Abstract

Drought remains one of the most damaging natural hazards to agricultural production and is projected to continue posing substantial risks to food security in the future, particularly in major rice-growing regions. Based on the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios under CMIP5, this study used a process-based crop growth model to simulate the growth of rice in China in different future periods (short-term (2031–2050), medium-term (2051–2070), and long-term (2071–2090)). We fitted rice vulnerability curves to evaluate the rice drought risk quantitatively according to the simulated water stress (WS) and yield. The results showed that the drought hazard in major rice-growing areas in China (MRAC) were low in the middle and high in the north and south. The areas without rice yield loss will decline in the future, while the areas with a high yield loss will increase, especially in southwestern China and the middle and lower Yangtze Plain (MLYP). Owing to the markedly increased evaporative demand and the reduced moisture transport caused by a weakening East Asian summer monsoon, northeastern China will be a high-risk area in the future, with the expected yield loss rates in scenarios RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 being 39.75% and 45.5%, respectively. In addition, under the RCP8.5 scenario, the yield loss rate of different return periods in south China will exceed 80%. A significant gap between rice supply and demand affected by drought is expected in the short-term future. The gaps will be 67,770 kt and 78,110 kt under the RCP4.5-SSP2 and RCP8.5-SSP3 scenarios, respectively. The methodology developed in this paper can support the quantitative assessment of drought loss risk in different scenarios using crop growth models. In the context of the future expansion of Chinese grain demand, this study can serve as a reference to improve the capacity for regional drought risk prevention and ensure regional food security.

1. Introduction

In the context of global warming, the intensity and frequency of extreme disaster events, such as heatwaves, rainstorms, and agro-ecological droughts, will increase in the future [1]. Climate change has become a major driver of increasing agricultural drought [2]. Over the past 60 years, a total of 47 drought events have occurred across China, with an average duration of 7.14 months. Furthermore, during the period 1980–2010, the average affected area of drought events per decade exhibited a continuously expanding trend [3]. The vulnerability of food production has been exposed by drought and may spill over into social vulnerability, stability, and conflict relationships, making it necessary to advance the understanding and management of drought risks [2]. Rice has the highest water requirement among cereals, with almost 3000–5000 L of fresh water needed to produce 1 kg of rice. Drought will have a huge impact on rice yield [4].

As one of the largest rice producers and consumers worldwide, Chinese rice farming plays a vital role in regional and global food security. The MRACs (major rice-growing areas in China) are distributed across the alluvial plain of eastern China, including the plain of northeast, MLYP (the middle and lower Yangtze Plain), and south China. Recently, the pattern of rice growing in China has shifted to the northeast [5]. The severity and frequency of drought risk in China have increased due to climate change [6], and the regions and characteristics of drought have changed significantly. The impact of drought on agriculture is mainly concentrated in northwest and north China. The center of gravity shifted to northeast and southwest [7], which coincided with the distribution and change in the spatial pattern of rice. Therefore, strengthening drought risk assessment is of great significance for improving the stability of rice production and ensuring food security.

The method of drought risk assessment can be divided into three categories, including grading-based risk, indicator-based risk, and probability loss risk. The indicator-based drought risk assessment involves establishing an assessment index system. Nam et al. analyzed indicators of drought frequency, duration, severity, and amplitude, and conducted a quantitative assessment of drought hazard in South Korea [8]. Arab et al. used comprehensive drought indices derived from vegetation, soil moisture, and precipitation to assess the severity of drought and determine the changes in grape yield in vineyards affected by drought [9]. He et al. developed a comprehensive drought risk assessment model including the standardized precipitation index, irrigation availability, and water shortage of seasonal crops to assess the drought risk of wheat, maize, and rice. Meanwhile graded drought risk assessment mainly classifies risk components through GIS spatial analysis and other means [10]. Zhao et al., using multiple nonlinear regression technology, created a new drought risk assessment model to evaluate and grade drought risk in China, and obtained the drought risk in China [11].

The above two methods can fully consider the characteristics of risk components and are easy to calculate, so they are well promoted. However, they are mostly expressed in the form of a dimensionless index or grade, which makes it difficult to express the probability or expected loss of crop yield. In order to accurately analyze the probability of crop yield loss caused by drought under the influence of future climate change, probabilistic loss-based risk assessment is needed. However, this kind of risk assessment needs to establish the relationship curve of different disaster intensity and yield loss, namely a vulnerability curve. The vulnerability curve has been widely used in vulnerability studies of floods, earthquakes, typhoons, landslides, and other disasters. As a quantitative vulnerability assessment method, it has also been widely used in agricultural drought studies. Some scholars have studied crop yield reduction under different drought scenarios from the perspective of meteorological yield [12,13].

This study innovatively developed a quantitative drought risk assessment framework for rice based on a crop model, enabling the high-resolution (0.00833° × 0.00833°) probabilistic loss estimation of yield. We also produced China’s first 0.5° × 0.5° gridded set of rice drought vulnerability curves, supporting the rapid assessment of drought-induced yield loss and improved probabilistic risk evaluation. Therefore, based on the EPIC model (Environmental Policy Integrated Climate model), this study simulated rice yield loss rates under different drought intensities, constructed drought vulnerability curves of MRACs, and carried out a quantitative assessment of rice yield loss risk under future climate change. This was all conducted in order to provide a reference for ensuring food security, improving regional disaster prevention and mitigation capacity, and strengthening adaptation strategies to climate change.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

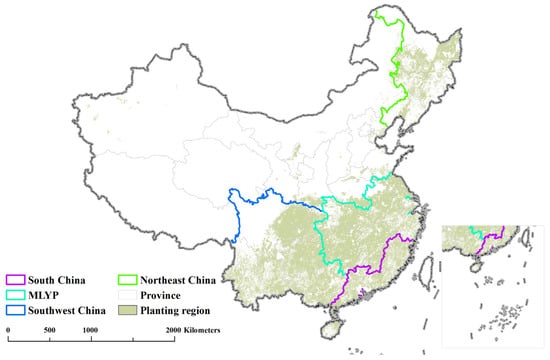

The MRACs exhibit distinct zonal distribution characteristics, primarily encompassing the Northeast China Rice Region, the Middle and Lower Yangtze River Plains (MLYRs), the South China Rice Region, and the Southwest China Rice Region (Figure 1). These areas show significant differences in thermal resources, precipitation conditions, arable land patterns, and cropping systems, collectively forming the dominant framework of rice production in China.

Figure 1.

The major rice-growing areas in China.

The Northeast China Rice Region is mainly distributed across Heilongjiang, Jilin, and northern Liaoning, with core areas including the Sanjiang Plain and the northern Songnen Plain. Influenced by a cold–temperate monsoon climate, this region has a ≥10 °C accumulated temperature of approximately 2600–3200 °C·d and annual precipitation of 450–650 mm, with relatively high water–heat synergy. It is characterized by single-season Japonica rice cultivation, high mechanization levels, and serves as the core area for high-latitude, high-yield rice production in China.

The MLYRs include areas such as Jiangsu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan. Characterized by a subtropical humid monsoon climate, it has a ≥10 °C accumulated temperature of 4500–5500 °C·d and annual precipitation of 1200–1600 mm, making it the most representative region for double-cropping rice in China. The area boasts an extensive water network and excellent irrigation conditions, though cropland is trending towards fragmentation due to urban expansion.

The South China Rice Region, distributed across Guangdong, Guangxi, southern Fujian, and Hainan, features a tropical to southern subtropical monsoon climate with precipitation of 1500–2000 mm and a ≥10 °C accumulated temperature exceeding 6000 °C·d. The thermal resources are extremely abundant, allowing for triple-cropping systems in some parts. This region suffers from high land fragmentation, and there is evident spatial conflict between rice cultivation and competitive cash crops (e.g., sugarcane, fruits, and vegetables).

The Southwest China Rice Region includes the Sichuan Basin, eastern Chongqing, some river valleys in Yunnan, and low-altitude areas of Guizhou. The terrain is complex, with precipitation ranging 900–1500 mm and large variations in ≥10 °C accumulated temperature (3500–5500 °C·d). Single-season rice predominates, with double-cropping possible in parts of the Sichuan Basin. Cultivated land mainly consists of river alluvial plains and mountainous terraced fields, characterized by fragmented land use and limited mechanization.

Overall, rice production in the MRACs is influenced jointly by climatic resources, topographic conditions, and land use patterns: the northeast region has high yields but is constrained by heat availability; the MLYR is the stable core area for double-cropping rice; south China has ample heat but suffers from land fragmentation; and southwest China features a distinctive mountain rice farming system. The climate sensitivity of these different regions has significant implications for future rice production potential and serves as an essential basis for conducting climate change impact assessments.

2.2. Data

In this study, multiple environmental and management datasets were integrated to drive the EPIC model and to conduct drought risk assessment across major rice-growing regions in China. The data sources and their spatial–temporal characteristics are summarized in Table 1, and detailed descriptions are provided as follows.

Table 1.

The parameters used in this paper.

Altitude data were obtained from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) at a spatial resolution of 0.0833° × 0.0833° (1996 release) [14]. Slope data were derived from the Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ) dataset developed by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), with a spatial resolution of 0.0833° × 0.0833° (GAEZ v3.0, released in 2002) [15]. Soil data were sourced from the International Soil Reference and Information Centre (ISRIC), using the 5′ × 5′ SoilGrids dataset (2012), which provides global information on soil physical and chemical properties such as texture, pH, bulk density, gravel content, and field capacity [16].

Meteorological data were obtained from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Intercomparison Project (ISIMIP) at a spatial resolution of 0.5° × 0.5° for the period 1975–2090 [17]. The ISIMIP forcing dataset is derived from global climate model outputs and bias-adjusted using the EWEMBI observational dataset, which integrates multiple observation and reanalysis products including CRU, GPCC, and ERA-Interim. The meteorological variables used as EPIC model inputs include temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation. This study defines 1975–2020 as the baseline period and uses three future time slices—2031–2050 (short term), 2051–2070 (medium term), and 2071–2090 (long term)—for scenario analysis. Simulations were conducted under two representative concentration pathways, RCP4.5 (medium–low emissions) and RCP8.5 (high emissions) under CMIP5, which incorporate both climatic and socio-economic assumptions.

Planting area data were derived from datasets provided by Sun Yat-sen University, with a spatial resolution of 0.00833° × 0.00833° (2017–2022) [18]. Rice growth period data were obtained from the Center for Sustainability and the Global Environment (SAGE) at the University of Wisconsin–Madison (2010), providing spatially explicit information on rice phenology [19]. Irrigation data were taken from the University of Tokyo (OKI Laboratory) global irrigation dataset (2002) at 0.5° × 0.5° resolution [20]. Fertilizer application data were obtained from the Land Use and the Global Environment (LUGE) dataset (2010), which provides agricultural nutrient input information at 0.5° × 0.5° resolution [21].

For the purpose of fitting the vulnerability curves for each grid, all datasets were resampled to the coarsest spatial resolution (0.5°), and their temporal resolution was aggregated to daily values prior to model simulation.

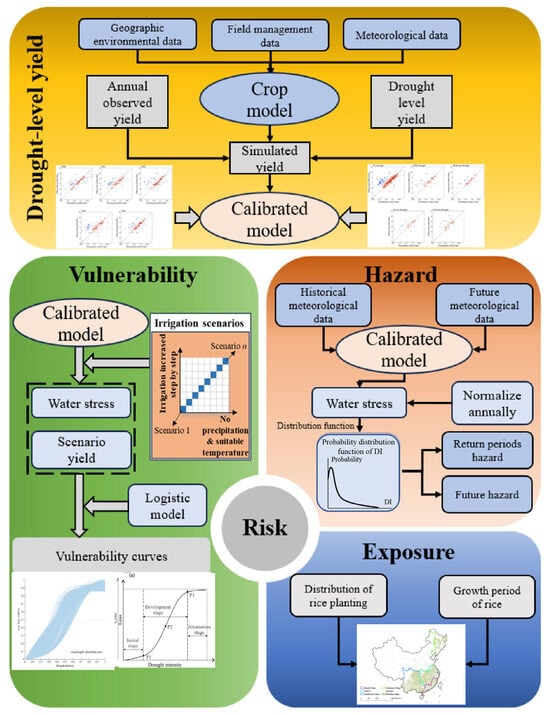

2.3. Overview of Evaluation System

In this paper, rice drought risk was defined as the predictable yield loss rate caused by a certain drought intensity during the growth period [22]. The disaster-causing factor of rice is the drought intensity suffered by rice during its growth period. Vulnerability is the effect of rice yield hit by disaster-causing factors. The exposure is the area of MRAC. Therefore, based on the regional disaster system theory, we defined rice drought risk as a function of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure (Equation (1)) [23].

where R, H, V and E represent drought risk, hazard, vulnerability, and exposure, respectively. Vulnerability, which can be divided into social and natural aspects, is an indicator to measure the relationship between disaster hazard and loss of exposure. The natural attributes of vulnerability emphasize the inherent characteristics of the hazard-affected body [24], and the physical vulnerability is related to the unique physical properties of the hazard-affected body [25]. When the system is exposed to disaster, the potential loss of exposure is greatly affected by it. The social aspect of vulnerability is influenced by human behavior and decision making and is mainly manifested in reducing the impact of meteorological disturbance on agricultural production in crop cultivation. This study assumes that the social aspects of vulnerability are the same and constant, focusing on natural drought vulnerability under the coupling effect of crop physical characteristics and climate change. The risk assessment under the impact of natural drought vulnerability can provide important information for people creating disaster prevention measures and help reduce losses in medium–high-risk areas. In this paper, the curve between drought intensity and drought loss variables was fitted to reveal the response of rice yield to different drought intensities. Therefore, vulnerability in this paper is expressed as a function of drought intensity and loss rate (Equation (2)).

where V is physical vulnerability, f is the functional relationship between DI and LR, DI represents the degree of drought, and LR represents the yield loss rate of rice under a certain degree of drought. In our study, DI represents the hazard (H), while the rice cultivation area represents the exposure (E).

This study was carried out in four parts (Figure 2). Before starting, we first calibrated the EPIC crop model using the annual yield of rice at the city level in 2000. We evaluated the simulation performance year by year and under drought conditions to achieve the required simulation accuracy. Then, calibrated EPIC was used to simulate the growth process of rice in the base period to obtain water stress. The probability density distributions of drought hazard at different return periods were calculated after normalization. After that, we obtained sample groups of drought intensity and corresponding yield by controlling irrigation volume under the condition that artificial irrigation was the only water source and there was no other stress, and fitted the vulnerability curve of each evaluation unit. Finally, we calculated the probability of rice loss under different drought intensities by combining the probability density distribution of drought hazard in different return periods, the vulnerability curve of rice, and the exposure of rice.

Figure 2.

Risk assessment framework. The probability distribution function of drought intensity of each evaluation unit was coupled with the physical vulnerability curve of rice to obtain the final probability distribution function of rice drought loss rate.

2.4. EPIC Model and Calibration

EPIC is a comprehensive model that simulates the growth process of crops under certain environmental conditions, including temperature, soil, hydrology, fertilization, and other factors. It can simulate the yield of crops per unit area for one year and output the WS (water stress) of rice during its growth period in a daily step. It is widely used in crop drought research worldwide [26,27,28]. The applications of the EPIC model can be divided into three main categories: improving the accuracy of crop growth models, applying research on the impact of climate change, and mitigating the risk of agricultural drought [29].

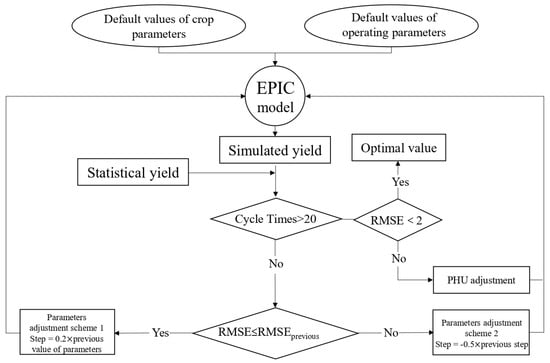

EPIC is a comprehensive model to simulate the growth process of crops under certain environmental conditions, including temperature, soil, hydrology, fertilization, and other modules, which can simulate the yield of crops per unit area for a year and output the water stress of rice during its growth period in a daily step. In this study, EPIC0509 was used to simulate the growth process of rice in MRACs. In view of previous studies [25,30,31], four key crop parameters including biomass energy ratio (WA), harvest index (HI), maximum potential leaf area index (DLMA), and leaf area decline rate (DLAI) in the growing season, as well as potential thermal unit (PHU), the key parameter of output operation files, were used to correct the EPIC model. The optimal parameters of the EPIC model were determined according to the flow chart in Figure 3. The four crop parameters were adjusted preferentially. If the RMSE result was greater than 2, PHU was further adjusted and the four crop parameters were further adjusted until the RMSE was less than 2 or reduced to the minimum.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of model calibration.

We used the rice yield of MRACs in 2000 as the calibration reference data, and the rice yield of prefecture-level cities in MRACs was mainly derived from the statistical yearbook data of provinces and cities. We adjusted the model parameters by combining climate, soil, and output operation data in order to ensure that the average rice yield simulated by the model is closest to the actual observed statistical yield. Then the simulated output from 2001 to 2004 was compared with the actual observed output to verify the performance and accuracy of the model simulation.

2.5. Fitting of Vulnerability Curves

The vulnerability curve in this paper is a function of drought intensity (WS) and yield loss rate (LR). The yield loss rate is relative to the maximum yield (that is, the yield at which water and nutrient requirements are fully met). Under the optimal irrigation condition, the yield of rice was the highest, and the yield loss rate was 0. It can be calculated using Equation (3).

where LRi is yield loss rate under irrigation scenario i; y is the output under this scenario; and max (i) is the rice yield under optimal irrigation condition.

In order to exclude the influence of meteorological precipitation, surface runoff, and other uncertain disturbance factors, based on previous studies [22], we set up virtual climate conditions. Under these conditions, artificial irrigation was the only water source during the growth period of rice, which eliminated the influence of precipitation and other climate stresses. Therefore, the drought intensity of rice can be controlled by artificial irrigation. First, we observed yield changes by gradually increasing irrigation to determine the maximum suitable irrigation amount for crops (that is, after a certain amount of irrigation is exceeded, the yield will not change significantly if the amount of irrigation continues to be increased). Second, EPIC management file (*.OPS)-related parameters were modified to control the irrigation amount. Irrigation is carried out every five days from the beginning of the rice-growing season. The irrigation amount of each evaluation unit is divided into 20 grades from 0 to maximum, and a different irrigation amount corresponds to different drought intensity.

Finally, we simulate the combination of drought intensity and loss rate. Referring to previous studies [25], we used logistic equation fitting to obtain the vulnerability curve function of each evaluated grid. (Equation (4)) is as follows:

where a, b and c are fitting parameters, LR is the crop yield loss rate, and DI is the drought intensity index of hazard.

2.6. Risk Assessment of Rice Drought

The annual cumulative value of water stress was selected as the index of drought disaster. Water stress (WS) is an important indicator of water supply and demand during crop growth and is also the daily output data of the EPIC model. Its variation range is 0–1, and the larger the value is, the more serious the crop water shortage is. In this study, we used the normalized value of accumulated water stress in the rice-growing season to represent drought intensity to cover two factors: disaster intensity and disaster duration. It can be calculated using Equations (5) and (6).

where DI is the drought intensity index under a certain scenario; WSi is the water stress value at day i (when water stress was the maximum of all stresses); n is the number of days affected by water stress in the growing season; WStotal is the accumulated value of water stress in the growing season under a certain scenario; ui,l represent the water use amount in the layer; l denotes the soil layer index; m represents the total number of soil layers.; and Epi denotes the potential plant water use on day i. Max (WStotal) is the maximum value of cumulative stress in the case of no precipitation and no irrigation.

Based on information diffusion theory [32], we calculated the probability density distributions of different drought intensity return periods by using DI samples from historical periods (1975–2020).

3. Results

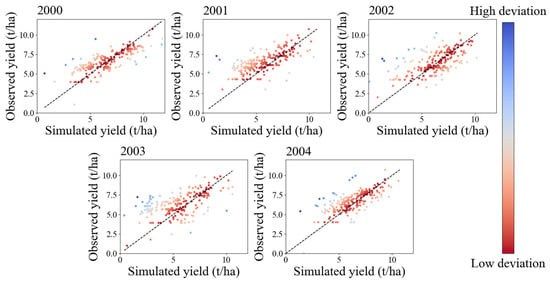

3.1. Model Simulation Performance

The average yield from 2001 to 2004 simulated by the model is close to the actual observed data (Table 2, Figure 4 and Figure 5). The Pearson correlation coefficient between the simulated and observed values is 0.662 (p < 0.01), indicating that there is a great correlation between simulated yield and actual yield. The overall RMSE is 1.496, indicating a small deviation between the simulated value and the actual observed value. T-test results of paired samples show that the difference between observed yield and simulated yield was statistically significant. The PBIAS values are all less than ±9%, which is within the recommended standard range [33]. Therefore, the performance of the corrected EPIC model is sufficient to simulate future rice yields.

Table 2.

Comparison of simulated and observed yields. * indicates significance at the 0.05 level; ** indicates significance at the 0.01 level.

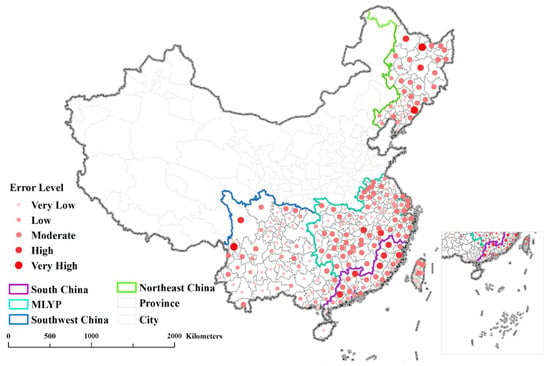

Figure 4.

Scatter plot of simulated and observed yields. The scatter plot shows the relationship between EPIC’s simulated and actual yields. The dashed line in the figure represents the 1:1 line. The points converge around the 1:1 line.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of the mean absolute error (MAE) between simulated and observed yields. The map illustrates the MAE of EPIC-simulated yields compared with actual observations across all cities.

Overall, most regions exhibit relatively low MAE values, indicating a robust and spatially consistent model performance. Meteorological drought can indicate crop drought to some extent. Therefore, to test the simulation performance of the EPIC model for different drought levels, we first calculated SPI using long-term precipitation records (1975–present), and then extracted the SPI values for 2000–2004 at each site for model validation, classified the meteorological drought levels of each municipality based on the SPI (Table 3), and verified the performance of the EPIC model under different meteorological drought levels.

Table 3.

Interpretation thresholds of SPI.

Meteorological drought can indicate crop drought to some extent. Therefore, to test the simulation performance of the EPIC model for different drought levels, we first calculated SPI using long-term precipitation records (1975–present), and then extracted the SPI values for 2000–2004 at each site for model validation, classify the meteorological drought levels of each municipality based on the SPI (Table 3), and verify the performance of the EPIC model under different meteorological drought levels.

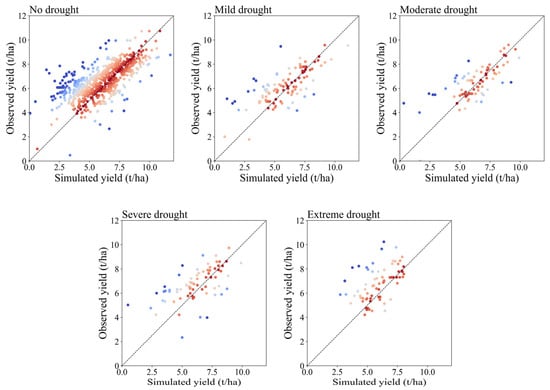

The RMSE is less than 1.7 for all five meteorological drought levels, indicating a small deviation between the simulated and observed values, and the PBIAS values are less than ±15%, which is within the recommended standard (Table 4, Figure 6). Among them, the EPIC model performs well in simulating no drought, mild drought, and moderate drought, with correlation coefficients all exceeding 0.65. Therefore, we believe that the modified EPIC model has a better simulation performance than the original version under different drought levels.

Table 4.

Comparison of simulated and observed yields under different meteorological drought levels. ** indicates significance at the 0.01 level.

Figure 6.

Scatter plots showing the relationship between simulated and actual yields under different drought levels. The dashed line in the figure represents the 1:1 line. The points converge around the 1:1 line.

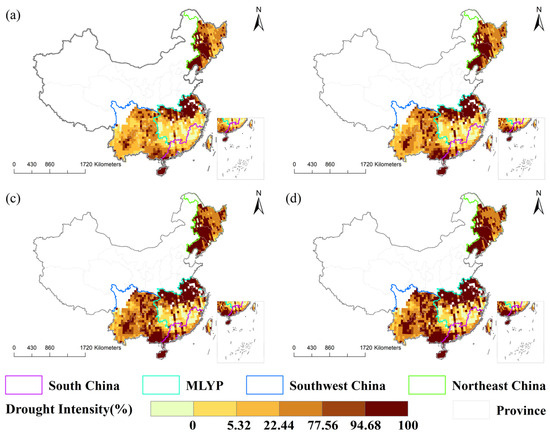

3.2. Drought Hazard

In this study, the drought degree was used as the disaster hazard to evaluate the risk of rice drought in China during the historical period 1975–2020, and the probability distribution of drought hazard under different situations in China was obtained (Figure 7). As can be seen from the figure, drought events occurred in the southwest of northeast China, north of MLYP, and south of south China. However, the frequency of drought events is relatively low in east and south China. The distribution characteristics of drought hazard are low in the middle and high in the north and south. On the whole, the change in drought risk probability distribution in four different return periods was not significant. The occurrence probability of drought events that occurred once in 10 years, once in 20 years, once in 50 years, and once in 100 years in MRACs increased successively, especially in the surrounding areas of central China and south China. It is worth noting that on the 100-year drought risk probability distribution map, the area with a high drought hazard is significantly larger than the other three types of drought risk probability distribution. In Liaoning province, Jilin Province, Jiangsu Province, Anhui Province, and Hainan province, the drought hazard was the highest, and the probability of drought events in different return periods was more than 90%. Rice was vulnerable to drought disaster in its growth period.

Figure 7.

Hazard distribution under different return periods of baseline (1975–2020). (a) 10-year return periods, (b) 20-year return periods, (c) 50-year return periods, (d) 100-year return periods. The darker the color, the greater the drought intensity at that probability level.

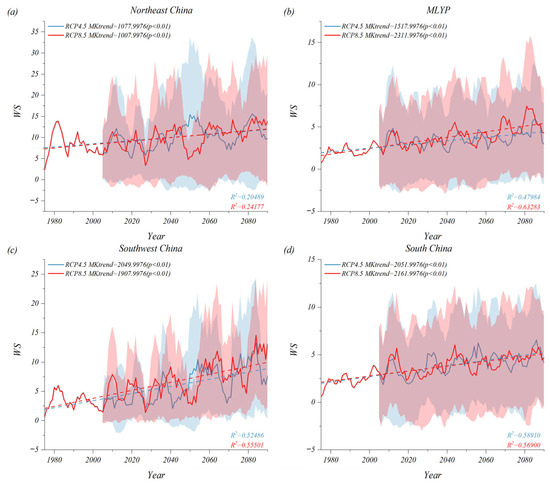

The annual cumulative water stress index of northeast China, MLYP, southwest China, and south China was counted and plotted as a time variation curve of disaster risk (Figure 8) to compare the future changes in disaster hazard in different regions. The MK trend test showed that the four regions showed an increasing trend under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios (p < 0.001), indicating that MRACs would be hit by a stronger disaster hazard in the future. It is found that WS trends and fluctuation states in MLYP and south China are very similar in both historical and future periods. In addition, under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios, WS has a high consistency and the growth trend is relatively slow. The average water stress index in the future is about 4 (±2), indicating that there is no significant difference between the drought intensity in the future and that in the present. It should be noted that the historical and future WS changes in northeast China and southwest China are highly volatile, indicating that the occurrence of future droughts will be highly uncertain. The average water stress index in northeast China is about 10 (±5). In addition, in the future time series, WS changes in northeast China and southwest China show significant differences under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios, which may be caused by the precipitation pattern changes caused by the significant increase in temperature under the RCP8.5 scenario.

Figure 8.

Time variations in disaster-causing factors in four regions of China from 1975 to 2090 under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. (a) Northeast China, (b) MLYP, (c) southwest China, (d) south China. The shadow is the standard deviation range of water stress. The doashed lines represent the projected trend lines for the future period under different climate scenarios (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5).

3.3. Drought Vulnerability Curves

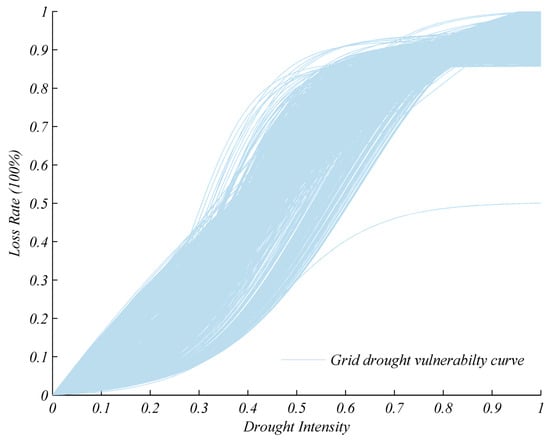

By fitting the rice vulnerability curve of each basic assessment unit (0.5° grid), the relationship between rice yield loss and drought intensity in China was obtained, as shown in Figure 9. A vulnerability curve near the Y-axis is more sensitive to drought. A curve closer to the X-axis means lower drought vulnerability. In most areas, the yield loss rate increased rapidly when the drought intensity value reached 0.3–0.75. When the drought intensity was between 0.4 and 0.45, the vulnerability curve changed the most. When the drought intensity reached 0.75, the increase in yield loss rate decreased.

Figure 9.

Drought vulnerability curve of rice at grid level. Each curve represents a vulnerability curve related to the grid, which represents the yield loss rate of rice in that unit under a certain drought intensity.

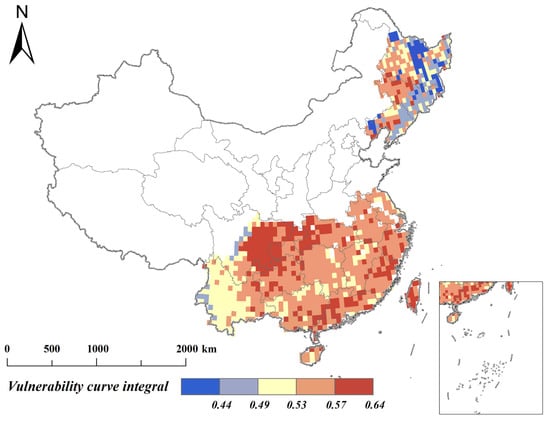

As shown in the integral diagram of the vulnerability curve (Figure 10), the vulnerability of rice has obvious spatial heterogeneity. Overall, the integral value of the vulnerability curve is low in northeast China (the total integral is less than 0.53), and the integral value of the vulnerability curve south of the Qinling-Huaihe River is high (the total integral value is greater than 0.53). Among them, the definite integral values of vulnerability curves in Sichuan Basin, western and northwestern Hubei, central and southern Guangxi, central Zhejiang-Fujian, and most of Guangdong and Taiwan are higher, ranging from 0.57 to 0.64, which indicates that rice in these areas is more sensitive to drought. The definite integral values of central and southern Heilongjiang and western Liaoning are lower than 0.44, indicating that they are less affected by drought and have stronger disaster resistance.

Figure 10.

Distribution of definite integral values of vulnerability curve. The figure shows the spatial distribution of integral values of all vulnerability curves. The values are mostly distributed between 0.53 and 0.57, accounting for about 55% of the total area.

3.4. Drought Risk Assessment

3.4.1. Yield Loss Rate in Different Return Periods

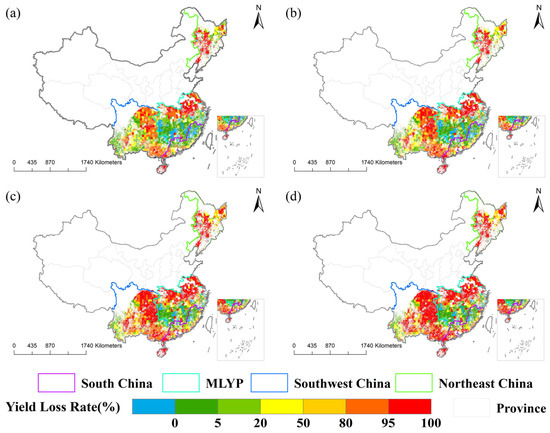

As shown in Figure 11, the rate of rice yield loss in China is generally high in the north and low in the south in the past period. The rate is high in the central part of northeast China and the Yangtze River Basin, the rate is second highest in the south of Nanling, the rate is lower in the southwest border area of northeast China and the central area of south China, and the rate is lower in the central area of south China.

Figure 11.

Yield loss rate of rice under different return periods of baseline (1975–2020). (a) Yield loss rate once in 10 years, (b) yield loss rate once in 20 years, (c) yield loss rate once in 50 years, (d) yield loss rate once in 100 years. Regions in red indicate high yield loss rate (high risk), regions in green indicate low yield loss rate (low risk).

As can be seen from the figure, with the increase in drought-induced disaster intensity, areas without rice yield loss decreased, while areas with high yield loss increased, especially in southwest China and the Yangtze River Basin. The rice drought loss rates that occurred once in 50 years and once in 100 years were significantly higher than those that occurred once in 10 years and once in 20 years.

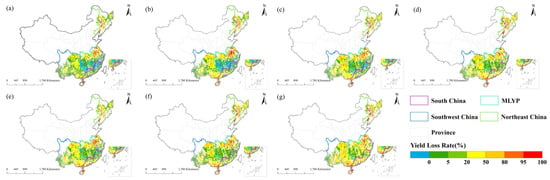

3.4.2. Yield Loss Rate in the Future Periods

This paper discusses the risk of rice drought in China in the future to improve rice yield, ensure food security, and provide theoretical guidance for regional disaster prevention and reduction. We evaluated rice drought risk in the short term (2031–2050), medium term (2051–2070) and long term (2071–2090), and simulated meteorological scenarios RCP4.5 and RCP8.5. By comparing the rice drought risk in three periods, the trend of rice drought risk in China in the future was analyzed.

As shown in Figure 12, central northeast China, the Yangtze River Basin, and the south of Nanling region have three higher expected loss rates, while the other regions have lower expected yield loss rates, and the Jianghuai region is scattered with non-loss areas of rice yield. In terms of time period, the future rice yield loss rate showed an increasing trend under both scenarios. In the long term, the rice yield loss rate in Jianghuai region basically disappeared, and only a small part of the non-drought risk area remained in the Hengduan Mountains. The rice yield loss rate was the highest in the middle part of northeast China, which needs to be taken precautions. Comparing today and the future yield loss rate, there are great changes in many parts of the rice-growing areas, including northeast of the central region, the Sichuan basin, and south of Nanling region, and an increasing crop yield loss rate of the Yangtze river basin, where the rice planting area is great and the drought disaster risk is high, while the southwest region of crop yield loss rate change is small. This may be related to the good vegetation coverage and lower rice cultivation in southwest China. From the perspective of the scenario, the rice loss rate in each period under the RCP8.5 scenario was higher than that under the RCP4.5 scenario, especially in the short term.

Figure 12.

Rice yield loss rate under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. (a) Baseline (1975–2020), (b) short-term risk (2031–2050) in RCP4.5 scenario, (c) medium-term risk (2051–2070) in RCP4.5 scenario, (d) long-term risk (2071–2090) in RCP4.5 scenario, (e) short-term risk (2031–2050) in RCP8.5 scenario, (f) medium-term risk (2051–2070) in RCP8.5 scenario, (g) long-term risk (2071–2090) in RCP8.5 scenario. Regions in red indicate high yield loss rate (high risk); regions in green indicate low yield loss rate (low risk).

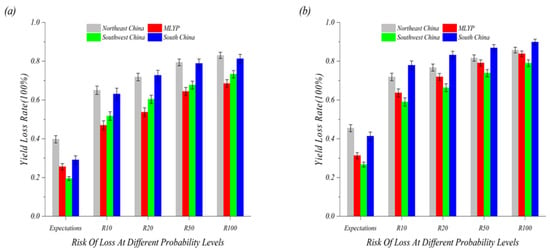

In order to compare rice drought risk in different regions, we calculated the mean and standard error of risk values of all grids in northeast China, MLYP, southwest China, and south China in the future period (2031–2090) and used them as regional risk indicators to characterize the relative magnitude of drought risk in different regions (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Regional risk index statistics for 2031–2090 under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. (a) Risk index statistics under RCP4.5 scenario, (b) risk index statistics under RCP8.5 scenario. We divided the MRACs into four regions and calculated the expected loss rate, drought loss rate once in 10 years, drought loss rate once in 20 years, drought loss rate once in 50 years, and drought loss rate once in 100 years of the four regions.

On the whole, the risk under the RCP4.5 scenario was lower than that under the RCP8.5 scenario. Northeast China and south China were more exposed to drought risk, and the expected rice drought risk loss rate was higher. The expected yield loss rate in northeast China was the highest among the four regions, with a projected yield loss rate of 39.75% and 45.5% under RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, respectively. However, under the RCP8.5 scenario, south China will face more than an 80% drought risk loss rate in different return periods. It is worth noting that under RCP4.5, the risk of drought recurrence in northeast China is greater than that in south China, while under RCP8.5, it is greater in south China, and the same situation also occurs between MLYP and southwest China.

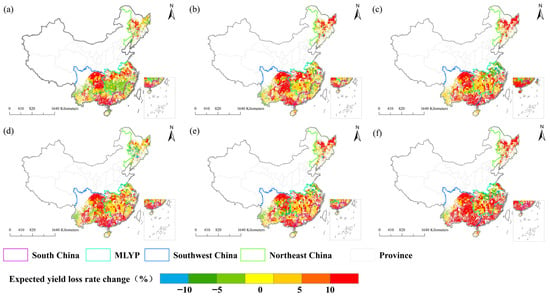

3.4.3. Expected Yield Loss Rate Change in the Future

We compared the expected drought-induced rice yield loss rates under future scenarios with the baseline, as shown in Figure 14. Temporally, under both the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios, the yield loss rate in most regions showed a clear increasing trend from the short-term (2031–2050) to the long-term (2071–2090). Especially under RCP8.5, most regions across the country exhibited more pronounced increases in risk, except for some areas in the MLYP. This indicates that the high-emission scenario leads to more widespread and severe drought-induced yield losses, with growing negative impacts on future rice production over time.

Figure 14.

Rice expected yield loss rate change in the future. (a) Short-term future (2031–2050) in RCP4.5 scenario relative to baseline, (b) medium-term future (2051–2070) in RCP4.5 scenario relative to baseline, (c) long-term future (2071–2090) in RCP4.5 scenario relative to baseline, (d) short-term future (2031–2050) in RCP8.5 scenario relative to baseline, (e) medium-term future (2051–2070) in RCP8.5 scenario relative to baseline, (f) long-term future (2071–2090) in RCP8.5 scenario relative to baseline. Regions in red indicate increased risk and regions in green indicate risk decreases in the future.

Spatially, major rice-producing regions such as south China and southwest China showed varied responses to drought. Southwest China consistently displayed an upward trend in risk across multiple periods and scenarios, particularly in eastern Sichuan, Chongqing, and Guizhou. In contrast, northeast China showed a decrease in risk under some scenarios. As global temperatures rise, high-latitude regions like the northeast may become more suitable for rice growth, especially around 2031–2050, where drought may have a limited impact. The MLYP region, a key rice-producing area, showed declining risk in many areas under RCP4.5, but this becomes increasingly rare under RCP8.5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Uncertainty in the Risk Assessment

This study focuses on both historical and future climate-related risk patterns, aiming to evaluate the evolution of drought hazards and their impacts on crop production under climate change. In terms of drought risk, our results are highly consistent with previous studies, which indicate that drought severity and frequency are projected to increase significantly in northeastern and southwestern China during the early-to-mid 21st century based on CMIP6 multi-model simulations [34]. Moreover, pronounced interdecadal variability in drought occurrence has been reported at the national scale, with a marked intensification during the 2000s and 2010s [35], further supporting our findings of increasing drought risk in the near future.

From the perspective of crop impacts, our projected spatial patterns of rice yield loss are also in good agreement with existing studies. Previous research suggests that northeastern and southwestern China are likely to experience the most severe rice yield reductions under future warming due to compounded thermal and water stress [36]. In addition, the exposure of rice to compound drought–heat extremes is expected to intensify in MLYR and southwestern China [37], which corroborates our conclusion that areas with severe yield loss will expand under future climate scenarios. The strong consistency between these external findings and our short-term (2031–2050) projections enhances the credibility of the risk patterns simulated by the EPIC model.

In order to accurately simulate crop yield, this study adjusted WA, HI, DLAI, DLMA, and PHU among 56 EPIC crop parameters based on existing studies [28,38,39]. In the calibration process, a machine learning method was used to make the computer automatically judge the direction and step size of the adjustment parameters, and the crop yield after calibration was in good agreement with the observed yield. However, yield is usually the result of the mutual compensation of gross primary production, soil dynamics, respiration, and photosynthate distribution during crop growth, and model verification based on yield simulation results will still produce certain uncertainties [40]. However, this paper mainly relies on yield loss rate to carry out crop disaster risk assessment. Therefore, in the case of accurate yield simulation, uncertainties of other factors have limited influence on the assessment results of this paper. However, if more accurate crop growth simulation is needed to guide agricultural planting and fine crop management, it is still recommended to calibrate the relevant parameters of other crop elements. In addition, different crop models have their own advantages in simulation performance in a certain region [41]. The cross-validation of simulation results by using multiple models in the future can reduce the uncertainty of evaluation results caused by systematic errors to a certain extent and help improve the prediction accuracy [42].

Some scholars compared the performance of CMIP6 and CMIP5 in drought recognition and found that CMIP6 had a stronger ability to capture drought in historical periods than CMIP5, which may be related to the improvement of the spatial resolution of the CMIP6 model. The CMIP6 medium–low emission scenario detects a longer drought duration in the mid-21st century, which cannot be detected based on the CMIP5 emission scenario, which may lead to changes in the response to rice drought risk in the near future described in this paper. However, in general, the CMIP6 model is better than CMIP5 in temperature capture, but most models under the CMIP6 model have no significant difference with the CMIP5 model [43]. In addition, small differences in warming projections (including temperature, precipitation, CO2, etc.) from different climate models may have some impact on the overall risk pattern [44,45,46]. Therefore, in view of the deviation of risk assessment caused by a single model and a single climate model, we believe that integrated multi-crop models and multi-climate models are conducive to reducing the uncertainty of risk assessment [47,48,49,50].

The response of rice to the same drought intensity was different at different stages of growth, which showed that the final yield loss rate varied with water stress at different stages of growth. The results showed that water stress had a significant effect on the final yield of Nerica 4 rice at the early stage of the vegetative stage or reproductive stage, while water stress had no significant effect on the final yield at the flowering stage and filling stage [51]. This indicated that further optimization was needed in the characterization of drought intensity, and the expression function of water stress in different growth stages on the drought intensity of rice in the whole growth stage was derived. However, it is difficult to determine the mechanism of water stress at the different growth stages of rice and the quantitative effect of water stress on the overall drought intensity. Therefore, it is necessary to explore models that can better reflect the characteristics of each crop growth stage in order to show the response of each growth stage to drought [52].

4.2. Rice Drought Risk and Food Security

The spatial heterogeneity of rice drought risk is closely associated with the complexity of rice-growing environments. Differences in soil conditions, terrain characteristics, and local climate jointly shape the vulnerability of rice to drought stress. Previous studies have shown that soil chemical properties—including pH, total C and N, electrical conductivity, and available P—significantly influence grain yield [53]. Rice yield also exhibits strong spatial interactions with soil texture; in regions dominated by heavy clay, the inherent nutrient status supports relatively high yield levels [54], consistent with the findings reported by Dou F. Terrain factors such as altitude and slope indirectly affect rice yield through their regulation of water and heat redistribution. As altitude increases, the effective accumulated temperature required for rice development declines, while the risk of low-temperature injury rises. Consequently, the growth duration becomes prolonged, and both seed-setting rate and panicle number decrease, ultimately resulting in yield reduction [55].

Climate conditions further contribute to regional differences in drought risk. Rice-growing areas in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River Plain (MLYP) and south China are strongly influenced by the monsoon system and receive substantially higher annual precipitation than northeast China. Nevertheless, under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios, the projected increase in drought risk is smaller in northeast China. This may be attributed to a larger projected increase in future precipitation in northern China, which partially offsets drought intensification [56].

China is a major food producer and consumer. Food security is the top priority for China’s social stability and future development. China’s current situation of grain production shows that its comprehensive agricultural production capacity is constantly improving, and the supply capacity of grain crops and cash crops is also significantly strengthened. It is predicted that the self-sufficiency rate of grain in China will reach 88% in the next ten years, but the pressure of grain production is great. China currently has a low level of grain shortage and surplus grain supply and demand structure due to the increasing population density and regional demand for grain increases. However, in the process of economic development, a large amount of cultivated land is occupied, resulting in a decrease in grain output, resulting in a grain gap in the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, the Yangtze River Delta, and the Pearl River Delta economic zone, and exacerbating the contradiction between grain supply and demand [57].

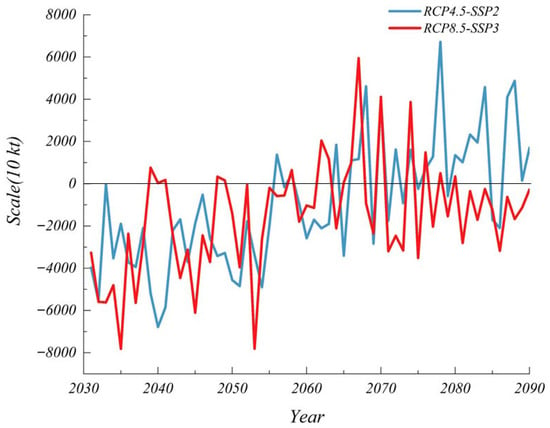

In the context of future climate instability, an increased risk of food loss due to climate change may lead to supply–demand conflict. As the main food crop, rice plays an important role in maintaining national food security. According to the per capita consumption of rice in China in 2019 and the forecast of the future population growth in China after the full liberalization of family planning under the SSP2 and SSP3 scenarios [58], the supply–demand relationship of rice in China under drought risk in the future period (2030–2090) under the RCP4.5-SSP2 scenario and the RCP8.5-SSP3 scenario was calculated (Figure 15). On the whole, China will face the problem of intensified contradiction between the supply and demand of rice caused by drought risk in the future, especially in the near future. The period from 2030 to 2055 will be a period of a severe rice gap in China. The maximum grain gap under the RCP4.5-SSP2 and RCP8.5-SSP3 scenarios is expected to reach 67,770 kT and 78,110 kT, respectively, and there will be two peak values of the gap under the RCP8.5-SSP3 scenario around 2035 and 2053. This shows that China needs to adjust its food security strategy in a timely manner and increase drought-resistant irrigation facilities and grain reserves. After 2055, the crisis of rice supply and demand under drought risk in China is greatly reduced compared with the near future, but it still has great volatility.

Figure 15.

Relationship between expected future rice production and rice consumption under drought risk in MRACs. A positive value indicates greater output than consumption (surplus grain); a negative value indicates less production than consumption (the grain gap).

5. Conclusions

Based on the EPIC model, this study simulated rice yield and daily water stress, quantitatively evaluated China’s rice drought vulnerability index, fitted and verified a vulnerability curve, and aimed to quantify the future rice drought risk in China and provide theoretical guidance for guaranteeing food security, improving food yield, and regional disaster prevention and reduction. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) The high incidence areas of drought events in China are mainly concentrated in the southwest of northeast China, the north of MLYP, and the south of south China. The overall distribution characteristics of drought hazard are low in the middle and high in the north and south.

(2) The occurrence probability of drought events in rice-growing areas increased with the increase in return period, especially in the surrounding areas of central and south China. At the same time, the area with a high disaster hazard increased with the increase in the return period, especially under the 100-year drought probability. The probability of drought events with different return periods was more than 90%. The intensity of drought-induced disaster increased with the increase in return period, and the area without rice yield loss decreased, while the area with high yield loss increased, especially in southwest China and the Yangtze River Basin.

(3) The risk in different regions under the RCP4.5 scenario is lower than that under the RCP8.5 scenario. Northeast China and south China are facing a higher risk of drought, and the uncertainty and variability of disaster occurrence will also increase significantly. The rice drought risk loss rate in northeast China will be higher in the future, and the expected yield loss rate under the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios will be 39.75% and 45.5%, respectively. Under the RCP8.5 scenario, the drought risk loss rate of different drought return periods in south China will reach more than 80%.

(4) The contradiction between the supply and demand of rice in China under the influence of drought risk in the near future is expected to be extremely prominent, with a maximum gap of 67,770 kt and 78,110 kt in the RCP4.5-SSP2 scenario and RCP8.5-SSP3 scenario, respectively, occurring around 2035, 2040, and 2053. In the future medium and long term, the contradiction between rice supply and demand will be greatly alleviated.

A physical vulnerability curve can quantitatively express the impact of different drought intensities on crop yield, and each basic assessment unit has a unique value of risk, which has a certain physical significance, which is helpful to improve the understanding of drought risk. Accurate and quantitative drought risk prediction can help agricultural producers improve their drought preparedness, such as through the use of appropriate irrigation measures to meet crop water needs; provide drought monitoring and early warning information for government managers; and improve drought warning ability and material reserve ability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and H.G.; methodology, T.L.; software, T.L.; validation, T.L., H.D., and Y.L.; formal analysis, H.D.; investigation, H.D., W.C.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, T.L., W.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.L., W.C.; writing—review and editing, H.G.; visualization, H.D.; supervision, H.G.; project administration, H.G.; funding acquisition, H.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42201087, the National Key Research and Development Program of China, grant number 2024YFE0214000, and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Provincial, grant number LQ21D010009.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to extend our heartfelt gratitude to the Editor and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable contributions in improving this paper. We also appreciate the efforts of all the participants. This study is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 42201087), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFE0214000), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Provincial (Grant No. LQ21D010009).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis [M/OL]. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Full_Report.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- UNDRR. GAR Special Report on Drought 2021: A Summary for Policy Makers; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; Available online: https://www.undrr.org/publication/gar-special-report-drought-2021 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Zhang, H.; Yang, X.; Ren, L.; Wu, F.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y. Response of typical large-scale persistent drought events to atmospheric circulation in China. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. (Trans. CSAE) 2024, 40, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouman, B.A.M.; Humphreys, E.; Tuong, T.P.; Barker, R. Rice and Water. In Advances in Agronomy; Sparks, D.L., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2007; Volume 92, pp. 187–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Xiao, X.; Biradar, C.M.; Dong, J.; Qin, Y.; Menarguez, M.A.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, C.; Wang, J.; et al. Spatiotemporal patterns of paddy rice croplands in China and India from 2000 to 2015. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 579, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Chang, J.; Guo, A.; Zhou, K. Characterizing spatio-temporal patterns of multi-scalar drought risk in mainland China. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 131, 108189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Zang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lv, H.; Yan, D. Study on spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of flood and drought disaster impacts on agriculture in China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 64, 102504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, W.H.; Hayes, M.J.; Svoboda, M.D.; Tadesse, T.; Wilhite, D.A. Drought hazard assessment in the context of climate change for South Korea. Agric. Water Manag. 2015, 160, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arab, S.T.; Noguchi, R.; Ahamed, T. Yield loss assessment of grapes using composite drought index derived from Landsat OLI and TIRS datasets. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2022, 26, 100727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Wu, J.; Lü, A.; Cui, X.; Zhou, L.; Liu, M.; Zhao, L. Quantitative assessment and spatial characteristic analysis of agricultural drought risk in China. Nat. Hazards 2013, 66, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhu, X.; Shen, Z.; Yu, H. Drought risk assessment in China: Evaluation framework and influencing factors. Geogr. Sustain. 2020, 1, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gao, J.; Tang, Z.; Jiao, K. Quantifying the ecosystem vulnerability to drought based on data integration and processes coupling. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 301, 108354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Xu, K.; Liu, Y.; Guo, R.; Chen, L. Assessing the vulnerability and risk of maize to drought in China based on the AquaCrop model. Agric. Syst. 2021, 189, 103040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Geological Survey (USGS). Global 30 Arc-Second Elevation (GTOPO30). Available online: https://lta.cr.usgs.gov/GTOPO30 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Global Agro-ecological Zones (GAEZ). Terrain Slope Classes. Available online: http://www.gaez.iiasa.ac.at/ (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Batjes, N.H. ISRIC-WISE Derived Soil Properties on a 5 by 5 Arc-Minutes Global Grid (ver. 1.2); ISRIC-World Soil Information: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2012; Report No. 2012/01; Available online: https://data.isric.org/geonetwork/srv/eng/catalog.search#/metadata/82f3d6b0-a045-4fe2-b960-6d05bc1f37c0 (accessed on 1 August 2021).

- Hempel, S.; Frieler, K.; Warszawski, L.; Schewe, J.; Piontek, F. A trend-preserving bias correction—The ISI-MIP approach. Earth Syst. Dyn. 2013, 4, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, R.; Pan, B.; Peng, Q.; Dong, J.; Chen, X.; Zhang, X.; Ye, T.; Huang, J.; Yuan, W. High-resolution distribution maps of single-season rice in China from 2017 to 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 2023, 15, 3203–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacks, W.J.; Deryng, D.; Foley, J.A.; Ramankutty, N. Crop planting dates: An analysis of global patterns. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 2010, 19, 607–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Shibasaki, R. Global estimation of crop productivity and the impacts of global warming by GIS and EPIC integration. Ecol. Model. 2003, 168, 357–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, P.; Ramankutty, N.; Bennett, E.M.; Donner, S.D. Characterizing the spatial patterns of global fertilizer application and manure production. Earth Interact. 2010, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Zhang, R.; Xie, N.; Jin, J. Predicting the population growth and structure of China based on grey fractional-order models. J. Math. 2021, 2021, 7725125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, K. Quantifying storm tide risk in Cairns. Nat. Hazards 2003, 30, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutter, S.L. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996, 20, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, F.; Fang, W.; Liao, Y. Assessment of physical vulnerability to agricultural drought in China. Nat. Hazards 2013, 67, 645–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Du, T.; Mao, X.; Ding, R.; Shukla, M.K. A comprehensive method of evaluating the impact of drought and salt stress on tomato growth and fruit quality based on EPIC growth model. Agric. Water Manag. 2019, 213, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, K.N.; Jha, M.K.; Reyes, M.R.; Jeong, J.; Doro, L.; Gassman, P.W.; Hok, L.; Sá, J.C.d.M.; Boulakia, S. Evaluating carbon sequestration for conservation agriculture and tillage systems in Cambodia using the EPIC model. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2018, 251, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.C.; Li, J. Evaluation of crop yield and soil water estimates using the EPIC model for the Loess Plateau of China. Math. Comput. Model. 2010, 51, 1390–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, L.; Jiang, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Review of application of EPIC crop growth model. Ecol. Model. 2022, 467, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Balkovič, J.; van der Velde, M.; Zhang, X.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Skalský, R.; Lin, E.; Mueller, N.; Obersteiner, M. A calibration procedure to improve global rice yield simulations with EPIC. Ecol. Model. 2014, 273, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billen, N.; Röder, C.; Gaiser, T.; Stahr, K. Carbon sequestration in soils of SW-Germany as affected by agricultural management—Calibration of the EPIC model for regional simulations. Ecol. Model. 2009, 220, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Huang, G.; Yu, C.; Ni, S.; Yu, L. A multiple crop model ensemble for improving broad-scale yield prediction using Bayesian model averaging. Field Crops Res. 2017, 211, 114–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Williams, J.R.; Gassman, P.W.; Baffaut, C.; Izaurralde, R.C.; Jeong, J.; Kiniry, J.R. EPIC and APEX: Model use, calibration, and validation. Trans. ASABE 2012, 55, 1447–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, P.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, T.; Li, N. Regional inequalities of future climate change impact on rice (Oryza sativa L.) yield in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Dong, S.; Han, Z.; Li, W. Increased exposure of rice to compound drought and hot extreme events during its growing seasons in China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 167, 112735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Qu, Y.; Bento, V.A.; Song, H.; Qiu, J.; Qi, J.; Wan, L.; Zhang, R.; Miao, L.; Zhang, X.; et al. Understanding climate change impacts on drought in China over the 21st century: A multi-model assessment from CMIP6. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2024, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, Q.; Chen, H. Changes in drought characteristics over China during 1961–2019. Front. Earth Sci. 2023, 11, 1138795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choruma, D.J.; Balkovic, J.; Pietsch, S.A.; Odume, O.N. Using EPIC to simulate the effects of different irrigation and fertilizer levels on maize yield in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 254, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folberth, C. Modeling Crop Yield and Water Use in the Context of Global Change with a Focus on Maize in Sub-Saharan Africa. Doctoral Dissertation, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Elliott, J.; Chryssanthacopoulos, J.; Arneth, A.; Balkovic, J.; Ciais, P.; Deryng, D.; Folberth, C.; Glotter, M.; Hoek, S.; et al. Global gridded crop model evaluation: Benchmarking, skills, deficiencies and implications. Geosci. Model Dev. 2017, 10, 1403–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhan, C.; Hu, S.; Ning, L.; Wu, L.; Guo, H. Evaluation of global gridded crop models (GGCMs) for the simulation of major grain crop yields in China. Hydrol. Res. 2022, 53, 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostková, M.; Hlavinka, P.; Pohanková, E.; Kersebaum, K.C.; Nendel, C.; Gobin, A.; Olesen, J.E.; Ferrise, R.; Dibari, C.; Takáč, J.; et al. Performance of 13 crop simulation models and their ensemble for simulating four field crops in Central Europe. J. Agric. Sci. 2021, 159, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Tao, F. ChinaCropPhen1km: A High-Resolution Crop Phenological Dataset for Three Staple Crops in China during 2000–2015 Based on Leaf Area Index (LAI) Products. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2020, 12, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Franke, J.; Jägermeyr, J.; Ruane, A.C.; Elliott, J.; Moyer, E.; Heinke, J.; Falloon, P.D.; Folberth, C.; Francois, L.; et al. Exploring uncertainties in global crop yield projections in a large ensemble of crop models and CMIP5 and CMIP6 climate scenarios. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 034040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, J.; Lin, E.D.; Wheeler, T.; Challinor, A.; Jiang, S. Climate change modelling and its roles to Chinese crop yields. J. Integr. Agric. 2013, 12, 892–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Palosuo, T.; Rötter, R.P.; Díaz-Ambrona, C.G.H.; Mínguez, M.I.; Semenov, M.A.; Kersebaum, K.C.; Cammarano, D.; Specka, X.; Nendel, C.; et al. Why do crop models diverge substantially in climate impact projections? A comprehensive analysis based on eight barley crop models. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2020, 281, 107851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, L. Higher contributions of uncertainty from global climate models than crop models in maize-yield simulations under climate change. Meteorol. Appl. 2019, 26, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. Information diffusion techniques and small-sample problem. Int. J. Inf. Technol. Decis. Mak. 2002, 1, 229–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruane, A.C.; Phillips, M.; Müller, C.; Elliott, J.; Jägermeyr, J.; Arneth, A.; Balkovic, J.; Deryng, D.; Folberth, C.; Iizumi, T.; et al. Strong regional influence of climatic forcing datasets on global crop model ensembles. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2021, 300, 108313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirono, D.G.C.; Kent, D.M.; Hennessy, K.J.; Mpelasoka, F. Characteristics of Australian droughts under enhanced greenhouse conditions: Results from 14 global climate models. J. Arid Environ. 2011, 75, 566–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alou, I.N.; Steyn, J.M.; Annandale, J.G.; Van der Laan, M. Growth, phenological, and yield response of upland rice (Oryza sativa L. cv. Nerica 4®) to water stress during different growth stages. Agric. Water Manag. 2018, 198, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Su, L.; Tao, W.; Wang, Q.; Deng, M. Integrated growth model of typical crops in China with regional parameters. Water 2022, 14, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanai, J.; Lee, C.K.; Kaho, T.; Iida, M.; Matsui, T.; Umeda, M.; Kosaki, T. Geostatistical analysis of soil chemical properties and rice yield in a paddy field and application to the analysis of yield-determining factors. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2001, 47, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüth, B.; Lennartz, B. Spatial variability of soil properties and rice yield along two catenas in southeast China. Pedosphere 2008, 18, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.W. Analysis on yield components of japonica rice in different altitude areas. China Rice 2015, 21, 75–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Chen, L.; Ma, Z. Simulation of historical and projected climate change in arid and semiarid areas by CMIP5 models. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2014, 59, 412–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Ju, Z.S.; Zhou, W. Regional pattern of grain supply and demand in China. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2016, 71, 1372–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Su, B.; Jing, C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.; Guo, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Luo, Y. National and provincial population and economy projection databases under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways(SSP1-5)_v2 [DS/OL]. Sci. Data Bank 2022. Available online: http://cstr.cn/31253.11.sciencedb.01683 (accessed on 21 May 2022).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).