Abstract

We use 29 years of altimeter-derived sea level anomalies and geostrophic velocities (1993–2021) from the Copernicus Marine Service to identify the Mexican Coastal Current (MCC) and to examine how it interacts with the coastline. Variance-ellipse and empirical orthogonal function analyses isolate a narrow alongshore jet with a mean width of about 95 km and average speeds near 0.3 m that reverses direction semiannually: poleward in June and July and equatorward in the rest of the year. When the MCC impinges on broad concavities in the coast, the boundary layer separates, forming recirculation cells that intensify and detach as coherent eddies. These near-shore eddies have similar radii (from ∼30 km) and relative vorticity of at the beginning of their generation, and they propagate offshore once the current weakens. A simple numerical model reproduces the observed behavior and suggests that eddy formation is controlled by flow separation rather than generic instability. The semiannual change in direction of the MCC indicate a link with the larger-scale North Equatorial Countercurrent and Costa Rica Coastal Current systems of the eastern tropical Pacific.

1. Introduction

Coastal currents are integral components of the ocean circulation because they transport heat, salt and biologically important properties such as larvae and chlorophyll along the continental margin. These transports underpin the productivity of coastal fisheries and the health of local ecosystems; therefore, understanding their dynamics and variability is essential to quantify water-mass exchange and evaluate their ecological and climatological impacts. The eastern Pacific hosts several well-studied boundary currents: the Alaskan and California Currents in the north [1,2,3] and the Peru–Chile Current to the south [4]. Between these systems lie two lesser-known jets—the Costa Rica Coastal Current and the Mexican Coastal Current (MCC), whose dynamics and instabilities warrant further attention [5]. In boreal summer a narrow coastal jet develops along the Southwest Mexican Pacific (SMP) between roughly 14° N and 20° N. Early descriptions referred to it as the Mexican Current or West Mexican Current [6,7]. Hydrographic surveys in June 2003 and June 2005 documented a jet 90–180 km wide, 250–400 m deep and flowing at 0.15–0.30 m [8]. A three-dimensional numerical model later showed that the jet reverses during the year, flowing poleward in summer and equatorward in spring and autumn [9]. This coastal current is of particular interest because it lies on the pathway connecting the subtropical northeast Pacific with the equatorial Pacific, where El Niño and other large-scale climate events originate. Hence, the MCC may represent a regional expression of the larger-scale North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC) and Costa Rica Coastal Current (CRCC) systems and could serve as a seasonal bridge that transports properties between tropical and subtropical waters [10]. Despite its potential importance, many aspects of the MCC remain poorly known. In particular, numerous mesoscale eddies are observed in the SMP, but their formation mechanisms and relationship to the MCC have not been clearly identified. Satellite remote sensing has become a cornerstone of modern oceanography because it provides synoptic measurements over vast regions where in-situ coverage is sparse. Indeed, [11] reviews how sensors such as radar altimeters, scatterometers, synthetic aperture radar and infrared and optical radiometers can be used to map sea-surface height anomalies, surface currents and fronts, and even to detect mesoscale eddies. That overview underscores the value of altimeter-derived products for identifying boundary currents and motivates our use of the CMEMS sea level anomaly data to characterise the Mexican Coastal Current. In this study we revisit the problem using three decades of high-resolution altimetry and a state-of-the-art eddy detection algorithm to identify where and when eddies form near the coast. We demonstrate that the MCC interacts with concavities in the coastline to produce recirculations that detach as eddies. We then employ a high-resolution numerical model to explore the dynamical mechanisms by which the MCC generates eddies. Finally, we discuss how these processes fit into the broader context of tropical Pacific circulation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data

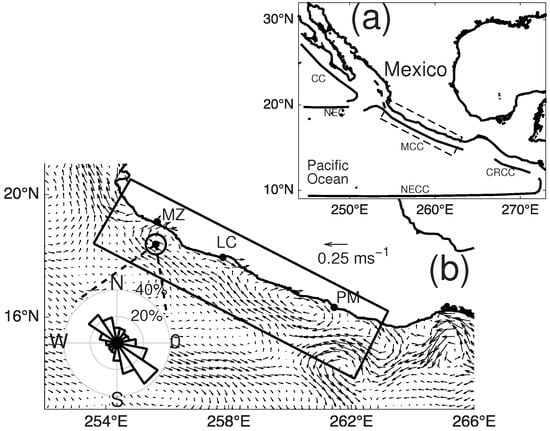

Our study focuses on the southwest Mexican Pacific, between 254°–264° E and 14°–20° N (Figure 1a). Ocean circulation in this region of the Eastern Tropical Pacific is characterized by the interaction and transition of multiple currents. In the north, the California Current (CC) flows from the pole and merges with the North Equatorial Current (NEC) to the west. In the southern are the eastward North Equatorial Countercurrent (NECC) and the Costa Rica Coastal Current, which flows along the coast of Central America toward the pole and transitions into the Mexican Coastal Current (MCC). Within this rectangle the coastline extends for approximately 1130 km, and for our purposes we consider the coastal ocean as a strip 200 km wide seaward (Figure 1b). We analyze the Global Ocean Gridded Sea Surface Heights and Derived Variables product [12] distributed by the Copernicus Marine Service (level 4, DOI 10.48670/moi-00145). This reprocessed product merges observations from the Topex/Poseidon, Jason-1, OSTM/Jason-2, Jason-3 and Sentinel 6A altimeters using the DUACS (Data Unification and Altimeter Combination System) processing chain and applies standard geophysical and instrumental corrections. Objective analysis provides daily fields of sea surface height (SSH) and mean sea level anomaly (MSLA) on a grid referenced to WGS 84. Unlike other sea-level products, DUACS attenuates the tidal signal without affecting mesoscale variability ([13]). Absolute geostrophic velocities (, ) and their anomalies (, ) are provided and were used in this study. We extracted MSLA and geostrophic velocities for 1993–2021 within the box 254°–264° E, 14°–20° N. Temporal means were subtracted to obtain time series anomalies, and these fields were analyzed to identify the MCC and to characterise the mesoscale eddies generated by its interaction with the coastline. Figure 1b shows the time-mean surface current and a polar histogram of the current direction at a representative location within the coastal strip. The histogram indicates that the currents are primarily aligned with the coastline and exhibit two predominant modes: a poleward mode and an equatorward mode. Figure 1b also highlights two zones of persistent anticyclonic circulation; one off Manzanillo, Colima (MZ), and the other off Punta Maldonado, Guerrero (PM), which we investigate in the following sections. Although satellite altimetry traditionally suffers from contamination and coarse sampling near land, recent efforts in coastal altimetry have significantly improved data quality within 20–30 km of the shoreline. The DUACS product used here benefits from dedicated retracking and correction algorithms and provides daily MSLA and geostrophic velocities on a 0.25° grid. This resolution (≈28 km at these latitudes) is sufficient to capture the broad-scale coastal jet but features smaller than the grid spacing may be underestimated or missed. Moreover, the derived velocities are geostrophic and do not represent ageostrophic components driven by winds or friction. We therefore interpret our results as representative of the large-scale, barotropic part of the coastal circulation and acknowledge that finer-scale processes may require higher-resolution data or in situ measurements.

Figure 1.

(a) Map of the study zone (black rectangle) in the southwest coast of Mexico and (b) mean velocity field from 1993 to 2021 with the polar histogram of velocity at one grid node at the core of the MCC.

Previous validation studies in similar regions (e.g., comparisons with tide gauges and current meters) support the reliability of this product for analyzing coastal currents, although caution is warranted when interpreting submesoscale features.

2.2. Eddy Detection

To identify ocean eddies and estimate their properties, we applied the Angular Momentum Eddy Detection and Tracking Algorithm (AMEDA). This method [14] combines physical and geometrical criteria to locate coherent vortices in gridded velocity fields. Detection begins by computing the local normalised angular momentum and identifying its maximums, subject to the requirement that the associated streamline is closed; each maximum corresponds the cores of potential eddies. AMEDA has proven effective for detecting mesoscale eddies arising from coastal current instabilities [15,16]. For each detected eddy, the algorithm returns (i) the center coordinates (, in degrees), (ii) the radius at which the azimuthal velocity attains its maximum magnitude and (iii) the relative vorticity (), among other physical variables. The radius is determined by sampling interpolated streamlines outward from the center until the maximum azimuthal velocity is reached. Before computing the angular momentum field, AMEDA refines the input velocity grid. The original gridded field is interpolated onto a finer mesh using cubic interpolation, typically increasing the spatial resolution by a factor of three so that there are about three points per baroclinic deformation radius. This refinement provides a sufficiently dense sampling of the velocity field for the local normalized angular momentum (LNAM) calculation and the identification of eddy centers. The nearshore eddies identified in Section 3.1 have radii around 30 km and represent vortices in the earliest stages of formation, immediately downstream of the concavities where the MCC separates from the shoreline. As these eddies evolve and propagate offshore they typically grow to radii of 40–50 km, scales that are better resolved by the refined altimetric fields and therefore more robustly captured by AMEDA. The statistics presented here thus characterize the initial stage of eddy formation; subsequent growth and propagation are addressed below. Methodologically, we acknowledge that the 1/4 resolution of the AVISO dataset limits the representation of structures smaller than several grid cells, even though AMEDA uses bicubic interpolation to smooth the field and calculate gradients. Therefore, eddies with radii close to 30 km are at the threshold of detectability with this information, a fact we keep in mind when contextualizing our results. In addition to locating eddies, AMEDA can track their displacement over time, providing estimates of lifetime and propagation speed. We applied AMEDA to the daily geostrophic velocity anomalies after isolating the coastal current (Section 3.1) and retained only those eddies with lifetimes exceeding several days to ensure that well developed structures were analyzed.

2.3. Numerical Model

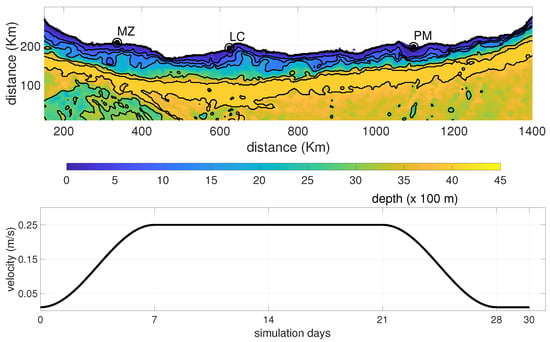

To explore the dynamics of eddy generation, we conducted idealized simulations with the Princeton Ocean Model (POM) [17]. POM solves the three-dimensional hydrostatic, Boussinesq primitive equations on an Arakawa-C grid using finite differences. Vertical mixing is parameterized with the second-order Mellor–Yamada turbulence closure, and the model employs sigma (terrain-following) coordinates to provide enhanced resolution of the surface and bottom boundary layer. The free surface is explicitly represented, and barotropic and baroclinic modes are split to improve computational efficiency. The horizontal domain matches the region shown in Figure 1b, extending 1400 km along the coast and 200 km in direction normal to the coast and encompassing the three concave sections of the coastline where eddies form. The grid comprises 701 × 126 nodes with a uniform spacing of approximately 2.2 km, sufficient to resolve the 30 km eddies identified in the observations. Forty-one sigma layers are employed in the vertical, with uniform spacing from the surface to the bottom to better represent the homogeneous coastal current without significant variations in the vertical. Bathymetry is interpolated from the 1 arc-minute ETOPO-1 global relief model [18] onto the model grid (Figure 2 top), and coastline and shelf features are smoothed to minimize pressure-gradient errors. Lateral boundaries normal to the coast are open and we prescribe the alongshore velocity forcing described below. The top boundary is close by the land and south boundary is open with free radiation condition. The model is initialized from rest, with velocity and a flat free surface equal to zero. A horizontally homogeneous density field is imposed, and no background stratification or wind forcing is applied; thus, the simulated flow is driven solely by the imposed boundary current. At the open eastern and western boundaries we specify a depth-independent alongshore velocity that represents the coastal jet. The velocity of coastal jet (show in Figure 2 bottom) is ramped gradually from 0.01 m to 0.25 m over seven days, maintained at 0.25 m for 14 days and then reduced back to 0.01 m over seven days, for a total simulation time of 30 days. A negative sign in this ramp corresponds to a poleward current, whereas a positive sign corresponds to an equatorward current. At the lateral boundaries radiation conditions allow disturbances to exit the domain. Bottom friction is parameterized using a quadratic drag law with a coefficient of . We analyze the depth-averaged barotropic velocities (, ) and surface velocity fields at daily intervals to examine how the imposed current interacts with the coastline.

Figure 2.

(top) Numerical model domain and (bottom) coastal current velocity modulation.

The model domain and boundary conditions were carefully defined to encompass only the region where the current originates and evolves, ensuring that the simulation focuses exclusively on the dynamical processes responsible for its formation. This targeted configuration isolates the phenomenon, minimizes the influence of remote forcings, and allows the modeled circulation to clearly reflect the local interactions that govern its development.

3. Results

3.1. Mexican Coastal Current Structure

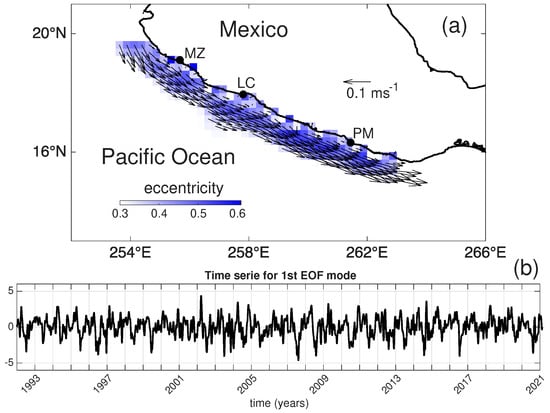

To identify the spatial imprint of the MCC within the geostrophic velocity anomalies, we first computed current-variance ellipses following [19]. For each grid node we formed velocity anomaly time series and , where and are the daily geostrophic velocities and , are their temporal means. Using the RPSstuff routines we determined the lengths of the major () and minor () axes of the variance ellipse at each node. The ellipse eccentricity provides a measure of how well-aligned the velocity fluctuations are: values near zero indicate isotropic variability, whereas large values indicate a preferred direction. We selected nodes with whose semi-major axis is oriented parallel to the coastline; these nodes lie mainly within 20° N and west of 263° E and define the region where the coastal current develops (Figure 3a). Offshore nodes have , reflecting the more isotropic variability of the open ocean. The spatial distribution of eccentricity thus provides a robust way to isolate the coastal current. To examine the temporal variability and spatial structure of the current, we performed an empirical orthogonal function (EOF) analysis on the selected nodes. The first EOF mode explains 33.7% of the total variance and represents a well-defined current flowing parallel to the coast. This percentage is larger than the 22% reported by [9] for a numerical model that analyzed the entire domain. The spatial pattern of the first mode shows a coastal jet 84–107 km wide, and the temporal amplitude exhibits a semiannually reversal with poleward and equatorward flow (Figure 3b). For the equatorward phase the alongshore current has a mean speed of approximately 0.13 m and reaches up to 0.27 m . In the poleward phase the mean speed is ∼0.16 m with maxima up to 0.33 m . These values confirm the strength and narrow width of the MCC and highlight its semiannually cycle.

Figure 3.

Representation of the first EOF mode as (a) map of the vector field (spatial mode) and (b) time series (temporal mode). The blue tones nodes correspond to velocity time series with > 0.3.

3.2. Generation of Near-Shore Eddies

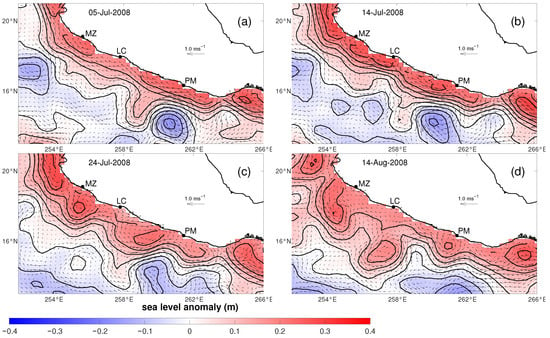

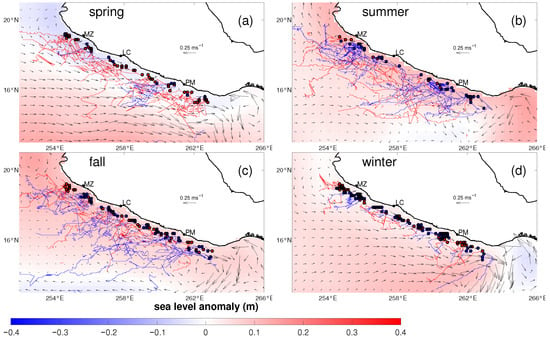

During the processing and visual inspection of the daily geostrophic velocity fields, we noted the appearance of numerous small eddies that resemble current instabilities, similar to those reported by [20,21]. A closer examination shows that these eddies consistently form between the coastal jet and the shoreline at three specific locations in the SMP: off Manzanillo (MZ), off Lázaro Cárdenas (LC) and off Punta Maldonado (PM). This generation process differs from those described by the earlier studies, which focused on larger instabilities farther offshore; here the eddies originate within coastal concavities. Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of the current and eddies during July–August 2008 as an example. On 5 July the poleward phase of the coastal current is well developed (Figure 4a). By 14 July anticyclonic recirculations begin to form at MZ, LC and PM (Figure 4b). Ten days later, at 24 July (Figure 4c) a well-defined anticyclonic eddy has developed off MZ and a weaker eddy off PM. By 14 August (Figure 4d) the MZ eddy has moved offshore and the PM eddy has intensified. A larger eddy centred near 257° W, 15.5° N appears to have originated from LC. Similar sequences occur during other years and during both phases of the current, indicating that near-shore eddy formation is a recurrent feature.

Figure 4.

Geostrophic velocity (in m ) derived from SSHA (blue/red tones) for some days in July and August of 2008, showing the current flow close to the coast (panel a,b) and the evolution of the recirculation as the current begins to weaken taking off from the coast and allowing the eddies to move freely (panel c,d).

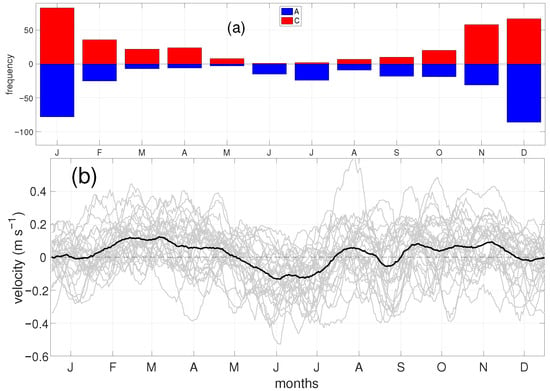

To quantify these observations we applied AMEDA to the entire 1993–2021 dataset and extracted all eddies originating near the three sites. Eddies were classified by their sense of rotation; anticyclonic (clockwise) eddies are plotted in blue and cyclonic (counter-clockwise) eddies in red in Figure 5, which shows their initial positions and tracks. Both types of eddies propagate predominantly southwestward, away from the coast, and their genesis locations cluster at the three aforementioned zones. The seasonal distribution of eddy occurrence (Figure 6a) reveals that anticyclonic eddies are most common in June–July, coincident with the poleward phase of the coastal current, whereas cyclonic eddies are most frequent in March–April during the equatorward phase. In the remaining months (January–February and August–December) the numbers of cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies are comparable. This semiannually pattern is consistent with the along-coast velocity time series (Figure 6b): positive velocities (poleward) coincide with the peak in anticyclonic eddies and negative velocities (equatorward) coincide with the peak in cyclonic eddies.

Figure 5.

Seasonal initial points and paths for spring (a), summer (b), fall (c) and winter (d) of identify coastal eddies generated in the Southwest Mexican Coast (red/blue are for cyclonic/anticyclonic). The color map and vectors correspond to temporal mean of SSHA and geostrophic velocity, respectively from 1993 to 2021 derived from CMEMS data.

Figure 6.

(a) Monthly climatology from 1993 to 2021 of emerged cyclon/anticyclon eddies in red/blue. (b) Annual time series of component velocity along the coast for each year (gray) and daily climatology from 1993 to 2021.

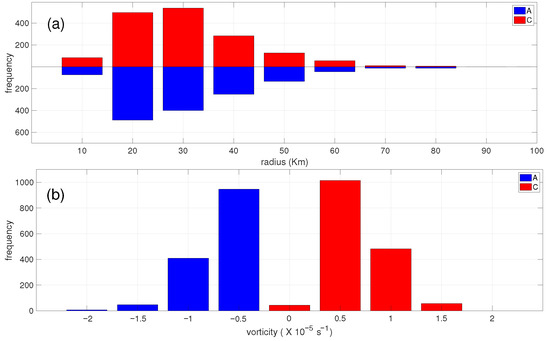

Two key properties characterize these near-shore eddies: their radius and their relative vorticity. Figure 7a shows the histogram of eddy radii, with red bars for cyclones and blue bars for anticyclones. During the generation process, most eddies have radii around 30 km, with a smaller number of eddies having radii of 20 or 40 km. Figure 7b displays the corresponding histogram of relative vorticity; cyclonic eddies exhibit positive vorticities and anticyclonic eddies negative vorticities, with modal values near and some stronger eddies reaching . The narrow distributions indicate that the eddies are generated under fairly uniform dynamical conditions. We therefore conclude that the MCC interacts with the coastline to produce submesoscale eddies with a typical radius of ∼30 km and a typical relative vorticity magnitude of , and that the sign of vorticity depends on the direction of the coastal current.

Figure 7.

Histogram of vortex radio (a) and relative vorticity (b). In both, red/blue are for cyclonic/anticyclonic ocean eddies.

3.3. Modeled Eddy Formation

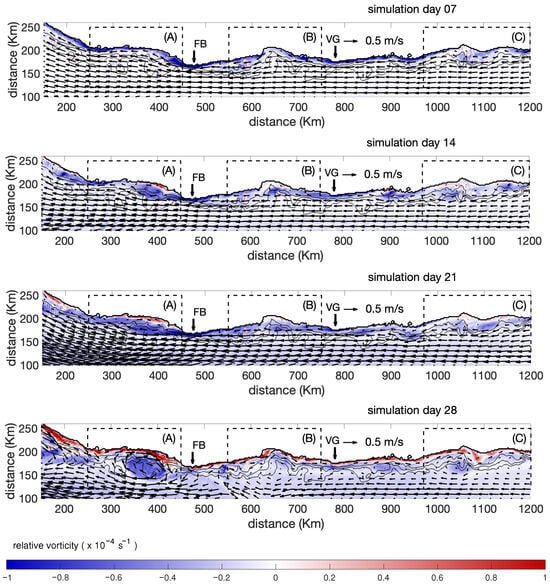

The POM simulations demonstrate that the imposed coastal current undergoes systematic separation from the coastline as it intensifies, particularly at the three major concave headlands of the region. Figure 8 and Figure 9 show the velocity (black arrows) and vorticity (colored tones) maps for the two simulations. Each figure displays four panels for simulation days 7, 14, 21, and 28, from top to bottom. Within each panel, the concave zones for MZ (A), LC (B), and PM (C) are delimited by rectangles with dashed lines. Also included in each panel are headland markers or points called Faro de Bucerías (FB) and Puerto Vicente Guerrero (VG). During the phase of maximum alongshore velocity, the current detaches approximately 36 km offshore at MZ, LC, and PM, creating a dynamically favorable zone in which recirculation can initiate. This behavior is consistent with theoretical and numerical studies demonstrating that rotating coastal flows tend to overshoot concave or corner-like geometries, leading to the formation of recirculation zones in the lee of the separation point [22,23,24].

Figure 8.

Surface current (arrows) and relative vorticity (color tone) maps from the numerical model for poleward current case for simulation days 7, 14, 21 and 28 from the top panel to the bottom panel, respectively. The rectangles (dashed box) indicate the places where the coast has concavity and the vertical arrows FB and VG, the points or capes on the coast.

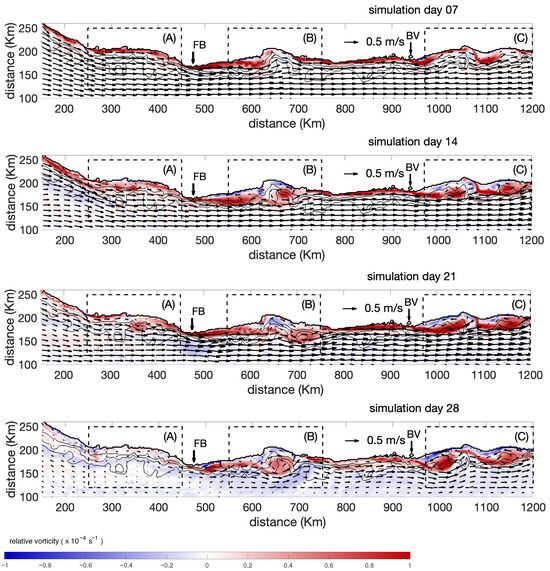

Figure 9.

Surface current (arrows) and relative vorticity (color tone) maps from the numerical model for equatorward current case for simulation days 7, 14, 21 and 28 from the top panel to the bottom panel, respectively. The rectangles (dashed line) indicate the places where the coast has concavity and the vertical arrows FB and VG, the points or capes on the coast.

In the poleward run (Figure 8), anticyclonic recirculations become evident since simulation day 7 and 14, coincident with the period of strongest forcing, and subsequently intensify as the imposed current begins to weaken. By simulation day 21 and 28, these structures have grown into well-developed anticyclonic eddies with radii between 44 km and 53 km, and some exhibit partial detachment from the coast (Figure 8). A similar evolution occurs in the equatorward run: cyclonic recirculations at LC (B dashed box) and PM (C dashed box) appear during the high-velocity phase, even though no eddy forms at MZ (A dashed box) during active forcing. As in the poleward case, the weakening of the imposed current allows these cyclonic recirculations to strengthen and expand, achieving comparable eddy radii by simulation day 28 (Figure 9). The persistence and growth of the eddies despite the reduction in current speed underscores their dynamical robustness and the key role of coastline geometry in sustaining them.

Together, these results show that the coastal current (regardless of its direction) consistently separates from the coastline at concave sections, leaving a gap that serves as the seed region for recirculation and eddy formation. The subsequent weakening of the current provides favorable conditions for vortex amplification, enabling the eddies to reach larger radii. The differences between the poleward and equatorward configurations highlight the sensitivity of the system to the sign of vorticity input, yet the overall mechanism remains the same: topographic concavities induce flow separation, trigger recirculation, and ultimately give rise to mature mesoscale eddies. This coherent and reproducible behavior across model configurations confirms that coastline geometry and the temporal evolution of the alongshore current jointly control the location, polarity, and size of the eddies generated in this system.

The mechanism described by Klinger’s studies provides a robust theoretical framework for interpreting the eddy formation observed in our simulations. In rotating coastal flows, a sufficiently strong boundary current is unable to remain attached to sharp concavities or corner-like features of the coastline, leading to flow separation and the creation of a region of weak relative vorticity downstream of the separation point, as demonstrated in [22,23,24]. As the current overshoots the concavity, conservation of potential vorticity drives the development of a recirculation cell within the sheltered region behind the separation. Klinger’s barotropic and baroclinic experiments [22,23,24] show that these recirculations can intensify and evolve into coherent mesoscale eddies as the flow adjusts to the geometric constraint imposed by the coastline. This mechanism—flow overshoot, separation at concave headlands, and subsequent vortex spin-up—matches closely the evolution seen in our simulations, where the imposed current first detaches from the coastline, then generates recirculation zones that ultimately develop into persistent mesoscale eddies.

4. Discussion

This study provides a detailed characterization of the MCC and its interaction with the coast–lines using nearly three decades of satellite altimetry supplemented by idealized numerical simulations. The variance-ellipse and EOF analyses isolate a narrow, semiannually reversing jet ~90–100 km wide with speeds up to m , corroborating earlier in situ measurements, [8] and model results, [9]. Eddy detection reveals that small radius (30 km) cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies consistently form at three concave sections of the coastline; off MZ, LC and PM. Anticyclonic eddies dominate during the poleward phase of the MCC, whereas cyclonic eddies dominate during the equatorward phase. Numerical simulations reproduce this behavior and show that eddies emerge when the coastal current intensifies and detach away from the coast when the coastal current weakens and separates from the coast. These findings differ from [20] demonstrating that near-shore eddies originate within the coastal boundary layer rather than as offshore current instabilities and by identifying specific generation sites. The present study confirms that altimeter-derived sea level anomalies capture the Mexican Coastal Current and its associated eddies with remarkable fidelity, despite the challenges of observing energetic flows near complex coastlines. This finding echoes the conclusions of [11], who argued that satellite sensors provide unparalleled spatial coverage for monitoring coastal circulation and serve as a vital complement to in-situ observations. However, [11] also notes that the finite resolution of remote-sensing products can limit the detection of submesoscale features; our analysis suggests that some smaller eddies may indeed be under-resolved, highlighting the need for higher-resolution observations and targeted field campaigns. The generation of coastal eddies can be understood in the framework of boundary-layer separation and vorticity conservation [22,23,24]. As the MCC flows along the irregular coastline, it encounters broad concavities where the shoreline abruptly bends inland. The adverse pressure gradient across these concavities causes the alongshore boundary layer to separate, creating a recirculation cell. Conservation of potential vorticity dictates that a poleward (northward) boundary current imparts negative relative vorticity to the water parcel (anticyclonic rotation), whereas an equatorward (southward) current imparts positive vorticity (cyclonic rotation). The typical eddy radius of 30 km is close to the first baroclinic Rossby radius of deformation for the region (20–40 km), suggesting that the separation and subsequent roll-up are facilitated by baroclinic instability. Once formed, the eddies detach from the coast as the background current weakens, and the -effect induces a southwestward drift. The numerical experiments confirm that the direction and amplitude of the imposed current control both the sense of rotation and location of eddies generated: anticyclones form at all three sites when the current is poleward, but cyclones form only at LC and PM when the current is equatorward. The absence of cyclones at MZ in the model may reflect differences in coastline curvature or bathymetry at that site, highlighting the importance of local geometry.

The semiannual reversal of the MCC aligns with the annual cycle of the NECC and the CRCC, linking our regional observations to the larger-scale Pacific circulation. In boreal summer the NECC intensifies and flows eastward toward Central America; its northern branch turns poleward along the Mexican coast, manifesting as the MCC’s poleward phase. In spring and autumn the NECC weakens and the CRCC strengthens, transporting cooler, saltier water equatorward along Central America; the MCC’s equatorward phase likely represents the northern return flow of this system. The correlation between the MCC’s semiannual cycle and the occurrence of cyclonic and anticyclonic eddies thus reflects the influence of remote equatorial forcingm [10,25]. Additionally, episodic wind jets (Tehuano, Papagayo) and coastally trapped Kelvin waves generated by equatorial wind pulses may modulate the strength of the MCC, altering the frequency and intensity of eddy generation. Incorporating realistic wind and buoyancy forcing in future models will help assess these effects. This shows the relevance of mesoscale variability in the study region, as analyzed by [26] on the circulation at the entrance to the Gulf of California using altimetry and hydrographic data, which concludes that mesoscale activity (i.e., the presence of eddies and meanders) contributes 33% of the total variance of the surface circulation, a value comparable to the variability found in our results. Eddy shedding from boundary currents is a common phenomenon worldwide. The Brazil Current forms warm rings when it separates from Cabo Frío; the Ierapetra eddies spin off the Mid-Mediterranean Jet; and the North Brazil Current produces energetic rings that propagate into the Caribbean. In each case, flow separation at sharp coastline bends or bathymetric features triggers recirculation and eddy formation. The MCC eddies are smaller in scale and shorter-lived than those rings but share the same dynamical underpinnings. The consistent radius and vorticity we observe imply that the coastal geometry and regional stratification set the eddy scale. These eddies may enhance cross-shelf exchanges, impacting nutrient transport, larval dispersion and fisheries along the SMP; however, in situ studies are needed to assess their biological significance [27]. While our analysis integrates long altimeter records and numerical experiments, several limitations remain. The 0.25° resolution of the satellite product is marginal for resolving 20–40 km eddies; smaller features may be missed or mischaracterized. The AMEDA algorithm assumes isolated, axisymmetric vortices and may struggle in regions with multiple interacting eddies. Our numerical model imposes a simplified, depth-independent current and neglects wind, stratification and tidal forcing; consequently, it reproduces the qualitative mechanism but not the full variability. Incorporating realistic wind stress, buoyancy fluxes and background stratification in future simulations will help quantify the relative roles of barotropic versus baroclinic instabilities and assess the impact of episodic wind events. High-resolution in situ observations, such as gliders or moored current meters, would also allow validation of the satellite-derived velocities and provide vertical structure information.

5. Conclusions

We used SSALTO/Duacs altimetric data from CMEMS (1993–2021) to identify the coastal current in the southwestern Mexican Pacific and its interaction with the coastline. Variability ellipses and EOF analysis confirmed the current with characteristics consistent with previous observations and models. The current interacts with the coastline and generates eddies in three regions: Manzanillo (MZ), Lázaro Cárdenas (LC), and Punta Maldonado (PM). These eddies, typically ∼30 km in radius with relative vorticity up to , are anticyclonic when the current is poleward and cyclonic when equatorward. They last a few weeks as they move offshore. A simple POM model simulation confirmed that eddy generation depends on current direction and coastal geometry. Poleward currents generate eddies in MZ and PM, while equatorward currents do so in LC and PM. The model also showed that coastal capes enhance vorticity, which is advected into concavity zones where eddies form. Other processes, such as current instabilities also produce eddies, making it difficult to separate their origin with altimetry data alone. Nonetheless, these coastal eddies play an important role in biological and chemical processes, as shown for the California Current. For the Mexican Coastal Current, detailed studies remain scarce with respect to the local effects of the coastal currents, being focus on studying the temporal variability and the connection with the tropical Pacific. Further research combining high-resolution models and direct observations is needed to better understand the generation and evolution of these eddies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.A.V.-M. and R.C.C.-G.; methodology, F.A.V.-M.; software, F.A.V.-M.; validation, F.A.V.-M., R.C.C.-G. and C.M.; formal analysis, F.A.V.-M.; investigation, F.A.V.-M.; resources, C.M.; data curation, C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.V.-M., R.C.C.-G. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, F.A.V.-M., R.C.C.-G. and C.M.; visualization, F.A.V.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The Mean Sea Level Anomaly (msla) and the Absolute Geostrophic Current (, ) were obtained from the DUACS delayed-time altimeter gridded maps of sea surface heights and derived variables over the global (https://doi.org/10.48670/moi-00145, accessed on 31 January 2024.) produced and distributed by the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S, https://climate.copernicus.eu/, last accessed: 31 January 2024). Bathymetry data were obtained from the ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model. Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis. NOAA Technical Memorandum NESDIS NGDC-24. National Geophysical Data Center, NOAA. doi:10.7289/V5C8276M (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ngdc.mgg.dem:316, accessed on 20 October 2022).

Acknowledgments

We thank Reginaldo Durazo and Antonio Martínez for his valuable comments on the manuscript. The authors express their sincere appreciation to the one anonymous review and X Carton review for their thorough evaluations and constructive comments, which significantly improved the clarity, rigor, and overall quality of this manuscript. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the Universidad de Guadalajara through the Centro Universitario de Ciencias Exactas e Ingenierías (CUCEI). This support was essential for the development of the computational analyses, data acquisition, and research activities that contributed to the completion of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gan, J.; Allen, J.S. Modeling upwelling circulation off the Oregon coast. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2005, 110, C10S07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyer, A. Coastal upwelling in the California current system. Prog. Oceanogr. 1983, 12, 259–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stabeno, P.J.; Bond, N.A.; Hermann, A.J.; Kachel, N.B.; Mordy, C.W.; Overland, J.E. Meteorology and oceanography of the Northern Gulf of Alaska. Cont. Shelf Res. 2004, 24, 859–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brink, K.H.; Halpern, D.; Huyer, A.; Smith, R.L. The physical environment of the Peruvian upwelling system. Prog. Oceanogr. 1983, 12, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badan-Dangon, A. Coastal Circulation from the Galapagos to the Gulf of California, The Sea. Glob. Coast. Ocean. Reg. Stud. Synth. 1998, 11, 315–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler, W.S. The circulation of the eastern tropical Pacific: A review. Prog. Oceanogr. 2006, 69, 181–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyrtki, K. Surface currents of the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Bull.-Inter-Am. Trop. Tuna Comm. 1965, 9, 269–304. [Google Scholar]

- Lavín, M.F.; Beier, E.; Gómez-Valdés, J.; Godínez, V.M.; García, J. On the summer poleward coastal current off SW México. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Valdivia, F.; Parés-Sierra, A.; Flores-Morales, A. The Mexican Coastal Current: A subsurface seasonal bridge that connects the tropical and subtropical Northeastern Pacific. Cont. Shelf Res. 2015, 110, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terrazas-Silva, M.A.; de León, D.A.S.; Castillo, M.L.M.; Gómez, M.A.M. The connection of the Costa Rica Coastal Current with the West Mexican Current in the Gulf of Tehuantepec. Cont. Shelf Res. 2024, 279, 105294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klemas, V. Remote Sensing of Coastal and Ocean Currents: An Overview. J. Coast. Res. 2012, 28, 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- CMEMS. Global Ocean Gridded L4 Sea Surface Heights And Derived Variables Reprocessed Copernicus Climate Service, Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) [Data Set]. 2023. Available online: http://marine.copernicus.eu (accessed on 31 January 2024).

- Pujol, M.-I.; Faugère, Y.; Taburet, G.; Dupuy, S.; Pelloquin, C.; Ablain, M.; Picot, N. DUACS DT2014: The new multi-mission altimeter data set reprocessed over 20 years. Ocean. Sci. 2016, 12, 1067–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Vu, B.; Stegner, A.; Arsouze, T. Angular Momentum Eddy Detection and Tracking Algorithm (AMEDA) and Its Application to Coastal Eddy Formation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2018, 35, 739–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroucha, L.C.; Veleda, D.; Lopes, F.S.; Tyaquiçã, P.; Lefèvre, N.; Araujo, M. Intra- and Inter-Annual Variability of North Brazil Current Rings Using Angular Momentum Eddy Detection and Tracking Algorithm: Observations From 1993 to 2016. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2020, 125, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Stegner, A.; Le Vu, B.; Taupier-Letage, I.; Speich, S. Dynamical Evolution of Intense Ierapetra Eddies on a 22 Year Long Period. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 9276–9298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumberg, A.F.; Mellor, G.L. A Description of a Three-Dimensional Coastal Ocean Circulation Model. In Three-Dimensional Coastal Ocean Models. American Geophysical Union (AGU); American Geophysical Union: Washington, DC, USA, 1987; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Amante, C.; Eakins, B.W. ETOPO1 1 Arc-Minute Global Relief Model: Procedures, Data Sources and Analysis. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/metadata/landing-page/bin/iso?id=gov.noaa.ngdc.mgg.dem:316 (accessed on 20 October 2022).

- Signell, R. Miscellaneous Tools from (Mostly) Version 1.2. 2000. Available online: https://github.com/rsignell-usgs/RPSstuff (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Zamudio, L.; Leonardi, A.P.; Meyers, S.D.; O’Brien, J.J. ENSO and eddies on the southwest coast of Mexico. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2001, 28, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Gómez, R.C.; Sansón, L.Z.; Velazquez-Muñoz, F.A. Laboratory experiments on coastal current separation and vortex formation in front of Cabo Corrientes and Bahía de Banderas, México. Cont. Shelf Res. 2023, 262, 105022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, B.A. Gyre formation at a corner by rotating barotropic coastal flows along a slope. Dyn. Atmos. Ocean. 1993, 19, 27–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, B.A. Baroclinic eddy generation at a sharp corner in a rotating system. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 1994, 99, 12515–12531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, B.A. Inviscid current separation from rounded capes. J. Phys. Oceanogr. 1994, 24, 1805–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Hernández, C.; Ahumada-Sempoal, M.Á.; Durazo, R. The Costa Rica Coastal Current, eddies and wind forcing in the Gulf of Tehuantepec, Southern Mexican Pacific. Cont. Shelf Res. 2016, 114, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez, V.M.; Beier, E.; Lavín, M.F.; Kurczyn, J.A. Circulation at the entrance of the Gulf of California from satellite altimeter and hydrographic observations. J. Geophys. Res. 2010, 115, C04007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurian, J.; Colas, F.; Capet, X.; McWilliams, J.C.; Chelton, D.B. Eddy properties in the California Current System. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, C08027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.