Abstract

Cocoa is a key tropical crop with profound environmental, social, and economic implications throughout its value chain. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has been widely employed to assess these impacts; however, most applications remain fragmented and focus primarily on environmental dimensions. This review addresses the issue related to which phases of the cocoa life cycle generate the most significant environmental impacts and how LCA methodological choices, such as the definition of system boundaries, functional units, and data sources, influence the integration of socioeconomic dimensions. A systematic literature review of 33 LCA studies published between 2008 and 2025 was conducted. The dominant categories, impact indicators, and boundary conditions were identified by applying the PRISMA methodology and cluster analysis. Results show that cultivation involves high water consumption, especially in conventional monocultures, while processing is the most energy-intensive due to machinery and transport demands. Most studies adopt cradle-to-gate system boundaries and rely heavily on secondary databases, that is, pre-existing datasets from LCA repositories like Ecoinvent or GaBi, which provide generic or averaged inventory data rather than specific measurements for each case, such as those obtained in the field of study. Overall, LCA helps identify environmental hotspots and guide decisions, but is limited by data gaps and poor integration of social and economic factors. Advancing toward comprehensive assessments requires region-specific datasets, sensitivity analyses, and hybrid frameworks, including UNEP/SETAC Social LCA guidelines, to fully integrate environmental, social, and economic dimensions of cocoa value chains.

1. Introduction

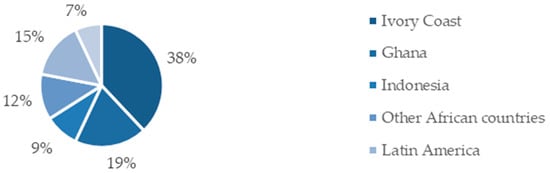

Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) is one of the most important tropical crops globally, both for its economic importance and its profound environmental and social implications. In 2022, global production reached 5.4 million tons, mainly concentrated in West Africa (Ivory Coast, 38%, Ghana, 19%), Latin America (Brazil, Ecuador, Colombia), and Southeast Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia) [1].

Figure 1 illustrates the geographical distribution of global cocoa production in 2022, highlighting the predominance of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana as the largest producers. This regional concentration has some implications for the environmental and socioeconomic impacts analyzed in this review.

Figure 1.

Geographical distribution of world cocoa production in 2022. Source: [1].

This production supports a global chocolate industry valued at $138 billion in 2023 and projected to reach $160 billion by 2028 [2]. However, this expansion comes with significant environmental and socioeconomic challenges.

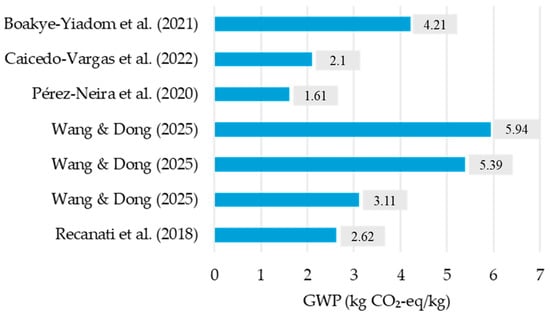

As a perennial crop, cocoa requires between 3 and 5 years to produce its first harvest, with production cycles extending for more than 25 years [3]. Its establishment and management are resource-intensive. In Ecuador, for example, conventional systems consume 0.305 m3/kg of cocoa, whereas organic systems require only 0.009 m3/kg [3]. Furthermore, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions vary considerably depending on the production system and the final product, ranging from 4.21 kg of CO2-eq/kg for milk chocolate to 1.61 kg of CO2-eq/kg for extra dark chocolate [4], and reaching 3.11 kg of CO2-eq/kg for dark chocolate [5]. Land use associated with cocoa expansion has also contributed significantly to deforestation and biodiversity loss. In West Africa, this crop has been linked to 27–67% of biodiversity loss in affected ecosystems, particularly for birds, amphibians, and vascular plants [6].

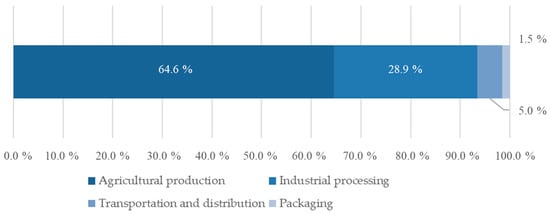

In this context, LCA has established itself as a key tool for assessing the environmental impacts of cocoa throughout its value chain. The first LCA focused on cocoa was published in 2008 [7], and since then, there has been a progressive increase in the scientific literature that applies this methodology to different phases of production and consumption. Most of these studies adopt a “cradle-to-gate” perspective and focus on agricultural and industrial phases, prioritizing indicators such as carbon footprint, water footprint, and energy demand. For example, Wang & Dong, 2025 [5] identified that the greatest global impacts occur in two stages, i.e., raw material production (64.64%) and chocolate manufacturing (28.90%). Recently, several systematic reviews and state-of-the-art analyses have explored the application of LCA in the cocoa and chocolate value chain. For example, Wang and Dong (2024 conducted a state-of-the-art analysis of LCA applications in the chocolate industry, identifying patterns and trends in the existing literature [8]. Similarly, Olarte Libreros and Muñoz Maya (2025 reviewed sustainable practices in the cocoa value chain, highlighting the connection between LCA and sustainability [9]. Another study by Cornelius et al. 2024 focused specifically on the carbon footprint of primary cocoa production through a meta-analytical review [10]. While these reviews have contributed to mapping the LCA landscape in the cocoa sector, they often focus predominantly on environmental impacts and the agricultural or processing phase, leaving a critical gap in the robust integration of social and economic dimensions.

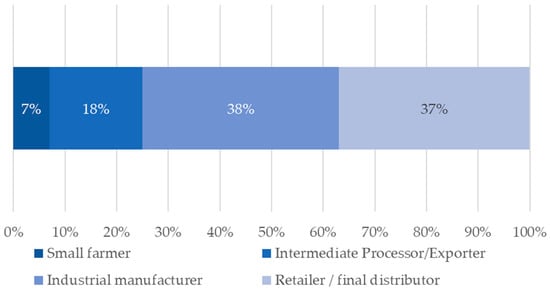

Despite their relevance to the sector, most LCAs applied to cocoa only integrate socio-economic factors in an incipient manner or not at all. It should be noted that between 80% and 90% of global production depends on smallholder farmers, who often live below the poverty line [11]. Producers receive, on average, less than 7% of the final retail price of chocolate, while most of the profits go to international processors and retailers [12].

This disconnect highlights the need for more comprehensive approaches, which is why, alongside environmental LCA, the Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) framework has emerged as a complementary tool to capture social impacts across products and value chains. Defined as the life-cycle-based method for assessing both positive and negative social effects on stakeholders such as workers, local communities, consumers, and value-chain actors, S-LCA expands sustainability assessment beyond environmental indicators. UNEP guidance establishes its four phases (goal and scope, inventory, impact assessment, and interpretation) and provides standardized subcategories, yet practitioners still face challenges of data availability, indicator relevance, and contextualization [13]. Recent developments (such as linking indicators to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and adapting frameworks for agricultural systems) highlight the potential of S-LCA to complement environmental LCA and Life Cycle Costing (LCC) within the broader Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) approach [14].

In Colombia, where cocoa is promoted as an alternative to illicit crops, socioeconomic dynamics are of particular relevance. An LCA study coupled with socioeconomic indicators showed that cocoa substitution in Putumayo has increased the income of agricultural workers, whereas it has reduced it in Catatumbo, due to differences in local market conditions and the profitability of coca [15]. Similarly, the adoption of agroforestry and organic systems offers long-term ecological and economic benefits, such as a 57.3% reduction in global warming potential and an 87.4% reduction in terrestrial ecotoxicity [16], but entails higher initial costs and lower short-term yields, which limit its adoption by vulnerable farmers [3].

In this context, this article critically reviews LCA applications in the cocoa value chain. Unlike previous reviews, which focus almost exclusively on environmental impacts or isolated life-cycle stages, our work goes further: it identifies the main environmental hotspots while systematically analyzing how methodological choices (system boundaries, functional units, and data sources) have limited the inclusion of social and economic dimensions. Despite the rapid growth in cocoa LCA literature, four key research gaps remain:

- Scarce integration of social and socioeconomic aspects in a sector where 80–90% of production depends on smallholders living in poverty.

- Narrow and geographically biased scopes, predominantly cradle-to-farm gate and centered on West Africa.

- Lack of truly integrated frameworks that simultaneously assess environmental, social, and economic performance under consistent boundaries.

- Heavy reliance on generic secondary databases reduces accuracy, comparability, and relevance to local contexts.

Its central question is: Which phases of the cocoa life cycle generate the most significant environmental impacts, and how can LCA frameworks be strengthened to robustly include socioeconomic and environmental dimensions? The specific objectives of this review are as follows:

- Methodological approaches, contextual conditions, and categories used in cocoa LCAs were analyzed.

- Identifying environmental hotspots and key methodological and data challenges

- To highlight the role of socioeconomic aspects in sustainable cocoa production and propose directions for a more integrated sustainability assessment.

This review addresses a critical research gap in the current literature, as most LCA applications in the cocoa sector remain fragmented and primarily focused on environmental indicators, overlooking social and economic aspects. Therefore, this study seeks to answer the following key question: Which phases of the cocoa life cycle generate the most significant environmental impacts, and how can LCA frameworks be strengthened to integrate environmental, social, and economic dimensions? By addressing this question, the review contributes to advancing comprehensive sustainability assessments in the cocoa value chain. The remainder of this manuscript is organised as follows: Section 2 describes the materials and methods applied, including the PRISMA approach and ISO-based methodological framework. Section 3 presents the main results related to environmental, social, and economic aspects. Section 4 discusses key findings and methodological implications, while Section 5 summarises the study’s limitations. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 present the key findings, contributions, and conclusions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review and the PRISMA Methodology

To ensure a rigorous and systematic approach, the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology was adopted, widely recognized in scientific literature for its ability to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and bias reduction in systematic reviews [17]. This strategy allowed us to identify, filter, and evaluate relevant studies that applied LCA to cocoa and chocolate-derived products.

The Scopus database was selected for its broad interdisciplinary coverage and reliability in peer-reviewed literature. The keywords and boolean operators were as follows: “LCA” OR “Life Cycle Assessment” AND “Cacao” OR “cocoa” OR “Theobroma” OR “Chocolate.” No restrictions on the year of publication were established to encompass the methodological evolution of the studies. The search process retrieved 67 documents published between 2008 and 2025. However, the temporal distribution of the publications shows a gradual increase in recent years, with notable growth in 2022 (9 articles), 2023 (7 articles), and 2024 (15 articles), reflecting the growing academic interest in cocoa sustainability assessments.

2.2. Data Extraction and Visualization

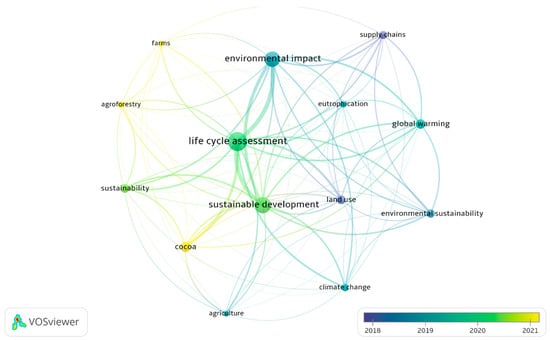

VOSviewer 1.6.20 is a bibliometric analysis tool that facilitates the identification of thematic trends through co-occurrence networks.

Key terms were grouped into clusters related to

- Environmental impact categories

- System boundaries and functional units (FUs)

- Dimensions of sustainability linked to sustainability.

The information was systematized in a database that included: authorship, year of publication, region of study, type of productive system analyzed, system boundaries, functional units, impact categories evaluated, databases and software used, and the inclusion or absence of socioeconomic indicators. This approach allowed for cross-sectional comparisons and methodological and geographic gap identification (please see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Terms used in the identified references on LCA studies in the cocoa supply chain. Source: Authors.

2.3. Selection and Eligibility Criteria

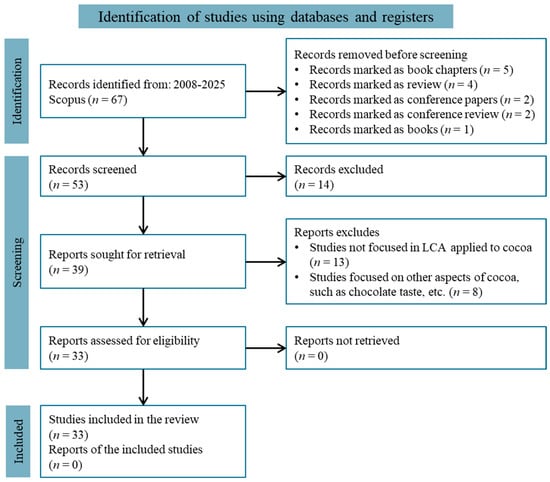

Study selection was structured in three phases (Figure 3), following the PRISMA workflow:

Figure 3.

Reference selection process under the PRISMA methodology. Source: Authors.

1. Identification: Initial records were collected using Scopus (n = 67), chosen for its extensive coverage of high-quality, peer-reviewed journals in the fields of environmental science and engineering.

2. Selection: Titles and abstracts were screened according to the following predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria:

- Focus on at least one stage of the cocoa supply chain. This criterion ensures that the selected literature is directly relevant to the specific product system under review, from cultivation to consumption.

- Explicit or implicit use of the LCA methodologies. This ensures the study employs the standardized framework of LCA (ISO 14040/14044) [18,19], whether as a core method or as part of an integrated assessment (e.g., LCSA), maintaining methodological consistency across the review.

- Emerging socioeconomic dimensions of sustainability. This allows for the inclusion of studies that incorporate social life cycle assessment (S-LCA) or life cycle costing (LCC), aligning with the paper’s goal of exploring trends beyond purely environmental impacts.

Exclusion criteria:

- Non-peer-reviewed documents. Excluding thesis, conference papers, or reports, to maintain scientific rigor and comparability between studies

- Studies without reference to cocoa. To exclude irrelevant literature and focus the analysis on the defined scope.

- Mentioning the LCA conceptually without applying it, as these lack primary or comparative data necessary for methodological analysis.

3. Inclusion: After the filtering, 33 studies that met the methodological relevance were retained.

2.4. ISO Standards in Life Cycle Analysis Studies

Since LCA is an internationally standardized methodology, the degree of alignment of the studies with ISO 14040:2006 (confirmed in 2022) and ISO 14044:2006 (confirmed in 2021) standards was assessed. These provide the methodological framework and define the following four key phases:

- Definition of the objective and scope of the study

- Life-cycle inventory analysis

- Assessment of life cycle impact

- Interpretation of the results

The incorporation of these methodological considerations into the review ensured that the synthesis of the selected results was based on quality and consistency parameters defined by ISO standards and not limited to a descriptive inventory. The extracted information was organized according to a common analysis framework (publication, methodological attributes, impact categories, and socioeconomic dimensions) to guarantee the traceability and consistency of subsequent results. Table 1 summarises the ISO 14040/14044 methodological criteria applied to assess the consistency and quality of cocoa LCA studies, serving as a benchmark for comparison

Table 1.

Methodological criteria derived from ISO 14040/14044 standards applied in the selection and analysis of cocoa LCA studies. Source: Authors based on ISO 14040/14044 and systematic review.

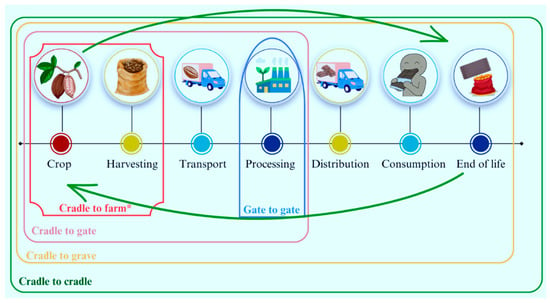

Figure 4 illustrates the system boundaries commonly adopted in cocoa LCAs, in line with ISO 14040/14044 standards. This diagram helps to contextualize which phases of the value chain are typically included in the analyses and highlights the methodological scope underlying the reviewed studies. The cocoa life cycle comprises several interrelated stages, beginning with cultivation and harvesting, followed by fermentation and drying, processing into intermediate products such as liquor, butter, and powder, and finally chocolate manufacturing, packaging, distribution, and end-of-life management. These stages collectively determine the environmental and socioeconomic impacts assessed in LCA studies.

Figure 4.

Cocoa life cycle contour boundary diagram. Source: Authors. * In some studies, harvesting is included in the agronomic or “cradle” stage of the process.

2.5. Data Synthesis

Finally, the studies were organized into a comparative database (Table 2), which classified the methodological attributes and key results. This structured synthesis allowed for the identification of patterns of consistency and critical gaps in the literature, laying the groundwork for a cross-sectional analysis geared toward the construction of hybrid frameworks, such as LCSA. Thus, the methodology was not limited to a descriptive inventory but incorporated the necessary quality and consistency parameters.

Table 2.

Characterization of LCA studies on cocoa and chocolate. Source: Authors.

2.6. Conceptual Framework LCA, LCC, S-LCA and LCSA

This review is grounded in the family of Life Cycle Approaches (LCA framework), which assesses sustainability across environmental, economic and social dimensions. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) quantifies environmental impacts throughout a product’s life cycle following ISO 14040 and 14044 standards. Life cycle costing (LCC) evaluates the economic costs associated with all stages of the life cycle, complementing LCA by considering financial performance and feasibility. Social Life Cycle Assessment (S-LCA) focuses on social and socioeconomic impacts, assessing effects on workers, communities, and consumers, based on UNEP/SETAC guidelines.

Together, these methods from the Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) framework, which seeks to integrate environmental, economic and social indicators into a unified sustainability perspective, enable more comprehensive decision-making in the cocoa value chain.

3. Results

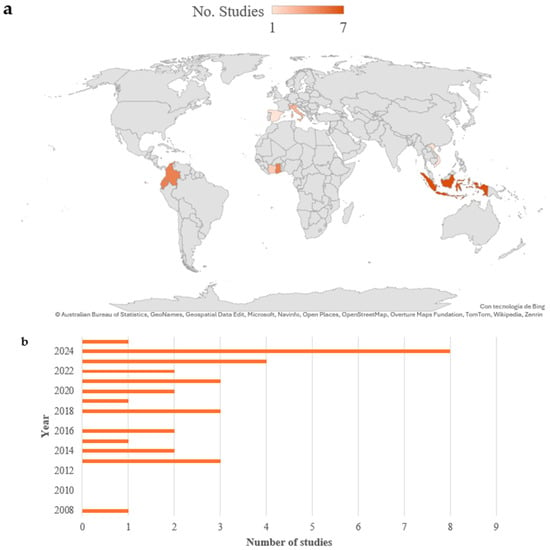

This section presents the main findings derived from the systematic review of 33 Cocoa Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) studies. Results are structured around environmental, social, and economic dimensions, as well as methodological aspects such as sensitivity and uncertainty analysis. These findings provide the empirical basis for the discussion presented in Section 4. The geographical and temporal distribution of the studies is shown in Figure 5. Spatially, the main case studies are largely concentrated in the main producing countries: Indonesia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Ghana. In contrast, European countries (Italy, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom) predominate in methodological developments and comparative analyses. Temporally, publications were scarce until 2018, followed by a significant increase that peaked in 2024, reflecting growing scientific interest in the environmental assessment of cocoa value chains.

Figure 5.

Geographical distribution and temporal trend of the 33 reviewed cocoa LCA studies (2008–2025). (a) Map showing the number of studies per country (the color is proportional to the number of studies, with darker colors indicating a higher number of studies and lighter colors indicating a lower number of studies). (b) Histogram of publications per year. Source: Authors.

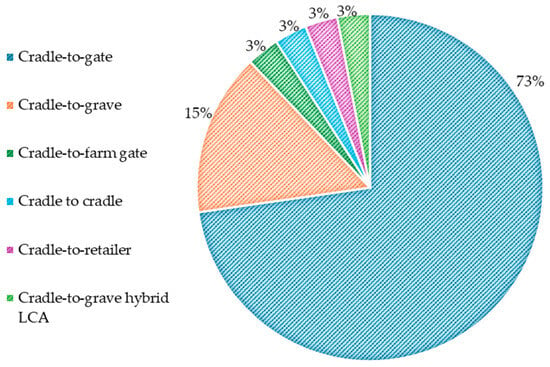

A critical analysis of the system boundaries adopted (see Figure 6) indicates a dominant preference for a “cradle-to-gate” approach (73% of studies), while only 15% adopt a comprehensive “cradle-to-grave” perspective. The remaining 12% of studies used partial or non-standard boundaries. This heterogeneity highlights significant methodological fragmentation that inherently limits the comparability of results across studies.

Figure 6.

Distribution of system boundaries in 33 reviewed cocoa LCA studies. Source: Authors.

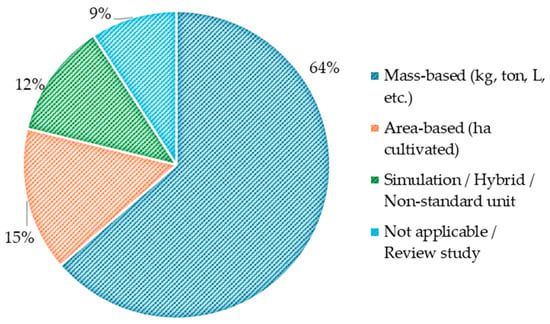

Furthermore, the selection of functional units (see Figure 7) varies considerably. Most assessments are based on mass (e.g., 1 kg of beans or chocolate), accounting for approximately 64% of studies, followed by area-based units (15%). This predominance of mass-based units reflects the field’s emphasis on comparing impact at the product level, often to the detriment of assessing land use efficiency or socio-economic performance, which are key to the transition to comprehensive Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) frameworks.

Figure 7.

Distribution of functional units used in 33 reviewed cocoa LCA studies. Most assessments adopt mass-based units (≈64%), followed by area-based (15%), hybrid or simulation-based units (12%), and non-applicable cases such as methodological reviews (9%). Source: Authors.

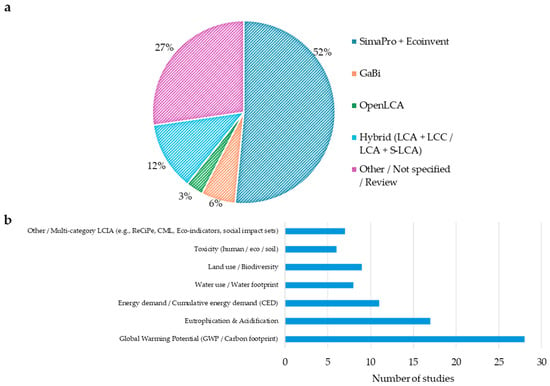

Finally, analysis of impact categories and software tools (Figure 8) reveals a strong bias. Global Warming Potential (GWP) is assessed in nearly 85% of studies, while other categories, such as eutrophication (51%) and energy demand (33%), are less common. Tools such as SimaPro with the Ecoinvent database predominate (52% of studies), with limited application of hybrid frameworks that integrate social or economic dimensions. This predominance of climate-focused assessments suggests that critical environmental issues, such as biodiversity loss and toxicity, remain underexplored in the cocoa sector.

Figure 8.

Overview of impact categories (a) and LCIA methods (b) group or category of impact evaluated by studies vs. the number of studies reviewed. Source: Authors.

3.1. Environmental Impacts on Cocoa LCA

The reviewed studies agree that the main environmental impacts are concentrated in three critical phases: agricultural production, industrial processing, and transportation [16]. Across these phases, differences in management practices, energy sources, and product formulation largely determine the environmental performance of cocoa and chocolate products.

In the agricultural phase, the use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides is the main determinant of GHG emissions, eutrophication, and soil acidification. Ntiamoah & Afrane [7] reported that nitrogen fertilizers can represent up to 60% of total GHG emissions in cocoa plantations in Ghana. Comparative studies have shown that organic and fairtrade production reduces CO2 emissions by 57% and terrestrial ecotoxicity by 87% compared with conventional production in Côte d’Ivoire [16]. However, these certified systems often require a larger cultivated area, which in turn places additional pressure on land use and biodiversity.

Agricultural energy consumption also varies with the production system. In Ecuador, intensive systems achieve 3.27 MJ/kg of cocoa, whereas organic agroforestry systems only require 0.36 MJ/kg. In terms of water, conventional systems require 0.305 m3/kg cocoa, compared to 0.009 m3/kg in organic systems, due to a lower dependence on irrigation [3]. However, in agroforestry systems with high root density, competition for water can arise during drought periods [46].

In the postharvest phase, processes such as fermentation and drying are critical in terms of energy. In Colombia and other producing countries, traditional drying with electric or gas ovens requires high energy consumption, whereas solar technologies have been shown to reduce the energy and climate impact of processing byproducts such as cocoa hulls by up to 63% [39]. This type of innovation is essential for moving toward cleaner production systems that are compatible with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

At the industrial processing stage, operations such as grinding, pressing, and milling require high electricity and fossil fuel consumption. In Indonesia, dark chocolate processing recorded a consumption of up to 421.9 kWh per ton of dark chocolate, positioning electricity as the most determining input in the carbon footprint [35]. The significant impact of multi-layer packaging materials (aluminum and cardboard), which constitute the second emission factor after transportation, is also observed.

International transport also has a significant impact due to the distance between producing countries and consumer markets in Europe and North America. Maritime transport and refrigerated storage significantly increase cocoa and chocolate’s carbon footprint [16].

Environmental impacts vary depending on the type of chocolate used. Dark chocolate has better environmental performance (3.11 kg CO2-eq/kg), while milk chocolate (5.39 kg CO2-eq/kg) and white chocolate (5.94 kg CO2-eq/kg) show higher impacts, i.e., due to the incorporation of milk powder and greater use of additional ingredients [5,32]. In terms of eutrophication, dark chocolate accounted for (0.0029 kg PO4-eq/kg), compared to (0.013 kg PO4-eq/kg) for milk chocolate.

Overall, the results show that the agricultural and industrial phases account for most environmental impacts in the cocoa value chain, modulated by the type of product and the adopted production system, as is illustrated in Figure 9. It is also important to note that most reviewed studies adopt cradle-to-gate system boundaries, which exclude the consumption and end-of-life stages. This restriction limits the capacity to fully assess downstream impacts such as packaging waste, product disposal, and post-consumer transport.

Figure 9.

Relative contribution of cocoa life cycle stages. Source: Authors.

A comparison of GWP values reported across the reviewed cocoa LCA studies is presented in Figure 10. Emissions range from 1.6 kg CO2-eq per kg of product in agroforestry-based dark chocolate [27] to 5.9 kg CO2-eq/kg in white chocolate [5]. Conventional and industrial systems consistently exhibit higher footprints than agroforestry or organic alternatives, with milk and white chocolate showing marked increases due to dairy ingredients. This broad variability stems from both on-farm drivers, likewise fertilizer intensity, energy sources, and processing efficiency and methodological choices, including system boundaries, data provenance, and the underlying energy mix.

Figure 10.

Variation in Global Warming Potential (GWP) values reported across cocoa LCA studies (kg CO2-eq per kg of product). Source: Authors. References mentioned in figure [3,4,5,27,29].

Variations in environmental performance underscore the importance of contextual and management factors in sustainability outcomes. That is why Section 3.2 examines how production systems, environmental conditions, and resource management practices influence the magnitude and distribution of impacts throughout the cocoa value chain.

3.2. Environmental Conditions and Production Systems

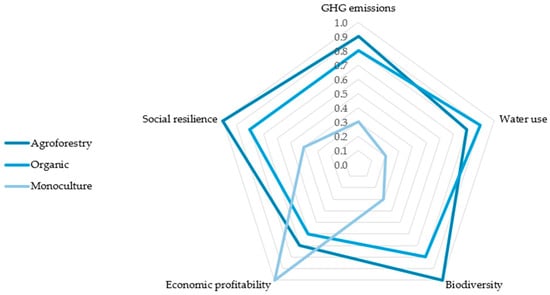

The environmental, social, and economic performance of cocoa is heavily dependent on production systems. Intensive monocultures, which are prevalent in West Africa and parts of Asia, generate high short-term yields but negatively impact deforestation, biodiversity loss, soil degradation, and water pollution. Furthermore, the high dependence on agrochemicals increases GHG emissions and poses risks to human health [32]. In contrast, agroforestry and intercropping systems demonstrate greater sustainability. In Indonesia, ref [44] reported that by diversifying income and strengthening food security, integrating cocoa with other food crops increased profitability by up to 205% and improved social indicators by 23.7%. However, in certain contexts, the complexity of managing these systems can increase input use and associated emissions, necessitating careful management [46].

Furthermore, agroforestry systems contribute to carbon sequestration, climate resilience, and biodiversity conservation. Their lower relative yield compared with monocultures is offset by broader ecosystem benefits. The circular economy is another crucial element that seeks to leverage byproducts and waste from the cocoa value chain to reduce the environmental footprint. In Colombia, it was estimated that more than 559,000 tons of cocoa husks were generated in 2022, usually abandoned in the fields, producing methane and nitrogen oxide emissions [39]. Utilizing this biomass for activated carbon, potassium hydroxide, and cellulose can reduce environmental impacts and offer market potential in chemicals, food, and energy industries [5,23].

Overall, the comparison between monoculture, agroforestry, and circular approaches reveals a spectrum of trade-offs between yield intensity, ecosystem integrity, and social benefits. Figure 11 illustrates these performance contrasts across environmental, economic, and social dimensions, highlighting how integrated production systems contribute more holistically to sustainability outcomes. These patterns set the stage for the following sections, which examine the socioeconomic implications of cocoa life cycle assessments. Future assessments should develop regionally adapted models capable of representing local management practices, technological capacity, and socioeconomic conditions to enhance cross-system comparability.

Figure 11.

Comparative sustainability performance of cocoa production systems (1 = best performance, 0 = worst performance). Source: Authors.

3.3. Social and Economic Aspects of Cocoa LCA

Although most LCA studies focus on environmental impacts, increasing attention has been given to social and economic dimensions, especially through the study S-LCA.

In Colombia, Luna Ostos et al. conducted one of the few full S-LCA applications in the chocolate industry. This study assessed the Luker Chocolate supply chain, covering both the upstream (coca farming) and downstream (processing) stages [38]. Following the UNEP/SETAC guidelines, the analysis included 16 social subcategories across stakeholders (workers, local communities, and society), using qualitative reference scales from −2 (severe negative) to +2 (strong positive). Primary data were collected through semi-structured interviews, CSR reports (Corporate Social Responsibility), and field visits, complemented with the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB). Results indicated positive social performance associated with local employment, gender inclusion, and child labor prevention programs in post-conflict regions, positioning the company as a case of socially responsible value-chain management in Latin America.

In contrast, Vinci et al. applied a quantitative, risk-based S-LCA using the PSILCA database (Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment) to analyze cocoa production in the Ivory Coast and Ghana [45]. Instead of quantitative scoring, this method assigns social risks (very low to very high) based on country indicators derived from international sources, such as the ILO (International Labour Organization), UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), and the World Bank. The study revealed that more than half of the global cocoa supply originates from high-risk contexts, particularly in terms of child labor, freedom of association, and wage inequality. This approach not only emphasizes the relevance of global databases for large-scale assessments but also highlights limitations in data resolution and local specificity.

Tovar et al. combined environmental LCA with a simplified LCC to assess the valorization of cocoa pod husks, a major agricultural residue in Colombia [39]. Three transformation pathways (activated carbon, cellulose, and KOH-based activation) were compared considering production costs and environmental burdens. The combined assessment identified KOH (Potassium Hydroxide) activation as the most cost-effective and environmentally favorable alternative.

Figure 12 illustrates the typical distribution of the final price of chocolate among actors in the value chain, confirming the structural asymmetry mentioned in the literature [12]. Small farmers receive only 7% of the consumer price, while processors, manufacturers, and retailers collectively capture more than 90% of the value. This disparity underscores the urgency of integrating economic assessments such as the LCC within sustainability frameworks to identify and address inequalities in the distribution of benefits.

Figure 12.

Percentage distribution of the final price of chocolate among the actors in the value chain. Source: Adapted from Fountain & Hütz-Adams [12].

Similarly, Rahmah et al. developed a hybrid LCSA model integrating LCA, LCC, and S-LCA through a multi-criteria decision-making framework (AHP-TOPSIS) to evaluate cocoa farming systems in Indonesia [44]. According to expert consultation, environmental, economic, and social indicators were normalized to a 0–1 scale and weighted (40% environmental, 35% social, 25% economic). Aggregated index demonstrated that intercropping systems achieved superior sustainability performance compared with monocropping, mainly due to higher resource efficiency and community-level economic benefits. This model exemplifies a more advanced integration of the three-sustainability pillar through normalization and weighting, offering a quantitative foundation for agriculture management decision-making.

Collectively, these studies represent a shift from isolated LCA analyses to a more comprehensive LCSA perspective, incorporating social and economic dimensions alongside environmental performance. While Luna Ostos et al. and Vinci et al. applied parallel integration (evaluating social and environmental impacts separately but interpreting them together) [41,45], Tovar et al. introduced comparative (cost-impact) integration [39], and Rahmah et al. achieved hybrid integration through composite indicators [44].

This diversity of methodological depth underscores the ongoing transition of cocoa sustainability research: from descriptive assessments to quantified, decision-oriented models that support sustainable value chain development. Nonetheless, the reviewed boundaries and weighting criteria hinder the comparability and scalability of results across contexts. Advancing toward a unified LCSA framework, as proposed by Herrera Almanza et al., will be essential to align environmental, social, and economic metrics and enable consistent sustainability benchmarking within the cocoa sector [14].

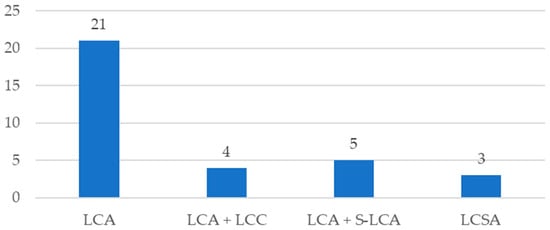

Figure 13 illustrates the distribution of the 33 reviewed studies according to the sustainability dimensions incorporated. It shows that most studies (21) focus exclusively on environmental aspects (traditional LCA), while a smaller number integrate economic (4) or social (5) dimensions. Only 3 studies adopt a fully hybrid approach (LCSA), reflecting the methodological gap identified in the literature.

Figure 13.

Distribution of the 33 reviewed cocoa LCA studies according to the incorporated sustainability dimensions. Source: Authors.

3.4. Limitations in Cocoa Life Cycle Analysis Modeling

Despite methodological advances, cocoa LCA studies present significant challenges and limitations that can hinder the interpretation of results and comparability across studies. The first limitation is the availability and quality of up-to-date data [5]. Most studies are based on secondary data, with little primary information collected in the field, especially during the agricultural phase. This makes it difficult to capture the heterogeneity of agricultural practices across countries and regions, as well as their inherent variability due to climatic and cultural factors.

The second limitation is the complexity of the perennial agricultural systems. Cocoa is a long-term crop with production cycles that can exceed 25 years. This poses challenges in defining appropriate time limits for inventory analysis and hampers the application and development of standardized LCA models [32,34].

The third limitation is the comparability between production systems. Differences in geographic, technological, and socioeconomic context make it difficult to establish homogeneous assessments between conventional, organic, and agroforestry cocoa. For example, environmental pressure is mainly associated with deforestation and water consumption in West Africa, whereas the focus is on the use of agrochemicals and the valorization of by-products in Latin America [39]. At the social level, the application of S-LCA also faces a lack of reference scales adapted to specific contexts of conflict and poverty, limiting the results’ validation and comparability [41].

A fourth limitation involves the need that still remains to move towards hybrid and multi-criteria models. Combining LCA with Input-Output Analysis (IOA) and Multi-criteria Decision Making (MCDM) would allow for a more comprehensive integration of environmental, social, and economic aspects. This type of methodology has already been applied in the Indonesian cocoa sector, demonstrating its potential to identify more sustainable production opportunities [5,44].

Finally, the validation and scalability of current models remain limited. Few studies have performed sensitivity or uncertainty analyses, and ever fewer have compared model predictions against empirical production data. Enhancing the consistency between model assumptions and real-world performance is essential to strengthening the credibility of LCA-derived recommendations.

Given the above, it can be concluded that although LCA has proven to be a key tool for identifying critical points in value chains and for designing mitigation strategies, its broader usefulness depends on overcoming data and methodological fragmentation, advancing the integration of the social dimensions, and strengthening empirical validation under real production conditions [7].

The characterization of the reviewed studies also included the identification of the data sources and databases employed in each case, which constitute the foundation for the methodological discussion presented in Section 4.1. As summarized in Table 2, most cocoa-related LCAs relied predominantly on secondary databases, particularly Ecoinvent, GaBi, and Agrifootprint, while only a limited number incorporated primary field data collected directly from farms or processing facilities. This distribution highlights a persistent dependency on generic datasets, which affects the representativeness and comparability of the results across geographic contexts. These findings are further analyzed in the Discussion section to examine their implications for data quality, methodological consistency, and the reliability of sustainability assessments in cocoa value chains.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the literature on LCA of cacao to assess its contribution to agricultural scientific knowledge and decision-making. A comparative analysis of existing publications was conducted, focusing on key aspects of the cacao life cycle. The initial findings revealed that the cultivation phase presents high water consumption, mainly due to irrigation practices, while the processing phase is the most energy-intensive, largely attributable to transportation and machinery. Subsequent analysis of the literature’s LCA boundary conditions demonstrated a predominant focus on an integrated approach. Common input and output parameters were identified along with potential limitations encountered in conducting such studies. These findings form the basis of the subsequent discussion.

4.1. Sources of Information

The literature review confirms that data availability and quality are one of the main bottlenecks for cocoa LCA. In most of the reviewed studies, inventories depend on secondary databases, such as Ecoinvent, GaBi, or Agrifootprint, which introduce biases by not reflecting the particularities of each productive context [7,36]. This reliance on secondary datasets reduces the ability to capture the heterogeneity of regional production systems and may introduce systematic biases that affect the comparability of results across different geographical contexts. In contrast, studies based on primary data, for example, the survey of 90 farms in the Ecuadorian Amazon, offer more representative results, capturing differences between conventional and organic systems in terms of water and carbon footprint [3].

The integration of primary and secondary sources through hybrid frameworks is a promising avenue. Recent studies on the cocoa value chain in the UK and global markets have shown that hybrid models (LCA + LCC + MCDM) allow for the simultaneous assessment of environmental and economic indicators, improving decision-making relevance [5,47]. This approach is particularly relevant for agro-industrial chains, such as the cocoa chain, where asymmetries in value distribution limit farmers’ ability to adopt more sustainable practices.

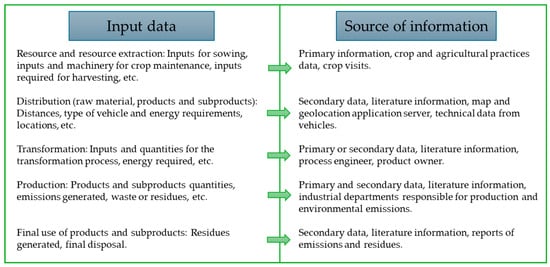

Figure 14 outlines the main sources of information used in cocoa LCAs, highlighting the predominance of secondary databases and the limited incorporation of primary data, which directly affects the representativeness and reliability of results.

Figure 14.

Information sources for data required in LCA studies involving the processing of agricultural raw materials. Source: Authors.

4.2. Critical Impacts and Variability of Production Systems

Due to the intensive use of synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, the agricultural phase remains the main critical point, responsible for between 50% and 60% of GHG emissions in conventional plantations [7]. Full-sun monocultures stand out for their larger water footprint and contribution to deforestation, while agroforestry and organic systems show lower emissions and better ecosystem performance, although with lower initial yields [16,33].

From an efficiency perspective, the results also show contrasts. In Indonesia, the energy consumption of intensive systems is up to 3.27 MJ/kg of cocoa, compared to 0.36 MJ/kg in organic agroforestry systems [25,44]. This trend coincides with findings in Ecuador, where organic production reduced water consumption from 0.305 to 0.009 m3/kg [3]. However, landscape studies indicate that benefits at the farm level can be reversed at the territorial scale if agroforestry expansion displaces conservation areas [34].

Industrial processing and packaging are the second sources of impact. Research in Indonesia and Europe highlights that the electricity used in grinding and milling, along with multi-layer aluminum and cardboard packaging, accounts for up to 30% of the carbon footprint of certain chocolates [32,35]. These findings are consistent with those reported in the United Kingdom, where the packaging type can modify the GWP of the final product by up to 19% [47].

Finally, international transport is a key determinant, especially in chains oriented towards Europe and North America. Although maritime logistics are relatively efficient, long distances and refrigeration substantially increase the total environmental footprint [16].

4.3. Global Perspective and Challenges

Beyond environmental considerations, cocoa production is characterized by profound social and economic challenges that are not adequately reflected in traditional life-cycle analyses. The long ripening period for cocoa trees (three to five years before the first harvest) constitutes a significant financial burden for farmers, who must invest in inputs and labor without immediate profitability prospects. This structural lag increases economic vulnerability and frequently forces small producers into debt or dependence on intermediaries. Furthermore, the asymmetric distribution of value within the cocoa chain represents a persistent structural inequity: while farmers receive only a marginal fraction of the final market price of chocolate, the majority of the profits are concentrated among processors, traders, and retailers at later stages.

Environmental pressures associated with global commodity production exacerbate these dynamics. For example, Scherer & Pfister [48] analyzed the environmental impacts of food exports and imports in relation to water consumption, phosphorus emissions, and biodiversity loss, identifying major producing countries, such as Ecuador, Colombia, Spain, Ghana, and Italy, as disproportionately affected. This is largely due to the intensive cultivation of high-demand commodities, such as cocoa, coffee, sunflowers, grapes, and olives, which exert considerable pressure on natural systems.

Given cocoa’s perennial nature, future LCAs should adopt dynamic or time-dependent modelling approaches to better capture temporal variations in environmental impacts across multiple harvest cycles. Current life cycle assessment databases offer limited information specific to cocoa cultivation, limiting the analytical robustness of existing studies [27]. These methodological limitations are intrinsically linked to socioeconomic challenges: while late returns require a substantial initial investment for farmers, income from subsequent harvests remains markedly disproportionate to the profits accrued at later stages of the cocoa value chain. Developing region-specific LCA datasets is crucial for reflecting local environmental pressures and supporting the design of context-sensitive sustainability interventions

4.4. Decision-Making

While LCA has proven valuable in guiding environmental sustainability decisions and strategies, its scope remains limited when social and economic dimensions are excluded. Several authors have argued that sustainable production and consumption require a holistic LCA framework that integrates current production impacts, long-term sustainability trajectories, and potential environmental risks [49]. Such integration strengthens decision-making at the most pronounced stages of environmental burden, namely, agricultural production and initial processing. This approach facilitates robust decision-making at the agricultural production and initial processing stages, where the most significant environmental impacts occur. Agroforestry systems, for example, despite producing less per hectare, provide substantial benefits in carbon sequestration and biodiversity conservation [36]. Similarly, improvements in energy efficiency and the adoption of renewable energy sources in processing facilities can significantly reduce the carbon footprint of chocolate production [32]. The methodological recommendations discussed above can be translated into practice through concrete policy and management instruments. For instance, national LCA databases and certification programmes could provide locally adapted sustainability benchmarks, while circular economy initiatives may promote by-product valorisation at the farm and industry levels. Integrating these tools into agricultural and environmental policy frameworks would enhance the practical applicability of LCA findings and strengthen their contribution to sustainable cocoa production.

The methodological complexity of LCAs also requires strategies to address uncertainty. Sensitivity analysis is a crucial tool for refining model inputs, reducing variability, and improving the reliability of results. In this regard, a comprehensive modeling framework was developed to assess biodiversity impacts associated with the cocoa trade [21], introducing two complementary approaches: The first, Convergent Stress Value Analysis (CSVA), is a variance-based sensitivity measure that evaluates how results converge when model parameters are stressed across different ranges, thereby testing the stability and robustness of outcomes under uncertainty. Second, Extreme Model Evaluation Trajectories (EMET) explore system behavior under boundary conditions by simulating scenarios where parameters adopt extreme values, thus identifying potential worst-case outcomes and the resilience of model predictions, which examine system behavior under extreme parameter combinations. By combining these methods with existing LCA databases, the study quantified land-use requirements and projected biodiversity loss in major cocoa-producing regions [21]. The results highlighted significant geographic variation: while India exhibited a 92% probability of biodiversity loss due to land conversion for cocoa cultivation, Brazil’s Atlantic coast showed the lowest probability, at 30%.

4.5. Critical Reflections and Future Research

A key limitation of current cocoa LCAs is their persistent reduction of sustainability to environmental performance, often overlooking the systemic inequalities and power dynamics that shape cocoa production. Without explicitly addressing the socioeconomic vulnerabilities of smallholder farmers, LCAs risk legitimizing sustainability strategies that, while they might be environmentally sound, are socially inequitable [45]. For cocoa-producing regions, the integration of social metrics (e.g., income distribution, labor conditions, and community resilience) into LCA frameworks is essential to align sustainability research with SDGs, particularly those related to poverty reduction (SDG 1), decent work (SDG 8), and responsible consumption and production (SDG 12). From a practical perspective, true sustainability in cocoa will only be possible if governments, industry, and farmers stop acting separately and make governance truly comprehensive. That is why we invite governments to take the lead in creating contextualised life cycle databases and national LCA inventories that reflect our cocoa reality; this will enable them to design standards, green bonds, and climate policies that really work. We recommend that industry and certifiers integrate social and economic indicators so that value is distributed fairly and small producers are no longer left at the bottom of the economic system [50]. And we provide farmers and cooperatives with these results as a roadmap: optimise fertilisers, commit to agroforestry and the circular economy, because every kilo of reduced carbon translates into resilience and economic recovery, thanks to new potential markets.

Despite significant methodological advances, S-LCA and LCC applications in cocoa studies remain fragmented. Most assessments rely on qualitative or secondary data, limiting representativeness and comparability. Differences in system boundaries, indicator definitions, and data quality constrain the integration of environmental findings with social and economic dimensions. Future research should prioritize data harmonization, stakeholder-based indicator design, and the formal adoption of hybrid methodologies that integrate LCA, LCC, and S-LCA within a unified LCSA framework, as promoted by UNEP. This would enable more comprehensive analyses of socio-environmental trade-offs and support informed, equitable decision-making across the cocoa value chain.

The subjectivity of weighting and aggregation methods in current LCSA applications is another major challenge. Most studies rely on expert judgment or stakeholder input, which introduces bias and limits reproducibility. Developing standardized weighting matrices linked to key sectoral priorities such as deforestation, labor conditions, and farm income distribution would enhance transparency and comparability. Furthermore, MCDM approaches should be expanded to capture complex tradeoffs between sustainability dimensions, enabling context-sensitive and socially just evaluations.

The review also identifies a methodological gap in sensitivity and uncertainty analysis, although parametric and scenario-based approaches are increasingly being applied, comprehensive uncertainty quantification through Monte Carlo simulation, stochastic modeling, or global sensitivity analysis remains rare. Most studies treat uncertainty qualitatively or restrict it to specific inventory parameters, neglecting its propagation through impact assessment and interpretation stages.

Therefore, future cocoa LCSA applications should incorporate systematic uncertainty assessment across all three sustainability pillars.

Moving forward, future research should prioritize:

- Development of region- and production-system-specific life-cycle inventories that capture the heterogeneity of agricultural practices and socioeconomic contexts, thereby reducing extrapolation errors.

- Formal integration of hybrid LCA, LCC, and S-LCA methodologies under the LCSA framework to enable holistic three-dimensional evaluation.

- A deeper analysis of power dynamics and value distribution along the cocoa chain through multi-criteria frameworks that balance environmental integrity with social and economic viability, especially for small producers, is required.

- LCA can fully realize its potential as a decision-support tool for advancing genuinely sustainable and equitable cocoa value chains through this integrative and contextualized approach.

Future LCA applications in the cocoa sector should consistently integrate quantitative uncertainty analysis—such as Monte Carlo simulation or global sensitivity testing—to ensure robustness and transparency of results.

5. Limitations of the Study

This systematic review has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results and conclusions. First, a potential bias stems from the database used, as the literature search was conducted exclusively in Scopus [8]. This may have excluded relevant studies indexed in other databases, such as Web of Science, PubMed, or Agricola, as well as gray literature from technical reports, theses, or institutional documents from non-academic organizations.

Second, the language criteria were not explicitly defined, which may have restricted the inclusion of studies published in languages other than English, especially in cocoa-producing countries where research is reported in Spanish, French, or Portuguese [4].

Another limitation is related to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, which focus on studies that specifically apply LCA, S-LCA, or LCC methodologies. Although this approach ensures methodological rigor, it may have overlooked relevant research on cocoa sustainability that addresses socioeconomic or environmental dimensions using other analytical frameworks.

Although studies from different cocoa-producing regions were included in terms of geographic and temporal representativeness, the distribution was not equitable. A greater concentration of research was observed in Indonesia and Colombia, while West Africa, outside Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire, was underrepresented. Furthermore, although the time frame covers studies published or accepted up to 2025, the availability of very recent work may be limited, affecting certain new findings [51].

Finally, due to the lack of consolidated standards in indicators, reference scales, and aggregation methods, the methodological variability observed in the applications of S-LCA and LCC makes it difficult to compare studies. This lack of harmonization restricts the possibility of carrying out a comprehensive and comparative assessment of the social and economic dimensions within the LCSA frameworks [52].

6. Key Findings and Contributions

This systematic review reveals a methodological shift in cocoa sector studies, moving from isolated environmental approaches such as Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) towards more comprehensive sustainability assessments (LCSA). However, this evolution remains incipient and uneven across regions and approaches. The results show a strong reliance on the use of secondary databases such as Ecoinvent, GaBi, and Agrifootprint in approximately 90% of the studies, which introduces systematic biases and limits the representativeness of the results. Marked regional differences are also observed: studies from West Africa focus primarily on the impacts of deforestation and water use, while in Latin America, assessments of agrochemicals and the valorization of byproducts prevail, reflecting both local conditions and distinct methodological preferences [53].

Agroforestry systems are emerging as alternatives with clear environmental and social advantages—for example, reductions of up to 57% in global warming potential and improvements in climate resilience—although they exhibit lower yields and greater operational complexity, highlighting the trade-offs between productivity and sustainability [54]. Methodologically, the integration of social and economic dimensions is still limited by the lack of standardized indicators and consistent weighting methods, despite the progress of hybrid approaches that incorporate multi-criteria analysis (AHP-TOPSIS).

Likewise, the review highlights concrete opportunities for a circular economy, particularly the valorization of cocoa husks, which could reduce the environmental footprint by up to 63% and generate additional economic benefits [39,55]. However, its adoption is restricted by technological and logistical barriers. Finally, the authors connect the identified methodological limitations with structural inequalities in the value chain, where producers receive less than 7% of the final product value. This highlights that sustainability assessments that do not incorporate the socioeconomic dimension are necessarily incomplete [54].

Taken together, the findings of this review go beyond a descriptive synthesis to offer a critical and integrative view of the current state of cocoa sustainability studies. By proposing a unified conceptual framework for Sustainable Cocoa Sustainability Assessments (SCSA) with standardized indicators, standardized weighting matrices, and systematic uncertainty analysis, this work contributes to strengthening the methodological and practical basis for moving towards more comparable, comprehensive, and useful sustainability assessments for decision-making in the cocoa sector.

7. Conclusions

This systematic literature review on LCA applied to cocoa has allowed us to critically identify its contribution to agricultural scientific knowledge and its potential to inform decision-making toward more sustainable value chains. The analysis examines methodological trends and impact categories in cocoa LCA. It also identifies the main environmental critical points and data limitations and explores the role of socio-economic dimensions as an essential component that is underrepresented in most studies evaluating sustainability. The comparative analysis of existing studies confirms that the most significant environmental impacts are concentrated in the cultivation phase, which is characterized by high water consumption, especially in conventional monoculture systems, and in the industrial processing phase, which requires intensive amounts of energy, primarily due to the use of machinery and transportation. A predominance of “cradle-to-gate” LCA approaches was identified, which, while simplifying the analysis, limits a comprehensive understanding of the impacts throughout the entire value chain, including consumption and the end of the product’s life.

The validity and robustness of these findings are intrinsically linked to the data’s quality and specificity. To the detriment of the collection of primary information specific to each productive context, the outstanding dependence on secondary databases constitutes a crucial methodological limitation that affects the precision and comparability of the studies. This challenge is aggravated by the perennial nature of cocoa cultivation, as its prolonged maturation period and extensive productive cycles make it difficult to define representative temporal limits and the inventory of consistent primary data. Furthermore, this review highlights the absence of region-specific LCA datasets capable of capturing the diversity of environmental pressures across cocoa-producing regions. Developing such parameter systems is essential to improve the accuracy and policy relevance of future assessments, enabling locally adapted sustainability strategies for producers in Latin America, West Africa, and Southeast Asia.

Beyond environmental aspects, this review highlights that socioeconomic challenges are fundamental to comprehensive sustainability assessment. The significant asymmetry in value distribution, with producers receiving a marginal share of the final price of chocolate, coupled with the financial vulnerability inherent in the waiting period for the first harvest, accentuates poverty and limits the adoption of more sustainable practices, such as agroforestry or organic systems, which entail higher initial costs. Therefore, any sustainability strategy derived from LCAs will be incomplete if it does not simultaneously integrate social and economic dimensions, aligning with key SDGs such as SDG 8 (Decent Work) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities).

Despite these limitations, LCA remains an invaluable tool for identifying environmental hotspots and guiding strategic interventions. The implementation of agroforestry systems, improving energy efficiency in processing, and valorizing byproducts based on circular economy principles are promising avenues for reducing the sector’s environmental footprint. The systematic use of sensitivity and uncertainty analysis is essential to refine the models and quantify the variability of the results to increase the reliability of these assessments.

Overall, the findings visualised throughout the figures and tables support the identification of key impact hotspots, particularly in the cultivation and industrial processing stages. By linking these results to methodological recommendations, this review demonstrates how enhanced LCA frameworks—through the integration of social and economic dimensions, region-specific datasets, and uncertainty analyses—can provide more comprehensive and actionable sustainability assessments. These insights directly address the central research question and reinforce the relevance of LCA as a decision-support tool for advancing sustainable cocoa value chains.

Author Contributions

R.F.C.-Q. participated in the review of the resources used, supervised the methodology and participated in the review of the manuscript. D.M.C.-C. and L.S.C.-M. participated in the construction of the original draft, specifically in the methodology and results sections. S.P.-R. participated in the review of the resources used and in the discussion section of the original draft, and A.C. and J.C.C.-Q. contributed to the overall supervision of the draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by CELISE project “Sustainable production of Cellulose-based products and additives to be used in SMEs and rural areas” funded by European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme, with grant agreement No 101007733. In addition, this project was supported by the program: 948–2024 ORQUÍDEAS MUJERES EN LA CIENCIA, within the research Project: “Estudio de las posibilidades del uso de biomasa endógena colombiana en la producción de bio-productos a través de métodos termo- y electro-catalíticos” Code: 109361.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude for the financial support given by the projects mentioned in funding section.

Conflicts of Interest

Author R.F.C.-Q. was employed by the company Fundacion BERSTIC. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| GHG | Greenhouse gases |

| S-LCA | Social Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCC | Life Cycle Costing |

| LCSA | Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| FUs | Functional units |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| GIS | Geographical Information System |

| MCDA | Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis |

| ODP | Ozone Depletion Potential |

| CED | Cumulative Energy Demand |

| HTP | Human Toxicity Potential |

| IOA | Input-Output Analysis |

| MCDM | Multi-criteria Decision Making |

| CSVA | Convergent Stress Value Analysis |

| EMET | Extreme Model Evaluation Trajectories |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| TOPSIS | Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution |

| KOH | Potassium Hydroxide |

| UNDP | United Nations Development Programme |

| ILO | International Labour Organization |

| PSILCA | Product Social Impact Life Cycle Assessment |

| CSR | Corporate Social Responsibility |

References

- International Cocoa Organization—ICCO. Cocoa Statistics—November 2023 Quarterly Bulletin of Cocoa Statistics. 2023. Available online: https://www.icco.org/november-2023-quarterly-bulletin-of-cocoa-statistics/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Statista. Chocolate Confectionery—Worldwide | Market Forecast. 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/outlook/cmo/food/confectionery-snacks/confectionery/chocolate-confectionery/worldwide (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Caicedo-Vargas, C.; Pérez-Neira, D.; Abad-González, J.; Gallar, D. Assessment of the environmental impact and economic performance of cacao agroforestry systems in the Ecuadorian Amazon region: An LCA approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 849, 157795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boakye-Yiadom, K.A.; Duca, D.; Foppa Pedretti, E.; Ilari, A. Environmental Performance of Chocolate Produced in Ghana Using Life Cycle Assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, Y. Analyzing the environmental footprint of the chocolate industry using a hybrid life cycle assessment method. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2025, 25, 100912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeswani, H.K.; Hellweg, S.; Azapagic, A. Accounting for land use, biodiversity and ecosystem services in life cycle assessment: Impacts of breakfast cereals. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 645, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntiamoah, A.; Afrane, G. Environmental impacts of cocoa production and processing in Ghana: Life cycle assessment approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2008, 16, 1735–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Dong, Y. Applications of Life Cycle Assessment in the Chocolate Industry: A State-of-the-Art Analysis Based on Systematic Review. Foods 2024, 13, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olarte, M.; Muñoz, C. Sustainable practices in the cocoa value chain: A systematic literature review. Tendencias 2025, 26, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, J.P.; Hardy, F.W.; Harvey, C.A. Carbon footprint of primary production of cacao: A meta-analytical review. Environ. Rev. 2025, 33, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Sustainable Bioeconomy and FAO. Project. 2022, p. 4p. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/handle/20.500.14283/cb7445en (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Fountain, A.C.; Hütz-Adams, F. Cocoa Barometer 2022. 2022-USA EditionVOICE Network. Available online: https://voicenetwork.cc/es/barometro-del-cacao/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Benoît Norris, C.; Traverso, M.; Neugebauer, S.; Ekener, E.; Schaubroeck, T.; Russo Garrido, S.; Berger, M.; Valdivia, S.; Lehmann, A.; Finkbeiner, M.; et al. (Eds.) Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020; 140p. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera Almanza, A.M.; Corona, B. Using Social Life Cycle Assessment to analyze the contribution of products to the Sustainable Development Goals: A case study in the textile sector. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1833–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrera-Ramírez, J.; Prado, V.; Solheim, H. Life cycle assessment and socioeconomic evaluation of the illicit crop substitution policy in Colombia. J. Ind. Ecol. 2019, 23, 1237–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López del Amo, B.; Akizu-Gardoki, O. Derived Environmental Impacts of Organic Fairtrade Cocoa (Peru) Compared to Its Conventional Equivalent (Ivory Coast) through Life-Cycle Assessment in the Basque Country. Sustainability 2024, 16, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organización Internacional de Normalización. Gestión ambiental — Análisis del ciclo de vida — Principios y marco de referencia (ISO 14040). 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Organización Internacional de Normalización. Gestión ambiental — Análisis del ciclo de vida — Requisitos y directrices (ISO 14044). 2006. Available online: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- González-García, S.; Castanheira, É.G.; Dias, A.C.; Arroja, L. Using Life Cycle Assessment methodology to assess UHT milk production in Portugal. Sci. Total Env. 2013, 442, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutel, C.L.; De Baan, L.; Hellweg, S. Two-step sensitivity testing of parametrized and regionalized life cycle assessments: Methodology and case study. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5660–5667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessou, C.; Basset-Mens, C.; Tran, T.; Benoist, A. LCA applied to perennial cropping systems: A review focused on the farm stage. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 340–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparrevik, M.; Lindhjem, H.; Andria, V.; Fet, A.M.; Cornelissen, G. Environmental and Socioeconomic Impacts of Utilizing Waste for Biochar in Rural Areas in Indonesia—A Systems Perspective. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4664–4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz-R, O.O.; Villamizar Gallardo, R.A.; Rangel, J.M. Applying life cycle management of Colombian cocoa production. Ci. Tecnol. Aliment. 2014, 34, 62–68. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=395940094009 (accessed on 30 November 2024). [CrossRef]

- Utomo, B.; Prawoto, A.A.; Bonnet, S.; Bangviwat, A.; Gheewala, S.H. Environmental performance of cocoa production from monoculture and agroforestry systems in Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134 Pt B, 583–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez Neira, D. Energy sustainability of Ecuadorian cacao export and its contribution to climate change. A case study through product life cycle assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2560–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Neira, D.; Copena, D.; Armengot, L.; Simón, X. Transportation can cancel out the ecological advantages of producing organic cacao: The carbon footprint of the globalized agrifood system of Ecuadorian chocolate. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesce, E.; Olivieri, G.; Pairotti, M.B.; Romani, A.; Beltramo, R. Life cycle assessment as a tool to integrate environmental indicators in food products: A chocolate LCA case study. Int. J. Environ. Health 2016, 8, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recanati, F.; Marveggio, D.; Dotelli, G. From beans to bar: A life cycle assessment towards sustainable chocolate supply chain. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 613–614, 1013–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschio, G.; Smetana, S.; Contreras, C.; Heinz, V.; Mathys, A. Spatio-Temporal Differentiation of Life Cycle Assessment Results for Average Perennial Crop Farm: A Case Study of Peruvian Cocoa Progression and Deforestation Issues. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 1378–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantas, A.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. A framework for evaluating life cycle eco-efficiency and an application in the confectionary and frozen-desserts sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2020, 21, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.R.; Moreschi, L.; Gallo, M.; Vesce, E.; Del Borghi, A. Environmental analysis along the supply chain of dark, milk and white chocolate: A life cycle comparison. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armengot, L.; Beltrán, M.J.; Schneider, M.; Simón, X.; Pérez-Neira, D. Food-energy-water nexus of different cacao production systems from a LCA approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 304, 126941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Paitan, C.; Verburg, P.H. Accounting for land use changes beyond the farm-level in sustainability assessments: The impact of cocoa production. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 825, 154032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dianawati, D.; Indrasti, N.S.; Ismayana, A.; Yuliasi, I.; Djatna, T. Carbon Footprint Analysis of Cocoa Product Indonesia Using Life Cycle Assessment Methods. J. Ecol. Eng. 2023, 24, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avadí, A. Environmental assessment of the Ecuadorian cocoa value chain with statistics-based LCA. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2023, 28, 1495–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idawati, I.; Sasongko, N.A.; Santoso, A.D.; Sani, A.W.; Apriyanto, H.; Boceng, A. Global Journal of Environmental Science and Management Life cycle assessment of cocoa farming sustainability by implementing compound fertilizer. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2024, 10, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, T.; Hidayatno, A.; Setiawan, A.D.; Komarudin, K.; Suzianti, A. Environmental Impact Analysis to Achieve Sustainability for Artisan Chocolate Products Supply Chain. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tovar, A.M.; Valencia, L.F.; Villa, A.L. Life cycle assessment of Colombian cocoa pod husk transformation into value-added products. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 25, 101772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darmawan, D.; Mutalib, A. Evaluation of environmental impact on cocoa production and processing under life cycle assessment method: From beans to liquor. Environ. Adv. 2024, 15, 100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna Ostos, L.M.; Roche, L.; Coroama, V.; Finkbeiner, M. Social life cycle assessment in the chocolate industry: A Colombian case study with Luker Chocolate. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 929–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Green, A.; Burkard, J.; Gubler, I.; Borradori, R.; Kohler, L.; Meuli, J.; Krähenmann, U.; Bergfreund, J.; Siegrist, A.; et al. Valorization of cocoa pod side streams improves nutritional and sustainability aspects of chocolate. Nat. Food. 2024, 5, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khang, D.S.; Linh, N.H.K.; Hoai, B.T.M. Life Cycle Assessment of Cocoa Products in Vietnam. Process. Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2024, 8, 1003–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmah, D.M.; Januardi; Nurlilasari, P.; Mardawati, E.; Kastaman, R.; Agus Kurniawan, K.I.; Sofyana, N.T.; Noguchi, R. Integrating life cycle assessment and multi criteria decision making analysis towards sustainable cocoa production system in Indonesia: An environmental, economic, and social impact perspective. Heliyon 2024, 10, e38630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinci, G.; Ruggeri, M.; Gobbi, L.; Savastano, M. Social Life Cycle Assessment of Cocoa Production: Evidence from Ivory Coast and Ghana. Resources 2024, 13, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, D.D.; Khasanah, N.; Sari, R.R.; van Noordwijk, M. Avoidance of tree-site mismatching of modelled cacao production systems across climatic zones: Roots for multifunctionality. Agric. Syst. 2024, 216, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantas, A.; Jeswani, H.K.; Stamford, L.; Azapagic, A. Environmental impacts of chocolate production and consumption in the UK. Food Res. Int. 2018, 106, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, L.; Pfister, S. Global Biodiversity Loss by Freshwater Consumption and Eutrophication from Swiss Food Consumption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 7019–7028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Tassielli, G.; Renzulli, P.A.; Castellani, V.; Sala, S. Environmental impacts of food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 753–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flora, C.B.; Sibelet, N. Contribution of Local Knowledge in Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) to the Well-Being of Cocoa Families in Colombia: A Response from the Relationship. Agric. Hum. Values 2024, 42, 461–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decerna. What Are the Limitations of Life Cycle Assessment? Decerna Knowledge-Base. 2025. Available online: https://www.decerna.co.uk/knowledge-base/life-cycle-assessment/lca/what-are-the-limitations-of-life-cycle-assessment/ (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Ngan, S.P.; Ngan, S.L.; Lam, H.L. An Overview of Circular Economy-Life Cycle Assessment Framework. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2021, 88, 1123–1128. [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco-Jaramillo, L.; Vargas-Tierras, Y.; Habibi, N.; Caicedo, C.; Chanaluisa, A.; Paredes-Arcos, F.; Viera, W.; Almeida, M.; Vásquez-Castillo, W. Agroforestry Systems of Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Forests 2024, 15, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandanaa, J.; Asante, I.K.; Annang, T.Y.; Blockeel, J.; Heidenreich, A.; Kadzere, I.; Schader, C.; Egyir, I.S. Social and Environmental Trade-Offs and Synergies in Cocoa Production: Does the Farming System Matter? Sustainability 2025, 17, 1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picchioni, F.; Warren, G.P.; Lambert, S.; Balcombe, K.; Robinson, J.S.; Srinivasan, C.D.; Gomez, L.; Faas, L.; Westwood, N.J.; Chatzifragkou, A.; et al. Valorisation of Natural Resources and the Need for Economic and Sustainability Assessment: The Case of Cocoa Pod Husk in Indonesia. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).