Abstract

Graph learning is well suited to modeling relationships among communicating entities in network intrusion detection. However, the resulting models are frequently difficult to interpret, in contrast to many classical approaches that offer more transparent reasoning. This work integrates SHapley Additive exPlanations with temporal, edge-aware GNN based on GraphSAGE architecture to deliver an explainable, inductive intrusion detection model for NetFlow data named TE-G-SAGE. Using the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset, flow data are transformed into temporal communication graphs where flows are directed edges and endpoints are nodes. The model learns relational patterns across two-hop neighborhoods and achieves strong recall under chronological evaluation, outperforming a GCN baseline and recovering more attacks than a tuned XGBoost model. SHAP is adapted to graph inputs through a feature attribution on the two-hop computational subgraph, producing global and local explanations that align with analyst reasoning. The resulting attributions identify key discriminative features while revealing shared indicators that explain cross-class confusion. The research shows that temporal validation, inductive graph modeling, and Shapley-based attribution can be combined into a transparent, reproducible intrusion detection framework suited for operational use.

1. Introduction

Intrusion and anomaly detection remain central to cyber-defense, this has motivated the use of machine learning and deep learning, which can capture subtle deviations but often operate as black boxes, reducing analyst trust. Explainable AI (XAI) is therefore needed to clarify why specific flows are flagged and to support triage and forensics.

Graph neural networks (GNNs) are well suited to network security because traffic is inherently relational: hosts interact through flows that form a graph, and many attacks manifest as multi-hop patterns such as scanning or lateral movement [1]. Spatial GNNs aggregate neighborhood information and outperform classical ML on IoT IDS benchmarks [2], while temporal extensions improve the robustness under dynamic traffic with contrastive learning [3].

Interpretability, however, remains a deployment barrier. Analysts must justify alerts with concrete evidence, such as which host, port, or time attributes contributed. Shapley-value methods provide principled marginal attributions, and SHAP is well established in classical IDS, offering global and local explanations aligned with analyst workflows, with recent graph-specific variants improving fidelity and runtime [4,5].

A second methodological challenge is chronology. Because NetFlow carries timestamps, evaluation must preserve the temporal order to avoid leakage. Random or stratified splits risk training on future traffic and inflating performance. Chronological splits and time-respecting graphs better reflect deployment, especially under a class imbalance where PR-based evaluation is recommended [6]. Common ML practice uses random train/validation/test splits preserving class balance [7], but this rarely respects temporal structure. Models trained on future traffic to explain past behavior risk unrealistic performance. Robust evaluation must preserve chronology end-to-end, including during graph construction.

Finally, GNNs remain difficult to interpret for operational IDS, where explanations must identify which flow features and neighborhood interactions drove a decision. Post hoc GNN explainers do not always provide cooperative semantics, whereas Shapley-value methods quantify each input’s marginal contribution. SHAP is widely used for tabular and tree-based IDS and increasingly adapted to graphs, where recent methods provide node- and edge-level attributions with improved fidelity [4]. Prior IDS work demonstrates that SHAP improves trust and decision-making [5], motivating its extension to graph-based intrusion detection.

Motivated by these gaps, this study introduces a temporally faithful, edge-aware graph-based intrusion detection approach with Shapley-value explanations for NetFlow traffic. The methodology comprises three key steps: constructing time-respecting communication graphs and enforcing strict chronological evaluation to prevent leakage, benchmarking the proposed model against non-graph and spectral GNN baselines under identical temporal splits, and extending a Shapley-based framework to quantify feature-level contributions through both local and global explanations. This design advances the state of the art by jointly addressing temporal validity, graph-structured learning, and explainability in intrusion detection. Furthermore, to facilitate further research, we have made our code publicly available (Supplementary Materials).

The reminder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a background on different GNN architectures and related work in connection with explainability for NIDS. Also, problem statements and paper contribution are outlined. Section 3 follows with Material and Methods detailing the approach to the problem. Section 4 outlines the results, and Section 5 is the conclusion and discussion with potential for future research. Lastly, Appendix A outlines algorithms used.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. GNN Architectures

GNNs for intrusion detection are broadly divided into spectral (e.g., GCN) and spatial (e.g., GraphSAGE, GAT) approaches. Spectral models rely on the graph Laplacian and are largely transductive, restricting generalization to unseen hosts or flows in operational environments [8,9]. Spatial models instead aggregate information locally and support neighbor sampling, enabling scalable mini-batch training on large or streaming NetFlow graphs. GraphSAGE was designed for inductive inference with parameterized aggregators (mean/pool/LSTM) and bounded k-hop neighbor sampling, making it well suited for time-ordered traffic where new entities appear continuously [10,11]. GAT extends spatial aggregation with attention, improving performance under noisy and heterogeneous neighborhoods [12,13], including timeseries applications [14]. Large-graph studies emphasize that sampling is essential for handling skewed degree distributions and memory constraints [15,16]. Traditional GNNs largely ignored edge attributes, motivating edge-aware variants that incorporate flow features directly. Lo et al. [2] aggregate endpoint neighborhoods and concatenate node embeddings to form flow representations, while FN-GNN introduces domain-specific encoders using IP relationships [17]. These approaches show that leveraging edge features yields more expressive intrusion detectors.

Another strategy is to elevate edges to nodes via line-graph transformations, allowing standard GNN layers to perform flow classification. Chang et al. [18] demonstrate this on bipartite traffic graphs, and Duan et al. [19] use dynamic line graphs to capture evolving communication patterns by converting edge classification into node classification on a line graph while substantially increasing the graph size and construction complexity.

Recent temporal GNN-IDS research highlights the need for chronological evaluation, time-respecting graphs, and robustness to drift. Temporal-contrastive GNNs learn history-aware embeddings and reduce false positives under evolving traffic [20]. Enhanced models further strengthen edge representation, such as E-ResGAT, which adds edge-aware attention and residual learning for imbalanced data [18]. Pre-computed embeddings like node2vec offer strong baselines but lack the end-to-end coupling of structure and features [21]. Edge-level intrusion detection naturally aligns with formulations that compose endpoint embeddings into flow representations, and dynamic snapshots allow inductive application across windows. Hybrid approaches combining scattering transforms or node2vec embeddings with GNNs also report competitive results, underscoring the value of topology-aware modeling [22].

2.2. Explainability in Graph Neural Networks

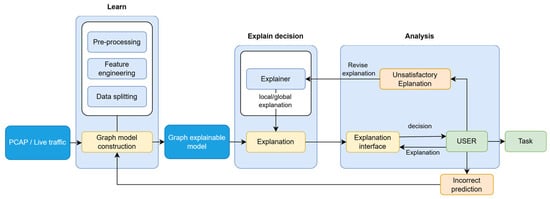

Modern intrusion detection systems increasingly rely on advanced AI models such as deep neural networks and graph neural networks, which achieve strong accuracy but often function as “black boxes”. This opacity limits analyst trust because IDS alerts must be justified before action is taken, and misclassifying a novel attack as benign can have severe consequences. Understanding why a GNN-based IDS fails on unseen attacks is therefore critical for debugging and improving resilience. Existing explanation methods focused on node-similarity objectives extend GNN XAI but do not directly address edge-level intrusion detection [23,24]. Operational IDS require explanations that show which timing, flow, or protocol features made a flow suspicious, enabling analysts to validate alerts and respond effectively. Explainable AI (XAI) (Figure 1) is thus central to operator trust and human–machine collaboration in cybersecurity, especially as IDS models incorporate graph structure and temporal behavior, making traditional rule-based transparency insufficient. There is broad agreement that improving interpretability in IDS remains an important open challenge.

Figure 1.

Architecture for the design of an explainer IDS [23].

GNNs aggregate information over multi-hop neighborhoods, which makes it difficult to identify which nodes, edges, or features drive a specific prediction. Their predictive strength therefore comes with reduced interpretability, and deployment in security operations requires methods that can clarify GNN decision processes. A recent taxonomy distinguishes instance-level and model-level explanation classes, outlining their assumptions and fidelity trade-offs [25]. Instance-level methods generate explanations tailored to a specific input by highlighting the features or structural elements that are most influential to the prediction, while model-level methods capture high-level regularities the GNN has learned. Because our goal is to understand the importance of edge features in NetFlow intrusion detection, instance-level explanations are the most appropriate.

Instance-level methods fall into several categories. Gradient-based approaches estimate importance via the derivatives of the output with respect to input features. Examples include adapted saliency maps and integrated gradients for graphs, which highlight important features or nodes by their gradient magnitudes. Perturbation-based methods mask or modify parts of the graph to measure their effect, as in GNNExplainer [26] that removes less relevant edges and nodes through masking.

Decomposition-based techniques assign contribution scores through relevance propagation or Shapley values. Surrogate-based approaches train an interpretable model that approximates local GNN behavior, such as GraphLIME [27].

In this study, we adopt SHAP as the primary explanation method because intrusion detection requires feature-level attributions that analysts can directly act upon. Shapley-value explanations offer a principled, additive decomposition of each flow classification, enabling the transparent and auditable justification of decisions. This makes SHAP particularly suitable for our edge-focused GNN, where understanding how specific flow attributes influence the model’s output is essential for operational reliability.

2.3. Shapley Value-Based Explanations

Converting complex IDS outputs into evidence usable by analysts requires methods that make model decisions interpretable. SHapley Additive exPlanations offer a model-agnostic way to decompose predictions into fair, additive contributions of input factors [23], supporting both global summaries and local case-level insight. Applying Shapley values to graph-based IDS is challenging because predictions depend on both attributes and connectivity, so practical explainers rely on approximation through sampling or sparsification. These properties make SHAP an appropriate choice for security settings, where understanding why a flow is flagged is nearly as important as detecting it.

Prior GNN explainers highlight complementary strategies. GNNExplainer identifies salient subgraphs and feature masks [26], while PGExplainer learns probabilistic edge-importance masks [28]. GraphLIME provides local surrogates for node-level reasoning [29]. Shapley-based methods extend cooperative game theory to graphs, including GraphSVX, which perturbs the graph structure to estimate contributions [29], and GNNShap, which improves coalition sampling and parallelism for scalability [30]. Other variants such as SubgraphX [31], and EdgeSHAPer [32] target structural importance but incur substantial computational cost.

2.4. Paper Contributions

This paper addresses three research questions:

Q1: How to construct time-respecting communication graphs from timestamped NetFlow while preventing future-data leakage?

Q2: Do inductive, relation-aware GNN outperform strong non-graph and spectral baselines under realistic chronological evaluation?

Q3: Which features and relational contexts drive predictions?

Guided by these research questions, the paper outlines following core contributions:

- a reproducible preprocessing methodology that cleans, normalizes, and constructs temporally consistent train, validation, and test partitions of NetFlow data, ensuring strict chronological integrity which no prior explainer explicitly addresses.

- an edge-aware, inductive intrusion classifier with flow aware feature attribution (TE-G-SAGE), through a post hoc Shapley-based explanation framework for individual flows and which is generalizable to other graph architectures, bridging model-agnostic XAI with graph deep learning.

- state-of-the-art graph learning with explainability scalable to millions of flows, our work contributes to building more transparent and trustworthy intrusion detection systems.

3. Materials and Methods

In this work we focus on instance-level explainability for multiclass, flow-level decisions, using a graph-based model that supports SHAP tied directly to each attack family. The explainer assigns importance scores to edge features, indicating which flow attributes or local connections influenced a given alert. This preserves the locality and provides case-specific evidence. This granularity of explanation is well-suited for network security by pointing to the flow characteristics that triggered the model’s alarm.

Our method serves as a lean inductive baseline for an explainable flow-based intrusion detection graph model with temporal constraints. As shown in Table 1, Lo W et al. in [2] randomized original IP addresses which changed the spatial distribution of the network. Most reviewed works [2,8,17,18] have not considered the temporal characteristics of the flows and unavoidably trained the network on future traffic. Recent works capture the spatial and temporal characteristics of the flows. TCG-IDS [20] used node classification through the temporal contrasting method, and DLGN [19] generated edge embeddings through a line graph by performing mapping of edges to nodes to effectively use graph convolution.

Table 1.

Comparison of models.

As shown in Table 2, we built an explainable flow and time aware graph model for on edge-based GraphSAGE that reflects its suitability for time-ordered NetFlow with the support of inductive generalization to unseen hosts and flows, that prevents look-ahead bias and provides scalable mini-batch training that runs more efficiently on sparser computer resources. Through post hoc Shapley methods, it produces representations enabling feature-level attribution for each detected anomaly.

Table 2.

Comparison of explainable models.

3.1. Methodology

With the aim of designing the method of integration of SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) into GraphSAGE focused on edge features, applicable to NetFlow-based datasets, our methodology consists of following main stages:

- Datasets selection and preprocessing

- Temporal splitting and data transform

- Graph construction

- Edge-aware GraphSAGE model construction and training

- Model evaluation

- Explainability method: SHAP for edge-aware GNN

- Results

This design ensures that the resulting approach is reproducible, comparable across datasets, and generalizable to other GNN variants.

3.2. Data Colection and Preprocessing

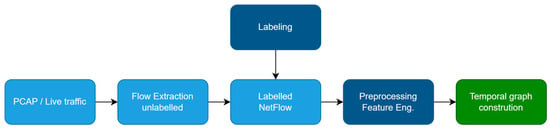

All experiments use NetFlow reformulation of UNSW-NB15 [33], a NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset [34] in which each record is a timestamped flow with L3/L4 endpoints and per-flow statistics (Figure 2). This simulates real network traffic from various sources that are fed to an IDS system using flow records. The raw network packets of the UNSW-NB15 dataset were created by the Cyber Range Lab of UNSW Canberra for generating a hybrid of real modern normal activities and synthetic contemporary attack behaviors. The dataset contains 2,391,775 labeled flow records collected over a two-month period, with 96,553 of these being malicious flows. This dataset has nine types of attacks, namely, Fuzzers, Analysis, Backdoors, DoS, Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance, Shellcode, and Worms. The dataset is provided in a standardized 53-feature NetFlow format (Table 3), which simplifies cross-dataset experimentation and preserves key traffic features such as packet counts, byte rates, and protocol flags.

Figure 2.

Process of preparing data from raw PCAP files or dataset for graph construction.

Table 3.

Dataset features.

After initial analysis, datasets show heavy imbalance characteristics, where benign traffic is dominant with 96.02% of all records. During processing, numeric dtypes were enforced for quantitative fields (e.g., bytes, packets, duration, etc.) and categorical dtypes for protocol and flags. Exact duplicates or rows that are missing the IP address or ports are dropped, as it would interfere with construction of the graph. Missing values are imputed with medians for quantitative features and NA for inf values. Throughput columns with NA values are filled with 0 as it corresponds with very low data throughput, due to 120 s limit on flow duration.

3.3. Temporal Splitting and Data Transform

We adopt a strictly time-respecting data partitioning and batching scheme to avoid temporal leakage.

First, we construct non-overlapping chronological splits (Table 4) at the edge (flow) level. Let each flow be associated with a start time and end time . We determine temporal cut points and such that the training, validation, and test sets form disjoint subsets:

Table 4.

Chronological split, normalized based on start of first flow t0 = 1,421,927,376,907 ms.

These index sets are computed once and persisted. All subsequent stages (feature transformation, graph construction, model training) use the same indices. This guarantees that no edge appearing in validation or test time intervals is ever included in the training set, thereby eliminating direct timestamp leakage.

We use a two-stage feature engineering process that controls correlation based pruning and categorical cardinality.

All transformations fit exclusively on the training split and are then saved for the validation and test. Numeric attributes are transformed by a monotone mapping for predominantly non-negative features and standardization using a StandardScaler fitted on training data. The same parameters are reused on later splits.

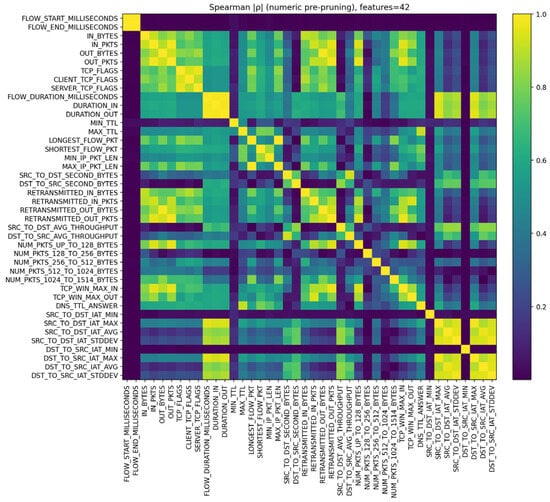

Because NetFlow flow features are highly skewed and heavy-tailed, their relationships tend to be monotonic rather than strictly linear. Spearman’s rank correlation is robust to such non-normal distributions and outliers, capturing flow metric dependencies (e.g., larger flows with more packets). Recent NIDS feature-selection studies [35] on flow-based datasets likewise favor rank correlation or mutual information, noting that pruning redundantly correlated features preserves non-linear predictive signals. Removing these collinear features also improves model training stability by avoiding gradient issues caused by duplicate inputs. Conservative correlation-based pruning is applied to numeric features, and on the training window we compute the absolute Spearman’s rank correlation matrix , that is robust to monotone transformations and heavy-tailed NetFlow marginals (Figure 3). For feature pairs with , we treat them as redundant and retain a single representative per correlated group, after zero-variance removal. A total of 4 features, that are highly correlated pairs, are removed during pruning. The resulting feature set of 38 is stored and the same selection mask is applied to the validation and test.

Figure 3.

Spearman’s rank–correlation pruning.

Categorical attributes (protocol and application-layer identifiers) are encoded via one-hot vectors, with per-column cardinality capped using minimum frequency to prevent dimensionality blow-up. To address the potential loss of discriminative information, we report the numbers of numeric attributes before and after the pruning step. Together with the suitability of Spearman’s for non-Gaussian, monotone NetFlow attributes, this supports our claim that pruning reduces dimensionality and multicollinearity without discarding uniquely informative features. After transformation, our dataset has a numerical dimension of 38 and categorical dimension of 563.

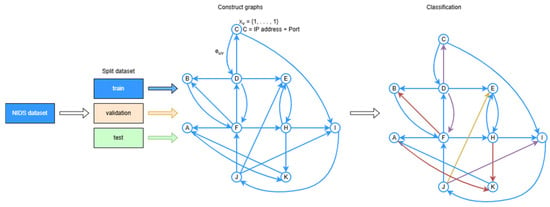

3.4. Graph Model Construction

To leverage graph neural networks, we represent the network traffic data as a graph of hosts and flows (Figure 4). The combination of IP address and port uniquely identifies the specific service on a device. Thus, we represent each unique IP address and port in the dataset as a node in the graph, and each network flow becomes an edge connecting the source and destination IP nodes. Communication graphs are built per temporal window (or on-the-fly via sampling). Edges correspond to directed flows src → dst, each carrying the edge features derived from the underlying NetFlow. To avoid injecting unstable node metadata, node features are set to a constant vector and topology, and edge attributes drive learning.

Figure 4.

Graph construction on temporal dataset splits illustrating the directed communication graph used for flow classification. Nodes (A, B, …) represent hosts and directed edges represent network flows with associated attributes. Multi-hop connectivity (2-hop and beyond) captures relational context used by the GNN to classify (color) each flow based on both its own features and the surrounding structural patterns.

We construct separate graphs , , from , , . Neighbor sampling for mini-batch training is performed on . Every sampled (k)-hop neighborhood for a training batch can only traverse edges in . Edges from future time intervals (validation or test) are structurally absent and therefore cannot be reached during sampling.

Edge features and labels are retrieved by the global edge identifiers associated with the corresponding split. During training, the dataloader queries only train data using edge IDs contained in . This design prevents the model from accessing feature representations of edges in or at any point in the training procedure.

Finally, node-level leakage is mitigated by two properties: (i) the graphs do not store node features that aggregate information across time, and (ii) even if the same IP + port endpoint appears in multiple temporal splits, its incident edges in are restricted to . Thus, any node that also participates in future flows is observed during training only through the edges whose timestamps lie within the training interval. As a result, both the construction of chronological splits and the neighbor-sampling based batching process are strictly confined to the appropriate temporal window, ensuring that the model does not exploit information from future events.

We implement the model using Deep Graph Library (DGL). DGL was selected for its strong performance on large, sparse graphs and its mature integration with multiple deep-learning back ends. This choice ensures that the system can sustain the scale of our NetFlow graphs and the repeated construction of neighborhood subgraphs during training and inference.

Chronological split indices (train/val/test) are computed using FLOW_START_MILLISECONDS (and FLOW_END_MILLISECONDS) so each split contains only edges whose start times fall within its temporal interval. , , etc. This enforces disjoint temporal edge sets. To ensure no temporal leakage occurs, edge feature are fetched by edge ID-s (Table 5). Nodes have no temporal aggregate stored, thus nodes appearing later in time do not inject the future summary.

Table 5.

Total number of nodes and edges in train/val/test.

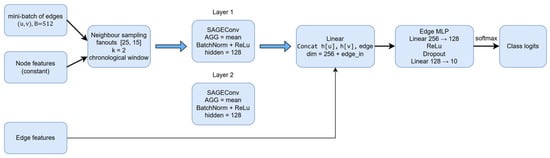

We use a 2-layer GraphSAGE with 2-hop neighborhoods to match the structure of NetFlow traffic, as seen in Figure 5. One hop captures direct communication partners, while two hops are sufficient to see many-to-one and one-to-many patterns typical of DDoS and scanning (e.g., attacker → victim, victim → other services). Deeper neighborhoods would substantially increase the number of sampled nodes and edges per mini-batch, as shown in [2], and increase the risk of oversmoothing in heterophilic or mixed-label traffic graphs [36]. In preliminary tuning, we therefore fixed the depth to 2 and varied the width of the neighborhood via fan-out. In NetFlow, static host features have high-cardinality (IP addresses, ports). Using constant node embeddings enables the model to treat nodes as anonymous routers of flow context and avoids leaking host labels into the encoder. This is consistent with other flow-centric GNN IDS methods that emphasize edge features and relational structure rather than rich node attributes.

Figure 5.

Temporal edge-aware model for flow classification. A 2-hop neighbor sampler feeds two GraphSAGE layers. Endpoint embeddings h[u], h[v] are concatenated with edge features and passed to an edge-level MLP to produce multiclass logits. A learned constant node embedding is fed to the model, preserving inductive operation across unseen nodes.

Fan-out parameters control how much context the two hops see. We ran a small grid search over fan-outs }, hidden sizes , dropout , and batch sizes , training with cross-entropy and Adam optimizer. Early stopping is applied using loss function. The best validation accuracy was obtained with hidden size 128, fan-out , dropout 0.4, and batch size 512. Larger fan-outs did not improve and sometimes degraded validation accuracy, consistent with oversmoothing: for NetFlow graphs, very broad neighborhoods mix many unrelated flows and dilute the anomaly signal.

Each layer performs neighborhood aggregation on a mini-batch subgraph sampled by k-hop neighbor sampling (k = 2). For each flow edge u→v we draw a fixed fan-out of 25 for one-hop neighbors, then 15 at two-hop neighbors, restricted to the current time window to preserve chronology. The union of sampled nodes and edges forms a computation graph on which the model executes two message-passing steps, as shown in Figure 5. Endpoint node embeddings are concatenated with the engineered edge features to form an edge representation, which is fed to a small fully connected classifier (Algorithm A1).

3.5. Explainability Method: SHAP for Edge-Aware GNN

To make the GNN’s predictions interpretable, we adapt SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to our model.

Exact Shapley values require evaluating all coalitions and are intractable for realistic inputs. The Kernel SHAP [37] framework by Lundberg and Lee addresses this by fitting a weighted linear surrogate to masked perturbations of the instance, where the Shapley kernel emphasizes small and large coalitions and ensures the surrogate’s coefficients approximate the true values. Instead of exhaustively checking all feature combinations, it then solves a linear regression to infer the contribution of each feature.

The idea is to define binary coalition mask indicating the presence of a feature in perturbed input. Then, we treat model f(x) as if it were an unknown linear function of the mask:

We implement our GNN explainability using Kernel SHAP approximation, which allows us to treat our model as a black box and still obtain reliable importance scores for each input component. Edge-level predictions for a target class c are explained by holding the pair embedding fixed and varying only the edge feature vector , numeric and one-hot encoded categorical features. For a single edge, SHAP returns a signed vector such that

where f is the score class c at the fixed embedding and x0 is background expectation. In this form, the sign encodes direction:

- : a feature j pushes score toward class c for this edge.

- : a feature j pushes score away from class c for this edge.

Signed mean SHAP (per class) is the average of those signed vectors over many edges from that class:

If we obtain a large positive signed mean SHAP , for feature j in class c (e.g., DoS) means that on average across DoS flows, increasing feature j raises the DoS score at fixed context. A negative value means feature j suppresses the class c score for that class’s flows. Magnitude (mean |SHAP|) identify most influential features.

Our approach applies this concept to intrusion detection temporal graph-structured netflow data. For each attack family we compute mean |SHAP| and signed mean SHAP by averaging the per-feature SHAP values across a random stratified sample of flows from that class (Algorithm A2). We report both mean absolute SHAP for feature ranking and signed mean SHAP to clarify directionality.

4. Results

4.1. Model Evaluation

All experiments were run in a virtualized shared environment on AMD Epyc 7713 2.0 GHz and 24 GiB system RAM server with nVidia A100 GPU 40 GB VRAM. We relied on DGL’s mini-batch pipeline to avoid loading the full graph into the device memory to avoid out-of-memory errors. Uniform neighbor sampling without replacement was used to limit the influence of high-degree nodes and stabilizes gradients. Random seeds were fixed for reproducibility. This configuration yielded a temporal edge classifier that processes traffic flows, learns spatial and temporal dependencies, and remains usable at production scale.

Model evaluation was performed on the temporal test split with the best hyperparameters fixed from training. Due to the highly imbalanced dataset, we reported per-class precision, recall, and F1-score, and aggregated them as macro averages to give equal weight to rare attack classes. We also quantified the false alarm rate (FAR) both globally and per class, since false positives directly affect analyst workload and operational trust.

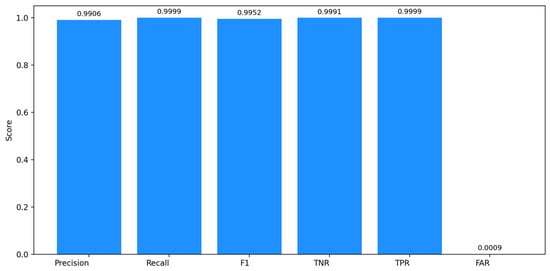

4.2. Binary Evaluation Metrics

The NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset was used to assess the binary detection capability of the proposed model. As shown in Figure 6, the model achieved excellent binary classification performance, with a precision of 99.06%, recall of 99.99%, F1-score of 99.52%, TNR of 99.91%, TPR of 99.99%, and 0.09% FAR. These results demonstrate that the model can reliably distinguish malicious from benign traffic, with state-of-the-art sensitivity and specificity. The extremely low FAR indicates that benign flows have low misclassification, which is critical for operational IDS deployments. Overall, the binary evaluation confirms that the temporal, edge-aware GNN design maintains strong discriminative power while preserving operational reliability.

Figure 6.

Overall performance under NF-UNSW-NB15-v3.

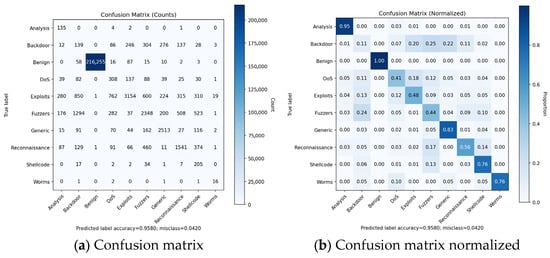

4.3. Multiclass Metrics

On the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 the confusion matrix and derived metrics show a clear split between classes that the model learns reliably and those for which performance is substantially weaker (Figure 7). Benign traffic dominates the dataset, and the model achieves excellent detection for this class (Precision = 1.00, Recall = 0.999, FAR = 0.0), which is expected due to heavy class imbalance and highly separable feature profile.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrix for attack categories.

For the attack classes Backdoor, Shellcode, Analysis, and Worms model, precision is low (0.052–0.372), as seen in Table 6, indicating a high rate of false positives. This is consistent with their extremely small sample counts in the dataset, which limits the model’s ability to learn class-specific patterns from similar attack categories, such as Backdoor being misclassified as Fuzzers or Exploits. These classes also exhibit the highest FPR (Backdoor FAR = 0.011, Fuzzers FAR = 0.007, and Shellcode FAR = 0.006), and the model incorrectly assigns Benign or other attack flows to these categories. Classes with moderate frequency and structured behavioral signatures Generic, Reconnaissance, and Exploits show a more balanced performance. For example, Generic achieves the highest F1 of 0.796 among attack classes and a low FAR of 0.003, with Reconnaissance and Exploits indicating partial but not complete separation from neighboring classes. Their corresponding FPR values 0.004 and 0.003 suggest that FP is kept constrained.

Table 6.

Per-class results table.

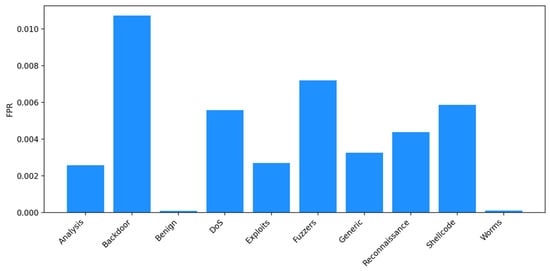

For DoS and Fuzzers, Recall remains limited (0.411 and 0.437) and their FAR is higher (0.006 and 0.007) than in other classes. This follows from both their internal heterogeneity and high overlap in byte/packet-rate statistics with Exploits and Generic classes. The model consistently confuses high-volume bursts across these classes. Across all attack types, the macro-F1 of 0.484 highlights the gap between overall Accuracy (dominated by Benign) and the model’s ability to accurately classify minority attack categories. The macro-FPR of 0.004 demonstrates that even though global FP are low, mentioned attack classes exhibit misclassification into other attack types, driven by dataset imbalance and overlapping feature distributions. Figure 8 shows FPR for all classes.

Figure 8.

Multiclass FPR for NF-UNSW-NB15-v3.

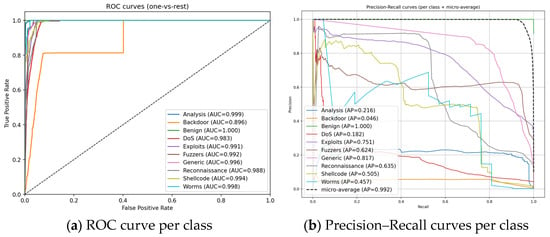

The normalized confusion matrix translates those figures into Recall, while the model ranks nearly all classes well (as seen on ROC curve on Figure 9a). Exploits and DoS have the lowest Recall, with errors primarily in Backdoor, Fuzzers, and Shellcode. Despite that, the ROC curves are uniformly high, with micro-average AUC = 0.999. The conclusion is that even difficult classes can be separated with very low FP rates. This indicates residual errors in the confusion matrix come from the temporal validation rather than a lack of discriminative signal.

Figure 9.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) and Precision–Recall (PR) curves for all attack classes in the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset. Panel (a) shows one-vs-rest ROC curves, highlighting high AUC values across most classes despite class imbalance. Panel (b) presents class-wise PR curves and micro-averaged performance, revealing stronger separation for frequent classes and reduced average precision for rare or heterogeneous attack families. Together, these curves illustrate the model’s ranking ability and the precision–recall trade-offs across different attack types.

The Precision–Recall plot (Figure 9b) demonstrates class imbalance. The micro-average AP is 0.991 reflects the dominance of Benign and excellent precision. While Exploits, Generic, Reconnaissance achieve a high average precision that is consistent with their strong AUCs. Backdoor and DoS with low precision demonstrate their observed confusions into neighboring traffic types. The very low AP for Backdoor indicates high false positives, particularly from Fuzzers. DoS exhibits a similar pattern with confusion to Fuzzers and Shellcode.

While confusion matrices and ROC curves show that the model separates most attack classes effectively, the macro-F1 and per-class PR metrics highlight weaknesses for Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers. These classes are rare in NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 and display substantial intra-class variability, producing overlapping flow signatures with higher-frequency attacks and that limit their discriminability and class separation. To better understand this, we examined class-wise PR curves and observed that these classes require substantially different operating thresholds to balance precision and recall. While full threshold calibration lies outside the scope of this study, the curves indicate that per-class thresholding could meaningfully improve recall for rare attacks without inflating false positives across the remaining classes. This context clarifies that the observed performance gaps reflect dataset-driven constraints rather than a specific deficiency of the temporal GNN formulation.

Our model separates classes in the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 dataset extremely well in a ranking sense, but the performance suffers under the heavy imbalance. The confusion matrix shows where mistakes prevail, while the PR curves quantify the precision cost of pursuing a higher recall on these rare classes. These views together justify the use of class-aware threshold calibration if recall on Exploits and DoS must be raised, and they also motivate targeted future and graph refinements for Backdoor to reduce its false positives without eroding precision in neighboring classes.

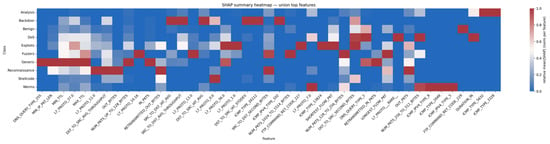

4.4. SHAP Feature Importance

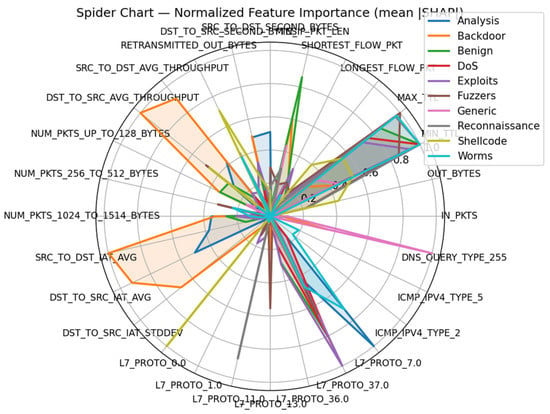

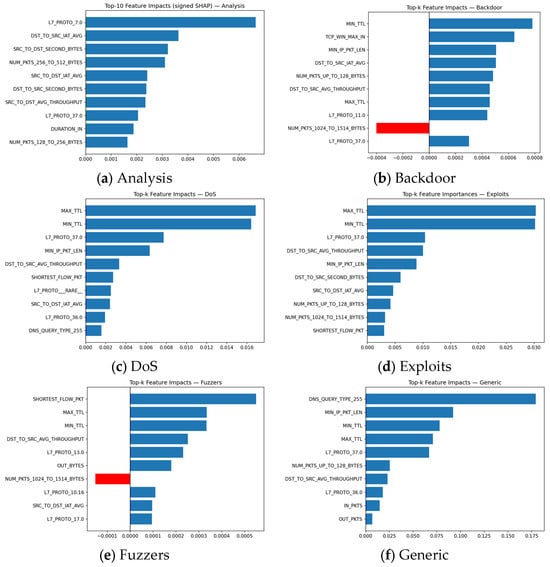

The errors across classes observed in the confusion matrix align closely with the SHAP feature importance patterns, shown in Figure 10. For the classes with the weakest performance such as Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers, SHAP reveals that their feature signatures are not strongly differentiated from other high-volume or burst-pattern attack classes. These classes exhibit broad distributions across byte-based and packet-based metrics (e.g., OUT_BYTES, IN_PKTS, SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES), indicating that the GNN does not identify a dominant, class-specific marker. This lack of distinctive flow-level patterns corresponds directly to their high FPRs (Backdoor FAR = 0.011, DoS FAR = 0.006, Fuzzers FAR = 0.007), where flows from these minority classes are frequently absorbed into more volumetric classes such as Exploits or Generic. Attack types with clear SHAP peaks on protocol features, Reconnaissance (DNS query types), Shellcode (ICMP codes), and Generic (with consistent TTL ranges), achieve significantly better F1 and lower FAR. Spider chart shows sharp spikes for these classes in features like DNS_QUERY_TYPE_255, ICMP_IPV4_TYPE_2, and TTL metrics, reflecting stable behavioral signatures that the GNN reliably captures. This explains their comparatively higher discriminability despite the dataset imbalance.

Figure 10.

Normalized feature importance for mean SHAP for all attack classes.

Backdoor and Analysis with their slightly higher FPR (FAR of 0.052 and 0.181) show no unique SHAP-dominant features. Their signatures largely overlap with multiple attack classes, especially those shaped by high-volume or mixed-protocol patterns. The SHAP plot reveals that these classes lack distinctive markers on both protocol categories and packet-size distributions, resulting in misclassification.

Finally, classes with moderate recall but moderate precision (such as Worms) show SHAP signatures are dominated by a small subset of features (specific ICMP types), suggesting that the GNN identifies their behavior only when these rare indicators are present. This explains high recall (0.762 for Worms) paired with the moderate precision of 0.372 where the model recognizes distinctive spikes but struggles when flows deviate from these forms.

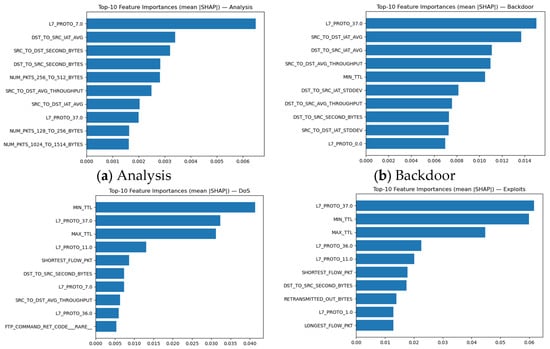

In contrast, attack classes with clear SHAP peaks on protocol specific features, such as Reconnaissance, Shellcode (L7_PROTO types), and Generic (DNS type), achieve significantly better F1 and lower FAR. The spider chart shows sharp spikes for these classes in fields like DNS_QUERY_TYPE_255 and L7_PROTO, reflecting stable behavioral signatures that the GNN captures. This explains their comparatively higher discriminability despite the dataset imbalance. This is further seen per each class in Figure 11a–j.

Figure 11.

Global mean SHAP importance of top 10 features per each class.

Although it is informative of what features are important for predictions for the specific class, Figure provide insight on potential problems in the detection of classes that are overlapping in specific features. To understand the reason behind such behavior, separate analysis is needed to understand what drives its predictions.

Results on Figure 11a–j provide additional information on what shared predictors drive model confusion. The Backdoor SHAP plot shows that the top features L7_PROTO_37.0, SRC_TO_DST_IAT_AVG, DST_TO_SRC_IAT_AVG (inter-arrival time averages), SRC_TO_DST_AVG_THROUGHPUT, and MIN_TTL are not Backdoor specific within NF-UNSW-NB15-v3. Inter-arrival based metrics and throughput summaries appear across many attack classes (e.g., Exploits and Fuzzers), giving Backdoor a feature signature with no dominant discriminator. As a result, the GNN often assigns flows with protocol 37 to Backdoor, leading to systemic false positives. This matches the confusion matrix, where Backdoor predictions spread over many unrelated classes. For DoS, SHAP identifies MIN_TTL, MAX_TTL, L7_PROTO_37.0, and SHORTEST_FLOW_PKT as the strongest contributors. These TTL-based features are common across multiple high-volume classes, including Generic and Exploits, and do not indicate DoS uniquely. The model therefore misses many normal or Exploits-like flows with odd TTL ranges to DoS, explaining the elevated FP rate. The lack of DoS-specific indicators (sustained packet flooding patterns, consistent throughput spikes) in the dataset further weakens this class’s separability.

Fuzzers shows SHAP peaks at MAX_TTL, MIN_TTL, L7_PROTO_37.0, L7_PROTO_13.0, DST_TO_SRC_AVG_THROUGHPUT, and SRC_TO_DST_SECOND_BYTES. This signature overlaps with Exploits, Generic, and DoS flows. TTL instability and protocol-categories dominate the attribution, making the model sensitive to benign protocol variations and causing normal traffic with uncommon TTL and protocol combinations to be mislabeled as Fuzzers. In all three high-FPR classes, SHAP reveals broad, non-distinctive feature profiles, dominated by generic TTL irregularities, protocol-category (L7_PROTO_*), and basic throughput or inter-arrival statistics.

Because these signals are shared across multiple attack classes and even some benign traffic, the GNN lacks precise decision boundaries, leading to systematic false positives. The model correctly amplifies discriminative features when they exist (e.g., DNS types for Reconnaissance, ICMP types for Shellcode), but for Backdoor, DoS, and Fuzzers the dataset does not provide sufficiently unique patterns, which is directly reflected in the SHAP distributions.

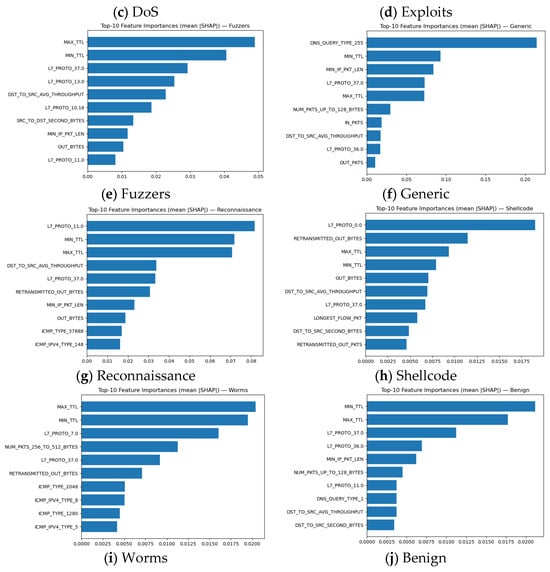

The global signed SHAP, seen in Figure 12a–j, show how contribution characteristics influence predictions. Fuzzers and Backdoors exhibit a negative contribution in NUM_PKTS_1024_TO_1514_BYTES feature whose contribution decreases the class score, while other classes provide insight consistent with mean SHAP.

Figure 12.

Global signed SHAP importance for top 10 features per each class, capturing directionality, revealing which flow attributes promote or suppress classification into this attack category.

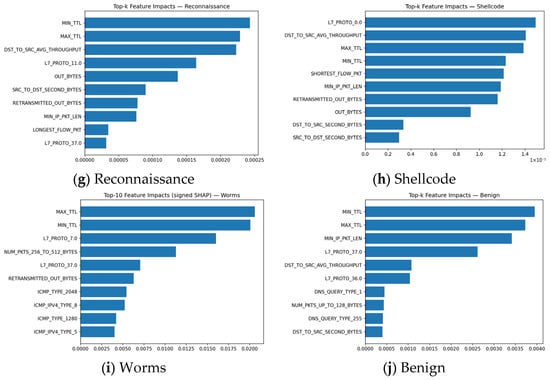

In the SHAP summary heatmap, shown in Figure 13, columns are normalized per feature, so each column aggregates the relative evidence that a single feature provides across classes. Red cells mark the class for which that feature contributes the most to our TE-G-SAGE model decision, while blue indicates a minimal contribution. The cell values represent the mean absolute SHAP magnitude (|SHAP|), capturing the strength of a feature’s influence but not its direction (i.e., whether it pushes probability toward or away from a class). Interpreted this way, columns with a single intense red band reveal better class separation, whereas columns with several warm rows indicate shared cues across classes, which is a likely source of confusion at any fixed operating threshold and a plausible explanation for the cross-class errors observed in the confusion matrix.

Figure 13.

SHAP summary heatmap of top features for local explanations.

4.5. Comparison with Other Models

On the NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 temporal test window, XGBoost attains the highest accuracy and F1, driven by the best precision among the three models, whereas our TE-G-SAGE achieves the highest recall (Table 7). GCN underperforms on all class-aware metrics. Given the strong class imbalance and the dominance of Benign flows, the small spread in accuracy across models is expected. The more discriminative signals are the class-aware metrics (precision, recall, F1). The pattern indicates a classic precision–recall trade-off: TE-G-SAGE recovers more true attacks (highest recall) at the expense of more false alarms (lower precision), while XGBoost is more conservative (higher precision) but misses more attacks (lower recall). GCN is the worst performing, with both low precision and low recall, yielding the lowest F1. All models achieve excellent results. XGBoost is strongest on average AUC, while our TE-G-SAGE remains competitive on Fuzzers, Shellcode, Worms, and DoS (e.g., Worms 0.998, Shellcode 0.992 and DoS 0.979), but shows the widest gap on Backdoor with 0.929. Taken with the earlier findings, TE-G-SAGE has slightly lower AUCs on the hardest classes but still demonstrates a strong ranking, consistent with its recall advantage under chronological evaluation.

Table 7.

Comparative macro average metrics table first stage.

The edge-aware TE-G-SAGE aggregates relational context with two-hop neighborhoods and detects attack patterns that manifest across connections, e.g., distributed scans, DoS fan-outs, or multi-stage exploits, raising the probability of hitting true positives in rare classes. This relational sensitivity explains the higher recall. At the same time, several attack classes share the same high-leverage features (TTL, L7 protocols), as seen in the SHAP heatmaps. Our model message passing can amplify these signals, increasing cross-class confusion (e.g., between Exploits, Fuzzers, Backdoor, and DoS) and thereby lowering precision and F1. TE-G-SAGE trades more detections for more false alarms that is often desirable in analyst-in-the-loop settings where missed attacks are costlier than triaging extra alerts.

The GCN baseline is less aligned with our inductive, temporal setting and, in this configuration, makes weaker use of edge features than TE-G-SAGE. Its stronger tendency toward oversmoothing and the mismatch with the temporal split (new nodes/edges at test time) reduce both precision and recall, which translates to the lowest F1 despite competitive accuracy on benign-heavy data.

The confusion matrices and PR curves explain where the losses accumulate. Classes whose top-ranked features are shared remain entangled at the operating point, yielding lower precision for TE-G-SAGE. Classes with unique features (Generic through DNS type 255, Worms through ICMP codes, Shellcode through retransmissions) are separated more cleanly in both models. The high one-versus-rest ROC AUCs observed earlier imply that thresholding, not lack of separability, is the main driver of the precision and recall differences.

Our baseline choices XGBoost and GCN were selected to isolate the contribution of modeling NetFlow as a temporal, edge-aware graph. XGBoost represents a competitive non-graph learner that fully exploits engineered flow features, whereas GCN provides a graph baseline without edge attributes, illustrating the effect of incorporating flow-level information. More advanced GNN-IDS architectures would shift the focus away from our core objective: establishing a transparent, temporally faithful, inductive model with Shapley-value explanations. We therefore highlight advanced architectures such as TCG-IDS, E-ResGAT, and DLGNN as promising avenues for future work rather than direct baselines. Overall, the analysis emphasizes that minority-class limitations arise primarily from dataset characteristics and that temporal, edge-aware GNNs paired with SHAP offer a practical and interpretable foundation for flow-based intrusion detection.

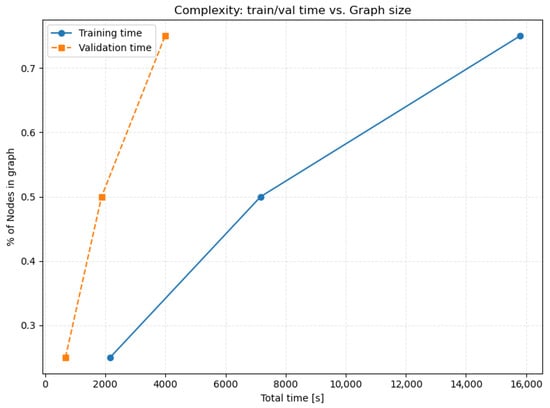

4.6. Time Complexity

Time complexity per epoch and mini-batch edge classification with our model is dominated by neighbor aggregation and number of edges being sampled for each node (Table 8). For a batch of B seed edges, neighbor sampling builds a K-hop subgraph with Nk nodes at layer k dependent to a batch B and product of fan-outs F. The edge classifier operates only on the B seed edges which costs per batch. Reading edge features adds an I/O cost , which is linear in batch size for fixed K, fan-outs Fk, and hidden size h. Overall time complexity per epoch is shown in Table 9.

Table 8.

Comparative training time metrics.

Table 9.

Time complexity of TE-G-SAGE with SHAP.

Memory usage is , proportional to the size of the sampled subgraph rather than to the full graph, which is the main benefit of mini-batch TE-G-SAGE compared to full-batch message passing.

Training and validation time scale predictably with graph size (Figure 14), reflecting the cost of neighborhood sampling and message passing in our two-hop model. As the number of nodes increases from roughly 25% to 75% of the full NetFlow graph, total training time grows almost linearly, consistent with the expected dependence of mini-batch where fan-outs dominate per-batch cost. Validation exhibits a steeper slope because it processes each batch without gradient optimization and uses full-window inference. This empirical trend confirms that the model maintains scalable behavior under increasing temporal windows, indicating that neighborhood sampling successfully bounds computational cost even in large NetFlow graphs.

Figure 14.

Complexity of the stage one model train and validation time vs. graph size.

5. Discussion

Our findings indicate that several attack classes suffer from overlapping NetFlow signatures, leading to reduced precision despite uniformly high ROC areas. This suggests that relying on a single global decision threshold is suboptimal. Future work should therefore examine per-class calibration guided by validation precision–recall curves to identify thresholds that maximize F1 or align with application-specific detection costs. Additionally, the SHAP analyses revealed substantial dependence on shared protocol and TTL features, highlighting the need for stronger representation learning. Promising directions include edge gating or attention mechanisms to suppress weak or noisy connections, as well as temporal contrastive pretraining to produce embeddings that remain stable under traffic drift. These enhancements may improve class separation and robustness in realistic, evolving network environments. As shown in [38], sparsification guided by Shapley values from this research can be used to prune uninformative edges at inference to accelerate deployment while preserving accuracy, but future study will show how it behaves under temporal dataset constraints. Recent studies report consistency challenges in GNN explanations, which motivates diagnosing stability in security settings [39]. A promising direction is self-learning on streaming traffic with weak supervision, continuous learning with drift detection. Built-in temporal explainers based on the graph information bottleneck could reduce reliance on post hoc explanations such as shown in [40]. Dual-modality IDS that combine heterogeneous GNNs with LLMs are emerging as well, combining relational reasoning with textual threat intel [41].

High-degree nodes are common in NetFlow graphs, often corresponding to gateways, DNS resolvers, or load balancers that connect to large portions of the network. Such nodes may disproportionately influence neighborhood aggregation in spatial GNNs, potentially amplifying noise or diluting attack-specific flow patterns. Although a full sensitivity study lies beyond the current scope, we acknowledge this as an important factor for evaluating robustness. Future work will incorporate degree-stratified analyses and controlled neighbor-masking to quantify how TE-G-SAGE behaves across varying degree distributions. This will clarify whether additional mechanisms such as degree-aware sampling or attention normalization are beneficial in highly skewed topologies.

Even though homophily is not the chosen design signal in our model, we can discuss its significance. Because all nodes use constant features and malicious flows typically connect dissimilar hosts, node-level homophily is expected to be low in our setting as intrusion graphs often violate the homophily assumption, with malicious nodes predominantly linking to benign ones, which can cause traditional GNNs to oversmooth and lose anomaly signal during aggregation as shown in [42]. Our edge-centric design relies on edge features and edge-label homophily with the tendency of connected flows sharing the same label. Future work will direct computing dynamic edge-label homophily and relating these scores to temporal variations in GNN performance in evolving graphs to investigate dynamic node classification in edge-focused rather than node approach for NetFlow intrusion detection [36].

6. Conclusions

This work demonstrates that constructing time-respecting communication graphs, applying inductive, relation-aware GNNs, and using Shapley-based flow-level explanations jointly advance the state of the art in NetFlow intrusion detection. The strict chronological design enabled leakage-free evaluation, aligning with emerging best practices for temporal GNN-IDS. TE-G-SAGE showed that multi-hop, edge-aware modeling improves recall under evolving traffic, and clarified how inductive graph learning alters error profiles relative to non-graph and spectral baselines. The SHAP framework produced actionable feature and structure-level attributions, revealing class-specific predictors and shared flow characteristics that govern precision–recall trade-offs. Taken together, the results show that coupling temporal evaluation with an inductive edge-aware GNN and domain-tailored explainability yields a transparent and operationally meaningful IDS, strengthening both interpretability and analytical trustworthiness in modern security environments.

Supplementary Materials

Complete code to replicate results of this paper is published on github at https://github.com/Ricco555/E-GraphSAGE-XAI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.L., D.P. and M.V.; methodology, R.L.; software, R.L.; validation, R.L.; formal analysis, R.L.; investigation, R.L.; resources, R.L. and D.P.; data curation, R.L.; writing—original draft preparation, R.L. and D.P.; writing—review and editing, R.L., D.P. and M.V.; visualization, R.L.; supervision, D.P. and M.V.; project administration, D.P.; funding acquisition, M.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

This research was performed on NetFlow dataset NF-UNSW-NB15-v3 available at the https://staff.itee.uq.edu.au/marius/NIDS_datasets/ (accessed on 29 March 2025) and authors contribution acknowledged through citation of their work.

Acknowledgments

This research was performed using the Advanced Computing service provided by University of Zagreb University Computing Centre—SRCE; This research has been supported by the European Regional Development Fund under grant agreement PK.1.1.10.0007 (DATACROSS).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| DGL | Deep Graph Library |

| DLGNN | Dynamic Line GNN |

| FAR | False alarm rate |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| GNN | Graph neural network |

| IDS | Intrusion detection system |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| NIDS | Network Intrusion Detection System |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1 TE-G-SAGE Mini-Batch Training with 2-Hop Neighbor Sampling |

| 1: , epochs E |

| 2: |

| 3: , Adam optimizer |

| 4: For epoch = 1 … T: |

| 5: Shuffle edges |

| 6: : |

| 7: in B sample neighborhoods: |

| 8: |

| 9: |

| 10: : |

| 11: for each node u in block ℓ: |

| 12: |

| 13: |

| 14: in B: |

| 15: |

| 16: |

| 17: |

| 18: |

| 19: |

| Algorithm A2 Signed SHAP per Class for Edge Features |

| 1: for each edge, target class c |

| 2: |

| 3: for c in classes: |

| 4: |

| 5: SHAP_rows = [] |

| 6: : |

| 7: |

| 8: ) |

| 9: = stack(SHAP_rows) |

| 10: , axis=0) #mean signed contribution vector for class c |

| 11: ), axis=0) #mean absolute contribution vector for class c |

| 12: |

References

- Luša, R.; Pintar, D. Overview of Graph Neural Networks Application on State-of-the-Art Cyber Security Network Threat Detection Techniques. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Software, Telecommunications, and Computer Networks (SoftCOM), Split, Croatia, 18–20 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lo, W.W.; Layeghy, S.; Sarhan, M.; Gallagher, M.; Portmann, M. E-GraphSAGE: A Graph Neural Network Based Intrusion Detection System for IoT. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2022-2022 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium, Budapest, Hungary, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Hu, Z.; Wen, G.; Ma, J.; Zhu, X. Dynamic Graph Convolutional Networks by Semi-Supervised Contrastive Learning. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 139, 109486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.-T.-H.; Kim, H.; Kang, H.; Kim, H. Classification and Explanation for Intrusion Detection System Based on Ensemble Trees and SHAP Method. Sensors 2022, 22, 1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarčević, A.; Pintar, D.; Vranić, M.; Krajna, A. Cybersecurity Knowledge Extraction Using XAI. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, M.A.; Blakseth, S.S.; Rasheed, A.; Salvo Rossi, P. Unsupervised Anomaly Detection for IoT-Based Multivariate Time Series: Existing Solutions, Performance Analysis and Future Directions. Sensors 2023, 23, 2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Song, J.; Noh, J.; Hanh, M.; Kim, J. Explainable Network Anomaly Detection with GraphSAGE and SHAP. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Information and Communication (ICAIIC), Fukuoka, Japan, 18–21 February 2025; pp. 477–482. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, P.; Lu, G.; Li, Y.; Xu, C. EE-GCN: A Graph Convolutional Network Based Intrusion Detection Method for IIoT. In Proceedings of the 2023 5th International Conference on Natural Language Processing (ICNLP), Guangzhou, China, 24–26 March 2023; pp. 338–344. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, W.-L.; Liu, X.; Si, S.; Li, Y.; Bengio, S.; Hsieh, C.-J. Cluster-GCN: An Efficient Algorithm for Training Deep and Large Graph Convolutional Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.07953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1706.02216v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Jiang, A.; Zhou, J.; Li, M.; Kwan, H.K. GraphSAGE-Based Dynamic Spatial-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network for Traffic Prediction. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 11210–11224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903v3. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, M.; Tang, Z.; Han, C. MGAT: Multi-View Graph Attention Networks. Neural Netw. 2020, 132, 180–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, C.; Sun, S.; Zhao, J. MST-GAT: A Multimodal Spatial–Temporal Graph Attention Network for Time Series Anomaly Detection. Inf. Fusion 2023, 89, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leskovec, J. Large-Scale Graph Representation Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), Boston, MA, USA, 11–14 December 2017; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, K.; Liu, Z.; Wang, P.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, K.; Chen, T.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z. A Comprehensive Study on Large-Scale Graph Training: Benchmarking and Rethinking. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.07494v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.-H.; Park, M. FN-GNN: A Novel Graph Embedding Approach for Enhancing Graph Neural Networks in Network Intrusion Detection Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Branco, P. Graph-Based Solutions with Residuals for Intrusion Detection: The Modified E-GraphSAGE and E-ResGAT Algorithms. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.13597v1. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, G.; Lv, H.; Wang, H.; Feng, G. Application of a Dynamic Line Graph Neural Network for Intrusion Detection with Semisupervised Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 699–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Sun, J.; Chen, J.; Alazab, M.; Liu, Y.; Xiang, Y. TCG-IDS: Robust Network Intrusion Detection via Temporal Contrastive Graph Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 1475–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. Node2vec: Scalable Feature Learning for Networks. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoubir, A.; Missaoui, B. Integrating Graph Neural Networks with Scattering Transform for Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.10800v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neupane, S.; Ables, J.; Anderson, W.; Mittal, S.; Rahimi, S.; Banicescu, I.; Seale, M. Explainable Intrusion Detection Systems (X-IDS): A Survey of Current Methods, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 112392–112415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daza, D.; Chu, C.X.; Tran, T.-K.; Stepanova, D.; Cochez, M.; Groth, P. Explaining Graph Neural Networks for Node Similarity on Graphs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.07639v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yu, H.; Gui, S.; Ji, S. Explainability in Graph Neural Networks: A Taxonomic Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2022, 45, 5782–5799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, R.; Bourgeois, D.; You, J.; Zitnik, M.; Leskovec, J. GNNExplainer: Generating Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1903.03894v4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yamada, M.; Tian, Y.; Singh, D.; Yin, D.; Chang, Y. GraphLIME: Local Interpretable Model Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2001.06216v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Cheng, W.; Xu, D.; Yu, W.; Zong, B.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. Parameterized Explainer for Graph Neural Network. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.04573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, A.; Malliaros, F.D. GraphSVX: Shapley Value Explanations for Graph Neural Networks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.10482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkas, S.; Azad, A. GNNShap: Scalable and Accurate GNN Explanation Using Shapley Values. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04829v3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Li, K.; Ji, S. On Explainability of Graph Neural Networks via Subgraph Explorations. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.05152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastropietro, A.; Pasculli, G.; Feldmann, C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, R.; Bajorath, J. EdgeSHAPer: Bond-Centric Shapley Value-Based Explanation Method for Graph Neural Networks. iScience 2022, 25, 105043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, N.; Slay, J. UNSW-NB15: A Comprehensive Data Set for Network Intrusion Detection Systems (UNSW-NB15 Network Data Set). In Proceedings of the 2015 Military Communications and Information Systems Conference (MilCIS), Canberra, Australia, 10–12 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Moustafa, N.; Portmann, M. NetFlow Datasets for Machine Learning-Based Network Intrusion Detection Systems. In Big Data Technologies and Applications; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Westphal, C.; Hailes, S.; Musolesi, M. Feature Selection for Network Intrusion Detection. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2411.11603v1. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, M.; Koutra, D.; Wiens, J. Understanding GNNs and Homophily in Dynamic Node Classification. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.20421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkas, S.; Azad, A. Shapley-Value-Based Graph Sparsification for GNN Inference. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.20460v1. [Google Scholar]

- Shokouhinejad, H.; Higgins, G.; Razavi-Far, R.; Mohammadian, H.; Ghorbani, A.A. On the Consistency of GNN Explanations for Malware Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.16316v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, S.; Kim, S.; Jung, J.; Lee, Y.; Park, C. Self-Explainable Temporal Graph Networks Based on Graph Information Bottleneck. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.13214v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, Y.A.; Wali, S.; Khan, I.; Bastian, N.D. XG-NID: Dual-Modality Network Intrusion Detection Using a Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network and Large Language Model. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2408.16021v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, S.; Hua, C.; Xu, M.; Lu, Q.; Zhu, J.; Chang, X.-W.; Fu, J.; Leskovec, J.; Precup, D. When Do Graph Neural Networks Help with Node Classification? Investigating the Impact of Homophily Principle on Node Distinguishability. In Proceedings of the 37th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023), New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; pp. 28748–28760. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).