Exploring the Link Between Vaginal Delivery and Postpartum Dyspareunia: An Observational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Standards of Labor Management

2.3. Study Population

- Primiparae at ≥37 + 0 weeks of pregnancy, cephalic presentation, and singleton pregnancy, regardless of comorbidities as psychiatric conditions or pre-existing chronic pain, or postpartum anxiety- or depression-disorder;

- Spontaneous vaginal delivery or vacuum-assisted delivery;

- Manual perineal protection (“hands-on”);

- Restrictive, indicated episiotomy.

- Preterm birth before 37 + 0 weeks of gestation;

- Multiparous women;

- Breech presentation;

- Cesarean section;

- Forceps delivery.

- Maternal age.

- Fetal birth weight.

- Duration of delivery:

- ○

- Duration of first stage of labor;

- ○

- Duration of second stage of labor;

- ○

- Duration of first and second stages of labor.

- Birthing method:

- ○

- Bed delivery (reference);

- ○

- Water delivery;

- ○

- Other vaginal delivery;

- ○

- Vacuum-assisted delivery.

- Perineal injury:

- ○

- Intact perineum (reference);

- ○

- First- and second-degree perineal tear;

- ○

- OASI (third- and fourth-degree perineal tear);

- ○

- Episiotomy.

- Use of oxytocin:

- ○

- No oxytocin (reference);

- ○

- During first stage of labor;

- ○

- During second stage of labor;

- ○

- During first and second stages of labor.

2.4. Outcome Measures

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Population

3.2. Outcome

4. Discussion

4.1. No Influence of Birthing Method

4.2. Perineal Injuries Have an Influence on Postpartum Dyspareunia

- In this hospital setting, mediolateral episiotomies were applied restrictively and only under selected indications, like fetal distress, risk for OASI, or very tight perineum.

- Although unintentional, OASIs might be under-diagnosed as a second-degree tear.

- Some data indicate improved psychophysical health 12 months postpartum among women who underwent episiotomies [19,46]. Other data show similar outcomes for postpartum dyspareunia and sexual function when comparing episiotomies and first- and second-degree perineal tears [19]. Women with episiotomies often resumed sexual activity later than others [42].

4.3. Oxytocin and Its Unknown Influence

4.4. Limitation and Future Directions

- The analysis was retrospective.

- The questionnaire used was not validated, as no questionnaire was available.

- Postpartum dyspareunia was not subclassified into deep and superficial forms.

- There was a lack of detailed information on contributing factors such as pre-existing dyspareunia, breastfeeding, hormonal status, BMI, and psychological well-being.

5. Conclusions

- Prospective trials that include the full range of potential influencing factors (e.g., pre-existing dyspareunia and psychiatric disorders, BMI, perinatal factors, and postnatal factors such as breastfeeding) are essential.

- Validated questionnaires, such as the female sexual function index, should be employed.

- Comparable standards of obstetric care, including the use of the OASI care bundle, are recommended and may facilitate comparison across studies.

- The impact of the OASI care bundle on the development of postpartum dyspareunia requires further investigation.

- The effectiveness of different prevention strategies and management approaches also warrants evaluation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BD | Bed delivery |

| CI | Confidence interval |

| N / n | number |

| OD | Other vaginal delivery |

| OASIs | Obstetric anal sphincter injuries |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| rcs | Restricted cubic splines |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| VAD | Vacuum-assisted delivery |

| WD | Water delivery |

References

- Rogers, R.G.; Pauls, R.N.; Thakar, R.; Morin, M.; Kuhn, A.; Petri, E.; Fatton, B.; Whitmore, K.; Kinsberg, S.; Lee, J. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) Joint Report on the Terminology for the Assessment of Sexual Health of Women with Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2018, 37, 1220–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latthe, P.; Latthe, M.; Say, L.; Gülmezoglu, M.; Khan, K.S. WHO Systematic Review of Prevalence of Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Neglected Reproductive Health Morbidity. BMC Public Health 2006, 6, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.A.; Taylor, C.A. Dyspareunia in Women. Am. Fam. Physician 2021, 103, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Meana, M.; Binik, Y.M. The Biopsychosocial Puzzle of Painful Sex. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2022, 18, 471–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Vase, L.; Hooten, W.M. Chronic Pain: An Update on Burden, Best Practices, and New Advances. Lancet 2021, 397, 2082–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntzinger, J.; Selassie, M. Interventional Pain Management in the Treatment of Chronic Pelvic Pain. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2023, 24, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaei, M.; Kariman, N.; Ozgoli, G.; Nasiri, M.; Ghasemi, V.; Khiabani, A.; Dashti, S.; Mohamadkhani Shahri, L. Prevalence of Postpartum Dyspareunia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 153, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abidi, I.; Bettaieb, H.; Halouani, S.; Frikha, M.; Mbarki, W.; Boufarguine, R.; Gabsi, H.; Oueslati, H.; Mbarki, C. 265 Postpartum Dyspareunia and Sexual Functioning: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Sex. Med. 2022, 19, S227–S228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemi, V.; Beheshti Nasab, M.; Saei Ghare Naz, M.; Shahsavari, S.; Banaei, M. Estimating the Prevalence of Dyspareunia According to Mode of Delivery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozkurt, M.; Yumru, A.E.; Şahin, L. Pelvic Floor Dysfunction, and Effects of Pregnancy and Mode of Delivery on Pelvic Floor. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014, 53, 452–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefsson, M.L.; Sohlberg, S.; Ekéus, C.; Uustal, E.; Jonsson, M. Self-Reported Dyspareunia and Outcome Satisfaction after Spontaneous Second-Degree Tear Compared to Episiotomy: A Register-Based Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0315899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, E.A.; Gartland, D.; Small, R.; Brown, S.J. Dyspareunia and Childbirth: A Prospective Cohort Study. BJOG 2015, 122, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziottin, A.; Simone, N.D.; Guarano, A. Postpartum Care: Clinical Considerations for Improving Genital and Sexual Health. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 296, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.Z.; Madley-Dowd, P.; Ahlqvist, V.H.; Jónsson-Bachmann, E.; Fraser, A.; Forbes, H. Mode of Delivery and Maternal Sexual Wellbeing: A Longitudinal Study. BJOG 2022, 129, 2010–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, K.; Worda, C.; Leipold, H.; Gruber, C.; Husslein, P.; Wenzl, R. Does the Mode of Delivery Influence Sexual Function after Childbirth? J. Womens Health Larchmt 2009, 18, 1227–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, K.J.; Orr, N.L.; Lisonek, M.; Noga, H.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Williams, C.; Allaire, C.; Albert, A.Y.; Smith, K.B.; Cox, S.; et al. Deep Dyspareunia, Superficial Dyspareunia, and Infertility Concerns Among Women With Endometriosis: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sex. Med. 2020, 8, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, J.P.; Jung, J.; Lavin, T.; Simpson, G.; Kluwgant, D.; Abalos, E.; Diaz, V.; Downe, S.; Filippi, V.; Gallos, I.; et al. Neglected Medium-Term and Long-Term Consequences of Labour and Childbirth: A Systematic Analysis of the Burden, Recommended Practices, and a Way Forward. Lancet Glob. Health 2024, 12, e317–e330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattani, L.; De Maeyer, L.; Verbakel, J.Y.; Bosteels, J.; Deprest, J. Predictors for Sexual Dysfunction in the First Year Postpartum: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BJOG 2022, 129, 1017–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gommesen, D.; Nøhr, E.; Qvist, N.; Rasch, V. Obstetric Perineal Tears, Sexual Function and Dyspareunia among Primiparous Women 12 Months Postpartum: A Prospective Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e032368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagaert, L.; Weyers, S.; Van Kerrebroeck, H.; Elaut, E. Postpartum Dyspareunia and Sexual Functioning: A Prospective Cohort Study. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2017, 22, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, L.M.; Rogers, R.G. Sex after Childbirth: Postpartum Sexual Function. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 119, 647–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipschuetz, M.; Cohen, S.M.; Liebergall-Wischnitzer, M.; Zbedat, K.; Hochner-Celnikier, D.; Lavy, Y.; Yagel, S. Degree of Bother from Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in Women One Year after First Delivery. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2015, 191, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sherman, L.; Foster, M. Patients’ and Providers’ Perspectives on Sexual Health Discussion in the United States: A Scoping Review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2020, 103, 2205–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Dakn, M.; Schäfers, R.; Peterwerth, N.; Asmushen, K.; Bässler-Weber, S.; Boes, U.; Bosch, A.; Ehm, D.; Fischer, T.; Greening, M.; et al. Vaginal Birth at Term—Part 1. Guideline of the DGGG, OEGGG and SGGG (S3-Level, AWMF Registry No. 015/083, December 2020). Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd 2022, 82, 1143–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeahialam, N.A.; Sultan, A.H.; Thakar, R. The Prevention of Perineal Trauma during Vaginal Birth. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S991–S1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, J.K.; Sood, A.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Vogel, J.P. Position in the Second Stage of Labour for Women without Epidural Anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 5, CD002006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, K.F.; Kibuka, M.; Thornton, J.G.; Jones, N.W. Maternal Position in the Second Stage of Labour for Women with Epidural Anaesthesia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD008070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayerle, G.M.; Mattern, E.; Striebich, S.; Oganowski, T.; Ocker, R.; Haastert, B.; Schäfers, R.; Seliger, G. Effect of Alternatively Designed Hospital Birthing Rooms on the Rate of Vaginal Births: Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial Be-Up. Women Birth 2023, 36, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Third- and Fourth-Degree Perineal Tears, Management (Green-Top Guideline No. 29). Available online: https://www.rcog.org.uk/guidance/browse-all-guidance/green-top-guidelines/third-and-fourth-degree-perineal-tears-management-green-top-guideline-no-29/ (accessed on 24 May 2023).

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Harrell, F.E., Jr. Describing, Resampling, Validating, and Simplifying the Model. In Regression Modeling Strategies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Marvi, N.; Heidarian Miri, H.; Hooshmand, E.; Abdollahpour, S.; Zamani, M. The Association of Mode of Delivery and Dyspareunia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022, 42, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jericevic Schwartz, D.; Cervantes, I.; Nwaba, A.U.A.; Duarte Thibault, M.; Siddique, M. Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury and Female Sexual Dysfunction: A Systematic Review. Urogynecol. Phila 2024, 31, 292–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, V.; Thakar, R.; Sultan, A.H.; Jones, P.W. Evaluation of Postpartum Perineal Pain and Dyspareunia—A Prospective Study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2008, 137, 152–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodstad, K.; Staff, A.C.; Laine, K. Sexual Activity and Dyspareunia the First Year Postpartum in Relation to Degree of Perineal Trauma. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2016, 27, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, M.; Larsson, C.; Lehmann, J.-P.; Strigård, K.; Lindam, A.; Tunón, K. Sonographic Postpartum Anal Sphincter Defects and the Association with Pelvic Floor Pain and Dyspareunia. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2023, 102, 1290–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edqvist, M.; Ajne, G.; Teleman, P.; Tegerstedt, G.; Rubertsson, C. Postpartum Perineal Pain and Its Association with Sub-Classified Second-Degree Tears and Perineal Trauma-A Follow-up of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2024, 103, 2314–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmer, H.; Bachholz, G.; Bichler, A.; Frudinger, A.; Neunteufel, W.; Tammaa, A.; Umek, W.; Wunderlich, M. Leitlinie Zum Management von Dammrissen III. Und IV. Grades Nach Vaginaler Geburt. In S3-Leitlinie; Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bidwell, P.; Sevdalis, N.; Silverton, L.; Harris, J.; Gurol-Urganci, I.; Hellyer, A.; Freeman, R.; van der Meulen, J.; Thakar, R. Women’s Experiences of the OASI Care Bundle; a Package of Care to Reduce Severe Perineal Trauma. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2021, 32, 1807–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manresa, M.; Pereda, A.; Goberna-Tricas, J.; Webb, S.S.; Terre-Rull, C.; Bataller, E. Postpartum Perineal Pain and Dyspareunia Related to Each Superficial Perineal Muscle Injury: A Cohort Study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2020, 31, 2367–2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlgren, H.; Jansson, F.; Hiyoshi, A.; Nilsson, K. Sexual Function in Primiparous Women: A Prospective Study. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2022, 33, 1567–1582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Fernández, M.J.; de Medina-Moragas, A.J. Comparative Study of Postpartum Sexual Function: Second-Degree Tears versus Episiotomy Outcomes. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 309, 2761–2769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manresa, M.; Pereda, A.; Bataller, E.; Terre-Rull, C.; Ismail, K.M.; Webb, S.S. Incidence of Perineal Pain and Dyspareunia Following Spontaneous Vaginal Birth: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. Urogynecol. J. 2019, 30, 853–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhandari Randhawa, S.; Rizkallah, A.; Nelson, D.B.; Duryea, E.L.; Spong, C.Y.; Pruszynski, J.E.; Rahn, D.D. Factors Associated with Persistent Sexual Dysfunction and Pain 12 Months Postpartum. Sex. Reprod. Healthc. 2024, 41, 101001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Qian, X.; Carroli, G.; Garner, P. Selective versus Routine Use of Episiotomy for Vaginal Birth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 2, CD000081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertozzi, S.; Londero, A.P.; Fruscalzo, A.; Driul, L.; Delneri, C.; Calcagno, A.; Di Benedetto, P.; Marchesoni, D. Impact of Episiotomy on Pelvic Floor Disorders and Their Influence on Women’s Wellness after the Sixth Month Postpartum: A Retrospective Study. BMC Womens Health 2011, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kettle, C.; Dowswell, T.; Ismail, K.M. Continuous and Interrupted Suturing Techniques for Repair of Episiotomy or Second-Degree Tears. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012, 11, CD000947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnittka, E.M.; Lanpher, N.W.; Patel, P. Postpartum Dyspareunia Following Continuous Versus Interrupted Perineal Repair: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2022, 14, e29070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, R.; Bollag, L.; Ortner, C. Chronic Pain after Childbirth. Int. J. Obstet. Anesth. 2013, 22, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karahan, N.; Arslan, H.; Çam, Ç. The Behaviour of Pelvic Floor Muscles during Uterine Contractions in Spontaneous and Oxytocin-Induced Labour. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2018, 38, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barba, M.; Bernasconi, D.P.; Manodoro, S.; Frigerio, M. Risk Factors for Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2022, 158, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearney, R.; Miller, J.M.; Ashton-Miller, J.A.; DeLancey, J.O.L. Obstetric Factors Associated with Levator Ani Muscle Injury after Vaginal Birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boll, S.; Almeida de Minas, A.C.; Raftogianni, A.; Herpertz, S.C.; Grinevich, V. Oxytocin and Pain Perception: From Animal Models to Human Research. Neuroscience 2018, 387, 149–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rash, J.A.; Aguirre-Camacho, A.; Campbell, T.S. Oxytocin and Pain: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Findings. Clin. J. Pain. 2014, 30, 453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monks, D.T.; Palanisamy, A. Oxytocin: At Birth and beyond. A Systematic Review of the Long-Term Effects of Peripartum Oxytocin. Anaesthesia 2021, 76, 1526–1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, M.J.; Campbell, T.S.; Robert, M.; Nasr-Esfahani, M.; Rash, J.A. Intranasal Oxytocin as a Treatment for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Randomized Controlled Feasibility Study. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 152, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, L.; Hilton, G.; Carvalho, B. The Impact of Breastfeeding on Postpartum Pain after Vaginal and Cesarean Delivery. J. Clin. Anesth. 2015, 27, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermesch, A.C.; Kernberg, A.S.; Layoun, V.R.; Caughey, A.B. Oxytocin: Physiology, Pharmacology, and Clinical Application for Labor Management. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2024, 230, S729–S739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hassett, A.L.; Seng, J.S. Exploring the Mutual Regulation between Oxytocin and Cortisol as a Marker of Resilience. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 33, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, J.S. Posttraumatic Oxytocin Dysregulation: Is It a Link among Posttraumatic Self Disorders, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Pelvic Visceral Dysregulation Conditions in Women? J. Trauma. Dissoc. 2010, 11, 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurol-Urganci, I.; Bidwell, P.; Sevdalis, N.; Silverton, L.; Novis, V.; Freeman, R.; Hellyer, A.; van der Meulen, J.; Thakar, R. Impact of a Quality Improvement Project to Reduce the Rate of Obstetric Anal Sphincter Injury: A Multicentre Study with a Stepped-Wedge Design. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 128, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perelmuter, S.; Stokes, C.; Chapalamadugu, M.; Drian, A.; Zusman, G.L.; Berdugo, J.; Davide, M.; Andy, C.; Grant, R.; Drew, T.; et al. Postpartum and Lactation-Related Genitourinary Symptoms: A Systematic Review. Obstet. Gynecol. 2025, 146, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alligood-Percoco, N.R.; Kjerulff, K.H.; Repke, J.T. Risk Factors for Dyspareunia After First Childbirth. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 128, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, N.O.; Dawson, S.J.; Binik, Y.M.; Pierce, M.; Brooks, M.; Pukall, C.; Chorney, J.; Snelgrove-Clarke, E.; George, R. Trajectories of Dyspareunia From Pregnancy to 24 Months Postpartum. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 139, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Degree | Extension of Injury |

|---|---|

| First degree (I°) | Injury to perineal skin and/or vaginal mucosa |

| Second degree (II°) | Injury to perineum involving perineal muscles but not involving the anal sphincter |

| Third degree (III°/OASIs) | Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex |

| Grade 3a tear | Less than 50% of external anal sphincter thickness torn |

| Grade 3b tear | More than 50% of EAS thickness torn |

| Grade 3c tear | Both EAS and internal anal sphincter torn |

| Fourth degree (IV°/OASIs) | Injury to perineum involving the anal sphincter complex (EAS and IAS) and anorectal mucosa |

| Dyspareunia | No Dyspareunia | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | N | N | ||

| 3264 | 476 | 2788 | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 28.5 (SD 4.09) | 28.3 (SD 4.48) | 28.6 (SD 4.02) | 0.215 |

| Fetal birth weight (g) | 3368 (SD 422) | 3374 (SD 444) | 3367 (SD 418) | 0.734 |

| Duration of delivery | ||||

| First stage of delivery (min) | 385 (SD 193) | 397 (SD 192) | 383 (SD 193) | 0.143 |

| Second stage of delivery (min) | 62 (SD 31.6) | 60.1 (SD 48.2) | 63.3 (SD 53.8) | 0.208 |

| Total delivery (min) | 448 (SD 236) | 455 (SD 210) | 447 (SD 240) | 0.485 |

| Dyspareunia | No Dyspareunia | Odds Ratio [95% CI] | p-Ratio | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N | % | N | % | N | |||

| Birthing method | 3264 | 100 | 476 | 100 | 2788 | ||

| Bed delivery | 1198 | 39.3 | 187 | 36.3 | 1011 | Reference variable | Ref |

| Other vaginal delivery | 416 | 11.6 | 55 | 12.9 | 361 | 0.83 [0.59–1.13] | 0.240 |

| Water delivery | 1137 | 29.4 | 140 | 35.8 | 997 | 0.76 [0.60–0.96] | 0.022 |

| Vacuum delivery | 513 | 19.7 | 94 | 15.0 | 419 | 1.21 [0.92–1.59] | 0.168 |

| Perineal injury | 3032 | 100 | 442 | 100 | 2590 | ||

| Intact perineum | 762 | 15.8 | 70 | 26.7 | 692 | Reference variable | Ref |

| I°/II° perineal tear | 1300 | 53.6 | 237 | 41.0 | 1063 | 2.20 [1.67–2.94] | <0.001 |

| OASIs (III°/IV°) | 187 | 8.8 | 39 | 5.7 | 148 | 2.61 [1.68–3.99] | <0.001 |

| Episiotomy | 783 | 21.7 | 96 | 26.5 | 687 | 1.38 [1.00–1.92] | 0.052 |

| Use of oxytocin | 3264 | 100 | 476 | 100 | 2788 | ||

| No oxytocin | 1304 | 35.5 | 169 | 40.7 | 1135 | Reference variable | Ref |

| Oxytocin in 1st stage | 68 | 1.5 | 7 | 2.2 | 61 | 0.79 [0.32–1.64] | 0.545 |

| Oxytocin in 2nd stage | 788 | 23.7 | 113 | 24.2 | 675 | 1.12 [0.87–1.45] | 0.37 |

| Oxytocin in 1st and 2nd stage | 1104 | 39.3 | 187 | 32.9 | 917 | 1.37 [1.09–1.72] | 0.006 |

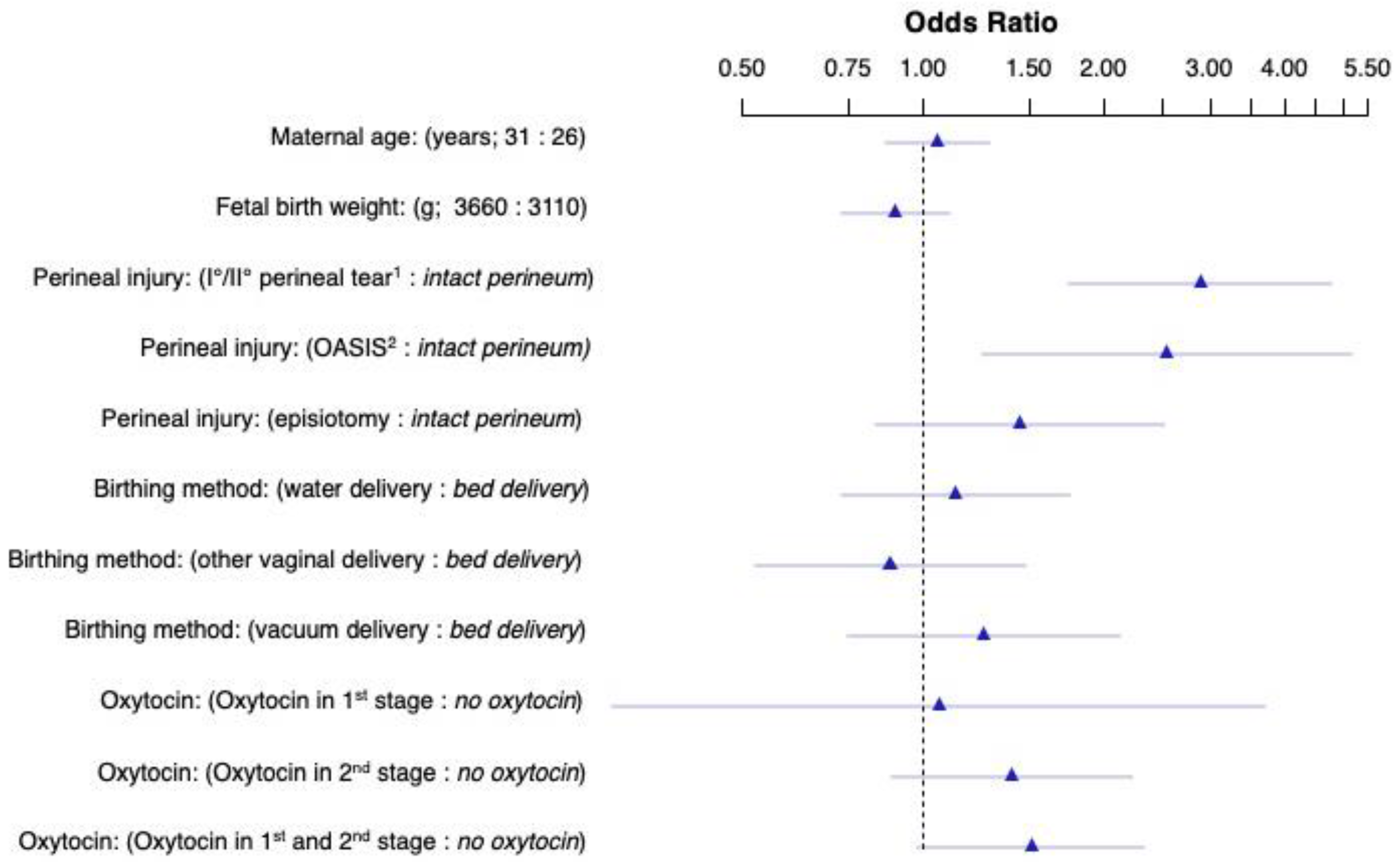

| Variable | OR | Lower 0.95 CI | Upper 0.95 CI | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 1.05 | 0.87 | 1.28 | 0.602 |

| Fetal birth weight (g) | 0.90 | 0.73 | 1.11 | 0.308 |

| Perineal injury: I/II° perineal tear vs. intact perineum | 2.89 | 1.76 | 4.77 | <0.001 |

| Perineal injury: OASIs vs. intact perineum | 2.54 | 1.25 | 5.16 | 0.010 |

| Perineal injury: episiotomy vs. intact perineum | 1.45 | 0.83 | 2.52 | 0.188 |

| Birthing method: other delivery vs. bed delivery | 1.13 | 0.68 | 1.90 | 0.632 |

| Birthing method: water delivery vs. bed delivery | 1.28 | 0.77 | 2.13 | 0.337 |

| Birthing method: vacuum delivery vs. bed delivery | 1.43 | 0.81 | 2.53 | 0.216 |

| Oxytocin: in 1st stage vs. no oxytocin | 1.06 | 0.30 | 3.71 | 0.924 |

| Oxytocin: in 2nd stage vs. no oxytocin | 1.40 | 0.89 | 2.22 | 0.148 |

| Oxytocin: in 1st and 2nd stage vs. no oxytocin | 1.52 | 0.98 | 2.33 | 0.059 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zachariah, R.R.; Forst, S.; Hodel, N.; Geissbuehler, V. Exploring the Link Between Vaginal Delivery and Postpartum Dyspareunia: An Observational Study. Reprod. Med. 2025, 6, 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040033

Zachariah RR, Forst S, Hodel N, Geissbuehler V. Exploring the Link Between Vaginal Delivery and Postpartum Dyspareunia: An Observational Study. Reproductive Medicine. 2025; 6(4):33. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040033

Chicago/Turabian StyleZachariah, Rebecca Rachel, Susanne Forst, Nikolai Hodel, and Verena Geissbuehler. 2025. "Exploring the Link Between Vaginal Delivery and Postpartum Dyspareunia: An Observational Study" Reproductive Medicine 6, no. 4: 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040033

APA StyleZachariah, R. R., Forst, S., Hodel, N., & Geissbuehler, V. (2025). Exploring the Link Between Vaginal Delivery and Postpartum Dyspareunia: An Observational Study. Reproductive Medicine, 6(4), 33. https://doi.org/10.3390/reprodmed6040033