1. Introduction

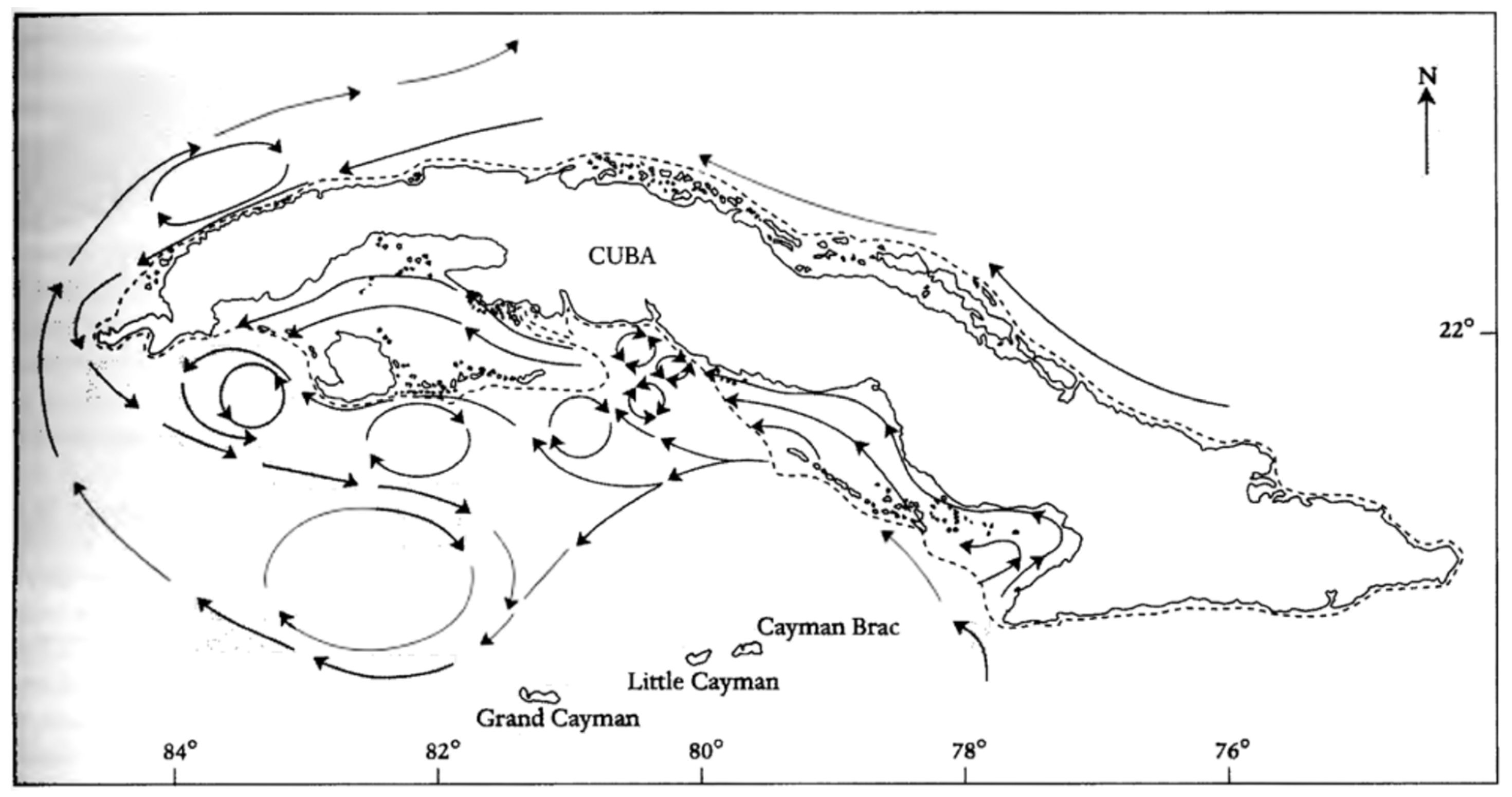

The island of Cuba occupies a central location in the Intra-Americas Sea (IAS hereafter; see

Figure 1), the large marginal sea between north and south America formed by the Gulf of Mexico (GoM), and the Caribbean Sea (CS). Cuba belongs to a complex system of islands that separates the CS from the Atlantic Ocean and is surrounded by passages (the Yucatan Channel, the Florida Channel, the Windward Passage) that play an important role in the IAS circulation. Here we seek to obtain new insight into large-scale marine dynamics around Cuba, particularly in places, such as the eastern and southern sides of the island, where the structure and variability of the circulation is poorly known.

The currents, whose existence has been known for a long time (e.g., [

1], and the review by Schmitz [

2]), form an anticyclonic loop throughout the IAS that includes the Caribbean Current, the Yucatan Current, the Loop Current, and the Florida Current. The latter feeds the Gulf Stream, a strong, warm current that influences the climate of the eastern coast of the United States and of northwest Europe.

Variability of these currents is still actively investigated. For example, to characterize the instabilities of the Loop Current (e.g., [

3], and references therein) on the Mexican side [

4,

5] and those on the Cuban side [

6], which may affect the circulation along the north-western coasts of Cuba. Recent studies of the circulation on the Cuban side [

7,

8] were also prompted by the DeepWater Horizon accident in 2010, which raised attention on the pathways of oil spills in the GoM that could interest the Cuban Exclusive Economic Zone, with impacts on the local ecosystems. In this work, however, we will not discuss the complex nonlinear dynamics occurring in this area.

Atlantic waters enter the CS at its eastern boundary, through the many passages between islands, and leave the IAS through the Florida Channel. In the classical work by Johns at al. [

9], a total average inflow of about 28 Sv was estimated, using new observations, particularly concerning the inflow from the east, through the Lesser Antilles chain. More recent estimates by Candela et al. [

10], based on four years of measurements (September 2012 to August 2016), show similar transport figures for the flow that enters the GoM and exits from the Florida Channel.

It was also noted in [

9] that the mean transport through the Greater Antilles, and particularly the Windward Passage (WP), between Cuba and Hispaniola, was poorly constrained by the direct observations and could only be indirectly estimated. This motivated a US observation campaign in the area (October 2003–February 2005), whose results are detailed in a report by Johns [

11] and a thesis work by Smith [

12]. However, the results of the campaign were not conclusive, since the high variability observed in the four surveys performed would not allow for the definition of a robust local mean flow state through the passage. To our knowledge, this is an aspect of the local dynamics that has not yet been clarified.

The lack of a detailed description of the circulation around Cuba appears related to the limited number of available “modern” in situ observations. A schematic based on old works (Claro et al. [

13]), displayed in

Figure 2, indicates the presence of a westward flow along the northern coasts, in the central part of the island, and of complex circulation patterns in the southwestern waters, but provides no indication about the structure of the average flow around the eastern side of the island.

Surface circulation maps of the CS based on velocity observations from near-surface drifters (1996–2001), constructed by Centurioni and Niiler [

14], give little information about the circulation in the waters along the coastal areas of Cuba, which were reached by few drifters. The very limited number of trajectories between Cuba and Hispaniola would not allow to compute a statistically significant mean circulation for the WP region.

The picture can be improved using remote observations from satellites, which have strongly developed in recent decades. In this work, we show that a new, high-resolution gridded sea height dataset provided by the Copernicus Marine Service (CMEMS;

https://marine.copernicus.eu, accessed on 4 February 2025), with the associated geostrophic reconstruction of the circulation, allow for a novel, robust assessment of the structure of the large-scale geostrophic circulation around Cuba and of its variability. Such an assessment is a necessary preliminary step for the development of numerical models of the circulation in coastal areas, which could be of use in a variety of applications, such as the evaluation of the energy potential residing in the currents, the individuation of the possible dispersion paths of pollutants, and the construction of the physical inputs needed by coastal biogeochemical models.

The paper is organized as follows. Altimeter data and related quantities used in this work are described in

Section 2. Data are analyzed in

Section 3, with the purpose of obtaining new information on the geostrophic circulation in the WP area and along the southern coasts of Cuba. Sea level variability to the south of Cuba is also briefly investigated. Results are further discussed in

Section 4, to highlight progress with respect to previous knowledge, and point out limitations as well as possible future developments. Finally,

Section 5 provides a short summary of the main findings.

2. Material and Methods

We use products derived from altimeter satellite data that are freely available through CMEMS (Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service, Toulouse, France); in particular, gridded, delayed-time Sea Level Anomalies (SLA) computed with respect to a twenty-year (1993–2012) mean. This is the product SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_L4_MY_008_047, which covers the global ocean with a spatial resolution of 0.125° × 0.125°. Daily maps of SLA and of related quantities (Absolute Dynamic Topography, or ADT; geostrophic velocities) are provided, for the period 1 January 1993 to 19 November 2024, obtained by postprocessing (optimal interpolation) of the L3 along-track measurements from the available altimeter missions (1993 is the year that marked the beginning of systematic altimetric observations of the world’s oceans from satellites). The ADT is the sum of the SLA and of the Mean Dynamic Topography (MDT; product SEALEVEL_GLO_PHY_MDT_008_063 of the Copernicus repository), which accounts for the deformation of the geoid induced by the average ocean circulation.

The products mentioned result from a recent major upgrade that has allowed to double the spatial detail, taking advantage of the increasing number of satellite missions. The resolution of the new datasets (1/8°, or about 13.5 km) is sufficient to resolve large mesoscale features. Data are provided as NetCDF-4 files (Unidata/UCAR, Boulder, CO, USA) that are periodically updated; detailed information on the products’ quality and validation can be found in the descriptions and quality reports that are attached to any CMEMS product and can be consulted and downloaded online in the CMEMS portal.

Plots of the maps and of time series of quantities of interest extracted from the altimeter data have been realized using the Interactive Data Language (IDL) software (Version 8.9, L3Harris Geospatial Solutions, Inc., Boulder, CO, USA); this includes the computation of power spectra of the ADT, performed with the IDL routine FFT_POWERSPECTRUM.

3. Results

Here we present results deriving from the analysis of MDT and SLA data.

Section 3.1 describes the geostrophic circulation associated with the MDT, whereas the two following subsections discuss the geostrophic circulation derived from altimeter data, in the regions on which our study focuses, namely, those around the WP and to the southwest of Cuba. In the last part of the section, we briefly discuss the time variability of the sea level in the Caribbean area, because sea level rise (SLR) due to climate warming is a cause of concern for the populations of small islands in the tropics, such as those in the Caribbean.

3.1. The Mean Circulation Around Cuba as Resulting from the MDT

A map of the MDT in the area around Cuba, with the corresponding geostrophic velocity field superimposed, is displayed in

Figure 3. As expected, strong currents are present on the western side of the map. To the south, the Yucatan Current enters the GoM to form the Loop Current. The latter exits the Gulf to the south of the Florida Peninsula, giving rise to the Florida Current. Other currents, such as that present along the northern coast of Cuba, approximately between 78° W and 76 °W, are weaker, and the remaining velocity field is dominated by vortices with sizes going from less than 100 km to about 200 km. To the southwest of Cuba, there is a large anticyclonic structure, nested in the sharp bend that the Yucatan Current makes before entering the GoM.

An interesting feature of the MDT map is the cyclonic vortex just to the south of the WP (red box) that, to the best of our knowledge, has not been discussed in previous works. Due to its presence, Atlantic waters entering the CS through the western side of the WP appear to recirculate cyclonically and to exit from the other side of the passage. However, this behavior seems at odd with the results indicating a large transport though the WP and suggests that further investigation of the local dynamics is in order.

3.2. The Circulation in the WP Area and Its Variability: Insights from Altimeter Data

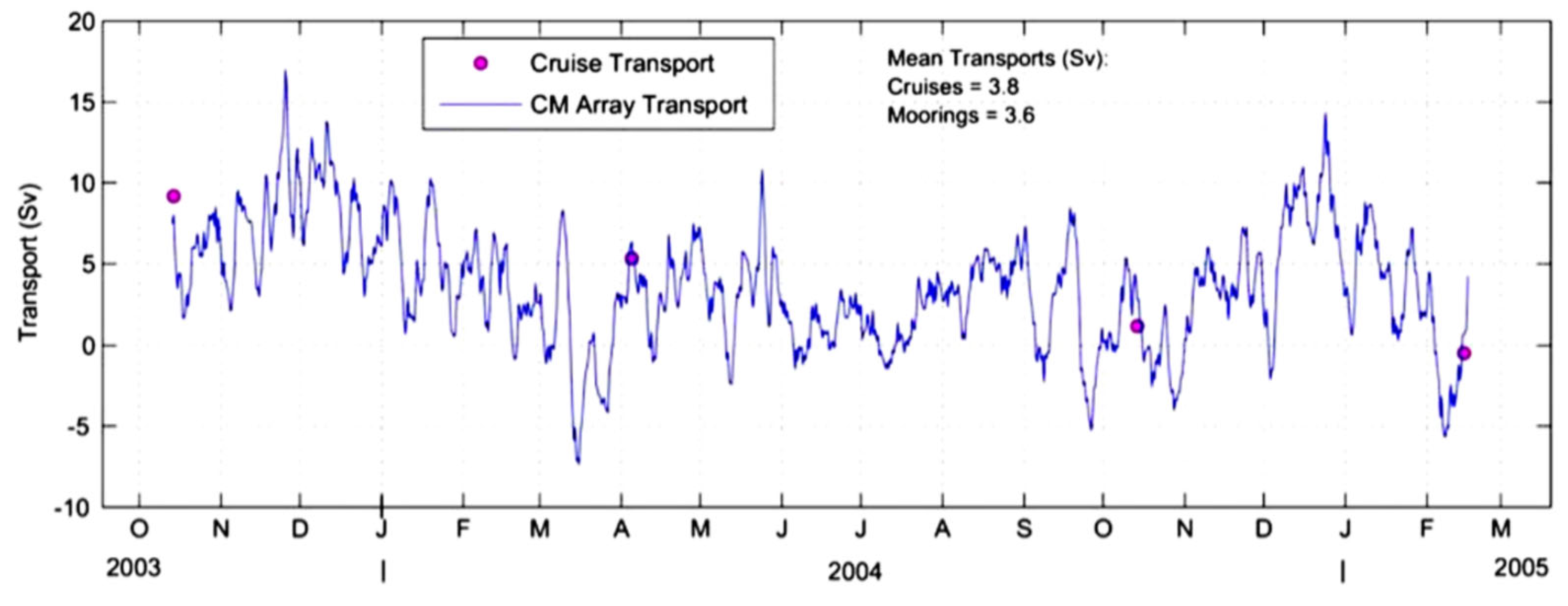

The circulation in the WP area was studied during four cruises (October 2003, April 2004, October 2004, and February 2005) jointly realized by the University of Miami and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). In addition, an array of five moorings equipped with current meters and ADCPs was used to continuously monitor the transport throughout the WP from October 2003 to February 2005. Johns [

11] noted that, despite the high variability of the observed transport values, the vertical structure of the flow through the passage was quite robust, with a net inflow to the CS in the first 600 m of the water column, a net outflow between 700 and 1200 m, and a smaller, deep inflow near the bottom, which is at 1680 m of depth. Johns’ [

11] time series of the net transport is reported in

Figure 4; it shows variability on several time scales, but this was not commented upon.

We note that the time series suggests the possible presence of a seasonal component, since relative maxima of transport were attained in autumn, both in 2003 and 2004, whereas lower transport values were observed during spring-summer of 2004.

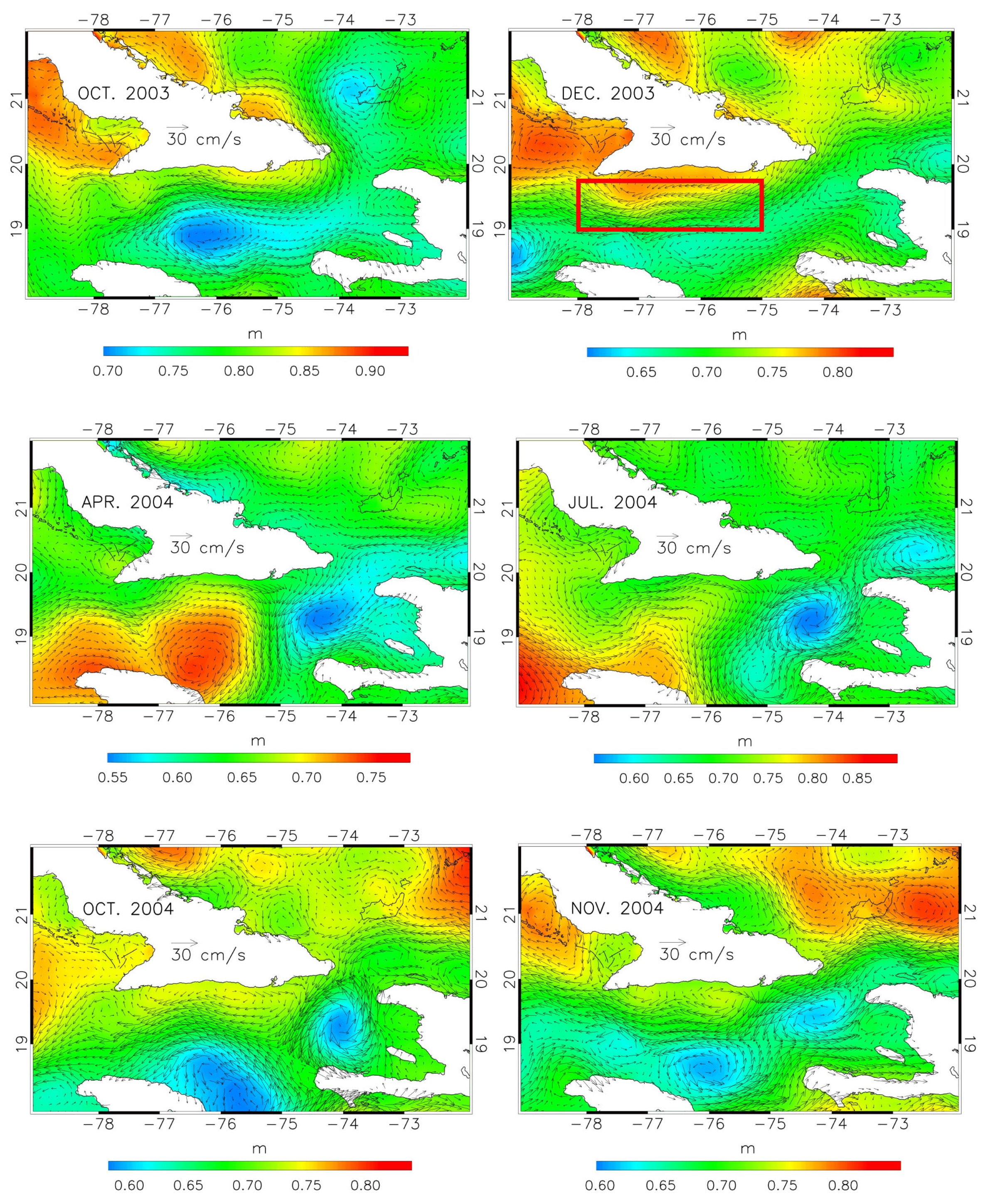

To track the reasons for such behavior, we have looked at the structure of the monthly ADT during the 17 months of the campaign. Six ADT maps in this period are shown in

Figure 5, with the corresponding geostrophic circulations superimposed. Two of them are relative to months (October 2003 and April 2004) in which hydrographic (CTD/LADCP) and shipboard ADCP surveys were conducted in the WP and surrounding regions.

Figure 5 shows robust currents entering from the western side of the WP during the autumns of 2003 and of 2004, which progress westward, between Cuba and Jamaica. In these seasons, the cyclone to the south of the WP highlighted in the discussion of the MDT tends to be weaker and is sometimes absent. On the other hand, the maps of April and July 2004 show the presence of a “blocked” pattern, in which a wide cyclonic circulation is present just to the south of the passage, with an adjacent anticyclone to the west, and little flow appears to enter the Caribbean. This is in good qualitative agreement with the transport time series of

Figure 4 and suggests that the net inflow in the first 600 m may be strongly modulated by the variability of the cyclonic structure near the passage.

It should be noted that the velocity measurements in the surface and subsurface layers (approximately the first 250 m of the water column, see Schott et al. [

15]) made in the October 2003 and April 2004 cruises in the WP area and more to the south ([

12], Figure 19a,b,e,f) indicate a structure of the flow that is consistent with the geostrophic reconstructions in the corresponding panels of

Figure 5. In the October 2003 measurements, the presence of a robust westward stream to the south of Cuba is also evident in the Central Water layer, which goes down to 600–700 m ([

12], Figure 19c).

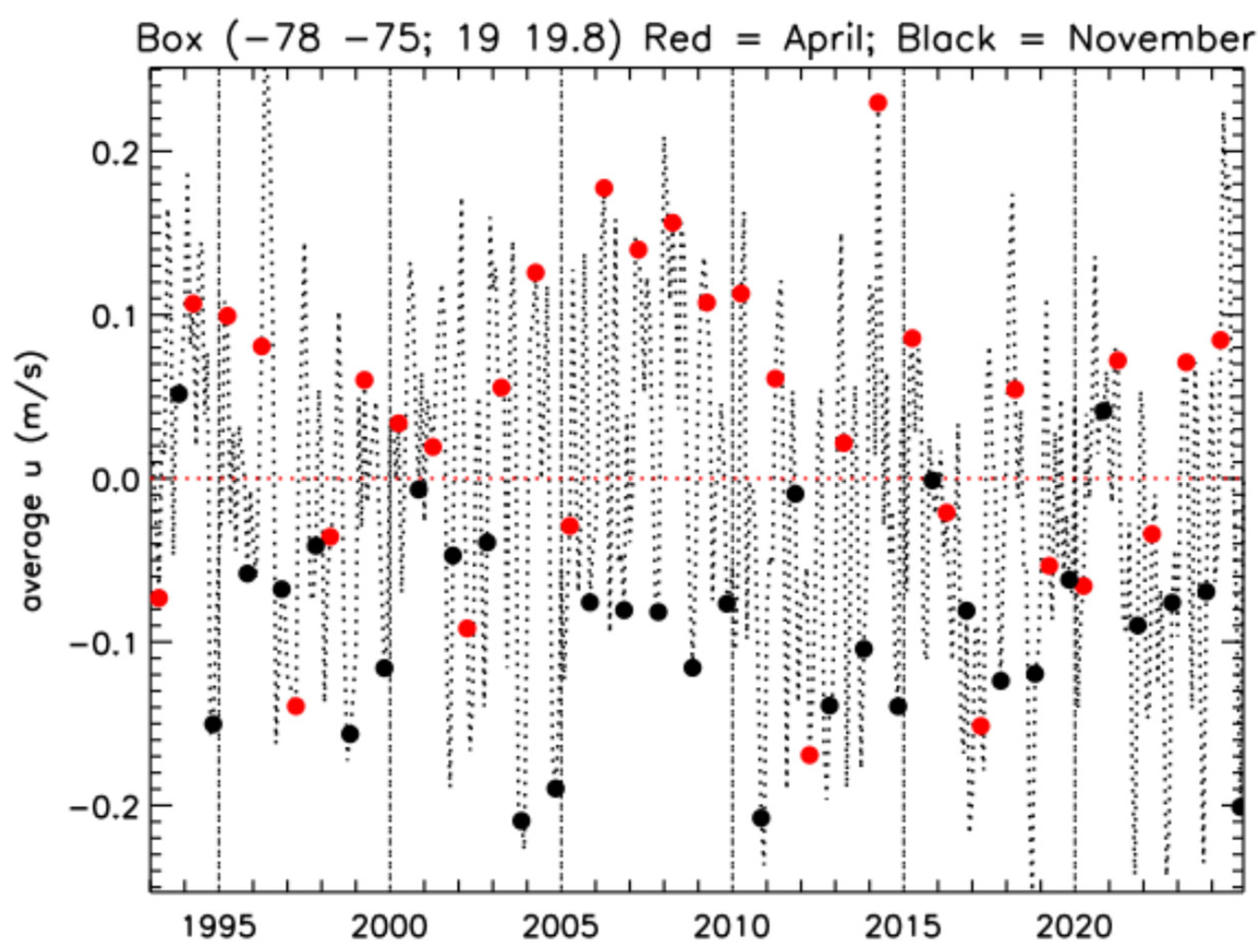

To understand whether the behavior observed during the campaign is typical, we have looked at the monthly time series of the longitudinal component of the geostrophic velocity, which is displayed in

Figure 6. The velocity values are averaged over the region (78°–75° W, 19°–19.8° N), which is marked by a red box in the December 2023 ADT map of

Figure 5. This is a region in which predominantly westward flow was found to be present in the autumns of 2003 and 2004, due to the inflow of a stream of Atlantic water occurring on the western side of the WP.

In

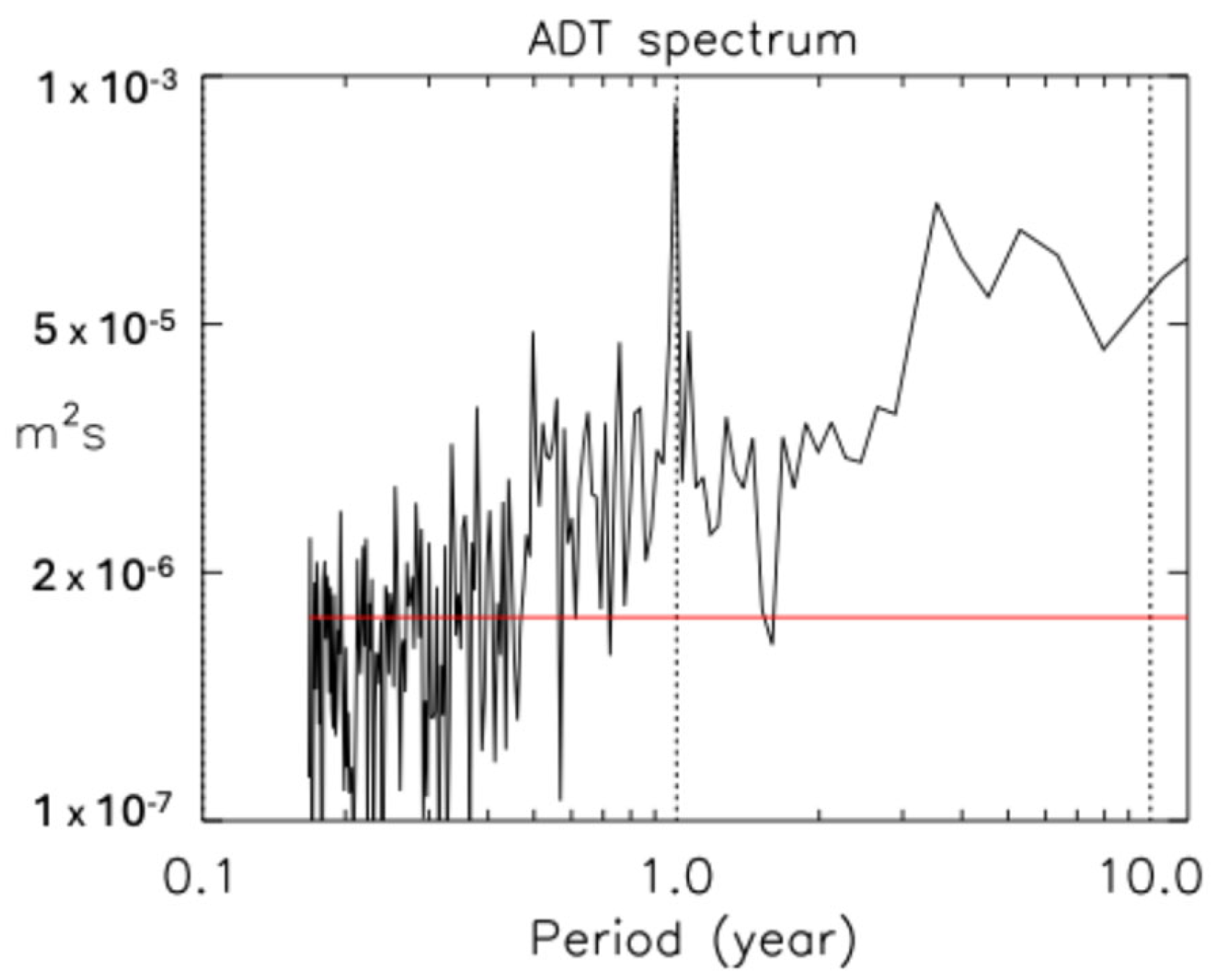

Figure 6, we have highlighted the April (red filled circles) and November (black filled circles) values throughout the whole period. They are well separated, with almost all the black circles lying on the negative u side (westward flow), and about two thirds of the red ones on the positive u side. This indicates the presence of a recurrent seasonal variation in the local dynamics, with significant inflow from the WP that only occurs during the autumn months. In fact, a sharp seasonal component is the dominant signal in the Fourier power spectrum of

Figure 7, computed from the time series of the ADT averaged over the same box used to draw

Figure 6.

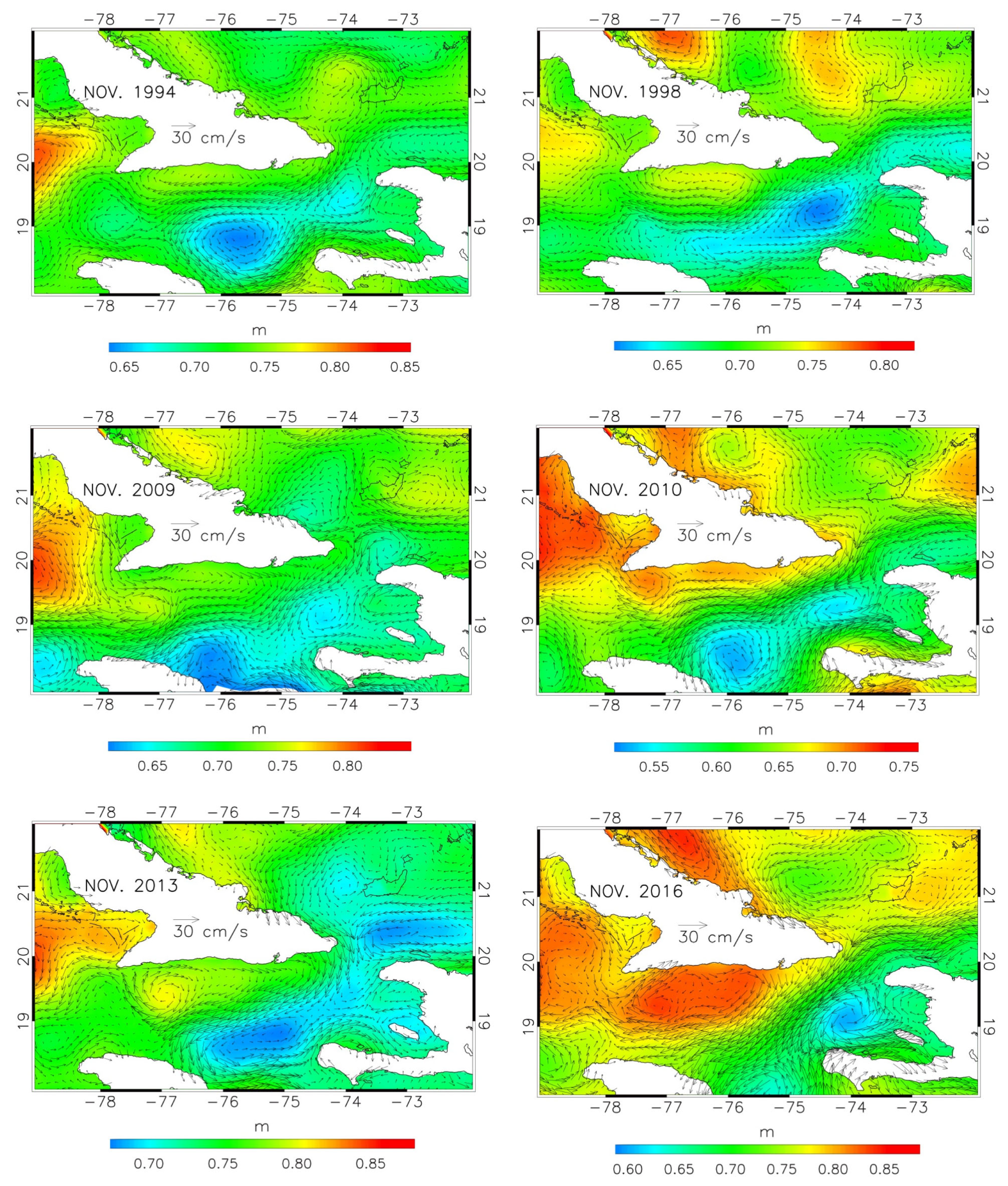

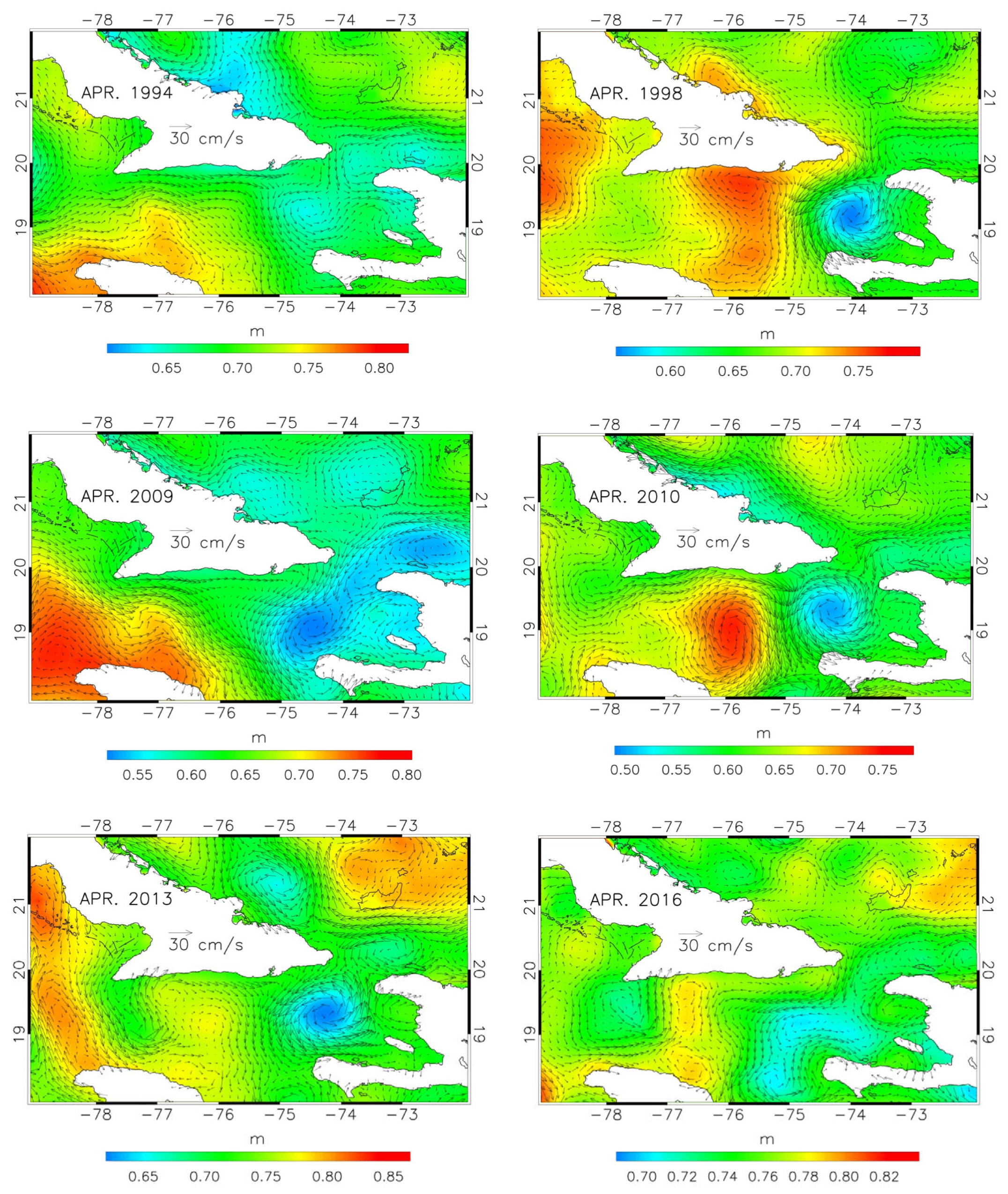

Further support to this conclusion comes from

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, showing November and April ADT maps, respectively, for six years along the dataset span (1994, 1998, 2009, 2010, 2013, 2016). The November geostrophic circulations are characterized by the ingression of Atlantic water from the western side of the WP, as seen in the October and December maps of

Figure 5, whereas the April maps show blocked situations similar to those observed in April and July 2004.

To clarify the causes of the different behaviors in spring and autumn, in

Figure 10 we plot SLA maps for April and November 2004, covering the same region of the ADT maps of

Figure 5. The range of variation in the ADT in the WP area is about 10 cm, and the range of the MDT (see

Figure 3) is similar. In April, the structure of the SLA resembles that of the MDT, and their sum yields the blocked situation shown in the ADT map of 2004 (

Figure 5) and in those of

Figure 9, with little flow entering the CS. On the other hand, the November SLA is very different from the MDT and is characterized by a strong westward flow entering from the WP. The weakly varying MDT field between Cuba and Jamaica does not significantly alter this stream, which is evident in the October 2003 and November 2004 ADT maps of

Figure 5.

3.3. The Circulation to the Southwest of Cuba

Besides the WP, another region of interest is that to the southwest of Cuba. The old schematics in

Figure 2 suggest that this region hosts a complex circulation characterized by anticyclonic and cyclonic eddies of different sizes.

Figure 11 shows average (1993–2024) ADT maps for this region, for the different seasons, with the corresponding geostrophic circulations superimposed.

The summer map is very close to the spring one, except for showing slightly higher values of the ADT. In all maps, there are two large anticyclones centered around 85° W and 83° W, and approximately 20° N, and a third, smaller one, to the south-southeast of the Large Cayman Island, which is stronger in spring and summer. The three vortices are nested in the bend formed by the Yucatan Current when approaching the GoM. In spring and summer, the three anticyclones appear to be embedded in a large anticyclonic cell that goes from 86° W to 80° W. To the north of this cell, there is a prevalence of cyclonic eddies of smaller sizes; one of these cyclones, to the east of 84° W and to the north of 21° N, is present in all seasons, even if with some variability, and corresponds to a feature appearing in the schematics of

Figure 2.

We finally note that in autumn the anticyclonic cell is weaker and of a different form, and the circulation to the east of the Small Caymans is different from the spring–summer one, with a westward stream entering from the eastern boundary that appears to feed the southern branch of the cell.

3.4. Sea Level Time Variability

Recent works by Ibrahim and Sun [

16] and Maitland et al. [

17] have highlighted a change in the SLR trend in the CS, which appears to have accelerated after 2004. In [

17], where the period 1993–2019 was examined, this change was attributed to a shift in the controlling mechanisms, with the halosteric contribution becoming stronger after 2004, because of the effects of the melting of remote ice sheets and glaciers. Here we reconsider these results, in the light of the longer altimeter dataset now available, looking in more detail at the seas surrounding Cuba.

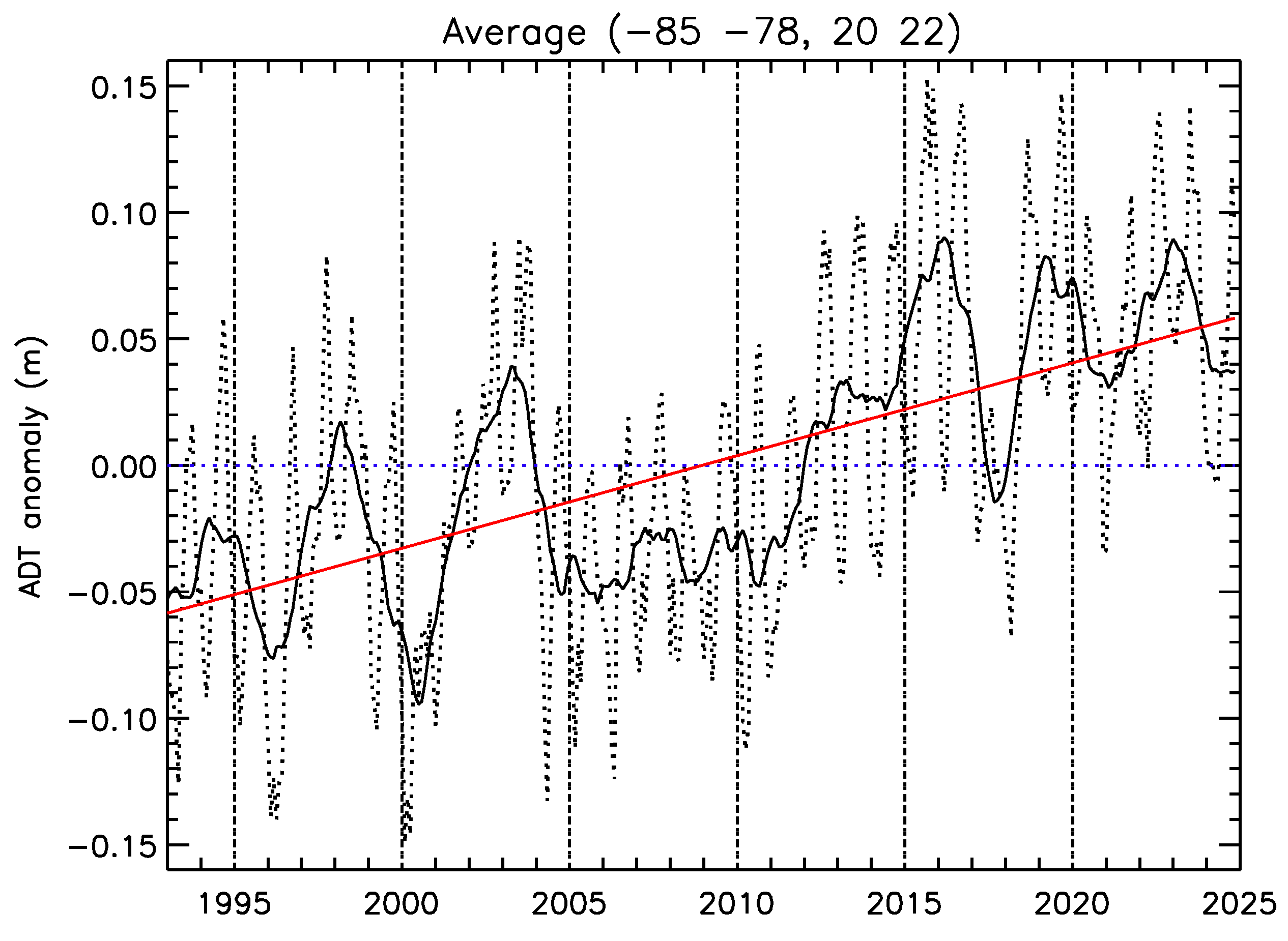

Figure 12 shows the monthly time series of the ADT anomaly (dotted curve), averaged over the box (85–78° W, 20–22° N), to the south of Cuba, a region in which the bathymetry becomes quite shallow well before reaching the coast.

The solid black curve superimposed is obtained by applying a 12-month running mean to filter out the seasonal cycle, whereas the red line is a linear fit computed from the monthly time series. The fit yields an increasing trend of about 3.7 mm/year over the whole period, which is not far from the 3.4 mm/year quoted in [

17] for the period 1993–2019. Maitland et al. [

17] also noted that a linear regression for the period 2004–2019 would give a much higher, worrying trend, of about 6.15 mm/year. However, the apparent acceleration of the trend has been reabsorbed in the last decade, yielding a trend over the whole period (1993–2024) that is in line with that of the global ocean (Fox-Kemper et al. [

18]).

Note that the filtered signal in

Figure 12 shows the presence of strong interannual oscillations, with a period of about 4 years, until 2005, in agreement with Alvera-Azcarate et al. [

3], who found a peak at about 4.5 years in the spectrum of the average ADT over the CS. After 2005, the signal becomes more irregular, with smaller variability, and large oscillations reappear in the last part of the series, but with slightly shorter periods.

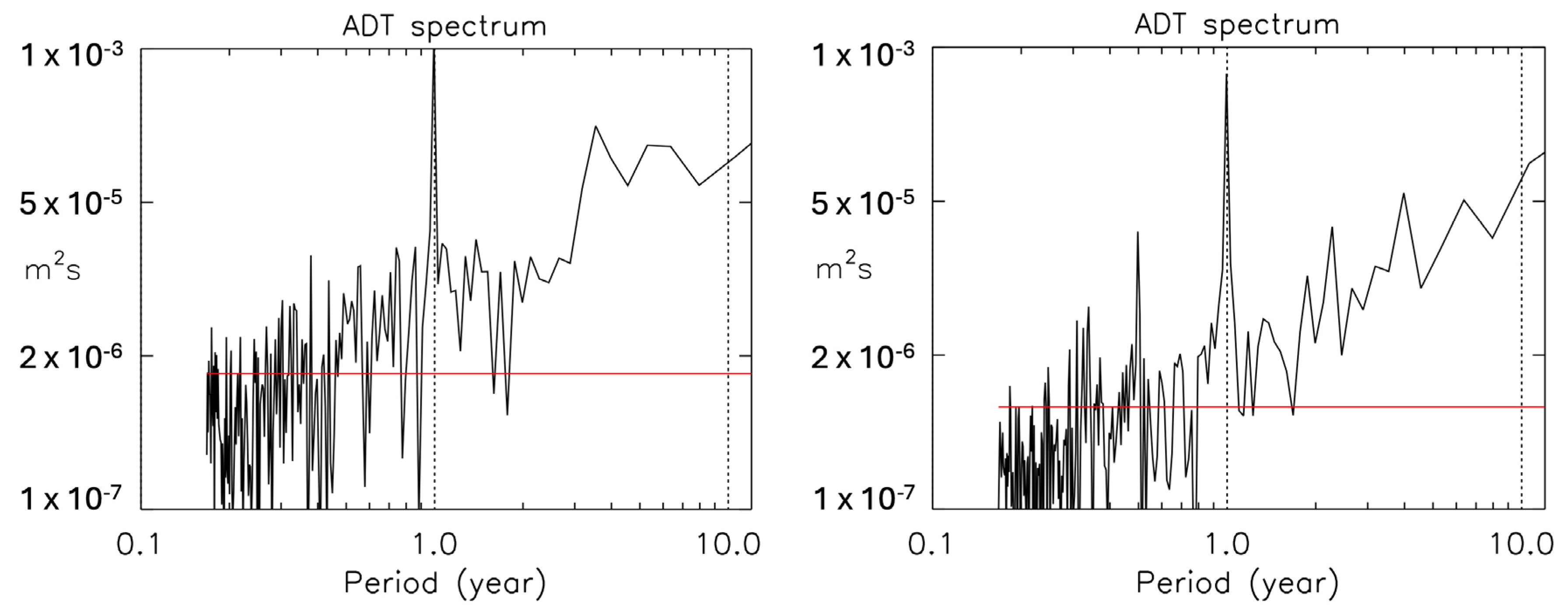

The ADT power spectrum for the box used in

Figure 12 is shown in the left panel of

Figure 13. The panel on the right instead is for the ADT averaged over a large box more to the south that includes all the CS below 18° N (84°–61° W, 10°–18° N). The spectra resemble each other, with the seasonal signal standing out in both, but there are some differences. For example, there is a sharp 6-month period peak in the spectrum over the southern Caribbean that is not as clearly defined in the spectrum on the left. The interannual components are also somewhat different; the spectrum on the right contains a series of sharp peaks with periods of about 2, 4, and 6 years, typical of atmospheric variability, which are less well-defined in the spectrum relative to the southwestern Cuban waters.

The spectrum on the right can be compared to that shown in

Figure 4 of [

3], where the variability of the sea surface height (SSH) in the Caribbean was analyzed using remotely sensed SLA data at 1/3° of resolution, combined with a mean SSH derived from a run of the Miami Isopycnic Coordinate Ocean Model (MICOM; Chassignet and Garraffo [

19]), at 1/12° resolution. Some interesting modes of variability were highlighted: a seasonal component attributed to a seasonal steric effect, shorter term components in part related to westward eddy propagation, and an interannual component with a frequency of about 4.5 years, apparently related to the wind forcing over the area. However, since the SLA dataset available at that time was relatively short (1993–2006), it is interesting to compare with the spectrum in the right panel of

Figure 13. In the latter, the semiannual component is much sharper and seems difficult to explain in terms of eddy propagation, since during the period considered, about 4.3 eddies per year were observed to propagate from the Lesser Antilles to the Nicaraguan Rise (about 4.6 events per year were reported in previous work by Pratt and Maul [

20]). On the other end of the spectrum, as already noted, instead of the single peak highlighted in [

3], we have a series of peaks with periods ranging from 2 to 7 years, which are typical of atmospheric variability over the region.

4. Discussion

Analysis of a dataset of SSH from satellite altimeters recently released by CMEMS, which covers the global ocean with a horizontal spatial resolution of 1/8°, has allowed us to unveil some features of the ocean dynamics around Cuba not previously highlighted. Perhaps the most interesting finding is the strong seasonality of the geostrophic circulation around the WP, which is related to the presence of a cyclone just to the south of the passage. Through most of the year, this leads to a blocked situation in which the cyclone, together with an anticyclone to the west, hinders the Atlantic inflow. The block is removed in autumn, when a robust stream of Atlantic water crosses the western side of the passage, penetrating deeply into the northern part of the CS. Supporting this picture, we have shown that during the few years (2003–2005) in which experimental campaigns were made in the region, the geostrophic reconstructions of the circulation from altimeter data are consistent with the in situ observations.

Here a comment about the role of the MDT is in order. Since the construction of the MDT is a delicate matter involving sea level measurements from satellites, other observations, and numerical simulations [

21,

22], any independent proof of its reliability is welcome. In this respect, the fact that the ADT fields in October 2003 and April 2004 are consistent with the in situ observations reported in Smith [

12] gives us confidence about the reliability of the underlying MDT reconstruction in the area.

Further analysis will be needed to understand what modulates the variability in the WP area. We note that the spring and autumn circulations to the north of the passage are also different from each other, and this could be related to the variability of the Atlantic current that flows northwestward along the Greater Antilles (Antilles Current). Another issue that should be explored is how the picture we have drawn would be modified by the inclusion of effects not captured by the geostrophic reconstruction of the circulation, such as effects related to wind forcing. This justifies a word of caution, and suggests that new observations, and/or high resolution, long-term numerical simulations would be needed to fully assess the robustness of the results obtained from the altimeter data. On the other hand, again, the fact that the geostrophic flows in October 2003 and April 2004 (

Figure 5) are consistent with the in situ observations [

12] gives us confidence about the fact the geostrophic reconstruction from altimeter data captures the average dynamics in this area and their variability.

We have also examined the circulation to the southwest of Cuba (to the west of 78° W), which is characterized by three wide anticyclones nested in the bend that the Yucatan Current makes when approaching the GoM, and by smaller vortices of both signs more to the north. We note that the geostrophic reconstruction offshore is quite different from the old schematics of

Figure 2, where a single anticyclone is present to the northwest of Grand Cayman. The structure of the geostrophic circulation is very close in spring and summer, but differs in autumn, when there is evidence of a westward stream entering at 78° W, in the area between Cuba and Jamaica. Details of the reconstruction near the coast must be considered with caution, because SLA data may be affected by accuracy problems in this area; how to improve this remains an open issue in the treatment of altimeter data.

Finally, we have discussed the time variability of the sea level in the CS, compared with the previous literature. We found that an apparent change in the SLR trend after 2004 highlighted in [

17] has been reabsorbed in recent years, yielding an average SLR trend over the last three decades (see

Figure 12) that is in line with the average trend for the global ocean.

Looking at

Figure 12, it is natural to wonder whether the strong interannual variability in the average ADT signal could be associated with the variation in climate indices relevant to the area. It is easily verified that the six major positive anomalies present in Figure (1995, 1997–98, 2003, 2015–16, 2019, 2023–24) closely correspond to positive peaks of the SST anomaly in the Nino3.4 region (e.g.,

https://marine.copernicus.eu/access-data/ocean-monitoring-indicators/nino-34-sea-surface-temperature-time-series-reanalysis, accessed on 2 February 2025). This is consistent with the results of Huang et al. [

23], where a strong relation between the time series of the ADT and of the Nino3.4 index was pointed out, for three sub-basins of the CS, one of which partially overlaps the domain used to produce

Figure 12.

5. Summary

In this work, high resolution altimeter data were used to characterize the large-scale geostrophic circulation around Cuba, in regions near the eastern and southern coasts of the island, where limited in situ observations are available.

The circulation in the WP area was found to exhibit strong seasonality, not previously noted. Analysis of the geostrophic flow associated with the SLA and ADT fields shows that inflow from the Atlantic mainly occurs in autumn, whereas in spring and summer a cyclone–anticyclone couple to the south of the WP hinders the transport towards the CS. This is consistent with the transport measurements performed during the campaign jointly conducted by the University of Miami and NOAA in 2003–2004.

The geostrophic flow to the southwest of Cuba has a complex structure and is quite different from that indicated in the schematics of

Figure 2, based on old observations. Here the dominant feature is a wide anticyclonic region, with multiple poles, nested in the bend that the Yucatan Current makes when approaching the GoM. The shape of this region and the strength of the anticyclones also exhibit seasonal variations.

The SLR trend to the south of Cuba over the last thirty years (3.7 mm/year) was found to be close to that of the global ocean. SLR variations over this period are strongly correlated with those of the Nino3.4 index.