Abstract

In the 21st century, Urbanization, population growth, and climate change have created significant problems in water resource management. Recent advancements in technologies such as Internet of Things (IoT), Edge Computing (EC), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Big Data Analytics (BDA) are changing the operations of the water resource management systems. In this study, we present a systematic review, highlighting the contributions of these technologies in water management systems. More specifically, we highlight the IoT and EC water monitoring systems that enable real-time sensing of water quality and consumption. In addition, AI methods for anomaly detection and predictive maintenance are reviewed, focusing on water demand forecasting. BDA methods are also discussed, highlighting their ability to integrate data from different data sources, such as sensors and historical data. Additionally, a discussion is provided of how Water management systems could enhance sustainability, resilience, and efficiency by combining big data, IoT, EC, and AI. Lastly, future directions are outlined regarding how state-of-the-art technologies may further support efficient water resources management.

1. Introduction

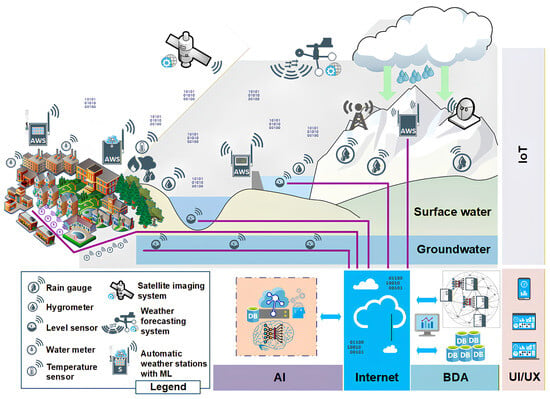

The protection and management of water resources have become a top priority of the scientific, social, and technological agenda of the 21st century, as the impacts of climate change, rapid urbanization, and increased water demand threaten the sustainability and security of water resources on a global scale. Traditional water management methods, based on periodic measurements, bureaucratic procedures, and slow decision-making processes, are no longer an acceptable model for solving the complex and dynamic challenges of water management systems in real time [1,2,3,4]. These growing pressures demand innovative, real-time solutions to ensure water security and sustainability for both current and future generations. Smart water resources management enabled by IoT, EC, AI, and BDA, represents a new paradigm and is emerging as a defining innovation in the scientific and technical development of the field [5,6,7]. In Figure 1, we illustrate a potential architecture of a smart water resource management framework integrating IoT, EC, AI, and BDA.

Figure 1.

Framework of smart water resource management integrating IoT, EC, AI, and BDA.

In more detail, this figure can be viewed as a hierarchical, feedback-enabled pipeline. At the IoT layer, heterogeneous sensors collect raw spatiotemporal measurements (e.g., level, flow, pressure, and quality indicators) along with metadata (e.g., location and timestamps). At the EC layer, local filtering, compression, feature extraction, and event detection are performed under stringent latency and energy constraints, enabling near-real-time responses even under intermittent connectivity. At the AI layer, features are transformed into actionable inferences (e.g., forecasting, anomaly/leak detection, and classification of risk states) and decision variables (e.g., predicted demand, leak probability, and flood-risk score). At the BDA layer, scalable storage and governance are provided; multi-source datasets are fused (IoT streams, historical records, and remote sensing/GIS), and both batch learning and continuous model updates are supported.

To be more explicit about synergistic mechanisms, the main upward data-flow (corresponding to assimilation) starts with IoT measurements and metadata, curated at the edge into cleaned streams, compressed representations, features and event flags, and is ingested by AI models to provide predictions, classifications, anomaly scores, and decision variables. Outputs are fed into the BDA layer, which fuses with historic and GIS/remote-sensing sources to provide fused datasets and governance controls, dashboards, and model lifecycle support. The downward coupling path completes when BDA- and AI-derived outputs (policies, thresholds, alerts, and recommendations) inform operational actions (alarms, maintenance schedules, and actuator settings) that change hydraulic and environmental states, and therefore change sensor observations. The closed-loop cyber–physical feedback cycle is made explicit. From a complex-systems point of view, the hierarchy described above may be considered an interacting set of subsystems connected by feedback, delays, and nonlinear dynamics, such that system-level behavior emerges from cross-layer coupling and adaptation (which includes continuous model updates) in a manner consistent with General Systems Theory and system dynamics formulations. The framing is also consistent with cyber–physical systems theory, and complex adaptive systems ideas, focusing on monitoring, control, and emergent behavior under changing operating conditions.

In real-world deployments of intelligent water management systems, value is only created if the entire pipeline from sensing to actuation reliably functions under real-time and governance requirements. A typical workflow encompasses: (i) heterogeneous data ingestion from distributed IoT nodes (hydraulic, meteorological, water-quality, and infrastructure state), (ii) pre-processing on edge-side (filtering, denoising, temporal alignment, compression, and feature extraction) to reduce bandwidth and latency, (iii) data ingestion through an integration layer supporting both streaming and batch workloads, (iv) data storage in scalable data architectures such as time-series databases and data lakes, (v) analytics and AI model training and inference, and (vi) decision support and control actions including alerts, valve and pump scheduling, leakage localization and demand management. The technical feasibility of this sensing-to-action pipeline is constrained by network reliability, data quality, computational and energy budgets on the edge, and compliance requirements that impact storage, sharing, and access control.

The deployment of IoT systems in water resources management relies on the continuous collection of data from hundreds or thousands of wireless sensors distributed across natural ecosystems, aqueducts, storage ponds, industrial facilities, urban networks, and agricultural systems [8,9,10,11]. IoT enables the monitoring of qualitative and quantitative parameters, supporting real-time water resource management systems, anomaly detection, predictive maintenance, and targeted resource allocation [12,13,14,15]. In agriculture, for example, IoT-enabled irrigation networks and soil moisture and temperature sensors can provide data for automated and efficient water distribution to minimize losses and optimize agricultural production [16,17,18,19]. In urban areas, wireless smart monitoring systems enhance transparency in water supply networks, security, and offer an energy-efficient water management system [20,21,22,23]. In addition, the contribution of AI plays a crucial role, both as an autonomous analysis tool and as a predictive planning and decision-making tool. Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) algorithms enable new frameworks for BDA and pattern recognition, providing reliable predictions for floods, water shortages, pollution risks, and energy needs [24,25,26,27]. AI-based automated control systems can integrate predictive analytics into water supply networks, wastewater treatment facilities, and lake and river management systems to adapt to changing environmental and social conditions [28,29,30,31]. Furthermore, BDA serves as the fundamental infrastructure that connects IoT with AI in water resource management. The large- scale accumulation of heterogeneous data, such as sensors, satellites, operational data, historical records, and geospatial data, provides the basis for the development of advanced algorithms aiming at balancing supply and demand, forecasting extreme events, improving transparency, and interconnecting data from different domains and applications [32,33,34,35]. The use of open data and cloud platforms enables fast and secure decision-making, enhancing real-time monitoring and infrastructure reliability [36,37,38,39,40].

Among its contributions, this paper reviews current technologies and applications in water resource management systems, focusing on IoT, EC sensing infrastructures, AI-driven data analytics, and BDA platforms. In more detail, in contrast to previous surveys that focus on individual technological components of water management systems (e.g., IoT sensing, AI forecasting, or data platforms in isolation), this review presents:

- An integrated overview of the IoT, EC, AI, and BDA technology chain, illustrating how sensing, edge analytics, learning, and data governance work together to underpin intelligent water management.

- We analyze the application of these technologies towards monitoring and controlling water resources sustainability in agriculture and urban water networks.

- A collaborative technology–management–policy lens, arguing that large-scale adoption will be possible only if intelligent systems are designed and operated to jointly align technical architectures with standards, organizational processes, security and privacy requirements, and regulatory frameworks.

- A digital-twin maturity model for water systems, outlining a continuum of capability levels—from basic monitoring to predictive and closed-loop operational twins that leverage simulation for optimization.

- We discuss the existing literature gaps, the limitations of current approaches, and future directions for smart water management solutions.

The document is organized into eight sections. The systematic literature review (SLR) approach employed in this article is described in Section 2. The definition of the research questions (RQs) is described in Section 3. Next, in Section 4, we provide the research process. In Section 5, we provide a summary of the collected papers. In Section 6 we provide the challenges and limitations of this field. In Section 7, we provide the future trends and research directions, and we finally conclude this review in Section 8.

2. Background and Context

Water shortages, in recent years has been caused by many different factors: including population growth and urbanization, the increasing demand for water resources worldwide, and the unstable resource availability due to climate change, environmental degradation, and aquifer overexploitation. Global water demand is projected to grow by 56% by 2025, and 4.4 billion people experience water insecurity, according to new scientific studies [41,42,43,44].

At the same time, many studies highlight that insufficient and unpredictable rainfall distribution, desertification, and the increasing variability in the hydrological cycle are creating an increasing gap between supply and demand, with direct consequences for agricultural productivity, industrial growth, and urban water supply [45,46,47,48]. Furthermore, water quality represents an equally crucial challenge that arises from the uncontrolled spread of pollutants and contaminants in surface and groundwater bodies. The main sources of pollution include industrial waste disposal, excessive use of agricultural fertilizers and pesticides, leakage from urban sewage infrastructure and untreated wastewater, while seawater intrusion into coastal aquifers caused by overpumping further increases the problems of salinization [29,49,50,51].

Extensive research shows that traditional methods of monitoring and quality control face major limitations, including time-consuming laboratory analyses, limited spatio-temporal coverage of measurements, and delays in anomaly detection that may lead to irreversible contamination of drinking water and ecosystems [9,52,53,54]. Water quality control is a major technological problem, mainly in developing countries, due to the lack of proper infrastructure. High mortality rates from diseases spread through contaminated water were directly related to this challenge. Additionally, water management infrastructure challenges include obsolete harvesting and delivery technologies, complex interoperability, and poor coordination between agencies [55,56,57,58]. Water losses in distribution networks in many countries range from 20% to 50%. These losses are basically caused by leakage, poor maintenance, and aging construction materials, which are the main issues of the losses in water distribution networks [59,60,61,62]. Water treatment facilities and irrigation systems face serious problems. Insufficient capacity, technology obsolescence, and limited adaptability to changing supply and demand conditions are the main issues. These challenges are further compounded by fragmented administrative structures. A lack of proper management standards results in poorly coordinated decision-making, overlapping responsibilities, and insufficient resource allocation [63,64,65,66,67]. These problems are further intensified by the lack of digital monitoring tools, forcing administrators to rely on periodic measurements and historical data, which cannot be used immediately to respond to critical situations.

3. Methodology and Research Questions

This literature review follows a systematic methodological approach to identify and analyze recent and significant scientific contributions in the field of intelligent water resource management based on IoT technologies, AI, and BDA. Using this methodology, both the current state as well as the future developments of digital water management are analyzed, which is characterized by ongoing technological innovations, various application aspects, and challenging implementation issues. It covers publications from 2023 to 2025 only and includes works that reflect the most recent findings and scientific advances in this area. The 2023–2025 time horizon is an arbitrary scoping choice. This review focuses on the latest generation of integrated IoT, EC, AI, and BDA systems, in which edge-enabled deployments, modern AI workflows, and contemporary data platforms are rapidly maturing. Narrowing the systematic extraction and quantitative synthesis to this horizon increases the comparability across sources by eliminating a substantial fraction of confounding differences related to legacy architectures and earlier-generation toolchains. Foundational work is only included as contextual background information, not as part of the quantitative synthesis, but the core evidence base is deliberately recent to reflect near-future trends in next-generation smart water management. This time frame guarantees that findings are recent and aligned with emerging trends that will influence the future of smart water management. This review identifies the most commonly applied technological approaches, like BDA, AI, and IoT, in water resource management. Thus, the RQs defined are the following:

- RQ1: Which IoT protocols improve real-time water monitoring and management?

- RQ2: Which are the most effective and utilized AI methods or models used for predictive analytics in water resource management systems?

- RQ3: What are the most common use cases of BDA in water resource management?

To operationalize the notion of “effective” as it relates to RQ2, we compared the performance of reviewed studies using task-appropriate evaluation metrics. For forecasting/regression tasks, the most commonly reported measures are MAE, RMSE/MSE and (and, for hydrologic prediction, Nash–Sutcliffe efficiency). For classification and detection tasks (e.g., leakage or anomaly detection), the studies commonly report accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. In addition to predictive performance, we also considered deployment-relevant indicators when provided, including inference latency, computational and memory requirements, communication overhead, energy consumption, and robustness to sensor noise, missing data and seasonal/non-stationary behavior.

This systematic review was not registered in PROSPERO, OSF, or any similar review registry. Non-registration of this work was an intentional decision. This is a technology-focused systematic review of integration of IoT-EC–AI–BDA for intelligent water management and does not involve human-subjects interventions or clinical outcomes where preregistration of systematic reviews is expected or required. For transparency and reproducibility purposes even in the case of a non-registered systematic review, the Methods section reports the full review protocol of the study, including the databases searched with time period and strings, inclusion/exclusion criteria, PRISMA screening workflow, and quality assessment procedure of the included studies.

4. Research Process

This systematic literature review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. To provide a better understanding of smart water resource management, this review examines studies addressing three topics: AI, BDA, and IoT. The search and selection of sources was based on specified criteria to ensure the quality and relevance of the works retrieved. Search Terms and keywords like “Water Resource Management”, “IoT water resource”, “AI water resource management”, “Water Demand Forecasting”, “Big Data Analytics” were used. Data collection was conducted by systematic searches of major academic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, IEEE Xplore Digital Library, SpringerLink, ScienceDirect, and Google Scholar. The identified papers underwent an initial screening based on titles and abstracts, followed by a full read for final selection. Only papers meeting the following criteria were included:

- Articles related to IoT, EC, AI, and BDA technologies specifically in water management or water demand forecasting applications.

- Publication must be from 2023 to 2025 to ensure relevance to the latest research trends.

- Publication must be in English to ensure understanding and comparability between sources.

- Scientific validity, articles that are published in recognized academic journals and conference proceedings, which are registered in databases.

Exclusion criteria were applied to remove studies that did not satisfy the inclusion requirements. Exclusion criteria included:

- Papers not directly focused on water resource management.

- Studies without a clear reference to IoT, EC, AI, or BDA technologies.

- Doctoral dissertations and technical reports without peer review papers published outside the specified time frame.

In the initial search and selection process, 236 scientific publications were identified that met the thematic criteria. However, after thorough screening and exclusion of papers that did not satisfy the required quality and thematic criteria, 109 papers were selected for further analysis. Content analysis of selected papers followed the thematic classification into IoT sensors and networks, AI, and BDA research areas. Quantitative analysis of all 107 chosen studies reveals a wide range of technological fields reflecting current research priorities. With 40 papers, IoT-focused studies dominate, highlighting the central role of sensors and real-time monitoring systems in water management. These are followed by 58 studies on AI and ML confirming the growing role of prediction, optimization, and automation algorithms. In addition, BDA papers represent 9 studies, suggesting that BDA is often used as a supporting tool within the other two categories rather than as an independent field of research. The literature review covers geographically diverse regions and a wide range of climatic conditions (developed countries: USA, Europe, Japan; developing economies: China, India, Brazil; regions with acute water security issues: Middle East, North Africa, Australia). This diversity enables conclusions that are not restricted to specific climatic or socioeconomic contexts systems but instead reflect global trends and challenges. For increased transparency and reproducibility, the database-specific full search strategy is provided in Table 1. In addition to relevance to the themes of the review, each potential included study was assessed on a structured quality checklist to ensure scientific validity and reproducibility. These included:

Table 1.

Database search strategy and identification counts aligned with the PRISMA flow diagram.

- Did the study describe the system(s). (hardware/software, datasets, context of deployment)?

- Did the study report on a validation approach (simulation, lab, pilot/field)?

- Did the study report on evaluation metrics and baselines?

- Did the study describe data sources and preprocessing?

- Did the study report on limitations/threats to validity?

The detailed scoring criterion table is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Quality assessment criteria and scoring rubric used in the review.

5. Literature Review

5.1. IoT, EC in Water Management

A smart water resource management system based on multi-criteria IoT-based sensors with adaptive architectures for urban and rural facilities is proposed in Mangalraj et al. [68]. The proposed systems adapt ML models to local conditions to generate optimal management solutions. This study highlights that flexibility and adaptivity are required during IoT system design to meet the requirements of different application environments.

A recent study by Haiyan and Yanhui [69] presents an IoT-based accurate irrigation platform that uses soil moisture sensors and PID controllers for automated irrigation, therefore achieving 28% water savings. The system maintains optimal soil moisture levels through accurate control of water valves and pumps based on real-time sensor data and weather forecasts.

Recently, the work of [70] presents a real-time water level monitoring system based on ESP32 microcontrollers for critical infrastructure, incorporating advanced encryption and secure communication techniques. The system achieves 98.5% measurement accuracy with latency lower than 500 ms and transmits encrypted data to prevent cyberattacks. The application demonstrates the critical importance of security in IoT systems, protecting critical infrastructures, and emphasizes that security should be considered from the design phase.

Prior research of [71] suggests an IoT system for ecological monitoring employing dual sensors for water level, turbidity, pH, and dissolved oxygen, connected to solar-powered wireless modules for autonomous operation. This system can reduce operational costs by 62% through the use of IoT components and solar energy, while improving water level measurement accuracy by 18% and water quality detection by 12% compared to single-sensor systems. The application demonstrates how solar IoT systems can be used for environmental monitoring in remote areas without access to power grid.

Furthermore, this work [72] presents HydroDrone, a distributed IoT task management system based on autonomous drones for monitoring large water areas. The system implements an advanced blockchain-based mechanism for secure data and tasks management, and provides an improved water monitoring performance through a multi-drone architecture. The approach demonstrates how autonomous IoT systems can monitor water resources across large geographical areas and in inaccessible locations.

Recently, ref. [73] developed a fully integrated smart water management system for water conservation that combines multiple IoT monitoring sensors with advanced optimization algorithms to maximize water resource use efficiency. The system consists of water quality, water level, flow, and pressure sensors with central nodes that process data in real time to enable automatic decisions regarding water distribution and savings. The application achieves considerable water saving through consumption pattern monitoring, leak detection, and predictive water demand management, demonstrating the effectiveness of integrated IoT solutions for sustainable water management. This study emphasizes that technological tools must be integrated to produce measurable savings and environmentally responsible water management practices.

Previous research [74] deploys a real-time water level and supply monitoring station in a case study of the Sakarya River using an integrated IoT system consisting of ultrasonic level sensors and pressure transducers coupled to telemetry units to continuous hydrological monitoring. The system achieves extremely accurate ( mm) and performs real-time flow calculations with integrated algorithms that combine data from multiple sensors to improve reliability. The application contributes to improved water resource management and flood prevention through an early warning system that analyzes water level and flow trends, and transmits the data to a centralized monitoring station for hydrological assessment in the drainage basin. This work demonstrates that IoT systems can be useful for hydrological monitoring of large water bodies and critical information for management decision-making, which is a representative model for similar applications in other river basins.

In [75], a smart water system was developed that combines IoT technologies for advanced pressure management and water loss reduction of distribution networks. The system uses networked sensors, data loggers, advanced modems, GIS and remote sensing technologies to continuously monitor pressure patterns, achieving an average water use reduction of 41.83% 527.66 . This work was conducted in a mountainous region serving 1670 users and revealed significant pressure variations during nighttime hours. The application combines hydraulic modeling using WaterGEMS and network analysis ArcGIS-ArcMap software 10.8.1, providing geospatial data and IoT-based solutions for smart pressure management, demonstrating the efficiency of combined IoT-GIS systems to reduce non-revenue water and achieve drinking water savings.

The study of [76] shows an IoT water distribution and monitoring system as an initial step towards a complete water quality and quantity monitoring solution based on a network of wireless sensors. Using ultrasonic sensors for level measurement, pH sensors for water quality assessment, flow sensors for consumption monitoring, and ESP microcontrollers for data collection and transmission via Wireless modules (Wi-Fi), the system enables at real-time detection and tracking of any changes in water quality. The application prevents water from being wasted in overflowing tanks of homes, schools, hospitals, and municipal reservoirs through automatic monitoring and control of water levels. The system includes a mathematical model that calculates water volume, flow rate, and consumption reports, providing an integrated solution that combines water quality control with distribution management.

Recently published work [77] explores the prospects for sustainable water management through a set of holistic digital tools designed to support effective and environmentally friendly water management. In domestic, industrial, and agricultural applications, IoT sensors and smart meters deliver real-time data with respect to water levels, quality, and consumption, while AI algorithms deliver predictive analysis of demand, rainfall distribution, underground water levels, and drought risks. Combined BDA reveals trends and correlations, whereas GIS and remote sensing provide accurate maps for spatiotemporal monitoring of water bodies, land use, and environmental changes. The system analysed in [78] is an Industrial IoT-based platform for monitoring and evaluation of water resources. Central to the implementation is the AquaTROLL 600 analyzer, a multiparameter instrument equipped with pH, turbidity, ammonia connectors, temperature, and pressure sensors for dynamic multifaceted measurement of critical water quality indicators of springs, reservoirs, groundwater, and coastal water systems. The device is connected via cable to a microcontroller, and its external storage has RS-485, SDI-12, and Bluetooth communications interfaces, which can be modified according to physical medium and application requirements. The collected data are transferred to users in real-time via Wi-Fi (for short distances), or NB-IoT/LTE modules for longer distances in industrial environments, with the ESP-32 serving as the main hardware, and the Vega NB-IoT-1335 a low-power modem. For data transfer and management, a cloud infrastructure is used (web server/MQTT broker) to reduce resource consumption, provide flexibility and speed of response, and allow scaling up with new sensor modules. The system allows full parameterization, real-time monitoring, digital notifications, remote control, and directly scalable integration in industrial facilities, urban infrastructure networks, automatic water system cleaning and restoration systems. Tests confirmed the reliability of the IoT framework for analysis and protection of water resources as a model for future applications of sustainable water management and monitoring in difficult environments.

Moreover, this study [79] presents a detailed study on optimal water resource management based on a smart IoT system involving distributed water level, flow, and quality sensors with real-time monitoring embedded in NB-IoT and LoRaWAN networks. The system applies an EC architecture to detect pressure anomalies and leaks in urban networks, while cloud-based platforms perform predictive analysis of demand and quality using ML. Ultrasonic sensors and pressure transducers are deployed in critical water supply infrastructure, achieving achieving level measurement accuracy level measurement accuracy and a 94% success rate in leak detection. Automated control valves governed by optimized algorithms reduce pump energy consumption and water losses by 20% and 30%, respectively. The work showcases the combined capabilities of IoT sensors, low-power communication networks, and AI in delivering efficient, resilient, and sustainable solutions for urban water management.

The article of [80] presents a smart water pump control system for domestic applications aimed at improving energy and water resource management through automation and remote monitoring. The system architecture is based on an Arduino microcontroller, which reads level data from a conductance-based sensor having four aluminum electrodes positioned at different tank heights, along with a corresponding sensor for the well. The circuit consists of a buzzer, relay, and pump motor with surge protection, an LCD display for local monitoring, and a GSM module for remote access. The user can control the operation and be informed via mobile devices. During operation, the pump is automatically activated at low water levels and stopped once the upper threshold is reached. Remote access via GSM enables residents to control the operating time for energy planning and load selection in the system. The result achieves a 34.44% reduction in electricity consumption and associated cost, while ensuring a continuous water supply without losses or overflows. The system can be extended for larger domestic and community, and industrial facilities and serves as a practical example of smart technology delivering direct benefits for energy and water sustainability.

Furthermore, ref. [81] presents an extensive solution for detecting leaks in underground water source systems, offering modern methods for managing drinking water losses in urbanized infrastructure. The device architecture is based on an ESP32 microcontroller with Wi-Fi connectivity and a wide range of sensors. The sensor to certify smooth flow in the pipes, turbidity for water quality control, ultrasonic sensors, and humidity sensors to identify losses or leaks, as well as to evaluate external environmental causes. Most data are collected and processed in real time on a cloud platform (Blynk), enabling community managers to receive immediate notifications and intervene in a coordinated manner through automated actions, such as flow interruption or source routing via pumps. Additionally, notifications are delivered even in situations of online loss by SMS/GPRS. The strategy also incorporates acoustic signal processing models and pressure measurements to detect micro-leakages, as well as time-domain reflectometry (TDR), ground-penetrating radar, fast Fourier transform (FFT) techniques, and image analysis to rapidly identify cracks or fractures within pipes. The system is recognized as highly effective in reducing operational losses, preventing secondary damage, and enhancing the resilience and sustainability of drinking water source systems, while providing transparent information and supporting rapid decision-making by maintenance managers.

A recent study of [82] presents a comprehensive multi-layered architecture for smart urban wastewater management and recycling, grounded on IoT, EC, and blockchain technologies. The system includes 5 distinct layers. These are the sensor layer in a pipeline systems, treatment units and storage tanks, where water flow and water quality measurements are captured. The data collection layer implemented through smart gateways, the EC layer where initial preprocessing, data management, and verification are performed using smart contracts, the cloud and blockchain layer where data history, integrity, and metadata transparency are ensured through Hyperledger Fabric, and the application layer that provides real time monitoring, big data analysis, incentives, and automated actions. Key functions are the interconnection of a wide range of virtual and physical sensors, quality assessment at key network receivers or industrial sites, and prediction of failures or anomalies using polynomial regression to identify deviations or intentional manipulation. The system also enables immediate awarding of tokens as exchangeable incentives, based on achieved recycling or purity rates, and provides online storage of immutable data for stakeholder evaluation. Peer-to-peer token sharing, real-time alerts, and rewards across public and private devices are supported. Reported performance includes a recycling rate of 96.3%, an efficiency ratio of 88.7%, and prediction accuracy of 92.5%. Overall, the approach combines advanced sensor nodes, wireless communication, decentralized accounting through blockchain, and anomaly detection algorithms to support secure, efficient, and transparent wastewater management and recycling in modern smart cities.

A smart water management system presented in [83] is an IoT-based system for urban and rural applications. The system employs ultrasonic sensors for water level measurement in tanks and reservoirs, along with flow sensors to record water flow and volume within the network. The NodeMCU serves as the central controller, responsible for collecting sensor data via wireless communication and transmitting them to a cloud platform for remote analysis. Automation is achieved through driver circuits controlling pumps and valves that regulate flow based on water level and flow data or detected leaks. Data processing and analysis are performed in real time using machine learning (ML) algorithms to detect anomalies, such as overconsumption and leaks, and to predict future water demand for targeted interventions. A graphical web-based interface provides real-time level visualization and alerts in critical situations.

Overall, IoT-based water resource management systems optimize water use, improve operational efficiency, and prevent leaks through integrated sensors and automated control mechanisms. These systems monitor water quality, level, flow, and pressure to enable early leak detection, targeted conservation strategies, and dynamic treatment adjustments. They utilize smart meters, leak sensors, and control units that communicate via wireless networks with a central cloud platform for data analysis and decision-making. As a result, these systems deliver water savings, reduced water costs, improved water quality, and predictive maintenance capabilities for water management in both urban and rural settings.

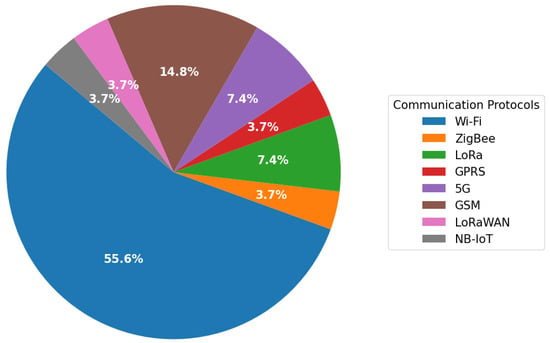

In Table 3, we provide a detailed summary of the boards, IoT protocols, and the variety of sensors that are used in the literature. In addition to that, we also provide a pie chart in Figure 2 of the IoT protocols used. Lastly, in Table 4 we provide a comparative summary of the IoT sensors classes used in the reviewed studies, and also, in Table 5, we provide a comparative summary of the IoT communication protocols used in the reviewed studies.

Table 3.

Summary of boards, protocols, and sensors used.

Figure 2.

Distribution of connectivity/bearer technologies.

Table 4.

Comparative summary of sensor classes used in the reviewed studies, with corresponding references from Table 3.

Table 5.

Comparative summary of IoT communication protocols used in the reviewed studies.

5.2. Artificial Intelligence Applications

An advanced multi-objective optimal regional water resource allocation, based on an improved NSGA-III algorithm, is presented in this article [38]. First, a model of three objectives is formulated. It includes total pumping and distribution cost, sustainability of groundwater and surface water reserves, environmental impact, more specifically, carbon emissions from pumping, and ecosystem degradation. The authors revise classic NSGA-III with dynamic reference point selection and a feedback-based population allocation to explore the solution space and minimize the risk of convergence to local optima. In the simulation phase they apply the new NSGA-III improved to a sub-basin data set with surface and groundwater sources based on 10 years of meteorological data with real infrastructure operation costs. The results show that the improved algorithm produces a more evenly distributed Pareto set with a 25% more generalized appearance than the classic NSGA-III and an 8% lower cost without compromising reserve sustainability. Sensitivity analysis also demonstrates that the system can tolerate up to 15% change in water demand and 20% change in energy cost, confirming the practical applicability of the framework for integrated and adaptive management of local water resources under uncertainty.

A short-term daily water demand forecasting ensemble DL model based on Seasonal and Trend decomposition using STL and AdaBoost-LSTM ensemble learning is presented in this study by [91]. The model addresses challenges in water demand prediction, including accuracy limitations, model complexity, and peak detection capability. The approach first preprocesses data using three criteria for outlier detection and weighted average smoothing, then decomposes the time series into trend, seasonal, and residual components using STL. Three separate AdaBoost-LSTM models process each component independently, with multiple LSTM base learners integrated through the AdaBoost algorithm to improve accuracy and stability. The system achieves exceptional performance with MAPE of 0.01% for both water plants (P1 and P2) in Yiwu City, China, outperforming nine comparison models, including traditional ARIMA, a single LSTM, and various hybrid approaches. Key innovations include automatic feature extraction through STL decomposition, ensemble learning for enhanced peak prediction, simplified parameter tuning with only 4 hyperparameters, and strong balance of accuracy, stability, and model simplicity. The model demonstrates practical applicability for intelligent water supply systems in water-scarce cities, with significantly lower complexity than existing hybrid models while maintaining state-of-the-art forecasting performance.

Prior research of [92] presents an innovative combined flood monitoring and prevention system that utilizes ML techniques in conjunction with IoT infrastructures. The system consists of an ultrasonic water level sensor, a rainfall sensor, and PLC controllers that collect real-time data over LoRaWAN. The data are fed to a Random Forest (RF) algorithm for flood risk classification and an LSTM model for flow time prediction. The classification accuracy was 98.7% and was 0.91 for six-hour warning prediction. Integrated EC reduces latency to 250 ms, and automated ground valve management enables flow diversion and mitigation of impacts. Pilot testing in a city environment revealed 30% reduction in water losses and a 45% increase in emergency response readiness. This project demonstrates how AI and IoT could benefit from each other for resilient flood risk management of water networks today.

In the work of [25], an image-based first-pass water quality classifier is presented. It uses CNNs and relies on colour and appearance to label samples as suitable or unsuitable for use. The dataset contains 200 images, consisting mainly of Indian rivers, captured using Google Earth and mobile devices, then resized and basic preprocessing is applied. The images are separated into training, validation and testing sets and classified into clean and polluted classes. The study follows a dataset training validation testing workflow. Experiments report headline accuracy bands and include method comparisons, with the CNN achieving 80% accuracy and performing better than an SVM baseline. A coarse performance table links accuracy bands to qualitative water-quality labels. The authors emphasize low cost, rapid screening, and field practicality while noticing limitations such as reliance on image only cues and the small dataset. They also mentioned future extensions to physico-chemical features such as pH, turbidity and dissolved oxygen, as well as app and GPS based deployment.

In the study by [2], downscaled GRACE data are combined with remote sensing and ground based instruments that are monitored locally using a surface water balance approach. The authors extract GRACE satellite measurements of water mass change at 25 km resolution, summarize Sentinel 2 image data for a vegetation index based on NDVI, and use climate data from meteorological stations to calculate evapotranspiration with the FAO 56 Penman Monteith model. Cross checking of the different data sources reveals that climate variability and human water use and irrigation control evapotranspiration, with values of 0.78 to 0.85 per investigated catchment. The study shows that GRACE based long term monitoring of groundwater reserves, combined with detailed remote sensing and ground data, enables precise evapotranspiration estimates that support proactive irrigation and sustainable water resources management.

A complex digital framework for assessing drinking water quality that incorporates artificial intelligence and soft computing techniques was developed by [28], using multi parameter IoT sensors to measure physicochemical and microbiological parameters. The system uses fuzzy logic, neural networks, and genetic algorithms to process complex nonlinear interactions between parameters, achieving 92% accuracy in predicting drinking water suitability. These algorithms simulate human decision making logic and provide a comprehensive quality assessment through intelligent big data processing.

In [93], the authors propose a novel adaptive multicriteria optimization/water resource allocation framework in Hancheng City based on the advanced NSGA and Technique for Order Preference based on similarity to ideal solution consensus-based criteria decision making model (TOPSIS-CCDM). First, the researchers construct a specialized objective function with three competing objectives. Firstly, minimising operating costs for water extraction/treatment. Secondly, maximising social benefit by ensuring adequate supply to vulnerable groups, reducing energy use and emissions. And last but not least, maintaining hydrological balance for sustainable aquifer exploitation. Then, they add an adaptive population reassignment mechanism with dynamically updated performance indicators to the classical NSGA to allow further exploration of the solution space under demand and energy cost uncertainty. After the genetic process is completed, the Pareto set of not-dominated solutions is evaluated via TOPSIS-CCDM with predefined weighting/agreement criteria for water managers/local stakeholders group participation. With the framework applied to real data of demand, tariff structures, and hydraulic network characteristics in Hancheng, the authors show that the combined approach saves 12% of total operating cost while maintaining a high social efficiency (95% satisfaction level) and 18% of emissions compared with single-criteria methods. In addition, TOPSIS-CCDM flexibility ensures that final solutions are based on stakeholder consensus, and dynamic climate variability scenarios together with cost uncertainties make the model suitable for long-term water system planning.

In the work of [24], a Multivariate Multiple Convolutional Networks with Long Short Term Memory technique called MCN LSTM is presented for real time anomaly detection in water quality monitoring systems. Using multivariate sensors, the method collects time series data, and a hybrid CNN LSTM model detects deviations from normal conditions with 92.3% accuracy, despite noise and high data influx. Statistical methods are shown to capture only extreme variations, while traditional machine learning offers limited generalization because it cannot represent complex spatiotemporal dependencies. In contrast, the MCN module extracts spatial patterns, while the LSTM captures temporal patterns, both of which are indicative of water quality anomalies. Therefore, this application demonstrates that deep learning techniques are reliable for early detection of water quality problems.

In [94], the authors developed a hybrid AI framework that combines Random Forest and fuzzy logic to forecast water demand and support non revenue water management for urban systems. Using large volumes of IoT data and historical records, the system achieves 90 to 93% accuracy in correcting non revenue water and improves distribution efficiency by 25% through automated pressure optimization.

This paper [95] examines AI applications in groundwater management, including predictive modeling, real time monitoring, data integration, decision support systems, and optimization algorithms. By combining several AI approaches rather than focusing on a single model, the study shows how various machine learning techniques, including SVM, Random Forest, and deep learning, are applied across a range of groundwater management scenarios. Features are selected based on hydrogeological expertise and typically include 8 to 15 parameters, such as groundwater levels, precipitation, temperature, land use, extraction rates, and geological characteristics. The main innovations discussed include AI powered decision support systems for conservation planning and resource allocation, IoT enabled real time monitoring systems that provide ongoing water quality evaluation, and optimization algorithms for sustainable pumping schedules. Challenges mentioned include the need for technical expertise, issues with model interpretability, and limitations in both data quantity and data quality. Future prospects include improved risk assessment frameworks for locating polluted areas, cooperative AI platforms for involving stakeholders in groundwater resource management, and enhanced predictive capability under climate change.

In the work of [96], a Combined Optimizer CO and Explainable AI based dam inflow prediction framework was presented. The CO overcomes classical gradient descent limitations related to forced updates due to restricted storage and convergence to local optima, by combining the Adam optimizer with the Vision Correction Algorithmic metaheuristic optimization and by decreasing the Gradient Descent Rate parameter with each epoch. The XAI implementation provides feature importance ranking based on Layer wise Relevance Propagation LRP. The Yangganggyo water level is the most influential factor, with a relevance score of 99.85, based on the automatic feature importance ranking. The Multi Layer Perceptron MLP architecture consists of five hidden layers with ten nodes, trained using flood season data from the Daecheong Dam basin in Korea. Data preparation includes Min Max Normalization, Time Lagged Cross Correlation with a one day optimal lag, and dropout of 0.05 for overfitting prevention. Results demonstrate significant improvements. The increased by 0.0664 compared to the existing optimizers, and RMSE was reduced to 678.49. Compared to conventional approaches, the Dual AI model predicts peak flow events better than traditional approaches and avoids tendencies to overestimate. Performance validation against the established AdamIHS optimizer consistently leads to better results in both verification and prediction phases, with higher and lower RMSE, supporting stable and interpretable flood management and water allocation strategies even under extremely variable hydrological conditions.

The work of [40] used satellite precipitation products as input to a hydrological model, HEC HMS, to simulate runoff in the Modjo catchment in Central Ethiopia. The PERSIANN CDR product, based on artificial neural networks, performed worse, with = 0.62, than CHIRPS, which combines high resolution satellite imagery with in situ station data to create gridded rainfall time series, with = 0.66, as well as actual observed data, with = 0.84. Therefore, further improvements in global precipitation products are required before they can replace observed data in hydrological applications.

Lastly, ref. [97] introduces and evaluates artificial intelligence models for predicting monthly rainfall at stations in Ethiopia without using conventional climate data, addressing significant limitations in local access to multidimensional measurements. The researchers focus on the application of artificial neural networks (ANN) and the adaptive neuro fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), exploiting geodynamic parameters and periodicity, including latitude, longitude, and altitude, to predict monthly rainfall distributions at 92 meteorological stations, using data from the last decade. The results show that ANFIS significantly outperforms ANN, achieving Nash Sutcliffe coefficients of 0.995 versus 0.935 across all comparative measurements. Furthermore, this methodology improves prospects for agricultural and hydrological management, especially in countries with limited access to complete climate records, and enhances tools for early prediction of catastrophic phenomena such as floods and droughts, as well as better policy planning in agriculture, insurance, and infrastructure. The article confirms the effectiveness of AI in producing reliable hydrological forecasts based exclusively on static geographical components and structured analysis of rainfall periodicity, and it opens new avenues for adopting non traditional methods in operational meteorology.

New research shows how AI, ML, and IoT are rapidly evolving in water resource management. Modern optimization algorithms, including enhanced NSGA III variants, allow simultaneous cost and emission reductions without compromising water resource sustainability. Emissions in this work indicate operational CO2 emissions based on time-varying grid emission factor and net amount of electricity consumed (pumping) or generated (turbining) by the MPS system. Emissions are reduced monthly by GA-based optimization of MPS operating states (pump/turbine/non-potable water supply/off) that shifts energy use and dispatch to lower-carbon and/or lower-price time slots, while enforcing storage limits and water-supply reliability through penalty-based soft constraints. For the range of building configurations analyzed, optimized schedules provide substantial emissions reductions with only limited loss of arbitrage revenue: 4–25% lower annual operational emissions in ES mode and 25–43% lower in NPWS mode. In NPWS cases that offset potable demand, accounting for water–energy nexus (WEN) benefits (avoided energy and emissions in the urban water distribution network) further increases total emission reduction to 52%, in addition to large water-bill savings [98]. IoT-based systems integrate sensors and ML algorithms for real-time water quality monitoring and flood prevention. At the same time, satellite data, including GRACE and Sentinel 2, combined with AI studies, reveal climate human interactions and enable proactive water management under uncertainty. Overall, the convergence of AI and IoT technologies is driving the development of intelligent, integrated, and robust water management systems that meet both operational and environmental challenges.

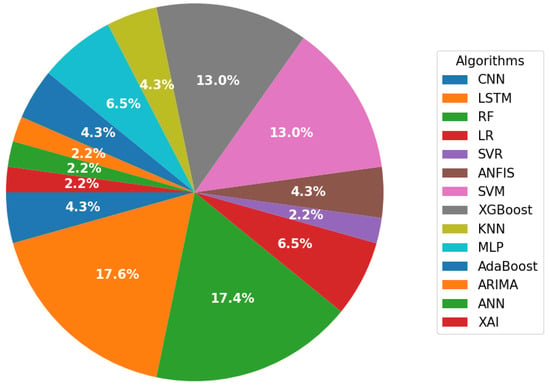

In Table 6, we provide a detailed summary of the ML or DL algorithm used, the classification or regression column, and the labeling methods, features of extraction, and lastly, the number of features used. In addition to that, we also provide a pie chart in Figure 3 of the AI models used. Lastly, in Table 7, we provide a comparative summary of AI model families and deployment considerations in the reviewed studies and in Table 8 we provide a summary of typical architectures, hyperparameter ranges, and training strategies for common AI models in water-resource prediction tasks.

Table 6.

Summary of the specifications of AI models used in water management.

Figure 3.

Pie chart of AI models used.

Table 7.

Comparative summary of AI model families and deployment considerations in the reviewed studies.

Table 8.

Typical architectures, hyperparameter ranges, and training strategies for common AI models in water-resource prediction tasks.

5.3. Big Data Analytics

The research by [39] examines in great detail the complex challenges Morocco faces in managing its water resources, focusing primarily on data collection, processing, and governance infrastructure. Through interviews with over 120 different entities, from national water agencies and research institutions to local cooperatives, and analysis of existing national databases, the authors reveal a highly fragmented structure of recording systems. Multiple public and private agencies collect similar hydrological, meteorological, and consumption data without common protocols or a shared platform, leading to 50% data redundancy and 30% inconsistencies in reports. Only 20% of monitoring stations operate continuously on a 24 h basis, while remote catchment areas have significant data gaps, resulting in delays of up to six months in reporting critical indicators such as groundwater levels and water quality. The authors point out that the lack of interoperability between geographic information systems GIS, IoT sensors, and traditional metering networks prevents the development of predictive analytics and automated control systems. As a solution, they propose establishing a unified Extract Transform Load environment to consolidate data, developing cloud based GIS platforms with real time update capabilities, and integrating satellite and remote sensing measurements to fill gaps in field monitoring. At the same time, they emphasize the need for institutional restructuring with a clear delineation of responsibilities, the adoption of open data standards, and stronger staff training in Big Data and AI technologies. The comprehensive implementation of these measures is considered necessary to address climate change, increasing demand, and ensure sustainable water resource management in Morocco.

This study [5] presents a comprehensive approach to smart water management through AI driven demand forecasting using big data from urban water distribution systems. The research uses high frequency water consumption information gathered from smart meters and flowmeters in Hubli city district metered areas to create large datasets of hourly consumption patterns over more than two years, along with meteorological variables from several weather stations. The big data application is used to develop sophisticated LSTM neural network models that can process large temporal datasets to predict short term water demand accurately, with = 0.89. The practical use case illustrates how water utilities can use continuous data streams from IoT enabled infrastructure to automate real time operations, including pump scheduling, pressure management, storage allocation, and distribution network optimization, in order to minimize operational costs and enhance service reliability for urban populations, with minimal water losses through predictive analytics.

The work of [101] examines the configuration and operation of a cutting edge water tank monitoring system, aiming to improve efficiency and sustainability in water resource management through IoT technologies. The proposed method relies on water level sensors, microcontrollers, and cloud platforms to ensure real time two way communication between the tanks and a central management interface. Information is continuously collected by the sensors, displayed directly on an LCD, and stored in a cloud computing environment, providing full visibility, high precision, and the potential for automatic consumption evaluation. The system applications range from household tanks to industrial storage tanks and agricultural irrigation networks, enabling users to prevent overflows, optimize consumption, and achieve considerable water savings through data driven decision making. IoT integration not only enables wireless, centrally controlled monitoring, but also supports proactive maintenance policies and continuous resource management in real time. In addition, user friendly interfaces and access from any device encourage active end user participation in making environmentally responsible decisions. Overall, the method emerges as a scalable and effective solution that can increase operational effectiveness, reduce water losses, and improve the sustainability of water management in modern urban and rural locations.

This paper [102] presents a comprehensive study of short term water demand forecasting using artificial intelligence, focusing on innovative ML and DL techniques. The system is built on real world water consumption data obtained from digital flow meters at 10 min intervals over a two year period, together with climatic conditions including temperature, humidity, pressure, and rainfall. It also includes temporal variables such as time of day. Nine different forecasting models are developed, including SVR, RF, XGBoost, KNN, ARIMA, and LSTM, with each model applied to a single variable case using water consumption only, as well as a multivariable case using climate and time variables. The data are normalized, evaluated using 10 fold cross validation, and assessed using the metrics R2, MAE, RMSE, and MSE. Results show that the LSTM model performs best among all the evaluated models. Correlation analysis indicates positive effects of temperature and time of day on consumption, and negative effects of humidity. The system can predict hourly fluctuations with morning and afternoon peaks, enabling pump operation optimization, proactive pressure control, and smart, sustainable water resource management.

The research by [103] develops a comprehensive approach to enhancing operational efficiency in water distribution networks through Smart Water Grids SWG that combine digital twin technology with real time IoT systems to create digital copies of water supply networks. The methodology combines real time data from IoT sensors, including supply, pressure, and leak events, with physical hydraulic models based on flow equations to create and continuously update a virtual replica of the network. This enables scenario simulations for pump scheduling, valve adjustments, and leak response, while a cloud edge architecture supports low latency data processing and control commands that enable real time preventive actions. The results of pilot applications in a metropolitan network demonstrate that the SWG system with a digital twin reduces pump energy consumption by 20% through optimized scheduling based on simulated demand scenarios, improves leak detection accuracy to 95% using anomaly thresholds driven by the digital twin, and reduces water losses by 18%. In addition, real time pressure control keeps network pressures within target limits 93% of the time, preventing pipe ruptures and minimizing leak propagation. Twin updates at the edge of the network achieve sub second synchronization delay, enabling proactive control actions, and scenario analysis identifies network upgrades that provide a 12% increase in resilience under extreme failure conditions. Overall, the study confirms the value of digital twins in supporting data driven optimization and resilience in modern water networks facing increasing challenges from climate change, urbanization, and aging infrastructure.

Wherever tourism is a significant driver of economic development, tourism driven water consumption may constitute a major share of overall water use. The study of [36] performs semi automatic tracking of residential swimming pools using freely available aerial photography on Mykonos Island, Greece. Pool localization was carried out in QGIS 3.16 and GIMP. First, the characteristic colour range of pools was defined, and then a centroid point map was constructed. The method achieved a 95% F1 score and revealed 40% pool growth over eight years, indicating that it can be used to infer trends in tourism related water consumption.

In response to water stress in touristic areas, ref. [104] brings together IoT and ML in a framework for real time monitoring, prediction, anomaly detection, and optimization of water consumption. User dashboards help hotels, resorts, and other tourism related facilities reduce water waste, improve operational efficiency, and enable automatic water delivery systems. A case study demonstrated that the framework can reduce water usage by 30% per year. However, the work is presented at an architectural level, and no details on the specific ML methods are provided.

In this paper [105], researchers harness optoelectronic detection technology, arguing that traditional sensing methods may cause secondary pollution. Using this technology, they collected large scale spectral data from ten operational water treatment facilities, where optical sensors capture high-resolution UV-visible spectra corresponding to multiple water quality indicators. By applying AI data mining algorithms to these spectral datasets, the study demonstrates a 41% reduction in monitoring time, from 4.6 to 2.7 days, a 16% increase in accuracy, from 74.1% to 85.9%, a 26% improvement in sensitivity, and a 19% higher protective score compared to traditional methods. This big data application illustrates how integrating AI with optical spectroscopy can transform water quality management, enabling rapid, precise, and comprehensive monitoring that is essential for safeguarding public health and environmental resources. However, the paper provides limited information on the specific AI techniques used in the study.

Lastly, ref. [106] presents an overall secure framework for water resources. Management and leak detection of urban networks using blockchain and IoT technologies to enhance the distribution networks in terms of accuracy, transparency, and resilience. Architecture based on pressure, flow, and water is proposed. Quality sensors at key points communicate via blockchain middleware, Hyperledger Fabric, to a central dashboard. Smart Contracts guarantee that each measurement is authentic and therefore cannot be subverted by injecting false measurements. Matic filtering of incorrect inputs simultaneously provides competent services. Triggers activated by the system inform them in real time of leakage or failure incidents. In parallel work, dynamic consumption recording and costing support are provided. Preventive maintenance notifications and detailed analysis of urban losses by sector or customer are provided. The experimental application shows an increase. Faster leak detection speed, up to 30–40% reduction in operational losses, and increased confidence in management with a universal, immutable transaction record. The article documents that the combination of blockchain with IoT can provide a solid basis for the management of urban water resources while also securing networks against cyberattacks and enabling the participation of multiple stakeholders, a model innovation for modern cities demanding transparency and efficiency.

Recent works highlight BDA for water resource management. Massive and heterogeneous datasets, such as sensors, satellites, and monitoring networks, are fused through cloud-based and IoT-enabled infrastructures. Advanced analytical models like LSTM and RF use these data streams to forecast water demand, reservoir inflows, and consumption patterns for dynamic system optimization. BDA also improves water quality assessment with AI-supported sensors and provides predictive maintenance, detecting leaks and anomalies before system failures happen. In addition, the fusion of IoT and BDA enables continuous monitoring along with automated control in urban and agricultural water systems. Overall, BDA provides an underpinning for intelligent, adaptive, and resilient water management decisions under increasing environmental and operational challenges.

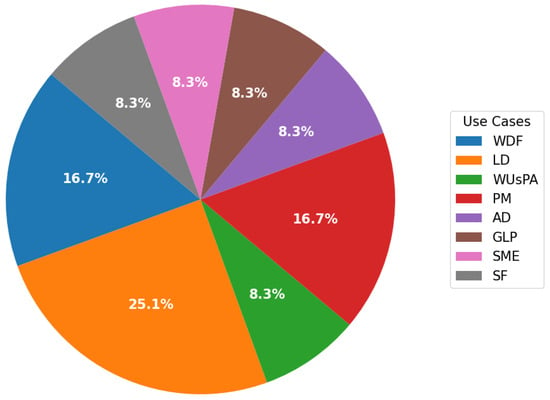

In Table 9, we provide a summary of the Data sources and the use case of BDA applications in the literature. In addition to that, we also provide a pie chart in Figure 4 of the use cases of BDA systems. Lastly, in Table 10, we provide a comparative summary of BDA platform archetypes and deployment considerations of the reviewed studies.

Table 9.

Summary of BDA specifications.

Figure 4.

Pie chart of BDA use cases.

Table 10.

Comparative summary of BDA platform archetypes and deployment considerations in the reviewed studies.

Although (BDA) enables scalable processing and long-term knowledge discovery, its integration into water management systems is non-trivial due to the heterogeneity, spatiotemporal structure, and operational criticality of water-related data. First, data heterogeneity complicates harmonization as field deployments commonly combine time-series sensor streams, SCADA logs, hydraulic model outputs, satellite and radar products, maintenance records, and citizen reports, each characterized by different sampling rates, units, reliability, and semantics representations. This heterogeneity motivates robust Extract-Transform-Load (ETL) processes that address challenges such as time synchronization, schema evolution, sensor metadata management, and semantic interoperability (e.g., consistent identifiers for assets, locations, and events).

Second, latency requirements directly affect system design. Many operational tasks, such as flood alerts, contamination detection, and pressure anomalies, require low-latency stream processing, while planning tasks, including asset management and seasonal demand forecasting, benefit from batch analytics. Maintaining correctness across both processing modes requires exactly-once ingestions semantics, back-pressure handling, and resilient buffering during network outages, which are frequent in remote or disaster-prone environments.

Third, data quality issues represent persistent constraints. Water datasets often exhibit missingness due to sensor downtime, outliers caused by biofouling, sensor drift, electromagnetic interference, and non-stationarity resulting from seasonality and abrupt regime changes. Without systematic provenance tracking, such as sensor calibration history, firmware versions, and location changes and quality flags, BDA pipelines risk producing misleading insights at scale.

Finally, governance and privacy constraints shape the permissible architecture. Even when data are not directly personal, fine-grained consumption patterns and geospatial traces can become sensitive. Practical BDA deployments therefore require role-based access control, encryption both in transit and at rest, well-defined data retention policies, and auditable data lineage. These requirements influence platform selection, cross-organization data sharing, and the feasibility of centralized versus federated analytics approaches.

5.4. Integrated Systems and Case Studies

The study by [84] explores the digital transformation of governance processes and water resources management in the Mediterranean agricultural sector, with the aim of enhancing sustainable water production and use strategies. The authors analyze the adoption of digital platforms that combine GIS, IoT sensors, and SaaS applications for real-time monitoring of soil moisture, irrigation water flow, and quality. Furthermore, they propose the integration of blockchain-based smart contracts to automate irrigation contracts between farmers and water providers, ensuring transparency in charges and immediate execution of payments based on actual consumption. The study presents pilot projects in three rural areas in Spain and Turkey, where digital processes reduced water losses in irrigation networks by 25% and increased crop yields by 15% through optimized resource management. At the same time, the policy analysis highlights the need to train rural communities in the use of digital tools and to formulate unified regulatory frameworks for data protection and cybersecurity. The integrated approach combines technological and institutional innovations, supporting the transition to a “smart agriculture” ecosystem that integrates environmental, economic, and social indicators for the sustainable management of water resources in the Mediterranean.

A recent study by [85] analyzes the role of unconventional water sources, including dewatering, desalination, and aquifer discovery, together with an IoT sensor network and ML models for smart water resource management and conservation in future cities. It applies a variety of ML algorithms, such as standard neural networks for classification and regression, as well as DL models for more complex water demand forecasting, while leveraging real time quality and consumption data for dynamic irrigation and water distribution regulation. The proposed solutions lead to improved demand forecast accuracy by up to 20 to 30%, reduced freshwater use for irrigation through ML based control, and improved aquifer adequacy through controlled recharge. However, challenges remain in data quality and uniformity, in integrating modern ML platforms with legacy water management systems, and in the need for specialized human resources to operate and maintain the algorithms.

The study of Leonila et al. [86] presents a dynamic water quality monitoring platform that combines a network of IoT sensors with ML techniques for proactive and immediate water resource management. The system is based on carefully selected IoT sensors that measure pH, turbidity, temperature, dissolved oxygen, conductivity, level, and ambient humidity, and these are placed in tanks, pipelines, and natural water bodies. The data are collected from a microcontroller, then preprocessed and synchronized before being sent to a cloud infrastructure for further analysis. A central role is played by ML algorithms, including RF, Gradient Boosting, SVR, MLP, LSTM, and KNN, which are trained on historical data to predict critical parameters and detect anomalies or contamination in real time. The system achieves high forecasting accuracy and rapid identification of deviations, enabling immediate notification of managers and supporting the planning of corrective actions for environmental protection and the safety of water networks. The interface includes dashboards and applications with live data, predictive indicators, and trend visualizations to support timely decision making.

Furthermore, this editorial [107] synthesizes insights from thirteen state of the art studies that leverage diverse, large scale hydrological and environmental datasets, including continuous streamflow and rainfall gauge records, high resolution satellite derived precipitation and soil moisture time series, and real time IoT sensor networks monitoring water levels, pressures, and quality parameters, to advance AI driven water resources management. By integrating these heterogeneous data sources, researchers applied a wide range of ML and DL techniques, including ANNs for streamflow prediction, LSTM models for soil moisture forecasting, gradient boosting and XGBoost for flood inundation depth estimation, CNNs combined with LSTM for remote sensing based evapotranspiration mapping, and hybrid SARIMA ANN approaches for reservoir inflow forecasting, achieving significant improvements in predictive accuracy, often exceeding 90 percent, lead time extension up to several days ahead, and computational efficiency. Key applications include real time flood and drought risk assessment, dynamic reservoir operation and spillway control, precision microclimate management in greenhouses through reinforcement learning, urban agriculture automation via weather typing and soil moisture analytics, and multi objective optimization of the water energy food nexus under climate change scenarios. The integration of GeoAI methods with remote sensing also enables large scale mapping of soil erosion susceptibility and groundwater vulnerability zones, providing decision support for sustainable land and water conservation planning. Collectively, these contributions demonstrate that big data, combined with advanced AI techniques, can transform traditional hydrological modelling into adaptive, data driven frameworks that support resilient, efficient, and equitable water resource management across scales and sectors.

The digital transformation of water resource management in Malaysia, according to [87], relies on multi layered integration of AI, ML, and IoT to address leakage, flooding, climate uncertainty, and increasing urbanization. Specific applications include the use of real time sensors to monitor pressure, flow, pH, turbidity, and chemical parameters, while the data are processed using ANN and Bayesian network algorithms for rapid detection of leaks, pipeline breaks, and anomalies. Smart SCADA units with IoT interfaces enable automatic control and notification of network failures, while digital flood alarm tools use AI enhanced precipitation forecasting, including XGBoost, SVM, and RF, for local flood risk assessment and integration with GIS systems for population warning. Predictive control techniques for biological treatment plants using ML are also discussed, where the Aquasuite PURE software predicts loads and oxygen and chemical requirements for optimal operation. The study also covers the use of LSTM and BLSTM in networks for dam flow and inflow prediction, as well as rainfall time series forecasting. Smart metering systems support early loss detection and high accuracy measurement of non produced water, improving payment security and consumer satisfaction. Finally, the study highlights key barriers to full digital maturity, including cost, skills gaps, fragmented data structures, and cybersecurity issues, and proposes the formation of a unified digital strategy that emphasizes business value, adaptability, and transparency.

The system presented in [88] is an integrated water resource management platform that combines IoT and AI technologies for monitoring, forecasting, and optimal allocation in urban and rural environments. The core architecture includes sensors that measure flow, pressure, level, quality, and soil moisture in agricultural applications, and these are deployed in tanks, distribution networks, pipelines, and irrigation systems. Data collection is carried out using NB IoT, LoRaWAN, and 5G, supporting low energy consumption and long communication range, while data are transmitted to a cloud based infrastructure using encrypted communication. There, the data are analyzed in real time using ML algorithms such as RF, LSTM, decision trees, and ARIMA for demand forecasting, leak detection, and pollution detection, and for automating irrigation in agricultural settings based on water availability and weather data. In addition, the system supports a mobile application and a web dashboard for real time monitoring, notifications, and remote control, while strong security measures are included, such as encryption, authentication, cloud firewalls, and anomaly detection for attacks, to preserve integrity and privacy. The applications include deployment in distribution networks, consumption forecasting, water saving in irrigation, early failure prediction, and preventive maintenance, promoting sustainable and energy efficient infrastructure operation in both urban and rural contexts.

Recently, a comprehensive AI and IoT-based optimization framework for smart water resource management was presented in [89], combining ensemble learning algorithms, including XGBoost and LightGBM, hybrid AI models such as an XGBoost Autoencoder, and meta-heuristic feature selection techniques, including GA, PSO, and SA, for leak detection and irrigation scheduling. The system leverages IoT sensors for flow, pressure, soil moisture, temperature, and humidity, which communicate through LoRaWAN, Wi Fi, and cellular networks with a cloud infrastructure for real-time analysis. The architecture includes predictive modelling with XGBoost for irrigation and an Autoencoder for leak detection, supported by a decision fusion mechanism and automated actuation for dynamic adjustment of irrigation levels and immediate stoppage of leaks. Advanced model optimization techniques, including structured pruning, quantization, knowledge distillation, and split computing between cloud and edge devices, are applied to reduce computational cost and energy consumption. Experimental results on real data from five cities in Saudi Arabia achieve an AUC-ROC of 0.992 for leak detection, an RMSE of 0.227 h for irrigation scheduling, an overall accuracy of 94.8 percent, a precision of 89.0 percent, a recall of 95.2 percent, an F1 score of 0.92, and an inference speed of 0.003 ms per sample. However, quantization increased the model size by 13.02 percent, indicating a trade-off that requires further optimization. The system was developed on NVIDIA Jetson Xavier AGX edge devices and supports dynamic retraining to adapt to changing environmental conditions, providing a scalable and computationally efficient solution for intelligent water resource management.