Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Behavioral savings are fragile, and window-opening significantly erodes the 9.8% gain from conservation nudges, reducing it to 7.6%.

- Occupancy-based automation cuts heating demand by 12.9% by avoiding heating during unoccupied periods.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- Decarbonization strategies should shift away from complex, user-dependent algorithms toward “set-and-forget” occupancy automation that reliably anchors lower thermal baselines and eliminates waste.

- This physics-informed framework can be coupled with survey data to validate model parameters, design discrete choice experiments, and create more realistic representations of occupancy behavior and user motivations.

Abstract

Smart thermostats are a key technology for reducing residential energy consumption in smart cities, but their real-world effectiveness depends on the interaction between automation, occupant behavior, and the design of behavioral interventions. This study presents a physics-informed assessment of thermostat strategies across Luxembourg’s single-family home stock, using an aggregate thermal model calibrated to eight years of hourly national heating demand and meteorological data. We simulate five categories of behavioral scenarios: dynamic thermostat adjustments, heat-wasting window-opening behavior, flexible comfort models, occupancy-based automation, and a portfolio of four probabilistic nudges (social comparison, real-time feedback, pre-commitment, and gamification). Results show that occupancy-based automation delivers the largest energy savings at 12.9%, by aligning heating with presence. In contrast, behavioral savings are highly fragile, as a stochastic window-opening behavior significantly erodes the 9.8% savings from eco-nudges, reducing the net gain to 7.6%. Among nudges, only social comparison yields significant savings, with a mean reduction of 7.6% (90% confidence interval: 5.3% to 9.8%), by durably lowering the thermal baseline. Real-time feedback and pre-commitment fail, achieving less than 0.5% savings, because they are misaligned with high-consumption periods. Thermal comfort, the psychological state of satisfaction with the thermal environment drives a large share of residential energy use. These findings demonstrate that effective smart thermostat design must prioritize robust, presence-responsive automation and interventions that reset default comfort norms, offering scalable, policy-ready pathways for residential energy reduction in urban energy systems.

1. Introduction

Buildings are central to climate change mitigation, and the decarbonization of residential space heating represents a critical global challenge. While deep physical retrofits are essential for long-term solutions, they are often slow, expensive, and disruptive. Meeting near-term climate targets therefore requires the immediate deployment of all available levers, including low-cost, scalable interventions that engage in occupant behavior. Thermal comfort the psychological state of satisfaction with the thermal environment drives a large share of residential energy use [1,2]. This is not a passive condition but an active, adaptive process in which occupants continuously adjust their surroundings to maintain comfort [3,4,5]. Understanding this dynamic is essential for designing human-centered strategies that can deliver rapid energy reductions.

A persistent Energy Performance Gap (EPG) exists between predicted and actual building energy consumption, largely due to oversimplified assumptions about occupant behavior. Physical building characteristics alone often fail to explain most variation in real energy consumption, underscoring the need to integrate realistic behavioral models into energy analysis.

This challenge has created tension in the literature, particularly around smart thermostats, which have become a key technology in residential energy management. It is important to note that a “smart building” is not defined solely by controls but also by adaptive envelope technologies that interact with the environment [6]. However, in existing housing stocks where deep retrofits are costly, smart thermostats often represent the most accessible initial layer of this intelligence. The research landscape for these devices has largely evolved along two parallel, yet distinct, paths: (1) “bottom-up” behavioral analysis, leveraging large-scale datasets to understand individual user actions; and (2) “top-down” control theory, focusing on advanced algorithms to aggregate thermostats for grid services [7].

The first path, driven by large datasets like the “Donate Your Data” (DYD) program, has robustly quantified occupant behavior. This data confirms that occupants demonstrate significant intentionality toward energy savings, with studies finding 83% of users program their thermostats, setting substantial heating setbacks of 3.8 °C relative to their occupied “Home” setpoint [8]. Occupants are known to override automated schedules [9], and nearly 39% of Demand Response (DR) events are ‘adjusted’ by users. These interventions are typically intentional efforts to restore immediate thermal comfort in response to rigid or misaligned automated schedules [10,11], yet they can lead to a net increase in energy use.

The second path treats thermostats as Thermostatically Controlled Loads (TCLs) to be aggregated for power system management [12]. This field is dominated by the development of complex control strategies, such as Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Reinforcement Learning (RL), to optimize setpoints based on weather forecasts, price signals, and real-time grid conditions [13,14]. While these “smart” algorithms show potential, this research focuses almost exclusively on the technical sophistication of the control algorithm itself, often overlooking simpler, non-algorithmic strategies. This study’s relevance extends beyond Europe, aligning with global “Net Zero” targets [11] and mandatory efficiency policies in Asian markets like China [15]. In North America, smart thermostat adoption is projected to exceed 43 million households [8], while large-scale U.S. field experiments confirm the impact of behavioral interventions [16]. This global proliferation underscores a universal challenge: balancing automation potential with the reality of occupant behavior.

This creates a research gap: the behavioral field provides deep, granular insights, while the controls field focuses on optimizing complex algorithms, but few studies use a unified, physics-informed model to quantitatively rank these competing strategies against each other [3,7,17].

What is missing is a physics-informed, computationally tractable framework that integrates realistic behavioral dynamics with validated thermal physics not to predict individual actions, but to quantify the aggregate energy impact of specific, policy-relevant interventions such as smart thermostats, digital nudges, and occupancy-based automation. Such a framework must be grounded in empirical data, yet flexible enough to test the robustness of behavioral strategies under uncertainty.

This study addresses this gap by applying a novel hybrid modeling approach to Luxembourg’s single-family home (SFH) stock. While Luxembourg’s high gross domestic product (GDP) per capita presents a unique socio-economic context, several of its physical and structural characteristics make it a compelling analog for a compact, data-rich smart city [18]. Its high degree of urbanization (with over 92% of the population classified as urban [19,20,21]), and small geographical footprint resemble a dense city-state, and its centralized national energy data infrastructure provides the high-resolution, aggregated data that is an ambition for many urban areas. Furthermore, its building stock is largely representative of archetypes found throughout Central Europe, situated within a heating-dominated climate typical for the region [19]. These factors make it a valuable case study for a systems-level analysis of interventions whose physical impacts can offer transferable insights, even if the specific economic drivers of behavior may vary in other contexts. In addition, this work directly supports the survey-based or experimental studies, e.g., “LetzPower” initiative’s objective to identify high-impact, scalable demand-side flexibility measures for Luxembourg’s residential heating sector [20].

We combine a calibrated lumped-parameter thermal model validated against eight years of national heating demand with a portfolio of dynamic behavioral scenarios representing real-world smart thermostat features and behavioral interventions. These scenarios are not arbitrary assumptions; they are explicitly grounded in empirical data. Occupancy patterns, for example, are generated from representative national Time Use Surveys (TUS), and the impact of behavioral nudges is modeled using median effect sizes derived from large-scale experimental field studies (e.g., [16]). Rather than modeling every household, we treat the SFH stock as a single thermal entity, enabling rapid, reproducible assessment of intervention efficacy at scale.

Our research is guided by four policy-oriented research questions (RQ):

- What is the energy-saving potential of low-cost thermostat strategies, such as setbacks and occupancy-based heating?

- Which digital behavioral nudges, such as social comparison or real-time feedback, are most effective and resilient to probabilistic user responses?

- How do these interventions interact with the physical thermal dynamics of the building stock?

- What is the national-scale energy reduction potential if these strategies are widely adopted?

By answering these questions with quantitative rigor, this work delivers a transparent, evidence-based ranking of This study investigates not only which interventions are effective, but why, proposing a new concept: “intervention architecture.” We define this as the alignment of an intervention’s mechanism (e.g., a trigger or setpoint change) with periods of high physical energy consumption. We hypothesize this alignment is a more critical determinant of success than its psychological framing alone.

2. Methodology

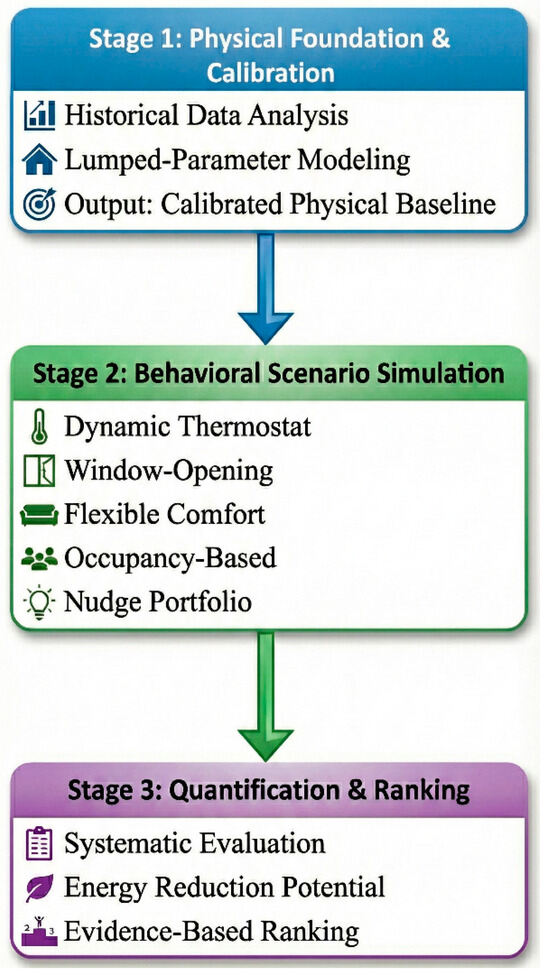

The research methodology, illustrated in the flowchart in Figure 1, is structured around three core stages that connect the physical building stock to the impacts of human behavior. This approach ensures that the analysis is both grounded in real-world physics and relevant for policy design. The three stages are: establishing a Physical Foundation, simulating a portfolio of behavioral Scenarios, and performing a final Quantification and Ranking.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the physics-informed behavioral modeling framework. (1) a calibrated lumped-parameter thermal model of Luxembourg’s single-family home stock, (2) simulation of five policy-relevant behavioral scenarios, (3) quantification of energy reduction potential.

- Physical Foundation: The first stage establishes a robust physical baseline for the analysis. This is achieved by developing a lumped-parameter thermal model representing the aggregate single-family home stock. The model is calibrated through a comprehensive historical data analysis of eight years of real-world hourly heating demand and temperature data, ensuring all subsequent scenarios are tested against a physically consistent and validated foundation.

- Behavioral Scenarios: Building on this physical model, the second stage involves the simulation of five distinct categories of behavioral interventions. These scenarios are designed to explore the impact of different human actions and policies, including: (1) Thermostat Adjustments like night setbacks; (2) wasteful Window-Opening Behaviors; (3) Thermal Comfort Strategies that allow for flexible setpoints; (4) Occupancy-Based Thermostats that link heating to real-time presence; and (5) a Nudge Portfolio. The framework also incorporates Monte Carlo Simulations as a key technique to analyze the uncertainty and probabilistic outcomes within these nudge-based policies (Scenario 5).

- Quantification and Ranking: In the final stage, the outputs from the behavioral scenarios are systematically evaluated. The energy reduction potential for each intervention is calculated in absolute (GWh/year) and relative (%) terms to determine the aggregate national impact. This process provides a clear, evidence-based ranking of behavioral interventions by their overall effectiveness and potential contribution to climate.

To evaluate the real-world potential of smart thermostat strategies, we simulate five behavioral scenarios that span user-driven, technology-enabled, and policy-oriented interventions. These scenarios are designed to test distinct behavioral mechanisms rather than to quantify savings at this stage. Scenario 1 (Dynamic Thermostat) establishes a behavioral baseline by comparing a standard programmable schedule with a deeper, pre-programmed “eco-mode.” Scenario 2 (Window-Opening) introduces stochastic ventilation losses to probe the fragility of thermostat-based savings. Scenario 3 (Flexible Comfort) examines whether algorithmic sophistication dynamic setpoints responding to weather or price improves efficiency and contrasts it with an anchored algorithm variant that maintains a lower default setpoint. Scenario 4 (Occupancy-Based) explores the boundary of automation, comparing ideal, presence-based control with a realistic deployment reflecting partial adoption and user overrides. Finally, Scenario 5 (Nudge Portfolio) compares four intervention archetypes social comparison, real-time feedback, pre-commitment, and gamification to evaluate how behavioral design and engagement frequency influence outcomes.

Formal mathematical formulations, parameter definitions, and implementation steps are presented in Section 2.3 (Lumped-Parameter Thermal Model and Calibration). The qualitative structure of the scenarios is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Behavioral Scenarios and Key Modeling Features.

2.1. Physical Foundation & Calibration

To establish a physically consistent baseline for analyzing behavioral interventions, this study first develops an aggregate thermal model of Luxembourg’s entire single-family home (SFH) stock. The methodology follows the hybrid physical and data-driven approach proposed in [22], which treats the city-scale building stock as a single thermal entity represented by a lumped-parameter model. This top-down approach avoids the impractical task of modeling thousands of individual dwellings from the bottom up, instead focusing on estimating two key aggregate parameters: the overall heat-loss coefficient () and the balance point temperature ().

The model calibration relies on eight years (2008–2015) of historical hourly data, consisting of national space heating (SH) demand in megawatts (MW) and the corresponding outdoor air temperature in degrees Celsius [23,24]. For Luxembourg’s single-family homes, this dataset corresponds to approximately 84,000 dwellings, inferred by dividing the mean annual SH demand (2.06 TWh) by a representative specific heating demand of 24.5 MWh per household per year [23,24]. The aggregate thermal behavior of the SFH stock is described by a first-order steady-state relationship between space-heating demand and the temperature difference between indoor and outdoor air:

where is the hourly space heating demand (MW), is the indoor temperature setpoint (°C), and represents the effective internal heat gains (MW). The constant (MW/K) reflects the aggregate heat transmission losses through the building envelopes, while captures the combined effects of internal sources such as occupants, appliances, and solar radiation. The indoor setpoint is defined behaviorally for each scenario. Model calibration was conducted by isolating heating-active periods (ambient temperature below 15 °C, demand above 1 MW) and fitting a linear regression between and [22]. The slope of this regression yields , and the x-intercept provides the balance-point temperature the ambient temperature at which heating ceases. The same physical relationship can be expressed as the classical balance-point model:

where denotes truncation at zero (no heating required when ). In this formulation, the indoor setpoint is treated as an external driver that modulates demand relative to the calibrated baseline. To ensure thermodynamic consistency, the internal gains were calculated assuming a baseline indoor temperature as:

This assumption reflects the common European comfort standard for heating setpoints (EN ISO 7730) [25]. The use of a constant simplifies the aggregate model and is consistent with previous lumped-parameter studies. While internal gains vary dynamically across households, their aggregate mean value is sufficiently stable over large populations and time horizons. These assumptions balance computational tractability with empirical realism. Sensitivity testing indicated that variations in of alter annual energy estimates by less than 1.5%, confirming model robustness for comparative scenario analysis. This baseline is held constant for Scenarios 1, 2, 3, and 5. The Occupancy-Based scenario (Scenario 4) uses a dynamic to reflect occupancy state.

All simulations were implemented in MATLAB R2023a using Equations (1)–(3) with the calibrated parameters above. Each behavioral scenario modifies according to its behavioral rule. Hourly SH profiles are then integrated over the simulation horizon to produce annualized energy totals (GWh/year), providing a consistent baseline for cross-scenario comparison. While dynamic simulation tools (e.g., EnergyPlus) offer granularity, they are susceptible to parameter uncertainty and the “performance gap” at the urban scale. In contrast, this model derives reliability from empirical calibration against eight years of metered demand (with high rate of R2), inherently capturing the “as-operated” thermal reality. Furthermore, this computational efficiency allows for the extensive Monte Carlo simulations required to robustly quantify behavioral uncertainty.

Crucially, to isolate the impact of each behavioral strategy, all scenarios were simulated over the exact same eight-year historical weather profile. This ensures that the reported energy savings are attributable solely to the intervention and are fully normalized against variations in outside air temperature.

2.2. Behavioral Scenario Simulation

All simulations begin from a Standard Behavioral Baseline, representing typical thermostat use in European single-family homes. The hourly indoor temperature setpoint, , follows a simple, rule-based schedule:

This profile reflects standard comfort behavior: a 2 °C night setback for energy savings, a small weekend boost (+0.3 °C) for increased occupancy, and operational limits between 18–23 °C. This setpoint aligns with ‘Category II’ design criteria (normal expectation) in EN 16798-1 and satisfies the Predicted Mean Vote (PMV) indices defined in ISO 7730. This establishes a standardized, thermally neutral baseline for sedentary occupants, against which subsequent behavioral deviations are measured [25,26,27]. All subsequent scenarios modify relative to this baseline, ensuring that differences in energy use arise solely from behavioral or control interventions rather than from changes in physical model parameters.

2.2.1. Window-Opening Behavior

The Window-Opening Scenario investigates the fragility of thermostat-based savings when occupants engage in counterproductive ventilation during the heating season. Such behavior is among the most common causes of unintended energy waste in dwellings, particularly during mild winter days when perceived stuffiness leads to short but frequent window-opening events. The indoor temperature setpoint in this case remains identical to the Standard Behavioral Baseline, , but the effective space-heating demand is increased by a stochastic penalty factor that represents transient heat losses due to open windows:

where denotes the relative heat loss multiplier (a 25% increase in heating demand during open-window events) [28]. Window-opening events are modeled as random hourly occurrences with a probability of under two conditions: (i) ambient temperature and (ii) baseline heating demand . These constraints capture the realistic context in which ventilation is most likely to occur occupied hours during active heating seasons while maintaining statistical simplicity suitable for city-scale simulations.

All thermal parameters () remain constant across runs, ensuring that variations in energy demand emerge solely from behavioral inefficiencies. This scenario therefore functions as a behavioral fragility test, demonstrating that small deviations from optimal user behavior can erode a substantial portion of thermostat-induced savings a finding consistent with broader evidence on the “performance gap” in building energy use.

2.2.2. Flexible Comfort

The Flexible Comfort scenario is designed to quantify the energy-saving potential of a “smart” thermostat system that dynamically adjusts setpoints based on multiple, simultaneous inputs. This moves beyond simple programmatic setbacks to model a responsive system that optimizes comfort, cost, and weather. The analysis contrasts three distinct profiles: a static baseline, a fully flexible profile, and a behaviorally “nudged” profile. The Fixed Setpoint (Lock-in) profile serves as the control, assuming a constant indoor temperature always. The Flexible Comfort () profile represents a dynamic system incorporating five distinct heuristic rules applied sequentially to the 21 °C baseline:

- Night Setback: A 1.5 °C reduction during nighttime hours ().

- Weekend Boost: A 0.2 °C increase during daytime weekend hours ().

- Smart Pre-heating: A 0.5 °C anticipatory boost when a significant drop in outdoor temperature () is imminent.

- Price Response: A 0.3 °C reduction during predefined peak-price periods ().

- Overheat Protection: A final 0.4 °C reduction if the resulting setpoint exceeds 22 °C, to mitigate overheating.

The final setpoint is constrained within a hard comfort band of to ensure occupant acceptability. The Default Nudge () profile models a behavioral intervention, where users are “anchored” to a lower default temperature. Its setpoint is calculated as a weighted blend of the fully flexible profile and a lower, energy-conscious anchor point of 19 °C.

This profile is also clamped to the comfort band. This scenario investigates the net energy impact of automated, multi-input “smart” logic, which can include both energy-saving (setback, price response) and energy-consuming (pre-heating, weekend boost) actions. The inclusion of the profile allows for a nuanced comparison, isolating the impact of a purely behavioral “anchoring” effect from the more complex technological interventions of the profile.

2.2.3. Occupancy-Based Heating

This scenario investigates the energy-saving potential of occupancy-based thermostat controls. The methodology is distinct in that it first simulates an aggregate occupancy profile for the building stock and then models the energy impact of a “realistic” technology rollout, accounting for both imperfect use and incomplete market adoption. An hourly occupancy profile, , is generated using a first-order Markov chain, where the state is binary ( for “Home,” for “Away”). To capture different mobility patterns, the transition probabilities are defined separately for weekdays and weekends. This stochastic profile (generated with a fixed random seed for reproducibility) serves as the control signal for the automated heating scenarios.

Three profiles are compared to quantify the savings:

- The Fixed Schedule (Baseline) profile serves as the control, representing 100% non-adoption. It assumes a constant indoor temperature = 21 °C at all times, irrespective of occupancy.

- The Ideal Automation (with Error) profile, , models a building where an occupancy-based thermostat is installed. The setpoint logic is directly tied to the occupancy state :

- Away (): A deep setback to 16 °C.

- Home, Night (): A night setback to 19 °C.

- Pre-heat (): The setpoint is raised to 19 °C one hour prior to arrival.

- Home, Day (): Comfort setpoint of 21 °C.

- To simulate imperfect use, a 10% probability of human error () is introduced, which, when triggered, overrides the automated logic and reverts the setpoint to = 21 °C for that hour.

The Smart Thermostat (Realistic) profile does not represent a setpoint but rather the aggregate demand of a mixed adoption building stock. It is calculated as a weighted average of the demand from the “Fixed Schedule” () and the “Ideal Automation (with Error)” () profiles.

An adoption rate of is assumed, modeling a market where 80% of buildings use the smart system (imperfectly) and 20% remain on the fixed, non-responsive baseline. The purpose of this scenario is to differentiate between the technical potential of a technology (i.e., perfect use by all) and its realistic potential in a real-world market. By explicitly modeling and combining the “dilution” effects of both imperfect user adherence (the 10% error) and incomplete market adoption (the 20% non-adopters), this scenario provides a more sober and policy-relevant estimate of the energy savings achievable from smart thermostat interventions. The model’s internal gains () were dynamically switched: (131.0 MW) was applied when (Home), and (e.g., 39.3 MW) was applied when (Away). This ensures that “ghost” internal gains do not artificially heat unoccupied homes.

2.3. Quantification & Ranking (Sensitivity Analysis)

This final scenario quantifies the performance and uncertainty of four distinct, low-cost behavioral “nudge” interventions. Unlike the previous scenarios which modeled specific, deterministic profiles, this analysis employs a Monte Carlo framework to assess the range of potential savings for each nudge, acknowledging that their real-world effectiveness is variable.

All nudges are modeled as modifications to the Standard Behavioral Baseline () (the profile with a 2.0 °C night setback and 0.3 °C weekend boost). Each nudge is assigned a range of effectiveness, , derived from behavioral science literature.

The logic for each intervention is as follows:

- Social Comparison: Modeled as a general reduction in the setpoint, , where is a value sampled from the effectiveness range.

- Real-Time Feedback: Modeled as a targeted intervention to reduce overheating. The setpoint is reduced by a factor only during “window-prone” hours (i.e., mild outdoor temperatures and high indoor setpoints ).

- Pre-Commitment: Modeled as an enhancement to the existing night setback behavior. The 2.0 °C setback magnitude is multiplied by a sampled factor , effectively deepening or shallowing the commitment.

- Gamification: Modeled as a general setpoint reduction, , like Social Comparison but representing a different behavioral mechanism and effectiveness range.

To quantify the uncertainty, a Monte Carlo simulation () is performed for each of the four nudges independently. In each simulation step :

- An effectiveness value, , is randomly drawn from the intervention’s predefined range, , assuming a uniform distribution.

- This value is applied to the profile according to the nudge-specific logic, creating a new setpoint vector .

- The total annual heating demand, , is calculated.

- The percentage energy saving relative to the demand is stored.

This process generates a distribution of 1000 possible saving outcomes for each nudge. The objective of this analysis is to move beyond single-point estimates and provide a robust, statistical comparison of the interventions. By generating a mean, median, and 90% confidence interval (5th to 95th percentile) for each nudge, this methodology allows for a risk-aware assessment of which interventions provide the most reliable and substantial energy savings under uncertainty.

2.4. Dataset and Historical Data

The empirical foundation of this study is an hourly time series representing the aggregate space heating (SH) demand of Luxembourg’s single-family home (SFH) stock, paired with corresponding outdoor temperature data. The dataset covers the period from January 2008 to December 2015 and originates from the open-source When2Heat database which provides harmonized national heat demand profiles for 28 European countries [24].

For Luxembourg, the When2Heat dataset contains two synchronized hourly variables: total national space heating demand (MW) and ambient air temperature (°C). After ensuring temporal consistency and completeness, the analysis was performed on 70,120 hourly observations for each variable. The dataset spans a broad climatic range (−18.7 °C to 35.3 °C, mean 9.0 °C), with space heating demand varying between 0 MW and 1181 MW (mean 245.4 MW) [23]. The reliability of this dataset stems from its methodology, which synthesizes hourly profiles using Standard Load Profiles applied to national annual gas consumption statistics. These profiles are generated by combining daily gas demand data with population-weighted outdoor temperature measurements derived from ERA-Interim re-analysis data, ensuring spatial representativeness. The resulting profiles are harmonized with Eurostat annual energy balances, providing a validated, nationally representative baseline for heating demand sensitivity to meteorological variations.

Data preprocessing involved removing outliers beyond three standard deviations, linearly interpolating less than 0.3% of missing values, and aligning timestamps between temperature and demand records. The processed series were retained at national hourly resolution and constitute the reference thermal load for model calibration and scenario simulations [23,24].

The resulting baseline annual thermal demand amounts to 2057.8 GWh year−1, reflecting the full heating requirement of the SFH stock predominantly supplied by fossil fuels (natural gas and oil). This value should not be confused with Luxembourg’s official residential electricity consumption (~950 GWh year−1 in 2023), which mainly covers non-heating end-uses [23,24]. The purpose of this study is to assess how behavioral and control strategies, such as smart thermostat adoption, could reduce this large thermal demand as heating transitions toward electrification [29].

3. Results

This section presents the quantitative findings of the study, structured in two main parts. We first establish the physical baseline by detailing the calibration of the lumped-parameter thermal model against the eight-year historical dataset. This step validates the model and derives the key aggregate parameters ( and ) used in all subsequent analyses.

With this calibrated model as a testbed, we then sequentially evaluate the energy-saving impact of the five behavioral scenarios. We begin with Scenario 1 (Dynamic Thermostat) to establish a performance baseline for simple, rule-based setbacks, followed by Scenario 2 (Window-Opening) which tests the fragility of these savings against counter-productive user behavior. Next, Scenario 3 (Flexible Comfort) investigates whether algorithmic complexity outperforms simple, anchored setpoints. Scenario 4 (Occupancy-Based) then quantifies the high-impact potential of presence-based automation. The analysis concludes with Scenario 5 (Nudge Portfolio), which uses a Monte Carlo analysis to rank the effectiveness of four distinct behavioral nudges and identifies the importance of architectural alignment.

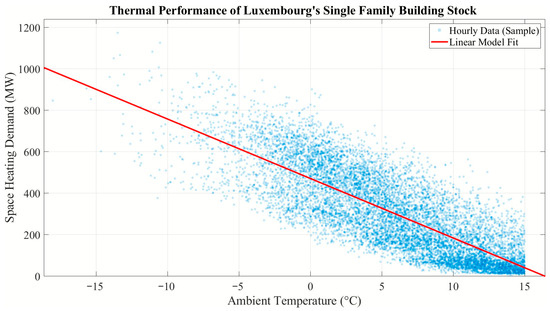

3.1. Model Calibration

The aggregate thermal response of Luxembourg’s single-family home (SFH) stock was characterized using a lumped-parameter model calibrated against eight years of hourly space heating demand and ambient temperature data (2008–2015). Following established practice for city-scale thermal modeling [22], the calibration focuses on steady-state heating periods during the core winter season, defined as 1 December through 28 February, where heat loss dominates and internal gains are relatively stable. Under these conditions, a strong linear relationship emerges between outdoor temperature and space heating demand, with a coefficient of determination of R2 = 0.89 (Figure 2). This high explanatory power confirms that the dominant driver of aggregate heating demand is conductive heat loss through the building envelope, a process well captured by the balance-point framework.

Figure 2.

Calibration of the lumped-parameter thermal model using hourly space heating demand versus ambient temperature (2008–2015). The red line represents the linear regression fit (R2 = 0.89), with parameters: = 28.67 MW/K and = 16.43 °C.

This specific calibration window is used because it isolates the primary physical parameters of the building stock: during these cold periods, heat loss through the envelope dominates, and the effect of variable internal gains (from occupants, appliances) and solar gains is minimal. By intentionally excluding the more variable “shoulder seasons,” we preserve the physical interpretability of the key parameters.

Deviations from linearity at milder temperatures or during transitional seasons arise from factors not explicitly modeled in this simplified framework, including solar gains, variable internal heat gains (from appliances, lighting, and occupancy), and non-ideal thermostat behavior (e.g., overrides, setbacks). While these effects reduce the overall coefficient of determination to R2 = 0.75 when the full annual dataset is considered, they are intentionally excluded from the calibration window to preserve the physical interpretability of the key parameters: the aggregate heat loss coefficient ( = 28.67 MW/K) and the balance point temperature ( = 16.43 °C). Critically, because all behavioral scenarios are evaluated on this same physically consistent baseline, the relative energy savings reported herein reflect genuine differences in behavioral strategy not artifacts of model misspecification. Using the 21 °C baseline indoor temperature defined in the methodology, The resulting occupied aggregate internal heat gain () is calculated as 131.0 MW. An unoccupied gain () was estimated as, 39.3 MW (approximately 30% of the occupied value), representing standby appliances and refrigeration [30,31,32]. These gains were held constant for all scenarios except Scenario 4 (Occupancy-Based), where they were applied dynamically based on the occupancy state.

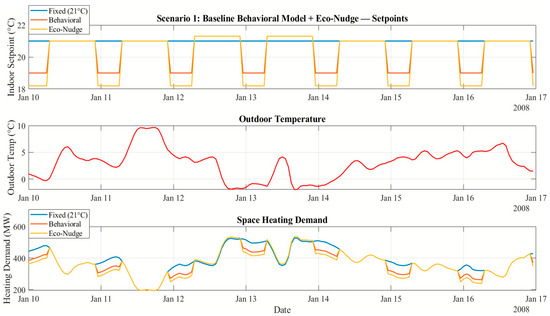

3.2. Scenario 1: The Baseline for Behavioral Savings

Scenario 1 establishes a critical reference point by comparing a fixed 21 °C setpoint with two increasingly engaged behavioral profiles. The results show that a “standard behavioral model”, which represents the simple, rule-based adjustments many households already implement with programmable thermostats, such as a 2.0 °C nighttime setback and a modest weekend comfort boost, reduces annual heating demand by 7.0%. When an eco-nudge deepens the nighttime setback by an additional 0.8 °C, total savings rise to 9.8%.

These findings are significant not because they introduce technological novelty, but because they confirm that these simple, widely used strategies yield substantial energy reductions on a scale. As visualized in Figure 3, these reductions stem directly from sustained downward shifts in the indoor temperature profile. The heating demand in the bottom panel visibly tracks the setpoint changes in the top panel, for instance, when the “Eco-Nudge” setpoint (yellow line) drops to 18.2 °C at night, the corresponding heating demand, as dictated by the steady-state model, immediately falls below both the ‘Behavioral’ (orange line) and ‘Fixed’ (blue line) demand curves (The real-world implications of this instantaneous response, which omits thermal mass, are addressed in the Discussion).

Figure 3.

Dynamic response of space heating demand to different thermostat setpoint strategies.

More importantly, the incremental gain from the eco-nudge reveals the outsized influence of small shifts in default settings: a less-than-1 °C change in one part of the day produces a 2.8 percentage-point increase in savings, underscoring that the average indoor temperature, not scheduling complexity, is the dominant lever. This scenario also exposes a key asymmetry: while deliberate conservation actions generate measurable savings, those gains remain vulnerable to erosion by inconsistent user behavior. It thus sets a performance floor: any proposed smart thermostat feature must meaningfully exceed this 9.8% benchmark to justify its added complexity or cost.

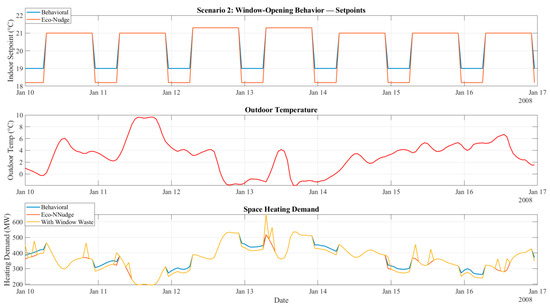

3.3. Scenario 2: The Fragility of Behavioral Savings

The previous scenario established that a simple eco-nudge could achieve a 9.8% annual saving. Scenario 2 was designed to immediately challenge this finding by testing the vulnerability of user-dependent savings against common, counter-productive behavior: opening a window while the heat is on. The results expose a critical weakness in relying on user compliance. The results expose a critical weakness in relying on user compliance. The introduction of this single, stochastic behavior does not erase the 9.8% gain from the eco-nudge but significantly reduces it to 7.6% saving. This 2.2 percentage-point loss demonstrates that the savings are highly fragile. Figure 4 provides a clear visual of this effect. The “With Window Waste” demand curve (yellow line) consistently rises above the eco-nudge baseline. During the daytime peak on Jan 13, for instance, this single behavior imposes an additional heat load of 50–75 MW, immediately diminishing the benefit of the lowered thermostat setpoint. This outcome suggests a fundamental asymmetry: deliberate conservation requires sustained user effort, but a single, low-awareness action can erode hours of progress. It demonstrates that the resilience of an intervention to human fallibility is as critical as its theoretical potential. The assumed 25% transient heat-loss penalty during window opening is consistent with empirical evidence on envelope performance. It is reported that approximately 30% of a typical dwelling’s total heat loss occurs through windows and related ventilation actions [33]. This supports using 25% as a representative, conservative value for short-duration window-opening events under Central European climatic conditions.

Figure 4.

The counterproductive effect of window-opening behavior on heating energy savings.

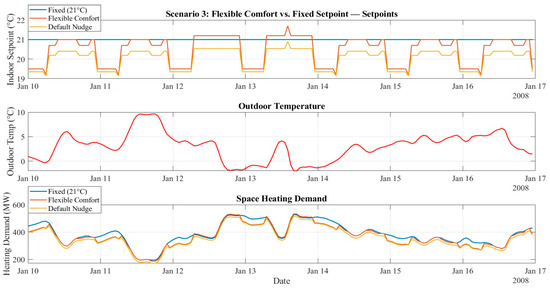

3.4. Scenario 3: Algorithmic Complexity vs. The Thermal Baseline

This scenario tests a central assumption of many “smart” thermostats: whether algorithmic sophistication can deliver superior energy savings compared to the simple rule-based setbacks explored in Scenario 1.

The algorithm for the “Flexible Comfort” model (orange line) calculates the hourly setpoint by starting with a 21 °C baseline and then applying a series of checks in order:

- Night Setback: The setpoint is lowered by 1.5 °C during the night (11 PM to 6 AM).

- Weekend Boost: The setpoint is raised by 0.2 °C during non-night hours on weekends.

- Pre-Heat for Comfort: If the algorithm detects a rapid outdoor temperature drop (more than 3 °C in the next hour), it increases the setpoint by 0.5 °C to pre-heat the building.

- Price Response: The setpoint is lowered by 0.3 °C during weekday peak price hours (6–9 AM and 5–8 PM).

- Overheat Protection: If any adjustment pushes the setpoint above 22 °C, it is reduced by 0.4 °C.

- Final Clamping: The final setpoint is bounded, ensuring it never goes above 23 °C or below 18 °C.

This logic was designed to be a realistic proxy for a “comfort-focused” smart algorithm, incorporating common features like night setbacks, price responses, and adaptive pre-heating. Its parameters are based on typical values discussed in building science literature.

The results deliver a clear verdict: algorithmic intelligence, on its own, is functionally inert. The “Flexible Comfort” model achieved only a 6.0% saving. This is significantly worse than the 9.8% saving achieved by the simple “eco-nudge” from Scenario 1. Figure 5 shows why. The “Flexible Comfort” profile (orange line) frequently overlaps with the fixed 21 °C baseline (blue line). Furthermore, its “smart” logic (Step 3) is architecturally flawed: during the cold snap on Jan 13, it spikes the setpoint to pre-heat for comfort, increasing energy demand at the worst possible time. The algorithm’s adjustments are misaligned with energy-saving goals, rendering it ineffective. It should be noted that this outcome reflects the specific comfort-oriented control logic tested here. Algorithms designed with stronger coupling to occupancy or dynamic pricing signals could, in principle, achieve higher efficiency if properly aligned with thermal dynamics.

Figure 5.

Comparison of heating demand under fixed, flexible comfort, and default nudge setpoint strategies.

The algorithm’s value only appears when it is combined with a lower thermal baseline. In the second variant (labeled “Default Nudge” in the figure), the algorithm was blended with a lower, fixed 19 °C setpoint requirement. This anchored algorithm successfully matched the 9.8% savings of the simple eco-nudge.

This demonstrates that the savings came from the lower baseline anchor, not the algorithm’s flexibility. This reinforces, within the limits of the tested configuration, the finding that the average indoor temperature setpoint, not the complexity of the logic used to adjust it, is the dominant driver of heating demand.

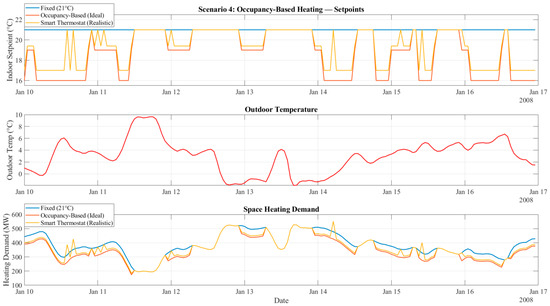

3.5. Scenario 4: The Paradigm Shift of Automation

Scenario 4 delivers the most consequential result of this study: occupancy-based heating achieves a 12.9% reduction in annual heating demand. This finding represents a paradigm shift from user-dependent conservation (like nudges) to technology-enabled automation (linking heat to presence).

This was compared against a “Smart Thermostat (Realistic)” variant, which models a probabilistic policy rollout. This model assumes an 80% adoption rate among the building stock, with the remaining 20% (“non-adopters”) defaulting to the fixed 21 °C baseline. Furthermore, the 80% “adopter” group is modeled with a 10% “user error” rate, representing hours where they override the system, which also reverts their setpoint to 21 °C. Even with these realistic failures blended in, the strategy still delivers a robust 8.0% saving.

Figure 6 provides undeniable visual proof of this mechanism. During unoccupied periods, such as the daytime hours of Jan 14 and 15, the “Occupancy-Based (Ideal)” setpoint (orange line) plunges to 16 °C. The heating demand (orange line, bottom) also drops significantly but maintains a substantial baseline of ~275 MW, which is the energy required to maintain the 16 °C setback temperature. In contrast, the “Fixed Schedule” (blue line) remains at 21 °C, continuously consuming over 300 MW of heating power. These adoption and error parameters represent uniform, first-order approximations; future work should incorporate heterogeneity in user behavior and adoption dynamics to capture population-level diversity. The “Smart Thermostat (Realistic)” (yellow line) is visibly pulled up from the ideal orange line, showing the impact of the non-adopters and user errors. This is the physical manifestation of eliminating waste: heat is delivered only when and where it is needed.

Figure 6.

Comparison of heating demand for fixed, occupancy-based, and smart thermostat schedules.

It is important to acknowledge a key simplification in this model. This aggregate thermal model does not capture the transient “ramp-up” energy costs associated with frequent reheating from a deep setback. In the real world, the efficiency of this strategy can be dependent on the heating system type; high-mass systems (e.g., hydronic radiators) may struggle with frequent cycling, whereas forced-air systems can respond more quickly.

Despite this limitation, the resilience of the “Smart Thermostat” variant (8.0%) demonstrates that the core energy-saving mechanism is exceptionally powerful. What distinguishes this scenario is its fundamental design philosophy: it removes the user from the decision loop, automating efficiency rather than relying on human intention.

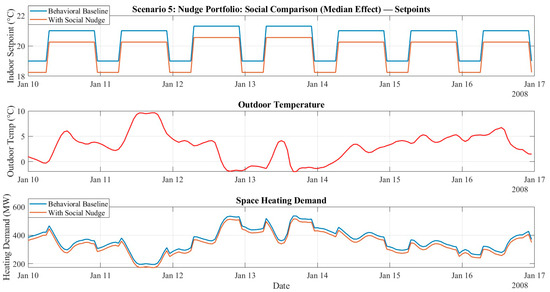

3.6. Scenario 5 (Part 1): The Success of Architecturally Sound Nudges

Scenario 5 moves beyond simple rules to test a portfolio of digital behavioral interventions. To understand the results, we first isolate the most effective nudge: social comparison. This nudge is designed to shift user norms by framing energy use relative to peers, and it reveals a unique capacity to alter baseline behavior without triggering resistance.

The results, visualized in Figure 7, show that applying a uniform 0.75 °C reduction (an effect size consistent with large-scale field studies) to the behavioral baseline achieves a 7.6% saving. This is not a complex adjustment; it is a fundamental reorientation of thermal comfort expectations.

Figure 7.

The effect of a social comparison nudge (median case) on thermostat setpoints and space heating demand.

Figure 7 makes its mechanism clear: the “With Social Nudge” setpoint (orange line) always sits consistently below the “Behavioral Baseline” (blue line), including high-demand nighttime and weekend hours. What distinguishes this intervention is its architectural soundness: it does not rely on specific timing or triggers. It simply lowers the default, and users accept it because it feels socially validated.

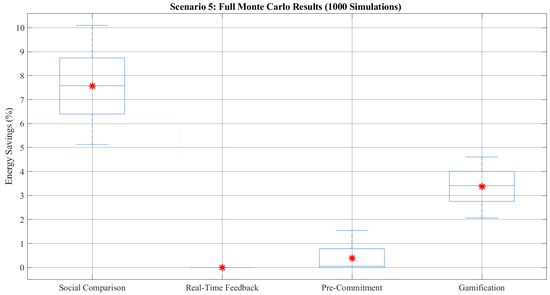

3.7. Scenario 5 (Part 2): The Monte Carlo Analysis

Each behavioral nudge was simulated using Monte Carlo sampling (n = 1000), with central effect sizes set to reflect empirically observed ranges of household energy reductions from social-norm and feedback-based interventions. The sampling variability of ±30% around these central values was chosen to represent realistic behavioral uncertainty rather than arbitrary noise. The full Monte Carlo analysis of all four nudges (Figure 8) confirms this lesson: intervention architecture is more important than psychological framing.

Figure 8.

Monte Carlo simulation results (n = 1000) comparing the energy savings from four behavioral nudges. The median value is shown by “*” in the figure.

The analysis reveals a stark divergence in effectiveness. Social comparison emerged as the most potent and robust strategy, delivering a mean savings of 7.6% (90% CI: 5.3–9.8%). Gamification, which is also shown in Figure 8, delivered moderate but consistent gains with a mean of 3.4%. In stark contrast, real-time feedback produced negligible savings (mean 0.0%), and pre-commitment yielded a marginal 0.4%.

These interventions failed not due to weak psychology, but due to flawed design. The real-time feedback nudge, for example, activates only during mild, non-night hours when heating demand is already minimal, rendering it irrelevant. The boxplot in Figure 8 visually underscores this: social comparison’s results are clustered high, while real-time feedback’s results are clustered at zero. This reinforces a critical principle: behavioral interventions must be contextually targeted at moments of high energy use to generate meaningful savings; otherwise, they risk being functionally inert.

Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the quantitative findings for all five scenarios.

Table 2.

Summary of Designed Behavioral Scenario Results.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a fundamental hierarchy in the drivers of residential heating demand, providing clear answers to the research questions guiding this analysis. The results consistently show that an intervention’s success hinges on its ability to durably alter the physical thermal baseline and its architectural alignment with high- consumption periods.

4.1. The Potential of Low-Cost and Automated Strategies (RQ1 & RQ4)

Regarding the energy-saving potential of different strategies, the analysis shows that occupancy-based automation is overwhelmingly the most effective intervention. By removing the user from the decision loop, it achieves a 12.9% reduction in heating demand. This result significantly exceeds the 10–15% savings typically reported in field studies of programmable thermostats, which often suffer from user error or abandonment. Our model, which accounts for a 10% error rate and an 80% adoption scenario, still delivers 8.0% savings, demonstrating the resilience of automation. This supports the “automation over agency” principle: when sustainability is passive, compliance is near-universal. While effective, the widespread deployment of such technologies raises valid concerns regarding user privacy and autonomy, which must be addressed through transparent design and policy to ensure social acceptance.

Simpler, low-cost strategies also yield significant savings. A standard behavioral model with a nighttime setback reduces demand by 7.0%, and a simple eco-nudge increases this to 9.8%. This confirms that widely deployable interventions that embed modest setbacks can unlock substantial national heating savings without requiring new infrastructure or advanced algorithms. From an economic perspective, the distinction between these strategies is stark. While physical retrofits require significant capital investment with payback periods often measured in decades, the behavioral and algorithmic strategies identified here particularly the default setback and occupancy-based automation represent “low-cost” or “no-cost” measures. For households already equipped with programmable or smart thermostats, the Return on Investment (ROI) of a 9.8% energy reduction via an “Eco-Nudge” is immediate, as the marginal implementation cost is effectively zero.

4.2. Effectiveness and Resilience of Digital Nudges (RQ2)

In response to which digital nudges are most effective, the Monte Carlo analysis reveals that intervention architecture matters more than intent. Social comparison succeeds as the most potent and resilient strategy, delivering a mean savings of 7.6% (90% CI: 5.3–9.8%) because it operates at the level of social identity to shift the entire thermal norm downward. This result is consistent with prior empirical work, such as [15], who found a similar 6% decrease in dormitory air conditioner usage, validating the robustness of this behavioral mechanism. In stark contrast, real-time feedback and pre-commitment fail, producing less than 0.5% savings. This is not due to weak psychology, but to poor timing; they target moments of low heating demand (mild days, nighttime), where even large setpoint changes have negligible energy impact, rendering them functionally inert. Our work demonstrates that when a nudge activates is as critical as how it is framed.

4.3. Interaction with Thermal Dynamics and Behavioral Fragility (RQ3)

Addressing the interaction between interventions and physical thermal dynamics, the findings highlight two critical mechanisms. First, the thermal baseline the average indoor temperature exerts a far stronger influence on energy consumption than algorithmic sophistication. This principle explains why a simple eco-nudge, which lowers the nighttime setpoint by less than 1 °C, outperforms a complex “flexible comfort” model. The algorithm’s adjustments occur too infrequently or during low-demand periods to meaningfully shift the annual energy balance, confirming that intelligence without a reduced baseline is functionally inert.

Second, this interaction reveals the profound fragility of user-dependent savings. The significant erosion of eco-nudges by stochastic window-opening behavior illustrates this vulnerability. A single, low- awareness action opening a window while heating is active can negate weeks of conservation effort by directly conflicting with the thermal goals of the system. This finding, which resonates with empirical studies on “heat-wasting” behaviors, exposes a critical challenge for any policy that relies solely on user goodwill.

4.4. Integration with Survey-Based Behavioral Studies

Future work is its integration with survey or questionnaire-based studies on end-user preferences and behavioral drivers. While our model treats occupant behavior as a set of probabilistic rules, surveys can reveal the why behind those rules what motivates users to override settings, accept defaults, or respond to social norms. For example, if survey data shows that users are willing to accept a 19 °C setpoint only if framed as “comfortable for sleeping,” the model could incorporate context-specific anchors rather than fixed reductions. Similarly, if users report resistance to pre-commitment because they fear being locked into uncomfortable conditions, the model could simulate dynamic commitment windows or opt-out mechanisms. This would allow for a two-way calibration: model outputs can be tested against survey-reported behaviors, and survey insights can refine model parameters. Such integration transforms the model from a predictive tool into a participatory design platform enabling policymakers to test interventions not just for their energy impact, but for their social acceptability. Recent work by [22] demonstrates this approach in smart lighting, where user preference data was used for occupancy-triggered dimming profiles, increasing both energy savings and user satisfaction. Applying this to heating would require coupling our physics-informed model with discrete choice experiments or stated preference surveys, creating a hybrid socio-technical system that respects both physical constraints and human values.

Thermostat-driven heating reductions interact with electrification and demand response in complex ways. As heating electrifies, rebound effects may offset a portion of savings, while dynamic tariffs could amplify automation benefits. Integrating such couplings within demand-side management frameworks remains a crucial extension of this modeling approach.

4.5. Limitations of the Work

Despite these advances, the study has limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the lumped-parameter model does not capture variations in insulation, window area, or solar gains. Furthermore, its aggregate nature does not resolve building-level physical dynamics such as thermal mass, which can influence the real-world effectiveness and user acceptance of pre-heating strategies in occupancy-based scenarios. Second, behavioral assumptions such as a fixed 25% heat loss from window-opening or a uniform social comparison effect are stylized representations that may not reflect the full diversity of real-world responses. Third, the analysis focuses exclusively on heating and does not account for potential rebound effects in other energy domains (e.g., increased appliance use). Fourth, while Luxembourg serves as a compelling analog for a compact smart city due to its size and data availability, the transferability of these results to larger, more heterogeneous urban contexts requires further validation. The model does not incorporate cooling demand, which introduces different behavioral dynamics particularly in climates where summer discomfort drives energy use. Finally, while Scenario 4 used a dynamic internal gain based on occupancy, the other scenarios (1, 2, 3, and 5) used a constant, occupied internal gain. This simplification, while necessary for comparing those behavioral scenarios, does not capture the dynamic gains from real-time occupancy and solar radiation, which could be explored in future building-level analyses. These limitations do not invalidate the core findings but highlight areas for future refinement, particularly through large-scale field trials that combine sensor data, user surveys, and building-level energy monitoring.

It is acknowledged that since most of the modeled existing building stock lacks mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR), natural ventilation remains essential for Indoor Air Quality (IAQ). Consequently, the “Window-Opening” scenario does not suggest avoiding ventilation but rather quantifies the significant energy penalty of unregulated behaviors specifically when windows remain open during active heating periods highlighting the need for optimized, short-duration airing strategies.

5. Conclusions

This study quantifies the energy-saving potential of smart thermostat strategies across Luxembourg’s single-family home stock, offering a policy-ready hierarchy of interventions for urban decarbonization. The results demonstrate that real-world effectiveness hinges not on technological sophistication, but on behavioral realism and architectural alignment with high-consumption periods. Key findings are summarized as follows:

- While the energy-saving potential of setbacks is a known principle, this study quantifies its dominance over algorithmic complexity: results show that a simple 0.8 °C reduction in the thermal baseline outperforms complex, weather-responsive control logic, confirming that the average indoor temperature remains the single most critical lever for decarbonization, often rendering sophisticated control rules redundant if the baseline is not addressed.

- Occupancy-based automation delivers the highest impact: By linking heating to real-time presence, this strategy achieves 12.9% energy savings and remains resilient even at 80% adoption, proving that passive, sensor-driven control is superior to user-dependent scheduling.

- Behavioral savings are fragile and asymmetrical: The 9.8% gain from eco-nudges is significantly eroded by stochastic window-opening, a common, low-awareness behavior highlighting that conservation gains are easily undone by brief, conflicting actions.

- Nudge effectiveness depends on architectural design, not just psychology: Social comparison succeeds (7.6% savings) by shifting the entire thermal norm, while real-time feedback and pre-commitment fail (<0.5% savings) because they activate during low-demand periods, rendering them irrelevant to energy use.

Beyond the specific numerical reductions, these findings suggest a fundamental shift in the role of residential heating: moving from a static load to a flexible grid resource. The superior performance of occupancy-based automation over user-dependent nudges implies that future decarbonization strategies should prioritize ‘set-and-forget’ technologies. Such systems reliably reshape demand profiles without relying on continuous occupant engagement, thereby securing the consistent flexibility required for future low-carbon energy systems.

Together, these insights underscore a critical principle for smart residential energy systems: the most effective smart thermostats are not those that learn user preferences, but those that automate efficiency, anchor lower norms, and protect against waste. To meet urgent climate targets, urban energy strategies must prioritize interventions that are robust to human fallibility and scalable by design. Finally, we acknowledge the limitations of this aggregate approach. While the lumped-parameter model provides robust national-scale estimates, it does not capture building-level heterogeneity or cooling demand. Future work will address these gaps by integrating this physical framework with survey-based behavioral data to refine user archetypes and by extending the analysis to include summer cooling dynamics in a warming climate.

Author Contributions

V.A. and R.F.; methodology, V.A. and R.F.; validation, V.A.; investigation, V.A.; data curation, V.A.; writing—original draft preparation, V.A.; writing—review and editing, R.F.; visualization, V.A.; supervision, R.F.; funding acquisition, R.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Luxembourg National Research Fund (FNR) and PayPal (PEARL grant 13342933/Gilbert Fridgen) and by the Fondation Enovos in the frame of the “LetzPower” research project.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to thank Lorenzo Matthias Burcheri for his valuable comments and suggestions. During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) used ChatGPT-3.5 for the purpose of improving the language and readability of the text, and Google Gemini 1.5 for the purpose of generating Figure 1. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| Symbol/Abbreviation | Description | Unit |

| Mathematical Symbols | ||

| SH(t) | Space Heating Demand at time t | MW |

| Aggregate Heat Loss Coefficient | MW/K | |

| Indoor Temperature Setpoint at time t | °C | |

| Ambient Outdoor Temperature at time t | °C | |

| Balance Point Temperature | °C | |

| Aggregate Internal Heat Gains | MW | |

| Coefficient of Determination | - | |

| δ | Relative heat loss multiplier (Window-Opening) | - |

| p | Probability | - |

| St | Occupancy state (Home = 1, Away = 0) | - |

| Probability of human error | - | |

| α | Adoption rate | - |

| δr | Sampled effectiveness value (Nudges) | - |

| N | Number of Monte Carlo simulations | - |

| Abbreviations | ||

| CI | Confidence Interval | |

| DR | Demand Response | |

| EPG | Energy Performance Gap | |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product | |

| IAQ | Indoor Air Quality | |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control | |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning | |

| SFH | Single-Family Home | |

| SH | Space Heating | |

| TCL | Thermostatically Controlled Loads | |

| TUS | Time Use Surveys | |

| ROI | Return on Investment |

References

- Bian, F.; Chong, H.-Y.; Ding, C.; Zhang, W.; Li, L. Occupant behavior effects on energy-saving measures and thermal comfort in severe cold areas. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 73, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ke, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Han, X.G.; Su, W.; Zhang, X.; Lei, T.-H.; Sun, Z.; Zhou, H.; Yang, B. Occupant behavioral adjustments and thermal comfort with torso and/or foot warming in two cold indoor environments. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Ouf, M. A comprehensive review of time use surveys in modelling occupant presence and behavior: Data, methods, and applications. Build. Environ. 2021, 196, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, M.; Ouf, M.; Azar, E.; Dong, B. Stochastic bottom-up load profile generator for Canadian households’ electricity demand. Build. Environ. 2023, 241, 110490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouf, M.M.; Osman, M.; Bitzilos, M.; Gunay, B. Can you lower the thermostat? Perceptions of demand response programs in a sample from Quebec. Energy Build. 2024, 306, 113933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feifer, L.; Imperadori, M.; Salvalai, G.; Brambilla, A.; Brunone, F. Active House: Smart Nearly Zero Energy Buildings; Briefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; O’Brien, W.; Loftness, V.; Cochran Hameen, E.; Hong, T. A critical review of use cases and insights from a large dataset of smart thermostats. Adv. Appl. Energy 2025, 19, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stopps, H.; Touchie, M.F. Residential smart thermostat use: An exploration of thermostat programming, environmental attitudes, and the influence of smart controls on energy savings. Energy Build. 2021, 238, 110834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huchuk, B.; O’brien, W.; Sanner, S. Exploring smart thermostat users’ schedule override behaviors and the energy consequences. Sci. Technol. Built Environ. 2020, 27, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomat, V.; Vellei, M.; Ramallo-González, A.P.; González-Vidal, A.; Le Dréau, J.; Skarmeta-Gómez, A. Understanding patterns of thermostat overrides after demand response events. Energy Build. 2022, 271, 112312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritoni, M.; Salmon, K.; Sanguinetti, A.; Morejohn, J.; Modera, M. Occupant thermal feedback for improved efficiency in university buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 144, 241–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nema, S.; Prakash, V.; Pandžić, H. The role of thermostatically controlled loads in power system frequency management: A comprehensive review. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2025, 42, 101680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q. Optimal Incentive Strategy in Cloud-Edge Integrated Demand Response Framework for Residential Air Conditioning Loads. IEEE Trans. J. 2021, 10, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallianos, C.; Candanedo, J.; Athienitis, A. Application of a large smart thermostat dataset for model calibration and Model Predictive Control implementation in the residential sector. Energy 2023, 278, 127839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Zheng, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, X. Developing occupant-centric smart home thermostats with energy-saving and comfort-improving goals. Energy Build. 2023, 299, 113579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allcott, H. Social norms and energy conservation. J. Public Econ. 2011, 95, 1082–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, D.V.A.; Loomans, M.G.L.C.; Hajdukiewicz, M. A systematic literature review on occupant behaviour modelling for residential building performance simulation in future climate change scenarios. Build. Environ. 2026, 287, 113796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, R. Review and Growth Prospects of Renewable Energy. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Smart Grid and Renewable Energy (SGRE), Doha, Qatar, 8 February 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. Energy consumption in households. In Statistics Explained; Eurostat: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- University of Luxembourg. Power System Information Transparency for Households in Lëtzebuerg (“LetzPower!”). Available online: https://www.uni.lu/snt-en/research-projects/letzpower/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Chauvel, L.; Le Bihan, E. Households and Family Types: Gradual Diversification, 1st ed.; Université du Luxembourg: Luxembourg, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Arabzadeh, V.; Lund, P.D. Effect of Heat Demand on Integration of Urban Large-Scale Renewable Schemes—Case of Helsinki City (60 °N). Energies 2020, 13, 2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruhnau, O.; Hirth, L.; Praktiknjo, A. When2Heat Heating Profiles. Open Power System Data (Version 2023-07-27). 2023. Available online: https://data.open-power-system-data.org/when2heat/2023-07-27 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Ruhnau, O.M. Update and Extension of the When2Heat Dataset; ZBW—Leibniz Information Centre for Economics: Kiel/Hamburg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Olesen, B.W. Introduction to Thermal Comfort Standards and to Thermal Environmental Design. Energy Build. 2002, 34, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 7730:2025; Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Analytical Determination and Interpretation of Thermal Comfort Using Calculation of the PMV and PPD Indices and Local Thermal Comfort Criteria. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- EN 16798-1:2019; Energy Performance of Buildings—Ventilation for Buildings—Part 1: Indoor Environmental Input Parameters for Design and Assessment of Energy Performance of Buildings Addressing Indoor Air Quality, Thermal Environment, Lighting and Acoustics—Module M1-6. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Fekri, H.; Soltani, M.; Hosseinpour, M.; Alharbi, W.; Raahemifar, K. Energy simulation of residential house integrated with novel IoT windows and occupant behavior. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creos Luxembourg S.A. Scenario Report 2040—Version 2024; Creos Luxembourg S.A.: Luxembourg, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, I.; Thomson, M.; Infield, D. A high-resolution domestic building occupancy model for energy demand simulations. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 1560–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, P.B.; Neves, L.O. A critical review on occupant behaviour modelling for building performance simulation of naturally ventilated school buildings and potential changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Energy Build. 2022, 258, 111831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabzadeh, V.; Frank, R. Stochastic Markov-Based Modelling of Residential Lighting Demand in Luxembourg: Integrating Occupant Behavior and Energy Efficiency. Energies 2025, 18, 5133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Kong, X.; Yan, R.; Liu, Y.; Xia, P.; Sun, X.; Zeng, R.; Li, H. Data-driven cooling, heating and electrical load prediction for building integrated with electric vehicles considering occupant travel behavior. Energy 2023, 264, 126274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).