Bénard Convection. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2023, 55, 603–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, F.; Mercader, I.; Batiste, O.; Lopez, J. Centrifugal effects in rotating convection: Axisymmetric states and three-dimensional instabilities. J. Fluid Mech. 2007, 580, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Horn, S.; Aurnou, J.M. Regimes of Coriolis-Centrifugal Convection. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2018, 120, 204502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, S.; Aurnou, J.M. Rotating convection with centrifugal buoyancy: Numerical predictions for laboratory experiments. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2019, 4, 073501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wordsworth, R.D.; Read, P.L.; Yamazaki, Y.H. Turbulence, waves, and jets in a differentially heated rotating annulus experiment. Phys. Fluids 2008, 20, 126602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincze, M.; Harlander, U.; von Larcher, T.; Egbers, C. An experimental study of regime transitions in a differentially heated baroclinic annulus with flat and sloping bottom topographies. Nonlinear Process. Geophys. 2014, 21, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.C.; Castaño, D.; Herrero, H. Determining the morphology of tornado-like vortices depending on thermal gradients: A numerical study. Phys. Fluids 2023, 35, 063605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberbeck, A. Über die Wärmeleitung der Flüssigkeiten bei der Berücksichtigung der Strömungen infolge von Temperaturdiffezen. Ann. Phys. Chem. 1879, 7, 271–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boussinesq, A. Theorie Analytique de la Chaleur; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Rotunno, R.; Bryan, G.H.; Nolan, D.; Dahl, N. Axisymmetric tornado simulations at high Reynolds number. J. Atmos. Sci. 2016, 73, 3843–3854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewellen, W. Tornado Vortex Theory; Geophys Monograph Series; AGU: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; Volume 79, pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Castaño, D.; Navarro, M.C.; Herrero, H. Double vortices and single-eyed vortices in a rotating cylinder under thermal gradients. Comput. Math. Appl. 2017, 70, 2238–2257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boronska, K. Three-Dimensional Patterns in Cylindrical Rayleigh-Bénard Convection. Ph.D. Thesis, Paris Sud University, Orsay, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tuckerman, L. Divergence-free velocity fields in nonperiodic geometries. J. Comput. Phys. 1989, 80, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudinger, S.; Knobloch, E. Mode interaction in rotating Rayleigh-Bénard convection. Fluid Dyn. Res. 2003, 33, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, M.C.; Castaño, D.; Herrero, H. Thermoconvective instabilities to explain the main characteristics of a dust devil-like vortex. Physica D 2015, 308, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies-Jones, R.P. Tornado dynamics. In Thunderstorm Morphology and Dynamics, 2nd ed.; Kessler, E., Ed.; University of Oklahoma Press: Norman, OK, USA, 1986; pp. 197–236. [Google Scholar]

- Kieu, C.Q. An investigation into the contraction of the hurricane radius of maximum wind. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2012, 115, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. Tornadoes with cold core 500-mb lows. Weather Forecast. 2006, 21, 1051–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooley, J.R. Cold air funnel clouds. Mon. Weather Rev. 1978, 21, 1368–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, P.C. The lower structure of a dust devil. J. Atmos. Sci. 1973, 30, 1599–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattson, J.O.; Nihlén, T.; Yue, W. Observations of dust devils in a semi-arid district of southern Tunisia. Weather 1993, 48, 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wurman, J. The multiple-vortex structure of a tornado. Weather Forecast. 2002, 17, 473–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, K.A. Thermodynamic control of hurricane intensity. Nature 1999, 401, 61–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotunno, R. The fluid dynamics of tornadoes. Annu. Rev. Fluid. Mech. 2013, 45, 59–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).