Abstract

This study was conducted in order to enrich the safety evaluation system of vehicles on complex road sections and provide quantitative support for speed control and driving decision-making. To address the driving stability issue caused by trajectory uncertainty on curved roads, we analyzed lane-changing stability and found that trajectory variations induce a step change in centrifugal force, aggravating lateral instability. Secondly, we developed a variety of simulation schemes to determine the stability limit speed under multi-source information fusion and constructed the corresponding database. Finally, we established an interpretable driving stability evaluation method based on the Differential Evolution-Extended Belief Rule Base-Shapley Additive Explanations (DB-EBRB-SHAP) model. This model incorporates driving behavior as a qualitative variable into the hybrid framework, and its accuracy was further enhanced through parameter optimization. The results demonstrate that the model achieves high evaluation accuracy for driving stability on curved road sections (MAE = 0.0306 and RMSE = 0.0363). Interpretability analysis reveals that curve radius and lane-changing behavior are the key influencing parameters; the negative interaction effect between the two on driving stability will weaken as the curve radius increases.

1. Introduction

Road traffic safety and the casualties and economic losses caused by traffic accidents remain a global concern [1,2]. Statistically, over 25% of fatal accidents are related to road curvature, and the average accident rate on curved sections is approximately three times that of other types of sections [3], and the severity of the accidents is even higher [4]. Vehicle stability is related to the speed, height of the center of mass, load, road alignment and friction [5,6]. At transitional curves where radius varies, inadequate speed or steering adjustments may induce rollover or skidding accidents, which has a significant impact on driving on curved sections [7,8].

In recent years, scholars at home and abroad have conducted extensive research on the safety of vehicles on curved sections. The research focuses on the characteristics of traffic accidents, factors influencing driving risks on curved sections, vehicle dynamic feature analysis, and collision risk assessment [9,10,11]. Analyzing the dynamic characteristics of vehicles during their operation on curved sections can enhance the stability of vehicle movement and reduce the risk of lateral instability during operation on curved sections [12]. Lateral instability mainly manifests as two failure modes: skidding and rollover. When the frictional force between the tires and the road surface is insufficient to counteract the centrifugal force of the vehicle during steering, the vehicle may skid [13]. When the overturning moment generated by the centrifugal force during a vehicle’s turn exceeds the stabilizing moment, a rollover may occur [14]. Lateral acceleration is an important indicator for describing the lateral stability of a vehicle. Its dynamic response characteristics can reveal the evolution of stability. If the lateral acceleration of a vehicle during steering exceeds the critical value, there is a risk of skidding and rollover [15]. The evaluation indicators of vehicle rollover include rollover index (RI) [16], the lateral load transfer ratio (LTR), time to rollover (TTR) and the static stability factor (SSF) [17]. The evaluation indicators for vehicle skidding include the skidding angle [18], lateral offset [19] and yaw rate [20].

Current research on driving stability related to road alignment characteristics primarily develops along three aspects. The first is to establish the relationship between geometric design elements and vehicle dynamics based on statistical regression, and analyze the impact of road linear changes on vehicle dynamics from a macroscopic perspective [21,22]. Alrejjal et al. [14] used truck collision accident data on curved roads and revealed the correlation between road curves, road surface friction and rollover risk through the correlated random parameters logit model. Similarly, Liu et al. [23] established a regression equation based on traffic accident data, pointing out that the most important factor for vehicle collisions with road infrastructure is the curve radius, and road superelevation is the main factor affecting rollover accidents. Wang et al. [24] revealed the log-linear relationship between curve radius and vehicle running speed through generalized estimation equations. In another study, Alrejjal et al. [25] analyzed the correlation among road curves, road surface friction and rollover risk using collision accident data from curved roads. Zolali et al. [26] employed driving simulator data to develop structural equation modeling (SEM), quantifying how temporal factors, weather conditions, and horizontal curvature collectively influence speed selection. Such studies have, to some extent, revealed the influencing factors of driving risks; however, ignoring the problem of unbalanced distribution of traffic accidents may bring biases to the modeling results [27]. The accuracy of judging the complex causal relationship between road alignment and vehicle stability through regression models is still questionable [28]. The second is to simplify the vehicle model, combined with the kinematic and dynamic principles to construct theoretical analysis frameworks. Zhang et al. [29] developed a 7-DOF vehicle model to estimate the vehicle roll angle. Chen et al. [30] studied the lateral instability patterns of vehicles on flat and curved sections, established a framework for correcting the design speed, and pointed out the unreasonable speed limit strategies. Based on the four-wheel vehicle model and the 2D LuGre tire model, Huang et al. [31] discussed the influence of LTR, longitudinal speed and tire–road surface friction coefficient on the phase plane stable region. Wang et al. [32] analyzed the influence of front-wheel drive and rear-wheel drive modes on the stability of vehicles by establishing a 5DOF vehicle dynamics model. Žuraulis et al. [33] developed a 14-degree-of-freedom vehicle model to study the key influences of road curvature, pavement roughness and speed on vehicle stability. The basic point-mass vehicle model simplifies the vehicle as a single point, thus neglecting its dimensions and the load transfer induced by lateral acceleration. This simplification makes it inadequate for accurately simulating vehicle turning maneuvers [34,35]. These modeling methodologies inevitably face accuracy–simplicity trade-offs, particularly when characterizing complex vehicle dynamics under coupled lateral–longitudinal motion conditions. The third is to use simulation software to set traffic scenarios and analyze the alignment–vehicle interaction dynamics [36,37]. Sun et al. [38] demonstrated through Trucksim/Simulink simulation that a larger curve radius reduces the risk of vehicle skidding or rollover. Khanjari et al. [39] utilized Carsim/Truksim to study the influence of road sections with reverse horizontal curves and vertical slopes of different vehicles. Zheng et al. [40] used Carsim/Simulink to establish different road surface conditions and analyzed the braking stability of vehicles under different adhesion characteristics. Chen et al. [41] used Truksim to study the impact of transition curve design and superelevation on truck rollover threshold speed. Such research enables systematic parameterization of vehicle–road–environment interactions, and deeply reveals the vehicle dynamic status under the influence of multiple factors.

There are still many limitations in the current research. First, existing studies predominantly assume fixed trajectory movement (along road centerlines) to analyze the stability-influencing factors, while neglecting stability dynamics during trajectory variations where centrifugal force direction changes. Second, trajectory uncertainty is a reflection of driving behavior. However, current modeling frameworks fail to effectively couple qualitative driving behavior (inside/outside lane change) with quantitative road geometric parameters in hybrid approaches. Thirdly, stability assessment constitutes a critical foundation for driving decisions and trajectory planning, necessitating highly interpretable evaluation outcomes. Current methodologies demonstrate limited capability in leveraging multi-source uncertain data, resulting in insufficient interpretability of both the assessment models and their outputs.

The uncertainty of the trajectory is a qualitative variable. It is crucial to establish a hybrid model capable of handling both qualitative and quantitative variables and capture the complex logic underlying stability assessment. To comprehensively utilize quantitative and qualitative information, Yang et al. [42] introduced a confidence framework into IF-THEN rules and first proposed the Belief Rule Base (BRB). Aiming at the combinatorial explosion problem caused by the excessive number of prerequisite attributes and the excessive value of prerequisite attributes in BRB, Liu et al. [43] proposed the Extended Belief Rule Base (EBRB), which is widely applied in fields such as fault diagnosis [44], safety assessment [45], and risk prediction [46]. Given the numerous influencing factors and their complex, nonlinear, and uncertain relationships in vehicle stability assessment, model interpretability becomes essential. Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) is a machine learning model interpretation method inspired by cooperative game theory, which can calculate the specific influence of each feature on the model prediction. Parsa et al. [47] utilized SHAP to conduct interpretable analysis on accident prediction machine learning models and evaluate the feature dependence of accident occurrence factors. Furthermore, models such as LightGBM and CatBoost can be combined with SHAP to enhance interpretability and elucidate the importance of interacting variables [48].

Based on the above analysis, this study proposes to construct a driving safety assessment model by combining the EBRB and SHAP. The main work includes the following:

- This study investigates the impact of trajectory uncertainty on driving stability in curved roads. Guided by highway design standards, we constructed scenarios to determine stability limit speeds under three trajectories: along the road centerline, inside lane changing and in outside lane changing, ultimately compiling a comprehensive dataset.

- Based on the Extended Belief Rule Base, we propose a refined methodology incorporating parameter optimization, which transforms both quantitative and qualitative inputs into belief distributions to achieve unified modeling of semantic information and uncertainty. Using the simulation-generated dataset, we validate the proposed model’s accuracy in driving stability assessment.

- We develop an interpretable Differential Evolution-Extended Belief Rule Base-Shapley Additive Explanations (DE-EBRB-SHAP) framework, conducting attribution analysis to identify key stability-influencing factors and their interaction effects under trajectory uncertainty.

The rest of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 introduces driving stability and dataset construction. Section 3 presents the modeling methods and research framework. Section 4 provides a detailed account of the experimental setup and result analysis. Section 5 summarizes this article and provides an overview of future work.

2. Description of Driving Stability Assessment

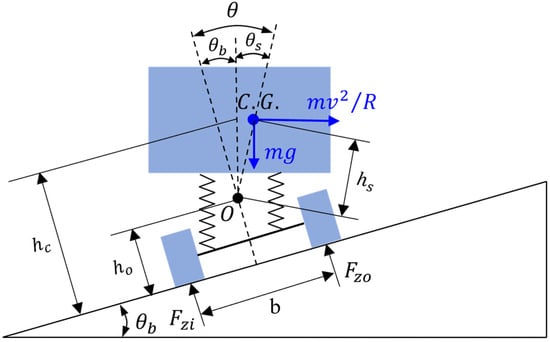

2.1. Force Analysis of Vehicle on Curve Section

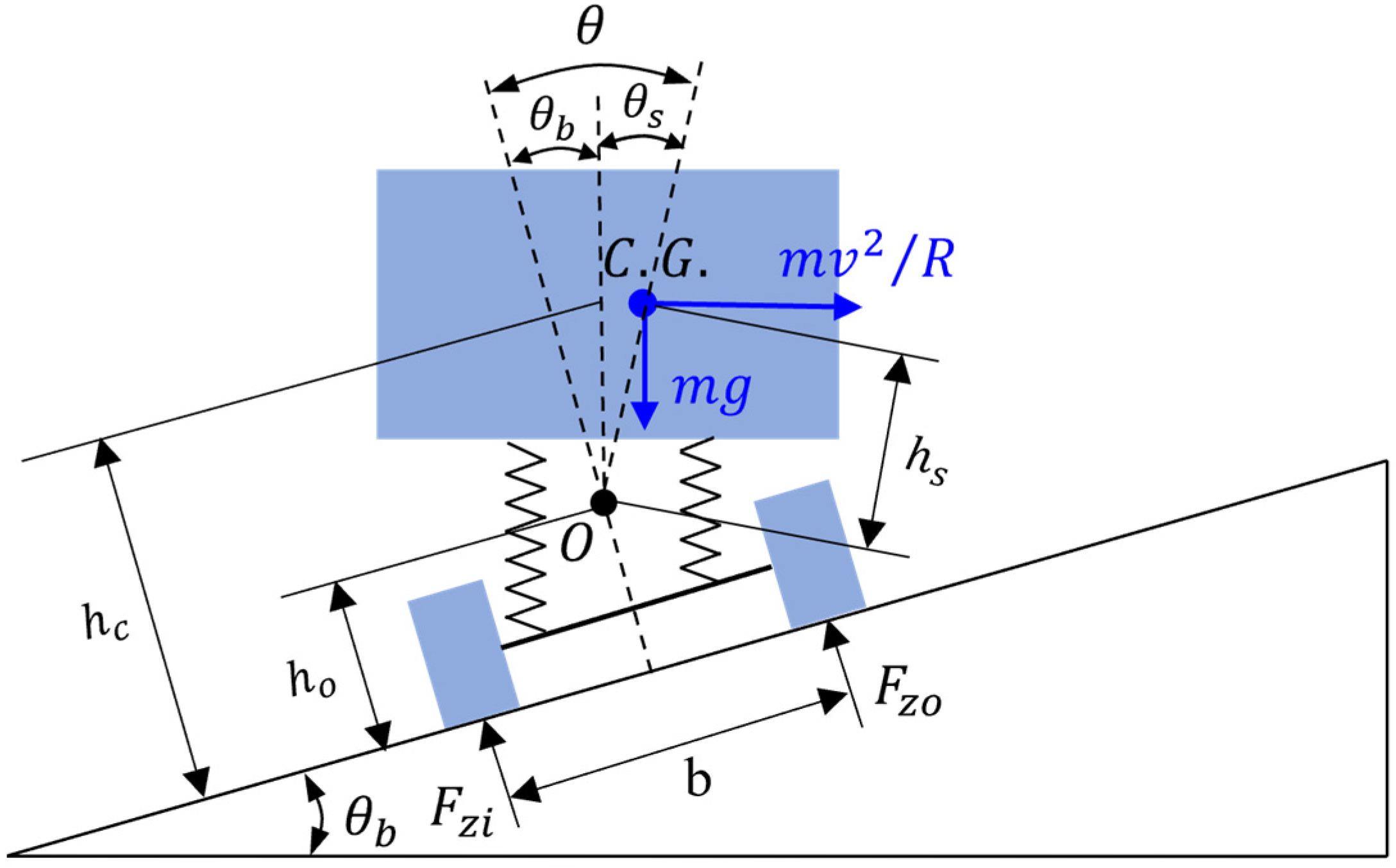

This study discusses the vehicle stability on curved sections with trajectory uncertainty, mainly focusing on the rollover and skidding dynamics during trajectory variations. When traveling on superelevated curved roads, load transfer occurs during wheel motion, which is specifically manifested as an asymmetric distribution of vertical loads on the inner and outer wheels [49,50]. The force analysis on curved road section is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Force analysis of vehicle on curved road section.

By analyzing the influencing factors of vehicles on a curved road, and taking the fixed trajectory condition as an example, the force balance equation along the y-axis can be expressed as [51]

The force balance equation along the z-axis is

The torque equilibrium equation around the x-axis is

Assuming the roll angle is small, the following simplification can be made.

where represents the sprung mass; is the height of the vehicle’s sprung mass center; is the height from the sprung mass center to the roll center; is the height of the roll center; b is the wheelbase; is the vehicle body roll angle; is the road slope angle; is the inclination angle of the mass center-to-roll centerline from the vertical; and are the roll load and vertical load at the roll center O, respectively.

- (1)

- Critical speed for sideslip

The critical condition for vehicle skidding is when the lateral force reaches the maximum adhesion between the tire and the road surface [52]. The maximum lateral adhesion can be expressed as

where is tire–road friction coefficient.

Due to the relatively small slope angle of the road, , , and the superelevation , ignoring the terms containing . Thus, Equations (1) and (2) can be simplified as

Therefore, Equation (5) can be simplified as

By combining the equation , the critical speed for sideslip can be obtained as follows:

where is the critical speed for sideslip.

- (2)

- Critical speed for rollover

The critical condition for vehicle rollover is that the vertical load on the inner wheels is zero [52]. Based on this, the moment equilibrium equation can be established as follows:

Combining Equation (6) can be expressed as

Under the assumption of small roll angle approximation, the superelevation and assuming , by combining Equation (3), we obtain

By combining the equation , the critical speed for rollover can be obtained as

where is the critical speed for rollover.

Summarizing the above analysis, the maximum speed at which a vehicle neither skids nor rolls over on a curved road can be expressed as [53]

According to Equations (1) and (2), the influencing factors considered in this paper include (driving behavior), (vehicle center of mass height), , , , and . The static stability factor () is introduced as a geometric characterization parameter of the vehicle. The larger the , the smaller the possibility of vehicle instability.

By establishing a vehicle speed prediction model that incorporates these factors, the safety status of the vehicle can be evaluated. The evaluation model can be expressed as

where is the stability state of the vehicle; is a nonlinear safety state evaluation function; is the parameter of the evaluation model.

2.2. Evaluation Index for Driving Stability

- (1)

- Sideslip index

During curved road driving, when the combined force of longitudinal and lateral is greater than the maximum available friction force, the vehicle experiences lateral slip [54], resulting in lateral deviation [55,56]. This study adopts lateral offset as the lateral slip evaluation index, as shown in the following equation.

where is the vehicle lateral offset; is the road width; is the vehicle width.

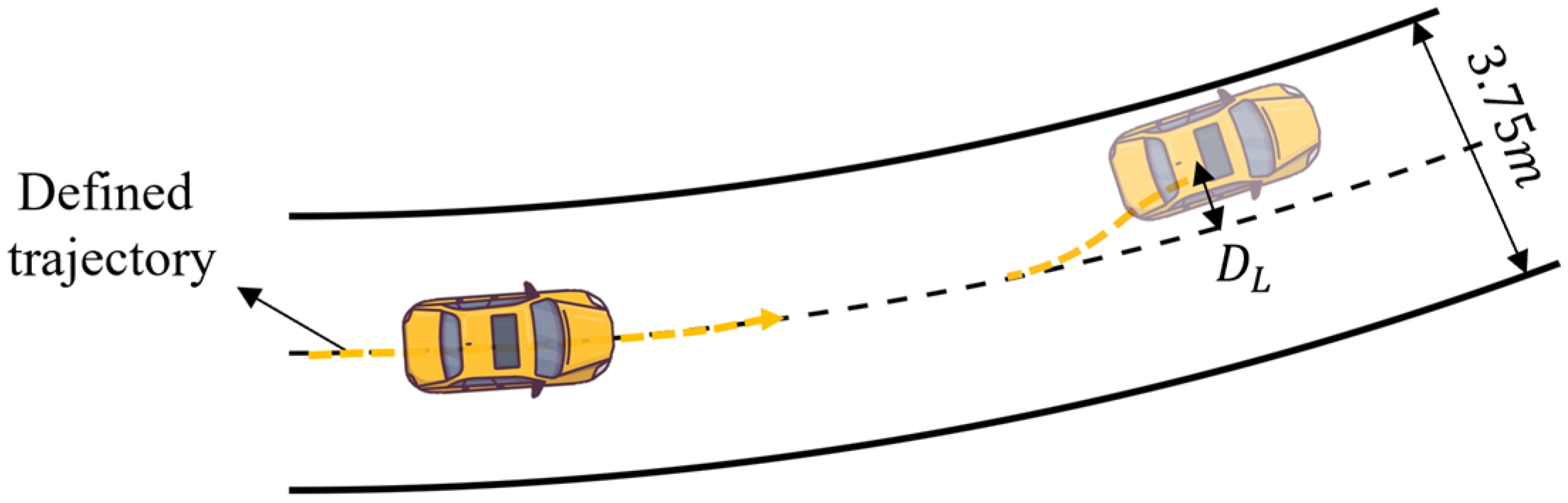

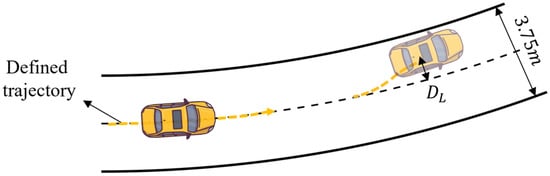

The lateral offset of the vehicle during driving is shown in Figure 2. In the simulation study, we gave the ideal driving trajectory and took the lateral offset of the vehicle relative to the ideal trajectory as the sideslip evaluation index. During the simulation, . If , , it indicates that the outer wheels of the vehicle are about to cross the boundary of the current lane and enter the adjacent lane, and it indicates that the vehicle has reached the sideslip limit. This sideslip limit is not only applicable when the vehicle is traveling in the current lane, but also during lane-changing processes. When the vehicle follows a defined lane-changing trajectory, the same sideslip limit is used to determine whether sideslip occurs.

Figure 2.

Vehicle lateral offset .

- (2)

- Rollover index

During curved road driving, when the vertical force of the inner load decreases, the vehicle loses roll stability, creating rollover risk [57]. Existing research has verified the credibility of the lateral load transfer ratio (LTR) as an evaluation index for rollover [58,59], as shown in the following equation.

where and represent the positions and total number of axles, respectively. is the vertical load on the left wheel at axle . is the vertical load on the right wheel at axle .

, the value is defined by the difference in vertical loads between the left and right tires. When , it indicates that the vertical loads on both sides are equal, and the vehicle is in a stable condition with no immediate rollover risk. When , it indicates that the vertical load on one side of the tires has reduced to zero. This represents the critical state where wheels begin to lift off, marking the theoretical threshold for rollover.

2.3. Dataset Construction

This study employs Carsim to establish various simulation scenarios. The basic parameters of the vehicle model are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Key parameters of the vehicle model.

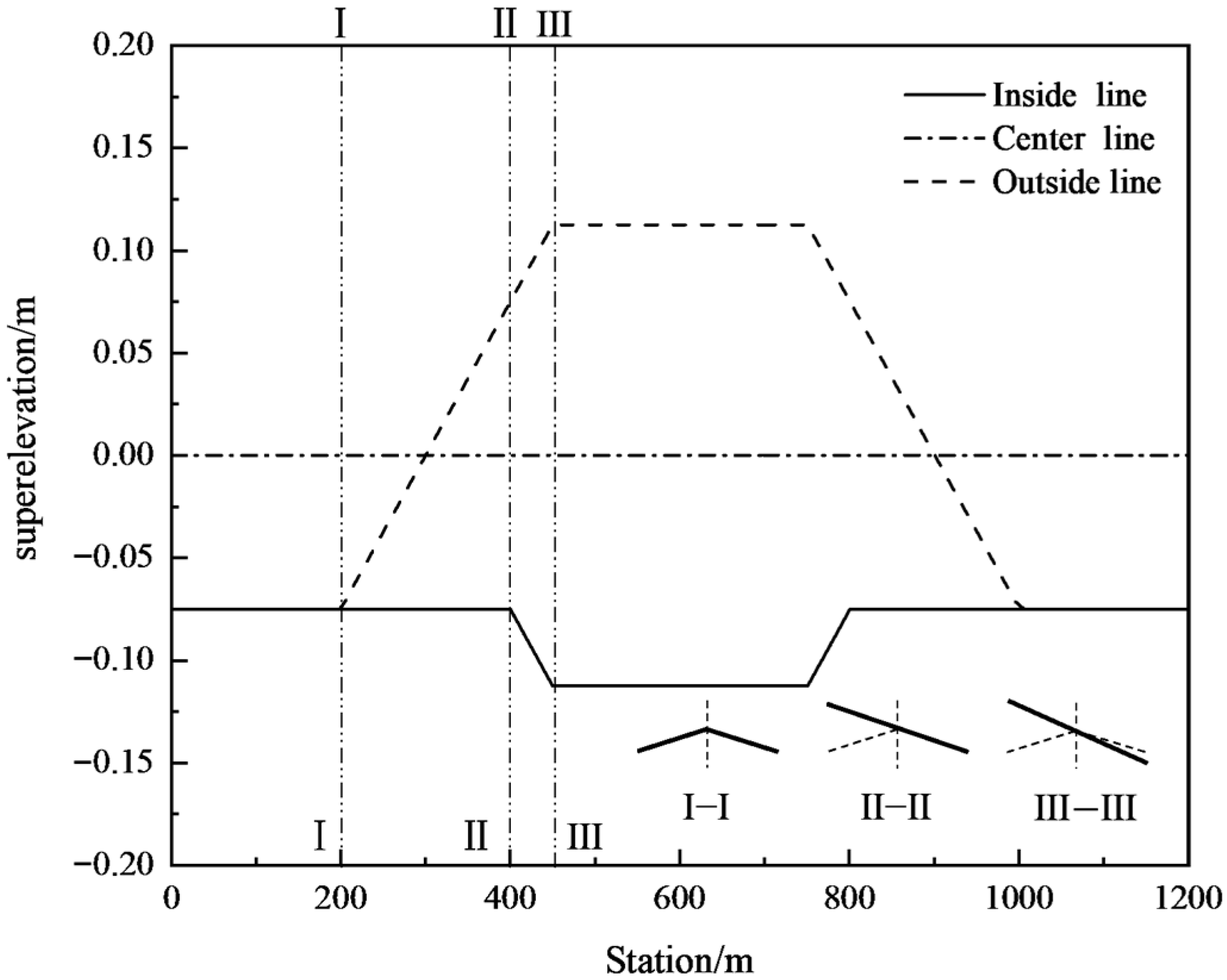

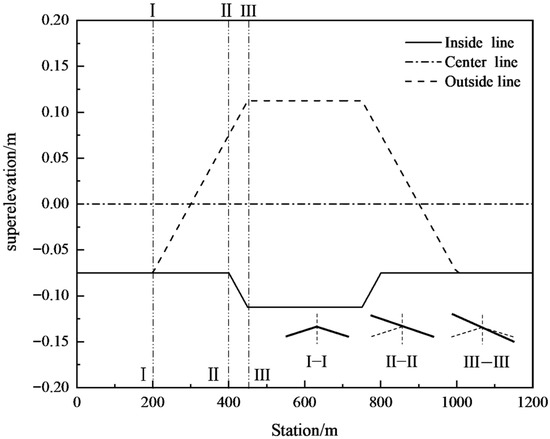

The lane change trajectory is generated by quintic polynomial curve, and the safe critical speed under different trajectories of each working condition is analyzed. The vehicle’s driving direction is controlled by the ‘1.5 s preview control strategy’. It is stipulated that the straight sections adopt 2% bidirectional cross slope, and the superelevation transitions are implemented through rotation about the road centerline, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Road superelevation transition form.

The simulation scheme design complies with Chinese highway design codes ‘Highway Engineering Technical Standards’ (JTG B01-2014) [60] and ‘Highway Alignment Design Specifications’ (JTG D20-2017) [61]. Through the permutation and combination of the values of influencing factors, multiple simulation experiment schemes are established as shown in Table 2, including a total of 3375 working conditions.

Table 2.

Simulation scheme.

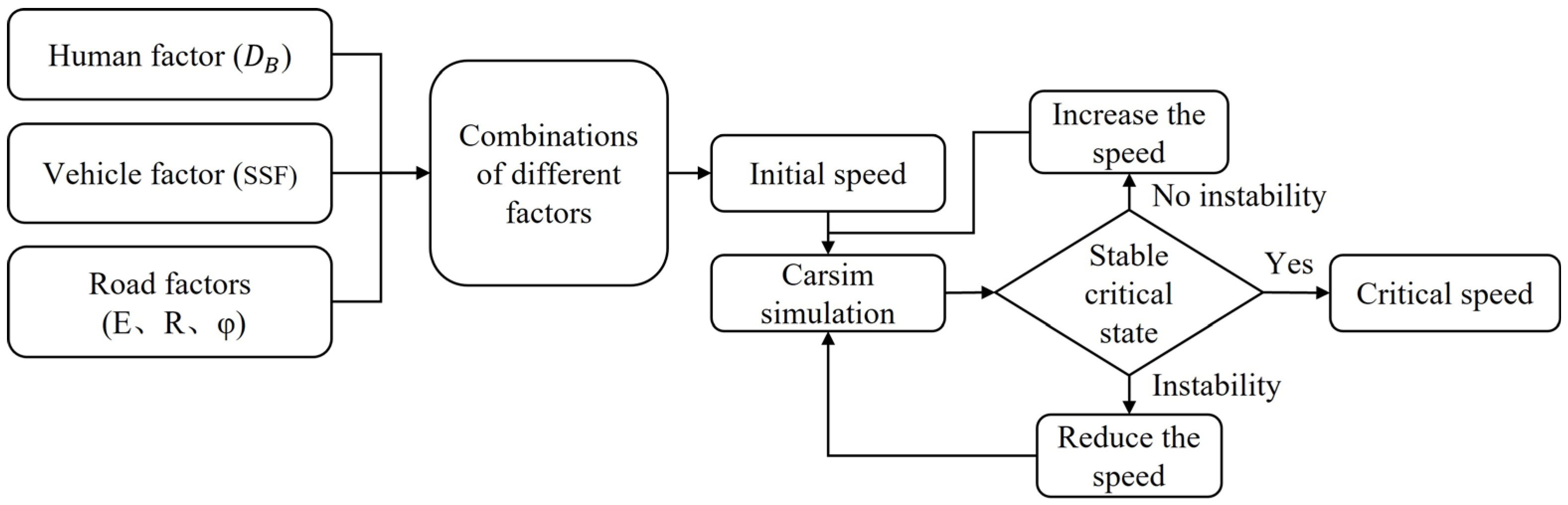

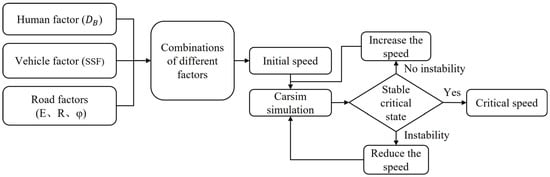

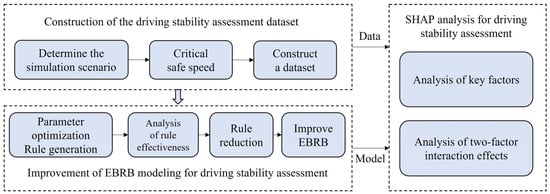

Summarizing the above steps, the process of constructing the driving stability assessment dataset for curved road sections is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

The construction process of the driving stability assessment dataset.

2.4. The Fundamental Characteristics of Dynamics with Uncertain Trajectories

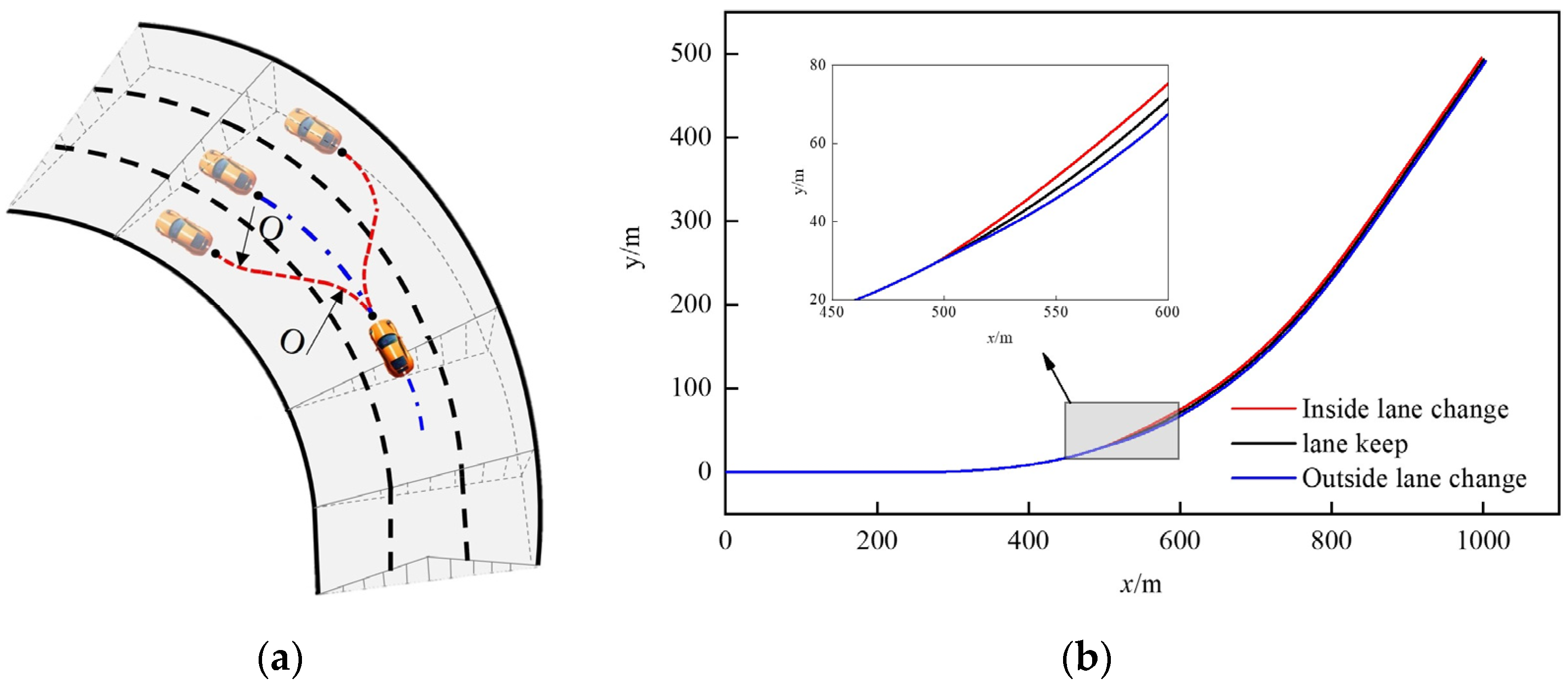

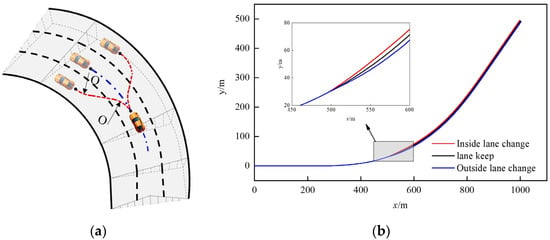

The vehicle’s movement along a fixed trajectory and lane-changing trajectory on a curved road is shown in Figure 5. The lane-changing behavior involves two distinct wheel turns. The sudden change in the curvature of the vehicle’s trajectory leads to a step in centrifugal force, affecting the vehicle’s stable state.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the vehicle trajectory on curve road. (a) Schematic diagram of vehicle lane changing. (b) Schematic diagram of vehicle trajectory.

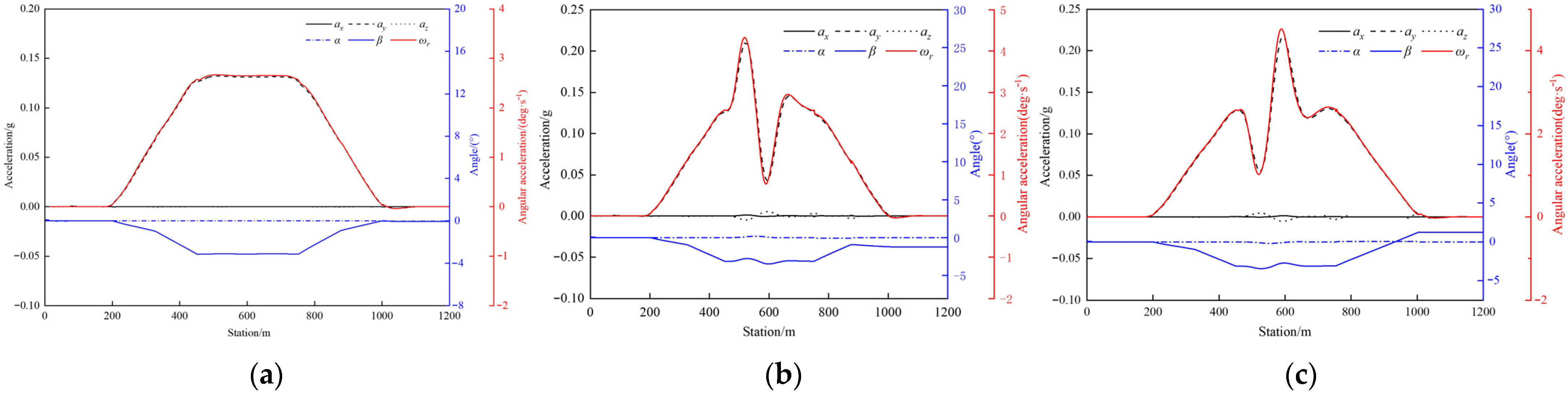

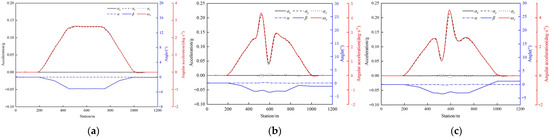

Select the same simulation scheme to analyze the influence of trajectory uncertainty on vehicle dynamics (). The pitch angle (), roll angle (), yaw angular velocity () and the vertical acceleration (), longitudinal acceleration (), and lateral acceleration () of the vehicle’s center of mass are used to characterize the pitch motion, roll motion, yaw motion, vertical motion, longitudinal motion, and lateral motion, respectively. The basic characteristics of the motion with an uncertain trajectory are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Basic characteristics of motion with uncertain trajectories. (a) Lane keeping. (b) Inside lane changing. (c) Outside lane changing.

The trajectory change mainly affects the vehicle’s yaw angle and lateral acceleration. The lane-changing process induces two distinct yaw angles, as in the description in Figure 5a, causing the lateral acceleration to change accordingly. Notably, the second yaw variation exhibits a higher amplitude, with post-maneuver lateral acceleration oscillations observed. Compared with inside lane changing, outside lane changing generates greater lateral acceleration.

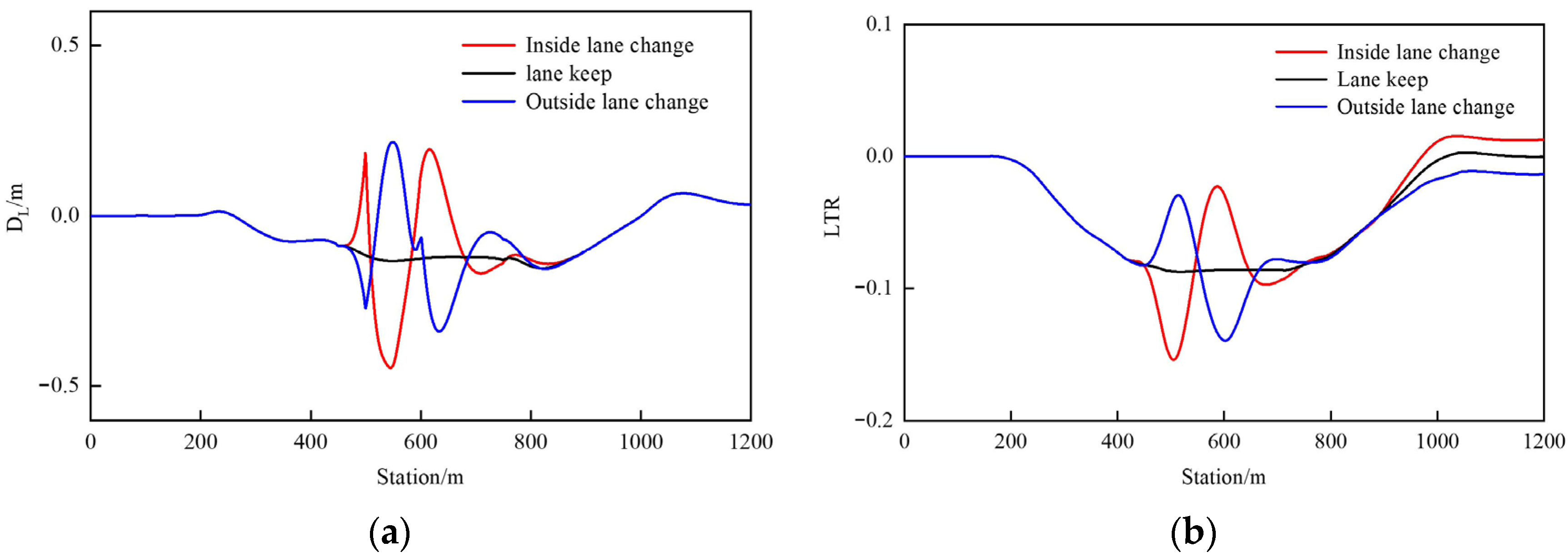

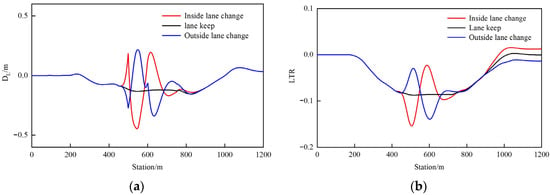

Furthermore, based on Figure 6, the driving stability of the vehicle when changing lanes on the inner side, along a fixed trajectory, and on the outer side at the same fixed speed is analyzed as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Driving stability under trajectory changes. (a) Lateral offset. (b) LTR.

It can be seen from the lateral displacement and LTR changes in Figure 7 that lane-changing behavior has a significant impact on driving stability. As shown in Figure 7a, the lane-changing behavior of vehicles on curved sections will increase lateral slip, and the maximum slip occurs during the first turn when changing lanes to the inside. As shown in Figure 7b, the lane-changing behavior of the vehicle will intensify the degree of load transfer, and changing lanes inward is more likely to cause vehicle instability than changing lanes outward. After leaving the curve, due to the influence of suspension or inertia, the load transfer cannot completely disappear.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. EBRB Inference for Driving Stability Assessment

- (1)

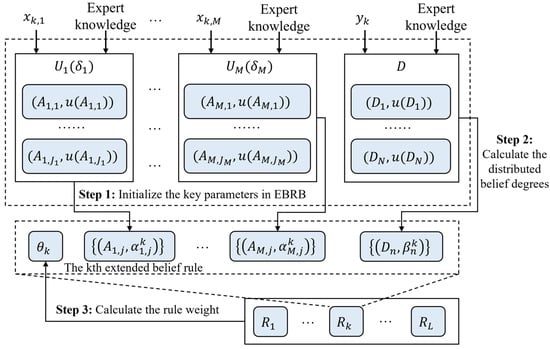

- The construction of EBRB

The k-th rule can be expressed as [62,63]

where is the i-th antecedent attribute; is the number of possible values of ; is the n-th assessment result; is the belief degree of ; is the rule weight of ; is the attribute weight of .

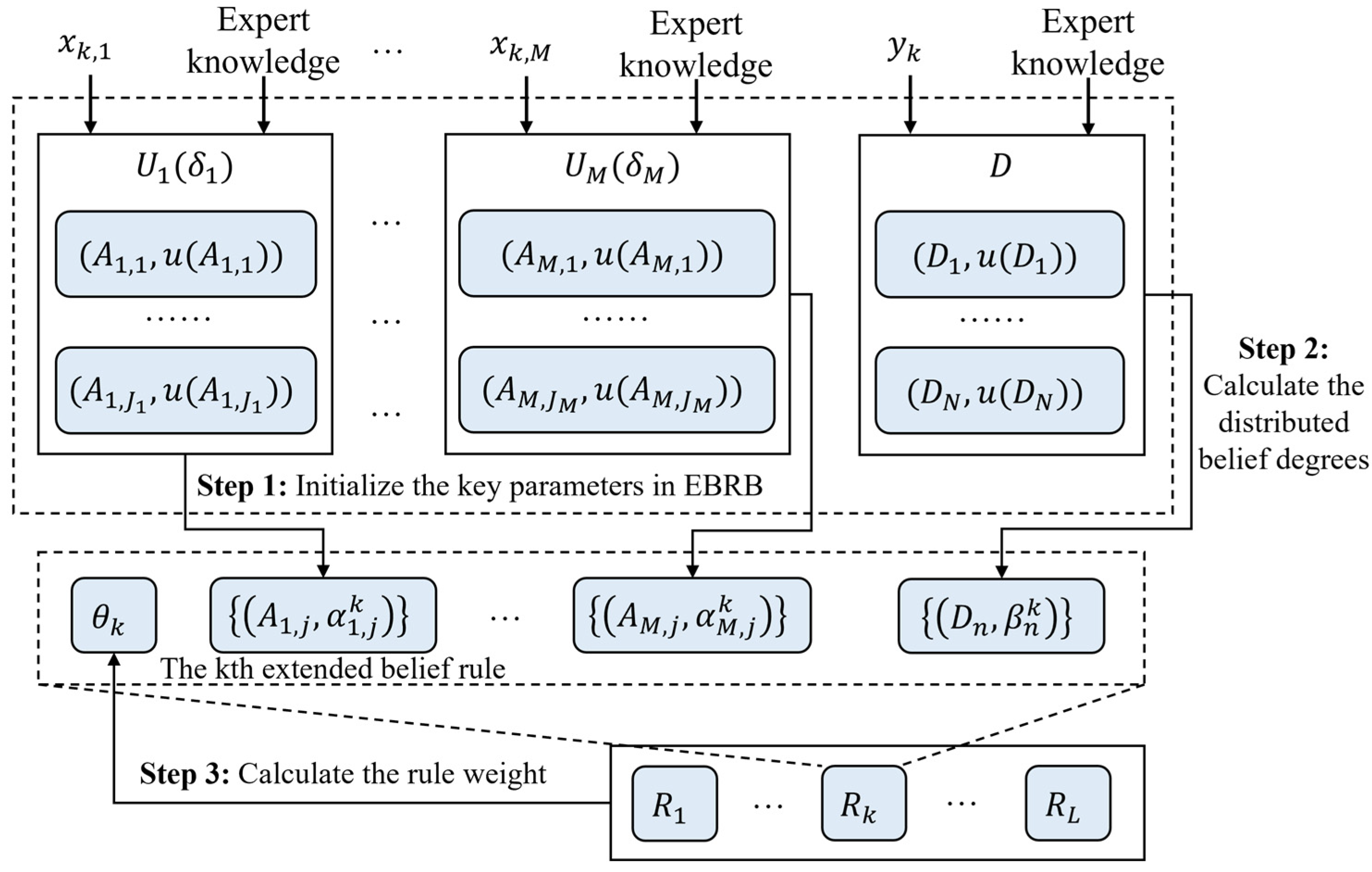

To enhance the accuracy of the driving stability assessment, the EBRB model is constructed by integrating simulation data with expert knowledge. The specific modeling process is illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

The construction process of EBRB.

Step 1: Initialize the parameter. The key initialization parameters include antecedent attributes and the number of possible values M, the utility value of all candidate levels in , the utility value of all levels and the attribute weight of the antecedent attribute.

Step 2: Calculate the distributed belief level. For the k-th sample for driving stability assessment, with as the input and as the output, the distributed belief levels of its antecedent and consequent attributes can be calculated as follows.

and

Step 3: Calculate the rule weights. The SRA (Similarity of Rule Antecedents) and SRC (Similarity of Rule Consequents) of the rule can be calculated by distributed belief degrees.

Therefore, the degree of inconsistency of the k-th rule can be expressed as

Thus, the k-th rule weight is expressed as

- (2)

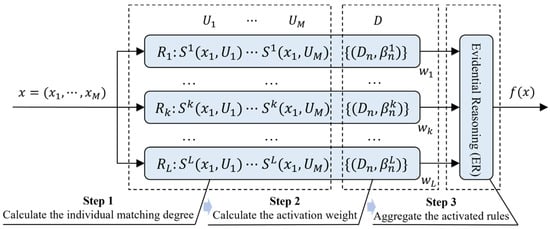

- Rule-based inference in EBRB

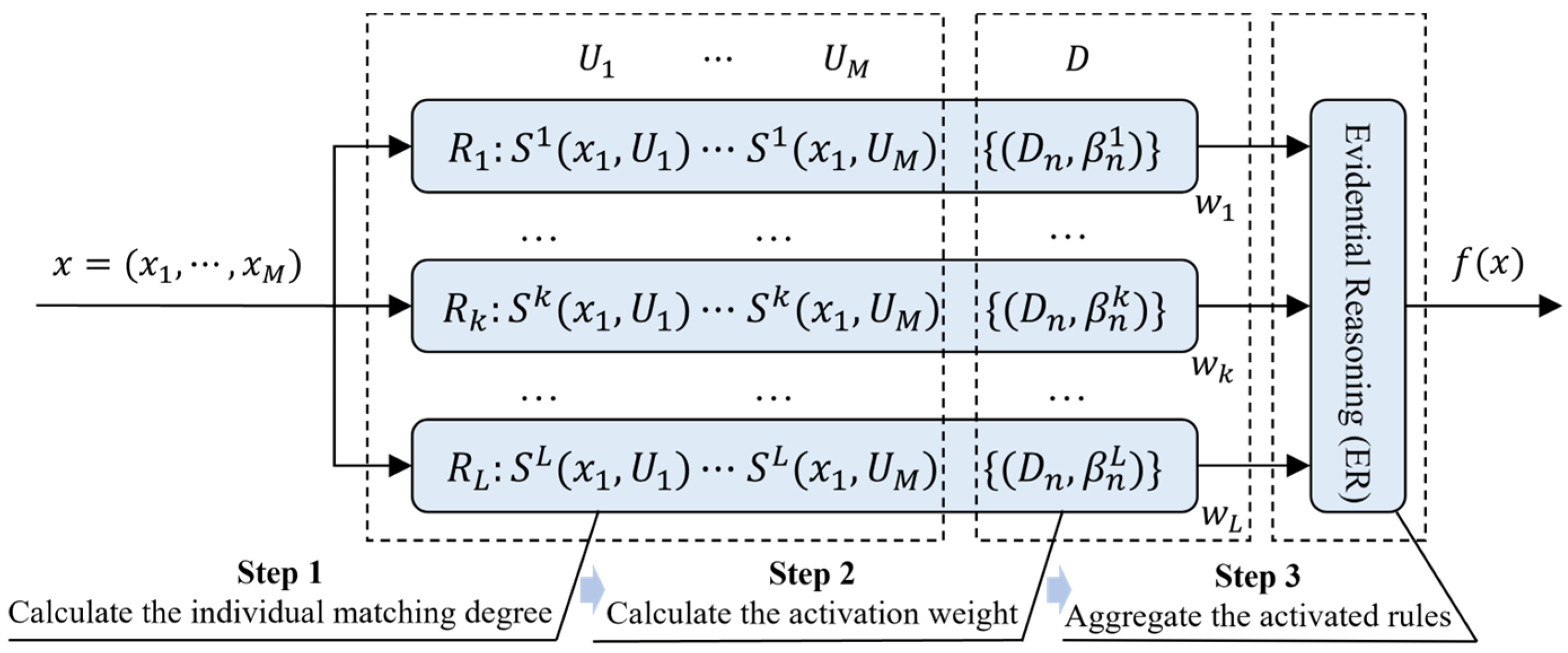

Following the construction of the EBRB, the rule inference step is conducted [64], and the basic process is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

The rule reasoning process of EBRB.

For the input data for driving stability assessment, each attribute is converted into a confidence distribution according to Equations (19) and (20), and the activation weight of the input data on the rule can be expressed as

When , it indicates that the k-th rule is an activation rule.

Rule reasoning is carried out using the evidential reasoning (ER) as follows.

where indicates the confidence level of the reasoning regarding result .

Therefore, the result utility value of input data can be expressed as

3.2. Improved EBRB Model for Driving Stability Assessment

During the EBRB construction, the initial parameter settings are usually given in advance by experts, exhibiting significant subjectivity. We introduce a parameter optimization model with reference to existing studies [65].

Assuming the driving stability assessment data , for inference result , the optimization model can be expressed as follows.

where and represent the bounds of the i-th antecedent attribute; and represent the bounds of the consequent attribute. The optimization adopts Differential Evolution (DE), with specific steps as follows.

Step 1: The candidate c in the s-th iteration can be expressed as

where is the k-th optimizable parameter; K is the number of parameters to be optimized.

The initial value of the optimizable parameter can be expressed as

Step 2: In the s-th iteration, different , and are selected from individual c to generate .

where F is the crossover factor; CR is the for variant factor.

Step 3: If the parameter of exceeds the constraint conditions, it will be reassigned according to Equation (29) and will be updated in the following way.

Step 4: The optimization terminates after s iterations, and the solution minimizing the objective function is selected as the optimized EBRB parameters.

3.3. SHAP Framework for Driving Stability Assessment

This study incorporates explainability techniques from machine learning to develop a unified framework integrating enhanced EBRB and SHAP [66]. For , the interpretation model for simplifying input can be expressed as

where M is the number of antecedent attributes; is the baseline SHAP value when all features are missing. The inputs and are associated through ; combine the conditional expectation with the SHAP value into the feature attribution metric according to the following equation [67].

where is the number of non-null samples in .

The SHAP value quantifies the average marginal contribution of a feature across all possible feature coalitions. Specifically, a positive SHAP value indicates that the feature increases the model’s prediction (a positive effect), whereas a negative value suggests a decreasing effect (a negative effect). Integrating SHAP analysis with the EBRB model significantly enhances the model’s interpretability. Based on SHAP summary and dependence plots, this approach can reveal the nonlinear relationships between various factors and driving stability. Furthermore, we can rank factor importance by the mean absolute SHAP values to identify key influences, and examine interaction effects among them using SHAP interaction values. This integration not only enhances the transparency and credibility of the EBRB model, but also provides support for safety assessment and decision-making research [68,69].

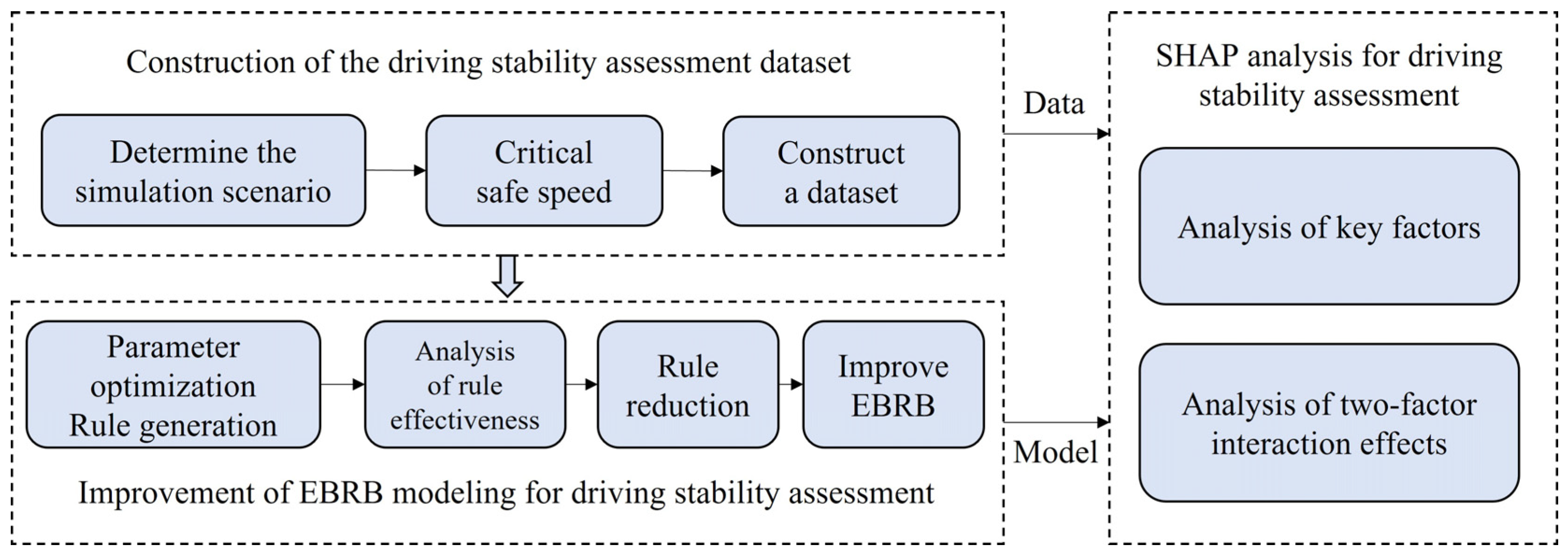

Summarizing the above research content, the framework of the interpretable driving stability assessment model DE-EBRB-SHAP proposed in this study is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Framework for driving stability assessment and interpretability based on DE-EBRB-SHAP.

4. Results

4.1. Model Parameter Settings

Experimental data are derived from the simulation results in Table 2, and 1000 samples are selected to verify the effectiveness of the proposed model. Referring to the existing research [70,71], the optimized parameter configurations are documented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Values of the main parameters of the model.

4.2. Analysis of Model Effectiveness

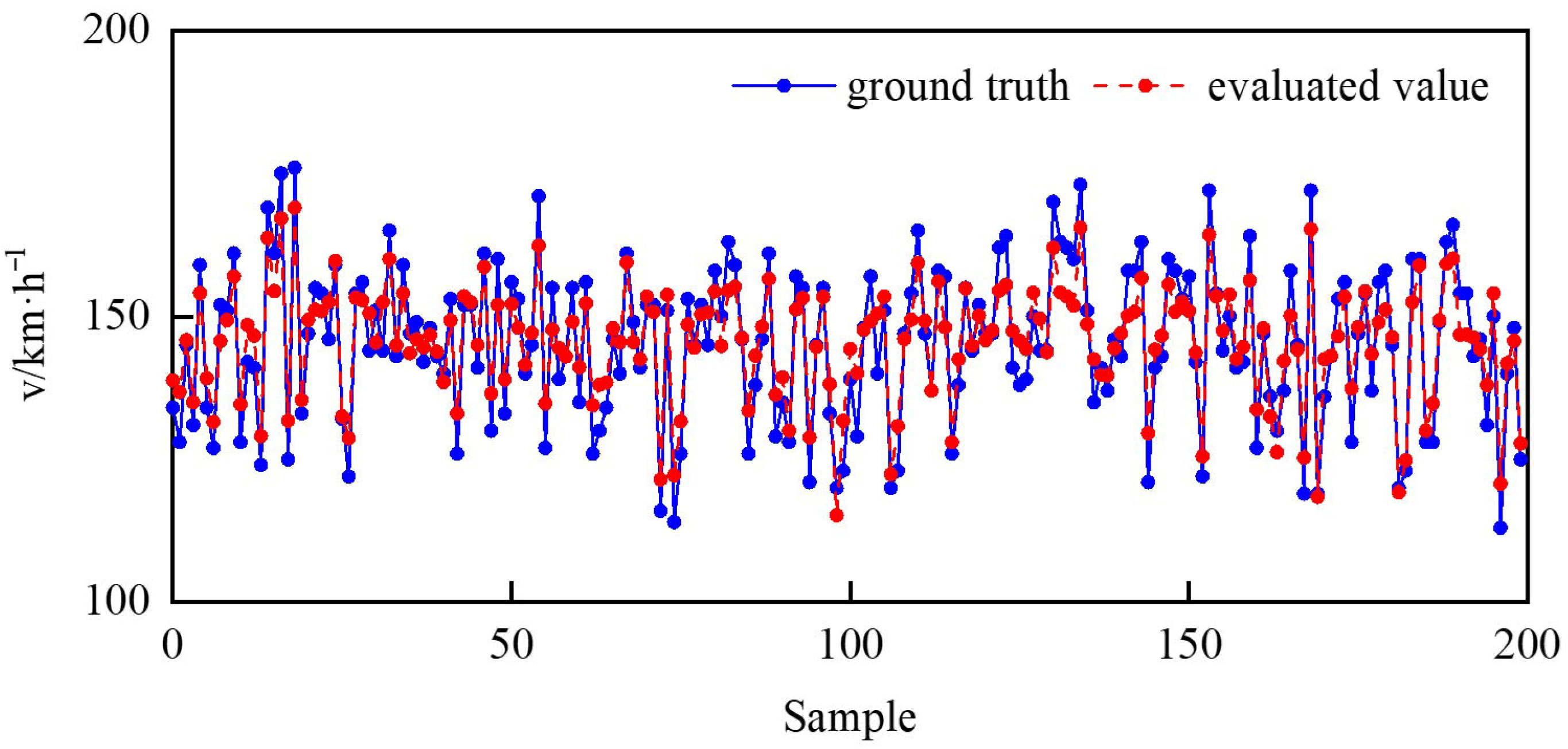

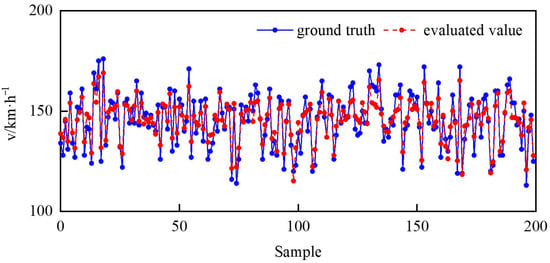

The dataset was divided into a training set and a test set with an 80/20 ratio. The comparison results between the ground truth and the evaluated value are shown in Figure 11. The accuracy of the mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) evaluation models for driving stability assessment was selected [72,73], and the calculation equation can be expressed as

where n represents the number of samples in the test set; is the true value of driving stability; represents the assessment value for driving stability.

Figure 11.

Speed assessment on curved sections.

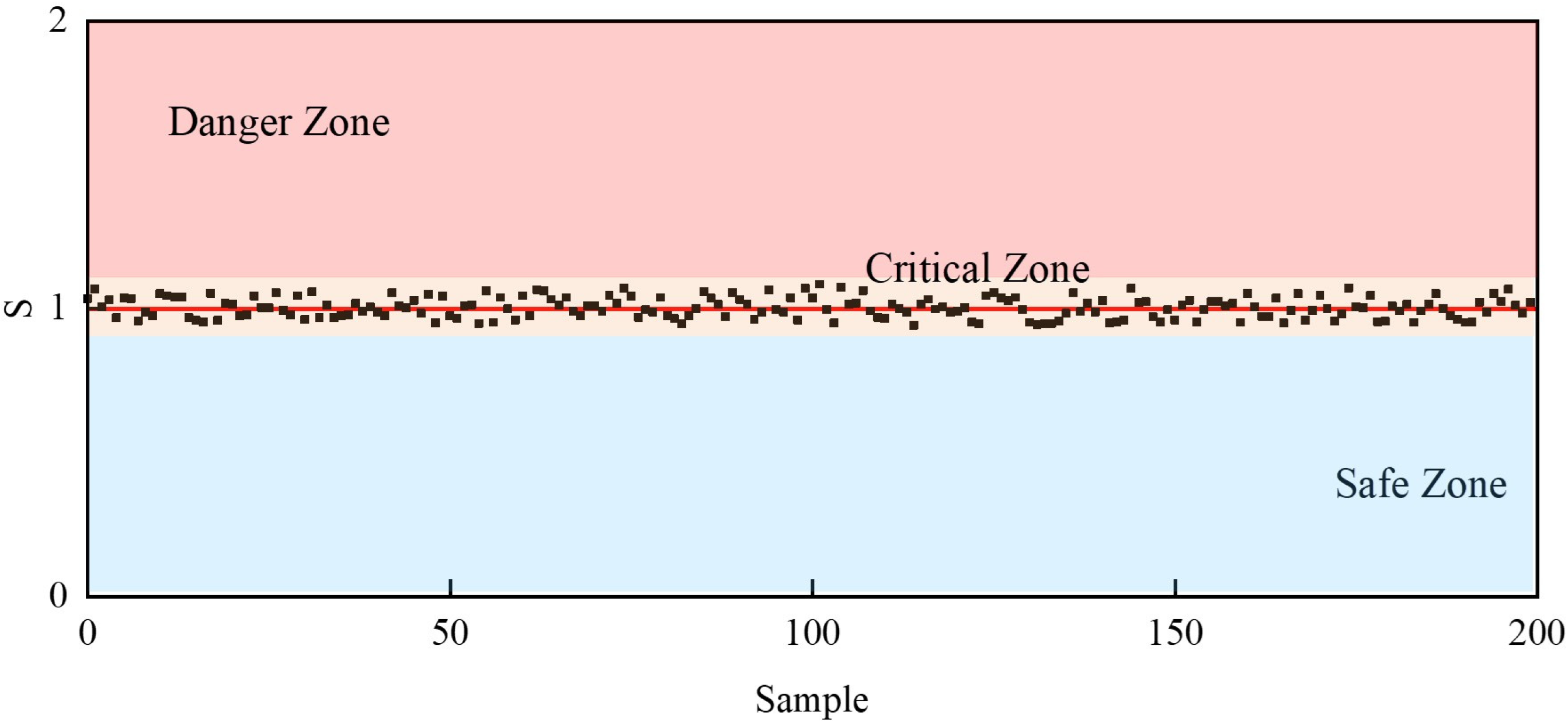

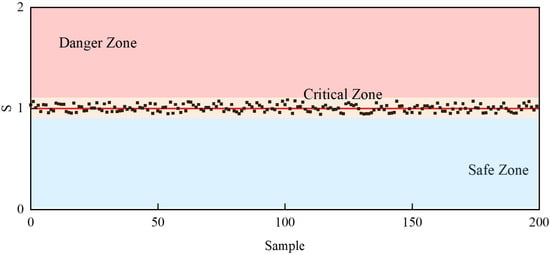

As can be seen from Figure 11, the evaluated speed closely matches the ground truth values, with the mean absolute error (MAE) of 4.39 km/h and the root mean square error (RMSE) of 5.15 km/h. The grades of stable driving states are classified as follows: {Dangerous, ; Critical, and Safe, }. Figure 12 illustrates the stability assessment results, with the red line (S = 1) indicating the vehicle stability limit states of different samples. The model’s stability assessment values show tight clustering within the [0.9, −1.1], with MAE = 0.0306 and RMSE = 0.0363. These results demonstrate the model’s capability for accurate stability prediction and assessment on curved roads through multi-source data fusion.

Figure 12.

Results of driving stability assessment.

4.3. Interpretability Analysis

- (1)

- Analysis of Factors Influencing Stability

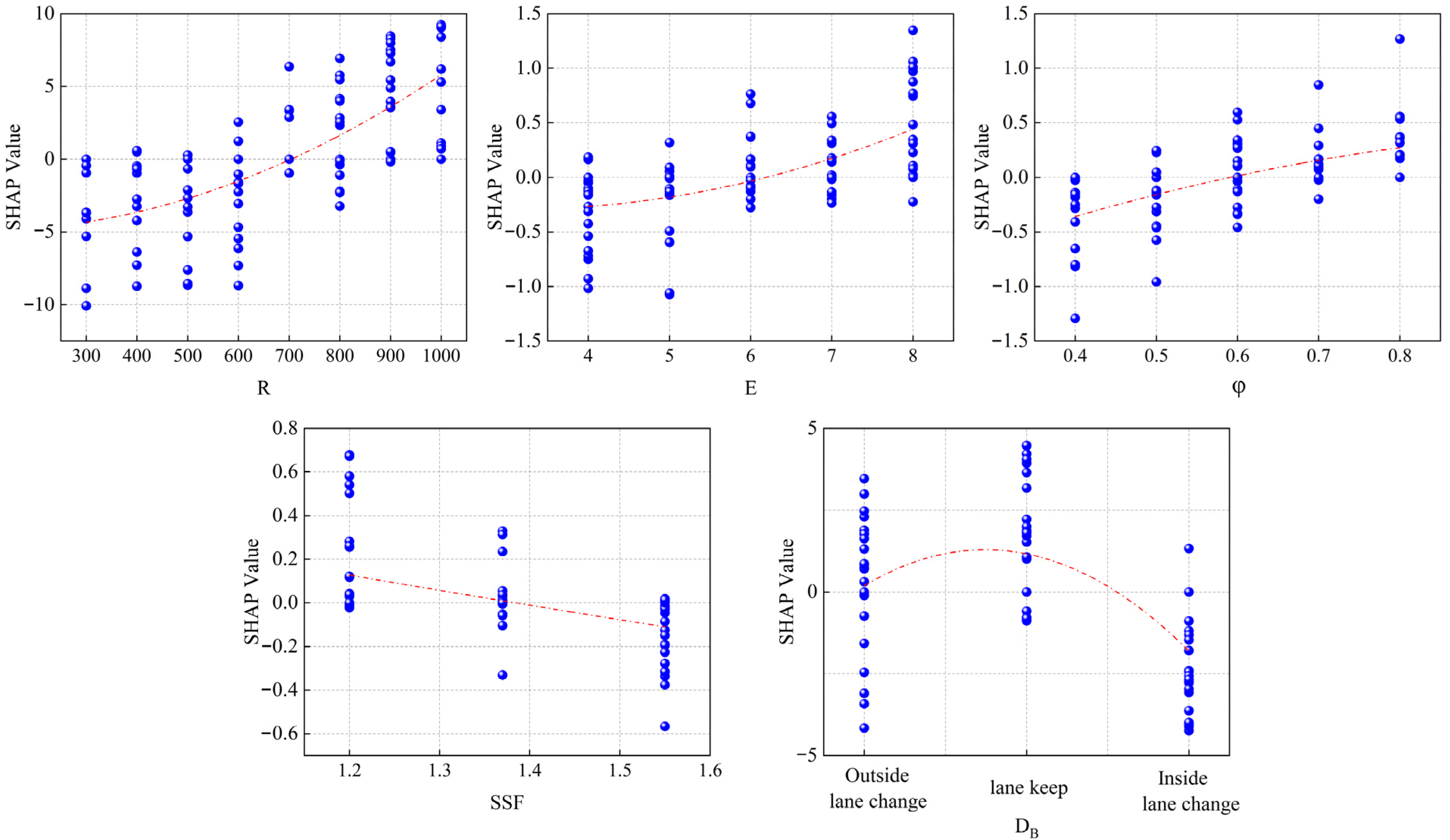

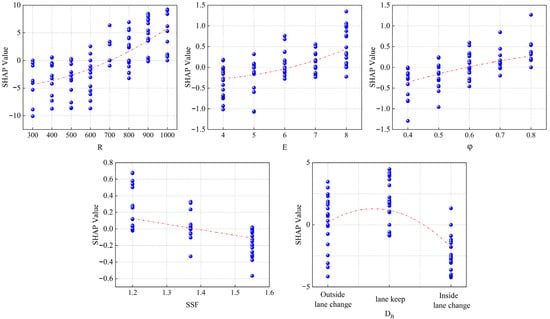

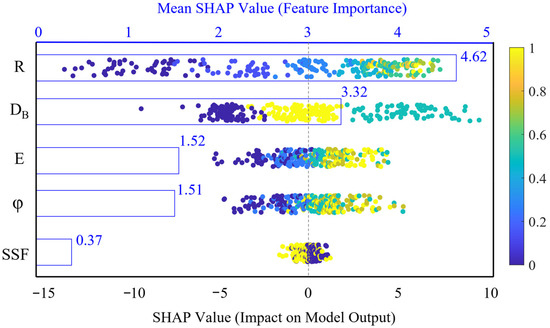

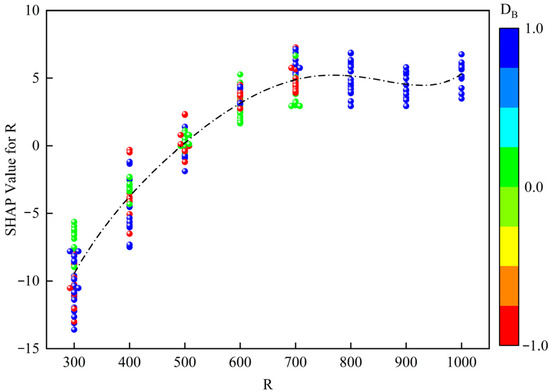

Quantifying the influence of different factors on driving stability based on SHAP values can effectively identify the dominant and secondary factors affecting stability and reveal the direction of action and nonlinear relationship of each factor; the SHAP dependence graph of different factors is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

SHAP dependence graph of different factors.

As can be seen from Figure 13, the SHAP value distribution range of the curve radius R is the largest, which is the main factor affecting driving stability. The SHAP value shows an upward trend, reflecting the strong regulatory effect of the curve radius on stability. When R = 700 m, the SHAP value is around 0, indicating that there is a positive and negative conversion of stability contribution in this vicinity, suggesting that when R exceeds 700 m, it can effectively ensure that the vehicle avoids the risk of instability. The variation range of the SHAP values of ultra-high E and the coefficient of friction φ is relatively small. Under the same value, the SHAP values both have positive and negative values, indicating that the influence of ultra-high E and the coefficient of friction on driving stability is not independent, and there is a significant interaction effect with other factors. The static stability factor SSF has a relatively weak impact on driving stability. An increase in SSF has a relatively small positive contribution to driving stability; this limited effect size is likely attributable to the narrow range of SSF values covered by the selected vehicle models in our dataset. Consistent with the existing research conclusions, the vehicle load and center of mass height on curved sections are related to the rollover stability [14]. The effect of driving behavior DB is relatively obvious. Lane-changing behavior (inward/outward) will increase the risk of instability, but the influence of inward lane changing is more significant, which is consistent with the simulation results in Figure 7.

- (2)

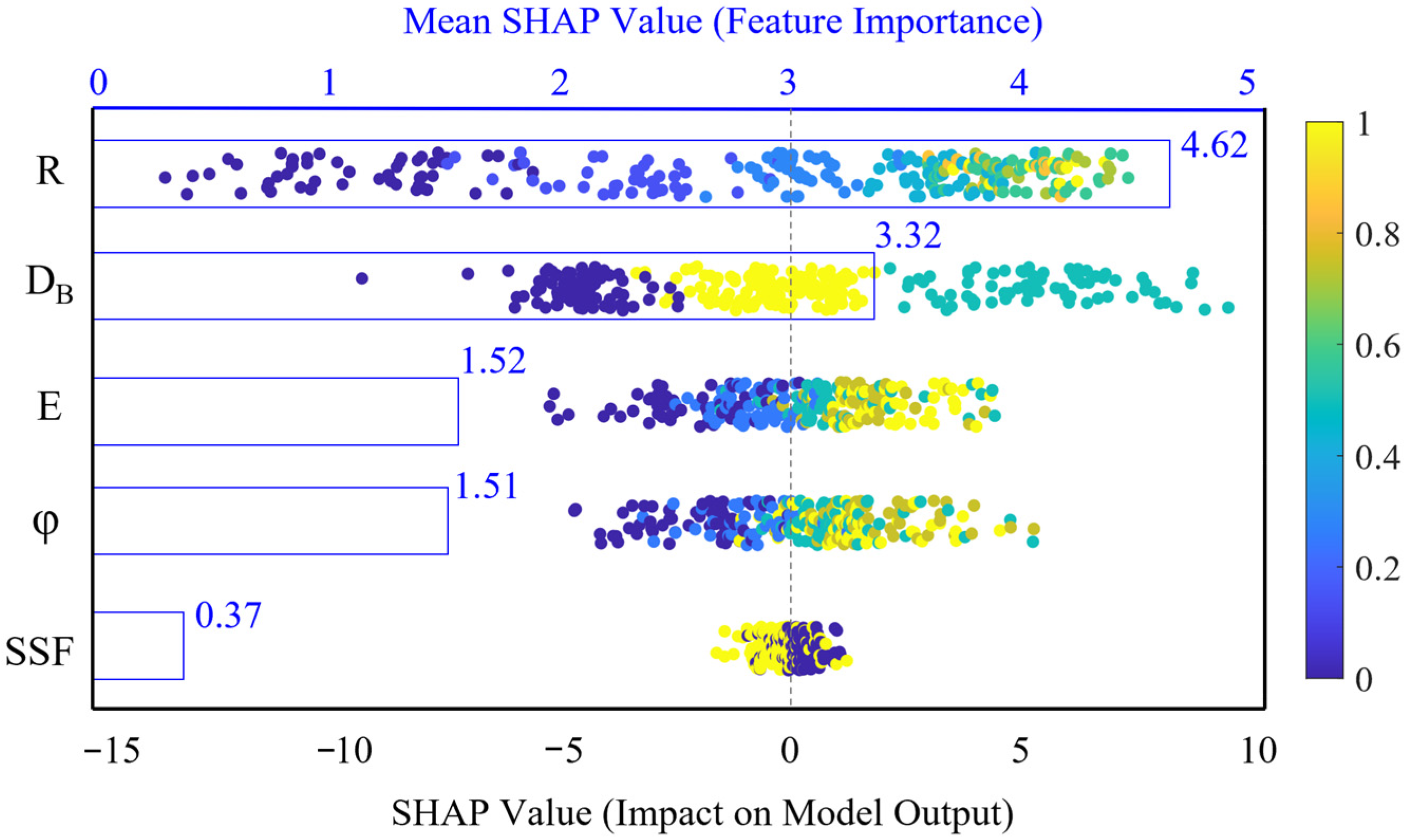

- Analysis of the importance of different factors

To enhance the interpretability of the model results, the average absolute values of SHAP for different factors were further calculated, and a honeycomb generalization graph was drawn as shown in Figure 14. The influence of different factors on the stability assessment results varies. The changes in curve radius R and driving behavior DB significantly affect the model output. E and φ have certain influences on the output results, but their importance is slightly lower. SSF exhibits the lowest importance in our model for predicting driving stability. This outcome could reflect the inherent design characteristics of the selected vehicle models, whose SSF values fall within a narrow range, thereby limiting its discriminative power in our specific simulation scenario. Existing studies have pointed out the differences in skidding among different vehicle types on curved sections [74]. Each data scatter in the figure represents a sample, and the SHAP values of different factors are randomly distributed around 0, indicating the nonlinear relationship between different factors and driving stability. Smaller values of R, E and φ will have a negative impact on the stability assessment; this negative correlation is consistent with well-documented findings in the literature [75]. The smaller the SSF, the more positive the impact it will have on the stability assessment, which is consistent with the definition in Equation (14). The SHAP honeycomb summary diagrams of different factors further reveal the primary and secondary effects of changes in different factors on driving stability.

Figure 14.

Overview diagram of SHAP honeycomb.

- (3)

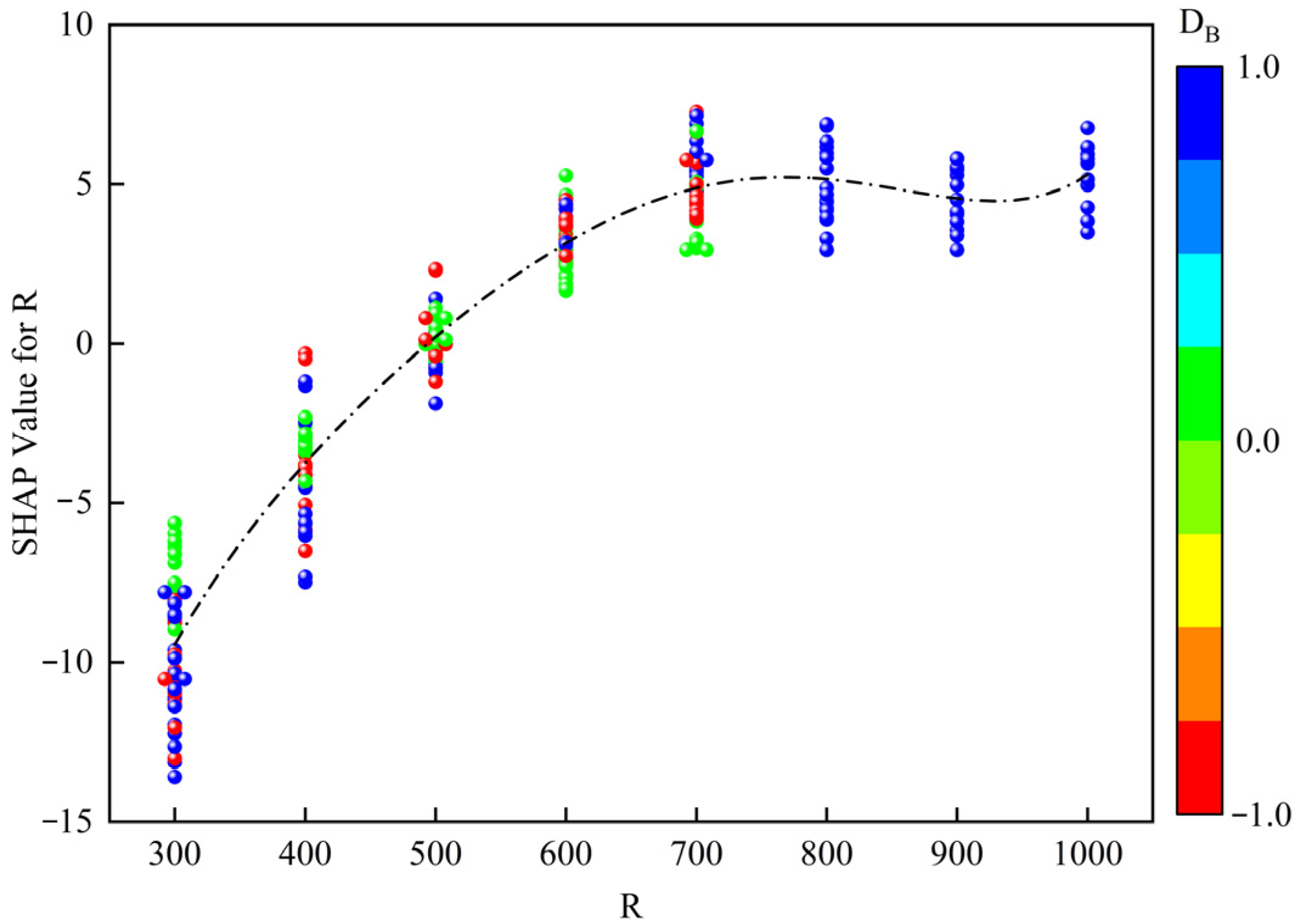

- Analysis of the interaction of the key factors

To further analyze the combined impact of the interaction effects of the key factors R and DB on the model results, a two-factor SHAP dependency graph was drawn as shown in Figure 15. When the curve radius is small, the positive impact of lane keeping (green scattered points) on the stability assessment results is greater than that of lane-changing behavior (blue and red scattered points), indicating that lane-changing behavior increases the risk of instability on small-radius curves. As the radius of the curve increases to approximately 700 m, the influence of this interaction effect gradually weakens, and the scattered points of different colors are randomly distributed. When the curve radius increases to 700 m or more, the influence of the interaction effect on the stability assessment results is no longer obvious, indicating that when the curve radius is small, lane-changing behavior will seriously affect the stability state of the vehicle. When the curve radius is greater than 700 m, the specific risk of lane-changing behavior on stability is significantly reduced.

Figure 15.

Key factor interaction effects (R and DB).

5. Discussion

Aiming at the problem of driving stability assessment with uncertain trajectories on curved road sections, this study proposes the DB-EBRB-SHAP framework by optimizing the parameters of EBRB and combining the interpretability analysis of the results. The main conclusions are as follows.

- (1)

- The trajectory changes in curved road sections increase the lateral instability of vehicles. A DE-EBRB-SHAP interpretability hybrid model was established with driving behavior as the qualitative variable. The accuracy of the proposed model was verified by constructing the dataset. The accuracy of stability assessment is MAE = 0.0306 and RMSE = 0.0363. This model innovatively incorporates driving behavior into the modeling process, enriching the reliability of driving stability assessment in complex scenarios.

- (2)

- The interpretability analysis based on SHAP reveals the intrinsic mechanism that affects driving stability. The radius of the curve and lane-changing behavior are the key factors affecting the driving stability on curved sections. For the first time, the unique interaction effect between the two was quantified: the negative impact of lane-changing behavior on driving stability on small-radius roads is more obvious. When the radius of the curve reaches 700 m or more, the interaction effect weakens. The research results will provide a basis for the study of vehicle speed management, driving behavior decision-making and trajectory planning on complex linear road sections.

- (3)

- This study provides a valuable methodological framework for the assessment of driving stability on curved road sections. However, the selection of influencing factors and the range of scenarios considered remain limited. Future research should expand the focus from single curves to more complex real-world environments, such as the S-curve. Furthermore, in the context of intelligent interconnection, it is crucial to explore how to integrate the results of this study with vehicle–road coordination technology. This integration will provide speed guidance, trajectory planning or collaborative warnings for vehicles, thereby facilitating the transition from static assessment to dynamic risk prevention and control.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.L. and T.C.; methodology, X.L. and L.Z.; software, X.L. and L.Z.; validation, X.L., L.Z. and P.Z.; formal analysis, X.L. and P.Z.; investigation, X.L., L.Z. and P.Z.; data curation, X.L., L.Z. and P.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.L. and T.C.; writing—review and editing, X.L. and T.C.; visualization, X.L., L.Z. and Y.L.; supervision, X.L., T.C. and M.W.; project administration, T.C., Y.L. and M.W.; funding acquisition, T.C., Y.L. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by General Project of Shaanxi Provincial Natural Science Basic Research Program (2025JC-YBMS-458); National Key Laboratory of Vehicle-road Integrated Intelligent Transportation (2024-B005) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (51978075).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor and reviewers for providing valuable review comments.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yang Luo was employed by the company Sichuan Cheng-Nei-Yu Expressway Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Kassu, A.; Anderson, M. Analysis of severe and non-severe traffic crashes on wet and dry highways. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2019, 2, 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, T.U.; Alinizzi, M.; Lavrenz, S.; Labi, S. Safety sensitivity to roadway characteristics: A comparison across highway classes. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooch, J.P.; Gayah, V.V.; Donnell, E.T. Safety performance functions for horizontal curves and tangents on two lane, two way rural roads. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 120, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Lu, L.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Song, M. Analysis of Accident Severity for Curved Roadways Based on Bayesian Networks. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatis, S.; Papadimitriou, E.; Psarianos, B.; Yannis, G. Vehicle skidding assessment through maximum-attainable constant-speed investigation. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2017, 143, 04017044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maljkovi´c, B.; Cvitani´c, D. Improved horizontal curve design consistency approach using steady-state bicycle model combined with realistic speeds and path radii. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2022, 148, 04022069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wen, H.; Sun, L.; Hou, W. The influence of road geometry on vehicle rollover and skidding. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaghan, V.; Pawar, D.S. A short-term naturalistic driving study on predicting comfort thresholds for horizontal curves on two-lane rural highways. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2022, 148, 04022045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Du, Z.; Zheng, H.; Xu, F.; Mei, J. Reviews and prospects of human factors research on curve driving. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 10, 808–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvik, R. The more (sharp) curves, the lower the risk. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 133, 105322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobermin, M.P.; Silva, M.M.; Ferreira, S. Driving simulators to evaluate road geometric design effects on driver behaviour: A systematic review. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Du, Z. Research status, challenges and trends of curve driving safety: A bibliometric analysis and critical review. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2025, 12, 723–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wong, Y.D.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, H.; Gao, Y. Exploring the Impact of Rainfall on Vehicle Trajectory Patterns and Sideslip Risk: An Empirical Investigation. J. Adv. Transp. 2024, 2024, 3138719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrejjal, A.; Ksaibati, K. Impact of mountainous interstate alignments and truck configurations on rollover propensity. J. Saf. Res. 2022, 80, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, T.; Tarko, A.; Tremont, P.J. The influence of combined alignments on lateral acceleration on mountainous freeways: A driving simulator study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 76, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Licea, M. On the Tripped Rollovers and Lateral Skid in Three-Wheeled Vehicles and Their Mitigation. Vehicles 2021, 3, 357–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fu, S.; Guo, L. Study on Highway Alignment Optimization Considering Rollover Stability Based on Two-Dimensional Point Collision Dynamics. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, B.; Qiao, J. Advanced High-Speed Lane Keeping System of Autonomous Vehicle with Sideslip Angle Estimation. Machines 2022, 10, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Luo, X.; Shao, Y. Vehicle trajectory at curved sections of two-lane mountain roads: A field study under natural driving conditions. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2018, 10, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Lee, H. Vehicle sideslip estimation and compensation for banked road. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2016, 17, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvasnes, S.; Pokorny, P.; Jensen, J.K.; Pitera, K. Safety Effects of Horizontal Curve Design and Lane and Shoulder Width on Single Motorcycle Accidents in Norway. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 6684334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, N.; Liu, X.C.; Zhang, G.; Porter, R.J. Impact of roadway geometric features on crash severity on rural two-lane highways. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 111, 4–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; He, J.; Zhang, C.; Xing, L.; Zhou, B. The impact of road alignment characteristics on different types of traffic accidents. J. Transp. Saf. Secur. 2020, 12, 697–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Hallmark, S.; Savolainen, P.; Dong, J. Examining vehicle operating speeds on rural two-lane curves using naturalistic driving data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 118, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrejjal, A.; Farid, A.; Ksaibati, K. A correlated random parameters approach to investigate large truck rollover crashes on mountainous interstates. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 159, 106233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolali, M.; Mirbaha, B.; Layegh, M.; Behnood, H.R. A behavioral model of drivers’ mean speed influenced by weather conditions, road geometry, and driver characteristics using a driving simulator study. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2021, 2021, 5542905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yao, J.; Zou, X.; Pu, K.; Qin, W.; Li, W. Investigating Factors Influencing Crash Severity on Mountainous Two-Lane Roads: Machine Learning Versus Statistical Models. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intini, P.; Berloco, N.; Ranieri, V.; Colonna, P. Geometric and Operational Features of Horizontal Curves with Specific Regard to Skidding Proneness. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liang, J.; Jiang, H.; Cai, Y.; Xu, X. Stability research of distributed drive electric vehicle by adaptive direct yaw moment control. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 106225–106237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, T.; Yu, S.; Shi, Q.; He, J.; Bian, Y. Setting the speed limit for highway horizontal curves: A revision of inferred design speed based on vehicle system dynamics. Saf. Sci. 2022, 151, 105729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liang, W.; Chen, Y. Stability Regions of Vehicle Lateral Dynamics: Estimation and Analysis. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control 2021, 143, 051002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Shi, S.; Liu, L.; Jin, L. Analysis of driving mode effect on vehicle stability. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2013, 14, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuraulis, V.; Surblys, V. Assessment of risky cornering on a horizontal road curve by improving vehicle suspension performance. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2021, 16, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavromatis, S.; Laiou, A.; Yannis, G. Safety assessment of control design parameters through vehicle dynamics model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 125, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, X. A Novel Control Strategy of Straight-line Driving Stability for 4WID Electric Vehicles Based on Sliding Mode Control. In Proceedings of the 2021 5th CAA International Conference on Vehicular Control and Intelligence (CVCI), Tianjin, China, 29–31 October 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nasiri, A.S.A.; Rahmani, O.; Kordani, A.A.; Karballaeezadeh, N.; Mosavi, A. Evaluation of Safety in Horizontal Curves of Roads Using a Multi-Body Dynamic Simulation Process. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Yu, L.; Ren, Y.; Li, X.; Liang, B.; Xi, J. Modeling of Tank Vehicle Rollover Risk Assessment on Curved–Slope Combination Sections for Sustainable Transportation Safety. Sustainability 2025, 17, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Xie, L.; Chu, D.; Li, L. Research on road safety evaluation in curves based on trucksim-simulink co-simulation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 392, 062157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjari, M.; Kordani, A.A.; Monajjem, S. Simulation and modelling of safety of roadways in reverse horizontal curves (RHCs): With focus on lateral friction coefficient. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 1952323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, B.; Huang, X.; Tang, J.; Chen, J.; Zhao, R.; Hong, Z.; Tang, T.; Han, M. Evaluation on braking stability of autonomous vehicles running along curved sections based on asphalt pavement adhesion properties. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 7348554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Effects of Transition Curves and Superelevation on the Critical States of Truck Rollovers on Sharp Curves. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2024, 19, 5–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.B.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Sii, H.S.; Wang, H.W. Belief rule-base inference methodology using the evidential reasoning Approach-RIMER. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern.-Part A Syst. Hum. 2006, 36, 266–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Martinez, L.; Calzada, A.; Wang, H. A novel belief rule base representation, generation and its inference methodology. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2013, 53, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.X.; Li, S.M.; Sun, G.W.; Feng, Z.C.; He, W. A fault diagnosis method for wireless sensor network nodes based on a belief rule base with adaptive attribute weights. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, S.; Sallak, M.; Schön, W.; Ming, H.X.G. A valuation-based system approach for risk assessment of belief rule-based expert systems. Inf. Sci. 2018, 466, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, G.; Li, J.; He, W.; Zhang, W.; Cao, Y. An online intrusion detection method for industrial control systems based on extended belief rule base. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2024, 23, 2491–2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsa, A.B.; Movahedi, A.; Taghipour, H.; Derrible, S.; Mohammadian, A. Toward safer highways, application of XGBoost and SHAP for real-time accident detection and feature analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2020, 136, 105405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, S.; Khattak, A.; Ullah, I.; Zhou, J.; Hussain, A. Predicting and analyzing road traffic injury severity using boosting-based ensemble learning models with shapley additive explanations. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhahir, B.; Hassan, Y. Probabilistic, safety-explicit design of horizontal curves on two-lane rural highways based on reliability analysis of naturalistic driving data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 123, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, L.; Kong, L.; Si, W. Influence of snowy and icy weather on vehicle sideslip and rollover: A simulation approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.F.; Yang, J.R.; Lu, L.P.; He, Y.; Wu, C.Z.; Zhang, C.B. Curve Speed Model Considering Coupled Effect Vehicle and Road for Preventions of Rollover and Sideslip. In Proceedings of the 2018 21st International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Maui, HI, USA, 4–7 November 2018; pp. 1358–1363. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Wu, C.Z.; Chu, D.F.; Zhong, M.; Hu, Z.Z.; Ma, J. Risk Prediction for Curve Speed Warning by Considering Human, Vehicle, and Road Factors. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2016, 2581, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, D.F.; Deng, Z.J.; He, Y.; Wu, C.Z.; Sun, C.; Lu, Z.J. Curve speed model for driver assistance based on driving style classification. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 11, 441–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M.A.; Abdelkareem, M.A.A.; Moheyeldein, M.M.; Elagouz, A.; Tan, G. Advanced study of tire characteristics and their influence on vehicle lateral stability and untripped rollover threshold. Alex. Eng. J. 2020, 59, 1613–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauriello, F.; Montella, A.; Pernetti, M.; Galante, F. An exploratory analysis of curve trajectories on two-lane rural highways. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, S.; Hui, B. Simulation analysis of the distance between tunnels at the bridge-tunnel junction of mountainous expressway on driving safety under crosswinds. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 28514–28524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, G.; He, Y.; Sun, X.; Tian, J. Modeling of lateral stability of tractor-semitrailer on combined alignments of freeway. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2018, 2018, 8438921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhsan, N.; Saifizul, A.; Ramli, R. The effect of vehicle and road conditions on rollover of commercial heavy vehicles during cornering: A simulation approach. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhou, J.; Hu, C.; Chen, W. Vehicle lateral stability control based on stability category recognition with improved brain emotional learning network. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2022, 71, 5930–5943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JTG B01-2014; Highway Engineering Technical Standards. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2014. Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/glj/202006/t20200623_3312197.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- JTG D20-2017; Highway Alignment Design Specifications. Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017. Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/glj/202006/t20200623_3312660.html (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Ye, F.F.; Yang, L.H.; Wang, Y.M.; Lu, H. A data-driven rule-based system for China’s traffic accident prediction by considering the improvement of safety efficiency. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 176, 108924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Xue, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, Z. Multi-output extended belief rule-base system and its parameter learning schemes. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Xiao, M.; Yang, L.; Tang, X.; Liang, Y.; Li, J. A minimum centre distance rule activation method for extended belief rule-based classification systems. Appl. Soft Comput. 2020, 91, 106214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Sun, J.; Guo, Y.; Tan, Y.; Jiang, J. Interpretability and accuracy trade-off in the modeling of belief rule-based systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 236, 107491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifat, M.A.K.; Kabir, A.; Huq, A. An explainable machine learning approach to traffic accident fatality prediction. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 246, 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, S.; Gao, R.; Kuang, J.; Yang, L.; Qiu, H.; Wei, X. An interpretable imbalance ensemble classification method for readmission risk assessment incorporating multi-view perturbation and SHAP analysis. Decis. Support Syst. 2025, 190, 114404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, A.; Pavel, M.A.; Titu, M.F.S.; Apurba, A.Z.; Khan, R. Hybrid ViT-RetinaNet with Explainable Ensemble Learning for Fine-Grained Vehicle Damage Classification. Vehicles 2025, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounds, C.P.; Desai, S.; Uddin, M. Enhancing CFD Predictions with Explainable Machine Learning for Aerodynamic Characteristics of Idealized Ground Vehicles. Vehicles 2024, 6, 118–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Martínez, L. New activation weight calculation and parameter optimization for extended belief rule-based system based on sensitivity analysis. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2019, 60, 837–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lan, Y.; Chen, L.; Fu, Y. A data envelopment analysis (DEA)-based method for rule reduction in extended belief-rule-based systems. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2017, 123, 174–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Gao, F.; Yang, M.; Bi, W. A new rule reduction and training method for extended belief rule base based on DBSCAN algorithm. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2020, 119, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Sun, L.; Liu, S.; Duan, W. Study on the critical rollover conditions of trucks on curved highway segments under sand-accumulated road conditions based on LSTM. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2025, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrejjal, A.; Ksaibati, K. Impact of combined alignments and adverse weather conditions on vehicle skidding. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2023, 10, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wen, H.; Sun, L.; Hou, W. Study on the influence of road geometry on vehicle lateral instability. J. Adv. Transp. 2020, 2020, 7943739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.