Highlights

What are the main findings?

- New Intelligent Assistant for TBM Tunneling: This study created and tested an intelligent assistant that uses a large language model to help human operators communicate better with the Tunnel Boring Machines.

- Effective Technology: The assistant’s method for recognizing intentions showed strong accuracy in tests, which is essential for understanding operator commands.

- Real-World Benefits: Case studies in engineering showed that the assistant provides valuable advantages by making systems more transparent, building user trust, and enhancing safety in tunneling operations.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- A Practical Model for Urban Automation: This work provides a viable “human-in-the-loop” operational model for safely deploying autonomous systems during the construction of critical smart-city underground infrastructure.

- A Trust-Centric Path to Adoption: It demonstrates that building user trust through AI-powered transparency is as crucial as technological advancement for the successful integration of autonomous technologies in complex urban environments.

Abstract

The development of autonomous tunneling is crucial for building the intelligent underground infrastructure that smart cities require. However, in complex urban environments, the need for frequent manual intervention during Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) operation remains a challenge, hindering overall efficiency and safety. To address the human–machine collaboration gap, this study analyzes practical experiences from six tunnel projects that use autonomous driving systems. Building on this foundation, we develop an intelligent assistant powered by a large language model (LLM). The assistant constructs a complete service architecture and intervention mechanism, proposes a phased intention recognition framework, and uses conversational interaction to achieve efficient human–machine communication. Experimental results demonstrate the strong classification performance of our intention recognition model. Furthermore, engineering case studies validate the assistant’s effectiveness in enhancing operational transparency, increasing user trust, bridging the human–machine information gap, and ultimately ensuring safer and more reliable tunneling. This research provides a feasible and innovative technological path for human–machine collaboration in the construction of critical urban infrastructure.

1. Introduction

Cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and the Internet of Things have accelerated the development of intelligent and unmanned construction equipment, a trend that is vital for addressing the growing infrastructure demands of expanding urban populations and the development of smart cities. In recent years, the TBM, a critical device for underground engineering, has made significant progress in automation and intelligence [1]. Core operational processes such as excavation, propulsion, deviation correction, and muck discharge are increasingly being automated for decision-making and control. For example, the TBM automatic tunneling system developed by Malaysia MMG [2], the “Zhiyu” autonomous tunneling system jointly developed by Shanghai Tunnel Engineering Co., Ltd. and Shanghai University [3], and the edge–cloud control system for intelligent tunneling designed by China Railway Tunnel Group [4] have all been successfully applied in engineering projects. These efforts represent the first step toward the industrial application of autonomous tunneling technology.

However, due to the complexity of the tunneling environment and the limitations of intelligent control models, current TBM automation has not yet achieved full autonomy. During tunneling, drivers still need to monitor the process in real time and decide whether to take over manual control based on tunneling conditions [5]. Moreover, differences in technical personnel’s cognitive abilities, trust levels, and human–machine collaboration modes can lead to significant variations in performance, even when using the same autonomous tunneling system under similar engineering conditions [6]. Therefore, the level of human–machine collaboration plays a crucial role in fully realizing the potential of TBM autonomous tunneling systems.

An optimal human–machine collaboration model is not merely about defining ownership of control but about ensuring that both parties, human drivers and automated systems, can share information, make complementary decisions, and transfer control in line with the specific engineering context, system capabilities, and operational requirements. This collaborative approach ultimately enhances the safety and quality of tunnel construction [7]. Currently, research on human–machine collaboration in TBM autonomous driving is limited. However, drawing from existing practices and insights from the automotive sector, four key factors influencing the effectiveness of human–machine collaboration can be identified:

- (1)

- Cognitive and experience differences among drivers: TBM tunneling involves complex geological conditions and control logic. Drivers with varying levels of experience may exhibit significantly different levels of dependency and trust in the automation system. For example, experienced drivers may be more inclined to intervene manually, whereas novice drivers tend to rely too much on the automated system [8].

- (2)

- Subjective preferences of drivers: Drivers may question the system’s control actions due to personal habits or preferences for specific control strategies, leading to frequent manual intervention, which can reduce collaboration efficiency [9].

- (3)

- System transparency and explainability: Current automated tunneling systems often lack transparency in their decision-making logic [10] and do not provide sufficient human–machine interaction pathways to explain control strategies. This lack of transparency can lead to doubts about the system’s reliability and, in some cases, result in human–machine conflict due to excessive manual intervention [11].

- (4)

- System fault tolerance and safety mechanisms: If an automated tunneling system lacks a collaborative fault-tolerant mechanism with drivers for handling unforeseen situations (such as cutterhead jamming or sudden ground surges), it may lead to decision delays or misjudgments, posing a safety risk [12]. This potential risk introduced by the automation system creates barriers to drivers’ acceptance, making them hesitant or overly cautious in its use. It is evident that improving the collaboration between the TBM autonomous tunneling system and the operator requires efforts in multiple areas, including optimizing human–machine interaction models, enhancing decision transparency, reducing cognitive load, establishing trust pathways, and strengthening safety redundancies.

With the development of LLM technology, LLM-based intelligent agents [13] not only possess excellent natural language understanding and interaction capabilities but also decision-making and task-execution abilities. This provides technical support for addressing the poor explainability of autonomous tunneling control processes, communication difficulties, promoting decision transparency, and enhancing user trust and tunneling safety. However, the issues, doubts, parameter adjustment requests, and anomaly feedback raised by the driver during the tunneling process correspond to different collaboration tasks. The system must accurately recognize the driver’s intent to dispatch the appropriate task-oriented intelligent agents, thereby avoiding misoperations, erroneous feedback, or unnecessary manual control interventions. Therefore, intention recognition is a prerequisite for achieving high-quality human–machine collaboration. This paper designs and develops an LLM-based intelligent assistant for TBM autonomous tunneling, with intention recognition at its core. By coordinating the work of six task-oriented intelligent agents, the assistant provides multifunctional services such as explanation, evaluation, execution, and monitoring for the driver. Through communication with the intelligent assistant, drivers can resolve doubts, reduce cognitive load, and improve decision transparency. The intelligent assistant promptly identifies tunneling anomalies and proactively communicates with the driver, enhancing system fault tolerance and improving safety. Drivers can also issue commands to the intelligent assistant, efficiently conveying project information and control preferences, which, through automated task execution, enhances system adaptability.

This paper is divided into six sections. The second section reviews the research progress of foundational LLM-based intelligent agents and human–machine collaboration in autonomous driving systems. The third section analyzes the requirements for human–machine collaboration from the perspective of autonomous tunneling systems, defines the functional roles of the intelligent assistant, and designs a human–machine collaboration service model centered on the assistant. The fourth section focuses on the core challenge of implementing the intelligent assistant, intention recognition, and presents a framework with clear advantages in accuracy. The fifth section describes the practical application and performance of the intelligent assistant. Finally, the last section provides conclusions and future research directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Human–Machine Collaboration in Autonomous Driving

Human–machine collaboration is a model that optimizes interaction and cooperation between humans and machines to achieve efficient task execution and decision support [14]. It emphasizes leveraging the strengths of both humans and machines, allowing them to work together to complete tasks more efficiently and safely [15,16]. Currently, research on human–machine collaboration in TBM autonomous driving is limited. However, the field of human–machine collaboration in autonomous driving for automobiles is highly active. Researchers have designed various collaboration models to improve coordination between drivers and autonomous driving systems [17], address the challenges posed by complex, dynamic traffic environments [18], optimize the driving experience, and enhance road safety and traffic efficiency [19]. These findings provide valuable references for addressing the human–machine collaboration issues in TBM autonomous tunneling.

Increasing system transparency and enhancing human adaptability to the system are effective strategies for improving human–machine collaboration [20]. Lippi et al. [21] introduced a causal graph explanation mechanism in intelligent manufacturing, which improved engineers’ acceptance of scheduling system recommendations. Ha et al. [22] suggested that systems could enhance user trust in AI by offering “counterfactual explanations and historical response consistency”.

Reducing the human information-processing load and presenting system information in more intuitive ways are also practical approaches. Adami et al. [23] utilized VR/AR technology to create an immersive monitoring environment, while Wang et al. [24] proposed overlaying key driving information onto the windshield to reduce the driver’s information search and processing pressure during autonomous driving, thereby helping the driver focus on higher-level decision-making. You et al. [25] developed a multimodal AR interface that integrates voice, visual, and haptic feedback to guide the driver in quickly understanding the system’s intentions, significantly improving human–machine collaboration efficiency and safety.

Understanding human needs and providing personalized assistance tailored to individual preferences is crucial for improving the user experience and system acceptance [26]. Xu et al. [27] designed a personalized driver assistant based on large language models, which customizes warning content for different drivers under various conditions, thereby enhancing driving safety. Fang et al. [28] developed an interactive multi-modal driving assistance system that combines LLM with driver behavior and voice input to dynamically adapt the content and mode of prompts dynamically, aligning autonomous driving styles with individual driver preferences. Ali et al. [29] proposed a personalized driving assistance system based on deep learning that leverages the driver’s physiological and behavioral data to optimize the driving environment in real time and adjust in-car feedback to enhance safety and comfort.

Active interaction can enhance the efficiency of human–machine collaboration. Sun found that proactive human–machine interaction increased driver trust in Level 4 autonomous vehicles [30]. Liu et al. [31] designed an interactive visual interface that improved driver trust in Level 2 autonomous driving scenarios, significantly enhancing collaboration efficiency between the driver and the system. Woide et al. [32] highlighted that in collaborative driving systems, proactive interaction through real-time feedback and intelligent scheduling could reduce the trust gap between the driver and the autonomous driving system, significantly improving cooperation efficiency and safety.

In summary, enhancing system transparency, understanding driver needs, reducing information processing load, and establishing proactive interaction mechanisms are key strategies for improving human–machine collaboration in autonomous driving, particularly in complex and high-risk operational environments. These conclusions align closely with the human–machine collaboration needs in TBM autonomous tunneling scenarios. The methods and concepts derived from this research provide a clear theoretical foundation and technical insights for the development of the proposed LLM-based intelligent assistant for TBM autonomous tunneling.

2.2. LLM-Based Intelligent Agents

LLMs utilize the Transformer architecture and, after pretraining on vast amounts of text data, possess powerful language understanding and generation capabilities [13]. LLM-based intelligent agents (LLM Agents) are artificial intelligence components that use LLMs as the core reasoning and decision-making engine. These agents not only understand and generate natural language but also autonomously plan, reason, and make decisions based on environmental information, user instructions, or goals. They can execute complex tasks by invoking tools and taking actions.

LLM Agents can be classified into question-answering (QA), task-oriented, chatbot, and recommendation systems. QA agents are designed to accurately and efficiently answer factual or knowledge-based questions from users. For example, CarExpert, developed by Rony et al. [33], is an LLM-based, retrieval-augmented QA system for in-car use that can accurately answer driving-related questions. Li et al. [34] constructed an intelligent QA system using a multi-layer bidirectional Transformer architecture, incorporating weight pruning to reduce redundant parameters, which significantly improved the agent’s ability to answer complex questions.

Task-oriented agents focus on handling specific tasks, making task clarity especially important. For instance, Garello et al. [35] developed a robot agent that autonomously executes task-driven functions through dialogue. Xu et al. [36] proposed an expert hybrid mechanism for task judgment, scheduling perception, prediction, and planning functions in autonomous driving.

Chatbot agents engage in natural, coherent, and emotionally aware dialogues, providing companionship, entertainment, or psychological support [37]. Li et al. [38] introduced LARM (Large Auto-Regressive Model), which, combined with a feedback reward mechanism, enables natural language conversation generation and continuous state prediction in long-term tasks, facilitating continuous dialogue in driving scenarios. Du et al. [39] proposed a “Rewrite + ReAct + Reflect” interaction strategy to enhance the proactivity and context management of LLM-driven in-car assistants, improving dialogue responsiveness and consistency.

Recommendation agents offer personalized services based on users’ historical behavior and real-time preferences to enhance user satisfaction. Constructing user profiles and identifying user needs are key factors. Yu et al. [40] proposed an interactive thought-enhanced method for large models, which decomposes user needs and plans sub-tasks to coordinate recommendation tasks, effectively capturing real-time user needs and enhancing personalization. Yang et al. [41] introduced a self-supervised multi-agent LLM framework that integrates sensor data with user behavior information, using LLMs to identify latent user needs and generate real-time customized path-planning suggestions, thereby offering personalized travel recommendations. Zhu et al. [42] proposed an intelligent recommendation system that integrates knowledge graphs and LLM to detect changes in learning states and recommend different tasks to students.

It is evident that different types of LLM-based intelligent agents, due to their task-specific functions, require distinct technical implementation approaches and should be tailored to the particularities of the application scenario. While general-purpose LLM-based agents perform excellently in many domains, they fail to address the unique demands of TBM autonomous tunneling. The complexity of tunneling operations, characterized by rapid geological changes, complex working conditions, high-risk factors, and highly coupled decision-making [43,44], along with the specialized nature of operator communication, which often involves dense technical terminology, high contextual dependence, and a mix of problem types, makes it difficult for standard intention recognition models to maintain sufficient accuracy and robustness. Therefore, the development of a specialized intelligent assistant for tunneling operations, particularly one capable of high-reliability intention recognition within the engineering context, is essential for effective human–machine collaboration.

Building upon the advantages of task-oriented intelligent agents, this study proposes an LLM-based intelligent assistant specifically designed for TBM autonomous tunneling. The system places a strong emphasis on real-time recognition and classification of the driver’s intentions. As the core module of the system, intention recognition accurately interprets the driver’s inquiries and needs, mapping them to appropriate task categories, enabling the automatic scheduling of functions such as control evaluation, strategy explanation, and anomaly monitoring. By leveraging this capability, the intelligent assistant not only ensures accurate command understanding but also proactively provides decision support, integrating the TBM’s operational status and external environmental data to enhance human–machine collaboration efficiency and the reliability of automated control. Compared to general-purpose LLM agent frameworks, the proposed approach divides driver demands into six distinct tasks tailored to the unique characteristics of tunneling operations, establishing a specialized human–machine collaboration framework that ensures engineering applicability and scenario adaptability.

3. Design of Human–Machine Collaboration-Oriented Intelligent Assistant Service Model

The “Zhiyu” Autonomous Tunneling System (ZATS) integrates sensing, navigation, and AI algorithms to achieve automatic guidance, posture adjustment, and tunneling parameter optimization, thereby enhancing the safety and efficiency of tunnel construction. It has already been applied in more than sixty tunnel sections. This paper analyzes interaction data between on-site technical personnel and system service staff during tunneling for six sections of Shanghai Metro Lines 18 and 13 that utilize ZATS. This analysis aims to bridge the gap in human–machine interaction during tunneling.

3.1. Analysis of Issues and Responses in Autonomous Tunneling

3.1.1. Common Issues in Autonomous Driving

The ZATS operates through a remote WeChat-based service mechanism. Project managers, technical supervisors, drivers, and ZATS technical support staff communicate in real time within dedicated project service WeChat groups regarding the system’s operational status. These chat records provide a complete and authentic representation of the issues encountered during autonomous tunneling and their corresponding resolutions.

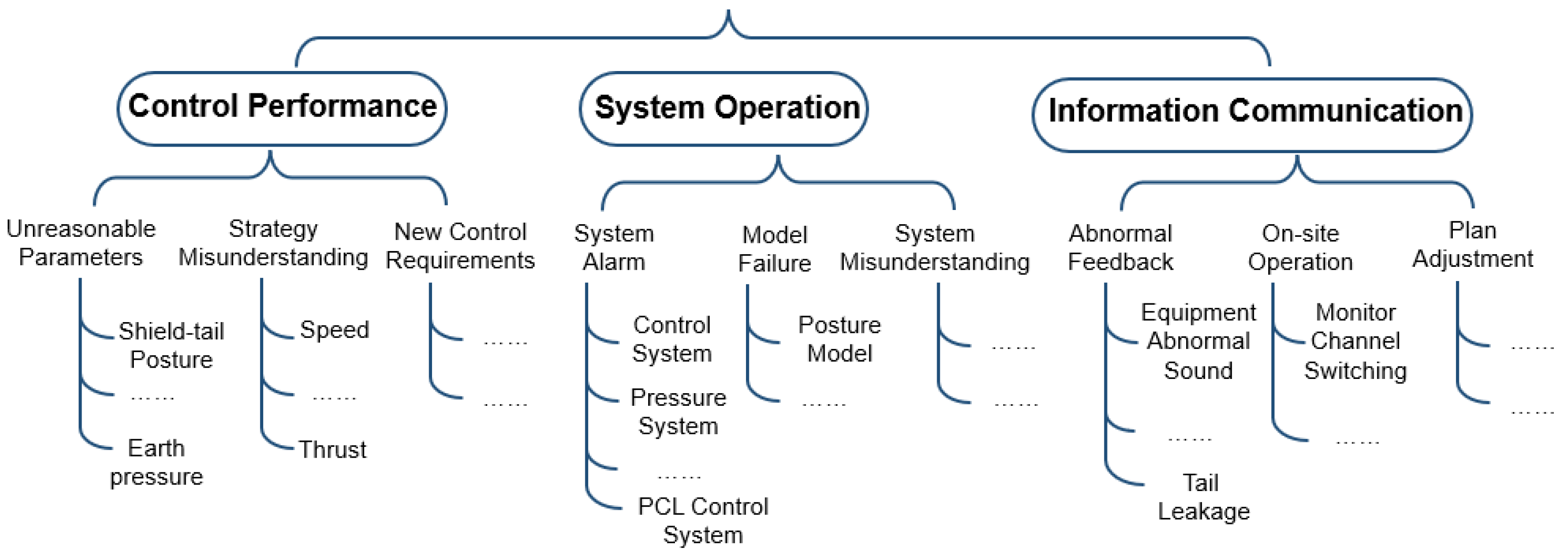

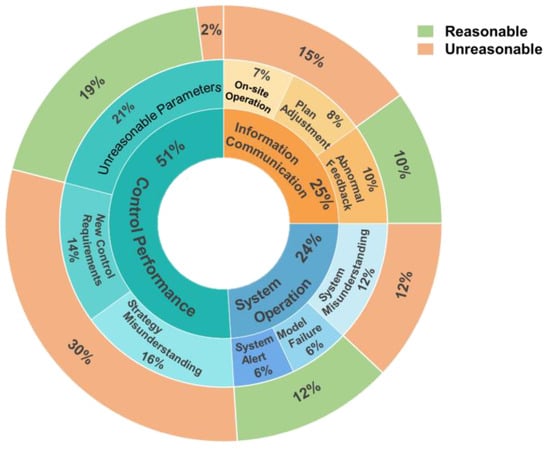

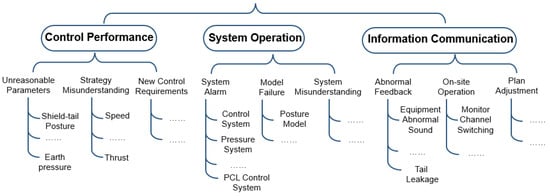

During the autonomous tunneling processes of six tunnel sections, a total of 435 service incidents occurred, of which 405 resulted in control mode switching (from autonomous mode to manual mode). These incidents are categorized into three main types: control performance, system operation, and information communication. (1) Control performance incidents refer to cases where drivers raised objections to the system’s control strategy or its outcomes, for instance, reporting that the propulsion oil pressure was unreasonable or that the cutterhead elevation was too low. (2) System operation incidents involve situations where drivers misuse system functions or misunderstand system outputs, such as forgetting to activate the control module or misinterpreting system warnings. (3) Information communication incidents refer to special situations, such as power failures, construction interruptions, or segment breakages, where drivers need to inform technical service staff due to the absence of an input channel for such events within the system

To further analyze potential human–machine collaboration issues, these three categories of service incidents were subdivided and examined to determine whether they led to manual mode switching. The analysis focused on determining whether each event stemmed primarily from communication and coordination needs or from control intervention requirements. The detailed results are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Event categories and service demands.

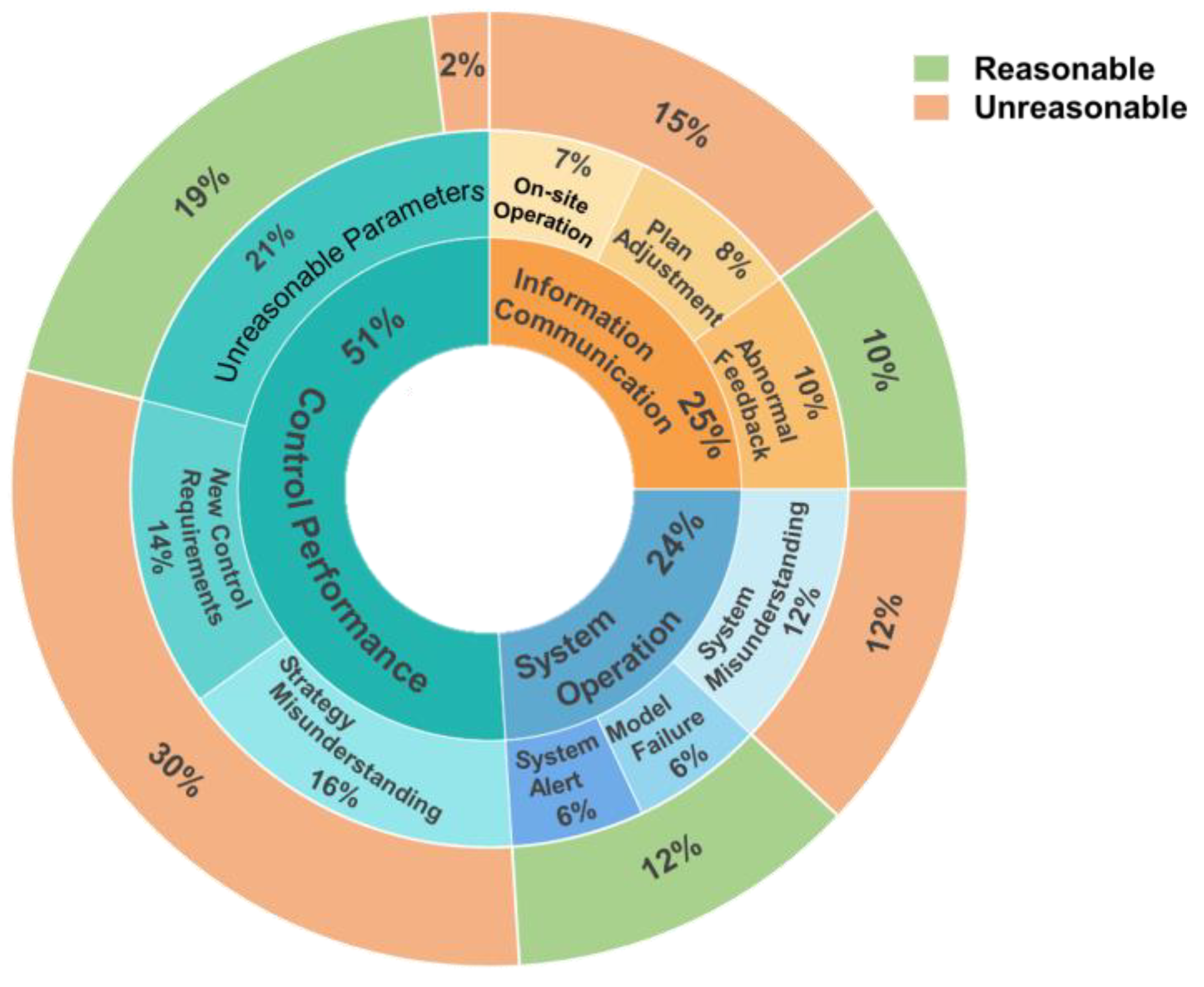

As shown in Table 1, many service events do not necessarily require switching to manual control intervention (switching from automated mode to manual mode). The decision is based on domain experts’ assessments. After the project, technicians classified manual intervention scenarios into fault-related and control-related switchovers. Fault-related switchovers were considered “reasonable,” while control-related ones were evaluated based on system performance before and after the switch. The project chief engineer reviewed the reasonableness of control-related switchovers, and if unclear, the autonomous driving team (three senior tunnel experts and two technical experts) conducted a discussion and vote. Switching to manual mode was deemed unreasonable if no safety or operational issues were detected. Among the 435 service events, 405 triggered manual intervention, which is clearly unreasonable. Therefore, the proportions of event categories were statistically analyzed, as shown in Figure 1. It was found that control performance accounted for approximately 51% of the total, with new control requirements and misunderstandings of the strategy together representing 30% and not requiring manual intervention. Similarly, in system operation incidents, system misunderstandings and information communication service events, such as on-site operations and plan adjustments, accounted for 27% and did not require manual intervention. This indicates that, due to the lack of appropriate human–machine interaction methods, frequent switching between control modes during autonomous tunneling significantly impacts the overall effectiveness of the autonomous tunneling control system.

Figure 1.

Distribution of service event types.

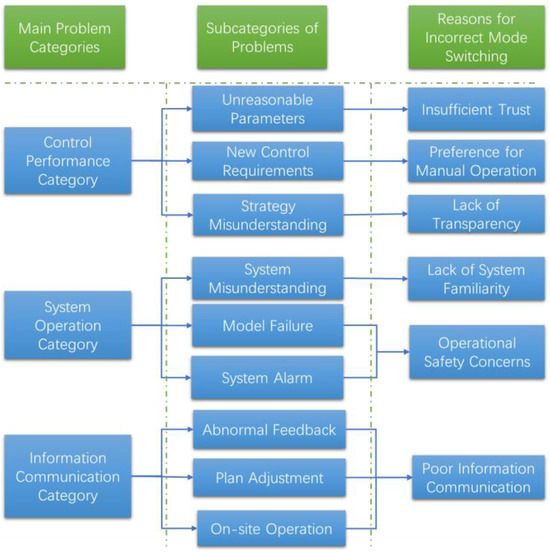

3.1.2. Handling Requirements for Autonomous Tunneling Issues

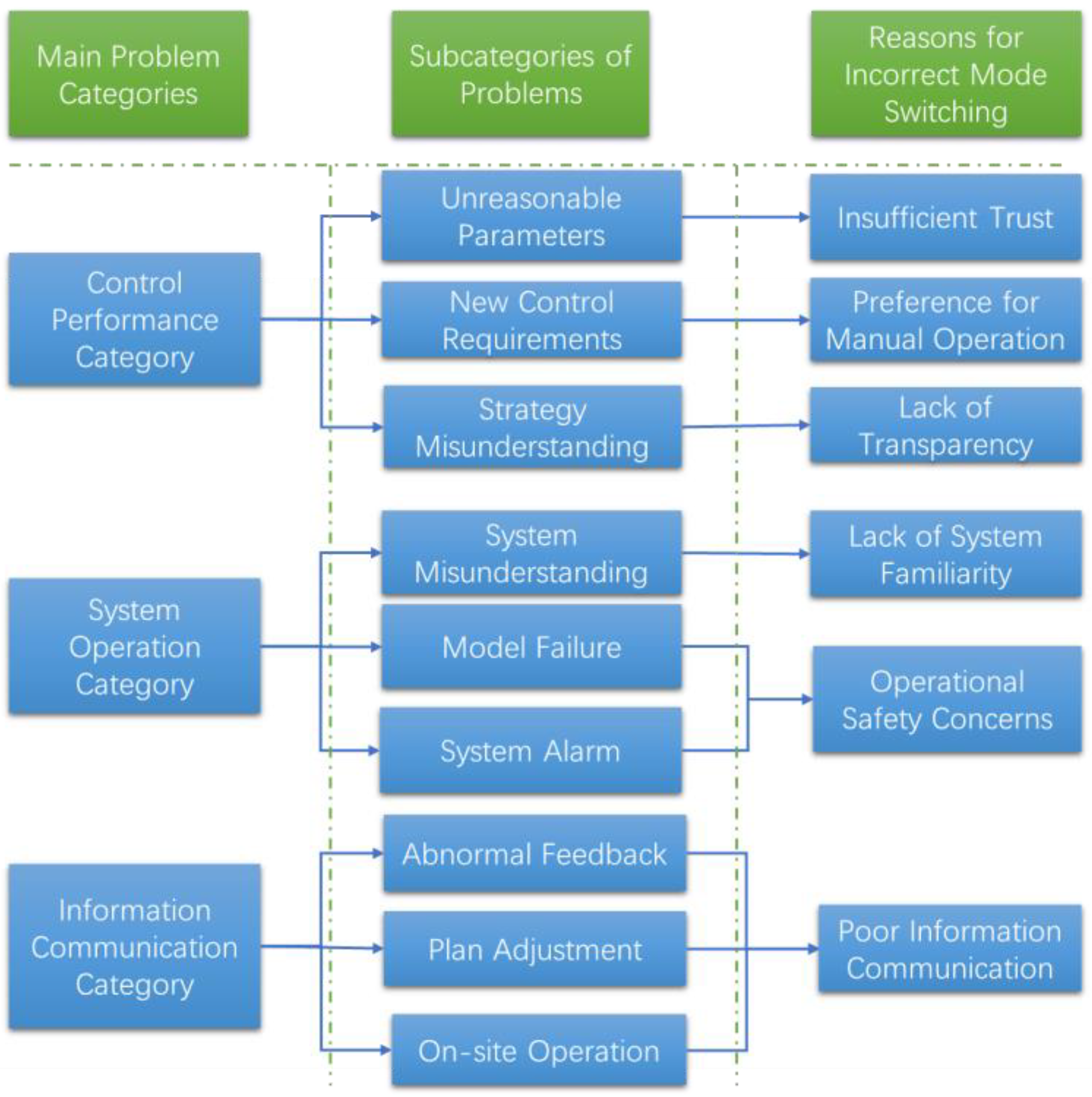

To reduce unnecessary manual control interventions, we analyzed the causes of control mode switching for each service event subcategory based on their specific characteristics. The objective is to identify automated or proactive service channels that can enhance and accelerate interactions with on-site personnel. By doing so, we aim to mitigate the negative impacts on human–machine collaboration caused by response delays, non-standardized communication, and unclear information exchange inherent in the current remote service process.

Based on the six major causes illustrated in Figure 2, the corresponding service requirements and service forms demanded by the engineering team can be summarized in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Analysis of the causes of control-switching service events.

Table 2.

Relationship between switching causes and service demands.

3.2. Agent Design

Based on the service requirements summarized in Table 2, six task-oriented agents are required: control evaluation, model explanation, control execution, anomaly monitoring, information acquisition, and system introduction. The definitions and key design considerations of these agents are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Agent definitions and design considerations.

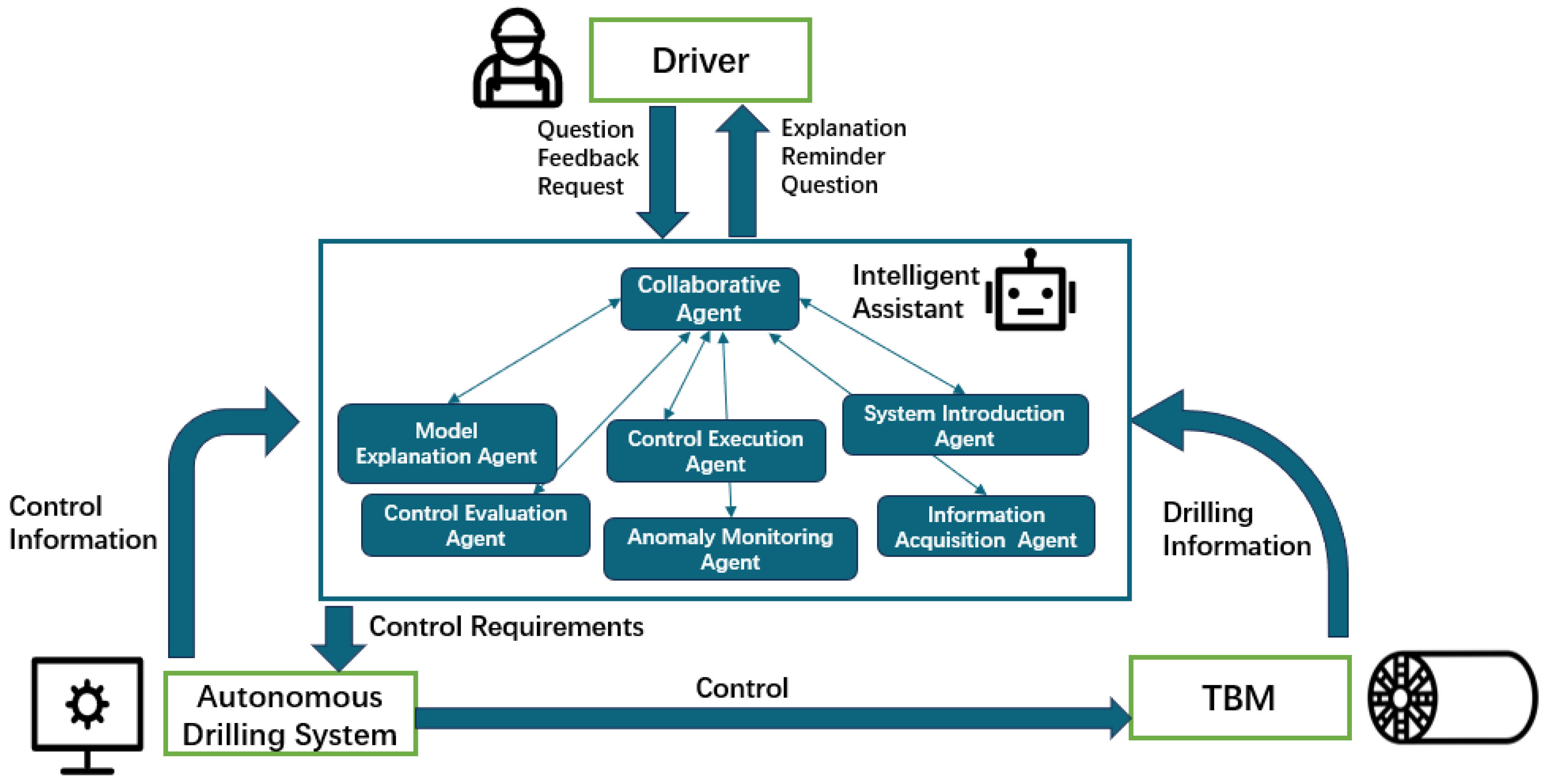

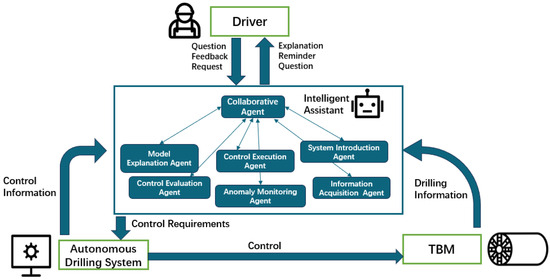

3.3. Human–Machine Collaboration Model with Intelligent Assistant Involvement

Although the six task-oriented agents listed in Table 3 perform different functions, their communication with on-site personnel must remain unified. Therefore, a coordination agent is additionally designed to serve as the primary communication interface with users. This agent interprets user intentions, determines the appropriate service category, activates the corresponding task-oriented agents, and conveys their execution results back to the user. An intelligent assistant composed of multiple collaborative agents is thus established. Through information sharing, task allocation, and cooperative decision-making, this assistant minimizes unnecessary human–machine switching and enhances the stability and utilization of the autonomous mode. Figure 3 illustrates the tunneling operation model under the human–machine collaboration enabled by the intelligent assistant.

Figure 3.

Human–Machine collaboration model with intelligent assistant involvement.

In this model, the intelligent assistant employs a collaborative agent as its core module, which is responsible for recognizing the driver’s intent and determining the task type. Once identified, the task is assigned to different specialized agents, including the model interpretation agent, control execution agent, and anomaly monitoring agent, for processing. The collaborative agent also serves as the communication bridge between these agents and the user, enabling bidirectional information exchange. Understanding and communicating with the user is the central function of the collaborative agent.

Within the human–machine collaboration framework, drivers interact with the intelligent assistant using natural language. During the conversation, the assistant identifies the event category and activates the appropriate agent based on the detected needs. Supported by the knowledge base, tunneling database, and related machine learning models, each agent performs specific tasks, including sending control commands to the TBM. If information is lacking or confirmation is needed, the intelligent assistant communicates with the collaborative agent to request additional details or verify the goal until all task requirements are met. Once the task is completed, the results are fed back to the intelligent assistant, creating a closed-loop control mechanism. Through this multi-agent collaboration, the system can execute tasks more efficiently, reduce manual intervention, and improve both automation stability and tunneling efficiency.

4. Intention Recognition Model

4.1. Intention Recognition Framework

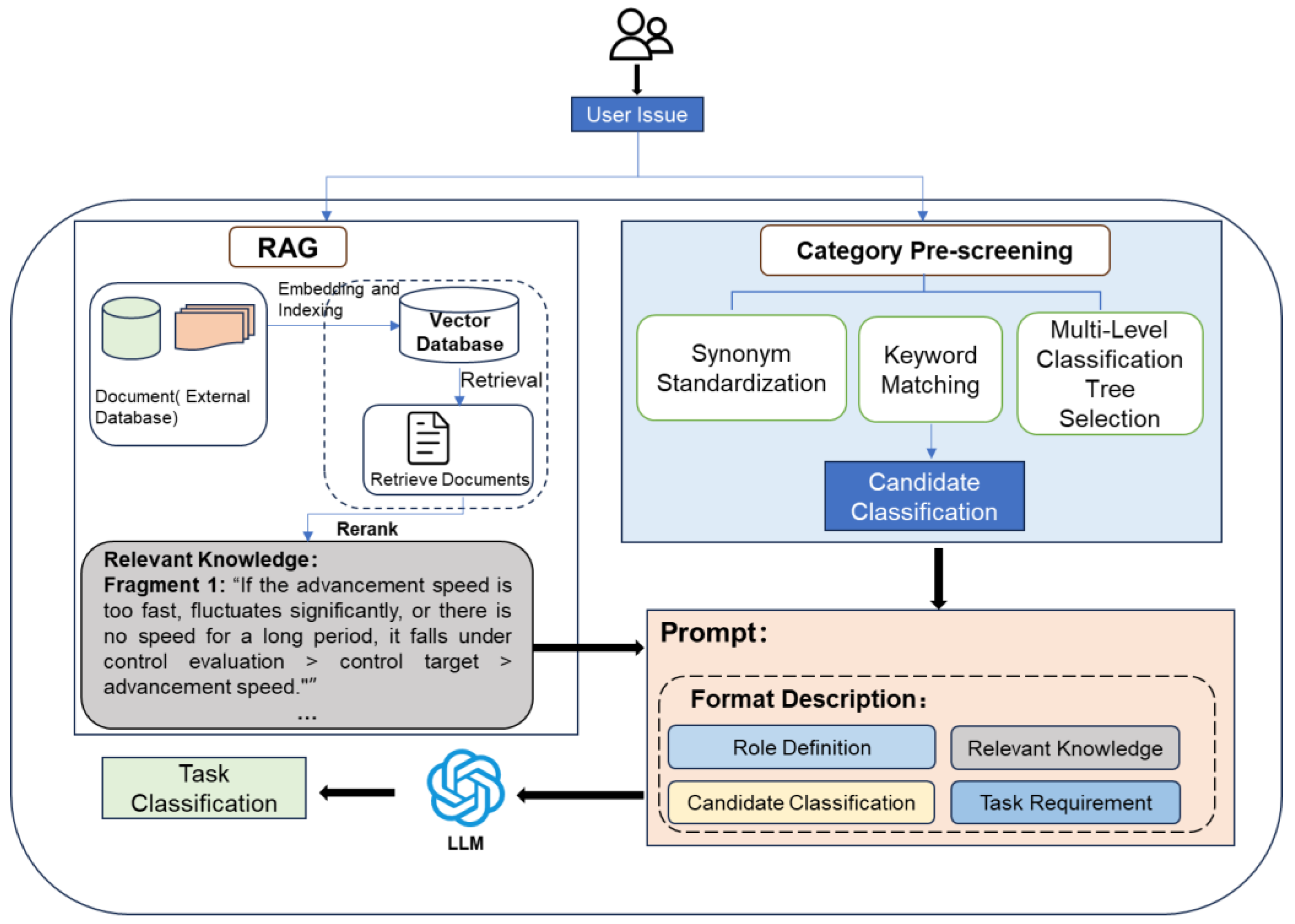

As the key component that directly interacts with humans, intention recognition is the first and most vital step for the collaborative agent to perform tasks effectively. The accuracy of intention classification serves as the foundation for reliable human–machine collaboration. To improve classification accuracy, this study proposes a Stepwise LLM Classification (SWLC) algorithm for intention recognition, as shown in Figure 4. The SWLC algorithm includes three modules: Category Pre-screening, Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG), and Prompt Construction. The classification process works as follows: (1) The Category Pre-screening module produces an initial set of candidate classifications. (2) The RAG module dynamically retrieves relevant information from external knowledge bases to gather highly related knowledge items. (3) Using the candidate classification set and the retrieved knowledge, prompt templates are created and input into the LLM to determine the final task classification.

Figure 4.

Intention recognition classification process. The RAG and category pre-screening modules collectively form part of the prompt module, with the final classification results ultimately generated by the large language model.

The Category Pre-screening module aims to narrow down potential event categories, thereby enhancing the classification accuracy of the large language model. The RAG module dynamically retrieves relevant information from external knowledge bases to supplement background context for task classification, providing domain-specific details that improve intention recognition. Since the LLM makes the final classification, prompt design is critical. To help the model accurately determine task categories in complex contexts and produce a traceable reasoning process, ensuring each classification has a clear rationale, we designed a dedicated prompt template. This template includes four key elements: role definition, candidate classification, relevant knowledge, and task requirements. These components guide the LLM to reason step-by-step and identify accurately, ensuring both the stability and interpretability of the classification results.

4.2. Key Technical Implementation

4.2.1. Category Pre-Screening

The Category Pre-screening module handles the initial classification of user inputs, ensuring accurate and efficient data for later LLM classification. This module includes three main steps: synonym normalization, keyword matching, and multi-level classification tree filtering.

First, synonym normalization standardizes different linguistic expressions to enhance fault tolerance during matching. Next, keyword matching and similarity measurement are used to identify potential candidate categories. Finally, a multi-level classification tree is applied to gradually filter categories from the bottom up, ensuring the selection of the most suitable candidate classification result.

Step 1: Synonym normalization is designed to address matching errors caused by differences in terminology. During the preprocessing stage, the system uses the Jieba tool to segment words in the WeChat Q&A data from 60 implemented tunnel projects. A manually verified synonym database is then used, combined with domain-specific vocabulary, to create a synonym mapping table. This allows colloquial expressions to be replaced with the system’s predefined standard keywords, significantly enhancing consistency and fault tolerance in terminology processing.

Step 2: During keyword matching, the cosine similarity between word vectors is calculated to determine the degree of match between the input word and the keywords at each classification level. When the cosine similarity is greater than or equal to a predefined threshold, the category is included in the candidate set.

Step 3: The multi-level classification tree is used for hierarchical filtering. The service event categories are predefined and arranged into three levels. As shown in Figure 5, the first- and second-level categories match the main and subcategories in Table 1, while the third-level categories detail specific service contents. For example, when the first-level category is Control Performance and the second-level category is Unreasonable Control Parameters, the third-level category must identify which control parameter, such as propulsion speed or sectional oil pressure, is involved.

Figure 5.

Multi-level classification tree structure. The dot “… …” in the diagram represents other third-level problem categories not shown.

The classification structure can be represented as:

{Level 1 Category: {Level 2 Category: [Level 3 Category]}}.

During pre-screening, the input text is sequentially compared with the third-level (R3), second-level (R2), and first-level (R1) keyword sets. M1, M2, and M3, respectively, represent the intersections between the input text and each keyword set. The decision logic is as follows:

- (1)

- If the input text intersects with R3 (i.e., M3 ≠ ∅), output the corresponding third-level category and verify that its second- and first-level paths are consistent.

- (2)

- If M3 = ∅ and M2 ≠ ∅, output the second-level category and label all third-level categories as “All.”

- (3)

- If only M1 ≠ ∅, output the first-level category and label both the second- and third-level categories as “All.”

- (4)

- If all intersections are empty, return “Unclassified.”

In summary, the Category Pre-screening module successfully classifies candidates accurately using a progressive hierarchical process that combines synonym normalization, keyword matching, and multi-level classification tree filtering.

4.2.2. RAG Module

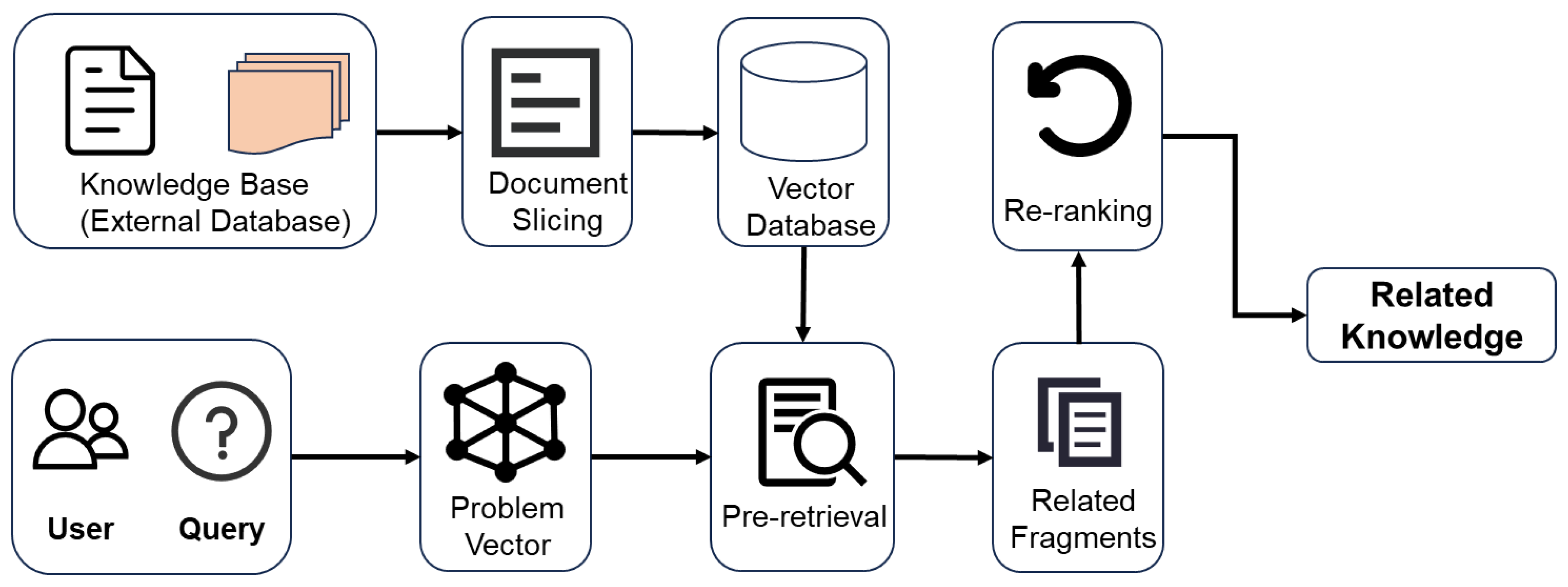

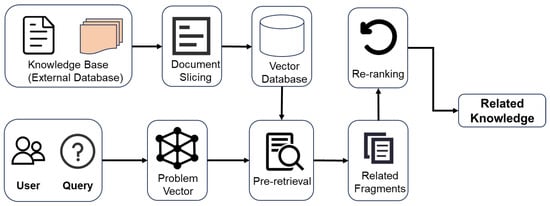

The module relies on an external knowledge base to provide the necessary domain-specific background information for supporting task classification and reasoning. The user input is first vectorized and then matched and ranked against the external knowledge base to retrieve candidate documents. These candidate documents are subsequently re-evaluated for precision, and the most relevant knowledge is selected. These related knowledge items are then passed to the LLM’s prompt, which generates the final answer. The implementation flow is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Knowledge base construction and retrieval mechanism process.

The knowledge base is the core foundation of the RAG module, providing essential domain-specific background information that supports task classification and reasoning. It mainly consists of two categories: problem cases and explanations of problem categories, as shown in Table 4. The problem case summaries in the knowledge base document classic examples of issues encountered during tunnel construction. Additionally, the knowledge base includes explanations for the three-level categories, which are based on over 100 pre-organized third-level categories, each with a detailed description. By integrating these data, the knowledge base not only offers comprehensive background for each candidate category but also provides rich domain context during retrieval to help the LLM generate more accurate answers.

Table 4.

Knowledge base examples.

The workflow of the RAG technology primarily includes the following steps:

- (1)

- Knowledge Base Vectorization: The content of the knowledge base is sliced into documents, and then each text slice is converted into a vector using the bge-large-zh-v1.5 pre-trained text vectorization model developed by the Beijing Academy of Artificial Intelligence. These vectors are then stored in a vector database. The model performs excellently in retrieval and semantic matching tasks [45].

- (2)

- Question Vectorization: Similarly, the user’s input question is vectorized using the bge-large-zh-v1.5 model.

- (3)

- Pre-retrieval: Cosine similarity is used to search for the most similar texts in the vector database. Cosine similarity measures the similarity between two vectors by calculating the cosine of the angle between them, as shown in Equation (1). Based on the similarity, the top-ranked text segments are selected as candidate documents.where represents the vector representation of the query text, and B represents the vector representation of the candidate text in the knowledge base. A ⋅ B denotes the dot product of the two vectors, while and represent the magnitudes of vectors A and B, respectively.

- (4)

- Re-ranking: To accurately identify and improve the ranking of truly relevant answers, the BGE-Reranker-Large model [45] is introduced after the initial retrieval results are obtained. This model performs fine-grained scoring of candidate documents based on features such as contextual relevance, task relevance, and knowledge richness. It then completes a secondary ranking of candidate segments, which are used in the LLM prompt to enhance the accuracy of the final retrieval.

4.2.3. LLM Prompt Design

The prompt design is a core component of the LLM classification module. Through the collaboration of multiple components and strong constraints, a precise classification instruction framework tailored to the tunnel construction domain is constructed. This framework guides the LLM to generate structured classification outputs. The design of the prompt not only affects classification accuracy but also determines the model’s efficiency in utilizing contextual information.

The objective of the prompt template design is to integrate the user’s query, the candidate categories output by the category pre-screening module, and the relevant knowledge retrieved from the knowledge base. This ensures that the LLM accurately understands the task requirements and generates classification results that align with expectations. The prompt consists of four components: role definition, candidate categories, relevant knowledge, and task requirements, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Prompt design.

4.3. Recognition Effect Evaluation

4.3.1. Experimental Design and Evaluation Method

Intention recognition is the core component of the intelligent assistant system, and its accuracy directly determines whether a user’s query is mapped to the corresponding task, thereby affecting subsequent decision support and the efficiency of human–machine collaboration. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, this study evaluates it using the 435 service events described in Section 3.1 as the test dataset.

- (1)

- Test Dataset: To ensure the generalizability and reliability of the experimental results, the dataset is expanded from the original 435 service events by adding 70 variations, including instructions with reversed word order, semantically ambiguous expressions, and inputs irrelevant to the task. These additions test the robustness of the classification method and evaluate whether the intelligent assistant can still accurately identify tasks under noisy or anomalous inputs.

- (2)

- Experimental Arrangement: To comprehensively verify the effectiveness of the SWLC method, multiple experiments were conducted. The first set of experiments compares the performance of different base LLMs, while the second set evaluates the impact of the category pre-screening and RAG methods on classification accuracy.

- (3)

- Evaluation Metrics: The evaluation metrics used in this study include Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and F1 Score, which are employed to assess the classification performance [46] comprehensively.

4.3.2. Comparison Experiment with Base Large Models

Table 6 presents the classification performance of different large base language models on the same task. The small-scale models (such as llama2-7b-chat [47], baichuan2-7b-chat [48], etc.) have accuracy rates below 25%, which fail to meet the requirements. Although Qwen1.5-72b [49] achieves 45.7% accuracy, its inference time exceeds 20 s, making it unsuitable for real-time scenarios. Considering both accuracy and response efficiency, Qwen1.5-32b [49] strikes the best balance between 44.6% accuracy and a response time of 4.80 s. Therefore, it was selected as the base model for subsequent experiments.

Table 6.

Comparison of task classification performance across base large models.

4.3.3. Classification Module Combination Experiment

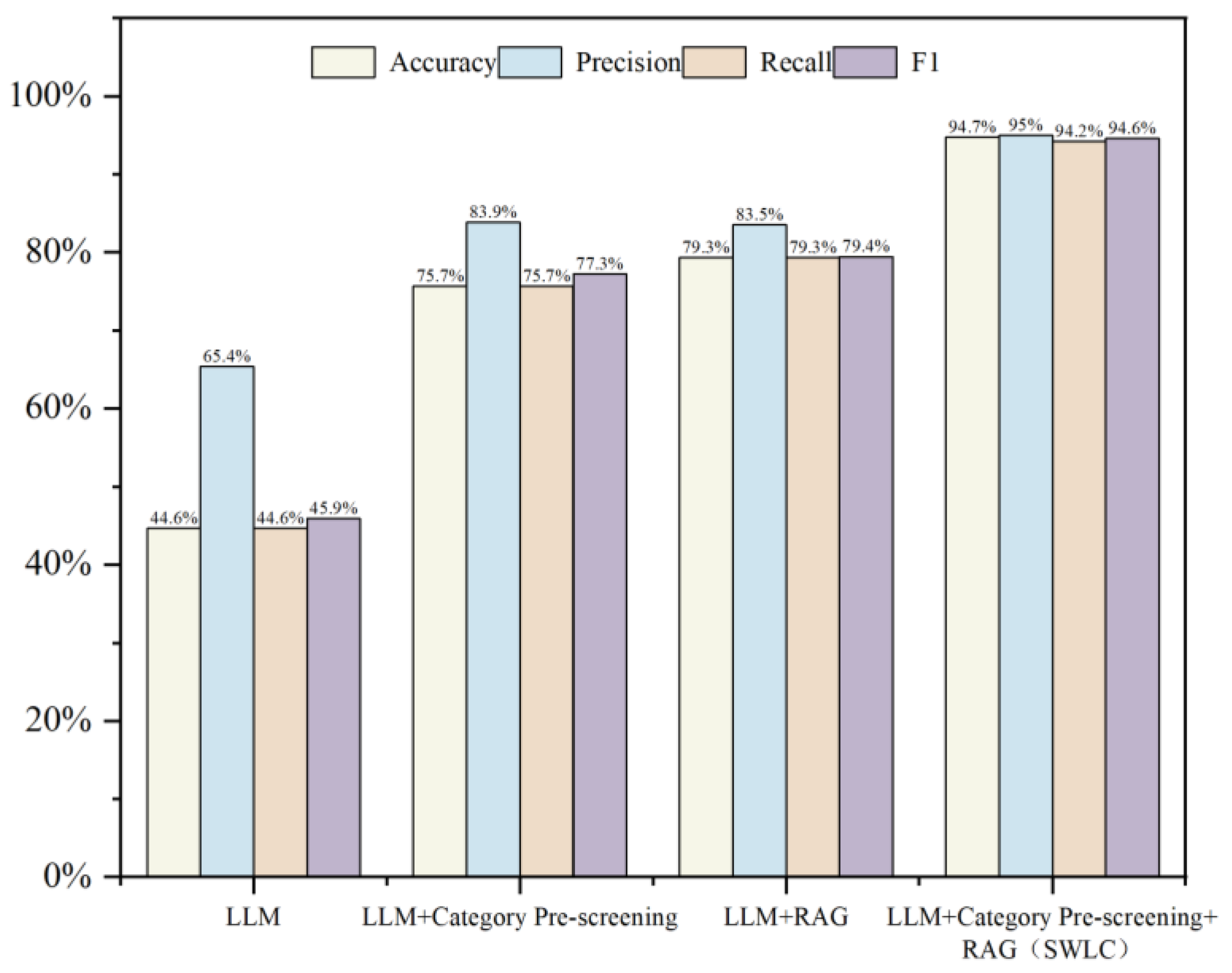

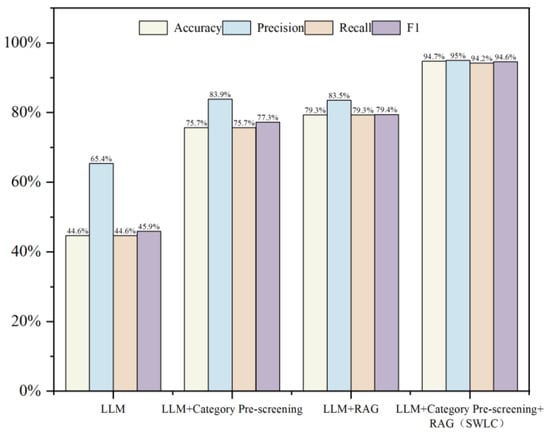

Using Qwen1.5-32b as the base model, experiments were conducted with various combinations of LLM, LLM + Category Pre-screening, LLM + RAG, and the proposed LLM + Category Pre-screening + RAG (SWLC) method. The classification results are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Accuracy of intention classification across different combinations.

As shown in Figure 7, the single LLM’s accuracy is only 44.6% and its F1 score is 45.9%, failing to meet the high reliability requirements for task classification. After introducing rule-based classification, the accuracy improved to 75.7%, indicating that the rule-based method effectively narrows the candidate range and increases stability. When combined with the RAG technique, accuracy increased to 79.3% and the F1 score to 79.4%, demonstrating that integrating external knowledge enhances the model’s ability to make judgments in complex contexts. The SWLC method is the most effective, achieving 94.7% accuracy and an F1 score of 94.6%, significantly outperforming the single LLM, LLM + Rule Classification, and LLM + RAG methods.

4.3.4. Robustness Verification

To further validate the robustness of the SWLC method, this paper introduces 70 additional adversarial test cases to the original dataset, including types such as inverted command syntax, ambiguous expressions, and irrelevant statements. Experimental results for these 70 specialized test cases demonstrate that the LLM + category pre-screening + RAG intent matching mechanism achieved 100% accuracy on the test set. All disruptive inputs were correctly identified, with the system effectively recognizing task-relevant content while ignoring invalid information. For completely irrelevant or erroneous statements, the system promptly provided clear feedback and classified them as “irrelevant issues,” preventing the triggering of incorrect tasks. Table 7 presents the experimental results for several types of disruptive inputs. The system provides clear feedback by classifying the inputs, ensuring that tasks remain unaffected by irrelevant information.

Table 7.

Robustness examples under attack intents.

5. Engineering Application

5.1. Implementation of the Intelligent Assistant

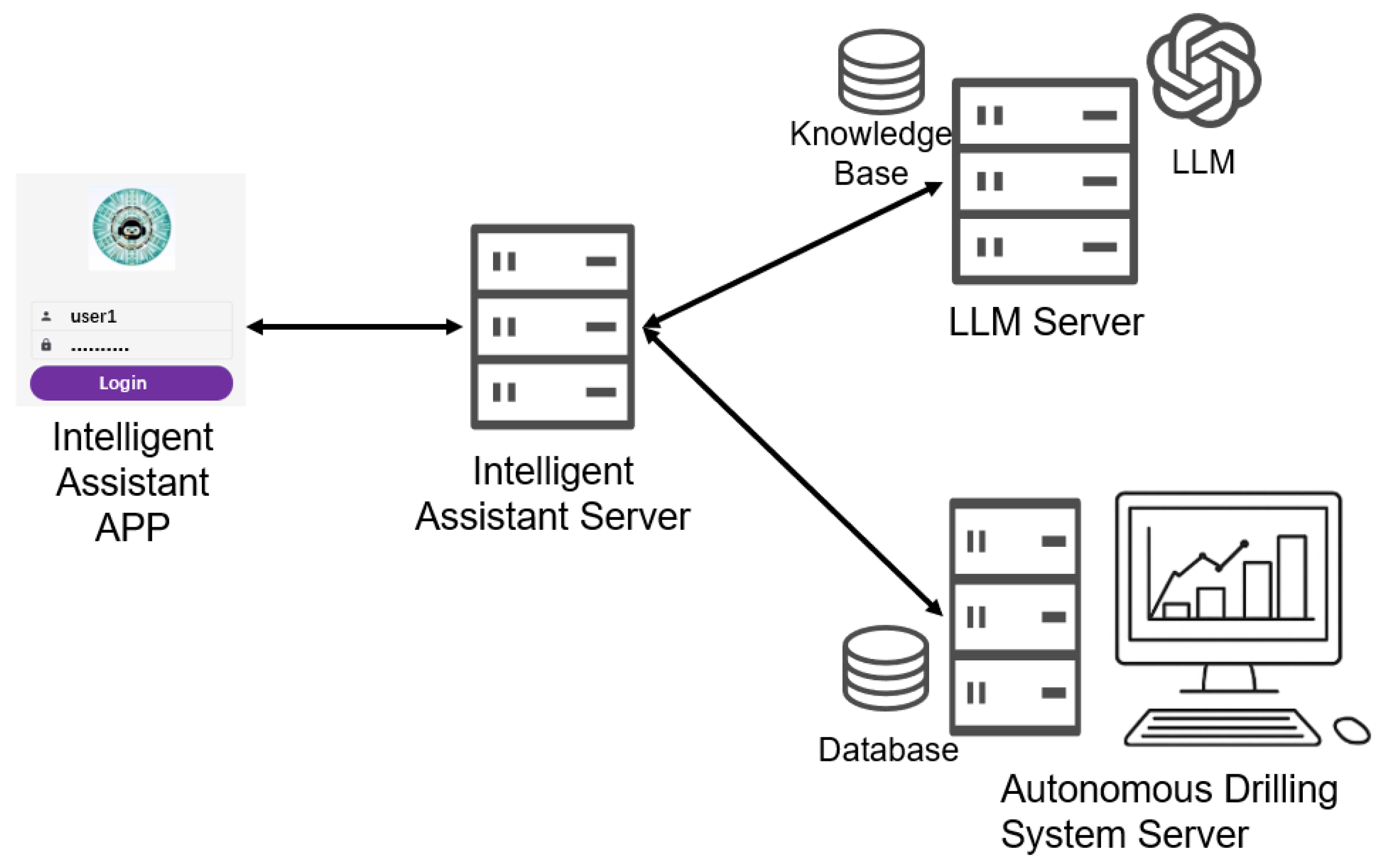

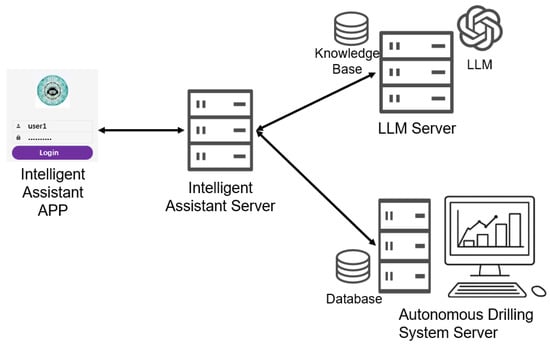

The human–machine collaboration service model proposed in this paper has been developed into a mobile application and deployed in two tunnel projects on Shanghai Metro Line 12, Sections 1 and 3, which use the ZATS to improve system performance. The intelligent assistant adopts a “light client + middle platform service” architecture: the mobile app serves as the front-end, with all functionalities provided by back-end services. The system’s physical topology is shown in Figure 8. The intelligent assistant app is responsible for the user interface, collecting user input, and displaying the assistant’s response, but it does not directly connect to the autonomous tunneling system. Instead, it communicates with the LLM server and the autonomous tunneling system server via the intelligent assistant server to handle tasks such as intention recognition and task execution.

Figure 8.

Physical topology of the system.

Currently, the intelligent assistant has processed 387 service events, with a response time of only 4.5 s, significantly lower than the response time of manual remote services. To assess the practical effectiveness of the intelligent assistant system in field construction, a survey was conducted. A total of 48 questionnaires were distributed to tunnel drivers and project managers. 93.8% of drivers believed that the assistant system significantly reduced cognitive load and improved decision-making efficiency. In comparison, 87.5% of project managers considered the system to have good field adaptability and engineering value.

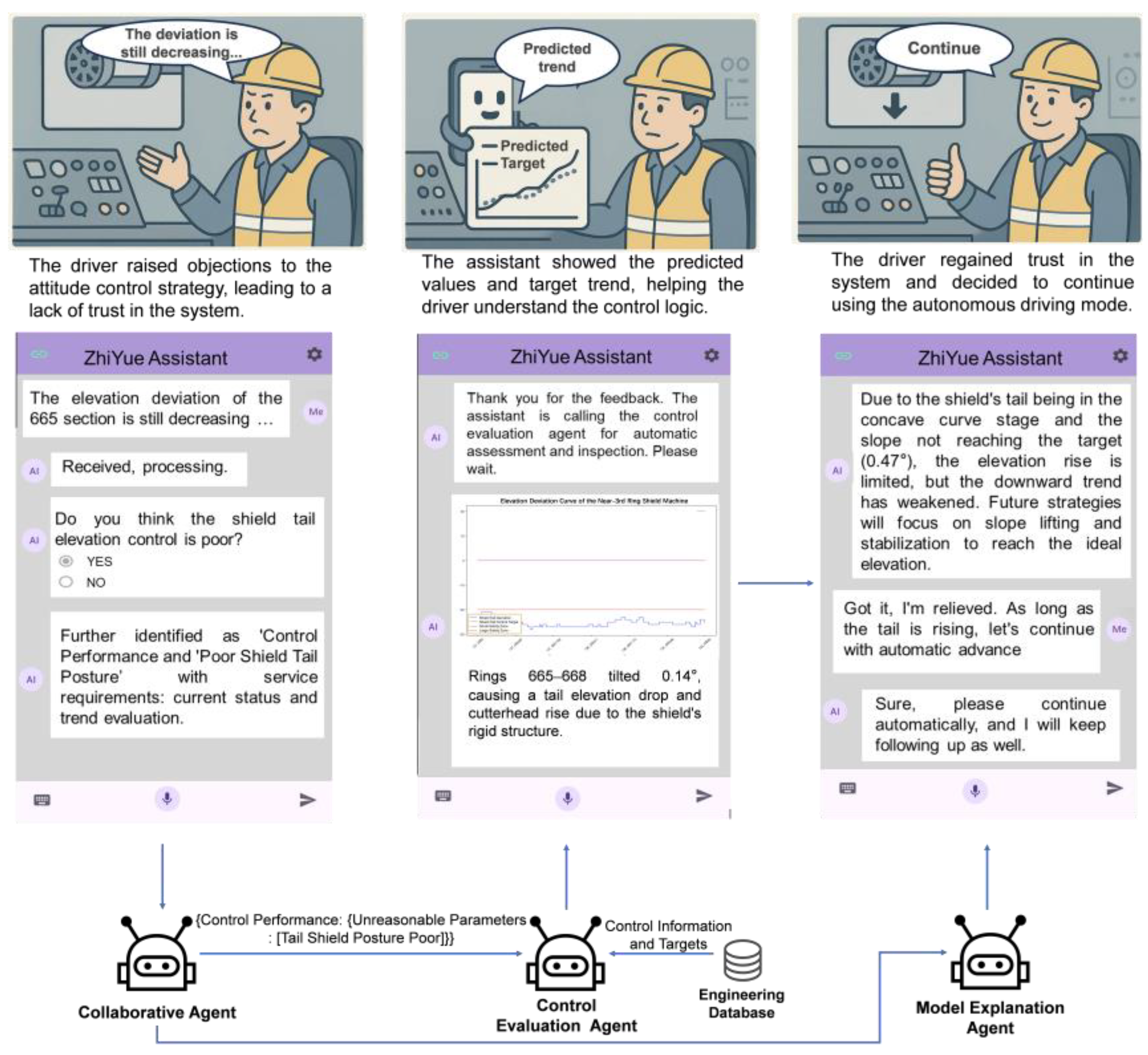

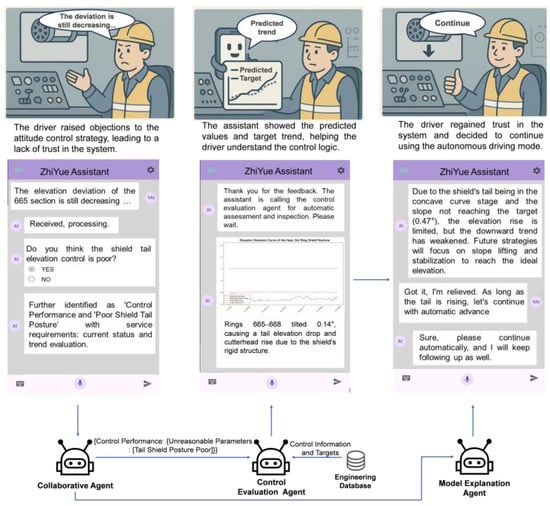

5.2. Case Analysis 1: Enhancing System Transparency and Increasing User Trust

During the tunneling operation of Section 1, Line 21, the tunneling machine’s advancement strategy was adjusted in response to changes in geological conditions. The driver questioned the posture control strategy of the autonomous tunneling system, stating, “When the 665 ring started advancing automatically, the elevation was still dropping. This doesn’t seem right, does it?” The driver believed that the system had failed to accurately assess the position of the shield tail, leading to a lack of trust in the system. The driver’s doubts primarily stemmed from a lack of understanding of the system’s prediction and control decisions, particularly under the adjustments made to the advancement strategy due to geological changes, resulting in diminished confidence in the automated system.

As shown in Figure 9, when the driver raised the concern, the intelligent assistant called upon the collaborative agent to categorize the task and confirm that the issue belonged to the “control performance” category. It was further classified as a “poor shield tail posture” subcategory and identified as an evaluation-type task. The intelligent assistant then invoked the control evaluation agent, which retrieved control information and target data from the autonomous tunneling system, providing relevant parameters such as posture, along with predicted values and target trend charts. Next, the model explanation agent was triggered to clarify: “Currently, the shield tail is still in the concave curve stage of the design axis, and the tunneling slope has not yet reached the target slope. Therefore, the shield tail elevation lifting effect is not obvious, but the downward trend at the tail has weakened. Due to changes in geological conditions and uneven soil, the tunneling machine’s advancement strategy was adjusted. The subsequent elevation strategy mainly focuses on ramp lifting and stable slope progression, gradually raising the tail elevation to the desired control range.” This explanation resolved the driver’s concerns, and they continued using the model for automatic propulsion.

Figure 9.

The control process of posture control dispute.

This process effectively alleviated the mode switching caused by factors such as insufficient driver trust, low system transparency, and safety concerns, reducing unnecessary manual intervention and improving the stability of the automated mode. By proactively providing model explanations and data visualizations, the intelligent assistant enhanced system transparency and boosted the driver’s trust, thereby improving the efficiency of human–machine collaboration.

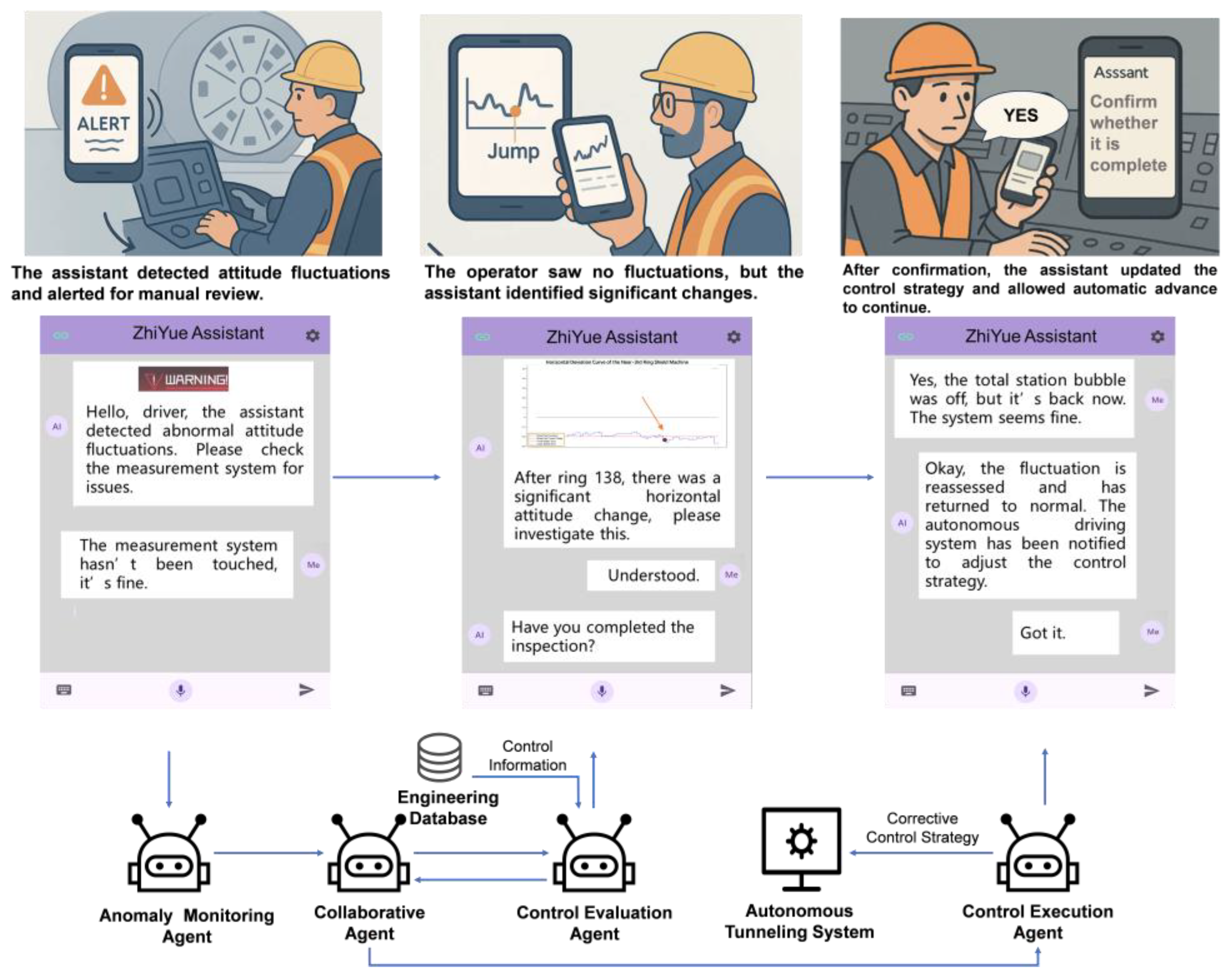

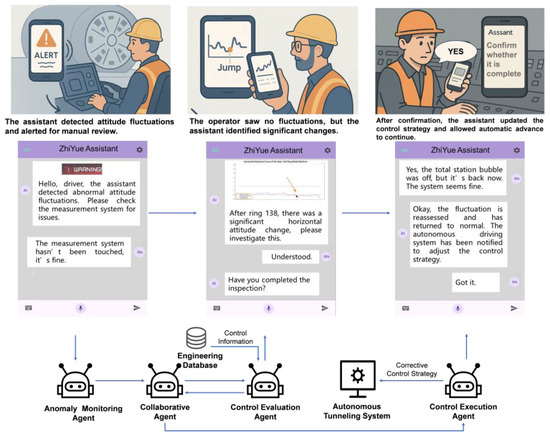

5.3. Case Analysis 2: Bridging the Human–Machine Information Gap to Enhance System Safety

On April 17, 2025, during tunneling for Section 3, Line 12 in Shanghai, the intelligent assistant detected abnormal posture fluctuations and requested an on-site inspection of the measurement system. Before the system’s alert, the driver had not noticed the fluctuation, resulting in an information gap. Upon receiving the system’s prompt, the driver confirmed the fluctuation’s existence, which immediately increased their awareness and trust in the system’s safety, thereby strengthening their reliance on the system’s judgment. This process effectively eliminated the information asymmetry and enhanced the sense of safety within the system.

As shown in Figure 10, the intelligent assistant detects abnormal posture fluctuations through the Anomaly monitoring agent and immediately provides feedback to the user. It then invokes the collaborative agent to classify the task based on the anomaly alert, categorizing it under “System Alert” in the “Posture Anomaly” subcategory, and confirms that the task type is a monitoring task. Next, the control evaluation agent is called, and the posture jump graph is displayed to the user with the explanation: “After reaching ring 138, a significant change in horizontal posture occurred in this segment, which needs to be inspected first.” Once the verification is completed, the control execution agent is invoked to notify the autonomous driving system to adjust the control strategy. After resuming automatic propulsion, posture monitoring is repeated, and the system reports that posture is now normal, allowing continuous automatic propulsion. Through proactive communication and real-time feedback, the intelligent assistant effectively reduces the information gap between the driver and the system, enhancing the driver’s trust in the system and improving its safety and reliability.

Figure 10.

The control process of abnormal posture fluctuations.

An analysis of these two cases shows that the intelligent assistant plays a crucial role in tunnel construction. By increasing system transparency, the assistant enhances the driver’s trust and reduces unnecessary manual intervention, ensuring the efficiency of system automation. At the same time, through effective communication and feedback, the assistant reduces the information asymmetry between the human and the machine, thereby improving the system’s safety.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the frequent manual control interventions during autonomous tunneling operations by proposing and implementing an intelligent assistant system designed for human–machine collaboration. Through analysis of on-site data and interaction logs, the research identifies the typical challenges operators face when using autonomous tunneling systems. It establishes the mapping relationship between “control performance issues,” “system operation issues,” and “information communication issues” across six task categories, uncovering the root causes of automatic mode switching.

Based on these findings, a multi-agent intelligent assistant architecture integrating category pre-screening, RAG retrieval, and large language models was designed and developed. This system provides comprehensive functional support for various tasks, including evaluation, explanation, execution, monitoring, information acquisition, and system introduction.

Task classification experiments conducted on typical engineering corpora demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a classification accuracy of 94.7%, showing strong robustness and generalization capability in multi-category task recognition and significantly outperforming other benchmark models.

Engineering application results confirm that the assistant significantly improves task recognition accuracy and execution efficiency, reduces the frequency of manual control interventions, alleviates operator stress, and enhances system transparency and trustworthiness, thereby achieving a higher level of human–machine collaboration.

In conclusion, the proposed intelligent assistant serves not merely as an auxiliary tool for autonomous tunneling systems but functions as a collaborative hub connecting operators, tunneling systems, and TBM equipment. Its design and validation provide new theoretical and practical references for the intelligent development of tunnel construction, as well as innovative solutions for the thoughtful maintenance of underground infrastructure in smart city development. In complex and dynamically changing construction environments, the intelligent assistant can help the driver better understand system decisions and environmental changes through its built-in explanatory intelligent agents, thereby enhancing the driver’s trust in the system and ensuring the smooth automation of tunneling operations. Furthermore, while the intelligent assistant is currently deployed specifically for human–machine interaction (HMI) in the autonomous operation of shield tunneling machines, its core design, encompassing intention recognition and multi-agent collaboration architecture, renders it equally applicable to HMI scenarios across automation processes in other domains. With continuous technological advancement, its use cases are expected to expand far beyond tunneling operations to cover smart building management, infrastructure maintenance, and more, thereby enhancing cross-domain applicability. The assistant functions as a reliable mediator in HMI workflows: it accurately interprets user requirements, dynamically adjusts its knowledge base and toolkits to meet domain-specific needs, and delivers real-time support to ensure efficient system operation. Although the explanatory tools and methodologies may vary across different application contexts, its core functionality remains centered on task execution and real-time feedback.

Looking ahead, as AI technologies, such as multimodal foundation models, edge-intelligent sensing, and adaptive digital twins, continue to advance, human–AI collaboration will become even more seamless and practical. For instance, in safety, the intelligent assistant acts as a vigilant “co-pilot,” continuously analyzing geological, mechanical, and environmental data to detect emerging risks while clearly explaining their root causes and potential evolution, empowering on-site teams to intervene with precision and confidence. In sustainability, it functions as a strategic advisor, helping balance operational efficiency with ecological responsibility by recommending resource-efficient excavation routes, energy-optimized equipment scheduling, and low-carbon material alternatives, all presented as actionable, human-reviewable proposals. In smart operations and maintenance, the assistant proactively anticipates equipment wear or performance degradation through real-time sensor analytics and delivers tailored mitigation strategies. Critically, its recommendations remain transparent and contestable, ensuring that human operators retain ultimate oversight and decision authority.

Most importantly, future advancements will prioritize not only technical capabilities but also trustworthiness, adaptability, and communication clarity. By aligning with operators’ cognitive workflows, dynamically adjusting to different user roles (e.g., trainee vs. expert), and delivering context-aware insights, the assistant is poised to excel across tunneling and beyond, extending its value to smart buildings, infrastructure networks, and other complex engineered systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H., H.G. and Q.M.; methodology, M.H., H.G. and B.W.; software, H.G. and J.L.; validation, M.H., H.G. and Q.M.; formal analysis, M.H.; investigation, H.G., B.W. and Y.L.; resources, M.H.; data curation, Q.M. and Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H. and H.G.; writing—review and editing, B.W. and J.L.; visualization, H.G.; supervision, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In preparing this article, the authors used OpenAI’s GPT-5 to draw icons, enhance language, and improve readability. AI software was employed to improve grammar, clarity, and readability. However, the authors ensured that the original ideas, analysis, and conclusions were fully maintained. The responsibility for all substantial elements of the work, including research design, methodology, data analysis, and intellectual contributions, rests solely with the authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, X.; Fu, Y.; Chen, X.; Xiao, H.; Bao, X.; Pang, X.; Wang, X. Advances in Underground Space Construction Technology and the Current Status of Digital and Intelligent Technologies. China J. Highw. Transp. 2022, 35, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.L.J.; Shen, S.L.K.; Batty, R.J.; Ho, J.C.J. The pursuit of an autonomous tunnel boring machine. In Proceedings of the ITAAITES World Tunnel Digital Congress and Exhibition (WTC) 2020 and the 46th General Assembly, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 9 November 2020; pp. 139–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, M.; Wu, B.; Zhou, W.; Wu, H.; Li, G.; Lu, J.; Yu, G.; Qin, Y. Self-driving shield: Intelligent systems, methodologies, and practice. Autom. Constr. 2022, 139, 104326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Hong, K.; Gao, P.; Li, F.; Li, S.; Zhao, X. Status quo and prospects of tunnel intelligent construction in China. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 43, 549. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, M.; Li, G.; Hu, M. Design and application of performance evaluation system for self-driving shields. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 43, 1872–1886. [Google Scholar]

- Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Hu, M.; Gan, L. Literature Review on Human Factors involved in Intelligent Shield Construction. Tunn. Constr. 2023, 8, 1269–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, T.A.; Khan, A.; Hallock, H.; Beltrão, G.; Sousa, S. A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: An HCI perspective. Int. J. Hum.—Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1251–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Sepanloo, K.; Woo, S.; Woo, S.H.; Son, Y.J. A review of the industry 4.0 to 5.0 transition: Exploring the intersection, challenges, and opportunities of technology and human–machine collaboration. Machines 2025, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupas, M.; Kajati, E.; Liu, C.; Zolotova, I. Towards a human-centric digital twin for human–machine collaboration: A review on enabling technologies and methods. Sensors 2024, 24, 2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyacı, T.; Canyakmaz, C.; De Véricourt, F. Human and machine: The impact of machine input on decision making under cognitive limitations. Manag. Sci. 2024, 70, 1258–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, R.S.; Marcu, A.; Neerincx, M.A.; Tielman, M.L. The influence of interdependence on trust calibration in human-machine teams. In Proceedings of the HHAI 2024: Hybrid Human AI Systems for the Social Good, Malmö, Sweden, 10–14 June 2024; pp. 300–314. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, H.; Han, Q.L.; Ge, X.; Ding, L.; Xu, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, D. Fault-tolerant cooperative control of multiagent systems: A survey of trends and methodologies. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 16, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Wang, K.; Li, L.; Luo, X.; Lo, D.; Grundy, J.; Wang, H. Large language models for software engineering: A systematic literature review. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2024, 33, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Y. A review of human–machine cooperation in the robotics domain. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2021, 52, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleiger, E.; Mason, C.; Naughtin, C.; Reeson, A.; Paris, C. Collaborative Intelligence: A Scoping Review of Current Applications. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 2327890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaccaro, M.; Almaatouq, A.; Malone, T. When combinations of humans and AI are useful: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2024, 8, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Hang, P.; Lou, S.; Lv, C. Human–machine cooperative decision-making and planning for automated vehicles using spatial projection of hand gestures. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Sun, B.; Zhang, B.; Pang, Z.; Peng, Z.; Yang, S.; Cao, Y. CO-Mode with AV-CRM: A novel paradigm towards human–machine collaboration in intelligent vehicle safety. J. Saf. Sci. Resil. 2025, 7, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Huang, C.; Lv, C. Driver-Automation Collaboration for Automated Vehicles: A Review of Human-Centered Shared Control. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 19 October–13 November 2020; pp. 1964–1971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cominelli, L.; Feri, F.; Garofalo, R.; Giannetti, C.; Meléndez-Jiménez, M.A.; Greco, A.; Nardelli, M.; Scilingo, E.P.; Kirchkamp, O. Promises and trust in human–robot interaction. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippi, M.; Martinelli, M.; Picone, M.; Zambonelli, F. Enabling causality learning in smart factories with hierarchical digital twins. Comput. Ind. 2023, 148, 103892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, T.; Kim, S. Improving trust in AI with mitigating confirmation bias: Effects of explanation type and debiasing strategy for decision-making with explainable AI. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 8562–8573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adami, P.; Rodrigues, P.B.; Woods, P.J.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Soibelman, L.; Copur-Gencturk, Y.; Lucas, G. Impact of VR-based training on human–robot interaction for remote operating construction robots. J. Comput. Civ. Eng. 2022, 36, 04022006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Yue, L.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, O.; Zaki, M.H. Investigating the Effects of Human–Machine Interface on Cooperative Driving Using a Multi-Driver Co-Simulation Platform. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 2808–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, F.; Liang, Y.; Fu, Q.; Zhang, J. Exploring the Role of AR Cognitive Interface in Enhancing Human-Vehicle Collaborative Driving Safety: A Design Perspective. Int. J. Hum.—Comput. Interact. 2025, 41, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, J.; Tang, P.; Zhou, S.; Peng, X.; Li, H.N.; Wang, Q. Exploring Personalized Autonomous Vehicles to Influence User Trust. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 1170–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, T.; Huang, Z.; Xing, Y.; Chen, S. Personalizing Driver Agent Using Large Language Models for Driving Safety and Smarter Human–Machine Interactions. IEEE Intell. Transp. Syst. Mag. 2025, 17, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Liu, J.; Ding, M.; Cui, Y.; Lv, C.; Hang, P.; Sun, J. Towards interactive and learnable cooperative driving automation: A large language model-driven decision-making framework. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 11894–11905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Jianjun, H.; Jabbar, A. Recent Advances in Federated Learning for Connected Autonomous Vehicles: Addressing Privacy, Performance, and Scalability Challenges. EEE Access 2025, 13, 80637–80665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, H. Effect of Proactive Interaction on Trust in Autonomous Vehicles. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, J.; Luximon, Y. Interface design for visual blind spots in cooperative driving. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2025, 44, 4906–4924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woide, M.; Stiegemeier, D.; Pfattheicher, S.; Baumann, M. Measuring driver-vehicle cooperation: Development and validation of the Human-Machine-Interaction-Interdependence Questionnaire (HMII). Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 83, 424–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rony, M.R.A.H.; Suess, C.; Bhat, S.R.; Sudhi, V.; Schneider, J.; Vogel, M.; Teucher, R.; Friedl, K.E.; Sahoo, S. CarExpert: Leveraging Large Language Models for In-Car Conversational Question Answering. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.09536. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. Design of Intelligent Question-Answering System Based on Large Language Model. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 261, 734–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garello, L.; Belgiovine, G.; Russo, G.; Rea, F.; Sciutti, A. Building Knowledge from Interactions: An LLM-Based Architecture for Adaptive Tutoring and Social Reasoning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.01588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yu, J.; Peng, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Yoo, J.; Chunag, S.; Lee, D.; Ji, D.; Zhang, C. MoSE: Skill-by-Skill Mixture-of-Expert Learning for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07818. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, X.; Wu, C.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, G.; Pu, Y.; Lei, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; et al. When large language models meet personalization: Perspectives of challenges and opportunities. World Wide Web 2024, 27, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, X.; Xu, Z.; Lim, S.; Zhao, H. LARM: Large Auto-Regressive Model for Long-Horizon Embodied Intelligence. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.17424. [Google Scholar]

- Du, H.; Feng, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; Tao, S.; Zhong, Y.; Li, Y.-F.; Wang, H. Towards proactive interactions for in-vehicle conversational assistants utilizing large language models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.09135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lian, J.; Lei, Y.; Yao, J.; Lian, D.; Xie, X. Recommender AI Agent: Integrating Large Language Models for Interactive Recommendations. ACM Trans. Inf. Syst. 2025, 43, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, X.C.; Lu, L.; Wang, B.; Liu, C. A Self-Supervised Multi-Agent Large Language Model Framework for Customized Traffic Mobility Analysis Using Machine Learning Models. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Q.; Wang, M.; Zhang, T.; Huang, H. Current trends and future prospects of large-scale foundation model in K-12 education. Front. Digit. Educ. 2025, 2, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Zhou, W.; Hu, M.; Chew, C.M. A meta-learning enhanced framework for prediction and control of shield-tunneling-induced ground deformation under data scarcity. Transp. Geotech. 2025, 56, 101779. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Chang, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Li, G. Machine learning-based automatic control of tunneling posture of shield machine. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2022, 14, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, P.; Muennighoff, N.; Lian, D.; Nie, J.Y. C-pack: Packed resources for general Chinese embeddings. In Proceedings of the 47th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval 2024, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 July 2024; pp. 641–649. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolova, M.; Lapalme, G. A systematic analysis of performance measures for classification tasks. Inf. Process. Manag. 2009, 45, 427–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touvron, H.; Martin, L.; Stone, K.; Albert, P.; Almahairi, A.; Babaei, Y.; Bashlykov, N.; Batra, S.; Bhargava, P.; Bhosale, S.; et al. Llama 2: Open foundation and fine-tuned chat models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Xiao, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, B.; Bian, C.; Yin, C.; Lv, C.; Pan, D.; Wang, D.; Yan, D.; et al. Baichuan 2: Open large-scale language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.10305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Bai, S.; Chu, Y.; Cui, Z.; Dang, K.; Deng, X.; Fan, Y.; Ge, W.; Han, Y.; Huang, F.; et al. Qwen technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.16609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).