Abstract

First-principles calculations of the structural and magnetic properties of kotoite Ni2Co(BO3)2 are carried out. The minimization of the lattice parameters shows the values to be in good agreement with the experimental data (the difference is less than 1%). The atomic coordinates are calculated. Cobaltions are found tending to occupy position 2a and nickel ions tending to occupy position 4f. The same magnetic cell as in Ni3(BO3)2, but quadrupled in size (2a × b × 2c), found having the minimum exchange energy for Ni2Co(BO3)2. In Ni2Co(BO3)2, the magnetic moments are obtained oriented along the baxis, similar to that in Co3(BO3)2.

1. Introduction

The structural formula of oxyborates of the kotoite family reads Me3−xMe′x(BO3)2, where Me and Me′ denote Co, Mn, Ni, Mg, Cu or Cd. Depending on the composition, oxyborates can have different syngonies: orthorhombic, with the space symmetry group Pnnm; triclinic—P1̅; monoclinic—P21⁄c. Ribbons formed by oxygen octahedra of metal ions are an intriguing feature of the crystal structure of these compounds. For example, in Cu3(BO3)2 a complex magnetic structure is observed, with two magnetic phases. In the first phase (the singlet one), individual spins interact, while in the second phase (the magnetically ordered one), clusters consisting of several spins coexist [1]. At 10 K, a magnetic transition to a state representing the superposition of these two phases occurs.

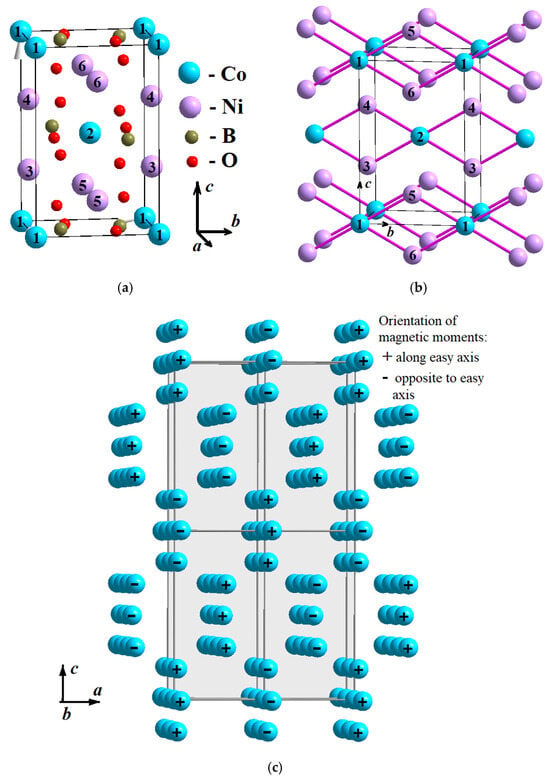

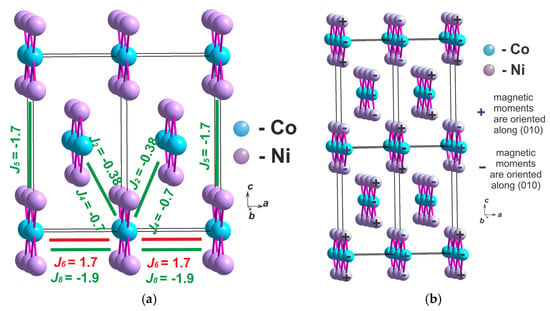

Orthorhombic homometallic oxyborates crystallize in the structure of the mineral kotoite (Figure 1a). Four homometallic kotoites are currently known, in which cobalt, nickel, magnesium, and manganese [2,3,4,5] represent metal ions. The crystal structure [3] and magnetic properties [2] of the first three (manganese, cobalt and nickel) were studied. All three compositions Mn3(BO3)2, Co3(BO3)2 and Ni3(BO3)2 are antiferromagnets. The magnetic structure of the kotoites Ni3(BO3)2 and Co3(BO3)2 was solved by neutron diffraction [3,6]. It was not possible to completely decipher the magnetic structure and determine the magnetic moment of each magnetic ion in the cell; however, it was suggested that the Co3(BO3)2 magnetic cell was four times larger than the elementary crystallographic cell (2a × b × 2c). The magnetic moments of the transition metal ions in Co3(BO3)2 form ribbons (Figure 1b) [3,6]. In the unit cell, there are two ribbons: the first is formed by ions in sites 1, 5 and 6; the second is formed by ions in sites 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 1b). The magnetic moments inside the ribbon are oriented ferromagnetically, while the magnetic moments of different ribbons are oriented antiferromagnetically (Figure 1c). In the kotoite Ni3(BO3)2, the magnetic structure is similar to Co3(BO3)2.

Figure 1.

(a) The crystal structure of the kotoite. Transition metal ions 1 and 2 occupy position 2a (blue circle), while ions 3–6 occupy position 4f (pink circle). (b) The ribbons formed by magnetic ions. (c) The magnetic structure of Ni3(BO3)2. The “+” and “–“ signs show the direction of magnetic moment of ions along c axis. The magnetic moments of ions in the ribbon are ferromagnetic.

The study of the extended X-ray absorption fine structure spectra at the K-edge of the absorption of cobalt ions and the X-ray absorption bear edge structure spectra for the Co3(BO3)2 single crystals [7] showed that the valence state of the cobalt ions was divalent.

Studies of the lattice dynamics of the Ni3(BO3)2 antiferromagnet in the center of the Brillouin zone show that the appearance of several new phonon modes and the anomalous behavior of some “old” phonons at the antiferromagnetic ordering temperature and below are due to the existence of a structural phase transition associated with the magnetic ordering of Ni3(BO3)2 [8]. In Ref. [9], the lattice dynamics of the kotoite Co3(BO3)2 were studied using infrared and Raman spectroscopy. The low-energy part of the phonon spectra differs significantly in Ni3(BO3)2 and Co3(BO3)2, with a frequency shift of up to 55 cm−1. Low-temperature X-ray diffraction studies show no evidence of a magnetostructural phase transition in Co3(BO3)2. The influence of the magnetic order on the phonon dynamics observed in Ni3(BO3)2 also to be of interest and can provide insight into the problem of coupling between the phonon dynamics and the magnetic order [9].

Recent studies have shown that Ni3(BO3)2 has quite high potential as an anode material for sodium-ion batteries. The Ni3(BO3)2 electrode has a high reversible capacity of 428.9 mA h g−1 at 200 mA g−1. Even at a very high current density of 2000 mA g−1, the specific capacity of Ni3(BO3)2 remains at 304.4 mA h g−1 [10].

For the first time, nickel-substituted cobalt oxyborates Co2Ni(BO3)2 and CoNi2(BO3)2 were obtained through a thermally induced solid-state chemical reaction [11,12]. The obtained compounds were shown to have a kotoite structure and to be isomorphic to the homometallic kotoites Co3(BO3)2 and Ni3(BO3)2. Their space group and lattice parameters were obtained, and the infra-red spectra of Co2Ni(BO3)2 and CoNi2(BO3)2 are discussed in Refs. [11,12]. Later, a series of single crystals of the Ni3−xCoxB2O6 compounds with the kotoite structure and different concentrations of transition metal ions (x = 0, 0.19, 0.6, 0.93 and 2) were obtained from the flux system based on Bi2Mo3O12-B2O3, which were diluted with carbonate Na2CO3 [13]. The investigation of the lattice dynamics showed no evidence of a structural phase transition in the Ni3−xCoxB2O6 compounds [14].

To construct a model of magnetic ordering and to understand the principle of phase transition, it is of importance to know the exchange interactions between magnetic ions in the crystal. Ab initio calculations make it possible to calculate the exchange interactions, which allows for a better interpretation of the observed experimental data [15,16,17]. However, not much theoretical work has been conducted on oxyborates, even though solid solutions of Ni3−xCox(BO3)2 are known [13,14,18]. In this study, we present a theoretical investigation of the structural and magnetic properties of kotoite Ni2Co(BO3)2.

2. Structural Properties

According to Ref. [12], the Ni2Co(BO3)2 compound has a crystal structure of kotoite with the space symmetry group Pnnm. In Ref. [12], the parameters of the crystal lattice were determined, but information on the coordinates of the atoms was not provided. Using the Wien2K (version 21) software package, we determined the crystal lattice parameters, atomic coordinates, and distribution of transition metal ions over the positions for the kotoite Ni2Co(BO3)2.

The calculations were carried out within the framework of density functional theory using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functionals with the generalized gradient approximation (PBE–GGA), implemented using the Wien2K software package [19,20,21,22,23,24]. The calculation used the GGA+U method in the Lichtenstein approximation [25]. The modified Blöchl tetrahedral method was applied to calculate the total density of the states [26]. A set of 400 points in the Brillouin zone was used, and the cut off parameter value was 7.0. The energy calculation accuracy was 1 μRy. The following radii of atomic spheres were used in the calculations: 2.02 a.u. for nickel ions, 2.02 a.u. for cobalt ions, and 1.30 a.u. for boron and oxygen ions. In our calculations, we used the optimized effective Hubbard parameter Ueff = 6.8 eV for nickel ions and Ueff = 4.4 eV for cobalt ions [24,27]. Our previous calculations for the Ni3(BO3)2 compound in the kotoite structure showed that at Ueff = 6.8 eV for nickel ions, Ni3(BO3)2 was an insulator with a gap width of about 4 eV [28]. The magnetic moment of nickel ions was 1.8 µB, which corresponds to the spin magnetic moment of the divalent nickel ion. The same values of the Hubbard parameter for nickel and cobalt ions were used in an ab initio study of the structural, electronic, and magnetic properties of a rocksalt cobalt oxide doped with the three-dimensional (3D) transition metal atoms Mn, Fe, and Ni [29]. Therefore, for nickel ions, we used the same value for the parameter Ueff. The Hubbard parameter value for cobalt ions was selected in such a way that the Ni2Co(BO3)2 compound had a band gap and the density of states at the Fermi level was equal to 0. In addition, the spin magnetic moment was to correspond to the magnetic moment of nickel and cobalt ions in the divalent state.

The distribution of magnetic cations over crystallographic positions is essential for revealing magnetic property. Since X-ray diffraction cannot distinguish between nickel and cobalt ions due to the feature that these ions have the same electronic configuration, the distribution of transition metal ions over crystallographic positions cannot be determined. In order to experimentally establish how nickel and cobalt ions are distributed over crystallographic positions, it is necessary to carry out an investigation using neutron diffraction; however, this method is not as accessible a tool as the X-ray diffraction method. There are a number of other studies that may indirectly indicate the occupation of one or another position using ions of the same type. For example, the study of the diffuse scattering spectra and comparison of the Racah parameters for the compounds Ni3(BO3)2 and Co2Ni(BO3)2 also indicates that nickel ions occupy a crystallographic position 4f [13].

In order to reveal how nickel and cobalt ions are distributed over the positions, we calculated the energies of various cation-ordered configurations. The unit cell of kotoite contains six transition metal ions, which occupy two crystallographic positions: 2a and 4f. Ions 1 and 2 occupy position 2a, while ions 3–6 occupy position 4f. The experimental values of the lattice parameters of Ni2Co(BO3)2 and the experimental atomic coordinates for kotoite Ni3(BO3)2 were the starting points for calculating the energy and minimizing the structural parameters for various cation-ordered configurations. Due to the symmetry of the crystal, there are only six different symmetry-inequivalent configurations in Co2Ni(BO3)2 within the unit cell. Table 1 shows the calculated total energies for the cation-ordered symmetry-inequivalent configurations. As can be seen from Table 1, the most preferred ordering is when cobalt ions occupy position 2a, with nickel ions occupying position 4f.

Table 1.

The calculated total energies of various cation-ordered configurations of Ni2Co(BO3)2.

The results of minimizing the lattice parameters and atomic coordinates for the most preferred type of cationic ordering are provided in Table 2. The minimization of the lattice parameters showed the values to be in good agreement with the experimental data (the difference is less than 1%). Table 2 also shows the distances between the metal ions in the first and second coordination spheres and Me-O distances. The ions of both metals are in an octahedral environment of the oxygen ions; the Me-O distances are typical of oxyborates [30,31]. The oxygen octahedron around the cobalt ions is somewhat elongated, while the oxygen octahedron around the nickel ions is compressed.

Table 2.

The calculated structural parameters of Ni2Co(BO3)2.

The Me–Me distances are found to be large enough to create overlapping electron planes and direct exchange interactions. The crystal structure suggests two types of indirect exchange interactions: Me–O–Me and Me–O–B–O–Me. Super–super exchange interactions Me–O–B–O–Me play a significant role in establishing magnetic order in oxyborates. For example, in the compound Co3BO3O2 with a ludwigite structure, divalent cobalt ions form planes, with trivalent cobalt ions being located between them. However, Co3+ ions are in a low-spin state and their magnetic moment is zero [30,31]. An exchange interaction between the planes can only occur via the super–super exchange interactions Co–O-B–O–Co, which looks to be comparable in magnitude to the exchange interactions Co–O–Co, since the compound undergoes a transition to a ferrimagnetic state at a temperature of 42 K. It is intriguing that the spinels compounds GeNi2O4 and GeCo2O4, despite containing different magnetic ions, present the same magnetic order [32]. These compounds are isostructural and both magnetic ions (Ni and Co) are presented in the divalent state as in Ni3(BO3)2 and Ni2Co(BO3)2. In GeNi2O4 and GeCo2O4, to explain the overall antiferromagnetic behavior, super–super exchange with the third neighbors, which are antiferromagnetic, need to be included. In these compounds there to be no orbital overlap with the second neighbors [33]. Thus, in oxydes and oxyborates, super–super exchange interaction with second or third neighbors plays a significant role in forming the magnetic order.

3. Magnetic Properties

The compounds Co3(BO3)2 and Ni3(BO3)2 are known to be antiferromagnets, and the easy magnetization axis in these compounds is oriented along the crystallographic directions b and c, respectively [34]. In one of our previous studies, we determined the exchange interaction parameters of the kotoite Ni3(BO3)2 and showed the exchange interactions of the second coordination sphere to be essential in the formation of magnetic order. We also observed an increase in the magnetic cell [28]. The exchange interaction parameters were determined from the calculation of the total energies of different magnetically ordered structures. Using the same technique as that in Ref. [28], we calculated the exchange interaction parameters for the kotoite Ni2Co(BO3)2.

The exchange interaction parameters were estimated from the calculated energy values for a number of different spin configurations, both for the magnetic cell coinciding with the crystallographic one and for the magnetic cells doubled along the a and c axis. Since only the spin configuration changed upon calculating the energies, and the other parameters of the crystal structure remained unchanged, the total energy can be written as a sum of the exchange contribution (the first term) and the constant value ():

where is the exchange interaction parameters between the i and j atoms.

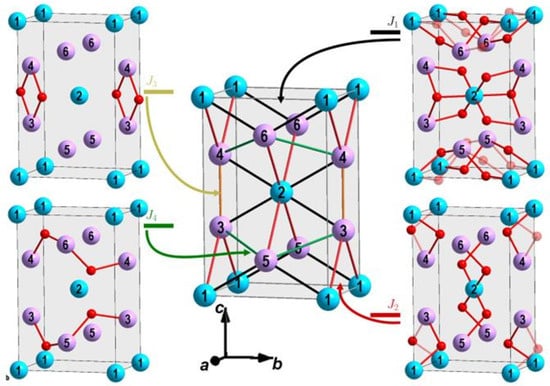

We used the Heisenberg model [35,36] and, as a first step, we considered the case of isotropic exchange interactions and did not take into account the anisotropic contribution and other effects. Then, for the description, we used the exchange interaction parameters depicted in Figure 2 and Figure 3 and given in Table 3 and Table 4. The parameters of the exchanges of the first coordination spheres are associated with Me–O–Me super exchange interactions (Figure 2 and Table 3). is the parameter of the exchange interaction between atoms 1–5, 1–6, 2–3, 2–4; is the parameter of the exchange interaction between atoms 1–3, 1–4, 2–5, 2–6; is the parameter for atoms 3–4 and 5–6; and is the parameter for atoms 3–5 and 4–6.

Figure 2.

The exchange interactions of the first coordination spheres associated with Me-O-Me super exchange interactions: (black lines), (red lines), (yellow lines), and (green lines). The colors of the circles are as in Figure 1a,b.

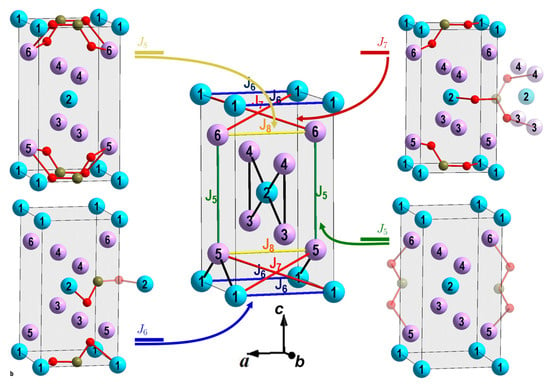

Figure 3.

The exchange interactions of the second coordination spheres associated with the Me-B-O-B-Me super–super exchange interactions: (green lines), (blue lines,) (red lines), and (yellow lines). The colors of the circles are as in Figure 1a,b.

Table 3.

The Me–O distances and Me–O–Me angles for the exchange interactions of the first coordination spheres of Ni2Co(BO3)2.

Table 4.

The Me-O, B-O distances and the Me–O–B, O–B–O angles for the exchange interactions of the second coordination spheres of Ni2Co(BO3)2.

The exchange parameters of the second coordination spheres associated with the Me–B–O–B–Me super–super exchange interactions (Figure 3, Table 4). The parameters is the parameter of the exchange interaction of the second coordination sphere between ions 3–4 (5–6), is the parameter for ions 1–1, is the parameter for 1–6 (5) or 2–3 (4), and is the parameter for 3–3, 4–4, 5–5, 6–6. The remaining parameters of exchange interaction are assumed to be equal to zero.

As can be seen from Figure 2 and Figure 3, the exchange interactions inside the triangular ribbons are , while and are the exchange interactions between the ribbons in the first coordination sphere. The exchange interactions between the ribbons in the second coordination sphere are (along the c axis) and (along the a axis).

The exchange interaction parameters were determined from the calculation of the total energies of different magnetically ordered structures (Table 5 and Table 6). Table 5 and Table 6 show the directions of the magnetic moments, expressions of the exchange contribution to the energy through the exchange interaction parameters and the calculated values of the exchange part of the energy ( see Equation (1)) of different spin configurations for the magnetic cells coinciding with the crystallographic one and for the doubled magnetic cells. The calculated values of the exchange interaction parameters for Ni2Co(BO3)2 are presented in Table 7. The calculations were carried out using the least squares method. The calculation error was 2 × 10−5 eV.

Table 5.

The up (u) and down (d) orientation of the magnetic moments on atoms, expressions of the exchange contribution to the energy through the exchange interaction parameters, and the calculated values of the exchange part of the energy of different magnetically ordered structures for the magnetic cells coinciding with the crystallographic one.

Table 6.

The up (u) and down (d) orientation of the magnetic moments on atoms, expressions of the exchange contribution to the energy through the exchange interaction parameters, and calculated values of the exchange part of the energy of different magnetically ordered structures for the magnetic cells doubled along the a and c axes.

Table 7.

The exchange interaction parameters (jn meV)obtained, taking into account the contributions to the exchange interaction energy of the second coordination sphere. The calculation error was 2 × 10−5 eV.

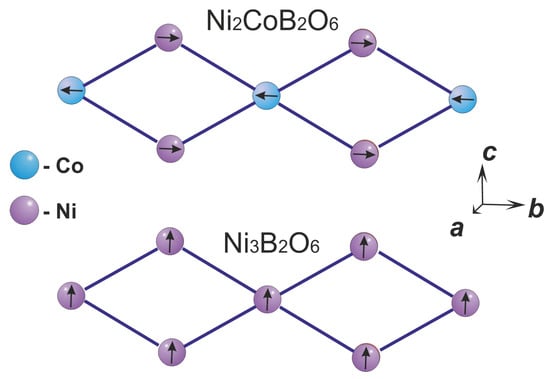

As can be seen from Table 5, in Ni2Co(BO3)2, the strongest exchange interactions occurred between the spins in the second coordination sphere. The exchange interactions inside the triangular ribbons () do not compete with each other, despite the different nature of their interactions. The interactions are ferromagnetic, agreeing with the Goodenough–Kanamori rule [34] for 90° Ni–O–Ni interactions. The magnetic order in the triangular ribbons imposed by the exchange interactions is shown in Figure 4. In contrast to Ni3(BO3)2, where all the spins in the ribbons are oriented ferromagnetically, in Ni2Co(BO3)2 the spins of cobalt ions and the spins of nickel ions are oriented antiferromagnetically. Previously, in the framework of the indirect semi-empirical model [37,38,39,40], we calculated the super exchange interactions Me-O-Me for the solid solutions Ni3−xCox(BO3)2 (x = 0, 1, 2, 3) [18]. The calculation results show that if cobalt ions occupy position 2a, then the spins of nickel and cobalt ions in the ribbons are oriented antiferromagnetically. The results of the ab initio and semi-empirical calculations agree with each other. However, if only the exchange interactions of the first coordination sphere are considered, the increase in the magnetic cell cannot be explained.

Figure 4.

The magnetic ordering in the ribbons in Ni2Co(BO3)2 and Ni3(BO3)2. The arrows in circles show the direction of the magnetic moment in atoms.

There are six parameters of exchange interactions between the ribbons: two are in the first coordination sphere ( and ) and four are in the second coordination sphere (, and ) (Figure 5a). The and parameters associated with the super exchange interactions Me-O-Me. These are the interactions of the nearest ribbons in the same unit cell. The , , and parameters are associated with the Me-B-O-B-Me super–super exchange interactions. These are the interactions of the ribbons in different unit cells. The exchange interactions and orient the ribbons along the a-axis. The exchange interactions and compete with each other. The ferromagnetic exchange interactions add a part to the competition between the exchange interactions and and orient the nearest ribbons along the a-axis in the opposite direction. The exchange interactions orient the ribbons along the c-axis. The antiferromagnetic exchange interactions orient the nearest ribbons along the c-axis in the opposite direction (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

(a) The exchange interactions between the ribbons in the first coordination sphere ( and ) and in the second coordination sphere (, and ) in Ni2Co(BO3)2 (b) The magnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy for the magnetic cell quadrupled in size (2a × b × 2c).

We used the calculated exchange interaction parameters to determine the magnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy. We used the magnetic cell quadrupled in size (2a × b × 2c) to compare different types of magnetic order. The exchange part of the energy for different magnetic ordered structures was calculated using the equation . The magnetic structure shown in Figure 5b has the lowest exchange energy per cell. Although the magnetic spins in the ribbons were oriented ferrimagnetically, the magnetic ordering of the ribbons relative to each other corresponds to this type of magnetic structure, and was proposed as a result of studying the magnetic structure of Ni3(BO3)2 using the neutron diffraction method (Figure 1c). It looks that the exchange interactions of the second coordination sphere make the largest contribution to the magnetic ordering of the ribbons relative to each other and are responsible for the increase in the magnetic cell.

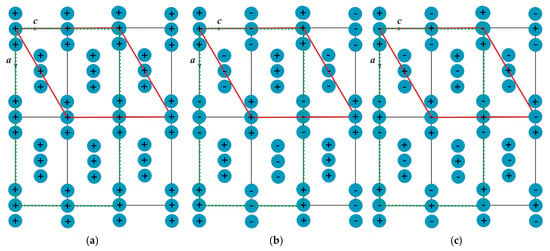

In order to verify the assessment accuracy of the exchange interactions, we directly calculated the total energies of the following magnetic structures: ferromagnetic structure (Figure 6a), antiferromagnetic structure as in Ni3(BO3)2 (Figure 6b), and antiferromagnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy (Figure 6c). For the calculations, we used a rhombic magnetic cell (2a × b × 2c) presented as a monoclinic one (P21/c), doubling the primitive cell relative to the paramagnetic phase (2c, −b, a + c, 0.0.0), as shown by the red line in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Different magnetic structures, whose total energies were calculated directly: ferromagnetic structure (a), antiferromagnetic structure, as in Ni3(BO3)2 (b), and antiferromagnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy (c). The rhombic magnetic cell (2a × b × 2c) is indicated by the dotted green line, and the monoclinic cell P21/c corresponding to the rhombic magnetic cell (2c × b × 2c) is shown by the red line. The transition metal ions are indicated by the blue circles and the directions of their magnetic moment alongside and opposite to the easy axis are shown by + and −, respectively.

We have also calculated the exchange part of the energy for these structures using the calculated exchange interactions. Table 8 presents the energy difference for the two types of antiferromagnetic ordering relative to the ferromagnetic state, both for the direct energy calculation (second column) and for the exchange contribution calculated from the exchange interaction parameters (third column). As can be seen from Table 8, the energy difference between the direct calculation and the calculation performed using the exchange interaction parameters agrees within 7%, which, we believe, is good enough. Thus, the obtained exchange interaction parameters can be used to describe the magnetic structure of the compound under study.

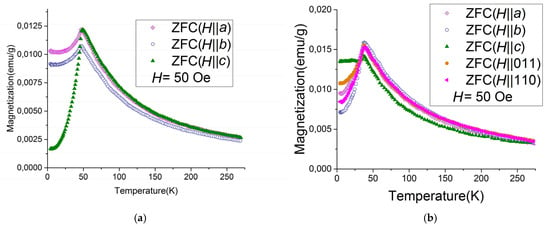

The experimental study shows that in stoichiometric antiferromagnetic Ni3B2O6 and Co3B2O6 compounds, the easy axis of magnetization coincides with the crystallographic directions c and b, respectively [41]. Our recent experimental study of the magnetization of the solid solutions Ni3−xCox(BO3)2 (x = 0.19; 0.6; 0.93, 2) reveals that at low concentrations of cobalt ions x < 0.6, the magnetic moments are oriented along the crystallographic direction c. At a concentration of cobalt ions in the range of 2 ≤ x ≤ 3, the magnetic moments are oriented along the crystallographic direction b, and at x = 0.93, the magnetic moments lie in the ab-plane but are canted to the b-axis [18]. Figure 6 shows the orientation dependences of the magnetization of Ni3(BO3)2 and Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2, measured at magnetic field H = 50 Oe in the zero-field cooling (ZFC) mode [18]. As can be seen from Figure 6a, the temperature dependences of the magnetization of Ni3(BO3)2 are typical for the antiferromagnetic and the easy magnetization axis coincides with the crystallographic direction c (green triangle curve). In Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2 (Figure 6b), the magnetic moments are orthogonal to the c-axis and lie in the plane ab, but they are canted to the b-axis [18]. The magnetic transition temperatures are 46 K for Ni3(BO3)2 and 35 K for Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2.

The magnetic ordering temperature can be estimated using the mean-field theory within the four-sublattice antiferromagnet model [42] using the calculated exchange interactions, assuming that the rhombic magnetic cell (2a × b × 2c) is presented as a monoclinic one (P21/c) with the doubling of the primitive cell relative to the paramagnetic phase (2c, −b, a + c, 0.0.0). For the estimation, we used the exchange interactions from Table 5. For the four-sublattice antiferromagnet, the equation for determining critical temperature Tc yields two negative roots and two complex roots with the real part being 47 K, which is close to the observed magnetic transition temperature 35 K for Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2.

In the ab initio calculation, in order to determine the orientation of the magnetic moments relative to crystallographic directions, the total energies of the ferromagnetic state were calculated, taking into account spin–orbit interactions with the magnetic moments oriented along the crystallographic directions. Table 9 shows the difference between the energy of the antiferromagnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy in the monoclinic cell P21/c for Ni2Co(BO3)2 with the magnetic moments oriented along the crystallographic axis [uvw]. Table 9 shows the orientation of the magnetic moments in the rhombic magnetic cell (2a × b × 2c) and in the monoclinic cell P21/c. We also show the calculated energies per formula unit and the difference between the energies in meV. As follows from the calculations performed, the magnetic moments in Ni2Co(BO3)2 are directed along the b-axis, but the difference from the a-axis is relatively small. The experimental data show that in Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2, the magnetic moments lie in the ab-plane but are canted to the b-axis (Figure 7b).

Table 9.

The calculated energies of the ferromagnetic state, depending on the orientation of the magnetic moments.

Figure 7.

The temperature dependences of magnetization for Ni3(BO3)2 (a), Ni2.07Co0.93(BO3)2 (b), measured in a magnetic field H = 50 Oe applied alongside different crystallographic directions in the zero field cooling (ZFC) mode: along the crystallographic direction a (gray rhomb), b (empty circle), c (green triangle), [011] (orange square), and [110] (pink star) [18].

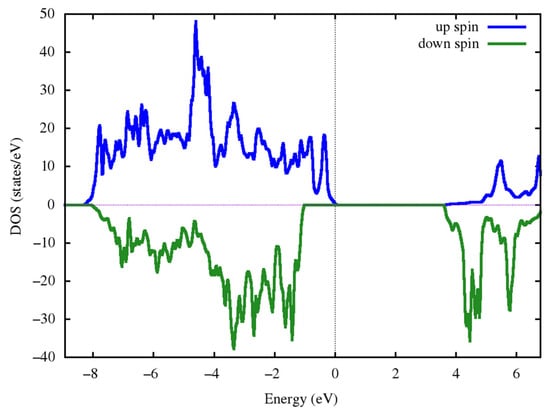

The total density of the state for the magnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy in the monoclinic cell P21/c is presented in Figure 8. As can be seen from Figure 8, the Ni2Co(BO3)2 compound has a band gap at about 3.5 eV.

Figure 8.

The total density of the state for the magnetic structure with the lowest exchange energy in the monoclinic cell P21/c.

The calculated magnetic moments of nickel and cobalt atoms in Ni2Co(BO3)2 are presented in Table 10. For both magnetic ions, the calculated magnetic moments are seen to be close to the nominal ones, corresponding to the high-spin state with the spin S = 3/2 for cobalt ions and S = 1 for nickel ions.

Table 10.

The calculated magnetic moments of nickel and cobalt atoms for Ni2Co(BO3)2.

4. Conclusions

In complex compounds where magnetic atoms occupy several crystallographic positions, it is complicate enough to describe the magnetic structure due to the large number of parameters of exchange interactions that can have different mechanisms. In kotoites M3−xM’(BO3)2, indirect exchange can occur via different exchange pathways, including both Me-O-Me and Me-O-B-O-Me. If only the exchange interactions of the first coordination sphere (Me-O-Me) are considered, the reasons for the increase in the magnetic cell are unclear. Estimates of the parameters of exchange interactions using first-principles calculation methods have shown that antiferromagnetic exchange interactions of the second coordination sphere (Me-O-B-O-Me) may play a significant role in establishing the magnetic order. Despite the point that first-principles calculation methods have a number of limitations—for example, the calculation is carried out for T = 0 K—a qualitative assessment is crucial in order to understand the mechanisms of magnetic phase transitions in the compounds under study.

In this paper, we performed a theoretical study of the structural and magnetic properties of the kotoite Ni2Co(BO3)2. The calculated values of the crystal lattice parameters are obtained to be in sufficiently good agreement with the experimental data. The study of cationic ordering shows that cobalt ions tend to occupy the 2a position. Despite the finding that the exchange interaction parameters of Ni2Co(BO3)2 differ from those of Ni3(BO3)2, the same magnetic cell as in Ni3(BO3)2 is obtained to have the minimum exchange energy. However, the magnetic ordering in the ribbons is ferrimagnetic and the direction of the magnetic moments changes. While in Ni3(BO3)2 the magnetic moments are oriented along the c-axis, in Ni2Co(BO3)2 the magnetic momenta are oriented along the b-axis, but the difference with the a-axis found to be quite small, which is in agreement with the experimental data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.; methodology, S.S.; validation, A.K., A.S. and T.T.; investigation, S.S., A.C., A.S. and T.T.; data curation, T.T. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, S.S. and A.C.; writing—review and editing, A.K. and S.S.; visualization, T.T.; supervision, S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was supported by the Russian Science Foundation and Krasnoyarsk Regional Science Foundation, project No. 23-12-20012.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Petrakovskii, G.A.; Sablina, K.A.; Vorotynov, A.M.; Bayukov, O.A.; Bovina, A.F.; Bondarenko, G.V.; Szymczak, R.; Baran, M.; Szymczak, H. Synthesis and magnetic properties of Cu3B2O6 single crystals. Phys. Sol. State 1999, 41, 610–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, R.E.; Santoro, R.P.; Seal, P.F.; Stallings, G.R. Antiferromagnetism in Mn3B2O6, Co3B2O6, and Ni3B2O6. Phys. Status Sol. (b)/Basic Sol. State Phys. 1966, 16, K17–K19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effenberger, H.; Pertlik, F. Verfeinerung der Kristallstrukturen der isotypen Verbindungen M3(BO3)2 mit M = Mg, Co und Ni (Strukturtyp: Kotoit). Z. Kristallogr./Crystal. Mater. 1984, 166, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, S.V. The crystal structure of the isomorphous orthoborates of cobalt and magnesium. Acta Chem. Scand. 1949, 3, 660–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo, J.; Martinez-Ripoll, M.; García-Blanco, S. The crystal structure of nickel orthoborate, Ni3(BO3)2. Acta Crystallogr. B 1974, 30, 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newnham, R.; Redman, M.; Santoro, R. Neutron-diffraction study of Co3B2O6. Z. Kristallogr./Crystal. Mater. 1965, 121, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazak, N.V.; Platunov, M.S.; Ivanova, N.B.; Knyazev, Y.V.; Bezmaternykh, L.N.; Eremin, E.V.; Vasil’ev, A.D.; Bayukov, O.A.; Ovchinnikov, S.G.; Velikanov, D.A.; et al. Crystal structure and magnetization of a Co3B2O6 single crystal. J. Exp. Theor. Phys. 2013, 117, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisarev, R.V.; Prosnikov, M.A.; Davydov, V.Y.; Smirnov, A.N.; Roginskii, E.M.; Boldyrev, K.N.; Molchanova, A.D.; Popova, M.; Smirnov, M.B.; Kazimirov, V.Y. Lattice dynamics and a magnetic-structural phase transition in the nickel orthoborate Ni3(BO3)2. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 134306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molchanova, A.; Prosnikov, M.; Petrov, V.; Dubrovin, R.; Nefedov, S.; Chernyshov, D.; Smirnov, A.; Davydov, V.; Boldyrev, K.; Chernyshev, V.; et al. Lattice dynamics of cobalt orthoborate Co3(BO3)2 with kotoite structure. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 865, 158797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Tian, J.; Ma, X.; Ping, Q.; Wang, B.; Xia, Y. Ni3(BO3)2 as anode material with high capacity and excellent rate performance for sodium-ion batteries. Chem. Engin. J. 2019, 363, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekin, B.; Güler, H. Synthesis and crystal structure of dicobalt nickel orthoborate, Co2Ni(BO3)2. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2008, 108, 88–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, H.; Tekin, B. Synthesis and crystal structure CoNi2(BO3)2. Inorg. Mater. 2009, 45, 538–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronova, S.; Moshkina, E.; Chernyshev, A.; Vasiliev, A.; Maximov, N.; Aleksandrovsky, A.; Andryushchenko, T.; Shabanov, A. Crystal growth and cation order of Ni3-xCoxB2O6 oxyborates. CrystEngComm 2024, 26, 2536–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronova, S.N.; Pavlovskii, M.S.; Krylova, S.N.; Vtyurin, A.N.; Krylov, A.S. Lattice Dynamics of Ni3−xCoxB2O6 Solid Solutions. Crystals 2024, 14, 994. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4352/14/11/994 (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Sofronova, S.; Chernyshev, A. Magnetic ordering and the role of superexchange Ni–O–B–O–Ni upon the formation of magnetic order in ludwigite Ni2MnBO5 from first-principal calculations. Comput. Condens. Matter 2024, 40, e00918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pchelkina, Z.V. Calculation of Magnetic Exchange Interactions and Construction of a Spin Model for Low-Dimensional Magnetic Compounds. J. Electron. Mater. 2019, 48, 1480–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novak, P.; Chaplygin, I.; Seifert, G.; Gemming, S.; Laskowski, R. Ab-initio calculation of exchange interactions in YMnO3. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2008, 44, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronova, S.N.; Velikanov, D.A.; Moshkina, E.M.; Chernyshev, A.V. Magnetization of solid solutions of antiferromagnets Ni3−xCoxB2O6 with the competing orientation of anisotropy axes. Bull. Russ. Acad. Sci. Phys. 2024, 88, S47–S52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjöstedta, E.; Nordströma, L.; Singhb, D. An alternative way of linearizing the augmented plane-wave method. Sol. State Commun. 2000, 114, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaha, P.; Schwarz, K.; Madsen, G.; Kvasnicka, D.; Luitz, J. An Augmented Plane Wave + Local Orbitals Program for Calculating Crystal Properties; Vienna University of Technology Inst. of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry: Vienna, Austria, 2024. Available online: http://www.wien2k.at/reg_user/textbooks/usersguide.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Blaha, P.; Schwarz, K.; Tran, F.; Laskowski, R.; Madsen, G.; Marks, L. WIEN2k: An APW+lo program for calculating the properties of solids. J. Chem. Phys. 2020, 152, 074101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdew, J.; Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 1992, 45, 13244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perdew, J.P.; Burke, K.; Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1996, 77, 3865–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anisimov, V.I.; Zaanen, J.; Andersen, O.K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner. I. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 943–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shick, A.B.; Liechtenstein, A.I.; Pickett, W.E. Implementation of the LDA+U method using the full-potential linearized augmented plane-wave basis. Phys. Rev. B 1999, 60, 10763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blöchl, P.E.; Jepsen, O.; Andersen, O.K. Improved tetrahedron method for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 49, 16223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimov, V.I.; Solovyev, I.V.; Korotin, M.A.; Czyżyk, M.T.; Sawatzky, G.A. Density-functional theory and NiO photoemission spectra. Phys. Rev. B 1993, 48, 16929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sofronova, S.N.; Nazarenko, I.I. Super-superexchange influence on magnetic ordering in Ni3B2O6 kotoite. Phys. Status Sol. (b)/Basic Sol. State Phys. 2019, 256, 1900060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatiev, P.A.; Negulyaev, N.N.; Bazhanov, D.I.; Stepanyuk, V.S. Doping of cobalt oxide with transition metal impurities: Ab initio study. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81, 235123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.C.; Medrano, C.P.C.; Sanchez, D.R.; Nunez, R.M.; Velamazan, J.A.R.; Continentino, M.A. Magnetism and charge order in the ladder compound Co3O2BO3. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 94, 174409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, D.C.; Continentino, M.A.; Guimar, R.B.; Fernandes, J.C.; Ellena, J.; Ghivelder, L. Structure and magnetism of homometallic ludwigites: Co3O2BO3 versus Fe3O2BO3. Phys. Rev. B 2008, 77, 184422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, S.; de Brion, S.; Holzapfel, M.; Chouteau, G.; Strobel, P. Study of competitive magnetic interactions in the spinel compounds GeNi2O4, GeCo2O4. Physica B 2004, 346–347, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, S.; de Brion, S.; Chouteau, G.; Strobel, P.; Canals, B.; Carvajal, J.R.; Rakoto, H.; Broto, J.M. Magnetic frustration in the spinel compounds GeNi2O4 and GeCo2O4. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 97, 10A512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, J. Superexchange interaction and symmetry properties of electron orbitals. J. Phys. Chem. Sol. 1959, 10, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vleck, J.H. The Theory of Electric and Magnetic Susceptibilities; Claredon Press/Oxford University Press: London, UK, 1932; Available online: https://archive.org/details/theoryofelectric031070mbp (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Heisenberg, W. Mehrkörperproblem und Resonanz in der Quantenmechanik. Z. Phys. 1926, 38, 411–426, English translation: The multibody problem and resonance in quantum mechanics. Available online: http://xdel.ru/downloads/www.nonloco-physics.0catch.com (accessed on 11 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W. New approach to the theory of superexchange interactions. Phys. Rev. 1959, 115, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawatzky, G.A.; Geertama, W.; Haas, C. Magnetic interactions and covalency effects in mainly ionic compounds. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 1976, 3, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.W. Theory of magnetic exchange interactions:Exchange in insulators and semiconductors. Sol. State Phys. 1963, 14, 99–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayukov, O.A.; Savitskii, A.F. The prognostication possibility of some magneticproperties for dielectrics on the basis of covalency parameters of ligand–cation bonds. Phys. Status Sol. (b)/Basic Sol. State Phys. 1989, 155, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezmaternykh, L.N.; Sofronova, S.N.; Volkov, N.V.; Eremin, E.V.; Bayukov, O.A.; Nazarenko, I.I.; Velikanov, D.A. Magnetic properties of Ni3B2O6 and Co3B2O6 single crystals. Phys. Status Sol. (b)/Basic Sol. State Phys. 2012, 249, 1628–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupička, S. Physik der Ferrite und der Verwandten Magnetischen Oxide; Friedr. Vieweg+Sohn Braunschweig/ACADEMIA: Prague, Czech Republic, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.