Abstract

Background: Various socket designs exist, linking the residual limb together with the prosthetic components to restore the ability to walk; however, lack of socket comfort is a frequent complaint. Objective: To evaluate the impact of socket design on end-user comfort and mobility. Methods: A randomized crossover trial was set to compare comfort and mobility of above-knee amputees (AKAs) wearing an ischial containment (IC) or subischial (I-SUB) socket. Patients actively wearing IC sockets were recruited from 10 rehabilitation centers across the country. They were then fitted for an I-SUB socket by Certified Prosthetists (CPs) as an alternate socket. Participants were randomly assigned to start with one or the other socket. After a minimum of 2 weeks, each participant evaluated the Socket Comfort Score (SCS) (primary outcome) in various situations, performed the 2-min walk test, and answered the PLUS-M questionnaire (secondary outcomes). Results: A total of 25 participants were included, of whom 23 completed the study with full (n = 21) or partial data (n = 2). SCS were improved with I-SUB compared with IC in all situations, with significant differences in general, when sitting on a rigid chair, sitting in a car, and standing. The differences in self-reported mobility and walking distance at the 2-min walk test were not significant. At the end of the study, more than 80% of the participants chose to keep the I-SUB socket for their daily use. Conclusions: For the first time, this study supports that the subischial suction socket improves comfort in daily life without negatively impacting user mobility in a group of individuals with AKA.

1. Introduction

In France, 6138 people had a major lower limb amputation in 2022 [1], with 47% having an above-knee amputation (AKA) [1]. To regain the ability to walk, lower limb amputees must wear a lower limb prosthesis comprised of (i) a socket, which is the interface between the residual limb and the prosthesis, and (ii) prosthetic components (knee and foot). The socket is a key component of the prosthesis because the more intimately and comfortably it fits the residual limb, the better the transmission of the user’s actions from their body to the prosthesis, and ultimately the greater the proprioception and control. The first objective of a prosthesis is to allow amputees to walk and achieve activities of daily living, such as traversing uneven ground or ascending and descending stairs and ramps, as well as providing a comfortable sitting position. One of the challenges is to provide positive suspension via skin contact and, at the same time, limit shearing stress on the skin [2] to ensure comfort and maintain skin integrity.

Comfort becomes even more critical in a sitting position, as it represents a large part of the day. In able-bodied individuals, the sitting time per day is up to 7 h [3,4]. In a study conducted by Hagberg et al. [5], where they assessed the daily activity of 39 participants with AKA (cause of amputation: 59% trauma, 28% tumor) using activPAL accelerometers placed on both limbs for 7 days, the AKAs, regardless of their activity level (K2 to K4), spent 10.2 ± 1.8 h per day sedentary in the daytime [5].

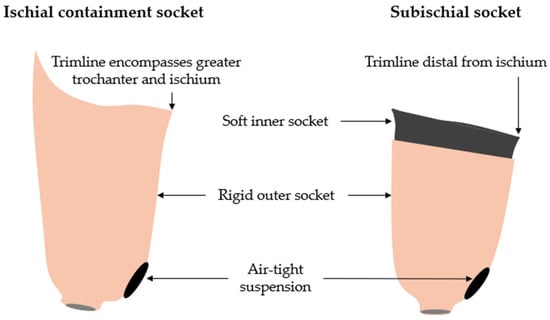

Currently, the clinical standard above-knee socket is the 1980s Ischial containment (IC) socket. This Ischial socket is designed to fit intimately with the ischial ramus and greater trochanter, locking onto the pelvis for greater stability [6,7,8] in the coronal plane (Figure 1). Nevertheless, the proximal brim shape is known to reduce not only the hip motion during walking compared with motion without a socket [9], but it also contributes to socket discomfort, especially in a sitting position.

Figure 1.

Schematic frontal view of the sockets assessed in this study. On the (left), the ischial containment socket with trimline encompassing the greater trochanter and the ischium. On the (right), the subischial socket has a lower trimline and a soft inner socket.

Mohd Hawari et al. [10] showed that only 42% of amputees report being satisfied with their socket [11]. Other studies reported that nearly 68% are dissatisfied with their prosthesis [12]. With the existing body of evidence, the challenge is clear: design a comfortable socket that will support end users in all situations, including sitting and walking.

In recent years, two new shapes of socket have been proposed to release the constraints on the hip by shifting the proximal brim of the socket. The first is the Marlo Anatomical Socket (MAS) [13]. This socket has been designed to maintain greater containment of the ischial ramus medially and to release the anterior and posterior trimlines by lowering the upper limits of the socket. The MAS improves hip range of motion in the sagittal plane, compared with IC sockets [9]. The second is the Northwestern University Flexible Subischial Vacuum Socket (NU-FlexSIV), which has been described in detail by Fatone et al. [14,15]. Their proximal trim lines are subischial and have no contact with the ischial tuberosity. It combines flexible lower socket trim lines with a vacuum-assisted suspension (VAS). The NU-FlexSIV has been reported to improve general comfort and satisfaction compared with the IC socket in participants with AKA and activity level K3/K4 [16]. Brown et al. showed that comfort was improved when sitting but not when walking and running, compared with the IC socket, in four K4 military service members with AKA [17]. A passive suction version of the NU-FlexSIV (without VAS) has been described in detail by Caldwell and Fatone (Figure 1): the Northwestern University Flexible Subischial Suction socket (NU-FlexSIS), which expands the application of the subischial socket, especially to lower activity users [18].

To our knowledge, no studies have assessed the comfort and the daily mobility of people with AKA wearing the NU-FlexSIS socket compared with the IC socket.

Therefore, the purpose of this randomized clinical trial is to compare the comfort in amputees with unilateral or bilateral AKA, regardless of their mobility level, using the IC socket and the NU-FlexSIS socket. A secondary objective is to evaluate whether there is a negative impact on mobility using this new socket. It is hypothesized that the subischial socket, compared with the IC socket, would improve comfort in general (primary outcome) and in different specific daily life situations (secondary outcomes).

2. Materials and Methods

This multicenter prospective research was approved by the national ethics committee CPP Sud Méditerranée II (ID RCB: 2020-A03303-36) and was registered on Clinical Trials: NCT04791163.

2.1. Participants

Participants were screened for inclusion if they:

- -

- Were ≥18 years;

- -

- Had a unilateral or bilateral AKA;

- -

- Were equipped with a definitive IC socket;

- -

- Used a liner regardless of the suspension system;

- -

- Had a residual limb length ≥ 16 cm from the perineum to the limb extremity when wearing the liner;

- -

- Were able to don their prosthesis in a standing position;

- -

- Were able to walk (from d4600 to d4608, according to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—ICF, equivalent to K1–K4).

No limitations were enforced regarding the etiology of the amputation or use of walking aids.

Participants were excluded if they:

- -

- Were a protected person;

- -

- Were a pregnant or breast-feeding woman;

- -

- Had a silicone allergy;

- -

- Had a residual limb that was not stable in volume or infected;

- -

- Had any pathology affecting the sensations or the capacity to don the prosthesis.

2.2. Experimental Design

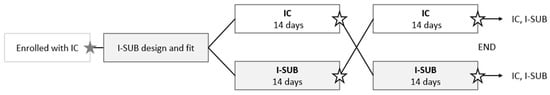

A multicentric prospective, randomized crossover trial was conducted to test the developed hypotheses. Each participant was recruited consecutively by 10 French rehabilitation centers, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Each participant wore both the new custom-fabricated subischial socket (I-SUB) and their current IC socket for at least 14 days before evaluation. The randomization to assign the initial socket was generated by computer (Excel®) by allocation with blocks of six. Blinding of participants, prosthetists, and investigators was not possible, given that the socket shapes were different.

2.3. Intervention

Subischial sockets were made according to the indications of Fatone et al. by trained Certified Prosthetists (CPs). IC sockets consisted of a rigid laminated frame with or without a flexible inner socket using any suspension system. The I-SUB socket, according to the NU-FLEX-SIS method, consisted of «a silicone liner and Flex EVA inner socket, rigid laminated outer socket, and passive vacuum suspension» [14,18]. The participants used their usual prosthetic components (knee and foot) with both sockets.

2.4. Procedure

Written informed consent of the participant, demographic (sex, body mass, height, age), health information (amputation side, time since amputation, amputation etiology), and the prosthetic components (knee, foot) were collected for each enrolled participant. The I-SUB fabrication phase included at least 3 visits: casting, socket fitting control, and definitive socket delivery. If required, further visits were completed to obtain a satisfactory socket fitting. Concurrently, the participant was randomized and assigned to either group A (I-SUB—IC) or group B (IC—I-SUB). Outcomes were assessed for each socket after 14 days of use (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical investigation design:  Randomization

Randomization  Assessment.

Assessment.

Randomization

Randomization  Assessment.

Assessment.

At the end of the study, each participant was asked which socket he or she would like to keep: the IC or the I-SUB socket.

Adverse events that occurred with both sockets were compiled and filed at the end of the study.

2.5. Outcome Measures

Primary outcome was the comfort assessment in general by the Socket Score Comfort (SCS). Secondary outcomes included socket comfort in ADLs (sitting on a rigid chair, sitting in a car, standing, and walking), and mobility assessment by the French version of the Prosthetic Limb Users Survey of Mobility (PLUS-M) questionnaire and by the Two Minute Walk Test (2MWT) (see Supplementary Materials Figure S1).

The Socket Comfort Score (SCS) measures comfort in the socket on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10, where 0 represents the least comfortable socket imaginable and 10 the most comfortable socket imaginable. The SCS is valid, reproducible, and sensitive to change [19]. The minimal detectable change (MDC) at the 90% confidence level has been reported to be 2.73 [20].

The Prosthetic Limb Users Survey of Mobility, Short Form in 12 items (PLUS-M) is a self-administered report instrument for assessing mobility in various daily life situations, specific to lower limb amputees. This questionnaire contains 12 questions on a 5-point scale ranging from “unable to do” to “without any difficulty” [20]. This questionnaire was rigorously developed using the methods of Reeve et al. [21]. The PLUS-M T-score is obtained with the authors’ guideline table [22]. The T-Score is a standardized score with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The higher the score, the higher the level of mobility. Moreover, normative data are available, enabling comparison of a participant’s score with those reported for the development of the sample or by its subgroups (by level, etiology of amputation, sex, age…). Note: Psychometric properties have a scale between good and excellent (reproducibility: ICC > 0.9). The MDC has been set at 4.5. The French version shows excellent psychometric properties, with excellent reproducibility, and no ceiling or floor effects [23]. The French version 1.2 was used [24].

The Two Minute Walk Test (2MWT) is a general gait test, a mobility capacity test easily conducted in clinical practice. This test has been frequently used to assess patients with lower limb amputations [5,25,26]. As the test instructions state, the participant walks for 2 min as far as possible with or without their usual walking aids. The distance covered at the end of 2 min was reported. The walk test was performed once in an indoor corridor at each assessment session. Psychometric properties have been calculated with a sample of 44 lower limb amputees (with below- and above-knee amputation), with a mean age in the mid-sixties, with good reproducibility (ICC = 0.83). The MDC was set at 34.3 m [27].

2.6. Sample Size Determination

The primary outcome was the SCS; the sample size calculation was therefore based on this outcome. Data from a previous study showed an effect size of 1 for the general SCS at 7 weeks [16]. Using the G*Power 3.1.9.7 program, and considering a type one error of 0.05, a power of 0.90 and a one-tailed paired t-test, this effect size yields a minimum sample size of 11 participants. Considering (i) a more heterogeneous population than Fatone et al. [16], (ii) potential withdrawals, and (iii) eleven potential investigation sites easily recruiting 2 to 3 participants each, we chose a total sample size of 25 participants.

2.7. Data Analysis

Randomization was run at the inclusion, to define whether participants would be tested first with their IC or I-SUB socket. Participant demographics are presented using descriptive statistics.

Analysis of both primary and secondary outcomes was first conducted patient-wise. The intra-individual difference between scores reported with each socket was analyzed, and the number of participants with a difference exceeding the MDC in either direction is reported. Second, at the group level, the distribution of the differences between scores was determined through visual inspection of histograms and Shapiro–Wilk tests.

With the primary outcome being the SCS, we hypothesized that the comfort score would increase with I-SUB compared with IC. This study has a crossover design with two groups testing sockets in a different order. To test our hypothesis while controlling for the testing order effect, we performed a two-way repeated-measure ANOVA with one intra-individual factor, “socket”, and one inter-individual factor, “group”, on each comfort score.

The secondary outcomes of this study were focused on patient mobility using the 2MWT performance score and the PLUS-M T-score. Our hypothesis was that mobility would not be different with both sockets. To check the absence of differences, a two-tailed t-test for paired samples was used if the differences on the 2MWT and PLUS-M were normally distributed. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test would be used otherwise.

Three significance levels are reported: *: α ≤ 0.05, **: α ≤ 0.01, and ***: α ≤ 0.001. The above statistical analysis is completed by an effect size calculation using Cohen’s d. Participants with missing data were considered in the analysis according to the last observation carried forward technique. This conservative technique is an approach that aims to show significant statistical differences.

3. Results

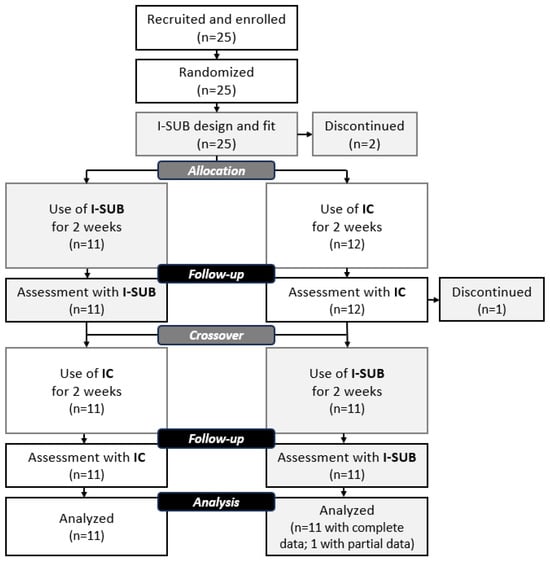

From April 2021 to July 2022, 25 (n = 25) participants were included by Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PMR) physicians in accordance with the inclusion and non-inclusion criteria of the protocol. Two (n = 2) participants withdrew before any data collection. Characteristics of the 23 (n = 23) participants with full or partial data are detailed in Table 1 (20 males and 3 females; mean age 60.1 ± 11.9yo; mean height 1.75 ± 0.06 m; mean weight 79.0 ± 12.0 kg; amputation because of trauma (13), vascular (6), cancer (2), infection (2); mean duration since amputation 15.3 ± 12.9 y). Participants were classified, according to the ICF, as d4600 (n = 1) (Moving around within the home), d4601 (n = 2), d4602 (n = 10), and d4608 (n = 10) (Moving around in different locations, other specified). One participant (Subject 5) had a bilateral amputation (above-knee AK/below-knee BK). A total of 52% were allocated to start with the IC socket.

Table 1.

Participants’ characteristics.

Of the 23 participants, 1 withdrew after 1 evaluation. Among the 22 participants completing the study, we collected incomplete (n = 1) or complete (n = 21) data. Data analysis was performed with the data of 23 participants for comfort (including 1 participant with last observation carried forward), 22 participants for 2MWT (including 1 participant with last observation carried forward), and 22 participants for PLUS-M (Figure 3) (see Supplementary Materials Table S1 for results dataset).

Figure 3.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram.

3.1. Comfort

The intra-individual general comfort score results show that for 22 participants with complete data, 17 participants (77%) increased their SCS with the I-SUB compared with the IC socket, 7 of whom increased their SCS more than the MDC; 1 participant decreased their SCS more than the MDC.

Group analysis of the comfort score: The Shapiro–Wilk normality test did not reject the normality hypothesis on the differences between sockets (p = 0.72); the Socket Comfort Score was significantly improved by +1.8(2.5) (p = 0.008; d = 0.70) with the I-SUB socket compared with the IC socket.

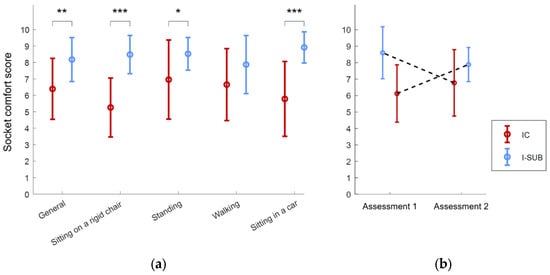

Comfort in ADLs was statistically improved in all situations with I-SUB compared with IC, except during walking, where the improvement did not reach statistical significance (mean ± standard deviation, p-value, Cohen’s d effect size) (Figure 4a, Table 2):

Figure 4.

Socket comfort scores obtained with each socket type (dark red for IC, light blue for I-SUB): (a) SCS for each situation; significance level: * p < 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001; (b) SCS socket × order interaction visualization.

Table 2.

Socket comfort scores—detailed results of the repeated-measure analysis of variance (ANOVA).

- -

- Sitting on a rigid chair: +3.2(2.3) (p < 0.001; d = 1.38);

- -

- Sitting in a car: +3.1(2.7) (p = 0.001; d = 1.13);

- -

- Standing: +1.5(2.7) (p = 0.027; d = 0.57);

- -

- Walking: +1.2(3.1) (p = 0.212; d = 0.38).

The repeated-measure analysis of variance performed on the general SCS also showed significant differences between sockets (p = 0.004) and ruled out the presence of a randomization group effect (p = 0.105), as well as the interaction effect (p = 0.951) (Figure 4b).

3.2. Mobility

Intra-individual results for mobility capacity: the distance walked at the 2MWT was analyzed for 22 participants. In this study, 12 participants increased their walking distance, and 1 participant increased their walking distance at 2MWT more than the MDC with I-SUB; no participant reduced their distance more than the MDC. Group analysis: the Shapiro–Wilk Normality test did not reject the hypothesis for data normal distribution; the mean score was improved (+3.8(15.9)) but showed no statistical difference (p = 0.27).

Intra-individual results for mobility: T-scores obtained at the PLUS-M questionnaire were analyzed for 22 participants. In total, seven participants increased more than the MDC, and three decreased more than the MDC. Group analysis: The Shapiro–Wilk Normality test applied to the score difference between I-SUB and IC sockets did not reject the normality hypothesis (p = 0.48). The mean T-score was improved with the I-SUB socket compared with the IC socket (+1.3(7.9)) but showed no statistical difference (p = 0.22).

3.3. Adverse Events

Reported adverse events were phlyctene (2 with I-SUB), discomfort or pain in the residual limb (4 with I-SUB), low back pain (1 with IC), sciatic neuroma (1 with IC), fall due to new shoes (when wearing the I-SUB), volume loss (when wearing IC), and donning difficulties with I-SUB. These difficulties were partly due to the increased tightening inherent in the I-SUB socket design. Another challenge was the need to don the socket in an upright standing position; allowing the patient to use a support for stabilization helped mitigate this issue. A further concern was ensuring correct transverse angulation during donning; matching marks on the liner and the socket could assist users in achieving proper rotational alignment. No serious adverse event was reported.

3.4. Preference

At the end of the study, 18 of 22 participants (82%) chose to keep the I-SUB socket for their everyday prosthesis.

4. Discussion

The key finding from this study is that the subischial socket significantly improved users’ comfort compared with ischial containment, with equivalent mobility results.

Demographic data (mean age and mobility levels) showed that the participants of this clinical investigation make up a representative panel of the lower limb amputee population.

Despite a sample of 25 randomized participants, which could be considered small, this is the largest AKA sample in a crossover study with complete data (n = 21) evaluating sockets [16,28,29,30,31,32].

Of the 25 included participants, only three were women, accounting for 12% of our population. In contrast, women account for 35% of the amputee population [33]. There is therefore a need for more gender-balanced populations in future research. Although no major biomechanical differences are expected between women and men, female participants may derive additional benefits from the I-SUB socket design: the I-SUB tends to be less bulky—particularly proximally—and, by releasing the perineal region, facilitates access for intimate hygiene.

For the first time, comfort during ADLs was assessed for a subischial socket with passive suction; in recent years, it had only been studied on subischial socket designs with vacuum-assisted suspension [16,17,32]. The data show comfort was greatly improved with a subischial design without vacuum-assisted suspension.

Comfort was significantly improved with I-SUB in general and in three specific situations: namely, sitting on a rigid chair, sitting in a car, and standing. One can notice that the effect sizes for comfort scores when sitting were above 0.8, described as large by Cohen [34] and Fritz [35]. Considering the long time spent in a seated position [3,4,5], we can clearly predict an increased comfort for those AKA socket users. In contrast, during walking, SCS was not significantly improved. The IC socket type was specifically designed to provide comfortable weight bearing during walking [6], which may explain the absence of a statistically significant difference.

In this investigation, no rehabilitation training was proposed to participants. Although the exteroception sensations were altered by the new socket shape, participants naturally adapted to the socket change, as shown by mobility assessment results (2-min walk test and PLUS-M questionnaire). The data show there is no difference in mobility capacity and performance of participants with one socket versus the other. The T-score results with the IC or the I-SUB socket were 51.2 ± 9.6 and 52.6 ± 8.9, respectively, which is close to the standard data: 50 ± 10 (PLUS-M scoring guide). Today, Physical Therapists have this open question in the case of recently amputated people: how to rehabilitate the patient fitted with I-SUB, with specific focus on the exteroception due to changes in the socket design?

Things to consider: The duration of using one or the other socket before evaluation was discussed with the investigators and was chosen as a balance of being long enough to become used to the socket change in activities of daily living and short enough to avoid side events such as residual limb shape change or subjects’ dropouts. Two weeks may be considered a short acclimation time. Despite this short period of use before scoring, the results are pretty similar to those of Fatone et al. 2021 [16], where comfort was scored at 7 weeks: the mean SCS was 7.0(1.7) for the IC socket and 8.4(1.1) for the NU-FlexSIV socket. Here at 2 weeks, the mean SCS was 6.4(1.9) for the IC socket and 8.2(1.3) for the I-SUB socket. Supporting the immediate effect of socket change on comfort scoring [19], Fatone et al. noted, in 2014 [36], that SCS could be used by clinicians to evaluate the immediate effect of socket-related adjustments in preference to clinical measures of gait.

Reported adverse events are typical of new socket fittings and the first weeks of use.

4.1. Study Limitations

Data processing: It should be noted that the ANOVA residuals were not normally distributed (p-value of Shapiro–Wilk test: 0.0085) and the variances of the groups were barely equal (p-value of Levene test: 0.2050). Nevertheless, we chose to use an ANOVA to obtain insight into the randomization group effect because (i) ANOVA is known to be robust against violation of the normality assumption, and (ii) there is a lack of a non-parametric alternative for our specific situation (two factors: one within and one between unbalanced groups).

Population: The few women (n = 3) included in this study is a limitation.

Outcome measures: The focus of this study was on ADL assessment; biomechanical parameters were not studied here. Full body kinematics completed with electromyography on the lower limb and low back would be an interesting recording to better understand the muscle groups’ performance on ADLs, such as walking, standing, or squatting. Pelvic tilt when sitting would also be of interest. Collecting these data would aid in exploring compensatory mechanisms related to this subischial design.

4.2. Longer-Term Analysis

The I-SUB design process is clearly different from the IC design, molding the residual limb in a seated position with positive model rectification requiring only volume reduction. This reduction in the volume of the positive model leads to a higher level of compression, which might have a long-term impact on residual limb shape. In a case study, Fatone et al. reported, in 2018 [37], that in a participant wearing a subischial socket for a decade, a 31% increase in socket volume was found despite the compressive effect. In addition, the participant increased the proximal circumference where most of the remaining muscle is located, more than the distal circumference (16% and 9% increase, respectively). Although limited to this specific participant, these results give insight into the possible positive long-term effects of subischial sockets, providing the ability for users to actively walk and avoid the atrophy typically observed in other socket designs.

5. Conclusions

This study shows that, after a 2-week acclimation period, AKA prosthetic users report improved daily life comfort with the I-SUB socket compared with the IC socket without negatively impacting their prosthetic mobility.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/prosthesis8010005/s1, Figure S1: Assessment; Table S1: Results dataset.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and I.P.; methodology, L.C., I.P., I.L. and R.K.; validation, L.C.; formal analysis, C.D.; investigation, I.L., R.K., P.B., G.B., M.D.C., E.E., N.F., C.P., S.R., G.R., Y.R. and M.T.-P.; data curation, C.D.; writing—original draft, I.L., L.C. and C.D.; writing—review and editing, I.P., R.K., P.B., G.B., M.D.C., E.E., N.F., C.P., S.R., G.R., Y.R. and M.T.-P.; visualization, L.C. and C.D.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the national ethics committee CPP Sud Méditerranée II (ID RCB: 2020-A03303-36, approved on 2 February 2021); it was registered on Clinical Trials (NCT04791163).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to commencement.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants, investigators, and collaborators for their cooperation in this study, and PROTEOR for sponsoring this clinical investigation. Gen AI was not used by authors.

Conflicts of Interest

C.D., I.P., and L.C. are employed by the sponsor. Other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 2MWT | Two Minute Walk Test |

| IC | Ischial containment |

| I-SUB | Subischial |

| MDC | Minimum detectable change at 90% confidence level |

| NU-FlexSIS | Northwestern University Flexible Subischial Suction socket |

| NU-FlexSIV | Northwestern University Flexible Subischial Vacuum Socket |

| PLUS-M | Prosthetic Limb Users Survey of Mobility |

| PMR | Physical medicine and rehabilitation |

| RL | Residual limb |

| SCS | Socket Score Comfort |

| VAS | Vacuum-assisted suspension |

References

- ATIH Data for 2022. Available online: https://www.atih.sante.fr/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Sanders, J.E.; Daly, C.H. Normal and shear stresses on a residual limb in a prosthetic socket during ambulation: Comparison of finite element results with experimental measurements. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 1993, 30, 191–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman, A.; Ainsworth, B.; Sallis, J.; Hagströmer, M.; Craig, C.; Bull, F.; Pratt, M.; Venugopal, K.; Chau, J.; Sjöström, M.; et al. The Descriptive Epidemiology of Sitting: A 20-Country Comparison Using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Am. J. Prev. Med. 2011, 41, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jans, M.; Proper, K.; Hildebrandt, V. Sedentary Behavior in Dutch Workers: Differences Between Occupations and Business Sectors. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2007, 33, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagberg, K.; Zügner, R.; Thomsen, P.; Tranberg, R. Daily Activity of Individuals with an Amputation Above the Knee as Recorded from the Nonamputated Limb and the Prosthetic Limb. J. Meas. Phys. Behav. 2023, 6, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabolich, J. Contoured adduction trochanteric-controlled alignment method (CAT-CAM). Clin. Prosthet. Orthot. 1985, 9, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyt, C.; Littig, D.; Lundt, J.; Staats, T. The UCLA CAT-CAM Above-Knee Socket, 3rd ed.; UCLA Prosthetics Education and Research Program: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Pritham, C.H. Biomechanics and shape of the above-knee socket considered in light of the ischial containment concept. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 1990, 14, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klotz, R.; Colobert, B.; Botino, M.; Permentiers, I. Influence of different types of sockets on the range of motion of the hip joint by the transfemoral amputee. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2011, 54, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Hawari, N.; Jawaid, M.; Md Tahir, P.; Azmeer, R.A. Case study: Survey of patient satisfaction with prosthesis quality and design among below-knee prosthetic leg socket users. Disabil. Rehabil. Assist. Technol. 2017, 12, 868–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boonstra, A.M.; Fidler, V.; Eisma, W.H. Walking speed of normal subjects and amputees: Aspects of validity of gait analysis. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 1993, 17, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillingham, T.; Pezzin, L.; MacKenzie, E. Limb amputations and limb deficiencies: Epidemiology and recent trends in the United States. South. Med. J. 2001, 95, 875–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairley, M. M.A.S. Socket: A Transfemoral Revolution. O P Edge. 2004. Available online: https://opedge.com/m-a-s-socket-a-transfemoral-revolution/ (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Fatone, S.; Caldwell, R. Northwestern University Flexible Subischial Vacuum Socket for persons with transfemoral amputation: Part 1 description of technique. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2017, 41, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatone, S.; Johnson, W.; Tran, L.; Tucker, K.; Mowrer, C.; Caldwell, R. Quantification of rectifications for Northwestern University Flexible Sub-Ischial Vacuum (NU-FlexSIV) Socket. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2017, 41, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatone, S.; Caldwell, R.; Angelico, J.; Stine, R.; Kim, K.Y.; Gard, S.; Oros, M. Comparison of Ischial Containment and Subischial Sockets on Comfort, Function, Quality of Life, and Satisfaction with Device in Persons with Unilateral Transfemoral Amputation: A Randomized Crossover Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2021, 102, 2063–2073.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, S.; Russell Esposito, E.; Ikeda, A.; Wilken, J.; Fatone, S. Evaluation of NU-FlexSIV Socket performance for military service members with transfemoral amputation. US Army Med. Dep. J. 2018, 2–18, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, R.; Fatone, S. Technique modifications for a suction suspension version of the Northwestern University Flexible Sub-Ischial Vacuum socket: The Northwestern University Flexible Sub-Ischial Suction socket. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2019, 43, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanspal, R.; Fisher, K.; Nieveen, R. Prosthetic socket fit comfort score. Disabil. Rehabil. 2003, 25, 1278–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.B.; Morgan, J.S.; Askew, R.; Salem, R. Psychometric evaluation of self- report outcome measures for prosthetic applications. J. Rehab. Res. Dev. 2016, 53, 797–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeve, B.; Hays, R.; Bjorner, J.; Cook, K.; Crane, P.; Teresi, J.; Thissen, D.; Revicki, D.; Weiss, D.; Hambleton, R.; et al. Psychometric Evaluation and Calibration of Health-Related Quality of Life Item Banks: Plans for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS). Med. Care 2007, 45, S22–S31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgan, S.J.; Amtmann, D.; Abrahamson, D.C.; Kajlich, A.J.; Hafner, B.J. Use of cognitive interviews in the development of the PLUS-M item bank. Qual. Life Res. 2014, 23, 1767–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzios, C.; Loiret, I.; Luthi, F.; Leger, B.; Le Carre, J.; Saubade, M.; Muff, G.; Benaim, C. Transcultural adaptation and validation of a French version of the Prosthetic Limb Users Survey of Mobility 12-item Short-Form (PLUS-M/FC-12) in active amputees. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2019, 62, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prosthetic Limb Users Survey of Mobility (PLUS-M™) Version 1.2 Short Forms Users Guide. 16 September 2022. Available online: http://www.plus-m.org (accessed on 8 August 2024).

- Miller, M.; Cook, P.; Kline, P.; Anderson, C.; Stevens-Lapsley, J.; Christiansen, C. Physical Function and Pre-Amputation Characteristics Explain Daily Step Count after Dysvascular Amputation. PMR 2019, 11, 1050–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaunaurd, I.; Kristal, A.; Horn, A.; Krueger, C.; Muro, O.; Rosenberg, A.; Gruben, K.; Kirk-Sanchez, N.; Pasquina, P.; Gailey, R. The Utility of the 2-Minute Walk Test as a Measure of Mobility in People with Lower Limb Amputation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnik, L.; Borgia, M. Reliability of outcome measures for people with lower-limb amputations: Distinguishing true change from statistical error. Phys. Ther. 2011, 91, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maikos, J.T.; Chomack, J.M.; Loan, J.P.; Bradley, K.M.; D’Andrea, S.E. Effects of Prosthetic Socket Design on Residual Femur Motion Using Dynamic Stereo X-Ray-A Preliminary Analysis. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 10, 697651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, J.T.; Miro, R.M.; Ho, L.T.; Porter, M.R.; Lura, D.J.; Carey, S.L.; Lunseth, P.; Swanson, A.E.; Highsmith, M.J. Effect of transfemoral prosthetic socket interface design on gait, balance, mobility, and preference: A randomized clinical trial. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2021, 45, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahle, J.; Miro, R.M.; Ho, L.T.; Porter, M.; Lura, D.J.; Carey, S.L.; Lunseth, P.; Highsmith, J.; Highsmith, M.J. The effect of the transfemoral prosthetic socket interface designs on skeletal motion and socket comfort: A randomized clinical trial. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2020, 44, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillingham, T.R.; Kenia, J.L.; Shofer, F.S.; Marschalek, J.S. A Prospective Assessment of an Adjustable, Immediate Fit, Subischial Transfemoral Prosthesis. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. Dev. 2022, 4, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahle, J.T.; Highsmith, M.J. Transfemoral sockets with vacuum-assisted suspension comparison of hip kinematics, socket position, contact pressure, and preference: Ischial containment versus brimless. J. Rehabil. Res. 2013, 50, 1241–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miro, R.; Hanson, A.; Randolph, B.; Highsmith, J. Prosthetic, functional, and clinical outcomes among female amputees with limb loss: A systematic review of the literature. Technol. Innov. 2025, 24, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, C.O.; Morris, P.E.; Richler, J.J. Effect size estimates: Current use, calculations, and interpretation. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012, 141, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatone, S.; Dillon, M.; Stine, R.; Tillges, R. Coronal plane socket stability during gait in persons with unilateral transfemoral amputation: Pilot study. J. Rehabil. Res. Dev. 2014, 51, 1217–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fatone, S.; Yohay, J.; Caldwell, R. Change in residual limb size over time in the NU-FlexSIV Socket: A case study. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2018, 42, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.