Abstract

Object identification (OI) is widely used in fields like autonomous driving, security, robotics, environmental monitoring, and medical diagnostics. OI using infrared (IR) images provides high visibility in low light for all-day operation compared to visible light. However, the low contrast often causes OI failure in complex scenes with similar target and background temperatures. Therefore, there is a stringent requirement to enhance IR image contrast for accurate OI, and it is ideal to develop a fully automatic process for identifying objects in IR images under any lighting condition, especially in photon-deficient conditions. Here, we demonstrate for the first time a highly accurate automatic IR OI process based on the combination of polarization IR imaging and artificial intelligence (AI) vision (Yolov7), which can quickly identify objects with a high discrimination confidence level (DCL, up to 0.96). In addition, we demonstrate that it is possible to achieve accurate IR OI in complex environments, such as photon-deficient, foggy conditions, and opaque-covered objects with a high DCL. Finally, through training the model, we can identify any object. In this paper, we use a UAV as an example to conduct experiments, further expanding the capabilities of this method. Therefore, our method enables broad OI applications with high all-day performance.

1. Introduction

Object identification (OI) [1] is one of the promising areas where computer vision technologies can be applied, e.g., OI in static photographs, videos, or real-time scenarios, such as self-driving vehicles [2], rescue [3], biometric [4] and facial recognition [5], safety control [6], crowd counting [7] and traffic monitoring [8], inventory and warehousing [9], quality control [10], medical image analysis [11], and crop monitoring [12] and pest detection [13]. In particular, OI is a key technology for realizing the concept of autonomous cars and assisting vehicles in navigating our visual world. The technology of OI in a visible light environment has been well developed. However, several key issues need to be addressed to further improve its capabilities. For example, visible light OI cannot work properly under photon-deficient conditions, such as during nighttime. In addition, the visible light OI cannot work in foggy, rainy, or smoky environments, or an object may not be properly identified when it is hiding in a complex environment. Therefore, it is desired to develop OI technology beyond the visible wavelength range to operate under such conditions.

In comparison, infrared (IR) imaging [14,15] is a technique for measuring the temperature distribution of a scene by detecting thermal radiation differences between the object and the background. Any object with a temperature higher than absolute zero (−273.15 °C) emits thermal radiation according to Planck’s law of black body radiation [16], which is detectable by thermal cameras. As a result, IR imaging can work under any lighting conditions, particularly in low-light conditions. More importantly, weather conditions, e.g., rainy, foggy, or smoky, do not significantly affect IR imaging performance. This technology can work day and night without being significantly affected by environmental conditions. However, when the target and background temperatures are identical, distinguishing the target from the background cannot be achieved with infrared imaging alone. Moreover, with the development of optoelectronic countermeasures [17], stealth materials and stealth techniques will affect infrared detection [18].

In addition to thermal radiation, the surface of an object has an important photophysical property polarization. The polarization properties of man-made objects and natural backgrounds differ significantly; thus, polarization imaging offers unique advantages for object identification, allowing broad applications. For example, it has been demonstrated that IR polarization images enable the detection of an aircraft obscured by smoke [19] and enhance image quality, including resolution, details, and contrast [20]. Although infrared polarization imaging is relatively mature for object identification, recognition results are often evaluated by the human eye. There have been no studies addressing the role of polarization in improving OI accuracy, and no quantitative characterization of the recognition results of IR polarization imaging. To conduct a quantitative analysis of OI performance, it is necessary to incorporate machine vision [21,22,23] for a more accurate assessment. Machine vision has been widely applied in remote sensing [24], agriculture [25], transportation [26], and other fields.

Here, we demonstrate for the first time a highly accurate automatic IR object identification process based on the combination of polarization IR imaging and artificial intelligence (AI) vision (Yolov7), which can quickly identify objects (cars and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)) with a high discrimination confidence level (DCL, up to 0.96). The DCL represents the degree to which a model is certain about its individual prediction results, typically expressed as a probability value. In simple terms, DCL is a mechanism that encourages the model to “tell the truth”, enabling it to provide a more honest and accurate assessment of the quality of its detected bounding boxes. This ultimately enhances the overall reliability of detection. By processing the polarization properties, including the degree of linear polarization (DOLP) and the angle of polarization (AOP), we find that the contrast can be significantly enhanced and that the background can be largely removed, thereby improving the DCL. Moreover, we demonstrate that it is possible to achieve accurate IR OI in complex environments, such as photon-deficient, foggy conditions and opaque-covered objects, thereby highlighting the unique advantage of IR OI over visible light OI. In addition, we further demonstrate the OI of UAVs by training Yolov7 on images of UAVs that are not in the database. Our work further expands the capability of IR OI, thus finding broad applications in OI with high all-day performance.

2. Design of the Automatic Infrared Object Identification System

The conceptual demonstration of our designed automatic IR OI system is shown in Figure 1, which can quickly identify objects in the scene (Figure 1a) and can handle multiple identifiable objects, using the system shown in Figure 1b. The OI system includes a high-resolution IR camera (FLIR T560 with 640 × 480 pixels) (FLIR, Wilsonville, OR, USA) with a linear polarizer (WP25M-IRC) (Thorlabs, Newton, NJ, USA) in front, which is mounted on a rotational mount to take polarization images at different angles (0°, 45°, 90°, and 135° in this study) sequentially. There are four common types of polarization imaging systems: (1) division of time polarization imaging systems (DoTP) [27,28], (2) division of amplitude polarization imaging systems (DoAmP) [29], (3) division of aperture polarization imaging systems (DoAP) [30], and (4) division of focal-plane array polarization imaging systems (DoFP) [31] (detailed information and characteristics of all the polarization imaging systems is provided in Supplementary Section S1). Here, DOTP by rotating the linear polarizer is used because of the simple setup, which can be generally applied to any commercial IR camera without requiring the modification of the structure of the IR camera. In addition, the DoTP does not require a specially designed algorithm to process the data.

Figure 1.

Conceptual diagram of the designed automatic IR OI system. (a) The scene and (b) the OI process.

The Stokes vector [32] is defined as (S0, S1, S2, S3)T, where S0 = I = E0x2 + E0y2 is the light intensity, and E0x and E0y are the electric field along x and y directions, respectively. Meanwhile, S1 = E0x2 − E0y2 is the difference between horizontally and vertically polarized light intensities. S2 = 2E0xE0ycosΦ is the difference between linear 45° and 135° light intensities, and S3 = 2E0xE0ysinΦ is the difference between left-handed circularly polarized (LCP) and right-handed circularly polarized (RCP) light intensities. Φ is the phase difference between E0x and E0y. Since this paper focuses on linearly polarized light, S3 is regarded as 0. The value usually normalizes these three quantities S0, so it is between 0 and 1. In the experiment, polarization images are taken at four different angles, 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°; then, the Stokes calculation is performed. I1, I2, I3, and I4 denote the light intensity of 0°, 90°, 45°, and 135° polarized images, respectively. So, here S0 = I = I1 + I2, S1 = Q = I1 − I2, and S2 = U = I3 − I4.

The Stokes components calculated above can be used to solve for the angle of polarization (AOP) and the degree of polarization (DOLP). The angle of polarization (AOP) is the angle with respect to the x-axis, expressed in terms of the Stokes vector as

The degree of polarization (DOLP) is the fraction of the intensity attributable to the state of linearly polarized light and is expressed in terms of the Stokes vector as

3. Results

3.1. Infrared Polarization Object Identification of a Single Target

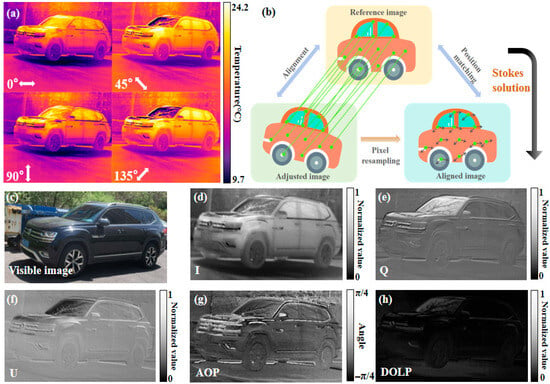

We first study the IR OI using polarization images with a single tarobtain, which is a vehicle (TRAMONT 380tsi) in this case, as shown in the photo in Figure 2c. The camera emissivity is set to ε = 0.8, and the temperature detection range is set to −20 °C to 250 °C. The polarization IR images, along the angles of 0°, 45°, 90°, and 135°, are shown in Figure 2a. The windshield presents shadows of different contrasts at four different polarization angles. In the scene, the shadow is weaker in the 0° image and 90° image, and stronger in the 45° image and 135° image. This is due to the fact that the windshield is close to the Brewster angle and has a different transmittance for particular polarized states, where the reflected IR light from the windshield is stronger at 0° and 90° and weaker at 45° and 135°. In order to get accurate Stokes images, we perform scale-invariant feature transform (SIFT) [33] to align the four images. SIFT is an algorithm used for image alignment and stitching by detecting key points in an image and computing their local feature descriptions, which is schematically shown in Figure 2b. It is found that the SIFT process plays an important role in DoTP systems, since slight vibration during the imaging process causes misalignment of the images, even during a high-speed imaging process, compromising the quality of the Stokes images. The current research mainly focuses on stationary objects to demonstrate the advantages of polarization IR imaging in enhancing the OI results. We used the division of time polarization imaging systems (DoTP), and the SIFT method was used to accurately align target and background pixels simultaneously. In future work on capturing fast-moving objects, tracking techniques can be used to maintain the object at a consistent position within the frame while minimizing capture time. Furthermore, the SIFT method can be used for alignment to ensure that the fast-moving object can be clearly identified in the IR polarization images, which will be the next stage of the work.

Figure 2.

(a) Infrared polarization images of different polarization angles. (b) Schematic of the SIFT method. (c) Visible image. (d) I image. (e) Q image. (f) U image. (g) AOP image. (h) DOLP image.

This intensity (I) image is shown in Figure 2d, which fuses the total IR radiation intensity information of the four polarization angles, including the target and the background. In comparison, the Q and U images shown in Figure 2e,f can effectively suppress background information, such as trees and shadows on the ground. Compared to other types of polarization images, these two images highlight the profile and the details of the object (the car in the theme), due to the linear polarization properties of the man-made objects. The Q image is sensitive to the polarization properties in the horizontal and vertical directions. Meanwhile, the U image is decided by the polarization properties along the oblique direction. Therefore, the vertical surface on the door shows high brightness in the U image, and the windshield shows high brightness in the Q image. As window bumpers, etc., are made of different materials with varying smoothness, resulting in different angles of polarization, the AOP image shown in Figure 2g can be used to clearly distinguish between different materials in the theme. The metallic edges of the windows and the front grille appear brighter than other parts. However, it shows a messier background, interrupting the overall profile of the car, which may affect the OI process. The DOLP image in Figure 2h exhibits a relatively low gray value, as the degree of polarization is influenced by the surface roughness and material of the object. One can see that the smooth surface of the windshield has a relatively high degree of polarization as the light is reflected by the surface very close to the Brewster angle with minimum scattering. In comparison, the car door and other parts exhibit a relatively low degree of polarization due to surface roughness and the reflection angle.

Then, AI vision is used to identify the object in the polarization IR images. Here, a software called “You Only Look Once (Yolo)” is used, which is an OI algorithm proposed by Joseph Redmon et al. in 2015 [34]. Yolov7 [35] is the seventh version of the Yolo series. The Yolov7 OI algorithm can currently recognize more than 80 kinds of objects in daily life, such as people, bicycles, cars, motorcycles, etc. The speed and accuracy of Yolov7 have already surpassed most of the known object identifiers, and it requires low computational power and cost, which can meet the requirements of fast OI in IR images. Yolov7 comprises five parts (shown in Figure 3a): input, backbone, neck, head, and output. First, the image is fed into the backbone network after a series of pre-processing operations, such as data enhancement in the input section, and the backbone network performs feature extraction on the processed image. Subsequently, the extracted features are processed by neck’s feature fusion to obtain features of three sizes: large, medium, and small. Eventually, the fused features are fed into the head, and the results are output after OI. The output includes the identification box and the discrimination confidence level (DCL). The identification box will frame the object in the image. DCL from 0 to 1 indicates how confident the model is that the object exists in the prediction frame. A DCL close to 1 means that the model is very confident that the prediction box contains the object. If the DCL is close to 0, it means that the model thinks that the prediction box may not contain the object.

Figure 3.

OI results of infrared polarization imaging of a single target (a vehicle) by Yolov7. (a) Identification process of Yolov7, (b) OI result of Q image, (c) OI result of U image, (d) OI result of Q image, (e) OI result of DOLP image.

The OI results from Yolov7 are shown in Figure 3. One example is the optical photo, which is used to benchmark the DCL. The DCL of the optical photo (the last panel in the first row in Figure 3a) is 0.94, also shown in Supplement Figures S1 and S2. In comparison, the DCL of the I image is 0.95 (the last panel in the second row of Figure 3a), demonstrating the advantages of OI in IR images. The DCL of the Q and U images is up to 0.96, as seen in Figure 3b,e, due to the removal of background, confirming the capability of achieving a higher DCL by using polarization imaging. This is an improvement over the DCL of 0.95 for the I image. This means that these two polarization images are useful for object identification because they highlight the object profile. Also, compared with the highest DCL of 0.93 for the high-resolution photo of the same model vehicle on Volkswagen’s official website (Supplementary Figure S1), the DCL of 0.96 is a very high level of identification.

In comparison, although the AOP image in Figure 3d shows a lot of information, such as the roughness and the difference in materials compared to the intensity image, its DCL is not the highest, only 0.62, which could be attributed to the fact that the background information interrupts the profile of the car. The DCL of the AOP image can be significantly improved to 0.92 through image fusion and edge extraction (the detailed process is shown in Supplementary Sections S4 and S5). In comparison, the DCL of the DOLP image from Figure 3e is surprisingly high (0.93) despite the overall dark image. The reason is that the polarization of man-made and natural objects is significantly different, so the natural background is suppressed in the polarization image, leaving the remaining information primarily composed of man-made objects. In addition, we found that DOLP images achieve remarkable results in OI. So far, we have achieved accurate and automatic OI in IR polarization images via AI vision, confirming the feasibility and accuracy of OI in polarization images. The method also applies to OI in IR polarization images with a small number of pixels, to improve the DCL (Supplementary Section S6).

3.2. Infrared Polarization Object Identification of Multiple Targets

In practice, a scene typically contains multiple complex objects, with the possibility of overlap and occlusion. The method presented in this paper remains applicable to object recognition in complex scenes. The scenario selected for this work contains nine vehicles and one person, with objects overlapping. (See object labeling in multi-object images in Supplementary Section S7.) Figure 4 shows the results of OI with Yolov7 on IR polarization images, including the number and DCL of objects (including vehicles and a person). Statistically, each identification time is within 0.6 s, realizing fast and accurate OI in IR polarization images. Five vehicles (the DCL of the frontmost vehicle is 0.91) and one person (DCL is 0.89) are identified in the I image, which is shown in Figure 4b. As shown in Figure 4c,d, both the Q and U images significantly suppress the background, and both images highlight the profile of the car and the person, improving the number of identified cars and the DCL for both the vehicle and the person. As shown in Figure 4e, the AOP image contains significant polarization information, resulting in a more complex background and fewer identified cars, leading to a lower DCL than in the Q and U images. The result is consistent with the OI outcome of the single object shown in Figure 3. However, the DCL is still higher than the I image shown in Figure 4b, confirming the advantage of using polarization images in OI applications. In the DOLP image (Figure 4f), the windshields of the cars in the scene appear the whitest, indicating a high degree of polarization, which is similar to the results shown in Figure 3. The OI results of the DOLP image are similar to the Q and U images, confirming the advantages.

Figure 4.

Infrared polarization multiple object data processing and identification results of Yolov7. (a) infrared intensity images of four different polarization angles, (b) I image, (c) Q image, (d) U image, (e) AOP image, (f) DOLP image, (g) clarified AOP image, (h) fusion of Q and U images, (i) fusion of edge extraction of the I image (b), and clarified AOP image (g).

Additionally, we further process the polarization images to examine the effect on enhancing OI performance. We first sharpen the AOP image through a clarification process [36], enabling us to increase the number of identified vehicles to three. However, the DCLs of both vehicles and the person remain low, confirming that achieving good OI results in AOP images alone is challenging. Meanwhile, we fused the Q and U images with the optimal outcome to explore the possibility of further improving the results. One can see from Figure 4h that the fusion improves the DCL of the vehicles and the person. Finally, we applied the edge extraction technique on the I image (Figure 4b) and fused it with the sharpened AOP image (Figure 4g) to further increase the number of identified vehicles to seven. The principles of edge extraction and image fusion are described in Supplementary Notes S4 and S5. Therefore, the results demonstrate the potential to further improve OI performance in real-world scenes (containing multiple objects) by applying advanced image processing techniques to polarization images. Due to the overlapping vehicles at the edge, it is not possible to identify all nine vehicles in the scheme. The results demonstrate that the IR OI system can operate effectively in complex scenes, including those with multiple objects and overlapping features. DCL and accuracy can also be further improved by processing such as image fusion and edge extraction.

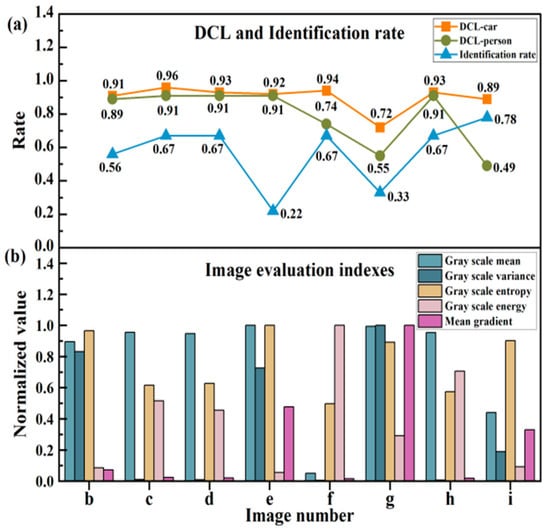

The OI results of all images are summarized in the line graph in Figure 5a. Most of the vehicle identification rates of the above methods exceed 0.5, and the DCLs are generally above 0.9, indicating the high feasibility and accuracy of OI in polarized images.

In addition, in order to further explore the relationship between the OI results and images, we also calculate and analyze the evaluation indices [37] of Figure 4b–i (See Supplementary Section S8 for original data), which is shown in Figure 5b, including gray scale mean, gray scale variance, gray scale entropy, gray scale energy, and mean gradient. The normalized values of the five evaluation indices are shown in the bar chart in Figure 5 (See Supplementary Section S9 for original data). Figure 4c,d,h has high DCL and identification rates, indicating low gray scale variance, suggesting that uniform gray scale distributions are preferred in the OI process. In comparison, when the gray scale variance is high, as in the AOP images, the identification rate is low. Therefore, it is found that DCL and accuracy are mainly affected by the gray scale variance.

4. Discussion

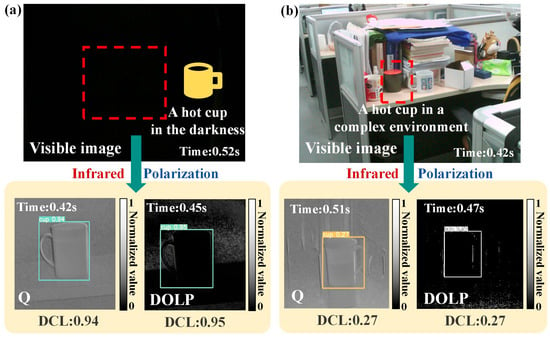

4.1. Performance Validation of the System in Photon-Deficient Environments

The experiments mentioned above were conducted under normal light intensity conditions to analyze different polarized images. To demonstrate the unique advantage of IR imaging under low-light (photon-deficient) conditions, Figure 6 further investigates the IR OI system’s performance in complex environments. The scene depicted in Figure 6a shows a hot cup placed in an extremely low-light environment. In a visible image, the cup cannot be seen by the eye or detected by AI vision. In comparison, the cup’s shape and its position within the scene can be extracted from infrared polarization imaging. Both the Q and DOLP images exhibit very high DCLs. As shown in Figure 6b, if a hot cup is placed in a cluttered scene, IR polarization imaging can clearly highlight it.

Figure 6.

OI in photon-deficient and chaotic environments. (a) OI results for a hot cup placed in darkness. (b) OI results for a hot cup placed in a complex environment among various objects.

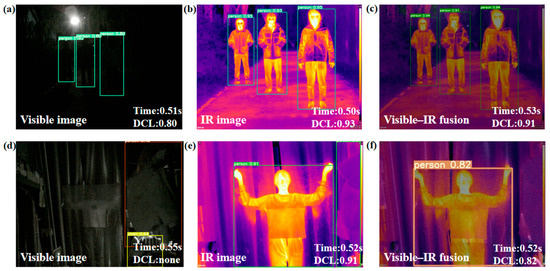

Furthermore, when interference factors in the scene increase, such as when objects are obscured by other objects in dark environments, IR polarization imaging can still distinguish target objects to a certain extent by leveraging its unique polarization characteristics. The scene depicted in Figure 7a shows three people standing in darkness, their heads covered with black plastic bags. At this point, in the visible light image, neither the human eye nor AI vision can effectively identify these three people. However, IR polarization imaging technology not only clearly captures the general outlines of the three people but also distinguishes the positions of their obscured heads. In addition, the profiles of the plastic bags and their heads can be clearly seen. This fully demonstrates that IR polarization imaging retains outstanding OI capabilities even in complex environments with numerous interfering factors.

Figure 7.

OI in dark and obscured environments. (a) OI results for three people wearing plastic bags (black) covering their heads in the darkness. (b) OI results for one person hiding behind a plastic sheet (white) under low-light conditions.

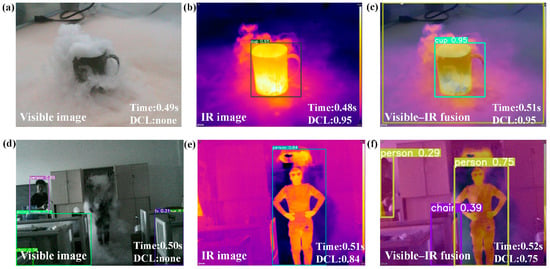

Under foggy conditions, conventional visible imaging technology will be disrupted, leading to blurred or even unrecognizable objects. Fog exhibits weak scattering of IR light, and different objects exhibit varying polarization characteristics for IR radiation. Therefore, IR polarization imaging can effectively penetrate fog to capture clear outlines and the position of objects. It is necessary to create a fully controlled indoor environment to quantitatively test the effects of foggy conditions on our OI results without being affected by complex outdoor situations. More importantly, since the real-world environment is uncontrollable and unstable, it cannot be representative and may affect the accuracy of our OI results. In this work, we generate the water mist using dry ice, which shows very similar physical properties of natural fog as a scattering medium [38] (due to the Tyndall effect [39]); therefore, it is suitable for the standard testing of OI performance in IR polarization images under scattering conditions. As shown in Figure 8, dry ice mist was used to simulate dense fog. The hot cup and the person were almost completely covered by the mist. Those objects were nearly invisible in the visible image, and the AI struggled to identify them in the foggy environment, though they are still clearly visible in the IR polarization images. More importantly, the IR polarization image can show a clear profile of the objects, allowing for the distinction from the background or obstacles for robust OI applications. In this way, we demonstrate the distinct advantages of IR polarization imaging over visible imaging in OI, which is less affected by environmental lighting and other interfering factors.

Figure 8.

Object extraction in foggy environments. (a) OI results for a hot cup in the fog. (b) OI results for one person in the fog.

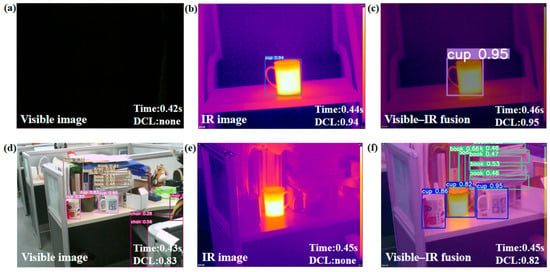

In Figure 3 of the manuscript, we compared the OI results for a single vehicle target across visible images, infrared images (I images), and various polarization images. We found that the DCL in IR-only images is higher than in visible images, confirming the robustness of the performance advantages of using IR polarization images. In addition, we performed OI on visible-IR fusion images as shown in Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11. It can be seen in Figure 9 that the visible-IR fusion can be useful when the object is clear in the visible images, which, however, will lower the DCL of the OI results in Figure 10 and Figure 11, when the object cannot be seen in visible images, for example, in dark or scattering (rainy/foggy) environments.

Figure 9.

OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 6. (a) OI results for visible image of Figure 6a. (b) OI results for IR image of Figure 6a. (c) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 6a. (d) OI results for visible image of Figure 6b. (e) OI results for IR image of Figure 6b. (f) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 6b.

Figure 10.

OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 7. (a) OI results for visible image of Figure 7a. (b) OI results for IR image of Figure 7a. (c) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 7a. (d) OI results for visible image of Figure 7b. (e) OI results for IR image of Figure 7b. (f) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 7b.

Figure 11.

OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 8. (a) OI results for visible image of Figure 8a. (b) OI results for IR image of Figure 8a. (c) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 8a. (d) OI results for visible image of Figure 8b. (e) OI results for IR image of Figure 8b. (f) OI results for Visible-IR image of Figure 8b.

However, in the foggy environment, the CNR and SNR are lower in the IR polarization images compared to optical images, in which AI still obtains better OI results in IR polarization images. Therefore, there is no direct relation between the image metrics (CNR, SNR, and PSNR) and OI results, which may be attributed to the different key features to identify objects used by AI, for example, the shape. This part of the information has been added to the Supplementary Section S11 in the revised Supplementary Materials.

In addition, we have presented an analysis of gradient-based metrics on different polarization images and the calculation of image evaluation indexes, including gray scale mean, gray scale variance, gray scale entropy, gray scale energy, and mean gradient, in Figure 5 (See Supplementary Section S9 for original data) of the manuscript and Section S8 of the Supplementary Materials. Figure 4c,d,h has high DCL and identification rates, indicating low gray scale variance, suggesting that uniform gray scale distributions are preferred in the OI process. In comparison, when the gray scale variance is high, as in the AOP images, the identification rate is low.

4.2. Multiple Arbitrary Infrared Object Identification Enabled by Model Training

The OI can now identify 80 types of objects. (See Supplementary Section S12 for the specific categories for Yolov7.) To make the method proposed in this work more universal and facilitate the OI of arbitrary objects in IR polarization images, we used a UAV as an example and trained a Yolov7 model for identifying the UAV. We collect the 1000 UAV dataset, and the number of training iterations is set to 100 due to limited computational power (see Supplementary Section S13 for the training steps, hyperparameters, validation split, loss curves, and assessments for overfitting for Yolov7). We find that the framework model trained on visible light datasets can be applied to OI in IR images. The OI results of the I image (Figure 12b) do not show the identified UAV. In comparison, Figure 12c,d shows the Q and U images in which the entire UAV can be clearly identified, corresponding to DCLs of 0.43 and 0.57, respectively, confirming the applicability of our training method. More importantly, Figure 11e shows a partially identified UAV with a substantially high DCL of 0.7. In this case, the details in the AOP image help to improve the DCL of the QI results. However, there is no identification result for the DOLP image due to the DOLP of the UAV surface, as shown by the dark color in the image. In addition to UAVs, we can train Yolov7 with any object species for OI applications using polarization IR images.

Figure 12.

UAV object acquisition and identification results. (a) Polarization images, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image.

The relatively low DCL is due to our limited computational resources, resulting in insufficient training time and iterations for the model. Additionally, our dataset of 1000 images may not be big enough to achieve a high DCL result. Moreover, the form factor and the characteristics of the drones in our own dataset differ from those in the built-in dataset in YOLOv7. However, this section verifies that it is possible to perform OI in IR polarization images of new objects through training. Although the DCL is not very high, the DCL for infrared polarization images is higher than that for infrared imaging alone, sufficiently demonstrating that IR polarization images enhance the OI performance.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have experimentally demonstrated a highly accurate automatic IR object identification process based on the combination of polarization IR imaging and Yolov7, which can quickly identify objects (cars and unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs)) with a high discrimination confidence level (DCL, up to 0.96) within 0.57 s, which is even higher than the DCL of an optical photo from the manufacturer’s website. Additionally, we demonstrate that this method can also be applied to enhance the DCL of OI in low-resolution IR images. More importantly, it is possible to achieve accurate IR OI in complex environments, such as photon-deficient (completely dark), foggy conditions and opaque-covered objects, highlighting the unique advantage of IR OI over visible light OI. More importantly, by training Yolov7 on images of a UAV not in the database, we can use this method to identify the UAV, thereby further expanding its capabilities. The training method can be applied to any object to achieve OI in IR polarization images. Combined with the unique advantages of its whole-day working capability, OI in polarization images shows great potential for real-world applications, especially under low-light conditions, such as at night and in foggy, rainy, or smoky environments. Therefore, this method can be applied across multiple fields, such as military reconnaissance, security surveillance, and autonomous driving.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/opt7010003/s1, Supplementary Note S1: Common Types of Polarization Imaging Systems; Supplementary Note S2: Introduction to Object Identification; Supplementary Note S3: The OI Results of the Visible Image; Supplementary Note S4: Improving DCL of AOP Images by Image Fusion; Supplementary Note S5: Improving DCL of AOP Image by Image Fusion and Edge Extraction; Supplementary Note S6: Effect of the Number of Pixels on the Identification Results; Supplementary Note S7: Object Labeling in Multi-Object Images; Supplementary Note S8: Calculation and Analysis of Image Evaluation Indexes; Supplementary Note S9: Original Data of Evaluation Indexes; Supplementary Note S10: OI Results of Visible-IR Fusion; Supplementary Note S11: Image Evaluation Metric Calculation and Analysis; Supplementary Note S12: Specific Categories; Supplementary Note S13: Steps for Self-Training Yolov7; Supplementary Note S14: OI Results of Yolov5; Figure S1: Discrimination confidence level (DCL) of the visible image on Volkswagen’s official website; Figure S2: DCL of the visible image in Figure 2; Figure S3: Image and identification results after fusion of AOP image with I, Q, and U images; Figure S4: Schematic of the principle of edge extraction and processing of AOP images; Figure S5: Group of low-pixel infrared polarization images, (a) polarization images, (b) I image, (c) Q polarization image, (d) U polarization image, (e) AOP image, (f) DOLP image; Figure S6: OI result of the image; Figure S7: (a) OI result of Q image, (b) OI result of U image, (c) OI result of AOP image, (d) OI result of clarification processing AOP, (e) OI result of fusion image of infrared image and AOP clarification image, (f) OI result of fusion image of edge extraction from thermal image and AOP clarification image; Figure S8: Object labeling in multi-object images; Figure S9: OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 6; Figure S10: OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 7; Figure S11: OI for the visible light and infrared image fusion method in the scene depicted in Figure 8; Figure S12: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 6a; Figure S13: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 8b; Figure S14: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 6a; Figure S15: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 6b; Figure S16: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 6b; Figure S17: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 7a; Figure S18: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 7a; Figure S19: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 7b; Figure S20: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 7b; Figure S21: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 8a; Figure S22: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 8a; Figure S23: Calculation results of the image evaluation metrics for Figure 8b; Figure S24: Yolov7 training flow using a drone as an example; Figure S25: Precision. Precision = TP / (TP + FP), the proportion of correctly predicted results among all predictions classified as positive. TP: true positives + false positives; Figure S26: Recall. Recall = TP / (TP + FN), the proportion of correctly predicted results among all instances with a true positive value; Figure S27: Recall–precision; Figure S28: Loss curves; Figure S29: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 2. (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S30: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 4. (a) OI result of I image, (b) OI result of Q image, (c) OI result of U im-age, (d) OI result of AOP image, (e) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S31: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 6(a). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S32: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 6(b). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S33: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 7(a). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S34: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 7(b). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S35: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 8(a). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image; Figure S36: OI results of Yolov5 for Figure 8(b). (a) OI result of visible image, (b) OI result of I image, (c) OI result of Q image, (d) OI result of U image, (e) OI result of AOP image, (f) OI result of DOLP image. Table S1: Original data of evaluation indexes; Table S2: Hyperparameters.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.J., H.F. and H.L.; methodology, R.J. and H.F.; software, R.J.; validation, H.F., H.L., Y.Y., X.L., M.Z. and L.X.; formal analysis, R.J. and H.F.; investigation, R.J. and H.F.; resources, H.F.; data curation, R.J.; writing—original draft preparation, R.J.; writing—review and editing, R.J. and H.L.; visualization, X.L.; supervision, H.F.; project administration, H.F.; funding acquisition, H.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1404201), the Young Scientists Fund of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 11904255), the Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT220100559, IH240100009, LE250100078, LP240100504), the Key R&D Program of Shanxi Province (International Cooperation) (201903D421052), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under Grants (U23A20375).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the useful discussions and suggestions from Yuan Tian.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| OI | Object identification |

| IR | Infrared |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DCL | Discrimination confidence level |

| AOP | Angle of polarization |

| DOLP | Degree of linear polarization |

| CNR | Contrast-to-noise ratio |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| PSNR | Peak signal-to-noise ratio |

References

- Tong, K.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, F. Recent advances in small object detection based on deep learning: A review. Image Vis. Comput. 2020, 97, 103910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresson, G.; Alsayed, Z.; Yu, L.; Glaser, S. Simultaneous localization and mapping: A survey of current trends in autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2017, 2, 194–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Liu, T. Underwater rescue target detection based on acoustic images. Sensors 2024, 24, 1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.Y.; Singhania, R.; Fehringer, G.; Chakravarthy, A.; Roehrl, M.H.; Chadwick, D.; Zuzarte, P.C.; Borgida, A.; Wang, T.T.; Li, T.; et al. Sensitive tumour detection and classification using plasma cell-free DNA methylomes. Nature 2018, 563, 579–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, P.; Krishan, K.; Sharma, S.K.; Kanchan, T. Facial-recognition algorithms: A literature review. Med. Sci. Law 2020, 60, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.Y.; Yu, H.L.; Li, H.; Zhou, C.; Wu, X.G.; Yu, M. Safety risk identification system for metro construction on the basis of construction drawings. Autom. Constr. 2012, 27, 120–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, C.C.; Chen, K.; Gong, S.; Xiang, T. Crowd counting and profiling: Methodology and evaluation. In Modeling, Simulation and Visual Analysis of Crowds: A Multidisciplinary Perspective; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 347–382. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.K.; Saini, R.K.; Mittal, P. A review on traffic monitoring system techniques. In Soft Computing: Theories and Applications: Proceedings of SoCTA 2017; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 569–577. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Liu, J.; Le, N.; Hu, H.; Jiang, L.; Wang, J. Identification model of personnel violations in material warehouse based on source information preprocessing. In Proceedings of the 3rd Asia-Pacific Conference on Image Processing, Electronics and Computers, Dalian, China, 14–16 April 2022; pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Hayter, A.J.; Tsui, K.-L. Identification and quantification in multivariate quality control problems. J. Qual. Technol. 1994, 26, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, D.; Wu, G.; Suk, H.-I. Deep learning in medical image analysis. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 19, 221–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña-Barragán, J.M.; Ngugi, M.K.; Plant, R.E.; Six, J. Object-based crop identification using multiple vegetation indices, textural features and crop phenology. Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 1301–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yue, Y. Pest identification via deep residual learning in complex background. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2017, 141, 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Huynh, C.P.; Solh, M. Domain-adaptive pedestrian detection in thermal images. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE international conference on image processing (ICIP), Taipei, Taiwan, 22–25 September 2019; pp. 1660–1664. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, H.; Li, Q.; Tao, C.; Hong, Y.; Xu, Z.; Shen, W.; Kaur, S.; Ghosh, P.; Qiu, M. Multispectral camouflage for infrared, visible, lasers and microwave with radiative cooling. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planck, M. Über die Begründung des Gesetzes der schwarzen Strahlung. Ann. Physic 1912, 342, 642–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, D.; De, S.; Raj, A.B.; Chaudhari, B.S. Design and implementation of a photonic-based electronic warfare system. J. Opt. Photonics Res. 2024, 2, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.T.; Zhou, X.D.; Chen, Y.G. Evaluation Techniques for Countermeasures and Counter-contermeasures Performance on Electro-optical Imaging Guided Systems. Laser Infrared 2007, 37, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, L.M.; Shaw, J.A.; Chenault, D.B. Detection of a poorly resolved airplane using SWIR polarization imaging. In Proceedings of the Polarization: Measurement, Analysis, and Remote Sensing XII, Baltimore, MD, USA, 18–19 April 2016; pp. 194–204. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Xu, W.; Sun, Z.; Wu, H.; Tian, Y.; Li, L. Mid-wave infrared polarization imaging system for detecting moving scene. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 5884–5887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.L.; Smith, L.N.; Hansen, M.F. The quiet revolution in machine vision-a state-of-the-art survey paper, including historical review, perspectives, and future directions. Comput. Ind. 2021, 130, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranft, B.; Stiller, C. The role of machine vision for intelligent vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2016, 1, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golnabi, H.; Asadpour, A. Design and application of industrial machine vision systems. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2007, 23, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumaah, H.J.; Rashid, A.A.; Saleh, S.A.R.; Jumaah, S.J. Deep neural remote sensing and Sentinel-2 satellite image processing of Kirkuk City, Iraq for sustainable prospective. J. Opt. Photonics Res. 2025, 2, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhao, E.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Wang, W.; Wang, R. Detection of Camellia oleifera fruit in complex scenes by using YOLOv7 and data augmentation. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Q.; Zhan, J.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. A driver fatigue detection algorithm based on dynamic tracking of small facial targets using YOLOv7. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2023, 106, 1881–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walraven, R. Polarization imagery. Opt. Eng. 1981, 20, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egan, W.G.; Johnson, W.R.; Whitehead, V.S. Terrestrial polarization imagery obtained from the Space Shuttle:characterization and interpretation. Appl. Opt. 1991, 30, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azzam, R.; Sudradjat, F. Single-layer-coated beam splitters for the division-of-amplitude photopolarimeter. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlick, G.F.J.; Steigmann, G.A.; Lamb, W.E. Differential Optical Polarization Detectors. U.S. Patent 3,992,571, 16 November 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Andreou, A.G.; Kalayjian, Z. Polarization imaging: Principles and integrated polarimeters. IEEE Sens. J. 2002, 2, 566–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzam, R.M.A. Stokes-vector and Mueller-matrix polarimetry. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 2016, 33, 1396–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Mota, J.; Bogdanova, I.; Paquier, B.; Bierlaire, M.; Thiran, J.-P. Scale invariant feature transform on the sphere: Theory and applications. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2012, 98, 217–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02696. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, T. How to pan-sharpen images using the gram-schmidt pan-sharpen method–A recipe. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2013, 40, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.J.; Su, L.; Yang, G.Y.; Zhao, J.S.; Cai, Y.; Pan, S.C. Images Processing and Evaluation of Middle Wave Infrared Polarization Imaging System. Infrared Technol. 2009, 31, 362–366. [Google Scholar]

- Puerto, D.B. Intrinsic and extrinsic scattering and absorption coefficients new equations in four-flux and two-flux models used for determining light intensity gradients. J. Opt. Photonics Res. 2024, 1, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmenstine, A.M. Tyndall effect definition and examples. Available online: https://sciencenotes.org/tyndall-effect-definition-and-examples/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.