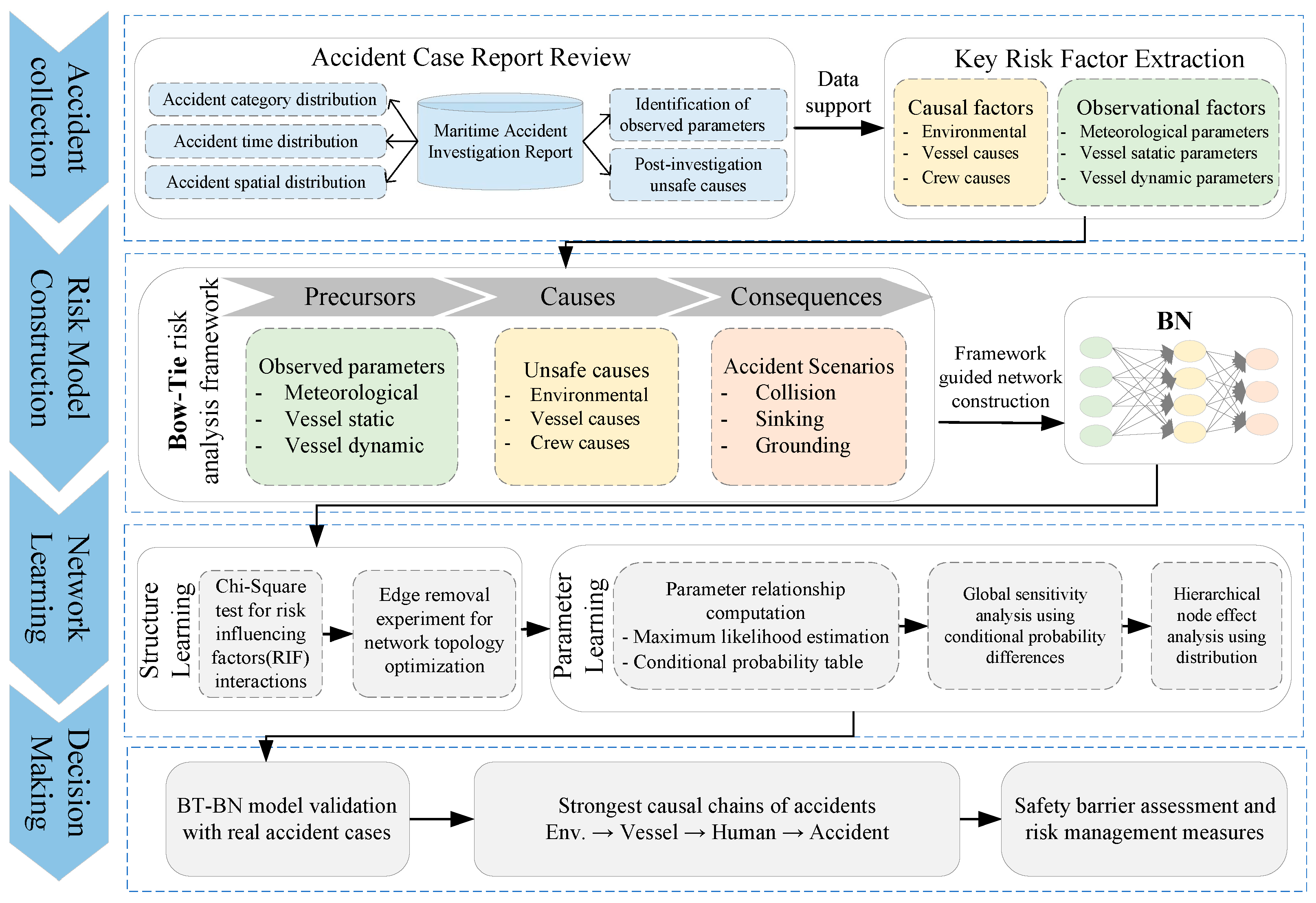

A Bayesian Model Based on the Bow-Tie Causal Framework (BT-BN) for Maritime Accident Risk Analysis: A Case Study of the Bohai Sea

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Study Area and Data

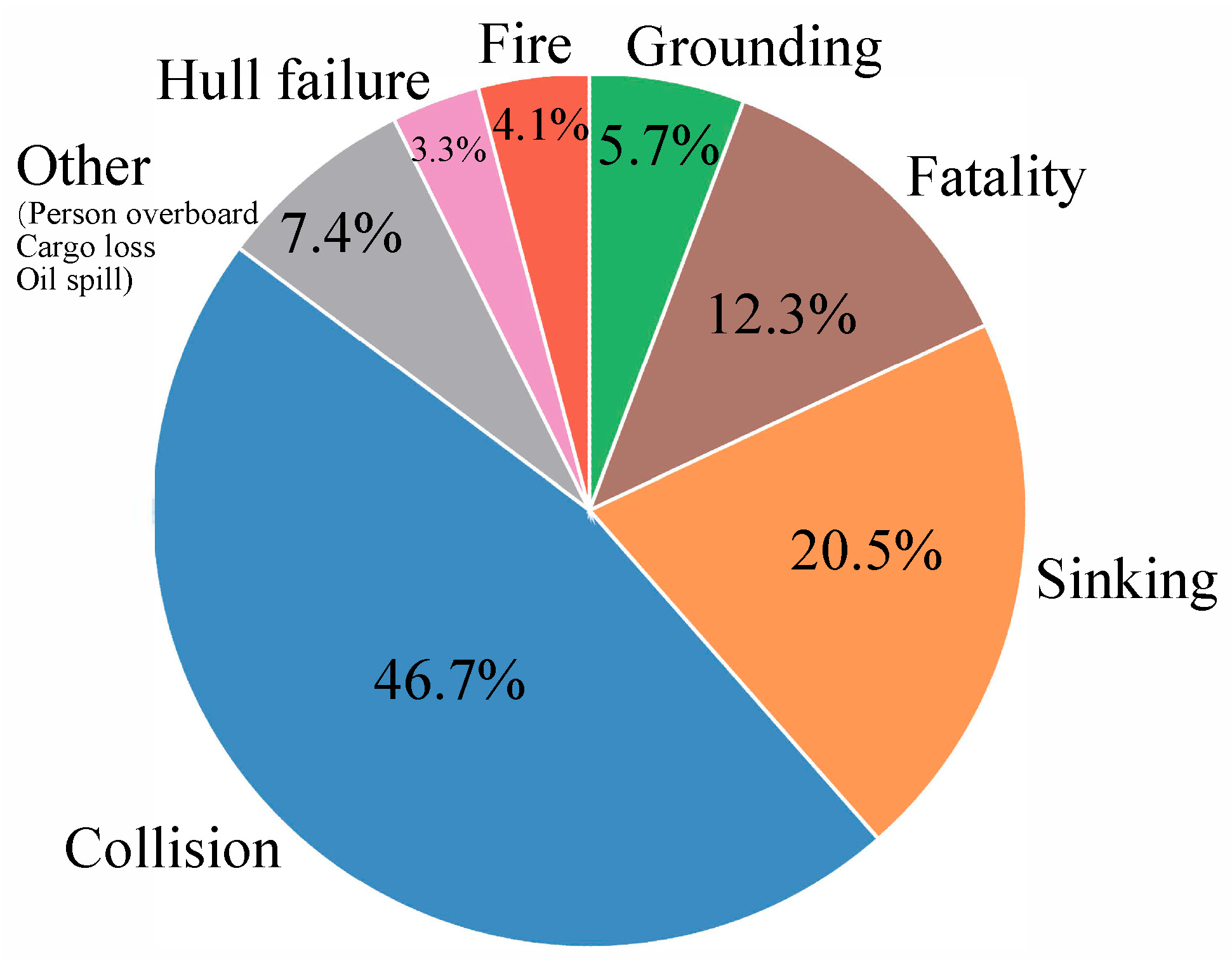

2.1. Distribution Characteristics of Accident Types

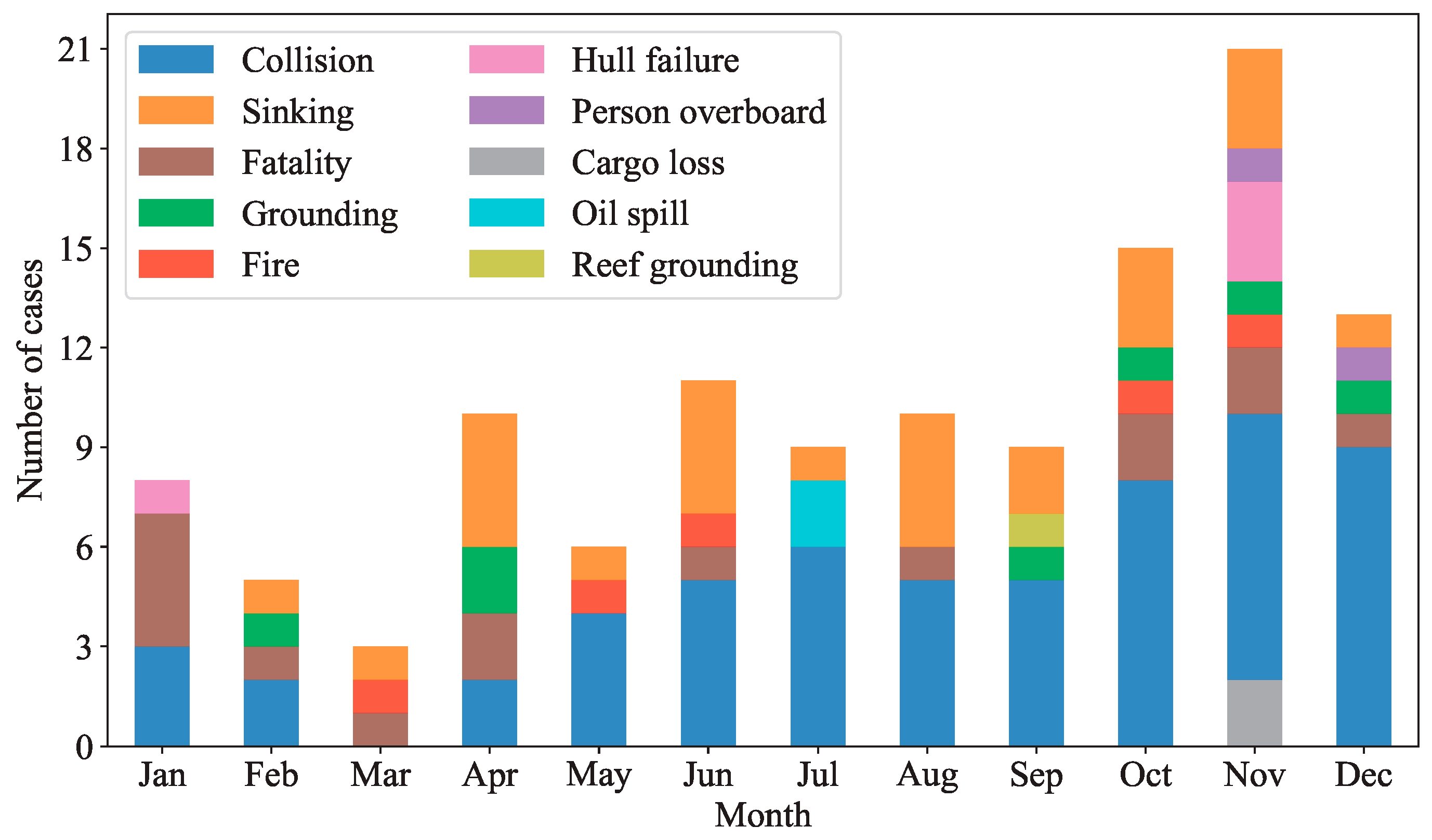

2.2. Distribution Characteristics of Accident Timing

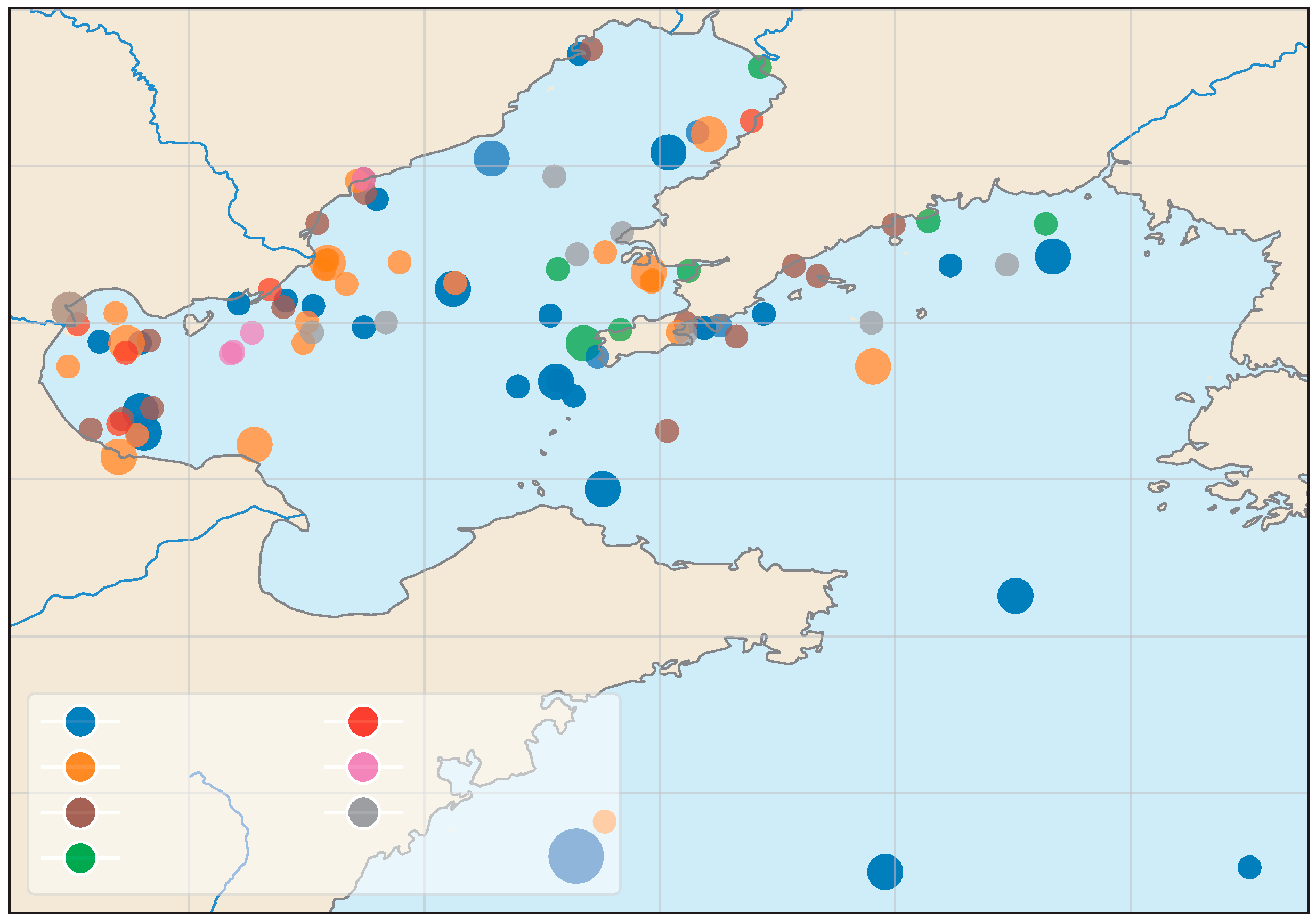

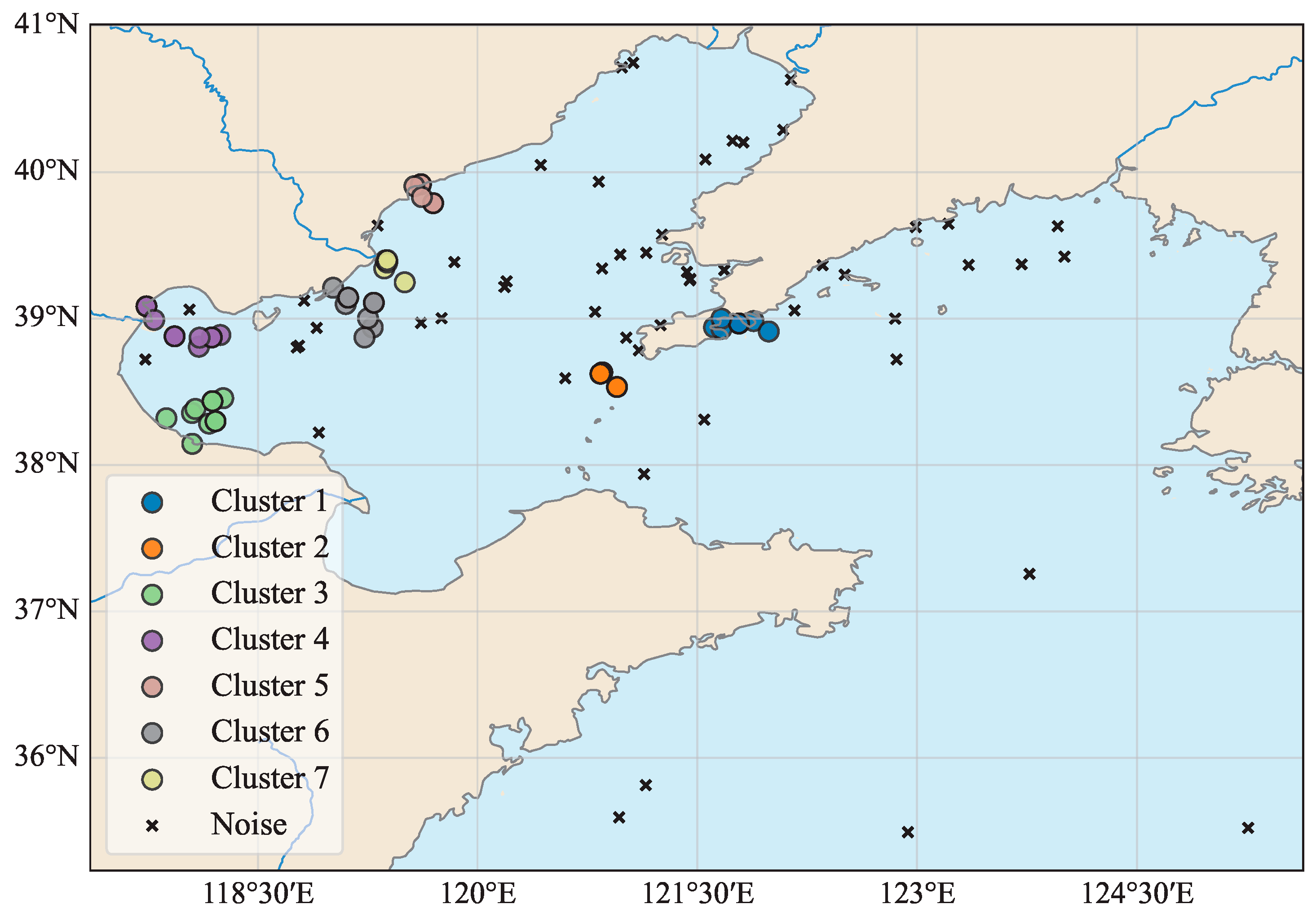

2.3. Distribution Characteristics of Accident Locations

3. Method

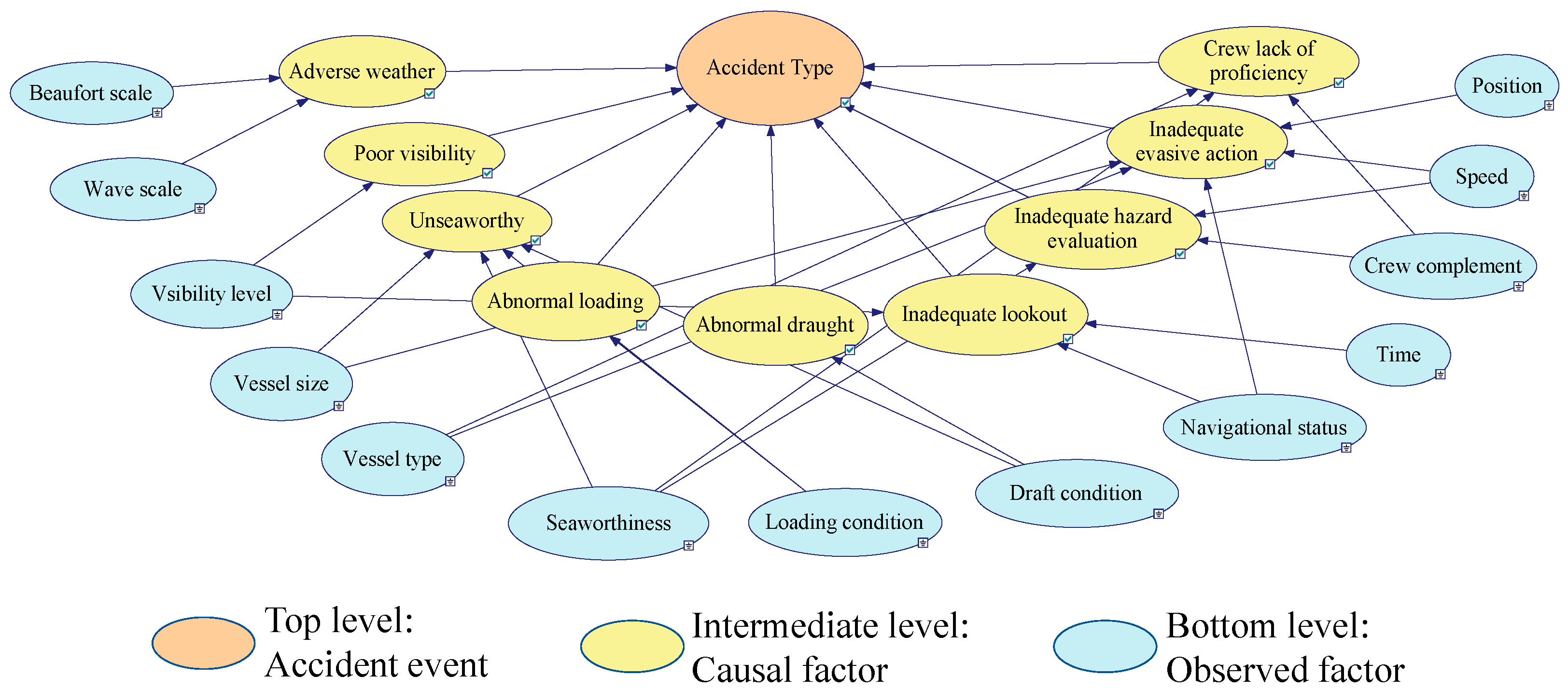

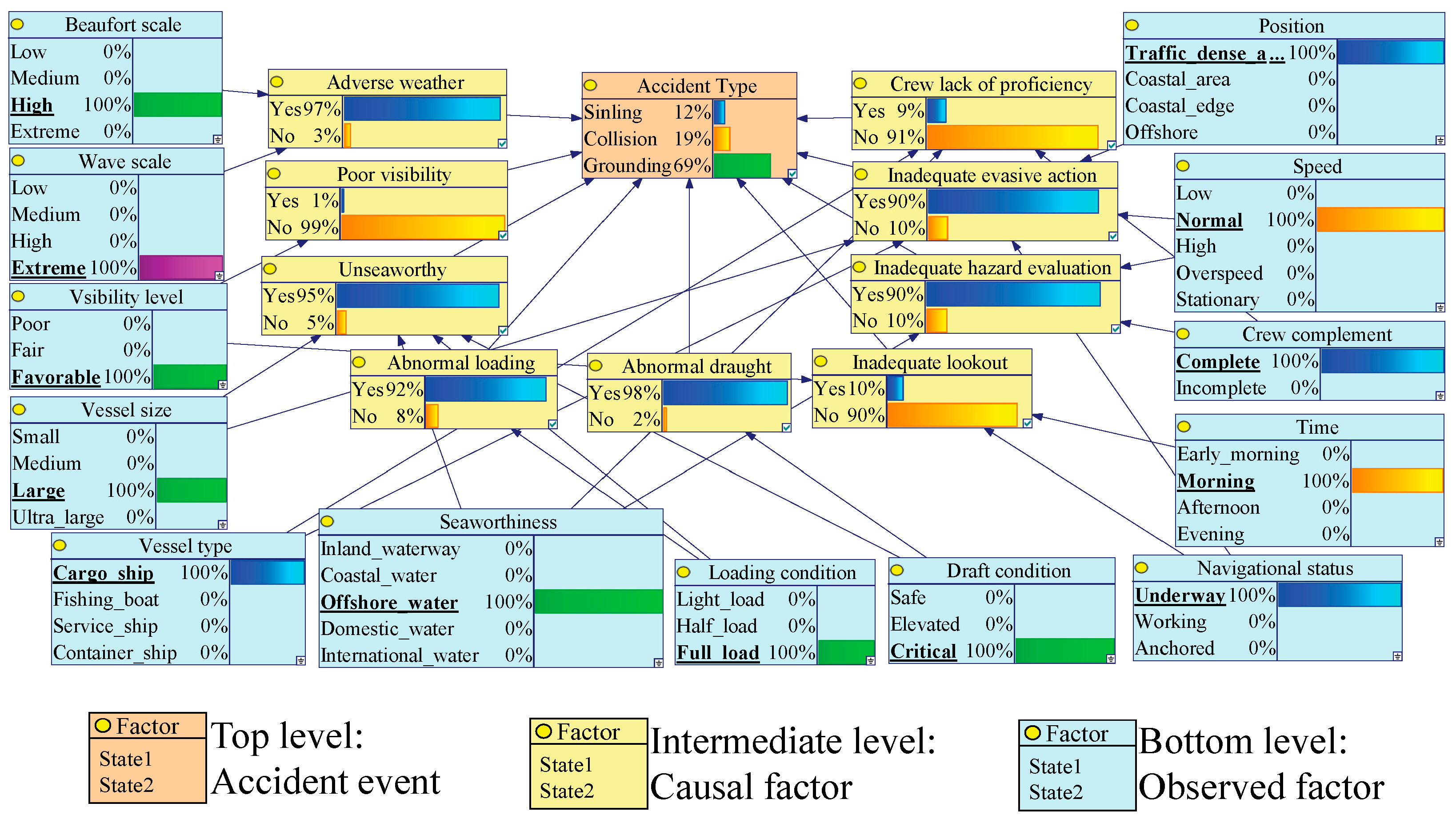

3.1. Identification of Risk Factors

- Observational factors (e.g., wind force, wave height, visibility), directly obtained from recorded environmental and operational parameters, subsequently discretized into multiple states;

- Causal factors (e.g., crew incompetence, vessel unseaworthiness), standardized from the investigative conclusions and transformed into Boolean variables, recorded as “Yes” if present in the accident and “No” otherwise.

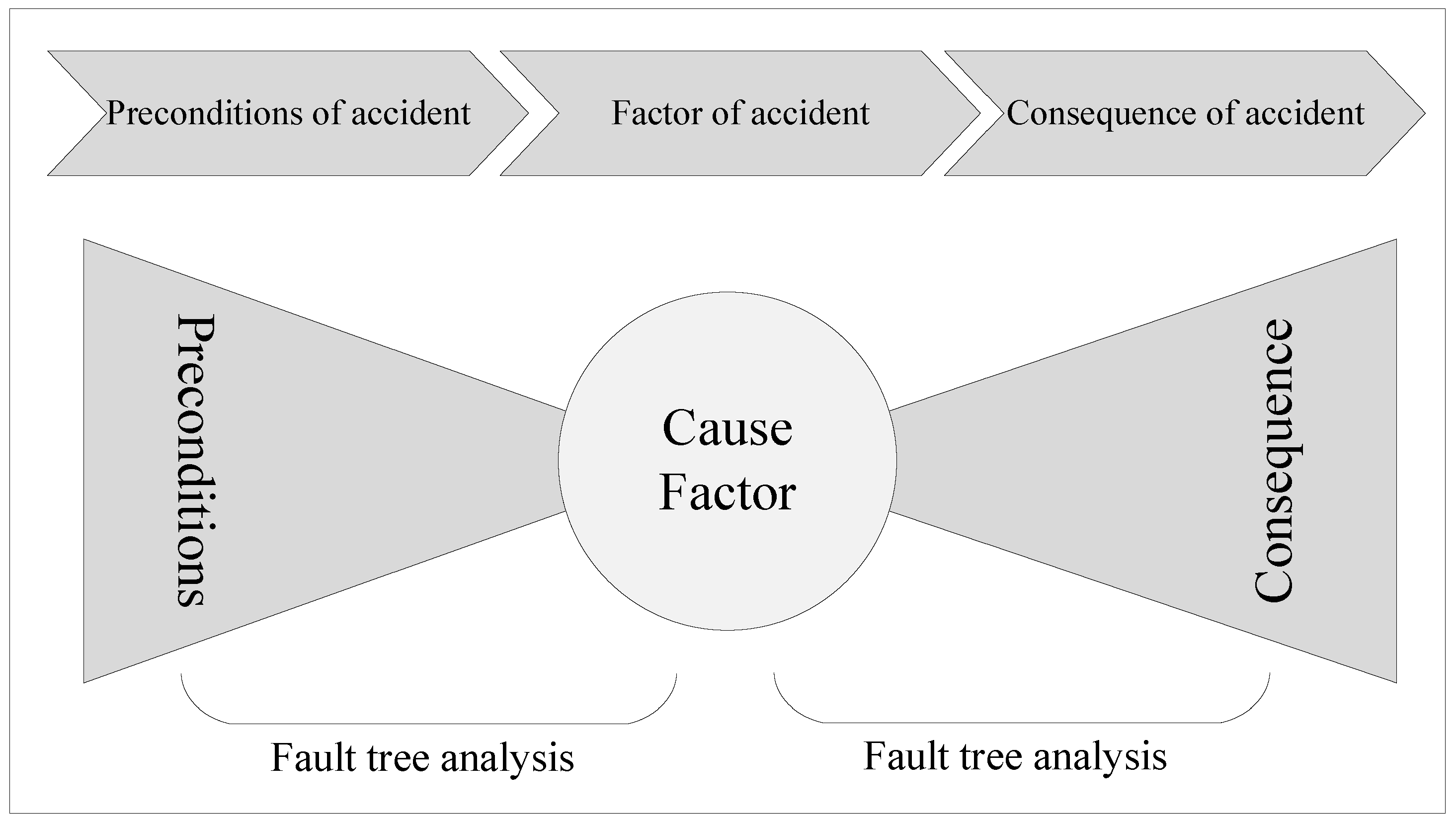

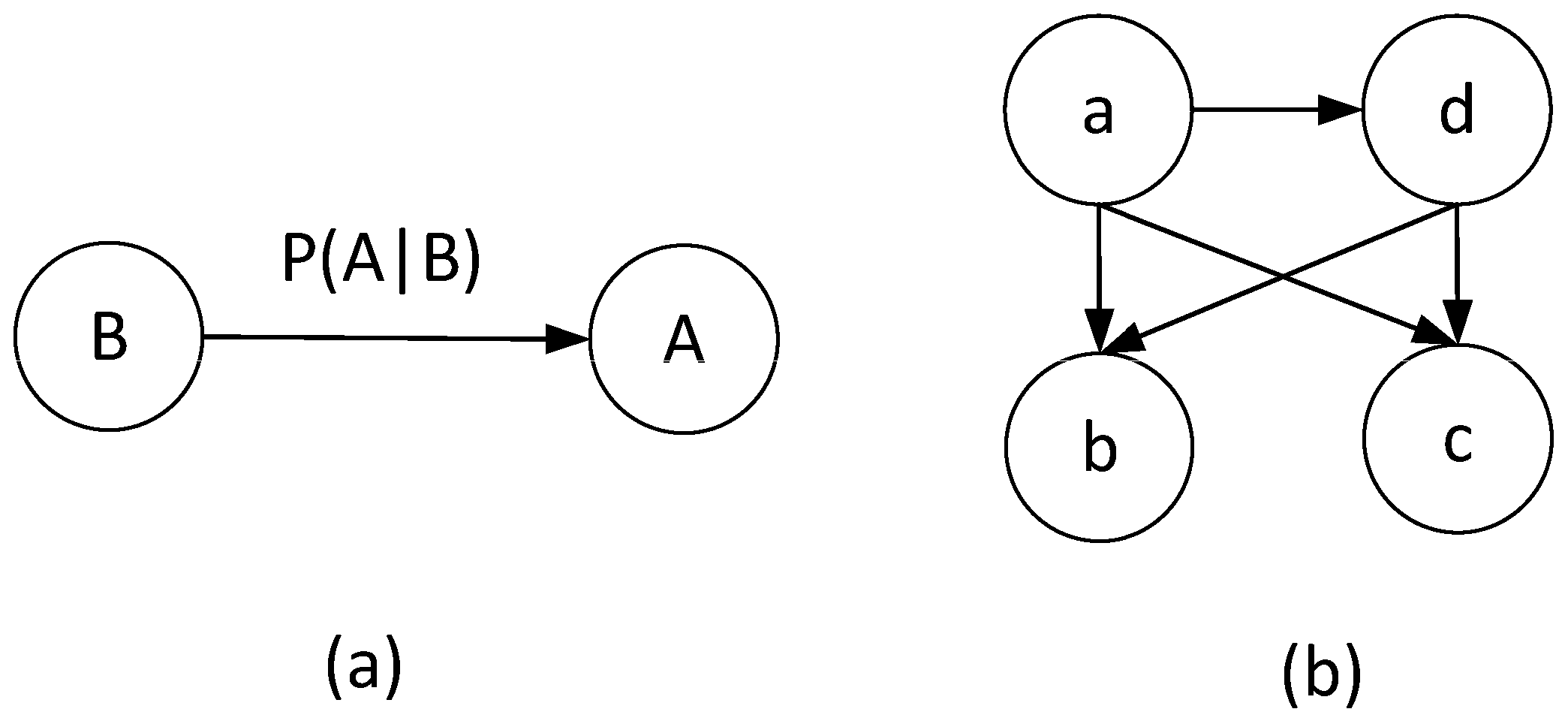

3.2. Construction of the Bow-Tie Bayesian Network (BT-BN)

3.3. Parameterization and Probability Estimation

3.4. Validation Framework and Inference Mechanism

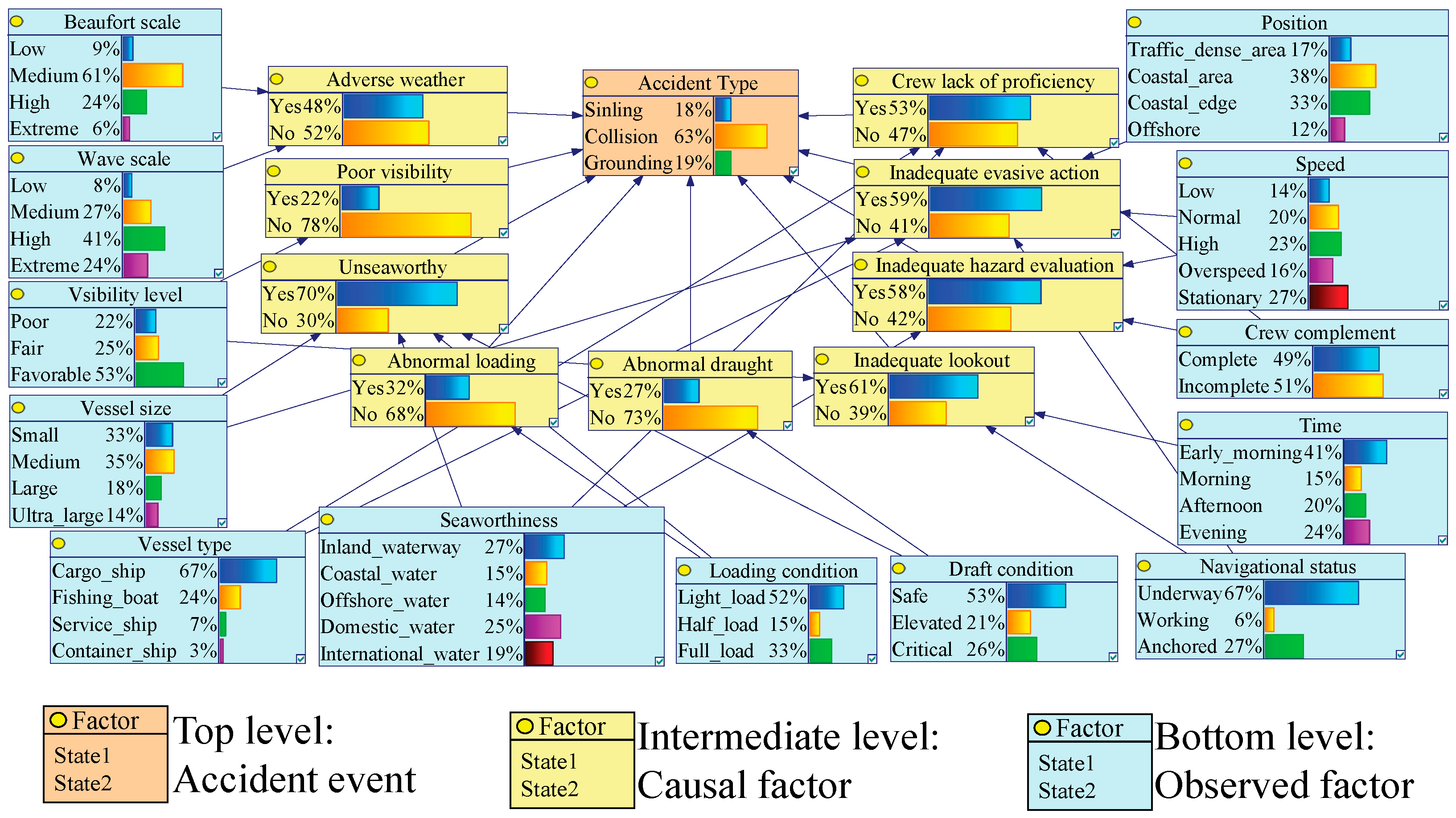

4. BT-BN-Based Maritime Accident Risk Assessor for the Bohai Sea

4.1. Structure Learning

4.2. Parameter Learning

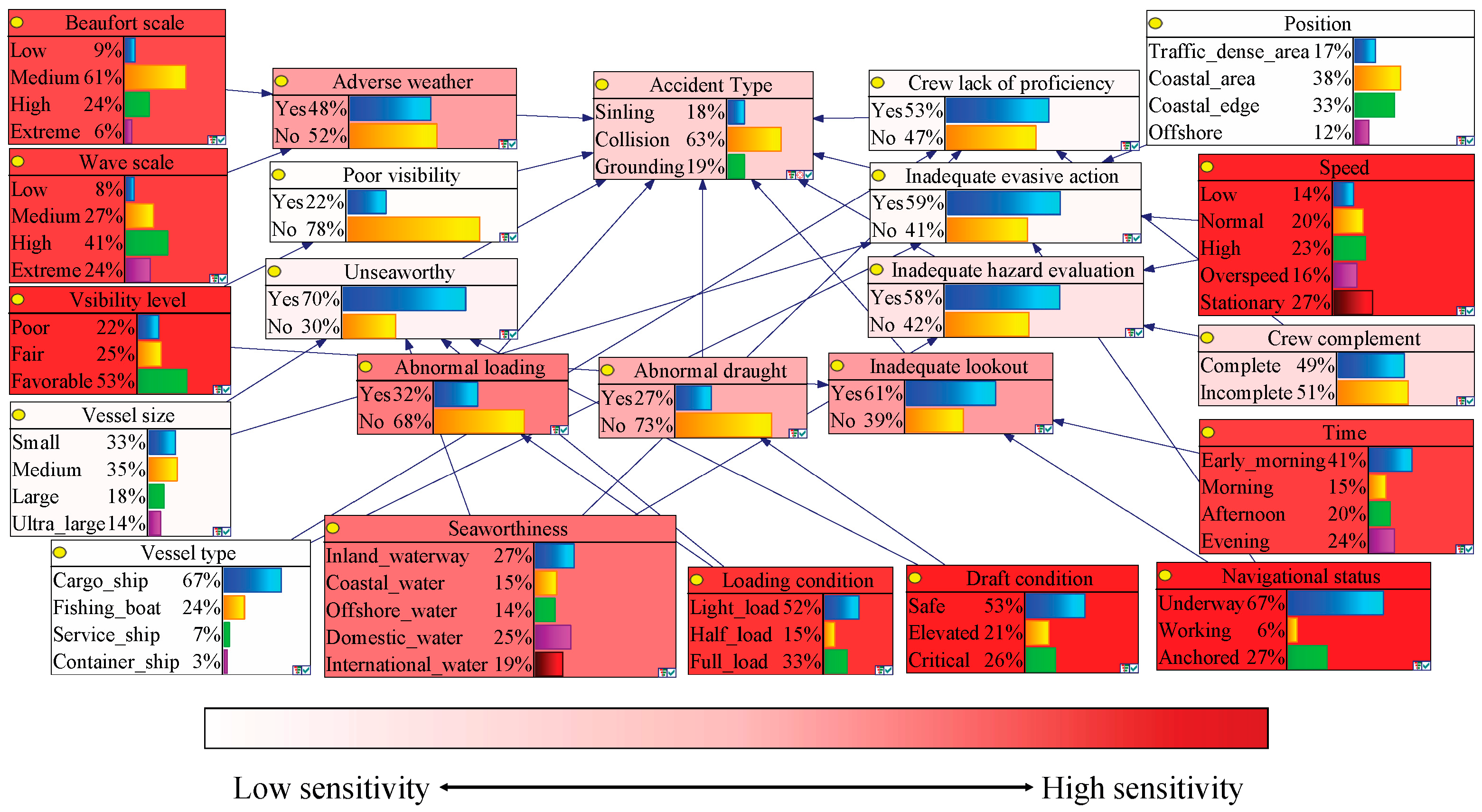

4.3. Global Sensitivity Analysis of Accident Risk

4.4. Hierarchical Impact Analysis of Risk Factors

5. Model Validation

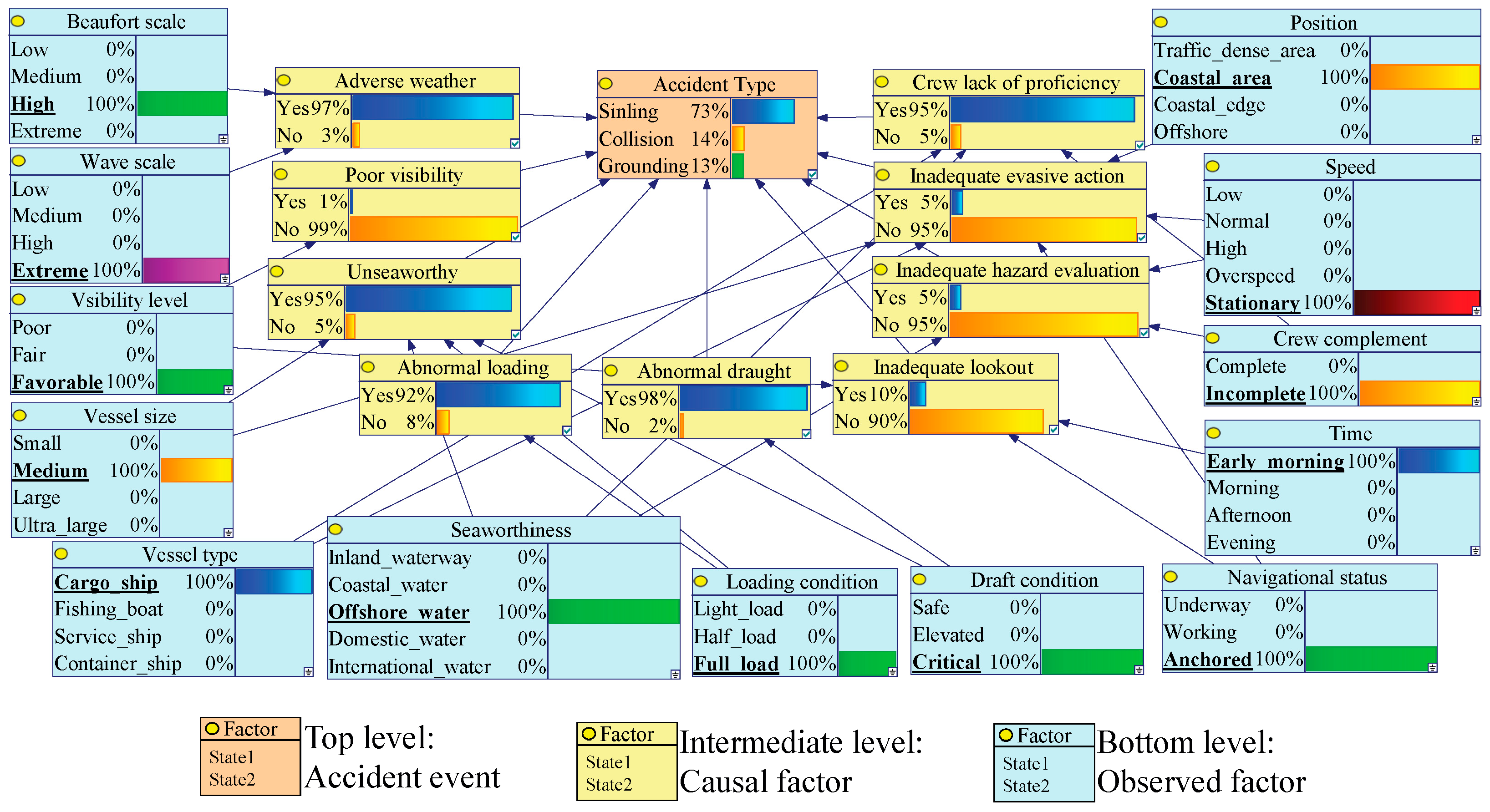

5.1. Sinking Case Study

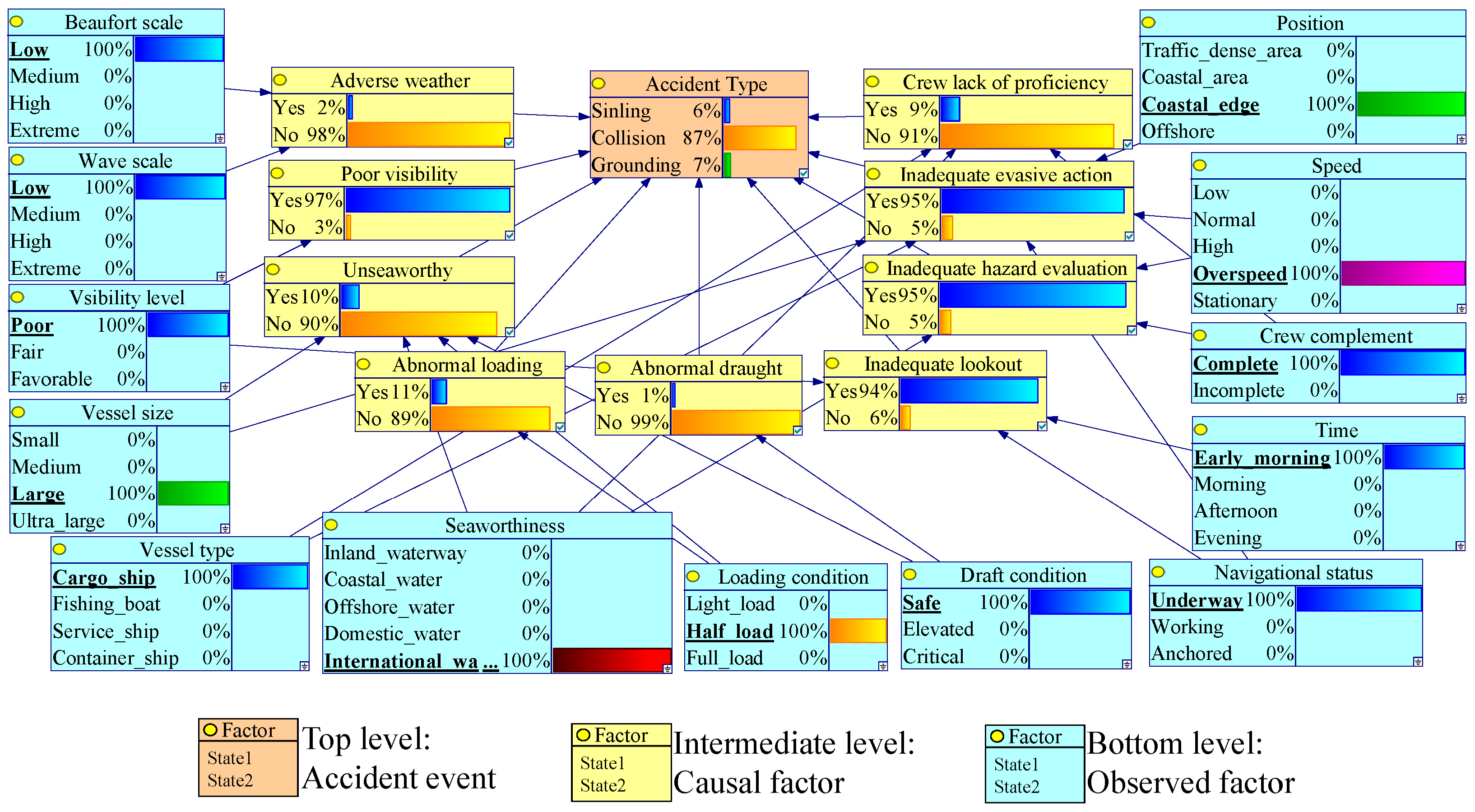

5.2. Collision Case Study

5.3. Grounding Case Study

6. Results and Recommendations

6.1. Construction Results of Causal Chain

6.2. Recommendations for Maritime Safety Management

6.2.1. Collision Accidents

6.2.2. Sinking Accidents

6.2.3. Grounding Accidents

6.2.4. Overall Recommendations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Q.; Hu, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, Z. Reconstructing and assessing global maritime transport network: Based on the Port Cargo Composite Transport index. Marit. Policy Manag. 2025, 52, 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Fan, H.; Chang, Z.; Lyu, J. Unleashing Data Power: Driving Maritime Risk Analysis with Bayesian Networks. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264, 111310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Graham, T.; Wang, J. An analysis of factors affecting the severity of marine accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 210, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sun, X.; Chen, J.; Cheng, C. Spatial patterns and characteristics of global maritime accidents. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 206, 107310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EMSA. Annual Overview of Marine Casualties and Incidents; EMSA: Lisbon, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Çelik, C.; Bashir, M.; Zou, L.; Yang, Z. Incorporation of a global perspective into data-driven analysis of maritime collision accident risk. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 249, 110187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Taimuri, G.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Yan, X.; Kujala, P.; Hirdaris, S. Systems driven intelligent decision support methods for ship collision and grounding prevention: Present status, possible solutions, and challenges. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 253, 110489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzate, R.F.; Tanguilan Corpuz, J.; Maraasin Corpuz, J.M.C. Case Study Analysis in Maritime Incidents: A Research Tool for Advancing Safety, Sustainability, and Security. In Research Methods for Advancing the Maritime Industry; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2025; pp. 109–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.Y.; Yang, X. Analyzing ship collision accidents in China: A framework based on the NK model and Bayesian networks. Ocean Eng. 2024, 309, 118619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, S.; Shu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Xie, C.; Zeng, X. Risk evolution and prevention and control strategies of maritime accidents in China’s coastal areas based on complex network models. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2023, 237, 106527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Péry, C.; Tassabehji, R.; Corset, F.; Chreim, Z. A holistic view of maritime navigation accidents and risk indicators: Examining IMO reports from 2011 to 2021. J. Shipp. Trade 2023, 8, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilatis, A.N.; Pagonis, D.N.; Serris, M.; Peppa, S.; Kaltsas, G. A statistical analysis of ship accidents (1990–2020) focusing on collision, grounding, hull failure, and resulting hull damage. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2024, 12, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhuang, C.; Shi, J.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Liu, J. Risk factors extraction and analysis of Chinese ship collision accidents based on knowledge graph. Ocean Eng. 2025, 322, 120536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Liang, T.; Hu, S.; Loughney, S.; Wang, J. Characteristics analysis of intercontinental sea accidents using weighted association rule mining: Evidence from the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baalisampang, T.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Khan, F.; Dadashzadeh, M. Review and analysis of fire and explosion accidents in maritime transportation. Ocean Eng. 2018, 158, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maternová, A.; Materna, M.; Dávid, A.; Török, A.; Švábová, L. Human Error Analysis and Fatality Prediction in Maritime Accidents. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coraddu, A.; Oneto, L.; Navas de Maya, B.; Kurt, R. Determining the most influential human factors in maritime accidents: A data-driven approach. Ocean Eng. 2020, 211, 107588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Zhang, J.; Wan, C.; Zhang, M.; Soares, C.G. A data-driven bayesian network model for risk influencing factors quantification based on global maritime accident database. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 259, 107473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, R.; Du, Q. Investigation of distinct and joint contributions of human factors and operational conditions to different types of maritime accidents. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2025, 267, 107750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adumene, S.; Afenyo, M.; Salehi, V.; William, P. An adaptive model for human factors assessment in maritime operations. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2022, 89, 103293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wen, Y.; Huang, Y.; Song, L.; Sui, Z. Inland waterway autonomous transportation: System architecture, infrastructure and key technologies. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 46, 100858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.Y.; Wu, H.T. An Automatic-Identification-System-Based Vessel Security System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, M.; Cavallaro, L.; Castro, E.; Musumeci, R.E.; Martignoni, M.; Roman, F.; Foti, E. New frontiers in the risk assessment of ship collision. Ocean Eng. 2023, 274, 113999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, I.; Perčić, M.; Vladimir, N. Assessment of human contribution to cargo ship accidents using Fault Tree Analysis and Bayesian Network Analysis. Ocean Eng. 2025, 323, 120628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zheng, Q.q.; Guo, Y. Maritime accident causation: A spatiotemporal and HFACS-Based approach. Ocean Eng. 2025, 340, 122329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaptan, M.; Sarialiioğlu, S.; Uğurlu, O.; Wang, J. The evolution of the HFACS method used in analysis of marine accidents: A review. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2021, 86, 103225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Wang, X.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yang, Z. Improving maritime accident severity prediction accuracy: A holistic machine learning framework with data balancing and explainability techniques. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2026, 266, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wamugi, J.W.; Camliyurt, G.; Sakar, C.; Park, S.; Park, Y.; Aydin, M.; Kim, D. Probabilistic modeling of domestic ferry accident causes in Kenya’s Likoni ferry route using fuzzy Bayesian network. Ocean Eng. 2025, 340, 122388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceylan, B.O.; Elidolu, G.; Sezer, S.I.; Akyuz, E.; Yang, Z. Probabilistic risk assessment for inert gas system on oil tanker ships using system theoretic accident model and process (STAMP) and Bayesian belief network (BBN). Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 266, 111669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Jia, H.; He, X.; Lyu, J. Navigating uncertainty: A dynamic Bayesian network-based risk assessment framework for maritime trade routes. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 250, 110311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, P.; Mou, J.; Chen, L.; Li, M. Critical causation factor analysis in ship collision accidents with complex network. Ocean Eng. 2025, 315, 119837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xue, Y.; Lu, Y.; Yuan, L.; Li, F.; Li, R. A Dynamic Bayesian Network model for ship navigation risk in the Arctic Northeast Passage. Ocean Eng. 2024, 312, 119024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Yang, Z. Risk analysis of Arctic navigation using text mining (TM) and improved association rule mining (ARM) methods. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 103990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, U.; Teixeira, A.; Guedes Soares, C. Casualty analysis methodology and taxonomy for FPSO accident analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 218, 108169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, X.; Feng, L.; Grifoll, M.; Feng, H. Causation Analysis of Marine Traffic Accidents Using Deep Learning Approaches: A Case Study from China’s Coasts. Systems 2025, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedi, L.; Faury, O.; Etienne, L.; Cheaitou, A.; Rigot-Muller, P. Application of the IMO taxonomy on casualty investigation: Analysis of 20 years of marine accidents along the North-East Passage. Mar. Policy 2024, 162, 106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, L.; Niyazbekova, S.; Khalilova, M.; Andrianova, L.; Annenskaya, N.; Brovkina, N.; Guseva, I.; Abalakina, T.; Matrosov, S.; Abdusattarova, S. Development of maritime transport: Features and financial component in market conditions. Transp. Res. Procedia 2022, 63, 1410–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, J. GIS-based analysis on the spatial patterns of global maritime accidents. Ocean Eng. 2022, 245, 110569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Shi, M.; Lang, X.; You, Q.; Jing, Y.; Huang, D.; Dai, H.; Kang, J. Dynamic risk evaluation of hydrogen station leakage based on fuzzy dynamic Bayesian network. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 50, 1131–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acarbay, C.; Kiyak, E. Risk mitigation in unstabilized approach with fuzzy Bayesian bow-tie analysis. Aircr. Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2020, 92, 1513–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Huang, S.; Wang, Q.; Li, N.; Chen, Y. Evolutionary study of leakage and explosion accidents in green hydrogen production process. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 143, 2–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Cao, Y.; Deng, X. A Novel Z-Network Model Based on Bayesian Network and Z-Number. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 1585–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; An, X.; Xing, J. A data-driven Bayesian network model integrating physical knowledge for prioritization of risk influencing factors. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 160, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mun, C.; Bai, J.W.; Song, J. Hierarchical Bayesian models with subdomain clustering for parameter estimation of discrete Bayesian network. Struct. Saf. 2025, 114, 102570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjati, S.; Beigy, H. Improved K2 algorithm for Bayesian network structure learning. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 91, 103617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokukcu, M.; Sakar, C. Risk analysis of collision accidents during underway STS berthing maneuver through integrating fault tree analysis (FTA) into Bayesian network (BN). Appl. Ocean Res. 2022, 126, 103290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, S.A.M.; Paik, J.K. Hazard identification and scenario selection of ship grounding accidents. Ocean Eng. 2018, 153, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Fan, S.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Shi, R. Analysis of factors affecting the severity of marine accidents using a data-driven Bayesian network. Ocean Eng. 2023, 269, 113563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Y.A.; Theotokatos, G.; Maslov, I.; Wennersberg, L.A.L.; Nesheim, D.A. Regulatory and legal frameworks recommendations for short sea shipping maritime autonomous surface ships. Mar. Policy 2024, 166, 106226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.D.; Yang, M.F.; Chen, S.T.; Hsu, H.K. Application of simulated AIS data to study the collision risk system of ships. J. Navig. 2024, 77, 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonci, M.; De Jong, P.; Van Walree, F.; Renilson, M.; Huijsmans, R. The steering and course keeping qualities of high-speed craft and the inception of dynamic instabilities in the following sea. Ocean Eng. 2019, 194, 106636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Canosa, J.M.; Orosa, J.A.; Galdo, M.I.L.; Barros, J.J.C. A New Theoretical Dynamic Analysis of Ship Rolling Motion Considering Navigational Parameters, Loading Conditions and Sea State Conditions. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2022, 10, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domeh, V.; Obeng, F.; Khan, F.; Bose, N.; Sanli, E. Loss of stability risk analysis in small fishing vessels. Ocean Eng. 2023, 287, 115780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himaya, A.N.; Sano, M. Course-Keeping Performance of a Container Ship with Various Draft and Trim Conditions under Wind Disturbance. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ringsberg, J.W.; Rita, F. A voyage planning tool for ships sailing between Europe and Asia via the Arctic. Ships Offshore Struct. 2020, 15, S10–S19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeskog, B. Risk, trust and reputation in the Norwegian offshore supply chain. Saf. Sci. 2023, 163, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norazahar, N.; Khan, F.; Veitch, B.; MacKinnon, S. Dynamic risk assessment of escape and evacuation on offshore installations in a harsh environment. Appl. Ocean Res. 2018, 79, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, G.; Rao, H.; Wang, S.; Yang, B.; Sun, Z. Numerical simulation of the maneuvering performance of ships in broken ice area. Ocean Eng. 2024, 294, 116783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasukawa, H.; Hirata, N. Effects of wave direction on ship turning in regular waves. Ocean Eng. 2023, 286, 115581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Teixeira, A.P. Comparative analysis of the impact of new inspection regime on port state control inspection. Transp. Policy 2020, 92, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cluster | Cluster Size | Center Latitude | Center Longitude | Position Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 8 | 38.958 | 121.770 | Dalian port outer fairway |

| 2 | 6 | 38.596 | 120.879 | Western Bohai strait shipping lane |

| 3 | 10 | 38.341 | 118.128 | Southern Bohai bay coastal route |

| 4 | 10 | 38.922 | 117.994 | Approaches to Tianjin port |

| 5 | 6 | 39.858 | 119.635 | Qinhuangdao-Tangshan coastal route |

| 6 | 9 | 39.069 | 119.188 | Central Bohai bay shipping lane |

| 7 | 5 | 39.354 | 119.401 | Qinhuangdao port anchorage/channel |

| Level | Category | Factor Node | State | Division Basis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top level | Accident | Accident event | Sinking, collision, grounding | - |

| Intermediate level (Causal factor) | Environmental | Adverse weather | Yes, no | - |

| Poor visibility | Yes, no | - | ||

| Vessel cause | Unseaworthy | Yes, no | - | |

| Abnormal loading | Yes, no | - | ||

| Abnormal draught | Yes, no | - | ||

| Crew cause | Inadequate lookout | Yes, no | - | |

| Hazard underestimation | Yes, no | - | ||

| Ineffective action | Yes, no | - | ||

| Crew lack of proficiency | Yes, no | - | ||

| Bottom level (Observed factor) | Meteorological parameter | Wind scale | Low, medium, high, extreme | Force: (0,3], (3,6], (6,8], (8,10], (10, ∞) |

| Wave scale | Low, medium, high, extreme | Wave height (m): (0,0.5], (0.5,1], (1,2], (2, ∞) | ||

| Visibility level | Poor, fair, favorable | - | ||

| Time | Early morning, morning, afternoon, evening | 00:00–6:00, 6:00–12:00, 12:00–18:00, 18:00–24:00 | ||

| Vessel static parameter | Vessel size | Small, medium, large, ultra large | Gross tonnage: (0,500], (500,3000], (3000,10,000], (10,000, ∞) | |

| Seaworthiness area | Inland waterway, coastal, offshore, domestic water, international water | - | ||

| Vessel type | Cargo ship, fishing boat, service ship, container ship | - | ||

| Vessel dynamic parameter | Loading condition | Light load, half load, full load | Load ratio: (0,30%], (30%,70%], (70%, ∞) | |

| Draft condition | Safe, elevated, critical | Draft ratio: (0,50%], (50%,80%], (80%, ∞) | ||

| Position | Traffic dense area, coastal area, coastal edge, offshore | Distance to shore (nm): (0,5], (5,20], (20,50], (50, ∞) | ||

| Speed | Low, normal, high, overspeed, stationary | Speed (knot): (0,4], (4,8], (8,12], (12, ∞) | ||

| Crew complement | Complete, incomplete | - | ||

| Navigational status | Underway, working, anchor | - |

| Causal Factor | Observed Factor | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Adverse weather | Wind scale | |

| Wave scale | ||

| Loading condition | ||

| Draft condition | ||

| Poor visibility | Vsibility level | |

| Unseaworthy | Seaworthiness area | |

| Loading condition | ||

| Draft condition | ||

| Vessel size | ||

| Abnormal loading | Loading condition | |

| Draft condition | ||

| Abnormal draught | Draft condition | |

| Loading condition | ||

| Inadequate lookout | Time | |

| Navigational status | ||

| Vsibility level | ||

| Hazard underestimation | Speed | |

| Seaworthiness area | ||

| Crew complement | ||

| Navigational status | ||

| Ineffective action | Navigational status | |

| Speed | ||

| Position | ||

| Vessel size | ||

| Vessel type | ||

| Wave scale | ||

| Crew incompetence | Crew complement | |

| Seaworthiness area | ||

| Vessel size |

| Edge | Score Drop () | Importance Ranking |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard underestimation → Accident | 344.16 | 1 |

| Adverse weather → Accident | 262.69 | 2 |

| Unseaworthy → Accident | 259.30 | 3 |

| Inadequate lookout → Accident | 258.61 | 4 |

| Abnormal loading → Accident | 258.18 | 5 |

| Poor visibility → Accident | 257.23 | 6 |

| Abnormal draught → Accident | 254.65 | 7 |

| Ineffective action → Accident | 254.36 | 8 |

| Crew lack of proficiency → Accident | 252.87 | 9 |

| Draft condition → Abnormal draught | 30.69 | 10 |

| Visibility level → Poor visibility | 24.58 | 11 |

| Wind scale → Adverse weather | 24.55 | 12 |

| Crew complement → Crew lack of proficiency | 17.80 | 13 |

| Time → Inadequate lookout | 15.05 | 14 |

| Wave scale → Adverse weather | 13.02 | 15 |

| Wave Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | Medium | High | Ultra | |||

| Wind Scale | Small | Yes | 0.0178 | 0.0833 | 0.0178 | 0.9166 |

| No | 0.9821 | 0.9166 | 0.9821 | 0.0833 | ||

| Medium | Yes | 0.1000 | 0.0750 | 0.1250 | 0.9466 | |

| No | 0.9000 | 0.9250 | 0.8750 | 0.0533 | ||

| High | Yes | 0.8566 | 0.8566 | 0.9100 | 0.9666 | |

| No | 0.1433 | 0.1433 | 0.0900 | 0.0333 | ||

| Ultra | Yes | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.9500 | 0.9715 | |

| No | 0.0500 | 0.0500 | 0.0500 | 0.0284 | ||

| Causal Factor | Grounding () | Collision () | Sinking () | Main Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse weather | +0.032 | −0.087 | +0.055 | Sinking, grounding |

| Poor visibility | +0.016 | −0.027 | +0.010 | Grounding, sinking |

| Unseaworthy | +0.005 | −0.006 | +0.001 | Negligible impact |

| Abnormal loading | +0.017 | −0.049 | +0.032 | Sinking, grounding |

| Abnormal draught | +0.029 | −0.053 | +0.025 | Sinking, grounding |

| Inadequate lookout | −0.018 | +0.052 | −0.034 | Collision |

| Hazard underestimation | +0.019 | −0.012 | −0.007 | Collision |

| Ineffective action | −0.012 | +0.028 | −0.015 | Collision |

| Crew incompetence | −0.019 | +0.027 | −0.009 | Collision |

| Event | Observed Factor | Peak State | Lift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grounding | Wind scale | High | 1.11 |

| Speed | High | 1.11 | |

| Draft condition | Critical | 1.09 | |

| Wave scale | High | 1.09 | |

| Position | Traffic dense area | 1.07 | |

| Time | Afternoon | 1.07 | |

| Crew complement | Complete | 1.06 | |

| Navigational status | Anchor | 1.06 | |

| Visibility level | Favorable | 1.05 | |

| Loading condition | Full load | 1.05 | |

| Seaworthiness area | Domestic water | 1.04 |

| Event | Observed Factor | Peak State | Lift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collision | Seaworthiness area | Inland waterway | 1.23 |

| Wind scale | Low | 1.10 | |

| Wave scale | Low | 1.10 | |

| Speed | Overspeed | 1.09 | |

| Time | Evening | 1.07 | |

| Loading condition | Light load | 1.06 | |

| Draft condition | Safe | 1.05 | |

| Crew complement | Incomplete | 1.05 | |

| Position | Offshore | 1.04 | |

| Navigational status | Underway | 1.03 | |

| Visibility level | Poor | 1.02 |

| Event | Observed Factor | Peak State | Lift |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinking | Wind scale | Extreme | 1.18 |

| Wave scale | Extreme | 1.16 | |

| Loading condition | Full load | 1.12 | |

| Navigational status | Anchor | 1.10 | |

| Seaworthiness area | Inland waterway | 1.09 | |

| Position | Traffic dense area | 1.08 | |

| Draft condition | Critical | 1.08 | |

| Speed | Stationary | 1.07 | |

| Time | Afternoon | 1.04 | |

| Visibility level | Favorable | 1.03 | |

| Crew complement | Incomplete | 1.01 |

| Event | Causal Chain | Environmental | Vessel Cause | Crew Cause | Causal Chain Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collision | Crew-dominated chain | Night navigation, poor visibility, complex waterways | — | Inadequate lookout, lack of evasive action, crew Incompetence | Complex environment or operational pressure → perception and judgment limitation → human error → collision |

| Speed-Equipment coupling chain | — | Overspeed | Insufficient evasive capability, delayed response | Overspeed or insufficient crew → reduced evasive time and capability → collision | |

| Sinking | Environment-load coupling chain | Extreme wind, extreme wave | Abnormal load, abnormal draft | — | Adverse weather and improper load → stability and structural degradation → control failure or flooding → sinking |

| Load management chain | — | Abnormal load, abnormal draft | Improper ballast | Abnormal load → insufficient stability or ballast imbalance → higher sinking risk in adverse sea conditions | |

| Grounding | Perception-control limitation chain | Poor visibility | Abnormal draft, high speed | Inadequate risk assessment | Poor visibility or abnormal draft → limited perception and reduced maneuverability → grounding |

| Weather-sea state chain | High wind, high wave | — | Lateral drift, control difficulty | High waves or cross currents → increased lateral forces → navigation control difficulty → grounding |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ou, J.; Wang, S.; Sun, C.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, C. A Bayesian Model Based on the Bow-Tie Causal Framework (BT-BN) for Maritime Accident Risk Analysis: A Case Study of the Bohai Sea. Oceans 2025, 6, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040074

Ou J, Wang S, Sun C, Zhao W, Jiang C. A Bayesian Model Based on the Bow-Tie Causal Framework (BT-BN) for Maritime Accident Risk Analysis: A Case Study of the Bohai Sea. Oceans. 2025; 6(4):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040074

Chicago/Turabian StyleOu, Junmei, Shuangxin Wang, Chuanhao Sun, Wenyu Zhao, and Chenglong Jiang. 2025. "A Bayesian Model Based on the Bow-Tie Causal Framework (BT-BN) for Maritime Accident Risk Analysis: A Case Study of the Bohai Sea" Oceans 6, no. 4: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040074

APA StyleOu, J., Wang, S., Sun, C., Zhao, W., & Jiang, C. (2025). A Bayesian Model Based on the Bow-Tie Causal Framework (BT-BN) for Maritime Accident Risk Analysis: A Case Study of the Bohai Sea. Oceans, 6(4), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/oceans6040074