Abstract

This paper presents a unified aerodynamic design and optimization framework for morphing Blended-Wing-Body (BWB) Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) operating in subsonic and near-transonic regimes. The proposed framework integrates parametric CAD modeling, Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), and surrogate-based optimization using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to establish a generalized approach for geometry-driven aerodynamic design under multi-Mach conditions. The study integrates classical aerodynamic principles with modern surrogate-based optimization to show that adaptive morphing geometries can maintain efficiency across varied flight conditions, establishing a scalable and physically grounded framework that advances real-time, high-performance aerodynamic adaptation for next-generation BWB UAVs. The methodology formulates the optimization problem as drag minimization under constant lift and wetted-area constraints, enabling systematic sensitivity analysis of key geometric parameters, including sweep, taper, and twist across varying flow regimes. Theoretical trends are established, showing that geometric twist and taper dominate lift variations at low Mach numbers, whereas sweep angle becomes increasingly significant as compressibility effects intensify. To validate the framework, a representative BWB UAV was optimized at Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 using a parametric ANSYS Workbench environment. Results demonstrated up to a 56% improvement in lift-to-drag ratio relative to an equivalent conventional UAV and confirmed the theoretical predictions regarding the Mach-dependent aerodynamic sensitivities. The framework provides a reusable foundation for conceptual design and optimization of morphing aircraft, offering practical guidelines for multi-regime performance enhancement and early-stage design integration.

1. Introduction

The aerodynamic design of BWB configurations has been a major focus of research in the search of high-efficiency aircraft that are capable of achieving significant drag reduction and improved lift-to-drag ratios compared to conventional tube-and-wing designs. The BWB concept integrates lifting and volumetric functions into a single continuous body, eliminating the aerodynamic discontinuities associated with fuselage–wing junctions and offering improved aerodynamic efficiency, payload volume utilization, and potential noise reduction benefits. These advantages make the BWB configuration particularly attractive for both large transport aircraft and UAVs operating in subsonic regimes, where aerodynamic efficiency is a critical determinant of endurance and range.

Over the past two decades, extensive research has been conducted on the aerodynamic shape optimization of BWB and flying-wing configurations using both gradient-based and evolutionary algorithms. Lyu and Martins [1] conducted a series of (Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes) RANS-based shape optimization studies on a Boeing-like BWB configuration, systematically exploring different design variable sets and constraints to achieve minimum drag. Similarly, Mader and Martins [2] extended this analysis to evaluate the effect of static and dynamic stability constraints across subsonic and transonic regimes, highlighting the sensitivity of flying wings to geometric design variables. Keane and Scanlan [3] provided one of the early comprehensive reviews on design search and optimization in aerospace engineering, emphasizing the integration of computational tools with Design of Experiments (DoE) [4] and RSM [5] to improve design convergence efficiency.

Other notable studies have explored CAD-free and CAD-based optimization frameworks [6,7], multi-objective optimization for morphing wings [8,9], and design automation workflows capable of coupling geometry modeling, CFD, and optimization. Kontogiannis and Ekaterinaris [10] developed a parametric design and CFD-based optimization framework for light UAVs, demonstrating that turbulence modeling and geometry fidelity strongly influence the predicted aerodynamic performance. Multi-objective optimization methods for high-lift systems utilizing artificial neural networks (ANNs) and surrogate models have been developed to accelerate aerodynamic prediction and reduce CFD cost [11,12,13]. By integrating metaheuristic algorithms such as genetic, grey-wolf, and mind-evolution strategies, these approaches efficiently navigate complex aerodynamic and structural design spaces. Machine learning and advanced optimization, together, enable more accurate, computationally efficient, and high-performance configurations for next-generation aircraft wings and high-lift devices.

Despite these advances, most existing studies have focused on static geometries and single flight conditions, leaving a significant gap in the systematic aerodynamic design of morphing configurations capable of maintaining performance across multiple Mach numbers. Morphing technologies, where the geometry of the airframe can adapt to varying flight conditions, have been shown to enhance aerodynamic performance, maneuverability, and stability without introducing discrete control surfaces [14,15,16]. Ismail et al. [8] demonstrated improved aerodynamic efficiency in twist-morphing MAV wings using a goal-driven optimization approach within ANSYS, while Sofla et al. [14] reviewed the current challenges of morphing wing implementation, noting that computational optimization remains an indispensable design enabler. However, most reported morphing studies are limited to isolated parameter tuning rather than a generalized, multi-regime optimization framework. Recent active flow-control methods employ low-frequency pulsed jets that strongly interact with natural shear-layer instabilities to reattach separated flow, while high-frequency pulsed jets modify the apparent aerodynamic shape to delay stall and reduce drag on airfoils [17]. On high-lift wings, modulated pulse-jet vortex generators inject periodic vorticity to enhance near-wall momentum and suppress large separation regions, producing significant lift and pressure-recovery improvements without geometric changes.

Flow-separation control works by either energizing the boundary layer or manipulating shear-layer instabilities, through excitation frequency, enabling reattachment, reduced wake size, and improved lift-to-drag performance; low-frequency forcing amplifies large coherent vortices for strong mixing, while high-frequency forcing creates a virtual aerodynamic surface that stabilizes the boundary layer and delays separation. Recent developments, such as burst-modulated pulse jets [18], combine these mechanisms to simultaneously enhance momentum transfer and pressure-gradient control, achieving separation suppression with lower energy input and more stable aerodynamic forces.

A theoretical foundation for aerodynamic design optimization can be traced to Raymer [19] and Torenbeek [20] who introduced the basic design variables as the fundamental parameters governing aircraft performance and geometry which have since been adopted in optimization formulations spanning civil, military, and UAV applications [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The results show that modern aircraft design increasingly relies on multidisciplinary optimization and surrogate-based strategies to handle complex flight environments efficiently, with advances in design-variable formulation, performance evaluation, optimization algorithms, and AI-enabled knowledge extraction greatly improving multidisciplinary design optimization (MDO) efficiency, whereas, structural optimization of BWB configurations using Pultruded Rod Stitched Efficient Unitized Structure (PRSEUS)—inspired modeling and high-accuracy surrogate approaches achieves significant improvements, including an 18.45% mass reduction and a 17.83% increase in natural frequency, demonstrating that integrated optimization frameworks can deliver lighter, stronger, and more efficient next-generation aircraft structures. Recent advancements in MDO have extended these foundations to coupled aero-structural and aero-acoustic problems. Leng et al. [22] and Zhang et al. [23] proposed modern multi-fidelity and Bayesian frameworks to improve convergence efficiency in high-dimensional design spaces, while Tfaily et al. [24] demonstrated the use of hidden-constraint Bayesian optimization for complex aircraft systems. However, such methods are often computationally expensive and challenging to deploy in early conceptual design stages where rapid exploration of aerodynamic sensitivities is essential.

Within this context, surrogate-based optimization methods, particularly RSM and Kriging models, have emerged as powerful tools for aerodynamic design due to their balance between computational efficiency and predictive accuracy [27,28]. RSM-based approaches allow for the construction of smooth functional approximations of aerodynamic responses over multidimensional design spaces, enabling sensitivity analysis and optimization under nonlinear constraints. Combined with parametric CAD modeling and CFD simulation, RSM provides a flexible foundation for automated aerodynamic design frameworks applicable to both conventional and morphing configurations [29,30].

The present study addresses the aforementioned research gap by developing a generalized aerodynamic optimization framework that integrates parametric geometry definition, CFD simulation, and surrogate-based optimization within a single, closed-loop workflow. Unlike previous studies that focus on a specific flight condition or fixed geometry, this work emphasizes the Mach-dependent aerodynamic behavior and geometry sensitivity of morphing BWB UAVs operating across subsonic regimes. The optimization problem is formulated as a drag-minimization problem under constant lift and wetted-area constraints, providing a physically consistent basis for design exploration across multiple flow regimes.

To demonstrate the applicability of the proposed framework, a representative subsonic BWB UAV was analyzed and optimized at Mach numbers 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. The results reveal distinct trends in aerodynamic sensitivities, showing that geometric twist and taper ratio dominate lift generation in incompressible flow, whereas sweep angle becomes increasingly significant as compressibility effects intensify. These findings establish a theoretical and computational foundation for multi-Mach morphing design and provide practical insights for early-stage conceptual development of UAVs and small aircraft.

In contrast to the majority of existing aerodynamic optimization studies, which typically focus on a single design Mach number or assume a fixed aircraft geometry optimized for a specific operating point, the present work explicitly targets multi-regime aerodynamic performance. Previous single-Mach optimization studies yield geometries that are locally optimal but often exhibit degraded efficiency when operated outside the design condition. Similarly, fixed-geometry BWB optimization frameworks do not account for the evolving sensitivity of aerodynamic coefficients to geometric parameters as compressibility effects intensify.

The research gap addressed in this study lies in the absence of a unified, geometry-driven optimization framework that systematically quantifies and exploits Mach-dependent aerodynamic sensitivities for morphing configurations. Rather than introducing a new physical actuation mechanism or modifying governing flow equations, the innovation of the present work resides in the integration of parametric geometry deformation, surrogate-based optimization, and aerodynamic theory into a single scalable framework capable of identifying how and why optimal geometric configurations evolve across flight regimes.

The deformation concept adopted here is therefore conceptual and design-oriented: morphing is realized through continuous variation in geometric parameters such as twist, sweep, taper, and chord scaling within a constrained design space. This enables the aircraft shape to be optimally reconfigured for different Mach regimes without prescribing a specific mechanical implementation, making the framework suitable for early-stage conceptual design and mission-driven trade studies.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical framework for aerodynamic optimization, including problem formulation, surrogate modeling, and Mach-dependent sensitivity theory. Section 3 details the implementation of the proposed framework in a case study of a subsonic morphing BWB UAV. Section 4 discusses the implications of the results in the context of aerodynamic theory and morphing design. Section 5 concludes with key findings and recommendations for future work.

The work introduces a notable advancement by integrating classical aerodynamic principles with modern surrogate-based optimization, demonstrating that morphing geometries can reliably sustain aerodynamic efficiency across varying flight regimes. The resulting framework is both scalable and physically interpretable, offering a meaningful step toward intelligent, high-performance BWB UAVs capable of real-time aerodynamic adaptation. However, the study remains limited by its focus on steady-state aerodynamics, excluding structural, actuation, and high-fidelity physical effects such as transition, shock interactions, and aeroelastic deformation. Practical realization would require incorporating actuator technologies and their mechanical constraints, while experimental validation, especially considering ground-effect influences remain essential. Additionally, the surrogate models may need further refinement with expanded datasets, particularly in nonlinear transonic flow regimes.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodology

The aerodynamic design and optimization of morphing BWB configurations require a unified theoretical foundation that couples geometry parameterization, physical modeling, and numerical optimization [31] within a consistent framework. In this study, a generalized formulation is developed to describe the relationship between geometric design variables and aerodynamic performance across varying Mach regimes. The framework integrates three principal components: (i) aerodynamic design theory, defining the governing geometric and performance parameters based on established aircraft design principles [19,20]; (ii) optimization problem formulation, where the drag-minimization objective is expressed under constant lift and wetted-area constraints to maintain level-flight consistency; and (iii) surrogate-based optimization methodology, employing DoE, RSM, and Kriging interpolation to efficiently approximate nonlinear aerodynamic responses. This section presents the theoretical underpinnings of each component and establishes how they are combined to form a scalable, multi-Mach optimization workflow applicable to both morphing and fixed-geometry UAV configurations.

2.1. Aerodynamic Design Principles for Morphing BWB Configurations

The aerodynamic behavior of a BWB aircraft is governed by the coupled influence of geometry, flight conditions, and flow physics. Establishing a generalized framework for aerodynamic optimization requires identifying and classifying the key geometric and performance parameters that govern lift, drag, and stability. Classical aircraft design theory, as described by Raymer [19] and Torenbeek [20], defines six fundamental parameters of the so-called basic six, namely, wing loading (), thrust-to-weight ratio (), aspect ratio (AR), sweep angle (), thickness-to-chord ratio (), and taper ratio (). Among these, and are performance parameters controlling overall aerodynamic loading, while AR, , , and describe the geometric configuration that shapes aerodynamic flow behavior.

In a morphing BWB UAV, this parameter set is extended with additional geometric degrees of freedom such as geometric twist, local chord scaling, and variable dihedral. These morphing variables enable in-flight shape adaptation, allowing the aircraft to sustain favorable lift-to-drag ratios () and stability margins across multiple Mach regimes. Consequently, the aerodynamic optimization problem becomes nonlinear and multi-regime, where the sensitivity of aerodynamic coefficients to each parameter evolves with Mach number. Previous investigations [8,14,22,23] have demonstrated that when morphing mechanisms are embedded within an optimization process that accounts for flow–geometry coupling, substantial aerodynamic gains can be achieved without compromising stability.

The aerodynamic forces on a morphing BWB can be represented as functions of the geometric design vector, as described in Equation (1) below:

where denotes the geometric-twist distribution along characteristic spanwise stations, and represents dihedral or local-scaling factors. The lift and drag coefficients are expressed in Equation (2) below:

with Mach number , angle of attack , and Reynolds number as flow variables. In incompressible conditions (), viscous drag and surface friction dominate, whereas at higher Mach numbers () compressibility and sweep effects become more pronounced [32,33]. This Mach-dependent shift in aerodynamic sensitivities highlights the need for a multi-Mach optimization framework rather than a single-point design approach.

The aerodynamic analysis in this study is based on the solution of the steady, compressible Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations, which govern the conservation of mass, momentum, and energy for viscous flows. The following assumptions are adopted throughout the study:

- (i)

- Steady-state flow;

- (ii)

- Continuum hypothesis;

- (iii)

- Newtonian fluid behavior;

- (iv)

- Fully turbulent flow;

- (v)

- Negligible body forces.

Under these assumptions, the governing equations can be written in conservative form as

Continuity:

Momentum:

Energy:

where is the fluid density, is the velocity vector, is the static pressure, is the total energy per unit mass, is the temperature, and denotes the viscous stress tensor. Turbulence effects are accounted for through Reynolds averaging and closed using an eddy-viscosity turbulence model.

The computational domain is bounded by a velocity inlet specified by the freestream Mach number, static temperature, and turbulence quantities, and a pressure outlet condition applied at the far-field boundaries. No-slip, adiabatic wall boundary conditions are imposed on all aircraft surfaces. The angle of attack is prescribed by resolving the freestream velocity vector into its components relative to the aircraft reference frame.

This formulation provides a physically consistent basis for evaluating aerodynamic forces and enables systematic comparison of geometry-induced performance variations across multiple Mach regimes. Since the objective of the present work is the development of an integrated aerodynamic optimization framework rather than CFD model development, the governing equations and boundary conditions follow well-established aerospace CFD practices.

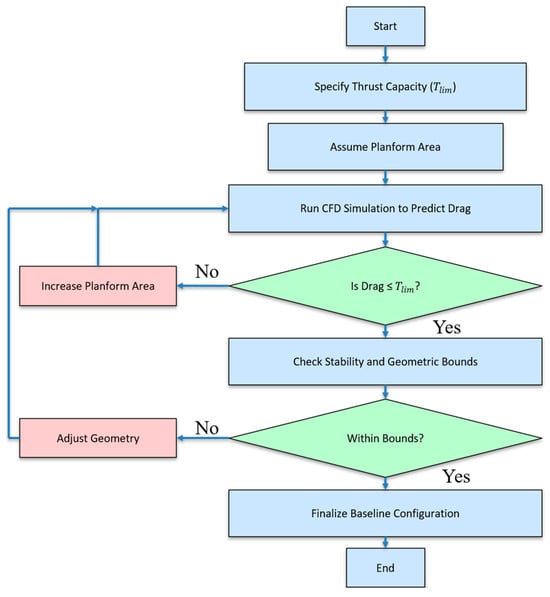

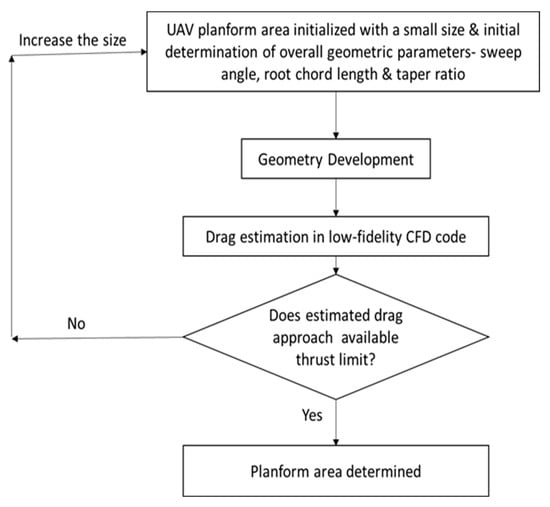

Figure 1 depicts the initial sizing process, which forms the foundation of the conceptual design framework. The flowchart illustrates the iterative determination of planform area, thrust–drag equilibrium, and weight estimation used to establish the baseline geometry prior to optimization.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the initial sizing process for the BWB UAV based on thrust–drag equilibrium.

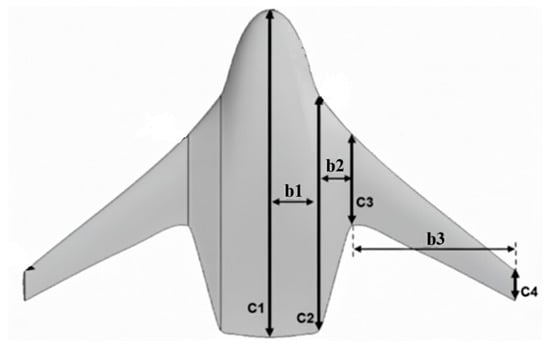

The BWB configuration considered in this framework is divided into four primary airfoil sections denoted as C1, C2, C3, and C4 corresponding to the center body, inboard wing, and outboard wing regions. These stations serve as the reference points for defining local geometric parameters such as chord length, twist angle, and thickness ratio. The planform also includes winglet root and tip stations used to parameterize winglet taper and sweep. The geometric layout of these reference stations is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Definitions of airfoil stations (C1–C4) separated by span lengths (b1–b3) and segregated sections of the BWB UAV planform.

The geometric and performance parameters used in defining the morphing BWB UAV are discussed conceptually here, while their numerical values and corresponding baseline aerodynamic coefficients are presented later in Section 3.1 as part of the case study.

The detailed optimization methodology and the RSM workflow are introduced in the following section.

2.2. Problem Formulation and Optimization Model

The aerodynamic optimization of a morphing BWB UAV is formulated as a constrained nonlinear minimization problem, where the objective is to minimize total drag while maintaining constant lift and wetted area to ensure level-flight consistency. The formulation in Equation (6) accommodates multi-regime operation, enabling the same geometry to be evaluated and optimized at different Mach numbers.

where and are the drag and lift coefficients, is the reference planform area, and represents the lift required for steady level flight. The design vector contains twelve geometric variables defining the UAV’s planform and morphing characteristics. Three key output parameters, namely, drag coefficient (), lift coefficient (), and planform reference area (), are monitored during each CFD evaluation.

The bounds defining the feasible design space are provided in Table 1, ensuring geometric realism and structural plausibility while preserving flexibility for aerodynamic enhancement.

Table 1.

Range of each input geometric parameter defining the design space.

A significant consideration in the choice of an optimization approach in this study is the computational cost of CFD analysis. Due to the complicated CAD geometry of the BWB UAV in this study, a large amount of discretized finite elements may be produced and then readily transferred to RANS CFD solver for obtaining aerodynamic data, including lift and drag coefficients. Such huge amount of data is processed and calculated at an extremely high computational expense. If designers would employ direct & real optimization approaches, such as genetic algorithms, adjoint gradient-based algorithms, etc., it will be a computationally prohibitive computational task for a single workstation to accomplish. Out of the consideration for saving computational cost, the Response Surface Methodology based on Design of Experiments was chosen due to their efficiency and accurate predictions over the optimum output parameters of interest.

The implementation of RSM can be realized in commercial packages ANSYS workbench DesignXplorer Response surface Optimization. ANSYS DesignXplorer (ANSYS® 2024 R2) is a design optimization application that operates under the ANSYS Workbench environment and incorporates both traditional and non-traditional optimization through a goal-driven approach. ANSYS DesignXplorer software provides instantaneous feedback on all proposed design modifications, which dramatically decreases the number of design iterations and improves the overall design process.

The optimization procedure is implemented in two stages:

- DoE sampling employs an Optimal Space-Filling (OSF) scheme coupled with Central Composite Design (CCD) to distribute design points uniformly across the multidimensional space.

- The evaluated data are used to construct a RSM using Kriging interpolation, which provides smooth, differentiable approximations of and .

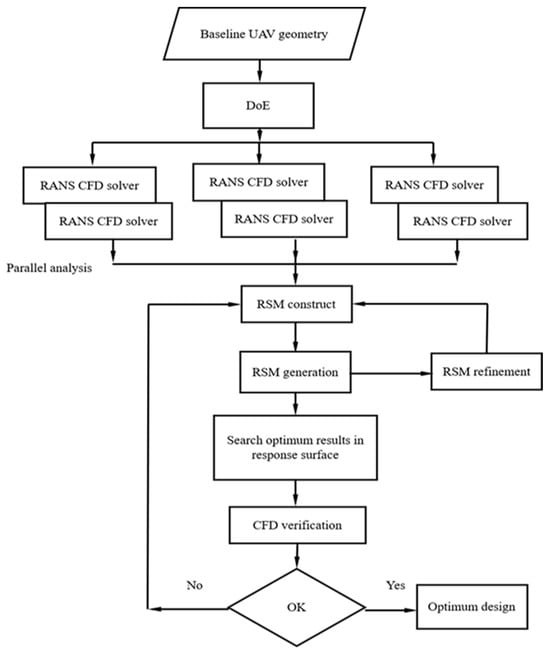

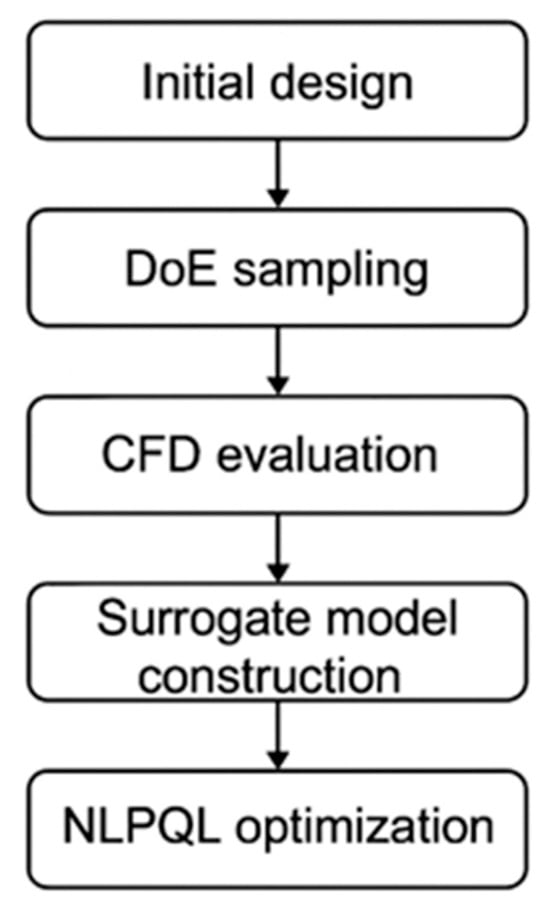

The surrogate-based model is then optimized using a gradient-based Nonlinear Programming by Quadratic Lagrangian (NLPQL) algorithm [34] to identify the minimum-drag configuration satisfying the imposed constraints. The iterative sequence, comprising DoE generation, CFD evaluation, surrogate construction, and optimization, is summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

RSM optimization workflow integrating DoE sampling, Kriging surrogate modeling, CFD evaluation, and NLPQL optimization.

This framework ensures efficient exploration of the aerodynamic design space while capturing nonlinear trends across multiple Mach regimes. The next section extends this methodology to include surrogate-based sensitivity analysis, which quantifies the influence of individual geometric parameters on aerodynamic performance.

The optimization objective (cost function) is defined as the minimization of the drag coefficient, as stated in Equation (7) below:

subject to a constant lift constraint to ensure level-flight consistency. Convergence of the surrogate-based optimization is assumed when successive iterations of the search produce less than 1% variation in both the objective function and constraint values.

The CFD model setup described next defines the computational domain, meshing strategy, and numerical models used to obtain these results.

2.3. Surrogate-Based Aerodynamic Optimization (RSM + Kriging)

The aerodynamic optimization problem formulated in Section 2.2 involves twelve geometric design variables and multiple flow conditions, making direct high-fidelity optimization computationally prohibitive. To efficiently approximate the nonlinear relationships between geometric parameters and aerodynamic responses, a surrogate-based optimization strategy was adopted. The surrogate model acts as a response predictor that replaces repeated CFD evaluations within the optimization loop while preserving the underlying physical trends.

2.3.1. Design of Experiments and Data Generation

The DoE approach provides the data foundation for constructing the surrogate model. An OSF sampling strategy, combined with a CCD algorithm, was used to distribute sampling points uniformly within the multidimensional design space. This ensures that the resulting surrogate captures both global and local nonlinearities without excessive sampling density. Each design point generated by the DoE corresponds to a unique geometric configuration of the BWB UAV, which is parameterized in ANSYS Workbench and evaluated through steady-state CFD simulations to obtain the aerodynamic coefficients , , and the planform reference area .

The aerodynamic coefficients obtained from these simulations serve as the input–output dataset for building the surrogate model. Figure 3 illustrates the overall workflow linking geometry parameterization, DoE generation, CFD evaluation, surrogate construction, and optimization convergence. This schematic provides the structural overview of the surrogate-based optimization process discussed here.

The complete Design of Experiments datasets, including all geometric input parameters and corresponding CFD-derived aerodynamic coefficients for Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8, are provided in the Supplementary Material.

2.3.2. Construction of the Surrogate Model

The surrogate model employed in this study is based on the Kriging interpolation technique [28], which provides an exact fit at sampled points while estimating local prediction uncertainty. In this method, each aerodynamic response (e.g., or ) is expressed in Equation (8) as:

where is the global mean of the response and is a stochastic process with zero mean and specified spatial correlation. The correlation between two design points and is defined in Equation (9) as:

where and are correlation parameters estimated by maximum-likelihood optimization. This formulation allows Kriging to accurately reproduce nonlinear aerodynamic trends while remaining computationally efficient.

Once the surrogate surface is constructed, its fidelity is verified by comparing predicted and CFD-computed coefficients at randomly selected points not used in the training dataset. The validation criterion is satisfied when the normalized prediction error for both and remains below 5%.

2.3.3. Optimization Search and Convergence

The surrogate-based optimization employed a Kriging response surface constructed from Design of Experiments samples generated using an optimal space-filling strategy combined with a Central Composite Design. Optimization over the surrogate design space was performed using the Nonlinear Programming by Quadratic Lagrangian (NLPQL) algorithm [34], which applies a sequential quadratic programming approach to efficiently handle nonlinear constraints. Convergence was declared when successive iterations resulted in less than 1% variation in the predicted lift and drag coefficients. The final optimal configuration was subsequently re-evaluated using high-fidelity CFD to verify the accuracy of the surrogate predictions.

Since the aerodynamic coefficients were obtained from deterministic CFD simulations rather than stochastic experiments, classical statistical confidence intervals are not directly applicable. Instead, an equivalent uncertainty bound was estimated based on surrogate model prediction error. The 95% confidence bounds for the lift and drag coefficients were approximated using ±1.96 times the standard deviation of the surrogate prediction residuals evaluated at independent verification points. Based on this assessment, the resulting uncertainty in both and remained within ±3–5% of the corresponding mean values across all Mach numbers.

2.3.4. Sensitivity Analysis

To quantify the influence of each geometric parameter on aerodynamic performance, a local sensitivity analysis is performed using the fitted response surfaces. The sensitivity intensity of the design variable is computed as the normalized partial derivative of the response function, as described in Equation (10) as:

and similarly for . Positive values of indicate a direct (positive) correlation between the design variable and the response, whereas negative values represent inverse relationships.

Sensitivity plots generated for each Mach number (see Section 3) highlight the relative importance of parameters such as geometric twist, taper ratio, and sweep angle in governing aerodynamic behavior. These analyses provide physical insight into how each variable contributes to the overall optimization objective and guide subsequent morphing design adjustments.

2.3.5. Surrogate Model Accuracy and Sampling Strategy

The accuracy of the surrogate models was assessed using standard statistical indicators, including the coefficient of determination (R2), mean absolute error (MAE), and root mean square error (RMSE), computed by comparing surrogate predictions against CFD results at verification points not included in the training dataset. For all Mach numbers considered, the surrogate models exhibited high predictive fidelity, with R2 values exceeding 0.98 for both lift and drag coefficients and normalized RMSE values below 5%.

A total of 50 Design of Experiments samples were generated for each Mach number using an optimal space-filling strategy combined with Central Composite Design. This sample size represents a balance between computational cost and surrogate accuracy and is consistent with established best practices for Kriging-based surrogate modeling in aerodynamic optimization involving high-dimensional but smooth response spaces. Increasing the number of samples beyond this level did not produce a meaningful improvement in surrogate accuracy relative to the associated computational expense.

A formal statistical power analysis was not performed, as the CFD simulations are deterministic rather than stochastic in nature. Instead, surrogate adequacy was established through cross-validation and verification against independent CFD evaluations.

2.4. Mach-Dependent Aerodynamic Sensitivities and Theoretical Trends

The aerodynamic response of a BWB configuration is highly sensitive to variations in Mach number due to changes in flow compressibility, shock-wave formation, and boundary-layer behavior. Understanding these Mach-dependent trends is essential for interpreting optimization results and identifying which geometric parameters should be prioritized for morphing. This section presents the theoretical basis for these sensitivities, linking classical aerodynamic principles with the parametric variables defined in Section 2.1, Section 2.2 and Section 2.3.

At low subsonic speeds (), the flow is nearly incompressible, and aerodynamic forces are primarily governed by viscous, and pressure drag components. In this regime, lift is approximately linear with the effective angle of attack and is highly responsive to geometric twist and taper ratio. The lift coefficient may be approximated using thin-airfoil theory, described in Equation (11) as:

where is the freestream angle of attack, is the local twist distribution along the span, and is the aspect ratio. This relationship highlights the proportional influence of twist on the lift curve slope. At these Mach numbers, geometric changes primarily affect the induced drag component, while pressure drag remains relatively insensitive to shape variation. Therefore, the aerodynamic optimization in incompressible flow focuses on achieving favorable spanwise load distribution through controlled twist and taper.

As the Mach number increases (), compressibility effects begin to modify the pressure field, increasing both lift and drag through localized density variations. The Prandtl–Glauert relation in Equation (12) describes the amplification of aerodynamic coefficients in this range as:

where is the incompressible lift coefficient. Here, parameters such as sweep angle () and chord scaling become increasingly significant, as they influence the pressure recovery along the surface. An increase in sweep angle delays compressibility effects by reducing the normal Mach number component, thereby mitigating wave drag formation while simultaneously reducing lift due to decreased normal velocity components.

At higher subsonic to near-transonic speeds (), flow separation, shock-induced pressure gradients, and local transonic pockets dominate the aerodynamic response. In this regime, sweep angle exerts the strongest control over both lift and drag characteristics. The normal Mach number acting on the wing’s leading edge is expressed in Equation (13) as:

where is the freestream Mach number. Increasing reduces , thereby delaying the onset of wave drag and shock formation; however, it also reduces the effective lift curve slope. This trade-off underscores the importance of morphing geometries that can dynamically adjust sweep or twist to maintain aerodynamic efficiency across multiple Mach regimes.

The expected relative sensitivities of lift and drag to major geometric parameters are summarized in Table 2. These qualitative estimates serve as theoretical benchmarks for interpreting the numerical results in Section 3.

Table 2.

Theoretical trends in relative sensitivity of lift and drag to geometric parameters across subsonic Mach regimes.

The observed shift from twist- and taper-dominated behavior at low Mach to sweep-and chord-sensitive behavior at higher Mach numbers provides a physical rationale for adopting a multi-Mach optimization strategy. This theoretical foundation enables the systematic interpretation of the optimization outcomes discussed later in Section 3.

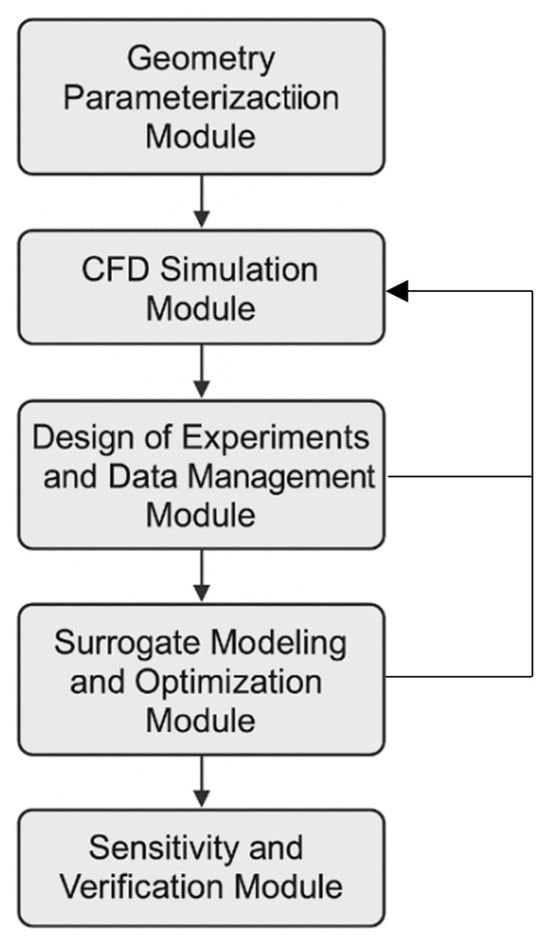

2.5. Framework Architecture and Implementation Workflow

The methodology developed in the preceding sections is consolidated into a generalized aerodynamic design and optimization framework suitable for both fixed-geometry and morphing UAVs. The framework integrates geometry parameterization, high-fidelity CFD simulation, surrogate-based modeling, and optimization into a closed-loop workflow. Its modular architecture ensures scalability across multiple Mach regimes and facilitates straightforward extension to multidisciplinary design problems.

Figure 4 presents the overall implementation architecture of the framework, highlighting the logical flow between its five functional modules:

Figure 4.

Architecture of the integrated aerodynamic design and optimization framework for morphing BWB UAVs, illustrating data flow between geometry definition, CFD evaluation, surrogate construction, optimization, and sensitivity verification modules.

- Geometry Parameterization Module: Defines the BWB geometry using parametric CAD models that incorporate both classical design parameters (aspect ratio, sweep, taper, and thickness-to-chord ratio) and morphing variables (twist, chord scaling, and dihedral). This ensures flexible control of local and global aerodynamic features.

- CFD Simulation Module: Evaluates aerodynamic performance for each generated geometry using Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes (RANS) equations within the ANSYS Fluent solver. The module calculates the lift, drag, and pressure distributions required to characterize aerodynamic efficiency at multiple Mach numbers.

- DoE and Data Management Module: Generates the design sample matrix using OSF and CCD techniques, ensuring even coverage of the design space while minimizing computational cost. The database stores corresponding CFD outputs for surrogate modeling.

- Surrogate Modeling and Optimization Module: Constructs Kriging-based response surfaces from the DoE data and employs the Nonlinear Programming by Quadratic Lagrangian (NLPQL) algorithm to minimize drag under constant lift and area constraints. This module serves as the computational core of the optimization process, allowing efficient multi-Mach evaluations.

- Sensitivity and Verification Module: Performs sensitivity analysis using response-surface derivatives to quantify the relative influence of each design variable on and . The optimal configuration predicted by the surrogate model is then validated through high-fidelity CFD simulations to ensure physical consistency and numerical accuracy.

The framework is implemented within the ANSYS Workbench environment using Python-based parametric linking scripts that automate geometry generation, CFD execution, and result extraction. This automation minimizes user intervention and enhances repeatability, making the workflow suitable for conceptual design studies and iterative performance evaluations.

Moreover, the framework architecture is inherently modular, individual components such as the surrogate model or optimizer can be replaced or upgraded without restructuring the entire system. This flexibility allows future integration with additional physics domains, including structural deformation, aeroelastic coupling, and acoustic performance, enabling a fully coupled design optimization framework.

The following section applies this framework to a representative subsonic BWB UAV to demonstrate its predictive capabilities and validate the Mach-dependent aerodynamic trends discussed in Section 2.

3. Case Study: Application to a Subsonic Morphing BWB UAV

The Mach numbers 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 were selected to represent distinct and practically relevant operating regimes for subsonic UAVs, corresponding, respectively, to low-speed loiter or endurance flight, moderate-speed cruise, and high-subsonic dash or rapid transit conditions. The upper bound of Mach 0.8 was intentionally selected to remain within the subsonic regime and to avoid transonic flow phenomena, such as shock-induced separation and strong nonlinear wave drag effects, which are outside the scope of the present steady-state aerodynamic framework and would require higher-fidelity modeling and additional physical considerations.

To validate the proposed aerodynamic design and optimization framework, a representative subsonic BWB UAV is analyzed in this section. The case study demonstrates the practical implementation of the theoretical methodology presented in Section 2, emphasizing its ability to capture Mach-dependent aerodynamic sensitivities and guide geometry-based optimization across multiple flight regimes.

The selected UAV serves as a benchmark for comparing baseline aerodynamic performance with optimized configurations at three subsonic Mach numbers (0.2, 0.4, and 0.8). The analysis encompasses initial sizing, CFD model setup and validation, optimization configuration, and sensitivity interpretation. Through this systematic evaluation, the case study verifies the predictive accuracy of the surrogate model, illustrates the evolution of aerodynamic performance with Mach number, and highlights the effectiveness of morphing geometry for maintaining aerodynamic efficiency across subsonic flight conditions.

3.1. Baseline Configuration and Initial Sizing

The initial sizing of the BWB UAV establishes the baseline configuration used as a reference throughout the optimization process. The primary objective of this step is to determine the appropriate planform dimensions and geometric proportions that satisfy the thrust–drag equilibrium under steady level-flight conditions. This ensures that the configuration is aerodynamically feasible within the propulsion limits of an electric ducted-fan system typically used in subscale UAVs.

The design procedure follows an iterative approach in which the total drag produced during cruise flight must not exceed the available engine thrust at the chosen cruise Mach number of 0.2. The baseline sizing begins with a small initial planform area and incrementally increases it until the equilibrium condition is achieved, as shown in Equation (14):

where is the available thrust and is the computed drag. This procedure, illustrated schematically in Figure 5, ensures that the aerodynamic sizing remains consistent with propulsion constraints.

Figure 5.

Implementation of the thrust–drag equilibrium initial sizing framework for the BWB UAV case study.

At low subsonic conditions (), the total drag is predominantly governed by the wetted area, and the viscous skin-friction drag. Consequently, the initial planform area is chosen such that the total aerodynamic drag remains below the maximum available thrust of approximately 100 N for the selected electric ducted-fan propulsion system. The iterative process also accounts for lower size limits imposed by flight stability requirements, as overly compact configurations may exhibit insufficient inertia and poor dynamic stability characteristics.

The finalized baseline planform geometry features a total area of 2.877 m2, with a span of 4.206 m, and is subdivided into three major wing sections and winglets. The geometric characteristics of this configuration are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Geometric data of the baseline BWB UAV configuration.

The BWB configuration is geometrically divided into four primary airfoil sections, C1 through C4, representing the center body, inboard, and outboard wing regions. Each section employs a specific airfoil selection from the NACA 6-series family: NACA 64(3)-218 at the center body (C1–C2), NACA 64(2)-215 for the wing segments (C3–C4), and NACA 0015 for the winglets. This layout is shown in Figure 2, which defines the reference stations used in the aerodynamic parameterization and optimization process.

Once the baseline geometry was finalized, preliminary CFD simulations were performed to estimate the aerodynamic coefficients at the reference cruise condition (, ). The results, summarized in Table 4, confirm that the lift-to-drag ratio () satisfies the thrust equilibrium requirement and validates the feasibility of the selected planform.

Table 4.

Baseline aerodynamic performance from preliminary CFD analysis at Mach 0.2.

The results indicate that the baseline design provides a stable aerodynamic foundation for further optimization. The following sections present the CFD setup, verification procedures, and the implementation of the optimization framework for this reference configuration across multiple Mach regimes.

3.2. CFD Model Setup and Verification

CFD simulations were conducted in ANSYS Fluent within the ANSYS Workbench environment. Steady three-dimensional compressible RANS equations were solved using a pressure-based solver with second-order spatial discretization for all variables. Pressure–velocity coupling was achieved using the SIMPLE algorithm. Convergence was declared when scaled residuals fell below 10−5 and aerodynamic coefficients showed negligible change with further iterations.

A hybrid mesh was employed, with unstructured tetrahedral elements in the far field and structured prism layers near the walls to resolve the boundary layer. The near-wall mesh was designed to achieve y+ ≈ 1, enabling low-Reynolds-number wall treatment. Grid-independence studies confirmed that variations in lift and drag coefficients remained within acceptable limits.

The validated high-fidelity CFD model was used to evaluate the aerodynamic performance of the baseline BWB configuration across multiple Mach numbers and to ensure numerical accuracy prior to optimization.

Numerical noise in the CFD solutions was minimized by maintaining consistent mesh topology, boundary layer resolution, solver settings, and convergence criteria across all simulations. All CFD runs were performed on fixed meshes for each geometry realization, and aerodynamic coefficients were extracted only after residual convergence and stabilization of force histories. As a result, variations in lift and drag coefficients are attributable to geometric changes rather than numerical noise.

Mesh quality was monitored using standard metrics including skewness and orthogonality. For all computational grids, the maximum cell skewness remained below commonly accepted thresholds for unstructured CFD meshes, and no numerical instability attributable to mesh quality was observed across the simulated Mach regimes.

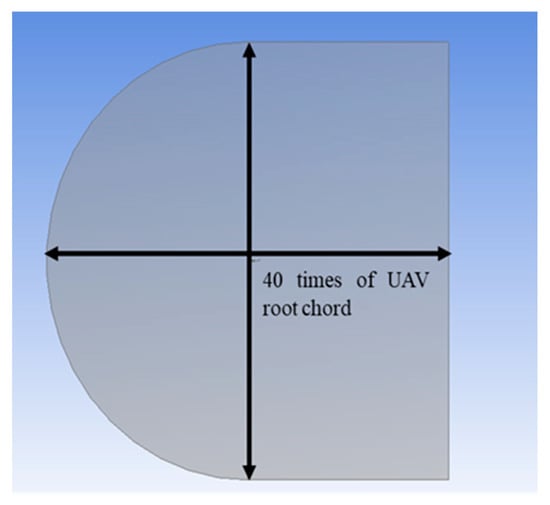

3.2.1. Computational Domain and Boundary Conditions

The computational domain was constructed to minimize boundary interference effects on the flow around the BWB model. Following standard aerodynamic practices, the domain extended approximately 40 times the root chord length in all directions from the aircraft geometry. The domain geometry, shown in Figure 6, consists of a quarter-sphere at the inlet and a semi-cylindrical section at the outlet, ensuring smooth flow development and minimizing numerical reflections at the boundaries.

Figure 6.

Computational domain for the CFD simulation of the BWB UAV, showing the hemispherical inlet and cylindrical outlet regions.

At the inlet boundary, a uniform velocity profile corresponding to the target Mach number was imposed, while the outlet was defined as a pressure far-field condition. The BWB surface was treated as a no-slip adiabatic wall, and the far-field boundaries were modeled as slip walls. The freestream conditions were defined at an altitude of 500 m, with air density and viscosity corresponding to the International Standard Atmosphere (ISA) model.

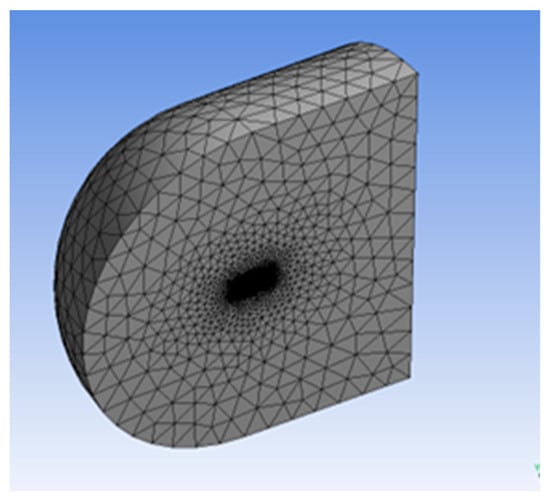

3.2.2. Mesh Generation and Grid Independence Study

The computational domain was discretized using an unstructured tetrahedral mesh with prism layers in the near-wall region to accurately capture the viscous sublayer effects. Special attention was given to mesh refinement along the leading and trailing edges, where flow gradients are most pronounced. The global mesh topology is illustrated in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Global view of the unstructured tetrahedral mesh used for the CFD simulation of the BWB UAV.

To ensure numerical reliability, a grid independence study was performed at Mach 0.4, where both lift and drag coefficients were monitored for different mesh densities. Five mesh refinement levels were tested, ranging from approximately 0.45 million to 2.75 million elements. The results are summarized in Table 5. As shown, the lift coefficient stabilized beyond the third refinement level, and variations in drag coefficient between the third and fourth grids were below 2%. Consequently, the Refinement 2 mesh (approximately 1.23 million elements) was selected for all subsequent simulations as it offered the best compromise between accuracy and computational cost.

Table 5.

Grid independence verification for CFD simulations at Mach 0.4.

3.2.3. Turbulence Model Selection

The turbulence model can be categorized based on the number of equations required to evaluate turbulence viscosity. Each turbulence model has pros and cons. Due to the outstanding computational efficiency, the character of quick divergence and non-inferior solution accuracy compared to extensively used two-equation turbulence models, the one equation Spalart–Allmaras model is utilized. To accurately model the aerodynamic flow behavior while maintaining computational efficiency, the Spalart–Allmaras (S–A) one-equation turbulence model was employed. This model has been extensively validated for low- to moderate-Mach-number external aerodynamics and is particularly effective for flows dominated by attached boundary layers. The compressibility effects at higher Mach numbers were accounted for using the standard compressibility correction available in ANSYS Fluent.

The selection of the S–A model was based on a comparative assessment of different two-equation models (such as SST and realizable). The S–A model provided faster convergence, stable residual behavior, and good agreement with theoretical aerodynamic coefficients, making it suitable for iterative optimization runs. The key flow parameters and turbulence model settings are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Flow and turbulence model parameters for CFD simulations of the BWB UAV.

3.2.4. Verification of CFD Results

The CFD results obtained using the selected mesh and turbulence model were verified through consistency checks. The lift and drag coefficients showed stable convergence with less than 0.5% residual variation after 2000 iterations for all Mach cases. Furthermore, the pressure and velocity contours along the mid-span cross-sections exhibited physically consistent patterns with no numerical oscillations.

These verified CFD results form the foundation for the subsequent optimization and sensitivity analysis presented in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, ensuring that all derived aerodynamic coefficients are based on numerically robust simulations.

3.3. Optimization Setup and Design Space

The aerodynamic optimization of the BWB UAV was implemented through the integrated CAD–CFD–optimization framework introduced in Section 2.5. This framework couples parametric geometry definition in ANSYS Workbench with steady-state CFD simulations and surrogate-based optimization. The primary objective is to minimize the drag coefficient () while maintaining constant lift () and constant planform area () for three subsonic Mach numbers (0.2, 0.4, and 0.8). This procedure quantifies how geometric variations influence aerodynamic performance across different flow regimes.

3.3.1. Optimization Framework and Variables

The parametric optimization workflow links the geometric model, meshing system, CFD solver, and optimization engine within ANSYS Workbench. Each design iteration automatically updates the geometric parameters, regenerates the mesh, and computes the aerodynamic coefficients, which are then used to train the surrogate model.

The optimization employs twelve independent geometric design variables. Together, they constitute the design vector used in the surrogate-based optimization. These variables are selected to capture both global and local geometric effects influencing lift-to-drag performance:

- Half span: controls overall aspect ratio and influences induced drag.

- Twist angles at C2–C4: modify effective incidence distribution, directly affecting lift generation and pitching-moment balance.

- Sweep angle: reduces effective Mach number normal to the leading edge, mitigating compressibility effects at higher Mach numbers.

- Chord-scaling and taper ratios: alter planform area distribution, affecting pressure recovery and induced drag.

- Winglet scaling and taper ratios: govern tip-vortex strength and total drag contribution.

- Dihedral 1 and 2: influence lateral stability and crossflow characteristics.

These parameters collectively describe the morphing geometry capability of the BWB UAV. Their spatial reference stations (C1–C4) correspond to those illustrated in Figure 2. During the optimization, the twelve parameters are varied simultaneously within their prescribed bounds (Table 1) to determine configurations that achieve minimum drag under constant-lift constraints.

3.3.2. Output Parameters and Objective Function

Each CFD run produces three primary output parameters that describe the aerodynamic response: lift coefficient (), drag coefficient (), and planform reference area (). These serve as the response quantities for constructing the surrogate models and applying optimization constraints.

The optimization follows the formulation presented in Section 2.2, where is minimized subject to constant-lift and constant-area constraints. For clarity, Equation (15) states:

with the theoretical justification and derivation detailed previously.

3.3.3. Design Space and Sampling Strategy

The feasible design space for the twelve variables was established from aerodynamic, structural, and manufacturability considerations. The corresponding bounds have already been defined in Table 1 (Section 2.2) and are reused here for the case-study optimization. These limits ensure realistic morphing amplitudes and prevent aerodynamic or structural divergence.

To explore the design space efficiently, a DoE approach was implemented using an OSF algorithm coupled with a CCD layout. Approximately 50 CFD simulations were performed for each Mach number, generating the dataset for Kriging-based surrogate modeling and subsequent optimization.

3.3.4. Multi-Mach Optimization Procedure

Each Mach case was optimized independently to capture distinct flow-regime sensitivities. The optimization cycle, DoE sampling, CFD evaluation, surrogate modeling, and NLPQL optimization, was repeated for Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. The process is summarized schematically in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of the multi-Mach aerodynamic optimization process showing sequential execution for Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8.

This systematic approach ensures that the optimal designs derived for each Mach regime are physically consistent and computationally validated, providing the foundation for the comparative analysis presented in Section 3.4.

3.4. Multi-Mach Optimization Results (Mach 0.2, 0.4, 0.8)

The optimization results for the BWB UAV at Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 are presented in this section. Each case corresponds to a distinct aerodynamic regime: (i) incompressible low-speed flow (Mach 0.2), (ii) transitional subsonic flow (Mach 0.4), and (iii) near-transonic flow (Mach 0.8). The results demonstrate how the aerodynamic sensitivities and optimal geometry evolve with increasing compressibility and how the morphing configuration adapts to maintain aerodynamic efficiency across these regimes.

3.4.1. Case 1—Mach 0.2, h = 500 m

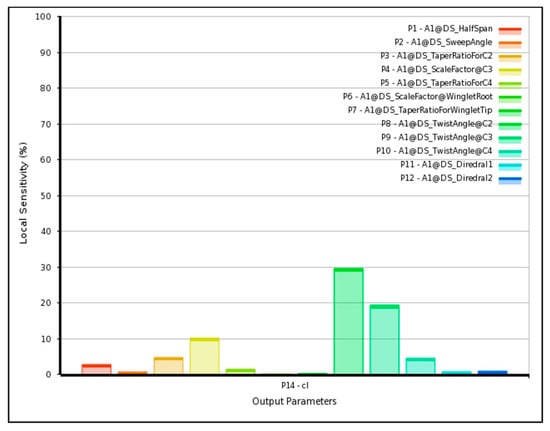

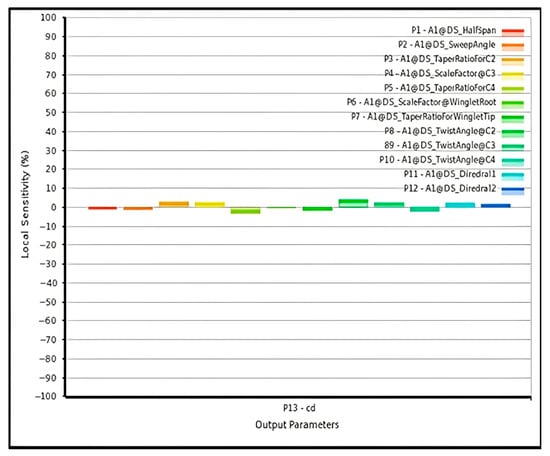

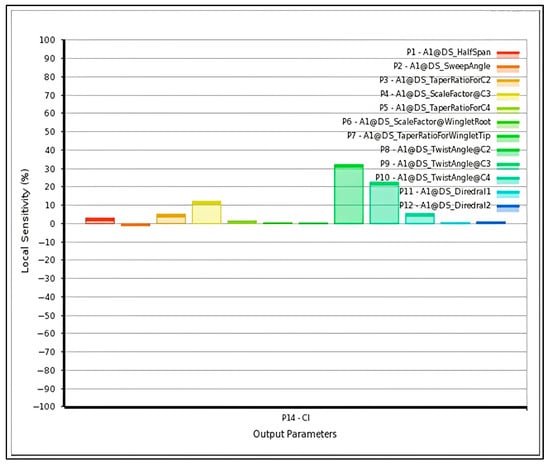

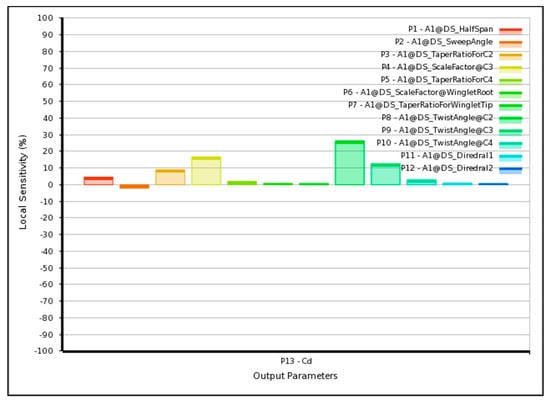

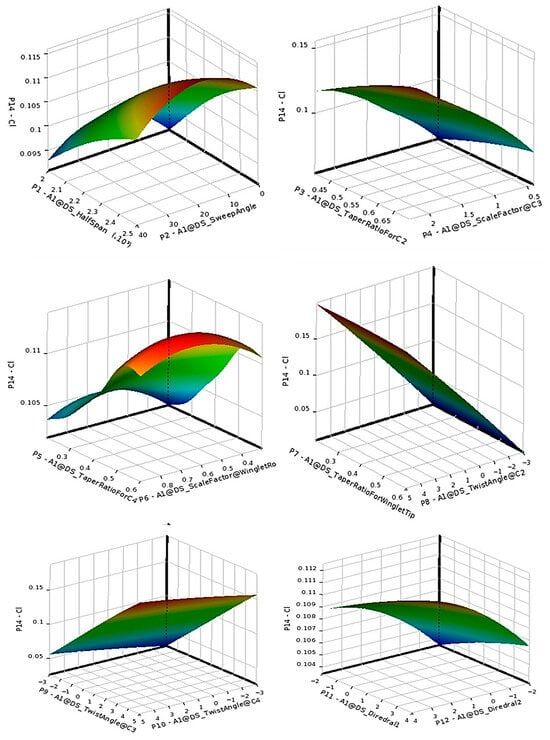

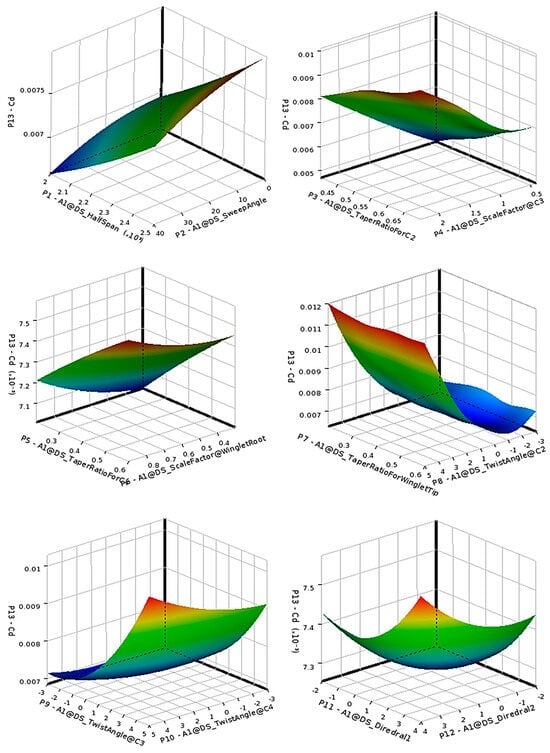

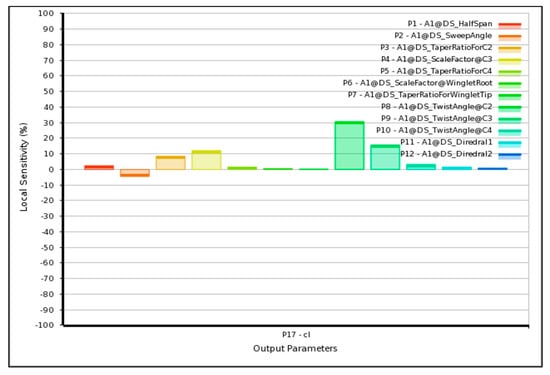

At Mach 0.2, the flow can be treated as incompressible; viscous and induced drag dominate. The sensitivity analysis of lift and drag coefficients with respect to the twelve design variables is shown in Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Sensitivity intensity of lift coefficient with respect to the twelve design variables (Mach 0.2).

Figure 10.

Sensitivity intensity of drag coefficient with respect to the twelve design variables (Mach 0.2).

The lift coefficient exhibits high sensitivity to the three twist angles () and moderate dependence on taper ratio and chord scaling. Drag, however, shows only marginal sensitivity to most variables, indicating that aerodynamic improvements through geometry modification are limited in this low-Mach regime. Increasing wingspan and sweep angle slightly reduces , consistent with classical incompressible-flow theory.

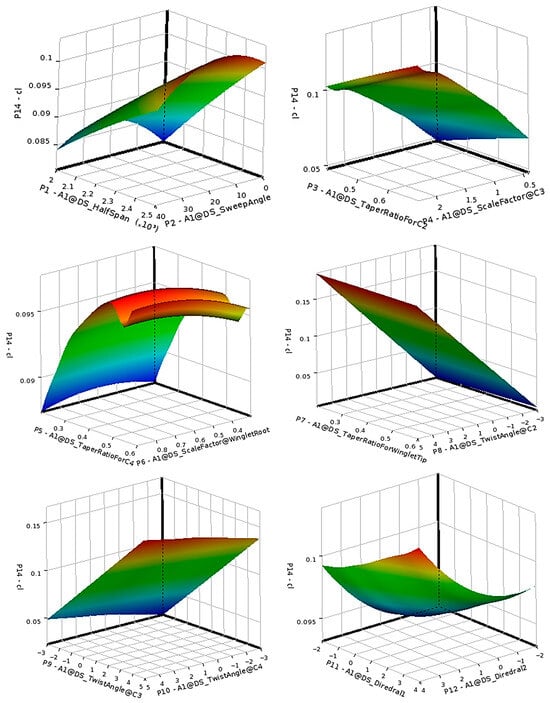

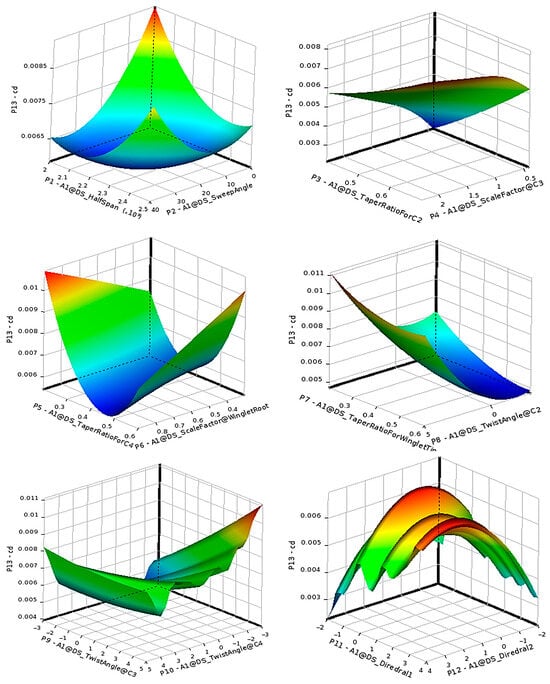

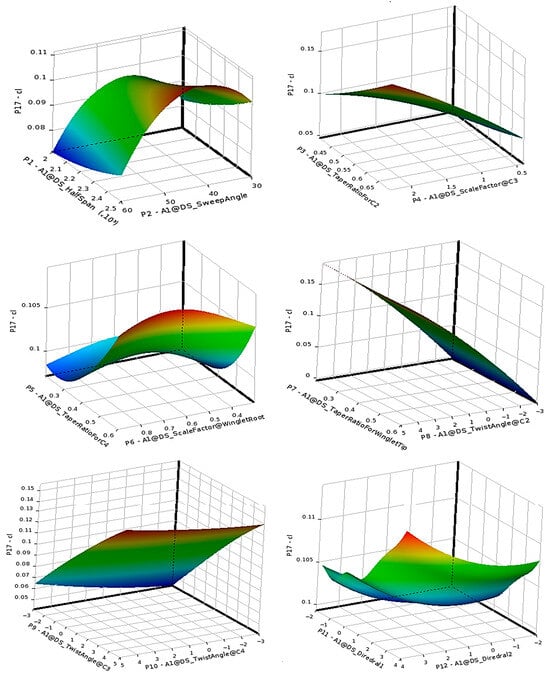

The surrogate-model response surfaces for lift and drag coefficients are shown in Figure 11 and Figure 12, respectively. The nearly linear variation in lift with twist angles reflects thin-airfoil behavior, while drag variation is irregular due to dominance of viscous effects.

Figure 11.

Response surface of lift coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.2).

Figure 12.

Response surface of drag coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.2).

The optimizer-proposed and CFD-verified results for the optimal configuration are listed in Table 7 and Table 8. The optimized design achieves roughly 48% reduction in drag relative to the baseline configuration but introduces minor discrepancies between surrogate predictions and CFD verification, primarily in , due to weak coupling between drag and lift at low Mach numbers.

Table 7.

Design candidate proposed by the optimizer (Mach 0.2).

Table 8.

Discrepancy between proposed and verified results for Mach 0.2.

A comparative analysis between the optimal design and peer designs (those yielding similar values) is presented in Table 9. The optimal configuration provides up to 12% drag reduction over peer designs with comparable lift.

Table 9.

Comparison of optimal design and peer designs at Mach 0.2.

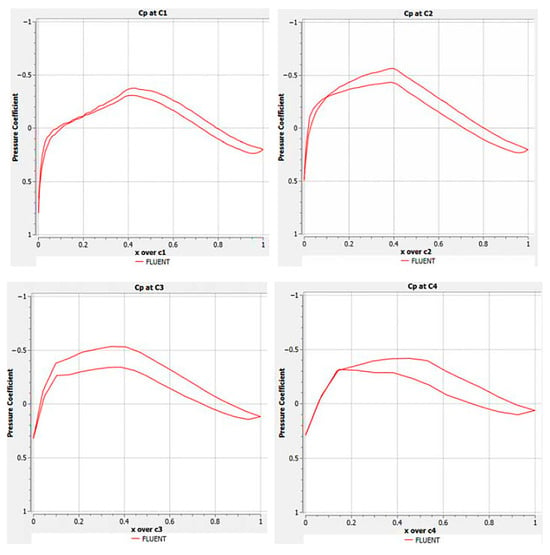

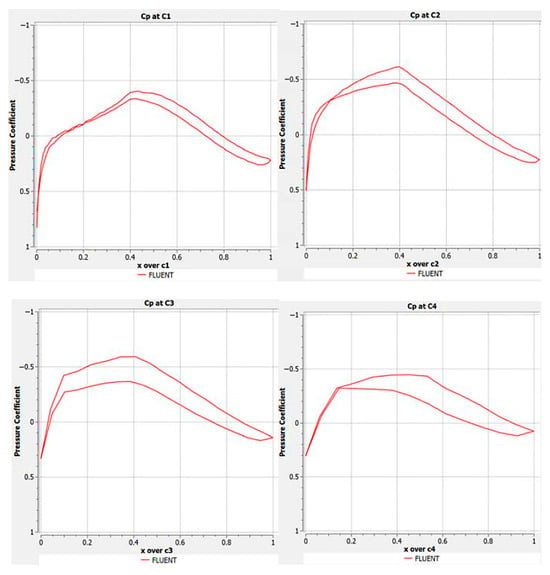

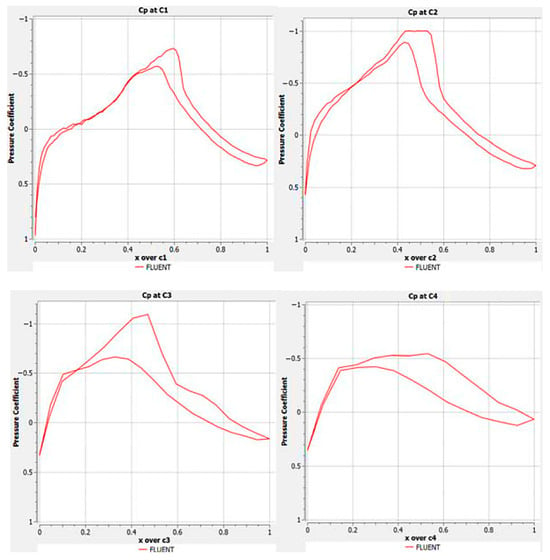

The pressure coefficient distributions at C1, C2, C3 and C4 stations is shown in Figure 13 below.

Figure 13.

Pressure coefficient distribution at C1, C2, C3 and C4 stations at Mach 0.2.

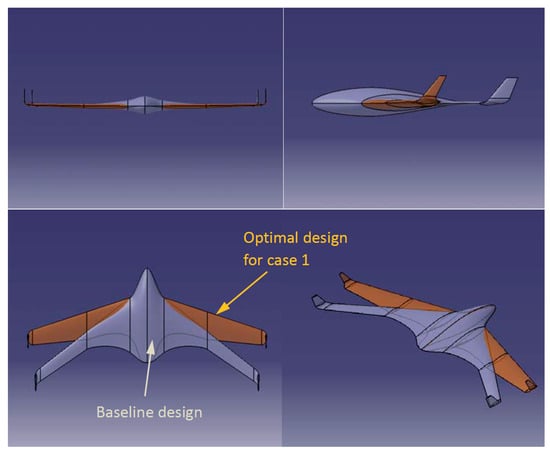

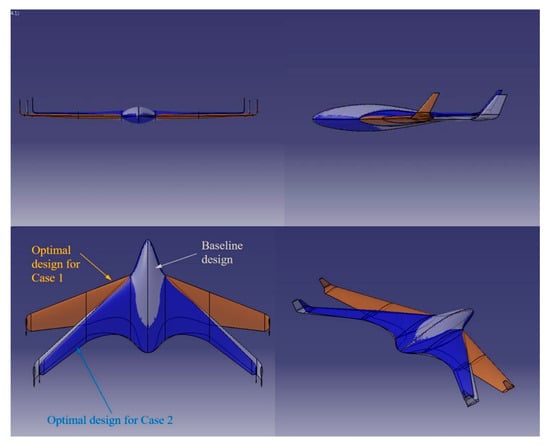

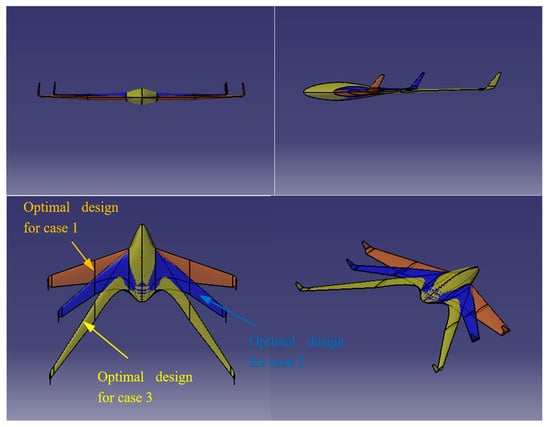

The geometric morphing from the baseline to the optimized configuration for Mach 0.2 is visualized in Figure 14, showing increased span and moderate twist redistribution to achieve the improved ratio.

Figure 14.

Geometry morphing of the BWB UAV from baseline to the optimal design (Mach 0.2).

3.4.2. Case 2—Mach 0.4, h = 500 m

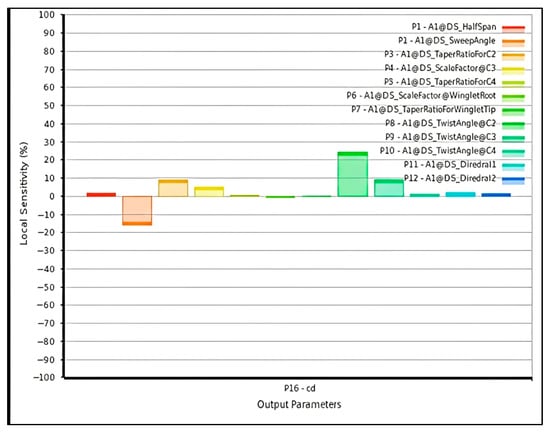

At Mach 0.4, compressibility effects become more pronounced, and both lift and drag show greater sensitivity to geometric changes. The corresponding sensitivity distributions are shown in Figure 15 and Figure 16.

Figure 15.

Sensitivity intensity of lift coefficient with respect to twelve input parameters (Mach 0.4).

Figure 16.

Sensitivity intensity of drag coefficient with respect to twelve input parameters (Mach 0.4).

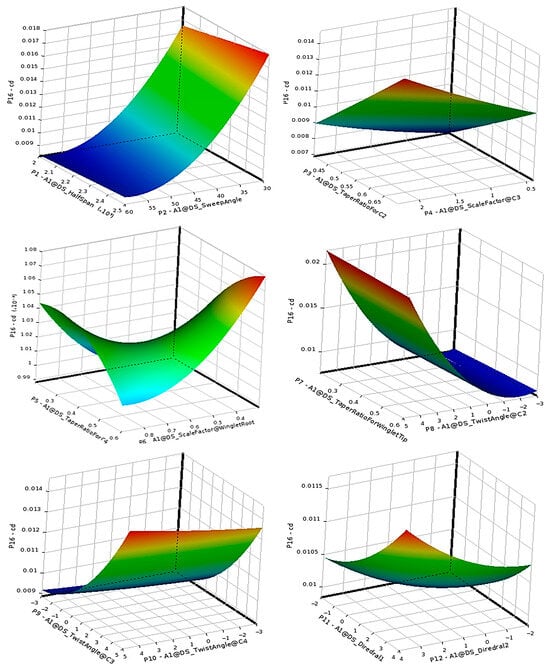

Compared with Case 1, drag becomes notably more sensitive to sweep and twist angles, confirming that compressibility begins to influence pressure drag. Lift still varies primarily with twist, but a minor negative correlation with sweep is now evident. The surrogate-based response surfaces for and are shown in Figure 17 and Figure 18, illustrating smoother and more predictable functional behavior compared with the Mach 0.2 case.

Figure 17.

Response surface of lift coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.4).

Figure 18.

Response surface of drag coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.4).

The optimizer-predicted and verified results are given in Table 10 and Table 11, confirming close agreement between surrogate and CFD data (<10% error). The optimized configuration achieves up to 25% drag reduction compared to peer designs (Table 12).

Table 10.

Design candidate proposed by optimizer (Mach 0.4).

Table 11.

Discrepancy between proposed and verified results for Mach 0.4.

Table 12.

Comparison of optimal design and peer designs at Mach 0.4.

The pressure coefficient distributions at C1, C2, C3 and C4 stations is illustrated in Figure 19 below.

Figure 19.

Pressure coefficient distribution at C1, C2, C3 and C4 stations at Mach 0.4.

The morphing geometry transition between the baseline, Mach 0.2, and Mach 0.4 optimal configurations is shown in Figure 20. The optimized Mach 0.4 shape features a reduced sweep angle and minor chord redistribution compared to the baseline, consistent with the increased drag sensitivity to planform geometry.

Figure 20.

Morphing transition of the BWB UAV from baseline to optimal geometries for Mach 0.2 and Mach 0.4.

3.4.3. Case 3—Mach 0.8, h = 500 m

At Mach 0.8, the flow enters the near-transonic regime, where compressibility effects dominate. Shock formation and pressure gradients significantly alter aerodynamic behavior. The sensitivity analysis results, shown in Figure 21 and Figure 22, confirm that both lift and drag become strongly dependent on sweep angle and chord scaling at the junction of inboard and outboard wing sections.

Figure 21.

Sensitivity intensity of lift coefficient with respect to twelve input parameters (Mach 0.8).

Figure 22.

Sensitivity intensity of drag coefficient with respect to twelve input parameters (Mach 0.8).

The Kriging-based response surfaces, illustrated in Figure 23 and Figure 24, display nonlinear variations of and with geometric parameters, highlighting the complex aerodynamic coupling near transonic speeds.

Figure 23.

Response surface of lift coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.8).

Figure 24.

Response surface of drag coefficient over the twelve input geometric parameters (Mach 0.8).

The optimal design parameters and verification results are summarized in Table 13 and Table 14, while comparative results among peer designs are listed in Table 15. The optimized configuration achieves up to 55% drag reduction relative to peers, primarily through increased sweep and refined taper ratios.

Table 13.

Design candidate proposed by optimizer (Mach 0.8).

Table 14.

Discrepancy between proposed and verified results for Mach 0.8.

Table 15.

Comparison of optimal design and peer designs at Mach 0.8.

The pressure coefficient distributions at C1, C2, C3 and C4 stations is depicted in Figure 25 below.

Figure 25.

Pressure coefficient contour over the whole UAV at Mach 0.8.

The morphing transition of the BWB geometry across all three Mach regimes is shown in Figure 26. A progressive increase in sweep angle and redistribution of chord lengths are observed with rising Mach number, mitigating compressibility effects and maintaining near-constant lift performance.

Figure 26.

Morphing transition of the BWB UAV geometry across Mach 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 optimal designs.

3.4.4. Discussion of Multi-Mach Trends

The combined results across the three Mach numbers reveal consistent aerodynamic trends:

- Lift Sensitivity: Geometric twist remains the dominant factor influencing lift at all Mach regimes, though its influence diminishes as Mach increases.

- Drag Sensitivity: At low Mach numbers, viscous drag dominates, yielding weak correlations with geometric variables. At higher Mach numbers, compressibility and wave drag effects make sweep angle and chord scaling decisive.

- Morphing Behavior: The optimization results confirm that an adaptive geometry, primarily adjusting sweep and local twist, can maintain aerodynamic efficiency across multiple flight conditions.

- Lift-to-Drag Ratio: The optimized L/D decreases with Mach number, dropping from approximately 34.5 at Mach 0.2 to 7.5 at Mach 0.4, consistent with increased compressibility losses.

These findings validate the theoretical sensitivity predictions from Section 2.4 and highlight the practical value of the proposed multi-Mach morphing design framework.

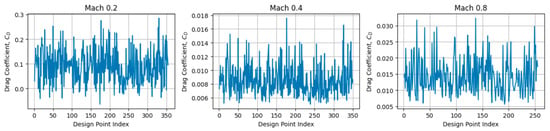

Figure 27 presents the distribution of the drag coefficient over the sampled design points generated during the Design of Experiments for Mach numbers 0.2, 0.4, and 0.8. These plots illustrate the variability of the objective function across the design space used to construct the surrogate models and demonstrate that the optimal configurations are identified within well-explored regions for each operating condition.

Figure 27.

Distribution of the drag coefficient over the sampled design points generated by the Design of Experiments illustrating the variability of the objective function across the low-speed subsonic design space.

The numerical data underlying the Design of Experiments distributions shown in Figure 27 are available in the Supplementary Material.

It is emphasized that Figure 27 does not represent a traditional gradient-based iteration history. Instead, it reflects the distribution of objective-function values obtained from the Design of Experiments sampling underlying the surrogate-based optimization framework. The final optimal designs are obtained through surrogate-based optimization using the NLPQL algorithm and are subsequently verified using high-fidelity CFD simulations.

3.5. Sensitivity Interpretation and Morphing Transition Trends

The multi-Mach optimization results presented in Section 3.4 reveal the distinct aerodynamic sensitivities of the BWB UAV geometry across subsonic and near-transonic regimes. This section interprets these results in the context of aerodynamic theory, highlighting the dominant design parameters that govern lift and drag performance, and discusses the morphing trends observed in optimized geometries.

3.5.1. Aerodynamic Sensitivity Interpretation

The parametric sensitivities obtained from the Kriging-based surrogate models provide a quantitative understanding of how individual geometric variables affect aerodynamic performance.

At low Mach numbers (M = 0.2), the aerodynamic forces are primarily governed by viscous and induced drag components.

- Geometric twist (θ_C2, θ_C3, θ_C4) shows the strongest influence on lift generation, consistent with thin-airfoil theory and the linear relation CL ≈ 2π(α + θ).

- Taper ratio and chord-scaling factors have a moderate effect by redistributing spanwise lift, while sweep and dihedral contribute negligibly to overall aerodynamic coefficients.

- Drag is relatively insensitive to most parameters, confirming that viscous effects dominate and that pressure drag cannot be substantially reduced through shape modification at these speeds.

At moderate Mach numbers (M = 0.4), the influence of compressibility begins to alter pressure distribution:

- Sweep angle and chord-scaling become increasingly significant for drag control.

- A small negative correlation between sweep and lift emerges, indicating that while sweep reduces effective Mach number normal to the leading edge (delaying wave drag), it also decreases the normal component of lift.

- The relative sensitivity magnitudes of the twist parameters decrease slightly compared to the low-Mach case, reflecting a transition in dominant aerodynamic mechanisms.

At high subsonic Mach numbers (M = 0.8), near-transonic compressibility effects dominate the flow behavior:

- Sweep angle (Λ) becomes the single most influential parameter, substantially reducing wave drag by decreasing the normal Mach number component Mn = M∞ cosΛ.

- Chord scaling at C3 and taper ratios control the distribution of local chordwise Reynolds numbers and surface pressure gradients, further influencing drag magnitude.

- Dihedral angles maintain minor but consistent effects on lateral stability rather than on aerodynamic efficiency.

These results align closely with the theoretical predictions summarized in Table 2 (Section 2.4), confirming that morphing strategies focusing on twist at low Mach and sweep at higher Mach are most effective for sustaining aerodynamic performance.

3.5.2. Morphing Geometry Trends

The morphing transitions visualized in Figure 26 demonstrate how the optimized geometry evolves across Mach regimes.

A gradual increase in sweep angle and a redistribution of chord lengths are evident as Mach number rises from 0.2 to 0.8. This trend represents a classical aerodynamic adaptation to compressibility effects:

- At Mach 0.2, the optimal configuration features a wider span and mild twist gradient, emphasizing induced-drag minimization under incompressible flow conditions.

- At Mach 0.4, the morphing geometry transitions toward slightly increased sweep and reduced taper, balancing lift and drag under mixed viscous and pressure-drag influences.

- At Mach 0.8, the geometry exhibits a pronounced sweep angle and reduced effective aspect ratio, mitigating wave drag and maintaining aerodynamic efficiency in the near-transonic regime.

To quantify the overall geometric morphing between the baseline and optimized configurations, the variations in selected design parameters are summarized in Table 16.

Table 16.

Summary of key geometric modifications between baseline and optimal configurations across Mach regimes.

These geometric transformations indicate that the morphing mechanism must accommodate adjustments in sweep and twist primarily, with secondary fine-tuning of chord ratios and winglet geometry.

3.5.3. Implications for Morphing UAV Design

The results demonstrate that morphing mechanisms enabling variable sweep and adaptive twist would provide the greatest aerodynamic benefit across subsonic flight envelopes. A hybrid morphing system, combining distributed twist actuators with inboard sweep mechanisms, could achieve near-optimal configurations for varying cruise conditions.

Key implications include:

- Twist-based morphing yields significant performance gains at low subsonic speeds where lift control is crucial.

- Sweep-based morphing becomes dominant at higher Mach numbers, providing drag reduction through wave-drag mitigation.

- Chord-scaling and taper control, though less critical individually, fine-tune pressure recovery and spanwise load distribution [35,36], complementing the primary morphing actions.

The integrated optimization framework thus provides quantitative guidance for morphing actuator placement, control strategies, and structural design requirements for future adaptive BWB UAVs.

4. Discussion

The results presented in Section 3.4 and Section 3.5 provide an integrated understanding of how geometric parameters govern the aerodynamic behavior of the BWB UAV across subsonic and near-transonic flight regimes. The discussion that follows interprets these findings in terms of fundamental aerodynamic theory, evaluates the implications for morphing aircraft design, and highlights the methodological contributions of the developed optimization framework.

4.1. Correlation with Theoretical Predictions

The optimization outcomes align closely with the theoretical sensitivity trends derived in Section 2.4.

At low subsonic speeds (Mach 0.2), where the flow is predominantly incompressible, geometric twist was confirmed as the dominant variable influencing lift generation, while taper ratio and chord scaling had secondary effects. These findings are consistent with thin-airfoil and lifting-line theory, where the lift coefficient varies nearly linearly with effective incidence. The limited drag sensitivity observed at this regime reinforces that viscous skin friction dominates, leaving minimal opportunity for drag minimization through geometry adjustments.

At moderate Mach numbers (Mach 0.4), the transition toward compressibility-affected flow produces a stronger coupling between lift and drag responses. The optimization results revealed a growing importance of sweep angle and chord scaling, confirming that compressibility corrections modify the pressure field and intensify wave-drag effects even within the subsonic range. The negative correlation between sweep angle and lift, also observed in the sensitivity data, mirrors theoretical expectations that increased sweep reduces the normal velocity component and thereby lowers lift slope.

At Mach 0.8, approaching the transonic regime, the sweep angle emerges as the most influential parameter for both lift and drag. This behavior corresponds to the theoretical reduction in normal Mach number , which delays the onset of shock formation and wave drag. The nonlinear response surfaces obtained from the surrogate models accurately capture this transition, emphasizing the growing dominance of pressure-induced drag components and validating the framework’s predictive capability.

4.2. Aerodynamic Behavior and Morphing Adaptation

The geometric transformations of the optimized configurations, progressively increased sweep, reduced twist amplitude, and minor taper adjustments, represent an aerodynamic adaptation strategy consistent with classical aircraft design principles.

At low Mach numbers, the BWB benefits from broad spanwise twist to control lift distribution and minimize induced drag.

As flight speed increases, the morphing system shifts toward higher sweep to reduce compressibility effects, while twist becomes less critical.

This aerodynamic evolution reflects the general design logic employed in variable-sweep aircraft but is achieved here through continuous morphing geometry rather than discrete mechanical sweep mechanisms.

The morphing transition also affects global aerodynamic characteristics:

- The lift-to-drag ratio (L/D) decreases with Mach number, primarily due to increasing wave-drag contribution, even after optimization.

- However, maintaining a constant design lift coefficient () across regimes enables consistent flight equilibrium, allowing drag reduction to be isolated and quantified objectively.

- The morphing strategy achieves significant drag reductions at each Mach number compared to peer designs, confirming that geometry adaptation effectively extends aerodynamic efficiency across multiple flight conditions.

4.3. Methodological Significance of the Optimization Framework

The integrated framework developed in this study, linking parametric geometry, CFD simulation, surrogate modeling, and optimization, proves highly efficient and robust for aerodynamic design exploration.

Key methodological advantages include:

- Scalability: The framework accommodates multi-Mach and multi-objective optimization without reformulating the problem, making it applicable to other aircraft configurations and performance criteria.

- Computational Efficiency: The combination of OSF and CCD sampling ensures uniform design-space coverage, while the Kriging surrogate model reduces the number of required CFD evaluations by approximately 80% relative to direct optimization.

- Physical Interpretability: The sensitivity metrics derived from the surrogate models provide clear physical insight into which geometric features dominate aerodynamic behavior, information that is often inaccessible in purely data-driven or gradient-free approaches.

- Flexibility for Multidisciplinary Applications: The modular structure allows easy integration of structural, acoustic, or control-stability objectives, making it a suitable foundation for future multidisciplinary design optimization (MDO) studies of morphing aircraft.

4.4. Design Implications for Morphing BWB UAVs

From a design perspective, the results identify specific morphing mechanisms that would yield maximum aerodynamic benefit for a BWB UAV:

- Variable-sweep mechanisms, particularly at the inboard wing sections, are essential for compensating for compressibility effects as Mach number increases.

- Distributed twist actuation across the span can maintain lift efficiency at low Mach numbers and support trim control during morphing transitions.

- Chord and taper adjustments offer fine control over pressure recovery and spanwise load distribution, complementing primary morphing actions without adding significant structural complexity.

- Adaptive control integration is recommended to dynamically coordinate sweep and twist morphing, ensuring stable operation and smooth aerodynamic transitions between regimes.

These findings highlight that a hybrid morphing configuration, combining active sweep and twist control, can outperform fixed-geometry or single-degree-of-freedom morphing designs, offering a feasible path toward high-efficiency, multi-regime UAV platforms.

4.5. Limitations and Future Development Considerations

While the aerodynamic optimization results are comprehensive, several practical factors merit consideration for future work:

- The current study focuses exclusively on aerodynamic performance under steady-state conditions; structural and actuation constraints were not explicitly modeled.

- The drag optimization excluded secondary effects such as boundary-layer transition, shock–boundary-layer interaction, and aeroelastic deformation, which may further influence the optimal geometry at higher Mach numbers.

- Implementing real-time morphing requires integration with structural and control subsystems, for example, by embedding shape-memory alloys, piezoelectric actuators, or compliant mechanisms, and incorporating their mechanical limits into the design space.

- Experimental validation through wind tunnel, taking into consideration the effects of ground effect which can cause variations in the values of aerodynamic coefficients [37].

- The surrogate modeling approach, while accurate within the evaluated domain, may require refinement with additional design points for transonic flow regimes where nonlinearities are stronger.

5. Conclusions

This study presented a comprehensive aerodynamic optimization framework for morphing BWB UAVs operating across subsonic and near-transonic regimes. The framework integrates parametric CAD modeling, CFD, and RSM-based surrogate modeling to minimize drag under constant-lift and constant-area constraints. By combining numerical simulations with data-driven optimization, the approach establishes a robust link between geometric design variables and aerodynamic performance across multiple Mach numbers.

The developed workflow, implemented in ANSYS Workbench, couples geometry parameterization, DoE sampling, surrogate modeling using Kriging interpolation, and Nonlinear Programming by Quadratic Lagrangian (NLPQL) optimization. This integration enables efficient exploration of high-dimensional design spaces with significantly reduced computational cost compared to direct optimization. The framework proved capable of accurately predicting aerodynamic behavior, with surrogate model errors below 10% relative to CFD verification and demonstrated scalability for multi-Mach and potentially multidisciplinary applications.