Abstract

The proliferation of mobile devices has driven significant growth in adaptive mobile applications (AMAs) that dynamically adjust their behavior based on contextual changes. While existing research has extensively studied individual adaptive systems, limited attention has been given to cooperative adaptation—where multiple AMAs coordinate their adaptive behaviors within shared mobile ecosystems. This systematic literature review addresses this research gap by analyzing 95 peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2025 to characterize the current state of cooperative adaptation in mobile applications. Following established systematic review protocols, we searched six academic databases and applied rigorous inclusion/exclusion criteria to identify relevant studies. Our analysis reveals eight critical dimensions of cooperative adaptation: Monitor–Analyze–Plan–Execute–Knowledge (MAPE-K) structure, application domain, adaptation goals, context management, adaptation triggers, aspect considerations, coordination mechanisms, and cooperation levels. The findings indicate that 63.2% of studies demonstrate some form of cooperative behavior, ranging from basic context sharing to sophisticated conflict resolution mechanisms. However, only 7.4% of studies explicitly address high-level cooperative adaptation involving global goal optimization or comprehensive conflict resolution. Energy efficiency (21.1%) and usability (33.7%) emerge as the most frequently addressed adaptation goals, with Android platforms dominating the research landscape (36.8%). The review identifies significant gaps in comprehensive lifecycle support, standardized evaluation methodologies, and theoretical frameworks for multi-application cooperation. These findings establish a foundation for advancing research in cooperative adaptive mobile systems and provide a classification framework to guide future investigations in this emerging domain.

1. Introduction

The proliferation of personal handheld devices has triggered the upsurge in the manufacturing of software for any and every possible personal utility. Mobile applications are software applications that can be executed (run) on a mobile platform (i.e., a handheld commercial off-the-shelf computing platform, with or without wireless connectivity) [1].

A notable characteristic of modern mobile applications is their capacity to be context-aware [2]. This is a significant advancement over traditional software, which typically operates in a static environment. Context-awareness refers to an application’s ability to perceive and respond to changes in its surroundings. This is achieved by utilizing various sensors and data sources on a mobile device, such as the Global Positioning System (GPS), accelerometer, gyroscope, microphone, and camera [2]. Hence, an increasing number of software providers are engaged in developing types of self-adaptive software that leverage their capacity to be configurable with minimum human intervention to gain a competitive advantage.

An adaptive mobile system/application is a software application that can be executed (run) on a mobile platform and has the capacity to adapt itself and its operational context. A mobile device, such as a mobile phone, can be considered an ecosystem of different mobile applications. These applications may have different purposes, developers, interaction mechanisms with the users, security requirements, sensors they need to access, etc. Similarly, a mobile device and its surrounding context can be a running platform for a diverse set of adaptive mobile applications with different adaptation goals, dimensions, and mechanisms. However, as mobile devices increasingly host multiple context-aware applications simultaneously, the independent adaptation strategies of individual apps can lead to resource conflicts and a suboptimal system-wide performance, motivating the need for cooperative adaptation mechanisms. This setup gives the opportunity for different adaptive mobile applications (AMAs) to coordinate and cooperate in their adaptation mechanisms. Cooperative adaptation is the capability of adaptive systems to coordinate their adaptation mechanisms and effects by affording context interference management, knowledge sharing, and complementary adaptation.

Even though there are numerous works that deal with adaptive systems in the context of mobile applications and a number of systematic literature reviews (SLRs) that have been published on the topic [3,4,5], there is a dearth of published literature that incorporates the cooperativeness dimension to characterize adaptive mobile applications. This review aims to identify, evaluate, and synthesize reported knowledge about approaches to building adaptive mobile applications by focusing on cooperative adaptation. This can contribute to accurately identifying the basic requirement of cooperative adaptive mobile applications.

This article is organized as follows: Section 2 introduces and elaborates on the concept of cooperative adaptation. Section 3 delineates the systematic methodology employed in conducting this review. The findings and associated discussions derived from the review are presented in Section 4. Section 5 addresses identified threats to validity and outlines corresponding mitigation strategies. Related works pertinent to this systematic literature review are examined in Section 6. Finally, Section 7 provides conclusions and proposes recommendations for future research.

2. Background

Self-adaptive software modifies its own behavior in response to changes in its operating environment. The operating environment can be an end-user input, external hardware devices, and sensors or program instrumentation [6]. Context-awareness and the ability to adapt autonomously has informed many mobile applications. In essence, AMAs strive to provide the best possible experience by dynamically changing to the user’s environment and device attributes.

Mobile applications are made up of binary executable files that are downloaded and stored locally on the user’s device [7]. The applications are distributed through app stores or mobile device vendors. Developers must write the source code (in a human-readable format) and produce extra materials, such pictures, audio clips, and different OS-specific declarations, in order to produce native application files. The source code is compiled (and occasionally linked) using tools supplied by the OS vendor to produce an executable in binary form that can be packed with the other resources and prepared for distribution [7]. A user initiates the installation process for a number N of apps and launches the apps according to the user’s desired usage settings.

We can define AMAs by adopting the definition put forward by the authors in [8]. Adaptive mobile applications modify their own behavior in response to changes in their operating environment that includes a user profile, end-user input, hardware, and sensors residing both on the host mobile device and external system. Self-adaptation can occur in any component of a mobile system, such as the application itself, the backend, or a smart object, and it can be employed at various stages of the computing system’s technology stack, including the hardware, platform, and business logic levels [4].

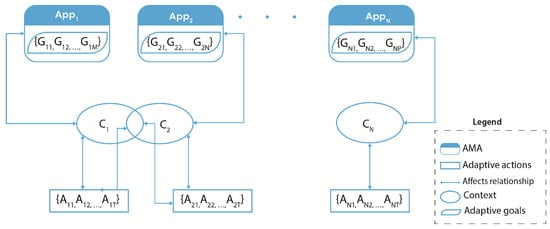

AMAs that are deployed on the same operating platform systems can occupy the same logical, physical, or computational space. This is illustrated in Figure 1. An adaptive software application designed by developers has a functionality that provides value to the user, a set of adaptation goals that set the agenda for adaptive actions, a unique knowledge base that facilitates adaptation, a scope of observed context, and clearly defined adaptive actions.

Figure 1.

Ecosystem of adaptive mobile applications.

In the context of an ecosystem of AMAs there can be N number of AMAs (App1, App2, …, AppN) deployed on the same device or a dedicated platform and catering usually to a single user. App1 can have a set of M adaptive goals G11, G12, …, G1M. Adaptive goals can include enhancing usability or optimizing energy. The adaptive application should observe a scoped context space C1 that is required to fulfill the adaptive goals. For example, a mobile application that aims to sustain energy conservation should observe the battery levels of the mobile device and the current profile of the user (such as the distance from a charging station). This information is organized and stored in a unique knowledge base accessible to App1. An inference engine that is core to the adaptivity of the mobile applications uses the inputs from the knowledge base and applies a possible number of T adaptive actions A11, A12, …, A1T based on adaptivity rules defined in the design stage of the mobile application development. It should also be noted that the adaptive rules can be dynamic and learned during the runtime phase of the application. The adaptive actions affect the behavior of the application that is itself in the domain of C1. A simple example could be after observing the battery of the mobile device reaching critical levels, App1 switching to a less energy-intensive profile. The profile could load a less graphically elaborate user interface or dim the light of the mobile device so that the battery can run longer. This aforementioned scenario is true for other apps, i.e., App2, App3, …, AppN.

The above setup provides an opportunity for cooperative mobile adaptation. App1 and App2 can share selective information from their knowledge bases K1 and K2, respectively. Revisiting the above example detailed by Figure 1, we can observe that there is a potential for context overlap. App1 and App2 observe an intersection of context space. They can also affect the delineated context space. If App2 also requires monitoring ambient light levels, it may query K1 of App1 rather than accessing the mobile device’s light sensor, thereby potentially reducing energy consumption. The dimming of light action proposed by App1 can also make App2 less visible to the user. Hence, App1 can enact adaptations that are optimal considering the user’s use of App2 rather than only being dictated by its own adaptation goal.

Cooperation in adaptive mobile systems involves mobile applications assisting each other in fulfilling their adaptive goals. Three facets of cooperation include context interference management, collaborative learning and knowledge sharing, and complementary adaptation. Context interference management aims to mitigate the negative effects of context changes from one application’s actions on another. It also involves identifying and capturing knowledge about common adaptation concerns to maintain and enhance the shared knowledge base. Complementary adaptation involves proactive contributions from one application to the overall system’s adaptation goals.

3. Materials and Methods

The SLR of self-adaptive mobile applications proposed in this paper was carried out using the method described by Kitchenham [9], which specifies guidelines for conducting SLRs in the software engineering field to guide researchers in the evaluation and interpretation of all available research publications concerning their research questions and objectives. This method suggests three key stages for the systematic review process. The review begins with planning; the goal of this step is to create a search technique for the review. The second step focuses on the review’s execution, which involves carrying out the search procedure outlined in the previous phase. The third phase concludes with the review report, which presents all of the results from the preceding phases.

3.1. SLR Research Questions

The research questions for this SLR are systematically derived through a three-stage iterative process in accordance with the goal–question–metric paradigm based on the recommendations to systematically formulate research questions in [10].

In the first stage, we identified the overarching research goals through a gap analysis using 15 seminal papers in the area of self-adaptive mobile applications. The analysis of the existing systematic literature reviews indicated that no comprehensive SLR addresses cooperative adaptation in mobile environments.

The main goal of this SLR is as follows:

“To understand the current state of adaptive mobile applications and identify dimensions relevant to cooperative adaptation.”

The main goal was decomposed into four specific sub-goals (G):

G1: To take stock of the current status and issues concerning the development of AMAs.

G2: To identify dimensions of adaptability for AMAs. The dimensions are examined according to their impact on cooperative adaptation.

G3: To identify the characteristics of AMAs that are related to cooperative adaptation.

G4: To propose a classification framework based on dimensions relevant to cooperative adaptation.

Following the guidelines in [10], we derived the research questions using a structured taxonomy. This resulted in identifying the following overarching research questions (Qs):

Q1: What is the state of the art in AMAs? (Maps to G1).

Q2: What are the dimensions of adaptability for AMAs that are related to cooperative adaptation? (Maps to G2 and G3).

We decomposed Q1 and Q2 into answerable components using the SLR methodology [10] that recommends breaking up generalized questions to specific sub-questions. Moreover, the publication questions are used to assess the research field’s maturity and trends.

For the purpose of the SLR the more immediate research questions (RQs) are as follows:

RQ1: What kind of approaches are presented in relation to AMAs? (Derived from Q1, addresses G1).

RQ2: What are the goals of adaptation? (Derived from Q1 and Q2, addresses G2).

RQ3: Which stages of the software development process are supported by the works? (Derived from Q1, addresses G1 and G4).

RQ4: What is the level of coordinated or cooperative adaptation considered? (Derived from Q2, addresses G3).

RQ5: What proportion of approaches are connected to specific mobile application platforms? (Derived from Q1, addresses G1).

RQ6: What aspects of the dimensions of adaptation put forward by the study can be applied to cooperative adaptation? (Derived from Q2, addresses G2 and G4). This is the synthesis question that maps the adaptation dimension to cooperation potential.

The publication questions (PQs) are as follows:

PQ1: What are the main publication venues? (Derived from Q1, addresses G1).

PQ2: How has the quantity of papers evolved across time? (Derived from Q1, addresses G1).

3.2. Search Strategy

A methodological search strategy is beneficial in warranting the completeness of relevant article identification in an SLR. Completeness is a critical issue in SLRs in the software engineering domain, as recommended in [10]. A comprehensive search strategy was implemented to ensure the thorough coverage of the relevant literature, incorporating three complementary approaches: (1) automated database searches, (2) manual journal and conference proceedings searches, (3) backward snowballing of reference lists. This resulted in a set of candidate studies.

3.2.1. Automated Search

We employed a keyword search for the following online databases: Google Scholar, IEEEXplore, ACM Digital Library, ScienceDirect, Arxiv, and IET Digital Library, based on the evidence put forward in [9,10].

The search string formulation followed the basic concepts outlined in the research questions. We adhered to the following steps in composing the search strings:

- (i)

- Identify important terms or concepts used in the RQs.

- (ii)

- Identify terms used in the sample set of papers referring to self-adapting systems, autonomous systems, mobile systems, etc.

- (iii)

- Identify synonyms, abbreviations, and alternative spellings of terms found in i and ii.

- (iv)

- Define the search string by joining the synonym terms with the logical operator OR and the set of key terms with AND.

We constructed the final search string after iterations and analyses of findings on a pilot sample. It should be noted that we applied a generic search string to capture as much of the relevant literature as possible. Since the defined data sources include search engines, the strings will be entered sequentially with the combinations of them and adapted to each search engine for the specific database as appropriate. The generic search strings used for the six databases, last run on 24 April 2025, are given below:

- (1).

- Google: (“Adaptive” OR “Autonomous” OR “Self-adaptive” OR “Self-organizing” OR “Self-optimizing”) AND (Mobile OR Android OR ios) AND (“System” OR “Systems” OR “Application” OR “Applications” OR “app” OR “apps”).

- (2).

- IEEEXplore: (“Adaptive” OR “Autonomous” OR “Self-adaptive” OR “Self-organiz*” OR “Self-optimi*”) AND (Mobile OR Android OR ios) AND (“System*” OR “Applicat*” OR “app*”)

- (3).

- ACM Digital Library: (“Adaptive” OR “Autonomous” OR “Self-adaptive” OR “Self-organizing” OR “Self-optimizing”) AND (Mobile OR Android OR ios) AND (“System” OR “Systems” OR “Application” OR “Applications” OR “app” OR “apps”).

- (4).

- ScienceDirect: (Adaptiv* OR Autonomous OR “Self-adaptiv*” OR “Self-organizing” OR “Self-optimizing”) AND (Mobile OR Android OR iOS) AND (System* OR Application* OR app*).

- (5).

- Arxiv: “Adaptive”|“Autonomous”|“Self-adaptive”|“Self-organizing”|“Self-optimizing”) + (Mobile|Android|ios) + (“System”|“Systems”|“Application”|“Applications”|“app”|“apps”).

- (6).

- IET Digital Library: (“Adaptive” OR “Autonomous” OR “Self-adaptive” OR “Self-organizing” OR “Self-optimizing”) AND (Mobile OR Android OR ios) AND (“System” OR “Systems” OR “Application” OR “Applications” OR “app” OR “apps”).

3.2.2. Manual Search

An additional manual search was conducted for outlets specializing in the publication of studies related to self-adapting (autonomous) systems and mobile systems. The pilot phase of the literature review identified the Journal of Complex Adaptive Systems (JCAS) and the International Symposium on Software Engineering for Adaptive and Self-Managing Systems (SEAMS) and the International Conference of Software Engineering (ICSE) as potential outlets for the publication of relevant articles. This enabled the researchers to review papers that have similar dimensions to AMAs (e.g., the Internet of Things (IoT), Cyber–Physical systems (CPS)) but are not explicitly stated as such.

3.3. Study Selection

The selection of relevant studies for this SLR was conducted through a four-stage screening process. The authors of this paper made selections according to the title (first stage), abstract (second stage), conclusion (third stage), and full text (fourth stage). The need to consider the conclusion section of an article is guided by [9], who observed that many papers in the SE field are characterized by crudely written abstracts and recommended additionally looking at the conclusion section. A paper was selected if it satisfied one or more of the inclusion criteria and it was rejected if it satisfied one or more of the exclusion criteria. Table 1 details the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were systematically derived from the research questions. The identified criteria were validated by two external systematic review experts on 10 selected papers, achieving 94% agreement. We designed the inclusion criteria to be inclusive rather than restrictive to ensure comprehensive coverage.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for candidate studies.

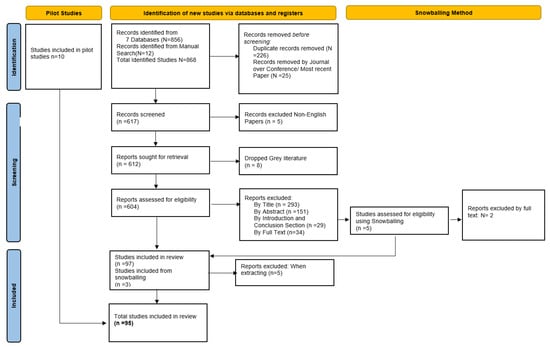

The initial search across 6 databases yielded 856 potentially relevant studies. The manual search also provided 12 additional papers. After removing 226 duplicates, 642 records remained. The prioritization of journal articles over conference proceedings and the selection of the most recent publications discussing the same study resulted in the exclusion of 25 studies. Further screening involved the removal of 5 non-English papers, 8 theses and dissertations, keynote speeches, and poster papers. Title screening led to the exclusion of 293 studies, leaving 311 records for abstract review.

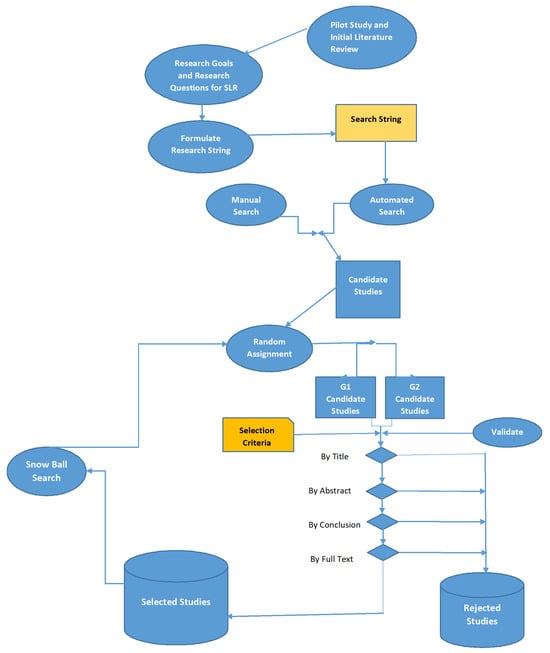

Abstract screening resulted in the exclusion of an additional 151 studies based on their irrelevance to the research question. The subsequent review of introductions and conclusions further reduced the pool by 29 studies. Finally, a full text review of the remaining 131 articles led to the exclusion of 34 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. We considered an additional 5 studies as a result of forward and backward snowballing and selected 3 studies that were relevant to our research goals. This resulted in 100 papers being used for data extraction. During the data extraction phase, we dropped 5 studies because they were either low-quality papers or did not treat adaptation adequately. Most of the dropped papers considered adaptation at the business or logical level, as in the case of [11], where the adaptation was set on fixed rules of learner’s profiles rather than continuous context monitoring and runtime modification. The selection process ultimately resulted in the final selection of 95 studies that were included in the systematic review. The reasons for exclusion at each stage are visually represented in the PRISMA flow diagram given in Figure A1 in Appendix A.2. The candidate studies from the screening stage were randomly assigned to two teams of researchers with two members each. Each individual in the group independently applied the selection process following the selection criteria delineated in Table 1. An agreement level of Fleiss’ Kappa statistic Kappa = 0.92 validated the study selection process [12]. Figure 2 illustrates the search and selection protocol used in the SLR.

Figure 2.

The selection process in this SLR.

3.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

A systematic data extraction procedure was employed to retrieve relevant information from the included papers, ensuring alignment with the research questions of this systematic review. The pilot analysis of selected papers provided insight into the relevant data to be extracted from each paper. The data extraction process is guided by the format delineated in Table A1 in Appendix A.1. An external reviewer validated the linkage between the research questions and the data extraction format.

Two researchers extracted data from the selected papers, with a third researcher mediating in case of significant discrepancies. Data extraction is an iterative process, with new dimensions emerging with each iteration and discussion. The final extracted data was consolidated for synthesis.

The extracted data was combined and evaluated to provide answers to the research questions introduced in Section 3.1. A thematic and narrative analysis is used to identify the trends, approaches, and gaps in the subject of developing AMAs. Emerging concepts are organized to determine the modeling dimensions of cooperative AMAs. A quantitative descriptive analysis is also provided as needed to illustrate proportions and trends.

4. Results

In this section, we present and summarize the results of the review. Section 4.1 provides an overview of the selected papers, Section 4.2 addresses the research questions related to the publications, while Section 4.3 discusses the remaining research questions and articulates a response for each research question.

4.1. Overview of Selected Papers

Table 2 presents a breakdown of the 95 publications categorized into three types: book chapters, conference papers, and journal articles. Conference papers are the most frequent type of publication, followed by journal articles, with book chapters being the least common.

Table 2.

Distribution of publication type.

Most evaluation mechanisms of the studies in this SLR are based on experiments, with the most common combination being experiments and prototypes. Few studies dealing with evaluating applications are based on adaptive mobile applications. A notable portion of studies lack explicit evaluation methods. There were no case studies of multiple goal adaptation-based studies. The data in Table 3 shows a strong emphasis on experimental and prototyping evaluations, with the limited use of other methodologies like case studies or expert validation.

Table 3.

Distribution of evaluation mechanisms reported.

4.2. Publication Questions

4.2.1. PQ2: How Has the Quantity of Papers Evolved Across Time?

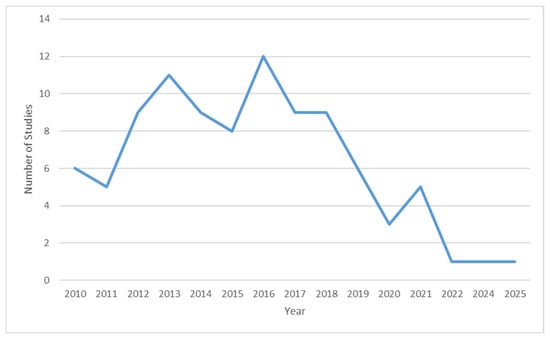

We tallied the distribution of 95 publications across various years, ranging from 2010 to March 2025. The data reveals fluctuations in publication output over time, with a noticeable peak in 2016 and a general decline in more recent years, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Time trend of number of studies.

For a more organized comparison, we divided the period from 2010 to 2025 into three-year ranges, presented in Table 4. There is a steady increase in publications in the year range 2010–2018, where the highest output is observed in the period 2016–2018 (30 papers). However, there is a sharp decline in papers concerning AMAs in the 2019–2025 range. The peak productivity years coincide with the research interest regarding Service-Oriented Architecture (SOA), which involved offloading some functionalities of mobile applications. A closer look reveals that self-adaptation practices like parameter-based adaptations have been standardized and there has been a focus on adaptations that provide robust functionality in recent years (discussed more in Section 4.3.3. We also have to factor in the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted research activities globally and can explain the sharp decline in recent years.

Table 4.

Year range and number of publications.

The analysis reveals a distinct pattern of publication output, with a peak in the mid-2010s followed by a substantial decline. This trend likely reflects a combination of factors, including research activity, external influences, and potential changes in research priorities.

4.2.2. PQ1: What Are the Main Publication Venues?

The SLR revealed that out of the 95 papers, 84 papers are published in different venues. Only five outlets published two or more studies related to AMAs, as outlined in Table 5. A total of 13 papers appeared in IEEE journals or conferences. This wide distribution, spanning the user interface (UI), health, and education domains suggests a lack of a central, authoritative venue dedicated specifically to AMAs. The absence of such a venue hinders organized knowledge dissemination and potential collaboration on common adaptation challenges across various application types. We have observed that in recent years, there has been a notable increase in publications within venues specializing in artificial intelligence and machine learning, reflecting the growing scholarly interest and research momentum in these domains.

Table 5.

Venues with two or more publications.

4.3. Research Questions

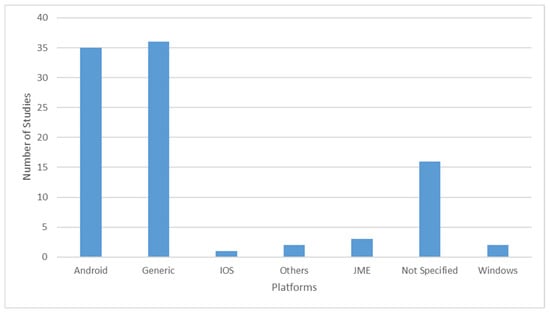

4.3.1. RQ5: What Proportion of Approaches Are Connected to Specific Mobile Application Platforms?

Android is the most dominant platform considered in the review, accounting for 36.8% of all papers, as shown in Figure 4. The high prevalence of Android aligns with its market dominance (70%) in mobile ecosystems [13]. The “Generic” category includes platform-agnostic approaches (including web-based mobile applications) or those not tied to a specific OS and are tallied as the most frequent in the data set. The iPhone Operating System (IOS), Windows, and Java Platform, Micro Edition (JME) were minor platforms, only accounting for 5.3% percent of the considered studies. JME is associated with legacy mobile applications, which are common in older embedded systems. However, the surprising underrepresentation of IOS may be caused by its characteristic of being a closed ecosystem, limiting open research data that is important for studies on adaptive systems that require access to computing resources. A significant proportion of the studies (n = 16, 16.8%) failed to specify the target platform for their proposed approach, despite the methodological necessity of platform-dependent implementation.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution of platforms in selected studies.

4.3.2. RQ1: What Kind of Approaches Are Presented in Relation to Adaptive Mobile Applications?

The 95 studies can be categorized into six distinct methodological approaches regarding the development of self-adaptive mobile systems (Table 6). The distribution reveals two dominant paradigms, architectural solutions and framework-based approaches, each representing 27.4% of the total studies (n = 26). Technique-oriented studies constitute the third largest category (16.8%, n = 16), followed by model-based (10.5%, n = 10) and system-level (9.5%, n = 9) approaches. Middleware solutions appear less frequently (7.4%, n = 7), while one study fails to clearly specify its methodological approach.

Table 6.

Approaches presented.

The current landscape of adaptive mobile computing research demonstrates some key characteristics in methodological approaches:

- (i)

- The field is predominantly characterized by framework-based and architectural approaches, which collectively account for the majority of research efforts. These approaches typically provide either

- Structural guidelines for system organization (architectures).

- Implementable templates with predefined behaviors (frameworks).

A significant secondary focus on algorithmic techniques exists, often manifested as optimization or adaptation procedures.

- (ii)

- While many studies propose conceptual foundations (26 frameworks, 26 architectures), only nine works progress to complete system implementations or functional applications, suggesting a potential gap between design and deployment. Middleware solutions (seven instances) predominantly address decentralized adaptation scenarios, reflecting the distributed nature of modern mobile ecosystems.

- (iii)

- Limited attention is given to comprehensive treatment spanning the full development lifecycle (design → modeling → architecture → implementation). Design patterns remain notably underrepresented (only two works), despite their potential for capturing reusable adaptation solutions.

4.3.3. RQ3: Which Stages of Software Development Process Are Supported by the Works?

We attempted to answer this research question through an analysis of research coverage across system development life cycles in the reviewed papers. A study is deemed to engage with a software development phase if it contributes solutions to phase-specific challenges or critically examines the conceptual dimensions of that phase in the context of AMAs. The considered phases are analysis, design, implementation, and runtime. It is necessary to qualify “runtime support” and “implementation support” in the context of AMAs. Runtime support pertains to the mechanisms and infrastructure that enable a self-adaptive system (SAS) to dynamically modify its behavior while it is actively executing. This includes managing the dynamic reconfiguration of the system’s components. On the other hand, implementation support deals with the tools that facilitate the development of SASs [14].

Table 7 shows the distribution of the 95 publications across various combinations of the four software development phases. The majority of publications cover combinations of two or more phases. Particularly, “Analysis, Design, Runtime” (16) and “Analysis, Design, Implementation, Runtime” (15) are among the most frequent categories, suggesting a significant focus on research that spans the entire software development lifecycle. Design-centric studies dominate the landscape, appearing in 92.6% of all combinations. Runtime adaptation is the second most addressed phase (53 studies, 55.8%). The most frequent combination is Analysis and Design (n = 19, 20%), representing conceptual/theoretical work. Full lifecycle coverage (Analysis, Design, Implementation, Runtime) appears in 15 studies (15.8%).

Table 7.

Phases supported.

Over one-third of studies (≥33%) omit the analysis phase in AMA development. Only 33 studies (out of the 95 examined) address the implementation phase, with even fewer providing tools or frameworks for practical deployment. There is also minimal focus on the testing and evaluation of adaptive behaviors. This can be a precursor for a lack of benchmarks for comparing adaptation strategies in mobile applications.

Table 8 presents findings from a cross-concern analysis of the selected studies. The analysis phase is notably underrepresented in research focusing on middleware and technique-oriented approaches. While the design phase is extensively addressed across studies, its integration with the implementation phase is frequently absent. Architectural approaches predominantly target early phases, with 9 out of 19 studies focusing on analysis and design. Framework-based approaches demonstrate strong coverage across the full software development lifecycle, accounting for 7 out of 15 studies. In contrast, technique-oriented approaches exhibit a dispersed focus, lacking specialization in specific phases. Notably, none of the studies proposing AMAs as systems comprehensively address the entire lifecycle, including runtime support or the combined phases of analysis, design, and implementation.

Table 8.

Phases supported by approach presented.

4.3.4. RQ2: What Are the Goals of Adaptation?

Table 9 categorizes the selected 95 papers based on the primary adaptation goals they address in the development of AMAs. The data set reveals a diverse range of adaptation goals, with a strong emphasis on “Usability,” “Energy Efficiency,” and “Robust Functionality.” Many publications also address combinations of goals, indicating a multifaceted approach to SAS design. Robust functionality is defined as the ability to provide different functional services to the user based on context. A real-world instance of robust functionality can be an app that switches to a real-time heart rate monitoring mode when the user is engaging in high-intensity exercise.

Table 9.

Goals of adaptation in selected studies.

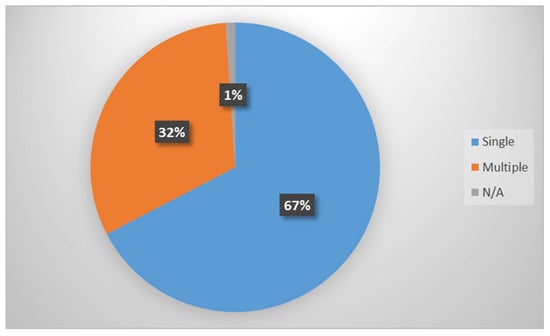

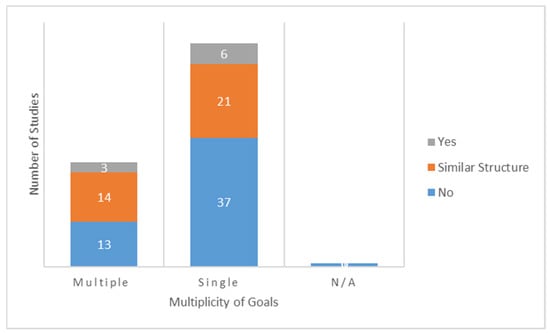

An analysis of the reviewed literature revealed a significant dimension pertaining to goal multiplicity, specifically whether individual studies addressed singular or multiple adaptation objectives. The majority of studies, exceeding two-thirds of the total corpus, focused on single adaptation goals. However, a discernible trend towards the consideration of multiple goal adaptation scenarios was observed. Notably, a paradigm shift occurred during the 2019–2021 period, wherein studies investigating multiple adaptation goals surpassed those examining single goals, representing 53.3% and 46.7% of the publications, respectively. This transition indicates a growing emphasis on multi-objective optimization within the field. Figure 5 portrays the overall distribution of single versus multiple goals in all the studies.

Figure 5.

Proportion of multiplicity of goals in studies.

Energy efficiency and performance optimization are the most paired goals among multiple goal adaptation studies. Security and usability, energy efficiency and resource optimization, and performance optimization and reliability are some of the paired goals that were explicitly treated by the studies. Energy efficiency is the concern that was most paired with other goals in the study (11/30), while robust functionality and usability are adaptation concerns that are gaining traction in multiple goal settings. The combination of security and usability has emerged as a notable trend in recent years.

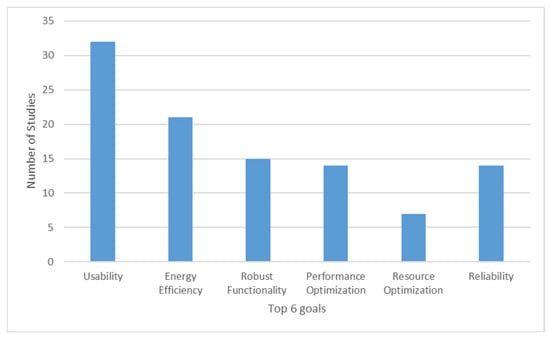

“Usability” stands out as the most frequently addressed goal (25 publications) in single-goal-oriented studies, while 32 works include usability as a goal in single and multiple goal settings. “Energy Efficiency” is another prominent goal, with 20 publications focusing on this either solely or in combination with other goals. “Robust Functionality” is also a common goal, with 14 publications focusing on this either solely or in combination with other goals.

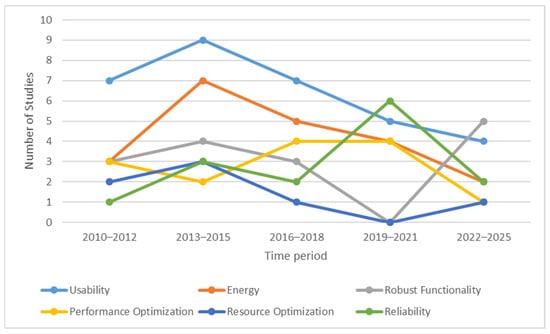

Figure 6 illustrates the frequency of the top six adaptation goals in both single and multiple goal settings in the study. Zooming in to the top six adaptation goals and analyzing the temporal trends yields a pattern, visualized in Figure 7. The figure illustrates the evidence that there is a surge in reliability in 2016–2021. We can also note that there is an increase in concern for robust functionality in the same period relating to advances in context-oriented services.

Figure 6.

Frequency distribution of top 6 goals considered.

Figure 7.

Time trend for top six goals.

4.3.5. RQ6: What Aspects of the Dimensions of Adaptation Put Forward by the Study Can Be Applied to Cooperative Adaptation?

Research question 6 analyses the findings from the 95 selected studies to identify and characterize the fundamental dimensions that distinguish cooperative adaptation from isolated, single-application adaptation in mobile ecosystems. Eight candidate dimensions are identified through concept clustering and discussions among the researchers. It should be noted that one of the identified dimensions (i.e., goals) is discussed in RQ2 in Section 4.3.4.

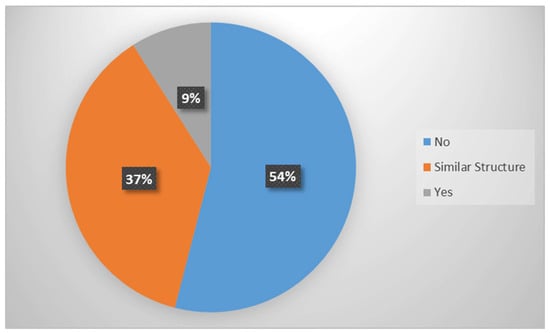

MAPE-K Structure Reported

The selected works in this SLR were analyzed to determine if there was an explicit Monitor, Analyze, Plan, Execute, Knowledge (MAPE-K) structure, the most widely used reference model for implementing SASs. Figure 8 illustrates the frequency distribution for the item.

Figure 8.

Proportion of existence of explicit MAPE-K structure.

As shown in Figure 8, less than 10% of studies explicitly defined a MAPE-K structure. More than half (53.6%) had no explicit structure and about 37% reported modules or structures that are similar to MAPE-K but did not explicitly correspond to each module in MAPE-K. There was one study [15] that attempted to extend MAPE.

Figure 9 shows that there is a significant increase (56.6%) in the proportion of multiple adaptation goal studies that openly employed either a similar or identical MAPE-K structure when compared with studies that only addressed single adaptation goals (42.2%). It is important to highlight that this concept presented the most significant challenge during data extraction, necessitating extensive deliberation among team members. This difficulty arose primarily due to the lack of explicit documentation regarding MAPE-K modules in the majority of the reviewed studies.

Figure 9.

Explicit MAPE-K structure alongside multiplicity of goals.

Domain

Table 10 presents the frequency distribution of primary application domains encountered within the surveyed literature pertaining to AMAs. A significant proportion of the analyzed studies, representing 60% of the total, exhibited domain-inert characteristics, indicating a lack of a specific domain focus. Among the domain-specific studies, education emerged as the most frequently addressed, followed by health and gaming. Notably, only one study adopted a multidisciplinary approach. Within the health domain, a predominant emphasis on usability was observed, accounting for 50% of the relevant studies. Similarly, in the education domain, usability constituted a substantial focus (40%), followed by robust functionality (20%). These findings suggest a potential benefit in promoting further research endeavors that are explicitly tailored to specific application domains.

Table 10.

Frequency distribution of major domains.

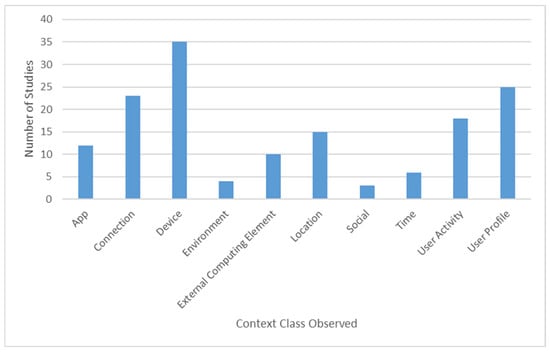

Context Observed

Table 11 provides a detailed breakdown of the types of contexts considered in the 95 studies related to AMAs.

Table 11.

Frequency of context observed in selected studies.

The internal states and behaviors of applications are designated as app-related contexts. App-related context includes the current state of the application (foreground/background, active/inactive), its settings and configurations, its structure, its usage history (frequency, duration), its dependencies (connected services, Application Programming Interface (API)), and its permissions (access to sensors, storage, and the network). The following are examples of external computing elements: server availability and latency; cloud/edge computing services; and nearby gadgets (the IoT, wearables, and other smartphones) that affect app behavior [4]. User profile context pertains to static or semi-static user attributes, including demographic data (age, gender, language) preferences (theme, notification settings), account details (subscription tier, login status), and historical behavior (frequently used features) [16]. User activity context captures dynamic user actions and behavior, such as physical activity (walking, driving, stationary), interaction patterns (swipes, clicks, voice commands), temporal habits (time of usage, session length), and social activity (messaging, sharing content) [17]. Device context relates to hardware and system-level conditions including device type, battery level, storage, memory, sensor status, and data. Connection refers to network-related conditions like signal strength, network type, latency and stability, etc. [18] The category “General” denotes studies employing a broad, non-specific approach to context, lacking the explicit definition or categorization of contextual parameters.

Contextual information is systematically organized into distinct context classes, facilitating structured analysis and processing. For instance, device-specific attributes such as battery level, Random Access Memory (RAM) capacity, and Central Processing Unit (CPU) utilization are appropriately categorized under the device context class. Furthermore, a hierarchical organization of context into levels offers opportunities for context consolidation and abstraction. However, the classification of contextual elements is not always unambiguous. Consider, for example, energy level, which can be initially perceived as a property of the mobile device and thus assigned to the device context class. Nonetheless, the location context can significantly modulate the device’s power state. Specifically, a device situated in proximity to a power charging facility should be assigned to a distinct power state compared with a device located remotely, underscoring the dynamic interplay between different context classes.

Figure 10 further illustrates the prevalence of context class type in the selected studies (in both single and multiple context combinations). The quantitative analysis reveals a pronounced emphasis on technological infrastructure, with device and connection emerging as the most prevalent research contexts, appearing in 36.8% and 31.6% of studies, respectively. Concurrently, user profile (22.1%) and user activity (17.9%) represent significant but secondary themes, reflecting a complementary interest in human-centric factors, such as behavioral analytics, personalized systems, and user interaction patterns. Environment emerged as an understudied context in relation to AMAs. The combination of connection and device contexts represents the most prevalent pairing, observed in 15 studies (15.8%), underscoring a significant dependence on network- and device-related information within the analyzed literature.

Figure 10.

Frequency distribution of context observed in selected studies.

We further analyzed the studied context in the selected papers of this SLR with the aspects of goals, domain, and time periods. User activity and user profile are the most researched contexts in multiple domains including education and health. Across temporal periods, earlier studies predominantly focused on isolated contextual factors, such as device and connection attributes. In contrast, more recent investigations increasingly integrate three or more factors, including device, location, and user activity. Additionally, a notable shift towards user-centric contexts has emerged in recent years, emphasizing factors such as user profile and activity. Table 12 is a matrix presenting the relationship between the top six goals and associated contexts observed in the AMA studies.

Table 12.

Relationship between top 6 goals and context observed in selected studies.

User profile (15), user activity (11), and location (6) dominate usability research, reflecting a focus on human factors, personalized interfaces, and spatial interaction design. Device (7) appears within studies investigating usability moderately, suggesting usability evaluations of hardware interfaces (e.g., mobile devices). The goal of energy efficiency is heavily skewed toward device (16) and connection (12) contexts. Concerning the goal of robust functionality, the focus on the contexts of user profile (8) and activity (7) suggest that functional evaluations account for user behavior variability. Both technical-based adaptation goals (performance optimization, resource optimization) link almost entirely to connection and device contexts, emphasizing network and computational efficiency.

The data reveals a wide range of contextual factors influencing adaptation in mobile applications, with a strong emphasis on “connection” and “device” information, both independently and in combination. The data also shows a strong trend towards combining multiple context types within the studies. This hints at concerns of overlapping contexts and context consolidation, from simple context information sharing to context consolidation from two different contexts observed by two different applications.

Aspects

Aspect is a property that is related to adaptation action and encapsulates the action and space of adaptation according to the value to the user. It answers the following question: what changes and how do they change due to adaptation? It is a term adopted from the definition of aspect in the computer science and software engineering fields that refers to cross-cutting concerns [19] but is refined for use in this study. It arose from the challenges that the researchers faced with regard to differentiating the place and mechanisms of adaptation and the need to find a concept that facilitates abstraction among different AMAs. For example, an app that reacts to the changes in a context where there is a change in the lighting condition of the app usage can affect how the user uses the SAS by changing the UI aspect, introducing new layout and UI elements. The class app behavior aspect corresponds to aspects related to how a program behaves, including its inputs, outputs, processes, and the structural elements of the app. It is more prevalent in adaptive offloading where the structure of a mobile application changes considering both where it deploys and what components it incorporates. The type of services and the procedures associated with changing them in providing a value to a user are encapsulated as the functionality aspect. Quality of Service (QoS) is a non-functional aspect that relates to the non-functional requirements of the adaptive mobile system relevant to the user.

Table 13 enumerates the specific studies corresponding to each defined aspect or combination of aspects identified within the 95 selected studies, detailing their association with adaptation actions in adaptive mobile applications (AMAs). Structure is the most studied aspect (30.7%), reflecting the emphasis on architectural adaptability. Content (18.7%), UI (16.0%), and functionality (10.7%) are the next most common aspects addressed by the studies. Content and UI are the most paired aspects in the studies.

Table 13.

Distribution of studies on defined aspects for cooperative adaptation.

The referenced studies provide varied technical approaches to aspect dimensions. Ali et al. emphasize the MAPE-K structure, proposing a feedback loop where AMAs monitor context (e.g., battery levels or user inputs) and execute adaptations via predefined rules, focusing on self-contained adaptation within a single application [3]. Similarly, Grua et al. explored context-aware adaptation, using sensors like GPS to adjust UI elements, prioritizing user-centric goals like usability [4]. These studies highlight structured, rule-based technical frameworks for adaptation, often implemented in the design or runtime phase, with a focus on individual app performance rather than inter-app cooperation. Their technical features include sensor data integration and rule-based decision-making, typically implemented in Android environments due to its open architecture.

The aspects detailed in Table 13 can be grouped into more abstract aspect classes (shown in Table 14) that provide a more general view of aspect. For example, structure, content, and service composition aspects can be grouped into the aspect class “app behavior”. Table 15 provides the frequency of aspect classes considered in the reviewed papers (there can be multiple aspect classes for each study).

Table 14.

Aspect types categorized in aspect classes.

Table 15.

Frequency of aspect classes.

The primary research focus of most reviewed studies is on app behavior. Functionality that refers to feature implementation and service ranked second while the user design and experience-related aspect class (UI) is significant in the reviewed papers. Security is an emerging but still under-researched aspect class. Looking across the time period delineated in the study, app behavior dominated as the aspect class most studied by the papers. Functionality gained more attention in the period 2019–2025. Notably, conceptual overlaps exist between aspects—for instance, service provision can also be interpreted as a subset of app behavior, particularly when examining runtime component binding to deliver user-facing services.

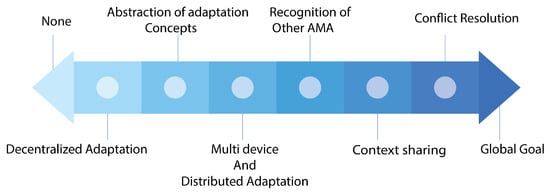

4.3.6. RQ4: What Is the Level of Coordinated or Cooperative Adaptation Considered?

In this SLR we attempted to analyze the presence of cooperative adaptive behavior or the treatment of the concept at any level in the selected studies as per the definition of cooperative adaptation as operationalized in Section 2. The researchers discovered a coarse range of cooperative adaptation that is classified in a category with an increasing level of cooperative adaptation, as illustrated in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Levels of cooperative adaptation in AMAs.

The studies labeled “None” for the entry are studies with approaches which did not report any cooperation or coordination within proposed app components or another adaptive app component. Decentralized adaptation refers to how individual components of MAPE-K are structured in an individual app, in line with the simple decentralized adaptation patterns put forward in [114]. It should be noted that even though the applications are structurally amenable to coordination there is little cooperation in the modules of the individual app itself. On the other hand, multi-device and distributed adaptation refer to different modules with reasoning and adaptive capabilities coordinating to form a consolidated service for a single app. The modules can also be deployed in different infrastructures. However, the coordination and cooperation are still within the individual AMA.

Studies categorized under the abstraction of adaptation concept constitute research contributions that formalize adaptive logic and propose architectural frameworks to facilitate cooperative adaptation mechanisms in AMAs. These works typically advance generalized models, patterns, or meta-architectures that transcend specific implementations, thereby enabling the systematic design of interoperable self-adaptive behaviors across the common mobile platform. There are studies that explicitly recognize or anticipate the presence and interaction of other AMAs in the same mobile ecosystem. However, they do not provide any mechanism for cooperation. The level of context sharing and management denotes the capability of two or more AMAs to share adaptive information. Conflict resolution involves a higher degree of cooperation than context sharing and employs the information to resolve the defined situation that results in adaptive interference. A global goal level is discovered in studies that recognize a common adaptation goal and employ approaches and techniques to ensure cooperation. Table 16 summarizes the cooperative adaptation levels in our selection of studies, along with associated studies and frequencies.

Table 16.

Distribution of level of cooperative adaptation.

Approximately 36.8% of the studies demonstrate no inter-system cooperation. Furthermore, 16.5% of the studies indicate an awareness of other SASs, while 6.3% of the studies involve some level of data-driven cooperation (i.e., context sharing). Only 3.2% involved approaches related to conflict resolution and another 4.2% proposed solutions to work on global adaptation goals. This validates the research gap that cooperative adaptation in mobile application is an under-researched area.

Among the salient primary studies, Refs. [24,61,78,92] are prominent for their contributions to conflict resolution, context sharing, and global goal levels. In the conflict resolution category, one study implements a mechanism where AMAs detect and resolve conflicting adaptations using a priority-based arbitration algorithm [61]. This technical feature relies on a centralized controller within the Android OS to enforce adaptation precedence, ensuring stability but requiring apps to register their adaptation goals in advance. Similarly, another approach addresses conflict resolution by employing a rule-based system to manage resource contention (e.g., CPU usage), using predefined conflict resolution policies stored in a local database [78]. Its technical simplicity ensures low latency but limits scalability in multi-app scenarios compared with more dynamic approaches.

In contrast, Refs. [24,92] represent higher cooperation levels. In the context sharing and management category, one approach enables AMAs to exchange context data (e.g., location or user activity) via a peer-to-peer protocol, implemented using Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) messaging for low-bandwidth communication [24]. This can allow AMAs to optimize resource use (e.g., sharing GPS data to reduce sensor calls) but introduces challenges in maintaining data consistency across apps, unlike the centralized control in [61]. Study Ref. [92], in the global goal category, implements a cooperative framework where AMAs align toward a shared objective, such as energy conservation across a device ecosystem. It uses a distributed optimization algorithm (e.g., a simplified genetic algorithm) to negotiate adaptations, requiring significant computational resources and inter-app trust mechanisms, contrasting with Ref. [78]’s simpler, local rule-based approach. While Ref. [92] achieves robust multi-app coordination, it incurs a higher overhead than Ref. [24]’s lightweight messaging, highlighting a trade-off between cooperation depth and system efficiency.

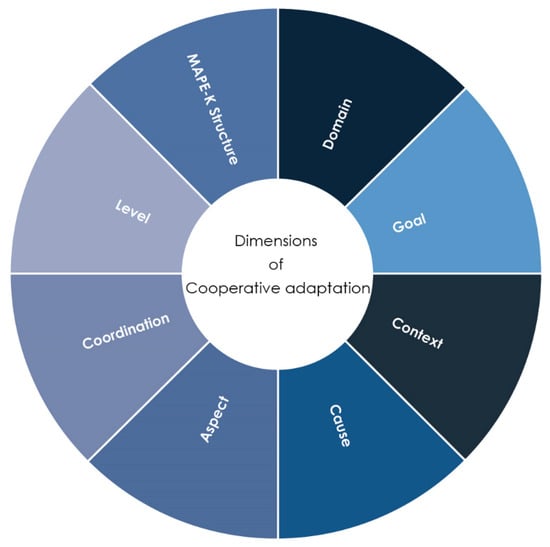

4.3.7. Dimensions of Cooperative Adaptation for Mobile Applications

The analysis and synthesis of the different areas of concerns about the selected studies revealed the following dimensions of cooperative adaptation in AMAs.

- (i)

- Structure of MAPE-K: A clearly defined MAPE-K structure for an adaptive mobile application can provide a modular architecture that defines the roles and scopes of cooperative adaptation in mobile adaptive systems. The separation of concerns that modularize adaptation logic can also be extended to cooperative adaptation delineating clearly the domains and levels of cooperative adaptation. On the contrary, a fixed MAPE-K structure may also inhibit the flexibility required for determining an emerging behavior for cooperative adaptation.

- (ii)

- Domain: The effectiveness of the architectural design of cooperative adaptation mechanisms within AMAs are potentially contingent upon the specific application domains for which these applications are developed. The adaptation goals are also shaped by the particular requirements of individual domains. More specifically for the case of cooperative adaptation, AMAs operating in the identical domains share more similar adaptation goals. A discernible interdependence exists among distinct application domains, wherein cooperative adaptation mechanisms can be facilitated through cross-domain synergies. Specifically, the outputs generated within one domain may serve as functional inputs for another, as exemplified by the integration of gaming paradigms (e.g., engagement analytics, interactive simulations) into educational technologies (e.g., adaptive learning platforms, gamified curricula). This bidirectional relationship underscores the potential for domain-transcendent adaptation strategies that leverage shared knowledge, resource optimization, and behavioral insights.

- (iii)

- Goals: Goals act as the primary drivers of cooperative adaptation, determining whether systems integrate tightly, negotiate resourcefully, or compete destructively. These goals exhibit several key dimensions that influence the mode and effectiveness of cooperation. Firstly, the explicit declaration versus the implicit inference of adaptation goals shapes the transparency and potential for alignment among agents. Secondly, the temporal characteristic of a goal, whether transient or persistent, dictates the duration and urgency of cooperative efforts. In cooperative scenarios, the priority assigned to individual and collective goals becomes a critical factor in decision-making. Furthermore, the static or dynamic nature of adaptation goals influences the need for the continuous negotiation and re-evaluation of cooperative strategies. The scope of goals, encompassing both individual and collective objectives, defines the boundaries of cooperative action. The granularity and expression of goals, whether high-level or low-level, coarse-grained or fine-grained, impact the mechanisms for goal matching, aggregation, and ultimately, alignment. Finally, the dependencies between goals, both intra-agent and inter-agent, and the strength thereof, necessitate the consideration of cascading effects and the potential for synergistic or conflicting interactions within the cooperative adaptive system.

- (iv)

- Context: The efficacy of cooperative adaptation in AMAs hinges on several critical dimensions of context management, particularly those amplified by the collaborative nature of these systems. Firstly, the strategic considerations of context sharing emerge as paramount, encompassing decisions regarding the specific contextual information to be disseminated, the degree of detail in sharing, and the selective distribution of context based on varying levels of inter-application trust. Secondly, the processes of context consolidation, structuring, and documentation are essential to create shared representations of context that facilitate interoperability and understanding among cooperating entities. The responsibility for context sensing also presents a key design choice in distributed cooperative systems. Furthermore, the depth of contextual awareness varies, ranging from a narrow focus on directly relevant local context to a broader scope encompassing the adaptive actions and internal states of other cooperating applications. Indeed, the context monitoring landscape expands in cooperative scenarios to include the adaptations enacted by partner applications. The granularity and structure of shared context descriptions significantly impact the efficiency of context matching and aggregation. The cooperative state context, including the history of interactions, provides a temporal dimension that can inform trust establishment and dynamically adjust the level of cooperation. Finally, the determination of context relevant to cooperative adaptation, as well as the monitoring of a potential global context, can be approached statically or dynamically, influencing the responsiveness and adaptability of the collaborative effort.

- (v)

- Causes of cooperative adaptation: Cooperative adaptation in cooperative AMAs is initiated by a range of dynamic changes, each presenting distinct dimensions. A primary catalyst for cooperative adaptation arises from the adaptive actions of other mobile applications, which can influence the contextual environment of a given application. The temporal characteristic of the triggering event in cooperative adaptation determines whether the impetus for collaboration is transient or enduring. Furthermore, in the context of adaptive cooperation, an AMA should consider the execution cycle or operational sequence of other AMAs. Recognizing patterns in the execution order of interacting applications can inform the appropriate level of cooperation deemed necessary. Another key dimension regarding the cause of adaptation is predictability, addressing whether the trigger for cooperative adaptation is anticipated and predetermined prior to the cooperative event, or whether it emerges stochastically from the interactions among the applications.

- (vi)

- Aspect: The mechanisms governing cooperative adaptation in AMAs introduce distinct considerations beyond those pertinent to isolated adaptation. A central tenet is that a cooperative AMA may deviate from its independent adaptation trajectory in response to interactions with other applications. The autonomy afforded to an AMA in enacting adaptations within a cooperative framework represents a critical dimension, ranging from complete independence to guidance by a central middleware orchestrating global objectives. The degree of autonomy may further be modulated by the scope or locus of adaptation, with local adaptations potentially exhibiting greater autonomy compared with modifications within shared resources or specialized external components. Cooperative mechanisms can manifest across the phases of the MAPE-K strategy, with applications collaborating in the sensing, analysis, planning, or execution stages. The temporal dimension is multifaceted, encompassing the duration of cooperative engagements (short-term vs. long-term, enabling learning) and the potential influence of sequential application usage by a single user, where the adaptive actions of a preceding application can impact the subsequent one. The learning aspect of cooperative adaptation dictates the generation of cooperative intelligence that must be referred to when analyzing numerous cooperative adaptation actions. Learning mechanisms can range from simple rule-based learning schemas to machine learning engines. The contextual dimension extends beyond that of individual adaptation, encompassing not only the context used to trigger adaptation but also the context affected by the cooperative adaptation process, including shared resources (CPU, memory, network) and third-party services. Furthermore, the effects of failed cooperative adaptation, including the potential for reverting to independent adaptation strategies, constitute a crucial consideration for robustness. Finally, the overhead associated with the cooperative mechanisms, in terms of computational resources, communication, and energy consumption, represents a significant dimension in evaluating their practicality and efficiency.

- (vii)

- Coordination: Cooperative adaptation necessitates the consideration of an additional dimension, distinct yet related to the mechanism dimension, which pertains to the overarching coordination strategy employed for the collective adaptive behavior. The orchestration of overall cooperative adaptation in AMAs necessitates a distinct set of dimensions that, while related to the underlying mechanisms, govern the collective adaptive behavior. Communication forms a foundational dimension, encompassing the modalities through which cooperating AMAs exchange information. This includes direct peer-to-peer interaction, mediation via a third-party proxy or middleware, or hybrid approaches based on trust levels or application affinity. Furthermore, the format and overarching protocol of the communicated data, including considerations for event-based (publish/subscribe) or tuple space models, significantly impact the efficiency and effectiveness of inter-application dialog, directly influencing the “mechanisms for sharing” identified within the broader coordination framework. Security emerges as a critical dimension, particularly in open mobile ecosystems. The establishment of trust circles, where applications exhibit differentiated levels of confidence in their peers, alongside robust access control methods, is essential for preserving data and service integrity during cooperative adaptation.The nature, frequency, granularity, and selectivity of information sharing, along with the underlying communication mechanisms, dictate the level of awareness and common understanding among cooperating entities. Furthermore, the distribution of decision-making authorities, ranging from centralized control to decentralized autonomy with negotiation and consensus protocols, significantly shapes the coordination process. The effectiveness of coordination is also contingent on the employed mechanisms and protocols, which can be explicit or implicit, and their ability to handle the temporal aspects, including synchronization and delays. The level of awareness each application has of its partners’ states and the mechanisms for monitoring cooperative progress and detecting conflicts are critical. Finally, the scalability and dynamicity of the coordination approach, its resilience to changes in group membership, and the level of trust and reliability among cooperating applications are essential considerations for robust and efficient cooperative adaptation in dynamic mobile environments.

- (viii)

- Level of cooperation: This significantly influences cooperative AMAs. It defines the depth and nature of interactions between participating applications and has cascading effects on various aspects of their collaborative behavior. The consolidated dimensions based on the discussions in Section 5 are context information sharing, conflict resolution, and complementary adaptation. Figure 12 illustrates the eight dimensions of cooperative adaptation in mobile applications.

Figure 12. Dimensions of cooperative adaptation.

Figure 12. Dimensions of cooperative adaptation.

5. Threat to Validity

Generally speaking, validity refers to the property of a research design that ensures that the hypothesis is tested in a matter the researcher has intended [115]. Based on the guidelines by [9] regarding software engineering, we tried to mitigate the following validity threats: selection validity, descriptive validity, theoretical validity, and interpretive validity. Table 17 details the rationale.

Table 17.

Treatment of concerns of validity in the study.

6. Related Works

We considered works concerning the systematic review of AMAs. Numerous SLR studies have been conducted on SASs; however, only a limited number focus specifically on AMA systems.

A recent study examined 90 studies dealing with context-aware recommender systems from 2014 to 2024 that are commonly applied to mobile applications. The authors observed a wide practice of the mischaracterization or incomplete characterization of context in the selected studies. They also provided a taxonomy of context-aware recommendation approaches [116]. Another comprehensive review analyzed the salient characteristics of context-aware mobile applications by leveraging a smart city infrastructure [117]. Through the systematic analysis of 27 pertinent research articles, this work delineated the current research landscape concerning context-aware applications in urban smart environments. The review identified key application domains—including urban mobility, healthcare, energy efficiency, public safety, and citizen engagement—as particularly receptive to context-aware functionalities within smart city frameworks. Notably, the authors observed a discernible gap in the current literature regarding the incorporation of contemporary artificial intelligence trends.

A systematic mapping study (SMS) surveyed machine learning methods in developing mobile applications, reviewing 71 articles to document different ML techniques that enabled adaptivity in mobile applications [118]. Artificial neural networks (ANNs) and rules-based classifiers (RBCs) emerged as the most widely used ML techniques in the selected works. The researchers highlighted the need for more robust AI models optimized for mobile environments and recommended explicit rationale in selecting specific ML techniques for given problems.

An extensive systematic literature review spanning 30 years (1990–2020) analyzed 293 papers across different fields of SASs, ranging from the IoT and web services to mobile systems [5]. Ten papers within this corpus addressed self-adaptive mobile systems specifically. The study provided a comprehensive review of self-adaptive systems, analyzing their characteristics, categories, and application domains. Regarding AMAs, the authors noted that research on self-adaptive mobile apps places a strong focus on computing performance and energy efficiency, while standardized frameworks for AMA implementation remain notably lacking.

A recent study with a similar thematic focus that explicitly focused on self-adaptation in smart phone applications is presented in [3]. The authors reviewed 31 studies from 2015 to 2020, providing a systematic analysis of current approaches to developing AMAs. They documented different self-adaptation techniques for mobile applications, namely resource management strategies, context-aware adaptation, machine learning methods, and edge/cloud-based solutions. They also examined the principal impediments encountered in the development of AMAs. The researchers anticipate a novel integration of federated learning for privacy-conscious adaptation based on the given SLR.

Another systematic review that is similar to our SLR covered 44 primary studies from 2006 to 2018, with the goal of enhancing knowledge regarding AMA evolution [4]. The authors provided a customized classification framework for understanding self-adaptation in mobile applications by incorporating quality requirement attributes for the goal dimension and source attributes for the source dimension. The study advocates for more holistic adaptation frameworks, practical implementations, and deployments complemented by case study applications.

The systematic reviews by Grua et al. [4] and Ali et al. [3] reveal complementary methodological approaches and temporal focuses. The 2018 review provides an SLR based on clear protocol adhering to strict standards [4], focusing on foundational work that incorporates earlier studies from 2006 to 2018. In contrast, the 2021 review concentrates on recent advances, covering machine learning-driven approaches from 2015 to 2020 [3]. Moreover, the earlier work posits a multidimensional classification framework tailored for AMAs [4], while the more recent contribution offers a qualitative review focused on techniques and emerging approaches for developing AMAs [3].

This study distinguishes itself from existing systematic reviews through four primary contributions. First, while prior reviews have focused on context-aware mobile applications and recommendation systems [116,117], our work addresses holistic self-adaptation that encompasses adaptation mechanisms, architectural patterns, goal management, and coordination strategies beyond context-awareness alone. Second, unlike domain-specific reviews such as those examining smart city applications [117], we provide a comprehensive cross-domain analysis spanning education, health, gaming, and generic applications, enabling the identification of both domain-specific and domain-agnostic adaptation patterns. Third, our temporal coverage from 2010 to 2025 bridges the gap between reviews focusing on foundational work from 2006 to 2018 [4] and those examining recent advances from 2015 to 2020 [3], providing am integrated historical perspective and evolutionary analysis of AMA development.

Most significantly, a critical distinction between our systematic review and all prior work lies in our explicit focus on the cooperative dimension of adaptive mobile applications. Existing reviews—whether examining context-awareness [116,117], machine learning techniques [118], architectural evolution [4], or contemporary adaptation strategies [3]—implicitly assume independent, single-application adaptation where each AMA optimizes its behavior in isolation. None of these reviews systematically investigate inter-app interference and conflict handling mechanisms (e.g., how to resolve situations where one app’s aggressive battery conservation threatens another’s emergency functionality), global goal negotiation among co-resident applications (e.g., coordinating energy optimization across multiple AMAs rather than competing individual strategies), context sharing protocols and associated privacy implications, or coordination mechanisms for complementary adaptation. Our review addresses this fundamental gap by identifying eight dimensions of cooperative adaptation (MAPE-K structure, domain, goals, context, triggers, aspects, coordination, and cooperation levels) and proposing a classification framework to guide future research in designing AMAs that cooperate rather than conflict within shared mobile ecosystems. This cooperation-centric perspective is entirely absent from existing systematic reviews and represents the primary theoretical contribution of our work.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This systematic review provides both an empirical characterization and theoretical advancement in the field of adaptive mobile applications. Through the analysis of 95 studies spanning 2010–2025, we characterize the current state of adaptive mobile applications across eight research questions addressing approaches, goals, platforms, lifecycle support, and cooperation mechanisms. More significantly, we advance the theory by proposing a dimensional framework for cooperative adaptation comprising eight interdependent dimensions (MAPE-K structure, domain, goals, context, triggers, aspects, coordination, and cooperation levels) and a cooperation level taxonomy that extends existing adaptation models to address the multi-application ecosystem reality of modern mobile devices. This framework addresses a critical gap in the existing literature: while prior systematic reviews examine individual adaptive systems [3,4,116,117,118], none systematically investigate how multiple AMAs detect conflicts, negotiate goals, share contexts, or coordinate adaptive behaviors within shared mobile environments. Our cooperation-centric perspective establishes the conceptual foundation for designing AMAs that cooperate rather than conflict, representing a paradigm shift from individual-centric to ecosystem-centric adaptation research.

The analysis of publication trends in the selected studies reveals a consistent upward trajectory in scholarly output between 2010 and 2018 and a decline in recent years. More recently, research has increasingly concentrated on adaptations that enhance the robustness and functionality of mobile applications. The field currently lacks a central, authoritative publication venue specifically dedicated to AMAs. This is further underscored by the limited number of relevant contributions within seemingly pertinent venues, such as SEAMS. The majority of evaluations provided for the reviewed studies are based on experiments. Studies that attempt to validate an approach to self-adaptation in mobile environment by providing case studies of developed applications are scarce.

The Android platform represents the most considered platform within the reviewed literature, constituting 36.8% of the analyzed papers. Architectural solutions and framework-based approaches constitute the dominant methodologies proposed by the included studies. Furthermore, the design and runtime phases of software development receive the most extensive support across the selected works. However, a discernible gap exists in the comprehensive treatment of solutions spanning the entirety of the development lifecycle.

The analysis of the studies indicates a heterogeneity within adaptation objectives, with “Usability,” “Energy Efficiency,” and “Robust Functionality” receiving prominent attention. While the majority of the analyzed studies (over 66%) concentrated on singular adaptation goals, a notable trend towards addressing multi-objective adaptation scenarios is evident. Sixty percent of the analyzed studies were domain-inert; among domain-specific works, education was most frequent, followed by health and gaming. “Connection” and “device” represent the most frequently considered contextual factors. “User activity” and “user profile” emerge as prominent research foci across multiple domains, notably including education and health. Furthermore, a discernible trend towards the investigation of multiple concurrent contextual variables is evident in more recent scholarly contributions. “Structure” is the most preeminent aspect in the works relating to AMAs, underscoring the focus on architectural adaptability. “Content” and “UI” are the subsequent most frequently addressed aspects. Notably, “content” and “UI” exhibit the highest co-occurrence within the analyzed studies.

This study identified a spectrum of cooperative adaptation strategies, categorized along a continuum of increasing cooperative complexity. This spectrum ranges from a state of “none,” indicating no cooperative adaptation, to “decentralized adaptation,” followed by the “abstraction of adaptation concepts.” Subsequent levels include “multi-device and distributed adaptation,” “recognition of other adaptive applications,” “context sharing and management,” and “conflict resolution,” culminating in “global goal,” representing the highest level of cooperative integration.