Abstract

High-space industrial facilities often store substantial quantities of flammable volatile organic compounds (VOCs), posing significant fire and explosion hazards. This study employed computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to investigate the migration and diffusion characteristics of VOCs in a semi-enclosed, high-space wood chip fuel storage shed. A three-dimensional transient numerical model was developed based on a real-scale industrial prototype, incorporating the Realizable turbulence model with species transport equations. Validation using experimental data demonstrated good agreement between the model and experimental results, with a maximum relative error of 5.0%. A systematic assessment of key parameters was conducted, including time, ambient temperature, relative humidity, wood chip stack height, and VOCs type. Evaluation metrics comprised the surface-average mass fraction and the proportion of areas exceeding 5% of the lower explosive limit (LEL). The results show that peak concentrations occurred at 25~27 min. The system reaches quasi-steady state after 60 min. At 300~304 K, the lowest peak mass fractions are observed (0.31% and 0.43% at 19 m), yet the area exceeding 5% LEL was the largest. Moderate humidity (40~60%) reduces peaks by 0.06~0.11%. A stacking height of 7.5 m reduces peak values to 0.21% (left) and 0.28% (right), while a 10 m height increases the hazardous area to 48.87%. Low-polarity VOCs (C10H16) spread widely (34.10% exceeding 5% LEL area), whereas polar VOCs (C15H26O) accumulated locally (4.48%). These findings provide theoretical guidance for VOC hazard control and ventilation optimization in high-space biomass fuel storage facilities.

1. Introduction

As global energy consumption rates continue to rise, the issue of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions has become increasingly severe, prompting governments and international organizations to accelerate the development of emission reduction policies and regulatory frameworks [1]. The research indicates that the systematic replacement of fossil fuels with renewable energy sources can significantly reduce net anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, thereby effectively mitigating the progression of climate change [2]. As one of the earliest renewable energy sources utilized by humankind, biomass energy is widely regarded as a key component of future low-carbon energy systems due to its carbon cycling characteristics and potential for sustainable utilization [3]. For many years, the annual global production of wood pellets has been steadily increasing, rising from 27 million metric tons in 2015 to approximately 47 million metric tons in 2020 [4]. With the large-scale application of wood chips in the energy sector, safety incidents arising during their production, storage, and transportation have increasingly drawn attention. Exhaust gases and self-heating have been identified as the primary challenges in the large-scale storage and transportation of wood pellet fuel [5,6]. The storage of large quantities of wood chips in enclosed spaces generates multiple gases, including carbon monoxide (CO), CO2, methane (CH4), and various volatile organic compounds (VOCs) such as hexanal and monoterpenes [7]. Among these emissions, VOCs have drawn particular attention due to their complex chemical behavior and dual impacts on both the environment and human health.

In recent years, extensive research has focused on the variations in Biogenic VOCs (BVOC) emissions among tree species, the mechanisms of environmental regulation, and the differences observed during wood processing and storage [8]. Bao et al. [9] evaluated the BVOC emission characteristics of 357 plant species. The results indicated that 89% of deciduous trees emitted isoprene, monoterpenes, and sesquiterpenes, whereas only 53% of evergreen trees did so. The effects of environmental stress on the emission of different BVOC types exhibited distinct compound specificity. Lun et al. [10] reviewed the influencing factors of BVOC emissions in Asia. The study indicated that BVOC emissions were significantly affected by vegetation type, environmental factors, and anthropogenic disturbances. Yang et al. [11] experimentally investigated the effect of temperature on BVOC emissions. The results showed that the moderately elevated temperature between 303 K and 313 K significantly enhanced BVOC emissions, whereas exceeding the optimal temperature range led to a decrease in BVOC emissions. Lüpke et al. [12] studied the effects of summer drought on VOCs emissions, and found that isoprene emission rates decreased from 0.60 nmol/(m2·s) to 0.19 nmol/(m2·s), a 70% reduction, but recovered to normal levels after humidification.

In specific studies on the impact of ventilation on VOCs emissions, scholars have made significant discoveries through experiments [13]. Caron et al. [14] investigated the effect of ventilation on VOCs emissions from wood particleboard based on experimental data. Results indicated that when the air change rate increased from 2.5 air changes per hour to 5.5 air changes per hour, the formaldehyde release rate significantly increased by 28% (from 214.6 to 274.2 ). Hormigos-Jimenez et al. [15] proposed a method for determining ventilation rates based on total volatile organic compounds (TVOC) emissions. Their research indicates that TVOC concentrations in newly renovated buildings peak during the initial period (within 3 months), requiring a ventilation rate of 1.28 air changes per hour. This requirement decreases to 0.31 air changes per hour after 2 years. Domhagen et al. [16] employed passive sampling and ventilation humidity monitoring to determine that indoor VOCs concentrations are primarily governed by absolute humidity and ventilation rates, with temperature exerting a lesser influence. Joo et al. [17] analyzed the effects of ventilation patterns and space occupancy on VOCs removal efficiency. Results indicated that introducing 50% fresh air reduced TVOC by 55.1%. The highest TVOC concentration observed on occupied days was 919.2% higher than that on unoccupied days during the same period.

CFD has been proven to be an effective and powerful method to simulating three-dimensional visualization pollutant concentration fields [18]. Caron et al. [19] employed the dynamic distribution patterns of various VOCs emitted from particleboard in ventilated chambers using a combined experimental and numerical simulation approach. Their primary finding was that simulated concentrations of key VOCs such as formaldehyde and acetone showed good agreement with experimental data. Zhang et al. [20] investigated the influence of ventilation parameters on VOCs purification efficiency using CFD technology. Through comparative analysis with the Langmuir–Hinshelwood kinetic model, they found that their predictions deviated from the L–H model by only 0.8% on surface-average while reducing computational time by 99%.

Egedy et al. [21] conducted CFD simulations on VOCs removal processes in industrial silos, ultimately determining that a purge flow rate of 3 m3/h at 353 K represents the optimal operating condition. This configuration ensures efficient removal while minimizing energy consumption. Malayeri et al. [22] investigated the effect of passive removal materials (PRM) on formaldehyde concentration distribution in a test chamber by establishing a CFD model. Results indicated that the presence of PRM significantly reduced indoor formaldehyde levels under various air supply configurations, with formaldehyde removal efficiency in the breathing zone increasing by 38.4% to 47.2%. Yoo et al. [23] developed an optimization design method for bus stop air purification systems, determining the optimal layout for purification equipment, with the system achieving a maximum purification efficiency of 35.9%. Teodosiu et al. [24] simulated VOC emissions from office equipment under cold, neutral, and warm supply air conditions, confirming that variations in supply air temperature induce highly non-uniform concentration distribution fields and exposure levels. Nandan et al. [25] analyzed the release characteristics of VOCs in printing plants. Results indicated that as operating time, temperature (308~313 K), and printing speed (120~200 copies per hour) increased, emissions of volatile organic compounds, benzene, and toluene rose from 0.09 to 1.13 ppm, 0.17 to 1.87 ppm, and 30 to 235 ppm (by volume), respectively.

In summary, significant progress has been made by domestic and international scholars on VOCs emission characteristics and ventilation control using CFD and experimental methods. However, few published studies have involved the VOCs diffusion and migration in the semi-enclosed high-space industrial facilities. First, many studies focus on small-scale or conventional spaces (such as offices and laboratories), lacking systematic analysis of the unique airflow organization, temperature stratification, and pollutant distribution pattern characteristic in the semi-enclosed high-space industrial facilities. Secondly, quantitative research on VOCs migration pathways, concentration distribution, and safety risks in semi-enclosed high-space industrial facilities under mechanical ventilation conditions remains scarce. Therefore, there is a lack of effective methods suitable for such scenarios.

Based on above analysis, the focus of this study is the migration and diffusion characteristic of VOCs in the semi-enclosed high-space wood chip fuel storage shed. A CFD model based on a study case of the semi-enclosed high-space wood chip fuel storage shed located in Belgium was built and proposed. The surface-averaged mass fraction, LEL, and the proportion of areas exceeding 5% LEL were used as evaluation indexes. Then, the influence of time, temperature, fresh air humidity, wood chip stacking height, and VOCs type on the migration and diffusion of VOCs were investigated and compared based on the simulated data. The primary objective of this study is to analyze the migration patterns of VOCs released from known sources within semi-enclosed high spaces and to evaluate the impact of factors such as ventilation. While the CFD methodology employed is standard, the innovation of this work lies in its novel application to a critical and underexplored industrial scenario. Specifically, this research provides the following: a high-fidelity, three-dimensional analysis of transient VOC dispersion and explosion risk in a real-scale, semi-enclosed wood chip storage shed—a scenario rarely investigated in prior literature; systematic quantification of the non-intuitive effects of key operational parameters (e.g., time, temperature, stacking height, VOC type) on both local concentration peaks and the spatial extent of hazardous areas; novel, quantitative engineering insights and design guidelines for ventilation optimization and hazard control tailored to high-space biomass storage facilities, filling a critical gap between fundamental CFD simulation and practical industrial safety.

2. Numerical Model

2.1. Physical Model and Assumptions

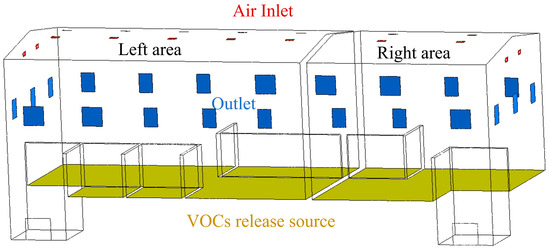

In this study, the building prototype is a wood chip fuel storage shed located in Belgium. The wood chip fuel storage shed consists of two independent spaces separated by a 200 mm partition, with no airflow exchange between them. The physical model is based on wood chip alternative fuel storage shed. All geometric modeling was completed within the Ansys 2022 R1 platform, utilizing SpaceClaim for geometry creation. Figure 1 gives the numerical model. As shown in Figure 1, in the ventilation system design, the model uses red-marked areas to indicate the air inlet, which is directly connected to the outside environment via rainproof louvers. The blue-marked area indicates the mechanical exhaust outlet, equipped with a variable-frequency drive fan system that conveys pollutant-containing gases to the treatment unit. The yellow-marked area in the model represents the upper surface of the wood chip accumulation layer, defined as the VOCs release source.

Figure 1.

Numerical computational modeling of the wood chip alternative fuel storage shed.

Table 1 shows the specific dimensions of the model. The airflow ratio between outlet 1 and outlet 2 is 1:0.7. The upper edge of the inlet is 2 m from the ridge. The upper edge of the outlet is 5.4 m from the eaves.

Table 1.

Model dimensions.

To ensure the convergence efficiency of the simulation process and reasonably control computational resource consumption, the following assumptions are adopted in the model while maintaining acceptable computational accuracy [26]:

(1) The emission source was modeled as a uniform surface at the top of the wood chip pile, neglecting three-dimensional geometric details. The initial VOCs concentration was set to zero, and a constant emission rate was assumed over time. In view of the massive scale of wood chip piles, accurately resolving their internal volatilization processes poses significant challenges. The uniform surface source method is a reasonable approach, as it effectively captures the transport processes of primary pollutants while avoiding the high computational costs associated with resolving complex source details;

(2) Air was modeled as an incompressible ideal gas with constant density, and the thermophysical properties of the VOC-air mixture (including specific heat capacity, thermal conductivity, and dynamic viscosity) were held constant. This assumption simplifies the governing equations by neglecting fluctuations in physical properties caused by temperature and humidity variations. For the large-scale low-velocity flows and macroscopic pollutant transport processes examined in this study, the impact of air property changes due to temperature and humidity variations on the overall flow field and concentration distribution is negligible;

(3) The wood chip pile was modeled as a static porous medium entity with uniform porosity and constant bulk density (500 kg/m3). Air within internal voids is excluded, as it simulates focused macroscopic diffusion; the influence of air within the core on overall concentration is negligible. Its complex internal geometry and the resulting potential flow and temperature heterogeneity were not analyzed. This simplification aimed to focus on pollutant transport patterns within the macroscale spatial domain rather than microscopic processes within the pile interior;

(4) Material properties of building envelopes (walls, roofs)—such as thermal conductivity and VOCs adsorption capacity—are neglected in this model. All wall surfaces are assigned non-slip, thermally insulated boundary conditions. This assumption is based on preliminary analysis indicating that, at the macroscopic ventilation and diffusion timescales of interest in this study, the influence of wall material properties on overall airflow organization and concentration fields is a secondary factor.

2.2. Boundary Conditions

In simulations of indoor pollutant migration and diffusion processes, the accurate definition of boundary conditions is critical for obtaining reliable results. This study employs a three-dimensional transient numerical method, utilizing finite volume calculations on a structured grid. The simulation uses a pressure-based solver and accounts for gravity. For turbulence modeling, the Realizable model is used to capture indoor airflow characteristics with improved accuracy. To simulate the distribution of VOCs concentrations, the species transport model is activated, with the inlet diffusion defined using the species transport method. For material property settings, a multi-component gas mixture of air, water vapor, and VOCs were defined employed. This study employs Aspen Plus V15 process simulation software with the PENG-ROB equation of state. The core thermophysical properties for the VOCs were sourced from the software’s integrated pure-component database, as detailed in Table 2. All properties are calculated based on a reference state of 300 K and 1 bar.

Table 2.

Physical properties of VOCs. (The , viscosity, and thermal conductivity were retrieved from the Aspen Plus V15 pure-component property database. The diffusion coefficients were estimated using the Fuller–Schettler–Giddings method.)

The air inlet was set as a pressure inlet, while the air outlet was defined as a mass-flow-outlet. The outlet quality flow rate is based on an air exchange rate of 8/h. The pollutant release source was set as a mass-flow-inlet. Considering its self-heating during accumulation, the temperature inside the pile shed may exceed 323 K [27]. Accordingly, its volatilization rate references research findings by Chen et al. [28]. The camphor wood, characterized by higher VOCs release, is selected as study sample of wood chips. Under heating at 323 K, the TVOC release within 25 h is 3.8 g/kg, while the release rate of camphor (C10H16O) is approximately 45% that of TVOC (0.068 g/(kg·h)); wood chip density was calculated at 500 kg/m3. The temperature of the VOCs release source at the surface of the wood chip pile is set to a constant 323 K. Due to the lack of consideration for mass transfer limitations under actual stacking conditions, the calculated release rate was overestimated. The solution method was the SIMPLE algorithm to perform pressure-velocity-coupled calculations, with spatial discretization using a second-order upwind scheme. The sub-relaxation factor and convergence criteria for residuals of each equation are specified in Table 3. All residuals and control factors are dimensionless.

Table 3.

Residuals and control factors.

2.3. Control Equations and Turbulence Model

The migration of VOCs within the semi-enclosed high-space wood chip fuel storage shed adheres to the laws of mass conservation (continuity equation), momentum conservation (Navier–Stokes equations), energy conservation, and the mass balance equation for components. The standard forms of these fundamental governing equations for fluid motion employed in this study are well-established and have been successfully applied in similar CFD studies of environmental ventilation and VOC dispersion [29,30].

Mass continuity equation:

Momentum conservation law:

Energy conservation equation:

Mass balance equation:

where is the fluid density, kg/m3; is time, s; , , represent the velocity components in the , , axes, respectively, m/s; is the velocity vector, m/s; denotes the spatial gradient operator; is the dynamic viscosity, Pa·s; g is the gravitational acceleration, m/s2; is the total energy per unit mass, J/kg; is pressure, Pa; is thermal conductivity, W/(m·K); is temperature, K; is the specific enthalpy of species , J/kg; is the mass diffusion flux of species , kg/(m2·s); denotes the viscous stress tensor, Pa; represents the energy source term, W/m3; is the mass fraction of species ; is the diffusion coefficient for species , m2/s; is the reaction rate of the component, kg/(m3·s).

In this study, an improved Realizable turbulence model was applied to investigate the migration and diffusion processes of VOCs within high-ceiling spaces [31]. Its governing equations include the following:

Turbulent kinetic energy () equation:

Dissipation rate () equation:

where is the turbulent kinetic energy, m2/s2; is the turbulent viscosity, Pa·s; is the turbulent Prandtl number for kinetic energy, set to 1; is the turbulence production term, kg/(m·s3); is the turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate, m2/s3; is the dissipation rate Prandtl number, set to 1.2; is the dynamic generation coefficient; is the strain rate scalar, s−1; is the dissipation coefficient, set to 1.9; is the molecular kinematic viscosity, m2/s.

2.4. Methods

2.4.1. Mesh Sensitivity Analysis

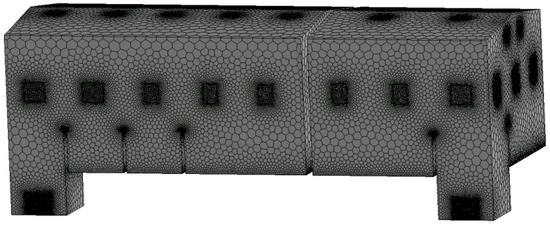

Mesh independence verification is an essential step in numerical simulations such as CFD and finite element analysis. In this study, a structured hexahedral mesh was adopted, with local refinement applied in critical areas to enhance accuracy while maintaining computational efficiency. All meshing tasks were performed within the Ansys 2022 R1 platform using the Workbench Meshing module to discretize the geometric model. The final mesh configuration is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Grid division.

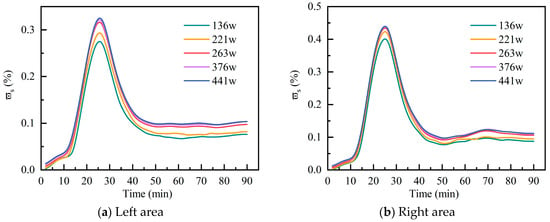

This study performed numerical simulations of C10H16O dispersion using five different grid resolutions, with total grid number of 136 w, 221 w, 263 w, 376 w, and 441 w, respectively. Figure 3 displays the variation in the surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O across the left and right areas at the 19 m elevation surface, using the 263 w grids as the baseline. The relative peak errors in the left area are 12.97%, 7.36%, 1.66%, and 2.77%, respectively, while the corresponding ones in the right area are 7.62%, 2.54%, 0.85%, and 1.27%. Thus, the grid number of 263 w was selected as the subsequent simulation scheme.

Figure 3.

Plant elevation 19 m C10H16O surface-averaged mass fraction.

2.4.2. Model Validation

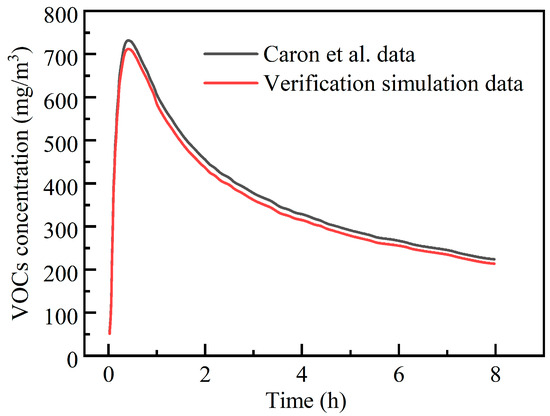

To ensure the accuracy and reliability of numerical simulation results, validating the established numerical model is a critical step. Due to the difficulty in obtaining physical models and experimental data that are fully consistent with this study, this paper selects classic cases reported in the existing literature as comparative benchmarks. Although the turbulence model and numerical solution strategy employed in this study differ from those in the references, a systematic comparison of key parameters still enables an effective assessment of the numerical method’s validity. Specifically, this study employs the Realizable turbulence model with a second-order upwind scheme for spatial discretization. In contrast, Caron et al. [19] utilized the Standard model, applying a second-order upwind scheme for the pressure term discretization while employing the QUICK scheme for other variables. The validation model was simulated according to the numerical methodology described herein. Quantitative analysis of the agreement was performed by calculating the relative error at each time point. The relative error was defined as:

where is the concentration predicted by the present model, mg/m3; is the simulated concentration from Ref. [19], mg/m3.

Figure 4 shows comparison results between the present model in this paper and the reference Caron‘s data under different diffusion times. The results demonstrate that the numerical outcomes of the proposed model are in good agreement with the experimental data. The across the evaluated time points range from 1.2% to a maximum of 5.0%, with an average of approximately 2.8%. These results demonstrate that the numerical model established in this study exhibits good accuracy and reliability and is suitable for subsequent simulation and analysis of related simulation.

Figure 4.

Model verification results [19].

2.5. Evaluation Indexes

2.5.1. Surface-Averaged Mass Fraction

The distribution of VOCs often exhibits significant non-uniformity in high-space buildings. Relying solely on instantaneous concentration values from a single measurement point cannot comprehensively and objectively reflect the overall VOCs pollution level within space. In order to characterize the overall distribution of VOCs throughout the space more scientifically, the “surface-averaged mass fraction” is introduced as an evaluation index. The calculation of surface-averaged mass fraction aims to comprehensively characterize pollutant distribution across the entire horizontal profile at specific heights (e.g., 13 m, 16 m, 19 m). The methodology is as follows: each horizontal profile is discretized into high-density grid cells, with the centroid of each cell serving as a sampling point to provide local mass fraction values. Subsequently, the surface average is computed as the area-weighted average across all grid cells within that cross-section. It can be expressed as follows:

where is the surface-averaged mass fraction; represents the area of the sampled unit, m2; is the mass fraction of the pollutant measured at the sampling unit or grid point; is the total number of sampling units.

2.5.2. Lower Explosive Limit

The Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) is a critical parameter for assessing the explosion risk of flammable gases or vapors [32]. It refers to the minimum volume fraction of the gas in air required to form a combustible mixture. The calculation formula is defined as follows:

where is the volume of the combustible gas at its lower explosive limit, m3; is the total volume of the combustible gas and air, m3.

The risk assessment was conducted using 5% of the LEL as the safety threshold. The percentage of volume fraction exceeding the 5% LEL area () is the ratio of the volume where the pollutant concentration exceeds the 5% LEL to the total volume. The calculation formula is as follows:

where is the volume exceeding the 5% LEL area, m3.

In order to standardize subsequent measurements, the LEL value in the following text shall uniformly refer to the LEL (volume fraction 0.6%) of C10H16O [33].

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Effect of Time on VOCs Migration

VOCs diffusion behavior depends on the observed time. The numerical simulation was performed under the following condition: ventilation rate of 8 air changes per hour (ACH), ambient temperature () of 300 K, air relative humidity () of 10%, wood chip stacking height () of 5 m, and C10H16O release rate of 0.068 g/(kg·h).

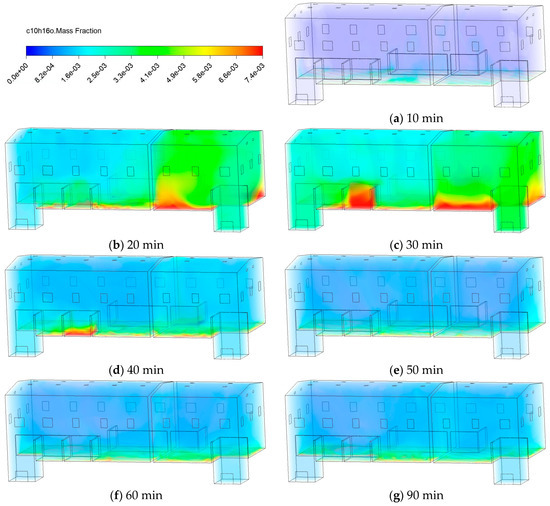

Figure 5 shows the evolution of the mass fraction () of C10H16O as a function of time. During the first 10 min, as pollutant emissions begin, only localized initial enrichment areas formed near the upper surface of the wood chips, with no significant global diffusion yet observed, as initial dispersion was dominated by molecular diffusion before large-scale convective flows were fully established. From 20 to 30 min, pollutants underwent rapid upward migration and space-wide diffusion, primarily driven by the combined effects of thermal buoyancy and the organized mechanical ventilation flow. At 40~50 min, the system exhibits distinct dynamic characteristics, with pollutant accumulation beneath both areas noticeably decreasing. After 60 min, the system gradually approaches a quasi-steady state, signifying that a balance was achieved between the constant emission rate from the source and the removal rate by the ventilation system.

Figure 5.

Contours of C10H16O mass fraction.

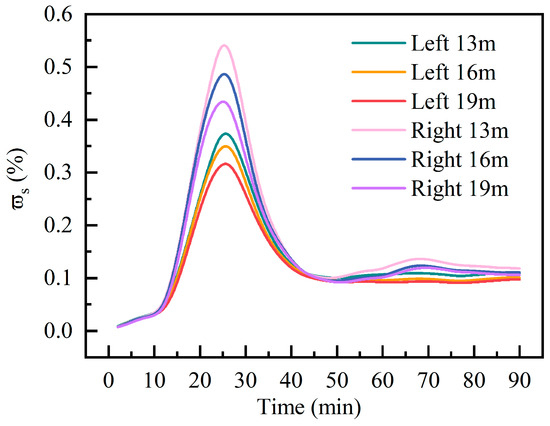

Figure 6 presents the distribution characteristics of pollutants at different heights. It illustrates the temporal variations in the surface-averaged C10H16O mass fraction () at the 13 m, 16 m, and 19 m levels within both the left and right areas. Concentration time series for all monitoring planes were analyzed, and peak occurrence times for each plane were precisely determined using cubic spline interpolation. Peak times across all monitoring planes clustered within a narrow range of 25.2 min (right side 19 m) to 26.8 min (right side 13 m), with a maximum time difference of only 1.6 min. This result confirms the high spatial synchrony of pollutant peaks across different locations. The right area exhibits its highest of 0.55% at 13 m, decreasing to 0.49% at 16 m and 0.44% at 19 m. Corresponding heights on the left-area show values of 0.38%, 0.36%, and 0.32%, respectively, indicating pronounced vertical concentration gradients in both areas. With time, the of C10H16O gradually decreased and eventually stabilized at 0.09~0.12%. The reasons for this trend are as follows: firstly, the directional flow created by pressure imports and exports promotes the initial transport of pollutants. Secondly, the baffle forms a local stagnation area near the release source below, affecting the accumulation and decay rates of C10H16O at different heights. This phenomenon is consistent with the volatile organic compound release dynamics observed by Caron et al. [19] in small ventilated compartments.

Figure 6.

Surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O.

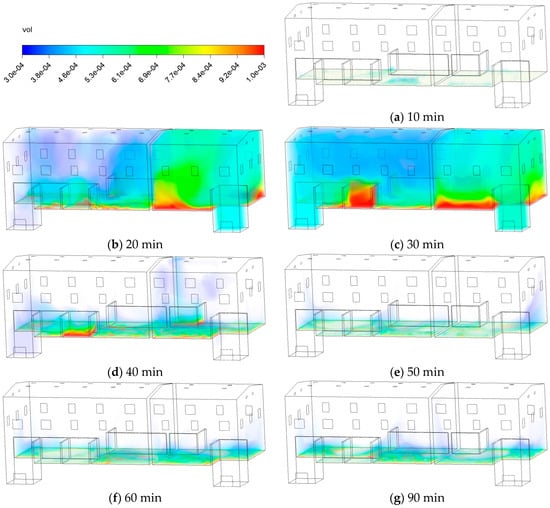

Figure 7 shows the temporal evolution of the C10H16O volume fraction distribution within the simulated space. The visualization methodology in this figure utilizes a minimum threshold corresponding to the 5% LEL of C10H16O, below which pollutant volume fractions are omitted. During 10~30 min, pollutants accumulate significantly in the lower section and gradually disperse across both areas to a broader area, as the established ventilation flow actively transported vapors from the source, filling the space faster than they could be exhausted, which caused most areas to exceed 5% LEL. At the 40~50 min, only a small portion of the area exceeds 5% LEL, indicating that the continuous ventilation began to effectively dilute the overall concentration, overcoming the initial pollutant loading rate. However, a high-concentration stagnation zone persisted above the source in the smaller partitioned space, which is attributed to the formation of a local recirculation zone or weak airflow due to the specific geometry, shielding it from the main ventilation stream. Within 60 to 90 min, pollutants are effectively diluted in most areas, with only marginal areas retaining levels near the 5% LEL.

Figure 7.

Contours of C10H16O volume fraction.

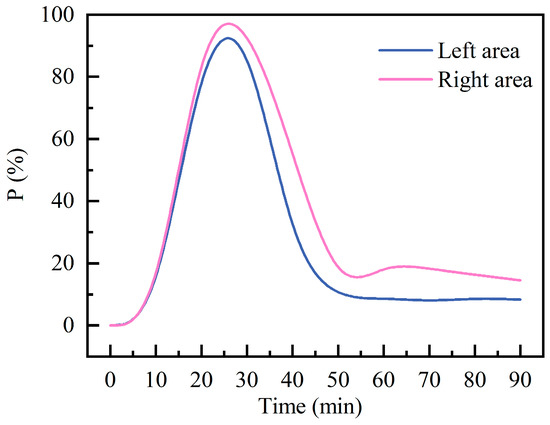

Figure 8 shows the temporal variation in the percentage of volume fraction exceeding the 5% LEL area (). The results indicate that during the initial release phase, the rapidly increased in both left and right areas, with essentially identical growth rates. Concentration peaks are reached within the 24~26 min interval for both areas. The peak proportion of exceedances in the right area reached 99.83%, slightly higher than the 99.28% recorded in the left area. Following the peak period of concentration, continuous ventilation leads to a gradual decrease in levels across both areas. At steady state, the in the right area remains 6.15% higher than in the left area. This indicates that the right zone is more prone to localized accumulation of high-concentration pollutants due to specific airflow organization characteristics and spatial structural influences.

Figure 8.

Percentage of area exceeding 5% LEL.

The pattern of VOCs’ concentrations peaking between 25 and 27 min has been clearly identified. This provides critical evidence for implementing dynamic or programmed control of ventilation systems. Within the first 30 min after material feeding, enhance local ventilation or increase air exchange rates to rapidly reduce peak VOC concentrations and prevent explosion risks.

3.2. Effect of Ambient Temperature on VOCs Migration

Ambient temperature () is a critical factor influencing the migration process of VOCs. The numerical simulation is performed under the following conditions: ventilation rate of 8 ACH, air of 10%, of 5 m, and C10H16O release rate of 0.068 g/(kg·h).

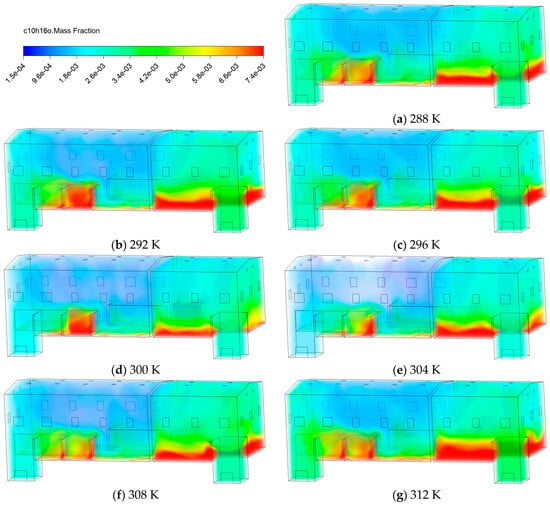

Figure 9 shows the contours of C10H16O at 30 min for of 288 K, 292 K, 296 K, 300 K, 304 K, 308 K, and 312 K. At lower (288~296 K), gas molecules have lower kinetic energy and restricted diffusion capabilities, making it difficult for C10H16O to rise to higher spaces and preventing effective dilution by airflow. When the rises to 300 K, the accumulation zone beneath the pollutants significantly diminishes, mainly due to enhanced upward diffusion and the ventilation-driven dilution effect. At of 304 K and above, the high concentration region of C10H16O significantly expands. This is primarily due to the following two factors caused by rising : (1) increasing thermal buoyancy, which enhances the upward dispersion of pollutants accumulated below; (2) reducing viscosity coupled with enhancing turbulence, which promotes mixing and dilution, ultimately resulting in an overall reduction in .

Figure 9.

Contours of C10H16O mass fraction at different temperatures.

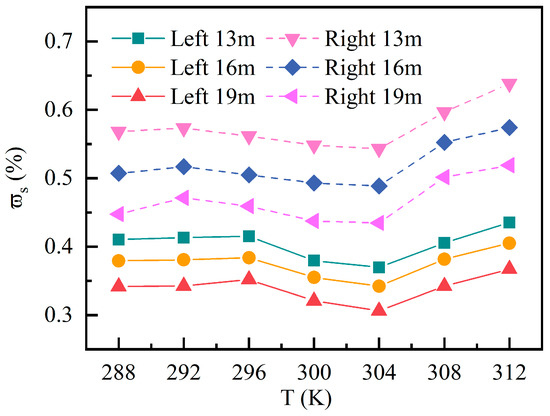

Across all (288~312 K) and heights (13 m, 16 m, 19 m), the peak times varied only within a narrow range of 25~27 min, indicating that temperature mainly affects the magnitude of the peak rather than the timing. Figure 10 displays the peak within 90-minute period across various temperatures. Both regions exhibit a stable spatial gradient as follows: 13 m > 16 m > 19 m, with the left area showing lower peaks. The low range (288~296 K): diffusion and turbulent mixing are relatively weak, and induced peak variations are mild. Within the middle range (300~304 K): enhanced mixing and dilution yield the lowest peaks. The peak minimum values in the left area at the 13 m, 16 m, and 19 m levels are 0.37%, 0.34%, and 0.31%, respectively, while those in the right area are 0.54%, 0.49%, and 0.43%, respectively. In the high range (308~312 K), despite stronger turbulence, pollutants rise rapidly due to thermal buoyancy. Peaks rebound and reach the highest levels at 312 K, increasing by 0.01~0.09% compared to 304 K. The nonlinear temperature dependence observed in this study aligns with previous findings in indoor air quality research [11,24].

Figure 10.

Peak surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O at different temperatures.

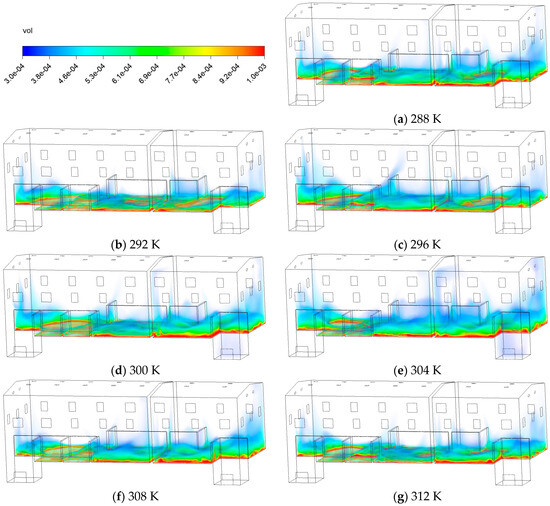

In Section 3.1, the system reaches a quasi-steady state after 60 min. Volume fraction contours at the 60 min mark are selected to compare the attainment of 5% LEL levels at different . Figure 11 presents the volume fraction contours at different after 60 min. Between 288~296 K, the thickness of the colored band decreases slightly, indicating that the influx dilution and turbulent mixing in this range can largely offset the enhanced thermal buoyancy. As the rises to 300~304 K, the near-source layer thickens significantly and shifts upward. At 308 K and above, the thickness of this layer decreases due to stronger thermal buoyancy and intensified turbulent mixing.

Figure 11.

Contours of volume fraction of C10H16O at different temperatures.

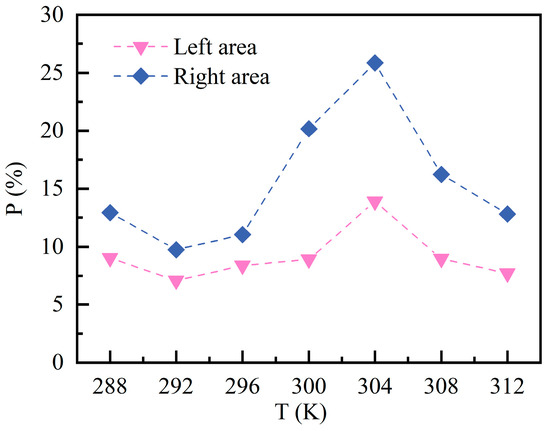

Figure 12 shows the of C10H16O at different over a 60 min period. The risk level in the right area is consistently higher than that in the left area across the entire range. Particularly at 304 K, the right area reaches a maximum of approximately 25.87%, whereas the left area accounts for only 13.90% at the same . This indicates that the reduction in concentration comes at the cost of an expanded area of contamination. The overall trend shows a pattern of initial decrease, subsequent increase, and eventual decrease. At above 304 K, the area exceeding standards actually decreases. This is due to the combined effects of thermal buoyancy and increased turbulence, which reduce the concentration of pollutants in the lower regions.

Figure 12.

Percentage of areas exceeding 5% LEL at different temperatures.

The nonlinear effect of on VOC migration reveals the complexity of ventilation system design. Research indicates that between 300~304 K, despite the lowest peak concentrations, the area exceeding permissible limits is the largest, representing a potential “hidden high-risk” condition. Within this range, ventilation systems must operate at full capacity to dilute widely dispersed combustible gases. At elevated temperatures (>308 K), enhanced thermal buoyancy reduces the efficiency of conventional mixed ventilation. Consequently, we recommend considering displacement ventilation or stratified air conditioning systems in high-temperature regions or during summer months to more effectively disperse pollutants and disrupt thermal stratification.

3.3. Effect of Fresh Air Humidity on VOCs Migration

The effect of fresh air humidity () on pollutant migration processes is investigated under the following conditions: ventilation rate of 8 ACH, indoor of 10%, of 5 m, of 300 K, and C10H16O release rate of 0.068 g/(kg·h).

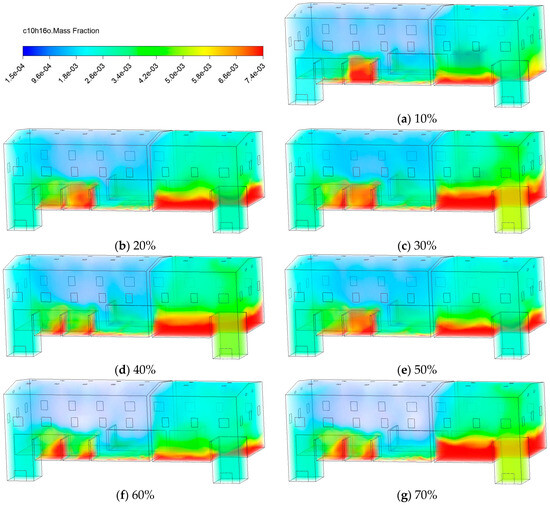

Figure 13 displays the contours of C10H16O at 30 min under different conditions, ranging from 10% to 70%. At lower levels (10~30%), high-concentration zones extensively expand along the lower edge of the partition and the lower space. As rises to 40~60%, the area of high concentration zones gradually shrinks, and pollutant distribution becomes more uniform vertically. This indicates that moderately humidified fresh air enhances airflow mixing and convective dilution, thereby helping to reduce pollutant accumulation. However, when reaches 70%, localized concentration increases occur near the emission sources. This indicates that in high environments, the coupling of local airflow disturbances with building structures may reduce ventilation efficiency and promote pollutant accumulation in lower zones.

Figure 13.

Contours of the mass fraction of C10H16O at different fresh air humidity.

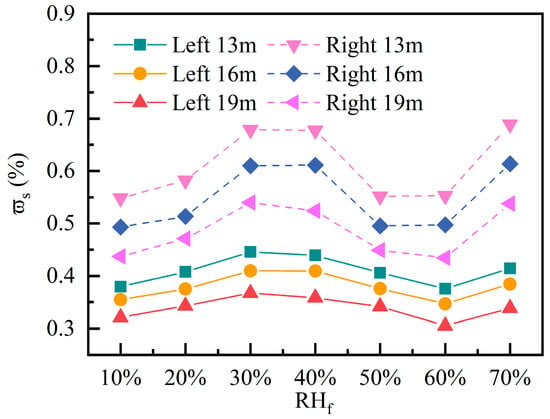

Figure 14 shows the peak variation patterns of the of C10H16O in the left and right areas at heights of 13 m, 16 m, and 19 m within a 90 min period under different . In the low range (10~30%), the peak concentrations continue to rise. For every 10% increase in , the left area shows a mass fraction increase of 0.08%, while the right area shows a mass fraction increase of 0.17%. When reaches 40% to 60%, the peak shows a decreasing trend. Compared to conditions at 30% , the left and right areas each exhibit a decrease of approximately 0.06% and 0.11%, respectively, across each surface. At 70% , concentrations rose again, suggesting that excessively high humidity may reduce ventilation drive, leading to decreased air exchange efficiency. However, Lüpke et al. [12] previously found that drought suppresses plant VOC emissions, which appears to contradict our simulation showing “low humidity leads to high concentrations”. The key distinction lies in their focus on biogenic emission processes, whereas our model assumes constant source strengths and emphasizes the physical diffusion of pollutants in space.

Figure 14.

Peak surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O at different fresh air humidity.

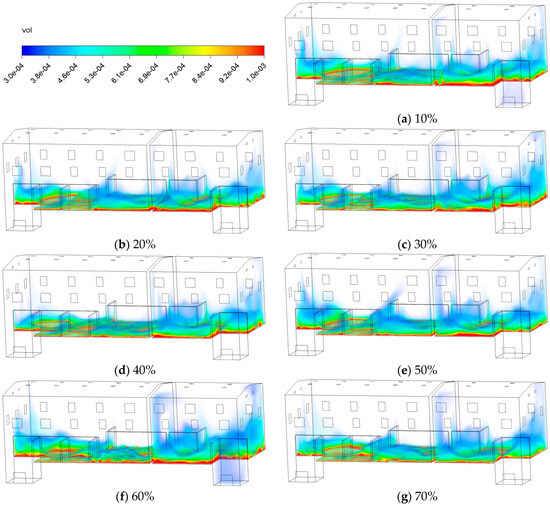

As shown in Figure 15, the volume fraction distribution of C10H16O at 60 min under different conditions are analyzed. At lower levels (10~40%), the high-concentration pollution zones near the emission sources visibly thinned, indicating a certain dilution effect. This can be attributed to the enhanced air buoyancy and turbulent mixing in drier air, which promotes the dilution and dispersion of VOC vapors. When increases to 50~60%, localized volume fraction increases occur near walls and partitions, and the area not failing to meet 5% LEL requirements expands. As continues to rise, localized high-concentration zones gradually diminish, and the overall volume fraction decreases significantly. At high humidity (70%), the competition from water vapor molecules and altered dispersion dynamics promote overall dilution, reducing both local and overall concentrations. In summary, appropriately increasing ambient humidity can reduce the equilibrium concentration of C10H16O, thereby lowering the risk of combustion.

Figure 15.

Contours of the volume fraction of C10H16O at different fresh air humidity.

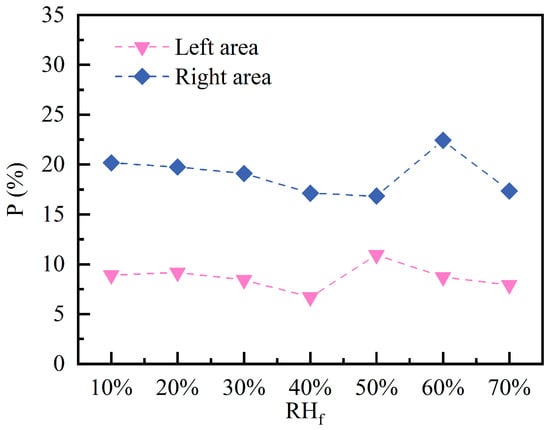

Figure 16 indicates the of C10H16O at 60 min under different conditions. The in the left area remains relatively low, ranging from 6.72% to 10.95%. The minimum value occurs at 40% , while the maximum corresponds to 50% , exhibiting a similar “trough-to-peak” trend. The same trend is observed in the right area, with a maximum value of 22.45% occurring at 60% and a minimum value of 16.86% occurring at 50% . This pattern indicates that under moderately conditions, pollutants can be partially adsorbed and diffusion enhanced, thereby suppressing the formation of hazardous zones. Conversely, in high environments, the coupled effects of airflow turbulence and volatilization behavior may actually intensify the tendency for localized pollutant accumulation.

Figure 16.

Percentage of areas exceeding 5% LEL at different fresh air humidity.

Optimizing humidity control offers a low-cost, high-benefit approach to enhancing ventilation efficiency. This study demonstrates that pre-conditioning incoming to a moderate range of 40–60% within warehouses effectively promotes airflow mixing and reduces peak concentrations. Therefore, installing humidification or dehumidification equipment in ventilation systems holds significant engineering value in both arid and humid climates. This approach prevents rapid dispersion under low- conditions and localized accumulation under high- conditions, enabling the ventilation system to operate stably and efficiently under any humidity environment. Consequently, it establishes a reliable climate-adaptive safety barrier.

3.4. Effect of Wood Chip Stacking Height on VOCs Migration

The wood chip stacking height () determines the internal air volume and the amount of pollutant volatilization. At ventilation rate of 8 ACH, an of 10%, a release rate of C10H16O of 0.068 g/(kg·h), and a of 300 K, simulations are conducted for various .

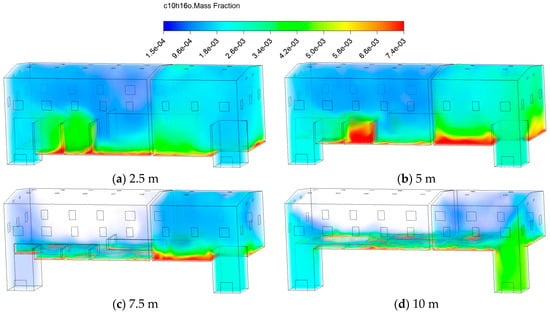

Figure 17 shows the distribution of C10H16O after 30 min of release at different (2.5 m, 5 m, 7.5 m, 10 m). At an of 2.5 m, vertical dispersion of pollutants is restricted, mainly accumulating in lower areas and exhibiting a pronounced accumulation effect. As the increases to 5 m, the upward dispersion range of pollutants expands, but the lower space remains the primary area affected. At of 7.5 m and 10 m, airflow becomes more vigorous, allowing pollutants to disperse further into the upper regions. The overall decreases significantly, indicating enhanced pollutant dilution capacity and a marked reduction in pollution accumulation.

Figure 17.

Contours of C10H16O mass fraction at different wood chip stacking height.

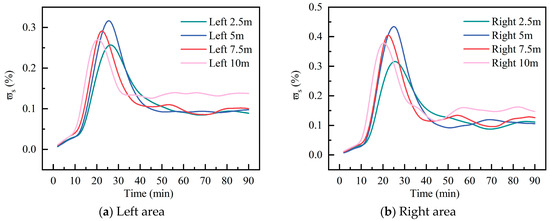

Figure 18 shows the temporal variation in the of C10H16O at the 19 m surface under different . At both 2.5 m and 5 m , the in both areas peak around 26 min, reaching 0.32% and 0.44%, respectively, increases of 0.06% and 0.12% compared to the 2.5 m condition. Increasing the advanced the peak occurrence time. At of 2.5 m and 5 m, peaks occurred at 26.2 and 26.4 min, respectively. When the was increased to 7.5 m and 10 m, the peaks advanced to 22.3 min and 20.4 min, respectively. Moreover, the maximum at 10 m decreased significantly to 0.21% and 0.28%. This indicates that under identical ventilation rates, a with a smaller enclosed space facilitates faster diffusion and dilution of indoor pollutants, resulting in lower peak concentrations. However, at a of 10 m, the of pollutants in the final stabilization phase is higher than at other . This is because the higher results in more significant pollutant emissions, and the smaller space leads to higher concentrations per unit volume. Increased leads to higher total emissions and reduced effective ventilation space, consistent with Krigstin et al.’s [27] observation that larger wood chip piles pose heightened risks of self-heating and gas release.

Figure 18.

Surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O at different wood chip stacking height.

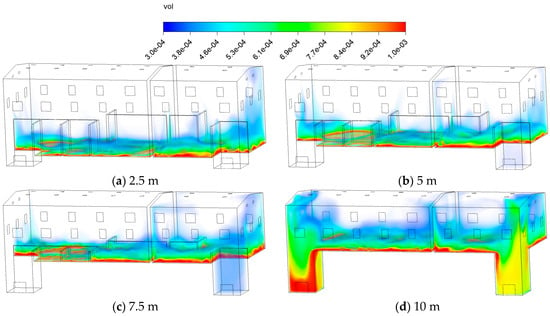

Figure 19 shows the volume fraction distribution of C10H16O at 60 min under different . The left area exhibits reduced concentrations near the wall at ranging from 2.5 to 7.5 m, with the right area showing the same trend between 2.5 and 5 m. However, as the on both sides continues to increase, the high-concentration zones exhibit continuous distribution patterns, and the upward transport capacity of pollutants is weakened. Concurrently, the larger accumulation volume of wood chips leads to a higher pollutant release rate, resulting in reduced overall dilution efficiency. At a 10 m condition, the guiding effect of the partition on airflow weakens, causing some pollutants with higher densities to settle toward the doorway area and form distinct stagnation zones in the bottom corners.

Figure 19.

Contours of the volume fraction of C10H16O at different wood chip stacking height.

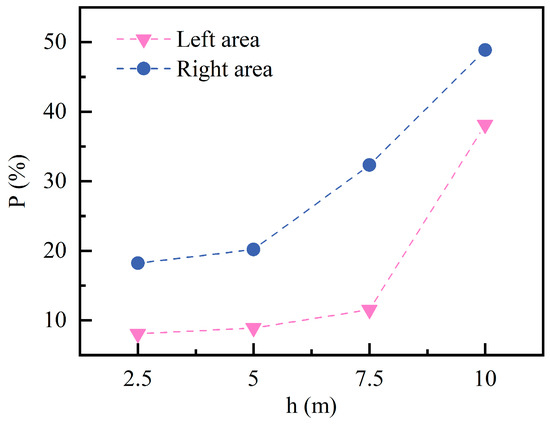

Figure 20 illustrates the trend in the after 60 min of C10H16O release at different . From the right area, the exhibits an approximately linear increase, rising steadily from 18.22% to 48.87%. This is attributed to increased pollutant volatilization under conditions, coupled with a significant reduction in effective ventilation space. In contrast, the response trend in the left area is relatively flat. When the increases from 2.5 m to 7.5 m, the increases are only marginal, from 8.06% to 11.52%. However, as the is further raised to 10 m, the value rises sharply to 38.13%, demonstrating a pronounced stepwise growth pattern. This transition is primarily caused by the restricted vertical diffusion pathways of pollutants and the weakened airflow organization in upper areas.

Figure 20.

Percentage of areas exceeding 5% LEL at different wood chip stacking height.

This quantitative analysis reveals that the risk of VOC explosions significantly increases when exceeds 7.5 m, with high-risk zones accounting for 48.87% at 10 m. Therefore, it is recommended to establish a dynamic intelligent ventilation system with a “safe volume threshold” based on CFD simulations. Should exceed the threshold, causing the effective volume to fall below the threshold, the system automatically switches to enhanced ventilation mode—such as increasing air exchange rates or activating localized exhaust. By integrating sensors with automated control systems, this approach achieves closed-loop management transitioning from static design to dynamic response, ensuring precise safety in large-scale spaces.

3.5. Effect of VOCs Types on VOCs Migration

Different types of VOCs significantly influence the migration process of pollutants within a space due to their varying physicochemical properties. The simulation is carried out for five VOCs (C10H16, C10H16O, C10H18O, C10H10O2, and C15H26O) under the following conditions: air change rate of 8 ACH, air of 10%, of 5 m, volatilization rate of 0.068 g/(kg·h), and of 300 K.

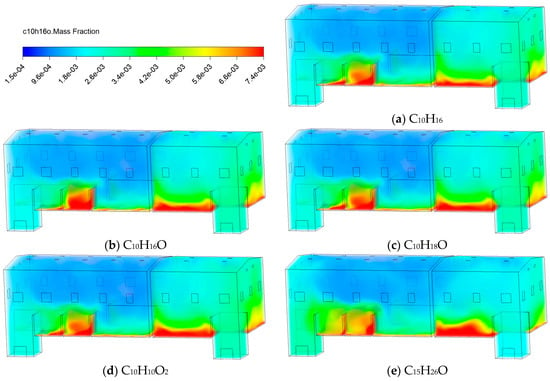

Figure 21 exhibits the distribution of various VOCs after 30 minutes of release. The substances C10H16, C10H16O, and C10H18O, characterized by relatively low molecular weights and weak polarity, exhibit stronger diffusion capabilities. They distribute more widely in space, readily diffuse upward with air currents into upper regions, and tend to form high-concentration accumulation zones in structurally complex areas. Meanwhile, the species with more oxygen-containing functional groups or larger molecular volumes, such as C10H10O2 and C15H26O, exhibit higher stability in the gaseous state. They tend to accumulate near the source area, resulting in a more centralized distribution and significantly reduced migration capacity of bottom pollutants.

Figure 21.

Contours of C10H16O mass fraction at different types of VOCs.

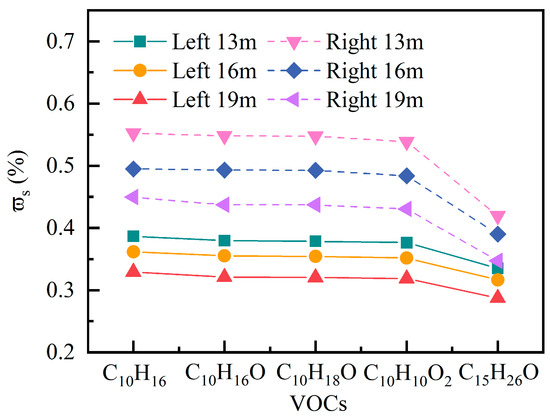

Figure 22 exhibits the peak of various VOCs recorded at three representative locations (13 m, 16 m, 19 m) within 90 min. The effect of pollutant type on peak concentrations shows that the maximum gradually decreases with increasing molecular weight and polarity of VOCs. In the right area at 13 m, the of C10H16 is 0.39%, while that of the more polar and higher molecular weight compound C15H26O decreases to 0.34%. The same trend is observed in the left area: C10H16 at 0.55%, while C15H26O is only 0.42%. These results indicate that low-molecular-weight, low-polarity VOCs possess stronger volatilization and gas-phase diffusion capabilities, making them more prone to form high accumulations in areas with complex spatial structures and relatively restricted ventilation. VOCs with different polarities and molecular weights exhibit distinctly different diffusion behaviors, which fully align with the VOC specificity emphasized in the meta-analysis by Bao et al. [9].

Figure 22.

Peak surface-averaged mass fraction of C10H16O at different types of VOCs.

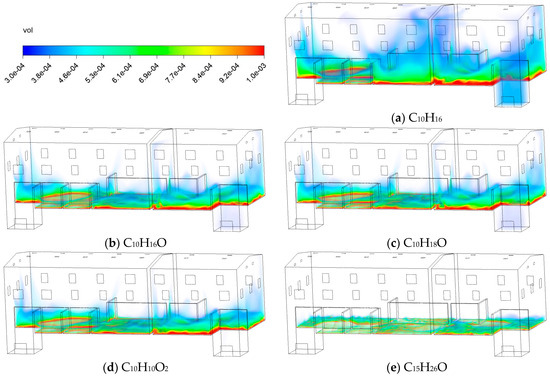

Figure 23 shows the volume fraction contours of five typical VOCs at 60 min. As the molecular weight of VOCs increases and polarity intensifies, the spatial range extent of the tinted area exhibits a gradual contraction. In the case of C10H16, its tinted area shows the widest distribution, indicating that such low-polarity, low-molecular-weight substances are more prone to rapid volatilization and accumulation in confined spaces. However, at the same ventilation and volatilization conditions, the tinted area for C15H26O is significantly smaller, forming only a localized and mildly exceeded area near the source term, far below that of other types of VOCs. This result indicates that high-molecular-weight alcohols or alkanes exhibit slower diffusion rates in indoor air and are more susceptible to structural obstructions.

Figure 23.

Contours of the volume fraction of C10H16O at different types of VOCs.

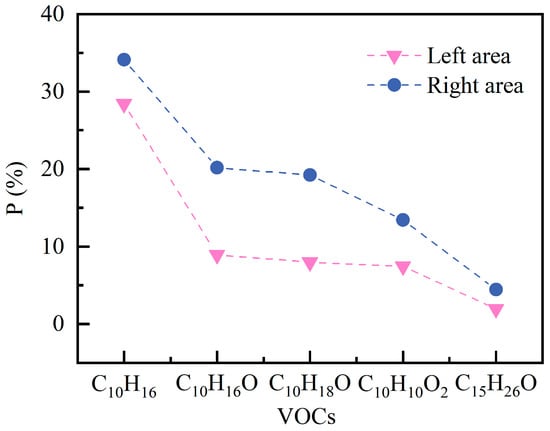

Figure 24 illustrates the spatial coverage changes in five representative VOCs with after 60 min of release. The extent of the decreases significantly with increasing molecular weight and polarity of the VOCs. In the case of C10H16, the in the left and right zones are 28.41% and 34.10%, respectively, and are substantially higher than those of the other VOCs. Its high volatility and rapid diffusion allow it to form a widespread flammable atmosphere. Meanwhile, as a high-molecular-weight oxygen-containing compound, C15H26O accounts for only 1.98% and 4.48% in the two regions, respectively, representing a reduction of more than 86% compared to C10H16. This reflects its inherently lower vapor pressure and slower diffusion rate, which confine it to accumulation zones near the emission source under the current ventilation conditions.

Figure 24.

Percentage of areas exceeding 5% LEL at different types of VOCs.

Based on the differing migration characteristics of VOCs, customized ventilation strategies are recommended for various wood species. For storing coniferous woods like pine (which primarily release small-molecule VOCs such as C10H16), high-intensity comprehensive ventilation is advisable to achieve spatial dilution. For storing certain hardwoods (which primarily release large-molecule VOCs like C15H26O), a combined approach of “basic comprehensive ventilation and local exhaust ventilation” is recommended. This involves installing exhaust hoods above stacks for source control, ensuring safety while effectively reducing system energy consumption.

4. Conclusions

This study investigates the migration behavior of typical VOCs in semi-enclosed high-space wood chip fuel storage shed spaces. A CFD mode of a semi-enclosed high-space wood chip fuel storage shed was built and proposed. Then, the effects of various parameters including temporal evolution, ambient temperature (), fresh air humidity (), wood chip stacking height (), and VOC types, on migration and diffusion characteristics of VOCs were investigated and evaluated in-depth. A typical emission scenario is constructed using C10H16O as a model pollutant. The surface-averaged mass fraction () and the proportion of areas exceeding the 5% LEL () as evaluation indexes are used.

(1) In terms of temporal evolution, C10H16O initially accumulated near the bottom of the source area. As ventilation and convection are established, it gradually disperses throughout the space, reaching a quasi-steady state after 60 min. The concentrations at different heights (13 m, 16 m, 19 m) all show an initial increase followed by a decrease, with peaks occurring between 25 and 27 min. The peak at the right side are 0.55%, 0.49%, and 0.44%, respectively, while those at the left side are 0.38%, 0.36%, and 0.32%.

(2) exerts a dominant and nonlinear influence on the peak of the . In the range of 300~304 K, the peak is lowest (0.31% and 0.43% at a height of 19 m in both areas, respectively), yet the corresponding steady-state area is largest. For the 19 m plane on the left, when the rises from 304 K to 312 K, its peak increases by 19.88%.

(3) For , moderate humidity conditions (40~60% ) most effectively promote airflow mixing. Within this range, peak concentrations decrease by a mass fraction of 0.06% (left area) and 0.11% (right area). Both low humidity (<30% ) and high humidity (70% ) environments are detrimental to pollutant control. The effect of on is relatively insignificant at 60 min.

(4) The increase from 7.5 m to 10 m resulted in the most significant change in the . Increasing the to 7.5 m enhances dilution, advancing the peak occurrence time from 26 to 22 min. At 19 m height, peak decrease to 0.21% (left) and 0.28% (right). However, excessively high (10 m) caused a significant increase in total emissions and reduced effective ventilation space, resulting in an increase in the in the right area from 25% at 7.5 m to 48.87%.

(5) The physicochemical properties of VOCs play a decisive role in determining their migration capacity and associated fire and explosion risks. Low-molecular-weight, weakly polar VOCs (C10H16) exhibit strong diffusion capabilities, with their accounting for as much as 34.10% (right area). In contrast, high-molecular-weight, strongly polar VOCs (C15H26O) demonstrate weak migration capabilities, resulting in a significant decrease in to 4.48%, a reduction exceeding 86%. The peak shows a noticeable decrease only for C15H26O (left area: 0.39~0.34%, right area: 0.55~0.42%).

(6) This study employed CFD simulations to reveal the migration patterns of VOCs within a semi-enclosed, tall wood chip shed. However, certain limitations exist, pointing to directions for future research. First, VOC emission sources were simplified as uniform surface sources. Subsequent work could consider the flow and mass transfer processes within the porous medium of the wood chip pile to more accurately describe actual emission behavior. Second, while this study primarily focused on mechanical ventilation, future research could explore the applicability of natural or mixed ventilation modes under varying climatic conditions, providing a basis for designing low-energy, safe ventilation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.Y. and Q.X.; methodology, X.Y.; software, X.Y.; validation, Q.X.; formal analysis, B.Y.; investigation, S.M.; resources, B.Y.; data curation, Q.X.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.X.; writing—review and editing, X.Y.; visualization, Q.X.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, S.M.; funding acquisition, B.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Central Guiding Funds for Local Science and Technology Development Projects (No. 236Z4503G), Industry-University-Research Collaboration Projects of Shijiazhuang in Hebei Province (No. 241010071A) and Colleges and University in Hebei Province Science Research Fund (No. CXZX2025025).

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because they are part of an ongoing study and contain proprietary information. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| AHC | Air changes per hour |

| BVOC | Biogenic volatile organic compounds |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| LEL | Lower explosive limit |

| PRM | Passive removal materials |

| TVOC | Total volatile organic compounds |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| Symbols | |

| The area of the sampled unit (m2) | |

| The simulated concentration in the reference materials (mg/m3) | |

| The dynamic generation coefficient | |

| The dissipation coefficient, set to 1.9 | |

| Specific heat capacity at constant pressure (J/(kg·K)) | |

| The concentration predicted by the present model (mg/m3) | |

| The diffusion coefficient for species (m2/s) | |

| The total energy per unit mass (J/kg) | |

| The gravitational acceleration (m/s2) | |

| The turbulence production term (kg/(m·s3)) | |

| Wood chip stacking height | |

| The specific enthalpy of species (J/kg) | |

| The mass diffusion flux of species (kg/(m2·s)) | |

| The turbulent kinetic energy (m2/s2) | |

| The total number of sampling units | |

| Pressure (Pa) | |

| The percentage of volume fraction exceeding the 5% LEL area | |

| The reaction rate of the component (kg/(m3·s)) | |

| Air relative humidity | |

| The strain rate scalar (s−1) | |

| The energy source term (W/m3) | |

| Time (s) | |

| Temperature (K) | |

| , , | The velocity components in the , , axes (m/s) |

| Volume (m3) | |

| The mass fraction of species | |

| Greek symbols | |

| The spatial gradient operator | |

| Thermal conductivity (W/(m·K)) | |

| The molecular kinematic viscosity (m2/s) | |

| Mass fraction | |

| The surface-averaged mass fraction | |

| The turbulent kinetic energy dissipation rate (m2/s3) | |

| Relative error | |

| The dissipation rate Prandtl number, set to 1.2 | |

| The turbulent Prandtl number for kinetic energy, set to 1 | |

| The viscous stress tensor (Pa) | |

| The velocity vector (m/s) | |

| The turbulent viscosity (Pa·s) | |

| The dynamic viscosity (Pa·s) | |

| The fluid density (kg/m3) | |

| Subscript | |

| Ambient | |

| Exceeding the 5% LEL | |

| Fresh air | |

| The sampled unit | |

| The combustible gas at its lower explosive limit |

References

- Esteban, B.; Baquero, G.; Puig, R.; Riba, J.-R.; Rius, A. Is it environmentally advantageous to use vegetable oil directly as biofuel instead of converting it to biodiesel? Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baquero, G.; Esteban, B.; Riba, J.-R.; Rius, A.; Puig, R. An evaluation of the life cycle cost of rapeseed oil as a straight vegetable oil fuel to replace petroleum diesel in agriculture. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3687–3697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittaker, C.; Mortimer, N.; Murphy, R.; Matthews, R. Energy and greenhouse gas balance of the use of forest residues for bioenergy production in the UK. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4581–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Forestry Production and Trade[EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/FO (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Siwale, W.; Frodeson, S.; Berghel, J.; Henriksson, G.; Finell, M.; Arshadi, M.; Jonsson, C. Influence on off-gassing during storage of Scots pine wood pellets produced from sawdust with different extractive contents. Biomass Bioenergy 2022, 156, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakoski, E.; Jämsén, M.; Agar, D.; Tampio, E.; Wihersaari, M. From wood pellets to wood chips, risks of degradation and emissions from the storage of woody biomass—A short review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Garcia, L.; Ashley, W.J.; Bregg, S.; Walier, D.; LeBouf, R.; Hopke, P.K.; Rossner, A. VOCs Emissions from Multiple Wood Pellet Types and Concentrations in Indoor Air. Energy Fuels Am. Chem. Soc. J. 2015, 29, 6485–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Stratopoulos, L.M.F.; Moser-Reischl, A.; Zölch, T.; Häberle, K.H.; Rötzer, T.; Pretzsch, H.; Pauleit, S. Traits of trees for cooling urban heat islands: A meta-analysis. Build. Environ. 2020, 170, 6485–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Zhou, W.; Xu, L.; Zheng, Z. A meta-analysis on plant volatile organic compound emissions of different plant species and responses to environmental stress. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lun, X.; Lin, Y.; Chai, F.; Fan, C.; Li, H.; Liu, J. Reviews of emission of biogenic volatile organic compounds (BVOCs) in Asia. J. Environ. Sci. 2020, 95, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, F.; Chen, Y.; Yang, S.; Dai, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhang, N.; Shu, Z.; Yan, H.; Ge, X.; et al. Impact of temperature on the biogenic volatile organic compound (BVOC) emissions in China: A review. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 159, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüpke, M.; Leuchner, M.; Steinbrecher, R.; Menzel, A. Impact of summer drought on isoprenoid emissions and carbon sink of three Scots pine provenances. Tree Physiol. 2016, 36, 1382–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, T.-B.; Sheu, J.-J.; Huang, J.-W.; Lin, Y.-S.; Chang, C.-C. Development of a CFD model for simulating vehicle cabin indoor air quality. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2018, 62, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, F.; Guichard, R.; Robert, L.; Verriele, M.; Thevenet, F. Behaviour of individual VOCs in indoor environments: How ventilation affects emission from materials. Atmos. Environ. 2020, 243, 117713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hormigos-Jimenez, S.; Padilla-Marcos, M.Á.; Meiss, A.; Gonzalez-Lezcano, R.A.; Feijó-Muñoz, J. Ventilation rate determination method for residential buildings according to TVOC emissions from building materials. Build. Environ. 2017, 123, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domhagen, F.; Langer, S.; Sasic Kalagasidis, A. Modelling VOC levels in a new office building using passive sampling, humidity, temperature, and ventilation measurements. Build. Environ. 2023, 238, 110337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, S.; Yesildagli, B.; Kwon, J.-H.; Lee, J. Comparative analysis of indoor volatile organic compound levels in an office: Impact of occupancy and centrally controlled ventilation. Atmos. Environ. 2025, 345, 121057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinke, R.; Wothe, K.; Dugarev, D.; Götze, O.; Köhler, F.; Schalau, S.; Krause, U. Uncertainty consideration in CFD-models via response surface modeling: Application on realistic dense and light gas dispersion simulations. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 75, 104710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, F.; Guichard, R.; Robert, L.; Verriele, M.; Thevenet, F. Experimental assessment of modelling VOC emissions from particleboard into a ventilated chamber. Atmos. Environ. 2024, 320, 120341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A.; Gao, Y.; Rao, Y.; Zhao, Q. Study on the kinetic characteristics of indoor air pollutants removal by ventilation. Build. Environ. 2022, 207, 108535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egedy, A.; Gyurik, L.; Ulbert, Z.; Rado, A. CFD modeling and environmental assessment of a VOC removal silo. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malayeri, M.; Bahri, M.; Haghighat, F.; Shah, A. Impact of air distribution on indoor formaldehyde abatement with/without passive removal material: A CFD modeling. Build. Environ. 2022, 212, 108792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Kim, J.; Ga, S.; Lim, J.; Kim, J.; Cho, H. Computational fluid dynamics-based optimal installation strategy of air purification system to minimize NOX exposure inside a public bus stop. Environ. Int. 2022, 169, 107507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teodosiu, C.; Ilie, V.; Teodosiu, R. Modelling of volatile organic compounds concentrations in rooms due to electronic devices. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2017, 108, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandan, A.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Kumar, P. Estimation of indoor air pollutant during photocopy/printing operation: A computational fluid dynamics (CFD)-based study. Environ. Geochem. Health 2020, 42, 3543–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, D.; Huang, Y.; Wu, G.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hao, G.; Hou, H. Modeling the volatile organic compounds emissions from asphalt pavement construction and assessing health risks for workers with uncertainty analysis. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigstin, S.; Helmeste, C.; Wetzel, S.; Volpé, S. Managing self-heating & quality changes in forest residue wood waste piles. Biomass Bioenergy 2020, 141, 105659. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Huang, L.; Hu, H.; Li, J.; Chen, L. Investigating the emission of volatile organic compound from Cinnamomum camphora. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 219, 119134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, U.-H.; Lee, I.-B.; Kim, R.-W.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-G. Computational fluid dynamics evaluation of pig house ventilation systems for improving the internal rearing environment. Biosyst. Eng. 2019, 186, 259–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Xu, C.; Bi, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xu, X. Numerical simulation study on VOCs diffusion characteristics and influencing factors in oily sewage pools based on CFD. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2025, 203, 107859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Meng, Q.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q. The Turbulent Schmidt Number for Transient Contaminant Dispersion in a Large Ventilated Room Using a Realizable k-ε Model. Fluid Dyn. Mater. Process. 2024, 20, 829–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jiangalan, H.; Zhang, D.; Zhao, B. Evaluation on effects of air inflow on indoor environment in an air-supported membrane coal-shed building. Energy Build. 2025, 329, 115244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merck KGaA D, Germany and/or Its Affiliates. Merck[EB/OL]. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.cn/CN/en (accessed on 11 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).