Abstract

Statistical confidentiality focuses on protecting data to preserve its analytical value while preventing identity exposure, ensuring privacy and security in any system handling sensitive information. Homomorphic encryption allows computations on encrypted data without revealing it to anyone other than an owner or an authorized collector. When combined with other techniques, homomorphic encryption offers an ideal solution for ensuring statistical confidentiality. TFHE (Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus) is a fully homomorphic encryption scheme that supports efficient homomorphic operations on Booleans and integers. Building on TFHE, Zama’s Concrete project offers an open-source compiler that translates high-level Python code (version 3.9 or higher) into secure homomorphic computations. This study examines the feasibility of the Concrete compiler to perform core statistical analyses on encrypted data. We implement traditional algorithms for core statistical measures including the mean, variance, and five-point summary on encrypted datasets. Additionally, we develop a bitonic sort implementation to support the five-point summary. All implementations are executed within the Concrete framework, leveraging its built-in optimizations. Their performance is systematically evaluated by measuring circuit complexity, programmable bootstrapping count (PBS), compilation time, and execution time. We compare these results to findings from previous studies wherever possible. The results show that the complexity of sorting and statistical computations on encrypted data with the Concrete implementation of TFHE increases rapidly, and the size and range of data that can be accommodated is small for most applications. Nevertheless, this work reinforces the theoretical promise of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) for statistical analysis and highlights a clear path forward: the development of optimized, FHE-compatible algorithms.

1. Introduction

Statistical confidentiality refers to safeguarding data to ensure it remains useful for statistical analysis while minimizing the risk of identifying individuals [1,2]. It ensures that information collected for research or statistical purposes is used solely for those intended purposes and not in ways that could compromise personal privacy. Statistical confidentiality is essential for protecting the privacy and trust of individuals and organizations that provide data for research and analysis. It ensures that information collected for statistical purposes is used only in aggregate form and cannot be traced back to specific respondents. By safeguarding confidential data, researchers and institutions maintain public confidence and encourage honest participation in surveys and studies. This trust is critical because accurate and comprehensive data are the foundation of sound policy decisions, scientific progress, and social understanding. Upholding statistical confidentiality not only meets ethical and legal standards but also strengthens the integrity and credibility of statistical systems as a whole. While techniques such as encryption, access control, anonymization, and differential privacy provide some level of statistical privacy, they often have limitations [3,4]. For example, encryption and access control primarily protect data during storage and transmission but do not necessarily prevent misuse once access is granted. Anonymization can be undermined through re-identification attacks, especially when combined with external datasets. Similarly, differential privacy introduces controlled noise to safeguard individual information, but excessive noise can reduce the accuracy and utility of the data. Therefore, ensuring true statistical confidentiality requires a balanced approach that integrates multiple protective methods, continuous risk assessment, and a strong ethical and legal framework to adapt to evolving privacy threats and analytical needs.

Statistical confidentiality is a central concern in the operations of the US Census Bureau [5]. This is true for its counterparts all over the world as well as other institutions that deal with data collected from users [1,6,7]. The US Census Bureau, in 2020, emphasized the limitations of the traditional methods to protect the privacy of users and introduced differential privacy to quantify the level of privacy that is provided with various methods [8]. For the 2030 census, the Census Bureau has published a research agenda to identify improvements to the current disclosure avoidance methods. According to the planning and development timeline published on their website, after a two-year research, feedback, and development phase, the final system will be selected in 2027–2028 to get ready for production in the next census year of 2030 [9].

Homomorphic encryption (HE) has emerged as a transformative technique in privacy-preserving computation allowing mathematical operations on encrypted data without decryption. This capability is particularly valuable in fields requiring secure data processing, such as statistical analysis of sensitive information, cloud computing, and artificial intelligence. Unlike traditional mechanisms for confidentiality where the focus is on hiding the association between the data points and users, HE hides the plaintext data itself. As such, it is a powerful tool to protect not just the associations or relations between data points, but the data itself. Combined with other protection mechanisms such as strong access control, HE can provide ultimate security of data not only at rest and in transit but also in use. With statistical confidentiality becoming increasingly critical with the data-centric world we live in, this is a great time to explore the viability of homomorphic encryption for statistical confidentiality for various use cases. Two major challenges of homomorphic encryption are the computational intensity of operations resulting in high time complexity and the difficulty of adapting traditional algorithms designed for plaintext data, to operate on encrypted data. Sorting is one such example.

This study explores the use Zama’s Concrete compiler [10], which implements Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus (TFHE) [11] to perform core statistical computations including mean, variance, and five-point summary on encrypted data. It evaluates circuit complexity, programmable bootstrapping count, compilation, and execution times on GPU-enabled configuration. The research also examines encrypted data sorting for five-point summary calculation and compares Zama’s built-in comparison strategies to determine the most efficient approach.

The paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides background information on homomorphic encryption and Zama’s Concrete compiler. Section 3 summarizes the literature on the use of homomorphic encryption for statistical computations. Section 4 describes the proposed methodology while Section 5 details the implementation process. Section 6 reports experimental results and Section 7 concludes the paper with a discussion of the findings and potential directions for future work.

2. Background

Homomorphic encryption (HE) allows computations on encrypted data without revealing it to anyone other than an owner or an authorized collector. When combined with other techniques, homomorphic encryption offers an ideal solution for ensuring statistical confidentiality.

HE schemes are categorized into three families based on the main operations they involve and how they achieve homomorphic encryption: Partially Homomorphic Encryption (PHE), Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption (SWHE) and Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE). PHE schemes allow only one type of operation with no limits on the number of times the operation can be performed. PHE schemes support evaluation of either addition or multiplication, but not both. SWHE schemes allow both addition and multiplication with a limit on the number of operations that can be carried out. FHE schemes allow computations with no bounds on the type of operations and number of times they are performed.

The first FHE scheme was proposed by Craig Gentry in 2009 [12]. His work not only introduced a specific FHE construction but also established a general framework for designing new homomorphic encryption schemes. Building on Gentry’s foundational research, several subsequent schemes have been developed to improve efficiency, practicality, and security. Among the most prominent are the CKKS (Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song) scheme which supports approximate arithmetic on real and complex numbers [13]; the BFV (Brakerski, Fan, and Vercauteren) and the BGV (Brakerski–Gentry–Vaikuntanathan) schemes which enable exact computations over integers and flexible trade-offs between efficiency and noise management, respectively [14].

A major leap forward came with the work of Chillotti, Gama, Georgieva, and Izabachène in 2016 who introduced a method for bootstrapping in under 0.1 s [15]. Their approach reimagined FHE in the context of Boolean logic, focusing on evaluating one logic gate at a time rather than full arithmetic circuits. By leveraging a representation of ciphertexts over the torus (real numbers mod 1), they achieved a dramatic speedup, making homomorphic operations viable for real-time applications.

Building on this, the same team formalized and refined their method in the “TFHE: Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus” paper [11]. This work presented a complete, well-optimized system for fast homomorphic encryption over the torus, including security proofs and performance benchmarks. Following this, an open-source library was released that made TFHE one of the most practical FHE schemes available, particularly for applications involving encrypted decision-making and control flow. For an excellent overview of TFHE, we refer the reader to the 2023 thesis by Paolo Tassoni [16].

Zama is a French cryptography company that specializes in building open-source homomorphic encryption solutions with a focus on development of applications in the field of Artificial Intelligence and Blockchain [17]. It aims to simplify the use of homomorphic encryption for developers and helps with the “complexity of FHE operations, managing noise, choosing appropriate crypto parameters, and finding the best set and order of operations for a specific computation” [16].

The core product of Zama is a compiler called Concrete written in C++ and developed with Multi-Level Intermediate Representation (MLIR), an open-source project for building reusable and extensible compiler infrastructure [18]. In April 2023, Zama released a version of Concrete that converts Python programs (version 3.9 or higher) into their FHE equivalents. The conversion process includes representing each function as a “circuit”, a direct acyclic graph of operations on variables, where each variable can be encrypted or in plaintext. The circuit is compiled with parameters producing a dynamic library with FHE operations and a JSON file with the cryptographic configuration called Client Specs. The circuit can perform the homomorphic evaluation of the desired function, and these operations can be used in the context of a client–server interaction model.

Concrete integrates the optimization framework by Bergerat et al. [19] that automatically selects cryptographic parameters to balance security, correctness, and computational cost. It models FHE operations using cost and noise formulas, transforming parameter selection into an optimization problem.

Concrete analyzes all compiled circuits and calculates some statistics. Statistics are calculated in terms of basic operations. There are six basic operations in Concrete:

- Clear addition: x + y where x is encrypted and y is clear.

- Encrypted addition: x + y where both x and y are encrypted.

- Clear multiplication: x × y where x is encrypted and y is clear.

- Encrypted negation: −x where x is encrypted.

- Key switch: Conversion of a ciphertext encrypted under one key to be valid under another encryption key.

- Packing key switch: A more advanced version of key switching that also packs multiple values into one ciphertext.

- Programmable bootstrapping: building block for table lookups.

Complexity, which appears in the compilation statistics, represents the total computational cost of a circuit. It is calculated as the sum of the costs of all basic operations performed within the circuit. Among these operations, programmable bootstrapping (PBS) is the most computationally expensive component, significantly impacting overall performance. It is the building block for table lookups (TLUs). All operations except addition, subtraction, multiplication with non-encrypted values, tensor manipulation operations, and a few operations built with those primitive operations are converted to TLUs under the hood. TLUs are flexible but expensive. The exact cost depends on various variables, the hardware, and the error probability. The error probability refers to the small chance that a decrypted result is incorrect due to accumulated noise in the ciphertext. Keeping the error probability very low is crucial to ensure reliable and accurate results in fully homomorphic encryption schemes. In Concrete, the error probability can be configured through the p_error and global_p_error configuration options. The p_error is for individual TLUs but global_p_error is for the whole circuit.

In this study, we use the Concrete compiler to implement core statistical functions on encrypted datasets, including mean and variance, and sorting which allows calculation of five-point summary. For each function, we record the circuit complexity, programmable bootstrapping (PBS) count, compilation time, and execution time in a GPU-enabled environment. We test the limits of the size and range of datasets to carry out the computations for mean, variance, and sorting under the default configuration. We also test the comparison strategies provided by Zama [20] to identify the most efficient approach for encrypted sorting within the Concrete framework. To the best of our knowledge at the time of writing, such a study in the Concrete framework has not been published.

3. Related Work

Fully homomorphic encryption algorithms have been around for more than a decade and have recently evolved from a theoretical concept to a practical tool. In addition to Zama, major tech companies including Microsoft and IBM have contributed to the field. Microsoft’s SEAL (Simple Encrypted Arithmetic Library) supports both BFV and CKKS encryption schemes to enable secure arithmetic and approximate computations on encrypted data [21]. Likewise, IBM has been a major contributor in the development of HElib, a library that implements the BGV scheme [22].

In this section, we review recent studies that introduce innovative methods to improve the efficiency of arithmetic, comparison, and sorting operations; core functions underlying the statistical computations of mean, variance, and the five-point summary as implemented in our work.

The study “Homomorphic Comparison Method Based on Dynamically Polynomial Composite Approximating Sign Function” introduces a polynomial approximation method for the sign function, enabling effective comparison of encrypted values [23]. The dynamically composed polynomials adapt to the encrypted domain’s constraints, improving accuracy, and maintaining acceptable computational costs.

In “Efficient Sorting of Homomorphic Encrypted Data With k-Way Sorting Network” authors propose a scalable and parallelizable sorting mechanism using k-way sorting networks [24]. Unlike traditional binary sort networks, k-way networks reduce the number of comparisons and depth of computation, making them well suited for homomorphic environments. The method is compatible with leveled homomorphic encryption schemes, optimizing both depth and ciphertext noise. Experimental results show significant performance gains compared to earlier sorting methods in HE, particularly in terms of latency and computational overhead.

The paper “Innovative Homomorphic Sorting of Environmental Data in Area Monitoring Wireless Sensor Networks” explores a practical application of HE in wireless sensor networks (WSNs) for environmental data monitoring [25]. The authors employ an additive homomorphic encryption scheme to enable secure sorting of sensor data without compromising data confidentiality. Their approach integrates a modified bubble sort algorithm that operates directly on ciphertexts, optimized for low-power devices in WSNs. The results demonstrate a feasible balance between computational efficiency and data security, showcasing the potential of HE in real-time environmental analytics.

In “An Efficient Fully Homomorphic Encryption Sorting Algorithm Using Addition Over TFHE”, the authors leverage the TFHE scheme’s capabilities, particularly its fast gate bootstrapping and efficient binary circuit evaluation [26]. They design a sorting algorithm that primarily uses addition operations to minimize expensive multiplications. The approach is tailored for the TFHE framework, which supports bit-level operations efficiently.

The 2024 paper “Practical solutions in fully homomorphic encryption: a survey analyzing existing acceleration methods” systematically compares and analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of FHE acceleration schemes [27]. The authors classify existing acceleration schemes from algorithmic and hardware perspectives and propose evaluation metrics to conduct a detailed comparison of various methods.

Lu et al. introduce PEGASUS, a system that makes homomorphic encryption more practical for real applications. Traditional HE schemes either handle arithmetic operations efficiently (e.g., CKKS) or allow arbitrary Boolean computations (e.g., FHEW), but not both. PEGASUS bridges this gap by enabling seamless, decryption-free switching between CKKS and FHEW ciphertexts, combining their strengths. It uses less memory and runs much faster than previous methods. The authors show that PEGASUS can handle tasks like sigmoid, sorting, ReLU, and max-pooling efficiently, and can also be used for private decision trees and secure K-means clustering. Overall, it makes encrypted data processing faster and more practical for privacy-preserving machine learning [28].

Lee et al. propose HEaaN-STAT, a toolkit enabling privacy-preserving statistical analysis over encrypted data using CKKS. Their contributions include efficient methods for inverse and table lookup operations on encrypted values, and an encoding scheme that supports counting and contingency table construction over large datasets. HEaaN-STAT can fuse data from different security domains and supports numerical, ordinal, and categorical data types. In experiments, the authors demonstrate that HEaaN-STAT performs “hundreds to thousands of times faster” than prior approaches for generating k-percentile and contingency tables over large-scale data, while maintaining correctness and privacy. HEaaN-STAT can also compute the mean and variance of encrypted data, allowing users to perform core statistical analyses without decrypting sensitive information [29].

Mazzone et al. (2025) [30] present an efficient method for ranking, order statistics, and sorting encrypted data using the CKKS homomorphic encryption scheme. They replace traditional pairwise swap-based sorting with a re-encoding approach that enables all comparisons to be performed in parallel, reducing computation depth to a constant and greatly improving scalability. Their design computes ranks, order statistics, and sorted outputs through SIMD-based aggregation and masking, with additional handling for tied values. Experimental results show significant performance gains ranking a 128-element encrypted vector in about 5.8 s and sorting it in under 80 s, demonstrating practical encrypted sorting and analytics under CKKS [30].

Our study explores the practicality of Zama’s Concrete compiler and the impact of the speed-up strategies provided in Concrete to compute core statistical functions on encrypted data. Building on the table in [30], we provide comparison of our results with the studies in the last five years in Table 1. Even though the running environment, parameters, range of data, and algorithms are not the same in these studies, the comparison provides an insight into the progress of FHE for sorting.

Table 1.

Comparison of Previous Studies on Sorting.

4. Methodology

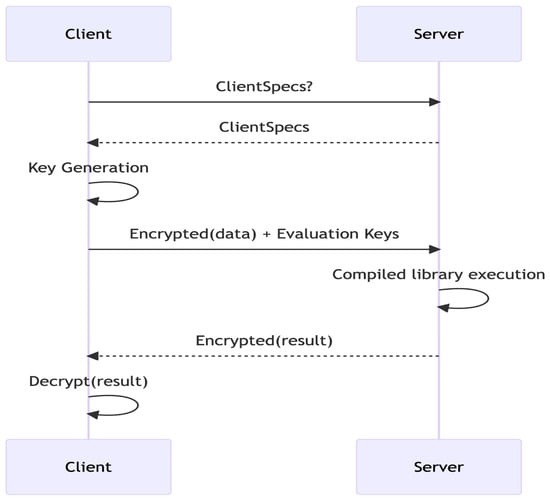

This study adopted the client–server architecture defined by Zama’s Concrete framework illustrated in Figure 1. In this architecture, the client functions as the data owner, responsible for encrypting and decrypting data, while the server performs computations on encrypted values without access to the decryption key.

Figure 1.

Typical workflow between client and server (https://www.zama.ai/post/announcing-concrete-v1-0-0 (accessed on 15 May 2025)).

In the workflow:

- The client generates and encrypts the dataset using Concrete’s encryption tools.

- The encrypted dataset is transmitted to the server for computation.

- The server performs operations including mean, variance, sorting, and five-point summary on the encrypted data.

4.1. Experimental Setup

The primary goal of the study is to evaluate the feasibility of employing the Concrete framework for performing statistical computations and explore the practical limits of dataset size and value range that can be processed efficiently. To achieve this, we collect data on computational complexity, PBS count, and the timing of both compilation and execution on the server side during the computation of each function. Because the examined functions, namely mean calculation, variance calculation, and sorting, involve distinct computational characteristics, a uniform parameter configuration is not appropriate. Instead, based on initial experimentation, we define specific dataset sizes and value ranges to be tested for each function. The datasets are randomly generated on the client side for each function. Table 2 summarizes the initial dataset sizes and ranges used for each implementation.

Table 2.

Size and range pattern for datasets per function.

All experiments are initially executed using the default configuration of Concrete which sets the global probability error, global_p_error, to . When compilation or execution errors occur, additional tests are conducted with adjustments to the probability of error parameter (p_error) to test whether the computation can be successfully completed, allowing us to determine the computational limits of the Concrete framework in our environment.

For bitonic sort, several built-in comparison strategies provided by Concrete are also evaluated to identify the most efficient approach for encrypted sorting. The strategies tested are

- Chunked

- ONE_TLU_PROMOTED

- THREE_TLU_CASTED

- TWO_TLU_BIGGER_PROMOTED_SMALLER_CASTED

- TWO_TLU_BIGGER_CASTED_SMALLER_PROMOTED

- THREE_TLU_BIGGER_CLIPPED_SMALLER_CASTED

- TWO_TLU_BIGGER_CLIPPED_SMALLER_PROMOTED

Although all strategies are tested, the observed complexity and execution times remain consistent across configurations. The best performance is achieved without applying any comparison strategy, suggesting that Concrete’s compiler likely optimizes comparison operations automatically during compilation. Therefore, these strategies are excluded from the experiments and results presented in later sections.

4.2. Security Considerations

The proposed system provides a near-complete security model by ensuring data confidentiality in transit, at rest, and in use, the last of which is rarely achieved in conventional architectures. In contrast to traditional systems that require decryption for computation, the proposed framework enables direct processing over encrypted data, thereby preserving data confidentiality throughout its entire lifecycle.

Only the data owner (client) possesses the capability to access or manipulate plaintext information. The server does not have access to the decryption key and performs all computations exclusively on ciphertexts. This design preserves end-to-end privacy and offers strong resistance to data exfiltration, even under server compromise scenarios.

Data is encrypted on the client side prior to transmission, remains encrypted during computation, and is only decrypted upon return to the client. As a result, data residing on the server is inherently protected at rest. Furthermore, the data is randomly generated on the client side and not retained within the application, minimizing residual exposure. When required, an additional layer of client-side encryption can be employed to further secure data at rest on the client device.

As revealed in the “Implementation” section, the only information accessible in plaintext to the server is the data size, which is necessary for the execution of homomorphic operations. However, this limited visibility may introduce potential side-channel risks, as adversaries could attempt to infer sensitive information from observable parameters such as ciphertext size, access frequency, or computation timing. Consequently, future work should conduct a detailed analysis of these leakage vectors and implement mitigation strategies, including time padding, operation batching, and randomized noise scheduling, to obfuscate timing and workload characteristics and further enhance the system’s resilience.

5. Implementation

The statistical functions of mean, variance, and five-point summary are implemented using Concrete version 2.11. The mean and variance calculations are implemented using the homomorphic addition and multiplication operations whereas the five-point summary is derived from the sorted data. Sorting is implemented using bitonic sort, a data-independent and parallel sorting network well suited for FHE.

To leverage GPU resources and achieve computational speedups, the implementation of each function was carefully examined for opportunities to apply vectorization. Whenever appropriate, Python’s (version 3.12) numpy library was utilized to perform vectorized operations efficiently.

A major challenge in the implementation of the functions, inherent limitations of FHE and the Concrete framework, is the lack of branching which prevents the use of conditional statements like if-else, making comparison-based algorithms such as sorting difficult to implement. In addition, Concrete only supports operations on encrypted integers and Booleans, without native support for floating-point or decimal arithmetic. This restriction prevents the direct computation of results for mean and variance, as both require division operations. In this section, we present the details of the implementations for each function.

5.1. Calculation of Mean

Mean of a dataset is calculated by dividing the sum of the data points with the size of the dataset as shown in Equation (1).

However, since Concrete does not allow division on encrypted data, only the sum of the encrypted data points is calculated in the function. We implemented the calculation of the sum using numpy’s sum function. The mean is then calculated by dividing the sum by size after decryption.

5.2. Calculation of Variance

Variance of a dataset is calculated using Equation (2):

This equation is not compatible with FHE calculations since it includes calculation of mean and therefore involves division. To overcome this limitation, we use Equation (3) which is derived in [31].

With this approach we are able to eliminate mean calculation; however, it was not possible to remove division altogether. Therefore, we are only calculating the numerator on the encrypted data. Once the result is returned, it is decrypted and divided by the denominator. We implemented the calculation of the numerator using numpy’s functions to compute the sum of squares and sum of products.

5.3. Bitonic Sort

Bitonic sort is a recursive, divide-and-conquer sorting algorithm that works by splitting the array into smaller sub arrays and arranging them in a bitonic sequence where the first half is sorted in ascending order and second half is sorted in descending order. These sequences are then merged recursively using compare and swap operations until the entire array is sorted in ascending order. One limitation of bitonic sort is that it only works when the length of array is a power of 2 since the algorithm works by splitting the array in two of each recursive step.

In traditional programming, branching allows a program to make decisions based on a condition. This kind of control flow is not possible in FHE frameworks like Concrete, because all data values, including the condition, are encrypted. Since the server performing computations never sees the plaintext, it cannot decide which branch to take based on the encrypted condition. Instead of data-dependent branching, computations in Concrete must be expressed using branchless arithmetic operations that are compatible with homomorphic evaluation. A common approach is to replace conditional logic with an equivalent algebraic form that yields the same result regardless of the data path taken. We use

where the left-hand side is the usual conditional (ternary) operation (i.e., c is the condition, t is the result if c is true, and f is the result if c is false) and the right-hand side is a mathematical reformulation of it that can be implemented without branching. The equivalence can be demonstrated as follows:

If , then Equation (4) becomes

If , then Equation (4) becomes

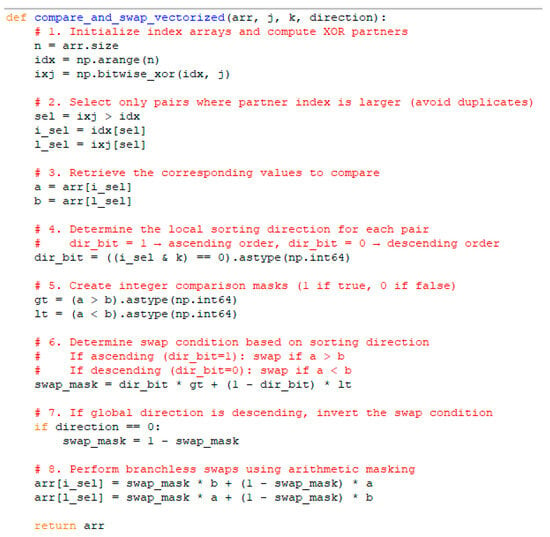

We implement the vectorized bitonic sort algorithm given in Figure 2. This implementation uses XOR-based index pairing (idx ⊕ j), which efficiently computes comparison pairs for a given stride. It uses vectorization and masking instead of branching to make operations suitable for single instruction multiple dataset (SIMD) computations which are desirable for encrypted computations.

Figure 2.

Implementation of vectorized bitonic sort algorithm.

5.4. Five-Point Summary

The five-point summary includes min, max, median, upper quantile, and lower quantile of the data. For a sorted dataset, the task of implementing the five-point summary is trivial. Once the array is sorted, min and max values are retrieved from the first and last index, respectively. To calculate the median, we return the middle element of the array if the length of the array is an odd number. If the length is an even number, we return the sum of the middle two elements. After decryption, the sum is divided by 2 which results in the median value. Since upper and lower quantiles are the medians of first and second half of a given dataset, we split the sorted array into two and calculate the median of these two halves. Since the five-point summary performance is dominated by sorting, we do not include the results of five-point summary computations in the Results section.

6. Results

The experiments were conducted on a dedicated AWS EC2 instance of type g5.4xlarge, equipped with a GPU featuring 24 GB of memory and 16 vCPUs with 64 GB of system memory. For each function, we recorded the computational complexity, PBS count, and both compilation and average execution times using predefined data sizes and ranges. Because the operations involved in calculating the mean, variance, and sorting differ substantially in their computational characteristics, the experiments could not be performed under a single unified configuration of dataset sizes and value ranges. Since the execution times remained consistent except for slightly longer durations during the initial runs, we proceeded with five runs per case and reported the average of the five runs for execution time.

All functions were executed using the default configuration and error probability settings. When computational limits were reached, compilation or execution errors occurred. When this happened, the p_error parameter was adjusted, either increased or decreased, depending on the nature of the error, to determine whether the computation could be successfully completed.

Further details and results are provided in the subsections devoted to the three computations: mean calculation, variance calculation, and sorting.

6.1. Mean Calculation Results

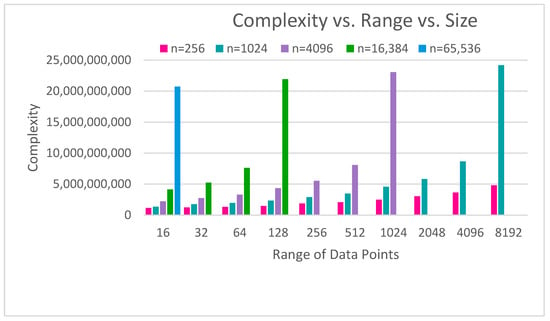

For the mean calculation, we recorded the results involved in summing the data points within each dataset. The dataset size began at 256 elements and was quadrupled until further computation was no longer feasible. This process was repeated for data ranges from 16 to 8192, increasing in powers of two. The recorded complexity parameters and average execution times are included in Table A1 of Appendix A. In Figure 3, we present a chart based on Table A1 comparing the complexity of mean calculation with respect to the number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

Figure 3.

Comparison of mean calculation complexity with respect to number of data points (represented by n) and their range.

As Figure 3 shows, complexity grows with both size and range. The size of the dataset has a strong influence: larger datasets (e.g., n = 16,384 or n = 65,536) exhibit dramatically higher complexity compared to smaller ones, even at relatively low ranges. Range also affects complexity, but its impact is more moderate and depends on the dataset size. For smaller datasets (n = 256 or n = 1024), increasing the range of data points produces only modest increases in complexity. However, for larger datasets, increases in range amplify complexity substantially, leading to extremely high computational costs for the largest sizes and ranges.

Overall, the figure highlights that both parameters contribute to computational growth, but dataset size is the dominant factor, and range becomes a significant multiplier only for larger datasets. This underscores the challenges of scaling homomorphic computations in Concrete where large sizes and ranges quickly lead to impractical noise levels.

The PBS count is also influenced by both the dataset size and value range. According to Table A1, when the dataset size is quadrupled while keeping the range constant, the PBS count increases by 2. At the same time, doubling the range for a fixed dataset size increases the PBS count by 1, which implies an increase of 2 if the range is quadrupled. This suggests that dataset size and value range have a comparable effect on the PBS count in mean calculations.

Table 3 extracts from Table A1 the maximum sizes achieved for each range. As expected, the maximum dataset size the algorithm can handle decreases as the range increases. The complexity of the PBS counts does not follow a consistent trend except that PBS counts are all 20 or above. However, the PBS count does not seem to be a limiting factor as there are cases in Table A1 where higher PBS counts with higher complexity are executed successfully.

Table 3.

Max size for range with computational statistics and performance under default configuration.

Compile time remains nearly constant across all configurations, suggesting that compilation overhead is insignificant compared to runtime. This pattern reveals that the algorithm’s scalability is not limited by the number of ciphertext computations it performs but by the cost and frequency of noise management within the encrypted domain.

Adjusting p_error Value for Higher Dataset Sizes

For each of the cases in Table 3, running the mean calculation for the next size for a range, for example, size 95,579 for range 16, we received the error “RuntimeError: Unfeasible noise constraint encountered”. To further investigate the limits of Concrete in calculating the mean, we experimented with adjusting the p-error value which defines the probability of error per PBS. We chose to adjust the p-error value instead of the global-p-error value as adjusting the global-p-error value is costly in time as it controls the error globally for all TLUs in the computation. We tested the limits for data range of 16 for a sample with respect to p_error values of . The results are presented in Table 4. The PBS count is the same for most cases but increases slightly for the highest p_error The complexity is also affected by the p_error value. Higher error probability resulted in lower complexity except for p_error , where the complexity increases again. Higher probability errors are also more likely to produce inaccurate results; however, we did not encounter this in calculating the mean. Interestingly, the max size is the same for p_error values of 0.001 and 0.01 even though the complexity was lower in the latter. The size 183,339 seems to be the maximum size of a dataset for which the mean can be homomorphically calculated with Concrete for value range of 16.

Table 4.

Maximum size and complexity for range = 16 with respect to error probability.

6.2. Variance Calculation Results

We ran the variance calculation for sizes of powers of 2 starting with 4 in ranges, and also powers of 2 starting with 4. As Table 5 presents, we were only able to collect limited data since calculation of variance involves encrypted multiplications which is an expensive operation in FHE.

Table 5.

Variance calculation complexity and time.

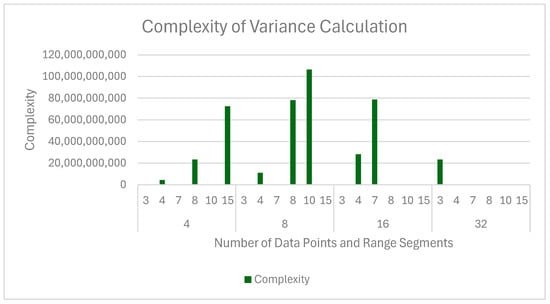

As Table 5 shows, the largest dataset that we could compute the variance for was size 15 and that worked for only range 4. The PBS count and hence the complexity increased quickly with the size as well as the range as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Complexity of variance calculation with respect to number of data points and range.

The data shows a consistent pattern in how increasing both the input size and range affect computational feasibility under homomorphic encryption. The most striking observation is that as the size and range parameters grow, the algorithm quickly approaches operational limits often failing to find valid parameters, indicating that the encryption scheme could not identify parameters that both preserve correctness and maintain acceptable noise levels, or producing GPU memory errors indicating that the ciphertext size, noise growth, or data transfer overhead has exceeded available hardware limits.

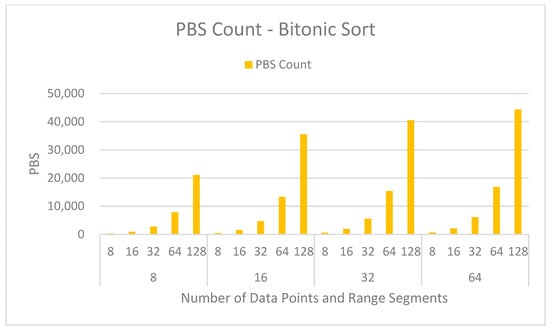

6.3. Bitonic Sort Results

We ran the bitonic sort algorithm with sizes of powers of 2 starting with 8 in ranges, and also powers of 2 starting with 8, initially under the default configuration in Concrete where the global_p_error is set to . Unlike in mean and variance calculations, we encountered inaccurate results in the sorting experiments. Table 6 presents the results with an additional column for accuracy. The accuracy column lists how many of the results were correct out of the number of trials. The values with * indicate cases with inaccurate results.

Table 6.

Bitonic sort complexity, time, and accuracy with global_p_error =

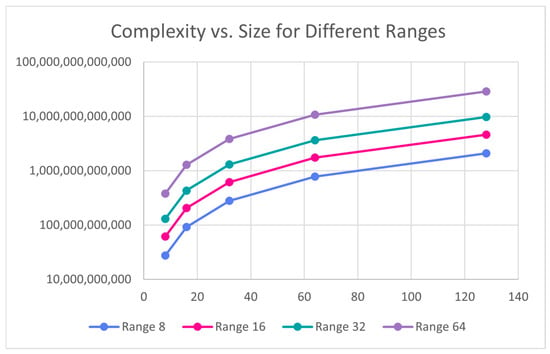

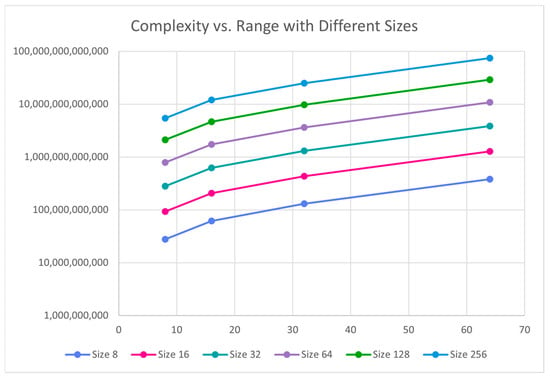

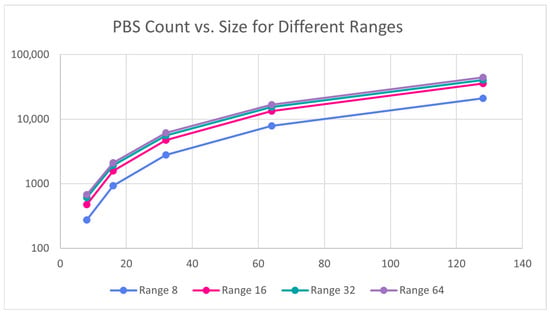

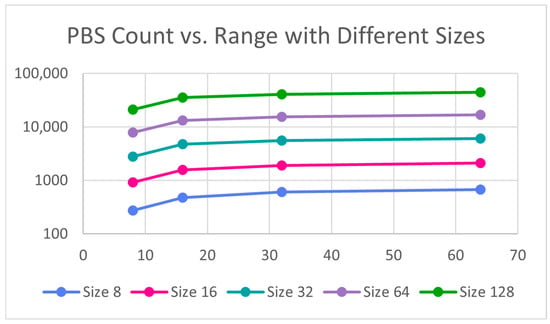

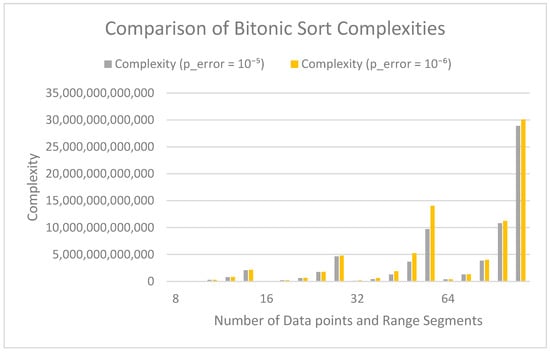

Bitonic sort scales superlinearly with input size and range in general, but homomorphic computations significantly amplify this growth. Figure 5 and Figure 6 depict this growth in PBS counts and complexity, respectively. Each comparison and swap in the encrypted sort involve multiple costly arithmetic and conditional operations, making computations far heavier than in plaintext. For the default configuration, the largest size and range we could run the algorithm for was size 128 and range 64 which took about 397 s. For ranges beyond 64, we received the “No parameters found” error.

Figure 5.

Complexity of bitonic sort with respect to number of data points and range.

Figure 6.

PBS counts in variance calculation with respect to number of data points and range.

The effect of size and range on the complexity and PBS count show similar patterns. Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 plots complexity and PBS count in logarithmic scale with respect to size and range against different ranges and sizes, respectively. Both complexity and PBS count grow rapidly with size and range as expected. Overall, both size and range contribute multiplicatively to complexity, though size tends to have a slightly larger impact. More specifically, when size is doubled, both Complexity and PBS count seem to roughly triple whereas when the range is doubled, they seem to be slightly more than doubled.

Figure 7.

Bitonic sort complexity vs. size.

Figure 8.

Bitonic sort complexity vs. range.

Figure 9.

Bitonic sort PBS count vs. size.

Figure 10.

Bitonic sort PBS count vs. range.

Adjusting p_error for Accuracy

Going back to Table 6, we received inaccurate results for size 64 and range 8; size 64 and range 16, and size 128 and range 16 in default configuration. Due to these inaccuracies, instead of running the experiments for larger sizes in default configuration, we aimed to improve accuracy by adjusting the error probability. We ran the experiments with a p_error value of . We did not reduce the gloabl_p_error because it significantly increases the execution time. This time, we collected data for 10 runs to have a higher chance of catching inaccuracies. Table 7 presents the results for p_error value of .

Table 7.

Bitonic sort complexity, time, and accuracy with p_error =

As Table 6 and Table 7 confirm, the PBS count does not change with error probability; it is the same for a given size and range. Complexity rises slightly for smaller error probabilities as expected, which is highlighted in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Comparison of complexity of bitonic sort with respect to error probability.

The p_error value of appeared to improve accuracy overall as Table 7 shows. However, the case with size 64 and range 16 consistently produced inaccurate results. Interestingly, every run of this instance yielded the same inaccuracies. We repeated the experiment multiple times to verify, but the results did not change. We suspect this issue may stem from an implementation bug in Concrete that arises specifically under the conditions of size 64 and range 16.

To further investigate if sorting can be conducted for larger sizes with higher accuracy, we reduced the p_error by a factor of 10 until we achieved 10/10 accuracy. Table 8 shows the computational statistics and timing data for size 256 and range 16.

Table 8.

Error probability, PBS count, and complexity for size = 256, range = 16.

We were able to achieve 10/10 accuracy for p_error = . We would like to emphasize that this does not imply that all results will be correct under this p_error. The table shows, as expected, PBS count is the same and the complexity increases when we reduce the p_error. It is also worth noting that the rate of increase in complexity is smaller when the p_error is reduced from to .

7. Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to assess the feasibility of using the Concrete framework for performing statistical computations and to explore the practical limits of dataset size and value range that can be processed efficiently. The results show that the mean computation, which primarily involves addition operations, supported relatively larger datasets and broader value ranges. In contrast, the variance computation, dominated by computationally intensive encrypted multiplications, significantly limited the feasible dataset size and range. Sorting operations, which depend on homomorphic comparisons and swaps, also introduced constraints but accommodated somewhat larger datasets than the variance computation.

Overall, the feasibility of sorting and statistical computations on encrypted data with the Concrete implementation of TFHE declines rapidly as dataset size and value range increase, resulting in data limits that are too small for most practical applications. Nevertheless, this work reinforces the theoretical promise of Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) for statistical analysis and highlights a clear path forward: the development of optimized, FHE-compatible algorithms. With continued advancements, the practical application of FHE in real-world analytics is well within reach.

Beyond data size and range restrictions, other limitations such as the inability to divide encrypted numbers and using only integers pose additional challenges that constrain the types of statistical algorithms and applications that can be implemented. These issues become particularly evident when multiple metrics are chained within a computational pipeline. Because Concrete does not support division, in cases where the metric requires division, the system may not be able to carry out the computations. For example, median, being the average of two numbers, will not be accurately computed if the sum of the two numbers is not even. Hence, the application will not produce reliable results.

One potential approach to improve reliability is to reformulate computations so that division is deferred until the final stage, allowing it to be performed by the client. This method was applied in our variance computation, where the calculation of the mean was postponed. However, while this strategy can sometimes be effective, it is not universally applicable and may increase the range of intermediate values and the number of required computations, reducing overall practicality.

Despite these challenges, continued optimization of FHE frameworks, together with algorithmic refinements, is expected to expand the boundaries of what is computationally feasible under encryption. While Concrete is still limited for large-scale or complex statistical computations, continued development may allow it to handle a wider range of analytical tasks more efficiently, bringing the practical application of homomorphic encryption for statistical analysis closer to reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.K.P.; methodology, Y.K.P. and R.R.; software, R.R.; validation, Y.K.P. and R.R.; formal analysis, Y.K.P.; resources, Y.K.P. and R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.K.P. and R.R.; writing—review and editing, Y.K.P. and R.R.; visualization, R.R.; supervision, Y.K.P.; project administration, Y.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| TFHE | Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption over the Torus |

| FHE | Fully Homomorphic Encryption |

| HE | Homomorphic encryption |

| PHE | Partially Homomorphic Encryption |

| SWHE | Somewhat Homomorphic Encryption |

| CKKS | Cheon–Kim–Kim–Song |

| BFV | Brakerski, Fan, and Vercauteren |

| BGV | Brakerski–Gentry–Vaikuntanathan |

| MLIR | Multi-Level Intermediate Representation |

| PBS | Programmable Bootstrapping |

| TLU | Table Lookup |

| SEAL | Simple Encrypted Arithmetic Library |

| WSN | Wireless Sensor Network |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Complexity and time data for mean calculation with global_p_error = 0.00001.

Table A1.

Complexity and time data for mean calculation with global_p_error = 0.00001.

| Size | Range | Complexity | PBS | Compile Time | Average Execution Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 16 | 1,113,961,043 | 13 | 0.281036139 | 0.655717039 |

| 1024 | 16 | 1,336,725,990 | 15 | 0.289981127 | 0.705028772 |

| 4096 | 16 | 2,202,276,832 | 17 | 0.299862385 | 1.175520182 |

| 16,384 | 16 | 4,108,513,032 | 19 | 0.305954695 | 2.640227985 |

| 65,536 | 16 | 20,727,478,758 | 21 | 0.30864954 | 11.15674825 |

| 95,579 | 16 | 23,896,005,966 | 21 | 0.383268356 | 14.32484522 |

| 256 | 32 | 1,201,850,916 | 14 | 0.285609722 | 0.623136091 |

| 1024 | 32 | 1,730,911,600 | 16 | 0.312937975 | 0.81720767 |

| 4096 | 32 | 2,717,788,572 | 18 | 0.307652712 | 1.323466444 |

| 16,384 | 32 | 5,238,209,620 | 20 | 0.30668807 | 2.95935812 |

| 65,535 | 32 | 7,179,406,060 | 20 | 0.304883003 | 7.153872299 |

| 256 | 64 | 1,299,486,135 | 15 | 0.289070845 | 0.637721682 |

| 1024 | 64 | 1,928,622,664 | 17 | 0.301167011 | 0.857152462 |

| 4096 | 64 | 3,279,103,828 | 19 | 0.308574915 | 1.476102543 |

| 16,384 | 64 | 7,603,694,658 | 21 | 0.309091568 | 3.622408867 |

| 32,767 | 64 | 10,589,632,914 | 21 | 0.316554308 | 5.746519852 |

| 256 | 128 | 1,433,189,232 | 16 | 0.293736696 | 0.68343792 |

| 1024 | 128 | 2,331,822,528 | 18 | 0.300023317 | 0.964575052 |

| 4096 | 128 | 4,332,584,140 | 20 | 0.309374571 | 1.783250475 |

| 16,384 | 128 | 21,907,679,046 | 22 | 0.314444542 | 7.764439631 |

| 22,808 | 128 | 24,993,405,690 | 22 | 0.321526527 | 9.079599237 |

| 256 | 256 | 1,840,364,546 | 17 | 0.314444542 | 0.785029554 |

| 1024 | 256 | 2,868,776,826 | 19 | 0.310507059 | 1.116463137 |

| 4096 | 256 | 5,519,796,219 | 21 | 0.312054157 | 2.113553667 |

| 16,383 | 256 | 21,907,679,046 | 22 | 0.323411226 | 7.729421425 |

| 256 | 512 | 2,056,447,944 | 18 | 0.314338207 | 0.835879993 |

| 1024 | 512 | 3,457,985,820 | 20 | 0.322290897 | 1.282216167 |

| 4096 | 512 | 8,075,261,260 | 22 | 0.322939396 | 2.841636515 |

| 8191 | 512 | 11,149,094,968 | 22 | 0.319616556 | 3.997267628 |

| 256 | 1024 | 2,465,891,725 | 19 | 0.320339203 | 0.944214153 |

| 1024 | 1024 | 4,557,438,606 | 21 | 0.323120832 | 1.595302629 |

| 4096 | 1024 | 23,032,783,326 | 23 | 0.327869892 | 7.104405308 |

| 5454 | 1024 | 26,129,469,585 | 23 | 0.327910423 | 8.045698881 |

| 256 | 2048 | 3,025,294,660 | 20 | 0.325703144 | 1.109195566 |

| 1024 | 2048 | 5,803,256,734 | 22 | 0.324588537 | 1.996102905 |

| 4095 | 2048 | 23,032,783,326 | 23 | 0.329586029 | 7.109924364 |

| 256 | 4096 | 3,637,497,570 | 21 | 0.32682848 | 1.214597225 |

| 1024 | 4096 | 8,647,044,465 | 23 | 0.329022884 | 2.81143322 |

| 2047 | 4096 | 11,718,755,783 | 23 | 0.320230484 | 3.8087327 |

| 256 | 8192 | 4,783,076,430 | 22 | 0.327912569 | 1.671923494 |

| 1024 | 8192 | 24,163,416,936 | 24 | 0.334160089 | 7.362909079 |

| 1306 | 8192 | 27,132,970,608 | 24 | 0.327442884 | 8.142111588 |

References

- Statistical Confidentiality and Personal Data Protection—Microdata—Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/statistical-confidentiality-and-personal-data-protection# (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- 2.11 Confidential Information Protection and Statistical Efficiency Act (2002) | CIO.GOV. Available online: https://www.cio.gov/handbook/it-laws/cipsea/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- United States Census Bureau Statistical Safeguards. Available online: https://www.census.gov/about/policies/privacy/statistical_safeguards.html (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Innovations in Federal Statistics: Combining Data Sources While Protecting Privacy. Available online: https://mitsloan.mit.edu/shared/ods/documents?DocumentID=4438 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Data Protection and Privacy Policy. Available online: https://www.census.gov/about/policies/privacy.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Statistical Confidentiality | Insee. Available online: https://www.insee.fr/en/information/2388575 (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Statistical Standards Program—Confidentiality Procedures. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/statprog/confproc.asp (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Differential Privacy for Census Data Explained. Available online: https://www.ncsl.org/technology-and-communication/differential-privacy-for-census-data-explained (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Decennial Census Disclosure Avoidance. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/disclosure-avoidance.html (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Welcome | Concrete. Available online: https://docs.zama.ai/concrete (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. TFHE: Fast Fully Homomorphic Encryption Over the Torus. J. Cryptol. 2019, 33, 34–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentry, C. Fully Homomorphic Encryption Using Ideal Lattices. In Proceedings of the STOC ’09: Symposium on Theory of Computing, Bethesda, MD, USA, 31 May–2 June 2009; pp. 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, J.H.; Kim, A.; Kim, M.; Song, Y. Homomorphic Encryption for Arithmetic of Approximate Numbers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Hong Kong, China, 3–7 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brakerski, Z.; Gentry, C.; Vaikuntanathan, V. (Leveled) Fully Homomorphic Encryption without Bootstrapping. In Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference (ITCS 2012), Cambridge, MA, USA, 8–10 January 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chillotti, I.; Gama, N.; Georgieva, M.; Izabachène, M. Faster Fully Homomorphic Encryption: Bootstrapping in Less than 0.1 Seconds. In Proceedings of the International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security, Hanoi, Vietnam, 4–8 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- A Fully Homomorphic Encryption Application: SHA256 on Encrypted Input. Available online: https://webthesis.biblio.polito.it/29342/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Zama—Open Source Cryptography. Available online: https://www.zama.org/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- MLIR. Available online: https://mlir.llvm.org/ (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Bergerat, L.; Boudi, A.; Bourgerie, Q.; Chillotti, I.; Ligier, D.; Orfila, J.-B.; Tap, S. Parameter Optimization and Larger Precision for (T)FHE. J. Cryptol. 2023, 36, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementation Strategies | Concrete. Available online: https://docs.zama.ai/concrete/guides/self/self-1/strategies (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Microsoft SEAL: Fast and Easy-to-Use Homomorphic Encryption Library. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/research/project/microsoft-seal/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- IBM Z Content Solutions | Fully Homomorphic Encryption. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/support/z-content-solutions/fully-homomorphic-encryption/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Feng, X.M.; Li, X.D.; Zhou, S.Y.; Jin, X. Homomorphic Comparison Method Based on Dynamically Polynomial Com-posite Approximating Sign Function. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Orlando, FL, USA, 2–5 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.; Kim, S.; Choi, J.; Lee, Y.; Cheon, J.H. Efficient Sorting of Homomorphic Encrypted Data with K-Way Sort-ing Network. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2021, 16, 4389–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvi, N.B.; Shylashree, N. Innovative Homomorphic Sorting of Environmental Data in Area Monitoring Wireless Sensor Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 59260–59272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, H. An Efficient Fully Homomorphic Encryption Sorting Algorithm Using Addition Over TFHE. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 28th International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Systems (ICPADS), Nanjing, China, 10–12 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Chang, X.; Mišić, J.; Mišić, V.B.; Wang, J.; Zhu, H. Practical Solutions in Fully Homomorphic Encryption: A Survey Analyzing Existing Acceleration Methods. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.J.; Huang, Z.; Hong, C.; Ma, Y.; Qu, H. PEGASUS: Bridging Polynomial and Non-Polynomial Evaluations in Homomorphic Encryption. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–27 May 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Seo, J.; Nam, Y.; Chae, J.; Cheon, J.H. HEaaN-STAT: A Privacy-Preserving Statistical Analysis Toolkit for Large-Scale Numerical, Ordinal, and Categorical Data. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 1224–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzone, F.; Everts, M.; Hahn, F.; Peter, A. Efficient Ranking, Order Statistics, and Sorting under CKKS. In Proceedings of the 34th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–15 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Raj, R.; Kurt Peker, Y.; Mutlu, Z.D. Blockchain and Homomorphic Encryption for Data Security and Statistical Privacy. Electronics 2024, 13, 3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.