Abstract

Background/Objectives: The rapid evolution of digital technologies has significantly transformed prosthodontic workflows, improving clinical precision, communication, and patient satisfaction. However, the extent to which dental professionals perceive, integrate, and evaluate these technologies remains insufficiently standardized. This study aimed to develop and validate a questionnaire for assessing perceptions, attitudes, perceived advantages, barriers, and future intentions regarding the use of digital technologies in prosthodontic practice. Methods: A cross-sectional survey was conducted among 420 dental professionals (305 dentists and 115 dental technicians) from Northeastern Romania. The 27-item questionnaire, structured on five theoretical dimensions, was distributed online via the Survio platform. Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha, and construct validity was analyzed through Exploratory Factor Analysis (Principal Component Analysis with Varimax rotation). Conclusions: Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients ranged from 0.700 to 0.799 across the five dimensions, indicating acceptable to very good internal reliability. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value (0.646) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity (p < 0.001) confirmed data suitability for factor analysis. The validated questionnaire represents a reliable and conceptually coherent tool for evaluating professional perspectives on digitalization in prosthodontics. Its application can inform educational strategies, guide institutional investments, and support a balanced transition toward integrated digital workflows in clinical and laboratory settings.

1. Introduction

The field of prosthodontics is always changing since digital technologies are growing and becoming more common. Traditional workflows—using elastomeric impressions, stone models, and manual lab work—have always been the basis of prosthetic rehabilitation. These techniques are well-known, reliable, and easy for dentists and dental technicians to use, and they work effectively when performed by someone who knows what they are performing [1]. But they also take a lot of time, depend on the person doing them, and are prone to changes in size or mistakes that happen after several manual stages [2].

Intraoral scanning, additive manufacturing, virtual articulators, and computer-aided design and manufacture (CAD/CAM) have revolutionized the field of prosthodontics, both in the lab and in the clinic. Digital workflows provide many benefits, such as better standardization, more accuracy, less time spent in the clinical chair, and better communication between the doctor, technician, and patient [3,4].

The use of digital visualization tools can facilitate patient participation in treatment planning and, by setting more realistic expectations, increase patient satisfaction [5]. Dental offices have a hard time making the transition to these systems despite their many advantages because of a variety of issues. These problems include high implementation costs, the requirement for ongoing training, software updates, and different levels of access to digital infrastructure in different dental settings [6].

The field of clinical prosthodontics is currently home to both analogue and digital methods. Many factors, including the clinician’s background, the nature of the patient’s condition, their personal preferences, and the resources at their disposal, go into choosing a workflow [7]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand how practitioners view the benefits, drawbacks, and usefulness of these workflows, particularly in light of the dynamic nature of dental practice settings [8].

While scientific literature presents numerous comparisons of clinical outcomes between conventional and digital prosthodontics, there is limited evidence regarding clinicians’ attitudes, perceived competencies, and patterns of integration of digital tools into routine practice [9]. Existing assessments are heterogeneous and often lack standardized, validated instruments for evaluating the perceived role and impact of digital technologies among prosthodontists and general dental practitioners [10,11].

Digital workflows also demonstrate clear clinical advantages in advanced procedures such as immediate implant placement, management of periodontally compromised sockets, and the fabrication of customized healing abutments. Evidence from Menchini-Fabris et al. shows that digitally guided planning and CAD/CAM components improve soft-tissue stability, provisionalization accuracy, and overall treatment predictability [12]. These applications highlight the practical importance of digital competencies and reinforce the relevance of assessing clinicians’ perceptions, barriers, and training needs.

The conceptual structure of the five questionnaire domains was informed by established theoretical models of technology adoption in healthcare and digital dentistry. Specifically, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) provided the foundational constructs—perceived usefulness/performance expectancy and perceived ease of use/effort expectancy—which map directly onto our domains exploring perceived benefits and perceived limitations.

Facilitating conditions within UTAUT correspond to the organizational and infrastructural support necessary for digital workflow integration, while social influence aligns with professional norms and peer-driven attitudes toward adopting emerging dental technologies. Furthermore, behavioral intention, a central component of both TAM and UTAUT, is reflected in our domain assessing readiness and future intention to implement digital tools in clinical practice.

By situating the questionnaire within these well-validated theoretical frameworks, we ensure that the dimensional structure captures not only individual perceptions, but also contextual, behavioral, and organizational determinants that shape digital dentistry adoption in contemporary practice.

In order to evaluate traditional and digital workflows in prosthodontics, this study aims to create and validate a standardized questionnaire. This instrument can help with decision-making in professional training, clinical implementation, and resource management by looking at practitioners’ experience, confidence, perceived benefits, obstacles to adoption, and educational needs. It could also shed light on current trends.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodological framework of this study encompassed the development, administration, and validation of a structured questionnaire designed to assess the perceptions and attitudes of dental professionals regarding digital and conventional technologies in prosthodontic practice. The approach was structured to ensure both the rigor of data collection and the reliability of the measurement instrument.

The study procedures included defining the target population and selection criteria, constructing the questionnaire based on relevant literature, distributing the survey to participants, and applying appropriate statistical methods to evaluate the internal consistency and construct validity of the instrument. Each stage was carried out in accordance with established methodological and ethical standards to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the findings.

2.1. Study Design and Participant Selection

This study employed a cross-sectional survey design. The questionnaire was administered online using the Survio® platform (Brno, Czech Republic), where it remained accessible for a predefined data collection period of four weeks. Participation was open and voluntary, and the survey link was circulated through professional communication channels commonly used by dentists and dental technicians in the Northeastern region of Romania.

The 27 questionnaire items were developed following a multi-step procedure to ensure conceptual relevance and content validity. First, a review of current literature on digital dentistry implementation, clinician acceptance, and technology-related attitudes informed the identification of five theoretical dimensions. Based on these constructs, the authors generated original items that reflected perceived benefits, limitations, behavioral intentions, workflow challenges, and integration attitudes.

Second, the preliminary item pool was evaluated by a panel of five experts (three prosthodontists with experience in digital workflows and two senior dental technicians). The experts assessed item clarity, relevance to each domain, and potential redundancy. Minor wording adjustments were made based on their feedback.

Third, the pre-final version underwent a small pilot test with 12 practitioners (not included in the main study sample) to ensure linguistic clarity and ease of completion. No structural modifications were required, but several items were refined stylistically for improved readability. This structured development process provided the theoretical and practical foundation for subsequent psychometric validation

A larger number of individuals initially accessed the questionnaire; however, only 420 fully completed and valid responses were retained for analysis. Responses in which participants did not complete all items or exited the questionnaire before submission were excluded to ensure data consistency. The final sample consisted of 305 dentists and 115 dental technicians, all actively involved in clinical or laboratory prosthodontic workflows at the time of the study.

2.2. Research Instrument

The research instrument consisted of a structured questionnaire developed based on relevant literature concerning digital workflows in prosthodontics and technology adoption in clinical and laboratory settings.

The questionnaire included a total of 27 items formulated as statements, and respondents indicated their level of agreement using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

To reflect the conceptual framework of the study, the items were organized into five theoretical dimensions: perceptions of digital technologies (5 items), attitude toward conventional technologies (5 items), perceived advantages of digital technologies (5 items), barriers and concerns (7 items), and intentions and future perspectives (5 items).

The phrasing of the items was kept clear and neutral, ensuring accessibility for both dentists and dental technicians. Prior to distribution, the questionnaire was reviewed for clarity, logical coherence, and internal consistency to ensure that respondents could interpret the statements in a uniform manner.

2.3. Questionnaire Distribution

The questionnaire was distributed online using the Survio® platform (Brno, Czech Republic), where it remained accessible for a period of four weeks. The survey link was circulated through professional communication channels commonly used by dentists and dental technicians in the region, including professional social media groups and workplace communication networks.

Participation was open, voluntary, and self-initiated, with respondents choosing to complete the questionnaire at their convenience. At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the purpose of the study, the anonymous nature of the responses, and the confidentiality of the data collected. No personal identifying information was requested at any stage. Submission of the complete questionnaire was considered equivalent to providing informed consent, in accordance with ethical guidelines for online research. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of “Grigore T. Popa” University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Iasi, Romania (Approval No. 668/2025).

2.4. Questionnaire Validation Process

The validation of the questionnaire followed a multi-stage analytical approach aimed at ensuring both the reliability of the instrument and the adequacy of its factorial structure in relation to the theoretical model proposed. The validation process was conducted after data collection, using only the fully completed questionnaires retained in the final sample. The analysis considered the internal consistency of each conceptual dimension, the coherence of the overall scale, and the extent to which the empirical factor structure corresponded to the five dimensions initially defined during instrument development.

- ✓

- Reliability (Internal Consistency)

Internal reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, calculated separately for each of the five dimensions and for the questionnaire as a whole [13]. This analysis examined the degree to which the items within each dimension were consistently measuring the same underlying construct. Interpretation followed established literature criteria, where values ≥ 0.70 indicate good internal consistency and values ≥ 0.80 indicate high internal reliability. Items were also examined for their contribution to subsystem stability, and no items were removed, as the internal consistency indices indicated conceptual and statistical coherence across all dimensions.

- ✓

- Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Construct validity was assessed through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), conducted using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) extraction method with Varimax rotation [14]. Prior to factor extraction, the suitability of the dataset for factor analysis was confirmed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, which tested whether correlations among items were sufficient for factor modeling.

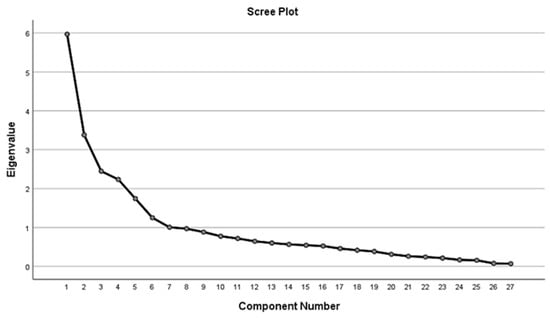

Once suitability was established, the factor extraction process was performed. Communalities were reviewed to determine the extent to which each item contributed to the extracted factors. The total variance explained, and the Scree Plot were used to establish the optimal number of factors retained in the model. The rotated component matrix was then examined to interpret factor loadings and verify alignment with the five theoretical dimensions proposed during questionnaire construction.

- ✓

- Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics (mean values, standard deviations, and frequency distributions) were used to characterize the sample and summarize response patterns. Reliability analysis (Cronbach’s Alpha) and exploratory factor analysis (PCA with Varimax rotation) were performed as described above. Significance levels were interpreted using standard thresholds recommended in quantitative social and behavioral research.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal reliability and structural validity of the questionnaire. The internal consistency of each dimension, as well as of the instrument, was assessed using Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient, with a threshold of 0.70 considered acceptable according to established recommendations in the literature.

Values between 0.70 and 0.80 were interpreted as satisfactory, while values above 0.80 indicated very good reliability. In addition, corrected item–total correlations and the variation in the Alpha coefficient in the case of item removal were examined to evaluate the individual contribution of each item to the overall consistency of the scale.

Construct validity was investigated through Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), using the Principal Component Analysis (PCA) extraction method and orthogonal Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization, to identify latent dimensions and confirm the proposed theoretical structure.

The suitability of the data for factor analysis was verified using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity, both of which confirmed the applicability of the method. Subsequently, communalities were examined to estimate the proportion of variance explained by each item, followed by the total variance explained and the Scree Plot to determine the optimal number of factors. The rotated component matrix was then analyzed to identify the items that define each factor.

3. Results

The study sample consisted of 420 participants, of whom 72.6% were dentists (n = 305) and 27.4% were dental technicians (n = 115). Age distribution indicated a predominance of younger professionals: 64.3% of respondents were under 30 years old (n = 270), 23.8% were between 30 and 40 years old (n = 100), and 11.9% were between 40 and 50 years old (n = 50). Regarding gender distribution, 59.5% of the participants were female (n = 250), while 40.5% were male (n = 170), indicating a slight predominance of women within the sample.

The validation of a questionnaire is essential to ensure that the research instrument accurately and consistently measures the intended constructions, thereby guaranteeing the credibility, reproducibility, and scientific relevance of the results obtained.

- Dimension 1—Perceptions of Digital Technologies

The internal reliability analysis for this dimension, consisting of 5 items, indicated a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.777, which reflects good internal consistency and satisfactory homogeneity among the items. This result confirms that the questions are coherent with one another and collectively measure, in a unified manner, the professionals’ perceptions of digital technologies as seen in Table 1:

Table 1.

Internal reliability analysis.

The descriptive analysis showed that respondents expressed a high level of agreement with all statements, with mean scores ranging from 4.26 to 4.64 (on a scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) (Table 2). The highest level of agreement was recorded for the statement “I believe that digital technologies represent a natural evolution of the profession” (M = 4.64; SD = 0.52), followed by “Digital technology contributes to patient comfort” (M = 4.57; SD = 0.54). The lowest mean score, although still high, was obtained for the item “Digital technologies provide superior accuracy compared to conventional methods” (M = 4.26; SD = 0.65).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for the items in Dimension 1—Perceptions of Digital Technologies.

These results suggest that the participating professionals display a highly favorable attitude toward digital technologies, perceiving them as precise, efficient, and naturally integrable into modern dental practice (Table 2).

The statistical analysis of the five items that compose this dimension shows that all mean scores are above 4 (on a Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), which reflects a positive attitude and a high level of acceptance of digital technologies among the respondents as seen in Table 3:

Table 3.

Item–total statistics for Dimension 1—Perceptions of digital technologies.

These results confirm that the professionals in the sample have a highly favorable perception of digital technologies, which they consider to be precise, efficient, and essential for the future progress of the field.

- Dimension 2—Attitude toward conventional technologies

For this dimension, composed of five items, the internal consistency analysis indicated Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.700, a value that lies at the threshold of acceptability. This result suggests a moderate internal consistency, indicating that the items are correlated with each other, but reflect somewhat varied perspectives regarding the role of conventional technologies, as seen in Table 4 below:

Table 4.

Internal consistency analysis: Dimension 2—Attitude toward conventional technologies.

At the descriptive level, the results show a more balanced distribution of opinions compared to Dimension I. The highest mean was recorded for the statement “Conventional technologies are still essential and cannot be replaced” (M = 3.75; SD = 1.07), which suggests that respondents still consider traditional methods to be important. In contrast, the level of agreement was lower for the items “Traditional procedures are safer” (M = 2.71; SD = 0.84), “I prefer classical methods due to manual control” (M = 2.90; SD = 0.96), and “Professional training should place emphasis on conventional approaches” (M = 2.79; SD = 1.01). The item “The outcomes of classical methods are comparable to those of digital methods” obtained an intermediate value (M = 3.31; SD = 0.93) as can be seen in Table 5:

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics for the items in Dimension 2—Attitude toward conventional technologies.

The item–total analysis showed moderate correlations, with values ranging between 0.35 and 0.57, confirming that the items contribute differently to the reliability of the scale. Removing any item would have resulted in a slight increase or decrease in Cronbach’s Alpha (up to a maximum of 0.691), which suggests that all items can be retained, as they collectively contribute to the overall consistency of the dimension, in Table 6.

Table 6.

Item–total statistics for Dimension 2—Attitude toward conventional technologies.

- Dimension 3—Perceived advantages of the technologies

For this dimension, composed of five items, a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.742 was obtained, indicating good internal consistency, above the acceptable threshold of 0.70. This suggests that the items are adequately correlated with each other and provide a relatively coherent description of respondents’ perceptions regarding the benefits of digital technologies, as in Table 7:

Table 7.

Internal consistency analysis—Dimension 3.

At the descriptive level, the mean scores ranged from 2.77 to 3.77, indicating a more moderate attitude compared to the dimension concerning general perceptions of digital technologies. The highest level of agreement was reported for the item “Digital technologies significantly reduce working time” (M = 3.77; SD = 0.94), followed by “Investment in digital technology is justified in the long term” (M = 3.30; SD = 0.85). The items with the lowest mean scores were “They allow more efficient dentist–technician communication” (M = 2.78; SD = 0.87), “Digital equipment standardizes processes” (M = 3.00; SD = 0.87), and “They represent an effective method for attracting potential patients” (M = 2.80; SD = 1.08) as in Table 8 below:

Table 8.

Descriptive statistics for the items in Dimension 3—Perceived advantages of the technologies.

The item–total correlation analysis indicated moderate values, ranging between 0.48 and 0.55, which confirms the relevance of each item to the dimension. The consistency testing in the event of item removal showed that no item would significantly improve Cronbach’s Alpha value, which supports the retention of all five questions, as illustrated in Table 9.

Table 9.

Item–total statistics for Dimension 3—Perceived advantages of the technologies.

- Dimension 4—Barriers and Concerns

For this dimension, composed of seven items, a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of 0.799 was obtained, indicating very good internal consistency, close to the threshold of excellence (0.80). This result shows that the items are well correlated with each other and consistently reflect the difficulties perceived by participants regarding the use of digital technologies, illustrated in Table 10:

Table 10.

Internal consistency analysis—Dimension 4.

At the descriptive level, the mean scores were high (ranging from 3.97 to 4.37), indicating that respondents generally perceived significant obstacles. The highest agreement was expressed for the item “The cost of digital equipment is an obstacle” (M = 4.37; SD = 0.81), followed by “Digital technologies are difficult to learn/apply” (M = 4.32; SD = 0.86) and “The lack of training limits their implementation into practices/laboratories” (M = 4.31; SD = 0.82).

High levels of agreement were also recorded for the statements “I am concerned about possible technical errors” (M = 4.08; SD = 0.91) and “I did not receive sufficient training during university studies” (M = 4.10; SD = 0.85). The lowest, though still elevated, mean scores were obtained for the items “I express concerns regarding the reliability of digital equipment in clinical practice” (M = 4.02; SD = 0.87) and “I am hesitant to rely solely on digital technologies” (M = 3.97; SD = 0.82), all results being illustrated in Table 11:

Table 11.

Descriptive statistics for the items in Dimension 4—Barriers and Concerns.

The item–total analysis showed correlations ranging from 0.42 to 0.67, confirming that each item contributes meaningfully to the consistency of the dimension. Although removing certain items would lead to minor variations in the coefficient (between 0.745 and 0.792), none of the items substantially reduces the homogeneity of the scale, which supports retaining all of them.

This dimension reflects that the main perceived obstacles in adopting digital technologies are high costs, insufficient training, and difficulties in practical application, to which are added reservations regarding the reliability of equipment and the risk of technical errors. These results suggest the need for more extensive training programs and accessible financial solutions to facilitate the transition toward digitalization, as in Table 12:

Table 12.

Item–total statistics for Dimension 4—Barriers and Concerns.

- Dimension 5—Intentions and future perspectives

For this dimension, composed of five items, the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient was 0.770, indicating good internal consistency, sufficiently robust to validate the reliability of the scale. However, as shown in Table 13, the detailed item analysis reveals notable differences in the extent to which each item contributes to the coherence of the dimension.

Table 13.

Internal consistency analysis—Dimension 5.

At the descriptive level, the results reflect a less homogeneous attitude compared to the other dimensions. The highest mean was recorded for the statement “I am willing to gradually abandon conventional methods” (M = 4.31; SD = 0.94), suggesting a clear orientation among respondents toward the gradual adoption of digital technologies. In contrast, the lowest means were obtained for the items “I am interested in postgraduate/advanced training courses in the digital field” (M = 2.40; SD = 0.90) and “I intend to invest in acquiring digital technologies within the next two years” (M = 2.69; SD = 1.05), indicating reluctance regarding financial investment and professional development in this area. These results are illustrated in Table 14.

Table 14.

Descriptive statistics for the items in Dimension 5—Intentions and future perspectives.

The item–total analysis showed that most items had moderate to high correlations (between 0.55 and 0.83), whereas the statement “I am willing to gradually abandon conventional methods” demonstrated a low correlation (0.17), which reduced the internal consistency of the scale. If this item were removed, Cronbach’s Alpha would increase to 0.843, indicating a very good level of reliability. However, retaining this item is conceptually justified, as it captures an important aspect of respondents’ intentions. All these results are presented in Table 15.

Table 15.

Item–total statistics for Dimension 5—Intentions and future perspectives.

Dimension 5 highlights that, although professionals acknowledge the inevitable trend of digitalization and are conceptually willing to gradually move away from conventional methods, there are still significant reservations regarding financial investment and professional training. This disparity suggests the need for educational policies and logistical support to facilitate the transition toward digital practice.

Internal Consistency Analysis for the entire questionnaire is made with statistical tests applied to confirm the adequacy of the data for exploratory factor analysis and support the validity of the construct. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index was 0.646, a value that fell within the acceptable range. This indicates that the sample size and the correlations among items are sufficient to justify the application of factor analysis, although the level is not very high (the ideal threshold is >0.70).

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity was significant (χ² = 6144.37; df = 351; p < 0.001), indicating that the correlation matrix among items is not an identity matrix and that there are sufficient intercorrelations to extract meaningful factors in Table 16.

Table 16.

KMO and Bartlett’s Test.

Overall, these results confirm that the questionnaire is structurally valid and that its items can be grouped into defined dimensions (perceptions, attitudes, advantages, obstacles, and intentions).

The communality analysis performed using the PCA method, illustrated in Table 17 showed that most questionnaire items are well explained by the extracted factors, with values above the recommended threshold of 0.50. Items such as “The use of digital technologies improves the quality of treatments” (0.774), “The integration of digital workflows increases the efficiency of clinical–technical procedures” (0.775), “They allow for more efficient communication between the clinician and the technician” (0.714), or “The future of the profession will be dominated by digitalization” (0.844) demonstrated high communalities, indicating a strong correlation with the factorial structure and a solid contribution to construct validity. Most of the remaining items scored between 0.55 and 0.70, reflecting an adequate level of representation.

Table 17.

Communalities—the proportion of variance of each item that is explained by the extracted factors (PCA).

The only notable exception was the item “The results of conventional methods are comparable to those of digital methods,” which showed a low communality value (0.350), suggesting that this question is less well explained by the model and contributes less to the overall coherence of the scale. Overall, the results confirm that the questionnaire is well structured and that the items are mostly relevant and consistent, with only a few specific aspects that may warrant revision.

The total variance explained analysis, conducted using the PCA method, showed that seven principal factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were extracted from the set of items, jointly accounting for 66.76% of the total variance. The first factor explained 22.11% of the variance, with the subsequent factors contributing 12.51%, 9.06%, 8.27%, 6.44%, 4.63% and 3.72%, respectively, as shown in Table 18 below:

Table 18.

Total variance explained by Principal Component Analysis (PCA).

After rotation of the factorial solution, the structure stabilized and the distribution of variance became more balanced across factors, with the first component explaining 15.68% and the remaining components explaining between 4.40% and 11.82%. These results indicate that the analyzed variables cluster into several distinct yet interrelated dimensions, which together adequately capture the complexity of the investigated construct. The level of explained variance (nearly 67%) is satisfactory for research in the social sciences and confirms that the questionnaire’s structure is well-grounded from a factorial standpoint.

The Scree Plot analysis shows a sharp decline in eigenvalues for the first factors, followed by a gradual stabilization of the curve, as it can be noticed in Figure 1. The “elbow point” (inflection point) is visible around the fifth–sixth component, suggesting that the optimal model may be structured around 5 or 6 principal factors. This observation is consistent with the results presented in Table 18, where the first five factors together account for approximately 58.4% of the total variance, and the inclusion of the sixth factor increases the proportion to 63%. Therefore, the convergent interpretation of the two analyses confirms that the questionnaire’s structure can be described through five theoretical dimensions corresponding to the initial construct (perceptions, attitudes, advantages, barriers, intentions), while also providing statistical support for the inclusion of a sixth secondary factor.

Figure 1.

Scree Plot of the exploratory factor analysis (PCA) for identifying the optimal number of factors.

The analysis of the Component Matrix confirmed the extraction of seven factors according to the criterion of eigenvalues greater than 1, as can be seen in Table 19. The questionnaire items cluster into distinct groups, each loading differently onto the identified components. The first factor is dominated by items reflecting positive perceptions of digital technologies, such as accuracy, treatment quality, efficiency, and patient comfort, as well as perceived obstacles such as cost or lack of training. This suggests a complex dimension combining both advantages and barriers.

Table 19.

Component Matrix Analysis (Component Matrix).

The second factor is primarily loaded by items expressing concerns and uncertainties regarding reliability and technical errors, confirming the presence of a distinct dimension of perceived risk.

The fourth factor predominantly includes statements reflecting a preference for conventional methods and their perceived safety, while the fifth factor captures transitional attitudes and the gradual shift away from traditional approaches. Factors six and seven appear to reflect more nuanced aspects, such as the perception of digitalization as part of the natural evolution of the profession and the role of professional training in supporting this transition.

Overall, the distribution of factor loadings suggests that the proposed theoretical structure (five main dimensions: perceptions, attitudes, advantages, obstacles, and intentions) is supported, although some overlapping of items is present. This reinforces the need to apply a rotation method (Varimax or Oblimin) to achieve a clearer separation of the dimensions.

The application of Varimax rotation enabled a much clearer separation of items across dimensions, confirming the multidimensional structure of the scale, as seen in Table 20. Thus, Factor 1 is defined by intentions and positive perspectives regarding digitalization (interest in continuing education, willingness to invest, belief that the future of the profession will be dominated by digital technologies, and the tendency to recommend their use), suggesting a dimension of proactive orientation toward digitalization.

Table 20.

Rotated Component Matrix (Varimax)—item loadings on the extracted factors.

Factor 2 is dominated by items referring to fears, reservations, and lack of training (fear of technical errors, insufficient university preparation, doubts about reliability, and perceptions regarding cost and complexity), and is interpreted as the dimension of obstacles and hesitations.

Factor 3 groups reflecting the objective advantages of digital technology (accuracy, treatment quality, efficiency, and patient comfort), capturing positive perceptions and direct clinical benefits.

Factor 4 includes items related to clinical and technological efficiency (reduced working time, improved clinician–technician communication, long-term investment value, standardization of procedures, and increased patient appeal).

Factor 5 consists of items emphasizing the role and value of conventional methods (their essential nature, procedural safety, manual control, and perceived comparability of results), representing the dimension of adherence to traditional approaches.

Factor 6 is characterized by the perception that digital workflows are part of the natural evolution of the profession, contrasted with the notion of process standardization, suggesting a dimension of conceptual integration of digitalization in dentistry.

Finally, Factor 7 includes items reflecting intermediate positions, especially regarding professional training and reservations toward fully replacing traditional methods, which can be interpreted as a dimension of transition and adaptation.

Overall, the rotated factor structure confirms the five theoretical dimensions initially proposed (perceptions, advantages, obstacles, attitudes, and intentions) but also reveals two additional nuanced dimensions (conceptual integration and transition), indicating a higher level of complexity in professionals’ representations of digitalization in dentistry.

The Component Transformation Matrix illustrates how the Varimax rotation reconfigured the factorial solution by redistributing the loadings to achieve a clearer and more interpretable structure, in Table 21. The values indicate the correlations between the initial components extracted through Principal Component Analysis and those obtained after rotation. High correlations can be observed between certain components, confirming that the rotation reorganized the items in such a way that each factor is more distinctly defined, showing a dominant loading with fewer overlaps. As a result, the final factorial solution gains greater coherence and allows for a more precise interpretation of the latent dimensions under analysis.

Table 21.

Component Transformation Matrix.

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to validate a questionnaire designed to evaluate dental professionals’ perceptions regarding the integration of digital technologies in clinical and laboratory workflows.

This study employed a convenience sampling strategy based on voluntary participation, primarily through online professional groups. While this approach allowed access to a geographically dispersed population of practitioners in the North-East region of Romania, it does not permit computation of a response rate and may introduce self-selection bias. Clinicians with greater interest, familiarity, or experience with digital technologies may have been more likely to participate, potentially affecting the representativeness of the sample. As such, the findings should be interpreted with caution when generalizing to the broader dental community, and future research should consider probabilistic sampling strategies where feasible.

The demographic profile of the sample, which included a disproportionately high number of participants under the age of 30, reflects the voluntary online recruitment strategy and introduces potential sampling bias. Consequently, some attitudinal patterns—such as stronger enthusiasm for digital technologies, lower interest in postgraduate training, and weaker attachment to conventional workflows—may partly reflect generational trends rather than profession-wide attitudes.

While this limits the generalizability of the findings, it also provides meaningful insight into the perceptions of early-career clinicians, who constitute the group most exposed to digital workflows during their academic training. Future studies employing stratified or probabilistic sampling methods are warranted to ensure balanced age representation and to better capture cross-generational differences in technology adoption.

The psychometric assessment demonstrated strong internal consistency and confirmed the multidimensional structure of the construct, supporting the instrument’s applicability for educational and research purposes. The factorial solution obtained after Varimax rotation highlighted distinct but interrelated dimensions related to perceived clinical advantages, existing barriers, professional attitudes toward technology integration, and the continued perceived value of conventional methods, aligning with conceptual patterns previously reported in digital dentistry research.

An important aspect emerging from the results is the coexistence of positive perceptions of digital workflows with the recognition of the ongoing relevance of conventional techniques. Participants acknowledged the benefits of digital tools—such as enhanced accuracy, workflow standardization, improved efficiency, and greater patient comfort—yet many still expressed confidences in manual control, particularly in complex or nuanced clinical situations [15].

Recent international studies highlight that the adoption of digital technologies in dentistry is shaped not only by infrastructural availability but also by psychological, educational, and economic barriers. High initial costs, insufficient training, and clinicians’ reluctance toward technological change remain significant obstacles worldwide [16,17].

This balanced positioning is characteristic of the current stage of digital transition in dentistry, where the adoption of new technologies does not eliminate traditional protocols but rather complements them according to case-specific requirements. Similar hybrid practice models have been described in the recent literature, where the progression toward full digitalization occurs gradually and depends on practitioner readiness, institutional resources, and training opportunities [18,19,20,21].

Consistent with our findings, several investigations have shown that clinicians’ perceptions of accuracy, efficiency, and clinical reliability strongly influence their intention to adopt digital systems, often more than the actual availability of equipment [22,23,24].

Studies examining global adoption patterns indicate that familiarity with intraoral scanners and CAD/CAM systems is closely related to practitioners’ confidence and readiness to use digital workflows, reinforcing the relevance of the dimensions assessed in our questionnaire [24,25].

The results also suggest that barriers to digital adoption remain substantial, particularly those related to high equipment costs perceived, fear of technical errors, and insufficient pre-graduate training. These findings are in line with international evidence indicating that the successful implementation of digital dentistry requires not only technological infrastructure but also structured educational support and clinical exposure [26,27,28].

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, the reliance on voluntary participation through online professional groups introduces self-selection bias, potentially favoring individuals with stronger interest in digital technologies. Second, the sample displayed a pronounced age imbalance, with a large proportion of respondents under 30 years old, which may limit the generalizability of findings across generations.

A notable finding of the present study is the divergence between highly favorable perceptions of digital technologies and the simultaneously high endorsement of barriers, combined with low intention to invest in digital equipment or pursue postgraduate training. This apparent contradiction reflects a well-documented phenomenon in technology adoption research, namely, the gap between conceptual acceptance and practical feasibility. Participants acknowledge the superior accuracy, efficiency, and clinical value of digital workflows, yet structural realities such as financial constraints, limited training opportunities, and uncertainty regarding return on investment restrict their ability to translate these beliefs into action.

Younger clinicians, who composed a large proportion of our sample, may be particularly aware of the advantages of digitalization but lack the economic stability or institutional support needed to invest independently. Consequently, the data suggest a form of “practical–structural dissonance,” where enthusiasm for innovation coexists with significant contextual barriers, inhibiting behavioral intentions despite strong cognitive endorsement. This dynamic provides important insight into why digital transformation in dentistry progresses unevenly and highlights the need for targeted educational and financial policies.

The extraction of seven components using the Kaiser criterion is consistent with well-known tendencies toward over-estimation in PCA. Examination of the scree plot, combined with theoretical constraints, strongly supported a five-factor structure. The sixth and seventh components contained only a small number of items and reflected higher-order or transitional constructs rather than stable dimensions. Retaining a five-factor solution increased parsimony and ensured alignment with the conceptual framework underlying the instrument. Cross-loadings observed for several items likely reflect conceptual proximity between constructions (e.g., perceived benefits and patient comfort), rather than structural instability.

Two supplementary factors emerged during PCA, a common outcome in multifactorial perceptual instruments where data-driven extraction identifies latent constructions beyond the predefined theoretical model. Factor 6 appeared to reflect a higher-order conceptual integration of digitalization within clinical practice, while Factor 7 captured transition and adaptation processes related to progressive skill acquisition and workflow change. Although not retained in the final structure to preserve fidelity to the instrument administered, their consistent extraction across unrotated and rotated solutions suggests meaningful perceptual dimensions that may guide future extension or refinement of the measurement model.

The presence of factors related to conceptual integration and transitional attitudes further suggests that digital technologies are increasingly perceived as part of the natural evolution of the profession, yet the pace and direction of adoption vary depending on individual and contextual variables.

This study has several limitations. The use of voluntary sampling may introduce self-selection bias, as individuals with stronger interest in digital workflows could be overrepresented. The cross-sectional design does not allow conclusions regarding changes in perceptions over time or following exposure to additional training.

A methodological limitation of this study is that factor retention was based on eigenvalues greater than 1 and scree plot inspection. Although seven components displayed eigenvalues greater than 1, factor retention was guided by multiple criteria. Visual inspection of the scree plot revealed a clear inflection after the fifth component, supporting a five-factor solution. The retained factors also demonstrated theoretical coherence with the predefined conceptual domains.

More robust procedures such as Parallel Analysis and Velicer’s MAP test were not applied in the present validation but will be incorporated in future studies to confirm the stability of the proposed five-factor structure.

Although several items within Dimension 1 reflect related perceptions of digital technology advantages (e.g., quality, efficiency, accuracy), these attributes represent distinct evaluative criteria in clinical practice and were therefore intentionally retained.

High inter-item correlations are consistent with a theoretically coherent construct, and internal consistency remained strong. Future refinements may consider item reduction to streamline measurement, provided conceptual breadth and reliability are maintained.

A small number of items displayed cross-loadings above 0.40 on more than one factor, a finding frequently observed in perceptual instruments with conceptually related domains. These overlaps likely reflect authentic intersections between constructs—such as patient comfort, perceived benefits, and professional attitudes—rather than measurement instability.

Each of these items maintained a dominant loading consistent with its theoretical dimension and thus retained their interpretive value within the current model. Nevertheless, these cross-loading patterns may guide future refinement of item phrasing to enhance discriminant clarity while preserving conceptual breadth.

The overall KMO value of 0.646, while modest, is within the acceptable range for exploratory factor analysis in multidimensional attitudinal research. Such values are frequently observed in early-stage validation studies assessing heterogeneous behavioral constructs.

Despite this, the factor solution demonstrated coherent loadings, strong internal consistency, and good conceptual alignment with the proposed theoretical model. Future studies with larger and more diverse samples may enhance sampling adequacy and allow further optimization of item performance.

Future studies with larger and more heterogeneous samples are needed to improve sampling adequacy and to confirm the dimensional structure using more robust factor-retention procedures such as Parallel Analysis or Velicer’s MAP test.

As for Dimension 5, although the item “I am willing to gradually abandon conventional methods” showed a low corrected item–total correlation (0.17) and its removal would have increased the internal consistency of Dimension 5, we elected to retain it due to its conceptual importance. This item reflects a distinct construct—behavioral readiness to relinquish conventional workflows—which is widely described in the digital dentistry literature as a major determinant of technology adoption.

Because no other item in the instrument captures this transition-related component, excluding it would reduce the conceptual completeness of the dimension. The modest psychometric performance is not unexpected in early validation studies, particularly for change-readiness items that inherently show greater variability. Future refinements using larger and more diverse samples may further clarify their stability.

Despite these limitations, the validated instrument provides a relevant and practical tool for understanding how dental professionals perceive and integrate digital technologies in their routine workflows.

It can support curriculum development by identifying gaps in digital training, inform continuing professional development programs by aligning training content with clinicians perceived needs, and guide institutional decisions regarding digital implementation strategies and resource allocation. Moreover, the instrument allows for comparative evaluation across professional groups or regions, contributing to a more informed and balanced integration of digital systems in contemporary dental practice.

5. Conclusions

The questionnaire developed to assess perceptions, attitudes, perceived advantages, barriers, and future intentions regarding the use of digital technologies in prosthodontic practice demonstrated adequate reliability and structural validity, with Cronbach’s Alpha values ranging from acceptable to very good across all five dimensions. The factor structure identified through exploratory factor analysis confirmed the conceptual coherence of the instrument and supported the theoretical model on which it was based.

Respondents exhibited strongly favorable perceptions of digital workflows, recognizing their contribution to improved accuracy, efficiency, and patient comfort. However, the findings also revealed persistent reliance on conventional techniques, reflecting the enduring value attributed to tactile control and procedural familiarity in clinical and laboratory contexts.

Despite acknowledging the benefits of digitalization, participants reported significant barriers to adoption, particularly related to financial costs, insufficient training, and concerns about reliability and technical errors. These challenges indicate that the integration of digital systems remains uneven and requires targeted support measures.

Overall, the validated instrument provides a reliable and useful tool for future investigations examining technological integration in dentistry. Moreover, the results highlight the need for structured training programs, institutional support, and strategic investments to facilitate a gradual and sustainable transition toward digitally oriented prosthodontic practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L., G.R. and D.I.V.; methodology, I.L. and G.R.; software, C.B. and O.-M.B.; validation, V.L., D.I.V. and M.S.T.; formal analysis, G.R. and F.R.C.; investigation, Z.S. and G.R.; resources, C.B. and F.R.C.; data curation, F.C.B. and Z.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.L. and D.I.V.; writing—review and editing, D.G.B.; visualization, O.-M.B. and C.B.; supervision, I.L. and M.S.T.; project administration, M.S.T., F.C.B. and D.G.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of UMF “Grigore T. Popa” Iasi-Romania. (668/2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| EFA | Exploratory Factor Analysis |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| KMO | Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

References

- Kafedzhieva, A.; Vlahova, A.; Chuchulska, B. Digital Technologies in Implantology: A Narrative Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangano, F.; Shibli, J.A.; Fortin, T. Digital Dentistry: New Materials and Techniques. Int. J. Dent. 2016, 2016, 5261247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, M. The Role of Digital Innovations in Shaping Contemporary Fixed Prosthodontics: A Narrative Review. Oral 2025, 5, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnaru, O.; Tatarciuc, D.; Bida, F.C.; Balcos, C.; Constantin, V.; Cojocaru, C.; Tudorici, T.; Rotundu, G.; Sîrghe, A.; Haba, D. The Accuracy of AI-Assisted Imaging Diagnosis versus Conventional Evaluation of Dental Professionals. Med.-Surg. J. 2025, 129, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, N.R.C.; Pigozzo, M.N.; Sesma, N.; Laganá, D.C. Clinical efficiency and patient preference of digital and conventional workflow for single implant crowns using immediate and regular digital impression: A meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 669–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emam, M.; Ghanem, L.; Abdel Sadek, H.M. Effect of different intraoral scanners and post-space depths on the trueness of digital impressions. Dent. Med. Probl. 2024, 61, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.; Hawsah, A.; Rustom, R.; Alamri, A.; Althomairy, S.; Alenezi, M.; Shaker, S.; Alrawsaa, F.; Althumairy, A.; Alteraigi, A. Digital Impressions Versus Conventional Impressions in Prosthodontics: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e51537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, M.; Hota, S.; Jain, A.; Dutta, D.; Bhushan, P.; Raut, A. Comparison of Conventional and Digital Workflows in the Fabrication of Fixed Prostheses: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e61764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budala, D.G.; Surlari, Z.; Bida, F.C.; Ciocan-Pendefunda, A.A.; Agop-Forna, D. Digital Instruments in Dentistry-Back to the Future. Rom. J. Oral Rehabil. 2023, 15, 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Mallineni, S.K.; Sethi, M.; Punugoti, D.; Kotha, S.B.; Alkhayal, Z.; Mubaraki, S.; Almotawah, F.N.; Kotha, S.L.; Sajja, R.; Nettam, V.; et al. Artificial Intelligence in Dentistry: A Descriptive Review. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butnaru, O.-M.; Tatarciuc, M.; Luchian, I.; Tudorici, T.; Balcos, C.; Budala, D.G.; Sirghe, A.; Virvescu, D.I.; Haba, D. AI Efficiency in Dentistry: Comparing Artificial Intelligence Systems with Human Practitioners in Assessing Several Periodontal Parameters. Medicina 2025, 61, 572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchini-Fabris, G.-B.; Cosola, S.; Toti, P.; Hwan Hwang, M.; Crespi, R.; Covani, U. Immediate Implant and Customized Healing Abutment for a Periodontally Compromised Socket: 1-Year Follow-Up Retrospective Evaluation. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavakol, M.; Dennick, R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2011, 2, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fabrigar, L.R.; Wegener, D.T.; MacCallum, R.C.; Strahan, E.J. Evaluating the use of exploratory factor analysis in psychological research. Psychol. Methods 1999, 4, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlen, M.; Thorbjørnsen, H. Individuals’ Assessments of Their Own Wellbeing, Subjective Welfare, and Good Life: Four Exploratory Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schnitzler, C.; Bohnet-Joschko, S. Technology Readiness Drives Digital Adoption in Dentistry: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joda, T.; Bornstein, M.M.; Jung, R.E.; Ferrari, M.; Waltimo, T.; Zitzmann, N.U. Recent Trends and Future Direction of Dental Research in the Digital Era. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M.; AlAmir, M.; AlGhamdi, M.; Abdel-Mottaleb, M.; Collado-Mesa, F. Towards a better understanding of annotation tools for medical imaging: A survey. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 25877–25911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasim, A.G.; Abo Elezz, M.G.; Altonbary, G.Y.; Elsyad, M.A. Accuracy of digital and conventional implant-level impression techniques for maxillary full-arch screw-retained prosthesis: A crossover randomized trial. Clin. Implant. Dent. Relat. Res. 2024, 26, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Róth, I.; Hermann, P.; Vitai, V.; Joós-Kovács, G.L.; Géczi, Z.; Borbély, J. Comparison of the learning curve of intraoral scanning with two different intraoral scanners based on scanning time. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsalini, M.; Barile, G.; Ranieri, F.; Morea, E.; Corsalini, T.; Capodiferro, S.; Palumbo, R.R. Comparison between Conventional and Digital Workflow in Implant Prosthetic Rehabilitation: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Funct. Biomater. 2024, 15, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gavali, N.; Chandak, A.; Waghmare, P.; Jamkhande, A.; Nisa, S.U.; Shah, P. Implementation of Digitization in Dentistry from the Year 2011 to 2021: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Int. Clin. Dent. Res. Organ. 2023, 15, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovac, A.; Kuzmanović Pfićer, J.; Stančić, I.; Milić Lemić, A.; Petričević, N.; Peršić Kiršić, S.; Čelebić, A. Psychometric Properties of the Five-Item Ultrashort Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP5) in the Serbian Cultural Environment: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, F.; Seoane, M.; Reichenheim, M.E.; Tsakos, G.; Celeste, R.K. Adult oral health-related quality of life instruments: A systematic review. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 2022, 50, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, M.T.; Sekulić, S.; Bekes, K.; Al-Harthy, M.H.; Michelotti, A.; Reissmann, D.R.; Nikolovska, J.; Sanivarapu, S.; Lawal, F.B.; List, T.; et al. Why Patients Visit Dentists—A Study in All World Health Organization Regions. J. Evid.-Based Dent. Pract. 2020, 20, 101459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahn, S.; Kim, J.; Baek, S.; Kim, C.; Jang, H.; Lee, S. Toward Digital Twin Development for Implant Placement Planning Using a Parametric Reduced-Order Model. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, L.; Meneghello, R.; Savio, G.; Scheda, L.; Monaco, C.; Gatto, M.R.; Micarelli, C.; Baldissara, P. Manufacturing of Metal Frameworks for Full-Arch Dental Restoration on Implants: A Comparison between Milling and a Novel Hybrid Technology. J. Prosthodont. 2019, 28, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendes, J.J. Advancing the Understanding of Oral Health Through Multidisciplinary and Translational Perspectives: Insights from a Special Issue of the Journal of Clinical Medicine. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.