Abstract

Tongue-nibbling is a rare and previously undocumented affiliative behaviour in free-ranging killer whales (Orcinus orca), until now seen only in individuals under human care. This study presents the first recorded observation of tongue-nibbling between two wild killer whales in the Kvænangen fjords, Norway. The interaction, captured opportunistically by citizen scientists during a snorkelling expedition, lasted nearly two minutes and involved repeated episodes of gentle, face-to-face oral contact. This behaviour closely resembles sequences observed and described in detail in zoological settings, suggesting that it forms part of the species’ natural social repertoire. The observation also supports the interpretation of tongue-nibbling as a socially affiliative behaviour, likely involved in reinforcing social bonds, particularly among juveniles. The prolonged maintenance of this interaction in managed populations originating from geographically distinct Atlantic and Pacific lineages further indicates its behavioural conservation across contexts. This finding underscores the importance of underwater ethological observation in capturing cryptic social behaviours in cetaceans and illustrates the value of integrating citizen science into systematic behavioural documentation. The study also reinforces the relevance of managed populations in ethological research and highlights the ethical need for carefully regulated wildlife interaction protocols in marine tourism.

1. Introduction

The study of social behaviour in animals is a cornerstone of behavioural ecology, offering crucial insights into the biological and ecological dynamics of different species. Social animals, ranging from insects to primates, exhibit complex behavioural repertoires that serve to facilitate communication, cooperation, and group cohesion [,]. In primates, for instance, research on social dynamics has elucidated behaviours related to hierarchy (dominance and submission), agonism, affiliation, and reconciliation []. Analogous dominance–submission patterns have also been described in species as diverse as gorillas [], elephants [], dolphins [], and killer whales [].

Despite the relevance of such research, cetacean social behaviour remains particularly challenging to study due to the aquatic environment in which most of their activity occurs, largely beneath the water’s surface. This constraint has historically limited direct observation and led researchers to infer social interactions based on proximity at the surface. For example, Thomsen [] categorised the surface behaviour of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) near Vancouver Island into social and non-social contexts, depending on whether individuals were within or beyond one body length of each other—an approach grounded in earlier work by Ford []. This proximity-based framework has since been employed in various studies, including those by Gibson [] on bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) in Shark Bay, Parsons [] on killer whales, and Marley [] on Tursiops aduncus in Western Australia. While useful, such methods often simplify the complexity of cetacean interactions, underscoring the need for more granular approaches supported by emerging technologies.

Efforts to refine our understanding of cetacean sociality have increasingly focused on describing specific patterns of synchronised behaviour, particularly among animals under human care. Clegg et al. [], for instance, analysed synchronised swimming and tactile interactions in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) in managed environments. Serres et al. [] extended these observations to multiple captive cetacean species. However, these studies remain largely constrained to behaviours visible at the surface, offering limited access to the full social repertoire displayed underwater.

To overcome these observational limitations, underwater studies have proven essential. Christiansen et al. [] examined the surface-level social behaviour of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops aduncus) off Zanzibar, noting that the presence of tourist vessels reduced resting and social time while increasing travel and foraging. In contrast, Dudzinski et al. [] and Delfour [] employed underwater methodologies to provide more detailed behavioural descriptions. More recently, Manitzas Hill [] combined both surface and subsurface observations to document activity budgets in killer whales under human care, thereby offering a more comprehensive understanding of behavioural variation in managed populations.

A pivotal contribution to the ethology of killer whales was the ethogram compiled by Martínez and Klinghammer in 1978 [], based on both captive and free-ranging individuals. Their work catalogued over 50 behaviours, including both surface and underwater actions. Among the behaviours described was a peculiar interaction termed “nibbling,” in which one whale gently mouthed the tongue of another.

Decades later, Sánchez-Hernández et al. [] revisited this behaviour under human care, describing it for the first time in detail and interpreting it as an affiliative interaction. The study found that nibbling occurred predominantly among females and juveniles and situated it within a broader analysis of reconciliation behaviours, suggesting its importance in promoting group cohesion.

However, in the absence of comparable reports from wild populations, the ethological validity of such behaviours has sometimes been questioned. Some could have hypothesised that such behaviours could represent stereotypy, aberrant behaviour or an ephemeral fad, akin to the placement of dead salmon atop the head—a behaviour previously reported in killer whales.

This study presents the first documented case of tongue-nibbling between two wild killer whales in Norway. This finding confirms that the behaviour, previously observed only under human care, also occurs in the wild, thereby supporting its interpretation as part of the natural social repertoire of the species.

2. Observation Context and Recording Conditions

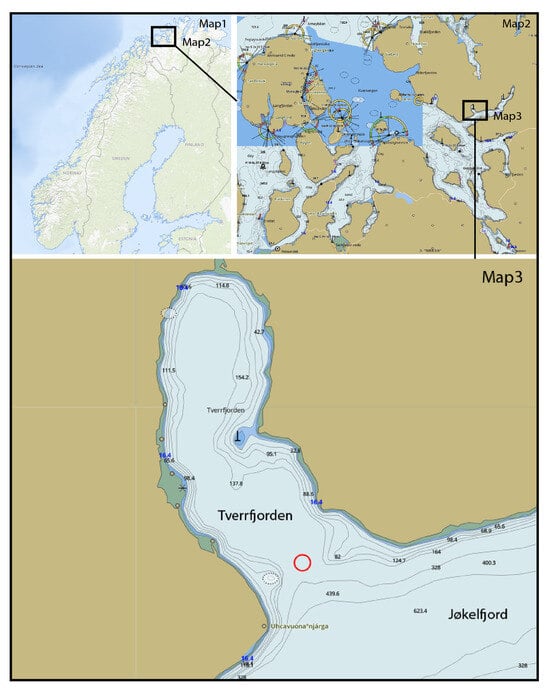

The focal observation was made on 11 January 2024 at approximately 10:40 local time in the Kvænangen fjords, northern Norway. Specifically, the event occurred at the entrance of Tverrfjorden, a sheltered bay located on the northern side of Jøkelfjord (Figure 1). These fjords are known for hosting seasonal aggregations of herring and cetaceans, and their calm winter conditions are conducive to in-water observations. A small group of snorkellers, under the supervision of experienced expedition leaders, entered the water from a Zodiac support boat deployed from the main expedition vessel. The entry protocol followed standard cetacean observation practices aimed at minimising disturbance: animals were approached slowly and from the side, and snorkellers floated in a passive, horizontal position once in the water. The environmental conditions at the time were favourable, with light wind, low swell (less than one metre), and good underwater visibility (estimated at 12–15 m). The orcas were slowly travelling, and no feeding or evasive behaviours were observed. The focal behavioural interaction took place between two adult-sized killer whales diving under the snorkellers at an approximate distance of 10–15 m. The entire sequence was recorded using a handheld GoPro Hero 11 Black action camera operated by one of the snorkellers. The footage was later analysed to identify and characterise the behaviours observed. The video of the 2024 observation is publicly available via the institutional repository and can be accessed at (accessed on 5 June 2025): https://research-data.ull.es/datasets/xj2yxc3cwp/1.

Figure 1.

Map showing the location of the Kvænangen fjords, northern Norway, where the observed interaction between two wild killer whales (Orcinus orca) was recorded.

3. Results

On 31 October 2024, at approximately 13:30 local time, a behavioural interaction between two free-ranging killer whales (Orcinus orca) was recorded during a snorkelling expedition at the entrance of Tverrfjorden, a sheltered bay located on the northern side of Jøkelfjorden in the Kvænangen fjords, northern Norway. The weather conditions were calm and overcast, with light winds between 4 and 6 knots and mirror-like water surfaces within Tverrfjorden. These conditions provided a stark contrast to the adjacent fjord systems, where wind gusts exceeded 35 knots and wave heights reached approximately 50 cm in Jøkelfjorden. No other vessels or rigid inflatable boats (RIBs) were present in the area at the time of the observation.

The group of snorkellers operated two Zodiacs, each carrying six guests and an expedition leader. The main vessel, Vestland Explorer, remained anchored outside Jøkelfjorden and did not enter Tverrfjorden during the operations. Multiple groups of killer whales were present in the fjord throughout the day, with an estimated total of approximately 30 individuals. Observations began at around 11:00, with initial sightings focused on a group of approximately 12 individuals engaged in sub-surface apparent feeding behaviour on dispersed bait balls. Additional groups were observed displaying reduced locomotor activity near the coastline.

At the time of the focal event, the group of 12 guests was floating in a single line formation at the entrance of Tverrfjorden. Within this context, two killer whales were observed engaging in a prolonged mouth-to-mouth interaction (Figure 2) that lasted for a total of 1 min and 49 s. The individuals approached one another and maintained contact between the anterior portions of their heads. The interaction comprised three discrete episodes: the first lasting 10 s, the second 26 s, and the third 18 s. Following the final episode, the individuals separated and swam away (see the complete video in the Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2.

Still frame from video footage recorded in the Kvænangen fjords, Norway, in 2024, showing the tongue-nibbling interaction between two free-ranging killer whales. See the Supplementary Materials for the complete video sequence.

The observed behaviour is consistent with the affiliative tongue-nibbling interaction previously described in a 2013 study at Loro Parque involving two killer whales under human care (Figure 3). In that case, one individual protruded its tongue while the other made gentle nibbling movements. The behaviour occurred in three sequences, interrupted by the withdrawal and re-extension of the tongue, lasting a total of approximately 15 s (see the complete video in the Supplementary Materials).

Figure 3.

Still frame from video footage recorded at Loro Parque in 2013, illustrating the tongue-nibbling behaviour between two killer whales under human care. See the Supplementary Materials for the full video sequence.

To assess the rarity and broader context of this behaviour, the authors consulted three professional divers and underwater videographers with extensive experience documenting killer whales in different geographic locations. None of the individuals consulted reported having recorded or directly observed tongue-nibbling interactions. One diver did recall an incident in which several killer whales approached an RIB while the group was preparing to enter the water. At that time, some observers on board remarked that the animals appeared to be “kissing” beneath the boat—a description identical to that provided independently by the guests who recorded the event in Tverrfjorden. Additionally, the authors sought confirmation from the senior marine mammal trainers at Loro Parque, who affirmed their familiarity with the behaviour. They reported that tongue-nibbling was observed repeatedly among four individuals housed at the facility, although the behaviour had not been observed in subsequent years.

4. Discussion

Although the video footage recorded in the Kvænangen fjords lacks the resolution required to discern fine-scale details of the tongue and mouth movements of the wild killer whales involved, the sustained frontal facial contact between the individuals, the prolonged duration of the episodes, and the overall behavioural pattern strongly support the interpretation that the observed interaction corresponds to the tongue-nibbling behaviour originally described by Martínez and Klinghammer in 1978 [] and later documented in detail in a zoological context by Sánchez-Hernández et al. (2019) []. These new observations provide empirical support for the hypothesis that tongue-nibbling forms part of the natural behavioural repertoire of Orcinus orca and is not a behavioural artefact induced by captivity-related conditions such as stereotypy, aberrant expression or transient cultural novelty.

The reappearance of this behaviour more than three decades after its initial description under human care—first noted shortly after killer whale husbandry was established, and subsequently recorded in detail in 2013—suggests remarkable behavioural continuity across generations in zoological environments. This temporal consistency implies that tongue-nibbling may be a socially conserved behaviour. Furthermore, the fact that it has taken 47 years since its original ethological description to obtain comparable footage from a wild population highlights the considerable difficulty in documenting rare or cryptic behaviours in natural contexts, particularly in highly mobile marine species whose social interactions occur predominantly beneath the water’s surface.

Notably, tongue-nibbling in killer whales exhibits significant parallels with recently documented mouth-to-mouth interactions in belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) under human care, as reported by Ham et al. (2023) []. In both species, these interactions primarily involve younger individuals and appear to serve a clearly affiliative function. As with the behaviour described by Martínez and Klinghammer [] and later detailed by Sánchez-Hernández et al. [], the beluga interactions are characterised by gentle, coordinated oral contact without any evident signs of aggression or dominance. This congruence supports the affiliative interpretation advanced by Sánchez-Hernández and colleagues and suggests that oral behaviours may represent socially meaningful interactions in odontocetes.

The cross-species resemblance reinforces the hypothesis that oral contact behaviours in toothed whales may contribute to the development of both social and motor skills during early ontogeny. In this context, tongue-nibbling and similar behaviours may serve as low-conflict mechanisms for strengthening social bonds among conspecifics not yet involved in adult roles such as mating or dominance competition. The recurrence of such behaviours in distantly related taxa, including killer whales and belugas, suggests that affiliative oral interactions may represent a phylogenetically conserved socio-developmental strategy in odontocetes.

The individual in which Martínez and Klinghammer [] first recorded tongue-nibbling—Hugo—was a juvenile male of approximately 13 years, originating from the Southern Resident killer whale population off Vancouver Island in the Pacific Ocean []. In contrast, the individuals observed by Sánchez-Hernández et al. [] at Loro Parque in 2013 were all born under human care and descended from a mix of lineages: some were of Icelandic (North Atlantic) and Canadian (North Pacific) origin, while one female, Morgan, was a rescued individual from the Norwegian (North Atlantic) population []. This diversity of geographic and genetic origins suggests that tongue-nibbling is not population-specific but rather a widely distributed behaviour within the species.

Historically, studies of cetacean social behaviour have relied heavily on surface-based observations from vessels or coastal vantage points [,], which has severely constrained the ability to describe the subtleties and complexity of social interactions. These methodological limitations have often led to the grouping of heterogeneous behaviours under broad, catch-all categories such as “socialising” [,,], thereby obscuring distinctions between specific types of interaction. Only in recent years has progress been made in refining ethological classifications at the surface, with increased attention given to behavioural patterns such as synchronised swimming and physical contact in multiple cetacean species [,,]. Simultaneously, the use of underwater observation techniques has yielded more detailed behavioural data, facilitating the identification of specific interactions such as petting, rubbing, contact swimming, nibbling, and nudging in dolphins [,] and more recently in killer whales [].

That tongue-nibbling in killer whales—an interaction primarily expressed underwater—remained undescribed in the wild for nearly five decades underscores the indispensable role of subaquatic methodologies in cetacean behavioural research. Omitting the underwater dimension risks underestimating the richness of cetacean sociality and overlooking behaviours that may be central to group cohesion and individual bonding. Continued investment in underwater technologies and observation protocols is therefore vital to developing a more comprehensive and ecologically valid understanding of cetacean social systems.

Although killer whales under human care are unable to exhibit certain behaviours seen in wild populations, such as complex coordinated hunting strategies [], the sustained occurrence of tongue-nibbling—an apparently affiliative behaviour—across multiple decades in zoological facilities calls into question generalised criticisms regarding the relevance of managed populations in the study of natural social behaviour in cetaceans []. It is important, however, to recognise that while the behaviour itself may occur in both settings, the triggers or underlying motivations may differ according to contextual variables. Behavioural responses are shaped by environmental and social factors, including the potential for stress, which is a natural physiological mechanism observable in both captive and wild cetaceans. Thus, behavioural comparisons must consider these contextual influences on expression and causation. These findings support the argument that killer whales, and potentially other cetaceans in human care, may serve as valuable models for investigating naturally occurring social dynamics under controlled, observable conditions.

While this case study provides limited evidence, the long-term preservation of affiliative interactions such as tongue-nibbling in managed settings suggests that narrow portrayals of captive environments—focused solely on aggression or stress-related behaviours—may not capture the full complexity of cetacean sociality []. This observation supports the need for further ethological research grounded in detailed behavioural descriptions and a thorough examination of behavioural triggers. A scientifically robust analysis of cetacean sociality in zoological settings must encompass the full behavioural spectrum—including affiliative, sexual, and reconciliatory interactions—as well as the dynamic processes that contribute to social stability [,].

Accordingly, evaluating the social complexity of killer whales in managed environments demands methodologically rigorous approaches, grounded in comprehensive ethograms and incorporating both surface and subaquatic observations. Such an integrative framework not only enhances the interpretive resolution of behavioural studies but also allows for a clearer distinction between the observable description of behaviour and the potential triggers behind it. This facilitates meaningful cross-context comparisons and contributes to a more nuanced understanding of cetacean socioecology.

The successful documentation of a rare and cryptic behaviour such as tongue-nibbling in wild killer whales was made possible in part through contributions from citizen science and the increasing global prevalence of recreational in-water cetacean encounters. While it is true that such interactions occasionally yield data of scientific relevance, it is well established that tourism-based activities—such as whale watching and swim-with-cetaceans programmes—may pose significant risks to wild populations. Numerous studies have documented potential adverse effects, including altered behavioural patterns, increased physiological stress, and disruptions to group cohesion [,,,,].

It is therefore essential that all wildlife interaction activities comply strictly with established local and international regulations. Moreover, continuous welfare monitoring and robust impact assessments should be mandatory components of such programmes. Balancing the research potential of citizen-generated data with the ethical imperative to minimise anthropogenic disturbance is critical in ensuring both the integrity of behavioural science and the conservation of cetacean populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/oceans6020037/s1.

Author Contributions

J.A. conceptualized the study, wrote the manuscript, analyzed the data, and produced the figures. J.v.V. and D.B. run the citizen science program and participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research in Loro Parque has been approved by the Research Ethics and Animal Welfare Committee of the University of La Laguna. Reg. Num. (CEIBA2024-3515).

Data Availability Statement

The videos of the referenced behaviours are available as Supplementary Materials and can be downloaded from the University of la Laguna: Almunia Portolés, Javier (2025), “Tongue Nibbling in Killer Whales (Orcinus orca)”, University of La Laguna, V1, doi (accessed on 5 June 2025): https://doi.org/10.17632/xj2yxc3cwp.1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the individuals who captured the footage of the observed behaviour: Allison Kelly Estevez and Michael Estevez. We also extend our appreciation to the 95 guests who voluntarily shared their recordings during the Winter Whales of Norway Expeditions, operated by Waterproof Expeditions and led by Wild-Encounters under the direction of Johnny van Vliet and Debbie Bouma, between 22 October and 9 December 2024. Their generous contributions provided invaluable material for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alexander, R.D. The Evolution of Social Behavior. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1974, 5, 325–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhard, M.J.W. The Evolution of Social Behavior by Kin Selection. Q. Rev. Biol. 1975, 50, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, F.B.M.; Veenema, H.C. CHAPTER 2 The First Kiss: Foundations of Conflict Resolution Research in Animals. In Natural Conflict Resolution; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, M.M.; Robbins, A.M.; Gerald-Steklis, N.; Steklis, H.D. Long-Term Dominance Relationships in Female Mountain Gorillas: Strength, Stability and Determinants of Rank. Behaviour 2005, 142, 779–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittemyer, G.; Getz, W.M. Hierarchical dominance structure and social organization in African elephants, Loxodonta africana. Anim. Behav. 2007, 73, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamaki, N.; Morisaka, T.; Taki, M. Does body contact contribute towards repairing relationships? Behav. Process. 2006, 73, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Hernández, P.; Krasheninnikova, A.; Almunia, J.; Molina-Borja, M. Social interaction analysis in captive orcas (Orcinus orca). Zoo Biol. 2019, 38, 323–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomsen, F.; Franck, D.; Ford, J.K.B. On the communicative significance of whistles in wild killer whales (Orcinus orca). Naturwissenschaften 2002, 89, 404–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, J.K.B. Acoustic behaviour of resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) off Vancouver Island, British Columbia. Can. J. Zool. 1989, 67, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Q.A.; Mann, J. The size, composition and function of wild bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops sp.) mother-calf groups in Shark Bay, Australia. Anim. Behav. 2008, 76, 389–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, K.M.; Balcomb, K.C.; Ford, J.K.B.; Durban, J.W. The social dynamics of southern resident killer whales and conservation implications for this endangered population. Anim. Behav. 2009, 77, 963–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marley, S.A.; Kent, C.P.S.; Erbe, C.; Parnum, I.M. Effects of vessel traffic and underwater noise on the movement, behaviour and vocalisations of bottlenose dolphins in an urbanised estuary. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clegg, I.L.; Rödel, H.G.; Delfour, F. Bottlenose dolphins engaging in more social affiliative behaviour judge ambiguous cues more optimistically. Behav. Brain Res. 2017, 322, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serres, A.; Hao, Y.; Wang, D. Swimming features in captive odontocetes: Indicative of animals’ emotional state? Behav. Process. 2020, 170, 103998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christiansen, F.; Lusseau, D.; Stensland, E.; Berggren, P. Effects of tourist boats on the behaviour of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins off the south coast of Zanzibar. Endanger. Species Res. 2010, 11, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzinski, K.M.; Gregg, J.D.; Ribic, C.A.; Kuczaj, S.A. A comparison of pectoral fin contact between two different wild dolphin populations. Behav. Process. 2009, 80, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfour, F.; Vaicekauskaite, R.; García-Párraga, D.; Pilenga, C.; Serres, A.; Brasseur, I.; Pascaud, A.; Perlado-Campos, E.; Sánchez-Contreras, G.J.; Baumgartner, K.; et al. Behavioural diversity study in bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) groups and its implications for welfare assessments. Animals 2021, 11, 1715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, H.M.M.; Themelin, M.; Dudzinski, K.M.; Felice, M.; Robeck, T. Individual variation in activity budgets of a stable population of killer whales in managed care across a year. Behav. Process. 2025, 224, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, D.R.; Klinghammer, E. A partial ethogram of the killer whale (Orcinus orca). Carnivore 1978, 1, 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, J.R.; Lilley, M.K.; Wincheski, R.J.; Miranda, J.; Ángel, G. Velarde Dediós.; Kolodziej, K.; Pellis, S.M.; Hill, H.M.M. Playful mouth-to-mouth interactions of belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) in managed care. Zoo Biol. 2023, 42, 730–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wearing, S.; Buchmann, A.; Jobberns, C. Free Willy: The whale-watching legacy. Worldw. Hosp. Tour. Themes 2011, 3, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremers, D.; Lemasson, A.; Almunia, J.; Wanker, R. Vocal sharing and individual acoustic distinctiveness within a group of captive orcas (Orcinus orca). J. Comp. Psychol. 2012, 126, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.; Lusseau, D. A killer whale social network is vulnerable to targeted removals. Biol. Lett. 2006, 2, 497–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corkeron, P. Marine Mammal Captivity, an Evolving Issue. In Marine Mammals: The Evolving Human Factor. Ethology and Behavioral Ecology of Marine Mammals.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, L.; Rose, N.A.; Visser, I.N.; Rally, H.; Ferdowsian, H.; Slootsky, V. The harmful effects of captivity and chronic stress on the well-being of orcas (Orcinus orca). J. Vet. Behav. 2020, 35, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erbe, C. Underwater noise of whale-watching boats and potential effects on killer whales (Orcinus orca), based on an acoustic impact model. Mar. Mammal Sci. 2002, 18, 394–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, R.; Brunton, D.H.; Dennis, T. Dolphin-watching tour boats change bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) behaviour. Biol. Conserv. 2004, 117, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffar, A.; Madon, B.; Garrigue, C.; Constantine, R. Avoidance of whale watching boats by humpback whales in their main breeding ground in New Caledonia. Int. Whal. Comm. 2009, SC/61/WW6, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen, F.; Rasmussen, M.H.; Lusseau, D. Inferring energy expenditure from respiration rates in minke whales to measure the effects of whale watching boat interactions. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2014, 459, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C.; Pérez-Jorge, S.; Prieto, R.; Cascão, I.; Wensveen, P.J.; Silva, M.A. Exposure to whale watching vessels affects dive ascents and resting behavior in sperm whales. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).