Abstract

Burn injuries are traumatic experiences that can detrimentally impact an individual’s psychological and emotional wellbeing. Despite this, some survivors adapt to psychosocial challenges better than others despite similar characteristics relating to the burn. Positive adaptation is known as resilience or posttraumatic growth, depending on the trajectory and process. This review aimed to describe the constructs of resiliency and growth within the burn injury context, examine the risk factors that inhibit resilience or growth after burn (barriers), the factors that promote resilience or growth after burn (enablers), and finally to assess the impact of interventions that have been tested that may facilitate resilience or growth after burn. This review was performed according to the recently updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines. An electronic search was conducted in November 2021 on the databases PubMed, Medline (1966-present), Embase (1974-present), PsycINFO for English-language peer-reviewed academic articles. There were 33 studies included in the review. Findings were mixed for most studies; however, there were factors related to demographic information (age, gender), burn-specific characteristics (TBSA, time since burn), person-specific factors (personality, coping style), psychopathology (depression, PTSD), and psychosocial factors (social support, spirituality/religion, life purpose) that were evidenced to be related to resilience and growth. One qualitative study evaluated an intervention, and this study showed that a social camp for burn patients can promote resilience. This study has presented a variety of factors that inhibit or encourage resilience and growth, such as demographic, individual, and social factors. We also present suggestions on interventions that may be used to promote growth following this adverse event, such as improving social support, coping styles and deliberate positive introspection.

1. Introduction

Improved care and treatments for burn injury have increased survival rates, but have led burn survivors to contend with greater long-term psychosocial and physical consequences [1]. It is recognized that burn injuries are traumatic experiences that can detrimentally impact an individual’s psychological and emotional wellbeing. Posttraumatic stress disorder occurs in 8 to 30% of the adult burn population [2], and 11 to 13% of child burn populations [3], and routine clinical practice accepts the absence of a mental health disorder as an acceptable goal. However, research has shown that postburn hospital admission rates for mental health conditions were 3.52–6.79 times as high compared to a matched uninjured cohort, suggesting that the absence of a diagnosed mental health is not adequate for optimal mental health recovery [4]. Despite this, some survivors adapt to psychosocial challenges better than others despite similar type, severity, bodily location, and physical consequences of the burn.

Resilience and posttraumatic growth (PTG) are related constructs but are not synonymous. Historically, PTG was seen to be part of resilience and they are often confused in the general post-trauma literature [5]. Resilience has been defined as the ability to maintain relatively stable, healthy levels of psychological and physical functioning, [6] and is about adapting or ‘bouncing back’ to the pre-trauma state. PTG has been defined as ‘the subjective experience of positive psychological change reported by an individual as a result of the struggle with trauma’ and describes development that has occurred beyond pre-trauma psychological functioning [7,8]. Resilience is static because it involves little or no change to an individual’s worldview, the event is already understandable, which allows a focus on the future. PTG, on the other hand, is dynamic because it involves a changing worldview, and it arises from deliberate rumination that focuses on the event with the purpose of making some sense of what happened [9,10].

Within the field of medical trauma, studies have investigated the barriers and enablers of resilience and PTG in cancer [11], serious paediatric illness [12], and spinal cord injury [13]. Across the different medical issues, resilience and PTG are associated with individuals being able to talk about their experiences, younger age, perceptions about the medical issue, and social support [11,12,13]. Specifically in burn injuries, there have been studies on the factors associated with resilience and PTG, and one review has investigated the correlates of PTG in adult burn survivors [9]. This review highlighted key areas that enabled PTG in this population (including function, quality of life, social support and optimism, hope, and new opportunities), which could be targeted following a burn injury to facilitate PTG. Though this review showcased important factors involved in PTG in burn patients, resilience, which is a separate though related construct, was not investigated. Further, there have been no attempts to synthesise the literature though, across ages and within paediatric populations. It is important to ascertain whether there are different factors that contribute to PTG in childhood and adolescence.

This review aimed to assess the published literature that has been conducted in the field of resilience and PTG after burn injury. Specifically, the aim was to describe the constructs of resiliency and growth within the burn injury context, examine the risk factors that inhibit resilience or growth after burn (barriers), the factors that promote resilience or PTG after burn (enablers), and finally to assess the impact of interventions that have been tested that may facilitate resilience or growth after burn.

2. Method

This review was performed according to the recently updated Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Guidelines [14,15]. The review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID295835).

2.1. Research Questions

- What research has been conducted in the field of resilience and PTG after burn injury that examines the risk factors that inhibit resilience or growth after burn (barriers), the factors that promote resilience, or PTG after burn (enablers)?

- What interventions have been tested that may facilitate resilience or PTG after burn?

2.2. Search Strategy

An electronic search was conducted in November 2021 on the databases PubMed, Medline (1966–present), Embase (1974–present), and PsycINFO for English-language peer-reviewed academic articles. No time restrictions were placed. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) or equivalent terms were used for searching in Title, Abstract, and Keywords according to the requirements of the database. The search terms were broad to capture all relevant articles. MeSH or Indexed terms related to burn injury were combined using the Boolean operator “OR”. Separately, MeSH or Indexed terms related to burn survivorship, resilience, and posttraumatic growth were also combined using the Boolean operator “OR”. These two searches were combined with the Boolean operator “AND”.

Indexed terms: ((burn.mp. or Burns/) AND ((posttraumatic growth.mp. or exp Posttraumatic Growth, Psychological/) OR (Adaptation, Psychological/ or Resilience, Psychological/ or resilience.mp.))).

MeSH terms: (Burns) AND (Survivors/psychology) OR (Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders/psychology OR Trauma and Stressor Related Disorders/rehabilitation) AND (Resilience, Psychological OR Posttraumatic Growth, Psychological).

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For question one (the investigation of barriers and enablers on resilience or PTG), qualitative or quantitative articles were included if they described factors that negatively or positively influenced resilience or growth. Participants could be adult or pediatric. Reviews were handled by extracting the relevant reference articles for inclusion in this review.

For question two, inclusion criteria were (1) adults and children with burn injury, (2) a psychosocial or physical intervention aimed at improving resilience or posttraumatic growth (this could be a psychotherapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), counselling, a psychoeducational strategy, peer support, or a physical or social activity, (3) any comparators, (4) outcomes involving resilience or posttraumatic growth, (5) all RCTs, and quasi-experimental intervention research studies. No time limits were set. Case reports, letters to the editor, conference abstracts, and grey literature were excluded. Articles published in languages other than English were excluded.

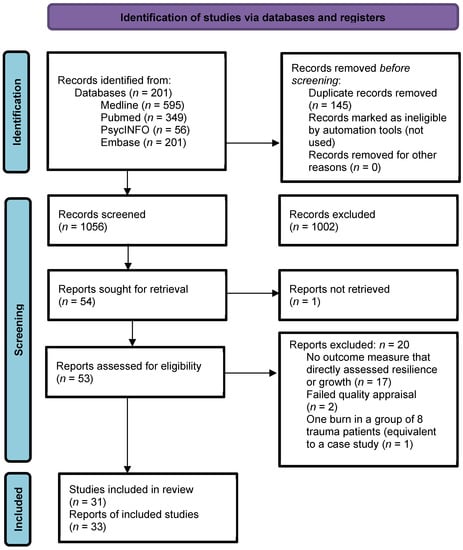

Titles and abstracts identified through the electronic search were reviewed independently by two authors (AW and LM) for inclusion. Each full-text review was completed by two authors to decide on eligibility for inclusion in the review. Any discrepancies in opinion were discussed between the authors. See the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1 for details.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

2.4. Critical Appraisal

Quality assessment and risk of bias was assessed with the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools [16]. The appropriate tool was selected depending on study design (see Table 1). Each study was assessed using these tools, the results were reviewed by the authors, and any discrepancies discussed. Two studies were excluded after quality assessment.

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The following information was extracted from the articles: authors, year and country, aim, study design, sample size, participant characteristics, clinical characteristics, outcome measures, statistical analyses, and findings.

Table 1.

Quality Appraisal of Studies.

Table 1.

Quality Appraisal of Studies.

| Study Type | JBI Quality Appraisal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Studies | Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to exposed unexposed groups? | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Were confounding factors identified? | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Were the participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or moment of exposure)? | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Was the follow up time reported and sufficiently long for outcomes to occur? | Was follow up complete, were the reasons to loss to follow up described/ explored? | Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? |

| Martin 2021 [17] | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Martin 2017b [18] | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Analytical Cross-sectional Studies | Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Were study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Were objective, standard criteria used to measure the condition? | Were confounding factors identified? | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | |||

| Ajoudani 2019 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Baillie 2014 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Bibi 2018 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Chen 2020 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| He 2013 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Holaday 1994 [24] | Y | Y | N | N | N | NA | Y | N | EXCLUDE | ||

| Hwang 2020 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Jang 2017 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Jibeen 2018 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Masood 2016 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | U | |||

| Quezada 2015 [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Rosenbach 2008 [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Royse 2017 [31] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Waqas 2016 [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Xia 2014 [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Yang 2014 [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Qualitative Research | Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? | Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | Is the research ethical according to current criteria, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |

| Abrams 2018 [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Badger 2010 [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Garbett 2017 [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Habib 2021 [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| Han 2020 [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Hunter 2013 [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Kool 2017 [41] | U | U | U | U | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | EXCLUDE |

| Kornhaber 2014 [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| Lau 2011 [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Martin 2016 [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Martin 2017 [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| McGarry 2014 [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| McLean 2015 [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | |

| Moi 2008 [48] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Neil 2021 [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | |

| Williams 2003 [50] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | |

| Zhai 2010 [51] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

Y = Yes; N = No; U = Unclear; NA = Not Applicable.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

This review included 33 studies. Study characteristics are outlined in Table 2 and Table 3. The studies comprised of two cohort studies, 15 analytical cross-sectional studies, 15 qualitative studies, and one qualitative intervention study. The settings of the studies included Australia (n = 8), China (n = 5), United States (n = 4), Pakistan (n = 3), Germany (n = 2), Korea (n = 2), United Kingdom (n = 2), Canada (n = 1), Iran (n = 1), Mexico (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Saudi Arabia (n = 1), South Africa (n = 1), and Taiwan (n = 1). Thirty studies investigated adult populations, while only three investigated children or young people. In total, there were 1972 participants in the quantitative studies, and 205 participants in the qualitative studies. Of the quantitative studies, nine investigated resilience and eight investigated PTG. Four evaluated resilience with the Connor Davidson Resilience Scale, two used the Resilience Scale developed by Wagnild and Young [52], one used the Ego Resilience Scale developed by Block and Kremen [53], one used the State-Trait Resiliency Scale [54] and one used resilience scales developed for Mexican populations. Seven studies evaluated PTG with the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory [55,56], and one used the Perceived Benefit Scale [57]. For resilience, as measured by the CD-RISC, mean scores varied from 49.89 to 67.34 (Table 2). For PTG, as measured by the PTGI, mean scores (out of 5) varied from 1.26 to 3.18 [30], with mean scores over 2.5 recommended to represent a useful level of PTG [44]. Forty different outcome measures were used in the analyses, and this prevented the ability to quantitatively synthesize the data (Table 2). The qualitative studies were mixed, those that evaluated resilience stated this outcome, and those that evaluated growth reported the positive changes described by burn survivors.

Table 2.

Quantitative Study Characteristics.

Table 3.

Qualitative Study Characteristics.

3.2. Question One: Barriers and Enablers to Resilience or PTG

The results of the quantitative studies suggested that there are several barriers and enablers to resilience or PTG following a burn (see Table 2). Total body surface area of the burn was reported to be positively associated with PTG in four studies [18,19,20,31], although another study reported no association [30]. The relationship with stress differed between resilience and PTG, and was reported to differ between males and females. In terms of resilience, three studies reported that increased stress [22,28] or subclinical symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder [21] hindered resilience following a burn. Bibi et al., [21] reported that this barrier to resilience was further associated with gender, as females reported higher traumatic stress and lower resilience. Masood et al. also reported similar findings about gender, resilience, and distress [28]. However, Yang et al. [34] reported resilience to be higher in females. For PTG, stress and PTG co-exist, stress is reported to precede growth, and has a positive association with growth [18,20,30], with females reporting more growth than males [30]. In terms of barriers to PTG, time postburn was identified as a factor, with higher risk for poor PTG occurring in the year following a burn [32]. Younger age was associated with resilience [29], but not PTG [30], and other studies found no association between age and either construct [23].

Good social support was a strong enabler of both resilience and PTG [18,20,25,30]. Spirituality had a positive effect on both resilience and PTG [17,22,23], Additionally, some studies found personality factors like optimism promoted resilience [32], extraversion promoted PTG, and neuroticism was a barrier to PTG [27]. Other social factors were influential, such as marital status (divorced people being more resilient) and occupation (farmers and workers being more resilient) [23]. PTG was found to be influenced by returning to work [18], narrative restructuring to reframe the accident [20], and coping mechanisms [20,28].

In terms of the qualitative studies, both barriers and enablers to resilience were identified (see Table 3). Barriers included seeing others in distress [58], needing to be prepared to ask for help [58], maladaptive or negative coping styles [45], and worries about stigma or rejection [45]. Another common barrier found by several studies was self-consciousness or worries about the reactions and perceptions of others [17,36,45]. Barriers to PTG were assessed by Martin et al. [45], and factors included emotional barriers (e.g., fear of rejection, self-consciousness, embarrassment), situations barriers (e.g., questions from others), and behavioral barriers (reactions from others, pressure garments), as well as avoidant coping styles. Enablers of resilience included skills-based factors such as utilizing problem-solving skills [35], improving social competence [35,37], having a sense of autonomy [35], resourcefulness [35], critical thinking [35], and detaching from negativity [35]. Other themes included factors related to personality such as having empathy [35,37], having strong willpower [35,39], having a sense of optimism or hope [17,35,39], using humor [35,40], and being curious about the world [39]. Positive coping was also indicative of enhanced resilience [35,37,39,40,42,47,51], and shifting self-perception [37,49] and sharing or expressing one’s feelings [37]. Having a sense of altruism and spirituality were also identified as enabling resilience [17,35,39,40,44,46,51], as was not being ashamed or embarrassed about the scar [40]. The two most common factors enabling resilience were having a positive life purpose or meaning [35,37,39,40,42,44,47,51], and having good social or peer support [17,37,39,40,44,49,51].

Four qualitative studies looked at barriers and enablers of PTG [37,40,44,51]. Again, across all studies, positive relationships were important in fostering PTG [37,40,44,51]. Further, shifting self-perception and life outlook [37,51], acknowledging one’s personal strength [44,51], new possibilities [44], spirituality [24], gratitude [40,44], humor [40], managing emotions [51], effective coping [40,51], altruism [51], and more sharing with others [51].

3.3. Question Two: Interventions Targeting Resilience or PTG after Burns

There was only one qualitative study that investigated the impact of a burn camp for children on psychosocial outcomes and found that the social environment of a burn camp greatly enhanced resilience [49]. In particular, the camp improved the children’s confidence, psychological recovery, it normalized their experiences, and provided social support.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to describe the constructs of resilience and growth within the burn injury context, examine the risk factors that inhibit resilience or growth after burn (barriers), the factors that promote resilience or PTG after burn (enablers), and to assess the impact of interventions that have been tested that may facilitate resilience or growth after burn. Findings were mixed for most studies; however, there were factors related to demographic information, burn-specific characteristics, person-specific factors, psychopathology, and psychosocial and social factors that were evidenced to be related to resilience and PTG. It is important to remember the differences in the construct of resilience and growth.

For age, one study found that being younger promoted resilience [29], another that showed older participants demonstrated more PTG [30], and another that contradicted this finding of no significant association between age and PTG [23]. In other populations, PTG is typically associated with younger age [59,60], and thus these results should be interpreted with caution given the variability in findings. For gender, associations with resilience were reported to be higher in women in one study [28], yet lower in others [21], [28]. In these latter two studies, lower levels of resilience presented with higher levels of stress symptoms. In addition, the gender differences were thought to be mediated by higher levels of social support for males in the local cultural environment, but this was not statistically investigated. However, associations between gender and PTG differed to the associations between gender and resilience, with women reporting higher levels of PTG compared to men [30], although another study found no gender differences [23].

Most studies showed larger TBSA being associated with higher levels of PTG [18,19,20,23,31]; however, another study found no relationship between TBSA and PTG [30], but this was possibly due to study design. The positive association between TBSA and PTG might be due to the influence of high levels of stress leading to more growth [20], which is consistent with theories of PTG [8,61]. In addition, scar visibility might affect resilience or PTG [9,40,43], although functionality might be more important to recovery than aesthetics [40]. As time moves on after the burn event, burn survivors may do better [57], and those burnt as children might do better in terms of social support compared to adults [43]. Not all studies reported time since burn, and further research is required to assess long-term trajectories.

Individual factors related to resilience or PTG included personality and potential psychopathology. Optimism is a personality factor that might contribute to resilience [21,23] and has been suggested to boost PTG by affecting subjective wellbeing [23]. Optimism has been found to promote PTG in other clinical populations such as patients with HIV [62]. The personality trait of extraversion was found to predict positive change, whilst neuroticism was found to increase distress and impede PTG [27].

The role of spirituality is interesting, those who have a faith find more inner strength, and both spiritual change and inner strength are components of PTG [55]. Spirituality has been shown to have a positive association with resilience [31] and growth [19,27] and the importance of offering pastoral support to patients should not be underestimated [17].

Adaptive coping mechanisms (such as positive reframing, humor, planning, resourcefulness, downward comparison, acceptance, and focusing on the future in a positive way) were all found to promote resilience and PTG [18,26,35,39,40,43,44,48,58]. Distress was found to be related to resilience and PTG, and it is thought that this is because those in distress might need to adopt new ways of thinking about a situation that is not able to be changed. Stress is thought to precede PTG [18,20] and stress and PTG co-exist [30]. This theory is supported in research with other populations, whereby more stress or distress is associated with more PTG [12,63]. Depression and anxiety were found to impede resilience and PTG in some studies [26,36,40], but not others [18]. Studies in other populations (i.e., cancer) have found that PTG is related to fewer symptoms of depression [64]. Burn-related studies that found depression to be a barrier to growth, suggest that this is due to the overwhelming of coping resources that are necessary for growth to occur [58] or due to the negative reframing that naturally occurs in depression [18].

Social support was overwhelmingly identified in this review to facilitate both resilience and PTG. Specifically, we found that social support [17,18,20,22,31,34,37,39,40,44,49,51,65], spirituality/religion [17,31,35,39,40,44,46,51], and a positive life purpose [35,37,39,40,44] were the most commonly reported enablers of resilience and PTG. Further, having quality relationships [26] and recognizing you are not alone [17,31] were notably important. It should be stated though, that cultural differences may impact on the relationship between spirituality and religion [51]. Concerns about burdening others by sharing experiences were a social barrier that was a barrier to PTG [40,44]. The results found in this study are in line with research on PTG in non-burn populations, such as rheumatoid arthritis [59]. The process by which growth occurs can only be explored with rich contextual data from qualitative studies, and these suggest that growth arises from deep introspection [39] that leads to a new worldview to create coherence in their own personal narratives of their lives [48] and the need to find some meaning in the situation [51]. This is similar to PTG after other types of trauma, and is central to related background theories [55,65].

One qualitative study conducted an intervention to promote resilience and found that encouraging social support via a burn camp could help improve resilience in children [49]. One other study audited peer support as a potential mechanism for intervention to promote resilience and PTG and noted it would be a promising area to target [58], which is logical given the overwhelming evidence in this study supporting social factors in the encouragement of resilience and PTG [17,18,20,22,31,34,37,39,40,44,49,51,65]. Future studies should target adult populations, as there were no interventions for this group despite poor psychosocial outcomes being an issue for this population [4]. Interventions could focus on methods to promote deliberate rumination and introspection [39], teach adaptive coping styles [58], and teach clinicians and parents how to recognize ‘red flags’ and promote ‘green flags’ (i.e., symptoms of PTSD and PTG) [58]. Finally, as it appears that depression is a factor in resilience and PTG, clinicians should screen burn patients for symptoms of depression, to optimize psychosocial recovery and ensure a good personal environment for PTG to occur.

Interventions, Limitations, and Future Considerations

This study found several limitations in the existing literature on resilience and PTG in populations that have experienced a burn, which could drive future research and clinical practice. Firstly, the studies were heterogeneous in their scope and methodology, which made synthesis difficult and rendering us unable to conduct a meta-analysis. There needs to be more research in the underlying mechanisms of both resilience and PTG. Further to this, there were only two small longitudinal studies on the progression on PTG [18,58], which makes understanding PTG as a process difficult. There also needs to be more research conducted on child and adolescent populations, given this is a large demographic for burn injuries. We do not currently know how the presentation or trajectory of PTG differs in pediatric versus adult populations.

5. Conclusions

Resilience and PTG are important constructs to understand given that individuals who experience a burn injury are a high-risk population for longer term mental health issues. This study has presented a variety of factors that inhibit or encourage resilience and PTG, such as demographic, individual, and social factors. We also present suggestions on interventions that may be used to promote growth following this adverse event, such as improving social support, coping styles, and deliberate positive introspection. Ideally, clinicians and family members/parents would also be aware of the importance of resilience and PTG and be able to look out for and promote these phenomena when treating burns patients.

Author Contributions

L.M. conducted the search; A.W. and L.M. completed the title and abstract review and the quality appraisal; All authors (A.W., I.B., A.A., T.L., H.M., F.W. and L.M.) completed the full text reviews; I.B., A.A., T.L. constructed Table 2 and Table 3; All authors (A.W., I.B., A.A., T.L., H.M., F.W. and L.M.) assisted with the manuscript, with A.W. and L.M. being the main authors; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

There was no specific grant funding for this paper, but in-kind support was received from Fiona Woof Foundation, and Telethon Kids Institute.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request to corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Fiona Wood Foundation and the Telethon Kids Institute for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Pallua, N.; Künsebeck, H.; Noah, E. Psychosocial adjustments 5 years after burn injury. Burns 2003, 29, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, K. Which factors influence the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with burn injuries? A review of the literature. Burns 2015, 41, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolard, A.; Hill, N.; McQueen, M.; Martin, L.; Milroy, H.; Wood, F.; Bullman, I.; Lin, A. The psychological impact of paediatric burn injuries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.; Randall, S.; Boyd, J.; Wood, F.; Fear, M.; Rea, S. A population-based retrospective cohort study to assess the mental health of patients after a non-intentional burn compared with uninjured people. Burns 2018, 44, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.; Litz, B.; Charney, D.; Friedman, M. (Eds.) Preface. In Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano, G. Loss, trauma and human resilience: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, T.; Maercker, A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology: A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 626–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.; Calhoun, L. Trauma and Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Posttraumatic growth after burn in adults: An integrative literature review. Burns 2017, 43, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, W.; Kuban, C. Trauma-informed resilience and posttraumatic growth (PTG). Reclaiming Child. Youth 2011, 20, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, M.; Giese-Davis, J.; Golant, M.; Kronenwetter, C.; Chang, V.; Spiegel, D. Breast cancer as trauma: Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2007, 14, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoraro, J.; Womer, J.; Kazak, A.; Feudtner, C. Posttraumatic growth in parents and pediatric patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Lee, Y. The experience of posttraumatic growth for people with spinal cord injury. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Br. Med. J. Open Access 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. 2017. Available online: http://joannabriggs.org.ebp/critical_appraisal_tools (accessed on 21 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. A quantitative analysis of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, depression and coping styles after burn. Burns 2021, 47, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; Bulsara, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Quality of life and posttraumatic growth after adult burn: A prospective, longitudinal study. Burns 2017, 43, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoudani, F.; Jafarizadeh, H.; Kazamzadeh, J. Social support and posttraumatic growth in Iranian burn survivors: The mediating role of spirituality. Burns 2019, 45, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, S.; Sellwood, W.; Wisely, J. Post-traumatic growth in adults following a burn. Burns 2014, 40, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Kalim, S.; Khalid, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder and resilience among adult burn patients in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Burn. Trauma 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Lu, M.-H.; Weng, L.-T.; Lin, C.; Huang, P.-W.; Wang, C.-H.; Pan, H.-H. A correlational study of acute stress and resilience among hospitalized burn victims following the Taiwan ormosa Fun Coast explosion. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2018, 29, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Cao, R.; Feng, Z.; Guan, H.; Peng, J. The impacts of dispositional optimism and psychological resilience on the subjective well-being of burn patients: A structural equation modelling analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holaday, M.; Terrell, D. Resiliency Characteristics and Rorschach Variables in Children and Adolescents With Severe Burns. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1994, 15, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Lim, E. Factors associated with posttraumatic growth in patients with severe burns by treatment phase. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Park, J.; Chong, M.; Sok, S. Factors influencing resilience of burn patients in South Korea. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jibeen, T.; Mahfooz, M.; Fatima, S. Spiritual transcendence and psychological adjustment: The moderating role of personality in burn patients. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 1618–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Yusra, M.; Shama, M. Gender differences in resilience and psychological distress of patients with burns. Burns 2016, 42, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, L.; González, M.; Mecott, G. Explanatory model of resilience in pediatric burn survivors. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbach, C.; Renneberg, B. Positive change after severe burn injuries. J. Burn Care Res. 2008, 29, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royse, D.; Badger, K. Near-death experiences, posttraumatic growth, and life satisfaction among burn survivors. Soc. Work Health Care 2017, 56, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Naveed, S.; Bhuiyan, M.; Usman, J.; Inam-ul-Haq, A.; Cheema, S. Social support and resilience among patients with burn injury in Lahore, Pakistan. Cureus 2016, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.Y.; Kong, Y.; Yin, T.T.; Shi, S.H.; Huang, R.; Cheng, Y.H. The impact of acceptance of disability and psychological resilience on post-traumatic stress disorders in burn patients. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 1, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, H. Factors influencing resilience in patients with burns during rehabilitation period. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 1, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abrams, T.; Ratnapradipa, D.; Tillewein, H.; Lloyd, A. Resiliency in burn recovery: A qualitative analysis. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger, K.; Royse, D. Adult burn survivors’ views of peer support: A qualitative study. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbett, K.; Harcourt, D.; Buchanan, H. Using online blogs to explore positive outcomes after burn injuries. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, Z.; Saddul, R.; Kamran, F. Perceptions and experiences of female burn survivors with facial disfigurement. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhou, X.-P.; Liu, J.-E.; Yue, P.; Gao, L. The process of developing resilience in patients with burn injuries. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T.; Medved, M.; Hiebert-Murphy, D.; Brockmeier, J.; Sareen, J.; Thakrar, S.; Logsetty, S. “Put on your face to face the world”: Women’s narratives of burn injury. Burns 2013, 39, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, M.B.; Geenen, R.; Egberts, M.R.; Wanders, H.; Van Loey, N.E. Patients’ perspectives on quality of life after burn. Burns 2017, 43, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhaber, R.; Wilson, A.; Abu-Qamar, M.; McLean, L. Coming to terms with it all: Adult burn survivors’ ‘lived experience’ of acknowledgement and acceptance during rehabilitation. Burns 2014, 40, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, U.; van Niekerk, A. Restorying the self: An exploration of young burn survivors’ narratives of resilience. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Evaluation of the posttraumatic growth inventory after severe burn injury in Western Australia: Clinical implications for use. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2398–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Social challenges of visible scarring after severe burn: A qualitative analysis. Burns 2017, 43, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, S.; Elliott, C.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F.; Girdler, S. Paediatric burns: From the voice of the child. Burns 2014, 40, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L.; Rogers, V.; Kornhaber, R.; Proctor, M.-T.; Kwiet, J.; Streimer, J.; Vandervord, J. The patient–body relationship and the “lived experience” of a facial burn injury: A phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2015, 8, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moi, A.; Gjengedal, E. Life after burn injury: Striving for regained freedom. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, J.; Goch, I.; Sullivan, A.; Simons, M. The role of burn camp in the recovery of young people from burn injury: A qualitative study using long-term follow-up interviews with parents and participants. Burns 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.R.; Davey, M.; Klock-Powell, K. Rising from the Ashes. Soc. Work Health Care 2003, 36, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H. What does posttraumatic growth mean to Chinese burn patients: A phenomenological study. J. Burn Care Res. 2010, 31, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.; Young, H. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.; Kremen, A. IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiew, C.; Mori, T.; Shimizu, M.; Tominaga, M. Measurement of resilience development: Preliminary results with a state-trait resilience inventory. J. Learn. Curric. Dev. 1.

- Tedeschi, R.; Calhoun, L. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Meauring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.; Tedeschi, R.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsky, T.; Triplett, K.; Danhauer, S. A short for of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J.; Fisher, R. The Perceived Benefit Scales: Measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Soc. Work. Res. 1998, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, K.; Royse, D. Helping others heal: Burn survivors and peer support. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirik, G.; Karanci, A. Variable related to posttraumatic growth in Turkish rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2008, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, S.; Ostroff, J.; Winkel, G.; Goldstein, L.; Fox, K.; Grana, G. Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: Patient, partner, and couple perspectives. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Posttraumatic growth: Three explanatory models. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Milam, J. Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2353–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, D. The relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic growth: Gender differences in PTG and PTSD subgroups. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi-Kashani, F.; Vaziri, S.; Akbari, M.; Kazemi-Zanjani, N.; Shamkoeyan, L. Predicting post traumatic growth based upon self-efficacy and perceived social support in cancer patients. Iran. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 7, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knudson-Cooper, M. Adjustment to visible stigma: The case of the severely burned. Soc. Sci. Med. Part B Med. Anthropol. 1981, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).