Abstract

Changes in climate and ocean pollution has prioritized monitoring of ocean surface behavior. Ocean drifters, which are floating sensors that record position and velocity, help track ocean dynamics. However, environmental events such as oil spills can cause abnormal behavior, making anomaly detection critical. Unsupervised learning, combined with deep learning and advanced data handling, is used to detect unusual behavior more accurately on the NOAA Global Drifter Program dataset, focusing on regions of the West Coast and the Mexican Gulf, for time periods spanning 2010 and 2024. Using Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN), pseudo-labels of anomalies are generated to train both a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network. The results of the two models are then compared with bootstrapping with block shuffling, as well as 10 trials with bar chart summaries. The results show nuance, with models outperforming the other in different contexts. Between the four spatiotemporal domains, a difference in the increasing rate of anomalies is found, showing the relevance of the suggested pipeline. Beyond detection, data reliability and efficiency are addressed: a RAID-inspired recovery method reconstructs missing data, while delta encoding and gzip compression cut storage and transmission costs. This framework enhances anomaly detection, ensures reliable recovery, and reduces energy consumption, thereby providing a sustainable system for timely environmental monitoring.

1. Introduction

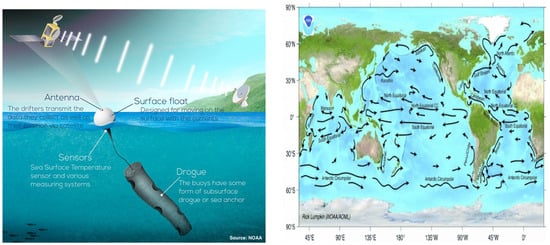

The global ocean plays a vital role in regulating climate, transferring heat, and maintaining biodiversity [1,2]. Given the serious threats to marine ecosystems from large-scale disasters such as climate change, pollution, and oil spills, the importance of dynamic sea level monitoring is becoming increasingly apparent. Understanding abnormal changes in typical ocean circulation patterns is particularly critical for identifying extreme environmental events, ensuring data reliability, and enabling timely scientific and policy responses [3,4]. Ocean buoys are floating devices equipped with sensors that provide variable data, such as location and speed, as they drift with upper ocean currents. This is shown in Figure 1. These devices are essential sources of information for understanding flow patterns and verifying ocean models [2]. They form the basis for research on climate change, pollutant transport, and the dynamics of marine ecosystems.However, sudden environmental events such as hurricanes or communication failures, along with rare events such as oil spills, can disable ocean buoys. Such failures lead to abnormal behavior in the recorded tracks, necessitating robust anomaly detection techniques. Their purpose is not only to filter out corrupted data, but also to identify the valid environmental signals embedded in these deviations. Anomalies associated with this mission refer to deviations where buoys stray from their expected paths. An example of such an anomaly is shown in Figure 2. The yellow buoy, which does not follow a straight line, moves with the current and is not aligned with other buoys exhibiting normal behavior, thus qualifying as an anomaly. Anomalies may manifest as abrupt changes in velocity or direction due to sensor failure, irregular trajectories caused by transmission errors, or unusual ocean current patterns (potentially reflecting environmental events like hurricanes or oil spills) [3]. Distinguishing these cases is critical. Misclassifying environment-related anomalies as “noise” may lead to missing early signs of large-scale disturbances.

Figure 1.

(Left): Components and function of a Global Drifter Program buoy, (Right): Major surface ocean currents across the globe.

Figure 2.

An example of an anomaly.

Anomalies are particularly challenging to detect in ocean drifter data for three reasons:

- Since ocean currents vary depending on the region and season, it is difficult to define a “normal” course. A trajectory that seems unusual in a given region or season may be normal in another region or time period [5,6,7].

- Anomalies in nature are rare and varied. Most trajectories exhibit a typical pattern of ocean currents, with anomalous events occurring rarely. Therefore, identifying anomalies in buoy data are not a trivial task and a highly imbalanced problem [6,8,9].

- The dataset of ocean drifter data does not have a ground-truth label on whether a given data point is anomalous, meaning that analysis of it requires unsupervised machine learning, making it more complex than if it were labeled. At the same time, large-scale monitoring faces practical problems. Data gaps can occur due to sensor failures, and the transmission of huge amounts of raw GPS data consumes significant amounts of energy and storage resources [10].

To address these challenges, accurate anomaly detection methods and effective data recovery and compression strategies are needed. Although previous studies have examined anomaly detection in maritime databases and trajectory data, most studies have focused on labeled vessel tracking data or have not explicitly addressed issues of data resilience and effectiveness in long-term maritime monitoring. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an integrated framework that works without manual labels, ensuring resilience in conditions of data loss and transmission limitations.

In this work, a resilient ML (machine learning)-based pipeline is proposed to combine unsupervised learning [11,12,13,14], deep learning [15,16,17,18], clustering [19,20,21,22,23], and data-efficient recovery methods for anomaly detection in ocean drifters. First, the Density-Based Spatial Clustering of Applications with Noise (DBSCAN) algorithm [24,25,26] is used to generate pseudo-labels of anomalous behavior on a per-drifter basis. These labels are then used to train two neural architectures, a one-dimensional Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, for the classification of normal versus anomalous trajectories [27,28,29,30,31].

Statistical tests with bootstrapping [32] are applied, with the average of 10 runs reported to provide a complementary view of model performance. To address data loss and transmission efficiency issues, this paper proposes a RAID-based recovery system that reconstructs corrupted trajectory segments via Reed–Solomon encoding. Gzip-compressed delta encoding is also employed to reduce storage requirements. Finally, by comparing historical data from the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill incident in the Gulf of Mexico [3] with data from other time periods and regions, the proposed architecture demonstrates its capability to capture significant environmental anomalies.

This paper makes three main contributions:

- An unsupervised-to-supervised pipeline is developed for anomaly detection in ocean drifters by combining DBSCAN clustering with deep learning models, allowing for effective detection without manual labels.

- Data resilience and efficiency are introduced into the monitoring process through simulating a RAID-inspired recovery for missing data and applying compression techniques to reduce storage and transmission costs.

- The framework is validated through statistical testing and real-world datasets, showing both the need for context when considering which model to use for anomaly detection within the oceans, and the system’s relevance in capturing anomalies linked to significant environmental events.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 discusses some of the recent work in this area. Section 3 presents the overall methodology, including DBSCAN pseudo-labeling, sliding window generation, neural network architectures, and recovery/compression strategies. Section 4 reports the experimental results, statistical testing, and hyperparameter tuning. Finally, Section 5 discusses the findings, limitations, and future directions.

2. Related Work

Detecting anomalies in environmental sensor networks requires methods capable of handling unlabeled data, large-scale class imbalances, and spatiotemporal dependencies [24,33,34]. In the ocean, additional constraints, such as data gaps, energy-constrained transmission, and changes in device behavior, require new solutions that combine detection, reconstruction, and compression functions.

2.1. Density-Based and Trajectory Clustering

Density-based clustering is frequently used for spatial outlier detection, as it carries no strong assumptions regarding cluster shape or quantity. This approach can explicitly identify noisy points as outliers. DBSCAN serves as a standard example for such methods and is widely applied in spatial outlier detection [24]. Subsequent iterations, such as HDBSCAN (Hierarchical DBSCAN), enhance performance on complex data distributions by incorporating hierarchical density models and automated density threshold selection mechanisms [25,26]. These properties make density-based clustering methods an ideal choice for per-drifter pseudo-labeling of all data points. Drift paths often exhibit irregular noise, forming dense and irregular structures, further validating this choice. However, density-based methods cannot capture temporal structures themselves. Therefore, density-based DBSCAN is first employed to generate initial results for pseudo labels, followed by optimization using temporal models (see Section 3).

2.2. Deep Learning for Sequential Anomaly Detection

Neural network models are widely used to identify outliers in current time series sensor data. For example, LSTM encoder–decoder models achieve strong resilience and anomaly scores across multiple sensors [31]. Variants of this model, such as approaches using dynamic thresholds, demonstrate robust performance even in highly imbalanced telemetry environments [28]. Other methods, such as single-class deep learning, focus on learning concise representations of normal behavior. This means that anomalies are highlighted as outliers [34]. Recent studies on deep time-series anomaly detection describe approaches for prediction, recovery, and representation. These surveys also reveal specific trade-offs for drifter data, such as data imbalance, label scarcity, and temporal correlations [27,35]. Furthermore, convolutional neural networks demonstrate exceptional capability in capturing short-term temporal patterns, which provides the rationale for comparing one-dimensional convolutional neural networks and LSTMs in Section 3.

2.3. Anomaly Detection in Oceanographic and Climate Data

Machine learning methods for detecting climate anomalies primarily focus on gridded fields, such as sea surface temperature or vertical profile data, utilizing techniques like oversampling, autoencoders, and deep learning to detect and forecast events [33,36,37,38,39,40].

These studies demonstrate that deep learning models can successfully identify large-scale phenomena such as marine heatwaves and ENSO anomalies [36,37]. Simultaneously, research findings suggest that imbalance-aware training can further enhance performance [33], while these studies demonstrate the potential of deep learning in detecting environmental anomalies, the trajectories of drifting buoys exhibit fundamental differences. Buoy trajectories show sparse Lagrangian path characteristics formed by local currents rather than structured grids. Therefore, an effective approach must use spatial clustering techniques to detect anomalies and employ temporal models to capture trajectory dynamics. This led to the framework proposed in this study.

2.4. Trajectory and Maritime Anomaly Detection

Various methods, including density-based approaches, kernel density estimation, mixture models, and modern sequence models such as transformers, have been used to detect maritime anomalies in Automatic Identification System (AIS) tracks to identify abnormal vessel behavior [6]. This study highlights the need to capture local motion patterns and short-term deviations. This challenge is one that is also in drifter data, despite drifter movement being caused by natural forces rather than intentional navigation. Consequently, maritime track analysis methods provide important methodological guidance for feature extraction and windowing strategies, particularly when applied to drifter trajectories.

2.5. Resilience, Recovery, and Compression

Data monitoring systems must not only have data loss protection capabilities, but also minimize energy consumption during data transfer, while conventional approaches, such as erasure coding and Reed-Solomon coding, can reliably recover block-level losses, recent innovations in storage systems, including sparse-stripe RAID designs, have significantly improved recovery speed and efficiency [41]. Specifically, combining delta encoding with lightweight compression methods, such as the Gorilla algorithm, in the context of time series storage and transfer can lead to a significant reduction in data volume while maintaining retrieval accuracy [42]. These techniques inspired the RAID-based recovery simulation and the delta+Gzip pipeline proposed in this paper (see Section 3), which allows drifter monitoring to be more resilient, energy-efficient, and high-performing in real-world deployment scenarios.

2.6. Neural Networks in Ocean Currents

Recent studies confirm that the role of neural networks in ocean surface dynamics and circulation is gradually expanding, providing valuable insights for identifying anomalies in the trajectories of drifting objects. Methods based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been applied to enhance satellite products, improving the resolution of sea level height and temperature fields while optimizing the accuracy of derived ocean current assessments and mesoscale features [5,43]. These studies demonstrate that convolutional models such as CNNs possess the capability to extract fine spatial patterns from high-noise or coarse input data.

In trajectory prediction, recurrent neural networks such as LSTMs are commonly used for short-term drifting buoy path forecasting. These networks can more effectively capture nonlinear dynamical features in specific scenarios, such as eddy-dominated flow fields, outperforming traditional physics-based tracking methods [44]. Recently, transformer-based models, including SEA-ViT, have demonstrated potential in predicting surface currents using high-frequency radar observations. They achieve this by capturing long-range spatiotemporal dependencies through self-attention mechanisms [10].

Overall, neural operator frameworks, including GLONET [45], are being developed in parallel with global ocean prediction systems that have been trained on physically reconstructed historical ocean data. Compared to numerical models, these frameworks combine high efficiency with accurate prediction capabilities. A hybrid design based on the CNN-Transformer-PINN architecture significantly improves the accuracy and physical consistency of eddies and ocean fronts forecasts by deepening the integration of physically constrained learning [46].

Together, these advances demonstrate the ability of neural networks to understand and represent the multiscale spatiotemporal dynamics of the ocean. This study utilizes CNNs to detect anomalies in local trajectories, comparing them to iterative LSTM models documented in the literature for their superior ability to handle temporal dependencies. These developments provide a solid foundation for the current study.

2.7. Survey of Spatiotemporal Methods in Ocean Science

A recent study titled “Spatio-temporal Data Mining in Marine Science: Data, Methods and Opportunities” [7] provides a comprehensive overview of methodologies for mining ocean data and highlights the specific challenges facing ocean sciences. Four characteristic features stand out: regional heterogeneity, high data sparsity with significant missing values, inherent uncertainty, and strong spatiotemporal dependencies [9,47,48]. These characteristics complicate tasks such as anomaly detection, predictive analysis, and data characterization.

The survey identifies three major methodological directions:

- Data quality improvement remains essential due to severe data gaps. Traditional approaches such as Optimal Interpolation, Kriging, and DINEOF are still widely used [49,50,51], while machine learning techniques like random forests, KNN, and matrix factorization offer additional flexibility [52,53,54]. Recent developments utilize deep learning models, including CNN and LSTM-based approaches, U-Nets, and GANs such as STA-GAN and DINCAE/DINCAE 2.0, for completion and reconstruction [55,56,57,58,59,60], while these models achieve higher accuracy for irregular missing patterns, they incur higher computational costs and suffer from interpretability drawbacks.

- Anomaly detection. This study distinguishes between differences between trajectories, time-series, and satellite image settings. Trajectory analysis often employs density-based clustering (DBSCAN and its improved versions), which can handle irregular shapes and explicitly identifies noise points [6,24]. In sensor time series, LSTM and Encoder–Decoder–RNN [56,59] are dominant, while CNN is particularly suitable for documenting short-range local dynamics [55]. In images, the most common approaches are CNN, VAE, GAN, and RPCA, which are all based on representation learning [58,61]. In all these areas, unsupervised and semi-supervised learning approaches are emphasized, as labeled anomalies are rare, and probabilistic frameworks, such as Gaussian mixture VAE and attention-based sequential models, are gaining popularity [7,9].

- Forecasting and representation learning are increasingly driven by hybrid architectures. ConvLSTM and CNN-Transformer hybrids are used for spatio-temporal prediction [62,63], while physical information neural networks (PINNs) and physically guided GANs improve consistency with dynamic constraints [9,59]. Furthermore, research findings indicate an increasing prevalence of self-supervised learning approaches and large foundation models, such as ClimaX, that aim to leverage the abundant unlabeled data available in the ocean and climate domain [63,64].

Overall, the survey in [7] highlights several trends:

- Deep and hybrid models now dominate over traditional methods

- Evaluation remains a challenge due to scarce benchmarks and heavy class imbalance in anomalies

- There is a clear call for end-to-end, physically grounded, and operationally reliable spatiotemporal frameworks for ocean science.

2.8. How This Work Differs

The recent survey of spatiotemporal methods in ocean science highlights several persistent gaps: the scarcity of labeled anomalies, severe class imbalance, lack of standardized benchmarks, and limited integration of data-quality and anomaly detection pipelines into deployable systems, while earlier works have explored density clustering for trajectory analysis, deep models for temporal anomalies, and various imputation methods for missing data, these approaches are typically studied in isolation. End-to-end frameworks that combine unsupervised clustering, sequential modeling, robust evaluation, and operational resilience are largely absent, particularly for sparse Lagrangian drifter trajectories.

The proposed work makes a contribution to address this gap in four ways:

- Per-drifter DBSCAN pseudo-labeling is employed to generate training targets without requiring manual annotation, aligning with the survey’s emphasis on unsupervised strategies for trajectory anomalies.

- Convolutional and recurrent temporal models, with a 1-D CNN and LSTM, respectively, under a sliding-window framework are compared, reflecting the surveyed distinction between local pattern extraction and long-term dependency modeling.

- Focal-loss training and bootstrap-based evaluation are incorporated, directly targeting the survey’s identified challenges of class imbalance and reproducibility.

- Algorithmic anomaly detection is extended by integrating RAID-style recovery simulations with delta encoding and compression, a systems-level contribution that complements the survey’s focus on data completion and fusion but addresses the often-overlooked problem of resilience and transmission efficiency.

Together, these components form an end-to-end pipeline for drifter trajectory anomaly detection and monitoring that addresses the methodological and operational challenges outlined in the survey, while providing a novel integration not previously seen in the literature.

Novelty Statement

Previous studies have separately provided relevant components such as density clustering for trajectories, temporal anomaly sequence models, and erasure coding for block recovery. However, the innovation of this research lies in explicitly integrating all these components into a single operation-focused pipeline for sparse Lagrangian drift data. Specifically, beyond cumulative fusion, the contributions include: (i) a workflow for adaptive pseudo-DBSCAN labeling of each drifter, generating tailored training targets based on each drifter’s local movement patterns rather than applying a global threshold, (ii) supervised deep learning models trained on these pseudo-labels, quantifying recovery across regions and years through imbalance-aware loss functions and bootstrap-based statistical validation, (iii) system-level integration of RAID-based reconstruction and delta + Gzip compression with anomaly detection to address constraints like energy, transmission, and data loss in real deployments. Existing research on known track anomalies either focuses on labeled AIS vessel behavior or treats recovery/compression and detection as independent problems. This paper combines these approaches and validates the pipeline using National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) drifter data, including the 2010 Deepwater Horizon incident. Therefore, it delivers methodological and operational innovations.

3. Materials and Methods

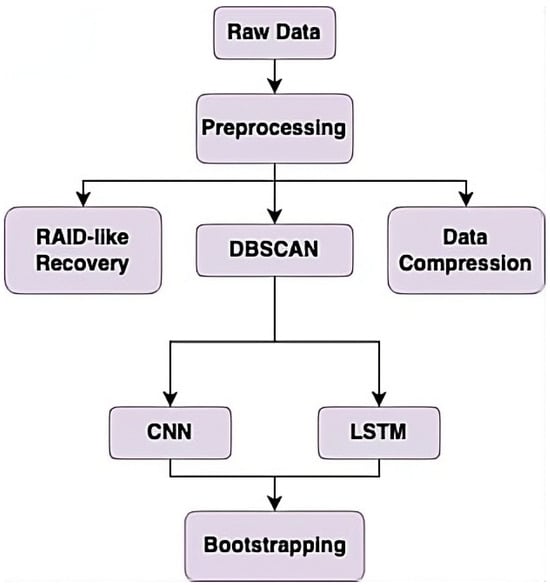

An overall diagram of the proposed methodology can be seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Workflow of the overall methodology.

Data collection and preprocessing are the first step. These cleaned data are fed into DBSCAN for pseudo-labeling. The data, along with its pseudo-labels, is then used to train and test two models: a CNN and an LSTM. The results of the two models are compared using bootstrapping. The preprocessed data are additionally used to simulate a data loss scenario, with RAID to recover it. The data also undergoes compression for sustainability.

3.1. Data Collection and Preprocessing

The drifter trajectory data were obtained from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Environmental Research Division’s Data Access Program (ERDDAP) database, specifically using the 6 h drifter dataset from 2010 and 2024 [65]. The dataset included positional coordinates (latitude and longitude) and velocity components (eastward velocity ve, and northward velocity, vn). To focus on the specific geographical region of the West Coast, only drifters with latitudes between 25° N and 50° N and longitudes between 225° E and 245° E were used. For the specific geographic region of the Mexican Gulf, only drifters with latitudes between 14° N and 32° N and longitudes between 255° E and 300° E. An example of the dataset from NOAA is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample raw drifter data.

The data illustrate positions of a drifter off the West Coast on 24 August 2010 taken every 6 h. In the above dataset, and denote the north and east components of the velocity. The data were then pre-processed with standardization, a common procedure in machine learning and data analysis [12,32]. The features were standardized using StandardScaler to ensure that each feature contributed equally to clustering and modeling. The timestamps were converted to datetime objects, and all numeric columns were explicitly cast to ensure data consistency. An example of a processed table is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample standardized drifter data.

3.2. Anomaly Detection Using DBSCAN

Since the data are unlabeled, clustering is first used to assign pseudo-labels to the dataset. This is performed to enable the neural networks to predict a label of normal or anomalous. The dataset was analyzed on a per-drifter basis. The trajectory of each drifter was treated independently to account for unique movement patterns. The density-based spatial clustering algorithm, DBSCAN, was used because it is well-suited for detecting anomalous or outlying trajectories by allowing for noise without requiring any initial assumptions about the number of clusters.

The DBSCAN parameter “eps” (max distance between two samples to define neighborhoods) was optimized for each drifter using a k-distance graph [66]. A standard Euclidean distance [67,68,69] is used. The KneeLocator algorithm was used to identify the “elbow” point in the sorted k-nearest neighbor distances. Points labeled as “” by DBSCAN were classified as anomalies (negative “−” labels), and the remaining points were classified as positive “+” labels. This per-drifter approach to true label assignment allowed for adaptive thresholding tailored to individual trajectory behaviors.

For the other DBSCAN parameter “min_samples” (minimum number of points within a sample to define a core point), it was set to a value of 3 due to the tendency of DBSCAN to classify the start and end points of a drifter as anomalous. A smaller value of 3 was chosen to combat this issue.

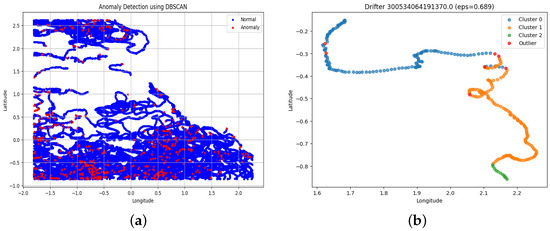

The data, after being separated into normal (“positive”) and anomalous (“negative”) labels, which are blue and red, respectively, can be seen in Figure 4a.

Figure 4.

DBSCAN results. (a) overall dataset with “+” and “−” labels. (b) a single drifter example.

In Figure 4b shows an example of an individual drifter after undergoing DBSCAN, with different points grouped together, with all points other than the red outlier points becoming labeled as normal. In both cases, the data used is the 2024 West Coast data, serving as an example.

In Figure 4a, the trajectories of individual drifters are represented through a series of blue points, forming continuous and connected curves. These lines trace the movement of the drifter over the time period, showing the underlying structure of the data, and they also show that the proposed per-drifter approach is effective. It captures these individual movement patterns rather than mixing up multiple drifters’ behaviors. So, DBSCAN can more accurately identify anomalous points.

3.3. Sliding Window Generation

To prepare sequential data for deep learning, a sliding window approach was applied. The trajectory of each drifter was segmented into overlapping windows of length time steps, with a stride of 1. For each window, if any point was labeled as anomalous by DBSCAN, the entire window was considered anomalous. This process generated sequences X_seq (shape: number of windows × window size × features) and corresponding binary labels Y_seq (anomaly or normal). A window size of was chosen as a balance between short-term dynamics, which are better captured with a smaller window size, and long-term trends, which are better captured with a larger window size. This approach is commonly performed within research where a baseline of 10 for window size is recommended for anomaly detection on software logs [70]. This is also a default value in official MathWorks documentation where a window size of is chosen for time series anomaly detection [71].

The dataset was divided into training and validation sets using a stratified 80/20 split to preserve the proportion of anomalies. Unless otherwise stated, all reported experiments use an 80/20 train-test split, which is standard practice and provides sufficient training data while reserving an independent test set for evaluation [72]. During hyperparameter tuning, an additional 50/50 split was evaluated solely as a robustness check to assess sensitivity to training data availability under extreme data constraints. This balanced split was not used for final model training or performance reporting. To address the class imbalance, anomalies in the training set were oversampled by random resampling to match the number of normal sequences. The validation set remained unaltered to provide a realistic evaluation of model performance.

3.4. Deep Learning Models

Two deep learning architectures were trained for anomaly detection: a 1D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) and a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network with contextual pooling. Both models are based on established approaches for time series anomaly detection, where CNNs capture local temporal patterns, while LSTMs model longer-range dependencies [73,74].

Input trajectories were segmented into fixed-length windows of size 10. This window length was chosen to balance temporal context and data efficiency: it is sufficiently long to capture short-term dynamics and abrupt deviations commonly associated with anomaly events, while remaining short enough to avoid excessive smoothing of localized behaviors and to preserve the number of training samples. Similar window sizes have been adopted in prior anomaly detection studies based on trajectory and sensors, where anomalies manifest over short temporal horizons rather than extended sequences [28,35].

CNN Architecture The CNN processes fixed-length windows of trajectory features using a hierarchical temporal feature extraction strategy. The network consists of:

- Two 1D convolutional layers with 64 and 128 filters, kernel size 3, and same padding, preserving sequence length while capturing local temporal dependencies. Stacking multiple kernel-3 convolutions increases the effective temporal receptive field, enabling the model to capture short-range patterns spanning multiple timesteps without significantly increasing parameter count [75].

- ReLU activations and batch normalization after each convolution to improve training stability and convergence.

- Max pooling (pool size = 2) to reduce temporal resolution and emphasize salient local features, a commonly used design choice in time series CNNs to improve robustness to minor temporal shifts [76].

- A global max pooling layer to aggregate features across the entire window, allowing the network to detect the most discriminative anomaly related patterns regardless of their temporal position within the window.

- A fully connected layer with 64 units, ReLU activation, and dropout (0.5) for regularization.

- A sigmoid output layer for binary classification.

LSTM Architecture: The LSTM processes sequential windows, with sequence length aligned to the fixed input window size to maintain consistent temporal context across models. The network includes:

- A single LSTM layer with 64 units, returning sequences for downstream pooling, allowing the model to encode cumulative temporal dependencies and evolving patterns over the input window [77].

- Global average pooling to produce a fixed-length representation that summarizes temporal behavior across the entire sequence while reducing sensitivity to isolated noise.

- A fully connected layer with 64 units, ReLU activation, and dropout (0.5).

- A sigmoid output layer for binary classification.

Training Regime Both models were trained using the Adam optimizer with a focal loss function [78], where is dynamically set based on the proportion of positive labels in the training split and . Early stopping was applied with a patience of 8 epochs, restoring the best-performing weights. Models were trained with a batch size of 64 and multiple random seeds (0–9) to ensure reproducibility and reduce variance in reported performance. Class imbalance was addressed via upsampling of the positive class within each training split.

Evaluation For each train/validation split, metrics including accuracy, precision, recall, , ROC AUC, and PR AUC were computed. The optimal classification threshold was selected from the precision-recall curve on the validation set. Confusion matrices were averaged across seeds to provide a stable estimate of model performance.

The comparative performance of CNN and LSTM models reflects their differing inductive biases. CNNs are particularly effective at detecting abrupt or localized deviations in trajectory behavior, which are well-represented by short-term temporal patterns. In contrast, LSTMs demonstrate advantages in regions where anomalies emerge gradually or are influenced by cumulative temporal effects, such as slow drift, persistent deviations, or context-dependent behaviors. Geographic variability in model performance suggests that regional dynamics differ in terms of temporal smoothness and noise characteristics. Environments with longer-term temporal structure tend to favor LSTM-based modeling, while more volatile regions benefit from CNN-based local feature extraction.

This detailed architectural description and analysis ensure reproducibility and provide justification for key design choices, including window size, kernel configuration, receptive field considerations, sequence modeling strategy, loss function selection, and training regime, directly addressing reviewer concerns regarding architectural transparency and temporal modeling behavior.

3.5. RAID-Inspired Recovery Simulation

A dataset of GPS trajectories from multiple drifters was utilized. For initial analyses and simulations, a subset of five drifters was selected to illustrate recovery and compression techniques. For each drifter, a contiguous block of 20 consecutive time steps was extracted, resulting in a sample matrix of latitude and longitude coordinates.

To simulate realistic data loss and evaluate reconstruction resilience, a widely used Reed-Solomon (RS) error-correction scheme [79] was applied to the selected trajectory blocks. Each block of GPS data were first flattened and scaled to integers to preserve precision. The data were then encoded with RS codes, with 40 parity bytes to increase recovery robustness.

To model realistic drifter dropouts, five rows (entire time steps) were randomly selected within the trajectory block and were corrupted by setting their byte values to zero. The corrupted data were subsequently decoded using the RS decoder. Reconstruction quality was assessed by computing the mean squared error (MSE) between the original and recovered trajectories. Additionally, a visual comparison of original and recovered trajectories was performed to confirm the fidelity of the reconstruction process. Despite large datasets, this procedure allows an energy-efficient detection and recovery of anomalous drifters.

3.6. Delta Encoding and Compression

To evaluate storage and transmission efficiency, a delta encoding scheme was implemented for the full drifter dataset. Within each drifter group, consecutive latitude and longitude values were differenced to compute “lat_delta” (latitude data) and “lon_delta” (longitude data), respectively, capturing temporal changes instead of absolute positions. The resulting delta values were rounded to five decimal places to reduce data size without compromising significant precision loss.

Both the raw GPS data and the delta-encoded data were exported to CSV format and subsequently compressed using Gzip. Compression efficiency was analyzed globally for the entire dataset as well as individually for each drifter. Metrics included uncompressed size, compressed size, and compression ratio (raw versus delta) [80].

3.7. All Parameters

All experimental parameters are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of experimental parameters used in the anomaly detection pipeline.

4. Results

4.1. Threshold Optimization

For each model, the optimal classification threshold was determined by maximizing the score on the validation set. This procedure accounts for the trade-off between precision and recall in highly imbalanced data. Precision-recall curves and confusion matrices were generated, demonstrating that both models can effectively distinguish anomalous sequences from normal trajectories when thresholds are chosen to balance detection sensitivity and false-alarm rates.

4.2. Performance Metrics

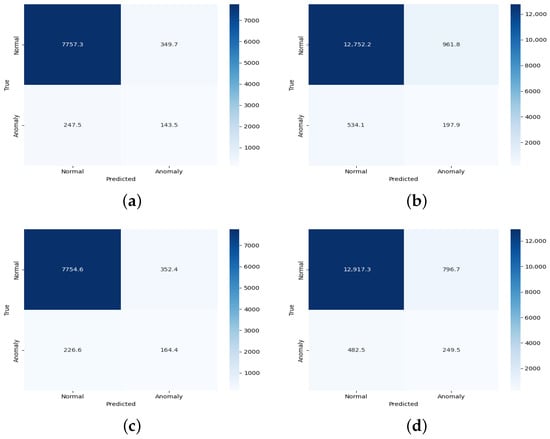

One starts by examining averaged (over 10 independent runs) confusion matrix results for the CNN and LSTM, for the categories of 2010 West Coast, 2010 Gulf of Mexico, 2024 West Coast, and 2024 Gulf of Mexico.

Confusion-matrix conventions.

Recall that for each model the confusion matrix contains the following four values (we adopt the standard convention that the positive class denotes an anomaly):

- (true positive): the true label is an anomaly and is correctly identified by the model (anomaly → anomaly).

- (false positive): the true label is normal but is incorrectly identified as an anomaly (normal → anomaly). Such misclassification is a Type I error (false alarm).

- (true negative): the true label is normal and is correctly identified as normal (normal → normal).

- (false negative): the true label is an anomaly but is incorrectly identified as normal (anomaly → normal). This is a Type II error (missed detection).

Finally, let and , which represent the total number of true anomalies and true normals, respectively.

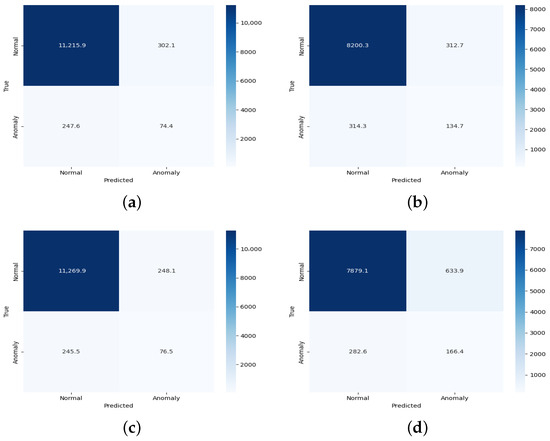

The averaged confusion matrix results for the West Coast are displayed in Figure 5 and summarized in Table 4.

Figure 5.

Confusion matrix results for West Coast (2010 and 2024). (a) CNN 2010 in West Coast. (b) CNN 2024 in West Coast. (c) LSTM 2010 in the West Coast. (d) LSTM 2024 in the West Coast.

Table 4.

Average confusion matrix values for CNN and LSTM across regions and years.

For the West Coast dataset, in 2010, the total number of true “+” and “−” labels were and , respectively. By contrast, in 2024, the total number of true “+” and “−” labels was and , respectively. The total number of labels () increased from 8495 to 14,331, about 70% increase. This is due to a large increase in detection devices. However, we note that the dataset remained highly imbalanced: the proportion of anomalies () in 2010 was about 5.8% and increased to 7.3% in 2024.

The averaged confusion matrix results for the Gulf of Mexico are displayed in Figure 6 and summarized in Table 4.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix results for Gulf of Mexico (2010 and 2024). (a) CNN 2010 in Mexico Gulf. (b) CNN 2024 in Mexico Gulf. (c) LSTM 2010 in Mexico Gulf. (d) LSTM 2024 in Mexico Gulf.

For the Gulf of Mexico, in 2010, the total number of true “+” and “−” labels were and , respectively. By contrast, in 2024, the total number of true “+” and “−” labels was and , respectively. The total number of labels () increased from 11,838 to 11,960, a small 1% increase. This is in contrast to a much larger increase of about 70% for the West Coast. Similarly to the West Coast dataset, the class distribution in this region remains highly imbalanced. The proportion of anomalies () in 2010 was about 3.2% and increased slightly to 3.7%, much less than the increase on the West Coast.

The Gulf of Mexico anomaly rate increased modestly from approximately 3.2% to 3.7%, which is smaller than the West Coast increase but coincides with the timing and location of the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. This suggests a potential correlation between the spill and elevated anomalies, reflecting the influence of large-scale environmental disruptions on the behavior of ocean drifters.

The averaged confusion matrix results are summarized in Table 4. As seen from Table 4, different categories in different time periods and regions show different models as having superior performance, with the CNN model typically more accurate at identifying normal behavior and avoiding false alarms, and the LSTM model typically better at detecting anomalies. The takeaway from this is that the CNN model is more conservative in its performance, as it avoids flagging normal sequences as anomalies, but the LSTM model is more sensitive to anomalies.

4.3. Performance Ratios

Next, the following performance ratios derived from the confusion matrices were examined:

- Accuracy: Fraction of all labels (both positive and negative) that are predicted correctly (). This metric may not be very useful for highly imbalanced datasets, as is the case in this investigation. A simple classifier that assigns all points to be positive (majority) class) will have high accuracy simply by the imbalance

- Precision: Accuracy of positive label predictions ()

- Recall: Sensitivity or True Positive Rate (). This is the proportion of actual positive labels that are correctly identified by a model. This ratio is especially useful for imbalanced datasets, as is the case in this investigation.

- Score: The harmonic mean of the Precision and Recall. This metric (symmetrically) represents both precision and recall in one metric.

- ROC AUC: (Return Operating Characteristics) Area Under the Curve measures the model’s ability to distinguish between positive and negative labels across all thresholds.

- PR AUC: Precision Area under Curve - this is used for heavily imbalanced datasets when optimizing for the positive labels.

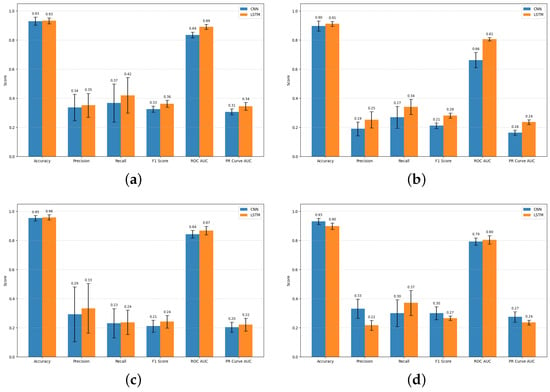

Figure 7 compares standard statistical metrics, such as accuracy, precision, recall, -score, ROC AUC, and PR Curve AUC, of the CNN and LSTM over 10 independent runs. The bar graphs show that across a large majority of runs, the LSTM achieves better metrics than the CNN model. However, in the Mexico Gulf in 2024, the situation is more complex, with the CNN model performing better in some metrics and the LSTM in others.

Figure 7.

Performance Comparison of Metrics (CNN vs. LSTM) across West Coast and Mexico Gulf datasets. (a) West Coast (2010). (b) West Coast (2024). (c) Gulf of Mexico (2010). (d) Gulf of Mexico (2024).

The average metrics from each model during each time period for the West Coast and the Gulf of Mexico are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary of Performance Ratios.

The CNN and LSTM models show different performance patterns across regions and years. On the West Coast datasets, for both 2010 and 2024, the LSTM generally achieves higher precision, recall, score, and ROC AUC than the CNN, suggesting that it benefits from learning temporal dependencies in the drifter trajectories. For instance, in the 2024 West Coast data, the LSTM reached a mean score of 0.282 compared to 0.212 for the CNN.

In contrast, the performance differences between the two models in the Mexican Gulf datasets are less consistent. In the 2010 Gulf data, both models perform similarly, with the LSTM showing a slight advantage in and ROC AUC. However, in the 2024 Gulf data, the CNN achieves higher accuracy and values than the LSTM, suggesting stronger generalization to more recent or spatially variable Gulf conditions. These patterns indicate that the relative strengths of CNN and LSTM architectures may depend on regional and temporal factors in the data, while the LSTM tends to perform better when temporal continuity is prominent, the CNN remains effective under more variable environmental conditions. Further analysis in Section 5 explores these regional and temporal differences in greater depth.

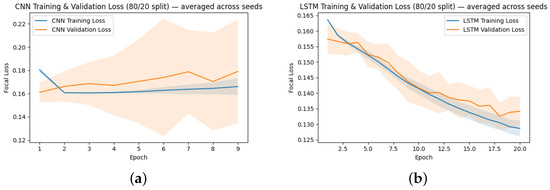

4.4. Model Performance

Training dynamics were monitored using training and validation loss curves for both the CNN and LSTM models, with representative loss curves shown in Figure 8. The CNN’s training loss drops sharply during the first two epochs and then remains essentially flat, with a very small increase of roughly 0.01 between epochs 2 and 9. Its validation loss is comparatively noisy and exhibits a slight upward trend from approximately 0.16 to 0.18 over the same period. These dynamics suggest that the CNN quickly fits simple patterns but gains little additional generalizable structure afterwards and may be sensitive to validation-set noise or mild overfitting. In contrast, the LSTM exhibits steady improvement, with both training and validation losses declining from approximately 0.16 to 0.13 over 20 epochs, indicating more stable optimization and better generalization across epochs. Together, the loss curves explain the observed performance differences. The LSTM’s consistent validation improvement aligns with its higher recall and on held-out data, while the CNN’s flat training curve and slightly rising validation loss are consistent with its more conservative, lower-recall behavior. Note that these descriptions reflect representative runs, and some variability exists across random seeds.

Figure 8.

Performance Comparison of CNN vs. LSTM Models. (a) CNN Loss. (b) LSTM Loss.

4.5. Statistical Testing

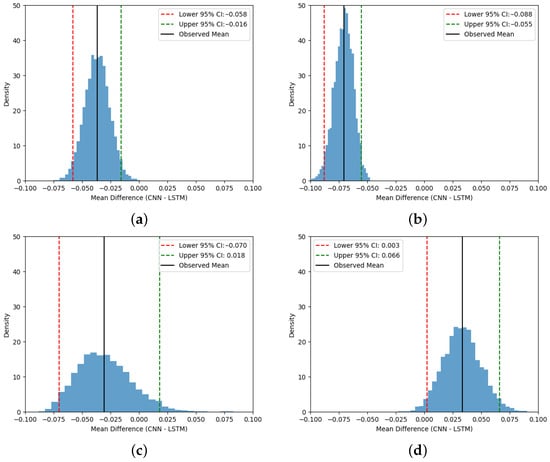

To evaluate the statistical significance of the performance difference between the CNN and LSTM models, we performed a block-shuffled bootstrap analysis on the -scores obtained over 10 experimental runs.

We resampled contiguous blocks of size 2 to partially preserve potential dependence between consecutive runs. Block bootstrap methods are appropriate when the independence assumption is suspect and are designed to retain short-range correlation structure in the resamples [81]. Variants such as overlapping and circular block bootstraps are well studied and are appropriate under weak dependence. We used block shuffling as a pragmatic approach, given the small number of runs. We generated 10,000 bootstrap samples and focused on the mean difference in -score between the CNN and LSTM (CNN–LSTM). Although bootstrapping can provide approximate sampling distributions without strict distributional assumptions, its theoretical justification typically relies on asymptotic arguments where bootstrap confidence intervals may be unstable with very small original samples because the resampled distributions cannot fully reflect the underlying variability [82]. We therefore emphasize caution. The limited number of runs (10) constrains the precision of the inference.

The resulting 95% bootstrap confidence intervals are shown in Figure 9 (West Coast and Gulf of Mexico, 2010 and 2024). Numerically, the bootstrap summaries for mean (CNN–LSTM) and 95% CI are shown in Table 6. The West Coast results are unambiguous: 2010 West Coast (mean = , 95% CI ) and 2024 West Coast (mean = , 95% CI ) both have intervals entirely below zero, indicating that the LSTM outperforms the CNN with the reported confidence. For the Gulf of Mexico, the 2010 interval (mean = , 95% CI ) crosses zero, while the point estimate favors the LSTM, the confidence interval includes zero, and thus the difference is not statistically significant at the 95% level. By contrast, the 2024 Gulf of Mexico interval (mean = , 95% CI ) lies entirely above zero, indicating a statistically supported advantage for the CNN in that region and year.

Figure 9.

Bootstrap Distributions of Mean Differences (CNN–LSTM) across West Coast and Gulf of Mexico datasets. (a) Distribution in 2010 (West Coast). (b) Distribution in 2024 (West Coast). (c) Distribution in 2010 (Gulf of Mexico). (d) Distribution in 2024 (Gulf of Mexico).

Table 6.

Mean (CNN–LSTM) and 95% bootstrap CI for .

The Gulf of Mexico shows a significant temporal shift in model performance. In 2010, despite the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the mean difference between CNN and LSTM performance was similar to that in the West Coast regions, with LSTM outperforming CNN. This can be explained by the LSTM’s ability to capture long-range temporal dependencies in the drifter trajectories, which is particularly useful when the flow patterns are influenced by a strong, localized disturbance such as the oil spill. One can speculate that the spill may have introduced coherent temporal structures in surface currents that the LSTM could exploit, leading to more consistent performance across runs.

By 2024, however, the CNN has a better performance than the LSTM. This reversal likely reflects changes in the Gulf’s dynamics over time, including increased mesoscale variability [83], altered Loop Current behavior [84], and higher spatial heterogeneity [85]. These changes reduce the temporal coherence that benefits the LSTM, while the CNN’s ability to detect short-term, localized patterns becomes more advantageous. Thus, the observed reversal in mean performance is not random but rather demonstrates an evolution in the data regime, where the CNN becomes better suited to capture the anomalies in the 2024 drifter trajectories.

The proportion of anomalies increased on the West Coast but remained largely stable in the Gulf of Mexico. From 2010 and 2024, the West Coast sample size increased by about 70% (8495 to 14,331) and the anomaly rate increased from 5.8% to 7.3%, while the Gulf sample size increased by only 1% (11,838 to 11,960) with a small anomaly rate change (3.2% to 3.7%). The West Coast increase is consistent with expanded detection coverage and may also reflect heightened oceanographic variability. Contrasting this, the Gulf’s persistent mesoscale circulation likely contributed to its relatively stable anomaly proportion.

4.6. Hyperparameter Tuning

To evaluate the influence of hyperparameter values, consider the 2024 West Coast results. The baseline values are as follows:

- 80/20 split of training/testing data with stratification;

- Window size ;

- CNN with two layers;

- LSTM with 64 units per layer.

The models were re-run by changing some of the hyperparameters as follows:

- A larger window size ;

- 50/50 split (as opposed to 80/20);

- CNN with three layers and a larger window size ;

- LSTM with 32 units per layer and a larger window size .

In addition, logistic regression [12] was used as a baseline: this classifier does not require any hyperparameters and is often used as a benchmark in machine learning.

For each new choice of hyperparameters, the models were re-run 10 times. Average performance metrics were computed and summarized in Table 7.

Table 7.

Some Results with Hyperparameter Tuning (West Coast, 2024).

First, consider a split size. For the CNN model, the 50/50 split resulted in a slight increase in the mean score and ROC AUC, indicating that it can handle a larger test set without a significant loss in performance. Yet for the 80/20 split, there is a higher overall accuracy, showing that having more training data benefits the model’s ability to correctly classify the majority of examples. On the other hand, the LSTM model experienced a decrease in overall accuracy and precision with the 50/50 split, indicating that it would benefit from additional training data. These results demonstrate the trade-offs inherent in choosing a train-test split. However, overall, model performance with a 50/50 train-test split is roughly comparable to that with the standard 80/20 split. Given the small differences in accuracy, , and other metrics, the 80/20 split was adopted as the default. This choice ensures sufficient training data for learning while maintaining a reliable test set for evaluation, aligning with common practice for reproducibility and consistency.

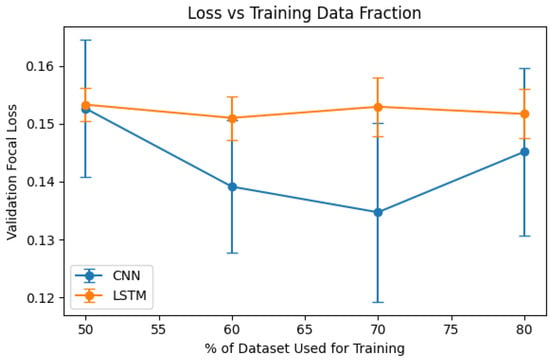

The image below shows a graph of validation loss against percent training data, showing how the validation loss changes with different train/test splits in Figure 10. The CNN consistently achieves lower validation loss than the LSTM, showing that it has better generalization for all the tested data fractions. Overall, the CNN consistently achieves lower validation loss than the LSTM, indicating better generalization across all data fractions. For the CNN, validation loss decreases as the training fraction increases from 50 percent to 70 percent, suggesting improved learning with more data, before slightly increasing at 80 percent, possibly due to variance or mild overfitting. In contrast, the LSTM exhibits relatively stable validation loss across all splits, implying less sensitivity to the amount of training data. The error bars indicate higher variability for the CNN at intermediate splits, while the LSTM remains more consistent but at a higher loss level.

Figure 10.

Graph of Loss vs. Training Data Fraction.

Next, the effect of using a sliding window of instead of the baseline value of was considered. Across the 10 runs, the CNN achieved an average accuracy of approximately 0.86, with an average score of 0.33. Precision and recall show greater variability, reflecting the challenge of detecting the minority class in these dataset. The ROC AUC and PR AUC metrics indicate moderate discriminative performance, consistent with the imbalanced nature of the anomaly detection task. Overall, the model demonstrates stable performance across different seeds with this sliding window configuration. Comparing the CNN results obtained with a sliding window of 20 to the baseline CNN results for the 2024 West Coast in Table 7, one observes that the performance metrics are not substantially different. The per-run accuracy, score, and AUC values with the 20-window sequences are broadly comparable to those reported for the standard configuration, indicating that increasing the window length does not significantly alter overall model performance. This consistency across different input sequence lengths justifies using the approach with a window size of 10 in the evaluation procedure in code, providing a reliable estimate of model performance without additional computational cost.

Next, consider the mean performance metrics for the LSTM model with a sliding window of 20 and the 3-layer Deep CNN, respectively. For the LSTM model with a window of , the average accuracy across 10 runs is approximately 0.851, with an average score of 0.338. Precision shows moderate variability, while recall is relatively high, indicating that the model captures a substantial portion of the positive (anomalous) events. The ROC AUC and PR AUC values suggest moderate discriminative performance.

The 3-layer Deep CNN achieves higher overall accuracy, with 0.922 on average, but slightly lower score compared to the LSTM. Precision and recall are more balanced, and the ROC AUC and PR AUC indicate reliable discrimination of positive events. Overall, both models demonstrate stable performance across runs, with the LSTM better at capturing anomalies and the deep CNN achieving higher overall classification accuracy.

The 2024 West Coast CNN and LSTM models using a sliding window of 20 show performance broadly consistent with the overall confusion matrix results reported in Table 4. For the CNN, the 20-window configuration achieved a mean accuracy of 0.857 and an score of 0.322, which aligns with the higher true positive and true negative counts observed in the 2024 average confusion matrix. The minor differences in performance metrics reflect the variation introduced by the sliding window input sequences, but the overall classification behavior remains similar. Similarly, the LSTM with window shows a mean accuracy of 0.851 and an score of 0.338. This is consistent with the higher true positive count and true negative count for the 2024 West Coast in Table 4. The sliding window approach does not significantly alter the overall model behavior, confirming that the standard evaluation using 10 runs provides a reliable estimate of model performance.

To evaluate the effect of reducing the number of LSTM units, a model with 32 units per layer was trained using the same input data and hyperparameters as the standard LSTM-64 model. Compared to the standard LSTM-64 configuration (mean accuracy 0.851, score 0.338), the LSTM-32 model shows slightly lower accuracy and score, with modest reductions in recall and ROC AUC. Precision remains comparable, suggesting that reducing the number of units has minimal impact on correctly identifying positive events but slightly reduces the model’s overall capacity to capture all anomalies.

Overall, the LSTM-32 model performs reasonably well, providing a lighter alternative to LSTM-64, which trades a small reduction in performance for a decrease in model complexity and computational cost. This suggests that the standard LSTM-64 configuration is preferable when the goal is to maximize anomaly detection performance, while LSTM-32 may be more suitable for faster training or deployment in resource-constrained environments.

Finally, a baseline logistic regression model was also considered in comparison to the CNN and LSTM models. The average performance of a simple linear model, with values averaged over 10 runs, is presented in Table 7.

Logistic regression achieved an average accuracy of 0.888, precision of 0.207, recall of 0.396, score of 0.267, (ROC) AUC of 0.793, and PR AUC of 0.287, while it has a relatively high recall, it is limited in its ability to capture temporal and nonlinear patterns in the drifter trajectories. The CNN and LSTM models use the sequential information within sliding windows, with CNNs capturing local patterns and LSTMs modeling long-range dependencies. In our results, the CNN achieved an accuracy of 0.896, a precision of 0.190, a recall of 0.270, an of 0.212, AUC of 0.662, and PR AUC of 0.164, performing slightly worse than logistic regression in terms of score and ROC AUC. This is likely due to the limited window size () and the relatively small number of sequential features, which reduces the CNN’s ability to capture local patterns. In contrast, the LSTM achieved the best overall performance, with an accuracy of 0.911, precision of 0.252, recall of 0.341, score of 0.282, AUC of 0.806, and PR AUC of 0.236, demonstrating its ability to effectively model long-range temporal dependencies, while CNNs outperform LSTMs in other regions, such as within the 2024 Mexico Gulf data, for the 2024 West Coast trajectories, LSTMs are better suited for high-quality anomaly detection. Logistic regression remains a fast, interpretable baseline or initial filter.

The above results suggest that the choice of CNN and LSTM with baseline values of hyperparameters is appropriate.

5. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive framework for detecting anomalies in ocean drifter trajectories, integrating unsupervised clustering, deep learning, and practical data management strategies. Using DBSCAN to generate per-drifter pseudolabels, the framework accommodates the natural variability of drifter movement and limited labeled data. This approach enables the identification of unusual trajectory behaviors without extensive manual annotation, making it particularly valuable for large-scale environmental datasets.

The results reveal clear regional and temporal differences between the CNN and LSTM models. For the West Coast datasets from 2010 and 2024, the LSTM consistently outperformed the CNN across nearly all of the evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, , ROC AUC, and PR AUC. The bootstrap distributions of mean differences between models for the score were centered below zero, confirming that the LSTM’s advantage was statistically significant. These findings suggest that the LSTM’s strength is capturing temporal dependencies and detecting patterns that evolve over time. Its higher recall signifies strong sensitivity to subtle or extended anomalies, allowing it to identify more true anomalous events, even though this does cause more false alarms. It is likely that the West Coast’s coastal currents, tidal cycles, and persistent environmental patterns create temporal coherence that favors recurrent architectures. The LSTM dominates across both years, supporting the conclusion that these oceanic conditions produce time-dependent behaviors that the model captures effectively.

In the Gulf of Mexico, the results were more variable and appeared to shift over time. During 2010, the LSTM again achieved higher overall performance, indicating that the recurrent model was well suited to the temporally structured anomalies of that period. However, in 2024, the CNN outperformed the LSTM in terms of accuracy, precision, and score, while the LSTM maintained slightly better recall and ROC AUC. The bootstrap analysis for the value confirmed that the CNN’s advantage in this case was statistically meaningful rather than coming from random variation. These results suggest that the Gulf’s 2024 anomalies were more spatially localized or short-lived, making the CNN’s spatial filtering and precision more effective. The CNN thus produced more conservative and reliable anomaly alerts, prioritizing fewer false positives over higher recall. This contrast highlights the trade-off between the two models. The LSTM favors broader temporal sensitivity, while the CNN favors precise, spatially focused detection.

Together, these findings demonstrate that model performance is highly context dependent and influenced by the underlying dynamics of the environment. In regions or periods with strong temporal continuity, recurrent architectures such as LSTMs are more effective, whereas CNNs exhibit better performance in regions dominated by spatially heterogeneous or rapidly changing anomalies. Therefore, for real-world deployment, the optimal model should align with the specific monitoring objective. Systems designed to minimize missed detections, such as those for early warning of environmental disturbances, would benefit from the LSTM’s high recall. On the other hand, applications needing reliability and fewer false alarms may prefer the CNN’s precision. Overall, neither model dominates universally. Rather, their complementary strengths suggest that hybrid or ensemble approaches, combining CNN spatial discrimination with LSTM temporal awareness, may provide the most balanced and adaptive framework for intelligent ocean anomaly detection.

Additionally, our results indicate a regionally heterogeneous change in the prevalence of detected anomalies between 2010 and 2024. Specifically, the West Coast anomaly rate increased from approximately 5.8% to 7.3%. However, the Gulf of Mexico showed a smaller increase from approximately 3.2% to 3.7%. Since the Gulf of Mexico 2010 period encompasses the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, the model’s increased sensitivity to anomalies in 2010 may partially reflect the coherent disturbances caused by the event. These patterns are consistent with anomalies resulting from environmental disruptions, such as the Deepwater Horizon oil spill, but our analysis is correlational. To definitively attribute these anomalies would require event-aligned spatial overlays and per-event statistical tests.

Beyond predictive modeling, the suggested framework addresses practical challenges in long-term drifter monitoring. Simulated recovery of missing trajectory segments and efficient compression strategies ensure scalability and operational feasibility for large datasets, without sacrificing precision.

In general, this study demonstrates a flexible and scalable approach to anomaly detection in ocean drifter trajectories. By tailoring model choice to the environmental context, CNNs and LSTMs together provide a robust framework for capturing both short-term and evolving anomalies. Future work could explore hybrid architectures, additional geographic regions, and real-time validation to further enhance the practical utility of this methodology.

6. Conclusions

In this work, a robust pipeline for ocean drifter anomaly detection was created to address the key gap in the current literature of the lack of an end-to-end, deployable framework for sparse Lagrangian trajectory data able to handle unlabeled anomalies, severe class imbalance, missing data, and operational constraints. Earlier studies have explored clustering, deep learning, or data recovery techniques individually, but this study combines clustering, deep learning, statistical validation, and data management within a single, cohesive framework tailored to drifter observations.

The proposed pipeline has several main achievements. Density-based clustering is employed to achieve per-drifter pseudo-labeling, enabling effective anomaly detection without manual annotation. Sequential deep learning models, including a CNN and LSTM, are trained using a sliding-window formulation. Additionally, focal-loss optimization and bootstrap-based statistical testing provide reliable and imbalance-aware performance evaluation. Empirical results across regions and years indicate that the LSTM generally exhibits stronger anomaly sensitivity, while the CNN displays more conservative behavior with fewer false alarms, highlighting complementary strengths that depend on regional and temporal dynamics.

This work extends beyond mere detection, also incorporating practical system considerations through RAID-inspired recovery simulations and delta-based compression. These components improve resilience to data loss and reduce storage and transmission costs. This addresses the real-world constraints of ocean observing systems. Through the combination of methodological rigor with operational practicality, this study contributes to a scalable, resilient, and environmentally conscious approach to monitoring ocean surface dynamics.

Future work will explore additional machine learning architectures, such as transformer-based models, and look into tighter integration of physical constraints. This can lead to further enhancements in robustness and interpretability in operational ocean monitoring systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A.G. and J.Z.; methodology, C.A.G. and J.Z.; software, C.A.G. and J.Z.; investigation, C.A.G. and J.Z.; data curation, C.A.G. and J.Z.; writing—original draft C.A.G. and J.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.P.; supervision, E.P.; project administration, E.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original data and code presented in this study are openly available in the OceanAnomalyDetection repository at https://github.com/cguo0106/OceanAnomalyDetection, which contains all of the code necessary to reproduce the analyses reported in this paper, including data preprocessing, model training, and evaluation, as well as links to the dataset (accessed on 5 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

We thank Ursula Imbernon, Patrick Bloniasz, Tharunya Katikireddy, Tejovan Parker, Zhengyang Shan, and staff at the Research in Science and Engineering (RISE) Summer 2025 Program at Boston University for their support and guidance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Le Traon, P.Y. From Satellite Altimetry to Argo and Operational Oceanography: Three Revolutions in Oceanography. Ocean Sci. 2013, 9, 901–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, R.; Pazos, M. Measuring Surface Currents with Surface Velocity Program Drifters: The Instrument, Its Data, and Some Recent Results. In Lagrangian Analysis and Prediction of Coastal and Ocean Dynamics; Griffa, A., Kirwan, A.D.J., Mariano, A.J., Özgökmen, T.M., Rossby, H.T., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; pp. 39–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goni, G.J.; Trinanes, J.A.; MacFadyen, A.; Streett, D.; Olascoaga, M.J.; Imhoff, M.L.; Muller-Karger, F.; Roffer, M.A. Variability of the Deepwater Horizon Surface Oil Spill Extent and Its Relationship to Varying Ocean Currents and Extreme Weather Conditions. In Mathematical Modelling and Numerical Simulation of Oil Pollution Problems; Ehrhardt, M., Ed.; The Reacting Atmosphere; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maximenko, N.; Hafner, J.; Niiler, P. Pathways of Marine Debris Derived from Trajectories of Lagrangian Drifters. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2012, 65, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciani, D.; Fanelli, C.; Buongiorno Nardelli, B. Estimating Ocean Currents from the Joint Reconstruction of Absolute Dynamic Topography and Sea Surface Temperature through Deep Learning Algorithms. Ocean Sci. 2025, 21, 199–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, P.; Chen, P.; Fu, X.; Ye, Z.S. Trajectory-based anomaly detection of vessel motion patterns using profile monitoring. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 267, 111815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, W.; Wang, S.; Li, H.; Guan, J.; Zhou, S.; Cao, J. Spatial-Temporal Data Mining for Ocean Science: Data, Methodologies and Opportunities. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2025, 19, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandola, V.; Banerjee, A.; Kumar, V. Anomaly detection: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghbin, M.; Sharafati, A.; Motta, D.; Al-Ansari, N.; Hosseinian Moghadam Noghani, M. Applications of soft computing models for predicting sea surface temperature: A comprehensive review and assessment. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 2021, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panboonyuen, T. SEA-ViT: Forecasting Sea Surface Currents using Vision Transformer and GRU-based Spatio-Temporal Covariance Modeling. In Proceedings of the 2025 17th International Conference on Knowledge and Smart Technology (KST), Bangkok, Thailand, 26 February–1 March 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C. Data Mining: The Textbook; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Everitt, B.S.; Landau, S.; Leese, M.; Stahl, D. Cluster Analysis, 5th ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, R.; Wunsch, D. Survey of clustering algorithms. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2005, 16, 645–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, C.M.; Bishop, H. Deep Learning: Foundations and Concepts; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lara-Benítez, P.; Carranza-García, M.; Riquelme, J.C. An Experimental Review on Deep Learning Architectures for Time Series Forecasting. Int. J. Neural Syst. 2021, 31, 2130001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Gong, R.; Liu, X.; Bai, X.; Song, J.; Sebe, N. Binary Neural Networks: A Survey. Pattern Recognit. 2020, 105, 107281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, C.C.; Reddy, C.K. Data Clustering: Algorithms and Applications; Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery Series; Chapman & Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.; Alqahtani, A.; Jones, M.W.; Xie, X. Deep Time-Series Clustering: A Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 3001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paparrizos, J.; Yang, F.; Li, H. Bridging the Gap: A Decade Review of Time-Series Clustering Methods. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.20582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K. Data Clustering: 50 Years Beyond K-means. Pattern Recogn. Lett. 2010, 31, 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.W. Clustering of Time Series Data—A Survey. Pattern Recognit. 2005, 38, 1857–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ester, M.; Kriegel, H.P.; Sander, J.; Xu, X. A Density-Based Algorithm for Discovering Clusters in Large Spatial Databases with Noise. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Portland, OR, USA, 2–4 August 1996; pp. 226–231. Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3001460.3001507 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Campello, R.J.G.B.; Moulavi, D.; Sander, J. Density-Based Clustering Based on Hierarchical Density Estimates. In Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Pei, J., Tseng, V.S., Cao, L., Motoda, H., Xu, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7819, pp. 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnes, L.; Healy, J.; Astels, S. hdbscan: Hierarchical density based clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, K.; Alam, T.M.; Luo, S.; Shabbir, S.; Hameed, I.A.; Li, J.; Abbas, S.K.; Javed, U. A Review of Time-Series Anomaly Detection Techniques: A Step to Future Perspectives. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Arai, K., Ed.; Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 1363, pp. 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hundman, K.; Constantinou, V.; Laporte, C.; Colwell, I.; Soderstrom, T. Detecting Spacecraft Anomalies Using LSTMs and Nonparametric Dynamic Thresholding. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 9–13 August 2018; pp. 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherstinsky, A. Fundamentals of Recurrent Neural Network (RNN) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) Network. Phys. D Nonlinear Phenom. 2020, 404, 132306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Si, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, J. A Review of Recurrent Neural Networks: LSTM Cells and Network Architectures. Neural Comput. 2019, 31, 1235–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, P.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Anand, G.; Vig, L.; Agarwal, P.; Shroff, G. LSTM-based Encoder-Decoder for Multi-sensor Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1607.00148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.; Kim, D.; Lim, S. Machine Learning-Based Anomaly Detection on Seawater Temperature Data with Oversampling. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruff, L.; Vandermeulen, R.; Görnitz, N.; Deecke, L.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Binder, A.; Müller, E.; Kloft, M. Deep One-Class Classification. In Proceedings of the 35th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 11–13 July 2018; Volume 80, pp. 4393–4402. Available online: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v80/ruff18a.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Chalapathy, R.; Chawla, S. Deep Learning for Anomaly Detection: A Survey. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.03407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonino, G.; Galimberti, G.; Masina, S.; McAdam, R.; Clementi, E. Machine learning methods to predict sea surface temperature and marine heatwave occurrence: A case study of the Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Sci. 2024, 20, 417–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, Y.G.; Kim, J.H.; Luo, J.J. Deep learning for multi-year ENSO forecasts. Nature 2019, 573, 568–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentine, P.; Pritchard, M.; Rasp, S.; Reinaudi, G.; Yacalis, G. Could Machine Learning Break the Convection Parameterization Deadlock? Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 5742–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Song, W.; Huang, D. An Interpretable Deep Learning Approach for Detecting Marine Heatwaves Patterns. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prochaska, J.X.; Cornillon, P.C.; Reiman, D.M. Deep Learning of Sea Surface Temperature Patterns to Identify Ocean Extremes. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.05767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Wang, J.; Yang, Q.; Xie, C. S2-RAID: A New RAID Architecture for Fast Data Recovery. In Proceedings of the 26th IEEE Symposium on Mass Storage Systems and Technologies (MSST), Incline Village, NV, USA, 3–7 May 2010; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelkonen, T.; Franklin, J.; Teller, J.; Cavallaro, P.; Huang, Q.; Meza, J.; Veeraraghavan, K. Gorilla: A Fast, Scalable, In-Memory Time Series Database. Proc. VLDB Endow. 2015, 8, 1816–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, T.M.; Manucharyan, G.E.; Thompson, A.F. Deep learning to infer eddy heat fluxes from sea surface height patterns of mesoscale turbulence. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, H.; Yu, W.; Lian, Z. Influence of Ocean Current Features on the Performance of Machine Learning and Dynamic Tracking Methods in Predicting Marine Drifter Trajectories. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Aouni, A.; Gaudel, Q.; Regnier, C.; Van Gennip, S.; Le Galloudec, O.; Drevillon, M.; Drillet, Y.; Lellouche, J.M. GLONET: Mercator’s End-to-End Global Ocean Forecasting System. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2412.05454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhou, M.; Meng, Q.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Y. CTP: A Hybrid CNN–Transformer–PINN Model for Ocean Front Forecasting. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.10894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thatje, S.; Heilmayer, O.; Laudien, J. Climate variability and El Niño Southern Oscillation: Implications for natural coastal resources and management. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2008, 62, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Ao, Z.; Xiao, K.; Yan, C.; Xin, Q. Gap-Filling and Missing Information Recovery for Time Series of MODIS Data Using Deep Learning-Based Methods. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 4692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, R.W.; Marsico, D.C. An Improved Real-Time Global Sea Surface Temperature Analysis. J. Clim. 1993, 6, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cressie, N.A.C. Statistics for Spatial Data, revised ed.; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, J.M.; Rixen, M. EOF Calculations and Data Filling from Incomplete Oceanographic Datasets. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2003, 20, 1839–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Ma, R.; Duan, H.; Pahlevan, N.; Melack, J.; Shen, M.; Xue, K. A machine learning approach to estimate chlorophyll-a from Landsat-8 measurements in inland lakes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 248, 111974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.y.; Liao, B.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, P.; Huang, J.j. Acoustic localization in ocean reverberation via matrix completion with sensor failure. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 173, 107681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanelli, C.; Ciani, D.; Pisano, A.; Buongiorno Nardelli, B. Deep learning for the super resolution of Mediterranean sea surface temperature fields. Ocean Sci. 2024, 20, 1035–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Xiao, N.; Dong, S. A novel model to predict significant wave height based on long short-term memory network. Ocean Eng. 2020, 205, 107298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A.; Alvera-Azcárate, A.; Licer, M.; Beckers, J. DINCAE 1.0: A convolutional neural network with error estimates to reconstruct sea surface temperature satellite observations. Geosci. Model Dev. 2020, 13, 1609–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]