Abstract

Titanium alloys such as Ti-6Al-4V are widely used in aerospace and biomedical fields, but their poor wear resistance and high friction coefficient limit service performance. In this study, laser cladding with La2O3 addition was employed to enhance the surface properties of Ti-6Al-4V, and the underlying mechanisms were systematically investigated by combining experimental characterization with multiphysics simulations. XRD and SEM analyses revealed that La2O3 addition refined grains and promoted uniform phase distribution throughout the coating thickness, leading to good metallurgical bonding. The hardness was 2–3 times higher than that of the titanium alloy substrate when the content of 2–3 wt.% was of added La2O3, while the wear loss ratio was reduced to 0.021% and the average friction coefficient decreased to 0.421. These improvements were strongly supported by simulations: temperature field calculations demonstrated steep thermal gradients conducive to rapid solidification; velocity field analysis and recoil-pressure-driven flow revealed vigorous melt pool convection, which homogenized solute distribution and enhanced coating densification; phase evolution simulations confirmed the role of La2O3 in heterogeneous nucleation and dispersion strengthening. In summary, the combined results establish a mechanistic framework where thermal cycling, melt pool dynamics, and La2O3-induced nucleation act synergistically to optimize coating microstructure, hardness, and wear resistance. This integrated experimental–numerical approach provides not only quantitative improvements but also a generalizable strategy for tailoring surface performance in laser-based manufacturing.

1. Introduction

Titanium alloys, particularly Ti-6Al-4V, find extensive applications in aerospace, automotive, and biomedical fields owing to their high strength-to-weight ratio, excellent corrosion resistance, and good biocompatibility [1,2,3]. However, their practical use is often limited by a high friction coefficient, inadequate wear resistance, and insufficient oxidation resistance under severe operating conditions, which can significantly compromise service performance [4,5,6]. Surface modification is therefore essential to broaden their applicability [7]. Among available techniques, laser cladding stands out due to its high energy density and rapid solidification characteristics. The process generates steep thermal gradients and induces intense melt pool convection, resulting in grain refinement, homogeneous distribution of reinforcements, and reduced defects—all of which collectively improve coating hardness and wear resistance [8,9,10,11]. These inherent advantages underscore the superiority of laser cladding over conventional surface modification methods [12,13]. The introduction of rare-earth oxides such as La2O3 has been shown to refine β grains and strengthen titanium coatings by promoting recrystallization [8,9,10,11,12,13,14]. In laser cladding, La2O3 addition works synergistically with the process to regulate melt pool dynamics and direct microstructural evolution, leading to superior mechanical and tribological performance.

Despite these advancements, the underlying mechanisms of laser cladding are not yet fully elucidated. Existing numerical models have predominantly focused on heat conduction or fluid flow, often neglecting critical phenomena such as phase transitions, Marangoni convection, and recoil pressure. Meanwhile, experimental techniques alone are inadequate for resolving the transient dynamics of the melt pool. To bridge this gap, an integrated experimental-numerical approach is essential to unravel the strengthening mechanisms responsible for the enhanced hardness and wear resistance.

In this study, we employ an integrated experimental and multiphysics simulation approach to investigate La2O3-reinforced coatings deposited on Ti-6Al-4V via laser cladding. A comprehensive coupled model is developed, accounting for laser heat input, phase transition, surface tension effects, buoyancy, and recoil pressure. Complementing this, experimental analyses are conducted to characterize microstructure, microhardness, and wear resistance. Together, this framework not only elucidates the mechanisms behind the enhanced coating hardness and wear resistance but also establishes a generalizable methodology for evaluating surface modification processes.

2. Experimental Details

The substrate material used in this study was Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy, with a diameter of 50 mm and a thickness of 10 mm. The chemical composition of the alloy is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of Ti-based alloy (wt.%).

According to the requirements of the laser cladding process, three types of powder materials were selected for the experiment: titanium powder with a purity of 99.2% and an average particle size of 70 μm, boron powder with a purity of 99.9% and a particle size of 0.5 μm, and La2O3 powder with a purity of 99%. To ensure coating quality, all powders were pre-dried in a vacuum drying oven prior to use, in order to eliminate moisture and prevent pore formation during laser cladding, which could otherwise deteriorate the wear resistance of the composite coating.

The laser cladding equipment used the IPG YLS-5000W fiber laser system and he key technical specifications of this laser system are summarized in Table S1.

To prepare the composite coatings, titanium powder, boron powder, and La2O3 powder were weighed and mixed in a specified ratio, followed by ball milling for 3 h. Then milled powder was mixed with a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) binder and stirred until a uniform paste was formed. This paste was evenly applied onto the surface of Ti-6Al-4V substrates. The coated samples were dried at a constant temperature of 80 °C for 12 h to ensure adhesion and stability. Laser cladding was performed with a laser power of 3000 W, a scanning speed of 5 mm/s, and a track overlap ratio of 50%. The components of the La2O3 powder in the preplaced mixture were 0, 1, 2 and 3 wt% (L0, L1, L2 and L3, respectively). Chemical components of the cladding powders are shown in Table S3.

To analyze the phase composition of the composite coating, an X’Pert PRO X-ray diffractometer was employed. Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm) was used as the X-ray source. The diffraction patterns were recorded over a 2θ range of 10° to 90° with a scanning speed of 10°/min. The operating conditions were set to a tube voltage of 35 kV and a tube current of 25 mA.

The microstructure and the chemical compositions of the composite coating was examined using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi S-3400N, Japan) combined with energy-dispersive spectrometry (EDS).

The microhardness of the composite coating was measured using an HX-1000 microhardness tester (China). The tests were conducted under a load of 500 g with a dwell time of 15 s.

The tribological properties of the composite coating were evaluated using an HT-600 friction and wear tester (China). A 45# steel ball with a diameter of 5 mm was employed as the counterpart material. The tests were conducted under a load of 50 N, at a rotational speed of 100 r/min, with a wear track radius of 3 mm, for a duration of 60 min. The samples were weighed before and after the test to determine the wear loss. In addition, the worn surfaces were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to assess the wear morphology.

3. Numerical Simulation Method

3.1. Geometric Model and Boundary Conditions

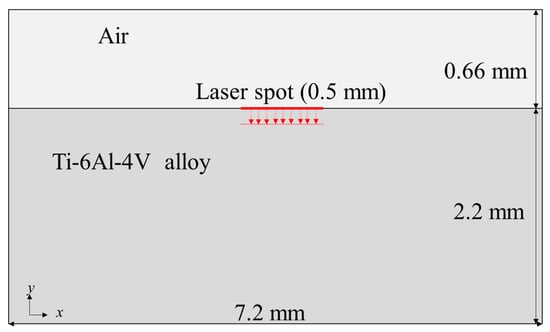

To investigate the formation and evolution of the molten pool under a stationary laser heat source, a two-dimensional thermo-fluid coupled model was established, as shown in Figure 1 [14]. The simulation consists of two parts: (i) a primary model reproducing the experimental conditions (0–1000 ms); and (ii) a localized high-temperature sub-model (0–45 ms) designed to explore vapor recoil effects under extreme thermal environments [15,16,17].

Figure 1.

Domain configuration and fixed heat source location. The red dashed line represents the laser spot.

The simulation domain is 7.2 mm wide and 2.86 mm high, consisting of a 2.2 mm Ti-6Al-4V metal region below and a 0.66 mm air region above. The upper gas region accounts for laser irradiation [18], vapor escape [19], and other heat–flow interactions [20]. A Gaussian point heat source is applied at the interface center (3.6 mm, 2.2 mm) with a radius of 0.25 mm and a power of 3000 W [21,22]. The heat input is loaded as a volumetric source near the metal surface. Adiabatic no-slip conditions are applied to the side boundaries, while the top is treated with free convection and the bottom with an adiabatic wall. The gas–solid interface permits both heat transfer and fluid interaction. Temperature-dependent thermophysical properties are used, and the metal region considers melting [23], vaporization [24], and multiphase flow [25,26,27], with the liquid–gas interface evolution tracked using a phase-field function.

To reduce computational cost, the moving laser heat input with 50% overlap used in experiments was simplified as a fixed Gaussian source applied to a representative cross-section. The main assumptions include: a 2D Gaussian volumetric heat source with exponential decay along the vertical direction [28]; isotropic material properties, neglecting gas expansion and mass loss; and a linear relationship between surface tension and temperature to drive Marangoni convection [29,30,31,32,33,34].

3.2. Multiphysics Coupled Governing Equations

To describe the dynamic evolution of the molten pool, a thermo-fluid coupled model was established, incorporating transient heat transfer, laminar flow, Marangoni convection, buoyancy, and vapor recoil pressure. The corresponding force terms are introduced into the momentum equations, as detailed in Supplementary Material Section S3.

Marangoni convection was modeled by applying a temperature-dependent surface tension along the melt–gas interface. An effective temperature coefficient of surface tension of

was used together with a surface interaction thickness of

Considering the dilute and uniformly dispersed La2O3 addition, its influence was incorporated indirectly through this effective-property modification, which weakens the Marangoni driving force and reproduces the experimentally observed attenuation of surface-driven flow. Further details and full mathematical formulations are provided in Supplementary Material Section S3.

To simulate the temperature evolution in the metal region during laser irradiation, a transient heat transfer model applicable to both solid and liquid phases was established [35]. The governing equation is:

where is the density, is the specific heat capacity, is the temperature, is the velocity vector, is the thermal conductivity, and represents the volumetric heat source due to the laser, which follows a two-dimensional Gaussian distribution:

where is the absorption coefficient, P is the laser power, is the laser spot radius, and are the coordinates of the heat source center, is the laser attenuation coefficient, and is the height of the metallic region.

To account for the effect of latent heat during melting, a temperature-dependent correction term was introduced into the specific heat capacity. Within the phase change temperature range (), it is defined as:

where is the latent heat of fusion, is the melting point, is the phase change interval, and is the specific heat capacity of the liquid phase.

Material parameters were defined as temperature-dependent values, and a locally refined mesh was used to improve accuracy. Solver settings, including time stepping and convergence criteria, are detailed in Supplementary Material Sections S4 and S5.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Microstructural Evolution and Melt Pool Dynamics

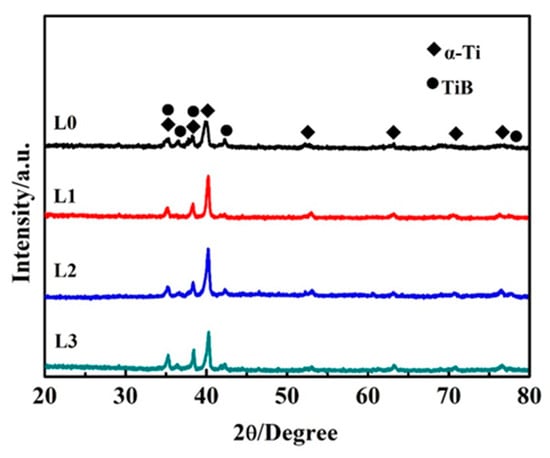

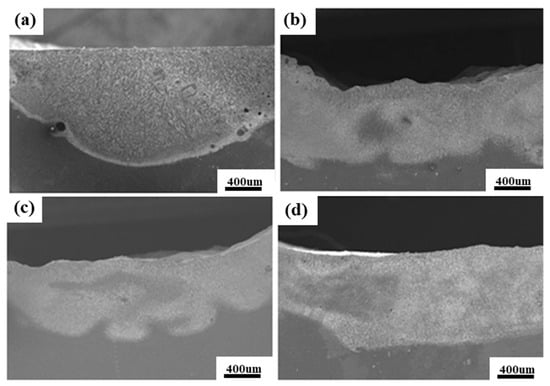

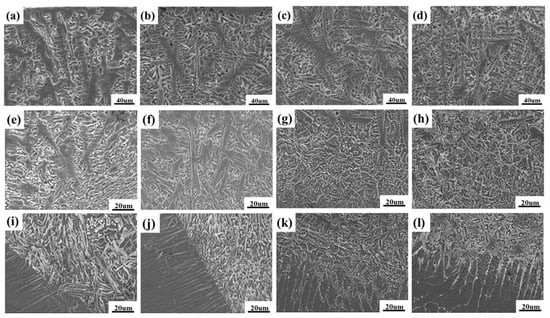

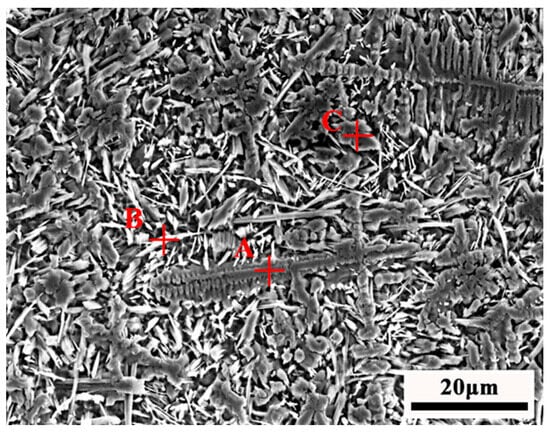

The XRD patterns (Figure 2) reveal that the addition of La2O3 modifies the phase composition of the laser-cladded coatings, stabilizing reinforcement phases and suppressing brittle constituents. Cross-sectional SEM images (Figure 3) further demonstrate that increasing La2O3 content promotes grain refinement and enhances coating uniformity. Depth-resolved SEM observations (Figure 4) indicate that La2O3 effectively suppresses columnar growth, favoring equiaxed grains across the coating thickness, while EDS mapping (Figure 5) confirms its uniform distribution and heterogeneous nucleation role. Table S4 presents the compositional analysis results of the corresponding points. The analysis results indicate that the atomic ratio of Ti to B at point B is close to 1:1, suggesting that the white needle-like and white granular phases in Figure 5 are TiB reinforcement phases.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of composite coatings with different La2O3 contents.

Figure 3.

Cross-sectional SEM images of composite coatings with various La2O3 additions: (a) without La2O3; (b) with 1 wt.% La2O3; (c) with 2 wt.% La2O3; (d) with 3 wt.% La2O3.

Figure 4.

SEM images of the composite coatings at different depths. (a–d) correspond to the top region of the coating, (e–h) to the middle region, and (i–l) to the bottom region. Each row represents samples with different La2O3 contents: without La2O3, and with 1 wt.%, 2 wt.%, and 3 wt.% La2O3, respectively.

Figure 5.

EDS analysis point locations on the top surface of the composite coating with the addition of 3 wt.% La2O3.

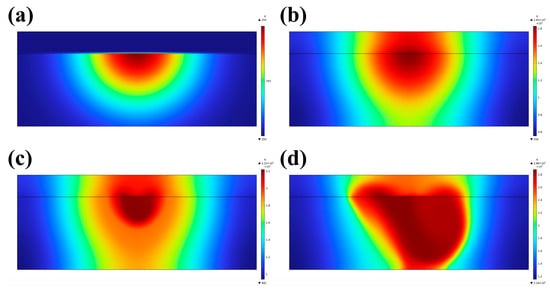

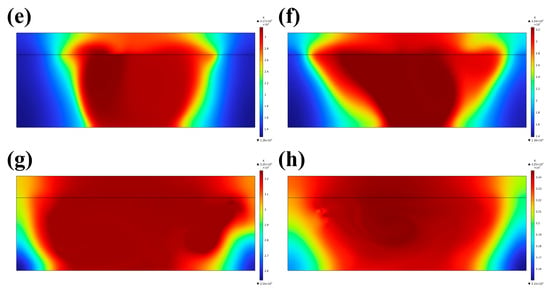

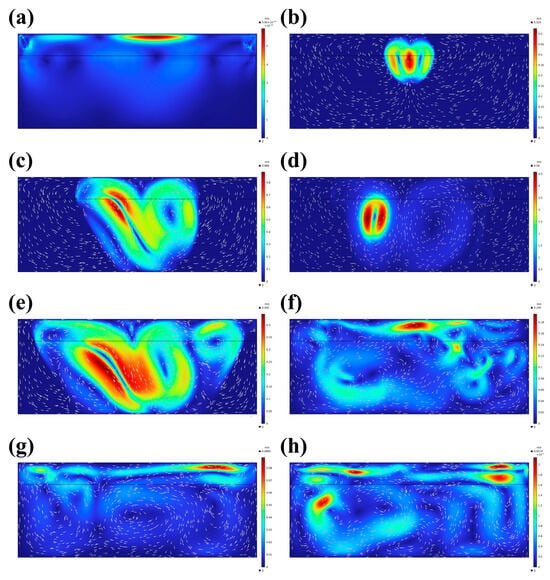

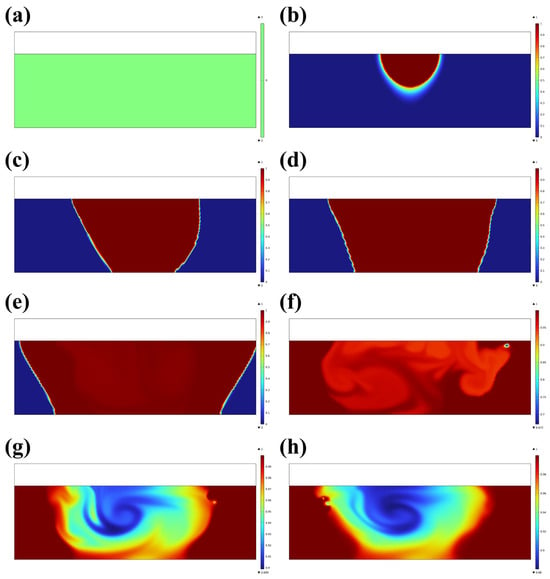

These microstructural evolutions are strongly supported by the multiphysics simulations. The transient temperature field (Figure 6) reveals steep thermal gradients and localized heating, which establish the conditions for rapid solidification during subsequent cooling. This steep gradient environment suppresses columnar dendrite growth and promotes fine-grained solidification. The velocity field (Figure 7) highlights intense melt pool convection, facilitating redistribution of solute and reinforcement particles. The liquid phase evolution (Figure 8) illustrates a dynamically advancing solid–liquid interface, confirming that the coupling of rapid solidification and vigorous convection is essential for structural homogenization.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the temperature field at different time steps: (a) 0 ms, (b) 300 ms, (c) 500 ms, (d) 600 ms, (e) 651.5 ms, (f) 700 ms, (g) 850 ms, (h) 1000 ms.

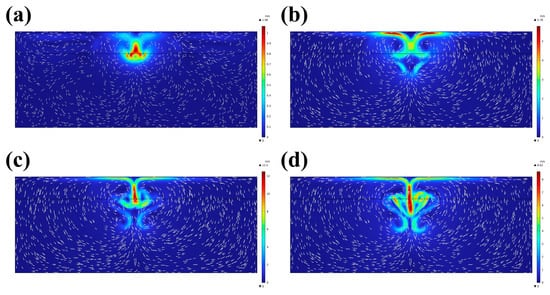

Figure 7.

Evolution of the velocity field at different time points: (a) 0 ms, (b) 500 ms, (c) 600 ms, (d) 651.5 ms, (e) 700 ms, (f) 850 ms, (g) 950 ms, (h) 1000 ms.

Figure 8.

Temporal evolution of the liquid phase distribution: (a) 0 ms, (b) 500 ms, (c) 600 ms, (d) 651.5 ms, (e) 700 ms, (f) 850 ms, (g) 950 ms, (h) 1000 ms. Red denotes the liquid metal (φ ≈ 1), blue denotes solid or vapor (φ ≈ 0), and the gradient indicates the gas–liquid interface.

To further verify the fidelity of the numerical model, the melt-pool geometry extracted from the simulation was directly compared with the experimental cross-sectional SEM image (Figure 3a). The fusion boundary in the simulation was obtained from the liquidus isotherm of the phase-change model, as illustrated in Figure 8h. The simulated melt pool exhibits a width of approximately 3.2–3.6 mm and a penetration depth of 1.2–1.3 mm, which closely match the experimental measurements of ≈3.2 mm in width and ≈1.3 mm in depth. This agreement confirms that the stationary Gaussian heat-source approximation accurately reproduces the melt-pool dimensions under the equivalent local energy input, thereby ensuring the reliability of the subsequent thermal and flow field analyses.

Collectively, the experimental and simulation results demonstrate that grain refinement and uniform phase distribution originate from the synergistic effects of rapid thermal cycling and melt pool dynamics. This mechanistic understanding explains how laser cladding inherently improves coating microstructure and establishes a universal framework for linking processing conditions with enhanced hardness and wear resistance.

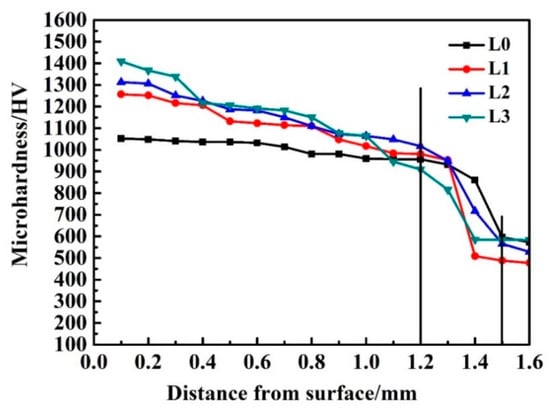

4.2. Hardness Improvement Mechanism

The microhardness profiles (Figure 9) reveal that the surface hardness of the coatings increases progressively with La2O3 addition, reaching a maximum at 3 wt.%. Specifically, when 2–3 wt.% La2O3 was added, the coating hardness was approximately 2–3 times higher than that of the Ti alloy substrate, indicating a remarkable strengthening effect. This enhancement is attributed to refined microstructures and the uniform distribution of reinforcement phases, as observed in the SEM and EDS analyses. The refined grains provide grain boundary strengthening, while the presence of La2O3-induced secondary phases further impedes dislocation motion, collectively accounting for the significant hardness improvement.

Figure 9.

Surface microhardness profiles of laser-cladded coatings with different La2O3 contents. The vertical black lines indicate the interface between the coating and the substrate.

The simulation results provide mechanistic support for these experimental observations. The transient temperature evolution (Figure S1) demonstrates that laser cladding produces steep thermal gradients and high cooling rates, conditions known to suppress coarse dendritic growth and facilitate fine equiaxed grains. The simulated melt pool geometry also indicates that deeper and wider pools enhance thermal gradients and convection intensity, thereby accelerating solidification and reducing structural defects. Such conditions contribute not only to grain refinement but also to improved coating density, which jointly strengthen the material. This rapid solidification correlates with the Hall–Petch effect, explaining the experimental hardness increase. In addition, the phase evolution analysis (Figure S3) shows that La2O3 promotes heterogeneous nucleation and stabilizes reinforcement phases during solidification, thereby strengthening the coating through dispersion hardening.

Overall, both experimental measurements and simulation predictions confirm that the hardness improvement originates from the synergistic effects of grain refinement and dispersion strengthening. This mechanistic understanding highlights how La2O3 addition, combined with the intrinsic thermal features of laser cladding, establishes a robust pathway to enhance coating hardness.

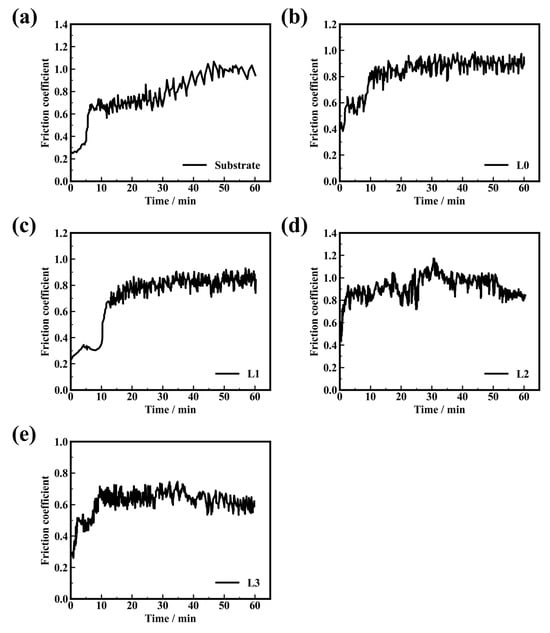

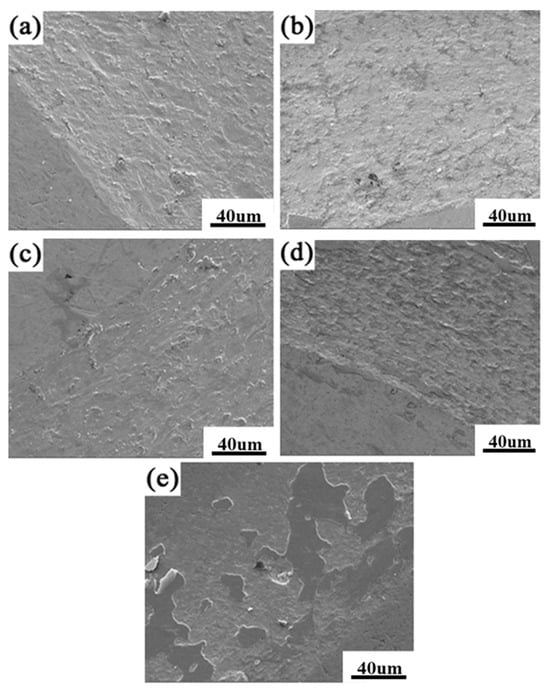

4.3. Tribological Performance and Melt Pool Dynamics

The friction coefficient curves (Figure 10) show that La2O3 addition significantly reduces the steady-state friction coefficient of the coatings compared with the substrate and the coating without La2O3. Correspondingly, worn surface morphologies (Figure 11) indicate a transition in wear mechanism: severe adhesive and plowing wear are observed in the substrate and undoped coatings, whereas La2O3-modified coatings exhibit shallower grooves and fewer delamination traces, reflecting a dominant mild abrasive wear mode. These experimental results confirm that La2O3 effectively enhances the wear resistance of laser-cladded coatings.

Figure 10.

Variation in surface friction coefficient of the composite coatings with different La2O3 contents: (a) Substrate, (b) Without La2O3, (c) With 1 wt.% La2O3, (d) With 2 wt.% La2O3, (e) With 3 wt.% La2O3.

Figure 11.

Worn surface morphologies of the composite coatings with different La2O3 contents: (a) Substrate, (b) Without La2O3, (c) With 1 wt.% La2O3, (d) With 2 wt.% La2O3, (e) With 3 wt.% La2O3.

The numerical simulations provide mechanistic insights into these improvements. The velocity field driven by vapor recoil pressure (Figure 12) demonstrates the formation of upward jets and symmetric vortices, which promote vigorous melt pool stirring and enhance coating densification. The velocity evolution curves (Figure S2) confirm that strong and transient convection develops in the melt pool during laser irradiation, facilitating solute redistribution and reducing compositional gradients. Although Figure S2 primarily reflects the intrinsic convection characteristics of laser cladding, the presence of La2O3 is expected to further intensify such flows by modifying surface tension gradients, consistent with the more homogeneous microstructures observed experimentally. This coupling between convection and reinforcement distribution provides a plausible explanation for the improved wear resistance.

Figure 12.

Evolution of the velocity field driven by vapor recoil pressure (t = 40.875–42.054 ms). (a) Onset of upward jet formation; (b) Symmetrical vortex development; (c) Peak upward velocity; (d) Attenuation of jet momentum.

In summery, both experimental and numerical results establish that the improved wear resistance originates from the synergistic effects of enhanced hardness, coating densification, and homogenized microstructure, all governed by melt pool dynamics during laser cladding. This mechanistic understanding highlights that controlling convection and recoil-pressure-driven flow is a universal pathway to improve tribological performance in laser-processed coatings.

4.4. Overall Mechanism Discussion

The combined experimental and numerical results allow a unified understanding of why laser cladding with La2O3 addition enhances the hardness and wear resistance of Ti-6Al-4V coatings. Microstructural characterization (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4 and Figure 5) together with melt pool simulations (Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8) demonstrated that steep thermal gradients and vigorous convection refine grains and homogenize reinforcement distribution. Hardness measurements (Figure 9) supported by temperature and phase evolution analyses (Figures S1 and S3) confirmed that grain boundary strengthening, dispersion hardening, and improved coating density are the primary contributors to enhanced hardness. Furthermore, tribological tests (Figure 10 and Figure 11) combined with fluid dynamics simulations (Figure 12 and Figure S2) revealed that melt pool stirring and recoil-pressure-driven flow reduce structural defects and stress concentrations, thereby improving wear resistance.

These results collectively establish a mechanistic framework where thermal cycling, melt pool dynamics, and La2O3-induced heterogeneous nucleation act synergistically to optimize coating performance. Importantly, the findings highlight that controlling temperature gradients and convection patterns is a generalizable strategy for tailoring the microstructure and mechanical properties of laser-cladded coatings. Thus, the present study not only elucidates the strengthening mechanisms of La2O3-modified coatings but also provides a universal approach for linking processing conditions, microstructural evolution, and performance in laser-based surface engineering.

5. Conclusions

This work combined experimental characterization and multiphysics simulation to elucidate the mechanisms by which La2O3 addition improves the performance of laser-cladded Ti-6Al-4V coatings. La2O3 addition refined grains and promoted uniform phase distribution, as confirmed by both SEM/EDS observations and melt pool simulations. Surface hardness was significantly improved through grain boundary strengthening, dispersion hardening, and enhanced coating density, supported by thermal and phase evolution analyses. Wear resistance was enhanced by reducing friction and wear loss, which was mechanistically linked to convection- and recoil-pressure-driven coating densification. Collectively, these results establish a mechanistic framework in which thermal cycling, melt pool dynamics, and La2O3-induced heterogeneous nucleation act synergistically to optimize coating properties. This integrated approach provides a generalizable methodology for linking processing conditions with performance, offering guidance for future design of laser-based surface engineering processes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/modelling6040163/s1, Table S1: Technical specifications of the IPG YLS-5000W fiber laser; Table S2: Typical thermophysical properties of different phases; Table S3: Chemical components of the cladding powders; Table S4: Component analysis results of the positions at various points in Figure 5; Figure S1: Typical curves of the temperature evolution process: (a) evolution of the maximum temperature within the laser-heated region over time; (b) temperature profiles along the horizontal direction at the melt pool surface (y = 2.2 mm) at different time points; (c) temporal evolution of temperature at various heights along the laser irradiation centerline (y = 0–2.2 mm); Figure S2: Composite plots of typical velocity evolution curves: (a) evolution of the maximum flow velocity within the laser-heated region over time; (b) velocity profiles along the horizontal direction at the melt pool surface (y = 2.2 mm) at different time points; (c) temporal evolution of flow velocity at various heights along the laser irradiation centerline (y = 0–2.2 mm); Figure S3: Composite plots of typical phase evolution curves: (a) evolution of different phase areas within the laser-heated region over time; (b) profiles of phase 2 along the horizontal direction at the melt pool surface (y = 2.2 mm) at different time points; (c) temporal evolution of phase 2 at various heights along the laser irradiation centerline (y = 0–2.2 mm).

Author Contributions

Data curation, M.D. and Y.W.; writing—original draft preparation, M.D.; conceptualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Y.Z.; validation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z.; methodology, G.H.; project administration, Y.W.; investigation, W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Class III Peak Discipline of Shanghai—Materials Science and Engineering (High-Energy Beam Intelligent Processing and Green Manufacturing), and also by the Henan Provincial Higher Education Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project (Grant No. 2021SJGLX536) and the Henan Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Research and Practice Project (Graduate Education, Grant No. 2023SJGLX092Y). The APC was funded by the authors.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nabhani, F. Machining of aerospace titanium alloys. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2001, 17, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Froes, F.H.; Friedrich, H.; Kiese, J.; Bergoint, D. Titanium in the family automobile: The cost challenge. JOM 2004, 56, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Best, S.M.; Bonfield, W.; Buckland, T. Development and characterization of titanium-containing hydroxyapatite for medical applications. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolyarov, V.V.; Shuster, L.S.; Migranov, M.S.; Valiev, R.; Zhu, Y. Reduction of friction coefficient of ultrafine-grained CP titanium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, X.; Leyland, A.; Song, H.W.; Valiev, R.Z.; Zhu, Y.T. Thickness effects on the mechanical properties of micro-arc discharge oxide coatings on aluminium alloys. Surf. Coat. Technol. 1999, 116–119, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojtěch, D.; Bártová, B.; Kubatík, T. High temperature oxidation of titanium–silicon alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2003, 361, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chu, P.K.; Ding, C. Surface modification of titanium, titanium alloys, and related materials for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2004, 47, 49–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.Q.; Han, Y.F.; Lü, W.J.; Mao, J.-W.; Wang, L.-Q.; Zhang, D. Effect of solid carburization on surface microstructure and hardness of Ti-6Al-4V alloy and (TiB+La2O3)/Ti-6Al-4V composite. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 23, 1871–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Han, Y.F.; Li, J.X.; Qiu, P.K.; Sun, X.L.; Lü, W.J. Microstructure characteristics of ECAP-processed (TiB+La2O3)/Ti-6Al-4V composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 728, 885–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, L.J.; Ning, J.; Li, S.; Na, S.J. Effect of addition of micron-sized lanthanum oxide particles on morphologies, microstructures and properties of the wire laser additively manufactured Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 799, 140475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, K.; Qiu, D.; Niu, W.J. Additive manufacturing of high-strength commercially pure titanium through lanthanum oxide addition. Mater. Charact. 2021, 175, 111074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Long, X.; Zhang, H.M.; Zhu, W.; Chen, Z.; He, D.; Song, N.; Wang, X. Effects of La2O3 contents on microstructure and properties of laser-cladded 5 wt% CaB6/HA bioceramic coating. Biomed. Mater. 2022, 17, 015009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Liang, J.; Hu, H.; Li, Q.; Chen, H. Effect of lanthanum oxide on the microstructure and properties of Ti-6Al-4V alloy during CMT-additive manufacturing. Crystals 2023, 13, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Wang, H.; Huang, W.; Chen, X.; Lian, G.; Wang, Y. Microstructure and mechanical properties of LaB6/Ti-6Al-4V composites fabricated by selective laser melting. Metals 2023, 13, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farotade, G.A.; Adesina, O.S.; Kolesnikov, A.; Popoola, A.P.I. Computational analysis of heat transfer within a Ti-6Al-4V alloy substrate during laser cladding process. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 046516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, M.; Gao, Q.; Gao, Z.; Zhan, X. Numerical simulation to study the effects of different laser cladding sequences on residual stress and deformation of Ti-6Al-4V/WC. J. Mater. Res. 2021, 36, 1109–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Jiang, H.; Lei, Z.; Bai, R.; Yu, S. Analysis of the residual stress in additive manufacturing of Ti-6Al-4V. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2206, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, P.; Jin, L.; Yan, B.; Zhu, L.; Yao, J.; Jiang, K. Numerical simulation and experimental investigation of the effect of three-layer annular coaxial shroud on gas-powder flow in laser cladding. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 84, 735–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praveen, J.P.; Kothuru, B.; Kumari, M.A.; Shaw, S.M.; Boppana, N.; Mahaboob, B. Numerical simulations on LBW of thin sheets of Ti-6Al-4V alloy using the Taguchi method to determine ideal processing parameters. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 559, 02007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpat, Y. Temperature dependent flow softening of titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V: An investigation using finite element simulation of machining. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2011, 211, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayat, M.; Thanki, A.; Mohanty, S.; Witvrouw, A.; Yang, S.; Thorborg, J.; Tiedje, N.S.; Hattel, J.H. Keyhole-induced porosities in laser-based powder bed fusion (L-PBF) of Ti-6Al-4V: High-fidelity modelling and experimental validation. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairallah, S.A.; Anderson, A.T.; Rubenchik, A.; King, W.E. Laser powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing: Physics of complex melt flow and formation mechanisms of pores, spatter, and denudation zones. Acta Mater. 2016, 108, 36–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, D.; Gao, Y.; Pan, H.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, J.; Xiong, G.; Zhang, H. Numerical simulation on porosity formation and suppression in oscillation laser welding of Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Laser Appl. 2024, 36, 042039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snavely, R.A.; Key, M.H.; Hatchett, S.P.; Cowan, T.E.; Roth, M.; Phillips, T.W.; Stoyer, M.A.; Henry, E.A.; Sangster, T.C.; Singh, M.S.; et al. Intense high-energy proton beams from petawatt-laser irradiation of solids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 2945–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K.; Reinhard, A.; Stefan, P. Ironing Appliance Comprising a Boiling Compartment in Which the Steam Produced Can Freely Escape to an Ironing Instrument. EP Patent EP2115210A1, 4 February 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.L.; Wang, T.A.; Weglarz, R.P. Interactions between gravity waves and cold air outflows in a stably stratified uniform flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 1993, 50, 3579–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.S.; Na, S.J. A study on the prediction of the laser weld shape with varying heat source equations and the thermal distortion of a small structure in micro-joining. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2002, 120, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Yu, X.; Xie, Z.Q.; Zhang, J.-P. A novel virtual sample generation method based on Gaussian distribution. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2011, 24, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulignati, P.; Kamenetsky, V.S.; Marianelli, P.; Sbrana, A.; Mernagh, T.P. Melt inclusion record of immiscibility between silicate, hydrosaline, and carbonate melts: Applications to skarn genesis at Mount Vesuvius. Geology 2001, 29, 1043–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehrborn, C. Photoselective potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser vaporization of the benign obstructive prostate: Observations on long-term outcomes. Yearb. Urol. 2006, 2006, 122–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, H.; Trevisan, L.; Illangasekare, T.H. Evaluation of relative permeability functions as inputs to multiphase flow models simulating supercritical CO2 behavior in deep geologic formations. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2015, 42, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. Laser attenuation of the focused powder streams in coaxial laser cladding. J. Laser Appl. 2000, 12, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindlin, R.D. Second gradient of strain and surface-tension in linear elasticity. Int. J. Solids Struct. 1965, 1, 417–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, C.H.; Wuest, W. Experiments on the transition from the steady to the oscillatory Marangoni-convection of a floating zone under reduced gravity effect. Acta Astronaut. 1979, 6, 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sifleet, W.L.; Dinos, N.; Collier, J.R. Unsteady-state heat transfer in a crystallizing polymer. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1973, 13, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).