1. Introduction

An eye tracking scanpath is the recorded sequence of fixations and saccades that occur as a person views a visual stimulus such as an image, interface, or product. Fixations mark points where the gaze lingers, reflecting attentional focus, while saccades represent rapid eye movements between these points. Together, they form a temporal-spatial trace of visual exploration that reveals not only where and for how long attention is allocated, but also how it shifts over time [

1]. As such, scanpaths provide a window into visual attention, search strategies, and cognitive processes, making their analysis an important method in HCI, visual cognition, and design research.

Building on this value, scanpath analysis has been widely adopted across diverse domains. In interface evaluation and web design, it illuminates how users navigate layouts and interact with content [

2,

3]. In industrial design, scanpaths reveal how consumers explore form, colour, and functional features, and these offer insights that support design decisions to improve usability and aesthetic appeal [

4,

5,

6]. However, interpreting scanpaths remains labour-intensive, expert-dependent, and difficult to scale [

7]. Analysts must manually trace gaze sequences, identify meaningful patterns, and map them to design elements. This process is slow, subjective, and often irreproducible, limiting the integration of eye tracking methods into iterative design workflows and broader adoption in HCI research.

Prior efforts in scanpath analysis predominantly rely on machine learning or deep learning methods that compute spatial or sequential similarity (e.g., ScanMatch [

8], MultiMatch [

9], sequence-edit metrics [

10]). While these techniques effectively quantify structural correspondence, they are not designed to explain the cognitive or visual-behavioural meaning of those patterns. They lack the ability to integrate domain knowledge and thus cannot replace expert reasoning. This creates a critical research gap: how to achieve both computational efficiency and expert-level interpretive depth in scanpath analysis.

Recent advances in multimodal large language models (MLLMs) present a promising opportunity. Vision-centric MLLMs, such like BLIP [

11], LLaVA [

12], and GPT-4V [

13], can perform fine-grained visual description, identify spatial relationships, and leverage sequential and semantic cues [

14]. However, these capabilities remain too generic to capture the specialised temporal-spatial structures of scanpaths or to translate these patterns into actionable design insights.

To fill this gap, we explore whether a carefully designed MLLM-based framework can support reliable, interpretable, and scalable scanpath analysis. We use GPT-4o as a case study because it is a representative model with strong multimodal reasoning ability and support for stepwise structured explanations, which are essential for reconstructing visual attention patterns. Accordingly, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ1: How to build a MLLM-based framework to achieve coherent and design-relevant scanpaths interpretations?

RQ2: How does the proposed approach generate consistent interpretations across repeated analyses of the same stimuli?

RQ3: How closely do interpretations generated by the proposed approach align with expert designers’ scanpath analyses?

To answer these questions, we introduce ETSA, eye tracking scanpath analysis, an approach for adapting MLLMs to scanpath interpretation in the context of industrial product evaluation. Using GPT-4o as a case study, the approach integrates three components: (i) a structural information extraction module that decomposes scanpaths into fine-grained events; (ii) a knowledge base encoding visual-behaviour expertise; and (iii) prompt engineering strategies employing least-to-most [

15] and few-shot chain-of-thought reasoning [

16] to scaffold the model’s outputs. Furthermore, we evaluate the approach through two complementary experiments: a repeated-measures experiment assessed the reliability of the approach’s outputs, and a user study compared the approach’s visual-feature mappings with expert designer annotations. In addition, we conducted an ablation analysis to quantify the contribution of the knowledge base and a cross-model evaluation to assess generalisability across different MLLMs.

This paper makes three contributions:

- (1)

ETSA, a knowledge-grounded approach for scanpath interpretation with MLLMs. We introduce, to our knowledge, the first approach that systematically adapts MLLMs to the specialised tasks of interpreting eye tracking scanpaths. By combining structural parsing of fixation-saccade sequences, a knowledge base of visual-behaviour expertise, and prompt engineering procedures, the approach turns general-purpose vision-language models into task-specific analytic tools while remaining model-agnostic.

- (2)

A methodological integration of structural and semantic reasoning. Unlike prior computational approaches that rely on simplified metrics or pattern-matching, our approach decomposes scanpaths into fine-grained events and embeds them in expert-informed prompts, which enable sequence-aware, design-relevant reasoning. The resulting pipeline produces interpretable, auditable explanations and offers a transferable strategy for other domain-specific visual reasoning tasks in HCI.

- (3)

Empirical evidence of reliability and expert alignment. Across a repeated-measures study and a comparative user study, the ETSA yields high within-approach consistency (0.884), moderate feature-level agreement with expert scanpath interpretations (F1 = 0.476) and no significant differences from expert annotations based on the exact McNemar test (p = 0.545). Together with the ablation and cross-model findings, they suggest that the method can provide reasonably dependable support for scanpath interpretation, contributing to more scalable and consistent analysis practices in eye-tracking research and industrial design workflows.

Table 1 summarise these three contributions.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews related work on eye tracking, usability evaluation, and scanpath analysis.

Section 3 details the proposed ETSA methodology.

Section 4 reports the evaluation studies and results.

Section 5 discusses the findings and their implications, and

Section 6 concludes the paper.

3. Development of ETSA Approach

To answer

RQ1, we used GPT-4o as a case study and proposed ETSA, a knowledge-grounded approach structured around three complementary components (

Figure 2). This approach is design to address the limitations of existing scanpath analysis methods and adapt MLLMs to this specialised task, and the design of this approach is guided by three rationales derived from the literature.

First, accurate scanpath interpretation requires models to handle both spatial and temporal dependencies, which are often lost in conventional metrics. To meet this need, the structural information extraction module decomposes scanpaths into fine-grained events, so to enable precise parsing of fixation sequences and transitions.

Second, generic MLLMs lack the domain-specific grounding that is necessary for reliable reasoning about visual behaviour. To overcome this, the knowledge base module encodes principles of visual attention and design expertise, which allows the ETSA approach to anchor its interpretations in established theoretical constructs rather than surface-level patterns.

Third, effective scanpath interpretation demands multi-stage, structured reasoning rather than superficial, one-shot outputs. The prompt design module therefore employs advanced prompt engineering strategies, such as least-to-most prompting and few-shot chain-of-thought (CoT), to support the approach’s reasoning process. This ensures outputs that are both coherent and aligned with expert analytical practices.

Together, these components form a pipeline that combines the scalability of automation with the interpretive depth of expert reasoning, thereby effectively addressing the key challenges of objectivity, reproducibility, and efficiency in scanpath analysis.

3.1. Structural Information Extraction

Effective scanpath interpretation requires the approach to receive inputs that preserve both the spatial context of visual scenes and the temporal dynamics of gaze behaviour. To this end, we developed a structural information extraction pipeline that transforms raw scanpath images into semantically rich, machine-readable inputs.

First, the original stimulus image is segmented into distinct regions using the Set-of-Mark (SoM) model [

40]. We experimented with multiple levels of segmentation granularity and ultimately adopted a granularity level of 1.8, which provides an effective balance between fine-grained region density and semantic interpretability. As shown in

Figure 3a, each segmented region is automatically assigned a label to support subsequent contextual mapping. All SoM segmentation results were manually inspected by researchers, and images that exhibited noticeable errors (e.g., incorrect splitting of objects or overlapping region labels) were removed from downstream analysis to ensure clean structural input. Subsequently, GPT-4o is employed to generate detailed descriptions of each visual object region, capturing attributes such as colour, size, location, texture, and functionality. These descriptions supply the approach with regional semantic information that would otherwise remain implicit in the raw image.

To incorporate the temporal dimension of gaze behaviour, a Python script (Python 3.10) extracts fixation sequences and durations from the scanpath overlay. As shown in

Figure 3b, fixation coordinates are mapped to their corresponding object regions, which produce a temporally ordered sequence of region-level gaze events. Fixation duration is calculated from the radius of the fixation circles depicted in the scanpath image, with a linear scale in which radius corresponds to duration normalized to a 0–1 interval. This method ensures that both attentional focus and transition dynamics are represented. Coordinates of each fixation point were then mapped to their corresponding SoM-defined visual regions, producing an ordered sequence of region-level gaze events and associated normalized fixation durations.

The final structured output includes: (i) visual scene segmentation with labelled regions; (ii) semantic descriptions of each region; (iii) fixation sequences with mapped object references and durations; and (iv) the original stimulus and scanpath images for reference. Together, these elements provide the approach with an enriched representation that captures both regional context and gaze dynamics, which enable more accurate and interpretable scanpath analysis in subsequent stages.

3.2. Knowledge Base Construction

To strengthen the explanatory capacity of the MLLMs and ensure its outputs reflect established principles of visual attention, we constructed a knowledge base that embeds well-documented domain expertise into the scanpath interpretation process. This resource synthesises theoretical and empirical findings from visual attention research, cognitive psychology, and the eye-tracking literature, with particular focus on studies examining task-free image viewing [

41,

42,

43,

44]. By grounding the approach in naturalistic patterns of visual exploration, the knowledge base ensures that its interpretations remain theoretically consistent and practically relevant.

The knowledge base is organised as a three-level visual hierarchy that captures the progression of attentional processing from low-level perceptual features, through intermediate principles of spatial organisation, to high-level semantic understanding. Each level is linked to characteristic gaze behaviours observed in scanpath research, so to create a structured foundation for reasoning about why particular regions attract or sustain attention. This hierarchical organisation allows the approach to connect visual content to the temporal-spatial patterns of gaze observed in scanpaths, thus providing interpretability that goes beyond surface metrics.

Low-level features capture early perceptual cues (e.g., brightness, colour, size, contrast, texture) that drive bottom-up saliency and initial fixations [

41,

42].

Spatial organisation encodes mid-level compositional principles (e.g., repetition, layout, proximity, alignment, balance, focal points), which shape how viewers traverse a visual scene [

41,

42].

High-level semantics reflect top-down attentional drivers (e.g., faces, symbols, tools, finger direction, conceptual relationships) that anchor attention to meaningful objects and guide search strategies [

43,

44].

Table 2 summarises the hierarchical structure, its attributes, and their associated behavioural implications. By embedding these features, the knowledge base equips the approach with a structured, theory-driven lens for interpreting scanpaths, reducing reliance on arbitrary heuristics and aligning outputs with expert-level reasoning.

The knowledge base is incorporated into the prompt as a structured, hierarchical reference, where each level is presented as an explicit hierarchy followed by a list of attributes and corresponding behavioural descriptions. This structure is preserved so that the model receives the knowledge base in a machine-readable, logically ordered form. Notably, the descriptions are more detailed than that in

Table 2 to ensure the model receives complete and structured guidance during reasoning. An example of this representation is shown in

Figure 4. Additionally, no dynamic feature selection is performed. The entire knowledge base is supplied in each run to maintain stable and reproducible reasoning across images.

3.3. Prompt Engineering Design

A key challenge in adapting MLLMs to scanpath interpretation lies in ensuring that the approach follows a structured and transparent reasoning process rather than producing arbitrary or hallucinated outputs. To address this, we developed a prompt engineering framework that explicitly decomposes the task into stages, constrains the approach’s role and inputs, and enforces consistency in its outputs.

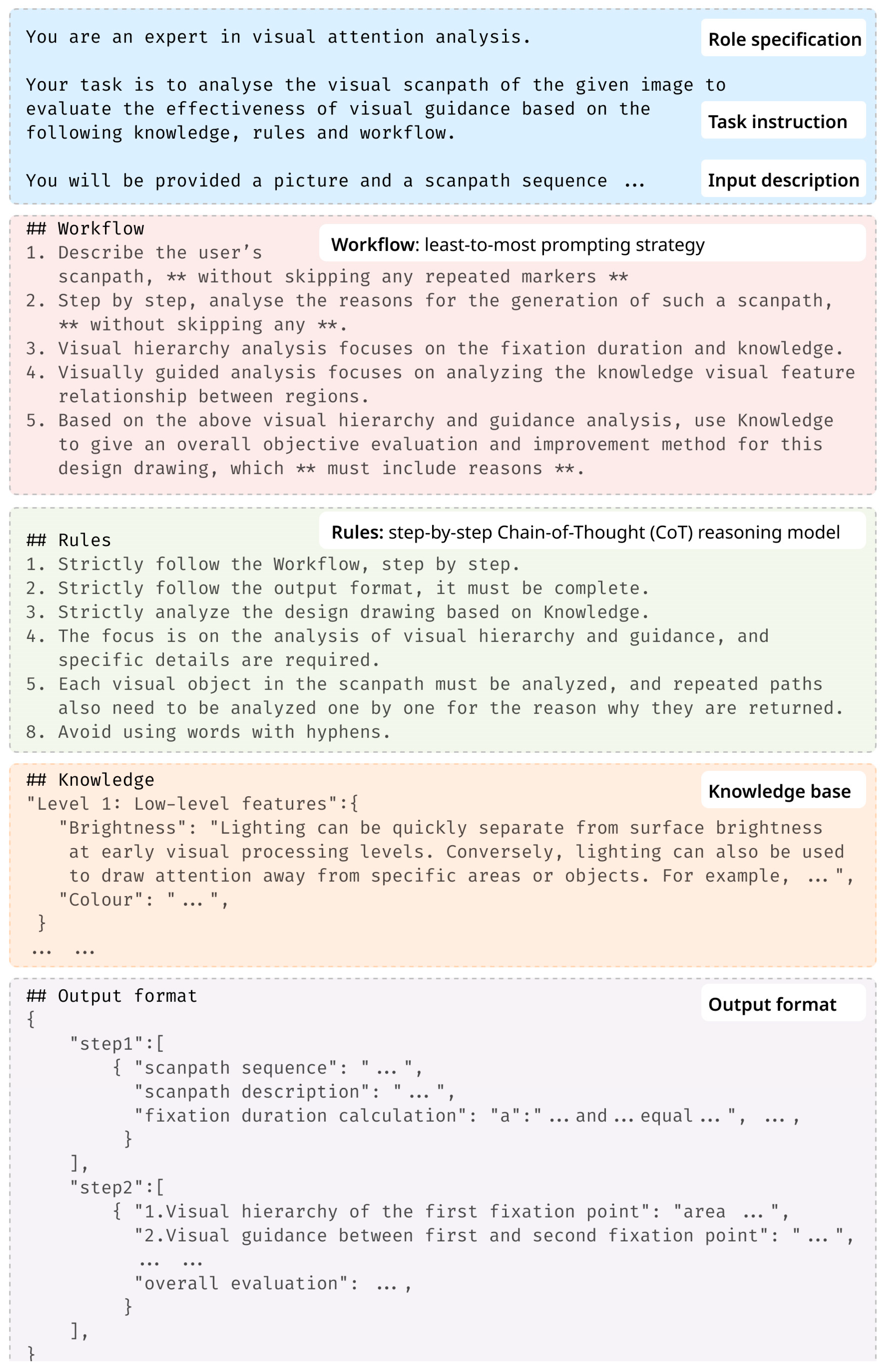

As shown in

Figure 4, the framework consists of seven components: role specification, task instruction, input description, workflow, rules, knowledge base, and output format. The role is set as that of “an expert in visual attention analysis.” The task instruction directs the approach to “analyse the visual scanpath of the given image to evaluate the effectiveness of visual guidance based on the following knowledge, rules and workflow.” The input description includes the original stimulus, the scanpath overlay, the segmentation map, fixation sequences with durations, and detailed descriptions of visual objects. By pairing visual and textual representations, the input design ensures multimodal alignment and provides the approach with both semantic and structural context.

The workflow part employs a least-to-most prompting strategy [

15], which breaks the overall analysis into four subtasks: (1) scanpath recapitulation and fixation duration aggregation; (2) interpretation guided by the visual-attention hierarchy in the knowledge base; (3) holistic synthesis of attentional patterns; and (4) multi-dimensional scoring of visual guidance effectiveness. This stepwise structure enables the approach’s reasoning and mirrors the process typically followed by human experts. To further enhance domain fidelity, the knowledge base of visual-behaviour expertise is injected as contextual information during analysis.

The rules require the approach to adopt a step-by-step Chain-of-Thought (CoT) reasoning model [

16], which ensures that intermediate reasoning steps are explicit and logically coherent. Finally, outputs are constrained to a standardised JSON template with predefined fields and automated field-population mechanisms, thus enhancing reproducibility and enabling systematic comparison across analyses.

By combining role specification, multimodal input structuring, stepwise task decomposition, and explicit reasoning rules, this prompt engineering framework provides a principled mechanism for aligning MLLM outputs with expert analytical practices. It ensures not only more accurate interpretations of scanpaths but also greater transparency and consistency than ad hoc prompting approaches.

3.4. Implementation Details

GPT-4o was accessed through the official API using the vision-enabled model endpoint. All analyses were conducted with a fixed prompt template to ensure consistency across images. The temperature parameter of GPT-4o was set to 0, ensuring deterministic decoding in which the model always selects the highest-probability token. All analyses were performed with identical model parameters and prompt structure. All calls were made using Python 3.10 with the OpenAI client library, and raw outputs were stored without post-generation modification other than formatting for analysis. This setup ensures a controlled and reproducible runtime environment for evaluating the model’s interpretive behaviour.

The overall ETSA workflow is summarised in

Figure 5, which illustrates how the modules of our framework interact.

4. Evaluation of Scanpath Analysis Approach

To answer RQ2 and RQ3, we designed an evaluation strategy targeting two core requirements for scanpath analysis: reliability and effectiveness, to assess the validity of our ETSA approach. Reliability refers to the consistency of outputs across repeated runs of the model—a critical property for reproducibility and trust in automated pipelines. Effectiveness captures the extent to which the approach outputs align with expert interpretations, so to confirm that automated analysis retains the depth and validity of professional judgement. Together, these two dimensions address the key limitations of prior approaches, which have struggled to combine objectivity with expert-level interpretive fidelity.

For empirical testing, we constructed a dataset of exemplary industrial design works. Specifically, 140 industrial product posters from global design Awards (past five years) were selected. These works were chosen because they exemplify professional, high-quality design practice, and offer clear communicative intent, diverse visual compositions, and strong thematic expression. The selection criteria included high image clarity, balanced composition, and identifiable design elements. These ensure that the dataset provides challenging yet representative cases for scanpath interpretation. As shown in

Figure 6, the collected dataset spans multiple industrial design presentation types, including full product views, usage scenarios, detail shots, interaction depictions, and multi-angle representations, thereby it supports a robust evaluation across a broad spectrum of design contexts.

The scanpaths for these images were generated using the well-established IOR-ROI LSTM model [

20], which simulates human-like gaze behaviour and generates visual scanpath. Each generated scanpath includes fixation positions and fixation-circle radii, which we extract from the visualization for structural parsing and relative temporal weighting. Using the IOR-ROI LSTM model ensures a valid and controlled input source for our scanpath interpretation framework.

4.1. Reliability Evaluation

To evaluate the reliability of the ETSA approach outputs, we conducted a reliability study using 50 representative images drawn from the dataset. Each associated scanpath image was submitted to the model 20 independent times, yielding 20 textual interpretations per image. This repeated-sampling design ensures that the evaluation captures both within-image variability and consistency across multiple categories of design stimuli.

For analysis, we measured the semantic similarity of outputs using sentence embeddings derived from the Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) model [

45]. Sentence BERT embeddings provide a high-dimensional representation of linguistic meaning, making them well-suited for detecting underlying semantic consistency despite superficial lexical differences.

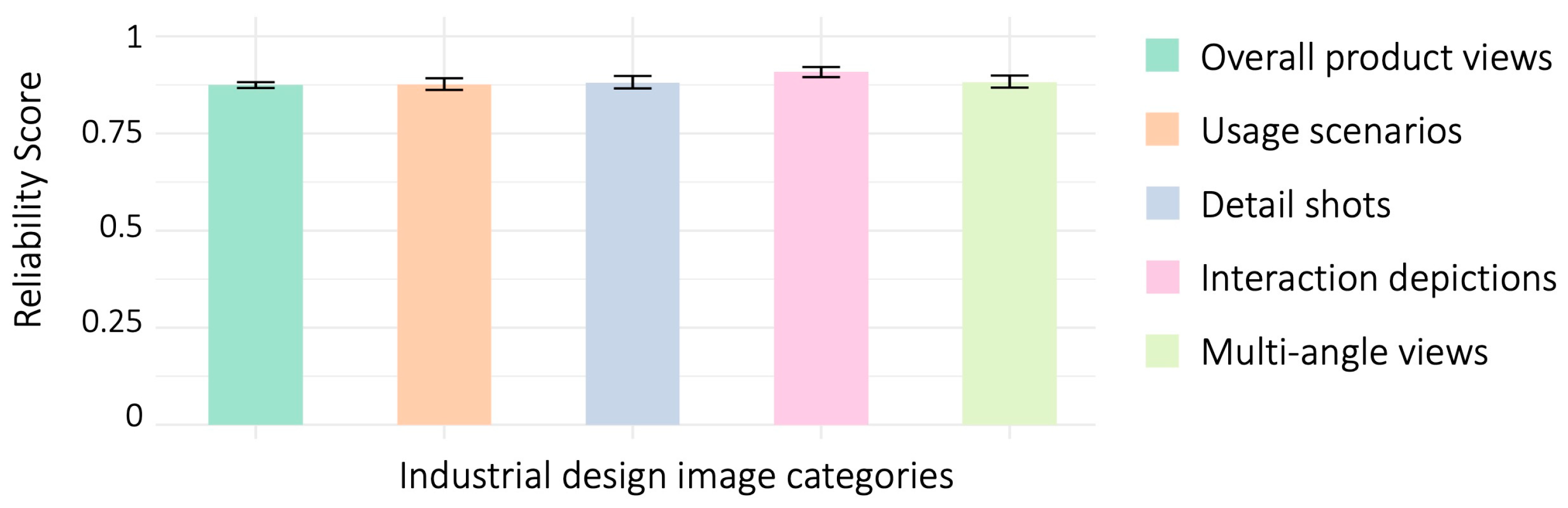

For each image, we computed pairwise cosine similarity across the 20 outputs (190 pairs in total) and averaged these values to produce an image-level similarity score. Next, category-level reliability were derived by calculating the mean and standard deviation of these image-level scores within each category. The overall reliability score was obtained by averaging the 50 image-level scores across the full dataset.

The results indicate a high degree of semantic stability. Across all 50 images, the overall mean similarity was 0.884 (SD = 0.025, 95% CI [0.869, 0.901]), confirming that repeated approach outputs preserved the same underlying content. Category-level analysis showed comparably high values: overall product views (M = 0.874, SD = 0.012, 95% CI [0.867, 0.882]), usage scenarios (M = 0.876, SD = 0.025, 95% CI [0.860, 0.892]), detail shots (M = 0.881, SD = 0.027, 95% CI [0.864, 0.898]), interaction depictions (M = 0.908, SD = 0.022, 95% CI [0.895, 0.922]), and multi-angle views (M = 0.882, SD = 0.025, 95% CI [0.866, 0.898]). Notably, interaction depictions achieved the highest stability, which suggest that the approach is particularly robust when processing gaze data involving human–object interactions.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that the approach consistently generates semantically coherent interpretations, even when prompted multiple times with the same scanpath input. Minor lexical variation was observed across runs, but the preservation of meaning and logical structure confirms the reliability and reproducibility of the approach under repeated conditions (

Figure 7).

4.2. Effectiveness Evaluation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the ETSA approach, we conducted a user study comparing approach-generated scanpath analyses with assessments made by professional designers. This study addressed the key question of whether the approach’s interpretations align with expert reasoning in identifying the visual features underlying fixations and saccades.

4.2.1. Experiment Design and Implements

The study was implemented on a web-based platform (

Figure 8) and administered via online sessions. Each participant completed two tasks per image: (1) annotate at least three visual features that contributed to the observed fixations and saccades, and (2) rate the accuracy of the corresponding model-generated analysis on a 0–3 scale.

To ensure clarity and consistency in feature annotations, the experimenters refined the initial set of 22 visual features identified in the literature review. Redundant or overlapping descriptors were removed, and semantically similar terms (e.g., alignment, proximity, overlap) were merged. This process yielded 10 distinct features: size, colour, brightness, detail, shape, white space, repetition, layout, position, and semantic information.

Six design experts (N = 6, 3 female, 3 males; M

age = 23.8, SD

age = 1.8) were recruited through social media. All participants had substantial design expertise, each having received major international design awards (e.g., iF, Red Dot, K-Design). Although the number of experts is relatively small because of high standard, this sample size is consistent with common practice in design research and expert-judgment studies [

46], where evaluations often rely on small but highly specialized expert groups. Before the experiment, participants were informed about the research purpose, provided written consent, and completed a brief demographic questionnaire. Next, standardized task instructions were given: participants were first asked to examine the scanpath visualization and identify the visual features contributing to each fixation and saccade by selecting at least three relevant features from a predefined list (annotation task), and then to read the corresponding model-generated interpretation and rate its accuracy on a 0–3 scale (evaluation task). During the formal experiment, each participants completed five independent trials, with each trial involving one randomly selected image from a different design category. The whole procedure took approximately one hour per participant, yielding expert annotations and ratings for a total of 30 images.

4.2.2. Data Analysis

To quantitatively assess the alignment between ETSA approach-generated analyses and expert annotations, we developed a semantic mapping and evaluation pipeline that converts textual outputs into a unified feature-based representation suitable for comparison. This pipeline ensures that conceptual correspondence—a critical requirement for analysing descriptive visual reasoning, rather than surface lexical overlap, is evaluated.

Text preprocessing and tokenisation. Approach outputs were tokenised and filtered using an expanded English stop-word list, which is customised to account for domain-specific terminology. Multi-word expressions (e.g., spatial focus) were treated as fixed units to preserve semantic coherence, while compound phrases (e.g., an object designed to be seen or touched) were encoded using sentence-level embeddings. This process improved linguistic precision and avoided token fragmentation that could distort semantic meaning.

Semantic embedding and feature vector construction. Each token was represented as a weighted combination of its contextualised embedding (capturing sentence-level semantics) and its standalone word vector (capturing independent meaning). A 2:8 weighting ratio was adopted to prioritise stable word-level representation while maintaining contextual awareness—an empirically balanced configuration found to enhance semantic matching in pilot tests. For each target visual feature (e.g., colour, balance), a composite feature vector was constructed by averaging its base vector with three semantically related terms, thereby capturing lexical variation and synonymy.

Feature matching using cosine similarity. Cosine similarity was calculated between each token vector and the target feature vectors. Tokens with similarity scores ≥ 0.8 were considered semantically equivalent to the feature, based on prior findings that this threshold reliably indicates conceptual correspondence in embedding space. This process yielded a binary presence/absence vector for each feature, enabling direct comparison between model and expert results.

Evaluation metrics. Model performance was evaluated using standard multi-label classification metrics:

Hamming Loss (HL) measures the proportion of incorrectly predicted labels to the total number of labels:

where

is the total number of samples,

is the total number of labels,

and

denote the true and predicted values of the

label for the

sample, respectively, and

represents the XOR operation.

Precision (P) is defined as the ratio of correctly predicted positive labels to the total number of predicted positive labels:

where

denotes the set of true labels for the

sample, and

represents the set of predicted labels for the

sample.

Recall (R) is the ratio of correctly predicted positive labels to the total number of true positive labels:

F1-score (F1) is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, providing a balanced assessment of the model’s overall performance:

These metrics collectively provide a rigorous, interpretable assessment of the approach’s alignment with expert reasoning, which capture both its ability to identify the correct visual features (precision) and its completeness in recovering all relevant features (recall).

4.2.3. Results

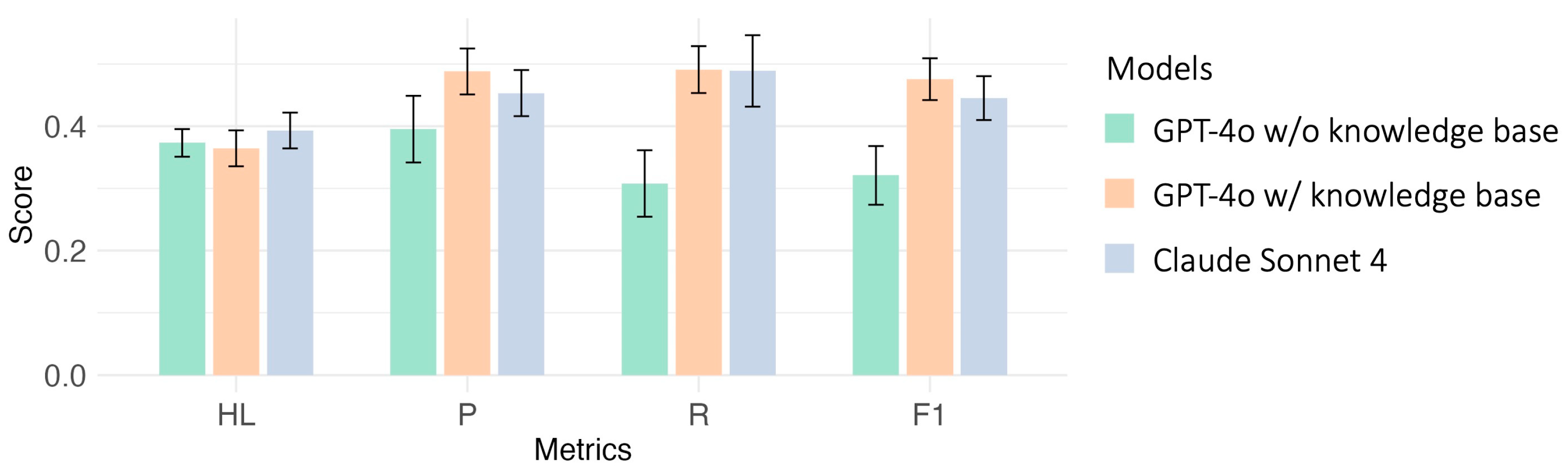

Overall performance. Figure 9 summarises the effectiveness of ETSA approach with different models (GPT-4o with and without knowledge base and Claude Sonnet 4) across four multi-label metrics (HL, P, R, and F1). The results of GPT-4o with knowledge base showed that the average Hamming Loss was 0.364 (SD = 0.080, 95% CI [0.335, 0.414]), which indicate a controlled error rate given the multi-feature, multi-label setting. Precision (M = 0.488, SD = 0.102, 95% CI [0.424, 0.552]) and Recall (M = 0.491, SD = 0.104, 95% CI [0.426, 0.556]) were closely balanced, suggesting the approach neither over-predicts spurious features nor systematically misses expert-identified ones. Their harmonic mean, the F1-score, averaged 0.476 (SD = 0.092, 95% CI [0.417, 0.533]), reflecting moderate, balanced alignment with expert annotations. In practical terms, the ETSA approach recovers most of the visual features highlighted by experts while avoiding excessive false positives—an important trade-off for design analysis where both over- and under-prediction can undermine interpretability.

Ablation study. To examine the contribution of the knowledge base, we compared the performance of the same model (GPT-4o) with and without the proposed knowledge base. As illustrated in

Figure 9, removing the knowledge base substantially decreased performance across the metrics, with notable reductions in Precision (M = 0.395, SD = 0.147, 95% CI [0.304, 0.486]), Recall (M = 0.308, SD = 0.147, 95% CI [0.217, 0.398]) and F1-score (M = 0.320, SD = 0.129, 95% CI [0.241, 0.401]). These results demonstrate that the knowledge base provides clear incremental value, strengthening the model’s ability to retrieve expert-relevant visual features and domain cues. The ablation confirms that the observed improvements stem from the integration of structured domain knowledge rather than stochastic variation or prompt-level artefacts.

Cross-model generalisability. To evaluate whether the proposed ETSA approach depends on a specific MLLM, we further compared GPT-4o with Claude Sonnet 4 (

https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-4, accessed on 26 November 2025) under identical prompt structures and input formats. As illustrated in

Figure 9, both models exhibit similar performance on the four metrics: Hamming Loss (M = 0.393, SD = 0.079, 95% CI [0.364, 0.442]), Precision (M = 0.453, SD = 0.102, 95% CI [0.390, 0.516]), Recall (M = 0.489, SD = 0.157, 95% CI [0.391, 0.586]) and F1-score (M = 0.445, SD = 0.097, 95% CI [0.385, 0.505]). These results indicate that the framework transfers well across different state-of-the-art MLLMs. The consistently similar scores across models suggest strong generalisability and robustness to architectural variations, demonstrating that its effectiveness is not tied to a single MLLM implementation.

Alignment with experts. To test whether the ETSA approach and expert labels differed at the image level, we applied exact McNemar’s test on a 2 × 2 contingency table of agreements/disagreements. The result (χ2 = 0.367, p = 0.545) indicates no statistically significant difference between the two label sets. The corresponding effect size, defined as the difference in proportions, was 0.020 with a 95% CI of [–0.042, 0.082]. Because values of effect size close to zero indicate balanced disagreement, this small effect size suggests that ETSA exhibits no meaningful directional bias relative to expert annotations. While a non-significant result does not prove equivalence, it does provide no evidence of systematic divergence between ETSA outputs and expert judgements.

Perceived accuracy. Design experts rated the ETSA approach’s analyses on a 0–3 scale. The mean score was 2.267 (SD = 0.691) (

Figure 10), which indicates that experts generally regarded the outputs as reliable and practically valuable for interpreting scanpaths.

5. Discussion

This study introduced and evaluated a MLLM-based framework for interpreting eye tracking scanpaths in industrial design. Through two complementary evaluations assessing its reliability and effectiveness, the ETSA approach demonstrated high semantic stability, moderate alignment with expert feature identification, clear benefits from the integrated knowledge base, and strong cross-model generalisation. The approach also shows no detectable distributional difference from expert labels, and was positively appraised by expert designers.

Table 3 summarised the results from these experiments.

Across both evaluations, our findings highlight several mechanisms through which ETSA achieves dependable and interpretable scanpath analysis. First, the ETSA approach produced highly consistent interpretations, indicating that the structured prompt design and domain-grounded reasoning effectively reduced stochastic variability in multimodal generation. This stability is particularly significant given that generative models often exhibit random fluctuations in output, which has historically limited their use in scientific and professional applications. The ETSA approach’s consistency suggests that transparent reasoning, such as least-to-most prompting and chain-of-thought procedures, can meaningfully improve the dependability of large language models for analytic tasks in HCI.

Second, the effectiveness evaluation results indicated a moderate predictive performance of the ETSA approach, and a balanced precision and recall. The findings demonstrated that ETSA achieved identifying the features highlighted by experts while limiting spurious predictions. While the F1 score is moderate (0.476), it should be interpreted in the context of a highly subjective and complex multi-label interpretation task and achieving near-perfect scores would be unlikely even between human experts. The balance between precision and recall is particularly encouraging, as it suggests the model avoids common failure modes of being overly verbose or overly conservative.

Third, the ablation study illustrates the central role of the knowledge base. Remove the knowledge base greatly degraded interpretive quality, demonstrating that domain grounding is essential for aligning model reasoning with expert visual cognition. This effect is also evident in the qualitative behaviour of the model. For example, a representative reasoning excerpt states: “The user’s visual attention switched multiple times between the product and the background, which could be related to factors such as contrast, colour and shading, suggesting …” This reflects how multiple feature-related rules in the knowledge base jointly inform the model’s interpretation.

Moreover, the cross-model comparison suggests that ETSA’s behaviour is not tied to a specific MLLM architecture, underscoring that the effectiveness of ETSA primarily from its structured workflow, including structural information, knowledge base integration, and prompt design, rather than single model’s internal capabilities. Therefore, the ETSA approach functions as a dependable “second reader” in design practice—delivering repeatable, interpretable textual descriptions that correspond with expert judgement while maintaining computational scalability.

Beyond the quantitative results, the findings carry broader implications for human–computer interaction and the design research community. The high semantic consistency across repeated runs supports the notion of hybrid intelligence, where large language models serve as collaborative analytic partners rather than replacements for human expertise. In practical design settings, ETSA could support activities such as providing initial scanpath interpretations during design reviews, highlighting atypical or unexpected gaze transitions for further inspection, or generating baseline analyses that help designers converge on shared interpretations of visual behaviour. For example, during iterative concept development, ETSA could offer rapid assessments of whether different design variants attract attention as intended, allowing experts to focus on higher-level interpretive reasoning. The workflow aligns with the HCI community’s growing interest in collaborative and explainable AI—systems that amplify, rather than automate, human cognition.

The ETSA approach also advances the methodological reproducibility of scanpath analysis. Traditional approaches, whether expert-driven or metric-based, often produce results that are difficult to replicate across studies or practitioners. By encoding visual-behaviour theory into a structured knowledge base and constraining the reasoning process through prompt engineering, the proposed ETSA approach transforms a subjective interpretive task into a transparent and standardised analytical procedure. This methodological consistency contributes to resolving long-standing reproducibility issues in behavioural HCI research and opens the possibility of creating benchmark protocols for visual attention analysis.

Looking ahead, ETSA could be extended into an interactive analytic tool by incorporating real-time expert feedback. Such a system would allow designers to correct, approve, or refine intermediate reasoning steps as the model processes scanpaths, enabling iterative co-analysis. Real-time interaction would also support adaptive knowledge-based expansion as experts contribute new visual cues or design heuristics during use. This interactive loop would deepen the hybrid-intelligence paradigm by enabling mutual adaptation between expert insight and model-level reasoning, creating a collaborative analytic workflow that is both explainable and incrementally improving.

At a conceptual level, the study illustrates how general-purpose MLLMs can be adapted into domain-specific analytic instruments. By grounding the ETSA approach’s reasoning in established visual attention theory, we demonstrate that it is possible to bridge data-driven analysis and cognitive interpretation. This approach may inspire future HCI research on constructing structured reasoning frameworks for other multimodal analytic tasks—such as interface evaluation, information visualisation, or interaction design—where interpretive depth and computational efficiency must coexist.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the evaluation dataset focused primarily on poster-based industrial design stimuli, which may constrain the generalisability of the findings. Potential dataset biases such as cultural conventions, stylistic norms, or differences in visual complexity may also influence model interpretations. Extending the dataset to include sketches, 3D products, physical prototypes, and culturally diverse design materials would provide a more comprehensive validation. Second, the number of experts involved in the effectiveness evaluation was relatively small, future work would help capture a broader range of expert perspectives across different levels of expertise. Third, while the knowledge base was tailored to industrial design, its adaptability to other domains such as UI/UX or architectural design remains untested. Additionally, the framework relies on upstream models such as SoM for segmentation, whose inaccuracies may have a cascading impact on the downstream analysis.

Beyond technical enhancement, future research should explore interactive and explainable extensions of the ETSA approach. Integrating real-time expert feedback could enable iterative reasoning refinement, transforming the model from a static interpreter into an interactive analytic collaborator. Such developments would align with emerging paradigms in participatory and explainable AI, allowing experts to query, critique, and guide model reasoning directly. More broadly, these advances would support the design of AI systems that operate not as black-box predictors but as transparent cognitive partners, capable of co-constructing meaning with human users.

In sum, this research demonstrates that structured prompting, knowledge grounding, and explicit reasoning constraints can transform general-purpose MLLMs into interpretable analytic assistants for complex eye tracking scanpath analysis. The ETSA approach contributes to both methodological rigour and conceptual understanding in HCI by showing how AI systems can participate meaningfully in the interpretation of human visual perceptual behaviour. By bridging computational scalability and expert interpretive depth, this ETSA approach represents a step toward more transparent, reproducible, and collaborative forms of human–AI interaction in design research and practice.