Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth after Burn: A Review of Barriers, Enablers, and Interventions to Improve Psychological Recovery

Abstract

1. Introduction

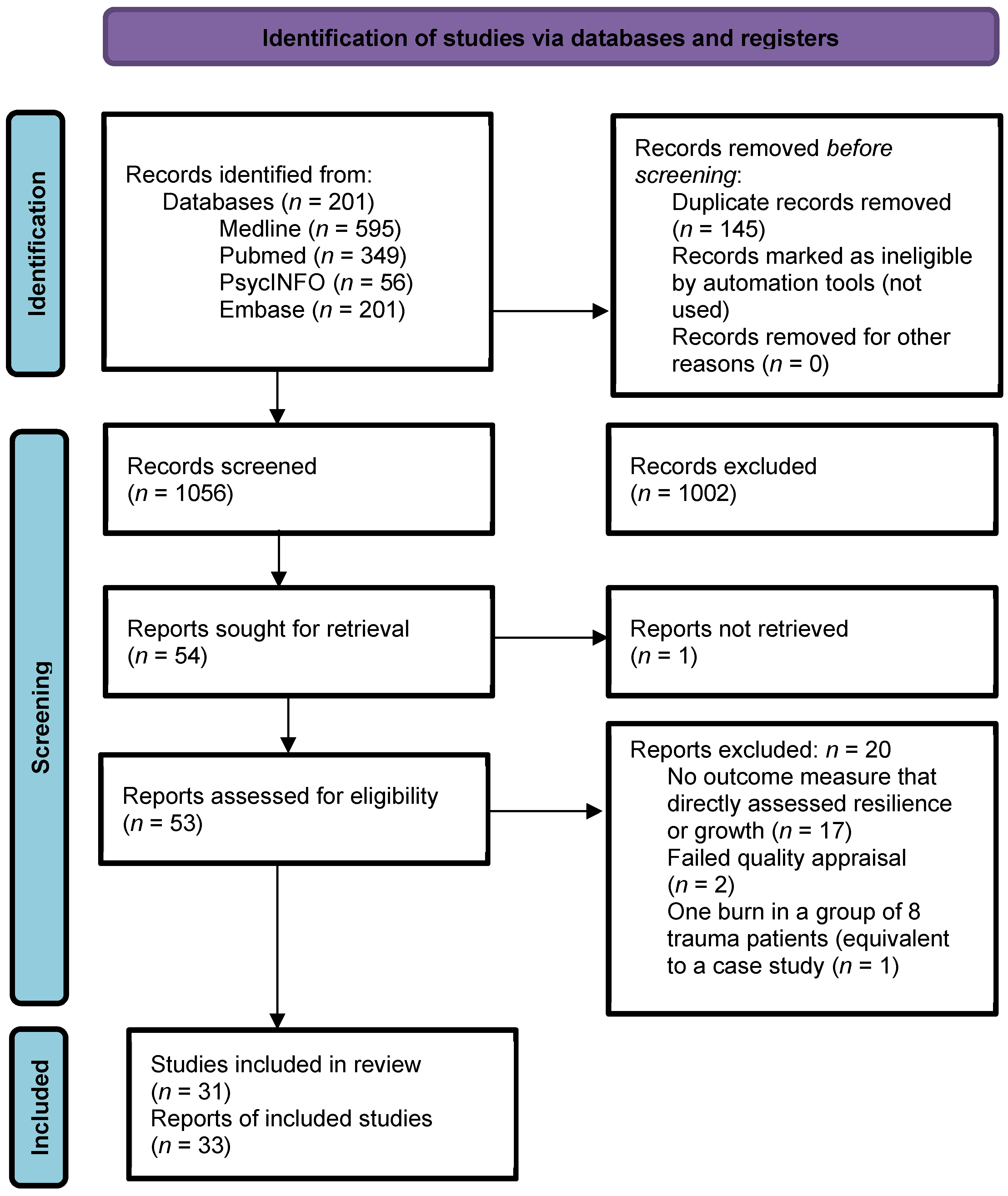

2. Method

2.1. Research Questions

- What research has been conducted in the field of resilience and PTG after burn injury that examines the risk factors that inhibit resilience or growth after burn (barriers), the factors that promote resilience, or PTG after burn (enablers)?

- What interventions have been tested that may facilitate resilience or PTG after burn?

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Critical Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction and Synthesis

| Study Type | JBI Quality Appraisal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort Studies | Were the two groups similar and recruited from the same population? | Were the exposures measured similarly to assign people to exposed unexposed groups? | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Were confounding factors identified? | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Were the participants free of the outcome at the start of the study (or moment of exposure)? | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Was the follow up time reported and sufficiently long for outcomes to occur? | Was follow up complete, were the reasons to loss to follow up described/ explored? | Were strategies to address incomplete follow up utilized? | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? |

| Martin 2021 [17] | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Martin 2017b [18] | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | NA | Y |

| Analytical Cross-sectional Studies | Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined? | Were study subjects and the setting described in detail? | Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way? | Were objective, standard criteria used to measure the condition? | Were confounding factors identified? | Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated? | Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way? | Was appropriate statistical analysis used? | |||

| Ajoudani 2019 [19] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Baillie 2014 [20] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Bibi 2018 [21] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Chen 2020 [22] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| He 2013 [23] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Holaday 1994 [24] | Y | Y | N | N | N | NA | Y | N | EXCLUDE | ||

| Hwang 2020 [25] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Jang 2017 [26] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Jibeen 2018 [27] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Masood 2016 [28] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | U | |||

| Quezada 2015 [29] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Rosenbach 2008 [30] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Royse 2017 [31] | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Waqas 2016 [32] | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | NA | Y | Y | |||

| Xia 2014 [33] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Yang 2014 [34] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | |||

| Qualitative Research | Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? | Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? | Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? | Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, addressed? | Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? | Is the research ethical according to current criteria, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? | Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data? | |

| Abrams 2018 [35] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Badger 2010 [36] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Garbett 2017 [37] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Habib 2021 [38] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| Han 2020 [39] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Hunter 2013 [40] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Kool 2017 [41] | U | U | U | U | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | EXCLUDE |

| Kornhaber 2014 [42] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| Lau 2011 [43] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Martin 2016 [44] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Martin 2017 [45] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| McGarry 2014 [46] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | |

| McLean 2015 [47] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | U | |

| Moi 2008 [48] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Neil 2021 [49] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | U | Y | Y | |

| Williams 2003 [50] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | |

| Zhai 2010 [51] | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

3.2. Question One: Barriers and Enablers to Resilience or PTG

3.3. Question Two: Interventions Targeting Resilience or PTG after Burns

4. Discussion

Interventions, Limitations, and Future Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pallua, N.; Künsebeck, H.; Noah, E. Psychosocial adjustments 5 years after burn injury. Burns 2003, 29, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, K. Which factors influence the development of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with burn injuries? A review of the literature. Burns 2015, 41, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolard, A.; Hill, N.; McQueen, M.; Martin, L.; Milroy, H.; Wood, F.; Bullman, I.; Lin, A. The psychological impact of paediatric burn injuries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.; Randall, S.; Boyd, J.; Wood, F.; Fear, M.; Rea, S. A population-based retrospective cohort study to assess the mental health of patients after a non-intentional burn compared with uninjured people. Burns 2018, 44, 1417–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southwick, S.; Litz, B.; Charney, D.; Friedman, M. (Eds.) Preface. In Resilience and Mental Health: Challenges Across the Lifespan; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnano, G. Loss, trauma and human resilience: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. Am. Psychol. 2004, 59, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, T.; Maercker, A. Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology: A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 26, 626–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R.; Calhoun, L. Trauma and Transformation: Growing in the Aftermath of Suffering; Sage Publications Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Posttraumatic growth after burn in adults: An integrative literature review. Burns 2017, 43, 459–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, W.; Kuban, C. Trauma-informed resilience and posttraumatic growth (PTG). Reclaiming Child. Youth 2011, 20, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Cordova, M.; Giese-Davis, J.; Golant, M.; Kronenwetter, C.; Chang, V.; Spiegel, D. Breast cancer as trauma: Posttraumatic stress and posttraumatic growth. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2007, 14, 308–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picoraro, J.; Womer, J.; Kazak, A.; Feudtner, C. Posttraumatic growth in parents and pediatric patients. J. Palliat. Med. 2014, 17, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.; Lee, Y. The experience of posttraumatic growth for people with spinal cord injury. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 877–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Br. Med. J. Open Access 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joanna Briggs Institute. Critical Appraisal Tools. 2017. Available online: http://joannabriggs.org.ebp/critical_appraisal_tools (accessed on 21 December 2021). [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. A quantitative analysis of the relationship between posttraumatic growth, depression and coping styles after burn. Burns 2021, 47, 1748–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; Bulsara, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Quality of life and posttraumatic growth after adult burn: A prospective, longitudinal study. Burns 2017, 43, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajoudani, F.; Jafarizadeh, H.; Kazamzadeh, J. Social support and posttraumatic growth in Iranian burn survivors: The mediating role of spirituality. Burns 2019, 45, 732–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillie, S.; Sellwood, W.; Wisely, J. Post-traumatic growth in adults following a burn. Burns 2014, 40, 1089–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibi, A.; Kalim, S.; Khalid, M. Post-traumatic stress disorder and resilience among adult burn patients in Pakistan: A cross-sectional study. Burn. Trauma 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-L.; Lu, M.-H.; Weng, L.-T.; Lin, C.; Huang, P.-W.; Wang, C.-H.; Pan, H.-H. A correlational study of acute stress and resilience among hospitalized burn victims following the Taiwan ormosa Fun Coast explosion. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2018, 29, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Cao, R.; Feng, Z.; Guan, H.; Peng, J. The impacts of dispositional optimism and psychological resilience on the subjective well-being of burn patients: A structural equation modelling analysis. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holaday, M.; Terrell, D. Resiliency Characteristics and Rorschach Variables in Children and Adolescents With Severe Burns. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 1994, 15, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Lim, E. Factors associated with posttraumatic growth in patients with severe burns by treatment phase. Nurs. Open 2020, 7, 1920–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jang, M.; Park, J.; Chong, M.; Sok, S. Factors influencing resilience of burn patients in South Korea. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2017, 49, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jibeen, T.; Mahfooz, M.; Fatima, S. Spiritual transcendence and psychological adjustment: The moderating role of personality in burn patients. J. Relig. Health 2018, 57, 1618–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, A.; Yusra, M.; Shama, M. Gender differences in resilience and psychological distress of patients with burns. Burns 2016, 42, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quezada, L.; González, M.; Mecott, G. Explanatory model of resilience in pediatric burn survivors. J. Burn Care Res. 2016, 37, 216–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbach, C.; Renneberg, B. Positive change after severe burn injuries. J. Burn Care Res. 2008, 29, 638–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royse, D.; Badger, K. Near-death experiences, posttraumatic growth, and life satisfaction among burn survivors. Soc. Work Health Care 2017, 56, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas, A.; Naveed, S.; Bhuiyan, M.; Usman, J.; Inam-ul-Haq, A.; Cheema, S. Social support and resilience among patients with burn injury in Lahore, Pakistan. Cureus 2016, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.Y.; Kong, Y.; Yin, T.T.; Shi, S.H.; Huang, R.; Cheng, Y.H. The impact of acceptance of disability and psychological resilience on post-traumatic stress disorders in burn patients. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 1, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, Y.; Ma, H. Factors influencing resilience in patients with burns during rehabilitation period. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2014, 1, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Abrams, T.; Ratnapradipa, D.; Tillewein, H.; Lloyd, A. Resiliency in burn recovery: A qualitative analysis. Soc. Work Health Care 2018, 57, 774–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badger, K.; Royse, D. Adult burn survivors’ views of peer support: A qualitative study. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garbett, K.; Harcourt, D.; Buchanan, H. Using online blogs to explore positive outcomes after burn injuries. J. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, Z.; Saddul, R.; Kamran, F. Perceptions and experiences of female burn survivors with facial disfigurement. Chin. J. Traumatol. 2021, 24, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Zhou, X.-P.; Liu, J.-E.; Yue, P.; Gao, L. The process of developing resilience in patients with burn injuries. J. Nurs. Res. 2020, 28, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, T.; Medved, M.; Hiebert-Murphy, D.; Brockmeier, J.; Sareen, J.; Thakrar, S.; Logsetty, S. “Put on your face to face the world”: Women’s narratives of burn injury. Burns 2013, 39, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kool, M.B.; Geenen, R.; Egberts, M.R.; Wanders, H.; Van Loey, N.E. Patients’ perspectives on quality of life after burn. Burns 2017, 43, 747–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornhaber, R.; Wilson, A.; Abu-Qamar, M.; McLean, L. Coming to terms with it all: Adult burn survivors’ ‘lived experience’ of acknowledgement and acceptance during rehabilitation. Burns 2014, 40, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, U.; van Niekerk, A. Restorying the self: An exploration of young burn survivors’ narratives of resilience. Qual. Health Res. 2011, 21, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Evaluation of the posttraumatic growth inventory after severe burn injury in Western Australia: Clinical implications for use. Disabil. Rehabil. 2016, 38, 2398–2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Social challenges of visible scarring after severe burn: A qualitative analysis. Burns 2017, 43, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, S.; Elliott, C.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F.; Girdler, S. Paediatric burns: From the voice of the child. Burns 2014, 40, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McLean, L.; Rogers, V.; Kornhaber, R.; Proctor, M.-T.; Kwiet, J.; Streimer, J.; Vandervord, J. The patient–body relationship and the “lived experience” of a facial burn injury: A phenomenological inquiry of early psychosocial adjustment. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2015, 8, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moi, A.; Gjengedal, E. Life after burn injury: Striving for regained freedom. Qual. Health Res. 2008, 18, 1621–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neill, J.; Goch, I.; Sullivan, A.; Simons, M. The role of burn camp in the recovery of young people from burn injury: A qualitative study using long-term follow-up interviews with parents and participants. Burns 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.R.; Davey, M.; Klock-Powell, K. Rising from the Ashes. Soc. Work Health Care 2003, 36, 53–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H. What does posttraumatic growth mean to Chinese burn patients: A phenomenological study. J. Burn Care Res. 2010, 31, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagnild, G.; Young, H. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1993, 1, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Block, J.; Kremen, A. IQ and ego-resiliency: Conceptual and empirical connections and separateness. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 349–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiew, C.; Mori, T.; Shimizu, M.; Tominaga, M. Measurement of resilience development: Preliminary results with a state-trait resilience inventory. J. Learn. Curric. Dev. 1.

- Tedeschi, R.; Calhoun, L. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Meauring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.; Tedeschi, R.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsky, T.; Triplett, K.; Danhauer, S. A short for of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillen, J.; Fisher, R. The Perceived Benefit Scales: Measuring perceived positive life changes after negative events. Soc. Work. Res. 1998, 22, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badger, K.; Royse, D. Helping others heal: Burn survivors and peer support. Soc. Work Health Care 2010, 49, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dirik, G.; Karanci, A. Variable related to posttraumatic growth in Turkish rheumatoid arthritis patients. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2008, 15, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manne, S.; Ostroff, J.; Winkel, G.; Goldstein, L.; Fox, K.; Grana, G. Posttraumatic growth after breast cancer: Patient, partner, and couple perspectives. Psychosom. Med. 2004, 66, 442–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janoff-Bulman, R. Posttraumatic growth: Three explanatory models. Psychol. Inq. 2004, 15, 30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Milam, J. Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. J. Appl. Psychol. 2004, 34, 2353–2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Xu, J.; Liu, D. The relationship between post traumatic stress disorder and post traumatic growth: Gender differences in PTG and PTSD subgroups. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2014, 49, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi-Kashani, F.; Vaziri, S.; Akbari, M.; Kazemi-Zanjani, N.; Shamkoeyan, L. Predicting post traumatic growth based upon self-efficacy and perceived social support in cancer patients. Iran. J. Cancer Prev. 2014, 7, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Knudson-Cooper, M. Adjustment to visible stigma: The case of the severely burned. Soc. Sci. Med. Part B Med. Anthropol. 1981, 15, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Year and Country | Aim | Study Design | Study Population (n, Age, Gender %) | Burn Characteristics (TBSA %, Time since Burn) | Outcome Measures | Statistical Analyses | Findings | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ajoudani, F.; Jafarizadeh, H.; Kazamzadeh, J. 2019 [19] Iran | To investigate the relationship between social support and posttraumatic growth (PTG) in Iranian burn survivors, as mediated by their perceptions of spiritual well-being. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 102 Male %: 40 Age (SD): 27.5 (8.14) | TBSA: mean (SD): 32.9 (6.1) Time since burn: Not reported (Study inclusion criteria >1year post burn). | Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), Spiritual Well-Being Scale, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) | Descriptive statistics, univariate analyses, Pearson’s correlation test, Anderson and Gerbing’s two-step modelling procedure, chi-square test, comparative fit index, root mean square error of approximation, Tucker-Lewis fit index, standardised root mean residual | PTGI 78.13 (range 0–105). Social support 56.96 (range 12–84). Spirituality 92.15 (range 20–120). Positive correlation between PTGI and TBSA (r = 0.44, p = 0.01). PTGI scores different by education level category (F = 3.02; p = 0.03). Positive correlation between PTGI and social support (r = 0.332, p < 0.01) and spirituality (r = 0.371, p < 0.01). Positive correlation between social support and spirituality (r = 0.442, p < 0.01). The effect of social support on PTG decreased when spirituality included in model (b = 0.21, p < 0.001) | Burn survivors who perceived a higher level of social support experienced greater PTG. It was proposed that perceived social support is a key element for the psychological adjustment of burn survivors. The mediating role of the spirituality suggests that social support increases PTG, both directly and indirectly. There is a positive association between TBSA scores and PTGI scores. Improving social support and spiritual wellbeing might be an effective strategy for enhancing PTG among burn survivors. |

| Baillie, S.E. Sellwood, W. Wisely, J.A. 2014 [20] UK | To examine PTG using quantitative measures of growth, social support, coping styles and dispositional optimism to determine the potential predictors of PTG. To assess quality of life, and to clarify the relationship between PTG and distress. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 74 Male %: 42 Age mean (SD): 45.7 (17.11) | TBSA mean (SD): 9.4 (SD not reported) Time since burn mean: 69 weeks (range 4–624 weeks) | PTGI, Coping with Burns Questionnaire (CBQ), MSPSS, The Impact of Event Scale-Revised, BSHS-B40, Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) | Descriptive statistics, t-tests, one-way ANOVA, correlations, hierarchical linear (stepwise) regression analysis, scatter plots. | PTGI and TBSA were positively correlated (r = 0.47, p < 0.01). PTGI scores and time since burn positively correlated (r = 0.34, p < 0.01). Burns involving both hands and face = 2.86, (95%CI 2.13, 3.79) reported more growth than burns to the body 1.01 (95%CI 0.70, 1.39) or face only 1.15 (95% CI 0.45, 2.20). Positive correlation for PTG scores with PTS (r = 0.32, p < 0.01) and PTG scores with social support (r = 0.22, p < 0.05). Avoidance coping associated with PTG (r = 0.43, p < 0.01). PTG scores higher with more avoidance coping (b = 0.581, p = 0.001). greater TBSA (b = 0.132, p = 0,002) more instrumental/action coping (b = 0.495, p = 0.005), more social support (b = 0.407, p = 0.005). | The process of growth emerges from distress, aided by coping styles and social support. Burns involving the face and hands reported more growth The more severe the burn the more growth experienced. More PTG with more time postburn. Facilitating growth through narrative may be beneficial. Patients could also be assisted to establish or renew meaningful social support networks. |

| Bibi, A; Kalim, S; Khalid, M.A. 2018 [21] Germany | To investigate the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms and resilience among burn patients in Pakistan and exploring the influence of gender. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 70 Male %: 49 Age median (IQR): 27.5 (IQR 13) | TBSA categorsied. Range 10–30%. Time since burn not reported. | PTSD CheckList-Civilian Version (PCL-C), Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) | Descriptive statistics, Spearman’s Rank-Order correlation, ANCOVA | A strong negative correlation between PTSD and resilience among burn patients (r = −0.72, p < 0.001). A significant effect of gender on PTSD among burn patients F (1, 64) = 14.22, p < 0.001; η2 = 0.18). A significant effect of gender on resilience among burn patients (F (1, 64) = 22.03, p < 0.001 (η2 = 0.25)). Females had generally lower resilience than males. | Low levels of resilience are associated with higher symptoms of PTSD. Females had more severe PTSD symptoms and lower resilience than males; likely due to cultural factors and differing peer supports for men and women in Pakistan. Culture-based rehabilitation strategies should be planned Improving optimism and faith could also help. |

| Chen, Y.; Lu, M.; Weng, L.; Huang, P.; Wang, C.; Pan, H. 2020 [22] Taiwan | To explore the relevant factors affecting resilience in burn patients who had experienced the Formosa Fun Coast Explosion. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 30 Male %: 63 Age mean (SD): 22.8 (4.30) | TBSA mean (SD): 45 (16.4) Time since burn not reported (Study inclusion criteria was 3–5 months post burn). | Resilience Scale, Perceived Stress Scale | Descriptive statistics, Kolmogorov-Smirnox test, Pearson correlation, t-test, one-way ANOVA, Scheffe’s post hoc test, Kendall’s tau coefficient, Mann-Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test, multivariate linear regression. | Resilience score 132.7 (moderate). Stress 25.4. Every 1-point increase in stress level decreased resilience by 1.69 points in the stepwise regression. | Perceived stress was the key predictor of resilience: The higher the level of stress, the lower the resilience in participants. Screening recommended to determine stress levels for targeted intervention. |

| He, F.; Cao, R.; Feng, Z’.; Guan, M.; Peng, J. 2013 [23] China | Investigation into the effects of dispositional optimism and psychological resilience on the subjective wellbeing of burn patients. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 410 Male %: 75 Age mean (SD): 25.2 (2.76) | TBSA not reported (Study inclusion criteria was 20–40% TBSA). Time since burn not reported. | LOT-R, CD-RISC, Subjective Wellbeing Scale | Anderson and Gerbing’s two-step modelling, chi-square, root mean square tests, Bootstrap estimation procedure, confirmatory factor analysis. | The effect of dispositional optimism on wellbeing through psychological resilience was 17.9%. Dispositional optimism and psychological resilience had a direct effect on subjective wellbeing. and an indirect effect on subjective wellbeing through psychological resilience. | Burn patients with high optimism are more likely to be capable of recovering from stressful situations. Dispositional optimism and psychological resilience act as protective factors, increasing the ability of burned patients to recover from their injury. |

| Hwang, S.; Lim, E.; 2020 [25] Korea | To identify the differences in the level of depressive symptoms, social support, and PTG among patients with severe burns by treatment phase and the factors associated with PTG in the acute and rehabilitation phases. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 179 Male %: 78 Age mean (SD): 45.8 (12.89) | TBSA (SD): 19.3 (17.17) Acute phase: 16.7 (14.63) Rehabilitation phase: 20.9 (18.44) Time since burn not reported for overall population, broken down into groups Acute phase: 64 days * Rehabilitation phase: 685 days * | Becks Depression Inventory II, Social Support Scale (SSS), PTGI, a general characteristic survey | Descriptive statistics, Chi-square test, t-tests, Pearson’s correlation coefficients, regression analysis. | Acute group: PTGI 44.13 (SD 15.01). Depression 15.93 (SD 9.68). Rehabilitation group: PTGI 40.32 (SD 15.71). Depression 20.55 (SD 13.31). PTGI and depression negatively correlated in both groups, Acute: r = −0.257 (p = 0.035) Rehabilitation: r = −0.378 (p < 0.001) PTGI and social support positively correlated for both groups. Acute: r = −0.4017 (p = 0.001) Rehabilitation: r = −0.510 (p< 0.001) | There is an inverse correlation between depression and PTG. There are differences in depressive symptoms in burn survivors’ dependent on their phase of treatment. The first-year post burn incident is when individuals are most susceptible to., depression. Burn patients management of depressive symptoms, in the acute and rehabilitation phase. Social support is protective Contemplative processes may lead to PTG. |

| Jang, M.; Park, J.; Chong, M.; Sok, S. 2017 [26] Korea | To examine and identify the factors influencing the degree of resilience among Korean burn patience. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 138 Male %: 67 Age mean (SD): 46.8 (5.43) | TBSA mean not reported for overall sample. <29: 113 (81.8) 30–39: 7 (5.1) 40–49: 7 (5.1) 50–59: 5 (3.6) >60: 6 (4.4) Time since burn not reported. | Korean adaption of the Resilience Scale, Beck Depression Inventory, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Self-Esteem Scale, Family Support Scale | Descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlations, multiple regression analysis | Resilience (SD): 86.15 (11.70). Positve correlation for resilience with self-esteem (r = 0.524, p < 0.001) and resilience with family support (r = 0.523, p < 0.001). Negative correlation for resilience with depression (r = −0.496, p < 0.001) and resilience with anxiety were negatively correlated (r = −0.541, p < 0.001) Self-esteem (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), and family support (β = 0.29, p < 0.001) predicted resilience. | Anxiety, self-esteem, family support, educational level, income, and family support affected resilience. Depression was a major contributor to poor self-perception and positive outlook. |

| Jibeen, T.; Mahfooz, H.; Fatima, S. 2018 [27] Saudi Arabia | To examine the associations between personality traits, spiritual transcendence, positive change, and psychological distress in a burn sample. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 96 Male %: 71 Age mean (SD): 30.4 (13.08) | TBSA mean not reported, (Study inclusion criteria: 20–80%) Time since burn not reported. | NEO Five-Factor Inventory, Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21), Spiritual Transcendence Index, Perceived Benefits Scales | Correlations, stepwise regression analyses | Positive correlation for perceived benefits with extraversion, spirituality. Negative correlation of perceived benefits with distress and neuroticism (p values not stated). Positive change was predicted by longer LOS, less spirituality, more neuroticism, and less extraversion. Distress was predicted by longer LOS, less spirituality, more neuroticism, and less extraversion. | Spiritual transcendence in burn patients is likely to protect them from negative consequences of burn trauma and promote PTG, which may lead to successful adaptation. Neuroticism positively predicts psychological distress and negatively predicts positive change. Extraversion negatively predicts psychological distress and positively predicts positive change. Those with neurotic traits may be less likely to benefit from spiritual transcendence to reduce psychological distress, while those manifesting extrovert traits may be more likely to benefit. |

| Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. 2017b [18] Australia | To determine the nature of the relationship between growth, stress, and quality of life post burn (via the health-related quality of life outcome measures), and whether PTG changed over time in individuals who have sustained a burn. | Longitudinal cohort study | n = 73 Male %: 69 Age (SD): 43.0 (14.00) Non-acute group: Age 41.8 (14.5) Acute group: Age 44.3 (13.5) | TBSA (SD): 18.5 (20.10) Non-acute: 32.7 (21.20) Acute group: 6.1 (5.90) Time since burn Non-acute: >6 months Acute group: <6 months | SF-36 Quality of Life, BSHS-B40, PTGI, DASS-21 | Longitudinal regression analysis, chi-square, Wilcoxon Rank Sum (Mann-Whitney) tests, multiple linear regression analysis, t-tests. | PTG did not differ between gender, age at injury, time since injury, marital status or Australian born. TBSA had a positive effect on total PTGI scores that was close to significance. DASS-21 curvilinearly associated with PTGI highly significant (b = 1.3, p < 0.0001, rho = 0.76). More growth was reported at moderate levels of total DASS-21 scores, with this reducing at higher levels of depression. | PTG associated with higher levels of stress. Less PTG occurs as mental health and mood improve. Depression is a barrier to growth. possibly inhibiting the ability to use helpful thinking styles, reducing motivation, and disrupting the capacity to cope. This urges the need for early identification, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Growth scores are highest at moderate levels of recovery, then reduce again while recovery continues as burn survivors return to work and resume everyday life. Returning to work is significant in psychological recovery after burn. |

| Martin, L.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. 2021 [17] Australia | To assess the relationship between coping styles and PTG in an adult burn population. | Longitudinal cohort study | n = 36 Male %: 64 Age (SD): 43.0 (15.26) | TBSA (SD): 11.5 (11.35) Time since burn : 233 days | BriefCOPE, PTGI, DASS-21 | Descriptive statistics, univariate regression analysis, multivariate regression analysis. | PTG is expected to increase by 2.0 units for every unit increase in acceptance, and by 1.7 for every unit increase in positive reframing, and by 2.3 for every unit increase in religious coping strategies. Depression is expected to increase by 1.3 units for every unit increase in behavioural disengagement, and by 0.7 for every unit increase in self-blame, and by 0.6 for every unit increase in venting. | Three “approach” coping strategies were predictors of PTG: positive reframing, acceptance and use of religion. “Avoidant” coping venting, self-blame, and behavioural disengagement were predictive of depression after burn. Coping mechanisms associated with depression can be used as ‘red flags’ for early depression screening. Coping mechanisms associated with PTG can be used in interventions (i.e., providing pastoral support to burn patients). Depression screening can indicate those in need of support. |

| Masood, A.; Masud, Y.; Mazahir, S. 2016 [28] Pakistan | To explore gender differences in resilience and psychological distress of patients with burns. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 50 Male %: 50 Age categorised. Mean (SD): unclear. Range 16–48 years | TBSA not stated Time since burn not stated (criterion >6m postburn) | State-Trait Resilience Inventory; Psychological distress scale | Descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation, t-test, linear regression. | Mean resilience for males was higher than females for each of the four types of resilience (interstate, intrastate, intertrait, and intratrait). Mean levels of psychological distress were higher for females reaching statistical significance. Lower levels of intrastate, intertrait, and intratrait resilience and higher levels of interstate resilience predicted psychological distress, | Women show less resilience than men after trauma, and show more distress. This is interpreted from the following bservations: Inner strength (Intratrait) is higher in males than women. The positive relationship between interstate resilience and intrastate resilience in males is indicative of more social support. Males have wider social support networks than females in Pakistan and because of the social structure. |

| Quezada, L.; Gonzalez, M.T.; Mecott, G.A’. 2016 [29] Mexico | To explore the roles of both the patient’s and caregivers’ resilience and PTS in paediatric burn survivor adjustment. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 51 Patients: Male n = 29 Age (SD): 12.0 (3.00) Caregivers: Male n = 12 Age (SD): Females: 36.9 (7.13) Males: 45.8 (8.9). | TBSA (SD): 31 (19.00) Time since burn mean: 6 years (4.14) | Resilience Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents, Mexican Resilience Scale for Adults, Davidson Trauma Scale | Spearman’s correlation, structural equation modelling, Tucker-Lewis index, comparative fit index, root mean square error of approximation | Patients: Resilience scores (SD) 128.3 (21.63) range 105 to157. Caregivers: Resilience scores (SD) 141.43 (19.42) range 75 and 168. For patients: More resilience negatively correlated with age at burn r = −0,414, p > 0.001), was also a predictor of resilience. Higher levels of female caregiver avoidance and intrusion symptoms negatively impact child resilience (r = 0.389. p < 0.05). | Higher resilience in paediatric burn survivors associated with being younger at the time of the burn. Caregiver PTS intrusion symptoms were the second-best predictor of patient resilience. The higher the resilience in caregivers, the lower their avoidance symptoms, which further results in a lower severity of intrusion symptoms. Psychological responses of caregivers affect wellbeing and positive adjustment of patients; thus, psychological services for caregivers would likely have a dual benefit for both caregivers and patients. |

| Rosenbach, C. & Renneberg, B. 2008 [30] Germany | To investigate PTG in burn patients after discharge from the hospital for acute treatment, and to identify correlates facilitating or preventing the acceptance of positive change. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 149 Male %: 57 Age mean (SD): 44.0 (14.40) | TBSA mean (SD): 32.2 (18.10) Time since burn mean: 4 years | PTGI, CBQ, Symptom Checklist, SSS, SF-12 | Pearson’s correlations, multiple hierarchic linear regressions, | Active coping was the strongest predictor of PTG.. Women reported significantly higher levels of PTG than men. Older adults (53–88 years) reported the highest levels of PTG (M = 3.47, 44–52 years; M = 2.99, 37–43 years M = 3.21, 16–36 years, M = 3.09). Participants reported that they used more active problem-focused coping strategies than avoidant coping-strategies (t = 11.64, df = 147, p < 0.001). No gender differences regarding coping, social support, or emotional distress. Injury severity was not associated with PTG. | The PTG in the sample was pronounced regarding more Appreciation of Life, enhancement of Relationships with Others, and greater sense of Personal Strength. The use of active coping strategies and a higher level of perceived social support were found to be strongly associated with more PTG, with this being an intervention avenue that ought to be considered by treatment teams. Distress and growth can co-exist. |

| Royse, D. & Badger, K. 2017 [31] USA | To investigate the occurrence of near-death experiences in burn survivors and its possible effects on PTG and life satisfaction following injury. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 92 Male %: 53 Age mean (SD): 47 years (SD not reported) range 21–80. | TBSA mean (SD): 46.0% (SD not reported) range 1–95%. Time since burn mean: 26.8 (SD not reported) Near death experience group: 13.3 (SD not reported) Non-near death experience group: 13.6 (SD not reported) | Near Death Experience Scale (NDES), SLS, Posttraumatic Growth Inventory- Short Form (PTGI-SF) | One-way ANOVA, t-tests | Burn survivors who indicated that their religion was not a source of strength and comfort to them had the lowest scores on the NDES (F = 3.1, df = 2.91, p = 0.05), and those that indicated that their religion was a source of strength and comfort to them (“a great deal” vs. “a little” or “none”) had the highest scores on life satisfaction (F = 5.97, df = 2,86, p = 0.004). PTGI-SF scores were positively correlated with TBSA (r = 0.24, p = 0.02). | No significant correlations between level of PTG and years since injury, age, or gender. Findings reflected a positive association of PTG with injury severity when the sample was divided to <30 or >30% TBSA. Religion/spiritually acts a protective factor and supports PTG. Helping professions should integrate the role of religion/spiritually into their interventions, and training around how to do so should be provided. |

| Waqas, A.; Nabveed, S.; Bhuiyan, M.M.; Usman, J.; Inam-al-Huq, A.; Cheema, S.S. 2016 [32] Pakistan | To investigate and compare ego resiliency levels and the degree of social support in patients with a burn injury and their healthy counterparts. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 160 burn n = 80 control n = 80 Male %: 24 Age mean (SD): 34.9 (11.20) | TBSA mean not reported. Time since burn mean (SD): 6.3 (4.70) | Urdu version of the Ego Resilience Scale, MSPSS | Descriptive statistics, chi-square test, t-test, point biserial correlations | Ego resiliency score (SD): 2.82 (.63). There were no significant differences in mean scores on ego resiliency scale between the burn patients and their healthy counterparts. Patients with a burn injury were associated with lower scores on the MSPSS (r = 0.455, p < 0.001). They reported lower scores on social support from their significant other and family and friends in comparison to their healthy counterparts. | Lack of social support among burn patients can negatively influence their survival, physical and mental health. The care of burn patients should involve families, significant others, and friends.. Resources should educate social supports on the physical and mental health effects of burn injuries as this could improve the clinical outcome of burn patients. |

| Xia., Z.; Kong, Y.; Yin, T.; Sji, S.; Huangm, R.; Cheng, Y. 2014 [33] China | To investigate the impact of acceptance of disability and psychological resilience on PTSD in patients with burns. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 127 Male %: 67 Age mean (SD): Overall age not reported. Age categorised. Range 18–60 | TBSA mean not reported. (Study inclusion criteria: second-degree burns with tbsa >10% or third-degree burns with tbsa >5%). Time since burn not reported. | PCL-C, Acceptance of Disability Scale, CD-RISC | T-tests, ANOVA, descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlations, multiple regression analysis | Resilience was negatively correlated with re-experiencing (r = −0.251, p < 0.001), avoidance/numbing (r = −0.316, p < 0.001), hyperarousal (r = −0.212, p < 0.001), and total PTSD scores (r = −0.308, p < 0.001). Lack of self-improvement was a predictor for PTSD (p = 0.002). | Trauma negatively affects resilience, and resilience is required for PTSD prevention. Lack of self-improvement was a predictor for PTSD. |

| Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, B.; Zeng, Y.; Ms, H. 2014 [34] China | To investigate factors that influence resilience in patients with burns during rehabilitation, and to provide theoretical guidance for psychological crisis prevention and intervention. | Analytical cross-sectional | n = 129 Male %: 81 Age (SD): 34.2 (10.22) | TBSA mean (SD): not reported, Categorised into mild (n = 53), moderate (n = 55), severe (n = 21). Time since burn mean: not reported | CD-RISC, SSS, Simplified Coping Styles Questionnaire | Descriptive statistics, t-tests, ANOVAs, rank sum test, Pearson’s correlation, linear regression analysis, multivariate regression analysis | Patients with severe burns: Higher resilience (F = 3.10, p = 0.049) Higher tenacity (F = 3.48, p = 0.034) Higher strength (F = 3.64, p = 0.029) Females—more resilience and optimism Divorcees—more strength Age, income and education—not difference in resilience. Optimism and social support correlated (r = 0.295, p < 0.01). | The level of resilience in females. Social support may enable patients to have an optimistic attitude during treatment, supporting resilience. Psychological intervention should include guidance with coping strategies. This should include helping to change the individual’s environment, encouraging active acceptance of lifedtyle changes, and helping them to improve their resilience. |

| Authors, Year, and Country | Aim | Sample Size | Participant Age | Study Design | Age at Time of Burn | TBSA | Time since Burn | Intervention | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrams, T.E.; Ratnapradipa, D.; Tillewein, H.; Lloyd, A.A. 2018 [35] USA | To investigate the holistic health of adult patients who had sustained major burn injuries. | n = 8 (7 male) | Mean 54.38 years Range 18–65 years | Heuristic phenomenological study | Mean 42.38 years | Range 20–98% | Mean 9.3 years | Not applicable | Four themes (1) Problem-solving skills (2) Social competence (3) life purpose (4) autonomy |

| Badger, K. & Royse, D. 2010 [36] USA | To explore perceptions of peer support in recovery. | n = 30 (19 male) | Mean = 41 (SD = 10.9) Range 19–71 years | Kvale’s (1996) model for a qualitative interview investigation | Not reported | Mean 60% (SD 20.76) range 25–93% | Mean = 14 years (SD = 13) | Peer support | Six themes (1) Positive regard for peer support (2) provision of hope and perspective (3) experience of belonging and affiliation (4) emotional cost (5) helping other’s helps oneself (6) mental preparedness to reach out |

| Garbett, K.; Harcourt, D. & Buchanan, H. 2017 [37] United Kingdom | To build on current research by qualitatively exploring the positive outcomes that may be present following a burn. | n = 10 | Not reported | Thematic analysis of longitudinal blog data | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not applicable | Three themes (1) Shift in self-perception (2) enhanced relationships (3) change in life outlook |

| Habib, Z.; Saddul, R.; Kamran, F., 2021 [38] Pakistan | To explore the perceptions and experiences of female burn survivors with Facial disfigurement in Pakistan. | n = 5 (all female) | Median 25 years (range 19–45 years) | Thematic analysis | Range 4–22 years | Not reported | Not reported | Not applicable | Physical appearance: Perceived stigmatization, self-perception and perception of others. Posttraumatic growth: sense of achievement, satisfaction and improved QoL. Acceptance, gratitude, optimism. Relationships: importance of good family support. Coping strategies: venting, religion, enduring. |

| Han, J.; Zhou, X.; Liu, J.; Yue, P.; Gao, L. 2020 [39] China | To explore resilience development in patients who have suffered a burn injury. | n = 10 (6 male) | Range = 19–44 | Grounded theory | Not reported | Range 16–50% | Not reported | Five stages (1) black hole (2) introspection (3) integration (4) practice (5) growth Internal factors: Hope, sincerity, will, belief, curiosity. External factors: caring, support, sharing relationships. Ci = omitted relationships, and intimate relationships | |

| Hunter, T.A.; Medved, M.I.; Hiebert-Murphy, D. Brockmeier, J.; Sareen, J.; Thakrar, S.; Logsetty, S.. 2013 [40] Canada | To contribute to a more complex understanding of survivors’ experiences through exploring the narratives and counter-narratives told by women who have experienced burn injury. | n = 10 (all female) | Mean = 45 Range 18–82 | Narrative analytic method | Not reported | Mean = 8.75% Range 1–30% | Within 5 months of burn | Not applicable | The primary narratives were (1) “I don’t find it a problem” (2) not being ashamed to show others their scars and (3) not wanting to worry others. |

| Kornhaber, R.; Wilson, A.; Abu-Qamarm M.Z.; McLean, L. 2014 [42] Australia | To explore the concept from the lived experience about how burn survivors acknowledge and accept their burn injury. | n = 21 (20 male) | Average age 44y (range 21–65 years) (not stated if mean or median) | Qualitative phenomenological inquiry using semi-structured interviews and Colaizzi’s thematic analysis method. | Average TBSA 55% (range 20–90%) (not stated if mean or median) | 6 months to 8 years | Not applicable | Acknowledgement (1) reasoning (gratefulness, downward comparison) (2) humour (3) the challenge of acceptance (4) self-awareness (confronting altered appearance) | |

| Lau, U. & van Niekerk, A. 2011 [43] South Africa | To explore how young burn survivors define themselves and how the burn influences their worldview. | n = 6 (4 male) | Mean 19 years (range 14–24 years) | Interpretative social constructionism narrative approach | Not reported | Not reported | Not directly reported. >2 years postburn 3 as young children, 3 as (pre)adolescent | Not applicable | (1) The struggle for recognition—the self as both highly visible and invisible (2) Reconciling or rediscovering the self (3) Turning points: The search for meaning |

| Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. 2016 [44] Australia | To assess presentation of PTG after burn. To assess the use of the PTGI in burn patients. | n = 17 (64% male) | Median age Was 48 years (range 21–75 years) | Mixed method convergent parallel comparative approach. Qualitative semistructured interviews followed by comparison of previously collected quantitative PTGI responses. | Not reported | Median TBSA of 30% (range 15–85%) | Median Of 8 years post-burn (range 2–33 years) | Not applicable | Interpersonal relationships Trust and loyalty; Emotional transparency Independence vs dependence; Compassion Community support; Feelings of burden New possibilities Work-life balance; Recreation and leisure Citizenship (community contribution) Personal strength Gratefulness, planning, humour; Increased personal strength; Determination for independence Acceptance and will to move forward Spiritual change Used if existing faith only Appreciation of nature Better understanding of cycle of experiences (ie philosophical changes not spiritual changes) Appreciation of life Survival—gratitude; Wellbeing Accepting a new normal Use of time (life is short, live in the present) Value of relationships |

| Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. 2017 [45] Australia | To investigate adult burn survivors experience of visible scarring as barrier to PTG. | n = 16 (62% male) | Mean age of 46 years (SD 16.7; Range 18–61 years) | Qualitative phenomenological inquiry using semi-structured interviews using Tesch’s coding method. | Not reported | (TBSA) of 39.6 (SD 20.3; range 15–85%). | More than 2 years | Not applicable | Emotional barriers to growth (1) fear of rejection, (2) self-consciousness, and (3) embarrassment or humiliation. Situational barriers to growth (1) Inquisitive questions (2) obligation to explain Behavioural barriers to growth (1) Reactions of others (2) Pressure garments Coping strategies used Avoidant coping—avoidance of eye contact, closed body language etc. Active coping—humor, gratefulness, importance of relationships Discussion—risk of social isolation |

| McGarry, S.; Elliott, C.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F.; Girdler, S. 2014 [46] Australia | To explore the experience of children with burns. | n = 12 (6 male) | Range 8–15 years | Qualitative phenomenological inquiry using semi-structured interviews and Colaizzi’s thematic analysis method. | Range 1–20% | 6 months | Not applicable | (1) the burn trauma (2) the recovery trauma Six themes (1) ongoing recurrent trauma; (2) returning to normal activities (3) behavioural changes; (4) scarring—permanent reminder; (5) family (6) adaptation—stronger, confidence, not letting small things bother them, resilience (or acceptance | |

| McLean, L.M.; Rogers, V.; Kornhaber, R.; Proctor, M.; Kwietm J.; Streimer, J.; Vandervord, J. 2015 [47] Australia | To examine the early recovery lived experience for patients with a facial burn. | n = 6 (4 male) | Mean age 43 years (range 29–55 years) | Qualitative phenomenological inquiry using semi-structured interviews (Burns modified adult attachment interview) and Colaizzi’s thematic analysis method. | 16.3% (0.8–55) | Interviewed within 4 months of burn [5 interviewed as inpatients, 1 within 4 months of injury LOS 20.3 days (range 3–60 days)] | Not applicable | Relationship to self/other—early self-image change and increased bodily awareness, change to interpersonal relationships (66%), altruism (100%). Coping—hopefulness about recovery (100%), positive rationalisation (66%), resilience, reflective appraisal, humour (100%). Meaning-making—retelling the tale, fear, panic, shock (83%), making sense of the accident (100%), history of previous trauma (100%), spirituality to find meaning (66%). | |

| Moi, A.L. & Gjengedal, E. 2008 [48] Norway | To describe meanings in experience of life after Major burn injury. | n = 14 (11 male) | Mean 46 years (range 19–74) | Husserlian phenomenological Perspective, descriptive, Search for Meaning For a given context | Not reported | Mean TBSA 33% (range 7.5–62%) | Mean 14 m (range 5–35 m) | Not applicable | Facing the extreme—vigilance, action, need for assistance. A disrupted life history—creating coherence. Accepting the unchangeable—enduring, grief, fatalism, comparisons with others, and new feelings of gratefulness. Changing what is changeable—personal goals, independence, relationships with others, and a meaningful life, Regain freedom’ |

| Neill, J.T.; Goch, I.; Sullivan, A.; Simons, M. 2021 [49] Australia | To explore the experience and longer term psychosocial impacts of burn camps. | n = 23 [patients n = 8. Parents n = 15 (subset of matched pairs n = 6)] | Median 11.2 year (range 8.1–14.9) | Inductive reflexive thematic analysis with pooled interview data from semistructured interviews with parents and children/adolescents | Birth—13 years (median 4.75 years) | Not stated | 3 day burn camps | Camp experience (1) fun, adventurous activities, (2) social relatedness (3) camp setting and experience (4) acceptance Program outcomes (1) normalising experiences (2) social support (3) psychological recovery (4) confidence. | |

| Williams, N.R.; Davey, M.; Klock-Powell, K. 2003 [50] USA | To explore the experience of recovery, and the influencing personal and environmental factors. | n = 7 (3 male) | Median age 40 years (range 31–52 years) | Phemenological analysis of semi-structured interviews | median age 32 years range 2–42 years | TBSA reported for 3 injuries, range 35–95% | Influences Construction of reality Time since injury Age when injured Themes Losses Gains/refaming Adaptation and coping with change Relationships with others | ||

| Zhai, J.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Jiang, H. 2010 [51] China | Do Chinese burn patients experience PTG? Are there PTG aspects not captured by PTGI? What common and unique factors facilitate PTG? | n = 10 (7 male) | Mean age 35y (range 24–48 years) | Qualitative, hermeneutic phenomenology, using semi-structured interviews | TBSA mean 69% (range 11–90) | Time since burn mean 2.8 years (range 5 months to 6.5 years) | Not applicable | PTG is ongoing process not a goal Process—need to manage emotions for cognitive processing to occur. Social system important. Effective coping style adequate abreaction, downward social comparison and seeking social support. For significant others— Meaning making Presentation of PTG Personal strength, new life philosophy; sharing of self; altruism born of suffering No spiritual religious growth reported by 90% of participant |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Woolard, A.; Bullman, I.; Allahham, A.; Long, T.; Milroy, H.; Wood, F.; Martin, L. Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth after Burn: A Review of Barriers, Enablers, and Interventions to Improve Psychological Recovery. Eur. Burn J. 2022, 3, 89-121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010009

Woolard A, Bullman I, Allahham A, Long T, Milroy H, Wood F, Martin L. Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth after Burn: A Review of Barriers, Enablers, and Interventions to Improve Psychological Recovery. European Burn Journal. 2022; 3(1):89-121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleWoolard, Alix, Indijah Bullman, Amira Allahham, Treya Long, Helen Milroy, Fiona Wood, and Lisa Martin. 2022. "Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth after Burn: A Review of Barriers, Enablers, and Interventions to Improve Psychological Recovery" European Burn Journal 3, no. 1: 89-121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010009

APA StyleWoolard, A., Bullman, I., Allahham, A., Long, T., Milroy, H., Wood, F., & Martin, L. (2022). Resilience and Posttraumatic Growth after Burn: A Review of Barriers, Enablers, and Interventions to Improve Psychological Recovery. European Burn Journal, 3(1), 89-121. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj3010009