Abstract

The Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) is a prevalent concept in cyber defense; nevertheless, its emphasis on post-reconnaissance phases limits the capacity to foresee attacker activities outside the organizational boundary. This study introduces and empirically substantiates a pre-chain phase, referred to as contextual anticipation, which broadens the temporal framework of the CKC by methodically identifying subtle yet actionable signals prior to reconnaissance. The methodology combines the STEMPLES+ framework for socio-technical scanning with General Morphological Analysis (GMA), generating internally coherent scenarios that are translated into Indicators of Threats (IOT). These indicators connect contextual triggers to threshold-based monitoring activities and established courses of action, forming a reproducible and auditable relationship between foresight analysis and operational defense. The application of three illustrative cases—a banking merger, the distribution of a phishing kit in underground marketplaces, and wartime contribution scams—illustrated that contextual anticipation consistently provided quantifiable lead-time benefits varying from several days to six weeks. This proactive stance enabled measures such as registrar takedowns, targeted awareness campaigns, and anticipatory monitoring before distribution and exploitation. By formalizing CKC-0 as an integrated socio-technical phase, the research enhances cybersecurity practice by demonstrating how diffuse contextual drivers can be converted into organized, actionable mechanisms for proactive resilience.

1. Introduction

The Lockheed Martin Cyber Kill Chain (CKC) has organized modern cyber-defense methodologies by breaking down multi-stage incursions into a process that coordinates controls, intelligence, and response. Many analyses and evaluations highlight that significant attacker activity increasingly occurs earlier—beyond enterprise boundaries and before detectable reconnaissance—thereby advocating for systematic interventions to the left of the kill chain, especially as adversaries enhance automation and AI in their operations [1,2]. Notwithstanding its constraints, the CKC remains one of the most prevalent frameworks for articulating multi-stage incursions within security operations, intelligence processes, and defensive engineering. Its significance lies in providing a consistent, stage-oriented lexicon that connects adversarial actions to defensive obligations, thereby facilitating decision-making, playbook development, and inter-team communication. Various industry frameworks, such as MITRE ATT&CK-aligned detection engineering, Security operation center (SOC) alert pipelines, and Cyber threat intelligence (CTI) reporting structures, continue to use CKC semantics as the foundational grammar for delineating attack progression. Consequently, extending CKC rather than replacing it ensures backward compatibility with existing operational procedures while facilitating a more sophisticated understanding of adversarial preparation. The introduction of a pre-reconnaissance phase enhances the CKC model by resolving established time gaps and including contextual, externally observable information that conventional CKC implementations consistently neglect.

To bridge this gap, we propose a specific phase that precedes reconnaissance: Contextual Anticipation. Contextual anticipation formalizes proactive, external anticipation by identifying subtle yet actionable signals within the socio-technical landscape that influence attacker motivations, opportunities, and logistics—such as regulatory deadlines, public brand events, supplier transitions, and fluctuations in crime-as-a-service (CaaS) markets. Contextual anticipation is operationalized through a systematic environmental assessment utilizing an enhanced STEMPLES+ framework (a variant of PESTEL that includes social, technological, economic, military/market, political/policy, legal/regulatory, environmental, and security-related external factors) in conjunction with General Morphological Analysis (GMA). STEMPLES+ guarantees extensive coverage of drivers; GMA subsequently organizes these drivers into uniform pre-intrusion scenarios and eliminates incongruous pairings. The outcome is a replicable process that transforms ambiguous contexts into specific monitoring tasks and proactive measures prior to delivery, utilization, or installation [3,4,5].

The theoretical foundation for this transition is rooted in futures research concerning weak signals—initial, low-intensity indicators that foreshadow more pronounced changes. Hiltunen’s “future sign” model (signal, issue, interpretation) offers a pragmatic framework for identifying and analyzing precursors, while Holopainen and Toivonen reaffirm Ansoff’s assertion that businesses must monitor for strategic surprises and respond before discontinuities solidify. Applied to cyber threats, these concepts encourage a systematic approach to detecting, classifying, and responding to pre-intrusion signs before the CKC’s established phases within the target environment [6,7].

Multiple categories of Contextual Anticipation observables are currently quantifiable at scale—infrastructure footprints often manifest days to weeks before payload delivery or exploitation. Typosquatting and look-alike domain registrations that facilitate phishing and brand impersonation demonstrate longitudinal tendencies prior to content deployment, providing observable lead time for registrar interventions, targeted takedowns, and consumer contacts. Similarly, Certificate Transparency (CT) records provide issuance patterns that can be analyzed for anomalous hostnames and requester behaviors suggestive of impending phishing activities. These signals are extrinsic to the victim network, cost-effective to monitor, and suitable for auditable watchlists, rendering them quintessential inputs for Contextual Anticipation [8,9].

A complementary perspective emerges from the professionalization of CaaS markets. Surveys and official evaluations depict developed underground markets that facilitate initial access, sell phishing kits, rent botnets, and provide customer support; the presence of price points, availability indicators, and changes in tools serve as macro-level indicators of attacker capability. Due to the intersection of these markets with registrars, payment systems, and hosting services, they generate legal and policy mechanisms that can be most effectively utilized prior to delivery or exploitation—further justifying the need for the institutionalization of proactive, external observation and intervention [10,11].

Contextual Anticipation, framed under resilience engineering, corresponds with principles that prioritize anticipation and adaptation over simply detection and reaction. NIST SP 800-160 Vol. 2 Rev. 1 delineates methodologies to mitigate, avert, and strategize for detrimental occurrences; these methodologies are inherently activated when Contextual Anticipation signals prompt prior governance, procurement, legal, communications, and security measures (e.g., expedited supplier fortification, registrar interventions against similar domains, or focused customer communications aligned with a recognized risk period). Implementing these steps early mitigates unforeseen issues later in the kill chain and expands the range of organizational roles that actively engage in prevention [12].

In this context, we present Indicators of Threats (IOT) as organized, externally discernible signals derived from STEMPLES+ scanning that likely precede and influence subsequent CKC stages. IOTs are operationally defined to be managed by security and risk teams: each element delineates a source (e.g., CT logs, registrar feeds, underground market surveillance), a query or heuristic (e.g., brand + keyword patterns, anomalous issuer/requester pairs), a threshold (e.g., surge relative to a moving baseline), and a prescribed course of action (e.g., registrar escalation, pre-emptive client notification, targeted sensor deployment).

Instances include spikes in look-alike domain registrations targeting a brand prior to a significant launch, irregular CT issuance trends for brand-associated hostnames, and fluctuations in pricing/availability within access-broker listings for a relevant sector. IOT conceptually connects the abstract drivers identified by STEMPLES+ to tangible operational decisions; in practice, they offer auditable watchlists that link strategic context with daily defensive actions [3,8,9].

The proposed process methodologically advances in three stages. Initially, socio-technical drivers are identified using STEMPLES+ and customized to the organization’s specific sectoral setting (e.g., regulatory timelines, supplier turnover, market narratives, established rival business models). Secondly, GMA is employed to construct a morphological matrix that intersects essential factors, including initial contact channels (email, SMS, social media, telephony), execution platforms (web, mobile, cloud, on-premises), and enabling conditions (rebranding events, merger timelines, tax seasons, widely publicized vulnerabilities), while omitting inconsistent or implausible combinations. Third, each consistent configuration is converted into IOT entries and aligned with preventive measures that can be implemented prior to delivery and exploitation. This approach integrates horizon scanning with threat-centric modeling to eliminate arbitrary lists of “items to monitor,” resulting in a systematic, repeatable process that can be managed and evaluated [3,4,5].

Contextual anticipation diverges from typical “shift-left” recommendations in terms of both breadth and methodology. Instead of simply promoting earlier detection, it delineates a formally defined phase that is distinctly external to the protected network, underscores actionable signals (e.g., registrar or hosting interventions, legal measures, targeted communications), and associates each signal with a pre-established course of action. This architecture mitigates the scope limitations identified by CKC detractors, including sensor-of-record bias toward on-host telemetry, overly linear interpretations, and insufficient connection to strategic context, while maintaining the advantages of a stage-based vocabulary [1,2].

The objective is to prolong the intervention window for defenders and to render left-of-boom defense actionable, repeatable, and assessable. Many IOT originate from publicly or partner-accessible sources (e.g., CT logs, registrar feeds, industry-sharing streams, open-source intelligence), allowing for monitoring at a relatively low marginal cost. Juxtaposing IOT timestamp data with the initial in-network artifacts detected by telemetry can measure the efficacy of triggers, assess the lead time achieved, and determine whether related preventive measures reduced subsequent alarms, losses, or customer dissatisfaction. Organizations can enhance cyber resilience by combining outward-facing environmental scanning with kill-chain reasoning—Contextual Anticipation—to address the shortcomings of conventional post-delivery controls.

This research enhances kill-chain theory and practice in four distinct ways. Initially, it establishes CKC-0: Contextual Anticipation as a novel phase that precedes reconnaissance, featuring explicit semantics and interfaces for subsequent CKC stages, thereby integrating with current SOC/CTI pipelines [1]. Secondly, it delineates a STEMPLES+-guided GMA methodology that transforms ambiguous contexts into IOT and associates each indicator with proactive measures, offering a replicable, domain-independent design framework for “left-of-boom” defense [3,4,5]. Third, it provides an assessment process for prechain efficacy—evaluating lead time acquired, watchlist coverage of subsequent incidents, and the precision/actionability of interventions—thus facilitating comparative analyses across sectors [12]. Fourth, through representative cases, it illustrates that institutionalizing IOT provides earlier, operationally beneficial warnings compared to traditional post-delivery controls, thereby reconceptualizing CKC-aligned defense as a socio-technical, anticipatory stance rather than merely an intra-network sequence [1].

2. Related Works

Research on modeling multi-stage incursions has been focused on the CKC, which organizes the progression of attacks as a sequential framework and has been adapted across several sectors and tool ecosystems. Recent syntheses examine how AI expedites and transforms adversarial behavior at every stage, advocating for preemptive guardrails that precede traditional reconnaissance [1]. A parallel stream provides socio-technical critiques of “kill chain thinking,” highlighting its tendency to focus on existing telemetry while neglecting previous, extrinsic dynamics [2]. These factors collectively encourage expanding the analytical timeframe prior to reconnaissance—specifically the gap addressed by our Contextual Anticipation phase.

2.1. Variants of the Kill Chain and Related Frameworks

Numerous studies modify CKC to specific circumstances or hazards instead of altering its temporal parameters. In multimedia service contexts, Kim et al. reformulate stage semantics to address challenges in content distribution and service composition, while maintaining the reconnaissance-first approach [13]. APT-Dt-KC integrates CKC with machine-learning classifiers and fuzzy scoring to identify APT stages, presuming that the sequence initiates with reconnaissance [14]. Ahmed et al. conduct a data-driven analysis linking visible telemetry to CKC phases in distributed companies, although they primarily focus on post-intrusion artifacts [15]. These versions collectively enhance coverage within or next to conventional stages; nevertheless, none establishes a discrete pre-reconnaissance context phase or ties it with governance and policy mechanisms—the fundamental aspect of Contextual Anticipation.

2.2. Preliminary Alerts from External Infrastructure Indicators

A significant body of empirical research indicates that attacker infrastructure leaves discernible traces before payload delivery or exploitation. Longitudinal investigations of typosquatting reveal domain-registration trends that occur before content distribution and persist for months, offering a viable lead time for targeted countermeasures [8]. Combosquatting research utilizing extensive passive and active DNS datasets demonstrates prolonged lives and sector-specific exploitation that can be analyzed upstream [16]. Recently, CT and passive DNS telemetry have been integrated to identify suspicious domains before publication of web content, demonstrating that issuance flows can serve as early indicators. These efforts collectively demonstrate that external infrastructure traces are actionable before CKC delivery or exploitation, directly coinciding with Contextual Anticipation’s focus on IOT watchlists sourced from publicly or partner-accessible feeds.

2.3. Threat Intelligence Derived from Internet Discussions and Illicit Ecosystems

In addition to infrastructure, researchers analyze online discourse—such as dark-web forums, security blogs, and social media—to generate early threat alerts. Sapienza et al. demonstrate systems that produce precise alerts by monitoring conversations among actors and experts, indicating that linguistic signals about campaigns and tools emerge before extensive exploitation [17,18]. That aligns with Contextual Anticipation but does not clarify how to systematize and operationalize such signals within a kill-chain-compatible framework. Our research tackles this by considering these sources as factor inputs within a morphological framework and by linking outputs to proactive strategies.

2.4. CaaS as a Macro-Signal

The professionalization of CaaS marketplaces has been recorded in academic surveys and comprehensive European threat assessments. Sood and Enbody elucidate commoditized services such as kits, botnets, and access brokers, together with their pricing and availability dynamics—providing a macro-context that can be observed as a capacity signal for specific TTPs [10]. Europol’s IOCTA Spotlight further demonstrates the modularity and interdependence of criminal services, emphasizing how market fluctuations and supplier ecosystems influence attack opportunities [11]. These sources substantiate the concept of Contextual Anticipation: market-level observables serve as valid early indicators and potential policy instruments (registrar/payment standards), rather than mere background noise.

2.5. Subtle Indicators and Foresight Analysis

The conceptual foundation for treating IOT as anticipatory cues derives from established weak-signal theory in futures studies. Ansoff’s early formulation positions weak signals as low-intensity, ambiguous precursors of emerging discontinuities, while later refinements have provided systematic mechanisms for interpreting such cues. Hiltunen’s “future sign” model (signal–issue–interpretation) explains how initially obscure environmental anomalies acquire decision-making relevance through structured interpretation [6]. Holopainen and Toivonen extend this perspective by emphasizing organizational mechanisms capable of detecting and explaining early-stage discontinuities across socio-cultural and technological domains [7].

These contributions collectively underpin our approach to IOT as organized weak signals—externally observable, minimally assignable, thresholded, and explicitly linked to defensive actions. To situate the IOT framework within this theoretical landscape, Table 1 summarizes key weak-signal theories and clarifies their relevance for anticipatory cyber-threat analysis.

Table 1.

Overview of Selected Weak-Signal Theories and Their Relevance to IOT.

Collectively, these weak-signal theories elucidate the rationale for converting confusing contextual signals into organized IOT. This study emphasizes three methodological principles. (1) Preliminary anomalies can yield decision-relevant insights while being imperfect; (2) cross-domain interactions frequently offer greater predictive power than isolated variable signals; and (3) structured sense-making frameworks are essential to mitigate the impact of noise on early-warning analysis.

The IOT framework actualizes these ideas by incorporating socio-technical scanning, morphological structure, and threshold-based escalation to transform weak external information into cohesive anticipatory intelligence.

2.6. Morphological Analysis as a Method of Structuring

GMA offers a systematic method for structuring multidimensional problem spaces, examining coherent combinations, and preventing categorical errors [5]. Johansen elucidates how morphological scenario modeling delineates a comprehensive solution space and produces mutually exclusive scenario categories [4]. Security research often employs informal morphological reasoning (e.g., red-team “attack trees”), but there is a scarcity of studies that clearly link a STEMPLES+ scan to a morphological matrix to inform operational watchlists and pre-delivery actions. Our work establishes GMA as the cohesive mechanism linking contextual analysis with kill-chain-aligned actions.

2.7. Resilience Engineering and Preemptive Governance

Cyber-resilience engineering reconceptualizes protection as anticipate–withstand–recover–adapt, incorporating technical and organizational controls throughout the system lifespan. NIST SP 800-160 Vol. 2 Rev. 1 delineates strategies such as constrain, preclude, and prepare, which are inherently activated by upstream signals—specifically the governance mechanisms that Contextual Anticipation engages (registrar actions, supplier hardening, targeted communications) [12]. Previous research frequently conceptualizes CKC as a technical pipeline (sensors → analytics → reaction); however, resilience guidance substantiates the idea that policy and procurement can become elements of the pre-delivery defensive framework when informed by systematic external indicators.

2.8. Syntheses of IOT Security as a Contextual Framework

While not our primary focus, thorough IOT security assessments highlight how deployment schedules, certification processes, and supply-chain dependencies establish contextual opportunities for adversaries, hence facilitating preemptive measures [22]. These surveys underscore the importance of identifying context-level triggers and aligning them with sector-specific watchlists; under our system, these triggers are categorized as IOT entries, with adjustable thresholds and playbooks tailored to the domain.

2.9. Where Contemporary Literature Is Deficient

Three persistent gaps are evident across these streams:

- Temporal scope: CKC variants generally optimize within or adjacent to classical stages; even when employing machine learning or hybrid signals, they seldom model a separate pre-reconnaissance phase with formal interfaces to subsequent stages [13,14].

- Integration of methods: Early-warning systems identify signal sources (domain/CT dynamics, online conversations), yet they fail to integrate them into a reproducible, auditable, kill-chain-compatible organizing methodology that produces outputs (watchlists, thresholds, courses of action). GMA offers the requisite structuring capability but is underutilized in cybersecurity [4,5].

- Governance coupling: Resilience guidance advocates for proactive measures, yet the majority of implementations are reactive and focused on security teams; the literature inadequately specifies how legal, communications, or procurement functions can be activated by contextual signals to increase costs for attackers at an earlier stage [12].

Our research addresses these deficiencies by: (i) formalizing CKC-0: Contextual Anticipation, a phase situated explicitly prior to reconnaissance; (ii) employing STEMPLES+-guided GMA to convert diffuse context into IOT that are observable, thresholded, and linked to pre-emptive measures; and (iii) delineating an evaluation protocol for prechain efficacy (lead-time acquired; watchlist coverage of subsequent incidents; intervention accuracy), facilitating comparative analyses across sectors [1,3,12]. We redefine kill-chain practice as an anticipatory, socio-technical approach that complements, rather than supplants, downstream detection and response.

3. Methods

In the present study, a foresight-oriented methodological approach was adopted to anticipate contextual precursors of cyber-attacks prior to stages conventionally addressed by reconnaissance. The methodology was structured around a multidimensional scanning framework, operationalized through GMA, enabling the systematic exploration of combinatorial possibilities while eliminating implausible configurations. The application of GMA has been well documented in futures studies and scenario development, and it is particularly suited to complex, non-quantifiable problem domains [3,23]. Moreover, the integration of scanning techniques into cybersecurity foresight has been demonstrated in the recent literature, underscoring the utility of early-detection mechanisms grounded in contextual threat intelligence [24].

3.1. Research Design

A qualitative research design grounded in futures studies and foresight analysis was employed to explore the conditions under which early contextual signals can be systematically translated into actionable threat indicators. The design was structured around a pre-chain extension of the CKC, positioning anticipatory intelligence activities before reconnaissance. This approach reflects recent critiques of CKC’s linearity and its limited coverage of external, pre-intrusion dynamics, which have motivated the development of extended frameworks incorporating earlier intervention opportunities [2]. To operationalize these concepts, STEMPLES+ scanning was applied as a multidimensional framework for mapping socio-technical drivers, offering broader coverage than classical PESTLE variants in cybersecurity contexts [25]. The identified drivers were subsequently organized using GMA, a well-established method in futures research for structuring complex problem spaces and identifying internally consistent scenarios [3,20]. Within this design, contextual outputs were translated into IOT, defined as observable, threshold-based signals linked to pre-emptive actions.

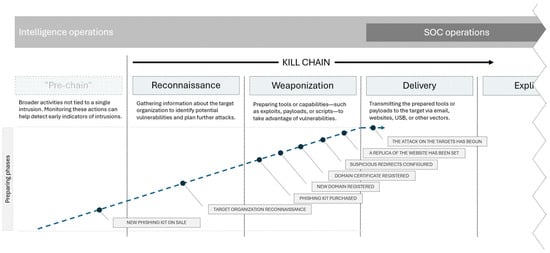

To illustrate the positioning of this pre-chain methodology within cyber-defense operations, Figure 1 depicts how intelligence operations were conceptualized as preceding and complementing traditional SOC operations, thereby expanding the intervention window prior to delivery or exploitation.

Figure 1.

Positioning of the proposed Pre-Chain phase within an extended Cyber Kill Chain, illustrating intelligence-led early indicators prior to reconnaissance.

The grey region on the left denotes the suggested Pre-Chain phase, situated within intelligence operations and preceding conventional Cyber Kill Chain stages. This phase includes extensive, context-oriented operations that are not linked to a specific incursion, facilitating the detection of preliminary, externally visible signs of threat actor readiness. The blue dotted line depicts the gradual development of an attack, emphasising that potential indicators—such as the availability of phishing kits, domain registration, and certificate issuance—arise before the Reconnaissance phase, thereby extending the defender’s opportunity for intervention beyond traditional SOC-focused detection.

Intelligence operations are depicted as preceding traditional SOC activities, enabling the identification of contextual IOT before reconnaissance. The diagram illustrates how preparatory phases, such as the emergence of phishing kits or domain registrations, can be systematically monitored to expand the defender’s intervention window prior to delivery or exploitation.

3.2. Analytical Framework: STEMPLES+

A comparative evaluation was conducted of several scanning and environmental analysis frameworks to determine their effectiveness in identifying anticipatory cyber threat drivers. The evaluated frameworks encompassed PESTLE/PESTEL (Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental, Legal), STEEPLE (incorporating an Ethical dimension), the NIST Cybersecurity Framework (CSF), PMESII-PT (Political, Military, Economic, Social, Information, Infrastructure, Physical Environment, Time), and STEMPLES+ (Social, Technical, Economic, Military, Political, Legal/Legislative, Education, Security, alongside supplementary cultural, demographic, and psychological indicators).

PESTEL and STEEPLE frameworks are well-established for their extensive strategic analysis capabilities in various commercial contexts, including applications in cybersecurity foresight and open-source intelligence research [4]. Nonetheless, its conceptual simplicity constrains the integration of security-critical or adversary-centric dimensions—specifically Military, Security, and Psychological factors—which are vital for anticipatory modeling of pre-intrusion behavior.

The NIST CSF provides systematic recommendations for managing cybersecurity risks, particularly within business risk management frameworks. Notwithstanding this strength, the CSF has been evaluated as inadequate for horizon-scanning socio-political factors and the emergence of early-stage threats, as its focus is on mitigation and governance rather than contextual foresight.

The PMESII-PT framework, which encompasses socio-technical aspects, is extensively utilized in intelligence and military planning. The incorporation of Political, Military, Information, and Infrastructure aspects renders it suitable for comprehensive environmental evaluations; nonetheless, PMESII-PT is tailored for state-level operational contexts rather than organizational cyber-anticipation. It fails to adequately encompass micro-contextual dynamics—such as clandestine market indicators, regulatory transition periods, or psychological and behavioral changes—that are frequently leveraged in contemporary cyber operations.

Conversely, the STEMPLES+ framework was recognized as the most comprehensive and methodologically suitable basis for this investigation. It incorporates essential socio-technical and threat-related factors and is now used by intelligence communities to monitor driver-based changes [26]. Furthermore, the adaptability of the “+” component facilitates the integration of cultural, demographic, and psychological variables, hence enhancing the modeling of subtle signals that precede cyber-attacks. Consequently, STEMPLES+ was chosen as the analytical framework for anticipatory scanning in this study, effectively balancing comprehensive coverage with the operational specificity required to produce IOT.

As illustrated in Table 2, STEMPLES+ extends beyond conventional frameworks by systematically integrating dimensions directly relevant to the cyber domain, including military activities, security operations, and socio-psychological dynamics. This broader coverage ensures that drivers that often precede malicious cyber activity—such as regulatory change, geopolitical instability, or public sentiment shifts—are not excluded from analysis. In addition, the adaptability of the “plus” component allows the framework to capture emerging contextual variables, such as cultural or religious narratives, that may become relevant in specific threat landscapes. This adaptability has led to its adoption and refinement within cyber-intelligence practice, where it has been operationalized for monitoring indicators of change across multiple dimensions [26]. Consequently, STEMPLES+ was selected as the analytical foundation for this study, and its domains are detailed in the following section.

Table 2.

Comparative analysis of selected frameworks.

Building upon the comparative analysis, each dimension of the STEMPLES+ framework was adapted to the cyber landscape to ensure relevance for anticipatory threat analysis. The adaptation follows prior work in strategic foresight, where multidimensional frameworks are adjusted to reflect domain-specific dynamics [4,5]. In the cybersecurity context, the inclusion of dimensions such as Security, Military, and Psychological reflects operational realities where defense capabilities, geopolitical conflicts, and public perception shape adversarial activities. The Treadstone adaptation of STEMPLES+ further illustrates how classical dimensions can be extended to incorporate cultural and demographic factors, enhancing the ability to detect weak signals of impending threats [26]. A structured overview of each dimension and its operational meaning is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Detailed description of STEMPLES+ dimensions adapted to the cyber landscape.

While STEMPLES+ offers extensive coverage of socio-technical domains and has proven adaptable to cybersecurity contexts, it is not without methodological challenges. The primary advantage lies in its breadth: by systematically incorporating social, political, military, and psychological factors, the framework prevents a narrow focus on purely technical signals and instead facilitates multidimensional foresight. This holistic scope enables the early detection of weak signals and contextual IOTs that might otherwise remain undetected until adversarial activity reaches the organizational perimeter [6]. Moreover, the flexibility of the “+” dimension enables continuous adaptation to evolving environments, thereby enhancing resilience against emerging threats [7].

However, the comprehensiveness of STEMPLES+ also introduces complexity. Analytical exercises often require larger, interdisciplinary teams to ensure that all dimensions are appropriately covered, which may not be feasible in organizations with limited resources [5]. In addition, the extensive number of dimensions can lead to over-complexity in scenario building, potentially slowing down decision-making in time-sensitive environments. These limitations necessitate careful calibration of the framework, balancing breadth of coverage with operational practicality. A structured summary of advantages and limitations is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

Advantages and Limitations of STEMPLES+.

As summarized in Table 4, the STEMPLES+ framework provides a robust foundation for cybersecurity horizon scanning, balancing comprehensive coverage with the practical challenges of implementation. Its multidimensional nature ensures that weak signals can be captured across diverse societal and technological domains, while its adaptability enables the incorporation of emerging factors as threat landscapes evolve. At the same time, the need for interdisciplinary expertise and the potential for over-complexity underline the importance of structured facilitation in its application. To address these challenges and to operationalize the framework, a systematic data elicitation process was employed, combining expert creative thinking techniques with scenario analysis. The following section outlines how contextual drivers were identified and structured to generate scenarios that could later be transformed into IOT.

3.3. Data Elicitation and Brainstorming Process

To operationalize the STEMPLES+ framework in the context of anticipatory cyber-threat analysis, structured brainstorming workshops were conducted to elicit relevant contextual drivers. Brainstorming has long been recognized as an effective tool in foresight and scenario analysis, particularly when supported by structured facilitation and cross-disciplinary participation [5]. Within this study, participants were deliberately drawn from diverse professional backgrounds to mitigate disciplinary bias and ensure that social, economic, political, and technological perspectives were equally represented.

The process was guided by a set of framing questions that structured the discussion. The primary question (What?) sought to identify potential events or developments that could serve as incentives for adversaries to initiate attacks. That was followed by secondary probes (Why?, How?, When?) aimed at clarifying adversarial motivations, attack modalities, and temporal opportunities. These probes enabled the group to map contextual events into coherent pathways that adversaries might exploit. Comparable approaches have been successfully applied in strategic intelligence contexts, where scenario analysis methods are used to stimulate creative yet structured scenario generation [7].

The workshops produced a set of structured driver–incentive mappings that show how specific socio-technical developments can enable cyber-attacks. Examples included regulatory changes that create transitional uncertainty, technological rollouts that expose adoption-phase vulnerabilities, and socio-economic crises that adversaries could exploit through fraudulent narratives. These outputs formed the empirical foundation for the subsequent morphological structuring process, ensuring that scenario construction was both comprehensive and grounded in systematically elicited contextual knowledge.

3.4. Structuring with GMA

Following the identification of contextual factors, GMA was used to organize the problem area and to develop internally coherent scenarios methodically. GMA is a qualitative modeling approach that investigates intricate, multidimensional systems by analyzing all potential configurations of essential components and excluding those that are logically contradictory [23]. Its appropriateness for scenario analysis has been consistently validated, especially in fields where causal models are deficient, and ambiguity is prevalent [4].

This study developed a morphological matrix by intersecting three sets of dimensions: (i) initial contact channels (e.g., email, SMS, social media, telephony, physical correspondence), (ii) execution platforms (e.g., malicious websites, mobile applications, credential-harvesting scripts, fraudulent investment portals), and (iii) facilitating contextual conditions (e.g., regulatory deadlines, financial crises, public-sector reforms, high-profile brand events). Each parameter was defined as a limited range of distinct value alternatives based on empirical observations, CTI reporting, and socio-technical weak-signal literature. The integration of these aspects generated an extensive solution space of feasible assault combinations, each illustrating a distinct pathway through which contextual elements may converge to facilitate adversarial opportunities.

The enhancement of methodological openness involved removing incongruous or implausible combinations based on stated cross-consistency criteria rather than subjective assessment. A pairing was eliminated upon the fulfillment of one or more of the subsequent conditions: (i) logical impossibility—configurations that cannot coexist due to physical, temporal, or operational constraints; (ii) empirical contradiction—combinations not observed in historical CTI datasets despite high detectability, indicating structural implausibility; (iii) causal incoherence—parameter interactions that contradict established causal directions in cyber-operations; and (iv) scenario non-viability—configurations incapable of generating actionable threat pathways. The evaluations were performed separately by two analysts, and only combinations disapproved by both reviewers were discarded, thus minimizing subjectivity and enhancing reproducibility. The remaining cross-consistent designs formed the diminished morphological solution space.

Comparable implementations of GMA in cybersecurity foresight have demonstrated its capacity to organize early warning indicators and amalgamate diverse data sources into cohesive anticipatory models [5]. Consistent with this procedure, the morphological structuring results were subsequently categorized according to the STEMPLES+ dimensions. That guaranteed that each scenario pathway was anchored in socio-technical facts that attackers could feasibly exploit. Table 5 provides a systematic summary of attacker motivations across STEMPLES+ categories, outlining potential triggers, the rationale for their opportunistic nature, practical implementation methods, and the timing of exploitation likelihood. This mapping connects abstract contextual drivers to the eventual creation of IOTs, providing a clear, replicable basis for anticipatory monitoring.

Table 5.

STEMPLES+ attacker incentives by dimension.

The integration of STEMPLES+ elicitation and GMA structuring yielded a transparent set of scenario pathways that highlight plausible attacker incentives and the corresponding contextual conditions. By documenting these incentives in tabular form and filtering them through morphological consistency checks, a structured foundation was established to anticipate potential attack vectors before they manifest in the operational environment. The next step involved translating these scenario pathways into concrete IOTs, each defined by observable sources, thresholds, and associated courses of action. This operationalization ensures that abstract foresight analysis can be directly linked to actionable early-warning mechanisms within cybersecurity practice.

3.5. Operationalization into IOT

The final step of the methodological framework involved translating the morphological matrix’s scenario outputs into structured IOTs. Each IOT was defined according to four parameters: (i) the observable source from which the signal can be monitored, (ii) the heuristic or query used to extract relevant information, (iii) the threshold at which the signal becomes actionable, and (iv) the prescribed course of action aligned with organizational response capabilities. This structuring ensured that each contextual driver was directly linked to operational monitoring practices, thus bridging the gap between strategic foresight and day-to-day defensive operations [8].

To enhance consistency and reduce reliance on qualitative assessment, each IOT can be calibrated using quantitative thresholds derived from historical data and descriptive statistics. In practice, contextual indicators such as domain registrations, certificate issuances, social media mentions, or Dark Web advertisements exhibit distinct baselines that can be modeled using basic statistical parameters. Table 6 presents exemplary threshold formulations derived from (i) moving averages, (ii) deviations from mean activity, and (iii) anomaly-detection heuristics.

Table 6.

Example quantitative thresholds for IOT activation.

Fundamental descriptive statistics offer a clear foundation. For instance, if the daily number of domain registrations for brand-related variations has a mean (μ) of 2.3 registrations per day and a standard deviation (σ) of 1.1 for 90 days, an operational IOT threshold can be established at μ + 2σ = 4.5 registrations. Any day with five or more registrations will be considered a signal necessitating escalation. Correspondingly, Certificate Transparency (CT) issuance trends for brand-associated hostnames can be established using seven-day or fourteen-day moving averages, enabling the identification of relative spikes when they surpass 150–200% of baseline activity.

Anomaly scoring for category- or low-frequency contextual signals (e.g., Dark Web ads, code template reuse, abrupt reactivation of inactive domains) can be calculated using frequency-of-change metrics or moving-window counts. In cases of irregular distributions, non-parametric approaches such as median absolute deviation (MAD) or quantile-based thresholding offer robust alternatives that do not presuppose normality. These methodologies improve consistency and repeatability by anchoring threshold activation to observable data patterns instead of relying solely on qualitative expert evaluations.

Table 6 presents these examples by showcasing representative IOT types, their corresponding data sources, and a reproducible statistical threshold.

The quantitative factors do not supplant qualitative expertise; instead, they enhance analyst judgment by providing standardized, verifiable measures that enhance methodological transparency. Integrating descriptive statistics into IOT calibration guarantees that contextual signals are comparable across enterprises and more readily amenable to retrospective analysis.

For example, a bank merger scenario was operationalized in IOT by defining the following: observable sources, such as CT logs and domain-registration feeds; heuristics, including brand-combination queries; thresholds for sudden surges relative to baseline levels; and actions, including registrar escalation or pre-emptive client communication. Similarly, scenarios of mobile banking app updates were translated into IOT by monitoring app-store telemetry, update-related smishing patterns, and developer-account anomalies [9]. By applying this systematic approach across all filtered scenarios, a replicable watchlist of IOT was generated.

The IOT framework draws conceptually from weak-signal theory, in which ambiguous early cues are transformed into structured decision-making inputs [6,7]. Within cybersecurity, this approach advances beyond descriptive situational awareness by linking signals to concrete triggers for action. As a result, IOT provides a measurable and auditable mechanism for anticipatory defense: timestamps of IOT alerts can be compared with subsequent in-network detections to assess the lead time gained, the coverage of attack vectors, and the accuracy of interventions.

In practice, many IOTs can be monitored at relatively low cost through publicly accessible data streams, such as CT logs, passive DNS telemetry, registrar feeds, and open-source intelligence sharing communities. Their implementation requires collaboration among security operations, threat intelligence analysts, and governance teams, as different courses of action often extend beyond technical controls to include legal, procurement, and communication functions. By embedding IOT into the organizational monitoring cycle, Contextual Anticipation was rendered actionable, transforming abstract foresight into a structured, pre-reconnaissance defense capability.

The current study utilized expert opinion to establish threshold levels for the activation of individual IOT, a method that inherently includes subjective bias. To improve reproducibility and minimize analyst-dependent variability, subsequent versions of the framework will integrate quantitative threshold-setting methodologies. Proposed methodologies encompass: (i) statistical baselining utilizing historical distributions of domain registration volumes, certificate issuance frequencies, or social media engagement; (ii) deviation detection metrics, including z-scores or moving-window anomaly detection; and (iii) machine learning-assisted calibration employing unsupervised clustering or density estimation models (e.g., DBSCAN, Isolation Forest) to discern contextually anomalous signal intensities. These methods enable thresholds to be derived directly from real data rather than predetermined heuristics, thereby enhancing the robustness, transparency, and transferability of IOT implementations across corporate contexts. Integrating these quantitative additions constitutes a logical progression in advancing the suggested anticipatory-defense system.

3.6. Proposed Methodological Workflow

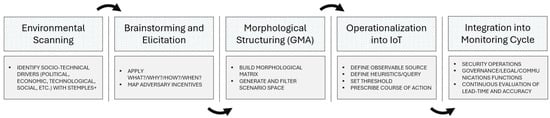

The proposed methodology follows a structured workflow designed to transform contextual drivers into actionable early-warning indicators. The process begins with environmental scanning, in which socio-technical factors are identified using the STEMPLES+ framework. These drivers are then subjected to structured brainstorming sessions to elicit potential attacker incentives and to map events through the What–Why–How–When lens. In the third stage, the drivers and incentives are formalized into a morphological matrix, where GMA is applied to generate the whole space of possible attack scenarios and filter out inconsistent combinations. The fourth stage translates these consistent scenarios into IOTs, each defined by an observable source, a heuristic, a threshold, and a course of action. Finally, the IOT is embedded within the operational monitoring cycle, serving as input for security operations, intelligence teams, and governance functions. This workflow in Figure 2 ensures that abstract foresight analysis is systematically linked to practical, auditable organizational defense mechanisms.

Figure 2.

Workflow of the proposed methodology, illustrating the sequential stages.

The methodological process, from the elicitation of contextual drivers through STEMPLES+ to their structuring with GMA and, finally, their translation into operational IOT, established a systematic and reproducible framework for anticipatory cyber defense. While the approach is theoretically robust, its practical value must be demonstrated through real-world applications. To this end, representative case studies were conducted to illustrate how the framework can be applied to ongoing socio-technical developments and how IOT can be used to generate actionable early warnings. The following section presents these case studies in detail.

Automated contextual scanning can be performed by persistently collecting pertinent data streams—such as domain registration feeds, CT logs, passive DNS telemetry, and social media API outputs—and standardizing them into a cohesive event structure. The data streams can be directed through an ingestion pipeline that performs real-time filtering, baseline computation, anomaly scoring, and signal categorization into established IOT classifications. The GMA structure phase, although fundamentally analytical, can be partially automated. Parameter configurations derived from the morphological solution space can be recorded as rule sets or pattern templates, facilitating automated assessments to determine if new contextual signals trigger any of the established pathways. That reduces the analyst’s workload and ensures consistent scenario interpretation across monitoring cycles. Ultimately, the integration with current monitoring systems—such as SOC alerting workflows—facilitates the presentation of IOT activations alongside conventional telemetry-based warnings. That enhances internal detection systems by including an external, contextually informed anticipatory layer. Over time, automated tracking of IOT triggers facilitates retrospective validation, model recalibration, and threshold refining. Although complete automation falls outside the scope of this study, these enhancements demonstrate the practical application of the suggested framework in real defensive contexts.

4. Case Studies

To demonstrate the practical applicability of the proposed methodology, a series of case studies was conducted based on real incidents analyzed in cooperation with security operations and intelligence teams. These cases illustrate situations in which the integration of STEMPLES+ scanning, morphological structuring, and the operationalization of IOT enabled the early identification of attacker incentives and, in several instances, enabled proactive measures that prevented or mitigated malicious activity. For confidentiality reasons and in accordance with non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), all identifying details such as institution names, domains, and internal procedures have been anonymized. Nevertheless, the chronological events, contextual triggers, and analytical process remain faithfully represented, thereby illustrating how the proposed framework operates in practice.

4.1. Bank X Merger

In mid-August 2024, media outlets reported that Bank X had completed the acquisition of two additional banks, consolidating their operations into a single financial group. This strategic move immediately attracted public attention and generated significant uncertainty among customers of the merged institutions. Within days of the announcement, systematic monitoring of domain registrations revealed a surge in newly registered domains combining the name of Bank X with one or both of the acquired banks. Over the subsequent weeks, this trend continued, suggesting that adversaries were preparing an infrastructure to exploit client confusion during the migration process.

The observed domains exhibited strong naming similarities, were registered in private ownership, and in some cases were rapidly deactivated after initial use. While several domains were confirmed to host fraudulent replicas of banking portals designed for credential harvesting, others remained dormant but suspiciously aligned with the bank’s brand identity. The temporal correlation between the merger announcement and the subsequent wave of registrations indicates clear adversarial intent to exploit the context of organizational consolidation.

The chronological sequence of relevant events, including the official merger announcement and subsequent domain registrations, is summarized in Table 7. The table highlights how adversarial preparations closely followed the public disclosure of the merger, providing early contextual signals that could be translated into IOTs.

Table 7.

Chronology of key events for Bank X Merger case.

The chronology in Table 7 clearly shows how the adversary’s activity escalated in the weeks following the merger announcement. A total of 22 domains were registered over three months, some of which were actively used in phishing campaigns while others remained dormant. The clustering of domain registrations around brand-related keywords provided a measurable IOT, enabling early detection and the possibility of pre-emptive action such as registrar takedowns or customer awareness campaigns.

To better illustrate how contextual signals can be translated into actionable measures, a joint operations plan was developed. This plan aligns the activities of the customer (Bank X), the intelligence department, the media, and the adversary in chronological order. Table 8 summarizes the courses of action (CoA) designed to provide early warning and mitigate the exploitation of merger-related confusion.

Table 8.

Plan of operations for early response to potential threats (Courses of Action).

As shown in Table 7, early communication between the customer and the intelligence team created a temporal advantage that extended well before the public announcement of the merger. That allowed the intelligence team to configure monitoring systems, develop keyword-based watchlists, and prepare communication strategies. Once the adversary initiated domain registrations and certificate issuances, the intelligence department was already in a position to track, verify, and act. By coordinating pre-emptive client notifications and registrar takedowns, the joint operations significantly reduced the window of opportunity for adversaries to exploit merger-related confusion.

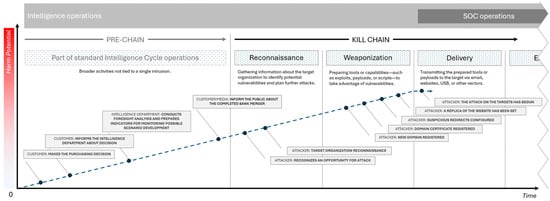

To complement the tabular overview, the sequence of events and corresponding operations was visualized on a timeline. This representation highlights the parallel activities of the customer, the intelligence department, the media, and the adversary, showing how foresight analysis and early-warning mechanisms extended the defender’s intervention window. Figure 3 provides a chronological visualization of the Bank X merger case.

Figure 3.

Timeline of significant events and corresponding actions in the Bank X merger case.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the intelligence cycle was activated before the media announcement of the merger, providing additional lead time to prepare detection mechanisms and awareness campaigns. Once the merger became public, adversarial activities escalated rapidly, including domain registrations, certificate issuance, and the eventual deployment of phishing infrastructure. The timeline demonstrates that by embedding foresight analysis and IOT watchlists into operational monitoring, defenders were able to shift intervention significantly to the left of the delivery phase in the CKC.

The Bank X merger case demonstrates how strategic corporate decisions can generate exploitable opportunities for adversaries. Large-scale organizational changes, such as mergers or acquisitions, often create transitional uncertainty among clients, which adversaries exploit through brand impersonation and credential-harvesting campaigns. The clustering of suspicious domain registrations immediately after the public announcement highlights how quickly attackers mobilize once contextual triggers emerge. Without anticipatory monitoring, these malicious preparations could remain unnoticed until phishing sites are fully operational and clients have already been targeted. The case illustrates that organizational milestones should be systematically integrated into foresight analysis, as they frequently act as catalysts for adversarial activity.

By applying foresight methods before and during the merger process, defenders detected adversarial preparations significantly earlier than traditional SOC telemetry would allow. This early detection created lead time to prepare registrar interventions, configure monitoring for fraudulent domains, and initiate preemptive client-awareness campaigns. Furthermore, translating contextual triggers—such as merger announcements—into IOT entries provided a structured, auditable mechanism for linking strategic business events to concrete defensive measures. As a result, the foresight-driven approach not only prevented large-scale exploitation but also reinforced cross-departmental coordination between security, communications, and governance functions.

4.2. Phishing Kit on the Dark Web

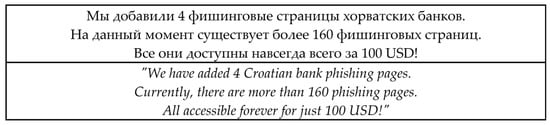

On 16 February 2025, a well-known threat actor under the alias KrakenBite published an advertisement on a Dark Web forum, offering a phishing kit with more than 160 templates for fraudulent websites. The latest version of the kit contained replicas of several Croatian banking services, thus lowering the entry barrier for adversaries by providing ready-to-use infrastructure for credential theft. In the following months, a series of phishing attacks was observed against clients of one of the targeted banks, confirming that the kit was being actively deployed.

The forensic analysis of incidents revealed substantial overlaps between the phishing pages and the kit’s advertised templates, including similarities in source code, identical email formats, and shared hosting patterns. Parallel to these confirmed attacks, intelligence monitoring detected a broader increase in suspicious domain registrations that incorporated brand names of the affected banks. However, only a subset of these registrations could be directly linked to the KrakenBite kit, illustrating the challenge of differentiating between general brand abuse and specific kit-enabled operations.

As shown in Figure 4, the advertisement explicitly highlighted the availability of local banking services and emphasized affordability, thereby lowering the barrier to entry for entry-level attackers. That not only facilitated rapid adoption of the kit but also created a surge in opportunistic campaigns that leveraged the newly available templates.

Figure 4.

Advertisement posted by the threat actor KrakenBite on a Dark Web forum.

The chronology of key events associated with this case, from the initial advertisement of the phishing kit to confirmed attacks against banking clients, is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Chronology of key events for the Phishing Kit on the Dark Web case.

Table 9 illustrates how the availability of a phishing kit on underground markets was rapidly followed by concrete exploitation against banking clients. Within less than two months of the advertisement, multiple domains were registered and subsequently weaponized for phishing attacks. The clear temporal correlation between the kit’s release and the observed incidents demonstrates how contextual monitoring of illicit markets can generate actionable IOT, enabling defenders to anticipate new waves of phishing activity before they reach end users.

To demonstrate how foresight analysis can extend the defender’s intervention window, a coordinated plan of operations was mapped out. This plan aligns the threat actor’s sequential actions with those of the intelligence team and the customer, illustrating where contextual indicators could have triggered earlier responses. Table 10 summarizes these joint operations.

Table 10.

Plan of operations for early response to phishing kit–enabled threats (Courses of Action).

As shown in Table 10, continuous monitoring of underground forums provided the first contextual signal, enabling proactive planning before the first phishing attack occurred. By integrating IOT derived from the kit advertisement—such as characteristic code templates, domain naming patterns, and certificate characteristics—intelligence teams were able to configure monitoring systems tailored to the threat. That ensured that, once adversaries began registering domains and deploying infrastructure, early-warning indicators were already in place, enabling faster detection and takedown.

The case demonstrates the critical role of illicit market monitoring in anticipatory defense. The availability of ready-to-use phishing kits significantly lowers the technical threshold for adversaries, leading to a proliferation of opportunistic attacks. Without foresight analysis, defenders are left reacting to attacks only after they reach clients. However, by linking contextual signals—such as the public sale of phishing kits—to targeted IOT watchlists, defenders can anticipate campaigns and prepare countermeasures. This anticipatory posture reduces the probability of large-scale client compromise and limits reputational damage to financial institutions.

The foresight-driven approach in this case yielded several added benefits. First, it enabled lead-time acquisition, as Dark Web monitoring contextual signals appeared weeks before the first phishing domains were weaponized. Second, it facilitated cross-team coordination, ensuring that both intelligence and customer communications were aligned. Third, it provided auditable evidence for strategic decision-making, as IOT indicators could be traced directly to the contextual driver (the KrakenBite advertisement). Collectively, these benefits illustrate how contextual monitoring of illicit ecosystems enhances the resilience of financial institutions by shifting intervention earlier in the CKC.

4.3. Wartime Donation Scams

On 24 February 2022, the Russian Federation launched a large-scale military offensive against Ukraine. In the days immediately preceding and following this escalation, a wave of fraudulent online campaigns appeared, exploiting public solidarity and willingness to donate to humanitarian causes. Intelligence monitoring revealed that multiple domains containing terms such as support, help, and donate, combined with Ukraine, were registered both before and shortly after the outbreak of hostilities. Many of these domains hosted fraudulent donation websites, some of which were amplified through social media accounts to reach global audiences.

One example was the domain helpukraine.info, which had been registered initially years earlier but was reactivated on 11 February 2022—less than two weeks before the invasion—to host a fake donation platform. Other domains, such as supportukraine.today and donate-ukraine.info appeared around the start of the military operations, demonstrating precise alignment between geopolitical developments and adversarial exploitation. These campaigns were designed to capture financial contributions under the guise of humanitarian support, diverting funds from legitimate relief efforts.

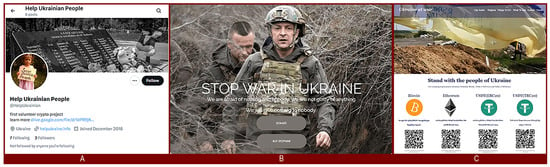

Several of the fraudulent domains used during this period were actively promoted through social media channels and hosted visually convincing donation websites. Figure 5A shows an example of a social media profile that was used to distribute links to a fraudulent domain, while Figure 5B,C illustrate the landing pages of two donation sites exploiting the Ukrainian crisis.

Figure 5.

(A)—Social media profile promoting the suspicious domain helpukraine.info shortly before the invasion of Ukraine [28]. (B)—Landing page of the fraudulent donation website supportukraine.today, registered on 22 February 2022 [29]. (C)—Landing page of the fraudulent donation website donate-ukraine.info, registered on 27 February 2022 [30].

As shown in Figure 5, the fraudulent infrastructure combined technical preparations (domain registrations) with coordinated disinformation campaigns across social media. The professional appearance of the websites, combined with emotionally charged narratives, increased the likelihood that victims would transfer funds under the assumption that they were contributing to legitimate humanitarian efforts.

The chronological sequence of domain registrations and related events associated with the Ukraine wartime donation scams is summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Chronology of key events for the wartime donation Scams case.

Table 11 demonstrates the temporal proximity between geopolitical events and fraudulent online activity. The reactivation and creation of domains designed for donation scams occurred precisely in the critical window surrounding the Russian invasion, indicating that adversaries systematically exploited public sentiment during humanitarian crises. The use of familiar words such as ‘support’ and ‘donate,’ combined with ‘Ukraine,’ served as both a lure and a legitimizing factor, allowing attackers to gain credibility and visibility rapidly.

To illustrate how anticipatory monitoring could have been applied in this case, a joint operations plan was developed. The plan aligns the actions of the adversary, the intelligence department, the customer (e.g., a financial institution or CERT), and the media, showing how contextual IOTs could have triggered preventive measures. Table 12 summarizes these courses of action.

Table 12.

Plan of operations for early response to wartime donation scams (Courses of Action).

As shown in Table 12, scenario analysis could have provided a lead-time advantage by linking geopolitical tensions with specific IOT, such as new domain registrations containing “Ukraine” combined with humanitarian keywords. That enabled continuous monitoring of both technical (domains, certificates) and social signals (media promotion, disinformation narratives). By coordinating intelligence, customer communications, and CERT-level interventions, it would have been possible to mitigate the impact of fraudulent donation campaigns even as hostilities unfolded.

The case of wartime donation scams demonstrates how geopolitical crises provide fertile ground for adversarial exploitation. Attackers systematically align fraudulent campaigns with emotionally charged events, leveraging public solidarity and urgency to maximize financial gain. The rapid registration and activation of domains with humanitarian keywords in the days surrounding the Russian invasion of Ukraine underscores the need for contextual monitoring that integrates geopolitical intelligence with cyber-threat analysis. Without anticipatory measures, large numbers of individuals risk being deceived, diverting resources away from legitimate humanitarian efforts and undermining public trust in digital donation channels.

Applying scenario analysis to this case provided three distinct benefits. First, temporal advantage: by monitoring geopolitical indicators such as military build-ups and political announcements, defenders could anticipate the emergence of fraudulent donation campaigns before they reached operational maturity. Second, contextual linkage: by correlating domain registrations with geopolitical timelines, intelligence teams could establish clear patterns that distinguished opportunistic fraud from background noise. Third, multi-stakeholder coordination: scenario analysis facilitated collaboration between intelligence departments, CERTs, financial institutions, and media outlets to launch pre-emptive awareness campaigns and technical countermeasures. Together, these benefits illustrate how anticipatory monitoring transforms crises from reactive defense challenges into opportunities for proactive protection.

4.4. Generalizability Across Threat Environments

While the three case studies focus on the financial frauds, illicit phishing services, and wartime contribution fraud, the foundational methodological framework—contextual scanning, morphological structuring, and IOT formulation—is universally applicable and easily translatable across industries. In critical infrastructure settings, contextual factors may encompass regulatory inspections, supply-chain disruptions, or geopolitical tensions impacting energy flows, which can be integrated into GMA parameters and translated into sector-specific IOT, such as irregular procurement patterns or coordinated probing activities. In the healthcare sector, contextual triggers may emerge from seasonal demand increases, pharmaceutical supply shortages, or public health announcements, which can be transformed into predictive indicators of ransomware attacks or medical record fraud. In business settings, mergers, layoffs, or significant technology implementations serve as contextual stressors that generate predictable incentives for attackers. These examples demonstrate that the framework is not contingent upon the inherent attributes of the case studies; instead, it offers a replicable analytical method that can be tailored to any sector by replacing relevant contextual factors and operational variables.

5. Results

The integration of the STEMPLES+ framework and GMA, and the operationalization of contextual outputs into IOTs, yielded empirical results demonstrating the feasibility of a pre-chain phase preceding reconnaissance. The results are presented, along with four significant findings derived from applying the methodology to real-world cases.

5.1. Structured Scenario Generation and Validation

By applying GMA to more than forty combinations derived from STEMPLES+ scanning, a reduced set of internally consistent scenarios was identified. Implausible pairings (e.g., irrelevant channels coupled with incompatible contextual conditions) were systematically excluded. The retained scenarios consistently mapped onto observable threat activity in subsequent monitoring, confirming that the foresight-driven structuring process mirrors real adversarial preparations rather than remaining a purely theoretical exercise.

5.2. Quantified Lead-Time Advantage

One of the most consistent outcomes across all case studies was the measurable temporal advantage gained through the systematic application of contextual anticipation. By juxtaposing Indicators of Threat (IOT) with subsequent in-network detections or confirmed incidents, it was possible to quantify how much earlier defenders could have intervened than with conventional Security Operations Center (SOC) telemetry.

In the Bank X merger case, suspicious domain registrations began appearing within eleven days of the official public announcement and continued for three months. Several of these domains were only activated weeks later as phishing portals. That created a precise interval of approximately 14 to 21 days in which adversarial preparations were visible but not yet operational. Had these contextual signals been systematically monitored through IOT watchlists (e.g., registrar feeds filtered by merger-related keywords), the organization would have gained sufficient time to coordinate registrar takedowns, adjust client-facing communications, and deploy targeted monitoring before the phishing infrastructure became active. The lead-time, therefore, represented not merely a detection advantage but an expanded planning horizon for governance and communication functions.

In the KrakenBite phishing kit case, the contextual signal emerged as an underground forum advertisement on 16 February 2025. The first confirmed attack against banking clients occurred on 31 March 2025, with additional attacks following in May and June. The roughly six-week gap between the initial contextual signal and the first exploitation represents a substantial anticipatory window. During this period, defenders could have extracted technical indicators from the advertised templates (such as favicon files, HTML fragments, and email structures) and configured detection systems accordingly. Unlike the merger case, where the temporal gain was measured in weeks, the illicit-market signal produced an operational lead time of more than a month, which is rare in modern cyber defense and highly valuable for orchestrating preemptive action across organizational units.

In the wartime donation scams case, the contextual trigger was geopolitical rather than organizational or market-based. Domains such as helpukraine.info were re-registered on 11 February 2022, less than two weeks before the invasion began, while others (supportukraine.today, donate-ukraine.info) appeared in the days immediately surrounding the outbreak of hostilities on 24 February 2022. That indicates a narrower window of anticipatory action—measured in days rather than weeks—but still a non-trivial one. Monitoring geopolitical signals in parallel with domain registrations containing humanitarian keywords would have allowed CERTs and financial institutions to prepare pre-emptive public advisories and to request registrar interventions at the very onset of hostilities. Although shorter in duration, this lead-time was highly sensitive, as it coincided with heightened public emotion and increased vulnerability to fraudulent narratives.

To enable a structured comparison across the three case studies, the measured temporal gains were consolidated into a comparative overview. While each case differed in its contextual triggers and operational conditions, all demonstrated that anticipatory monitoring consistently revealed adversarial preparations earlier than traditional SOC detections. Table 13 summarizes the results by aligning contextual triggers, signal types, quantified lead time, and corresponding defensive opportunities.

Table 13.

Comparative overview of quantified lead-time advantages across case studies.

The comparison reveals a gradient in temporal advantages. Organizational events such as mergers provided a medium-range window, illicit-market signals generated the most extended anticipatory interval, and geopolitical crises yielded a shorter but still actionable period. Despite these differences, the consistent presence of observable signals prior to exploitation underscores the practical utility of contextual anticipation. Embedding such monitoring into security operations would therefore transform otherwise latent preparatory phases into opportunities for proactive defense.

Across all three cases, the measured lead-time ranged from several days to six weeks, depending on the type of contextual signal. Importantly, this temporal advantage was not uniform:

- Organizational milestones (e.g., mergers) provided medium-range anticipation windows (two to three weeks).

- Illicit-market signals provided long-range anticipation windows (more than one month).

- Geopolitical crises provided short-range anticipation windows (a few days).

The consistent factor was that in each instance, contextual signals emerged measurably earlier than the first technical compromise observable by conventional SOC sensors. By capturing these signals through a structured methodology, defenders were able to move their intervention leftward in the CKC, thus transforming periods of adversarial preparation into opportunities for proactive defense.

6. Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate that contextual anticipation, operationalized through STEMPLES+, GMA, and IOTs, systematically expands the defender’s intervention window. That directly responds to critiques of the CKC that have emphasized its dependence on host-based telemetry and its limited capacity to capture pre-reconnaissance dynamics [2]. By formalizing a pre-chain phase, the findings show that adversarial preparations—whether linked to organizational milestones, illicit-market activity, or geopolitical crises—can be detected earlier and incorporated into operational workflows.

Prior research on domain registration patterns, typosquatting, and CT has shown that attacker infrastructure often emerges weeks before exploitation [8,9]. Similarly, studies on underground forums and CaaS markets identified macro-level indicators of capability development [10,11]. However, these works generally examined signals in isolation, without providing a structured methodology for connecting them to defensive measures. In contrast, this study integrates heterogeneous signal sources into a coherent analytical process that transforms contextual drivers into auditable IOT watchlists. That directly addresses observations in earlier literature that weak signals are frequently noted but rarely operationalized for security decision-making [6,7].

Variants of the CKC, such as APT-Dt-KC and other domain-specific adaptations, retained reconnaissance as the initial phase, while primarily enhancing post-intrusion classification through machine learning or sector-specific semantics [14,15]. None of these approaches redefined the temporal boundaries of the chain. The present results provide empirical evidence that a formally defined CKC-0 stage is both feasible and operationally significant. The integration of GMA into the workflow demonstrates that contextual scenario structuring can move beyond informal “attack trees” and generate reproducible scenario sets aligned with operational watchlists [4,5].

The layered nature of anticipatory signals identified in this study suggests that contextual anticipation should be conceptualized not as a uniform process but as a multi-level mechanism. Organizational triggers yielded medium-range lead times (two to three weeks), illicit-market activity created longer intervals (up to six weeks), while geopolitical crises offered shorter yet actionable lead times (several days). This stratification highlights the importance of engaging diverse stakeholders: corporate leadership for organizational events, intelligence and law enforcement for monitoring illicit markets, and national CERTs and public communication bodies for geopolitical crises.

These findings also align with resilience engineering principles, which emphasize anticipation and adaptation as critical complements to detection and response [12]. By extending the kill-chain model leftward, contextual anticipation not only strengthens the technical defense posture but also enables the activation of governance, legal, and communicational measures in advance of exploitation. The approach thus reconceptualizes CKC-based defense as a socio-technical process, reducing uncertainty and enhancing the coherence of preventive strategies across multiple organizational domains.

7. Conclusions

This study established a pre-chain phase, termed contextual anticipation, situated explicitly before reconnaissance in the CKC. By combining the STEMPLES+ framework with GMA, contextual drivers were systematically organized into internally consistent scenarios and translated into IOTs. These indicators linked weak contextual signals with threshold-based triggers and predefined courses of action, enabling their direct integration into operational monitoring.

The empirical application across three case studies demonstrated that contextual anticipation provides measurable lead-time advantages over conventional SOC telemetry. Organizational milestones produced medium-range anticipation windows, illicit-market signals generated more extended anticipation periods, and geopolitical crises yielded shorter but still actionable intervals. In all cases, contextual signals appeared earlier than in-network detections, confirming that adversarial preparations leave observable traces outside the organizational perimeter.

The study advances cyber defense practice in several respects. First, it redefines the temporal scope of the CKC by formalizing CKC-0, contextual anticipation, and offering a structured, auditable interface with downstream stages. Second, it operationalizes socio-technical scanning by transforming diffuse contextual drivers into concrete, thresholded indicators, thereby addressing the longstanding challenge of linking weak signals to actionable decision points. Third, it demonstrates that anticipatory monitoring activates not only technical measures but also governance, legal, and communication functions, expanding the range of stakeholders engaged in prevention.