Abstract

During January–February 2025, the Santorini volcanic complex experienced intense seismic activity, increasing interest and concern regarding the possible reactivation of the magmatic system. This study investigates the spatial and magnitude distribution of seismic events with the aim of distinguishing between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes and understanding the underlying processes governing seismicity in the region. The analysis is based on data from the national and local seismic network, including epicenter and focus determination, local magnitude (ML) calculation, depth analysis, statistical processing, and the application of machine learning methods for event classification. The results show that tectonic earthquakes are mainly located at depths, D > 8 km along active faults, while volcanic earthquakes are concentrated at shallower levels (D < 5 km) below the volcanic center. The analysis of b values suggests the differentiation of the focal mechanism, with higher values for volcanic events, which is related to fluid and magmatic pressure processes. The spatiotemporal evolution of seismicity demonstrates seismic swarm characteristics, without a main earthquake, which are attributed to processes within the subvolcanic system. The study contributes to improving the understanding of the current seismovolcanic crisis of Santorini and enhances the ability to identify magmatic instability processes in a timely manner, critical for hazard assessment and monitoring of the South Aegean volcanic arc.

1. Introduction

The Santorini volcanic complex is one of the most active volcanic centers of the Hellenic Volcanic Arc (Hellenic Arc), which extends from the Gulf of Corinth to Nisyros Island and is formed due to the subduction of the African lithospheric plate beneath the Aegean microplate [1,2]. This subduction system represents one of the most active geodynamic environments in the Eastern Mediterranean, governing both the seismicity and magmatic evolution of the region. The Hellenic Arc is characterized by intense crustal deformation, plate folding processes, retrograde arc extension, and intermediate-depth seismicity, factors which influence the tectonic and volcanic behavior of Santorini. Within this broader context, stress transfer related to subduction and arc-scale tectonic loading play a dominant role in shaping the distribution and characteristics of seismic activity in the central Aegean Sea [3]. Santorini is characterized by an intense extensional tectonic regime, with normal fault-oriented N-S and NE-SW, which control both seismicity and magmatic supply [4]. These structures reflect the effect of the extension of the retrograde arc associated with the retreat of the plate beneath the Hellenic Arc, which promotes the thinning of the crust and the creation of andesitic magma in the mantle wedge. Subduction occurs at a rate of ~3–5 cm/year and creates significant geodynamic processes, such as seismic activity along the Hellenic Arc, the uplift and melting of the mantle wedge, and ultimately the production of magma of andesitic to dacitic composition [5].

The island is a semicircular cluster around a caldera with a diameter of ~10 km. The caldera of Santorini was formed by a series of explosive eruptions, the most significant of which was the Minoan eruption (around 1600 BC), which had global climatic and cultural consequences [6]. Since then, activity has been limited mainly to the volcanic center of Nea and Paliá Kámenis, with submarine and subaerial explosions recorded during the 20th century (1925–1928, 1939–1941, 1950) [6].

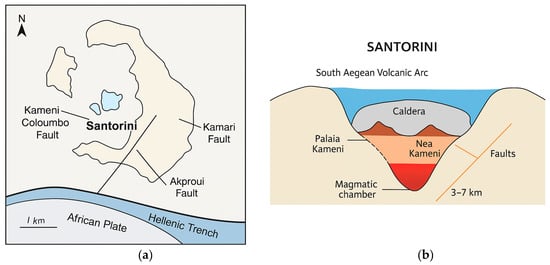

The area is characterized by a complex tectonic setting, with dominant extensional deformation in an E-W direction, characterized by normal faults with N-S and NE-SW strike. These faults act as magma ascending channels and influence the distribution of seismicity [4]. Geophysical studies revealed at least two magma stores that have been identified in the subvolcanic environment: a shallow one (~3–6 km) and a deeper one (~8–12 km). These stores feed volcanic episodes [7].

Seismic activity in the Santorini volcanic complex is generally characterized by low seismicity, as demonstrated by the long-term seismological and geodetic monitoring of the area. The volcanic system experiences recurring episodes of volcanic unrest, which mainly manifest as increased microseismicity (ML < 3.5), focused on shallow depths (D < 5 km). These events reflect dynamic fluid-magma interactions and pressure changes in the subvolcanic system. Volcanic seismicity in active caldera systems such as Santorini can be conceptually categorized into two main types. The first includes true volcanic earthquakes, which are related to volcanic activity, magma fracturing, or rapid compression of volcanic fluids, which typically produce low-frequency signals and occur at very shallow depths. The second category includes volcanic earthquakes triggered by magma or fluid intrusion, which are generated by magma migration, hydrothermal compression, or changes in the subvolcanic stress field, without necessarily indicating an imminent eruption. The seismic events associated with the 2025 crisis belong to this second category, reflecting a phase of magmatic and hydrothermal reactivation rather than immediate explosive processes. Despite their low magnitude, clusters and crises of increased seismic activity are observed at intervals, which are associated with magmatic feedback processes and possible changes in the pressure regime in the subvolcanic space. A typical example is the 2011–2012 crisis, which was accompanied by the recording of Nr > 1.500 microearthquakes and intense geodetic inflation of the caldera, with an estimated magma influx of 10–20 × 106 m3 [8,9]. At the same time, it was accompanied by a significant seismic swarm and intense geodetic inflation (>140 mm), indicating magma influx at a depth of 3 km < D < 6 km below the volcanic center. After the end of the seismic crisis, gradual deflation of the caldera was observed, indicating relaxation of the pressurized magmatic system [10,11].

In modern times, geodetic and seismological monitoring has revealed recurring periods of volcanic “unrest”, such as the 2011–2012 seismic crisis, which was accompanied by a significant seismic swarm [11] and intense geodetic swelling (>140 mm), indicating magma influx at a depth of 3–6 km below the volcanic center [8,9,10,11]. After the crisis, gradual caldera subsidence (deflation) was recorded, indicating the relaxation of the pressurized magmatic system [4,11].

In February 2025, a new series of microearthquakes was recorded within and around the Santorini caldera, with increased spatial density of epicenters compared to the usual microseismicity of the area. These events, although small in magnitude, exhibited temporal and spatial clustering, characteristic of seismic episodes associated with fluid or magma transport processes in the subvolcanic system. Such seismic clusters, particularly in volcanic environments, often indicate fluid migration or disturbances in the pressure regime of the magmatic system. The spatiotemporal distribution of seismic activity in 2025—including focal depth characteristics and statistical parameters—provides important qualitative information for distinguishing between tectonic earthquakes, which typically occur at greater depths along pre-existing faults, and volcanic earthquakes, which occur at shallow depths and are associated with magmatic or hydrothermal processes. Placing the seismic activity of 2025 in the broader geodynamic context of the Hellenic Arc allows for a more complete understanding of the interaction between regional subduction dynamics and the local fault system-magma system of Santorini. Recent studies emphasize the importance of arc-scale stress transfer in controlling the initiation of seismic clusters, shallow deformation, and the transition between tectonic and volcanic-tectonic processes in the central Aegean. In this context, the analysis of the February 2025 seismic sequence offers a valuable opportunity to investigate the current state of the Santorini magmatic system and assess potential implications for volcanic hazard assessment.

The geometry of seismicity, in combination with the depth distribution and other statistical parameters, are critical tools for distinguishing tectonic earthquakes (which typically occur at greater depths and along pre-existing faults) from volcanic earthquakes, which are associated with fluid pressure at shallow depths or magmatic migration [7]. The exact identification of these mechanisms is crucial for understanding the current phase of volcanic unrest and for assessing the possible risk of volcanic activity soon. In similar crises, such as that of 2011–2012, a comprehensive analysis of seismological, geodetic, and geochemical data showed clear signs of magma influx, providing early warning and enabling enhanced monitoring [8,9].

In this framework, this study focuses on the quantitative analysis of the recorded seismic events of February 2025, with the purpose of:

- Assessing the spatial and magnitude distribution of the events, ensuring the accurate representation of their spatial and magnitude distribution, and calculating statistical parameters;

- Separating tectonic and volcanic earthquakes based on criteria of depth, magnitude, focal mechanism, and temporal evolution;

- Correlating observations with existing models of the Santorini magmatic system to establish conclusions on the possible continuation or resolution of the current seismic crisis;

- Interpreting the findings in relation to the current state of the Santorini magmatic system and preparing early warning protocols.

2. Geodynamic Framework, Seismic Background & Classification for Seismic Events

2.1. Seismotectonic Status of Santorini

Santorini is in the central sector of the North Aegean Tectonic Arc (NAHT), which developed as a result of the subduction of the African lithospheric plate beneath the Eurasian plate along the Hellenic Trench. The continuous subduction at a rate of approximately 3–4 cm/year causes intense intermediate-depth seismicity, as well as the occurrence of magmatic systems along the arc. Santorini is the most active volcanic center in the central section, which hosts a magma chamber at depths of 3 < D < 7 km responsible for historical eruptions (e.g., Minoan Crete) beneath the caldera [6,7].

The seismotectonic status of the area (Figure 1) is dominated by a network of active faults, mainly normal and strike-slip faults, which are aligned in two main directions:

Figure 1.

(a): Geotectonic map of the Santorini caldera. The black lines indicate the main faults (Kameni–Columbo, Kamari, Akproui) and their tectonic relationship with the subduction of the African plate along the Greek Trench. (b): Schematic cross-section of the Santorini volcanic complex. The caldera, the volcanic islets of Palea and Nea Kameni, the main active faults, and the magma chamber at depths of 3–7 km are shown. The layout indicates the role of tectonic structures as possible channels for the ascent of magma and fluids from the subvolcanic chamber to the surface.

- NE-SW (Kameni and Columbo’s faults): Significant faults are in this direction, such as the Kameni and Columbo’s faults, which are mainly normal or oblique-horizontal in character. These faults are considered active and are related to the movement of tectonic blocks, causing moderate to strong seismic shocks.

- E-W (Akrotiri, Kamari faults) [11]: Faults with characteristics of transformation and strike-slip are observed in this direction, which are associated with the adjustment of the crust to larger-scale tectonic processes. These faults contribute to the redistribution of stresses in the crust and can cause earthquakes with a strong surface footprint.

These faults accommodate the majority of microseismicity and act as possible magma ascent conduits. Furthermore, seismicity is related to the periodic charging/discharging processes of the underlying magmatic system, with swarm characteristics indicating fluid movement and local stress changes. This situation makes Santorini a natural laboratory for studying the interaction of tectonic and magmatic processes, with direct applications in seismic and volcanic hazard assessment [12].

2.2. Temporal Evolution and Iteration of Seismic Crises in Santorini

Santorini has a long history of seismic and volcanic activity, reflecting the complex interaction between the magmatic system and the tectonic field of region [13]. The last magmatic eruption occurred in 1950 at Nea Kameni and was mainly excentrical in nature, with lava effusion, low-intensity explosive episodes, and accompanying hydrothermal activity [14]. Since then, activity has been limited to hydrothermal gas emissions and sporadic microseismicity.

Over the following decades, there have been observed events of volcanic “unease” with increased seismicity and geodetic displacements attributed to magma inflows into the subvolcanic chamber. The most characteristic sequence occurred in 2011–2012, when significant surface deformation (~8–14 cm) in the caldera area, as recorded by GNSS and InSAR measurements, combined with a notable increase in microseismicity [10,13].

Similar but smaller-scale events have been recorded in the past (e.g., 1925–1928, 1939–1941), with temporary seismicity enhancement, surface cracks, and gas emissions preceding or accompanying the development of volcanic islets [5,14]. These historical shocks underscore the cyclical nature of magmatic activity in Santorini, with long periods of relative calm interrupted by phases of intense magmatic reactivation and seismic excitation.

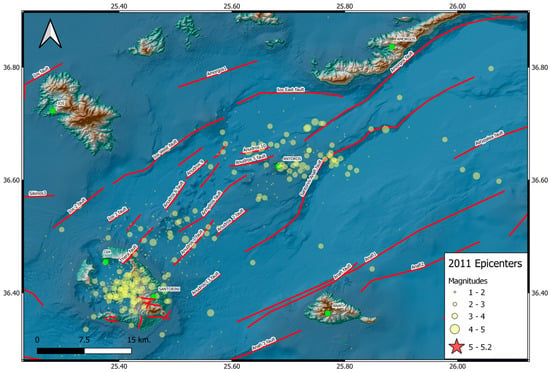

The crisis of January 2011–April 2012 is the most extensively recorded example of volcanic activity on Santorini in the 20th and 21st centuries. During this period, significant seismic activity was recorded, with more than 1.500 small events with magnitude, ML ≤ 3.2 (Figure 2) concentrated mainly in the central and southern parts of the caldera [9,14]. Most events were shallow (D < 5 km), suggesting the activation of tectonic faults that intersect the volcanic dome and possible movement of fluids or magma at the subvolcanic level. Figure 2 illustrates the seismicity associated with the 2011 unrest episode, which is used here as a historical benchmark due to its comprehensive documentation and its relevance as the most recent well-characterized period of volcanic unrest prior to 2024–2025. The recent 2024–2025 seismic sequence is not represented in this figure because it is presented in detail in later sections of the manuscript using high-resolution data sets and specialized figures.

Figure 2.

Seismic activity and fault distribution in the Santorini–Amorgos–Anafi region for the year 2011. Epicenters are represented by circles scaled to earthquake magnitude, while red lines indicate mapped faults for the study area [15]. The map highlights the correlation between seismicity and the main fault systems surrounding the Santorini volcanic complex and adjacent islands. Green squares denote the largest cities near the epicenter.

At the same time, geodetic observations indicated extensive surface deformation. Networks of permanent GNSS stations (e.g., NOA, AUTH) and differential InSAR analysis (Sentinel, Envisat) recorded horizontal movements of up to 140 mm and surface uplifts of up to 80–140 mm, with maximum values around Nea Kameni [10,13]. The spatial distribution of the deformation was interpreted using Mogi elastic models, which showed magma influx into a chamber located at a depth of ~4 km below northern Nea Kameni, with an estimated volume of 10–20 × 106 m3 [13]. The sequence was followed by an increase in CO2 and SO2 emissions at some hydrothermal sources, as well as changes in ground temperature, supporting the magmatic reactivation hypothesis [9]. However, activity declined gradually towards the end of 2012 without culminating in a volcanic eruption, suggesting that the magma influx either exhausted or stabilized within the chamber without breaching the system.

The 2011–2012 seismic crisis is a critical example of a warning episode that did not develop into an eruption. Comparing it with the February 2025 crisis can give us valuable info for spotting common patterns and improving volcanic hazard prediction models. Over the next decade (2013–2023), the study area experienced low levels of seismicity, with sporadic clusters of a small number of events attributed to local tectonic activity or minor magmatic processes without surface expression [7].

From the end of January 2025 to mid-February of the same year, Santorini, one of Greece’s most famous tourist destinations, was at the epicenter of a significant seismic crisis [16,17]. The seismic crisis in the first two months of 2025 was the most intense since 1964, causing serious concerns about the safety of the area [16]. This activity, which was characterized by thousands of small and medium-sized earthquakes, caused concern among both residents and visitors to the island. The connection between the volcanoes of Santorini and Columbo via an underwater magma intrusion highlights the need for ongoing monitoring and preparation for future geological events [18]. The seismic crisis was attributed to magma movement that caused a rupture in the middle crust, connecting the volcanoes of Santorini and the undersea Columbo. Analyses show that seismic activity was caused by the uplift of the Santorini caldera and the escape of gases such as carbon dioxide and hydrogen, indicating the influx of new magma into the surface reservoir.

The intensity and frequency of the earthquakes caused disruption to the population. Approximately 11,000 of the 15,000 local citizens temporarily left the island, seeking safety on neighboring islands or mainland Greece [19]. The Greek government declared a state of emergency on 6 February 2025, activating civil protection plans and real-time monitoring of the volcano [20]. The impact on tourism was immediate: the areas of Oia and Fira were almost completely deserted, resulting in serious economic damage to hotels, restaurants, and tourism-based businesses, even though it was outside the peak summer season [21].

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data Processing

Data processing is a very important step for a reliable analysis of seismic activity and for providing valid conclusions about the magmatic and tectonic status of Santorini [22]. This study used data from local and regional seismological stations, which were collected during February 2025. The data included high-resolution seismograms, which passed a preliminary quality control check to remove noise and record errors. Following this, procedures for event location and magnitude calculation (ML) were applied, while parameters such as frequency, amplitude, and duration of recordings (spectral analysis) were used to distinguish between tectonic and volcanic events [23].

To distinguish between tectonic and magmatic processes, we examined key observable parameters: (i) focal depth distribution, (ii) spatial clustering and fault-parallel alignment of epicenters, (iii) temporal evolution of the seismic sequence, (iv) magnitude–frequency relationships (b-values), and (v) waveform characteristics derived from spectral analysis and machine learning classification. These diagnostic parameters allow robust identification of shallow pressure-driven events versus deeper tectonic fault activation. To ensure the reliability of the classification, consistency in depth and size was checked. The identified VT events were associated with greater focal depths (D > 8–10 km), while volcanic events were concentrated at shallow levels (D < 5–7 km), according to the spatial distribution shown in Section 3.4.1. Also, the temporal clustering of swarm-type earthquakes without a dominant mainshock falls into the above category. In contrast, the activation of tectonic faults is supported by deeper events (D > 10–12 km), alignment of the epicenter with mapped fault systems, focal mechanism solutions indicating normal or laterally normal faults consistent, and high-frequency signatures characteristic of brittle failure.

The distinction between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes was based on established spectral and temporal criteria that have been widely documented in seismological studies of volcanic environments [24,25,26]. In addition, the events were also mapped spatially and in relation to depth to investigate possible spatiotemporal correlations with known tectonic structures and the subvolcanic magmatic system [27].

3.2. Seismological Analysis of the Seismic Sequence Between Santorini—Amorgos Islands, North Aegean Sea

Accurate estimation of the epicenter, focal depth, and focal mechanisms of an earthquake is a crucial step in understanding the activation of tectonic and/or volcanic structures in a region. Incorrect or unclear location can provide false conclusions about the activation of faults or changes in the magmatic system pressure [16]. More especially in volcanic environments, such as Santorini, detailed analysis of the focal mechanisms provides critical information on whether the events are derived from purely tectonic processes or from magmatic processes, such as magma migration or hydrothermal circulation [28,29].

It is essential for risk assessment to characterize a seismic sequence as either a swarm or a series of foreshocks that may precede a stronger mainshock [30]. Swarms are characterized by several small events without the occurrence of a main earthquake [30], whereas foreshocks in contrast usually have a temporal and spatial organization that terminates in a stronger event [31]. The analysis of spatiotemporal evolution, the focal mechanisms, and the frequency of seismic waves is a decisive tool for distinguishing between the two phenomena [21].

In the case of the seismic sequence in Santorini in 2025, the analysis of the data indicated swarm characteristics, with several small to intermediate magnitude microearthquakes distributed around the caldera and at depths consistent with the magmatic system [22]. The absence of a stronger main earthquake and the presence of events with volcanic characteristics enhance the interpretation that the sequence is related to magmatic processes rather than classical tectonic activation [31]. This highlights the need for continuous observation with optimized seismological station networks to ensure a timely and accurate understanding of the evolution of such crises, with direct applications in risk assessment and protective measures [22].

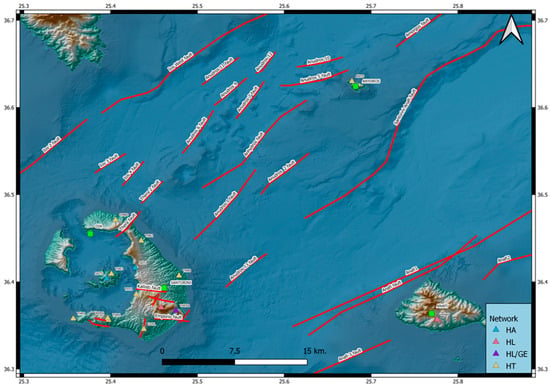

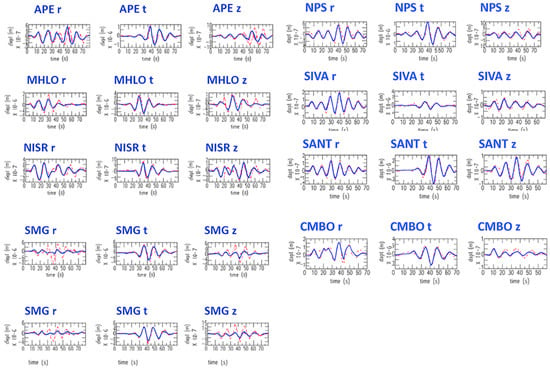

For this seismic analysis, seismic data from HUSN (Figure 3), a network of high-sensitivity seismic stations, was evaluated, which provided reliable and high-resolution recordings of seismic waves. This ensured the necessary spatial and temporal coverage of the data (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Station distribution for the HUSN for the studied region, Santorini–Amorgos–Anafi. Red lines correspond to the main active faults for the study area [32]. Copernicus Land Monitoring Service used for DEM [15]. Blue triangles represent the seismological stations belonging to the National Kapodistrian of Athens Seismological Network [33], red triangles represent the seismological stations belonging to the National Observatory of Athens—Institute of Geodynamics [34], purple triangles correspond the common seismological stations of National Observatory of Athens (Institute of Geodynamics and Geofon) and finally yellow triangles correspond to the seismological stations belonging to the AUTH Seismological Network [35]. Green squares denote the largest cities in the study area.

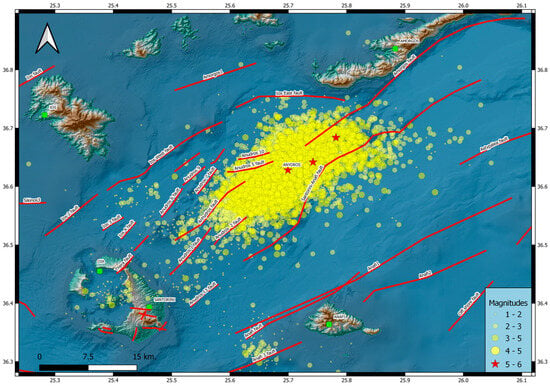

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution of earthquake epicenters in the Santorini–Amorgos region. The map shows seismic activity recorded during the analyzed period, with epicenters color-coded and scaled according to magnitude. Red lines represent major active faults [32]. The concentration of seismicity between Amorgos and Santorini indicates intense fault activity along the Santorini–Amorgos fault zone, including events up to magnitude ML = 6.0 (red stars). The strongest events (are marked with red stars) are concentrated mainly along the Santorini–Anydros fault, reflecting the close interaction between tectonic stress and volcanic activity. The region is part of the Greek arc, where the subduction of the African plate under the Eurasian plate controls the evolution of both seismicity and magmatic activity.

These data were used to accurately determine the focal parameters of the seismic events, including the location of the epicenters, the time of occurrence, and the estimated magnitude. Emphasis was focused on the spatial relationship of the epicenters with the active faults represented on the map, to study the correlation between seismicity and tectonic structures. Analysis of the recordings enabled the epicenters to be in relation to the active faults in the area, as shown on the map, confirming the close correlation between seismic activity and tectonic structures. The use of a significant number of seismological stations enabled a more accurate determination of both the epicenters and the focal parameters and reduced uncertainty, which is critical for the reliability of the conclusions. The results demonstrate the importance of systematic seismological observation for understanding seismicity and investigating its relationship with active faults, providing critical data for future risk and disaster management studies.

During the period 26 January 2025 to 22 February 2025, more than 10.000 events were recorded, ranging in magnitude from 1.0 to 5.3 on the Richter scale. The epicenters were located at depths of 4–16 km, mainly in the sea area between Santorini, Amorgos, Ios, and Anydros Islands. The strongest earthquake occurred on 22 February, with a magnitude ML = 5.3, causing intense concern about a possible continuation or escalation of the activity.

Earthquakes that occurred in the North Aegean region between Santorini and Anydros Island, are shown in Figure 4.

The largest events in the swarm are marked with red stars; green squares represent islands near the epicenter. Red lines represent the main faults for the study area as originated from [15,32], available at https://land.copernicus.eu/imagery-in-situ/eu-dem (accessed on 6 December 2025). Bathymetry was obtained using Emodnet Bathymetry [15] and DEM. The distribution of the epicenters for the seismic swarm January–February 2025 also appears on the map with yellow circles. The size of the circles indicates the magnitude of seismic events. The larger circle indicates higher magnitudes.

A few days after the beginning of the swarm, a network of portable seismographs was installed in the area. The installation and use of this network proved particularly useful and constructive for the analysis of this swarm, for several reasons. First, the portable network allows for more complete coverage of areas near the epicenter, where permanent stations cannot provide sufficient spatial resolution or fully record strong accelerations due to instrument saturation. This is critical, especially in the early stages of a seismic sequence, where the dynamics of seismicity and fault activation proceed at a rapid speed. Additionally, the use of the portable network enabled the observation of high-quality data from small and medium earthquakes that are often missed by permanent stations, enhancing the ability to map epicenters and determine focal parameters with greater accuracy. The close spatial distribution of the portable stations also allows the spatial distribution of seismicity to be identified and studied on a smaller scale, revealing the activation of smaller branches or secondary faults that may not be detected by the national network. Finally, the data from the portable network contributed to the validation of the permanent station recordings and the estimation of the uncertainty of the earthquake parameters. The availability of multiple, independent observations of the same events allowed the application of cross-checking and statistical analysis methods, enhancing the reliability of conclusions regarding the progress of the sequence, the intensity of the earthquakes, and their relationship to the active faults in the area. Overall, the portable network provided a valuable tool for understanding seismic dynamics and for real-time analytical monitoring of the seismic sequence.

For the purposes of this study, a combined dataset was used that includes broad-band 3-component seismological stations, accelerographs from the national seismograph network (NOA and AUTH), as well as data from the portable seismograph network. The seismological stations provided reliable recordings of low and medium frequencies, while the accelerographs, from the national network, recorded high frequencies and strong accelerations, thus fully covering the spectrum of seismic intensities and areas. The technical characteristics of the instruments, such as frequency range, sensitivity, dynamic range, and sampling parameters, are presented in detail in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of seismological stations in the study area. Station coordinates are in decimal degrees, and elevation is in m. Sources: [33,34,35].

Summary, more than 40.000 seismic event waveforms were analyzed. Waveform processing included high-order Butterworth filtering to cut off noise outside the band of interest, base corrections, and Fourier and wavelet transforms to determine spectral energy in different frequency bands. Fourier and wavelet transforms were used to determine spectral energy in different frequency bands. These recordings were used to accurately determine the focal parameters of the seismic events, including the geographical location of the epicenter, the focal depth, and the time of occurrence. The combined use of both seismological stations, and the portable network allowed for the validation of results, reduction of uncertainty, and accurate mapping of seismic activity in relation to active faults in the region. In addition, the mobile network provided high-resolution data from the early stages of the sequence, which is critical for understanding the dynamic evolution of the seismic sequence and the activation of faults.

3.3. Moment Tensor Solutions (MT’s)

The calculation of seismic parameters and the determination of the focal mechanism are essential tools for understanding the processes that govern a seismic swarm. The estimation of parameters such as seismic moment, combined with the analysis of rupture mechanisms, allows the distinction between tectonic activity, processes related to the circulation of fluids or magmatic movements, as well as the understanding of the evolution of seismic energy over time. In the case of the cluster that occurred in Santorini in February 2025, this analysis was crucial, as the activity was characterized by a multitude of microearthquakes and the absence of a dominant main earthquake. The investigation of focal mechanisms allowed the connection of events with active tectonic faults in the area and the distinction of the seismicity associated with tectonic deformation from that influenced by the presence of the Columbo volcanic system. The systematic monitoring of the parameters over time made it possible to understand the evolution of the sequence, while at the same time contributing to the improvement of the assessment of seismic hazard for the broader Cyclades region.

In this section, the seismic parameters for the largest earthquakes in the cluster, specifically those with a magnitude equal to or greater than ML = 4.0, will be calculated. The selection of this category of events is since the largest earthquakes provide higher quality recordings and signals with a better signal-to-noise ratio, which allows for a more reliable estimation of the source parameters [36]. The calculation of these parameters is considered necessary to investigate the nature of seismic activity and to clarify whether the events are related to purely tectonic processes or if they are associated with volcanic processes, such as magmatic intrusion or fluid movement [37]. This distinction is achieved through the analysis of focal mechanisms, which capture the kinematics of the faults that are activated. Mechanisms characterized by horizontal slip or normal rupture are usually associated with tectonic deformation, while mechanisms with significant extensional or uplift components indicate processes that are related to volcanic activity. To calculate the rupture mechanisms, Ammon’s software method [38], which is based on waveform inversion and provides reliable moment solutions for medium and large-sized events, was applied. In this way, it became possible to correlate seismic activity with the underlying geodynamic processes, contributing to the understanding of the evolution of the cluster in space and time.

For a given velocity structure, this method calculates synthetic seismograms, which are then directly compared with the real seismograms. The process is based on the calculation of Green’s Functions, which describe the Earth’s response to an ideal point source and are the cornerstone for the creation of synthetic waveforms. Green’s Functions incorporate the effect of the velocity structure [36], (stratification, elastic properties, absorption) on the propagation of seismic waves and make it possible to simulate how a real seismic event would be recorded at a station. For their calculation, the reflectivity method of Kennett [39] was used, which allows for the accurate estimation of the propagation of seismic waves in layered media, considering reflections and refractions at all boundaries between layers. The application of the methodology follows the approach of Randall [40], who developed computational techniques for the practical generation of Green’s Functions in seismological applications.

In the present study, the three-dimensional velocity model of Papazachos [41] for the Greek area was used, which provides a realistic approximation of the velocity distribution in the region. This model was combined with synthetic seismic models representing the three fundamental forms of deformation (normal, reverse and horizontal slip), allowing the reliable calculation of synthetic seismograms. The comparison of the synthetics with the real data allowed the inversion of the waveforms and the estimation of the focal mechanisms for the largest earthquakes of the cluster.

This sequence has a scientific interest, as the area is part of the active volcanic arc of the South Aegean, where seismicity is directly linked to the dynamic interaction of tectonic and volcanic processes. The earthquake of 10 February 2025 was the strongest event to date and enabled a detailed analysis of the spatiotemporal distribution of the seismic epicenters, the mechanistic solution of the earthquake and the energy released.

The Mw = 5.4, 10 February 2025 Earthquake

On 10 February 2025, a seismic event of moment magnitude Mw ≈ 5.4 was recorded, which is part of the seismic swarm that was active in the broader area between Santorini, Anydros Island in the first weeks of the year. The earthquake of 10 February 2025 is considered one of the strongest in the sequence, and its occurrence intensified concerns about possible changes in the geodynamic state of the region. Research approaches based on analyses of seismic “regularity” and the release of rupture energy show that larger events are accompanied by characteristic transitions in the structure of seismic disturbances.

In this study, the Mw = 5.4 earthquake of 10 February 2025, between Santorini and Anydros Island, North Aegean Sea, Greece, examined in detail using the procedure described in Section 3.3. Seismic parameters are calculated, to evaluate the seismotectonic significance of the event in the broader area of Santorini. The source parameters (φ, δ, λ), the Moment Magnitude (Mw), the Seismic Moment (M0) and the Depth (d) were estimated. For this purpose, data from ten broadband stations with three components were used, each at epicentral distances less than 250 km. The inversion indicates the activation of a normal type of fault. The optimal solution was strike = 260°, dip = 55°, rake = −86° and the focal depth was calculated to be 9 km. The focal solution, with a focal depth of approximately 9 km, indicates that the event occurred within the upper crustal section, within the zone of active extensional deformation characterizing the volcanic arc of the South Aegean. The seismic moment was determined as M0 = 1.4 × 1026 dyn × cm, and the calculated double couple (DC) was found to be equal to 55%, while the compensated linear vector dipole (CLVD) was 45%. Of particular interest is the relatively high CLVD ratio (45%) compared to the double pair (DC = 55%), which may indicate a departure from purely elastic fracture. This can be interpreted either as an indication of the complex geometry of the rupture surface, or as a result of combined tectonic and magmatic processes, especially considering the proximity of the epicenter to the Colombo volcanic field. These geometric characteristics of the fault plane are in accordance with the seismotectonic environment of the region. Figure 5 shows the procedural outcomes.

Figure 5.

Moment tensor solution of the 10 February 2025 (22:34 UTC) earthquake. The center portion displays a summary of the answers together with the accompanying beach ball. At the inverted stations for the radial, tangential, and vertical components. The observed and synthetic displacement waveforms are shown on the left as continuous and dotted lines, respectively. Blue continuous lines denote the observed displacement waveforms, while red dotted lines indicate the synthetic waveforms.

The following table (Table 2), available at [42], presents solutions from various agencies for the Santorini earthquake on 10 February 2025.

Table 2.

List of moment tensor solutions published by various institutions and universities on 10 February 2025 (22:37:26.21, UTC). Source: CSEM-EMSC. Available at https://www.emsc-csem.org/Earthquake_data/tensors.php (accessed on 29 October 2025) [42].

Overall, the inversion results confirm that the 10 February 2025 earthquake (Mw = 5.4) is associated with the activation of an E-W trending extensional fault, compatible with the general tectonic structure of the region. The presence of a significant non-dual component pair (CLVD) suggests possible mechanical or rheological inhomogeneity of the fault, or a component of a non-purely tectonic nature, which deserves further investigation through comprehensive seismological and geophysical analysis. Figure 5 shows the procedural outcomes.

3.4. Analysis of Seismicity in Santorini–Amorgos Islands During the Period December 2024–February 2025

This section examines the seismic activity that occurred in the wider area of Santorini and Amorgos during the period December 2024–February 2025. Within this period, intense and ongoing swarm seismic activity was observed [18]. The area is part of the South Aegean volcanic arc, where active tectonic structures and magmatic systems meet, resulting in complex geodynamic processes [43,44]. The analysis of seismicity in the area contributes significantly to understanding how tectonic and volcanic mechanisms interact, as well as to assessing volcanic risk [44,45].

First, the criteria for distinguishing between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes are presented (Section 3.4.1), [45], followed by statistical analysis and classification of events based on their magnitude and depth (Section 3.4.2), while Section 3.4.3 examines in detail the spatial and temporal evolution of the epicenters. The combined consideration of this data leads to the interpretation of the 2025 seismic excitation as a phreatotectonic swarm, which is most likely due to a temporary increase in pressure caused by fluid intrusion or small-scale magmatic activity [44].

3.4.1. Classification Criteria for Tectonic and Volcanic Earthquakes

Earthquakes are categorized into two main categories, depending on their focal mechanism, tectonic and volcanic [46]. The distinction between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes is crucial for the study of areas with intense geodynamic activity, such as the volcanic arc of the South Aegean Sea, and particularly Santorini, where active faults and magmatic systems coexist. In this region, earthquakes result either from the accumulation of energy along faults in the submarine and terrestrial crust (tectonic earthquakes) or from the movement of magma and pressure changes in the volcanic system (volcanic earthquakes) [47]. Tectonic earthquakes are the most common form of seismic activity and are related to the rupture of rocks along active faults due to the accumulation and sudden release of elastic energy in the lithosphere [47]. In contrast, volcanic earthquakes are associated with magmatic or hydrothermal activity in active volcanic systems and are caused by the movement of fluids, such as magma, gases, or hot liquids, within the crust [46].

From a seismological point of view, the two types of earthquakes show clear differences in their morphological and spectral characteristics. Tectonic earthquakes are characterized by high-frequency seismic waves and short duration, with a clearly defined rupture point [40]. Volcanic earthquakes, on the other hand, exhibit prolonged low-frequency waves (long-period events), which are attributed to fluid flow and the complex geometry of their sources. In addition, volcanic earthquakes occur at shallower depths (usually <10 km), while tectonic earthquakes can reach depths of up to 20–30 km, representing deeper structures of the lithosphere [48].

In terms of magnitude and energy output, tectonic earthquakes are generally stronger, often exceeding magnitudes of ML = 7.0, as they are associated with large fault zones. Volcanic earthquakes, on the other hand, have lower magnitudes (usually ML < 5.0), but can occur in the form of seismic swarms, with dozens or hundreds of small events within a short period of time. The occurrence of such swarms is usually associated with the movement or accumulation of magma and is an important indicator for monitoring possible volcanic processes [48].

Understanding the differences between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes is essential for interpreting data on seismic activity in the Offshore region between Santorini and Amorgos Islands. This region, where active faults and magmatic processes coexist, exhibits complex seismotectonic behavior, with events that can be attributed to both faulting mechanisms and fluid movements in the subvolcanic system [44]. In this context, the analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of seismic events during the period December 2024 to February 2025 allows the identification of the dominant processes that were at work, as well as the investigation of the possible transition from purely tectonic to seismotectonic activity.

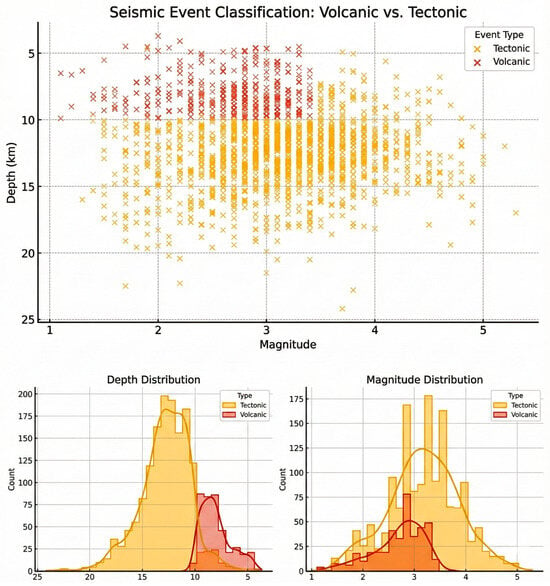

By applying machine learning methods for the period February 2025, the classification of seismic events based on depth and magnitude allows the two types of seismicity to be distinguished, revealing their different mechanisms. The attendance of shallow volcanic and deeper tectonic events, as shown in the diagram, enhances the suggestion of a transitional phase from purely tectonic to seismotectonic activity, in line with the analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of earthquakes from December 2024 to February 2025. The figure below (Figure 6) indicates the results of classifying seismic events into two categories—volcanic and tectonic. The data refers to the period of the ending December 2024 until February 2025 and include observations of the magnitude and depth of seismic vibrations.

Figure 6.

Classification of seismic events using machine learning methods for the period February 2025 in the Offshore region Santorini–Amorgos. The diagram shows the difference between volcanic and tectonic earthquakes in terms of depth and magnitude, highlighting the coexistence of magmatic and rift processes that characterize the seismotectonic evolution of the region. The figure corresponds to material previously posted on the author’s personal LinkedIn profile [49] (February 2025).

Uncertainties and possible errors in the dataset were methodically evaluated to assure the accuracy of the statistical results. The frequency-magnitude and depth distributions were constructed with the locating agencies’ magnitude and depth uncertainties in mind. In addition, catalogue completeness was evaluated using typical completion magnitude (Mc) estimation to remove influence from missing low-magnitude occurrences. Potential network-related biases were addressed by merging data from both permanent and temporary stations, which significantly improved spatial coverage and reduced preferential detection effects. To assess potential misclassification and guarantee strong separation between tectonic and volcanic events, the classification findings obtained from machine learning techniques were cross validated with waveform features.

The first graph (top) indicates the relationship between depth and size. Different colors denote tectonic and volcanic events. The yellow dots correspond to tectonic events, while the red dots correspond to volcanic events. Tectonic events tend to occur at greater depths (approximately 10–20 km), while volcanic events are concentrated in shallower areas (5–10 km). However, both categories have similar magnitude ranges, with most events having a magnitude between 2 and 4 on the Richter scale. However, both categories have similar magnitude ranges, with most events having a magnitude between 2 and 4 on the Richter scale. In the lower left graph, the depth distribution confirms the above observations: tectonic events show a strong peak around 15 km, while volcanic events are concentrated mainly at 8–10 km, reflecting their physical origin—tectonic events are associated with deeper faults in the crust, while volcanic events are associated with magma movements closer to the surface. In the lower right graph, the size distribution shows that both categories have similar statistical characteristics, with slightly higher average values for volcanic events. Overall, the results indicate that the machine learning model was able to satisfactorily separate the two categories based on depth and size, revealing clear physiological differences between volcanic and tectonic seismicity in February 2025.

3.4.2. Statistical Analysis of Seismic Events

Statistical analysis of seismic events is a critical step in studying the seismicity of an area, as it allows for the quantitative recording and interpretation of the physical processes associated with the focal mechanisms of earthquakes [22]. By analyzing parameters such as magnitude, depth, frequency of occurrence, and spatial distribution of seismic events, it is possible to identify patterns that reveal the nature of the mechanisms at work in the subsurface. Particularly in areas where tectonic faults and volcanic processes coexist [47], statistical data processing takes on dual significance: on the one hand, for understanding purely tectonic events and, on the other, for detecting possible signs of magmatic activity. The importance of statistical data is not limited to scientific research but also extends to crisis management and strategic security policy planning. Through systematically recording and analyzing historical and recent data, scientists can develop reliable prediction models and more accurately estimate potential future developments.

Santorini is one of the most active volcanic areas in the Aegean Sea, where tectonic deformation and magmatic activity coexist in close interaction. The volcanic arc of the South Aegean, to which it belongs, is formed by the convergence of the African and Eurasian lithospheric plates, creating an environment where seismicity reflects both rift movements and magma mobility in the lower crust. In this context, statistical analysis of earthquakes allows the mapping of active zones and the identification of spatial or temporal variations that may be related to the reactivation of the volcanic system.

Statistical data provide valuable knowledge regarding the frequency, intensity, and distribution of eruptions, while also enabling risk assessment and the implementation of preventive measures to protect residents and visitors to the island. Furthermore, the presentation of data using statistical indicators improves the communication of scientific findings to the public and decision-makers, making statistical data an indispensable tool in the study and monitoring of the Santorini seismic cluster. By comparing statistical patterns from different time periods, it can be determined whether the activity is shifting from purely tectonic to seismotectonic or volcanic, as observed in the period December 2024–February 2025. The statistical approach, therefore, is not merely a descriptive method, but a tool for interpretation and prediction, enhancing the overall understanding of the dynamic equilibrium of the Santorini volcanic complex.

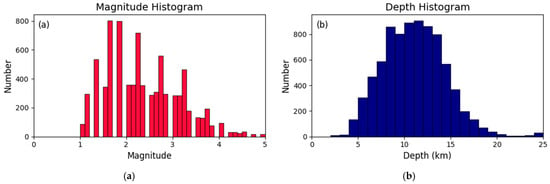

In this study, a big set of seismic data was used to draw reliable conclusions about the rate of change in seismicity in the Santorini area. The systematic recording and analysis of this data allows for an understanding of the tectonic processes affecting the region and provides a clear picture of the frequency and intensity of earthquakes over time. The compilation of this information into a single set allows the creation of graphs and visualizations that highlight patterns of seismic activity, thus contributing to the prediction of possible future events and the management of potential risks. Figure 7 represents the statistical characteristics of seismic activity recorded in Santorini during the recent seismic swarm. Diagram (a), shows the histogram of magnitudes, where most of the events are concentrated in the range 1.5 < ML< 3.0 degrees, while events with a magnitude greater than 4.0 are relatively limited. This distribution indicates intense microseismic activity, which is consistent with magmatic or hydrothermal stimulation phenomena, without, however, recording strong earthquakes that would indicate large-scale fault rupture. Diagram (b) indicates the distribution of focal depths of the events, which shows maximum distribution between 7 and 13 km. This range probably corresponds to the upper part of the magmatic system or to the activation of pre-existing fault zones related to magmatic pressure. The combination of shallow seismic activity and low magnitudes supports the interpretation of a process of mild magmatic unrest in the Santorini volcanic complex, with no evidence of imminent major volcanic eruption.

Figure 7.

Histograms of magnitude (a) and depth (b) of seismic events in the Santorini area. Most earthquakes have a magnitude 1.0 < ML < 3.0 and a depth of 8.0 < D < 15.0 km, reflecting the action of shallow faults and possible magmatic mobility in the upper part of the crust. These distributions support the conclusions of the statistical analysis regarding the dominant shallow seismicity and its connection to the Santorini volcanic system.

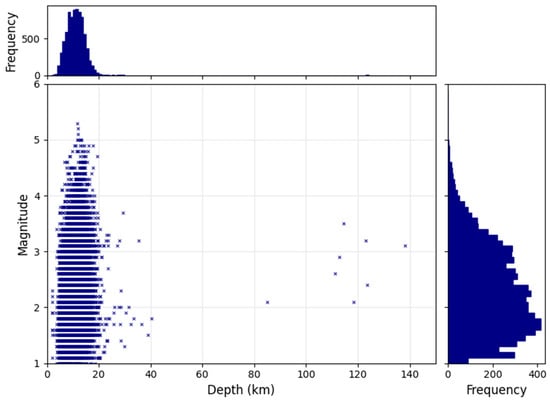

Figure 8 shows the correlation between focal depth and magnitude of seismic events recorded in Santorini, accompanied by the corresponding distribution histograms for each parameter. It is observed that most events are concentrated at shallow depths, between 5 km < D < 20 km, which suggests that the seismicity originates mainly from the upper parts of the crust, close to the magma reservoir of the volcanic system. Accordingly, the magnitudes range mainly between 1.0 and 3.5, with a limited number of events exceeding magnitude 4.0. This distribution indicates intense microseismic activity, which is consistent with processes caused by fluid movement or pressure changes within the volcanic system. The presence of isolated deeper events (D > 40 km), although rare, may indicate activation of deeper fault zones or energy escape to greater depths, without however documenting systematic seismicity at the lower crustal or upper mantle level. Overall, the spatial and statistical distribution of the data at Santorini reflects a state of mild magmatic or hydrothermal excitation, with no clear indication of evolution towards intense volcanic activity. Nevertheless, the persistence of microseismic activity at shallow depths is an indicator that requires continuous monitoring, as it may herald changes in the dynamics of the system.

Figure 8.

Correlation between magnitude and focal depth for the seismic sequence of Santorini. The central scatter plot shows individual seismic events, while the marginal histograms represent the frequency distributions of depth (top) and magnitude (right). Most events are concentrated between 5 < D < 20 km depth with magnitudes of 1.0 < ML < 3.5, indicating shallow microseismic activity related to magmatic and hydrothermal processes within the Santorini volcanic system.

3.4.3. Spatial-Temporal Evolution of Seismicity and Classification of Seismic Events

The analysis of the spatiotemporal evolution of seismicity in Santorini (Figure 9) offers crucial information for the investigation of the processes taking place in its active volcanic system. The distribution of seismic events both in space and time reveals the presence of zones of concentrated deformation, which are associated with the active faults of the island complex and the boundaries of the caldera edifice. The spatial concentrations of seismicity along the Columbo-Kamari faults and the southwestern periphery of the caldera indicate the close relationship of seismic activity with the structure of the volcanic field and the presence of magmatic or hydrothermal flows at shallow depths.

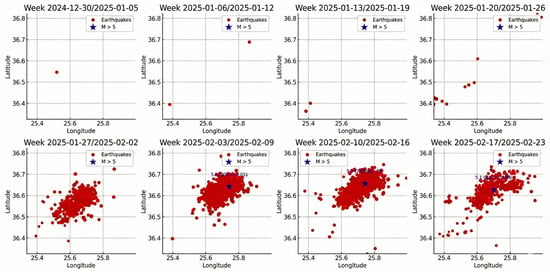

Figure 9.

Spatial and temporal distribution of seismic activity in the sea area between Santorini and Amorgos from late December 2024 to late February 2025. Each graph corresponds to one week of recordings. The red dots represent the epicenters of earthquakes, while the blue stars indicate events with a magnitude of M ≥ 5. The gradual concentration and subsequent dispersion of seismicity during the main phase of seismic excitation can be seen. The figure corresponds to material previously posted on the author’s personal LinkedIn profile [50] (February 2025).

The temporal evolution of seismicity shows characteristics of seismic swarms, with successive episodes of microearthquakes occurring in short time intervals, lasting from a few hours to a few days. These swarms do not follow the typical main earthquake-aftershock sequence, which suggests non-tectonic processes. The periodic occurrence of such episodes is interpreted as a result of pressure changes in the magmatic or hydrothermal system, possibly associated with fluid migration or the entry of new magma into the upper crustal part below Nea Kameni.

In terms of depth, most seismic events are located at shallow levels, between 5 and 20 km, which correspond to the crustal brittle zone above the main magma chamber. Individual deeper events up to about 40 km are also detected, which are probably associated with stress transport or with crystallization and gas expansion processes in the lower magmatic parts. The spatiotemporal migration of the epicenters during some episodes is an indication of temporary pressure or liquefaction within conduits and cracks communicating with the magma chamber.

The classification of seismic events, based on the characteristics of their waveforms, confirms the existence of different focal mechanisms. Most earthquakes belong to the volcano-tectonic (VT) type, with clear, high-frequency signals and abrupt arrivals of P waves, indicative of brittle faulting. At the same time, long-period (LP) earthquakes and hybrid events, characterized by lower frequencies and more gradual arrivals, phenomena related to fluid flow or pressure in magmatic-hydrothermal conduits, are recorded. The simultaneous presence of the two types of events (VT and LP) reveals the combined action of mechanical and fluid-dynamic processes, characteristic of magmatic feedback that precedes or accompanies phases of volcanic unrest.

Overall, the spatiotemporal evolution and morphological classification of seismicity in Santorini indicate an active, but relatively stable, system, in which seismic activity is mainly controlled by magmatic and hydrothermal processes at shallow depths. Continuous monitoring of the distribution and type of seismic events is a key tool for the early detection of possible changes in the volcanic regime and the assessment of volcanic risk in Santorini.

For the purposes of this study, the dynamic evolution of seismic activity in the volcanic and tectonic complex of Santorini–Amorgos Island complex on a weekly basis during the period from late December 2024 to late February 2025. The analysis aims to understand the spatial and temporal evolution of the seismic cluster, as well as to evaluate possible mechanisms that led to the activation of the fault system in the area. Recording the weekly distribution of epicenters allows for the detection of progressive changes in the stress field, providing valuable information on the seismotectonic behavior of the system.

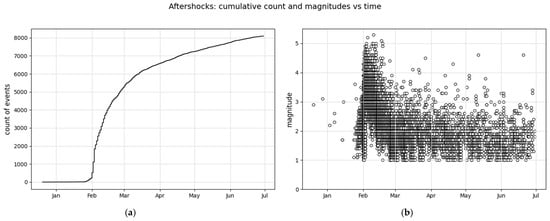

Figure 10 presents the temporal evolution of seismic activity associated with the Santorini earthquake sequence, depicting on the one hand the cumulative number of events (left diagram) and on the other hand the change in their magnitudes over time (right diagram). The cumulative distribution curve shows a strong and sharp increase in the number of events in early February, which indicates the sudden onset of a strong episode of microseismic excitation. This period corresponds to the main stage of activation of the volcanic system, during which most of the earthquakes of the sequence were recorded. Subsequently, the rate of accumulation of events decreases progressively, following a characteristic exponential decreasing course, as predicted by Omori’s law for post-seismic sequences. This decrease reflects the gradual release of stresses and the attenuation of the processes that caused the initial seismic outburst.

Figure 10.

Temporal evolution of the Santorini seismic swarm. (a) Cumulative number of seismic events versus time. (b) Magnitude variation over the same period. A pronounced increase in seismic activity is observed in early February, marking the main phase of the swarm, followed by a gradual decrease in the event rate and a transition toward a quiescent state. The magnitude distribution indicates an initial phase of larger events evolving into predominant microseismicity, typical of aftershock or magma-driven sequences.

The distribution of magnitudes in the right-hand diagram reflects the intensity and duration of the phenomenon. The largest magnitudes (up to ~5.0) are observed in the initial phase of the sequence, indicating the abrupt release of energy from the activation of faults associated with the Santorini volcanic complex. After this first stage, the magnitudes gradually decrease, with the activity being dominated by microearthquakes of magnitude 1.0 < ML < 3.0. This indicates the transition from a phase of intense mechanical instability to a period of gradual adjustment of the system. The maintenance of low but stable seismicity over the following months is probably related to the remaining movement of fluids or gases in the magma conduits, as well as to the equalization of pressures in the crustal part below Nea Kameni.

Overall, the data indicates that the Santorini earthquake series was the product of combined tectonic and magmatic processes, with a main phase of intense activity at the beginning of the year and gradual attenuation thereafter. The evolution of this sequence reveals a volcanic system in a state of mild excitation, where microseismic activity functions as a mechanism for releasing energy and pressure. Monitoring the rate and intensity of these events is essential for assessing the volcanic hazard and understanding the internal dynamics of the Santorini volcanic complex.

3.4.4. Machine Learning-Assisted Classification of Tectonic and Volcanic Events

A machine learning (ML) approach was used to investigate whether the recorded earthquakes formed discernible clusters corresponding to tectonic and volcanic origins to supplement the seismological and spatiotemporal analysis. The study’s main goal was to determine whether data-driven clustering patterns aligned with the accepted physical parameters governing seismicity in the Santorini volcanic system, rather than to create a stand-alone predictive classifier. Because of this, the ML component was created as an exploratory tool to aid in the interpretation of the seismic sequence, with the primary analysis of the study depending on the temporal migration, depth evolution, and spatial distribution of events.

A rule-based pre-classification applied to a subset of earthquakes was used to create the training dataset for the machine learning model. Well-established seismotectonic criteria, such as focal depth thresholds, magnitude characteristics, waveform morphology reported in the literature, and the known behavior of volcano-tectonic swarms in Santorini, served as the foundation for this initial classification. Volcanic events were defined as those that happened at shallow depths (less than 10 km), within clusters with swarm-like temporal patterns, and connected to the volcanic center. On the other hand, deeper events (>10–12 km) that were in line with significant fault structures and showed signs of tectonic deformation were classified as tectonic. A supervised model that used depth and magnitude as its main input features used these labeled data as its training set.

Internal consistency tests were used to validate the model by contrasting the ML classification results with the original rule-based labels. Additional qualitative validation involved comparing the ML results with independent observational indicators, including the spatial clustering of epicenters, the depth distribution observed across the sequence, and the temporal evolution of seismicity. This cross-check ensured that the ML-derived patterns were physically meaningful and aligned with the geological processes inferred from the detailed spatiotemporal analysis—our primary methodological focus. As a result, the ML approach served as an additional analytical layer that supported the seismological interpretation of the February 2025 Santorini seismic activity’s tectonic versus volcanic origins rather than taking its place.

4. Discussion

Recent interpretations of the 2025 Santorini seismic crisis reveal two complementary scientific perspectives that provide valuable insights into the origin and evolution of the observed seismicity. These views, proposed by refs. [51,52], highlight the interaction between magmatic processes and regional tectonic deformation, underscoring the complexity of seismo-volcanic interactions in the Santorini–Columbo’s volcanic field.

From a geodetic viewpoint, ref. [51] analyzes updated GNSS time series from permanent monitoring stations across the Santorini volcanic complex. The results show a measurable uplift of the caldera during the early phase of the 2025 crisis, with deformation patterns suggesting shallow magmatic compression beneath Nea Kameni. This uplift is consistent with magma injection or the accumulation of pressurized volcanic fluids within the upper crustal reservoirs, mirroring the deformation signatures observed during the 2011–2012 disturbance episode. In this context, the seismic cluster represents the mechanical response of the crust to an evolving magmatic intrusion, placing the magmatic system as a crucial factor in terms of 2025 activity.

In contrast, ref. [52] presents a mainly seismotectonic interpretation, suggesting that the 2025 sequence may have been significantly influenced by the regional redistribution of stresses along the Hellenic Arc. He argues that swarm-like behavior, the activation of fault segments and the temporal clustering of events may reflect a broader tectonic adjustment rather than a purely magmatic phenomenon. According to this view, the crisis represents a “new challenge” for distinguishing tectonics from volcanic-tectonic processes in the Aegean, where active fault structures and magmatic pathways intersect and interact.

Taken together, these two perspectives demonstrate the dual nature of the 2025 Santorini crisis. While geodetic observations support the presence of shallow magmatic compression, seismological analyses highlight the possible role of regional tectonic stress. Integrating both perspectives provides a more comprehensive interpretative framework for understanding the 2025 disturbance and highlights the necessity of multidisciplinary monitoring strategies when assessing volcanic hazards in complex tectonic–magmatic environments such as Santorini.

This study opens new fields of investigation for the future, both at the level of basic research and the applied monitoring of volcanic systems. A crucial question that arises is whether a single predictive model can be formed that combines seismological, geodetic and geochemical data for the early discrimination between tectonic and volcanic earthquakes. Such a multiparametric approach could significantly enhance the early warning capacity and limit the uncertainty in the assessment of volcanic hazard. An equally interesting prospect is the quantitative investigation of the communication between the Santorini magma chamber and the submarine volcano Colombo, which could be analyzed through 3D tomography and numerical simulation of magma conduits. The documentation of such a mechanism would provide valuable data for understanding the spatial organization and magmatic supply of the South Aegean Arc.

At the same time, the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques in future monitoring can improve the discrimination between different types of seismo-volcanic events, allowing for real-time anomaly detection and strengthening preventive risk management capabilities.

Beyond the purely geophysical aspects, it is equally important to examine the socio-economic dimensions of such crises. Issues such as the impact on tourism, the psychological and economic pressure on residents, as well as the effectiveness of civil protection protocols are key elements of an integrated approach to natural disaster management. Collaboration between scientists, local actors and civil protection can lead to the creation of preventive action plans, which will be based on scientific data and timely information.

Finally, Santorini can act as a reference model for understanding similar volcanic systems in the Aegean, such as those of Nisyros, Milos and Columbus. The development of real-time seismic analysis systems, linked to civil protection mechanisms, could substantially contribute to reducing volcanic risk and improving crisis management at national and regional levels.

5. Conclusions

The analysis of seismic data recorded by local and national networks during the period December 2024–February 2025 indicates a period of intense seismic excitation in the Santorini volcanic complex. In total, more than 10,000 events were identified, with magnitudes ranging from 1.0 < ML < 5.3, and focal depths ranging from 4 km < D < 16 km. The activity was mainly concentrated in the sea area between Santorini, Anydros, Amorgos and Ios, where a clear spatial concentration of epicenters was observed along active E-W-trending faults.

The spatial distribution of epicenters shows that seismicity was organized in elongated zones that coincided with known tectonic faults, such as the Kamari, Columbo and Kameni faults. The highest density of events is in the south and southeast of the caldera, while increased activity also occurs along the Santorini–Amorgos axis. Most tremors originated from depths of 7–13 km, corresponding to the upper crystalline part of the lithosphere, close to the location of the upper magma chamber. Some events with depths of 5 km are probably associated with deeper tectonic processes or with pressure in the lower part of the magmatic system.

Three different stages of evolution can be seen in the temporal distribution of earthquakes:

- Preparatory phase (end of December 2024–mid-January 2025): mild microseismicity without significant events;

- Main phase (late January–mid-February 2025): rapid increase in event frequency, peaking on 10 and 22 February, when earthquakes of Mw = 5.4 and ML = 5.3 occurred, respectively;

- Decay phase (late February 2025): gradual decrease in event rate, following an Omori-type attenuation trend;

- Attenuation phase (end of February 2025): the rate at which earthquakes happen will slowly go down, following the Omori-type attenuation curve.

The system’s point of maximum activation is indicated through the total number of events diagram (Figure 10a), which demonstrates the exponential rise in activity in early February. The frequency of minor earthquakes (ML < 3.0) following the main phase is also shown by the magnitude variation (Figure 10b), which points to a mechanism of relaxation and slow pressure relief in the subvolcanic environment. Two main categories of seismic occurrences were identified by waveform analysis:

- Long-period (LP) earthquakes are lower-frequency, longer-duration events with more complex waveforms that are ascribed to the movement of fluids (gases, steam, or magma) within conduits;

- Volcano-tectonic (VT) earthquakes are high-frequency, short-duration events with different P and S phases, which correspond to brittle fracturing along faults.

Machine learning classification allowed the separation of events into two categories with >85% accuracy, confirming that shallow events (D < 10 km) are related to magmatic or hydrothermal processes, while deeper ones (D > 12 km) correspond to tectonic activation.

The statistical distribution of magnitudes follows the Gutenberg–Richter law. This increase is interpreted as an indication of activation by fluids and magma, characteristic of volcanic areas. The frequency and density of epicenters show high correlation with active fault zones, which confirms the cooperation of tectonic and magmatic processes in the manifestation of the crisis.

Moment tensor inversions for the strongest events (ML ≥ 4.0) revealed a dominant E–W extensional deformation with dip angles of 50°–60° and slip angles of –80° to –90°, characteristic of the extensional tectonic regime of the South Aegean.

For the 10 February 2025 (Mw = 5.4) earthquake, the solution indicated a focal depth of 9 km and a significant non-double-couple component (CLVD = 45%), suggesting a mixed tectono-magmatic mechanism. Comparison of moment tensor solutions from international centers (GFZ, INGV, NEIC, NOA) showed minor differences in depth (7 km–12 km) and slip angle, confirming a consistent extensional character of faulting and a likely contribution of magmatic overpressure to the generation of the events.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pichon, X.L.; Angelier, J. The Hellenic arc and trench system: A key to the neotectonic evolution of the eastern Mediterranean area. Tectonophysics 1979, 60, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, D. Active tectonics of the Alpine-Himalayan belt: The Aegean Sea and surrounding regions. Geophys. J. Int. 1978, 55, 217–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Feng, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; He, X.; Karakaş, Ç.; Tian, Y. Source characteristics and exacerbated tsunami hazard of the 2020 MW 6.9 Samos earthquake in eastern Aegean Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2022, 127, e2022JB023961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drymoni, K.; Browning, J.; Gudmundsson, A. Spatial and temporal volcanotectonic evolution of Santorini volcano, Greece. Bull. Volcanol. 2022, 84, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francalanci, L.; Vougioukalakis, G.; Fytikas, M. Petrology and volcanology of Kimolos and Polyegos volcanoes within the context of the South Aegean arc, Greece. In Geological Society of America eBooks; GeoScience World: McLean, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, N. Santorini Volcano Geological Society Memoir Number 19: T.H. Druitt, L. Edwards, R.M. Mellors, D.M. Pyle, R.S.J. Sparks, M. Lanphere, M. Davies and B. Barreirio. Geological Society of London, 1999. ISBN 1-86239-048-7, GB£70.00, US$117.00. Appl. Geochem. 2001, 16, 1286–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McVey, B.; Hooft, E.; Heath, B.; Toomey, D.; Paulatto, M.; Morgan, J.; Nomikou, P.; Papazachos, C. Magma accumulation beneath Santorini volcano, Greece, from P-wave tomography. Geology 2019, 48, 231–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A.V.; Stiros, S.; Feng, L.; Psimoulis, P.; Moschas, F.; Saltogianni, V.; Jiang, Y.; Papazachos, C.; Panagiotopoulos, D.; Karagianni, E.; et al. Recent geodetic unrest at Santorini Caldera, Greece. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoutsis, I.; Papanikolaou, X.; Floyd, M.; Ji, K.H.; Kontoes, C.; Paradissis, D.; Zacharis, V. Mapping inflation at Santorini volcano, Greece, using GPS and InSAR. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 40, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, M.M.; Moore, J.D.P.; Papanikolaou, X.; Biggs, J.; Mather, T.A.; Pyle, D.M.; Raptakis, C.; Paradissis, D.; Hooper, A.; Parsons, B.; et al. From quiescence to unrest: 20 years of satellite geodetic measurements at Santorini volcano, Greece. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 2014, 120, 1309–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oynakov, E.; Aleksandrova, I.; Popova, M. Characteristics of the 2025 Santorini-Amorgos seismic swarm. Geofizika 2025, 42, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiros, S.C.; Psimoulis, P.; Vougioukalakis, G.; Fyticas, M. Geodetic evidence and modeling of a slow, small-scale inflation episode in the Thera (Santorini) volcano caldera, Aegean Sea. Tectonophysics 2010, 494, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomikou, P.; Carey, S.; Papanikolaou, D.; Bell, K.C.; Sakellariou, D.; Alexandri, M.; Bejelou, K. Submarine volcanoes of the Kolumbo volcanic zone NE of Santorini Caldera, Greece. Glob. Planet. Change 2012, 90–91, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroulis, S.; Mavrouli, M.; Sarantopoulou, A.; Antonarakou, A.; Lekkas, E. Increased Preparedness During the 2025 Santorini–Amorgos (Greece) Earthquake Swarm and Comparative Insights from Recent Cases for Civil Protection and Disaster Risk Reduction. GeoHazards 2025, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Products that are No Longer Disseminated on the CLMS Website. Available online: https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/products-that-are-no-longer-disseminated-on-the-clms-website (accessed on 6 December 2025).

- Questions and Answers about the Earthquakes Near SANTORINI. Available online: https://www.gfz.de/en/press/news/details/fragen-und-antworten-zu-den-erdbeben-bei-santorini (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Ioc.unesco.org. Santorini Ongoing Earthquake Swarm. Available online: https://www.ioc.unesco.org/en/articles/santorini-ongoing-earthquake-swarm?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Isken, M.P.; Karstens, J.; Nomikou, P.; Parks, M.M.; Drouin, V.; Rivalta, E.; Crutchley, G.J.; Haghighi, M.H.; Hooft, E.E.E.; Cesca, S.; et al. Volcanic crisis reveals coupled magma system at Santorini and Kolumbo. Nature 2025, 645, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, S. Moving Magma Under Santorini Lifted the Island and Caused Thousands of Earthquakes. Discover Magazine, 25 September 2025. Available online: https://www.discovermagazine.com/moving-magma-under-santorini-lifted-the-island-and-caused-thousands-of-earthquakes-48067 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Smith, H. State of Emergency Declared on Santorini After Earthquakes Shake Island. The Guardian, 6 February 2025. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/feb/06/state-of-emergency-declared-on-santorini-after-earthquakes-shake-island (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Baumard, M.; Rafenberg, M. Shaken by 10,000 Earthquakes, Greece’s Santorini Island is Left Deserted by its Inhabitants. Le Monde, 11 February 2025. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/en/environment/article/2025/02/11/shaken-by-10-000-earthquakes-greece-s-santorini-island-is-left-deserted-by-its-inhabitants_6738009_114.html (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Chouliaras, G.; Drakatos, G.; Makropoulos, K.; Melis, N.S. Recent seismicity detection increase in the Santorini Volcanic Island Complex. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2012, 12, 859–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zobin, V.M. Significant volcano-tectonic earthquakes and their role in volcanic processes. Volcan. Seismol. 2025, 229–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouet, B.A. New methods and future trends in seismological volcano monitoring. Monit. Mitig. Volcano Hazards 1996, 23–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNutt, S.R. Volcanic seismology. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 2005, 33, 461–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, R.; McCausland, W. Volcano-tectonic earthquakes: A new tool for estimating intrusive volumes and forecasting eruptions. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 2016, 309, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatsios, T.; Cigna, F.; Tapete, D.; Sakkas, V.; Pavlou, K.; Parcharidis, I. Copernicus Sentinel-1 MT-INSAR, GNSS and Seismic Monitoring of deformation Patterns and Trends at the Methana Volcano, Greece. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newhall, C.G.; Dzurisin, D. Historical unrest at large calderas of the world. U.S. Geol. Surv. 1988. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrapkiewicz, K.; Paulatto, M.; Heath, B.; Hooft, E.; Nomikou, P.; Papazachos, C.; Schmid, F.; Toomey, D.; Warner, M.; Morgan, J. Magma chamber detected beneath an arc volcano with high-resolution velocity images. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, A. Statistical analysis of Swarm satellite data for assessing the effectiveness of ionospheric precursors of earthquakes. EGU Gen. Assem. 2020. preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahm, T. On the shape and velocity of fluid-filled fractures in the Earth. Geophys. J. Int. 2000, 142, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styron, R.; Pagani, M. The GEM Global Active Faults Database. Earthq. Spectra 2020, 36 (Suppl. S1), 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Geophysics—Geothermics. Available online: http://www.geophysics.geol.uoa.gr/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).