Abstract

Effective and transparent medical diagnosis relies on accurate and interpretable classification of medical images across multiple modalities. This paper introduces an explainable multi-modal image analysis framework based on a dual-stream architecture that fuses handcrafted descriptors with deep features extracted from a custom MobileNet. Handcrafted descriptors include frequency-domain and texture features, while deep features are summarized using 26 statistical metrics to enhance interpretability. In the fusion stage, complementary features are combined at both the feature and decision levels. Decision-level integration combines calibrated soft voting, weighted voting, and stacking ensembles with optimized classifiers, including decision trees, random forests, gradient boosting, and logistic regression. To further refine performance, a hybrid class-specific feature selection strategy is proposed, combining mutual information, recursive elimination, and random forest importance to select the most discriminative features for each class. This hybrid selection approach eliminates redundancy, improves computational efficiency, and ensures robust classification. Explainability is provided through Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations, which offer transparent details about the ensemble model’s predictions and link influential handcrafted features to clinically meaningful image characteristics. The framework is validated on three benchmark datasets, i.e., BTTypes (brain MRI), Ultrasound Breast Images, and ACRIMA Retinal Fundus Images, demonstrating generalizability across modalities (MRI, ultrasound, retinal fundus) and disease categories (brain tumor, breast cancer, glaucoma).

1. Introduction

Medical image analysis has become essential in healthcare, enabling practitioners to diagnose and treat patients with enhanced precision [1]. Together with advances in machine learning (ML) and image processing, automated systems can be employed for disease categorization, lesion identification, and tissue segmentation. However, dependable, accurate, interpretable detection remains the big task. Most medical image datasets exhibit high variability due to variations in patient demographics, differences in imaging modalities, and diverse disease presentations. Moreover, most of the state-of-the-art therapeutic decisions depend on Deep Learning (DL) models that, though accurate, often act like black boxes and thus cannot be trusted for making crucial medical decisions [2]. This lack of interpretability questions its application to real-world healthcare settings where openness and accountability are very important.

Traditional image classification approaches based on handcrafted features are promising due to their interpretability and domain specificity. Texture descriptors, form invariants, and edge characteristics may be able to find disease-specific patterns and may thus be particularly useful in specific medical settings [3]. Gabor features [4] and Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [5] are good for highlighting lesions or textural imperfections, while Hu moments [6] are effective for detecting structural defects. Color histograms [7] record the differences in pigmentation, whereas Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) [7] focuses on the border and edge information useful in disease transmission monitoring. However, most of these handcrafted features fail to model high-level abstract patterns, which usually exist in complicated medical images; hence, limiting their overall efficacy. While DL methods, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), are very prominent in learning such abstract patterns, the interpretability of how decisions are made remains difficult to understand. Besides, deep features often suffer from high dimensionality, which may introduce redundancy and inefficiency and easily cause overfitting, especially on small medical datasets.

This paper proposes a unique framework to address the aforementioned drawbacks for better classification accuracy of medical images with excellent interpretability, thereby combining the powers of deep and handmade features. The complementary nature of these features serves as the driving force behind their integration. Deep features are data-driven and might learn intricate, abstract representations of the data [8], while handcrafted features are domain-specific and interpretable [9]. The combination of these two feature categories will be implemented in this work to produce an intensive representation, capturing texture, color, form, and spatial frequency, which are the most important for medical image analysis. The statistical representation—mean, standard deviation, skewness, etc.—is also computed over the deep features to reduce the complexity of the latter but still retain the key information and get around the problems of dimensionality and redundancy that are usually associated with deep features. These statistical features can be easily combined with handcrafted ones, making the fusion process simpler and more interpretable.

A key concept here is feature fusion, allowing the combination of different sets of features into a single representation. The technique described has brought out improved performance in classification because it exploits complementary strengths among the features, further strengthening their discriminative potency. This work ensures that the representation of the data is complete through the captured different viewpoints, including texture, color, shape, and edges, by concatenating color histograms, Gabor features, HOG, LBP, Hu moments, and deep statistical features with frequency domain features, Fourier transform, and wavelet transform. The new fused feature set is tested using a calibrated soft-voting classifier that combines several models and assigns weights according to the reliability of every model. This further gives way to an improved overall performance by adding resilience to this calibrated voting system, ensuring final forecasts truly reflect the strengths of each model.

Another crucial component of this framework is its emphasis on explainability, setting it apart from the black-box nature of many DL approaches. First, the most relevant features are identified and selected using a DT-based feature assessment method, ensuring the model focuses on critical inputs. Second, class-specific feature selection highlights the most discriminative characteristics for each class, offering deeper insights into the decision-making process. Third, Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) [10] is employed in this study to produce local explanations for each prediction made by the ensemble classifier. Although commonly associated with DL models, LIME is a model-agnostic tool and is effectively utilized here to provide interpretability for the predictions of traditional machine learning models, such as the calibrated DT and Random Forest (RF) integrated through soft voting. This enables a deeper understanding of the rationale behind each prediction, regardless of the underlying model type. In addition, this work strengthens the explainability component by linking the most influential handcrafted features to clinically meaningful visual cues, allowing the LIME outputs to be interpreted in terms that align more closely with how clinicians evaluate lesions.

The proposed work removes several defects and deficiencies in current methods related to the classification of medical images. While DL techniques are, in most cases, neither interpretable nor effective, traditional approaches based solely on handmade features can hardly capture these complex patterns. Our method fills this gap by combining complementary statistical deep features and handcrafted features for reliable, interpretable predictions. Besides, the usually black-box medical image classification is transformed into a white-box approach with added explainability techniques on top of calibrated soft-voting classifiers, which makes it even more transparent and understandable. The proposed framework is intentionally designed to be effective across multiple medical imaging modalities. This demonstrates the generalizability within the medical domain, where morphological, textural, and frequency features are essential for capturing disease signatures. The key contributions of this work are as follows:

- A novel combination of handcrafted features, including Frequency Domain Features (Fourier and Wavelet), Gabor filters, Color Histograms, HOG, LBP, and Hu Moments, with statistical representation of deep features, is introduced. This fusion technique extracts complementary information from medical images, including texture, shape, spatial frequency, and edges.

- Deep features are summarized in a low-dimensional but very informative representation by calculating statistical moments (mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, energy, entropy, etc.). It not only compresses dimensions but also improves interpretability while preserving discriminative information.

- A two-stage fusion approach is proposed: (i) individual feature sets are assessed with a DT classifier, and only those with accuracy are kept; (ii) the shortlisted sets are combined to create a hybrid feature space, with only the discriminative and complementary features being included in the final model.

- Several decision- and feature-level fusion approaches are explored, such as weighted soft voting, calibrated soft voting, and stacked ensembles with Gradient Boosting and Logistic Regression meta-learners. Calibrated soft voting scheme (in which class probabilities are adjusted through sigmoid calibration and weighted by the reliability of classifiers) performs best in terms of accuracy and robustness.

- This paper introduces a novel Class-Specific Multi-Method Feature Selection (CSMMFS) approach for class-specific feature selection by combining mutual information, Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) with DecisionTreeClassifier, and RandomForestClassifier. By incorporating multiple feature selection techniques, the method identifies the most relevant and interpretable features for classification. A calibrated soft voting classifier is then employed for evaluation, enhancing both model accuracy and interpretability.

- In addition to CSMMFS, a rank-based pruning strategy is introduced, where features are iteratively ranked by their contribution to classification accuracy using a calibrated soft voting classifier. This iterative ranking–pruning process reduces redundancy, improves computational efficiency, and strengthens the robustness of the final model.

- To overcome the black-box behavior of ensemble models, this approach uses LIME for local feature attribution.

- The proposed framework is rigorously evaluated on three different medical imaging datasets (MRI, ultrasound, and retinal fundus), demonstrating strong performance and generalizability across different modalities and diagnostic tasks.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the related work, Section 3 describes the methodology adopted in this work, Section 4 provides details about the experiments conducted and the results obtained, Section 5 discusses the findings, and finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Related Work

Medical image analysis has experienced significant advancements due to the advent of ML and DL methodologies. Current work in this area can be generally classified into three categories: handcrafted feature-based methods, purely DL-based models, and fusion or hybrid approaches (Table 1). More recently, explainable artificial intelligence (XAI) techniques have been integrated with DL to mitigate the black-box nature of these models and to enhance clinical interpretability.

Early research in medical image analysis mostly used handcrafted features including texture, shape, and statistical descriptors [11]. They offered discriminative representations but were noise-sensitive and lacked scalability across imaging modalities. Comparative studies confirmed their strengths within controlled environments but also pointed out their limited generalizability in real-world clinical environments.

To overcome such limitations, hybrid systems that combine handcrafted and deep features have gained popularity. For example, hand-designed descriptors like GLCM, LBP, HOG, or morphological features were combined with CNNs to enhance diagnostic stability in areas like breast cancer, cervical cancer, and oral cancer detection [12,13,14,15,16]. Analogous approaches were pursued in cardiology and hyperspectral imaging, where hand-designed features were augmented by deep representations in data-constrained applications [17]. These hybrid methods showed that combining traditional and deep features commonly provides the best performance, especially in small or unbalanced datasets.

With improved computational capabilities and large annotated data, fully DL–based architectures have increasingly dominated research. ResNet, AlexNet, and CNNs have been extensively utilized for neuroimaging applications, including Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis, to perform effective classification of brain MRI scans [18]. Similarly, deep learning models like DeepLCCNet have been implemented for histopathological image classification of colon and lung cancers with high reliability across various types of cancer tissue [19]. These advances reflect the move from hand-engineered and hybrid methods to end-to-end deep models tailored for particular medical uses.

At the same time, XAI has been an important research area to tackle the black-box aspect of deep models. In brain tumor MRI scans, DeepEBTDNet framework utilized LIME to enhance explanation of predictions [20]. A more general contribution combined statistical, visual, and rule-based explanations, which were comprehensively validated on multiple imaging datasets with clinical experts, providing quantifiable and interpretable results [21]. For lung cancer detection, DeepXplainer incorporated CNNs with XGBoost and used SHAP-based explanations at both the local and global levels, which allowed physicians to comprehend model reasoning [22]. Such XAI-centered approaches emphasize interpretability and clinical trust while ensuring predictive performance is coupled with meaningful explanations.

Although current research has shown the potential of handcrafted descriptors, deep learning-based approaches, and explainable AI mechanisms, there are still some fundamental gaps. Handcrafted techniques, although understandable, cannot capture complex abstract representations required in heterogeneous medical images. DL models, though powerful, suffer from high dimensionality, overfitting, and a lack of transparency. Recent XAI and hybrid methods have improved, but the majority of these are designed for a single modality or condition and are not generalizable across datasets, with many giving explanations that are either not actionable at the clinical level or excessively shallow.

To overcome these limitations, the present work proposes a dual-stream explainable architecture that combines rich handcrafted features with statistically summarized deep features to find a balance between compactness, interpretability, and discriminability. In contrast to previous research, this work proposes a CSMMFS approach with rank-based pruning to eliminate redundancy and emphasize relevant features specific to every class. In addition, through the use of calibrated ensemble learning and LIME-based interpretability, the proposed framework not only achieves high classification performance over multi-modalities (MRI, ultrasound, retinal fundus) but also delivers clear and reliable insights for clinical decision-making.

Table 1 highlights progress from handcrafted to hybrid and explainable models, but gaps remain in multi-modality, redundancy reduction, and class-specific interpretability—issues addressed in our proposed framework.

Table 1.

Summary of Related Work.

Table 1.

Summary of Related Work.

| Paper | Domain | Handcrafted Features | Deep Features | Hybrid/XAI Strategy | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [11] | General Medical Imaging | Shape, Texture, BoVW | – | Comparative review | 2019 |

| [12] | Lung & Colon Cancer | GLCM, LBP, Statistical | EfficientNetB0, MobileNet, ResNet18 | Fusion + selection | 2025 |

| [13] | Breast Cancer (Ultrasound) | HOG | ResNet50 | Fusion + denoising + SVM | 2025 |

| [23] | Atrial Fibrillation | Rhythm descriptors | Deep cyclic correlation | Feature-level fusion | 2024 |

| [17] | Hyperspectral Imaging | Custom handcrafted | Siamese network | One-shot hybrid model | 2024 |

| [14] | Breast Cancer | Shape, GLCM | ResNet50 | Fusion + classical ML | 2025 |

| [15] | Oral Cancer | Expert handcrafted | CrossViT, CNN | Fusion + ANN | 2025 |

| [16] | Cervical Cancer | Morphological | CNN | Feature selection + fusion | 2025 |

| [24] | Brain Tumor MRI | Classical descriptors | DenseNet, VGG, ResNet | Hybrid + OCSVM | 2025 |

| [25] | Lung Cancer | Radiomics | InceptionNet, ViT | Fusion + CatBoost + SHAP-XAI | 2025 |

| [20] | Brain Tumor MRI | – | DeepEBTDNet | Explainable via LIME | 2024 |

| [21] | Medical Images (Multi-domain) | Statistical features | MobileNetV2 | Statistical + visual + rule-based XAI | 2025 |

| [18] | Alzheimer’s Disease | – | AlexNet, ResNet50 | Deep CNN (transfer learning) | 2025 |

| [19] | Colon & Lung Cancer | – | DeepLCCNet | Deep CNN for histopathology | 2023 |

| [22] | Lung Cancer | – | CNN + XGBoost | Explainable via SHAP (DeepXplainer) | 2024 |

3. Methodology

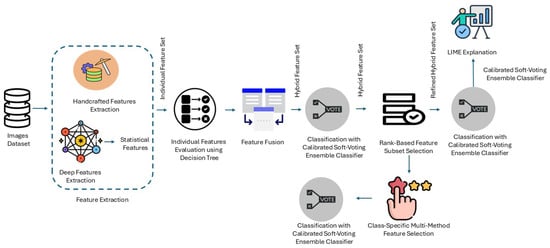

This study presents an integrated methodology combining different kinds of handcrafted features and deep statistical features, forming a hybrid feature set, classification, and LIME explanation to achieve transparent classification in the first place. The approach takes advantage of the predictive power of handcrafted features and Machine Learning (ML) models to produce more robust techniques for image classification tasks which can be implemented on any image dataset. Figure 1 provides an overview of the proposed framework. The process is divided into the following key stages:

Figure 1.

Workflow of the proposed approach.

3.1. Main Steps Description

3.1.1. Feature Extraction

Feature extraction plays a pivotal role in image classification tasks [26], as it translates raw pixel data into a compact and informative representation that captures meaningful patterns. In this stage, the handcrafted features are directly extracted from the image datasets to capture various visual and statistical characteristics. In this study, seven different kinds of features, i.e., Frequency Domain Features (FDF) (Fourier Transform Features (FTF) and Wavelet Transform Features (WTF)), color histogram, Gabor features, HOG features, LBP, deep statistical features, and Hu moments, are extracted to comprehensively capture multiple perspectives, such as color, texture, spatial frequency, shape, and edges, which are crucial for image classification. Texture features like Gabor and LBP highlight disease-specific patterns, such as spots, streaks, or rough patches. Color histograms capture changes in pigmentation, essential for identifying yellowing, browning, or discoloration caused by infections. Hu moments emphasize shape invariance, helping to detect distortions such as curling or deformation, whereas HOG focuses on the edges and borders, vital for identifying disease spread. By integrating these features, we ensure a robust analysis addressing all critical visual characteristics of plant diseases.

Handcrafted Features

Table 2 summarizes the handcrafted features, enriched with their dimensionality, domain, properties captured, and key references.

Table 2.

Summary of handcrafted features employed across the three datasets.

As shown in Table 2, these handcrafted descriptors complement each other: LBP and Gabor encode textures, HOG highlights structural edges, Fourier and Wavelet represent frequency content, color histograms model intensity distributions, and Hu moments capture invariant shape geometry.

Deep Statistical Features (DSF)

A pre-trained MobileNetv2 model DL extracts deep high-dimensional features. These features are then transformed into a comprehensive set of 26 statistical features, including mean, variance, skewness, kurtosis, etc., to capture their distributions. The statistical transformation aims to reduce the dimensionality of the deep features while retaining critical information. The details of all statistical features calculated from deep features with their formulas are given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Statistical Feature Descriptions and Formulas.

3.1.2. Individual Feature Evaluation and Threshold-Guided Hybrid Feature Selection

In this stage, each feature set is independently evaluated using a DT (DT) classifier to assess its effectiveness in distinguishing between classes. The core aim of this individual evaluation step is to understand the contribution of each feature set to the classification task and validate the discriminative power of each feature set individually. Accuracy serves as a practical choice for quick comparison across features and helps to identify features with baseline effectiveness. Let the dataset , where represents the feature vector and represents the class for an image i. For each feature type , the extracted feature vector is evaluated using a DT classifier , producing the accuracy on the dataset. The accuracy for each feature type can be calculated as

where is the indicator function, returning 1 for a true condition and 0 for a false condition.

Feature sets with accuracy are selected as part of a threshold-guided strategy to retain only those with strong discriminative power. The 70% threshold was chosen after an initial tuning process, in which several threshold points (e.g., 60%, 65%, 70%, 75%) were experimented with. Of these, 70% gave the optimal balance between keeping discriminative features and excluding noisy or weak ones, thus preserving both accuracy and efficiency. Furthermore, during this stage, the DT classifier is used due to its interpretability and ability to highlight the importance of individual features in the decision-making process. This stage serves as a preliminary filter for individual feature set evaluation before considering the combined feature set.

3.1.3. Feature Fusion

In this stage, the individual selected features—those achieving at least 70% accuracy (i.e., )—are concatenated to form a hybrid, unified, and comprehensive feature set . This step aims to combine the strengths of individual feature types, enabling the classifier to leverage complementary information present in different feature sets. The hybrid feature vector is created using the horizontal feature concatenation technique, i.e., features are concatenated along the feature dimension. Mathematically, the horizontal concatenation process is defined as

where ⨁ represents the concatenation process. If are the dimensions of the individual selected features, then the hybrid feature vector has the dimensionality of

This approach combines features extracted from multiple domains, such as frequency-domain features (FFT and wavelets), texture features (LBP and Gabor filters), and color histogram features, into a single feature vector for each image. This step helps to validate the fact that the combination of individually effective features enhances classification accuracy compared to using features in isolation. This hybrid feature vector is used for training and evaluating the classifier in the next steps. The complete procedure for feature evaluation and hybrid feature construction is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1 Threshold-Guided Feature Evaluation and Fusion |

|

3.1.4. Classification with Advanced Ensemble Approaches

To ensure robust and accurate medical image classification, multiple feature fusion and ensemble learning strategies are investigated. These strategies can be broadly categorized into feature-level fusion and decision-level fusion approaches:

(a) Feature-Level Concatenation. In this approach, handcrafted and statistical deep features were directly concatenated into a single hybrid representation. This combined feature vector integrated complementary information from frequency, texture, and statistical descriptors. The concatenated feature set was then classified using a baseline DT (DT), providing an initial benchmark for evaluating the discriminative power of the fused features.

(b) Soft Voting with Calibrated Classifiers. A probability-based ensemble was constructed using a DT and a RF. The DT was first optimized using GridSearchCV (scikit-learn version 1.3.2) to tune hyperparameters such as tree depth and minimum split size. Both DT and RF classifiers were subsequently calibrated using sigmoid-based probability calibration, ensuring reliable probability estimates. The calibrated classifiers were integrated into a soft voting ensemble, where class decisions were made by averaging predicted probabilities across models.

(c) Weighted Soft Voting. To address variations in individual classifier performance, a weighted soft voting scheme was designed. Each DT classifier trained on different feature sets (Frequency, Gabor, Color Histogram, HOG, Statistical) was evaluated individually. Their classification accuracies were normalized and used as weights in the voting process, thereby giving higher influence to more reliable classifiers.

(d) Multi-Level Fusion with Voting. A second voting-based ensemble was developed where DT classifiers trained on each feature subset contributed to the decision-making process. Here, the outputs of feature-specific classifiers were fused through probability-based soft voting, capturing complementary strengths of different feature representations.

(e) Stacking Ensemble with Gradient Boosting Meta-Learner. In this approach, multiple DT classifiers trained on individual feature sets were used as base learners. Their outputs were fused using a Gradient Boosting Classifier as the meta-learner. This two-level ensemble effectively learned higher-order feature relationships across classifiers, improving generalization.

(f) Stacking Ensemble with Logistic Regression Meta-Learner. To further investigate stacking-based decision fusion, a logistic regression classifier was used as the meta-learner on top of DT base learners trained on different feature sets. Logistic regression ensured interpretable linear decision boundaries while leveraging the diversity of base learners.

(g) Selection of Best Classifier. All the above pipelines were systematically evaluated using accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score on the independent test set. Among the multiple ensembles, the best-performing model was identified and selected for final deployment. The step-by-step process for these ensemble fusion methods can be seen in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Classification and Ensemble Fusion Framework |

|

3.1.5. Rank-Based Subset Feature Selection

To preserve only the highest discriminative features, in this paper rank-based elimination strategy based on accuracy scores is applied. An individual test of every feature with a DT classifier is performed first, and only those with an accuracy level above a specified threshold value () are included in the pool of candidates. This ensured that the starting subset included features with significant independent predictive capability.

From this pool of candidates, an iterative elimination procedure is used. With each iteration, the least informative feature—based on its DT accuracy—is eliminated, and the smaller subset ia checked using a Calibrated Soft-Voting Classifier. The soft-voting model incorporated the calibrated probability estimates of a DT and RF, thus offering a stronger evaluation of predictive performance in feature elimination. Accuracy of validation is monitored during this iteration to confirm that feature elimination did not compromise classification performance.

This process is repeated until only highly discriminative features two only were left, which are employed in calibrating the soft-voting classifier in the end. This approach ensured high predictive accuracy and feature set compactness. The step-by-step procedure is given in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 Iterative Accuracy-Guided Feature Elimination with Calibrated Soft-Voting Classifier |

|

3.1.6. CSMMFS and Classification

In this work, a new class-specific feature selection approach named CSMMFS is implemented to improve both the effectiveness and interpretability of the model. This technique optimizes feature selection for each class separately by incorporating several strategies for feature selection and performing one-vs-all. This process starts by applying mutual information-based feature selection through SelectKBest to select the most pertinent characteristics with which to distinguish between classes. Only the most relevant features are retained by the iterative selection of the most informative features concerning model performance using RFE using a DT classifier. The selection of the best features after feature importance is determined using an RF Classifier, further making the feature selection procedure more robust.

A combination of selected features from the three approaches generates a comprehensive feature set for each class. This ensures that a wide variety of discriminative characteristics, chosen by complementary methods, will be beneficial to the model. The selected features are used to train a calibrated voting classifier to improve the classification performance. The classifier in the CalibratedClassifierCV is calibrated using the sigmoid approach to get better probability estimates and, therefore, better decision-making. That would be essential for the one-vs-all classification challenge.

The integration of feature selection methods does assure better interpretability and performance of the model since it provides a multi-faceted method of feature selections for more reliable and correct feature selections. Class-specific feature selection offers an added advantage in being specific for each class on unique features, hence allowing categorization to be more focused and efficient. The full procedure of the CSMMFS method and its integration with the classification model is outlined in Algorithm 4.

| Algorithm 4 Class-Specific Multi-Method Feature Selection (CSMMFS) |

|

3.1.7. LIME Explanation

LIME, a widely recognized model-agnostic explainability model, is used to enhance the transparency of the developed classification models. LIME provides human-understandable explanations for predictions made by machine-learning models. This model essentially approximates the decision boundary of a model locally around an instance and selects the most influential features contributing to the prediction. In this study, LIME is used to provide insight into the predictions produced by the ensemble voting classifier and class-specific DTs.

For the ensemble voting classifier, LIME is used to explain the predictions at a global level across all target classes. The LIME method has been applied to deconstruct the predictions of the voting classifier, revealing the top features that drive model decisions for various instances. By generating feature-specific explanations, LIME provided details on how the voting classifier aggregated predictions from individual base classifiers to arrive at its final decision. Whereas, in the case of class-specific DTs, LIME allowed analyzing feature contributions for each target class by using a one-vs-all strategy. For this, the class-specific selected features and the DT predictions are explained using LIME to highlight which features are most relevant to the prediction.

Apart from presenting rankings on features, it allows better explainability because it relates highly influential manually engineered feature sets with meaningful image attributes. Texture features like Gabor filters and LBP are related to local irregularities and boundary roughness, HOG features relate to the presence and sharpening of structural boundaries, and Hu moments relate to global asymmetry. Frequency domain features (Fourier and Wavelet) relate to structural changes ranging from coarse to fine and include things that radiologists focus on while interpreting images to detect lesions. Based on these mappings, short natural language descriptions are added with LIME outputs for better understanding of regions influencing predictions.

This allows the framework to move beyond purely numerical importance scores toward more interpretable explanations of model behavior. LIME identifies the most influential features for each prediction and presents their relative contributions in a transparent manner, which can support clinical interpretation when combined with domain knowledge.

Overall, the integration of LIME in this methodology ensures that the developed classification models are both accurate and interpretable, and thus, allows a better understanding of the decision-making process of such models and their suitability for real-world applications.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Datasets

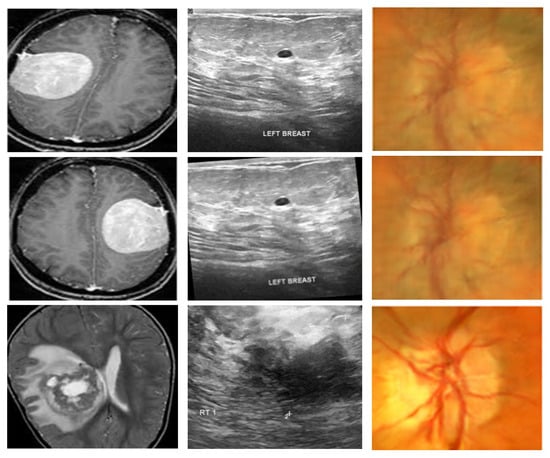

To assess the generalizability and effectiveness of the proposed framework, experiments are conducted on three publicly available medical imaging databases that span various modalities and diagnostic complexities. The summary of the datasets is given in Table 4 whereas the representative samples from these datasets are given in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Summary of the datasets used in this study.

Figure 2.

Representative samples from all datasets: the first, second, and third columns have representative samples from dataset 1, dataset 2, and dataset 3.

4.1.1. BTTypes (Dataset 1)

The first dataset, BTTypes [38] is sourced from the open dataset Brain MRI Images for Brain Tumor Detection [39], which initially comprised 11 benign and 12 malignant MRI scans. For enhanced sample diversity and stronger training robustness, the BTTypes authors employed multiple augmentation strategies, resulting in a total of 2400 MRI images, which were balanced equally between 1200 benign and 1200 malignant cases.

4.1.2. Ultrasound Breast Cancer Images (Dataset 2)

The second dataset, Breast Ultrasound Images for Breast Cancer [40], is used for the detection of breast cancer using ultrasound images. Rotation and sharpening augmentation techniques were employed to expand the dataset to 9016 images, comprising 4574 benign and 4442 malignant images.

4.1.3. ACRIMA Retinal Fundus Images (Dataset 3)

The third dataset is ACRIMA, one of the subsets of the Generated Eye Dataset for Glaucoma Detection on Kaggle [41]. The entire repository combines five collections (RIM-ONE, ACRIMA, HRF, Drishti-GS, and ORIGA-LIGHT), comprised of a total of 30,000 images. For our research, only the ACRIMA subset was employed, consisting of 6000 retinal fundus images, divided into 3000 glaucoma cases and 3000 normal cases.

This cross-dataset assessment guarantees that the designed framework is tested on various imaging modalities (MRI, ultrasound, and retinal fundus) and disease categories (brain tumor, breast cancer, and glaucoma) to ensure robustness and flexibility.

4.2. Experimental Setup

This section provides comprehensive details of the experimental setup, including the computational environment, programming tools, data partitioning and evaluation protocol, performance evaluation metrics, and hyperparameter optimization strategies, to ensure the reproducibility of the results. Hyperparameter optimization using GridSearchCV (scikit-learn version 1.3.2) was performed separately for each dataset, and the resulting best parameter values were applied in subsequent experiments. All experiments followed a strict train-test protocol. Feature ranking, subset selection, hyperparameter tuning, probability calibration, and ensemble construction were performed exclusively on the training and validation data (85%), while the test set (15%) remained completely unseen until final evaluation. Hyperparameter optimization was conducted using cross-validation within the training stage. Furthermore, the model complexity was constrained using depth and sample-based regularization. This design minimizes data leakage and mitigates overfitting, ensuring that the reported performance reflects genuine generalization rather than memorization. The details are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of Experimental Setup.

Implementation Specifications for Reproducibility

To address reproducibility concerns, we specify the following implementation details: deep features were extracted from the MobileNetV2 global average pooling layer, (layer[-4]), producing 1280-dimensional vectors. These features were normalized during preprocessing using MobileNetV2’s native preprocessing function . Twenty-six statistical features were computed from these already-normalized deep feature vectors without additional normalization, including mean, standard deviation, skewness, kurtosis, entropy, and signal-to-noise ratio, with added for numerical stability. In the CSMMFS, features were selected per class using mutual information, with Decision Tree classifiers (maximum depth = 10) trained on selected features. Data augmentation was applied to the training sets using rotations, shifts, shearing, zooming, and horizontal flips, and the MobileNetV2 preprocessing function was applied to all input images.

4.3. Classification Results

This section presents the evaluation results of the proposed methodology, including individual feature evaluation, the calibrated soft-voting classifier with feature fusion, and the class-specific feature selection approach.

4.3.1. Individual Feature Evaluation

The first step is the assessment of individual feature sets (handcrafted features and deep statistical features) through a DT classifier. The findings, as summarized in Table 6, indicate significant differences in characteristic performance within the three datasets (BTTypes, UBIBC, and ACRIMA).

Table 6.

Performance of Individual Feature Sets for Classification using DT across Three Medical Imaging Datasets. All performance metrics (Accuracy (ACC), Precision (PRE), Recall (REC), and F1-Score (F1)) are reported in percentage (%).

For the BTTypes dataset, frequency-domain features achieved the best performance, with a precision of 96.67% and an F1-score of 96.67%. This shows that spectral representations are very discriminatory in distinguishing benign and malignant tumor tissues from MRI scans. Gabor features (93.89%) and Local Binary Patterns (92.50%) also performed competitively, indicating that texture-based descriptors extract important local patterns from MRI data. However, Hu moments (58.61%) and color histograms (59.72%) performed poorly, indicating the minimal contribution of global shape and intensity distribution here.

In the UBIBC dataset, statistical features worked best, achieving an accuracy of 80.80% and an F1-score of 80.73%. This indicates that straightforward intensity-based descriptors provide significant discriminatory information for ultrasound breast images, perhaps because of the intrinsic grayscale texture difference between benign and malignant cases. Out of texture-based features, Gabor features (74.58%) marginally surpassed LBP (68.88%), whereas frequency-domain features (71.99%) and HOG (71.84%) showed moderate performance. Once more, Hu moments (65.42%) and color histograms (57.65%) proved to be of limited use.

For the ACRIMA dataset, HOG features provided the highest accuracy of 91.78%, proving that edge and gradient-based descriptors play a crucial role in retinal fundus images for glaucoma diagnosis. Gabor (88.56%) and statistical features (88.33%) also showed robust outcomes, affirming the role of texture and intensity distributions. By contrast, Hu moments are most ineffective (50.00%), which shows that global shape descriptors are uninformative in this dataset. Histograms and frequency-domain features attained moderate accuracies of 76.78% and 76.33%, respectively.

In summary, the findings show that no single feature consistently outperforms across all datasets. Frequency-domain features prevail in MRI (BTTypes), statistical features dominate in ultrasound (UBIBC), and HOG achieved better results in retinal images (ACRIMA). This dataset-dependent variation emphasizes the need for a feature fusion approach since, alone, each descriptor cannot generalize over different modalities. As a result, in later steps of our approach, we take advantage of feature fusion to combine the strengths of various descriptors to improve classification robustness and generalizability.

4.3.2. Calibrated Soft-Voting Classifier with Feature Fusion

The second experimental phase utilized a threshold-based feature selection method, where feature extractors with an accuracy ≥70% in the standalone evaluation phase are kept.

The relative comparison of various feature fusion and classification methods on BTTypes, UBIBC, and ACRIMA datasets yields a number of key observations (Table 7). For the BTTypes dataset, the straightforward approach of concatenation with a DT produced a robust baseline with an accuracy of 96.11%. However, ensemble methods such as majority voting, weighted voting, and stacking with logistic regression and gradient boosting were not highly effective, as their performance plateaued at 92.78%. This implies that although ensemble methods are more powerful theoretically, they might be prone to redundancy and lack of diversity among the individual models when used in this data set. In contrast, the calibrated soft voting classifier showed a significant improvement with the best accuracy of 98.61% along with steady improvements in precision, recall, and F1-score. The better performance of this method emphasizes the role of probability calibration in minimizing the overconfidence of base learners and inducing a greater probabilistic consensus.

Table 7.

Comparison of feature fusion and classification strategies for all datasets. All performance metrics (Accuracy -ACC-, Precision -PRE-, Recall -REC-, F1-Score -F1-) are reported in percentage (%).

The UBIBC dataset exhibits a different operating regime. Here, the simple concatenation with DT achieves a moderate baseline (). Non-calibrated ensembles show little to no improvement: for example, accuracy of traditional voting reaches , while weighted voting, stacking with a logistic meta-learner, and gradient boosting are still at . These observations indicate that naively combining uncalibrated predictions does not profit from complementary information in this heterogeneous ultrasound dataset. In contrast, the calibrated soft-voting classifier significantly improves performance to (with corresponding gains in , , and F1-score), yielding an absolute improvement of percentage points over the baseline and decreasing the relative error rate from to —a reduction of approximately . This substantial improvement highlights the critical role of probability calibration, which aligns class-conditional score distributions, regularizes confidence estimates, and ultimately enhances generalization.

For the ACRIMA dataset, the baseline DT itself had quite competitive performance (94.78%), with minimal gains when using weighted voting and stacking techniques (94.89%). But, just like in the BTTypes dataset, the calibrated soft-voting classifier attained a quantum leap in performance, delivering a top-notch accuracy of 99.19%. This achievement highlights the strength of calibrated ensembles, especially for datasets with already high feature-level discriminative capability. The consistent performance advantage of the calibrated soft-voting classifier on all three datasets reinforces its capacity to strike a balance between individual strengths of different classifiers while making up for overfitting and miscalibration shortcomings.

In conclusion, these results show that (i) threshold-guided feature selection with hybrid fusion offers a consistent basis across modalities and illnesses, (ii) non-calibrated ensembling can perform worse or plateau when learners are too homogeneous or mis-calibrated, and (iii) calibrated soft voting consistently enhances decision performance by balancing posterior scores between models. The steady improvements on the three datasets verify that probability calibration is one of the central facilitators for strong decision-level fusion in medical image classification, especially when fusing heterogeneous handcrafted descriptors and statistical deep features.

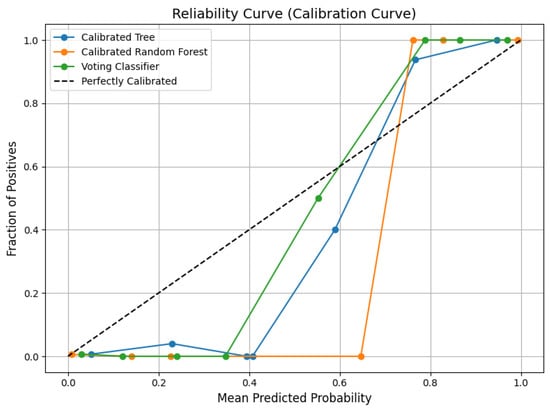

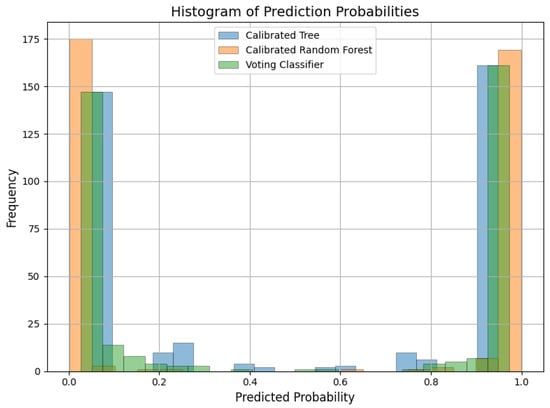

To further demonstrate this effect, a calibration analysis is conducted with reliability curves and probability histograms on the BTtypes dataset as an illustrative example. A calibration curve (Figure 3) shows predicted probability versus the actual outcome, where closeness to the diagonal represents good calibration. As demonstrated, the calibrated soft-voting classifier achieves probabilities that closely follow the ideal diagonal, reflecting well-calibrated estimates. Conversely, the calibrated DT and calibrated RF both have greater deviations, indicating less accurate probability estimates. Further insights are provided from the histograms of probabilities (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Reliability curve (calibration curve) comparing the predicted probabilities to the actual fraction of positives for the calibrated DT, calibrated random forest, and voting classifier.

Figure 4.

Histogram of predicted probabilities for the calibrated DT, calibrated random forest, and voting classifier for BTType dataset.

The soft-voting classifier is observed to give a well-separated distribution of probabilities, indicative of confident and discriminatory predictions, especially for the positive class. In contrast, the individual calibrated classifiers give less separated distributions, again supporting that the fusion-plus-calibration approach sharpens class discrimination. Together, these visualizations establish that the observed accuracy improvements (Table 7) are not just a result of increased accuracy but also due to more reliable probability estimates. This discussion highlights the merits of feature fusion combined with calibrated ensemble learning since it guarantees both better classification scores and more interpretable, reliable results.

4.3.3. Rank-Based Subset Feature Selection Results

The results of the rank-based subset feature selection, outlined in Table 8, show how effectively the hybrid feature set is progressively improved in all three datasets. For BTTypes, it can be seen that the reduction in feature space from five to two features not only increased the accuracy of classification but also dramatically reduced execution time, finally resulting in the best performance of 99.44% accuracy, precision, recall and F1-score with two features. This reveals the ability of rank-based refinement to remove redundancy without losing the most discriminative features. Similarly, the trend in the UBIBC dataset is also noted, where there is a slight decline in performance when fewer features are used; however, the optimized hybrid feature set retained the best accuracy rate of 88.54% with significant reductions in execution time, indicating a trade-off between accuracy and efficiency. In the case of the ACRIMA dataset, the classification performance is consistently good (99.89%) irrespective of the feature subsets, indicating that the dataset is robust to feature reduction by nature. However, the optimized hybrid feature set achieved the same level of accuracy as the larger subsets, but with a significant reduction in computational efficiency. In general, the results confirm that the rank-based subset feature selection approach effectively discovers compact and informative sets of features that either preserve or enhance classification performance while significantly lowering computational cost, thus providing a strong and efficient solution for feature optimization.

Table 8.

Rank-Based Subset Selection Results with Accuracy -ACC-, Precision -PRE-, Recall -REC-, F1-Score -F1-, and Execution Time. All performance metrics are reported in percentage (%), while Time is reported in minutes (min) and seconds (s).

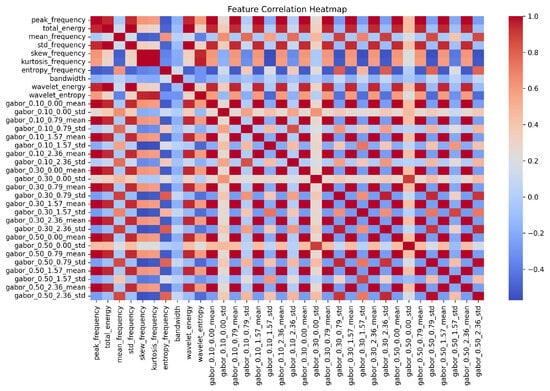

To further analyze the relationships between the selected features, a correlation heatmap is generated for the final refined hybrid feature set of the BTTypes dataset (Figure 5). This heatmap provides a visual representation of the Pearson correlation coefficients between the final refined hybrid feature set, i.e., Gabor and FDF, offering insights into the diversity and complementarity of the selected features. Minimal high correlations are observed, indicating that the fused features contribute independently to the classification task. The results highlight that settling on a small yet meaningful feature set, aided by the rank-based subset selection, not only improves computational efficiency but also enhances classification performance.

Figure 5.

Correlation Analysis of the Final Refined Hybrid Feature Set for BTTypes Dataset. More intense colors indicate stronger correlations, while less intense colors represent weaker correlations.

Overall, by settling for a small but very useful set of features, the rank-based subset selection proves it is capable of improving computational efficiency besides enhancing the performance of classification. The results show how feature subset assessment is important in increasing accuracy and execution speed for the overall technique.

4.3.4. Class-Specific Feature Selection Results

Table 9 summarizes the performance of the proposed CSMMFS approach on three benchmark medical imaging datasets. The results show three key observations: (i) the selection of highly discriminative class-specific feature subsets, (ii) the removal of redundant descriptors without sacrificing accuracy, and (iii) improved interpretability by disclosing modality- and class-specific feature importance.

Table 9.

Performance of (CSMMFS). All performance metrics (Accuracy -ACC-, Precision -PRE-, Recall -REC-, F1-Score -F1-) are reported in percentage (%).

For the BTTypes dataset, both malignant and benign tumor classes attained close-to-perfect classification performance, with accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score all above 98%. Feature subsets chosen mostly included frequency-domain descriptors and Gabor features (e.g., gabor_0.10_0.00_std, kurtosis_frequency, wavelet_entropy), confirming that local texture and spectral signatures are extremely discriminative in brain MRI tumor characterization. Interestingly, the benign class needed a marginally larger set of features than malignant ones, indicating that benign tumor textures are more diverse, therefore requiring a more feature-rich space for accurate classification.

In the UBIBC dataset, the benign vs. malignant breast lesion classification showed moderate performance with accuracies of approximately 71–72%. While lower than BTTypes, this finding corresponds to the intrinsically difficult nature of ultrasound imaging, wherein speckle noise and minimal contrast diminish feature separability. Surprisingly, the chosen subset of features was the same for both classes, mostly composed of frequency- and Gabor-based features in addition to a HOG descriptor. This invariance across classes indicates that discriminative information in ultrasound breast images is encoded globally in texture and edge representations instead of being class-specific. Although with modest performance, the capability of CSMMFS to decrease the feature set while maintaining stable classification scores indicates robustness.

For the ACRIMA dataset, aiming to detect glaucoma from retinal fundus images, the CSMMFS method had accuracies of more than 82% for both glaucoma and normal classes. The chosen features (mean_frequency, entropy_frequency, gabor_0.30_0.79_std, hue_std) highlight the importance of frequency entropy and color changes in separating glaucomatous structural alterations from regular retinal patterns. In contrast to the UBIBC dataset, the chosen features for the two classes were once more strongly overlapping, indicating that the discriminability is evenly distributed across classes but nonetheless adequate to obtain consistent classification.

In total, the findings show that CSMMFS not only minimizes dimensionality but also discloses class-dependent feature importance. In good-quality imaging modalities like MRI (BTTypes), the technique provides near-perfect classification with very small sets of features, proving that redundant descriptors may be safely removed without losing information. For more difficult modalities like ultrasound (UBIBC), performance is moderate but consistent, suggesting that the bottleneck is more in image quality rather than in feature selection. In retinal fundus images (ACRIMA), the chosen features emphasize the significant role played by frequency entropy and color-based descriptors in disease identification. These observations confirm the practical value of CSMMFS in enhancing interpretability without sacrificing competitive performance across heterogeneous imaging modalities.

4.4. LIME Explainability

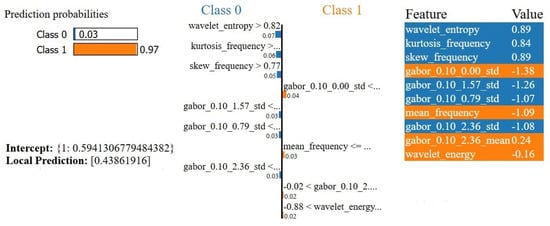

The LIME model is utilized in this work to explain the predictions of the calibrated soft-voting classifier with feature fusion. LIME provides local explanations using an interpretable surrogate model, such as linear regression, to approximate the decision boundary of the classifier for individual instances. For this experiment, the BTTypes dataset is used as the representative dataset since it displays an evenly distributed range of classification performance across various fusion and ensemble approaches, ranging from fairly good accuracy (≈92.78%) to extremely good accuracy (≈98.61%). This variation makes it well-suited for exploring how the model’s decision-making changes across different performance levels, without the risk of trivial explanations on near-perfect datasets like ACRIMA, while avoiding under-representative patterns in datasets where the algorithms perform less effectively, such as UBIBC. Two examples from BTTypes are employed for explanation, where the contribution of the top ten features to the classifier’s prediction for each example is shown. These outcomes show how LIME breaks down the feature values and measures their contribution to the class probabilities that are predicted, thus providing insightful information regarding the local decision-making process of the classifier.

The clinically meaningful interpretation of the feature groups supplements the LIME outputs to extend the interpretability beyond just basic feature rankings. Given that the framework uses handcrafted descriptors that have clear semantic meanings, the features influential according to LIME can be associated with visually interpretable image patterns from clinical imaging. Texture-based descriptors (Gabor and LBP) are associated with tissue heterogeneity and boundary roughness, while the HOG descriptors relate to edge sharpness and lesion borders. Hu moments represent global shape symmetry or distortion. Frequency-domain descriptors, including Fourier and wavelet, are related to coarse or fine structural variations within the tissue. Merging these associations forms a natural-language layer that describes not only which features matter, but also why they are relevant from a diagnostic point of view.

More explicitly, frequency-domain entropy and related spectral statistics quantify the degree of disorder and variability in image intensity patterns. These are commonly associated with pathological tissue disorganization, such as irregular lesion interiors and disrupted structural continuity. High entropy or kurtosis in the frequency domain reflects the presence of complex, non-uniform texture patterns that are frequently reported in malignant regions. Orientation-specific Gabor responses capture directional edge and texture information, making them sensitive to changes in boundary sharpness, anisotropy, and local structural alignment. Elevated responses at particular orientations therefore correspond to distorted lesion margins, abnormal tissue alignment, or loss of regular architectural patterns, which are well-known visual indicators of malignancy. By grounding these features in recognizable pathological image characteristics, the LIME-based explanations become directly interpretable from a clinical imaging perspective.

For the first test instance, the explanation provided by LIME is presented in Figure 6. The classifier gave a probability of 0.97 to Class 1 (malignant), with 0.03 for Class 0 (benign). The LIME explanation presents the interpretation of specific features that contribute to the prediction made. For instance, wavelet_entropy, kurtosis_frequency, and skew_frequency contributed towards Class 0 (benign), while features like gabor_0.10_0.00_std, mean_frequency, and wavelet_energy contributed heavily in the positive direction for Class 1 (malignant). The value of the intercept, 0.5941, gives a prior probability for Class 1 (malignant) before considering individual feature contributions. The local prediction of the instance, computed to be 0.4386, is the probability for Class 1 based on only those features present in the LIME explanation. While the local prediction does not exactly match the overall prediction of 0.97, this indicates how those key features are influencing the model’s decision. This difference suggests that further features beyond those present in this LIME explanation also weigh heavily on making the final prediction probability.

Figure 6.

LIME explanation of a test instance’s prediction. The classifier predicted Class 1 (malignant) with a probability of 0.97. Feature values and contributions to each class are displayed.

From a clinical perspective, there is consistency between the malignancy prediction and feature behavior, wherein a prominent presence of Gabor texture representation and high energy values from the wavelet representation indicate irregular textures and localized structure irregularities. These correspond to texture variability and minute irregularities on lesions that malignancy reports usually relate to.

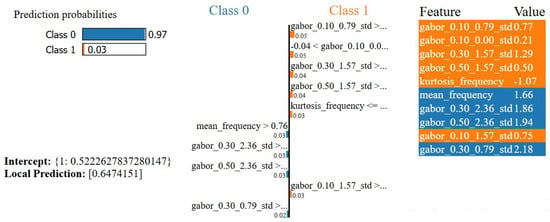

Furthermore, the LIME explanation for the second instance is shown in Figure 7. Class 0 (Benign) is predicted by the classifier with a high probability of 0.97, whereas Class 1 (Malignant) is expected with a probability of 0.03. Bars of feature contributions depict several features that came into play in making the prediction. The most influential attributes toward Class 0 (benign) are mean_frequency, gabor_0.30_2.36_std, and gabor_0.50_2.36_std, for which the probability of prediction was shifted. In contrast, attributes that supported Class 0 had a much stronger general influence than those that supported Class 1, malignant, such as gabor_0.10_0.79_std, gabor_0.10_0.00_std, and gabor_0.10_1.57_std. By far, the feature that best supported Class 0 was the mean_frequency, contributing positively with a high value of 1.66. The intercept value of 0.5223 represents the base probability of Class 0 (benign) before the contributions of the individual variables. It means predicting the model for those cases without feature-specific effects. In this case, considering only the described attributes, the local prediction is estimated to be 0.6474, and the predicted class is Class 0 (benign). This number shows that the selected features in the LIME explanation account for most of the model’s conclusion since it is very close to the overall prediction probability of 0.97 for Class 0.

Figure 7.

LIME explanation of a second test instance’s prediction. The classifier predicted Class 0 (benign) with a probability of 0.97. Feature values and contributions to each class are displayed.

This benign classification also agreed with the clinical interpretation of the feature set. Larger contributions from the stationary frequency components and more refreshing Gabor responses reflect the tissue organization on a regular basis, while the absence of large deviations in edge distortion suggests well-defined contours in the lesions. These characteristics correspond with benign tumor patterns that typically exhibit homogeneous texture and minimal structural irregularity.

These details highlight how specific features contribute to the model’s classification and the interaction of their positive and negative influences on the final prediction. Integrating clinically aligned interpretive mappings with LIME outputs, the approach goes further than numeric attribution explanations. This allows clinicians to better understand how texture, shape, and frequency characteristics contribute to each decision and thus enhance transparency by improving the clinical interpretability of the model.

4.5. Comparison Against Baseline Models

To validate and evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed approach, the classification performance of the calibrated soft-voting classifier on the refined hybrid feature set is compared to a diverse set of classification algorithms, including DT, ensemble methods (e.g., bagging, AdaBoost, and gradient boosting), support vector machines (SVM), linear classifiers (e.g., logistic regression, ridge classifier), probabilistic classifiers (e.g., Gaussian Naive Bayes), and neural network-based models (e.g., MLP classifier). The primary aim of this comparison is to assess the robustness and superiority of the proposed approach in leveraging the refined hybrid feature set for accurate and transparent classification. All these comparative classifiers are trained and tested using the same refined hybrid feature set comprising the fused FDF and Gabor features. All classifiers are trained in the same experimental setting, including features sets and data splitting to ensure fair comparison. It is important to note that this comparative evaluation is conducted only on the BTTypes dataset, as it provides the most balanced and diverse representation of tumor types, making it the most suitable benchmark for baseline validation.

Results point out that the proposed approach, namely Calibrated Soft-Voting Classifier, outperforms other approaches for all measures like accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score, respectively: 99.44%, 99.44%, 99.44%, 99.44%, presented in Table 10. The MLP classifier achieved the second highest classification performance, with an accuracy of 99.17%, followed by gradient boosting at 97.22% and bagging at 98.61%. Other traditional classifiers, such as DT, SVM, and K-Nearest Neighbors, also performed well with accuracies above 95%. The simpler models, like Gaussian Naive Bayes with 61.67% and Logistic Regression with 79.44%, performed very poorly, indicating that they are incapable of handling the dataset complexity.

Table 10.

Classification performance comparison with other classifiers on the refined hybrid feature set. All performance metrics (Accuracy -ACC-, Precision -PRE-, Recall -REC-, F1-Score -F1-) are reported in percentage (%).

The proposed Calibrated Soft-Voting Classifier performed very well, effectively combining the calibrated DT and RF models and using their advantages by employing probabilistic soft voting. Furthermore, the use of calibrated classifiers also ensured precise probability estimates, further enhancing the whole ensemble’s prediction reliability. These results show that the redefined hybrid feature set gave the classifier the ability to capture the discriminative properties of the brain tumor MRI dataset at both lower and higher levels. Overall, the proposed system demonstrated the robustness and dependability of its decisions, apart from outperforming all baseline classifiers. Such results prove the effectiveness of the proposed approach and show its potential for correct and interpretable medical image categorization.

4.6. Comparison with Modern Deep Learning Architectures

To provide a contemporary experimental context, the proposed framework is compared with representative end-to-end DL baselines, including a standard CNN, a Vision Transformer (ViT), and a hybrid CNN-Transformer model, across all three datasets. These architectures are widely adopted in recent medical image analysis literature and serve as strong modern baselines.

As reported in Table 11, the proposed method achieves performance comparable to or exceeding transformer-based architectures while relying on substantially fewer trainable parameters. Specifically, it matches Transformer-level accuracy on BTTypes, closely follows the performance of CNN-Transformer on UBIBC, and clearly outperforms all baselines on ACRIMA. From a computational perspective, Vision Transformers incur significantly higher training and inference costs, whereas the proposed framework maintains competitive training times and moderate inference latency despite its multi-stage design. Importantly, the refined hybrid feature representation is compact, resulting in a markedly lower parameter count than end-to-end deep models, which improves suitability for deployment in resource-constrained clinical environments.

Table 11.

Performance and computational comparison across all datasets. All performance metrics (Accuracy – ACC, Precision – PRE, Recall – REC, F1-score – F1) are reported in percentage (%).

Overall, these results demonstrate that the proposed framework offers a favorable trade-off between accuracy, interpretability, and computational efficiency when compared with both simpler CNN baselines and modern Transformer-based architectures.

5. Discussion

This work highlights several important findings about explainable medical image classification. Firstly, the underlying hypothesis, that statistical and handcrafted deep features are complementary in strengths, was proven. Fusion at the feature level always enhanced accuracy and robustness across modalities, while decision-level calibration was stabilized by mitigating overconfidence among base learners. Class-specific multi-method feature selection also supported the concept that adapting features to specific classes improves both discriminability and interpretability.

From a methodology point of view, the architecture was effective but not without trade-offs. Adding multiple stages of feature selection increases computational overhead, resulting in longer training times compared to basic baselines. Although this introduced some cost, it was balanced by the improved inference efficiency, since the refined hybrid feature space reduced redundancy and dimensionality. Generally, the strategy was moderately slower to train but still feasible for research-scale datasets. Subsequent research should more systematically compare execution times to baseline CNN-only pipelines as a basis for comparison.

Another important observation is that calibrated ensembles perform better compared to naive voting or stacking when classifiers are homogeneous or ill-calibrated. This reinforces the need to not only combine models but also to ensure their probability estimates are reliable. The uniform success of calibrated soft voting for MRI, ultrasound, and fundus images implies that the approach is generalizable across modalities, even though additional validation on more heterogeneous, real-world datasets would be required.

An important enhancement in this approach is also that it employs meaningful hand-crafted feature vectors, which makes it possible to link critical groups of influential features with concepts including boundary sharpness, asymmetry, textual irregularity, and frequency-driven structural variability. By enabling links such as these, the explainable system can generate interpretations not limited solely to feature vector rankings but instead link these rankings with LIME graphs and natural language statements. By doing so, it moves beyond pure “Level 0” XAI and enhances feature attributions with concepts about why the model prefers a specific classification. While it remains short of being a comprehensive narrative platform, it greatly enhances explainability.

Given the very high performance observed on the BTTypes and ACRIMA datasets, potential overfitting was carefully considered. To mitigate this risk, strict separation between training and test data was enforced. Furthermore, all feature selection, hyperparameter tuning, probability calibration, and ensemble construction were performed exclusively on the training set. Hyperparameters were optimized using cross-validation, and model complexity was explicitly constrained through depth and sample-based regularization. The consistently strong performance across validation folds suggests that the results are not driven by a single favorable split. Nevertheless, additional robustness analysis using repeated random splits or multiple independent runs would further strengthen confidence in generalization and is identified as an important direction for future work.

In spite of being top-performing and showing robustness on multiple datasets, the framework has some limitations. First, all experiments were conducted on publicly available Kaggle datasets, which may limit the assessment of generalization to completely independent external datasets. While the reported results demonstrate robustness within these sources, further validation on external clinical datasets from other institutions is required to fully confirm generalizability. This limitation is highlighted here to provide a balanced interpretation of the current findings and to guide future extensions toward broader dataset evaluation. Second, the present classification problems were binary (tumor vs. non-tumor, benign vs. malignant, glaucoma vs. healthy), while real-world medical applications mostly require multi-class or multi-label classification. The proposed CSMMFS can be naturally extended to multi-class scenarios using a one-vs-rest or one-vs-one feature selection strategy to preserve class-specific discriminative power. Similarly, the calibrated soft-voting ensemble can aggregate probability outputs across multiple classes, mitigating overconfidence while maintaining accurate predictions.

Third, LIME offers insightful local explanations but fails to utilize the entire global interpretability of the ensemble decision process. Fourth, while statistical summarization of deep features increased interpretability, it might lose high-resolution representational detail in certain situations. Lastly, the framework depends deeply on handcrafted features such as Gabor filters, HOG, and Hu moments for in-depth texture and shape analysis in medical imaging. However, the direct application to other image domains requires necessary feature adaptations or replacement of the feature sets suitable for the new domain.

Future research will involve validating the framework on multi-class and multi-label datasets to assess the scalability and robustness of CSMMFS and the calibrated soft-voting strategy in more complex clinical scenarios. Future research will generalize the proposed framework to deal with multi-class and multi-label problems in medical image analysis and explore whether and how it can be applied to other imaging modalities like CT, PET, and histopathology slides. Domain adaptation, transfer learning, and the inclusion of domain-agnostic or learned features should also be investigated to enhance robustness across external datasets from different institutions and acquisition devices. This will extend the applicability of the framework to other image domains where the specific morphological or textural descriptors used in this work may not be discriminative. Next-generation interpretability techniques (e.g., counterfactual explanations, global surrogate models, and causal reasoning techniques) will also be incorporated to supplement LIME, providing both local and global transparency. The application of unsupervised clustering for feature space discovery and federated learning for model training without compromising privacy are areas of promise to scale the framework towards clinical application in real-world settings. Lastly, future work will involve investigating feature preselection, dimensionality reduction, and model pruning as methods for further optimizing computational requirements when deploying the models in resource-constrained clinical settings.

In short, the outlined framework is well-balanced between accuracy, interpretability, and generalizability, though at the expense of additional training time. These findings indicate that hybrid handcrafted–deep methods with calibrated ensembles are promising as general-purpose methods for interpretable medical image analysis, subject to further extension by future work to larger datasets, multi-class scenarios, and clinical use in real-world settings.

6. Conclusions

This paper presents an explainable and novel multi-modal medical image classification framework that combines handcrafted descriptors with deep statistical features using a dual-stream architecture. The new framework utilizes frequency-based descriptors (Fourier, Wavelet, Gabor), spatial features (LBP, HOG, Hu moments), and color histograms, in addition to deep feature embeddings of a custom MobileNet. For strong representation and interpretability, a two-stage feature fusion process is used, followed by ranked-based feature selection strategy and the proposed CSMMFS method. These methods remove redundancy, lower dimensionality, and retain class-discriminative information. The combined and fine-tuned feature sets were assessed by calibrated ensemble models (soft voting, weighted voting, and stacking) on three benchmark medical image datasets: BTTypes (MRI for tumor detection in the brain), Ultrasound Breast Images (ultrasound for breast cancer detection), and ACRIMA Retinal Fundus Images (glaucoma detection). Results show that the framework outperforms baseline algorithms consistently and is state-of-the-art performance across a range of imaging modalities (MRI, ultrasound, retinal fundus) and disease types (brain tumor, breast cancer, glaucoma), thereby establishing its robustness and generalizability as a powerful tool for the medical imaging domain. Additionally, including LIME facilitated interpretable explanations of the ensemble models’ decision-making process. LIME further strengthens explainability by offering a clearer connection between feature contributions and medically relevant image characteristics. This expanded interpretability component represents a meaningful step toward more transparent and trustworthy diagnostic systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.U., I.D.F. and G.S.; methodology, N.U.; software, N.U.; validation, N.U., I.D.F. and G.S.; formal analysis, N.U., I.D.F. and G.S.; investigation, N.U., I.D.F. and G.S.; resources, I.D.F. and G.S.; data curation, N.U.; writing—original draft preparation, N.U.; writing—review and editing, N.U., I.D.F. and G.S.; supervision, I.D.F. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The source code implementing the proposed explainable multi-modal feature fusion framework is publicly available at: https://github.com/Engr-Naeem-Ullah/Explainable-Multimodal-Feature-Fusion (accessed on 5 October 2024). The datasets used in this study are publicly available benchmark datasets and can be accessed via Kaggle.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Future Artificial Intelligence Research (FAIR) project (PE0000013—CUP B53C22003630006), Spoke 3—Resilient AI, within the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR) of the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR); and the Digital-Driven Diagnostics, Prognostics, and Therapeutics for Sustainable Health Care (D34Health) project (PNC0000001—CUP B83C22006120001), within the National Plan for investments complementary to the PNRR, financed by the European Union.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Qayyum, H.; Rizvi, S.T.H.; Naeem, M.; Khalid, U.B.; Abbas, M.; Coronato, A. Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy for Skin Cancer and COVID-19 Detection: A Comparative Study Using a Stacked Ensemble Method. Technologies 2024, 12, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, N.; Khan, J.A.; De Falco, I.; Sannino, G. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: Importance, Use Domains, Stages, Output Shapes, and Challenges. ACM Comput. Surv. 2024, 57, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, W.R. Shape and texture. In Quantitative MRI of the Brain: Measuring Changes Caused by Disease; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 559–579. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.; Wechsler, H. Independent component analysis of Gabor features for face recognition. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2003, 14, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ojala, T.; Pietikainen, M.; Maenpaa, T. Multiresolution gray-scale and rotation invariant texture classification with local binary patterns. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 971–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AbuRass, S.; Huneiti, A.; Al-Zoubi, M.B. Enhancing convolutional neural network using Hu’s moments. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalal, N.; Triggs, B. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05), San Diego, CA, USA, 20–25 June 2005; Volume 1, pp. 886–893. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, N.; Javed, A. Deep Features Comparative Analysis for COVID-19 Detection from the Chest Radiograph Images. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Frontiers of Information Technology (FIT), Islamabad, Pakistan, 13–14 December 2021; pp. 258–263. [Google Scholar]

- Rundo, L.; Militello, C. Image biomarkers and explainable AI: Handcrafted features versus deep learned features. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2024, 8, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?”: Explaining the Predictions of Any Classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, A.D.; Zare, M.R.; Fermi, P.M. Medical image classification: A comparison of various handcrafted features. Int. J. Adv. Soft Comput. Appl 2019, 11, 24–39. [Google Scholar]