Harnessing Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides for Sustainable Disease Management in Open Sea Cage Aquaculture

Abstract

1. Introduction

Data Analysis and Visualization

2. Open Sea Cage and Disease Management

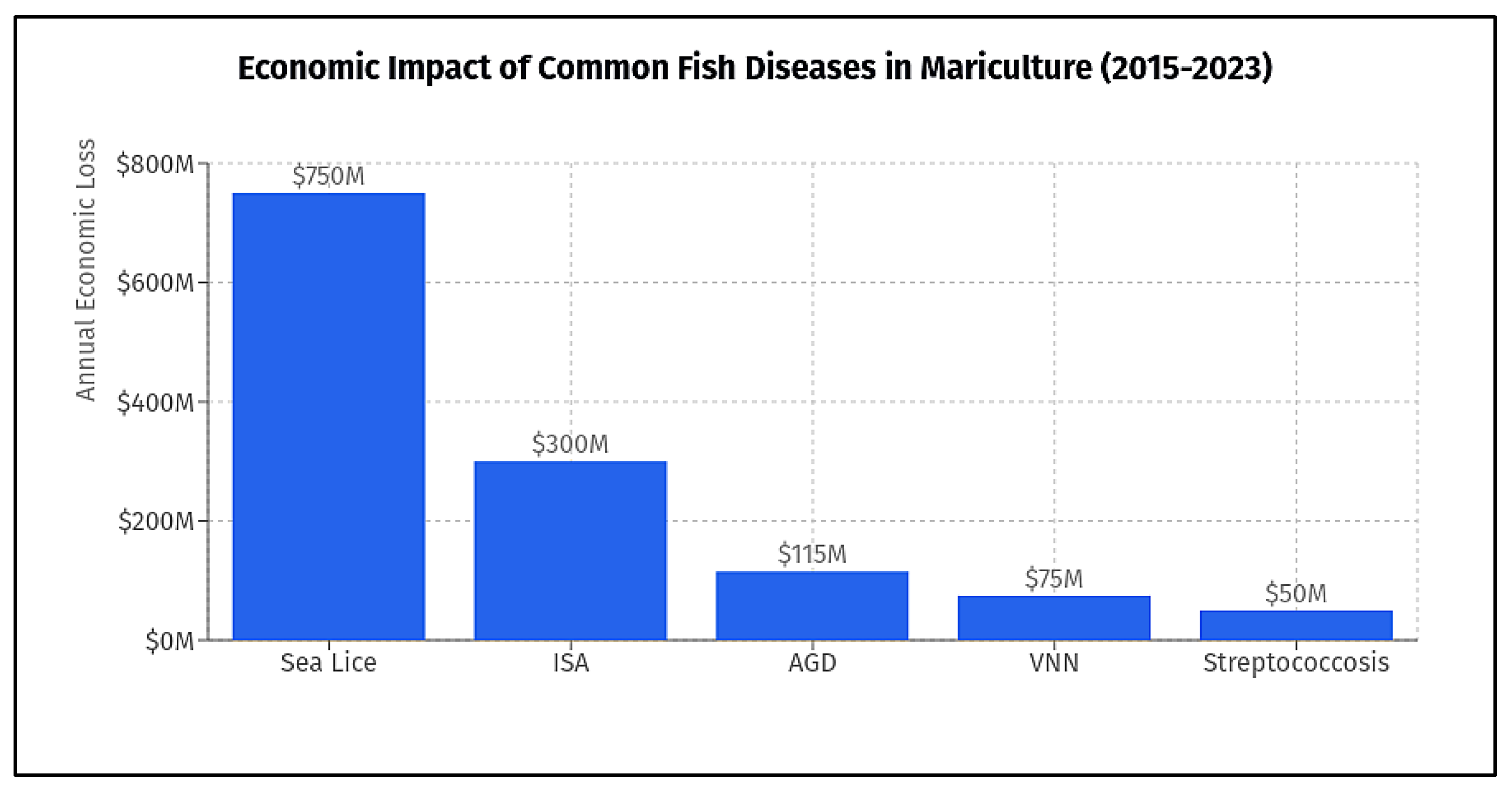

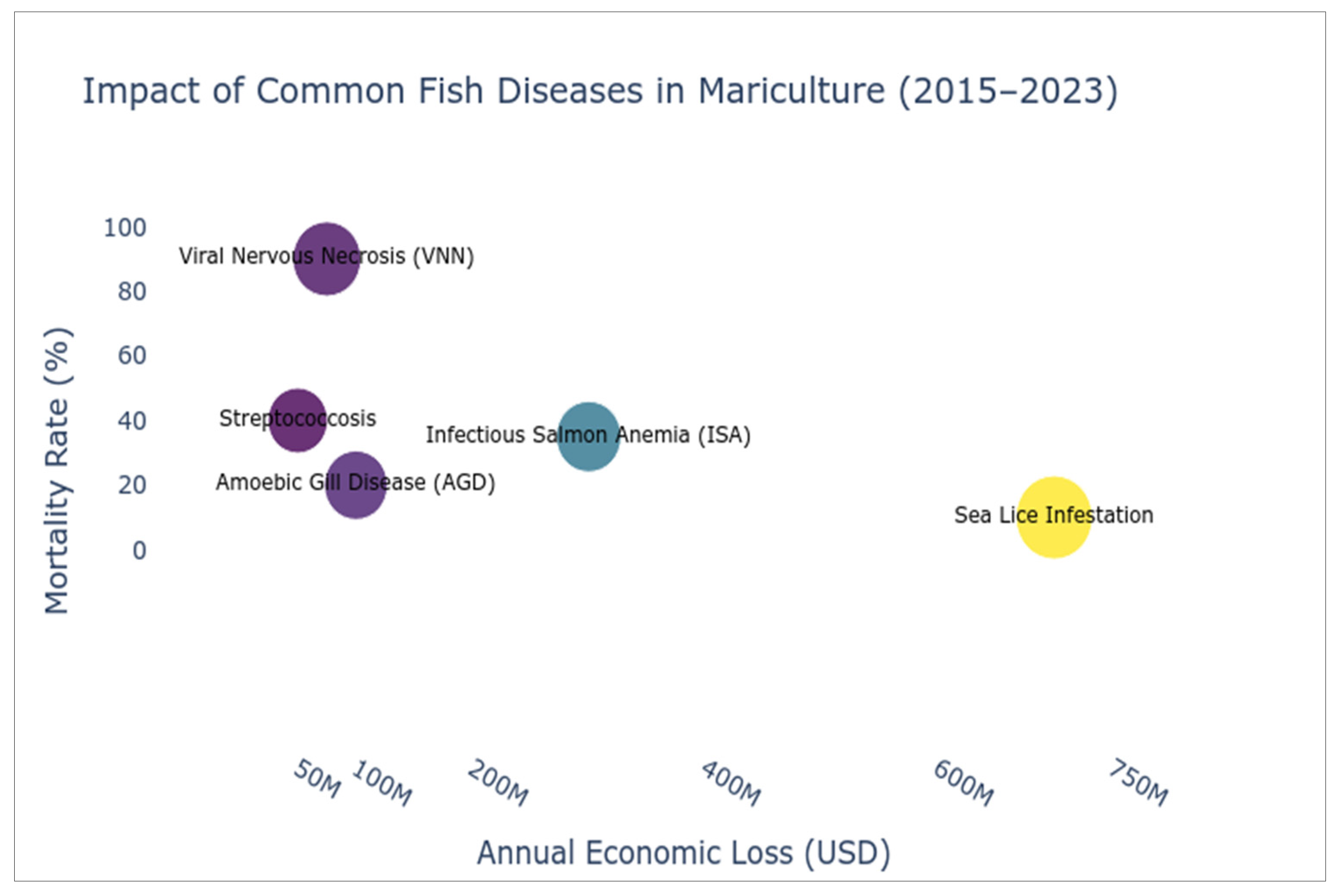

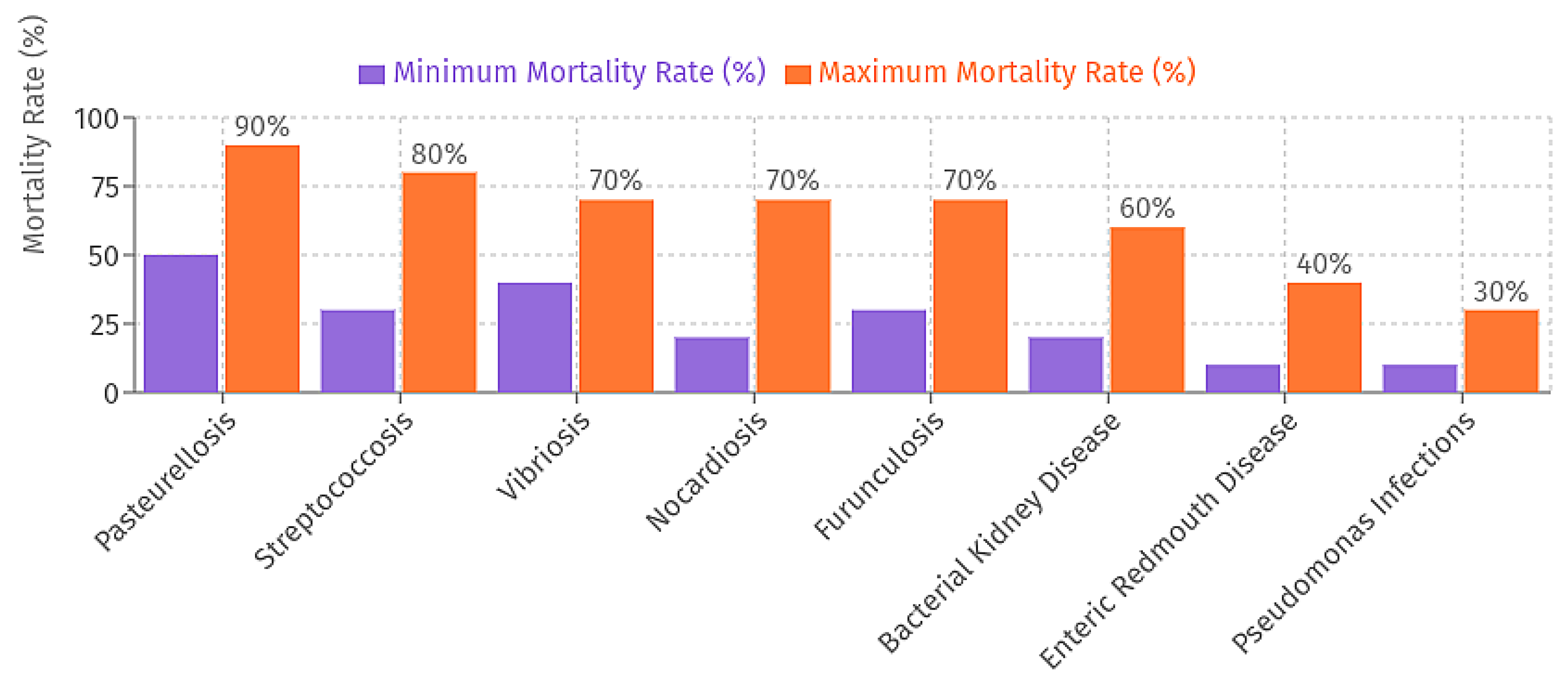

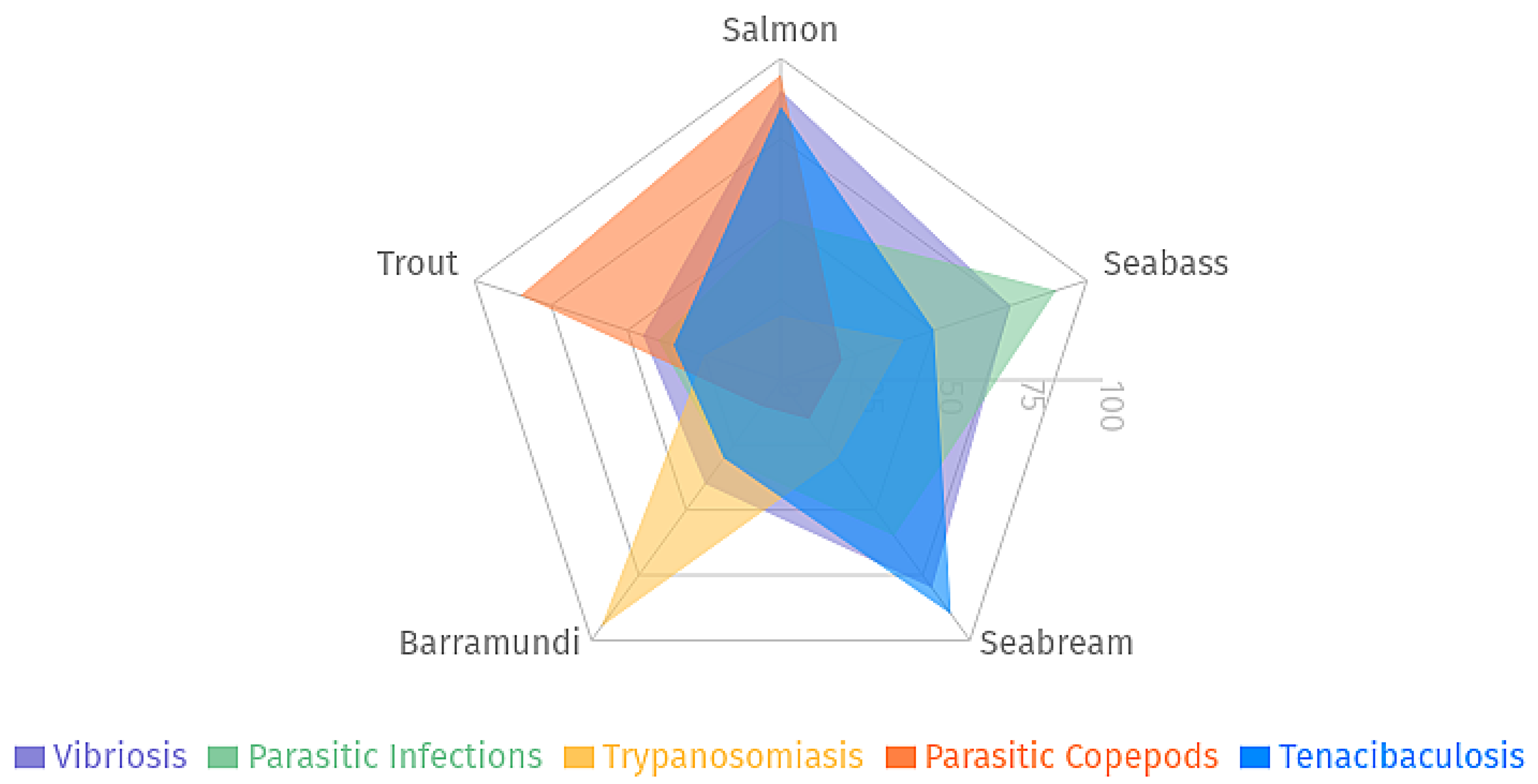

2.1. Predominant Disease Risks

2.2. Economic and Production Impacts

3. Structural Features and Therapeutic Potential of Marine-Derived Lipopeptides

3.1. Structural Diversity and Biosynthesis

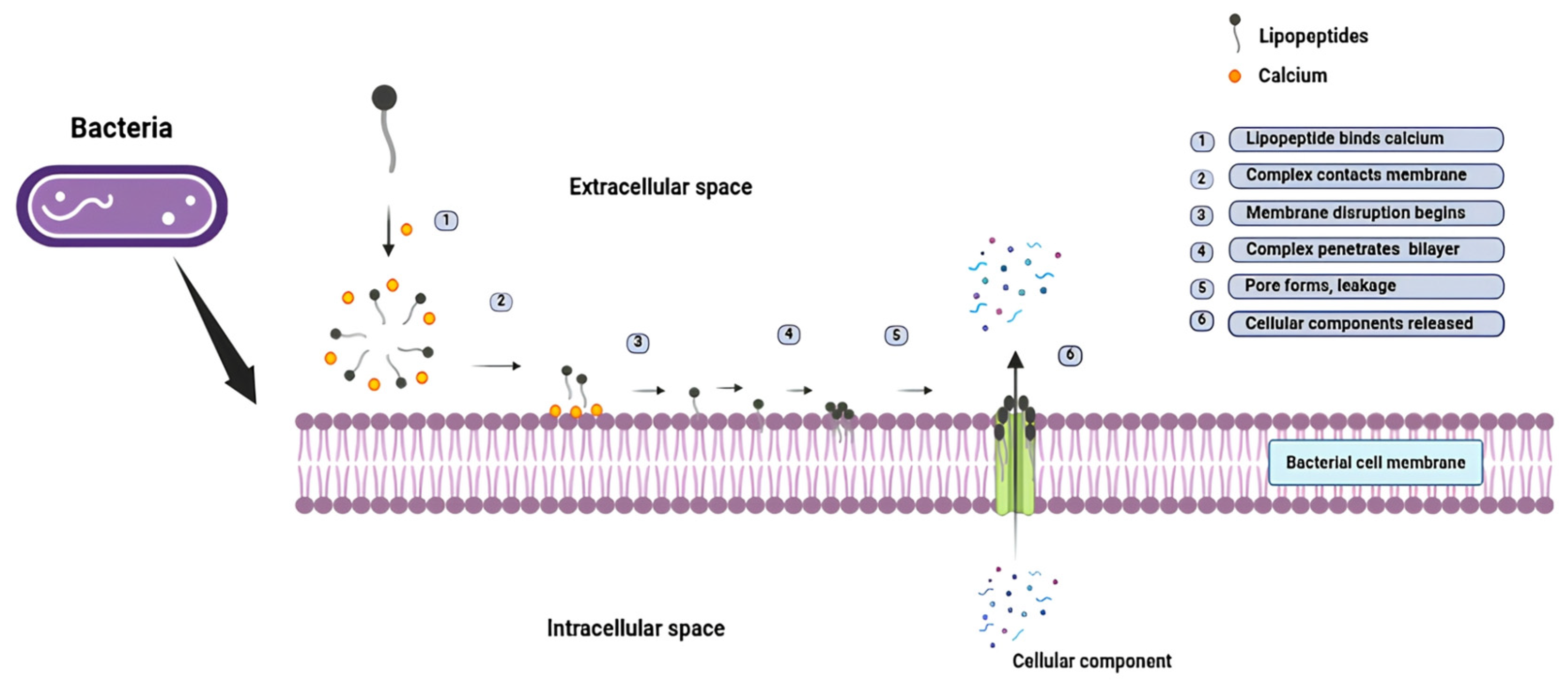

3.2. Mechanisms of Action

3.3. Therapeutic Potential

3.3.1. Evidence in Fish Models

3.3.2. Extrapolations from Non-Fish Systems

4. Multifunctional Lipopeptides for Health Management in Open-Sea Cage Aquaculture

4.1. Antimicrobial Spectrum and Synergistic Interactions

4.2. Antioxidant Properties

4.3. Immunomodulatory Effects

4.4. Delivery Innovations and Regulatory Considerations

5. Antimicrobial and Immunomodulatory Roles of Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides in Sustainable Aquaculture

5.1. Antimicrobial Activity Against Aquaculture Pathogens

5.2. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Effects

5.3. Delivery Methods in Open-Sea Cages

5.4. Stability Challenges

5.5. Impacts on Microbiome

6. Challenges and Future Directions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oddsson, G.V. A Definition of Aquaculture Intensity Based on Production Functions—The Aquaculture Production Intensity Scale (APIS). Water 2020, 12, 765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sumaila, U.R.; Pierruci, A.; Oyinlola, M.A.; Cannas, R.; Froese, R.; Glaser, S.; Jacquet, J.; Kaiser, B.A.; Issifu, I.; Micheli, F.; et al. Aquaculture Over-Optimism? Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 984354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoto, R.; Uehara, M.; Seki, D.; Kinjo, M.; Omoto, R.; Uehara, M.; Seki, D.; Kinjo, M. Supply Chain-Based Coral Conservation: The Case of Mozuku Seaweed Farming in Onna Village, Okinawa. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Soratur, A.; Kumar, S.; Venmathi Maran, B.A. A Review of Marine Algae as a Sustainable Source of Antiviral and Anticancer Compounds. Macromol 2025, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics—Yearbook 2021; FAO Yearbook of Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akintola, S.L.; Chávez-Chong, C.O.; Arencibia-Jorge, R.; Chong-Carrillo, O.C.-C.; García-Guerrero, M.U.; Michán-Aguirre, L.; Nolasco-Soria, H.; Cupul-Magaña, F.; Vega-Villasante, F. The Prawns of the Genus Macrobrachium (Crustacea, Decapoda, Palaemonidae) with Commercial Importance: A Patentometric View. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2016, 44, 602–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mair, G.C.; Halwart, M.; Derun, Y.; Costa-Pierce, B.A. A Decadal Outlook for Global Aquaculture. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2023, 54, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2024–2033; OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vorona, N.; Iegorov, B. Fish Farming is A Promising Branch of Ensuring Food Security of the Earth’s Population. Grain Prod. Mix. Fodder’s 2023, 23, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrektsen, S.; Kortet, R.; Skov, P.V.; Ytteborg, E.; Gitlesen, S.; Kleinegris, D.; Mydland, L.-T.; Hansen, J.Ø.; Lock, E.-J.; Mørkøre, T.; et al. Future Feed Resources in Sustainable Salmonid Production: A Review. Rev. Aquac. 2022, 14, 1790–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.L.; Asche, F.; Garlock, T. Economics of Aquaculture Policy and Regulation. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2019, 11, 101–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S. Aquaculture: A Boon to Today’s World-A Review. J. Ecol. Nat. Resour. 2023, 7, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, N.F.; Yacout, D.M.M. Aquaculture in Egypt: Status, Constraints and Potentials. Aquacult Int. 2016, 24, 1201–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickney, R.R.; Treece, G.D. History of Aquaculture. In Aquaculture Production Systems; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 15–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, G.L.; Fielder, D.S.; Fitzsimmons, K.M.; Applebaum, S.L.; Raizada, S. Inland Saline Aquaculture. In New Technologies in Aquaculture; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2009; pp. 1119–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, X.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Zhang, G.; et al. Freshwater Aquaculture Mapping in “Home of Chinese Crawfish” by Using a Hierarchical Classification Framework and Sentinel-1/2 Data. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M. Study on Water Purification of Freshwater Aquaculture Pond Based on Correlation Analysis. Front. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2023, 5, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathor, G.S.; Swain, B.; Rathor, G.S.; Swain, B. Advancements in Fish Vaccination: Current Innovations and Future Horizons in Aquaculture Health Management. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, J.; Vaishnav, A.; Deb, S.; Kashyap, S.; Debbarma, P.; Devati; Gautam, P.; Pavankalyan, M.; Kumari, K.; Verma, D.K. Re-Circulatory Aquaculture Systems: A Pathway to Sustainable Fish Farming. Arch. Curr. Res. Int. 2024, 24, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azra, M.N.; Okomoda, V.T.; Tabatabaei, M.; Hassan, M.; Ikhwanuddin, M. The Contributions of Shellfish Aquaculture to Global Food Security: Assessing Its Characteristics From a Future Food Perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 8, 654897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumoto, T. Yellowtail, Seriola Quinqueradiata. In Nutrient Requirements and Feeding of Finfish for Aquaculture; CABI Books: Wallingford, UK, 2002; pp. 131–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, L.N. Sea-Cage Aquaculture, Sea Lice, and Declines of Wild Fish. Conserv. Biol. 2009, 23, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debnath, P.P.; Chokmangmeepisarn, P.; Papadopoulou, A.; Coyle, N.M.; Baker-Austin, C.; van Aerle, R.; Bass, D.; Tyler, C.R.; Rodkhum, C. Diversity and Antimicrobial Resistance among Bacterial Isolates from Finfish Aquaculture in Thailand. BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karnatak, G.; Das, B.K.; Parida, P.; Roy, A.; Das, A.K.; Lianthuamluaia, L.; Ekka, A.; Chakraborty, S.; Mondal, K.; Debnath, S. Effectiveness of Pen Aquaculture in Enhancing Small Scale Fisheries Production and Conservation in a Wetland of India. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 8, 1506096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, R.; Lee, H.B. Commercial Marine Fish Farming in Singapore. Aquac. Res. 1997, 28, 767–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merma, W. Development of a Technological System of Floating Cages in the Sea for the Farming of Marine Fish Within the Coastline of ILO. J. Electr. Syst. 2024, 20, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, H.; An, S.; Kim, C.-H.; Park, S.-H.; Kim, Y.-W.; Lim, S.-H. Remote Monitoring System Based on Ocean Sensor Networks for Offshore Aquaculture. In Proceedings of the 2014 Oceans-St. John’s, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 14–19 September 2014; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X. A Remote Acoustic Monitoring System for Offshore Aquaculture Fish Cage. In Proceedings of the 2007 14th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice, Xiamen, China, 4–6 December 2007; pp. 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wei, Q.; An, D. Intelligent Monitoring and Control Technologies of Open Sea Cage Culture: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 169, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupesha Sharma, S.R.; Rathore, G.; Verma, D.K.; Sadhu, N.; Philipose, K.K. Vibrio alginolyticus Infection in Asian Seabass (Lates Calcarifer, Bloch) Reared in Open Sea Floating Cages in India. Aquac. Res. 2012, 44, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milich, M.; Drimer, N. Design and Analysis of an Innovative Concept for Submerging Open-Sea Aquaculture System. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2019, 44, 707–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, A.; Sánchez, P.; Armesto, J.A.; Guanche, R.; Ondiviela, B.; Juanes, J.A. Experimental and Numerical Modelling of an Offshore Aquaculture Cage for Open Ocean Waters. In Proceedings of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Digital Collection 2018, Madrid, Spain, 17–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moe, H.; Dempster, T.; Sunde, L.M.; Winther, U.; Fredheim, A. Technological Solutions and Operational Measures to Prevent Escapes of Atlantic Cod (Gadus Morhua) from Sea Cages. Aquac. Res. 2007, 38, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, T.; Arai, K.; Kobayashi, T. Smart Aquaculture System: A Remote Feeding System with Smartphones. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 23rd International Symposium on Consumer Technologies (ISCT), Ancona, Italy, 19–21 June 2019; IEEE: Ancona, Italy, 2019; pp. 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Wang, G.; Guan, C. Numerical and Experimental Investigations of Hydrodynamics of a Fully-Enclosed Pile-Net Aquaculture Pen in Regular Waves. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1175852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divu, D.; Mojjada, S.K.; Muktha, M.; Azeez, P.A.; Tade, M.S.; Subramanian, A.; Shree, J.; Anulekshmi, C.; Babu, P.P.S.; Anuraj, A.; et al. Mapping of Potential Sea-Cage Farming Sites Throughspatial Modelling: Preliminary Operative Suggestionsto Aid Sustainable Mariculture Expansion in India: Spatial Model Optimization for Sea Cage Farming Site Suitability Mapping. Indian J. Fish. 2023, 70, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmos, J.; López, L.M.; Gorriño, A.; Galaviz, M.A.; Mercado, V. Bacillus Subtilis Effects on Growth Performance and Health Status of Totoaba Macdonaldi Fed with High Levels of Soy Protein Concentrate. Animals 2022, 12, 3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, G.C.; Balian, S.D.C.; Soares, H.S.; Martins, M.L.; Salerno, G.; Hansen, M.J.; Cardoso, P.H.M. The Effect of BiokosTM, a Natural Lipopeptide Surfactant Extracted from the Bacterium Pseudomonas, on Epistylis Infections in Carassius Auratus. Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Veterinária 2024, 33, e009424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Deng, J.; Ye, Z.; Gan, M.; Wang, K.; Wu, J.; Yang, W.; Xiao, G. Coastal Aquaculture Mapping from Very High Spatial Resolution Imagery by Combining Object-Based Neighbor Features. Sustainability 2019, 11, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, P.; Neto, I.A.; Brandão, H.; Furtado, P.; Poersch, L.; Wasielesky, W. Effects of Magnesium Reduction in Artificial Low-Salinity Water on the Growth of Pacific White Shrimp Litopenaeus Vannamei in a Biofloc System. Aquaculture 2023, 577, 739956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piroddi, C.; Bearzi, G.; Christensen, V. Marine Open Cage Aquaculture in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea: A New Trophic Resource for Bottlenose Dolphins. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2011, 440, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.B.; Nur, A.-A.U.; Ahmed, M.M.; Ullah, M.A.; Albeshr, M.F.; Arai, T. Growth, Yield and Profitability of Major Carps Culture in Coastal Homestead Ponds Stocked with Wild and Hatchery Fish Seed. Agriculture 2022, 12, 1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsoglou, S.; Costello, M.J.; Tziha, G. Environmental Conditions at Sea-Cages, and Ectoparasites on Farmed European Sea-Bass, Dicentrarchus Labrax (L.), and Gilt-Head Sea-Bream, Sparus Aurata L., at Two Farms in Greece. Aquac. Res. 1996, 27, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stickney, R.R.; Gatlin Iii, D. Aquaculture: An Introductory Text, 4th ed.; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reshma, B.; Kumar, S.S. Precision Aquaculture Drone Algorithm for Delivery in Sea Cages. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Engineering and Technology (ICETECH), Coimbatore, India, 17–18 March 2016; IEEE: Coimbatore, India, 2016; pp. 1264–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, L.; MacKinnon, B.; St-Hilaire, S. Infectious Diseases Reported in Warm-water Marine Fish Cage Culture in East and Southeast Asia—A Systematic Review. Aquac. Res. 2022, 53, 2081–2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.; Xu, L.W.; Liu, X.H.; Sato, H.; Zhang, J.Y. Outbreak of Trypanosomiasis in Net-Cage Cultured Barramundi, Lates Calcarifer (Perciformes, Latidae), Associated with Trypanosoma Epinepheli (Kinetoplastida) in South China Sea. Aquaculture 2019, 501, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papapetrou, M.; Kazlari, Z.; Papanna, K.; Papaharisis, L.; Oikonomou, S.; Manousaki, T.; Loukovitis, D.; Kottaras, L.; Dimitroglou, A.; Gourzioti, E.; et al. On the Trail of Detecting Genetic (Co)Variation between Resistance to Parasite Infections (Diplectanum aequans and Lernanthropus kroyeri) and Growth in European Seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax). Aquac. Rep. 2021, 20, 100767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delannoy, C.M.J.; Houghton, J.D.R.; Fleming, N.E.C.; Ferguson, H.W. Mauve Stingers (Pelagia noctiluca) as Carriers of the Bacterial Fish Pathogen Tenacibaculum Maritimum. Aquaculture 2011, 311, 255–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haenen, O.L.M.; Evans, J.J.; Berthe, F. Bacterial Infections from Aquatic Species: Potential for and Prevention of Contact Zoonoses: -EN- -FR- Infections Bactériennes d’origine Aquatique: Risques d’exposition Zoonotique Par Contact et Prévention -ES- Infecciones Bacterianas Procedentes de Especies Acuáticas: Probabilidad y Prevención de Las Zoonosis Por Contacto. Rev. Sci. Tech. (Int. Off. Epizoot.) 2013, 32, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantrakajorn, S.; Maisak, H.; Wongtavatchai, J. Comprehensive Investigation of Streptococcosis Outbreaks in Cultured Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, and Red Tilapia, Oreochromis Sp., of Thailand. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2014, 45, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, C.R.; Collins, M.D.; Toranzo, A.E.; Barja, J.L.; Romalde, J.L. 16S rRNA Gene Sequence Analysis of Photobacterium Damselae and Nested PCR Method for Rapid Detection of the Causative Agent of Fish Pasteurellosis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 2942–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Fernández, E.; Chinchilla, B.; Rebollada-Merino, A.; Domínguez, L.; Rodríguez-Bertos, A. An Outbreak of Aeromonas Salmonicida in Juvenile Siberian Sturgeons (Acipenser baerii). Animals 2023, 13, 2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botwright, N.A.; Mohamed, A.R.; Slinger, J.; Lima, P.C.; Wynne, J.W. Host-Parasite Interaction of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar) and the Ectoparasite Neoparamoeba Perurans in Amoebic Gill Disease. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 672700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okon, E.M.; Okocha, R.C.; Taiwo, A.B.; Michael, F.B.; Bolanle, A.M. Dynamics of Co-Infection in Fish: A Review of Pathogen-Host Interaction and Clinical Outcome. Fish Shellfish Immunol. Rep. 2023, 4, 100096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobback, E.; Decostere, A.; Hermans, K.; Haesebrouck, F.; Chiers, K. Yersinia ruckeri Infections in Salmonid Fish. J. Fish Dis. 2007, 30, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulu, S.; Hasimuna, O.J.; Haambiya, L.H.; Monde, C.; Musuka, C.G.; Makorwa, T.H.; Munganga, B.P.; Phiri, K.J.; Nsekanabo, J.D. Climate Change Effects on Aquaculture Production: Sustainability Implications, Mitigation, and Adaptations. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 609097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.; Eissa, A.E. Diagnostic Testing Patterns of Renibacterium Salmoninarum in Spawning Salmonid Stocks in Michigan. J. Wildl. Dis. 2009, 45, 447–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, E.L.; Mlotkowski, A.J.; Hebert, S.P.; Schlegel, H.B.; Chow, C.S. Calculations of pKa Values for a Series of Naturally Occurring Modified Nucleobases. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 1518–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maezono, M.; Nielsen, R.; Buchmann, K.; Nielsen, M. The Current State of Knowledge of the Economic Impact of Diseases in Global Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2025, 17, e70039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J.; Adams, M.; Jantawongsri, K.; Dempster, T.; Nowak, B.F. Evaluation of Low Temperature and Salinity as a Treatment of Atlantic Salmon against Amoebic Gill Disease. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deshotel, M.B.; Dave, U.M.; Farmer, B.; Kemboi, D.; Nelson, D.C. Bacteriophage Endolysin Treatment for Systemic Infection of Streptococcus Iniae in Hybrid Striped Bass. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2024, 145, 109296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Itano, T.; Kawakami, H.; Kono, T.; Sakai, M. Experimental Induction of Nocardiosis in Yellowtail, Seriola Quinqueradiata Temminck & Schlegel by Artificial Challenge. J. Fish Dis. 2006, 29, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-del Campo, S.; Díaz-Martínez, L.; Moreno, P.; García-Rosado, E.; Alonso, M.C.; Béjar, J.; Grande-Pérez, A. The Genetic Variability and Evolution of Red-Spotted Grouper Nervous Necrosis Virus Quasispecies Can Be Associated with Its Virulence. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1182695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiklund, T. Pseudomonas Anguilliseptica Infection as a Threat to Wild and Farmed Fish in the Baltic Sea. Microbiol. Aust. 2016, 37, 135–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightner, D.V. Biosecurity in Shrimp Farming: Pathogen Exclusion through Use of SPF Stock and Routine Surveillance. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2007, 36, 229–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marana, M.H.; Jørgensen, L.V.G.; Skov, J.; Chettri, J.K.; Holm Mattsson, A.; Dalsgaard, I.; Kania, P.W.; Buchmann, K. Subunit Vaccine Candidates against Aeromonas Salmonicida in Rainbow Trout Oncorhynchus Mykiss. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0171944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Yazid, S.H.; Mohd Daud, H.; Azmai, M.N.A.; Mohamad, N.; Mohd Nor, N. Estimating the Economic Loss Due to Vibriosis in Net-Cage Cultured Asian Seabass (Lates Calcarifer): Evidence From the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021, 8, 644009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohani, F.; Islam, S.M.; Hossain, K.; Ferdous, Z.; Siddik, M.A.; Nuruzzaman, M.; Padeniya, U.; Brown, C.; Shahjahan, M. Probiotics, Prebiotics and Synbiotics Improved the Functionality of Aquafeed: Upgrading Growth, Reproduction, Immunity and Disease Resistance in Fish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2022, 120, 569–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougin, J.; Joyce, A. Fish Disease Prevention via Microbial Dysbiosis-associated Biomarkers in Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2023, 15, 579–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal, J.F.; Santos, E.B.H.; Esteves, V.I. Oxytetracycline in Intensive Aquaculture: Water Quality during and after Its Administration, Environmental Fate, Toxicity and Bacterial Resistance. Rev. Aquac. 2019, 11, 1176–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, Z.H.A.; Al-Sahlany, S.T.G. Bacterial Biosurfactants as Bioactive Ingredients: Surfactin’s Role in Food Preservation, Functional Foods, and Human Health. Bacteria 2025, 4, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnif, I.; Ghribi, D. Review Lipopeptides Biosurfactants: Mean Classes and New Insights for Industrial, Biomedical, and Environmental Applications. Biopolymers 2015, 104, 129–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanif, A.; Zhang, F.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Zubair, M.; Zhang, M.; Jia, D.; Zhao, X.; Liang, J.; et al. Fengycin Produced by Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens FZB42 Inhibits Fusarium Graminearum Growth and Mycotoxins Biosynthesis. Toxins 2019, 11, 295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, E.; Yousef, A.E. The Lipopeptide Antibiotic Paenibacterin Binds to the Bacterial Outer Membrane and Exerts Bactericidal Activity through Cytoplasmic Membrane Damage. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2700–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kowall, M.; Vater, J.; Kluge, B.; Stein, T.; Franke, P.; Ziessow, D. Separation and Characterization of Surfactin Isoforms Produced byBacillus subtilisOKB 105. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1998, 204, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra, B.; Ramón, D.J. Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Sustainable Medium for C–C Bond Formation Via Multicomponent Radical Conjugate Additions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 7941–7947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Zhu, H.; Cui, Q.; Wang, B.; Su, H.; Zhang, Y. Anaerobic Production of Surfactin by a New Bacillus Subtilis Isolate and the in Situ Emulsification and Viscosity Reduction Effect towards Enhanced Oil Recovery Applications. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 201, 108508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, P.I.; Ryu, J.; Kim, Y.H.; Chi, Y.-T. Production of Biosurfactant Lipopeptides Iturin A, Fengycin and Surfactin A from Bacillus Subtilis CMB32 for Control of Colletotrichum Gloeosporioides. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 20, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Singh, S.S.; Baindara, P.; Sharma, S.; Khatri, N.; Grover, V.; Patil, P.B.; Korpole, S. Surfactin Like Broad Spectrum Antimicrobial Lipopeptide Co-Produced with Sublancin From Bacillus Subtilis Strain A52: Dual Reservoir of Bioactives. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janek, T.; Drzymała, K.; Dobrowolski, A. In Vitro Efficacy of the Lipopeptide Biosurfactant Surfactin-C15 and Its Complexes with Divalent Counterions to Inhibit Candida Albicans Biofilm and Hyphal Formation. Biofouling 2020, 36, 210–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Guan, Z.; Cai, Y.; Liao, X. Antifungal Activity of Isolated Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens SYBC H47 for the Biocontrol of Peach Gummosis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0162125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Xu, M.; Xue, J.; Shi, K.; Gu, M. Characterization and Enhanced Degradation Potentials of Biosurfactant-Producing Bacteria Isolated from a Marine Environment. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 1645–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ma, X. Purification and Characterization of Lipopeptides Produced by Bacillus Subtilius and Their Antibacterial Effects on Escherichia Coli and Staphylococcus Aureus. Process Biochem. 2024, 146, 44–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollenbroich, D.; Özel, M.; Vater, J.; Kamp, R.M.; Pauli, G. Mechanism of Inactivation of Enveloped Viruses by the Biosurfactant Surfactin fromBacillus Subtilis. Biologicals 1997, 25, 289–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farace, G.; Fernandez, O.; Jacquens, L.; Coutte, F.; Krier, F.; Jacques, P.; Clément, C.; Barka, E.A.; Jacquard, C.; Dorey, S. Cyclic Lipopeptides from B Acillus Subtilis Activate Distinct Patterns of Defence Responses in Grapevine. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2015, 16, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Sun, C. Fengycins, Cyclic Lipopeptides from Marine Bacillus Subtilis Strains, Kill the Plant-Pathogenic Fungus Magnaporthe Grisea by Inducing Reactive Oxygen Species Production and Chromatin Condensation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018, 84, e00445-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneja, N.; Kaur, H. Insights into Newer Antimicrobial Agents against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Microbiol. Insights 2016, 9, MBI.S29459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantil, E.; Crippin, T.; Avis, T.J. Domain Redistribution within Ergosterol-Containing Model Membranes in the Presence of the Antimicrobial Compound Fengycin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2019, 1861, 738–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemil, N.; Ben Ayed, H.; Manresa, A.; Nasri, M.; Hmidet, N. Antioxidant Properties, Antimicrobial and Anti-Adhesive Activities of DCS1 Lipopeptides from Bacillus Methylotrophicus DCS1. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perron, N.R.; Brumaghim, J.L. A Review of the Antioxidant Mechanisms of Polyphenol Compounds Related to Iron Binding. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2009, 53, 75–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bricknell, I.; Dalmo, R. The Use of Immunostimulants in Fish Larval Aquaculture. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2005, 19, 457–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.Y.; Nan, X.; Jin, M.S.; Youn, S.-J.; Ryu, Y.H.; Mah, S.; Han, S.H.; Lee, H.; Paik, S.-G.; Lee, J.-O. Recognition of Lipopeptide Patterns by Toll-like Receptor 2-Toll-like Receptor 6 Heterodimer. Immunity 2009, 31, 873–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thongjun, J.; Tansila, N.; Panthong, K.; Tanskul, S.; Nishibuchi, M.; Vuddhakul, V. Inhibitory Potential of Biosurfactants from Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens Derived from Mangrove Soil against Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. Ann. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1257–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baena-Nogueras, R.M.; González-Mazo, E.; Lara-Martín, P.A. Degradation Kinetics of Pharmaceuticals and Personal Care Products in Surface Waters: Photolysis vs Biodegradation. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 590–591, 643–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, D.; Phelan, A.; Murphy, C.D.; Cobb, S.L. Fengycin A Analogues with Enhanced Chemical Stability and Antifungal Properties. Org. Lett. 2021, 23, 4672–4676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, G.; Zhou, S.; Sha, Z.; Sun, C. Characterization of Antifungal Lipopeptide Biosurfactants Produced by Marine Bacterium Bacillus Sp. CS30. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvaraj, S.; Yasin, I.S.M.; Karim, M.M.A.; Saad, M.Z. Elucidating the Efficacy of Vaccination against Vibriosis in Lates Calcarifer Using Two Recombinant Protein Vaccines Containing the Outer Membrane Protein K (r-OmpK) of Vibrio Alginolyticus and the DNA Chaperone J (r-DnaJ) of Vibrio Harveyi. Vaccines 2020, 8, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiu, P.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Sun, C. Pumilacidin-Like Lipopeptides Derived from Marine Bacterium Bacillus Sp. Strain 176 Suppress the Motility of Vibrio Alginolyticus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 83, e00450-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Kim, K.; Han, H.S.; Moniruzzaman, M.; Yun, H.; Lee, S.; Bai, S.C. Optimum Dietary Protein Level and Protein-to-energy Ratio for Growth of Juvenile Parrot Fish, Oplegnathus fasciatus. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2017, 48, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H.; Wu, K.; Chu, T.-W.; Wu, T.-M. Dietary Supplementation of Probiotic, Bacillus Subtilis E20, Enhances the Growth Performance and Disease Resistance against Vibrio Alginolyticus in Parrot Fish (Oplegnathus Fasciatus). Aquacult Int. 2018, 26, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Marín-Juez, R.; Meijer, A.H.; Spaink, H.P. Common and Specific Downstream Signaling Targets Controlled by Tlr2 and Tlr5 Innate Immune Signaling in Zebrafish. BMC Genom. 2015, 16, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke, E.S.; Chukwudozie, K.I.; Nyaruaba, R.; Ita, R.E.; Oladipo, A.; Ejeromedoghene, O.; Atakpa, E.O.; Agu, C.V.; Okoye, C.O. Antibiotic Resistance in Aquaculture and Aquatic Organisms: A Review of Current Nanotechnology Applications for Sustainable Management. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 69241–69274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Chen, S.; Yu, X.; Wan, C.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Li, Q. Sources of Lipopeptides and Their Applications in Food and Human Health: A Review. Foods 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markelova, N.; Chumak, A. Antimicrobial Activity of Bacillus Cyclic Lipopeptides and Their Role in the Host Adaptive Response to Changes in Environmental Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi, M.; Baserh, J.; Abnaroodhelleh, F.; Kordyani, M.B.; Samani, M.N.; Dadar, M. Combined Prebiotic and Multivitamin Supplementation Enhances Growth, Survival, and Disease Resistance of Asian Seabass in Floating Cages. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 43, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoseinifar, S.H.; Ashouri, G.; Marisaldi, L.; Candelma, M.; Basili, D.; Zimbelli, A.; Notarstefano, V.; Salvini, L.; Randazzo, B.; Zarantoniello, M.; et al. Reducing the Use of Antibiotics in European Aquaculture with Vaccines, Functional Feed Additives and Optimization of the Gut Microbiota. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botcazon, C.; Bergia, T.; Lecouturier, D.; Dupuis, C.; Rochex, A.; Acket, S.; Nicot, P.; Leclère, V.; Sarazin, C.; Rippa, S. Rhamnolipids and Fengycins, Very Promising Amphiphilic Antifungal Compounds from Bacteria Secretomes, Act on Sclerotiniaceae Fungi through Different Mechanisms. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 977633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Mukherjee, S.; Sen, R. Antimicrobial Potential of a Lipopeptide Biosurfactant Derived from a Marine Bacillus Circulans. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2008, 104, 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, H.-M.; Rong, Y.-J.; Zhao, M.-X.; Song, B.; Chi, Z.-M. Antibacterial Activity of the Lipopetides Produced by Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens M1 against Multidrug-Resistant Vibrio Spp. Isolated from Diseased Marine Animals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.V.; Bose, A.; Keharia, H. Identification and Characterization of Novel Surfactins Produced by Fungal Antagonist B Acillus Amyloliquefaciens 6 B. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2014, 61, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wangjiang, T.; Sun, Z.; Shi, L.; Chen, S.; Chen, L.; Guo, X.; Wu, W.; Xiong, G.; Wang, L. Inhibition Mechanism of Crude Lipopeptide from Bacillus Subtilis against Aeromonas Veronii Growth, Biofilm Formation, and Spoilage of Channel Catfish Flesh. Food Microbiol. 2024, 120, 104489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prathiviraj, R.; Rajeev, R.; Fernandes, H.; Rathna, K.; Lipton, A.N.; Selvin, J.; Kiran, G.S. A Gelatinized Lipopeptide Diet Effectively Modulates Immune Response, Disease Resistance and Gut Microbiome in Penaeus Vannamei Challenged with Vibrio Parahaemolyticus. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2021, 112, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, S.; Oz, F.; Bekhit, A.E.A.; Carne, A.; Agyei, D. Production, Characterization, and Potential Applications of Lipopeptides in Food Systems: A Comprehensive Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2024, 23, e13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, T.T.; Dinh, K.V.; Nguyen, V.D. Biodiversity and Enzyme Activity of Marine Fungi with 28 New Records from the Tropical Coastal Ecosystems in Vietnam. Mycobiology 2021, 49, 559–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Zhang, Z.; Guo, L. Antibacterial Molecules from Marine Microorganisms against Aquatic Pathogens: A Concise Review. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, A.-D.; Li, H.-P.; Yuan, Q.-S.; Song, X.-S.; Yao, W.; He, W.-J.; Zhang, J.-B.; Liao, Y.-C. Antagonistic Mechanism of Iturin A and Plipastatin A from Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens S76-3 from Wheat Spikes against Fusarium Graminearum. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanis, P.; Kiernan, M.; Muldoon, J.; Doyle, F.; Evans, P.; Murphy, C.D.; Rubini, M. Novel Synthesis of the Antifungal Cyclic Lipopeptide Iturin A and Its Fluorinated Analog for Structure-Activity Relationship Studies. Chem. A Eur. J. 2025, 31, e01341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Ma, M.; Huang, R.; Qu, Q.; Li, G.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, K.; Lu, K.; Niu, X.; Luo, J. Induction of Chlamydospore Formation in Fusarium by Cyclic Lipopeptide Antibiotics from Bacillus Subtilis C2. J. Chem. Ecol. 2012, 38, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amillano-Cisneros, J.M.; Fuentes-Valencia, M.A.; Leyva-Morales, J.B.; Savín-Amador, M.; Márquez-Pacheco, H.; Bastidas-Bastidas, P.D.J.; Leyva-Camacho, L.; De La Torre-Espinosa, Z.Y.; Badilla-Medina, C.N. Effects of Microorganisms in Fish Aquaculture from a Sustainable Approach: A Review. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englerová, K.; Bedlovičová, Z.; Nemcová, R.; Király, J.; Maďar, M.; Hajdučková, V.; Styková, E.; Mucha, R.; Reiffová, K. Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens—Derived Lipopeptide Biosurfactants Inhibit Biofilm Formation and Expression of Biofilm-Related Genes of Staphylococcus Aureus. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, P.; Borah, P.; Bordoloi, R.; Pegu, A.; Dutta, R.; Baruah, C. Probiotic Bacteria as a Healthy Alternative for Fish and Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. J. Appl. Nat. Sci. 2024, 16, 674–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knipe, H.; Temperton, B.; Lange, A.; Bass, D.; Tyler, C.R. Probiotics and Competitive Exclusion of Pathogens in Shrimp Aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 324–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaddar, N.; Hashemidahaj, M.; Findlay, B.L. Access to High-Impact Mutations Constrains the Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance in Soft Agar. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dussert, E.; Tourret, M.; Dupuis, C.; Noblecourt, A.; Behra-Miellet, J.; Flahaut, C.; Ravallec, R.; Coutte, F. Evaluation of Antiradical and Antioxidant Activities of Lipopeptides Produced by Bacillus Subtilis Strains. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 914713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Qin, Q.; Li, Q.; Yu, Y.; Song, Z.; He, L.; Sun, Y.; Ye, L.; Wang, G.; Xu, J. Molecular Adaptations and Quality Enhancements in a Hybrid (Erythroculter Ilishaeformis ♀ × Ancherythroculter Nigrocauda ♂) Cultured in Saline–Alkali Water. Biology 2025, 14, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marmelo, I.; Dias, M.; Grade, A.; Pousão-Ferreira, P.; Diniz, M.S.; Marques, A.; Maulvault, A.L. Immunomodulatory and Antioxidant Effects of Functional Aquafeeds Biofortified with Whole Laminaria Digitata in Juvenile Gilthead Seabream (Sparus Aurata). Front. Mar. Sci. 2024, 11, 1325244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kong, X.; Zhou, C.; Li, L.; Nie, G.; Li, X. Toll-like Receptor Recognition of Bacteria in Fish: Ligand Specificity and Signal Pathways. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2014, 41, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, X.; Sheng, X.; Xing, J.; Zhan, W. Immune Responses of Flounder Paralichthys Olivaceus Vaccinated by Immersion of Formalin-Inactivated Edwardsiella Tarda Following Hyperosmotic Treatment. Dis. Aquat. Org. 2015, 116, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yi, H.; Su, X.; Wang, R.; Ming, T.; Xu, J. Bacillus Velezensis NDB Mitigates Aeromonas Hydrophila-Induced Enteritis in Black Sea Bream (Acanthopagrus Schlegelii) by Enhancing Intestinal Immunity and Modulating Gut Microbiota. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1660494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, S.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kwon, J.; Lee, S.B.; Park, S.C. Immunomodulatory Role of Microbial Surfactants, with Special Emphasis on Fish. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichner, J.S.; Fitzpatrick, P.A.; Wakshull, E.; Albina, J.E. Receptor-mediated Phagocytosis of Rat Macrophages Is Regulated Differentially for Opsonized Particles and Non-opsonized Particles Containing Β-glucan. Immunology 2001, 104, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ruiz, A.; Gargalianos-Kakolyris, P.; Timerman, A.; Sarma, J.; José González Ramallo, V.; Bouylout, K.; Trostmann, U.; Pathan, R.; Hamed, K. Daptomycin in the Clinical Setting: 8-Year Experience with Gram-Positive Bacterial Infections from the EU-CORESM Registry. Adv. Ther. 2015, 32, 496–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Kong, Y.; Lan, L.; Meng, Y.; You, T.; Pauer, R.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, M.; deMello, A.; et al. A High Efficiency, Low Resistance Antibacterial Filter Formed by Dopamine-Mediated In Situ Deposition of Silver onto Glass Fibers. Small 2024, 20, 2301074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Acosta, M.A.; Castaneda-Aponte, H.M.; Mora-Galvez, L.M.; Gil-Garzon, M.R.; Banda-Magaña, M.P.; Marcellin, E.; Mayolo-Deloisa, K.; Licona-Cassani, C. Comparative Economic Analysis Between Endogenous and Recombinant Production of Hyaluronic Acid. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 680278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scientific Opinion on the Safety and Efficacy of Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens (NCIMB 30229) as a Silage Feed Additive for All Species. EFSA J. 2013, 11, 3042. [CrossRef]

- EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards (BIOHAZ); Allende, A.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Bortolaia, V.; Bover-Cid, S.; De Cesare, A.; Dohmen, W.; Guillier, L.; Jacxsens, L.; Nauta, M.; et al. Update of the List of Qualified Presumption of Safety (QPS) Recommended Microbiological Agents Intentionally Added to Food or Feed as Notified to EFSA 22: Suitability of Taxonomic Units Notified to EFSA until March 2025. EFSA J. 2025, 23, e9510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, W.; Lu, X.; Cao, C.; Sheng, D.; Ren, X.; Jin, N.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Cao, S.; et al. Screening of Antagonistic Bacteria against Three Aquatic Pathogens and Characterization of Lipopeptides in Bacillus Cereus BA09. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Ji, Y.; Xue, P.; Li, Z.; Chen, X.; Shi, J.; Jiang, C. Insights into the Antifungal Mechanism of Bacillus Subtilis Cyclic Lipopeptide Iturin A Mediated by Potassium Ion Channel. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 277, 134306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.-Z.; Zheng, Q.-W.; Wei, T.; Zhang, Z.-Q.; Zhao, C.-F.; Zhong, H.; Xu, Q.-Y.; Lin, J.-F.; Guo, L.-Q. Isolation and Characterization of Fengycins Produced by Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens JFL21 and Its Broad-Spectrum Antimicrobial Potential Against Multidrug-Resistant Foodborne Pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 579621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, W.A.; Mendonça, C.M.N.; Urquiza, A.V.; Marteinsson, V.Þ.; LeBlanc, J.G.; Cotter, P.D.; Villalobos, E.F.; Romero, J.; Oliveira, R.P.S. Use of Probiotic Bacteria and Bacteriocins as an Alternative to Antibiotics in Aquaculture. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, Y.; Hansen, J.; Kotake, M.; Fujii, R.; Matsuoka, H.; Yoshinaga, T. Effect of Biokos, a Natural Lipopeptide Surfactant Extracted from a Bacterium of the Pseudomonas Genus, on Infection of Cryptocaryon irritans. J. Fish Dis. 2023, 46, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Liangliang, H.; Attia, K.A.; Bashir, S.; Ziyuan, X.; Alsubki, R.A.; Rang, J.; Hu, S.; Xia, L. Bacillus Velezensis FiA2 as an Oxydifficidin-Producing Strain and Its Effects on the Growth Performance, Immunity, Intestinal Microbiota, and Resistance to Aeromonas Salmonicida Infection in Carassius Carassius. Probiot. Antimicro. Prot. 2025, 17, 3667–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontinha, F.; Martins, N.; Magalhães, R.; Peres, H.; Oliva-Teles, A. Dietary Lauric Acid Supplementation Positively Affects Growth Performance, Oxidative and Immune Status of European Seabass Juveniles. Fishes 2025, 10, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-S.; Ku, K.-L.; Chu, C.-S.; Chen, K.-L. The Optimal Supplementation of Fermented Product Produced by Bacillus Subtilis Strain LYS1 with High Surfactin Yield for Improving Growth Performance, Intestinal Villi Morphology, and Tibial Bone Strength in Broilers. Animals 2024, 14, 2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Rzeszutek, E.; Van Der Voort, M.; Wu, C.-H.; Thoen, E.; Skaar, I.; Bulone, V.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; De Bruijn, I. Diversity of Aquatic Pseudomonas Species and Their Activity against the Fish Pathogenic Oomycete Saprolegnia. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschuere, L.; Rombaut, G.; Sorgeloos, P.; Verstraete, W. Probiotic Bacteria as Biological Control Agents in Aquaculture. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 655–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stiller, D.; Ottinger, M.; Leinenkugel, P. Spatio-Temporal Patterns of Coastal Aquaculture Derived from Sentinel-1 Time Series Data and the Full Landsat Archive. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cai, Q.; Ling, J.; Lee, K.; Chen, B. Fish Waste Based Lipopeptide Production and the Potential Application as a Bio-Dispersant for Oil Spill Control. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabar, J.; Babić, I.; Jozić, S.; Trumbić, Ž.; Pioppi, A.; Nielsen, L.J.D.; Maravić, A.; Tomašević, T.; Kovacs, Á.T.; Mladineo, I. Prospecting Microbiota of Adriatic Fish: Bacillus Velezensis as a Potential Probiotic Candidate. Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, T.; Guardiola, F.A.; Almeida, D.; Antunes, A. Aquatic Invertebrate Antimicrobial Peptides in the Fight Against Aquaculture Pathogens. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.D.; Maran, B.A.V.; Iqbal, M.; Ching, F.F.; Lal, M.T.M.; Othman, R.B.; Shapawi, R. Antiparasitic activity of the medicinal plant Dillenia suffruticosa against the marine leech Zeylanicobdella arugamensis (Hirudinea) and its phytochemical composition. Aquac. Res. 2020, 51, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxshall, G.A.; Lin, C.L.; Ho, J.S.; Ohtsuka, S.; Venmathi Maran, B.A.; Justine, J.L. A revision of the family Dissonidae Kurtz, 1924 (Copepoda: Siphonostomatoida). Syst. Parasitol. 2008, 70, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Parameter | Molecular/Technical Characteristics | Significance for Aquaculture | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Structural Diversity of Marine Lipopeptides | ||||

| Fatty Acid Chain Variants | Surfactin CS30-1 | C13 β-hydroxy fatty acid; [M+H]+ m/z 1022.71 | Higher antifungal activity against Magnaporthe grisea (induces ROS generation) | [97] |

| Surfactin CS30-2 | C14 β-hydroxy fatty acid; [M+H]+ m/z 1036.72 | Lower bioactivity than CS30-1 despite similar mechanism | [97] | |

| Pumilacidin Homologs | CLP-1 (Bacillus sp. 176) | C57H101N7O13; targets flagellar genes (flgA, flgP) in Vibrio alginolyticus | Suppresses motility & biofilm formation without cell death | [99] |

| CLP-2 (Bacillus sp. 176) | C58H103N7O13; differs by -CH2 group from CLP-1 | Reduces pathogen adherence by 70% | [99] | |

| II. Antibiotic Use and Environmental Persistence | ||||

| Global Antibiotic Regulation | Vietnam | 30 authorized antibiotics (e.g., danofloxacin, sulfadiazine) | High regulatory complexity; favors resistance development | [103] |

| Brazil | Only 2 authorized (florfenicol, oxytetracycline) | Strict control reduces resistance risks | [103] | |

| III. Lipopeptide Delivery Innovations | ||||

| Nano-Encapsulation | Chitosan Nanoparticles | Enhances surfactin stability in seawater by 40%; sustained release >72 h | Prevents rapid dilution in open-sea cages | [104] |

| Surface Functionalization | Dopamine-AMP Coatings | Antibacterial peptides bound to 304 SS/nylon; inhibit S. aureus biofilms by 88.68% | Anti-fouling for cage nets; reduces pathogen colonization | [104] |

| V. Economic & Regulatory Landscape | ||||

| Production Costs | Surfactin Purification | Yield recovery: 3–9% after HPLC; USD 120–150/kg production cost | Scalability barrier for commercial use | [104] |

| EU Regulatory Status | Lipopeptide Biosurfactants | Classified as “Advanced Bioagents” under EC No 1107/2009 | Fast-track approval for aquaculture biologics | [107] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kumar, S.; Kumar, A.; Soratur, A.; Sarkar, A.; Venmathi Maran, B.A. Harnessing Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides for Sustainable Disease Management in Open Sea Cage Aquaculture. Oceans 2026, 7, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans7010004

Kumar S, Kumar A, Soratur A, Sarkar A, Venmathi Maran BA. Harnessing Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides for Sustainable Disease Management in Open Sea Cage Aquaculture. Oceans. 2026; 7(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans7010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleKumar, Sumit, Ajit Kumar, Akshatha Soratur, Ankit Sarkar, and Balu Alagar Venmathi Maran. 2026. "Harnessing Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides for Sustainable Disease Management in Open Sea Cage Aquaculture" Oceans 7, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans7010004

APA StyleKumar, S., Kumar, A., Soratur, A., Sarkar, A., & Venmathi Maran, B. A. (2026). Harnessing Marine Bacterial Lipopeptides for Sustainable Disease Management in Open Sea Cage Aquaculture. Oceans, 7(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans7010004