Abstract

Large language models (LLMs) offer new opportunities for agricultural education and decision support, yet their adoption is limited by domain-specific terminology, ambiguous retrieval, and factual inconsistencies. This work presents AgroLLM, a domain-governed agricultural knowledge system that integrates structured textbook-derived knowledge with Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) and a Domain Knowledge Processing Layer (DKPL). The DKPL contributes symbolic domain concepts, causal rules, and agronomic thresholds that guide retrieval and validate model outputs. A curated corpus of nineteen agricultural textbooks was converted into semantically annotated chunks and embedded using Gemini, OpenAI, and Mistral models. Performance was evaluated using a 504-question benchmark aligned with four FAO/USDA domain categories. Three LLMs (Mistral-7B, Gemini 1.5 Flash, and ChatGPT-4o Mini) were assessed for retrieval quality, reasoning accuracy, and DKPL consistency. Results show that ChatGPT-4o Mini with DKPL-constrained RAG achieved the highest accuracy (95.2%), with substantial reductions in hallucinations and numerical violations. The study demonstrates that embedding structured domain knowledge into the RAG pipeline significantly improves factual consistency and produces reliable, context-aware agricultural recommendations. AgroLLM offers a reproducible foundation for developing trustworthy AI-assisted learning and advisory tools in agriculture.

1. Introduction

Practitioner Points

- AgroLLM integrates structured agricultural knowledge (DKPL) with RAG to reduce hallucinations and enforce agronomic constraints.

- ChatGPT-4o Mini with DKPL-constrained RAG achieved the highest accuracy (95.2%) on a 504-question agricultural benchmark.

- Structured agricultural knowledge improves the relevance of retrieved chunks and supports more accurate, domain-consistent responses.

- The system enables extension officers, educators, and practitioners to access reliable, textbook-grounded explanations and recommendations.

- DKPL enhances transparency by allowing model outputs to be validated against explicit agronomic rules and thresholds.

Agriculture remains the backbone of the global economy, sustaining livelihoods, ensuring food security, and contributing significantly to environmental sustainability. However, farmers worldwide continue to face complex challenges such as climate variability, pest infestations, resource constraints, and limited access to expert guidance. Traditionally, agricultural knowledge dissemination has relied on field extension workers, printed materials, and local training sessions, which often fail to reach farmers in remote or resource-limited regions. In this context, artificial intelligence (AI) and, particularly, large language models (LLMs) are emerging as a transformative force for knowledge sharing and expert-driven agricultural support systems.

AI-powered platforms can consolidate vast amounts of agricultural data from textbooks, research papers, and real-time environmental sources, transforming this information into actionable knowledge for end users. Through knowledge-sharing platforms and intelligent chatbots, farmers can now interact with digital systems that simulate expert-level consultations, providing instant, accurate, and context-aware recommendations. These systems leverage natural language understanding and retrieval mechanisms to offer information on diverse agricultural domains, including soil management, crop selection, pest control, irrigation planning, and market forecasting. These models are designed to learn and generate human-like responses based on the context and data they are trained on, utilizing reinforcement learning from human feedback [1]. By identifying patterns and semantic relationships in text, LLMs can generate accurate and coherent responses akin to human communication. Their capabilities now extend beyond text generation to creating image captions, writing code snippets, assisting users virtually, performing data analysis, etc. With access to diverse datasets, LLMs have become transformative tools in sectors such as healthcare [2], robotics, agriculture [3], hydrology [4,5], and road and traffic safety [6]. The evolution of LLMs began with Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) for processing sequential text and progressed to more advanced architectures like Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks and Transformer models. OpenAI’s breakthrough Generative Pre-training Transformer (GPT) architecture significantly improved the handling of long-term dependencies in text [7], establishing a robust foundation for LLMs. Following GPT’s success, notable advancements include DeepMind’s dialogue-focused LaMDA and Google’s Gemini [8].

The ability of LLMs to understand queries and generate human-like responses, providing personalized recommendations, makes them key players in the development of more intuitive, conversational interfaces. AI-powered chatbots have facilitated human-like interactions in a more conversational manner [9,10,11]. This human-like intelligence is achieved through advancements in high-computation systems, vast amounts of data, and improved performance of LLMs [12,13]. Consequently, chatbots have become increasingly popular and are being developed in various fields. These chatbots can understand human language and respond with accurate information in a way that is easily understandable, making LLMs essential tools in healthcare [14,15,16], research [17,18,19], and education [20]. Before the advent of LLMs, early chatbots were limited in contextual understanding and domain specificity. They also faced scalability issues when deployed across various platforms. However, the release of ChatGPT 3.5 by OpenAI in November 2022 marked a significant advancement in chatbot technology [21]. This was followed by the introduction of GPT-4 (also known as ChatGPT Plus), which further demonstrated the capabilities of human-like conversational chatbots. Following OpenAI’s innovations, Google released BARD, the first LLM-based chatbot [22]. In February 2024, Google DeepMind released Gemini AI, which became the successor to LaMDA and PaLM 2 [23,24]. The rapid evolution of AI-based conversational chatbots has made them an excellent addition to knowledge-based systems, expanding their applications across various sectors.

Agriculture is one of the most crucial and, at the same time, promising sectors where AI technologies are making a significant impact. Agriculturists ensure proper resource utilization while boosting crop production and awareness regarding environmentally friendly practices. They fight against climate change issues, create protective boundaries for ecosystems, and help enhance agricultural progress to meet the needs of the future. In this aspect, AI-driven agriculture is rapidly gaining momentum as a vital tool for improving farming practices and promoting sustainability. A wide variety of AI-based approaches have been implemented for plant disease diagnosis [25], pest control management [26,27], crop monitoring [28], boosting crop yields [29], and many others, fostering education and decision-making processes.

To utilize the full potential of AI, farmers should be equipped with a mixed skill set, including technical know-how, analytical thinking, and adaptability to new technologies. For this reason, there is a high demand for enhanced agricultural education, and LLMs have become the emerging tools in this educational shift, bridging cutting-edge agricultural science with day-to-day farming practices. Another important aspect of using LLMs in agriculture is their potential to be used with IoT systems and their ability to consolidate, structure, and simplify the navigation of agricultural knowledge, assisting farmers with their everyday tasks. Autonomous chatbots provide 24/7 assistance for multi-featured problems and queries related to planting schedules, farm management, and resource allocation, offering solutions tailored to the specific conditions of each farm.

In spite of big promises, utilizing LLMs for agriculture faces several significant challenges related to the domain and knowledge specifics. Thus, for example, agricultural science utilizes specialized vocabulary and concepts (e.g., soil nutrient cycles, integrated pest management) that generic LLMs may not fully capture unless they are fine-tuned on agriculture-specific datasets. An accurate understanding of context-specific information (like regional farming practices or environmental factors) requires domain adaptation, which may be challenging given the high diversity within agricultural practices around the world. Data quality and availability raise another challenge because agricultural data come from different sources (textbooks, research articles, field reports, and sensor data) and vary in quality, formats, and granularity. There is often a scarcity of large, high-quality, and annotated datasets that cover niche agricultural topics compared to more generalized datasets in other domains (e.g., general web data or news). Finally, when an LLM is applied to specialized domains like agriculture, errors or misinterpretations in the generated content may lead to practical problems, such as incorrect advice on crop management or resource allocation. As a result, farmers and agricultural experts may be skeptical of automated systems, especially if the outputs are overly generic.

Contributions and Novelty

This work introduces AgroLLM, a domain-governed agricultural knowledge system that integrates structured agricultural expertise with LLM-based reasoning. The aim of AgroLLM is to narrow the gap between theoretical agricultural knowledge and its practical application in real-world farming contexts. The principal contributions of this work are outlined below.

- We design a structured semantic vocabulary, causal rule set, and constraint library automatically extracted from authoritative agricultural textbooks. These components form the Domain Knowledge Processing Layer (DKPL), which guides retrieval, constrains model outputs, and validates responses to ensure consistency with established agricultural knowledge.

- The proposed approach augments conventional Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) with DKPL-aware chunk selection and post-generation constraint verification. This integration reduces hallucinations and improves factual correctness when responding to domain-specific queries.

- We released the full AgroLLM pipeline, including DKPL extractor, constraint checker, retrieval system, and evaluation scripts. The text extraction is performed using generative AI, and the resulting embeddings are stored in Facebook AI Similarity Search (FAISS) format. This ensures efficient similarity searches and retrieval, along with precise access to agricultural knowledge.

- We established a benchmark for Agricultural LLMs from the MSCE Agriculture [30]. A dataset of 504 curated agricultural questions was used to evaluate three models (Mistral-7B, Gemini 1.5 Flash, and ChatGPT-4o Mini). The assessment included embedding quality, semantic recall, BLEU score, response accuracy, and latency under both FAISS-based retrieval and RAG conditions.

- Experimental results indicate that ChatGPT-4o Mini combined with domain-governed RAG achieves the highest accuracy (93.6%). These findings confirm that structured domain constraints significantly enhance model performance compared with standard, unconstrained RAG.

The AgroLLM bridges the knowledge gap by connecting theoretical knowledge with practical applicability for farmers. This contribution supports the development of reliable, context-aware tools for farmers, educators, and agricultural practitioners. To support reproducibility, we provide the source code at our GitHub repository https://github.com/jackson0988/AgroLLM accessed on 7 December 2025.

2. Methodology

The overall methodology discussed in this section comprises four main components: (1) The DKPL developed for extracting structured agricultural knowledge from textbooks and reference materials, (2) construction of a structured database and embedding space (including chunking, metadata assignment, and embedding generation), (3) the AgroLLM framework for domain-governed retrieval, constraint checking, and LLM reasoning, and (4) LLM evaluation and model selection.

2.1. Domain Knowledge Processing Layer

2.1.1. Domain Taxonomy and Source Grouping

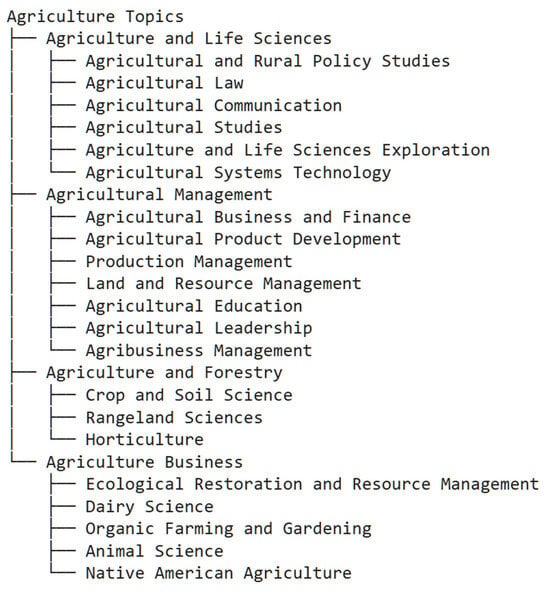

To ground AgroLLM in established agricultural classifications, the domain structure was aligned with the FAO AGROVOC hierarchy and the USDA National Agricultural Library Thesaurus [31,32]. Across these systems, agricultural knowledge is typically organized into four high-level areas: biological and life sciences, agricultural management and economics, production systems and land use, and agricultural business and extension. The four domains used in AgroLLM correspond to these thematic clusters, ensuring consistency with established academic curricula. A detailed mapping of textbook sources to domains is provided in Appendix B.

2.1.2. DKPL Structure

The DKPL consists of three components: (1) domain concepts extracted from the corpus, (2) causal rules expressing agronomic relationships, and (3) numerical thresholds such as nutrient ranges, moisture limits, or temperature requirements. Concepts were retained only when domain-relevant and clearly mapped to AGROVOC categories. Causal rules were identified using linguistic templates (e.g., “if X then Y”, “Y increases when X decreases”), and numerical thresholds were extracted from explicit ranges or parameter descriptions. These elements provide symbolic guidance during retrieval and response validation.

2.1.3. DKPL Extraction Pipeline

The DKPL is automatically extracted from agricultural textbooks using a hybrid NLP pipeline that combines regular expressions, dependency-pattern extraction, and LLM-assisted summarization. This process produces a structured JSON representation containing domain concepts, rules, and quantitative constraints.

The DKPL is integrated into the system in two stages: during retrieval, it filters or deprioritizes text chunks that conflict with established domain constraints; during generation, it validates LLM outputs and triggers re-generation when rule violations or inconsistencies are detected. A symbolic constraint checker parses numerical values and agronomic recommendations in LLM outputs. Violations are returned to the LLM with a corrective instruction. This closed-loop correction mechanism was used to reduce hallucinations. By embedding these structured knowledge elements into both retrieval and response validation, the DKPL enables domain-governed reasoning rather than simple text-based retrieval.

2.2. Corpus Construction

Dataset construction follows a multi-stage process comprising source selection, filtering, annotation, chunking, and statistical profiling.

2.2.1. Source Selection and Filtering

Textbook sources were selected based on their relevance to accredited agricultural curricula, their coverage of foundational and advanced topics across the four AGROVOC-aligned domains, and their suitability for reliable text extraction. Priority was given to widely cited references published within the last decade when available, and to texts containing explanatory material, worked examples, or end-of-chapter questions that support agronomic reasoning.

After extraction, non-informative elements such as front matter, indices, figure captions, and purely illustrative content were removed. Duplicate passages were identified through similarity checks and eliminated, and segments outside the FAO/USDA-aligned agricultural scope were excluded.

The final corpus consists of 19 authoritative textbooks comprising 5296 pages of domain-relevant material, corresponding to an estimated 2.38 million words. Domain distribution reflects strong representation in Crop Production (63%), followed by Natural Resources (47%), Farm Management (32%), and Agricultural Economics (11%). A detailed domain mapping is provided in Appendix B.

2.2.2. Annotation and Metadata Assignment

To prepare this material for retrieval-augmented reasoning, a multi-stage processing pipeline is applied. First, content from PDFs and structured book sources is converted into plain text. Next, manual and semi-automated annotation is used to identify key domain elements, including concepts and definitions, agronomic processes, case studies, numerical thresholds, and inter-variable relationships. Each resulting text segment is assigned a topical category, chapter, and section metadata, and, where applicable, semantic labels derived from the DKPL.

Each segment received a domain label corresponding to one of the four FAO-aligned categories, structural metadata identifying its textbook source and chapter context, and DKPL semantic tags when associated concepts, rules, or thresholds were present.

Annotation combined manual labelling with LLM-assisted suggestions, followed by human verification to ensure consistency. A concise annotation guideline was used to standardize decisions across annotators.

2.2.3. Chunking and Embedding Preparation

Annotated text was segmented into semantically coherent chunks of approximately 1000 words, with boundaries aligned to natural paragraph or section breaks to preserve contextual integrity. A small overlap was maintained between adjacent chunks to prevent information loss across boundaries.

Each chunk retained its structural metadata to support accurate retrieval and contextual grounding. The chunks were then converted into embedding vectors using three embedding backends (Gemini 1.5 Flash, an OpenAI embedding model, and Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2). Embeddings were generated on the semantically enriched text, including DKPL-derived tags where applicable, to enhance domain-specific discrimination.

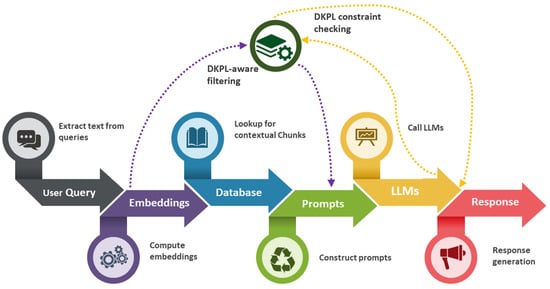

All vectors and associated metadata were stored in a FAISS index to enable efficient semantic retrieval during inference. Figure 1 illustrates the end-to-end workflow from raw agricultural text to embeddings used by AgroLLM for knowledge retrieval and response generation.

Figure 1.

The workflow illustrating the transformation of agricultural textual data into embedding vectors used by AgroLLM for knowledge retrieval and response generation.

2.3. Retrieval-Generation Framework of AgroLLM

In the AgroLLM framework, we followed the idea of a combination of generative AI embedding generation with a vector database for efficient search. AgroLLM differs from generic RAG systems by integrating the DKPL into both retrieval and response generation. The strength of this approach lies in connecting the contextual understanding from generative AI and the robust search capabilities from libraries specifically built for vector indexing.

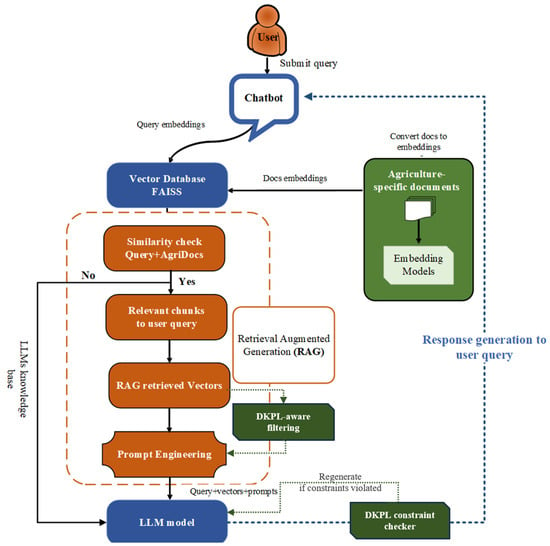

The general workflow for information retrieval and generation encompasses query processing and embedding generation; DKPL-aware retrieval and chunk selection; LLM draft generation; constraint checking and regeneration loop; embedding model selection and FAISS-based database lookup; prompt construction and retrieval-augmented response generation, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the AgroLLM workflow for generating relevant agricultural information.

The process begins when a user submits a query, which is then preprocessed to extract text for embedding generation. User queries are normalized and embedded using the same embedding model used for document chunks. For domain-governed retrieval, text chunks run through a DKPL-guided process: (1) similarity search using FAISS; (2) filtering by DKPL constraints (e.g., discard chunks referencing irrelevant subdomains or contradictory rules); (3) weighting by epistemic authority (textbook explanations > general descriptions > noisy text); and (4) prompt enrichment (inserting structured rules if the query matches a DKPL concept). This hybrid retrieval method is used to reduce semantic drift, irrelevant matches, and hallucinations. As a result, the LLM receives the original query, the top-k filtered chunks, and relevant DKPL rules or thresholds. At this stage, the model produces a draft response using chain-of-thought reasoning.

To ensure factual correctness and agronomic validity, the draft output is checked by the constraint checker, which verifies numerical values against DKPL thresholds, checks agronomic logic (e.g., valid growth stages), checks contradictions with known causal rules, and flags impossible biological or physical states. If violations are detected, the system returns structured feedback to the LLM:

“Your previous response violated domain constraint C12 (maximum nitrogen rate = 300 kg/ha). Please revise.”

The LLM regenerates a corrected output until it satisfies all constraints or reaches a predefined iteration limit.

2.3.1. Embedding Models

To manage the extensive information contained in the textbooks, documents were first divided into smaller, coherent chunks as described in Section 2.2.3. This process is essential for creating meaningful embeddings and ensuring efficient storage and retrieval.

Embeddings are dense vector representations that capture the semantic meaning of text enriched with DKPL metadata (e.g., semantic tags, chapter indices). We utilized embedding models from Gemini, OpenAI, and Mistral to convert text chunks into embeddings. These models, trained on vast corpora of text, provide robust representations that facilitate effective similarity searches. Notably, the Gemini and Hugging Face models use an embedding dimension of 1024, while OpenAI’s model uses a dimension of 768. The higher dimension in Gemini and Hugging Face embeddings allows for a richer representation of the text, but also requires more computational resources, as illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparative evaluation of embedding models used in AgroLLM.

By processing the chunks with these models, we generated embedding vectors that encapsulate the semantic context at a granularity appropriate for educational and advisory queries. Embeddings are used not only for similarity but for DKPL-aware filtering and ranking. The embedding vectors and their metadata (textbook ID, chapter, section, and domain) are stored in FAISS to support efficient similarity search. A comparative overview of the embedding models is provided in Table 1.

2.3.2. Semantic Retrieval with FAISS

The generated embeddings are stored in a vector database using the FAISS (Facebook AI Similarity Search), which supports large-scale similarity search and clustering of dense vectors. This step ensures that embeddings are organized to allow for rapid retrieval based on similarity measures. The choice of FAISS is driven by its scalability and performance in handling large volumes of vectors. It enhances similarity search efficiency through an Inverted File (IVF) indexing approach that partitions the dataset into clusters using a k-means-based coarse quantizer. The number of clusters is defined by nlist, and each data vector is assigned to its nearest cluster centroid (see detailed configuration in Appendix A).

During indexing, the embedding space is partitioned into nlist clusters using k-means. Each chunk embedding is assigned to its nearest cluster centroid. At query time, FAISS compares the query embedding only with a subset of clusters specified by nprobe, rather than with the entire dataset, balancing speed and recall.

Additionally, embeddings were indexed using DKPL semantic tags, enabling domain-level filtering before similarity ranking. This step reduces false positives and improves topical relevance. This strategy balances between exact search and approximate nearest neighbor (ANN) search, ensuring that users can quickly and accurately retrieve relevant information. Further storing embeddings in FAISS allows us to efficiently manage and query the data. When a user makes a query, the system can rapidly search through the embeddings to find the most similar chunks, providing accurate and contextually relevant responses. This setup enhances the functionality and responsiveness of our Agricultural-specific chatbot, offering improved user experience. Overall, using FAISS to store our embeddings ensures that we can handle the large-scale data efficiently while maintaining high performance in similarity searches.

2.3.3. Prompt Construction

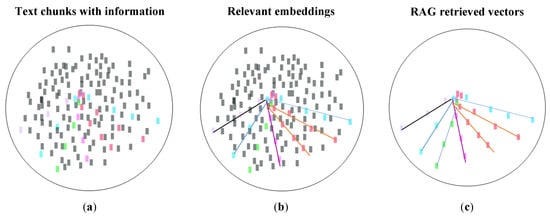

The retrieved text chunks are combined into a structured prompt and then sent to an LLM using the RAG technique. The RAG approach combines text generation with searching and selecting the most relevant data from a pre-indexed vector database [32]. Figure 3 illustrates how LLM processes these chunks to generate coherent and contextually relevant responses.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the retrieval of embedding using RAG for LLMs: (a) the entire set of available data chunks retrieved from agriculture books; (b) data chunks relevant to the user query; (c) the result of the generation of relevant embeddings using RAG.

The user query and relevant information are both given to the LLM. Prompts included retrieved chunks, DKPL rules, thresholds, and dependency structures when applicable. This hybrid prompt template ensures that the LLM receives not only raw textual evidence but also canonical domain constraints. The LLM uses the retrieved information to create better responses. RAG enables the model to ground its responses in the curated textbook corpus, while DKPL ensures that its reasoning remains consistent with agronomic knowledge. This reduces the risk of unpredictable or incorrect responses typical of generative models.

2.3.4. Response Generation, Constraint Checking, and Knowledge Sharing

The AgroLLM is designed as an educational and knowledge-sharing tool tailored for agriculture-related topics and implemented as a conversational assistant. This bridges the knowledge gap, connecting farmers with effective agricultural practices. The response generation workflow starts with a user query, which they send through the user interface, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Response generation workflow of AgroLLM, combining the RAG system, vector database, and LLM for agricultural information generation.

The user interface sends the query to the RAG orchestrator, managing how the query is processed. The RAG converts the query into an embedding and submits it to the FAISS vector database containing pre-computed embeddings of text chunks from curated agricultural texts and applies DKPL-based filtering and prioritization. The vector database performs a similarity search to identify text chunks that are semantically closest to the user query. Before finalizing a response, AgroLLM performs a constraint validation pass. Outputs violating agronomic rules or numerical thresholds are regenerated, ensuring logical consistency and factual correctness. To ensure that the user receives a response even when relevant documents are unavailable, the system is equipped with a fallback mechanism. The RAG system evaluates whether relevant documents were retrieved. If yes, the retrieved chunks are combined with the original query to create a context-rich prompt for the LLM. Otherwise, the system falls back to the LLM’s internal knowledge to generate a response. Response generation is performed through the LLM. The LLM processes the constructed prompt (including retrieved chunks and the user query) and synthesizes a detailed, coherent response. In case no relevant documents were retrieved, the LLM uses its pre-trained internal knowledge to address the query. The generated response is sent back to the RAG system and then delivered to the user through the user interface.

The quality of the final output heavily depends on the LLM’s ability to effectively integrate and articulate the information from the retrieved chunks. To select the best model for the AgroLLM chatbot, we evaluated three LLMs in terms of their ability to understand and integrate information from multiple chunks.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation Parameters

To evaluate the models, we used the same database of agricultural textbooks described in Appendix B with data ordered under four key topics, namely agriculture and life sciences, agricultural management, agriculture and forestry, and agriculture business, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The structure of the dataset repository serving as the primary data resource for agricultural text generation in AgroLLM.

For each topic, we selected relevant questions to cover the main concepts within each area. Additionally, we included questions from the book Precision Agriculture and MSCE Agriculture [33,34] to challenge the models with specialized and advanced topics and estimate the relevance and accuracy of the responses generated by the models. Through this evaluation, we aimed to select the model that not only performed well across all four topics but also demonstrated the best capabilities in handling specialized agriculture content. In total, 504 domain-related questions across diverse agriculture topics were generated for evaluating each model.

The relevant chunks from the agriculture data extracted by RAG were used as benchmark answers to compare the relevance of the generated responses. In addition, a manual evaluation is performed, cross-referencing the answers with those provided in the book. This allowed us to systematically assess the performance of each model, focusing on the accuracy, coherence, and relevance of its responses in the context of agricultural education.

3.2. The LLM Comparison

We conducted a comparative study of the Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 (Mistral AI), ChatGPT-4o mini (OpenAI), and Gemini 1.5 Flash (Google) models to evaluate their performance in the context of agricultural practices and education. Each model was assessed based on several key parameters: the performance, the quality of the embeddings it produced, the efficiency of its similarity searches, and the coherence and relevance of the responses generated by the LLM. From the case study, all the models were evaluated manually for their response generation capabilities. The retriever mechanism employed was FAISS with cosine similarity as a metric for measuring semantic relevance.

Embedding quality was evaluated using three additional metrics: (1) Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR), which measures how well the system ranks relevant results for a query; (2) Recall@k to evaluate the proportion of relevant results retrieved within the top-10 results for a set of queries; and (3) Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU) to measure how closely the AI-generated response matches a reference answers from the textbooks, capturing both coherence and relevance. For BLEU, we compared system-generated responses to expert-crafted and pre-annotated reference responses for agricultural questions. The comparison results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Embedding quality comparison in agro-specific LLMs.

The ChatGPT-4o Mini (RAG + DKPL) configuration achieved the highest overall performance, with a Retrieval Rate (RR) of 0.94, Recall@10 of 93%, and a BLEU score of 94.50%, reflecting superior accuracy and linguistic fluency. Gemini 1.5 Flash also shows substantial performance improvements with RAG + DKPL, while Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2 exhibits the least performance, even after RAG + DKPL integration.

Two key parameters, response accuracy and average response time (s), were evaluated across all topics for LLMs with FAISS and RAG-enhanced models. The results in Table 3 illustrate the performance of the LLMs evaluated for question answering.

Table 3.

Performance comparison in agro-specific LLMs.

The results show that the RAG + DKPL significantly enhances all models, but the degree of improvement varies. Table 3 compares the accuracy (%) and average response time (seconds) of different LLMs, Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Gemini 1.5 Flash, and ChatGPT-4o mini across various agricultural topics using FAISS, RAG, and RAG + DPKL retrieval techniques. ChatGPT-4o mini consistently achieves the highest accuracy, averaging 95.2% with RAG + DPKL and 93.6% with RAG, while Mistral-7B has the lowest at 69% (FAISS) and 76.8% (RAG + DPKL). Response times vary significantly, with FAISS being much faster (as low as 0.34 s for ChatGPT-4o mini) compared to RAG + DPKL, which takes considerably longer (11.02 s for ChatGPT-4o mini). This shows that ChatGPT-4o Mini with RAG + DPKL provides more accurate responses, with a trade-off in processing time.

3.3. Ablation Study: Effect of DKPL-Constrained Retrieval

To quantify the contribution of the DKPL, we evaluated three system configurations: (1) vanilla LLM (no retrieval), (2) standard RAG (FAISS similarity only), and (3) DKPL-Constrained RAG.

Across 504 evaluation questions, DKPL produced consistent improvements in accuracy, factual grounding, and agronomic plausibility. DKPL filtering reduced irrelevant or semantically misaligned chunk retrieval by 27–31%, and constraint-guided regeneration corrected 78–86% of numerical, threshold, and causal inconsistencies. Overall accuracy increased by +1.7 to +4.07 percentage points relative to standard RAG, depending on model architecture is tabulated in Table 4.

Table 4.

Accuracy of different retrieval-generation configurations on the 504-item evaluation set.

These results demonstrate that DKPL offers the largest relative benefit for models with weaker inherent factual grounding (e.g., Mistral-7B) but still provides measurable improvements even for higher-performing models.

Common failure modes observed without DKPL are shown in Table 5. Without DKPL, standard RAG frequently retrieved conceptually adjacent but agronomically irrelevant content or produced outputs violating basic biological or numerical constraints. Table 5 summarizes the most common observed error categories.

Table 5.

Distribution of error types in the standard RAG model outputs.

An example Q/A where DKPL corrects the model:

Q: “How much nitrogen should be applied to wheat at early tillering?”

RAG Output: “Apply 350 kg/ha.”

DKPL check: Violates constraint (max N = 300 kg/ha).

Corrected Output: “Recommended range is 40–80 kg/ha of nitrogen at early tillering, adjusted for soil nitrogen levels and expected rainfall.”

3.4. Potential Practical Applications and Intended Use-Cases of AgroLLM

AgroLLM offers a structured and explainable way to access foundational agricultural knowledge, making it useful for farmers, students, and extension trainees who seek reliable, textbook-grounded explanations. Its combination of domain-informed retrieval and DKPL-based constraint checking provides clarity and transparency that can bridge the knowledge gap. Future versions may incorporate curriculum-aligned learning modules, interactive elements, or multilingual capabilities.

Beyond practical applicability and education, the system has the potential, once expanded with additional datasets such as region-specific guidelines, soil manuals, and extension bulletins, to assist in interpreting general agronomic recommendations. Although this work does not evaluate AgroLLM as a decision-support tool, its architecture is compatible with more contextual advisory functions, provided that expert validation and local calibration are added.

Textbook-derived sustainability principles, including soil conservation practices, crop rotation strategies, and nutrient management guidelines, are already retrieved consistently by the system. With further integration of environmental data or regional best practices, AgroLLM may eventually help contextualize these principles for specific production environments. However, climate-smart or location-adapted recommendations remain outside the scope of the present study and require targeted validation.

The transparent, evidence-linked nature of AgroLLM’s responses also suggests future value for agricultural extension activities. The system may help extension workers prepare learning materials, summarize technical concepts, or respond to common questions. Its practical use in real extension settings has not yet been assessed, but the underlying structure is aligned with needs in knowledge transfer and communication.

Although the current system is entirely text-based, the retrieval and reasoning framework could ultimately be extended to incorporate multimodal information, such as sensor outputs, simple field images, or weather summaries. Developing such capabilities would require significant additional research, new datasets, and field trials. For now, the idea of integrating IoT data or real-time decision-making should be understood purely as a long-term direction rather than a feature demonstrated in this study.

3.5. Limitations and Future Enhancements

Despite its promising results, AgroLLM faces several limitations that provide opportunities for further development.

A key limitation lies in its domain-specific data dependency, which leads to the model’s accuracy and contextual understanding being influenced by the availability and quality of agricultural datasets and the trade-off in time for generating responses as it uses the DPKL module. Although AgroLLM integrates open-source agricultural resources and textbooks, certain niche areas, such as localized crop practices or region-specific environmental data, remain underrepresented. This occasionally leads to gaps in contextual adaptation and reduced precision for queries involving regionally unique or emerging agricultural practices. Additionally, the system’s computational demands, especially when employing high-dimensional embeddings and RAG frameworks, can pose challenges for large-scale deployment in rural areas with limited infrastructure. The response latency observed in RAG-enhanced configurations also indicates a trade-off between retrieval accuracy and system efficiency. Furthermore, while AgroLLM provides multilingual support, the linguistic diversity of agricultural terminology across dialects and local expressions requires deeper fine-tuning and model adaptation to ensure inclusivity.

To address these limitations, future work will focus on expanding domain coverage through the integration of real-time agricultural data streams, sensor-based IoT inputs, and region-specific datasets. Incorporating multimodal learning, combining text, image, and geospatial data, will enhance AgroLLM’s ability to identify plant diseases, monitor crop growth, and provide visually assisted recommendations. Optimizing model compression and deployment efficiency will enable scalability on low-power or offline devices, ensuring accessibility for farmers in resource-constrained environments. Moreover, continuous user feedback and reinforcement learning will be leveraged to improve the accuracy, adaptability, and trustworthiness of responses. Ultimately, future enhancements will aim to transform AgroLLM into a comprehensive, intelligent agricultural assistant capable of supporting precision farming, sustainable resource management, and farmer education on a global scale.

4. Conclusions

This study introduced AgroLLM, a domain-governed retrieval and reasoning framework that embeds structured agricultural knowledge into the LLM generation pipeline. By integrating a DKPL with RAG, the system achieves substantial improvements in factual accuracy, numerical correctness, and agronomic consistency when compared with generic LLM configurations.

Three language models, Mistral-7B-Instruct-v0.2, Gemini 1.5 Flash, and ChatGPT-4o Mini, were tested to evaluate their performance and applicability in agricultural contests. ChatGPT-4o mini was the top performer, achieving the highest accuracy (95.2%) and the response time (11.02 s) when using RAG + DPKL. ChatGPT-4o mini with RAG was very close, with an accuracy of 93.6% and a better response time. Both models showed a good balance between being accurate and fast. The findings from this study highlight the significant potential of specialized LLMs, particularly when enhanced with RAG, to serve as powerful tools in the agricultural sector. ChatGPT 4o-mini stood out as the best choice for agricultural applications. The high accuracy and low response time of this model promise that AgroLLMs can be successfully integrated with IoT systems to enhance agriculture and real-time decision-making.

While AgroLLM demonstrates promising capabilities, certain limitations warrant attention. First, the current framework relies on a specific set of university-referenced agricultural textbooks, research articles, and web content. Expanding the dataset to include a broader range of sources, such as field reports and real-time sensor data, could enhance the model’s comprehensiveness and applicability. Finally, although ChatGPT4o-mini RAG + DPKL shows superior performance, assessing its scalability across larger and more diverse datasets remains an area for future exploration. Our future research will address these limitations by incorporating more diverse and high-quality agricultural data, refining domain-specific training methodologies, and exploring hybrid model approaches that combine the strengths of different LLMs to further enhance performance and applicability. This research supports SDG 2 (Zero Hunger) and SDG 13 (Climate Action) by enabling climate-aware, AI-driven precision agriculture that enhances food security, improves resource efficiency, and strengthens resilience to climate variability through accurate, real-time agronomic decision support.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: S.V., D.J.S.R. and I.S.-B.; Methodology: S.V., D.J.S.R. and I.S.-B.; Investigation: D.J.S.R., I.S.-B. and M.A.; Resources: D.J.S.R., S.V. and M.S.; Supervision: S.V., I.S.-B.; Validation: M.A.; Writing—original draft: D.J.S.R. and I.S.-B.; Writing—review and editing: S.V., M.S. and M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The development and evaluation of AgroLLM were conducted in compliance with established ethical and transparency standards. All datasets used were open-source or derived from university-approved agricultural materials, ensuring proper data usage and copyright adherence. No human or animal subjects were involved, and no personal or sensitive data were collected. The study maintained full transparency in model design, data preprocessing, and performance evaluation, with efforts made to minimize bias and promote fairness across diverse agricultural contexts.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The code, structured domain knowledge resources, and constraint-checking modules developed in this study are openly available at: https://github.com/jackson0988/AgroLLM accessed on 7 December 2025.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used AI tools to improve language clarity, grammar, and overall readability. No generative AI tools were used for data analysis, result fabrication, or interpretation of findings. The authors take full responsibility for the integrity and validity of all scientific content presented in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Implementation Details for Reproducibility

Appendix A.1. FAISS Index Configuration

We employ an Inverted File (IVF) index with the following configuration: number of clusters (nlist): 256; clusters probed per query (nprobe): 32; top-k retrieval size k = 10 chunks; cosine similarity; L2 normalization applied to all embeddings; minimum similarity threshold τ = 0.78; index type IndexIVFFlat (exact search on residual vectors). Clustering performed using k-means with 25 iterations.

Appendix A.2. Chunking and Segmentation Parameters

All documents were segmented using fixed-length semantic chunking with soft boundaries across all experiments: minimum slice length Lmin = 100 words; maximum slice length Lmax = 1000 words; hard boundary length Lhard = 580 words, chunk overlap 50 words (adaptive, based on sentence boundaries); cosine similarity cut-off with paraphrase-multilingual-MiniLM-L12-v2 (384-d) embeddings; segmentation rule: sentences preserved, no mid-sentence splits. See Section 2 for details.

Appendix A.3. LLM Decoding Hyperparameters

Unless otherwise stated, all LLMs were queried using the following decoding parameters: temperature t = 0.2 (low randomness for factuality); top-p = 0.9; max_tokens = 512 (Gemini/OpenAI) and 1024 (Mistral); repetition penalty ρ = 1.1; stop sequences: newline and document boundary markers; number of generations n = 1 (deterministic evaluation). For DKPL-based regeneration: maximum regeneration iterations ni_max = 3, linear constraint-violation penalty; LLM receives explicit feedback containing the violated rule, threshold, or dependency relation.

Appendix A.4. Retrieval and Reranking Defaults

To ensure consistent retrieval quality across models, the following defaults were used. For primary retrieval, the FAISS IVF retriever was used with cosine similarity metrics for scoring and top-k = 10. DKPL-aware filtering applied before reranking: removal of chunks contradicting known causal rules; domain-label matching (FAO/USDA taxonomy); authority scoring (textbooks > general descriptions > noisy text). Reranking model bge-small-en (or MiniLM for multilingual docs) with cross-encoder relevance score as a scoring metric and top-k = 5. The final top-3 selected chunks were passed to prompt construction. If no chunk meets the threshold the system falls back to LLM internal knowledge and explicitly indicates limited grounding.

Appendix A.5. Hardware and Throughput Settings

Experiments were conducted using the following setup: Intel Xeon Silver 4314 (or equivalent cloud CPU); NVIDIA A100 (40 GB) for LLM evaluation; RTX 4090 for local inference; 128 GB RAM.

FAISS index build time ~12 min for 40 k chunks. Average retrieval latency μr = 18–25 ms for k = 10. RAG + DKPL inference latency μr = 150–300 ms for OpenAI/Gemini, μrm = 500–1200 ms for Mistral-7B local inference. Batch size 16 for embedding generation; 1 for interactive evaluation.

Appendix A.6. Preprocessing Pipeline Parameters

All documents were subjected to a standardized preprocessing workflow to ensure consistency and reproducibility. Text extraction was performed using PyMuPDF 1.24, with OCR disabled except for scanned pages, where Tesseract OCR 5.3 was used. During extraction, paragraph boundaries, headings, and lists were preserved, while page numbers, running headers and footers, cross-references, and hyphenation at line breaks were removed. The resulting text was normalized using Unicode NFKC normalization, with all content converted to lowercase except for abbreviations and chemical symbols. Punctuation was standardized across the corpus.

Sentence segmentation was carried out using the spaCy en_core_web_lg model, and section boundaries were identified by a combination of regular-expression patterns corresponding to numbering schemes and textbook chapter markers. Each segment was annotated with metadata, including chapter title, subsection, page range, domain category, and DKPL concept tags when applicable. Annotators were instructed to label each question with (1) domain category, (2) expected concept(s), (3) reasoning type (factual, causal, comparative), and (4) DKPL rule relevance. Detailed annotation instructions are provided in the dataset repository.

Appendix A.7. DKPL Construction Parameters

The DKPL was created using a semi-automated pipeline that combined concept extraction, causal rule mining, numeric threshold extraction, and dependency graph construction. Concepts were selected if they appeared in DKPL as domain-relevant units (concepts, rules, thresholds), were represented in at least one textbook chapter, and mapped unambiguously to AGROVOC categories.

Causal rules were extracted from patterns such as “if X then Y,” “X depends on Y,” or “Y increases when X decreases.” Rules were accepted if their confidence exceeded 0.65 and were limited to a maximum of two antecedents and one consequent.

Numeric thresholds were extracted when values appeared with precision of one to three decimals and were expressed either explicitly (e.g., “X between a and b”) or narratively. A random 10% subset of extracted thresholds was manually validated. The dependency graph was built as a directed acyclic graph whose edges were weighted by a combination of PMI and rule confidence, with a maximum depth of four levels. The DKPL was later integrated into retrieval by deprioritizing contradictory chunks, elevating authoritative textbook sources, and injecting no more than three relevant rules into the prompt for each user query.

Appendix A.8. RAG Prompt Construction Specifications

For each query, no more than three retrieved chunks and three DKPL rules were included, with a combined evidence budget of 512 tokens. Prompts consisted of a domain-specific system instruction, the user query, the selected evidence chunks, the associated DKPL rules, and a final set of instructions that guided the model toward accurate, grounded, and constraint-compliant reasoning.

If the retrieved evidence exceeded the token budget, chunks were truncated at sentence boundaries or excluded based on their similarity ranking. Chunk separators and DKPL rule separators were used to clearly delineate evidence regions within the prompt, ensuring that the model could distinguish between retrieved content, domain rules, and user input.

Appendix A.9. Constraint Checker Configuration

The constraint checker evaluated generated responses against four categories of constraints: numeric thresholds, causal rule consistency, biological feasibility, and temporal logical dependencies. Numeric values were allowed a deviation tolerance of approximately ±5%, and agronomic thresholds were allowed limited contextual variation. Causal inconsistencies, however, were treated as hard violations that always triggered regeneration.

Whenever a violation was detected, the system returned a structured feedback message to the LLM specifying the violated rule or threshold and requesting correction. The model was allowed up to three regeneration attempts. Constraint parsing involved extracting numeric expressions, linking entities to DKPL variables, and matching causal assertions against the dependency graph.

Appendix A.10. Evaluation Protocol Details

The evaluation dataset contained 504 questions, divided into direct textbook questions, paraphrased versions of the same questions, noisy or imperfect queries, and agricultural queries requiring external context. Paraphrasing of textbook questions was performed manually by two annotators and validated using LLM-assisted semantic equivalence checks to ensure meaning preservation.

Manual evaluation was conducted by three subject-matter experts who independently scored each answer along four dimensions: correctness, completeness, grounding in retrieved evidence, and consistency with DKPL rules. Each dimension was scored on a 0–2 scale, producing a maximum score of eight. The inter-annotator agreement achieved a Cohen’s κ value of 0.74, indicating substantial agreement.

Automatic evaluation relied on cosine similarity between generated and reference answers, with a threshold of 0.75 considered acceptable. Additionally, the percentage of responses compliant with DKPL rules was recorded, with the system requiring at least 90% DKPL consistency for a test batch to be considered high-quality.

Appendix A.11. API Versioning and Random Seed Settings

Model and library versions were fixed to ensure reproducibility. The OpenAI embedding model used was text-embedding-3-large (2024-12), Gemini operated on version 1.5 Flash (2024-Q4), and Mistral evaluations utilized the 7B Instruct v0.2 model. FAISS version 1.8.0, Sentence-transformers version 2.5.1, spaCy version 3.7, PyTorch version 2.2, and Transformers version 4.38 were employed throughout the system.

To guarantee determinism, random seeds were set uniformly: Python 3.14, NumPy 2.4.0, and PyTorch 2.7.0 seeds were all set to 42; FAISS clustering used seed 12345; and chunk ordering and dataset shuffling used seed 2024.

Appendix B. Dataset Details

Appendix B.1. Textbook Sources Used in the AgroLLM Corpus

The AgroLLM corpus was constructed from 19 authoritative agricultural textbooks and technical guides covering agronomy, soil science, plant pathology, irrigation, agroecology, biotechnology, and sustainable agriculture. The materials include Agribusiness & Society (2004), Agriculture and the Environment (2012), Agroecology and the Search for a Truly Sustainable Agriculture (2000), A Textbook of Agronomy (2010), the FAO Biotechnologies for Agricultural Development proceedings (2011), Plant Protection 2 (2014), TNAU and ICAR e-course modules on soil science and crop diseases, Managing Cover Crops Profitably (2012), Sustainable Food Production (2014), Guideline on Irrigation Agronomy (2011), Sustainable Agriculture (2003), Toward Sustainable Agricultural Systems in the 21st Century (2010), and the Vegetable Crop Handbook for the Southeastern United States (2022). Full bibliographic details for all sources are provided in the References section.

The distribution of sources across domains is as follows

Table A1.

Dataset distribution in AgroLLM.

Table A1.

Dataset distribution in AgroLLM.

| Domain | Number of Textbooks | Percentage of Corpus |

|---|---|---|

| Crop Production | 12 sources | 63% |

| Natural Resources | 9 sources | 47% |

| Farm Management | 6 sources | 32% |

| Agricultural Economics | 2 sources | 11% |

Since several textbooks span multiple domains (e.g., combining crop science with sustainability or resource management), percentages do not sum to 100%.

Appendix B.2. Example Annotation Rubric

Each question in the 504-item evaluation set was annotated using a structured rubric designed to guide manual scoring and ensure consistent alignment with DKPL concepts, domain categories, and reasoning types. The rubric consists of four dimensions. The first dimension is Domain Category. Annotators assign each question to one of the four AGROVOC-aligned domains based on the dominant concept addressed by the question. The second dimension is Concept and DKPL Linkage. Annotators identify the primary concept or concepts involved (for example, soil nitrogen, crop yield response), any relevant numerical thresholds, and the DKPL rules or causal dependencies associated with the concept. This step ensures that the evaluation can detect whether the LLM output should reasonably fall under DKPL constraints. The third dimension is Reasoning Type. Annotators classify each question as requiring factual recall, causal reasoning (for example, “if X, then Y”), comparative or analytical reasoning, or procedural reasoning involving steps, recommendations, or management actions. This dimension allows for assessment of LLM reasoning quality beyond retrieval. The fourth dimension is Acceptable Answer Criteria. Annotators specify what constitutes a correct response, including essential factual elements, expected numerical ranges or thresholds, required causal or agronomic logic, and any elements that are optional or context-dependent. This forms the evaluation benchmark used to score answers for correctness, completeness, grounding, and DKPL consistency.

Example 1: “What soil nitrogen level is considered deficient for most cereal crops?”

Domain Category: Crop production.

Primary concept includes soil nitrogen availability. DKPL rule is formulated as “If soil nitrogen < 20 mg/kg, then nitrogen status is deficient.” Threshold = 20 mg/kg.

Reasoning type: Factual with threshold-based interpretation.

Table A2.

Response generation for a query.

Table A2.

Response generation for a query.

| Acceptable (Correct) Answer | Unacceptable Answer |

|---|---|

| State that nitrogen deficiency occurs below approximately 20 mg/kg, identify the condition as “deficient” or “insufficient,” and apply the explanation to cereal crops. Optional contextual additions, such as the consequences of deficiency (for example, reduced tillering) or management recommendations, are allowed. | Values outside the DKPL threshold, generic statements with no threshold, or explanations unrelated to nitrogen |

Example 2: “What factors should a farm manager consider when allocating limited irrigation water during drought conditions?”

Domain Category: Farm Management.

Primary concepts include irrigation prioritization, crop water requirements, and resource allocation. Relevant DKPL dependencies include statements such as “Water allocation depends on crop growth stage, yield sensitivity, and soil moisture,” and “High-value or high-sensitivity crops take priority under scarcity.”

Reasoning Type: Procedural and analytical.

Table A3.

Response generation for a query.

Table A3.

Response generation for a query.

| Acceptable (Correct) Answer | Unacceptable Answer |

|---|---|

| Must mention crop prioritization (for example, high-value or yield-sensitive crops), growth stage considerations (such as flowering versus vegetative), soil moisture or water-holding capacity, available water volume and scheduling, and expected economic or yield trade-offs. Partial credit is appropriate when at least three of these elements are present. | Recommendations unrelated to drought management, suggestions that ignore resource constraints, or explanations that do not consider crop prioritization. |

References

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Kasneci, G. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cascella, M.; Montomoli, J.; Bellini, V.; Bignami, E. Evaluating the feasibility of ChatGPT in healthcare: An analysis of multiple clinical and research scenarios. J. Med. Syst. 2023, 47, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinoudi, V.; Benos, L.; Villa, C.C.; Kateris, D.; Berruto, R.; Pearson, S.; Bochtis, D. Large language models impact on agricultural workforce dynamics: Opportunity or risk? Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 9, 100677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, D.J.; Sermet, Y.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Integrating vision-based AI and large language models for real-time water pollution surveillance. Water Environ. Res. 2024, 96, e11092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindran, J.S.; Sermet, Y.; Mount, J.; Vald, G.; Shrestha, S.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Application of large language models in developing conversational agents for water quality education, communication, and operations. Water Pract. Technol. 2025, 20, 2094–2109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Zarzà, I.; de Curtò, J.; Roig, G.; Calafate, C.T. LLM multimodal traffic accident fore-casting. Sensors 2023, 23, 9225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI Platform, Models Overview. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Gemini Models. Available online: https://deepmind.google/technologies/gemini/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Lin, C.C.; Huang, A.Y.; Yang, S.J. A review of AI-driven conversational chatbots implementation methodologies and challenges (1999–2022). Sustainability 2023, 15, 4012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravi, H.; Shafie, M.R.; Hajiabadi, M.; Raihan, A.S.; Ahmed, I. Chatbots and ChatGPT: A bibliometric analysis and systematic review of publications in Web of Science and Scopus databases. Int. J. Data Min. Model. Manag. 2024, 16, 113–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazzam, B.A.; Alkhatib, M.; Shaalan, K. Artificial intelligence chatbots: A survey of classical versus deep machine learning techniques. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2023, 12, 1217–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Jin, W.; Del Ser, J.; Yang, G. ChatAgri: Exploring potentials of ChatGPT on cross-linguistic agricultural text classification. Neurocomputing 2023, 557, 126708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koubaa, A.; Boulila, W.; Ghouti, L.; Alzahem, A.; Latif, S. Exploring ChatGPT Capabilities and Limitations: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 118698–118721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallam, M. ChatGPT Utility in Healthcare Education, Research, and Practice: Systematic Review on the Promising Perspectives and Valid Concerns. Healthcare 2023, 11, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayanouz, S.; Abdelhakim, B.A.; Benhmed, M. A smart chatbot architecture based NLP and machine learning for health care assistance. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Networking, Information Systems & Security, Marrakech, Morocco, 31 March–2 April 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Athota, L.; Shukla, V.K.; Pandey, N.; Rana, A. Chatbot for healthcare system using artificial intelligence. In Proceedings of the 2020 8th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (Trends and Future Directions) (ICRITO), Noida, India, 4–5 June 2020; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 619–622. [Google Scholar]

- Aydın, Ö. Google Bard generated literature review: Metaverse. J. AI 2023, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, C.; Adeloye, D.; Sheikh, A.; Rudan, I. Can ChatGPT draft a research article? An example of population-level vaccine effectiveness analysis. J. Glob. Health 2023, 13, 01003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotra, K.; Meincke, L.; Terwiesch, C.; Ulrich, K.T. Ideas are dimes a dozen: Large language models for idea generation in innovation. SSRN Electron. J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajja, R.; Sermet, Y.; Cwiertny, D.; Demir, I. Platform-Independent and Curriculum-Oriented Intelligent Assistant for Higher Education. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2023, 20, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Bahrini, A.; Khamoshifar, M.; Abbasimehr, H.; Riggs, R.J.; Esmaeili, M.; Majdabadkohne, R.M.; Pasehvar, M. ChatGPT: Applications, opportunities, and threats. In Proceedings of the 2023 Systems and Information Engineering Design Symposium (SIEDS), Charlottesville, VA, USA, 27–28 April 2023; IEEE: Red Hook, NY. USA, 2023; pp. 274–279. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, S. What is Google Bard? Here’s Everything You Need to Know. ZDNet. Available online: https://www.zdnet.com/article/what-is-google-bard-heres-everything-you-need-to-know (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Saeidnia, H.R. Welcome to the Gemini era: Google DeepMind and the information industry. Libr. Hi Tech. News 2023. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yllemo, H. Gemini. ALMBoK.com. Available online: https://almbok.com/google/gemini (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Kaya, C. Intelligent Environmental Control in Plant Factories: Integrating Sensors, Automation, and AI for Optimal Crop Production. Food Energy Secur. 2025, 14, e70026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariyanna, B.; Sowjanya, M. Unravelling the use of artificial intelligence in management of insect pests. Smart Agric. Technol. 2024, 8, 100517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anticimex. SMART Digital Rodent Control System for Home Business. Anticimex. Available online: https://us.anticimex.com/smart-pest-control-services/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Kamilaris, A.; Prenafeta-Boldú, F.X. Deep learning in agriculture: A survey. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 147, 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzachor, A.; Devare, M.; Richards, C.; Pypers, P.; Ghosh, A.; Koo, J.; King, B. Large language models and agricultural extension services. Nat. Food 2023, 4, 941–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayira, D.M. MSCE Agriculture, Topics and Objectives, Examination Tips, Questions and Model Answers; CHANCO Teach yourself Series; Chancellor College Publications: Zomba, Malawi, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). AGROVOC Multilingual Thesaurus. Available online: https://agrovoc.fao.org/ (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- USDA National Agricultural Library. NAL Agricultural Thesaurus (NALT)/NALT Concept Space. Available online: https://lod.nal.usda.gov/nalt/en/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Ndimbo, E.V.; Luo, Q.; Fernando, G.C.; Yang, X.; Wang, B. Leveraging Retriev-al-Augmented Generation for Swahili Language Conversation Systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, D.K.; Clay, D.E.; Kitchen, N.R. (Eds.) Precision Agriculture Basics; ASA, CSSA, and SSSA; ACSESS: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.