Abstract

This work reports the synthesis and characterization of a new molecular hybrid 4, created by combining 1,4-naphthoquinone with the drug zidovudine (AZT) through an azide-alkyne cycloaddition reaction catalyzed by Cu1+. In vitro studies assessed the anti-trypanosomatid activity of hybrid 4, along with its precursors and synthetic intermediates (1, 2, and 3), against Trypanosoma cruzi (T. cruzi Tulahuen C2C4 LacZ), Trypanosoma brucei (T. b. brucei 427), and Leishmania infantum, as well as cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages and LLC-MK2 cells. The biological results confirm the molecular design, showing that the new hybrid is effective against both epimastigotes and amastigotes of T. cruzi (IC50 = 22.26 ± 5.78 μM and 143.10 ± 5.79 μM, respectively), with approximately 4.5-fold better capacity than AZT to inhibit the epimastigote form. Additionally, the hybrid was also active against bloodstream T. b. brucei (IC50 = 54.47 ± 6.70 μM), with approximately 2.2-fold better capacity than AZT to inhibit this parasite. It also shows low toxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages (CC50 > 200 μM) and LLC-MK2 cells (CC50 > 200 μM). For example, hybrid 4 exhibited approximately a 6.6-fold higher SI than 1,4-naphthoquinone 1 against T. cruzi amastigotes. In this context, the work contributes to the broader knowledge base guiding the design of hybrid molecules for antiparasitic chemotherapy. It provides a rational foundation for preparing subsequent, more potent analogues.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, and sleeping sickness are neglected tropical diseases that create significant social and public health challenges, affecting millions globally, especially in underdeveloped and developing countries. Protozoa from the Trypanosomatidae family cause these diseases [1,2,3]. The available treatments for these diseases are limited. Currently, therapeutic options are limited to a few compounds developed decades ago that have high toxicity profiles, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, low selectivity, and prolonged treatment durations. These factors lead to severe side effects and a high rate of patient discontinuation. Additionally, increasing parasite resistance reduces the effectiveness of current therapies. It is important to highlight that the trypanosomatids’ mechanism of entering “dormant” states may also negatively impact treatment, allowing the parasite to evade the host immune response and drug action, thereby contributing to treatment failures and high relapse rates. Consequently, there is an urgent need for new, safer, more effective, and affordable chemotherapeutic agents that can overcome these limitations [4,5,6].

Naphthoquinones are conjugated cyclic dienones belonging to a class of organic compounds characterized by a naphthalene ring in their structure [7]. They are widely found in nature and can be isolated from various sources, including plants, fungi, bacteria, and marine animals [8]. Additionally, naphthoquinones can be synthesized through multiple methods [9]. The literature reports diverse biological activities for this class of compounds, including antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antitumor, and cardioprotective effects [8,10,11]. Naphthoquinones with opposite carbonyl groups are known as para-quinones (1,4-diketone system) and are the most common [8]. Derivatives of the 1,4-naphthoquinone structure may serve as promising compounds with various pharmacological activities [12,13,14,15]. The high chemical reactivity of these molecules mainly arises from their ability to participate in redox reactions, produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), and form adducts with essential biomolecules such as proteins and genetic material [16,17,18].

3′-Azido-3′-deoxythymidine, also known as azidothymidine or zidovudine (AZT), was developed in the 1960s and recognized for its antiretroviral activity. AZT was initially intended as an anticancer agent; however, through a drug repurposing strategy in the late 1980s, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), where it acts as a chain terminator by interacting with the reverse transcriptase (RT) enzyme during viral replication [19]. A study by Nakajima-Shimada et al. (1996) [20] examined the effects of purine and pyrimidine analogs on the infection rate and growth of T. cruzi (Tulahuen) within mammalian host cells, including HeLa cells and Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts, using allopurinol as a positive control. AZT significantly inhibited the proliferation of T. cruzi amastigotes at concentrations of 0.5–1 μM. Additionally, the researchers noted that AZT’s inhibitory effect on parasite growth was not dose-dependent, particularly at higher concentrations of 10 and 50 μM [20]. In 1998, this research team evaluated a potential mechanism underlying AZT’s action on T. cruzi. Since HIV RT is a known target of AZT, they sought to identify the activity of this enzyme in T. cruzi epimastigotes. The results showed that AZT inhibited retroviral RT activity but did not affect T. cruzi RT, suggesting that AZT could target other enzymes, including a parasite DNA polymerase [21].

Drug repositioning, or drug repurposing, is a promising and attractive approach to identify new therapeutic uses for already approved, discontinued, or investigational drugs [22,23]. Publications using in silico approaches suggest drug repurposing as a good strategy to find new alternatives to treat Chagas disease [24,25] including the antiviral AZT [26]. Besides drug repositioning, molecular hybridization can also yield new therapeutic options. Molecular hybridization is a commonly used tool in medicinal chemistry. It combines two molecules (or parts of them) of therapeutic interest into a new chemical entity, known as a molecular hybrid. These hybrids can be created through ligation (using a linker or connector) or integration (fusion) of structures [27].

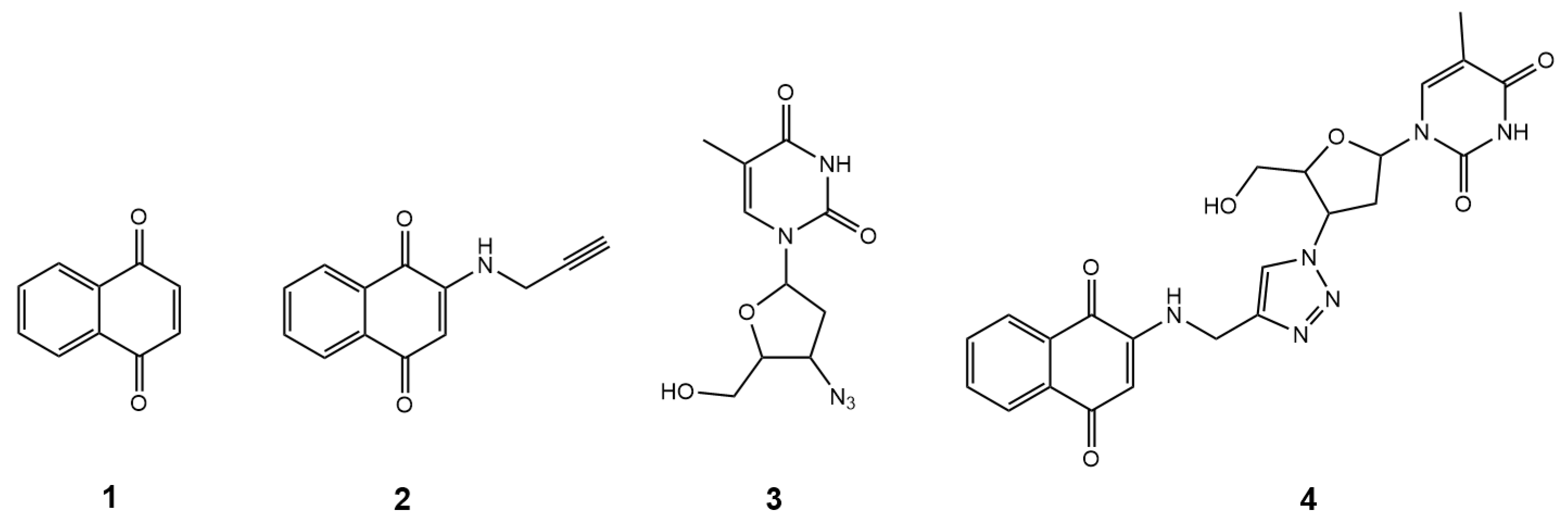

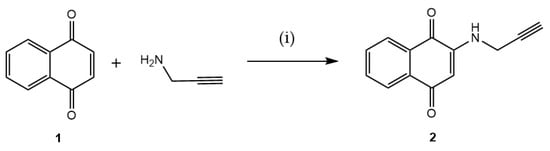

Thus, in the present study, using a molecular hybridization approach, AZT was integrated into the structure of 1,4-naphthoquinone, yielding the hybrid compound 1-(4-(4-(((1,4-dioxo-1,4-dihydronaphthalen-2-yl)amino)methyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-1-yl)-5-(hydroxymethyl)tetrahydrofuran-2-yl)-5-methylpyrimidine-2,4(1H,3H)-dione, with the simple name 1,4-naphthoquinone-AZT (hybrid 4, Figure 1). This design aims to enhance pharmacological properties and explore new therapeutic targets, particularly for novel drug candidates targeting neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). The pharmacophoric groups were linked via a rigid 1,2,3-triazole ring through a copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) reaction, a fast, efficient, and reliable method for synthesizing bioactive molecules [28]. Overall, this work presents the synthesis, characterization, and in vitro evaluation of the hybrid 1,4-naphthoquinone-AZT (hybrid 4, Figure 1), along with its intermediate (2, Figure 1) and precursors (1, Figure 1) and (3, Figure 1), focusing on their activity against three clinically significant trypanosomatids: anti-T. cruzi, anti-T. b. brucei, and anti-Leishmania activities, as well as cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages and LLC-MK2 cells.

Figure 1.

The structures of compounds 1–4.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.1.1. Equipment, Reagents, and Solvents

Reagents and chemicals were obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), Neon (Suzano, SP, Brazil), and Anidrol (Diadema, SP, Brazil). Reactions were monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) on 0.25 mm Merck (Darmstadt, Germany) silica gel plates (60F-254) and visualized under UV lamps (254 and 365 nm). Standard flash silica gel (60 mesh) from Sorbent Technologies (Norcross, GA, USA) was used for purification by open-column chromatography. The compounds’ melting points (m.p.) were measured using a Fisatom 430D apparatus (São Paulo, SP, Brazil) and are uncorrected. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra for 1H and 13C were recorded on a Bruker Ultrashield Plus spectrometer (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) operating at 500 MHz for 1H and 125 MHz for 13C at 25 °C. The analyses were performed in DMSO-d6, and tetramethylsilane (TMS) was added as an internal standard. Chemical shifts (δ) are expressed in parts per million (ppm), and coupling constants (J) are reported in Hertz (Hz). Signal multiplicities include singlet (s), doublet (d), double doublet (dd), triplet doublet (td), triplet (t), double triplet (dt), quartet (q), and multiplet (m). An ultrasonic bath (Unique, USC-1600, 40 kHz, Indaiatuba, São Paulo, Brazil) was used. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analyses were performed on a Shimadzu LC-MS-2020 system (Shimadzu Inc., Kyoto, Japan). Analytical parameters comprised: column—Kromasil C18, 150 mm × 4.6 mm × 5 µm (AkzoNobel, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); mobile phase—water with 0.1% formic acid (A), acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B); flow rate—1.0 mL/min with a linear gradient; injection volume—10 µL; detectors—PDA (200–400 nm), ESI+ (low resolution). High-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) was conducted using a Bruker COMPACT QTOF (Bruker-Daltonics, Bremen, Germany).

2.1.2. Chemical Synthesis

Preparation of 2-(Prop-2-yn-1-ylamino)naphthalene-1,4-dione (2)

In a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, 158 mg (1.0 mmol) of commercial 1,4-naphthoquinone 1 was dissolved in 2 mL of absolute ethanol (99.5%) at room temperature. The system was placed in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. Then, 83 mg of prop-2-yn-1-amine (1.5 mmol) were added to the mixture. The reaction was performed for 60 min in an ultrasonic bath and monitored by TLC using hexane/ethyl acetate (7:3) as the eluent. Afterward, a precipitate was collected by vacuum filtration and washed with ice-cold ethanol. Additionally, flash silica gel column chromatography (using hexane/ethyl acetate (7:3) as the eluent) afforded 127 mg of intermediate 2 (60% yield). The product was isolated as an orange solid and decomposed at 198 °C; Gholampour and colleagues (2019) report a melting point of 203–205 °C [29]. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra were consistent with the data reported in the literature [29,30]. HRMS (ESI+ m/z) calcd. for [C13H9NNaO2]+, 234.0531; found 234.0527. HPLC, gradient, ACN:H2O (60–95% ACN), 15 min, 0.1% formic acid; r.t. = 2.69 min, purity = 100%. Supplementary Materials Figures S1–S4.

Preparation of 1,4-Naphthoquinone-AZT Hybrid (4)

In a round-bottom flask equipped with a magnetic stir bar, 63.3 mg (0.3 mmol) of intermediate 2 and 80.1 mg (0.3 mmol) of AZT 3 were dissolved in 3.5 mL of ethanol. The mixture was stirred and heated to 40 °C. Simultaneously, 17.7 mg (0.088 mmol) of sodium ascorbate (C6H7NaO6) was dissolved in 750 µL of water in a 1.5 mL tube. In another tube, 15.0 mg (0.06 mmol) of copper sulfate pentahydrate (CuSO4·5H2O) was dissolved in 750 µL of water. The sodium ascorbate and copper sulfate solutions were added to the initial flask. After addition, the reaction mixture was stirred at 40 °C for 3 h, and the progress was monitored by TLC using a dichloromethane/methanol (95:5) solvent system. The hybrid 4 was purified on a flash silica gel column using the same solvent system as the TLC, with a concentration gradient from 0 to 5%. Ultimately, 79.9 mg (56%) of the 1,4-naphthoquinone-AZT hybrid 4 was obtained. The product appeared as an orange amorphous solid with a melting point of 136–137 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 11.37 (s, 1H), 8.25 (s, 1H), 8.02–7.96 (m, 2H), 7.93 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.83 (td, J = 7.6, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.80 (d, J = 1.3 Hz, 1H), 7.74 (td, J = 7.5, 1.3 Hz, 1H), 6.40 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H), 5.79 (s, 1H), 5.34 (dt, J = 8.5, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 5.30 (t, J = 5.2 Hz, 1H), 4.50 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 3H), 4.18 (q, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.68 (dt, J = 11.7, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.63–3.54 (m, 1H), 2.75–2.66 (m, 1H), 2.67–2.57 (m, 1H), 1.80 (d, J = 1.2 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 182.0, 181.9, 164.2, 150.9, 148.7, 143.8, 136.7, 135.3, 133.4, 132.7, 130.8, 126.3, 125.8, 123.3, 110.0, 100.9, 84.8, 84.2, 61.1, 59.6, 37.8, 37.5, 12.7. HRMS (ESI+ m/z) calcd. for [C23H22N6NaO6]+, 501.1499; found 501.1518. HPLC, gradient, ACN:H2O (50–95% ACN), 15 min, 0.1% formic acid, r.t. = 1.78 min, purity = 98.2%. Supplementary Materials Figures S5–S8.

2.2. Biological Assays

2.2.1. Cytotoxicity Assessment in RAW 264.7 Macrophages

The mouse mononuclear macrophage leukemia cell line RAW 264.7 (ATCC) is an adherent cell line derived from a mouse tumor induced by the Abelson murine leukemia virus, used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of compounds 1–4. The cells were cultured in complete Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and maintained in an incubator at 37 °C with controlled humidity and 5% CO2. The inoculum was prepared by treating the cell monolayer with an aqueous solution containing 0.25% w/v trypsin and 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) for 5 min. Passages were performed at a 1:6 inoculum volume ratio every 4 days. A suspension of 1 × 104 RAW 264.7 macrophages in DMEM with 5% FBS was added to a 96-well plate and incubated for 12 h. The cells were then washed with PBS to remove non-adherent cells. Cells were treated, in triplicate, with serial dilutions (200–1.56 µM) of compounds 1–4, previously solubilized in DMSO and diluted in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS. The maximum tested concentration was limited by the compounds’ solubility in the culture medium, while maintaining the final DMSO concentration at ≤0.2% (v/v) to avoid precipitation and interference with absorbance readings. DMEM containing 0.2% v/v DMSO served as the untreated control, and wells without cells served as blanks. After 48 or 72 h of treatment (depending on the type of experiment), the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. The culture medium was then replenished. Next, 10 µL of 3.0 mM MTT-(3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) salt—was added, and the plate was incubated again for 1.5 h at 37 °C. The supernatant was removed, and the MTT formazan crystals were solubilized by adding 100 µL of DMSO per well. The plate was shaken for 30 min to ensure complete solubilization of the sample. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.2.2. Cytotoxicity Assessment in LLC-MK2 Cells

The cytotoxicity of compounds 1–4 was also tested in mammalian cells, i.e., Rhesus monkey kidney epithelial cells (LLC-MK2, ATCC), which were grown in DMEM with 5% FBS in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C, with passages every 4–5 days. The cells were detached from the monolayer using a solution containing 0.25% w/v trypsin and 0.04% EDTA. A 1 × 104 LLC-MK2 cell suspension in DMEM with 2% FBS was added to a 96-well plate and incubated for 20 h. After incubation, the cells were washed with PBS to remove non-adherent cells. They were then treated with serial dilutions (200–12.8 µM) of compounds 1–4 in triplicate, pre-diluted in DMEM with 2% FBS. DMEM containing 0.2% v/v DMSO served as the untreated control, and wells without cells served as blanks. After 120 h of treatment, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. The culture medium was then replaced. 20 µL of 3.0 mM MTT saline solution was added, and the plates were incubated for an additional 1.5 h at 37 °C. Subsequently, the supernatant was removed, and MTT formazan crystals were solubilized by adding 100 µL per well of a mixture of isopropanol, acetate buffer, and Triton X-100. The plates were shaken for 30 min to dissolve the formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.2.3. Evaluation of Trypanocidal Activity Against T. cruzi Epimastigotes

T. cruzi epimastigotes of the Tulahuen C2C4-LacZ strain were cultured in Liver Infusion Tryptose (LIT) medium, supplemented with hemin (25 mg/L) and 10% FBS, and incubated at 28 °C, with successive passages every 6–7 days. A suspension of 1 × 105 epimastigote forms in LIT medium with 10% FBS was added to a 96-well plate. The parasites were then treated, in triplicate, with serial dilutions (200–3.2 µM) of compounds 1–4, pre-diluted in LIT with 10% FBS. As a control, LIT medium with 0.2% v/v DMSO was used, and wells without parasites served as blanks. Benznidazole was used as a reference drug. After 120 h of treatment in a BOD incubator at 28 °C, 30 µL of a 0.5 mM chlorophenol red-β-D-galactopyranoside (CPRG) substrate in PBS with 0.9% v/v Igepal CA-630 was added. After 1.5 h of incubation, absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.2.4. Evaluation of Trypanocidal Activity Against T. cruzi Amastigotes

The anti-T. cruzi activity was also tested against amastigotes of the Tulahuen C2C4-LacZ strain. Both amastigote and trypomastigote forms were maintained through successive reinfections in a monolayer of LLC-MK2 cells in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Trypomastigotes were collected from the culture supernatant between days 5 and 10 after infection and separated from non-adherent cells by differential centrifugation. In a transparent 96-well plate, LLC-MK2 cells (1 × 104 cells per well) were seeded in DMEM with 2% FBS. After 3 h of incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for cell attachment, wells were washed with PBS to remove non-adherent cells, then infected with T. cruzi trypomastigotes (1.5 × 105 parasites per well) of the Tulahuen C2C4-LacZ strain. After 20 h of incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for infection, the wells were washed three times with PBS to remove non-internalized parasites. Cells were then treated in triplicate with serial dilutions (from 200 to 3.2 µM) of compounds 1–4, pre-diluted in DMEM with 2% FBS. Untreated controls (DMEM with 0.2% v/v DMSO) and blanks (lacking cells or parasites) were also included. Benznidazole, in serial dilutions, served as the positive control. After 120 h of incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2, 30 µL of a 0.5 mM CPRG substrate in PBS containing 0.9% v/v Igepal CA-630 was added, followed by an additional 1.5 h of incubation under the same conditions. Subsequently, absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.2.5. Evaluation of Leishmanicidal Activity Against Promastigotes

For activity assays against Leishmania, we used promastigotes of the Leishmania infantum (strain MCAN/BR/2014/21BAÇO), maintained in Schneider’s insect medium supplemented with 20% FBS and penicillin (100 U/mL) at 26 °C in a BOD incubator. Only cultures with up to 10 in vitro passages were used to ensure the promastigotes’ infectivity. A 1 × 105 promastigote suspension in Schneider’s medium with 20% FBS was added to a 96-well plate. Then, the parasites were treated with serial dilutions (200–1.56 µM) of compounds 1–4 in Schneider’s medium with 20% FBS, in triplicate. Schneider’s medium containing 1% v/v DMSO served as the untreated control, and wells without added parasites served as blanks. Miltefosine served as the reference drug. After 72 h of treatment in a BOD incubator at 26 °C, parasite viability was assessed using a colorimetric MTT assay. 10 µL of sterile MTT solution (5 mg/mL in PBS) was added to all wells. The plate was incubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 3 h. Subsequently, 100 μL of DMSO was added, and the plate was shaken for 30 min to solubilize the MTT formazan crystals. Absorbance was then measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.2.6. Evaluation of Trypanocidal Activity Against T. brucei Bloodstream

Trypanosoma brucei (T. brucei) subsp. brucei, strain Lister 427 VSG 221 (ATCC) trypomastigotes were cultured in HMI-9 medium with 10% FBS and maintained in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C, with passages every 4–5 days. A suspension of 1 × 104 trypomastigotes in HMI-9 with 10% FBS was added to a 96-well plate. The parasites were then treated with serial dilutions (120–7.68 µM) of compounds 1–4, prediluted in HMI-9 with 10% FBS, in triplicate. HMI-9 medium containing 0.2% v/v DMSO served as the untreated control, and wells without parasites were used as blanks. Fexinidazole was used as the reference drug. After 48 h of treatment, 20 µL of 3.0 mM MTT saline solution was added, and the plate was incubated for an additional 1.5 h at 37 °C. MTT formazan crystals were solubilized by adding 100 µL per well of a mixture containing isopropanol, acetate buffer, and Triton X-100. The plate was then placed on a shaker for 30 min to dissolve the MTT formazan crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a plate reader.

2.3. Statistical Analysis of In Vitro Activity Data

The absorbance values obtained from the in vitro experiments were subtracted from the mean of the blank control and converted into percentage viability values relative to the mean of the untreated control triplicate, using Equation (1):

The experimental data were entered into GraphPad Prism 9.0 for statistical analysis, including the calculation of the 50% growth-inhibitory concentration (IC50) and the 50% cytotoxic concentration (CC50). The software’s default nonlinear regression model, with a variable slope, was used for each inhibitor concentration versus normalized response.

2.4. ADME and Drug-Likeness and Target Predictions

The ADME, some physicochemical properties, drug-likeness, and target predictions were estimated for compounds 1–4 with the free web server SwissADME and SwissTargetPrediction [31,32]. The physicochemical properties of the drugs benznidazole, miltefosine, and fexinidazole were also estimated with the same web server.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemistry

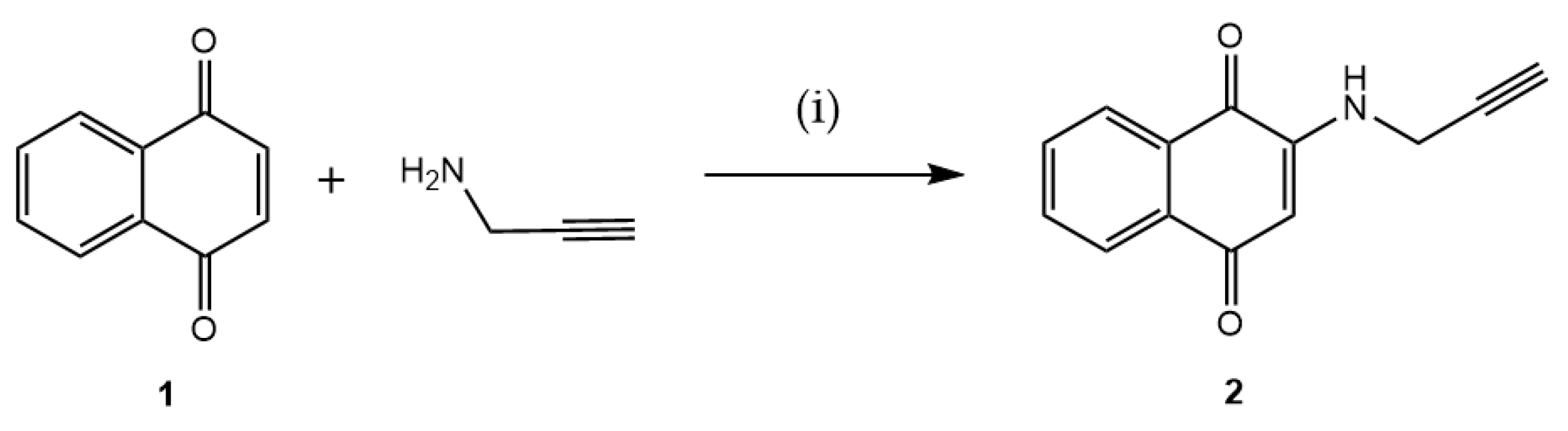

To create a point in the 1,4-naphthoquinone structure that can anchor to AZT, the quinone moiety was planned to be functionalized with an alkyne. Thus, the terminal alkyne was initially incorporated into the 1,4-naphthoquinone framework 1, yielding the intermediate 2-(prop-2-yn-1-ylamino)naphthalene-1,4-dione (2). This intermediate is appropriate for the CuAAC, achieved by reacting 1 with prop-2-yn-1-amine. This primary amine is added via a Michael-type conjugate addition, as illustrated in Figure 2. The reaction produced 2 in a 60% yield.

Figure 2.

Preparation of intermediate 2 via a 1,4-Michael-type addition reaction. Reaction conditions: (i) EtOH, ultrasound, 1 h, rt (60%).

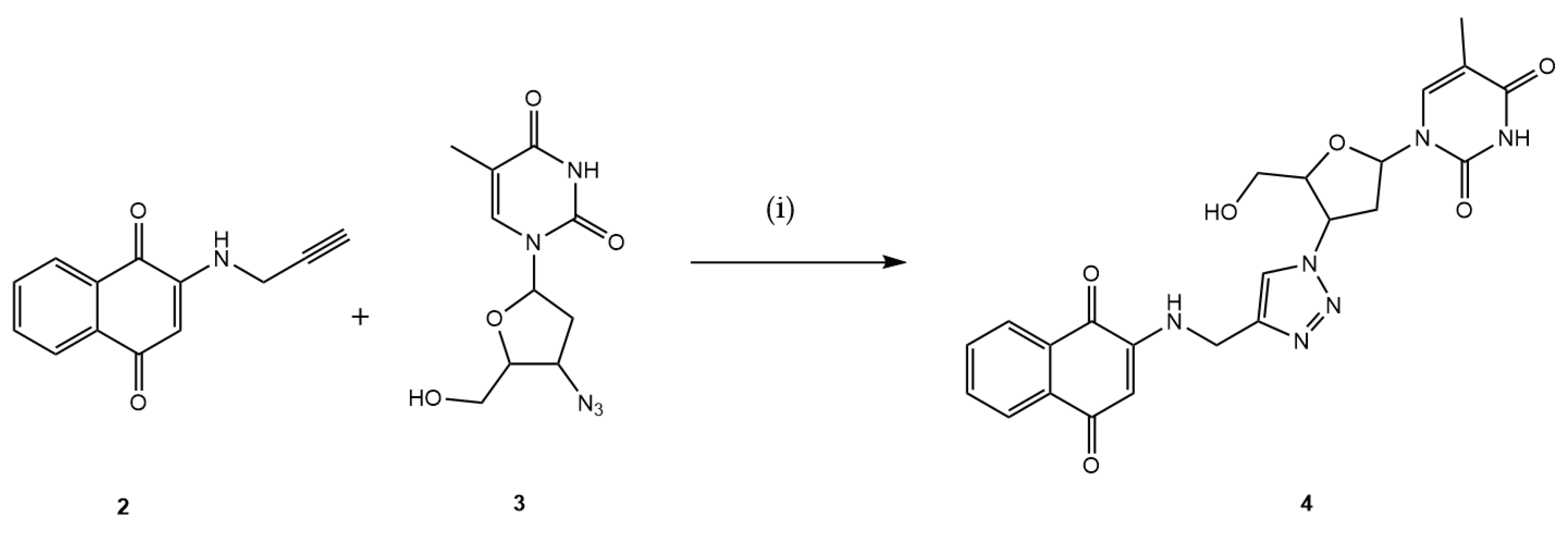

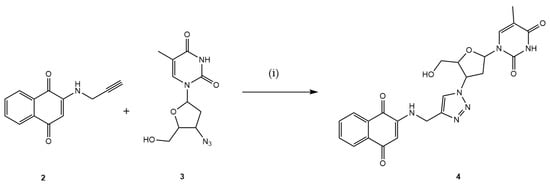

In the subsequent step, the intermediate 2 reacted with AZT 3, which contains an azide functional group within its structure, via the CuAAC reaction utilizing in situ generated Cu1+, by the sodium ascorbate, resulting in the formation of the desired hybrid 4 with a yield of 56%, as illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Preparation of the new 1,4-naphthoquinone-AZT hybrid 4. Reaction conditions: (i) MeOH:H2O (7:3), CuSO4·5H2O, C6H7NaO6, 3 h, 40 °C (56%).

The 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinones, by generating reactive oxygen species and inducing cell death (apoptosis), present a scaffold of great interest in medicinal chemistry. They are studied for their potential as anticancer, antimicrobial, and antiparasitic agents, among others, and as versatile precursors for the synthesis of new compounds with diverse biological activities [33,34,35,36]. When functionalized with a terminal alkyne, 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinones can act as reagents in CuAAC reactions. In this type of reaction, azides and alkynes are joined via a rigid, stable 1,2,3-triazole ring. These highly efficient reactions are often employed to incorporate pharmacophoric groups from different molecules in the search for new drug candidates [37,38,39]. In recent years, several studies have reported the antiparasitic activities of compounds derived from 2-amino-1,4-naphthoquinones containing a 1,2,3-triazole moiety. Costa Souza and collaborators (2023) evaluated these compounds in vitro for antimalarial activity against the chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum W2 strain and in vivo using the murine Plasmodium berghei ANKA strain [40]. Another notable study reported the synthesis and anti-T. cruzi activity of 1,2,3-triazoles incorporating the 1,4-naphthoquinone moiety. Some compounds from this work were more potent than benznidazole, the standard drug used to treat chagasic patients [41].

3.2. Biological Assayss

The trypanocidal evaluation of the planned hybrid 4 against both epimastigotes and amastigotes of T. cruzi (Tulahuen C2C4 LacZ) and bloodstream T. b. brucei revealed IC50 values of 22.26 ± 5.78, 143.10 ± 5.79, and 54.47 ± 6.70 µM, respectively (Table 1 and Table 2). The proposed hybrid exhibited approximately 2.4-fold higher activity against T. cruzi epimastigotes than against bloodstream forms of T. b. brucei. Our study determined that the IC50 value for AZT against T. cruzi amastigotes was 33.31 ± 0.81 µM (Table 1). This data significantly diverges from previously documented values in the literature, which range from 0.5 to 1.0 µM [20]. This discrepancy may stem from methodological differences across studies, such as variations in experimental protocols. Furthermore, factors such as sample purity, the protozoan strain, the host cell type used for in vitro infection, and assay conditions can substantially influence IC50 measurements. Consequently, we emphasize standardizing methodologies to enable accurate comparisons and the validation of in vitro IC50 data.

Table 1.

Activities of compounds 1–4 against T. cruzi (Tulahuen C2C4-LacZ) epimastigotes and amastigotes, cytotoxicity in LLC-MK2 cells, and selectivity index.

Table 2.

Activities of compounds 1–4 against L. infantum promastigotes and T. b. brucei trypomastigotes, cytotoxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages, and selectivity index.

An additional notable observation is that hybrid 4 showed inactivity against L. infantum promastigotes at the concentrations evaluated (IC50 > 200 µM), as shown in Table 2.

The results shown here demonstrate that hybrid 4 is less active than its precursor 1 and the control/reference drugs (benznidazole and fexinidazole). In the present study, the maximum concentration evaluated for the tested compounds was defined by their physicochemical solubility limit in the culture medium, while maintaining a maximum final DMSO concentration of 0.2% (v/v), a value widely accepted as non-cytotoxic for the cell lines employed. Concentrations above this limit resulted in incomplete solubilization and visible precipitation of the compounds, which could generate experimental artifacts, reduce effective bioavailability, and directly interfere with absorbance measurements, thereby compromising the reliability of the colorimetric assays used, such as the MTT assay. In this context, for hybrid 4, as well as for AZT (3), CC50 values were not reached at the maximum concentrations tested in RAW 264.7 macrophages (CC50 > 200 µM) and LLC-MK2 cells (CC50 > 200 µM), indicating low cytotoxicity. According to widely adopted practice in the literature, when CC50 is not experimentally achieved, the value is reported as greater than the highest tested concentration (CC50 > maximum concentration) or as lower than the lowest tested concentration (CC50 < minimum concentration), and consequently the selectivity index (SI) should be expressed as SI> the calculated value or SI< the calculated value [42,43,44]. The diminished antiparasitic efficacy of hybrid 4 compared with its two precursors, as well as with the reference drugs benznidazole and fexinidazole, may be attributable to a combination of structural and physicochemical factors that could be addressed through subsequent structural enhancement efforts. Although 1,4-naphthoquinone 1 demonstrated better antiparasitic activity, its cytotoxic action makes it unviable as a therapeutic agent in RAW 264.7 macrophages (CC50 < 1.56 μM—72 h) and LLC-MK2 cells (CC50 = 1.48 ± 0.16 μM). AZT 3 did not exhibit significant cytotoxic activity in RAW 264.7 macrophages (CC50 > 200 μM) and in LLC-MK2 cells (CC50 > 200 μM) in our study. However, AZT was inactive against most tested trypanosomatids, including T. cruzi epimastigotes, T. b. brucei trypomastigotes, and L. infantum promastigotes. It showed only moderate activity against T. cruzi amastigotes (IC50 = 33.31 ± 0.81 μM).

Since AZT is a prodrug widely used in anti-HIV therapy, it is expected that host cell enzymes, such as thymidine kinase, thymidylate kinase, and nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDPK), convert AZT into the triphosphate form, which acts as a chain terminator [45]. Interestingly, T. cruzi has multiple NDPK isoforms (at least 4 predicted), suggesting diverse roles across the parasite’s life cycle [46]. Additionally, T. brucei has one gene for NDPK (expressed in both bloodstream and procyclic forms), and the resulting protein is highly conserved across species [47], while Leishmania species, including L. infantum, are generally understood to possess a single main NDPK enzyme, referred to as nucleoside diphosphate kinase b (NDKb) [48]. According to the obtained IC50 values for AZT (Table 2), this prodrug is less activated by NDKb than NDPK in L. infantum and T. brucei, respectively. On the other hand, for T. cruzi, different levels of NDPK isoforms were reported in epimastigote and amastigote forms, e.g., NDPK1 isoform is primarily located in the cytosol of T. cruzi epimastigotes, and NDPK3 was detected at lower levels in amastigotes [49], supporting the differences in the IC50 values of AZT for T. cruzi epimastigotes and amastigotes (Table 1).

Unlike AZT, it was reported that the 1,4-naphthoquinones inhibition mechanisms in parasites do not involve molecule phosphorylation, being related to significant structural alterations to mitochondria, damaging the parasite’s DNA and proteins, which leads to cell death through necrosis or apoptosis [50,51], supporting the obtained experimental differences in the IC50 values of the 1,4-naphthoquinones 1 and 2 compared with AZT 3 and the hybrid 4 (Table 1 and Table 2). However, recently, parasite protein kinase has also been reported as a potential molecular target for 1,4-naphthoquinones [52,53] highlighting their multi-target mechanism, agreeing with the obtained inhibitory capacity of 1 and 2 to all assayed parasites (Table 1 and Table 2).

To understand the theoretical capacity of compounds 1–4 to interact with different cellular targets depending on the nature of the assayed compounds, a preliminary screening on feasible theoretical human-centric targets, a maximum of fifteen, was estimated with the web server SwissTargetPrediction (https://www.swisstargetprediction.ch/, accessed on 3 October 2025) [32] on the similarity principle, through reverse screening of the molecular structure of small compounds. The main predicted feasible targets for compounds 1–4 are summarized in Figure S9 in the Supplementary Materials, highlighting as an example, differences on human kinase, one of the most probable targets for all compounds in different percentages, i.e., the presence of prop-2-yn-1-amine moiety incorporated into the 1,4-naphthoquinone framework 1 decreased the probability of interaction with kinases from 20.0% to 6.7%, also changing the percentage to other targets. On the other hand, the hybrid 4, compared with AZT 3, improved the probability of interaction with kinases from 20.0% to 53.3%. Despite the predicted targets being based on human-centric and not designed for T. cruzi, T. brucei, or Leishmania proteosomes, the theoretical trend demonstrated the capacity of compounds 1–4 to interact with kinases. Future enzymatic screening based on target assays is necessary to better understand the differences in the chemical structures of compounds 1–4 with respect to parasite kinases, including the different NDPK isoforms of T. cruzi, as well as other targets.

3.3. In Silico Drug-Likeness Predictions

Pharmacokinetic prediction (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion—ADME), physicochemical properties (e.g., lipophilicity, solubility, and molecular weight), and structural features (e.g., Lipinski’s rule of five and Veber’s criteria) are among the main components of drug-likeness prediction. In this sense, in silico calculations for the small organic compounds 1–4 were performed using the free web server SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php, accessed on 3 October 2025) [31]. The reference drugs for T. cruzi, L. infantum, and T. b. brucei, i.e., benznidazole, miltefosine, and fexinidazole, respectively, were also considered for physicochemical predictions.

Figure S10 in the Supplementary Materials depicts the brain or intestinal estimated permeation model (BOILED-egg) for compounds 1–4, indicating that the 1,4-naphthoquinones 1 and 2 had the highest lipophilicity (log Po/w, Table 3) and the lowest topological polar surface area (TPSA, Table 3), indicating high probability to blood–brain barrier permeation with high gastrointestinal absorption profile; however, for AZT 3 and its hybrid 4, mainly due to the presence of high number of electronegative atoms composing the heterocyclic moieties there was a decreased in the log Po/w value, increasing the TPSA value (Table 3), which suggested that the commercial drug and the hybrid might have passive gastrointestinal absorption and poor absorption, respectively. Probably, these differences impacted the uptake of compounds 3 and 4 into the intracellular medium, which was reflected by their experimental highest IC50 values in most cases, e.g., from 7.02 ± 0.72 to 143.10 ± 5.79 µM, for compounds 1 and 4, respectively, against amastigotes of T. cruzi (Table 1). The reference drugs had higher lipophilicity values than compounds 3 and 4 (Table 3), which positively impacted their uptake by the parasites and contributed to the best experimental IC50 values for benznidazole and fexinidazole (Table 1 and Table 2). Additionally, compounds 1–4 were considered non-substrates of P-glycoprotein 1 (PGP-), thereby affecting their residence time in the cellular medium, which was one of the reasons that, experimentally, all compounds had some influence on the parasites’ replication and certain cytotoxicity (Table 1 and Table 2) [54]. The reference drugs benznidazole and fexinidazole are also non-substrates of P-glycoprotein1; however, miltefosine was identified as a substrate of P-glycoprotein1 (Figure S10 in the Supplementary Materials), being one of the reasons that miltefosine did not achieve the best IC50 value compared with other evaluated compounds to the same parasite (Table 2), even having a high theoretical logPo/w value (Table 3).

Table 3.

Selected physicochemical, drug-likeness, and pharmacokinetic properties predicted for the compounds 1–4 by the free web server SwissADME.

All compounds were predicted to be drug-like, as reinforced by the non-violation or only one violation of Lipinski’s rule of five for compound 4 (Table 3). In contrast, in Veber’s criteria, compound 4 and miltefosine were not predicted as drug-like (Table 3). This trend was reinforced by the computed bioavailability radar depicted in Figure S11 in the Supplementary Materials. The in silico predictions also suggested that the 1,4-naphthoquinones 1 and 2 might inhibit some isoforms of cytochrome (CYP, Table 3), i.e., CYP1A2 for compound 1, while CYP1A2 and CYP2C19 for compound 2, resulting in low metabolization that might be reflected in their experimental CC50 values (Table 1 and Table 2), which indicated compounds 1 and 2 more cytotoxic than compounds 3 and 4—it can indirectly lead to toxicity by altering the metabolism of other intracellular compounds [55]. The commercial drug benznidazole was identified as a non-inhibitor of CYP (Table 3), which might reflect the high experimental CC50 value (Table 1).

4. Conclusions

The synthetic methodology described is highly efficient, enabling the production of both intermediate 2 and hybrid 4 in satisfactory yields and high purity. The results validate the molecular design, yielding hybrid 4 with toxic activity against T. cruzi epimastigotes and amastigotes, as well as T. brucei trypomastigotes. The inactivity of hybrid 4 against L. infantum promastigotes suggests that its mechanism of action may involve inhibition of a Trypanosoma-specific enzyme, such as various forms of kinases, that is absent in Leishmania. The new hybrid 4 showed low toxicity in RAW 264.7 macrophages and LLC-MK2 cells, with a favorable drug-likeness prediction (Lipinski’s rule of five).

Several clear optimization pathways can be envisioned based on our current results and well-established principles in medicinal chemistry, including the rational optimization of the linker between the two molecular components (AZT and 1,4-naphthoquinone) by modulating its length, flexibility, and polarity to improve target engagement and intracellular accessibility; fine-tuning the electronic and steric properties of each pharmacophoric moiety to enhance binding affinity for parasite-specific targets; improving key physicochemical parameters, such as lipophilicity and solubility, to favor cellular uptake and accumulation within relevant intracellular compartments; and exploring alternative substitution patterns or prodrug strategies to overcome potential limitations related to membrane permeability or metabolic stability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/chemistry8020015/s1, Figure S1: 1H-NMR (500 MHz) spectrum of 2 in DMSO-d6; Figure S2: 13C-NMR (125 MHz) DEPT-135 spectrum of 2 in DMSO-d6; Figure S3: HPLC Chromatogram of 2; Figure S4: HRMS-TOF (MS+) of 2; Figure S5: 1H-NMR (500 MHz) spectrum of 4 in DMSO-d6; Figure S6: 13C-NMR (125 MHz) DEPT-135 spectrum of 4 in DMSO-d6; Figure S7: HPLC Chromatogram of 4; Figure S8: HRMS-TOF (MS+) of 4; Figure S9: Predicted the feasible fifteen main targets for the compounds (A) 1, (B) 2, (C) 3, and (D) 4 calculated with the free webserver SwissTargetPrediction (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php, accessed on 3 October 2025); Figure S10: The predicted BOILED-Egg graphic for compounds 1–4, benznidazole, miltefosine, and fexinidazole, calculated with the free webserver SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php, accessed on 3 October 2025). The HIA, BBB, PGP+, and PGP- are passive gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeation, P-glycoprotein1 substrate, and P-glycoprotein1 non-substrate, respectively. WLOGP and TPSA are indicators of lipophilicity and apparent polarity, respectively. Figure S11: Computed bioavailability radar for the compounds (A) 1, (B) 2, (C) 3, (D) 4, (E) benznidazole, (F) miltefosine, and (G) fexinidazole, calculated with the free webserver SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php, accessed on 3 October 2025). LIPO, SIZE, POLAR, INSOLU, INSATU, and FLEX mean lipophilicity, molecular weight, topological polar surface area (TPSA), solubility parameter (log S), unsaturated, and flexibility, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.d.S.D.S. and M.E.F.d.L.; methodology, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V., T.R.R., J.V.d.C.S., H.P.-S., F.d.O.C., O.A.C., D.D.-R. and M.E.F.d.L.; software, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V. and O.A.C.; validation, T.d.S.D.S., M.E.F.d.L., H.P.-S., F.d.O.C. and D.D.-R.; formal analysis, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V., T.R.R., J.V.d.C.S., H.P.-S., F.d.O.C., C.G.F.-d.-L., O.A.C., D.D.-R. and M.E.F.d.L.; investigation, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V., T.R.R., J.V.d.C.S., H.P.-S., C.G.F.-d.-L., F.d.O.C., O.A.C., D.D.-R. and M.E.F.d.L.; resources, M.E.F.d.L., C.G.F.-d.-L., D.D.-R. and F.d.O.C.; data curation, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V., H.P.-S., O.A.C. and M.E.F.d.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.d.S.D.S., H.P.-S., O.A.C. and M.E.F.d.L.; writing—review and editing, T.d.S.D.S., A.S.M.M.V., T.R.R., J.V.d.C.S., H.P.-S., F.d.O.C., C.G.F.-d.-L., O.A.C., D.D.-R. and M.E.F.d.L.; visualization, T.d.S.D.S. and O.A.C.; supervision, M.E.F.d.L. and D.D.-R.; project administration, M.E.F.d.L.; funding acquisition, M.E.F.d.L. and D.D.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the funding agencies CNPq, CAPES (Finance Code 001), and FAPERJ (E-26/10.001699/2019 and E-26/210.074/2022) for their financial support, which made this work possible. The Coimbra Chemistry Centre—Institute of Molecular Sciences (CQC-IMS) is supported by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), a Portuguese Agency for Scientific Research. FCT funds CQC through projects UID/PRR/00313/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/00313/2025) (accessed on 3 October 2025) and UID/00313/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/00313/2025) (accessed on 3 October 2025) and IMS through special complementary funds provided by FCT (project LA/P/0056/2020, https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0056/2020 accessed on 3 October 2025). T.d.S.D.S. and A.S.M.M.V. thank CAPES for fellowships. O.A.C. acknowledges the Postgraduate Program in Cellular and Molecular Biology at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) and CAPES for the PIPD grant (process SCBA 88887.082745/2024-00, subproject 31010016).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the Multiuser Analytical Center at IQ-UFRRJ for characterizing and analyzing the intermediates and final product obtained in this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mitra, A.K.; Mawson, A.R. Neglected Tropical Diseases: Epidemiology and Global Burden. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2017, 2, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rijo-Ferreira, F.; Takahashi, J.S. Sleeping Sickness: A Tale of Two Clocks. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 525097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Doenças Tropicais Negligenciadas—GLOBAL. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Barrett, M.P.; Kyle, D.E.; Sibley, L.D.; Radke, J.B.; Tarleton, R.L. Protozoan Persister-like Cells and Drug Treatment Failure. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rycker, M.; Wyllie, S.; Horn, D.; Read, K.D.; Gilbert, I.H. Anti-Trypanosomatid Drug Discovery: Progress and Challenges. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiroga, C.; Incerti, M.; Benítez, D.; Luzardo, M.; Manta, E.; Leyva, A.; Paulino, M.; Comini, M.A.; Medeiros, A. Restyling an Old Scaffold: Ebsulfur Analogs with Improved Activity and Selectivity against the Infective Stage of Trypanosomes. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 292, 117675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sousa, E.T.; Lopes, W.A.; de Andrade, J.B. Fontes, Formação, Reatividade e Determinação de Quinonas na Atmosfera. Quim. Nova 2016, 39, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Liang, X.; He, C.; Yin, L.; Xu, F.; Li, H.; Tang, H.; Lv, C. Structural and Pharmacological Diversity of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Glycosides in Recent 20 Years. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 138, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loredo-Carrillo, S.E.; Leyva, E.; López-López, L.I.; Navarro-Tovar, G.; de Loera, D.; Vega-Rodríguez, S. Description of Some Methodologies for the Synthesis of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives and Examples of Their Biological Activity: A Review. Curr. Org. Chem. 2024, 28, 1118–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Liu, H.; Meng, W.; Sun, J. Analysis of Action of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Scaffold-Derived Compounds against Acute Myeloid Leukemia Based on Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulation. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 21043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paengsri, W.; Promsawan, N.; Baramee, A. Synthesis and Evaluation of 2-Hydroxy-1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives as Potent Antimalarial Agents. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2021, 69, 253–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminin, D.; Polonik, S. 1,4-Naphthoquinones: Some Biological Properties and Application. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2020, 68, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Khan, M.I.H.; Estep, A.S.; Cantrell, C.L.; Le, H.V. Chemical Structure-Biological Activity of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Analogs as Potential Aedes Aegypti Larvicides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 2881–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Shen, Z.; Xiang, S.; Sun, Y.; Cui, J.; Jia, J. Evaluation of 1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives as Antibacterial Agents: Activity and Mechanistic Studies. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2023, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, Y.H.; Piao, X.J.; Shen, G.N.; Meng, L.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.R.; Li, J.Q.; Wang, H.; Xu, W.T.; et al. Novel 1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives Induce Reactive Oxygen Species-Mediated Apoptosis in Liver Cancer Cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2019, 19, 1654–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, M.N.; Ferreira, V.F.; De Souza, M.C.B.V. Um Panorama Atual da Química e da Farmacologia de Naftoquinonas, com Ênfase na Beta-Lapachona e Derivados. Química Nova 2003, 26, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Islam, M.R.; Akash, S.; Shohag, S.; Ahmed, L.; Supti, F.A.; Rauf, A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Al Abdulmonem, W.; Khalil, A.A.; et al. Naphthoquinones and Derivatives as Potential Anticancer Agents: An Updated Review. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2022, 368, 110198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Lago, A.F.V.; Valle, C.d.A.C.; Rolim, H.D.d.S.L.; do Lago, L.C.; Firmo, W.d.C.A.; Silva, M.d.A.; Coêlho, M.L.; Sá, C.M.A. Atividade biológica das Naftoquinonas e Quinonas da espécie de Bignoniaceae Handroanthus Serratifolius. Obs. Econ. Latinoam. 2024, 22, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianco, M.d.C.A.D.; Inacio Leite, D.; Silva Castelo Branco, F.; Boechat, N.; Uliassi, E.; Bolognesi, M.L.; Bastos, M.M. The Use of Zidovudine Pharmacophore in Multi-Target-Directed Ligands for AIDS Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima-Shimada, J.; Hirota, Y.; Aoki, T. Inhibition of Trypanosoma cruzi Growth in Mammalian Cells by Purine and Pyrimidine Analogs. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1996, 40, 2455–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima-Shimada, J.; Aoki, T. Inhibition by 3′-Azido-3′-Deoxythymidine (AZT) of Trypanosoma cruzi Growth in Mammalian Cells and a Possible Mechanism of Action. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998, 431, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburn, T.T.; Thor, K.B. Drug Repositioning: Identifying and Developing New Uses for Existing Drugs. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckle, D.R.; Erhardt, P.W.; Ganellin, C.R.; Kobayashi, T.; Perun, T.J.; Proudfoot, J.; Senn-Bilfinger, J. Glossary of Terms Used in Medicinal Chemistry. Part II (IUPAC Recommendations 2013). Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1725–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim Haupt, V.; Aguilar Uvalle, J.E.; Salentin, S.; Daminelli, S.; Leonhardt, F.; Konc, J.; Schroeder, M. Computational Drug Repositioning by Target Hopping: A Use Case in Chagas Disease. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2016, 22, 3124–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juárez-Saldivar, A.; Schroeder, M.; Salentin, S.; Joachim Haupt, V.; Saavedra, E.; Vázquez, C.; Reyes-Espinosa, F.; Herrera-Mayorga, V.; Villalobos-Rocha, J.C.; García-Pérez, C.A.; et al. Computational Drug Repositioning for Chagas Disease Using Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adasme, M.F.; Bolz, S.N.; Adelmann, L.; Salentin, S.; Haupt, V.J.; Moreno-Rodríguez, A.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Castillo-Campos, V.; Yepez-Mulia, L.; De Fuentes-Vicente, J.A.; et al. Repositioned Drugs for Chagas Disease Unveiled via Structure-Based Drug Repositioning. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivasiv, V.; Albertini, C.; Gonçalves, A.E.; Rossi, M.; Bolognesi, M.L. Molecular Hybridization as a Tool for Designing Multitarget Drug Candidates for Complex Diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 1694–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelozo, M.F.; Lima, G.F.S.; Cordeiro, C.F.; Silva, L.S.; Caldas, I.S.; Carvalho, D.T.; Lavorato, S.N.; Hawkes, J.A.; Franco, L.L. Synthesis of New Hybrid Derivatives from Metronidazole and Eugenol Analogues as Trypanocidal Agents. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 24, 421–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholampour, M.; Ranjbar, S.; Edraki, N.; Mohabbati, M.; Firuzi, O.; Khoshneviszadeh, M. Click Chemistry-Assisted Synthesis of Novel Aminonaphthoquinone-1,2,3-Triazole Hybrids and Investigation of Their Cytotoxicity and Cancer Cell Cycle Alterations. Bioorganic Chem. 2019, 88, 102967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezeiova, E.; Janockova, J.; Andrys, R.; Soukup, O.; Kobrlova, T.; Muckova, L.; Pejchal, J.; Simunkova, M.; Handl, J.; Micankova, P.; et al. 2-Propargylamino-Naphthoquinone Derivatives as Multipotent Agents for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 211, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: Updated Data and New Features for Efficient Prediction of Protein Targets of Small Molecules. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W357–W3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, C.C.; Chaves, O.A.; Paiva, R.O.; da Costa, G.L.; Carlos Netto-Ferreira, J.; Echevarria, A. Antibacterial Activity of 2-Amino-1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacterial Strains and Their Interaction with Human Serum Albumin. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 1838, 31, 1838–1851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.Z.; Liang, Q.L.; Jing, X.T.; Wang, K.; Zhang, H.Y.; Wang, H.S.; Ma, X.L.; Wei, J.H.; Zhang, Y. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Novel 2-Amino-1,4-Naphthoquinone Amide-Oxime Derivatives as Potent IDO1/STAT3 Dual Inhibitors with Prospective Antitumor Effects. Molecules 2023, 28, 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razaque, R.; Raza, A.R.; Irshad, M.; Rubab, S.L.; Batool, S.; Nisar, B.; Akram, Z.; Akhtar, M.T.; Qadir, R.; Siddique, A.B.; et al. Synthesis and Evaluation of 2-Phenylamino-1,4-Naphthoquinones Derivatives as Potential Hypoglycaemic Agents. Braz. J. Biol. 2024, 84, e254234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayahi, M.H.; Hassani, B.; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani, M.; Dastyafteh, N.; Gohari, M.R.; Tehrani, M.M.; Larijani, B.; Mahdavi, M.; Firuzi, O. Design, Synthesis, and Cytotoxic Activity of 2-Amino-1,4-Naphthoquinone-Benzamide Derivatives as Apoptosis Inducers. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bosc, D. Click Reactions in Medicinal Chemistry. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hein, J.E.; Fokin, V.V. Copper-Catalyzed Azide–Alkyne Cycloaddition (CuAAC) and beyond: New Reactivity of Copper(I) Acetylides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 1302–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Gu, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, B.; Jin, W.; Li, J.; Ma, P.; Xu, H.; Hou, W. Strategic Application of CuAAC Click Chemistry in the Modification of Natural Products for Anticancer Activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2023, 9, 100113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa Souza, R.M.; Montenegro Pimentel, L.M.L.; Ferreira, L.K.M.; Pereira, V.R.A.; Santos, A.C.D.S.; Dantas, W.M.; Silva, C.J.O.; De Medeiros Brito, R.M.; Andrade, J.L.; De Andrade-Neto, V.F.; et al. Biological Activity of 1,2,3-Triazole-2-Amino-1,4-Naphthoquinone Derivatives and Their Evaluation as Therapeutic Strategy for Malaria Control. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 255, 115400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diogo, E.B.T.; Dias, G.G.; Rodrigues, B.L.; Guimarães, T.T.; Valença, W.O.; Camara, C.A.; De Oliveira, R.N.; Da Silva, M.G.; Ferreira, V.F.; De Paiva, Y.G.; et al. Synthesis and Anti-Trypanosoma cruzi Activity of Naphthoquinone-Containing Triazoles: Electrochemical Studies on the Effects of the Quinoidal Moiety. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 6337–6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megersa, A.; Nardos, A.; Ketema, T.; Deyno, S. Antileishmanial Activities of Methanol Extract and Solvent Fraction of Clematis Simensis Fresen Roots. Adv. Pharmacol. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 2025, 9671079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimanga, R.K.; Kambu, K.; Tona, L.; Hermans, N.; Apers, S.; Totté, J.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J. Cytotoxicity and in Vitro Susceptibility of Entamoeba Histolytica to Morinda Morindoides Leaf Extracts and Its Isolated Constituents. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2006, 107, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E.M.; da Silva, P.B.; Nefertiti, A.S.G.; Ismail, M.A.; Arafa, R.K.; Tao, B.; Nixon-Smith, C.K.; Boykin, D.W.; Soeiro, M.N.C. Trypanocidal Activity and Selectivity in Vitro of Aromatic Amidine Compounds upon Bloodstream and Intracellular Forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. Exp. Parasitol. 2011, 127, 429–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandazhinskaya, A.; Matyugina, E.; Shirokova, E. Anti-HIV Therapy with AZT Prodrugs: AZT Phosphonate Derivatives, Current State and Prospects. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2010, 6, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, C.A.; Bouvier, L.A.; De Los Milagros Cámara, M.; Miranda, M.R. Singular Features of Trypanosomatids’ Phosphotransferases Involved in Cell Energy Management. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 576483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.R.; Sayé, M.; Reigada, C.; Galceran, F.; Rengifo, M.; Maciel, B.J.; Digirolamo, F.A.; Pereira, C.A. Revisiting Trypanosomatid Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinases. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2022, 116, e210339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, M.S.; Neves, L.X.; Campos, J.M.; Roatt, B.M.; De Oliveira Aguiar Soares, R.D.; Braga, S.L.; De Melo Resende, D.; Reis, A.B.; Castro-Borges, W. Shotgun Proteomics to Unravel the Complexity of the Leishmania Infantum Exoproteome and the Relative Abundance of Its Constituents. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2014, 195, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de los Milagros Cámara, M.; Bouvier, L.; Reigada, C.; Digirolamo, F.A.; Sayé, M.; Pereira, C.A. A Novel Stage-Specific Glycosomal Nucleoside Diphosphate Kinase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Folia Parasitol. 2017, 64, 2017.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, R.; Sethi, K.; Kumar, S.; Varma, R.S.; Kumar, R. Natural Naphthoquinones and Their Derivatives as Potential Drug Molecules against Trypanosome Parasites. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2022, 100, 786–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrhardt, K.; Davioud-Charvet, E.; Ke, H.; Vaidya, A.B.; Lanzer, M.; Deponte, M. The Antimalarial Activities of Methylene Blue and the 1,4-Naphthoquinone 3-[4-(Trifluoromethyl)Benzyl]-Menadione Are Not Due to Inhibition of the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastián-Pérez, V.; Martínez de Iturrate, P.; Nácher-Vázquez, M.; Nóvoa, L.; Pérez, C.; Campillo, N.E.; Gil, C.; Rivas, L. Naphthoquinone as a New Chemical Scaffold for Leishmanicidal Inhibitors of Leishmania GSK-3. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieretti, S.; Haanstra, J.R.; Mazet, M.; Perozzo, R.; Bergamini, C.; Prati, F.; Fato, R.; Lenaz, G.; Capranico, G.; Brun, R.; et al. Naphthoquinone Derivatives Exert Their Antitrypanosomal Activity via a Multi-Target Mechanism. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, G.A.; Chaves, L.d.S.; Velez, A.S.M.M.; Lacerda, J.L.F.; Pitasse-Santos, P.; dos Santos, J.C.C.; Chaves, O.A.; Serpa, C.; Valente, R.d.C.; da Fonseca, L.M.; et al. Design and Synthesis of Bis-Chalcones as Curcumin Simplified Analogs and Assessment of Their Antiproliferative Activities Against Human Lung Cancer Cells and Trypanosoma cruzi Amastigotes. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilherme, L.; Do Nascimento, A.; Barbetta, M.F.S.; Chaves, O.A.; De Oliveira, A.R.M.; Nikolaou, S. Interaction of a Triruthenium Ortho-Metallated Phenazine with Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2024, 35, 20240136–20240137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.