Bactericidal Titanium Oxide Nanopillars for Intersomatic Spine Screws

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Surface Characterization

2.2.1. Morphology and Roughness

2.2.2. Wettability and Surface Energy

2.3. Hydrogen Quantification

2.4. Mechanical Properties

2.5. Corrosion Resistance

- Open circuit potential (EOCP), corrosion potential (Ecorr), and corrosion current density (icorr), which were recorded during the tests.

- Open circuit potential (EOCP): the potential of an electrode measured relative to a reference electrode when no current flows to or from the material.

- Corrosion potential (Ecorr): the potential determined at the intersection point where the total oxidation rate equals the total reduction rate.

- Corrosion current density (icorr): the corrosion current divided by the electrode surface area, representing the anodic component of the current flowing at Ecorr.

- Polarization resistance (Rp): an indicator of the absolute corrosion rate, obtained by scanning a narrow potential range around Ecorr and relating the slope of the current–potential curve to icorr.

- Corrosion rate (Vc): the material loss per year, expressed as a reduction in thickness.

2.6. Ion Release

2.7. Bacterial Adhesion

2.8. Osteoblast Cell Culture

2.9. In Vivo Tests

2.9.1. Animals

2.9.2. Implants and Surgical Procedure

2.9.3. Histological and Histomorphometric Analysis

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Surface Characterization

3.2. Hydrogen Incorporation

3.3. Mechanical Properties

3.4. Corrosion Resistance

3.5. Ion Release

3.6. Bacterial Adhesion

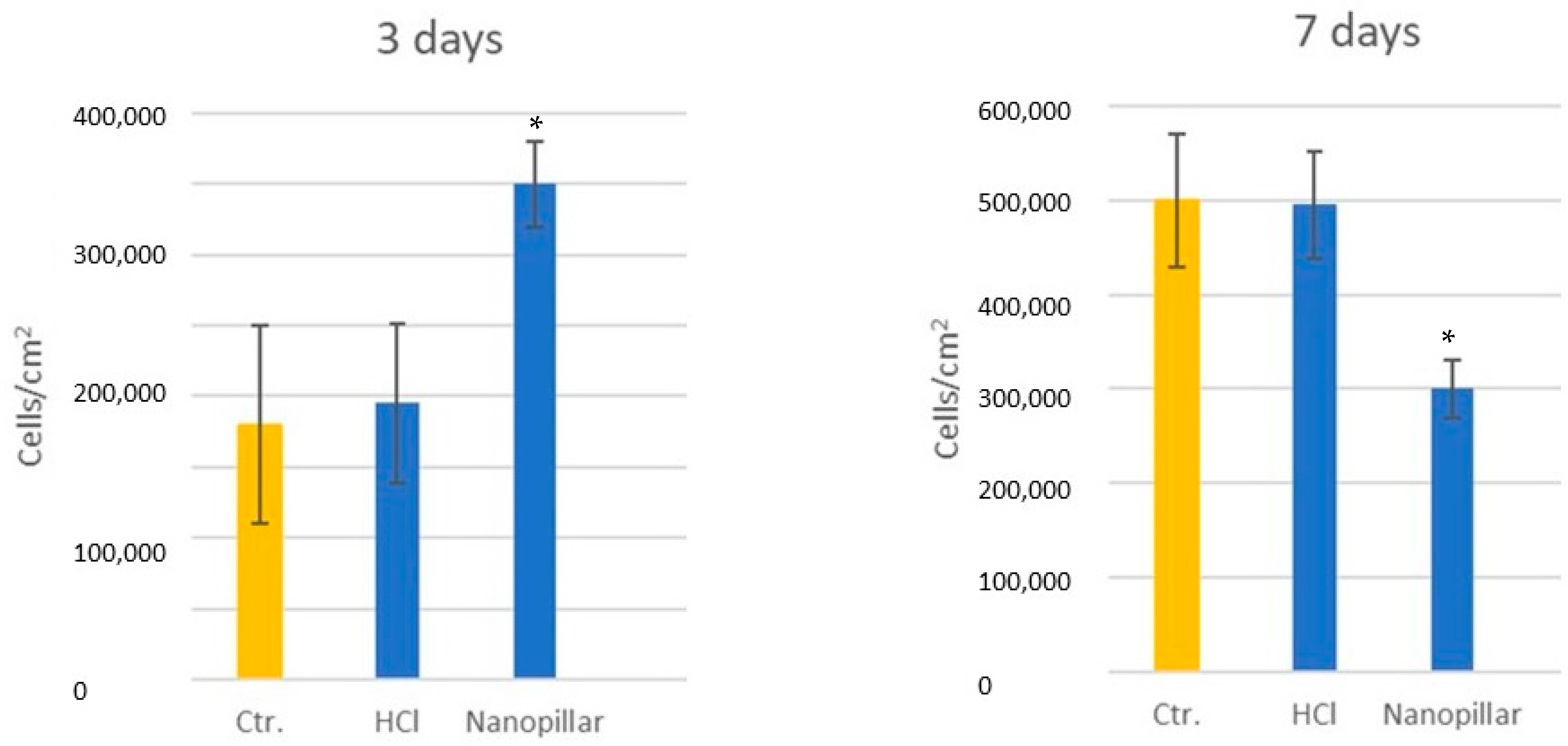

3.7. Osteoblast Viability and Differentiation

3.8. In Vivo Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zmistowski, B.; Karam, J.A.; Durinka, J.B.; Casper, D.S.; Parvizi, J. Periprosthetic joint infection increases the risk of one-year mortality. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2013, 95, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakore, R.V.; Greenberg, S.E.; Shi, H.; Foxx, A.M.; Francois, E.L.; Prablek, M.A.; Nwosu, S.K.; Archer, K.R.; Ehrenfeld, J.M.; Obremskey, W.T.; et al. Surgical site infection in orthopedic trauma: A case-control study evaluating risk factors and cost. J. Clin. Orthop. Trauma 2015, 6, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Fairen, M.; Torres, A.; Menzie, A.; Hernandez-Vaquero, D.; Fernandez-Carreira, J.M.; Murcia-Mazon, A.; Guerado, E.; Merzthal, L. Economical analysis on prophylaxis, diagnosis, and treatment of periprosthetic infections. Open Orthop. J. 2013, 7, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, Q.; Li, J.; Lin, J.; Li, D.; Wang, B.; Meng, H.; Wang, Q.; Su, N.; Yang, Y. Risk Factors for Surgical Site Infection After Spinal Surgery: A Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2016, 95, 507–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalfas, F.; Severi, P.; Scudieri, C. Infection with Spinal Instrumentation: A 20-Year, Single-Institution Experience with Review of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, Prevention, and Management. Asian J. Neurosurg. 2019, 14, 1181–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, D.G.; O’Mahony, A.M.; Culligan, E.P.; O’Driscoll, C.M.; Ryan, K.B. Strategies to Mitigate and Treat Orthopaedic Device-Associated Infections. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsemakers, W.J.; Kuehl, R.; Moriarty, T.F.; Richards, R.G.; Verhofstad, M.H.J.; Borens, O.; Kates, S.; Morgenstern, M. Infection after fracture fixation: Current surgical and microbiological concepts. Injury 2018, 49, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirisi, L.; Pennestrì, F.; Viganò, M.; Banfi, G. Prevalence and burden of orthopaedic implantable-device infections in Italy: A hospital-based national study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wang, Q.; Hamushan, M.; Yu, J.; Jiang, F.; Li, M.; Guo, G.; Tang, J.; Han, P.; Shen, H. Trends in microbiological epidemiology of orthopedic infections: A large retrospective study from 2008 to 2021. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, B.T.; Connelly, D.; Rocca, M.; Mascarenhas, D.; Huang, Y.; Maceroli, M.A.; Gage, M.J.; Joshi, M.; Castillo, R.C.; O’Toole, R.V. A Predictive Score for Determining Risk of Surgical Site Infection After Orthopaedic Trauma Surgery. J. Orthop. Trauma 2019, 33, 506–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanaro, L.; Speziale, P.; Campoccia, D.; Ravaioli, S.; Cangini, I.; Pietrocola, G.; Giannini, S.; Arciola, C.R. Scenery of Staphylococcus implant infections in orthopedics. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 1329–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerli, W.; Moser, C. Pathogenesis and treatment concepts of orthopaedic biofilm infections. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2012, 65, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhou, J.; Qian, Y.; Zhao, L. Antibacterial coatings on orthopedic implants. Mater. Today Bio 2023, 19, 100586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Thian, E.S.; Wang, M.; Wang, Z.; Ren, L. Surface Design for Antibacterial Materials: From Fundamentals to Advanced Strategies. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2100368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Attarilar, S.; Wang, C.; Tamaddon, M.; Yang, C.; Xie, K.; Yao, J.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; et al. Nano-Modified Titanium Implant Materials: A Way Toward Improved Antibacterial Properties. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 576969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wu, Z.; Xu, K.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, H.; Li, X.; Chen, J. Multifunctional Coatings of Titanium Implants Toward Promoting Osseointegration and Preventing Infection: Recent Developments. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 783816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uneputty, A.; Dávila-Lezama, A.; Garibo, D.; Oknianska, A.; Bogdanchikova, N.; Hernández-Sánchez, J.F.; Susarrey-Arce, A. Strategies applied to modify structured and smooth surfaces: A step closer to reduce bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Colloids Interface Sci. Commun. 2022, 46, 100560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, M.; Mantovani, D.; Rosei, F. Antibacterial Coatings: Challenges, Perspectives, and Opportunities. Trends Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 637–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, C.D.; Singh, S.; Afara, I.O.; Wolff, A.; Tesfamichael, T.; Ostrikov, K.; Oloyede, A. Bactericidal Effects of Natural Nanotopography of Dragonfly Wing on Escherichia coli. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 6746–6760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassous, N.J.; Jones, C.L.; Webster, T.J. 3-D printed Ti-6Al-4V scaffolds for supporting osteoblast and restricting bacterial functions without using drugs: Predictive equations and experiments. Acta Biomater. 2019, 96, 662–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.J.P. The use of nanoscale topography to modulate the dynamics of adhesion formation in primary osteoblasts and ERK/MAPK signaling in STRO-1+ enriched skeletal stem cells. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 5094–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Moruno, C.; Garrido, B.; Rodriguez, D.; Ruperez, E.; Gil, F.J. Biofunctionalization strategies on tantalum-based materials for osseointegrative applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Guillem-Marti, J.; Sevilla, P.; Manero, J.M.; Gil, F.J.; Rodriguez, D. Anhydride-functional silane immobilized onto titanium surfaces induces osteoblast cell differentiation and reduces bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 59, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Manzanares-Céspedes, M.C.; Sevilla, P.; Nart, J.; Manzanares, N.; Manero, J.M.; Gil, F.J.; Boyd, S.K.; Rodríguez, D. Evaluation of bone loss in antibacterial coated dental implants: An experimental study in dogs. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 69, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz, N.; Gil, J.; Punset, M.; Manero, J.M.; Tondela, J.P.; Verdeguer, P.; Aparicio, C.; Rúperez, E. Relevant Aspects of Piranha Passivation in Ti6Al4V Alloy Dental Meshes. Coatings 2022, 12, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathy, A.; Sen, P.; Su, B.; Briscoe, W.H. Natural and bioinspired nanostructured bactericidal surfaces. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 248, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raphel, J.; Holodniy, M.; Goodman, S.B.; Heilshorn, S.C. Multifunctional coatings to simultaneously promote osseointegration and prevent infection of orthopaedic implants. Biomaterials 2016, 84, 301–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhorukova, I.V.; Sheveyko, A.N.; Kiryukhantsev-Korneev, P.V.; Zhitnyak, I.Y.; Gloushankova, N.A.; Denisenko, E.A.; Filippovich, S.Y.; Ignatov, S.G.; Shtansky, D.V. Toward bioactive yet antibacterial surfaces. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2015, 135, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango-Santander, S. Bioinspired Topographic Surface Modification of Biomaterials. Materials 2022, 15, 2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelleher, S.M.; Habimana, O.; Lawler, J.; O’Reilly, B.; Daniels, S.; Casey, E.; Cowley, A. Cicada Wing Surface Topography: An Investigation into the Bactericidal Properties of Nanostructural Features. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 14966–14974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Phillips, K.S.; Gu, H.; Kazemzadeh-Narbat, M.; Ren, D. How microbes read the map: Effects of implant topography on bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation. Biomaterials 2021, 28, 120595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punset, M.; Villarrasa, J.; Nart, J.; Manero, J.M.; Bosch, B.; Padrós, R.; Gil, F.J. Citric acid passivation of titanium dental implants for minimizing bacterial colonization impact. Coatings 2021, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, C.; Manero, J.M.; Conde, F.; Pegueroles, M.; Planell, J.A.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Gil, F.J. Acceleration of apatite nucleation on microrough bioactive titanium for bone-replacing implants. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2007, 82, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Gallardo, M.; Eckhard, U.; Delgado, L.M.; de Roo Puente, Y.J.D.; Hoyos-Nogués, M.; Gil, F.J.; Perez, R.A. Antibacterial approaches in tissue engineering using metal ions and nanoparticles: From mechanisms to applications. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 4470–4490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Xiu, P.; Li, M.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, S.; Zheng, Y.; Xi, T.; Cai, H.; et al. Bioinspired anchoring AgNPs onto micro-nanoporous TiO2 orthopedic coatings: Trap-killing of bacteria, surface-regulated osteoblast functions and host responses. Biomaterials 2016, 75, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio, C.; Gil, F.J.; Fonseca, C.; Barbosa, M.; Planell, J.A. Corrosion behaviour of commercially pure titanium shot blasted with different materials and sizes of shot blasted with different materials and sizes of shot particles for dental implant applications. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 263–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, F.J.; Planell, J.A. Aplicaciones biomédicas del titanio v sus aleaciones. Biomecánica 1993, 1, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonardis, D.; Garg, A.K.; Pecora, G.E. Osseointegration of Rough Acid-Etched Titanium Implants: 5-Year Follow-up of 100 Minimatic Implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 1994, 14, 384–391. [Google Scholar]

- Barewal, R.M.; Oates, T.W.; Meredith, N.; Cochran, D.L. Resonance frequency measurement of implant stability in vivo on implants with a sandblasted and acid-etched surface. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2003, 18, 641–651. [Google Scholar]

- Stubinger, S.; Etter, C.; Miskiewicz, M.; Homann, F.; Saldamli, B.; Wieland, M.; Sader, R. Surface alterations of polished and sandblasted and acid-etched titanium implants after Er:YAG, carbon dioxide, and diode laser irradiation. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2010, 25, 104–111. [Google Scholar]

- Buxadera-Palomero, J.; Calvo, C.; Torrent-Camarero, S.; Gil, F.J.; Mas-Moruno, C.; Canal, C.; Rodríguez, D. Biofunctional polyethylene glycol coatings on titanium: An in vitro-based comparison of functionalization methods. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 152, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferraris, S.; Venturello, A.; Miola, M.; Cochis, A.; Rimondini, L.; Spriano, S. Antibacterial and bioactive nanostructured titanium surfaces for bone integration. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 311, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Tian, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, Y.; You, J.; Yang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Chu, S. Overview of strategies to improve the antibacterial property of dental implants. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1267128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, W.; Fang, F. Overview of Antibacterial Strategies of Dental Implant Materials for the Prevention of Peri-Implantitis. Bioconjugate Chem. 2021, 32, 627–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Qi, M.; Sun, X.; Weir, M.D.; Tay, F.R.; Oates, T.W.; Dong, B.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, H.H.K. Surface treatments on titanium implants via nanostructured ceria for antibacterial and anti-inflammatory capabilities. Acta Biomater. 2019, 6, 627–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wheelis, S.E.; Gindri, I.M.; Valderrama, P.; Wilson, T.G., Jr.; Huang, J.; Rodrigues, D.C. Effects of decontamination solutions on the surface of titanium: Investigation of surface morphology, composition, and roughness. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosch-Rué, E.; Diez-Tercero, L.; Giordano-Kelhoffer, B.; Delgado, L.M.; Bosch, B.M.; Hoyos-Nogués, M.; Mateos-Timoneda, M.A.; Tran, P.A.; Gil, F.J.; Perez, R.A. Biological Roles and Delivery Strategies for Ions to Promote Osteogenic Induction. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 8, 614545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, R.J. Contact-Angle, Wetting, and Adhesion—A Critical-Review. J. Adh. Sci. Technol. 1992, 6, 1269–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Duan, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, C.; Fu, W. Wettability and biological responses of titanium surface’s biomimetic hexagonal microstructure. J. Biomater. Appl. 2023, 37, 1112–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7438:2016; Flexion Test Metals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

- ISO 14801:2007; Dynamic Fatigue Test for Implants. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- ASTM G31-90; Standard Practice for Laboratory Immersion Corrosion Testing Metals. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; Volume 03.02, pp. 102–109.

- ASTM G61-86; Standard Test Method for Conducting Cyclic Potentiodynamic Polarization Measurements for Localized Corrosion Susceptibility of Iron–Nickel, or Cobalt-Based Alloys. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; Volume 03.02, pp. 231–235.

- ASTM G102-89; Standard Practice for Calculation of Corrosion Rates and Related Information from Electrochemical Measurements. ASTM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992; Volume 03.02, pp. 231–235.

- Aparicio, C.; Padrós, A.; Gil, F.J. In vivo evaluation of micro-rough and bioactive titanium dental implants using histometry and pull-out tests. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2011, 4, 1672–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manero, J.M.; Gil, F.J.; Padrós, E.; Planell, J.A. Applications of environmental scanning electron microscopy (ESEM) in biomaterials field. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2003, 61, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A. Biomedical Applications of Titanium Alloys: A Comprehensive Review. Materials 2023, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegrzyn, J.; Roux, J.P.; Arlot, M.E.; Boutroy, S.; Vilayphiou, N.; Guyen, O.; Delmas, P.D.; Chapurlat, R.; Bouxsein, M.L. Determinants of the mechanical behavior of human lumbar vertebrae after simulated mild fracture. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2011, 26, 739–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, J.P.; Wegrzyn, J.; Boutroy, S.; Bouxsein, M.L.; Hans, D.; Chapurlat, R. The predictive value of trabecular bone score (TBS) on whole lumbar vertebrae mechanics: An ex vivo study. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 2455–2460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perilli, E.; Briggs, A.M.; Kantor, S.; Codrington, J.; Wark, J.D.; Parkinson, I.H.; Fazzalari, N.L. Failure strength of human vertebrae: Prediction using bone mineral density measured by DXA and bone volume by micro-CT. Bone 2012, 50, 1416–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arregui, M.; Latour, F.; Gil, F.J.; Pérez, R.A.; Giner-Tarrida, L.; Delgado, L.M. Ion Release from Dental Implants, Prosthetic Abutments and Crowns under Physiological and Acidic Conditions. Coatings 2021, 11, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robles, D.; Brizuela, A.; Fernández-Domínguez, M.; Gil, J. Corrosion Resistance and Titanium Ion Release of Hybrid Dental Implants. Materials 2023, 16, 3650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afşar, O.; Oltulu, Ç. Evaluation of the cytotoxic effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human embryonic lung cells. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 53, 1648–1657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Zhou, J.; Li, F.; Wang, J.; Chen, M.; Liu, Q. Cytotoxicity, DNA damage, and apoptosis induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2015, 22, 5519–5530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Gavilán, F.; Cerqueira, A.; García-Arnáez, I.; Azkargorta, M.; Elortza, F.; Gurruchaga, M.; Goñi, I.; Suay, J. Proteomic evaluation of human osteoblast responses to titanium implants over time. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2023, 111, 45–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feller, L.; Jadwat, Y.; Khammissa, R.A.; Meyerov, R.; Schechter, I.; Lemmer, J. Cellular responses evoked by different surface characteristics of intraosseous titanium implants. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 171945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.B.; Tasić, Z.Z.; Simonović, A.T.; Petrović, M.; Antonijević, M.M. Corrosion Behavior of Titanium in Simulated Body Solutions with the Addition of Biomolecules. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 12768–12776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Kou, N.; Ye, W.; Wang, S.; Lu, J.; Lu, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, X. Construction and Characterizations of Antibacterial Surfaces Based on Self-Assembled Monolayer of Antimicrobial Peptides (Pac-525) Derivatives on Gold. Coatings 2021, 11, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, B.; Gurruchaga, M.; Ginebra, M.P.; Gil, F.J.; Planell, J.A.; Goñi, I. Influence of the modification of P/L ratio on a new formulation of acrylic bone cement. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Rutherford, S.T.; Silhavy, T.J.; Huang, K.C. Physical properties of the bacterial outer membrane. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2022, 20, 236–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, R.J.; Kasson, P.M. Antibiotic Uptake Across Gram-Negative Outer Membranes: Better Predictions Towards Better Antibiotics. ACS Infect. Dis. 2019, 5, 2096–2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrzyniarz, K.; Kuc-Ciepluch, D.; Lasak, M.; Arabski, M.; Sanchez-Nieves, J.; Ciepluch, K. Dendritic systems for bacterial outer membrane disruption as a method of overcoming bacterial multidrug resistance. Biomater. Sci. 2023, 11, 6421–6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacNair, C.R.; Brown, E.D. Outer Membrane Disruption Overcomes Intrinsic, Acquired, and Spontaneous Antibiotic Resistance. mBio 2020, 11, e01615-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, B.; Ginebra, M.P.; Gil, F.J.; Planell, J.A.; López Bravo, A.; San Román, J. Radiopaque acrylic cements prepared with a new acrylic derivative of iodo-quinoline. Biomaterials 1999, 20, 2047–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velic, A.; Hasan, J.; Li, Z.; Yarlagadda, P.K.D.V. Mechanics of Bacterial Interaction and Death on Nanopatterned Surfaces. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 217–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Al | V | Fe | C | O2 | N2 | H2 | Ti |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.1 | 4.0 | 0.11 | 0.021 | 0.09 | 0.010 | 0.003 | Balance |

| Component | Composition (mM) |

|---|---|

| K2HPO4 | 0.44 |

| KCl | 5.4 |

| CaCl2 | 1.3 |

| Na2HPO4 | 0.25 |

| NaCl | 137 |

| NaHCO3 | 4.2 |

| MgSO4 | 1.0 |

| C6H12O6 | 5.5 |

| EOCP (mV) | Icorr (μA/cm2) | Rp (MW/cm2) | Ecorr (V) | Vc (mm/Year) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | −196 ± 10 | 0.027 ± 0.008 | 2.428 ± 0.390 | −361 ± 14 | 0.233 ± 0.066 |

| HCl | −145 ± 11 | 0.018 ± 0.005 | 2.479 ± 0.083 | −536 ± 39 | 0.176 ± 0.048 |

| nano | −206 ± 27 | 0.046 ± 0.006 | 1.387 ± 0.149 | −440 ± 26 | 0.401 ± 0.047 |

| Surfaces | BIC (%) |

|---|---|

| Control | 40.1 ± 8.6 |

| HCl | 43.8 ± 7.0 |

| Nanopillar | 52.0 ± 5.2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fernández-Fairén, M.; Delgado, L.M.; Roquette, M.; Gil, J. Bactericidal Titanium Oxide Nanopillars for Intersomatic Spine Screws. Prosthesis 2026, 8, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis8010004

Fernández-Fairén M, Delgado LM, Roquette M, Gil J. Bactericidal Titanium Oxide Nanopillars for Intersomatic Spine Screws. Prosthesis. 2026; 8(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis8010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleFernández-Fairén, Mariano, Luis M. Delgado, Matilde Roquette, and Javier Gil. 2026. "Bactericidal Titanium Oxide Nanopillars for Intersomatic Spine Screws" Prosthesis 8, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis8010004

APA StyleFernández-Fairén, M., Delgado, L. M., Roquette, M., & Gil, J. (2026). Bactericidal Titanium Oxide Nanopillars for Intersomatic Spine Screws. Prosthesis, 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/prosthesis8010004