1. Introduction

Avalanches frequently occur in the steep hillsides of the mountains near Longyearbyen, Svalbard [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Mostly these avalanches have no harmful or damaging effects and have been regarded as part of natural processes in steep, high Arctic mountains. In early June, 1953, an ice avalanche that hit Longyearbyen killed three people, injured nine others, and destroyed several houses, including the hospital [

6]. In this article, we describe the dramatic snow avalanche events on 19 December 2015 [

7] and 21 February 2017 that had a major impact on Longyearbyen’s society. We outline the meteorological conditions preceding the impacts and give an account of the major snow avalanche that hit Longyearbyen Saturday morning, 19 December 2015. Through modern communication and social media, the event received national attention and coverage, which had to be handled while the rescue operation and its aftermath were unfolding.

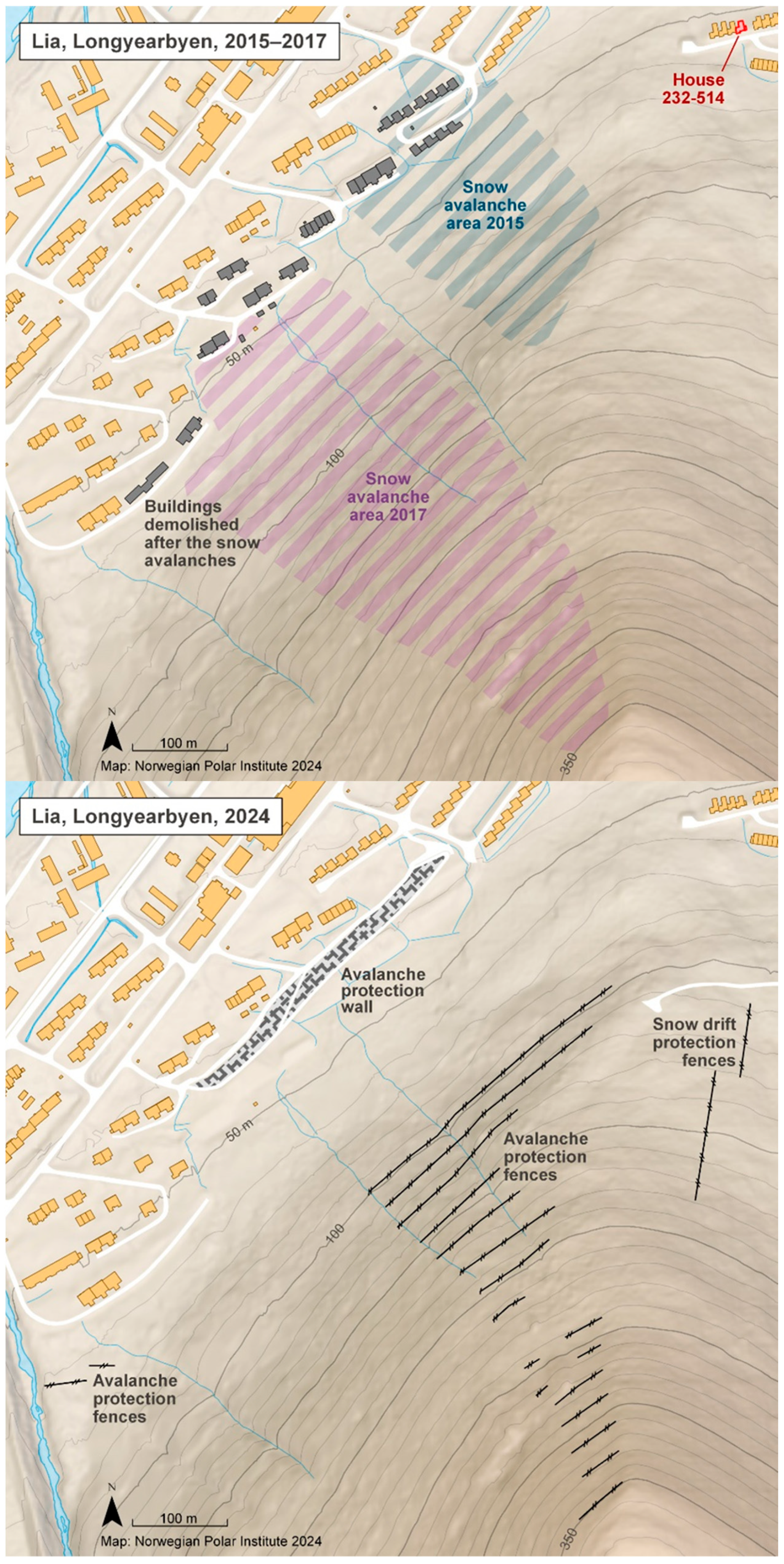

The snow avalanches in 2015 and 2017 occurred on the steep hillside of the mountain Sukkertoppen and destroyed houses in the settlement Lia at the foot of the mountain (

Figure 1).

Lia has been exposed to natural hazards such as avalanches, mudflows, and rockfalls since the area was built in the early 1970s. Research on snow conditions leading up to the avalanche has been conducted there in the last decade [

1,

8,

9,

10]. The area has been used as a regular field site for student courses on snow physics at the University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) for more than 20 years. Reports from the Norwegian Geotechnical Institute (NGI, [

11,

12]) have indicated the possibility of extreme avalanches from Sukkertoppen continuing beyond the highest located rows of houses. For more than 15 years, student assignments at UNIS have focused on avalanche release and runout in Sukkertoppen, using well-established empirical and dynamic avalanche models. Student reports from courses on ‘Infrastructures in a changing climate’ (given at both the bachelor and master’s level) have used models such as the NGI’s empirical model (α–β model [

13,

14]), the Austrian Elba+ model [

15], and the Swiss RAMMS model [

16,

17]. By using these models, the students have reached the same conclusion, confirming earlier reports that the maximum runout of avalanches would go beyond the upper rows of the houses in Lia. These conclusions have been confirmed by specialists from the Swiss Federal Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research, who have developed the RAMMS model and have participated in teaching at UNIS in the course Arctic Technology 301 (Infrastructures in a changing Climate).

Warnings concerning the possible danger that a major snow avalanche in the area could have a severe impact on houses in Longyearbyen have been given to the local authorities (e.g., to representatives from the Development Department of the Local Board of Longyearbyen during the course Arctic Technology 205 Frozen Ground Engineering at UNIS in February 2011, ref. [

7]). Since the early nineties, there have been substantial changes in the administrative responsibility and management of Longyearbyen [

18], with a high turnover rate (citizens are residents for an average of about five years). Therefore, it seems that information about the snow avalanche risk for the houses at the foot of Sukkertoppen has passed through the administrative and management system without causing any initiatives that would have had a mitigating effect.

Actions and plans to establish an avalanche forecast system were established in 2016 after the 2015 accident. A trial with a regional forecast system run by the Norwegian Water and Energy Directorate (NVE), with local observations submitted by observers in Longyearbyen, was conducted in the spring of 2015. However, by December, no snow avalanche warning system was in place; there were no preventive constructions, and no houses had been moved to avalanche-safe sites. Therefore, the snow avalanche merely had the predicted impact [

19].

We review the events and discuss the aftermath to mitigate the snow avalanche danger for steep hillsides in the Arctic. This is performed in the context that the ultimate role of scientists is to aggregate and synthesise knowledge through their own observations and experiments, or by modelling and communicating it to peers, students, and society [

20]. The knowledge-providing process should be independent of any constraints from an employer, bodies providing financial support, and interests related to business, society, and politics. However, it is not our intention to point to any irresponsible actors, be it persons, institutions, or organisations. Any legal aspects concerning the catastrophes we consider are beyond our competence. Rather, our aim is for the observations we describe to be used for future predictions of possible avalanche conditions and area regulations in mountain regions in the Arctic, to prevent impacts from avalanches. The necessity of more scientific focus on snow avalanches and the danger such events represent was highlighted in a recent perspective article on snow avalanche dynamic research [

21]. With global warming, geo mass movement-related hazards such as snow avalanches are expected to become increasingly frequent and severe [

22]. Events such as the fatal Rigopiano Avalanche in the Italian Alps in 2017 [

23] and the huge infrastructure damages caused by the Les Fonts d’Arinsal avalanche in the Pyrenees in 1996 [

24] illustrate the potential impact caused by snow avalanches.

2. The 19 December 2015 Snow Avalanche

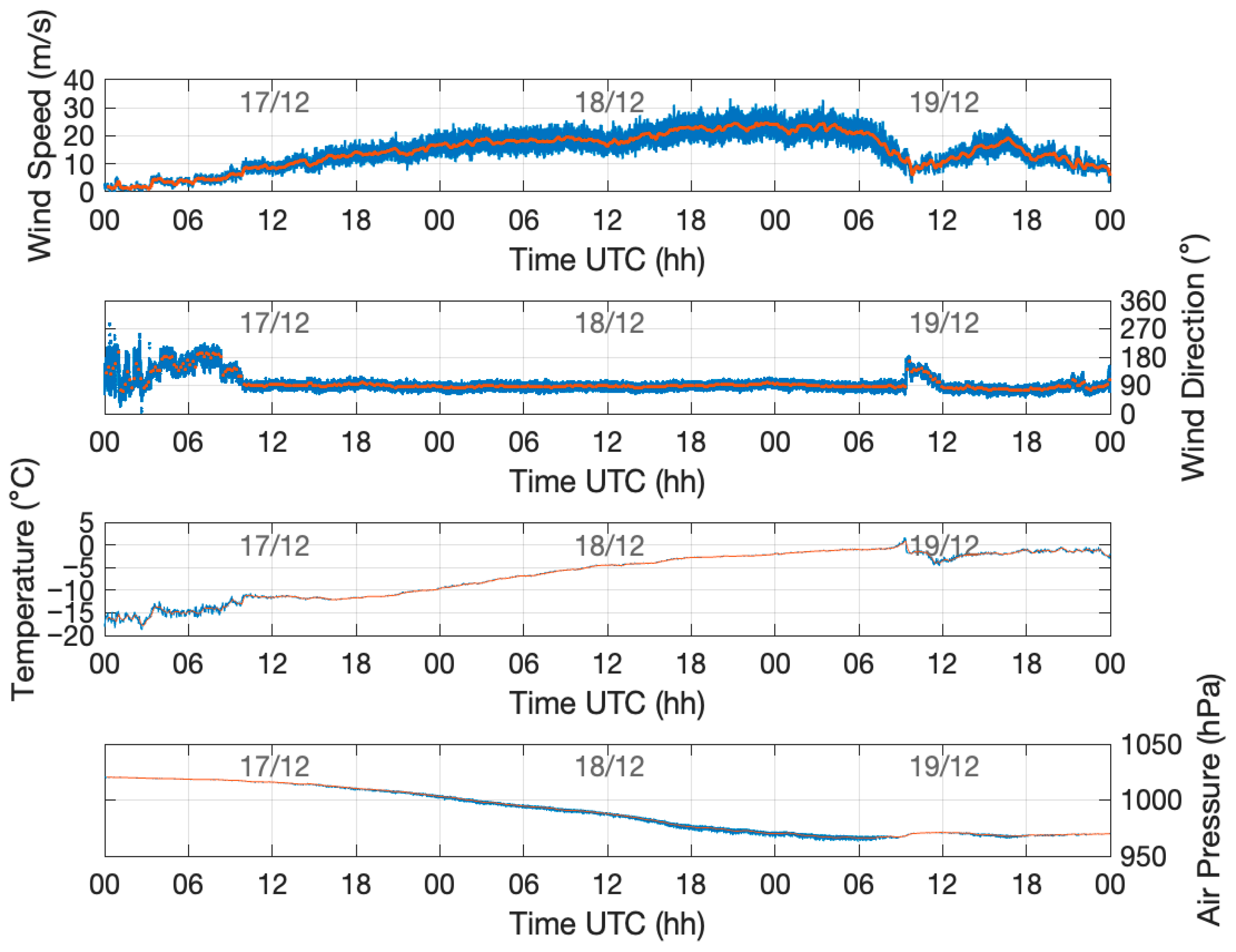

On the morning of 17 December 2015, the surface air pressure at the UNIS Adventdalen automatic weather station began decreasing, from 1020 hPa to 965 hPa the next morning (

Figure 2), indicating an approaching low pressure system. Within the same time frame, the wind speed picked up, going from below 5 m/s, with a somewhat erratic direction, and increasing to around 20 m/s, with gusts (1 s values) exceeding 30 m/s the next morning with a steady easterly component. The temperature increased from below −15 °C to around 0 °C. The wind was strong throughout Longyeardalen, and the onset of precipitation by the morning (06:00 UTC) of 18 December in the form of snow led to very poor visibility, which was exacerbated by the polar night (no daylight). As a result of these conditions, people who were in town report that moving about outdoors was very difficult, and flights to Svalbard Airport were cancelled that day. However, at Svalbard Airport, only 0.1 mm precipitation was recorded, and the snow depth was just 6 cm (

Table 1), since the snow was blowing away. At this time of year, the sun is always below the horizon at this northern latitude, there is nighttime darkness throughout the day, and only lights from the houses and the streets illuminate Longyearbyen.

The wind speed rapidly decreased starting 06:00 UTC on 19 December, and a minimum wind speed was observed of around 10 m/s close to midday (12:00 UTC). This wind minimum coincided with relatively warm temperatures (above freezing or slightly above) and a levelling-off in the air pressure to about 970 hPa. By 12:00 UTC, the conditions for moving about outdoors had improved significantly. People who were in town reported a large horizontal variability in the snow cover: some areas in town were almost bare, while others were filled with piles of snow of up to 2 m depth or more. This variability in snow cover also indicates a large variability in the local wind patterns, which is confirmed by considering the data from the network of automatic weather stations operated by UNIS in the area around Longyearbyen. For example, around midnight between 18 and 19 December—when the winds were near their peak—the station in Adventdalen measured sustained speeds of about 24 m/s, while a station at Breinosa (approximately 7 km to the southeast) recorded winds roughly 10 m/s lower.

At about 10:25 on Saturday 19 December 2015, the snow avalanche suddenly released from the steep hillside of Sukkertoppen [

7]. People who were outdoors did not hear any noise, even if the wind had calmed to a light breeze (

Figure 2). People in the houses hit by the snow avalanche heard a bang like an explosion and could describe how their houses were filled with snow. Observers could see the affected houses being pushed away and covered in a ‘snow cloud’. The fracture line was 2–4 m in height, about 200 m wide, and located about 300 m above the houses in the hillside (

Figure 3 and

Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). The avalanche had a volume of between 30,000 m

3 and 50,000 m

3 of snow.

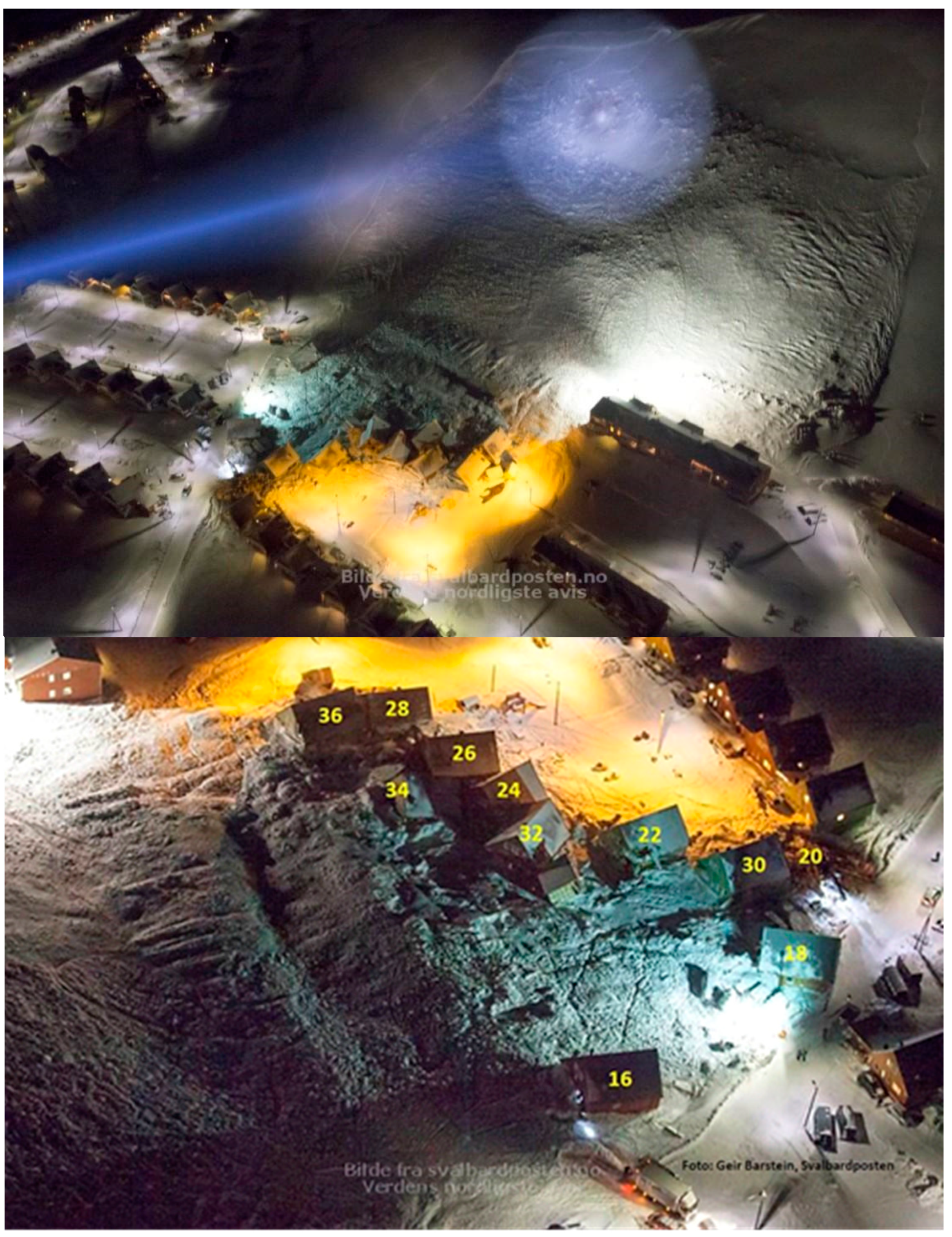

Eleven houses were destroyed by the avalanche (

Figure 3 and

Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). All the houses were built on wooden poles as a foundation in the frozen ground. As many as ten of the houses were pushed 10–80 m [

7], and one of the houses turned about 45° (house 16,

Figure 3 and

Figure S1 in Supplementary Materials). The kitchen and entrance of the house were destroyed and filled with snow. All the impacted houses were so badly damaged by the avalanche that they had to be condemned.

The Governor of Svalbard, the Longyearbyen Fire Brigade, and the Longyearbyen Red Cross were immediately alarmed about the snow avalanche, and staff from these units were quickly on site. A search and rescue operation was initiated, and volunteers coming to the site participated. One of the authors was living in house 232–514, only about 250 m from the snow avalanche site, and was among the many volunteers who met at the site and engaged in the search and rescue operation. Notes of the event were taken during the day.

As soon as information about missing persons was provided, search and rescue actions were conducted. Five people were rescued from the damaged kitchen of house 16 (

Figure 3), as was a lady from the damaged kitchen of house 32 (

Figure 3). They were all brought to Longyearbyen Hospital less than 45 min after the avalanche hit their houses. A large group of volunteers were allowed onto the site at about 11:15 to replace people who were exhausted from the first digging operations. Two persons from house 36 were found about 2 h after the avalanche occurred, and the last missing person from house 34 was found below about 2 m of snow at about 13:30, nearly three hours after the avalanche.

The search and rescue operation at the site was conducted effectively and professionally. A site leader from the Governor’s office and deputies from Longyearbyen Fire Brigade and the Longyearbyen Red Cross organised the professional staff and the 100 or so volunteers in an effective operation through clear commands and actions [

25]. Chains of people were formed to dig and move large amounts of snow uphill in a dedicated search for people that were missing. Upon locating people that were missing, professionals from Longyearbyen Fire Brigade and the Longyearbyen Red Cross gave first aid and prepared the patients for transport to Longyearbyen Hospital, only a few minutes away. At about 13:45, the site leader declared the search and rescue operation over and ordered participants to congregate in the hallway of the commercial centre (Lompen) for food, drinks, and debriefing.

At about 11:20, one hour after the avalanche had hit Longyearbyen, it was a national news event, spreading across the Internet and Facebook. Some of us heard about it through these channels. When participating in the rescue operation, we were called by national newspapers. At 15:00 there was an extra news event on the NRK 1 TV channel in Norway. Pictures and footage from the rescue operation were broadcasted. Throughout Saturday 19 December 2015 and the following days, the avalanche in Longyearbyen was important news in the Norwegian media.

During the afternoon, it became clear that all the people hit by the avalanche had been found during the first part of the search and rescue operation. Many houses near the avalanche were evacuated, and the residents moved to other available apartments or were booked in at hotels in the town. At 21:30 Saturday evening, 19 December, the Governor of Svalbard arranged a debriefing for the participants in the search and rescue operation. An information meeting for the citizens of Longyearbyen was arranged at 22:30. The leaders of the rescue operation and the aftermath gave their versions of the event and answered questions from the audience. On Sunday 20 December, the Governor of Svalbard chaired a meeting for the citizens of Longyearbyen. In addition to the leaders of the rescue operation, the priest of the church of Svalbard was present and addressed the audience. At this stage, it was official that two people had died in the avalanche.

3. The 21 February 2017 Snow Avalanche

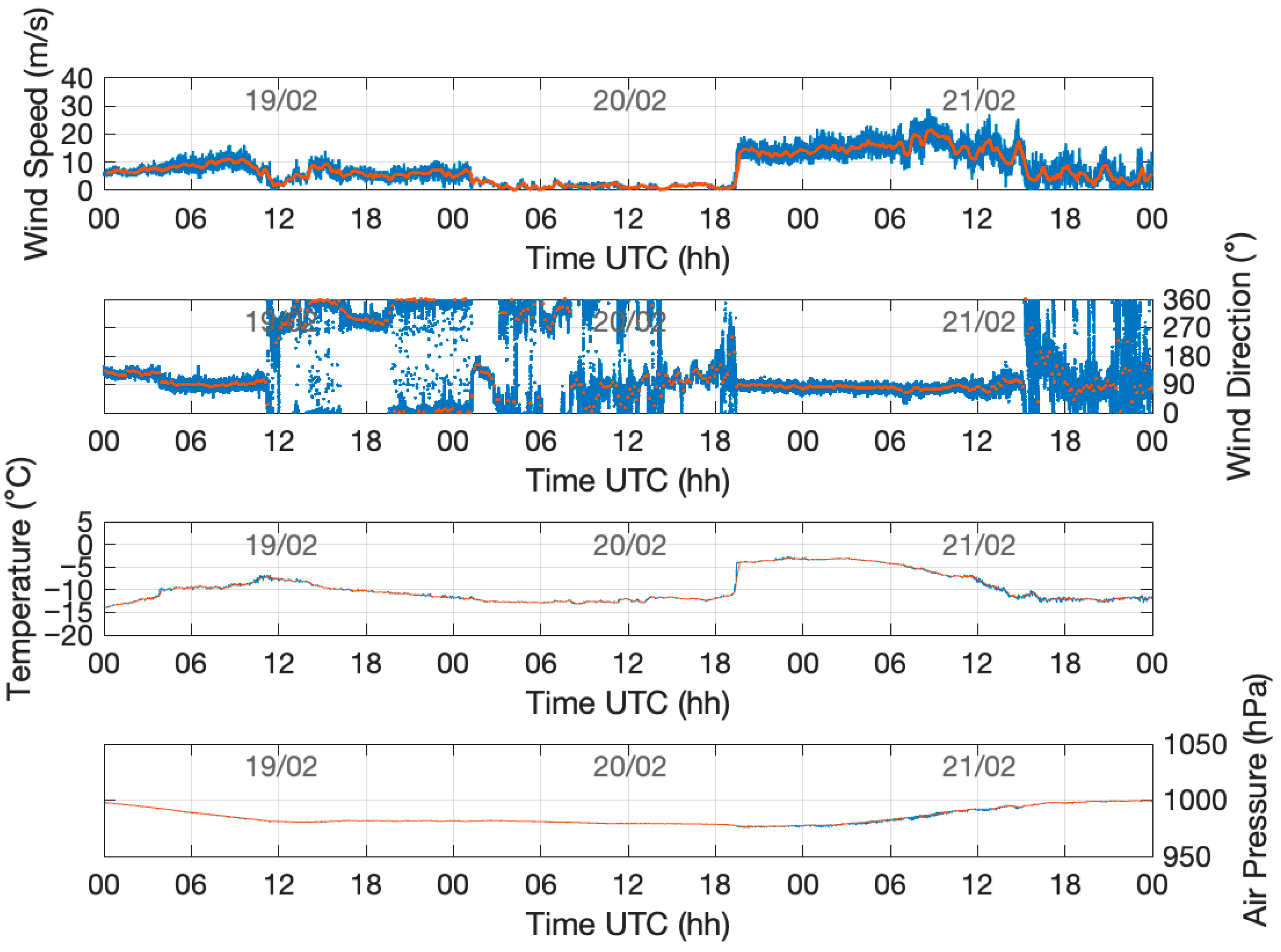

Surface air pressure records from the UNIS automatic weather station in Adventdalen (

Figure 4) indicate the passage of a low-pressure system over Svalbard between 19 and 21 February 2017. The pressure declined from approximately 1000 hPa early on 19 February to a minimum slightly below 980 hPa by 12:00 UTC, stabilising at this level until 00:00 UTC on 21 February before recovering to values around 1000 hPa. A distinct shift in wind and temperature occurred on 20 February. The initial conditions on the morning of 20 February featured low easterly winds (1–3 m/s) and temperatures between −13 °C and −12 °C. Around 19:00 UTC, both parameters increased abruptly. By the morning of 21 February, sustained winds (10 min average) peaked at about 22 m/s, with gusts (1 s values) up to 29 m/s. Concurrently, the temperature rose from around −12 °C to a maximum of about −3 °C by midnight. In terms of precipitation, 2.9 mm fell at Svalbard Airport between the morning of 20 February and the morning of 21 February (

Table 2). Simultaneously, the snow depth increased from 10 to 24 cm. By 18:00 UTC on 21 February, conditions moderated; sustained wind speeds decreased to below 10 m/s, and temperatures returned to approximately −12 °C.

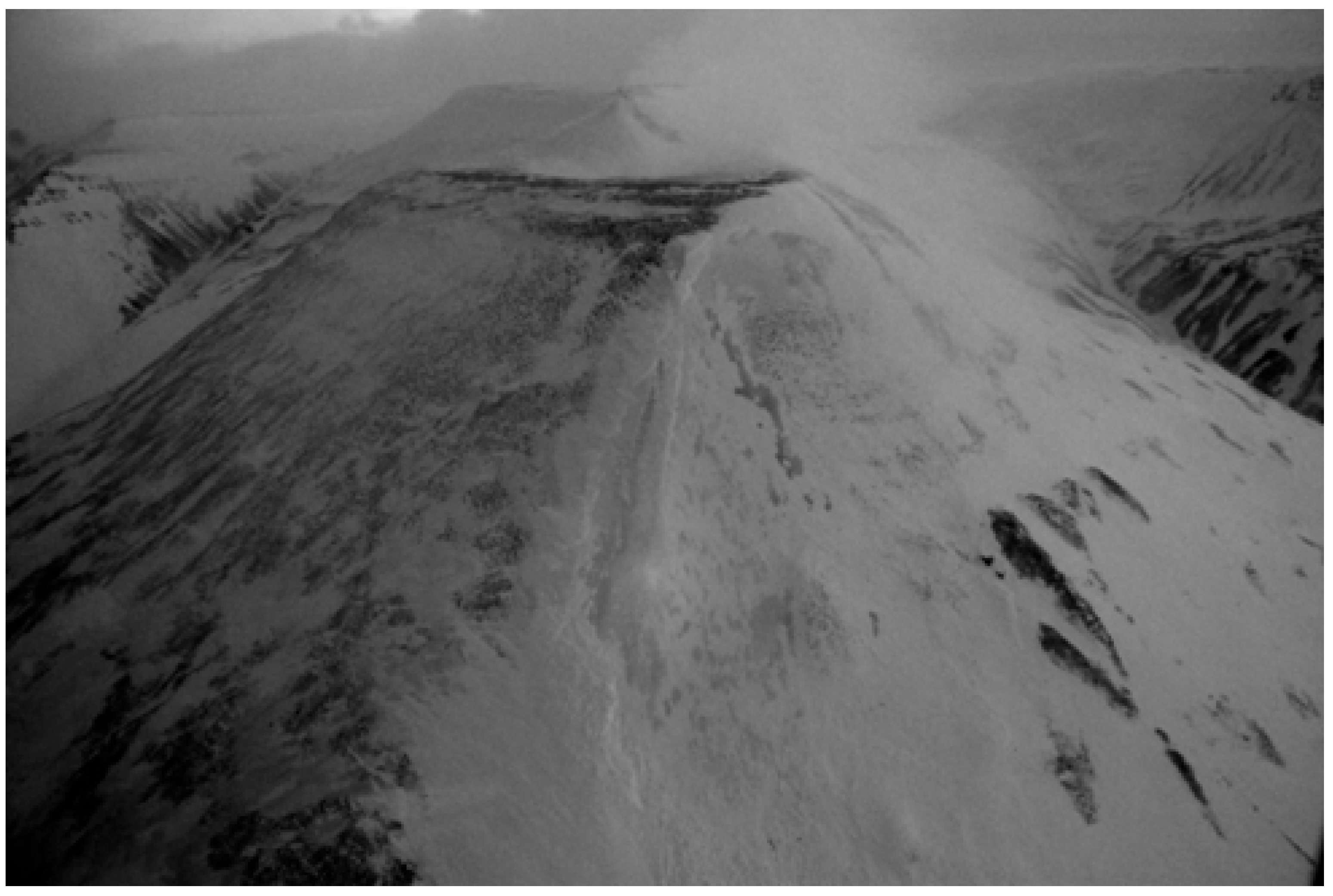

On 21 February 2017, at about 11:00 in the morning, a snow avalanche released in the highest part of the slope in Sukkertoppen, about 250 m higher than the avalanche in 2015 (

Figure 5) [

26]. Two apartment blocks on road 228, at the foot of the mountain, were hit, and at least six apartments were damaged (

Figure 6). No persons were injured, and most people were outside their homes. As described above, the avalanche came in connection with strong easterly winds and snowfall, and the NVE had issued a stage 4 avalanche warning for 21 February 2017. However, an evacuation of the houses in the danger zone at the foot of Sukkertoppen was not instigated. After the avalanche, some 200 people were evacuated.

Comparing the meteorological conditions leading up to the 2015 and 2017 avalanches reveals several noteworthy differences. The December 2015 case was characterised by a rapid pressure drop (>50 hPa in 24 h), strong and persistent easterly winds reaching ~20–24 m/s with gusts > 30 m/s a sharp temperature rise from −15 °C to 0 °C, and blowing snow that produced extremely poor visibility despite minimal measured precipitation. Local wind variability created highly uneven snow deposition, with some areas nearly bare and others accumulating >2 m of drifted snow. In contrast, the February event involved a more moderate pressure decline (~20 hPa), somewhat weaker initial winds, and a later, abrupt onset of strong winds that peaked near 22 m/s, alongside a temperature increase from −12 °C to −3 °C. The measured precipitation was substantially greater in 2015 than in 2017. In summary, both events featured warming, strong easterly winds, and drifting snow, but the December case exhibited a more extreme wind-driven redistribution of snow (

Figure S2).

5. Discussion

The slopes in Sukkertoppen, with exposure to the north-west, are a typical lee zone for the forecasted wind and received heavy snow accumulation during the 24 h between 18 and 19 December 2015. As avalanche hazards are directly related to snow accumulation intensity, the snow avalanche hazard was high in the morning of 19 December 2015. The slope above the settlement in Lia has an inclination of 30° to 35°, and is prone to the releasing of snow avalanches, as indicated in master’s (

Figure S2 in Supplementary Materials) and PhD theses at UNIS.

As the snow cover in the release area had been relatively moderate prior to the storm, and the temperature in Longyearbyen, in periods, had been well below freezing, it can be an indication of well-developed depth hoar at the bottom of the snowpack. This layer is extremely weak, and it seems to have been the ‘failure layer’ in the snow, as the whole snowpack was released in the avalanche [

25].

The snow avalanche on 19 December 2015 in Lia took a path consistent with the well-known avalanche runout models and just confirms that the NGI’s empirical model and the other dynamic models from Austria and Switzerland have validity in the Arctic environment in Svalbard [

5]. The results showed that houses at the foot of the mountain could be impacted, as happened in the snow avalanche on 19 December 2015 (figures given in

Supplementary Materials).

The snow avalanche probably had a velocity of between 10 and 15 m/s and a density of between 250 and 300 kg/m

3 when it hit the upper row of houses. This indicates a pressure of between 25 kPa and 68 kPa [

27,

28]. These houses, whose foundations are built on poles, are not designed for this pressure, and were thrown off their foundations or crushed by the impact pressure. Snow avalanches have released in the same area earlier and have been recorded with runout close to the upper row of houses since the settlement was raised in the early 1970s. This is the reason why NGI was hired to make a zoning plan in Longyearbyen in 2001–2003 [

11,

12].

The release of such an extreme snow avalanche was predicted, but the frequency of such events is relatively low [

29]. This means that the avalanche hazard in the same path as the avalanche that occurred on the morning of 19 December 2015 is low. The snow avalanche probability in the neighbouring areas, however, was high, and new minor avalanches were triggered further west in Lia and under the mountain Gruvefjellet without reaching inhabited areas.

Ref. [

29] concluded that the snow avalanche event in Longyearbyen on 19 December 2015 could have been easily forecasted if a snow avalanche forecasting system had been in place. In their analysis of 40 years of weather data from Svalbard, ref. [

29] found that similar weather events have occurred different times earlier. The conclusion was that ‘alarm bells should have sounded’ if any snow avalanche awareness system had been established. However, the authorities and citizens of Longyearbyen were not aware of the danger that was building in the steep hillside of Sukkertoppen during the severe snowstorm on 18–19 December 2015.

We could speculate about what may have happened if the Meteorological Institute had mentioned the risk of snow avalanches in their weather forecasts for Svalbard for 18–19 December 2015, and if the NVE had done the same through the formal avalanche warning system. Such warnings would then have had to be considered by the Governor of Svalbard and the local administration in Longyearbyen. If an avalanche warning was coupled with information about the known risk of snow avalanches in Sukkertoppen, we can speculate that an evacuation might have taken place. But, to our knowledge, such a connection was never made, unfortunately. In a recent review of the vulnerability and risk management of an Arctic settlement under changing climates being a challenge to authorities and experts, ref. [

19] rhetorically speculated on why no one acted based on the weather forecast of a heavy snowstorm with winds up to hurricane levels in wind gusts.

But the snow avalanche on the morning of 19 December 2015 made avalanche warnings in Longyearbyen a necessity. Soon after the termination of the rescue operation, local experts investigated the steep hillside of Sukkertoppen and concluded that the settlement Lia was still exposed to avalanche hazards. Therefore, a rather large area, with many houses situated at the foot of the mountain, was evacuated. During the evening hours of 19 December 2015, national snow avalanche experts came to Longyearbyen and joined the team of local snow avalanche professionals. In the following days, the snow avalanche risk in the Longyearbyen valley was regularly investigated, from helicopters and by foot. A formal snow avalanche warning system for parts of Svalbard (Nordenskiøld Land) including Longyearbyen, was established in early 2016 under the leadership of the NVE. This system has been further developed, especially after the February 2017 snow avalanche.

The avalanche at Sukkertoppen on 19 December 2015 occurred in an area where the risk of such events was well known, and where the risk that a snow avalanche could impact houses at the foot of the mountain had been well described. The dissemination of this knowledge was performed through reports from the NGI [

11,

12], through theses at UNIS, and by staff members at UNIS. Nevertheless, the knowledge about the risk of snow avalanches at Sukkertoppen and their possible impacts has not had any influence on the local administration of Longyearbyen and seems to have been ‘lost’ in the changes in the administrative and management system in Longyearbyen [

18] and in the rather substantial turnover of administrative staff. Resources for protection were not available in the local administration, so snow avalanche protection did not have any high priority despite knowledge about the hazard.

UNIS has undertaken much field-based activity in academic subjects such as meteorology, glaciology, geomorphology, and Arctic technology related to the development of infrastructure [

30]. A formal system for informing local authorities about the risks discovered and about possible natural hazards was not established by the time of the 15 December 2015 snow avalanche, however. Whether to take such action has been up to the respective scientific staff members. Since 2017, an Arctic Safety Centre has been developed at UNIS (see

www.unis.no). Now the centre coordinates the local snow observation group, which provides weekly snow observations for the local avalanche warning system in Longyearbyen. The service is delivered to the Longyearbyen Community Council and is a key source of information for the avalanche warning system, which protects people and infrastructure in Longyearbyen. Through the role of the Arctic Safety Centre, there is now a much better system in place for knowledge transfer from UNIS to the local authorities in questions concerning safety in relation to the natural conditions that prevail in Svalbard, and especially in relation to the natural hazards. This is much along the lines proposed by [

31], who advise that UNIS be given a role as an independent management organisation directly under the Ministry of Education and Knowledge to better fulfil its role as a strategically important institution in Longyearbyen, Svalbard.

Soon after the 2015 catastrophe, the Ministry of Justice and Civil Preparedness decided that there would be a formal investigation into the snow avalanche at Sukkertoppen on 19 December 2015. The investigation was carried out by the Directorate for Safety of Society and Preparedness (DSP), and their report was released in September 2016 [

32]. The report gives an overview of the snow avalanche accident in Longyearbyen and suggests several learning points for national and local authorities and emergency and preparedness actors on how to clarify duties, responsibilities, and roles, and how to upgrade equipment and systems to ensure future preparedness and crisis management in Svalbard. In the DSP report [

32] (p. 49), the NGI’s and UNIS’s knowledge regarding avalanche dangers is referred to, and it is said that UNIS research has not been systematically disseminated to the authorities in Longyearbyen. With the establishment and the activity of the Arctic Safety Centre this is now taken care of.

Irrespective of this investigation, in June 2016, the District Attorney of the county of Troms decided [

33] that there were no juridical responsibilities related to the avalanche in Longyearbyen on 19 December 2015. Nevertheless, the family who lost their child in the catastrophe appealed this decision with the Attorney General of Norway [

34,

35], claiming that they had been unaware that their house, which had been allocated to them by their employer, was at risk from snow avalanche from Sukkertoppen. The Attorney General of Norway decided to reopen the case and refer it to the Special Unit for Police Issues. By November 2017, the case was closed again, with conclusion that none of the local authorities or the employer did anything illegal by not informing about the avalanche danger [

36]. Finally, in March 2019, the family was compensated with about NOK 2.3 mill. for the loss of their child through an agreement with the insurance company and the local administration of Longyearbyen.