Abstract

This study examines the critical role of whole milk or milk replacer as a liquid diet (LD) with 15% solids in combination with different physical forms of starter as a solid diet (SD), on performance, health, and behavior of pre-weaned calves. Sixty male Holstein calves were used in a 2 × 2 factorial design, and randomly distributed into the following treatments: Whole milk powder diluted to 12.5% of solids and enriched with 25 g/L of milk replacer to achieve 15% solids, associated with either micropelleted stater (WM+micro) or texturized stater (WM+text); milk replacer diluted to 15% solids associated with either micropelleted stater (MRmicro) or texturized stater (MRtext). Starter intake and, consequently, total DMI were higher in the MRtext treatment compared to WM+micro. Calves fed texturized starter showed higher DMI, starter intake time, and rumination time. Calves in the WM+Text group showed greater ADG compared with MR treatments, regardless of starter type. Calves fed WM+ presented a lower number of days with fecal score ≥2, and the first day of diarrhea occurred at older ages. Calves fed MR showed more health challenges but similar feed efficiency with WM+, while texturized starter increased intake, eating duration, and rumination compared with micropelleted starter.

1. Introduction

Feeding management of dairy calves is a determining factor in growth rates, as well as morbidity and mortality rates, and animal welfare, which increases the economic efficiency of a herd [1]. During the pre-weaning period, which presents high daily costs and greater health challenges, animal performance is more closely associated with the dry matter intake (DMI) from the liquid diet and its composition [2]. However, for weaning to occur properly, such as maintaining growth rates, solid diet intake is extremely important [3]. Recently, NASEM [4] changed its approach to milk feeding systems. The DM intake of liquid diets, rather than their volume, is classified as high (>900 g DM/d), moderate (600–900 g DM/d), and low (400–600 g DM/d), and amounts <400 g/d are considered severely restricted. Restricted and low rates were justified for many years based on the lower daily production cost, associated with higher concentrate intake and lower occurrence of diarrhea [5]. Although the optimal amount of WM or MR to provide remains controversial, mainly because of the difficulty in the weaning process, but also because of financial evaluation, the literature [6] shows quite clearly that especially high feeding rates of liquid diets result in greater weight gain, gain efficiency, and future milk production.

Whole milk (WM) and milk replacers (MRs) are the two main sources of liquid diets (LD) used for feeding dairy calves [7]. Whole milk is a high-quality option, but with considerable nutrient fluctuation, associated with higher cost, and microbial contamination. On the other hand, MRs can be a more constant alternative, potentially simplifying management. However, their formula, regarding nutrient sources and their inclusion rate, may be a challenge for young calves intestinal health and performance [8,9]. A recent review of feeding practices in the United States [10] found that 39% of dairy operations relied solely on MR, while an additional 38.5% used MR in combination with WM. Holstein WM solids concentration is about 12.5%, and most MRs are formulated to be reconstituted to 12.5 to 15 percent solids. Increasing solids is a strategy to increase nutrient intake [11].

On the other side, the characteristics of solid diet (SD), such as ingredient and nutrient composition, particle size, processing method, and intake level, are critical factors influencing intake and, consequently, rumen development. This process depends on the input of substrate and the colonization of microorganisms [12]. Rumen fermentation by these microorganisms results in short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that stimulate cell growth and differentiation, particularly butyric (C4) and propionic (C3) acids [12,13]. Due to the importance of these two SCFAs, the solid diet for preweaning calves is based on starter feeds with a high content of non-fibrous carbohydrates. Their physical form can vary, with the most common being mashed and pelleted starters [14]. More recently, texturized starters, as well as micropelleted starters, have gained market share [15]. Mashed, pelleted, and micropelleted starters may have a high degradation rate, which can result in lower ruminal pH. It is necessary to consider the appropriate particle size in the case of mashed starters and the integrity of the pellet in the case of pelleted starters [16]. However, a meta-analysis [17] shows that texturized starters in calves diet might improve performance compared with ground or pelleted starters. Nevertheless, these authors noted that, due to the numerous discrepancies among studies, there is insufficient scientific evidence to identify a preferred starter form. The variations observed among studies can partly be attributed to differences in processing methods, grain sources, weaning ages, forage sources, particle size, liquid diet feeding programs, as well as other management practices.

We hypothesized that feeding enriched whole milk combined with a texturized starter would improve growth performance, feed efficiency, and rumination behavior, and reduce health challenges in pre-weaned calves compared with milk replacer combined with micropelleted starters.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Ethics

The Animal Research Ethics Committee of the “Luiz de Queiroz” College of Agriculture/University of São Paulo approved all procedures involving animals in this study (Protocol No. 3302140524).

2.2. Experiment Location

The study was developed at the Animal Science Department of the Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture, University of São Paulo (ESALQ/USP). Calves born on a partner commercial farm were colostrum-fed with two packets of powdered colostrum (200 g IgG; Alta Genetics, Brazil, SCCL®, Saskatoon, SK, Canada) within 2 h after birth. To ensure passive immune transfer, a handheld protein refractometer (TSPref-Instrutemp, Model ITREF 200, Sao Paulo, Brazil) was used based on [18]. Only calves with adequate passive transfer were enrolled. Calves remained on their farms of origin until 3–5 d of age, receiving milk before being transported 52 km to the Experimental Calf Unit during the cooler hours of the day (early morning or late afternoon). Upon arrival, they were housed in individual suspended pens (1.13 × 1.40 m) bedded with rubber mats and 5 cm of wood shavings, replaced daily, until 14 d of age. Calves were then moved to individual outdoor shelters placed on a grass field and restrained with a collar and chain. Shelters were repositioned each morning by twice their length to minimize contact between calves. During the first 14 d, personnel disinfected boots with lime before entering pens and avoided entry when possible. Outdoor shelters were also moved daily, and any fecal material on the ground was covered with lime. This two-stage housing system provided a controlled environment during the first two weeks while allowing greater space and controlled exposure to ticks thereafter, reducing the risk of later tick-borne disease.

2.3. Animals and Treatments

Sixty male Holstein calves were used in a 2 × 2 factorial experimental design (two sources of liquid diet and two types of starters; Table 1). Calves were blocked according to date of birth and arrival weight at the calf unit at 3–5 d, with differences within a block ≤2 kg, totaling 15 blocks. Calves were then randomly distributed into the following treatments: (1) whole milk powder diluted to 12.5% of solids and enriched with 25 g/L of milk replacer to achieve 15% solids, associated with micropelleted stater (WM+micro); (2) whole milk powder diluted to 12.5% solids enriched with 25 g/L of milk replacer to achieve 15% solids, associated with texturized stater (WM+text); (3) milk replacer diluted to 15% solids associated with micropelleted stater (MRmicro); (4) milk replacer diluted to 15% solids associated with texturized stater (MRtext). Milk replacer formulation was based on skimmed milk powder, whey powder, wheat gluten, coconut oil, palm oil, refined canola oil, minerals, and vitamins.

Table 1.

Nutritional composition of liquid and solid diets.

2.4. Feeding and Management

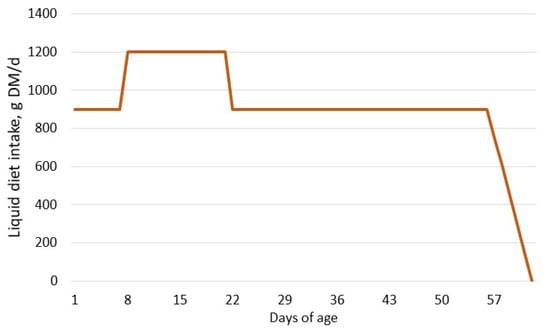

The calves were fed 6 L/d of the respective liquid diet during the first week, 8 L/d from day 8 to day 21, and again 6 L/d from day 22 to 56 days of life, when gradual weaning began by reducing 1 L/d, with complete weaning at 62 days (Figure 1). During the period in which they were fed with 8 L/d, the volume was divided into 3 meals—3 L at 7 am, 2 L at 12 pm, and 3 L at 5 pm—and in the period of supply of 6 L, the volume was divided into two meals of 3 L (7 am and 5 pm). A liquid diet was fed through nipple-buckets. Before adding milk powder to water, the temperature of the water was adjusted to 45 °C (based on the company recommendation), and by the feeding time the temperature was around 39 °C. The animals were monitored until 63 days of age.

Figure 1.

The milk feeding program used during the study.

Calves had free access to drinking water and starter since arrival at the Calf Unit. Both were provided every morning, after weighing the leftovers from the previous day to calculate starter and drinking water intake.

From 49 days of age (7th week) onwards, the calves received ad libitum medium-quality Tifton hay (13.3% CP, 77% NDF, 40.1% ADF) chopped to 2.5–3 cm, with consumption measured daily by weighing the remainder

2.5. Feed Analysis

Samples of WM, MR, and starters were collected every other week and stored at −20 °C until analysis. After thawing at room temperature, starter samples were ground in a 1 mm Wiley mill (Marconi, Piracicaba, Brazil). The DM and ash were determined according to AOAC International ([19], method 942.05). The ether extract (EE) was determined using petroleum ether ([20], method 920.39), with acidification by glacial acetic acid for the liquid diet samples. Crude protein was analyzed using the Dumas method [21] with a N analyzer (FP-528, Leco, St. Joseph, MI, USA). Teles method [22] used for measuring the lactose concentration of WM and MR powder. Neutral detergent fiber (NDF) was determined according to [23] and acid detergent fiber (ADF) according to [24], using sodium sulphite and thermo-stable amylase.

2.6. Performance, Body Measurements, and Health

Calves were weighed every week, before the morning feeding, on a mechanical scale (ICS-300; Coimma Ltd., Dracena, SP, Brazil). The hip-width and withers-height were measured using a stick ruler with a cm-scale, and the heart-girth using a tape measure. Feed efficiency was calculated as the gain-to-feed ratio. Every morning, health scores (nasal discharge, ocular discharge, ear position, cough score, rectal temperature, naval, and fecal scores were evaluated as described by the Wisconsin Health Score (https://www.vetmed.wisc.edu/fapm/svm-dairy-apps/calf-health-scorer-chs/, accessed on 30 May 2024). Fecal score regarding the fluidity of feces: (0) normal and firm, (1) semi-formed, pasty, (2) loose, but stays on top of bedding, and (3) watery, sifts through bedding. Calves with a score of 2 received oral rehydration solution (5 g of NaCl, 25 g of dextrose, and 10 g of bicarbonate/L) two hours after morning feeding, until the fecal score returned to normal (≤2). Health problems were monitored and treated according to veterinary recommendations. All treatments were registered.

2.7. Blood Sampling and Metabolites Analysis

Blood samples were collected 2 h after morning feeding on days 7, 14, 21, 28, 56, and 63 for protein and glucose analysis and on days 28, 56, and 63 for BHB, as indicators of ruminal development. The samples were collected by jugular vein puncture in two vacuumed tubes (VACUETTE do Brasil, Campinas, SP, Brazil) using a 21-gauge needle. Plasma was separated from a tube containing sodium fluoride as an antiglycolytic agent and potassium ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as an anticoagulant. Serum was collected from a tube containing a clot activator. Both samples were centrifuged at 2000× g for 20 min at 4 °C to obtain the plasma or serum, which were then stored at −20 °C for future analysis. Specific commercial enzymatic kits (Labtest Diagnóstica S.A., Lagoa Santa, Brazil) were used to analyze plasma glucose (kit ref. 85) and total serum protein (TSP; kit ref. 99). For analysis of BHB, the RANDOX Laboratories–Life Sciences Ltd. (Crumlin, UK) kit (RANBUT, kit ref.: RB1007) was used. All metabolites were measured in an automatic biochemistry system (SBA—200; CELM, Barueri, SP, Brazil).

2.8. Behavior Evaluation

All calves were monitored for 10 h by direct observation every 5 min [25]. Observation started at 7 a.m. and ended at 5 p.m. on d 49, 56, and 63, for a total observation time of 30 h per animal. Observations were recorded for standing or lying down (alert or asleep), feeding behaviors (starter, forage, drinking milk or water, and grazing), rumination, nonnutritive oral behaviors, exploring the environment, scratching themselves, urinating + defecating, and vocalization, as described at the ethogram (Table 2). The observers were trained before the trial to identify behaviors.

Table 2.

The ethogram describing the evaluated behaviors every 5 min, during a 10 h period on days 49, 56, and 63 of age of calves.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the MIXED procedure of the SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). During the interpretation and discussion of the results, a p-value ≤ 0.05 was adopted as a significant effect, and trends were discussed at p ≤ 0.10. All data were analyzed for normality of residues using the Shapiro–Wilk test, homogeneity of variances using the Levene test, and removal of outliers based on the student’s r value.

For the variables analyzed as repeated measures over time (feed intake, body weight and measures, daily gain, efficiency, fecal scores, selected blood metabolites, and behavior), the following statistical model was used:

where

Yijklm = response variable observed value;

μ = constant common to all observations;

Blocki= a random effecf of block, with = N of blocks

LDj = fixed effect of liquid diet, with = 2;

SDk = fixed effect of solid diet, with = 2;

(LD × SD)jk = first-order fixed effect of interaction between liquid and solid diet;

Agel = fixed effect of age, with = N of weeks

(LD × Age)jl = first-order fixed effect of interaction between liquid diet and age;

(LD × Age)kl = first-order fixed effect of interaction between solid diet and age;

(LD × SD × Age)jkl = second-order fixed effect of interaction among liquid diet, solid diet, and age;

δm = random effect of repeated measures for calves, with = N of calves

εijklm = random error term associated with the observation

The covariance matrices “compound symmetry, heterogeneous compound symmetry, autoregressive, heterogeneous autoregressive, unstructured, variance components, toeplitz, antidependence and heterogeneous toeplitz” were tested and defined according to the lowest value obtained for “Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected” (AICC). The subject of the repeated measures was animal within treatment.

Variables not repeated over time (initial and final body weight, and health indicators) were evaluated using the following statistical model:

where μ = overall mean; LDi = fixed effect of liquid diet (i = 1, 2); SDj = fixed effect of solid diet (j = 1, 2); (LD × SD)ij = interaction between liquid and solid diets; bj = block effect; and eij = residual error. Block was included as a random effect.

Y(ijkl) = μ + Blockl + LDi + SDj + (LD × SD)ij + ε(ijkl)

For all response variables, the means were obtained using the LSMEANS command. The comparison among treatments was performed using the Tukey test when there was significance in the analysis of variance. In the presence of the interaction between diet and age, the unfolding was performed using the SORT procedure.

3. Results

3.1. Growth Performance and Health

Table 3 presents the calves growth performance results considering the 9 weeks of evaluation. The liquid diet intake was not affected by treatments or the LD composition (enriched whole milk vs. milk replacer; p > 0.10). However, as expected, there was a significant effect of age (p < 0.01), since a step-up from 6 to 8 L daily was performed in the second week and a step-down from 8 to 6 L daily in week 4, followed by gradual liquid feeding from week 8 (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Intake and performance of dairy calves fed enriched whole milk or milk replacer associated with a micropelleted or texturized starter.

Hay intake, fed from the 49th day of the study, was also not affected by the treatments, and there was no significant effect of the factorial effects (LD or SD), age, or the treatment-age interaction (p > 0.10).

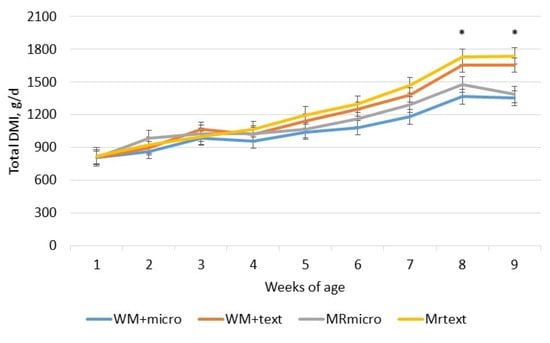

On the other hand, starter intake and, consequently, total diet intake were higher for the MRtext group compared to WM+micro (p < 0.05), while other treatments showed intermediate values (Table 3). There was also an age effect, with increasing values over the weeks and a significant interaction effect of treatment and age (p < 0.04; Figure 2), with higher intake for calves in the MRtext treatment compared to WM+micro at 8th and 9th week, and a tendency for higher intake in relation to MRmicro at 9th week. Also, at the 9th week between the WM treatments, calves significantly consumed higher texturized starter than those fed by microparticle starter (Figure 2). The SD effect was significant and showed higher starter intake (p < 0.01) and total diet intake (p < 0.01) for calves fed texturized starter.

Figure 2.

Total dry matter intake according to age of dairy calves fed two liquid diets (WM+: whole milk enriched to 15% solids with milk replacer or MR: milk replacer diluted to 15% solids) and two solid diets (micro: micropelleted or text: texturized starter). * Denotes that MRtext is different than WM+micro at weeks 8 and 9.

Drinking water intake was not affected by diet or main factors (LD or SD), but increased as calves aged (p < 0.01; Table 3).

However, even though MRtext presented higher intake than WM+micro, the average daily gain (ADG) was higher for calves in the WM+Text group compared to MR treatments, but with no differences compared to WM+micro (p < 0.05; Table 3). The LD main effect revealed higher ADG for calves fed WM compared to those fed MR (p < 0.01). As expected, there was a significant age effect for ADG (p < 0.01). However, the initial and final weights were not significantly affected by treatments or by the LD and SD factors (p > 0.10), although there was a trend (p < 0.10) for higher final weights for animals fed WM+. Despite these differences, efficiency was only affected by the age of the calves (p < 0.01; Table 3).

Gains in body measurements per week were not affected by treatments, but significantly affected by the LD factor, with greater gains in hip-width (p < 0.05) and a tendency for withers-height (p = 0.06) and heart-girth (p = 0.06) for calves fed WM+ (Table 3). The age effect was also significant for hip-width and withers-height (p < 0.01).

Animal health indicators revealed a greater challenge for calves fed milk replacer (Table 4). There was a treatment effect for fecal score, days with fecal score ≥ 2, and days to the first episode of diarrhea (p < 0.01). There was a significant effect of LD, with a higher fecal score and days with fecal score ≥2 and fewer days to the first episode of diarrhea for animals fed with MR. There was also an age effect on fecal score (p < 0.01). The fecal scores during the second and third weeks of the experiment were significantly higher than in the other weeks (p < 0.01), but decreased thereafter.

Table 4.

Health indicators of dairy calves fed enriched whole milk or milk replacer associated with a micropelleted or texturized starter.

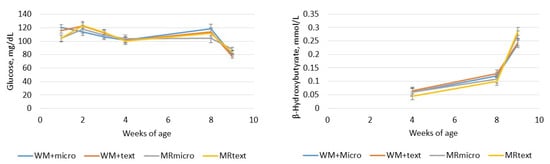

3.2. Blood Metabolites

Selected blood metabolites were not affected by treatments, as well as by LD or SD factors (p > 0.05; Table 5). However, there was a significant effect of age and the on all metabolites (p < 0.01) and a significant interaction effect of treatment and age for glucose and BHB concentration (p < 0.05; Figure 3). Protein concentration increased with age; during the first, second, and third weeks, it was significantly lower than in the 8th and 9th weeks (p < 0.05). The 4th week had protein levels significantly lower than in the 9th week; additionally, the 8th and 9th weeks showed a significant difference (p < 0.01). Glucose concentration in the 9th week was significantly lower than in other weeks (p < 0.01). β-hydroxybutyrate was measured only in the 4th, 8th, and 9th weeks as an index of rumen development, and all these weeks were significantly different (p < 0.01).

Table 5.

Metabolite concentration in dairy calves fed enriched whole milk or milk replacer associated with a micropelleted or texturized starter.

Figure 3.

Plasma glucose and β-hydroxybutyrate concentrations according to age of dairy calves fed two different liquid diets (WM+: whole milk enriched to 15% solids with milk replacer or MR: milk replacer diluted to 15% solids) and two solid diets (micro: micropelleted or text: texturized starter). N = 15 calves/treatment.

3.3. Behavior

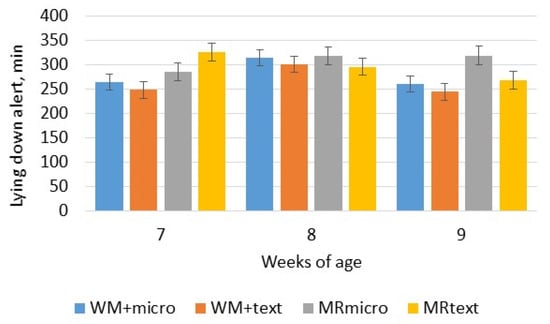

Calves’ behavior was assessed at weeks 7, 8, and 9 of age with the aim of understanding changes, especially during the transition period (Table 6). Most of the behavioral repertoire was affected by calves age, but there was no significant treatment effect (p > 0.05). However, there was a significant treatment and age interaction effect for time lying down alert (p < 0.01) and a trend for time performing non-nutritive suckling (p < 0.10). Unfolding of the analysis shows that there was no difference between treatments within a specific week (Figure 4). There was an LD effect trend for time lying down alert (p < 0.05), with greater time for animals fed with milk replacer (Table 5). Hay intake time was higher at the 7th week (first day of receiving forage) than the next two weeks (p < 0.01). The SD factor resulted in a significant effect for rumination time (p < 0.05), with greater time for calves receiving texturized starter. There was also a trend towards longer time for starter intake for calves receiving texturized starter (p < 0.10). Grazing and vocalization time were significantly higher in the 9th week, when licking themselves decreased at the 9th week (p < 0.01). Exploring environment time was also affected by calves age, which was significantly different between weeks. The time calves spent exploring their environment was also affected by age. It was highest at week 7, dropped a bit in week 8, and was lowest by week 9 (p < 0.01).

Table 6.

Behavior (min/10 h of observation) was evaluated at weeks 7th, 8th, and 9th of age of dairy calves fed enriched whole milk or milk replacer associated with a micropelleted or texturized starter.

Figure 4.

Time (min/10 h of observation) spent lying down alert by dairy calves fed two different liquid diets (WM+: whole milk enriched to 15% solids with milk replacer or MR: milk replacer diluted to 15% solids) and two solid diets (micro: micropelleted or text: texturized starter). N = 15 calves/treatment.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of different liquid diet sources with 15% of solids (whole milk enriched with 25 g/L of milk replacer to reach 15% solids vs. milk replacer with 15% solids) and two different starter sources (micropelleted vs. texturized) on the performance, health, and behavior of dairy calves. During the first 21 days of life, calves rely on a liquid diet because their rumen and digestive systems are not yet functionally developed enough to degrade and digest solid feeds [26]. The starter intake during the first days of the calf′s life is negligible, but gradually increases, triggering rumen development [27]. Consequently, the type of liquid or solid diet during this critical phase may have a significant effect on subsequent milk yield [28,29]. NASEM [4] suggested that milk feeding programs providing less than 600 g DM/d, equivalent to 4.8 L/d when the diet has 12.5% solids, would be a low or severely restricted feeding programs (<400 g DM/d). Rates of 600 to 900 g DM/d would be considered moderate feeding rates, and when >900 g DM/d are fed, high feeding rates. While low feeding programs are justified by the reduced daily cost and higher starter intake, they do not increase ADG [30,31], which influences future milk production [6]. In the present study, dry matter intake from the liquid diet was 822.6 g/d, with no significant difference among treatments, showing that the whole milk enrichment strategy or dilution of the milk replacer to 15% solids had no impact on liquid diet intake.

In the current study, there was an increase in calf starter intake as calves aged, with the average starter intake being similar to that presented by others [32]. The average starter intake was higher for calves fed MRtext as compared to WM+micro; and there was a clear effect of the SD on starter intake. There is a negative correlation between LD and SD intake, and because the digestibility of nutrients from whole milk is higher than that from MR, this may have caused a decrease in starter intake [6]. Between starters, there was a higher intake and consequently total DMI for calves fed Text, probably because of its higher NDF content and lower risk of rumen acidosis [28]. Greater acceptability of the texturized starter could also have caused this distinction. Proper starter feed intake is crucial for the timely development of a functional rumen and a smooth weaning process, reducing weaning-related stresses [15]. Starter intake varied widely among studies, which can be partially explained by differences in processing methods, grain source, milk feeding programs, age at weaning, forage source, particle size, and management practices [15,33]. Some reasons have been mentioned for the superior texturized starters, including enhanced rumen development and buffering [34,35], greater total tract digestibility of nutrients [36], improved intake and growth in early post-weaning [35], better intestinal morphology and enzyme activity [37], and superior feed efficiency [38].

On the other hand, in this study, ADG was higher for calves receiving enriched whole milk combined with texturized starter (WM+text) as compared to both treatments with MR. The effect of the LD factor (p < 0.01) confirms that the liquid diet explains most of the performance during the preweaning phase. There was also a significant effect of LD on body measurement gains, showing that enriched whole milk has superiority in growth responses that go beyond ADG.

Assessments of health indicators suggest that calves fed with milk replacer had a greater health challenge, with an increasing number of days characterized by more fluid feces and diarrhea occurring at younger ages. These results are common in animals fed with milk replacer, which often, in addition to having lower protein and energy content, contains non-dairy ingredients that result in intestinal challenge, increasing morbidity and mortality rates [39].

In the current study MR-fed calves had about 10 d more with fecal score ≥2 index and diarrhea occurring in younger ages than the whole milk-fed calves. The quality of the liquid diet provided is essential to ensure maximized performance. In the first three weeks of life, the calf should be fed a milk replacer containing preferably a source of milk proteins, or proteins processed for high digestibility in very young animals. Not only the quantity of protein, but also the quality of the protein source is important for calf nutrition [40]. In this study, the protein source of the milk replacer was a combination of animal and vegetable origins, and it contained 4% more lactose than whole milk, which could be a potential cause of intestinal challenges. Many studies have reported a negative association between diarrhea and ADG [41,42], as demonstrated in this study. However, the final weight was not statistically significant among the treatments.

There was no effect of treatments or evaluated main factors (LD and SD) on blood concentrations of protein, glucose, and BHB; however, the significant interaction of treatment and age observed for glucose and BHB was not associated with differences within a particular week of age. Differences in metabolite concentrations occurred as a function of the age of the animals, with the expected decrease in glucose concentration and increase in BHB concentration, characteristic of this period, and showing the transition from pre-ruminant to functional ruminant animal [43,44]. During the first weeks of life, plasma glucose concentrations in calves is around 100 mg/dL, but they gradually decrease to close to 60 mg/dL, characteristic of adult ruminants, as the rumen develops. In general, plasma glucose concentrations are reduced, while concentrations of SCFA and BHBA increase, concomitantly with an increase in starter intake and consequent ruminal development [45,46,47]. Several studies have reported variations in blood glucose and BHBA levels in response to different treatments. In this investigation, the blood glucose concentration across all treatments remained consistent from the first to the seventh week, averaging approximately 110 mg/dL. At week 9, blood glucose concentration decreased, indicating ruminal activity and the use of SCFA as energy by calves. This suggests that all treatments supplied similar amounts of energy to the calves. Conversely, BHB concentrations exhibited a gradual increase from the 4th to 8th week, with a more pronounced rise observed in the 9th week. No significant differences in glucose and BHB levels were detected among the treatments, which may indicate uniform rumen development across all dietary groups.

The behavior of the calves was not affected by treatment, but SD main effect affected time spent ruminating, while time lying down and alert was affected by the LD. Increased lying time is associated with improved comfort, while reduced lying time may signal discomfort or stress [48,49,50]. Calves fed with milk replacer spent more time lying down alert, which may represent more idle time when combined with time sleeping. In general, ensuring that dairy calves have sufficient opportunities to lie down comfortably is vital for their growth and welfare. However, this result needs to be carefully evaluated, since these calves had an increased health challenge and may have spent more time lying down because they were not in good health.

Calves fed with texturized starter spent more time-consuming starter (p < 0.07) and ruminating, again suggesting that microplleted starter has lower acceptability and that NDF stimulates rumination. Rumination time can be used as a relevant marker in evaluating rumen development, health, and welfare in calves [51]). The physical form of the starter can promote rumination time in calves [15]. Calves fed texturized starter, which includes whole kernel corn and pelleted ingredients, began ruminating by 4 weeks of age and spent approximately 21% of their time ruminating. In contrast, calves fed pelleted starter did not begin ruminating until 6 weeks, and spent only about 9% of their time ruminating [52]. Increased particle size of starter by adding chopped hay (85% concentrate, 15% chopped hay) increased feeding and rumination time during weaning, but its effect was not significant during post-weaning. In the present study, rumination time was significantly higher for calves fed with texturized starter. However, the duration of starter intake after weaning increased significantly compared to the pre-weaning and weaning periods. This suggests that the weaning program was effectively implemented and that the calves were adequately prepared for this transition. The increased starter intake post-weaning indicates their ability to meet the necessary dry matter requirement by the starter. Interestingly, even with the differences in the physical form and NDF contents of the starters, there was no impact on hay intake or time eating hay before or after weaning.

5. Conclusions

Feeding enriched whole milk or milk replacer at 15% solids, together with distinct starter physical forms, shaped calf performance, health, and behavior in meaningful ways. Enriched whole milk paired with a texturized starter maximized growth, while milk replacer increased health challenges without impairing feed efficiency. Starter physical form modulated intake dynamics and rumination, with texturized starter consistently promoting greater engagement. These results underscore that decisions on liquid and solid diets must balance biological responses with economic and operational considerations. All evaluated diet combinations remain viable options for diverse production settings, particularly when accounting for ingredient costs and the skill required for consistent milk replacer preparation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.M.B.; methodology, C.M.M.B., M.H.M., C.R.T., J.M.F., E.D.M.; validation, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., C.R.T., E.D.M., J.M.F., J.R.A.-C., I.C.R.d.O., N.I.C.; formal analysis, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., J.R.A.-C.; investigation, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., C.R.T., E.D.M., J.M.F., J.R.A.-C., I.C.R.d.O., N.I.C.; resources, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., C.R.T.; data curation, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., C.R.T., E.D.M., J.M.F., J.R.A.-C., I.C.R.d.O., N.I.C.; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.M.B., M.H.M.; writing—review and editing, C.M.M.B.; visualization, M.H.M., C.M.M.B., C.R.T., E.D.M., J.M.F., J.R.A.-C., I.C.R.d.O., N.I.C.; supervision, C.M.M.B.; project administration, C.M.M.B.; funding acquisition, C.M.M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Agrifirm do Brasil, with the administrative support of FEALQ (Luiz de Queiroz Agrarian Study Foundation); Project 104907.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures with calves were performed per the guidelines and regulations approved by the ‘Luiz de Queiroz’ College of Agriculture (ESALQ), University of São Paulo (USP), Brazil. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all procedures involving animals in this study (Protocol No. 3302140524).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions by the research group.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior-Brasil (CAPES), and to the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the scholarship of several authors. We are also thankful to Agrifirm do Brasil for the financial support of this study and the Luiz de Queiroz Agrarian Study Foundation (FEALQ) for the administrative support for this project. The authors would also like to acknowledge the support from Luiz de Queiroz College of Agriculture and the technical help provided by their co-workers.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| WM | Whole milk |

| MR | Milk replacer |

| Multi | Multiparticle |

| Micro | Microparticle |

| DM | Dry matter |

| DMI | Dry matter intake |

| SCFA | Short chain fatty acid |

| EE | Ether extract |

| NDF | Natural detergent fiber |

| ADF | Acid detergent fiber |

| ADG | Average daily gain |

| BHB | β-hydroxybutyrate |

| LD | Liquid diet |

| SD | Solid diet |

References

- Verdon, M.; Tilbrook, A. A review of factors affecting the welfare of dairy calves in pasture-based production systems. Anim. Prod. Sci. 2021, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gercino Ferreira Virgínio, J.; Duranton, C.A.J.; de Paula, M.R.; Bittar, C.M.M. Impact of different levels of lactose and total solids of the liquid diet on calf performance, health, and blood metabolites. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benetton, J.; Neave, H.; Costa, J.H.; Von Keyserlingk, M.; Weary, D. Automatic weaning based on individual solid feed intake: Effects on behavior and performance of dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 5475–5491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle; Nutrient Requirements of Dairy Cattle: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Weary, D.; Von Keyserlingk, M. Invited review: Effects of milk ration on solid feed intake, weaning, and performance in dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 1071–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soberon, F. Early Life Nutrition of Dairy Calves and Its Implications on Future Milk Production. Ph.D. Thesis, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, G.d.; Bittar, C.M.M. A survey of dairy calf management practices in some producing regions in Brazil. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 2015, 44, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittar, C.M.M.; Silva, J.T.d.; Chester-Jones, H. Macronutrient and amino acids composition of milk replacers for dairy calves. Rev. Bras. Saúde Produção Anim. 2018, 19, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosson, K.; Hopkins, B.; Washburn, S.; Davidson, S.; Smith, G.; Earleywine, T.; Ma, C. Effect of supplementing pasteurized milk balancer products to heat-treated whole milk on the growth and health of dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 1127–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urie, N.; Lombard, J.; Shivley, C.; Kopral, C.; Adams, A.; Earleywine, T.; Olson, J.; Garry, F. Preweaned heifer management on US dairy operations: Part I. Descriptive characteristics of preweaned heifer raising practices. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 9168–9184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R.; Lage, C.; Silper, B.; Neto, H.D.; Quigley, J.; Coelho, S. Invited review: Total solids concentration in milk or milk replacer for dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2023, 106, 7341–7351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diao, Q.; Zhang, R.; Fu, T. Review of strategies to promote rumen development in calves. Animals 2019, 9, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, A.; Trabi, E.B.; Zhu, C.; Mao, S. Role of butyrate as part of milk replacer and starter diet on intestinal development in pre-weaned calves. A systematic review. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2022, 292, 115423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Júnior, G.F.V.; Bittar, C.M.M. Microbial colonization of the gastrointestinal tract of dairy calves–a review of its importance and relationship to health and performance. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2021, 22, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, A.; Alimirzaei, M. Physical Form of Calf Starter: Applied Metabolic and Performance Insights. Iran. J. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2023, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Nilieh, M.; Kazemi-Bonchenari, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Khodaei-Motlagh, M. Interaction effect of starter physical form and alfalfa hay on growth performance, ruminal fermentation, and blood metabolites in Holstein calves. J. Livest. Sci. Technol. 2018, 6, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaffari, M.H.; Kertz, A.F. Effects of different forms of calf starters on feed intake and growth rate: A systematic review and Bayesian meta-analysis of studies from 1938 to 2021. Appl. Anim. Sci. 2021, 37, 273–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, M.H.; Rocha, N.B.; de Paula, M.R.; Miqueo, E.; Salles, M.S.V.; Rodrigues, P.H.M.; Bittar, C.M.M. Effect of Blood Sampling Time After Colostrum Intake on the Concentration of Metabolites Indicative of the Passive Immunity Transfer in Newborn Dairy Calves. Animals 2024, 14, 3133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International. AOAC 2005. Available online: https://www.studocu.vn/vn/document/truong-dai-hoc-vinh/co-so-du-lieu/official-methods-of-analysis-of-aoac-international-18th-ed-2005/138442576 (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 17th ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wiles, P.G.; Gray, I.K.; Kissling, R.C.; Delahanty, C.; Evers, J.; Greenwood, K.; Grimshaw, K.; Hibbert, M.; Kelly, K.; Luckin, H.; et al. Routine analysis of proteins by Kjeldahl and Dumas methods: Review and interlaboratory study using dairy products. J. AOAC Int. 1998, 81, 620–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, F.F.; Young, C.K.; Stull, J. A method for rapid determination of lactose. J. Dairy Sci. 1978, 61, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.v.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Methods for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.K.; Van Soest, P.J. Forage Fiber Analyses (Apparatus, Reagents, Procedures, and Some Applications); US Agricultural Research Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Cushon, E.; DeVries, T. Validation of methodology for characterization of feeding behavior in dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 6103–6110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alugongo, G.M.; Xiao, J.; Azarfar, A.; Liu, S.; Yousif, M.H.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Cao, Z. Effects of milk feeding strategy and acidification on growth performance, metabolic traits, oxidative stress, and health of holstein calves. Front. Anim. Sci. 2022, 3, 822707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drackley, J.K. Calf nutrition from birth to breeding. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 2008, 24, 55–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelsinger, S.; Heinrichs, A.; Jones, C. A meta-analysis of the effects of preweaned calf nutrition and growth on first-lactation performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 6206–6214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rauba, J.; Heins, B.; Chester-Jones, H.; Diaz, H.; Ziegler, D.; Linn, J.; Broadwater, N. Relationships between protein and energy consumed from milk replacer and starter and calf growth and first-lactation production of Holstein dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiezebrink, D.; Edwards, A.; Wright, T.; Cant, J.; Osborne, V. Effect of enhanced whole-milk feeding in calves on subsequent first-lactation performance. J. Dairy Sci. 2015, 98, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberger, K.; Costa, J.H.; Neave, H.; Von Keyserlingk, M.; Weary, D. The effect of milk allowance on behavior and weight gains in dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazoki, A.; Ghorbani, G.; Kargar, S.; Sadeghi-Sefidmazgi, A.; Drackley, J.; Ghaffari, M. Growth performance, nutrient digestibility, ruminal fermentation, and rumen development of calves during transition from liquid to solid feed: Effects of physical form of starter feed and forage provision. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2017, 234, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, G.; McGregor Argo, C.; Jones, D.; Grove-White, D. The impact of early life nutrition and housing on growth and reproduction in dairy cattle. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, Í.R.; Leite, G.B.C.; Carrari, I.F.; Silva, L.; Chagas, J.C.C.; More, D.D.; Marcondes, M.I. Effects of the physical form of starter feed on the intake, performance, and health of female Holstein calves. Animal 2025, 19, 101400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, J.G.; Torbatinejad, N.; Naserian, A.A.; Kumar, S.; Kim, J.; Song, Y.; Ra, C.; Sung, K. Effects of processing of starter diets on performance, nutrient digestibility, rumen biochemical parameters and body measurements of Brown Swiss dairy calves. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 980. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, J. Symposium review: Re-evaluation of National Research Council energy estimates in calf starters. J. Dairy Sci. 2019, 102, 3674–3683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cai, X.; Liu, P.; Li, C. Effects of physical forms of starter feed on growth, nutrient digestibility, gastrointestinal enzyme activity, and morphology of pre-and post-weaning lambs. Animal 2021, 15, 100044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Quigley, J.; Hill, T.; Dennis, T.; Suarez-Mena, F.; Schlotterbeck, R. Effects of feeding milk replacer at 2 rates with pelleted, low-starch or texturized, high-starch starters on calf performance and digestion. J. Dairy Sci. 2018, 101, 5937–5948. [Google Scholar]

- Tomkins, T.; Jaster, E. Preruminant calf nutrition. Vet. Clin. N. Am. Food Anim. Pract. 1991, 7, 557–576. [Google Scholar]

- Eriso, M.; Mekuriya, M. Milk Replacer Feeds and Feeding Systems for Sustainable Calf Rearing: A Comprehensive Review and Analysis. Stud. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2023, 2, 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardon, B.; Hostens, M.; Duchateau, L.; Dewulf, J.; De Bleecker, K.; Deprez, P. Impact of respiratory disease, diarrhea, otitis and arthritis on mortality and carcass traits in white veal calves. BMC Vet. Res. 2013, 9, 79. [Google Scholar]

- Schinwald, M.; Creutzinger, K.; Keunen, A.; Winder, C.; Haley, D.; Renaud, D. Predictors of diarrhea, mortality, and weight gain in male dairy calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2022, 105, 5296–5309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, L.; Bittar, C.M.M. Performance and plasma metabolites of dairy calves fed starter containing sodium butyrate, calcium propionate or sodium monensin. Animal 2011, 5, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezapour, M.; Chashnidel, Y.; Dirandeh, E.; Shohreh, B.; Ghaffari, A. The effect of grain processing and grain source on performance, rumen fermentation and selected blood metabolites of Holstein calves. J. Anim. Feed. Sci. 2016, 25, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, C.; Ma, L.; Zhen, Y.; Kertz, A.; Zhang, W.; Bu, D. Effects of different physical forms of starter on digestibility, growth, health, selected rumen parameters and blood metabolites in Holstein calves. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2021, 271, 114759. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, B.; Van Reenen, C.; Gerrits, W.; Stockhofe, N.; Van Vuuren, A.; Dijkstra, J. Effects of supplementing concentrates differing in carbohydrate composition in veal calf diets: II. Rumen development. J. Dairy Sci. 2006, 89, 4376–4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmasbi, A.M.; Abadi, S.H.J.; Naserian, A.A. The effect of 2 liquid feeds and 2 sources of protein in starter on performance and blood metabolites in Holstein neonatal calves. J. Dairy Sci. 2014, 97, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camiloti, T.; Fregonesi, J.; Weary, D. Short communication: Effects of bedding quality. Am. Dairy Sci. Assoc 2012, 4, 3380–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKay, C.; Ellis, K.; Haskell, M.J.; Cousar, H.; Gladden, N. Detecting play behaviour in weaned dairy calves using accelerometer data. J. Dairy Res. 2024, 91, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesenti Rossi, G.; Dalla Costa, E.; Barbieri, S.; Minero, M.; Canali, E. A systematic review on the application of precision livestock farming technologies to detect lying, rest and sleep behavior in dairy calves. Front. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 1477731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webb, L.E.; Bokkers, E.A.; Engel, B.; Gerrits, W.J.; Berends, H.; van Reenen, C.G. Behaviour and welfare of veal calves fed different amounts of solid feed supplemented to a milk replacer ration adjusted for similar growth. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 2012, 136, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.; Warner, R.; Kertz, A. Effect of fiber level and physical form of starter on growth and development of dairy calves fed no forage. Prof. Anim. Sci. 2007, 23, 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).