Abstract

Background: Burn patients can suffer prolonged hospital stays, infections, and wound breakdown. Given the complexity of burns, it is often difficult to determine which underlying factors contribute to complications. The Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) is the largest database of burn patients globally available, and it accounts for underlying or coinciding disease conditions present in burn patients. Muscle wasting conditions, such as sarcopenia, cachexia, and protein malnutrition, are suspected of causing worse outcomes. Prior analysis of BCQP data (2000–2017) demonstrated that patients with muscle wasting had prolonged hospitalization and adverse outcomes. Methods: Building on our previous work, we extended logistic regression analysis to BCPQ data through 2022 to assess whether reporting and outcomes had changed. Results: Updated BCQP data demonstrated a statistically significant increase in mortality in cachexia vs. non-muscle wasting patients (Odds Ratio [OR]: 2.2 [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.3–3.7], p = 0.004), but no increase in mortality was seen with protein malnutrition (OR: 1.1 [95% CI: 0.93–1.35], p = 0.239). However, the diagnosis rate of muscle wasting conditions decreased by 53% since the previous analysis, suggesting a potential under-reporting of these diagnoses in BCQP patients. Conclusions: Burn care could be augmented by better diagnosis of underlying conditions that predispose to muscle wasting.

1. Introduction

Burn injuries are among the most severe types of traumas, causing around 180,000 deaths annually worldwide from fires alone [1,2,3,4]. One of the greatest sources of morbidity in patients with severe burns, such as those covering > 30% of the total body surface area (TBSA), is hypermetabolism [5,6,7]. Hypermetabolism after burns is characterized by an elevated metabolic rate that can significantly deplete muscle protein [5,8]. In this state of hypermetabolism, patients often experience a profound proteolysis of muscle contractile proteins to generate gluconeogenic substrates to support the increased energy demands experienced by these individuals [9]. This skeletal muscle loss has profound long-term consequences, such as impaired mobility, chronic immunosuppression, and endocrine dysregulation [5,6,7,8,9].

Compounding the complex changes in metabolism from the burn itself are other types of preexisting muscle wasting, which are likely overlooked as a source of morbidity in the burn population [1]. Protein malnutrition, one cause of muscle wasting, is defined as a deficiency in dietary protein intake that leads to inadequate synthesis of muscle as well as weakened immunity and healing capacity [10]. Moreover, cachexia, the depletion of muscle with or without reduction in fat mass, is caused by underlying chronic illnesses, such as cancer or autoimmune disease [10]. Finally, sarcopenia, an additional muscle wasting condition, is commonly defined as the loss of muscle that results from the aging process rather than lack of protein calorie intake or an underlying illness [1,11]. In this analysis, each condition was defined strictly by its ICD coding criteria (Table A1): protein malnutrition = E43–E46; cachexia = R64; sarcopenia = M62.50. No laboratory thresholds were applied because such parameters are not available in the BCQP. While clinical overlap is recognized, the use of ICD-based definitions provides a standardized and reproducible approach for distinguishing these conditions in large-scale datasets. What impact these distinct causes of muscle wasting have on the treatment trajectory of burn patients is unclear.

Previously, the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP), the largest available global dataset of burn patients, was analyzed using data available from 2000 to 2017 to try to define the role of muscle wasting conditions in burn outcomes [1]. In this analysis, muscle wasting was defined as all available diagnoses within the International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes linked to muscle wasting, including protein malnutrition, cachexia, and sarcopenia. These conditions were found to be significant risk factors for a number of adverse clinical outcomes, including increased number of surgical procedures, longer hospital stays, and need for discharge to an assisted living facility rather than to home independent living [1].

However, in this earlier database analysis, muscle wasting was not found to be clinically significant in predicting mortality after adjusting for other confounding conditions, such as age, inhalation injury, and size of burn [1]. Additionally, only 2.6% of the patients were diagnosed with any type of preexisting muscle wasting condition, such as protein malnutrition, cachexia, and sarcopenia. Given the evolving awareness of these conditions and the fact that these rates were below baseline population rates, it was suspected that these conditions may have been under-reported, despite their clinical significance. With increased availability of data from the updated BCQP, which enrolled additional patients from 2017 to 2022, we sought to investigate whether or not attention to muscle wasting conditions had changed amongst burn clinicians and whether or not these conditions continued to play an important role in key clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

The analysis was performed after approval from the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board under protocol #00416807. The BCQP was used to stratify patients into groups with “Sarcopenia,” “Cachexia,” and “Protein Malnutrition” using ICD codes (see Table A1). A patient group combining these diagnoses, called the “muscle wasting” group, was also created, similar to prior analysis [1]. Patients who had more than one muscle wasting condition were only counted once in the “muscle wasting” group. In the BCQP, ICD codes do not have an associated timing of diagnosis, making it difficult for the user to distinguish whether or not a given muscle wasting condition is preexisting or acquired during the acute stay of his or her burn care. The most recent BCQP was used to analyze the impact of these conditions on burn outcomes, which included patients from 2000–2022. Although ICD-10-CM codes were nationally implemented in 2015, the specific code for sarcopenia (M62.84) was introduced in 2016, and documentation of sarcopenia and cachexia (R64) appears in later BCQP records. Because earlier years showed minimal or inconsistent coding for these diagnoses, we limited muscle wasting analyses to 2017–2022 while retaining the full 2000–2022 BCQP cohort for context. Some patients with undiagnosed or miscoded muscle wasting conditions before 2017 were likely categorized in the non-muscle wasting group, reflecting under-recognition of these diagnoses during earlier registry years.

Similar to the previous analysis, the primary outcome of this study was mortality, and secondary outcomes included likelihood of being discharged home to independent living (rather than discharged to skilled nursing facility, long-term care facility, home with supportive nursing care, or death), development of sepsis, wound infection and/or skin graft failure during the acute burn treatment phase, as well as length of inpatient stay, length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay, length of ventilator support, and total number of skin debridement procedures required during acute burn care. Sepsis was defined using ICD codes as specified in Table A2. To enhance transparency and allow reproducibility of our methodology, extended variable definitions, coding criteria, and supplementary analyses are provided in the Appendix A. Only material essential for interpretation of the primary and secondary outcomes has been retained within the manuscript, while additional non-essential tables are available online for readers who wish to examine the dataset in greater depth.

Statistical Analysis

Linear plots were used to track the number of patients diagnosed with a muscle wasting-associated disease by year. Data collection, organization, and graph creation were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Office Home and Student, 2019). Descriptive statistics were analyzed by first assessing for normal distribution of continuous variables with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Normally distributed data were described as means and standard deviations, whereas non-normally distributed data were described with medians and interquartile ranges (IQR). Comparisons for the muscle wasting groups and patients who did not have muscle wasting diagnoses were performed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests for normally distributed data and Kruskal–Wallis tests for non-normally distributed data. Chi-squared tests were used to compare categorical data.

If adequate data were available for regression analysis by specific type of muscle wasting condition, then analysis was performed by specific condition (sarcopenia, protein malnutrition, or cachexia) to best determine the effect of the specific muscle wasting conditions on clinical outcomes. Linear regression was performed for continuous outcomes and binomial logistic regression was performed for categorical outcomes. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 29.0.2.0).

Inclusion criteria comprised all BCQP patients with available demographic, injury, and outcome data between 2000 and 2022. Patients with incomplete data were handled using pairwise deletion, consistent with BCQP registry practice. Diagnoses were identified by ICD-9/10 codes (Table A1 and Table A2). No matching was performed, as the analysis aimed to evaluate unadjusted population level associations across the entire cohort. Adjustment for multiple comparisons was not applied because each outcome represented a separate clinical endpoint.

Incomplete data were analyzed using pairwise deletion. Confounding variables were evaluated for potential inclusion in models using Pearson correlations. Variables were considered if correlation coefficients were |>0.1| and a Variance Inflation Factor < 10 to eliminate collinearity. Models were assessed for statistical significance with analysis of variance (ANOVA) for linear regression and Chi-Square Omnibus Test for binomial logistic regression. Statistical significance was set at an alpha of 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

The BCQP represented a total number of 284,194 burn patients between 2000 and 2022. A total of 3284 (1.2%) of these patients fit the stated criteria for “muscle wasting” with a diagnosis of either sarcopenia, cachexia, or protein malnutrition. All patients with muscle wasting were diagnosed between the years of 2017 and 2022. Apparent absence of cases from 2013 to 2016 likely reflects limited adoption of muscle wasting ICD codes within the BCQP during the early ICD-10 transition period, rather than a true lack of such patients. Reporting frequency for cachexia and protein-malnutrition codes increased steadily after 2016, consistent with broader national reporting of these diagnostic codes.

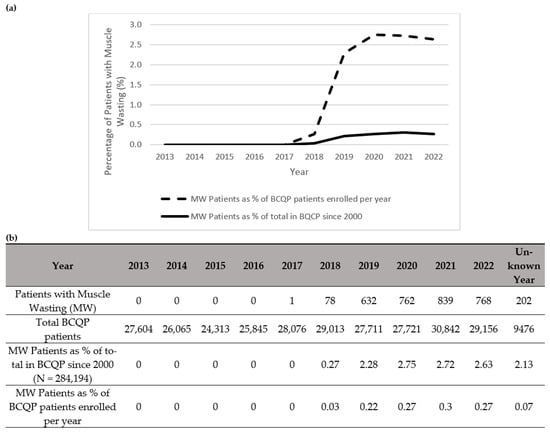

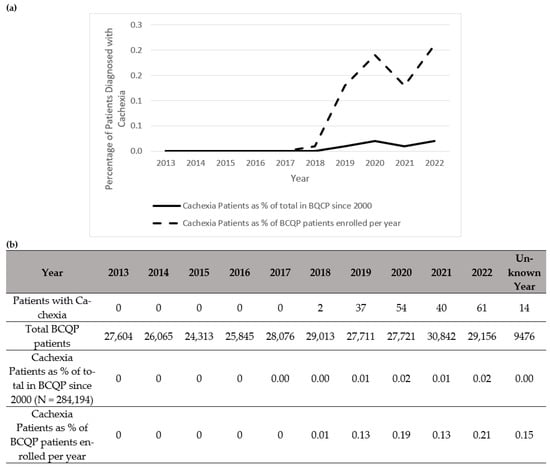

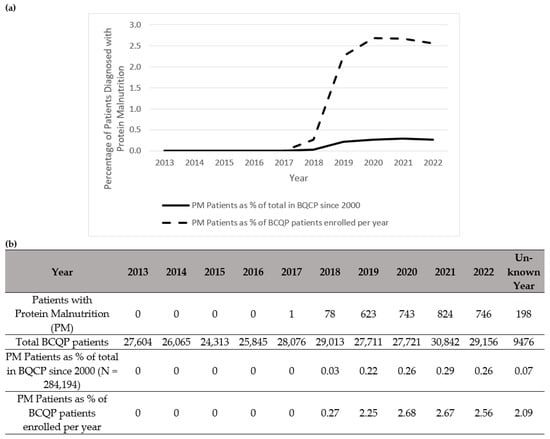

Notably, there was a total increase per year in the diagnoses of muscle wasting (Figure 1), cachexia (Figure 2), and protein malnutrition (Figure 3) during the years 2017 to 2019, but these rates did not increase as a percentage of total annual patients enrolled in the BCQP. This classification was based on ICD codes for sarcopenia (n = 4, 0.001%), cachexia (n = 209, 0.07%), or protein malnutrition (n = 3215; 1.12%). A total of 144 patients had two or more concurrent muscle wasting diagnoses. Only four patients in the BCQP were diagnosed with sarcopenia—one each in 2019 and 2022, and two with unspecified diagnosis years. Comparisons of the sarcopenia patients were not statistically or clinically meaningful and are listed in Table A3 for reference but were excluded from further analysis.

Figure 1.

Summary of patients in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) diagnosed with muscle wasting (a) graphically between 2013 and 2022 and (b) by year, expressed as a percentage of the total number of BCQP patients enrolled since 2000 and for each individual year. For the purposes of this analysis, “muscle wasting” is comprised of International Classification Disease (ICD) codes associated with “sarcopenia,” “cachexia,” and “protein malnutrition” (See Table A1).

Figure 2.

Summary of patients in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) diagnosed with cachexia (a) graphically between 2013 and 2022 and (b) by year, expressed as a percentage of the total number of BCQP patients enrolled since 2000 and for each individual year.

Figure 3.

Summary of patients in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) diagnosed with protein malnutrition (a) graphically between 2013 and 2022 and (b) by year, expressed as a percentage of the total number of BCQP patients enrolled since 2000 and for each individual year.

Patients with muscle wasting were significantly older (sarcopenia: 56.5 years [IQR: 35.5–70.8], cachexia: 63.0 years [IQR: 52.0–72.0], protein malnutrition: 57.0 years [IQR: 41.0–68.0], Table 1) vs. non-muscle wasting patients (37.0 years [IQR: 19.0–56.0]; p < 0.001). Additionally, patients with muscle wasting conditions had larger TBSA burns (sarcopenia: 27.0% [IQR: 14.5–46.0%], cachexia: 4.0% [IQR 1.5–13.8%], protein malnutrition 9.0% [IQR: 2.0–24.9%]) compared to non-muscle wasting patients (2.0% [IQR: 0.0–6.0%]; p < 0.001). Furthermore, muscle wasting patients were more likely to be female (protein malnutrition 36.2% female vs. non-muscle wasting 33.8%, p = 0.005), more likely to be unemployed (cachexia: 87.5%, protein malnutrition: 67.2% vs. non-muscle wasting: 43.3%, p < 0.001], and more likely to live alone (cachexia: 39.6%, protein malnutrition: 34.5% vs. non-muscle wasting: 22.4%, p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between cohorts in terms of race, marital status, burn mechanism, insurance status, and rates of most medical comorbidities (Table A3).

Table 1.

Abbreviated comparison between patients diagnosed with different muscle wasting conditions in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) based on demographics, burn characteristics, and outcomes from 2000–2022. BCQP ICD codes do not have an associated timing of diagnosis.

Regression analysis with data collected from cachectic patients demonstrated that cachexia significantly predicted a higher likelihood of mortality (Odds Ratio (OR) 2.2 [95% Confidence Interval (CI): 1.3–3.7], p = 0.004, Table 2). In contrast, protein malnutrition was not associated with increased mortality (OR 1.12 [95% CI: 0.93–1.35], p = 0.239, Table 2). Meanwhile, muscle wasting conditions were significantly associated with decreased likelihoods of being discharged home to independent living (cachexia: OR 0.3 [95% CI: 0.2–0.5], protein malnutrition: OR 0.4 [95% CI: 0.4–0.5]; p < 0.0001 for both, Table 3).

Table 2.

Likelihood of mortality in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table 3.

Likelihood of discharge home to independent living vs. other location or circumstances in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Additionally, patients with muscle wasting conditions were at higher risk of developing sepsis (cachexia: OR 16.2 [95% CI: 10.8–24.3]; protein malnutrition: OR 16.2 [95% CI: 14.3–18.4], p < 0.0001 for both, Table 4) and wound infection/skin graft loss (cachexia: OR 2.6 [95% CI: 1.3–5.5], p = 0.01; protein malnutrition: OR 3.5 [95% CI: 2.9–4.2], p < 0.0001, Table 5). Patients with protein malnutrition had a significantly higher risk of requiring more skin debridement procedures compared to patients without muscle wasting (OR 16.8 [95% CI: 6.3–27.3], p = 0.002, Table 6), but this association was not evident in patients diagnosed with cachexia (OR 15.0 [95% CI: −25.7–55.7], p = 0.470, Table 6). Patients with cachexia and protein malnutrition were more likely to have longer hospital stays (cachexia: OR 11.2 [95% CI: 8.4–14.1], protein malnutrition (OR 13.4 [95% CI: 12.7–14.2]; both p < 0.0001) compared to non-muscle wasting patients (Table 7). Moreover, patients with muscle wasting conditions had increased risk of longer ICU stays and days requiring ventilator support that reached statistical significance (p < 0.0001 for all, see Table A4 and Table A5).

Table 4.

Likelihood of developing sepsis during acute burn treatment in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table 5.

Likelihood of developing a wound infection and/or graft loss during acute burn treatment in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table 6.

Likelihood of skin debridement procedures required during acute burn care for Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table 7.

Likelihood of increased total length of inpatient stay for Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

4. Discussion

In 2019, the American Burn Association (ABA) launched the BCQP, integrating data from the original National Burn Repository database and the Burn Quality Improvement Program into one entity, the largest database of burn patients to date [12]. With the updated version of the BCQP that included increased patient enrollment from 2017–2022, a more powerful statistical analysis was performed with this larger population to better understand how muscle wasting conditions may affect outcomes for burn patients. Increasing the number of patients included had the potential to reduce selection bias when analyzing the effects of preexisting muscle wasting conditions on burn outcomes. However, the proportion of patients diagnosed with muscle wasting conditions reduced from 2.6% to 1.2%, either representing a true decrease in the number of patients with these diagnoses or an extrapolation of the selection bias from the previous database. Understanding how preexisting muscle wasting influences infection risk, wound healing, ventilator dependence, and mortality can guide earlier nutritional and rehabilitative interventions in burn management.

Interestingly, there are several reasons why the lack of patients diagnosed with muscle wasting conditions in the BCQP does not reflect a true decrease in the incidence of these conditions. The percentage of patients in the latest BCQP aged 65 or older is 14%, where the baseline incidence of sarcopenia is estimated to be between 5–22% [11,13,14,15]. Therefore, the expected incidence of sarcopenia in the BCQP would be 0.7–3%; however, with only four patients being diagnosed with sarcopenia (<0.001%) in this database, this lower rate likely reflects lack of reporting of this diagnosis. Moreover, “sarcopenia” is a relatively new ICD-10-CM code proposed in 2016, and according to the definition, there are varying rates of incidence [16]. Moreover, the definition was updated in 2019 by the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP) [15,17]. Since this diagnosis is associated with a newer concept of muscle atrophy with aging, this condition may be under-recognized in the burn patient populations enrolled in the BCQP. Since elderly patients are disproportionately affected by major burns, increasing awareness of sarcopenia could help with more accurate assessment of its impact on outcomes that are particularly important in the care of elderly burn patients, such as mortality and discharge to home independent living [18,19,20].

An observed uptick in the diagnoses of cachexia and protein malnutrition during 2017 to 2019 may reflect the adoption of more structured approaches to malnutrition screening, diagnosis, and documentation. For example, the Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative (MQii), a national effort led by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics and Avalere Health, disseminated quality measures and best practices aimed at improving the recognition and management of malnutrition, especially in hospitalized and older adult populations [21]. This initiative encouraged clinical assessments, such as reduced muscle mass and functional decline, with the diagnosis of malnutrition, thereby potentially increasing the number of patients diagnosed with this condition. Additionally, efforts to integrate malnutrition risk identification into electronic health records (EHRs), Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services quality reporting programs, and transitional care models likely increased clinician awareness and coding accuracy [22]. As noted in a 2018 national dialogue hosted by the Malnutrition Quality Collaborative, malnutrition was historically under-recognized during transitions across care settings, despite its strong association with increased healthcare costs, complications, and mortality [23]. This meeting spurred actionable recommendations, such as adopting standardized malnutrition terminology in EHRs, educating clinicians on functional aspects of nutrition, and aligning reimbursement models with nutrition care delivery, which may have accelerated institutional efforts to identify and document malnutrition more rigorously.

Despite the raw increase in the number of patients diagnosed with cachexia and protein malnutrition after 2017, this analysis demonstrated a stable rate of these diagnoses as a percentage of annual enrollment since 2017. Moreover, there was an overall decrease in the number of patients with muscle wasting conditions as a total of the BCQP. As previously noted, the BCQP database does not require patients with less than 10% TBSA to provide a complete report of preexisting ICD diagnoses, compounding selection bias from those who are enrolled that have smaller TBSAs [1]. Additionally, it is likely that the rate of diagnoses of cachexia and protein malnutrition was still proportionally lower than the overall enrollment in burn patients to the BCQP. Therefore, despite the improvement in reporting of these conditions with increased awareness, the overall proportion of patients with these muscle wasting conditions was lower in this newer dataset compared to the previous dataset. This decrease also coincides with recommendations to start enteral nutrition within the first 4–6 h post-injury and a move toward volume-based feeding, which may also influence diagnosis rates [24,25].

Despite the low incidence of muscle wasting conditions among patients in the BCQP, this analysis examines the distinctions between two types of muscle wasting: cachexia and protein malnutrition. These two subtypes negatively contributed to a variety of clinical outcomes. Unlike previous analysis, preexisting cachexia was a significant mortality predictor in burn patients (OR 2.2, p = 0.004). With increased power in this newer analysis, these results suggest that cachexia may present a more immediate risk to survival rates in patients with large burns, perhaps explained by previous findings of impaired immune responses and wound healing [8]. However, this effect was not present with protein malnutrition. At present it is unclear whether there may be additional impacts of cachexia from underlying illnesses that predispose patients to mortality that are not present in patients who have sarcopenia or protein malnutrition. Additional enrollment is needed to adequately power the analysis to demonstrate the true effects of cachexia as well as sarcopenia and protein malnutrition.

Conversely, both cachexia and protein malnutrition had statistically significant impacts on most other clinical outcomes, such as likelihood to discharge home to independent living, sepsis, wound infection, and length of stay. When comparing the OR of outcomes between protein malnutrition and cachexia, there was a more pronounced effect on almost all outcomes from protein malnutrition, rather than cachexia. Sepsis is a major complication in burn patients, and cachexia and protein malnutrition were associated with an increase in sepsis development. Previous studies have also noted the persistence of muscle catabolism after severe burns and the patients’ resulting inability to fight infections, leading to complications such as sepsis [26]. In addition, patients with cachexia and protein malnutrition spent significantly more time in the hospital and ICU and on ventilator support compared to those without these conditions, similar to observations in our previous study [1].

These differences are consistent with the underlying biology of muscle wasting syndromes. Protein-calorie malnutrition reflects acute substrate deficiency in the setting of the burn hypermetabolic response, which intensifies catabolism and impairs wound healing, immune function, and respiratory muscle performance, mechanisms that could plausibly lengthen ICU and hospital stay and increase ventilator days. Cachexia, by contrast, is a chronic, disease-related inflammatory state with progressive muscle loss and altered energy metabolism; its association with mortality can be strong even when effects on hospital or ICU utilization appear smaller. Differences in inflammatory milieu, substrate availability, and respiratory muscle function therefore provide a coherent physiologic rationale for the effect patterns observed here [27]. Future studies incorporating functional and biochemical markers (e.g., handgrip strength, DXA/ultrasound, serum proteins, inflammatory cytokines) are needed to test these mechanisms directly.

Importantly, the BCQP does not report many metrics assessing the severity of preexisting muscle wasting. Standard clinical assessments, such as imaging (e.g., DXA, ultrasound, or MRI) or proxy measures from laboratory values such as creatinine, have not been widely adopted by burn care providers. Additionally, the ICD codes that the patients are diagnosed with do not have an associated timing of diagnosis, making it difficult for the user to distinguish whether or not a given muscle wasting condition is preexisting or acquired during the acute stay of his or her burn care. For some terms, such as “sarcopenia” or “cachexia,” there is an association of chronicity which implies that the conditions are preexisting; however, with “protein malnutrition,” it is unclear if this condition is due to effects from burn hypermetabolism or preexisting factors unrelated to the burn injury. One way to improve this distinction would be to introduce burn hypermetabolism as an ICD code and use specific criteria to define the severity of both the burn hypermetabolism and pre-admission muscle wasting.

More thorough assessment of muscle wasting disease in burn patients would likely result in more accurately diagnosis of underlying causes of muscle loss, whether due to sarcopenia, cachexia, protein malnutrition, or other types of muscle loss, such as hypermetabolism. Additional study with integration of more of these clinical measures, particularly with objective measurements of muscle strength, would be needed to more accurately assess the true impact of these conditions on healing in burn patients. These data would provide additional information for distinguishing the physiological differences in these types of muscle wasting, which could better establish which aspects of muscle wasting predispose to the greatest morbidity. Ultimately, improving the understanding of how muscle wasting conditions affect burn recovery is one way to optimize interventions to reduce muscle loss and improve clinical outcomes in these patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The BCQP does not specify the timing or chronicity of muscle wasting diagnoses, preventing differentiation between preexisting and burn-acquired malnutrition. Underreporting and inconsistent coding likely reduced the apparent prevalence of muscle wasting conditions, particularly before 2017. Residual confounding is possible, as regression models lacked matching or comprehensive adjustment for comorbidities. Objective measures of muscle mass or function (such as DXA, ultrasound, or handgrip strength) are unavailable in the BCQP, limiting physiologic interpretation. Finally, excluding pre-2017 patients with potential unrecorded muscle wasting may have introduced selection bias. These factors should be considered when interpreting the findings.

5. Conclusions

In the BCQP, the largest database of burn patients available, patients with muscle wasting conditions, such as sarcopenia, cachexia, and protein malnutrition, were analyzed to better understand the reporting of these conditions and their impacts on burn outcomes. The overall proportion of patients diagnosed with muscle wasting conditions decreased with the newer database (1.2% vs. 2.6%). While the incidence of cachexia and protein malnutrition reporting increased in 2017, the prevalence stabilized in ensuing years at a rate that is lower than what would be expected from baseline population values, while sarcopenia remains essentially unreported. Despite the low prevalence of these conditions, cachexia and/or protein malnutrition were associated with poorer outcomes for burn patients including mortality, infection rate, and hospital stay length, suggesting that these conditions are critical to optimizing care for burn patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: E.B., A.J.M. and J.C.; Methodology: E.B. and A.J.M.; Software: E.B.; Validation: J.G., S.S. and K.K.; Formal Analysis: E.B.; Investigation: E.B.; Resources: E.B., A.J.M. and J.C.; Data Curation: E.B.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation: J.G., S.S. and K.K.; Writing—Review and Editing: E.B., A.J.M. and J.C.; Visualization: E.B.; Supervision: A.J.M. and J.C.; Project Administration: E.B.; Funding Acquisition: E.B. and J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a gift from the Reading Hospital Foundation awarded to the Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Reading Hospital–Tower Health in March 2025.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins University (protocol code 00416807 on 1 February 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study during initial enrollment in the BCQP. As a de-identified database, informed consent was not required for this study.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) data. Data were obtained from the American Burn Association (ABA) and are available at https://ameriburn.org/quality-care/burn-care-quality-platform-bcqp-registry/bcqp-full-registry/ (accessed on 30 March 2025) with the permission of the ABA. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Katharine Sharpe for editing and formatting the manuscript and the Reading Hospital Foundation for their support in purchasing the BCQP for this analysis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABA | American Burn Association |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| BCQP | Burn Care Quality Platform |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| DXA | Dual-Energy X-ray Absorptiometry |

| EHR | Electronic Health Record |

| EWGSOP | European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People |

| ICD | International Classification of Disease |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IQR | Interquartile Ranges |

| MQii | Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative |

| MRI | Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| TBSA | Total Body Surface Area |

Appendix A

Table A1.

International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes used to define muscle wasting in this study.

Table A1.

International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes used to define muscle wasting in this study.

| Diagnosis | ICD-9 Code | ICD-10 Code |

|---|---|---|

| Sarcopenia (Muscular wasting and disuse atrophy, not elsewhere classified) | 728.2 | M62.50 |

| Muscle Cachexia (Wasting Syndrome) | 261 | R64 |

| Protein malnutrition (Other severe protein-calorie malnutrition & other/ unspecified protein calorie malnutrition) | 262, 263 (263.1, 263.2, 263.8, 263.9) | E43, E44, E45, E46, E64 |

Table A2.

International Classification Diagnostic (ICD) codes used to diagnose sepsis in muscle wasting patients from the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) database.

Table A2.

International Classification Diagnostic (ICD) codes used to diagnose sepsis in muscle wasting patients from the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) database.

| ICD-10 CODE | Diagnosis Description |

|---|---|

| A427 | ACTINOMYCOTIC SEPSIS |

| P369 | BACTERIAL SEPSIS OF NEWBORN UNSPECIFIED |

| B377 | CANDIDAL SEPSIS |

| A5486 | GONOCOCCAL SEPSIS |

| A4150 | GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS UNSPECIFIED |

| P368 | OTHER BACTERIAL SEPSIS OF NEWBORN |

| A4159 | OTHER GRAM-NEGATIVE SEPSIS |

| A4189 | OTHER SPECIFIED SEPSIS |

| A408 | OTHER STREPTOCOCCAL SEPSIS |

| O85 | PUERPERAL SEPSIS |

| A021 | SALMONELLA SEPSIS |

| A414 | SEPSIS DUE TO ANAEROBES |

| A4181 | SEPSIS DUE TO ENTEROCOCCUS |

| A4151 | SEPSIS DUE TO ESCHERICHIA COLI [E. COLI] |

| A413 | SEPSIS DUE TO HEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE |

| A4102 | SEPSIS DUE TO METHICILLIN RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS |

| A4101 | SEPSIS DUE TO METHICILLIN SUSCEPTIBLE STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS |

| A411 | SEPSIS DUE TO OTHER SPECIFIED STAPHYLOCOCCUS |

| A4152 | SEPSIS DUE TO PSEUDOMONAS |

| A4153 | SEPSIS DUE TO SERRATIA |

| A410 | SEPSIS DUE TO STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS |

| A400 | SEPSIS DUE TO STREPTOCOCCUS GROUP A |

| A401 | SEPSIS DUE TO STREPTOCOCCUS GROUP B |

| A403 | SEPSIS DUE TO STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE |

| A412 | SEPSIS DUE TO UNSPECIFIED STAPHYLOCOCCUS |

| T8144XA | SEPSIS FOLLOWING A PROCEDURE INITIAL ENCOUNTER |

| O8604 | SEPSIS FOLLOWING AN OBSTETRICAL PROCEDURE |

| O0387 | SEPSIS FOLLOWING COMPLETE OR UNSPECIFIED SPONTANEOUS ABORTION |

| P362 | SEPSIS OF NEWBORN DUE TO STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS |

| P360 | SEPSIS OF NEWBORN DUE TO STREPTOCOCCUS GROUP B |

| A419 | SEPSIS UNSPECIFIED ORGANISM |

| R652 | SEVERE SEPSIS |

| R6521 | SEVERE SEPSIS WITH SEPTIC SHOCK |

| R6520 | SEVERE SEPSIS WITHOUT SEPTIC SHOCK |

| A409 | STREPTOCOCCAL SEPSIS UNSPECIFIED |

Table A3.

Abbreviated comparison between patients diagnosed with different muscle wasting conditions in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) from 2000–2022 based on demographics, burn characteristics, and outcomes.

Table A3.

Abbreviated comparison between patients diagnosed with different muscle wasting conditions in the Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) from 2000–2022 based on demographics, burn characteristics, and outcomes.

| Variable | Diagnosis of Sarcopenia (N = 4) | Diagnosis of Cachexia (N = 209) | Diagnosis of Protein Malnutrition (N = 3215) | No Diagnosis of Muscle Wasting (N = 284,194) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| Age | 56.5 (35.5–70.75) | 63 (52–72) | 57 (41–68) | 37 (19–56) | <0.001 |

| Total Body Surface Area (%) | 27 (14.5–46) | 4 (1.5–13.8) | 9 (2–24.875) | 2 (0–6) | <0.001 |

| Year of Injury | 2020.5 (2019.75–2021.25) | 2021 (2020–2022) | 2021 (2020–2021) | 2018 (2015–2020) | <0.001 |

| % Female | (0/4) 100% | (71/209) 34% | (1162/3214) 36% | (95,641/282,949) 33.8% | 0.307 |

| Distribution By Race | |||||

| % White Race | (3/4) 75% | (154/205) 74.4% | (1947/3165) 61.5% | (162,334/272,200) 59.6% | 0.652 |

| % Black Race | (0/4) 0% | (34/207) 16.4% | (742/3165) 23.4% | (57,794/272,200) 21.2% | 0.585 |

| % Asian Race | (0/4) 0% | (6/207) 2.9% | (49/3165) 1.5% | (6790/272,200) 2.5% | 0.904 |

| % American Indian/Alaskan Native Race | (0/4) 0% | (1/207) 0.5% | (42/3165) 1.3% | (2308/272,200) 0.8% | 0.966 |

| % Other Race | (1/4) 25% | (12/207) 5.8% | (385/3165) 12.2% | (42,974/272,200) 15.8% | 0.496 |

| % Unknown Race | (0/4) 0% | (2/209) 1.0% | (50/3215) 1.6% | (10,994/272,200) 3.9% | 0.854 |

| Living Characteristics | |||||

| % Unemployed Status | (1/1) 100% | (56/64) 87.5% | (415/618) 67.2% | (31,825/73,526) 43.3% | <0.001 |

| % Single Status | (1/4) 25% | (93/198) 47.0% | (1548/3055) 50.7% | (113,495/181,032) 62.7% | <0.001 |

| % Married Status | (1/4) 25% | (50/198) 25.3% | (895/3055) 29.3% | (51,558/181,032) 28.5% | 0.678 |

| % Divorced Status | (1/4) 25% | (29/198) 14.6% | (385/3055) 12.6% | (10,869/181,032) 6.0% | <0.001 |

| % Widowed Status | (1/4) 25% | (26/198) 13.1% | (227/3055) 7.4% | (5110/181,032) 2.8% | <0.001 |

| % Living Alone Status | (1/4) 25% | (76/192) 39.6% | (1013/2937) 34.5% | (39,310/181,032) 22.4% | <0.001 |

| % Living in Own Home/Apartment | (4/4) 100% | (168/199) 84.4% | (2739/3107) 88.2% | (181,934/192,036) 94.7% | 0.802 |

| % Living in Group Home | (0/4) 0% | (9/199) 4.5% | (104/3107) 3.3% | (2401/192,036) 1.3% | 0.950 |

| % Homeless | (0/4) 0% | (20/199) 10.1% | (248/3107) 8.0% | (6775/192,036) 3.5% | <0.001 |

| % From Prison/Correctional Institution | (0/4) 0% | (2/199) 1.0% | (16/3107) 0.5% | (926/192,036) 0.5% | 0.889 |

| Burn Characteristics | |||||

| % Inhalation Injury Present | (1/2) 50% | (22/193) 11.4% | (381/2659) 14.3% | (19,985/275,626) 7.3% | <0.001 |

| % Developed Compartment Syndrome | (0/4) 0% | (1/209) 0.5% | (10/3215) 0.3% | (188/283,194) 0.1% | 0.997 |

| Carboxyhemoglobin Level at Admission | Insufficient Data | 2.45 (1.125–4.375) | 2 (1–5.175) | 2.4 (1.2–5.1) | <0.001 |

| % Flame Etiology | (3/4) 75% | (110/192) 57.3% | (1412/2882) 49.0% | (102,457/255,594) 40.1% | 0.309 |

| % Scald Etiology | (0/4) 0% | (18/192) 9.4% | (348/2882) 12.1% | (85,153/255,594) 33.3% | <0.001 |

| % Contact Etiology | (0/4) 0% | (16/192) 8.3% | (191/2882) 6.6% | (27,334/255,594) 10.7% | <0.001 |

| % Electric Etiology | (0/4) 0% | (2/192) 1.0% | (42/2882) 1.5% | (7542/255,594) 3.0% | <0.001 |

| % Miscellaneous Etiology (Cold, Radiation, Friction) | (1/4) 25% | (46/192) 24.0% | (889/2882) 30.8% | (33,108/255,594) 13.0% | <0.001 |

| Number of Days between Admission to Burn Center and First Procedure | 2 (1–3.5) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| Number of Days between Injury and First Procedure | 8.5 (0–47.5) | 3 (1–8) | 3 (1–8) | 1 (0–4) | <0.001 |

| Insurance Characteristics | |||||

| % MediCAID Insured | (0/4) 0% | (63/204) 30.9% | (785/3169) 24.8% | (83,041/269,964) 30.8% | <0.001 |

| % MediCARE Insured | (2/4) 50% | (104/204) 51.0% | (1269/3169) 40.0% | (43,701/269,964) 16.2% | <0.001 |

| % Miscellaneous Insured | (0/4) 0% | (6/204) 2.9% | (131/3169) 4.1% | (11,834/269,964) 4.4% | 0.836 |

| % Private/ Commercial Insured | (1/4) 25% | (11/204) 5.4% | (563/3169) 17.8% | (94,211/269,964) 34.9% | <0.001 |

| % Self-Pay/Charity Care | (1/4) 25% | (20/204) 9.8% | (421/3169) 13.3% | (37,177/269,964) 13.8% | 0.447 |

| Comorbidity Characteristics | |||||

| % History of Severe Alcohol Abuse +/− Cirrhosis | (0/4) 0% | (29/209) 13.9% | (352/3215) 10.9% | (13,056/283,194) 4.6% | <0.001 |

| % History of Psychiatric Disorder | (0/4) 0% | (33/209) 15.8% | (410/3215) 12.8% | (21,780/283,194) 7.7% | <0.001 |

| % History of Neurological Disease | (0/4) 0% | (0/209) 0% | (0/3215) 0% | (1365/283,194) 0.5% | <0.001 |

| % History of Arthritis | (0/4) 0% | (8/209) 3.8% | (189/3215) 5.9% | (193/283,194) 5.9% | <0.001 |

| % History of Bleeding Disorder | (0/4) 0% | (5/209) 2.4% | (51/3215) 1.6% | (2771/283,194) 1.0% | <0.001 |

| % Received Chemotherapy Within 30 Days of Burn | (0/4) 0% | (7/209) 3.3% | (38/3215) 1.2% | (655/283,194) 0.2% | <0.001 |

| % History of Respiratory Disease | (0/4) 0% | (114/209) 54.5% | (1300/3215) 40.4% | (70,578/283,194) 24.9% | <0.001 |

| % History of Congenital Anomaly | (0/4) 0% | (2/209) 1.0% | (29/3215) 0.9% | (1457/283,194) 0.5% | 0.979 |

| % History of Major Cardiovascular Disease | (1/4) 25% | (21/209) 10.0% | (376/3215) 11.7% | (8435/283,194) 3.0% | <0.001 |

| % History of Connective Tissue Disorder | (0/4) 0% | (0/209) 0% | (0/3215) 0% | (394/283,194) 0.1% | 0.995 |

| % History of Hemodialysis | (0/4) 0% | (2/209) 1.0% | (83/3215) 2.6% | (1725/283,194) 0.6% | 0.975 |

| % History of Stroke | (0/4) 0% | (12/209) 5.7% | (190/3215) 5.9% | (3619/283,194) 1.3% | <0.001 |

| % History of Hypertension | (1/4) 25% | (75/209) 35.9% | (1414/3215) 44.0% | (52,620/283,194) 18.6% | <0.001 |

| % History of Immunodeficiency Disorder | (0/4) 0% | (5/209) 2.4% | (39/3215) 1.2% | (1298/283,194) 0.5% | <0.001 |

| % History of Diabetes Mellitus | (0/4) 0% | (30/209) 14.4% | (907/3215) 28.2% | (29,690/283,194) 10.5% | <0.001 |

| % History of Disseminated Cancer | (0/4) 0% | (7/209) 3.3% | (27/3215) 0.8% | (600/283,194) 0.2% | <0.001 |

| % History of Dementia | (0/4) 0% | (12/209) 5.7% | (134/3215) 4.2% | (1783/283,194) 0.6% | <0.001 |

| % History of Functional Dependence | (0/4) 0% | (32/209) 15.3% | (364/3215) 11.3% | (6604/283,194) 2.3% | <0.001 |

| % History of Obesity | (0/4) 0% | (5/209) 2.4% | (626/3215) 19.5% | (20,934/283,194) 7.4% | <0.001 |

| % History of Substance Abuse | (0/4) 0% | (49/209) 23.4% | (505/3215) 15.7% | (23,820/283,194) 8.4% | <0.001 |

| Outcomes | |||||

| % Mortality | (1/4) 25% | (35/206) 17.0% | (325/3189) 10.2% | (8708/280,966) 3.1% | <0.001 |

| % Discharge Home to Independent Living | (2/4) 50% | (57/206) 27.7% | (1317/3189) 41.3% | (213,716/280,966) 76.1% | <0.001 |

| % Sepsis Diagnosed After Burn Injury | (1/4) 25% | (69/209) 33% | (1072/3215) 33.3% | (3822/283,194) 1.3% | <0.001 |

| % Wound Graft Loss/Wound Infection | (1/4) 25% | (10/209) 4.8% | (257/3215) 8.0% | (4280/283,194) 1.5% | <0.001 |

| Number of Total Days Inpatient | 42 (29–57.5) | 14 (5–35) | 19 (8–37) | 4 (1–10) | <0.001 |

| Number of Total Days in Intensive Care | 36.5 (19.25–53.75) | 7 (2–24.5) | 10 (3–27) | 1 (0–4) | <0.001 |

| Number of Total Days on Ventilator | 2 (1–2) | 1 (0–5) | 3 (0–12) | 0 (0–0) | <0.001 |

| Number of Skin Debridement Procedures | 11 (8.5–21.5) | 4 (2–11) | 4 (2–9) | 2 (1–5) | <0.001 |

Table A4.

Likelihood of increased total length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay (in days) in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table A4.

Likelihood of increased total length of intensive care unit (ICU) stay (in days) in Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

| Likelihood of Increased Total Length of Intensive Care Unit Stay (Days) | |||||||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| (Constant) | −724.079 | 25.776 | −28.091 | <0.0001 | −774.600 | −673.559 | |

| Diagnosis of Cachexia | 5.525 | 1.373 | 0.010 | 4.025 | <0.0001 | 2.835 | 8.216 |

| Male Sex | −0.149 | 0.078 | −0.005 | −1.905 | 0.057 | −0.302 | 0.004 |

| Age in Years | 0.032 | 0.002 | 0.053 | 20.235 | <0.0001 | 0.029 | 0.035 |

| Total Body Surface Area (%) | 0.408 | 0.004 | 0.314 | 114.832 | <0.0001 | 0.401 | 0.415 |

| Inhalation Injury Present | 5.109 | 0.148 | 0.093 | 34.475 | <0.0001 | 4.819 | 5.400 |

| Year of Injury | 0.360 | 0.013 | 0.074 | 28.144 | <0.0001 | 0.335 | 0.385 |

| Diagnosis of Sepsis | 17.408 | 0.292 | 0.159 | 59.701 | <0.0001 | 16.837 | 17.980 |

| Likelihood of Increased Total Length of Intensive Care Unit Stay (Days) | |||||||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Diagnosis of Protein Malnutrition | 6.568 | 0.365 | 0.049 | 17.983 | <0.0001 | 5.852 | 7.284 |

| Male Sex | −0.138 | 0.078 | −0.005 | −1.766 | 0.077 | −0.291 | 0.015 |

| Age in Years | 0.031 | 0.002 | 0.051 | 19.417 | <0.0001 | 0.028 | 0.034 |

| Total Body Surface Area (%) | 0.405 | 0.004 | 0.312 | 114.112 | <0.0001 | 0.398 | 0.412 |

| Inhalation Injury Present | 5.123 | 0.148 | 0.094 | 34.607 | <0.0001 | 4.832 | 5.413 |

| Year of Injury | 0.342 | 0.013 | 0.070 | 26.676 | <0.0001 | 0.316 | 0.367 |

| Diagnosis of Sepsis | 16.186 | 0.299 | 0.148 | 54.054 | <0.0001 | 15.599 | 16.773 |

| Constant | −687.586 | 25.827 | −26.623 | <0.0001 | −738.207 | −636.965 | |

Table A5.

Likelihood of increased total length of ventilator support (in days) for Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

Table A5.

Likelihood of increased total length of ventilator support (in days) for Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) patients diagnosed with cachexia or protein malnutrition from 2000–2022.

| Likelihood of Increased Total Length of Ventilator Support (Days) | |||||||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Diagnosis of Cachexia | 3.385 | 0.930 | 0.009 | 3.639 | <0.0001 | 1.562 | 5.208 |

| Age in Years | 0.018 | 0.001 | 0.043 | 16.156 | <0.0001 | 0.016 | 0.020 |

| Total Body Surface Area (%) | 0.230 | 0.002 | 0.262 | 95.936 | <0.0001 | 0.225 | 0.235 |

| Inhalation Injury Present | 6.157 | 0.103 | 0.166 | 59.693 | <0.0001 | 5.955 | 6.359 |

| Flame Mechanism of Injury | 0.859 | 0.055 | 0.044 | 15.593 | <0.0001 | 0.751 | 0.967 |

| (Constant) | −0.524 | 0.049 | −10.730 | <0.0001 | −0.620 | −0.429 | |

| Likelihood of Increased Total Length of Ventilator Support (Days) | |||||||

| Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | t | Sig. | 95.0% Confidence Interval for B | |||

| B | Std. Error | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| Diagnosis of Protein Malnutrition | 6.724 | 0.239 | 0.073 | 28.106 | <0.0001 | 6.255 | 7.192 |

| Age in Years | 0.016 | 0.001 | 0.038 | 14.226 | <0.0001 | 0.013 | 0.018 |

| Total Body Surface Area (%) | 0.224 | 0.002 | 0.255 | 93.463 | <0.0001 | 0.219 | 0.229 |

| Inhalation Injury Present | 6.162 | 0.103 | 0.166 | 59.925 | <0.0001 | 5.961 | 6.364 |

| Flame Mechanism of Injury | 0.884 | 0.055 | 0.045 | 16.079 | <0.0001 | 0.776 | 0.991 |

| (Constant) | −0.496 | 0.049 | −10.177 | <0.0001 | −0.591 | −0.400 | |

References

- Blears, E.; Murton, A.; Caffery, J. The Influence of Muscle Wasting on Patient Outcomes Among Burn Patients: A Burn Care Quality Platform Study. J. Burn Care Res. 2025, 46, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsome, T.W.; Mason, A.D.; Pruitt, B.A. Weight Loss Following Thermal Injury. Ann. Surg. 1973, 178, 215–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanowski, K.S.; Fuanga, P.; Siddiqui, S.; Lenchik, L.; Palmieri, T.L.; Boutin, R.D. Computed Tomography Measurements of Sarcopenia Predict Length of Stay in Older Burn Patients. J. Burn Care Res. 2021, 42, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolle, C.; Cambiaso-Daniel, J.; Forbes, A.A.; Wurzer, P.; Hundeshagen, G.; Branski, L.K.; Huss, F.; Kamolz, L.-P. Recent Trends in Burn Epidemiology Worldwide: A Systematic Review. Burns 2017, 43, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, M.G.; Chinkes, D.L.; Finnerty, C.C.; Kulp, G.; Suman, O.E.; Norbury, W.B.; Branski, L.K.; Gauglitz, G.G.; Mlcak, R.P.; Herndon, D.N. Pathophysiologic Response to Severe Burn Injury. Ann. Surg. 2008, 248, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, J.F.; Herndon, D.N.; Barrow, R.E. Effect of Growth Hormone on Growth Delay in Burned Children: A 3-Year Follow-Up Study. Lancet 1999, 354, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, R.; Herndon, D.N.; Kobayashi, M.; Pollard, R.B.; Suzuki, F. CD4- CD8- TCR Alpha/Beta+ Suppressor T Cells Demonstrated in Mice 1 Day After Thermal Injury. J. Trauma 1997, 42, 635–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeschke, M.G.; Gauglitz, G.G.; Kulp, G.A.; Finnerty, C.C.; Williams, F.N.; Kraft, R.; Suman, O.E.; Mlcak, R.P.; Herndon, D.N. Long-Term Persistance of the Pathophysiologic Response to Severe Burn Injury. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e21245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, C.; Herndon, D.N.; Børsheim, E.; Bhattarai, N.; Chao, T.; Reidy, P.T.; Rasmussen, B.B.; Andersen, C.R.; Suman, O.E.; Sidossis, L.S. Long-Term Skeletal Muscle Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is Associated with Hypermetabolism in Severely Burned Children. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, W.J.; Morley, J.E.; Argilés, J.; Bales, C.; Baracos, V.; Guttridge, D.; Jatoi, A.; Kalantar-Zadeh, K.; Lochs, H.; Mantovani, G.; et al. Cachexia: A New Definition. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 27, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goisser, S.; Kemmler, W.; Porzel, S.; Volkert, D.; Sieber, C.C.; Bollheimer, L.C.; Freiberger, E. Sarcopenic Obesity and Complex Interventions with Nutrition and Exercise in Community-Dwelling Older Persons—A Narrative Review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2015, 10, 1267–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galicia, K.E.; Thompson, C.M.; Lewis, A.E.; Joyce, C.J.; Hill, D.M.; Schneider, J.C.; Nyygard, R.M.; Harrington, D.M.; Holmes, J.H.; Moffatt, L.T.; et al. American Burn Association (ABA) Burn Care Quality Platform (BCQP) and Large Data Set Analysis Considerations: A Practical Guide to Investigating Clinical Questions in Burns via Large Data Sets. J. Burn Care Res. 2024, 45, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iidaka, T.; Horii, C.; Tanegashima, G.; Muraki, S.; Oka, H.; Kawaguchi, H.; Nakamura, K.; Akune, T.; Tanaka, S.; Yoshimura, N. Ten-Year Incidence of Sarcopenia in a Population-Based Cohort: Results from the Research on Osteoarthritis/Osteoporosis Against Disability Study. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2024, 25, 105263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyongchaiwat, K.; Akekawatchai, C. Prevalence and Incidence of Sarcopenia and Low Physical Activity Among Community-Dwelling Older Thai People: A Preliminary Prospective Cohort Study 2-Year Follow-Up. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European Consensus on Definition and Diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Larsson, S.C. Epidemiology of Sarcopenia: Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Consequences. Metabolism 2023, 144, 155533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcon, L.J.; Harris-Love, M.O. Sarcopenia and the New ICD-10-CM Code: Screening, Staging, and Diagnosis Considerations. Fed. Pract. 2017, 34, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bessey, P.Q.; Arons, R.R.; Dimaggio, C.J.; Yurt, R.W. The Vulnerabilities of Age: Burns in Children and Older Adults. Surgery 2006, 140, 705–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lachs, D.K.; Stern, M.E.; Elman, A.; Gogia, K.; Clark, S.; Mulcare, M.R.; Greenway, A.; Golden, D.; Sharma, R.; Bessey, P.Q.; et al. Geriatric Burn Injuries Presenting to the Emergency Department of a Major Burn Center: Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. J. Emerg. Med. 2022, 63, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, S.W.; Runyan, C.W.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Linzer, M.A.; Sacks, J.J.; Butts, J.D. Fatal Residential Fires: Who Dies and Who Survives? JAMA 1998, 279, 1633–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, S.M.; Mitchell, K.; Heap, A. The Malnutrition Quality Improvement Initiative: A Multiyear Partnership Transforms Care. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019, 119, S18–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, B.E.; Castle, J.T.; Wilt, W.S.; Fedder, K.; Riser, J.; Burke, E.D.; Hourigan, J.S.; Bhakta, A.S. Improving Physician Documentation for Malnutrition: A Sustainable Quality Improvement Initiative. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0287124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, S.M.; Khan, M. Elevating Malnutrition Care Coordination for Successful Patient Transitions. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2018, 118, 1761–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheckter, C.C.; Rochlin, D.H.; Moshrefi, S.; Schenone, M.; Vargas, V.; Sproul, J.; Karanas, Y.L. Volume- vs. Rate-Based Tube Feeding in Burn Patients: A Case-Control Study. Burn. Open 2018, 2, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Huang, J.; Yu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, L.; Gu, Z.; Su, Q. Influence of Early Post-Burn Enteral Nutrition on Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Extensive Burns. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2011, 48, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, D.W.; Wolf, S.E.; Mlcak, R.; Chinkes, D.L.; Ramzy, P.I.; Obeng, M.K.; Ferrando, A.A.; Wolfe, R.R.; Herndon, D.N. Persistence of Muscle Catabolism after Severe Burn. Surgery 2000, 128, 312–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, B.; Marks, D.L.; Grossberg, A.J. Diverging metabolic programmes and behaviours during states of starvation, protein malnutrition, and cachexia. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 1429–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the European Burns Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).