Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this in vitro study was to evaluate the accuracy of intraoral impressions obtained using the Trios 3Shape® (3Shape Trios, Copenaghen, Denmark) and Carestream CS 3600™ (Carestream Dental, Stuttgart, Germany) scanners, compared with traditional polyvinyl siloxane (PVS) impressions. A laboratory scanner served as the gold standard. Materials and Methods: The study was based on 3D-printed master models derived from partially edentulous clinical cases previously treated at our department (2017–2022). All cases required at least two implants. Data analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA and two-sample Z-tests (α = 0.05) to compare mean deviations and variability. Results: All techniques demonstrated high accuracy, with deviations from the reference point below 30 μm. The digital intraoral scanners (Trios 3Shape® and Carestream CS 3600®) showed superior accuracy compared with PVS analog impressions, with no statistically significant difference between the two IOS systems. Conclusions: Within the limitations of this in vitro study, both IOS systems and PVS analog impressions achieved clinically acceptable accuracy. Digital systems exhibited improved performance in terms of mean deviation and consistency. The higher accuracy and consistency of digital impressions may translate into improved clinical efficiency and prosthetic fit in implant rehabilitations. From a clinical perspective, these in vitro findings suggest that digital impressions may enhance prosthetic fit and workflow efficiency, though further in vivo validation is required. Clinical significance: This study supports the reliability of intraoral scanning compared with conventional impressions in implant-supported rehabilitations. By demonstrating high intrinsic accuracy, these findings contribute to optimizing digital workflows in implant dentistry and reinforce the potential of intraoral scanning in static computer-guided, flapless implant surgery. Trial registration: Ethical approval and trial registration were not applicable to the present in vitro investigation, as no patients were directly involved in the experimental phase. The digital data used to generate the laboratory master models originated from a separate clinical study conducted at ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan (Ethics Committee approval no. 1361, 12 July 2017; ClinicalTrials.gov registration, Unique Protocol ID 1361).

1. Introduction

In recent decades, the field of dentistry has undergone a transformation thanks to the advent of digital technology. Digitalization is profoundly revolutionizing the way clinicians deliver care to patients and how dental procedures are planned, performed, and evaluated. This digital revolution has brought countless benefits for patients, improving diagnostic accuracy, optimizing treatments, and overall making the chairside experience more comfortable [1,2].

One of the first steps toward digitalization was the introduction of Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT), which enabled the acquisition of highly accurate three-dimensional radiographic images while significantly reducing patients’ radiation exposure. However, it would be limiting to consider CBCT merely as a diagnostic aid. When acquired, it should be seen as an entry point into the CAD/CAM system. The introduction of CAD/CAM systems in dentistry has radically changed the design and manufacturing processes of prosthetic devices. After acquiring the patient’s impression—either digitally or through a traditional analog method later digitized via laboratory scanners—the clinician can use CAD software to design the prosthetic devices. The design can then be sent directly to a 3D printer or milling machine, allowing for the rapid production of customized devices. This new approach can eliminate cumulative errors typically associated with the lengthy processes of traditional methods [3,4].

The digitalization of the CAD/CAM production workflow was ultimately completed with the introduction of intraoral scanners (IOS). These systems have significantly reduced the time required to take impressions and have made communication with the dental laboratory much faster and more efficient [5,6].

Despite the remarkable technological advancements and increasingly promising clinical outcomes achieved through digital workflows, the scientific literature has questioned the differences between traditional analog methods and digital ones. However, current evidence remains inconsistent regarding the accuracy (trueness and precision) of digital versus conventional impression techniques in implant-supported rehabilitations. Several studies and reviews report high or comparable accuracy for IOS relative to PVS in many clinical/in vitro settings [7,8,9], whereas other investigations highlight limitations for full-arch or multi-implant spans (e.g., cumulative stitching and strategy-dependent errors), sometimes favoring conventional approaches for long spans [10,11,12]. Moreover, direct head-to-head comparisons between different IOS systems and conventional PVS under standardized conditions are still limited; specifically, evidence comparing Trios3Shape® and Carestream CS 3600™—two widely adopted scanners with distinct acquisition technologies—remains relatively scarce, although available in vitro data do exist [13,14].

In this in vitro experimental protocol, intraoral scanners (IOS) are compared with the current gold standard for impression taking, represented by traditional analog impressions.

The objective of the present study was to evaluate the accuracy of the Trios3shape® and Carestream CS 3600TM intraoral scanners, as well as the traditional analog impression using polyvinyl siloxane (PVS). The impressions and scans were taken from different implant cases treated prospectively. The null hypothesis is that there are no significant differences in accuracy among the different impression techniques.

2. Materials and Methods

This in vitro study was based on 51 master models obtained from partially edentulous clinical cases previously treated at the Implantology and Prosthodontics Department of the University of Milan. Digital and conventional impressions were compared under standardized laboratory conditions. The master models were generated from digital patient data (CBCT and intraoral scans), but no patients were directly involved in the experimental phase; therefore, ethical approval and informed consent were not required for this in vitro analysis.

Ethical approval and trial registration were not applicable to the present in vitro investigation, as no patients were directly involved in the experimental phase. The digital data used to generate the laboratory master models originated from a separate clinical study conducted at ASST Santi Paolo e Carlo, Milan (Ethics Committee approval no. 1361, 12 July 2017; ClinicalTrials.gov registration, Unique Protocol ID 1361). STROBE guidelines were followed (https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/) (accessed on 7 July 2023). Trend statement checklist was completed [15].

2.1. In Vitro Procedure

For each printed master model, implant scan bodies were positioned before scanning with Trios3shape® scanner. A polycarbonate model was printed and implant analogs were positioned in the master model.

The master model was the starting point for all measurements: a total of 4 scans were performed. This study proceeds independently of the clinical management of cases, as it is an in vitro study. The operator was aware of which scanner was being used during each scan. No blinding of the operator or outcome assessor was performed. All included models were analyzed; no data were lost. No protocol deviations occurred during the study. No adverse events or unintended effects could occur due to the in vitro design of the study.

- 1.

- Reference scan: Scan bodies were screwed on the master model, and a scan using a laboratory scanner (the Concept Scan Top™) was performed.

- 2.

- Trios3shape® scan: Scan bodies were screwed on the master model, and a scan using Trios3shape® scanner was performed.

- 3.

- Carestream CS 3600TM scan: Scan bodies were screwed on the master model, and a scan using Carestream CS 3600TM scanner was performed.

- 4.

- Analogical transfers were screwed on the implant analogues of the master model, a standard impression with polyvinylsiloxanes (PVS) was taken, and a dental stone model was obtained. Scan bodies were screwed on the stone model and scanned with the laboratory scanner (the Concept Scan Top™).

To verify the accuracy of the 3D models printed after digital scanning and those from the analog impression, the reference model used, due to its near-zero error, was the Concept Scan Top™ laboratory scanner. A surface analysis was performed by superimposing the STL files using Gom Inspect (Zeiss®, Oberkochen, Germany). After an initial manual pre-alignment of each individual impression with its corresponding reference impression obtained using the laboratory scanner (Figure 1a,b), the data were superimposed using the Best-Fit technique (Figure 2a–c). This method relies on algorithms that recognize and align homogeneous surface areas shared by both models. This approach ensures image alignment that is independent of the operator’s skill and guarantees accurate superimposition. The operator was aware of which scanner was being used during each scan. The distance measurements between the models were performed and expressed in millimeters (mm). The Gom Inspect software provided the distance value for each point, the mean value for each model, and the standard deviation.

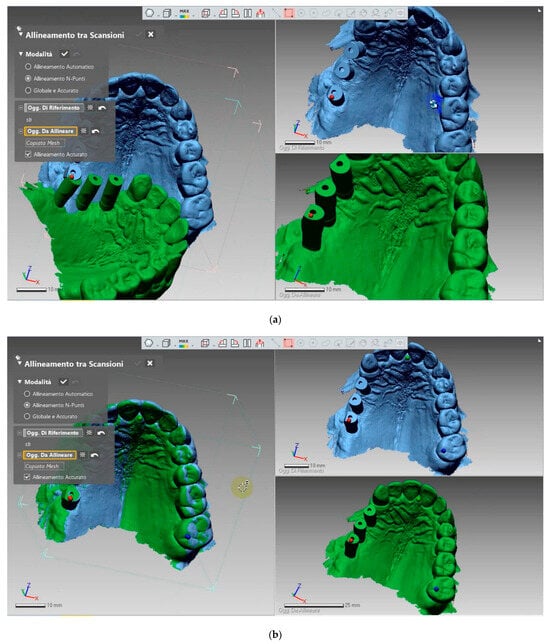

Figure 1.

(a,b) Selection of points to be overlapped by the operator.

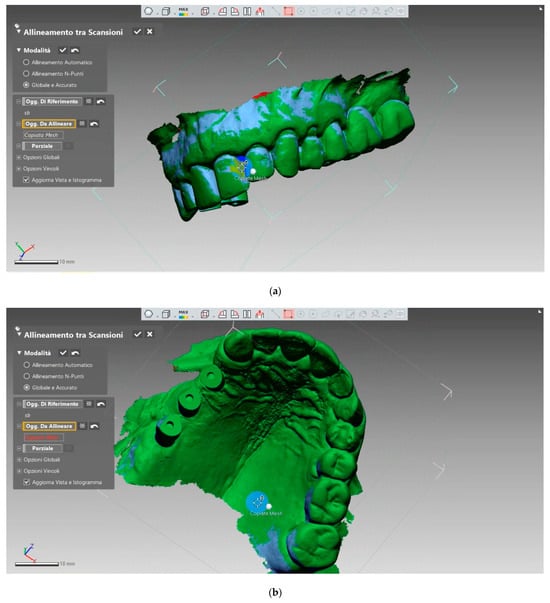

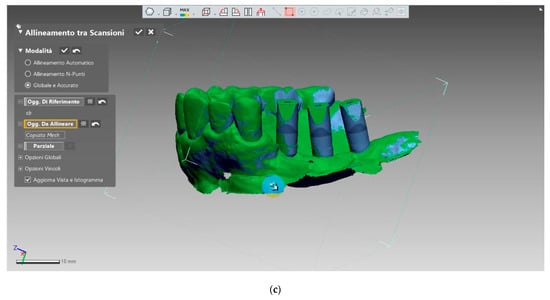

Figure 2.

(a–c). Best fit performed by the software according to internal algorithms.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using AnalystSoft StatPlus® (AnalystSoft Inc., Alexandria, VA, USA, Version 1). Using Gom Inspect by Zeiss® (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), the mean deviation values from the reference file were calculated for each model. They were expressed in absolute terms. In the present investigation, for each of the three test techniques (TRIOS®-3Shape, CS 3600® Carestream Dental, and PVS), the average values obtained from the superimpositions of 51 models ere calculated, resulting in the mean deviation of each method from the reference.

For each impression technique, the surface deviation between the test model and the reference model was computed using the Best-Fit alignment algorithm implemented in GOM Inspect (Zeiss®, Oberkochen, Germany). The software calculated the linear distance between corresponding surface points of the two superimposed STL files. The mean deviation for each model was defined as the arithmetic mean of the absolute distance values (in μm) of all surface points, while the standard deviation described the dispersion of these values around the mean. Thus, each master model provided one mean deviation value, representing its overall trueness relative to the reference scan.

For data analysis, a one-way ANOVA test and a two-sample Z-test were applied, with a significance level (α) set at 0.05. These tests were used both to compare the mean distances and to assess the standard deviations. Each technique was considered accurate if its mean deviation was less than 30 μm.

3. Results

A total of 51 models were analyzed. Table 1 reports the mean deviation (trueness) and standard deviation (precision) values for each impression technique. Both intraoral scanners—Trios 3Shape® and Carestream CS 3600®—showed lower mean deviation and variability compared with the conventional PVS impressions. Specifically, mean ± SD values were 13 ± 79 μm for Trios 3Shape®, 12 ± 82 μm for CS 3600®, and 25 ± 213 μm for PVS.

Table 1.

Absolute values in millimeters of the mean deviations for each model, corresponding standard deviations, and final average values for the three impression techniques.

When analyzing signed deviations (Table 2), Trios 3Shape® tended to produce slightly more negative deviations, whereas PVS showed a prevalence of positive deviations, indicating dimensional overestimation. Carestream CS 3600® demonstrated a balanced distribution around zero.

Table 2.

Displacement values in mm, considering both positive and negative values.

The ANOVA test (Table 3) revealed significant differences among the three techniques (p < 0.001). Pairwise comparisons using the Z-test (Table 4) confirmed that both digital systems were significantly more accurate than PVS (p < 0.001), while no statistically significant difference was found between the two scanners (p = 0.60).

Table 3.

ANOVA test between the means of the obtained values.

Table 4.

Z-Test Between the Mean Values Obtained with the Three Methods.

Showed a non-normal distribution with several outliers, particularly in the PVS group.

Figure 1 illustrates the overall distribution of deviations. All techniques achieved accuracy within the clinically acceptable threshold of 30 μm. However, the digital systems displayed narrower dispersion and higher consistency, as evidenced by their lower SD values (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

ANOVA test between the DVS of values obtained with the three methods.

Table 6.

Z-test between the DVS of values obtained with the three methods.

The mean deviation from the reference value was found to be (Table 1):

- (GROUP 1) digital impression with TRIOS®-3Shape: 13 μm with a standard deviation of 79 μm.

- (GROUP 2) digital impression with CS 3600®–Carestream Dental: 12 μm with a standard deviation of 82 μm.

- (GROUP 3) Polyvinyl Siloxane impression: 25 μm with a standard deviation of 213 μm.

Applying descriptive statistics, we conclude that all three techniques are characterized by high accuracy, as they deviate from the reference, assumed to have negligible error, by a value on the order of a few μm (less than 30 μm).

It is interesting to make descriptive considerations, considering the RELATIVE VALUES, that is, the average displacement values of the three methods with either a positive or negative sign (Table 2). The positive and negative signs were automatically assigned by the GOM Inspect software based on the direction of deviation between the test and reference surfaces. Positive values indicated that the test surface was located outward (above) relative to the reference model, whereas negative values indicated that the test surface was positioned inward (below) the reference surface. These signed deviations allowed qualitative visualization of the directionality of errors in the color-mapping analysis.

From the qualitative analysis of the techniques (Figure 1), the following observations can be made:

- TRIOS®-3Shape shows a slightly higher prevalence of negative deviations.

- PVS shows a clear prevalence of positive deviations.

- CS 3600®–Carestream Dental exhibits an almost equal prevalence of positive and negative values.

The IOS systems, TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600®, generally show mean deviation values that approach zero. However, a trend toward negative values is observed for TRIOS 3Shape®, and toward positive values for Carestream CS3600® [16].

Both the mean and median values indicate that the major part of the measurements are near zero. Therefore, it can be concluded that both IOS systems produce statistically similar results relative to the reference point.

In contrast, the analog PVS impression shows deviation values primarily skewed toward the positive, suggesting that in this study, the analog material tends to overestimate actual dimensions. Furthermore, the range of deviations is wider compared to the digital systems, and the mean and median values are shifted away from zero, indicating that most measurements deviate more significantly from the reference value, unlike what was observed with the IOS systems.

In summary, IOS systems such as TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600® appear to provide more accurate results than the analog PVS material, minimizing potential underestimation or overestimation in morphological and geometric measurements.

The statistical analysis began with a one-way ANOVA test (Table 3), evaluating the mean deviation values of the three measurement techniques, using a significance level (α) of 0.05.

The test revealed the presence of statistically significant differences among the techniques. Since the F-value exceeded the critical F-value, it was concluded that there is a statistically significant difference between the three methods analyzed. Moreover, the p-value was very low, indicating that the observed differences are unlikely to be due to chance. Therefore, since the p-value was less than α, the null hypothesis was rejected.

The analysis then proceeded with the two-sample Z-test (Table 4) to determine which specific groups exhibited statistically significant differences.

Analysis of comparisons between mean deviations:

- TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600®: Since the Z-value is less than the critical Z, there is no statistically significant difference in accuracy between TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600®. Additionally, there is a 60% probability that the results are due to chance. Therefore, since the p-value is greater than α, the null hypothesis is accepted.

- TRIOS 3Shape® and PVS: Since the Z-value is greater than the critical Z, there is a statistically significant difference in accuracy between TRIOS 3Shape® and PVS. Furthermore, the probability that the results are due to chance is negligible. Thus, since the p-value is less than α, the null hypothesis is rejected.

- Carestream CS3600® and PVS: Since the Z-value is greater than the critical Z, there is a statistically significant difference in accuracy between Carestream CS3600® and PVS. Similarly, the probability that the results are due to chance is negligible. Therefore, with the p-value less than α, the null hypothesis is rejected.

It can therefore be concluded that the two digital scanners exhibit comparable accuracy, although they show statistically significant differences when compared to the analog technique. For this reason, the null hypothesis is rejected.

The statistical analysis then focused on the study of the standard deviation (SD) (see Table 1 and Table 2), provided by the GOM software for each measurement. This represents the spread of the data around a central value, which in this case is the mean.

Previously, the mean standard deviation for each impression technique had been calculated (Table 1):

- TRIOS 3Shape®: 79 μm;

- Carestream CS3600®: 82 μm;

- PVS: 213 μm.

An ANOVA test (Table 5) was then applied, with a significance level of 0.05, to assess the differences in standard deviations associated with the mean deviations of the three techniques. The test revealed the presence of significant differences in the standard deviations among the three methods under analysis.

Since the F-value is greater than the critical F-value, it is concluded that there is a statistically significant difference among the three techniques analyzed. Additionally, the p-value is negligible, indicating that the observed results are unlikely due to chance. Therefore, since the p-value is less than α, the null hypothesis is rejected.

A two-sample Z-test (Table 6) was then performed to determine which specific groups exhibited statistically significant differences.

Analysis of comparisons between standard deviations:

- TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600®: Since the Z-value is less than the critical Z, there is no statistically significant difference between the standard deviations of TRIOS 3Shape® and Carestream CS3600®. Additionally, there is a 58% probability that the results are due to chance. Therefore, since the p-value is greater than α, the null hypothesis is accepted.

- TRIOS 3Shape® and PVS: Since the Z-value is greater than the critical Z, there is a statistically significant difference between the standard deviations of TRIOS 3Shape® and PVS. Moreover, the probability that the results are due to chance is negligible, so the null hypothesis is rejected.

- Carestream CS3600® and PVS: Since the Z-value is greater than the critical Z, a statistically significant difference exists between the standard deviations of Carestream CS3600® and PVS. The p-value is negligible, so the null hypothesis is rejected.

From the Z-test analysis, it emerges that the two IOS systems exhibit similar ranges of standard deviation, indicating comparable consistency. However, it is important to note that both digital systems show statistically significant differences when compared to the analog technique, suggesting that PVS impressions have higher standard deviations.

In other words, the data from the IOS systems are more consistent, with less variability, than those obtained using the conventional method. This means that the analog approach results in larger deviations, which can negatively affect measurement accuracy and result reliability.

This is further confirmed by the visual graphical representation above:

The standard deviations of the analog impressions are consistently higher than those of the IOS systems, and the variability between different standard deviation values is also significantly greater. This clearly indicates a higher dispersion of data in the analog impressions.

In conclusion, the analog technique demonstrates greater variability in the data collected, with significant discrepancies between measurements.

4. Discussion

The results of this study show that although all three impression techniques evaluated (TRIOS® 3Shape and Carestream CS 3600® intraoral scanners, and polyvinyl siloxane analog impressions) demonstrated high accuracy with mean deviations below 30 μm, the precision of digital impressions was significantly higher than that of traditional impressions. Therefore, the null hypothesis, which assumed no significant differences in accuracy between digital and analog techniques, was rejected. However, no statistically significant difference was found between the two digital scanners. These findings confirm that digital technologies represent an advancement over conventional methods while all tested systems remain within clinically acceptable thresholds.

The TRIOS® 3Shape intraoral scanner operates on the principle of focal microscopy, using an LED light source and a projected laser pattern to capture 3D images based on variations in reflected light and image focus. It employs Ultrafast Optical Scanning and Real Color technology to acquire thousands of 3D images, which are combined into a realistic digital impression in STL format, easily transferable to dental labs. The scanner features a smart touch screen, anti-fog autoclavable tips, and interchangeable scanning heads for both arches. The manufacturer reports an accuracy of 6.9 ± 0.9 μm and precision of 4.5 ± 0.9 μm [17,18].

The Carestream Dental CS 3600® scanner captures full-color 3D images using structured LED light and exports them in STL format for compatibility with open software systems. Its continuous scanning technology allows smooth operation even with sudden movements, enhancing workflow stability. The device includes an audio guidance system, real-time on-screen feedback with directional arrows, and colored indicators to highlight incomplete or defective scan areas. It also features a built-in heater to prevent fogging and uses autoclavable, interchangeable tips for flexible scanning [19,20].

The choice of polyvinyl siloxane (PVS), an elastomeric material, is due to its high precision and accuracy, good rigidity, and excellent elastic recovery. It offers significant resistance to deformation and ensures long-term dimensional stability. A one-step impression technique was used, and the models were subsequently poured using low-expansion Type IV dental stone [20].

Concept Scan Top™ laboratory scanner utilizes a blue structured light detection technology and is equipped with a 5-axis scanning system. The process of scanning the entire arch takes approximately 40 to 60 s and produces output files in STL, OBJ, OFF, and PLY formats. The specific performance characteristics of this scanner include an accuracy of 5 μm, precision of 2 μm, and resolution of 5 μm.

Regarding the digital impressions, once the scans of the 51 models were acquired using the two scanners, the digital volumes were exported as STL files to make them suitable for overlay and comparison. Accurately capturing an impression to create a model as close as possible to reality is a crucial step for the production of precise dental prostheses. This phase requires careful management, as conventional techniques often result in cumulative errors due to multiple steps in the process. Recent CAD-CAM digital systems aim to reduce these steps and overcome some limitations of traditional impressions. Intraoral scanners (IOS) have been compared to traditional methods, with promising results emerging in the literature.

Numerous studies analyze the accuracy of IOS compared to traditional systems, though findings often vary due to the lack of a universally accepted comparison protocol. The clinically acceptable misfit threshold is still debated, with some studies suggesting up to 30 µm [20], while others allow up to 150 µm [21]. This study adopts the 30 µm threshold for defining an accurate impression system.

A systematic review by Rutkunas et al. (2017) [22] found that new-generation IOS have accuracy equal to or greater than conventional methods, although the review’s limitation was that only one of the 16 studies was in vivo. A 2020 study by Roig et al. found that the CEREC® Omnicam IOS showed lower accuracy than polyether impressions, while other systems outperformed traditional methods. Similarly, a 2021 study by Albayrak et al. showed that IOS systems were more accurate than conventional methods, especially in full-arch implant situations [13,23].

However, some studies, such as one by Nedelcu et al. (2018) [24], argue that conventional methods (e.g., polyether impressions) may be more accurate than digital systems, particularly in non-implant cases. In certain studies, accuracy between various IOS systems was compared, with varying results due to differences in scanning techniques, software, and scanner technology. Overall, while IOSs show promising accuracy, their performance is influenced by many factors, including scanner technology, powder use, and scanning strategy [24].

The quality of scans obtained with the TRIOS® 3Shape system is further confirmed by a 2020 systematic review by Kihara et al., which found that the TRIOS® 3Shape scanner delivered the best results among the analyzed studies, positioning it as the IOS device closest to laboratory scanner performance [25].

Results from this study led to rejecting the null hypothesis, which posited that IOS and analog impressions show similar accuracy in implant rehabilitation. Instead, it was found that, both in terms of mean accuracy and data dispersion, PVS performed worse than digital systems. Nonetheless, all three methods showed accuracy within the clinically acceptable threshold of 30 µm. Some studies, favoring IOS systems, suggested that the advantages were due to the multiple steps inherent in traditional methods, which may accumulate errors, causing greater overall imprecision (e.g., errors in the traditional impression system, plaster model expansion, and laboratory scanner inaccuracies).

Discrepancies with other studies can be attributed to differences in accuracy evaluation methods and the software used to align the files. For instance, refs. [16,24] reported higher accuracy for conventional impressions compared with certain IOS systems, particularly in full-arch or long-span situations, where cumulative stitching errors may occur. In contrast, ref. [16] found that the Trios® and CS 3600® scanners achieved comparable or superior accuracy relative to analog techniques when applied to short-span implant scenarios. These differences may arise from variations in the number of implants scanned, the alignment algorithms adopted (Best-Fit vs. feature-based), and the surface characteristics of the test models used.

The present study, focusing on partially edentulous models and a standardized Best-Fit alignment protocol, therefore showed results more consistent with those of Imburgia et al. [12] and Kihara et al. [25], but not with Roig et al. [13] or Nedelcu et al. [24], whose protocols involved full-arch or in vivo conditions with higher error propagation.

It’s also crucial to consider that the skill and experience of the operator play a significant role in measurement accuracy, as a learning curve is required for the practitioner to fully leverage the capabilities of the IOS device. Additionally, it is important to note that this study was conducted in vitro, so the results may not directly reflect clinical reality. For optical impressions, the presence of moisture (e.g., saliva and blood), along with soft tissue mobility, could significantly affect the scanning process and impression accuracy. Similarly, for elastomeric impressions, moisture could influence the accuracy of the results. The present study provides additional quantitative evidence that, under standardized conditions, both Trios3Shape® and Carestream CS 3600™ achieve accuracy values well within the 30 µm clinical threshold, confirming their suitability for implant-supported restorations. This direct comparative data between these two scanners under identical conditions has not been reported before.

It’s worth noting that the models used in this study were 3D-printed and had a rougher, drier texture compared to the oral environment, which could have led to distortions in conventional materials and difficulty in their flow during the impression phase. Additionally, their opacity and lack of reflections (common on dental surfaces and mucosa due to saliva) might have contributed to more precise recording with IOS systems.

Although the Best-Fit overlay used for surface superimposition is algorithm-driven, our workflow included a manual pre-alignment step and the evaluator was not blinded to the impression technique. These aspects may introduce a potential risk of bias and should be considered a limitation of the present study.

The present investigation has several limitations that should be acknowledged. First, it was conducted in vitro, under controlled laboratory conditions that do not fully replicate the clinical environment; factors such as saliva, soft-tissue mobility, and patient movement may affect impression accuracy in vivo. Second, the operator was not blinded to the impression technique, potentially introducing measurement bias during scanning and data processing. Third, the sample included only partially edentulous models with short implant spans; therefore, the results cannot be directly extrapolated to full-arch rehabilitations. Moreover, only two intraoral scanners were evaluated, and both the scanning strategy and alignment method (Best-Fit algorithm) could influence deviation outcomes. Finally, the study assessed trueness and precision only through surface superimposition, without evaluating the clinical fit of the resulting prosthetic restorations.

This study specifically focused on partially edentulous implant rehabilitations, as these represent the most frequent clinical scenarios and allow for standardized short-span scanning procedures. Fully edentulous arches were intentionally excluded because they involve different technical challenges—such as longer scanning spans and fewer anatomic landmarks—which can increase cumulative stitching errors and reduce accuracy.

The available literature indicates that, despite continuous technological improvements, intraoral scanning of fully edentulous arches still shows variable results compared with conventional impressions, especially in full-arch implant cases. For this reason, the present results should be interpreted strictly within the context of partially edentulous models, without direct extrapolation to full-arch rehabilitations.

Within the limitations of this in vitro investigation, further in vivo studies are required to validate these findings under clinical conditions. Future research should compare different intraoral scanning systems, full-arch situations, and standardized scanning strategies to better assess the reproducibility and clinical applicability of digital versus conventional impressions in implant-supported rehabilitations.

It is also important to consider that IOS devices are continually updated with new hardware and software versions, while research on polyvinyl siloxanes (PVS) has largely reached its development limit. Therefore, future comparisons are likely to increasingly favor digital systems as technological improvements continue.

5. Conclusions

Within the limitations of this in vitro study, all three impression techniques—TRIOS® 3Shape, CS 3600® Carestream Dental, and PVS analog impressions—demonstrated high intrinsic accuracy, with mean deviations below 30 μm from the reference model.

Both digital systems showed superior accuracy and consistency compared with the conventional PVS method. These findings suggest that intraoral scanning can provide more reliable and reproducible impressions, reducing potential errors related to the analog workflow.

The conclusions are strictly limited to in vitro observations but clinical information can be drawn from these. From a clinical perspective, the higher trueness and precision of digital impressions may improve the passive fit of implant-supported restorations, enhance efficiency in laboratory communication, and increase patient comfort during impression procedures.

Further in vivo studies are needed to confirm these advantages under clinical conditions and to evaluate their long-term impact on prosthetic success and implant survival.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.R. and S.S.; methodology, M.S.; software, T.R.; validation, S.S., A.P. and F.A.; formal analysis, E.R.; investigation, M.S.; resources, E.R.; data curation, T.R.; writing—original draft preparation, F.A.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; visualization, S.S.; supervision, E.R.; project administration, M.S.; funding acquisition, E.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Prodent Italia (Pero, Milan, Italy) supported this protocol, providing trios intraoral scanner, dental implants, abutments and surgical guides free of charge, leaving the patients to pay only dental technicians for the prosthesis.

Institutional Review Board Statement

(Ethics Committee, University of Milan, approval no. 1361, 12 July 2017; ClinicalTrials.gov registration, Unique Protocol ID 1361).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Prodent Italia (Pero, Milan, Italy) supported this protocol, providing trios intraoral scanner, dental implants, abutments and surgical guides free of charge, leaving the patients to pay only dental technicians for the prosthesis.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Khurshid, Z. Digital Dentistry: Transformation of Oral Health and Dental Education with Technology. Eur. J. Dent. 2023, 17, 943–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Widhalm, K.; Maul, L.; Durstberger, S.; Klupper, C.; Putz, P. Real-Time Digital Feedback for Exercise Therapy of Lower Extremity Functional Deficits: A Mixed Methods Study of User Requirements. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 2023, 301, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suganna, M.; Nayakar, R.P.; Alshaya, A.A.; Khalil, R.O.; Alkhunaizi, S.T.; Kayello, K.T.; Alnassar, L.A. The Digital Era Heralds a Paradigm Shift in Dentistry: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2024, 16, e53300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Davidowitz, G.; Kotick, P.G. The use of CAD/CAM in dentistry. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 55, 559–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hassiny, A. Intraoral Scanners: The Key to Dentistry’s Digital Revolution. Compend. Contin. Educ. Dent. 2023, 44, 154–156. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abduo, J.; Palamara, J.E.A. Accuracy of digital impressions versus conventional impressions for 2 implants: An in vitro study. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2021, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Zhang, B.; Song, H.; Wu, D.; Song, T. Accuracy of digital implant impressions obtained using intraoral scanners: A systematic review of in vivo studies. J. Dent. Sci. 2023, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesce, P.; Nicolini, P.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Zecca, P.A.; Canullo, L.; Isola, G.; Baldi, D.; De Angelis, N.; Menini, M. Accuracy of Full-Arch Intraoral Scans Versus Conventional Impression: Systematic review. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 71. [Google Scholar]

- Bi, C.; Wang, X.; Tian, F.; Qu, Z.; Zhao, J. Comparison of accuracy between digital and conventional implant impressions. J. Adv. Prosthodont. 2022, 14, 236–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitai, V.; Németh, A.; Sólyom, E.; Czumbel, L.M.; Szabó, B.; Fazekas, R.; Gerber, G.; Hegyi, P.; Hermann, P.; Borbély, J. Evaluation of the accuracy of intraoral scanners for complete-arch scanning: A network meta-analysis. J. Dent. 2023, 137, 104636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanda, M.; Miyoshi, K.; Baba, K. Trueness and precision of digital implant impressions by IOS. Int. J. Implant. Dent. 2021, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imburgia, M.; Logozzo, S.; Hauschild, U.; Veronesi, G.; Mangano, C.; Mangano, F.G. Accuracy of four intraoral scanners in oral implantology. BMC Oral Heal. 2017, 17, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roig, E.; Garza, L.C.; Álvarez-Maldonado, N.; Maia, P.; Costa, S.; Roig, M.; Espona, J. In vitro comparison of the accuracy of four intraoral scanners. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkūnas, V.; Auškalnis, L.; Pletkus, J. Intraoral scanners in implant prosthodontics: A narrative review. J. Dent. 2024, 148, 105152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TREND Statement Checklist. Published Date: 01/01/2004. Available online: https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/149677 (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- Dogan, S.; Schwedhelm, E.R.; Heindl, H.; Mancl, L.; Raigrodski, A.J. Clinical efficacy of polyvinyl siloxane impression materials using the one-step two-viscosity impression technique. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2015, 114, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellitteri, F.; Albertini, P.; Vogrig, A.; Spedicato, G.A.; Siciliani, G.; Lombardo, L. Comparative analysis of intraoral scanners accuracy using 3D software: An in vivo study. Prog. Orthod. 2022, 23, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Róth, I.; Czigola, A.; Fehér, D.; Vitai, V.; Joós-Kovács, G.L.; Hermann, P.; Borbély, J.; Vecsei, B. Digital intraoral scanner devices: A validation study based on common evaluation criteria. BMC Oral Heal. 2022, 22, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Winkler, J.; Gkantidis, N. Trueness and precision of intraoral scanners in the maxillary dental arch: An in vivo analysis. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Klineberg, I.J.; Murray, G.M. Design of superstructures for osseointegrated fixtures. Swed. Dent. J. Suppl. 1985, 28, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jemt, T. Failures and complications in 391 consecutively inserted fixed prostheses supported by Branemark implants in edentulous jaws: A study of treatment from the time of prosthesis placement to the first annual checkup. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Implants. 1991, 6, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rutkunas, V.; Gečiauskaitė, A.; Jegelevičius, D.; Vaitiekūnas, M. Accuracy of digital implant impressions with intraoral scanners. A systematic review. Eur. J. Oral Implantol. 2017, 10 (Suppl. S1), 101–120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Albayrak, B.; Sukotjo, C.; Wee, A.G.; Korkmaz, İ.H.; Bayındır, F. Three-Dimensional Accuracy of Conventional Versus Digital Complete Arch Implant Impressions. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nedelcu, R.; Olsson, P.; Nyström, I.; Rydén, J.; Thor, A. Thor A. Accuracy and precision of 3 intraoral scanners and accuracy of conventional impressions: A novel in vivo analysis method. J. Dent. 2018, 69, 110–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kihara, H.; Hatakeyama, W.; Komine, F.; Takafuji, K.; Takahashi, T.; Yokota, J.; Oriso, K.; Kondo, H. Accuracy and practicality of intraoral scanner in dentistry: A literature review. J. Prosthodont. Res. 2020, 64, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).