Highlights

What are the main findings?

- SAE Level 5 AVs could decrease intersection delay by up to 40% at full (100%) penetration.

- Low AV penetrations (20%) could still provide substantial efficiency benefits of around 10%, with the largest improvements observed under low left-turn percentages and balanced approach volumes.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Careful deployment of AVs at signalized intersections could provide significant efficiency gains and congestion reductions in mixed-traffic urban roads.

- The results presented in this paper may contribute to SDGs 11 and 13 by promoting more sustainable and lower-emission urban mobility.

Abstract

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) hold strong potential to redefine traffic operations, yet their impacts at varying penetration levels within mixed traffic remain insufficiently quantified. This study evaluates the influence of SAE Level 5 AVs on traffic performance at two typical urban signalized intersections using a hybrid microsimulation approach that integrates behavioral AV modeling and performance evaluation. The analysis covers two typical intersection layouts, one with two through lanes and another with three, tested under varying traffic volumes and left-turn shares. A total of 324 simulation scenarios were conducted with AV penetration ranging from 0% to 100% (in 20% increments) and left-turn proportions of 15%, 30%, and 45%. The results show that 100% AV penetration lowers the average delay by up to 40% in the two-lane intersection scenario and 32% in the three-lane scenario, relative to the 0% AV baseline. Even 20% AV penetration yields about half of the maximum improvement. The greatest benefits occur with aggressive AV driving profiles, balanced approach volumes, and small left-turn shares. These findings provide preliminary evidence of AVs’ potential to enhance intersection efficiency and support Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 11 and 13, offering insights to guide intersection design and AV deployment strategies for data-driven, sustainable urban mobility.

1. Introduction

Traffic congestion has become a significant problem, especially in fast-growing and large cities. Such traffic problems are expected to rise even more in the future because of world population growth. According to a report issued by the United Nations (UN), 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas, whereas this proportion is expected to increase to 68% due to urbanization in 2050 [1]. Users experience major travel time delays at signalized intersections when the traffic congestion is very high. Some researchers have shown that traffic signals in cities are inefficient when traffic volumes are high, and they may cause many collisions and traffic delays in urban areas [2,3,4]. In addition, data from several studies have shown that human errors are the leading cause of many traffic accidents and congestion at traffic signals. Stanton and Salmon [5] have shown that human errors account for up to 75% of all roadway crashes. The development of vehicle automation has opened the door to many possible advancements in the field of transportation. For instance, introducing autonomous vehicles (AVs) to the urban environment is expected to have great potential in improving traffic performance and safety, especially in urban areas and at signalized intersections. Many recent studies have shown promising results in terms of increasing intersection capacity and reducing total intersection delay [6,7,8]. However, most of those studies considered purely autonomous environments without any human-driven vehicles (HDVs). This will never be the case for most intersections in urban areas since AVs will not be implemented all at once; instead, the vehicle fleet will change gradually over time until a 100% penetration rate is reached in the future. In this paper, the effects of increasing the percentage of AVs on the performance of signalized intersections will be quantified and analyzed under different traffic conditions in a mixed-traffic system consisting of both AVs and HDVs.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the operational impacts of different AV penetration rates on the performance of urban signalized intersections using a hybrid microsimulation approach, focusing on average delay, level of service, and implications for sustainable urban mobility. To achieve this, this study applied an integrated framework combining Synchro for signal optimization and PTV VISSIM for microscopic traffic simulation under mixed AV and HDV conditions.

2. Background

Urban transport systems face global sustainability challenges characterized by increasing congestion, air pollution, and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions with widespread impacts on the environment, economy, and public health [9,10,11,12,13]. The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) recognize the need for sustainable cities, climate action, and good health and well-being as key priorities for future urban development [14,15]. The Paris Agreement on climate change calls for countries to take action to make immediate and sustained emission reductions across all sectors, including transport [16,17]. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also reports that the transport sector remains one of the fastest-growing sources of global emissions and will need to decarbonize rapidly to meet net-zero commitments [18,19,20]. At the same time, the International Energy Agency (IEA) anticipates that emissions from urban passenger transport will increase by more than 20% by 2050 without significant changes in mobility systems [21]. This trend risks compromising efforts to build climate-resilient infrastructure and services in both developed and emerging economies [22,23,24,25].

AVs have been identified as having a potentially key role in sustainable mobility futures [26,27,28,29,30,31]. Sharing and electrifying AV fleets could offer benefits to transport systems and urban environments in terms of travel efficiency, safety, congestion, and emissions [32,33,34,35,36,37]. However, the increased uptake of AVs could also cause negative impacts in terms of induced demand, energy consumption, land use change, and equity of access. The availability of relevant data and preparedness of governance and infrastructural systems are also raised as a major implementation challenge [38,39,40]. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) defines six categories of driving automation, from level 0 to level 5 [41,42]. Levels 0–3 are currently commercially available as driver-assist technologies, while higher levels of automation are under development or experimental deployment [43,44]. The highest level (SAE Level 5) is now being experimented with in some areas, but most real-world deployments are for fixed-route low-speed autonomous shuttles (ASs) in controlled environments [45,46,47,48,49,50]. There are global commercial activities and testing of AVs and related technologies by different industry actors, including Waymo, WeRide, Uber, Hyundai, Ohmio, and others [51,52,53,54,55]. In the UK, there are several ongoing connected and automated mobility (CAM) activities. These are supported by programs from the government and other sources, such as Zenzic’s SCALE project, which delivered AS trials in Solihull and at the NEC (National Exhibition Centre) [56,57,58,59,60,61].

The previous literature has analyzed AV impacts on various dimensions of mobility, transport, and urban systems. These include potential impacts on travel behavior, land use, and mode choice [62,63,64,65], acceptance and behavioral intention [66,67,68,69], safety and environmental performance [70,71,72], and policy readiness [73,74,75]. Simulation-based studies have modeled the potential impacts of AV penetration on traffic network performance, delay, and level of service (LoS) [73,76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. These generally show benefits depending on assumptions about penetration rates, vehicle composition, signal timing, and geometric design [83,84,85,86,87,88,89]. At signalized intersections, which are critical bottlenecks in urban networks, microsimulation can be used to estimate the operational effects of AVs under a variety of controlled conditions and system configurations in a cost-effective manner [35]. However, based on the conducted literature review in this study, only one previous study directly modeled AVs operating with HDV traffic in the UK [63].

There is a paucity of microsimulation research that specifically investigates operational impacts of AVs at intersections in realistic urban network settings with mixed traffic. The majority of the literature in this area is on freeways and simplified corridor models, with limited or no intersection traffic [48,77,78]. In other studies, idealized traffic demand is applied with all approaches having the same traffic demand and no vehicles making left turns or U-turns [79,80]. This could significantly bias the results in terms of queue and delay formation. In the context of growing policy interest in AVs in many countries, there is a critical need for robust data on their impact on existing networks when sharing the road with HDVs. The research presented in this paper aims to address this research gap by simulating an operational deployment of a mix of AVs and HDVs at an urban signalized intersection.

In the UK context, for example, the Department for Transport (DfT) has provided guidance for experimenting with AVs [81,82], and the British Standards Institution (BSI) has developed specifications for the safety assurance of AV operations [83]. Trials such as the AS service on the Solihull corridor [61] are increasingly being leveraged to evaluate not only technology performance but also compliance with regulatory frameworks, safety validations, and customer experience [84]. In low- and middle-income countries, cities in sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia [85], and Latin America [65] are also considering the relationship of AVs with existing modes of public transport, active travel, and climate adaptation and mitigation. These considerations present calls for an interdisciplinary, data-informed, and theoretically grounded approach to AV evaluation, cutting across technical, behavioral, and policy research [78].

Methodologically, many studies have combined macroscopic optimization tools (e.g., Synchro) and microscopic simulation platforms (e.g., PTV VISSIM) to model optimized signal timings, while also accounting for stochastic, vehicle-level interactions not accounted for in optimization models that impact performance [77,79]. For example, European Commission-funded CoExist project activities have shown that choosing different driving profiles (cautious, normal, or aggressive) to calibrate AVs in microscopic models can make a large difference in reported simulated delay and throughput values [86].

At present, there are limited data on AV operation in the real world, especially at higher penetration rates at or near saturation conditions at intersections [87]. While several studies have examined connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) and cooperative driving concepts such as vehicle-to-vehicle (V2V) and vehicle-to-infrastructure (V2I) communication [88,89,90], this study focuses solely on automation (SAE Level 5 AVs) without connectivity features. The intention is to isolate the operational effects of autonomous driving behavior, independent of cooperative or networked communication. Unquestionably, AVs are supposed to have an effect on the traffic flow as well as the congestion in the urban setting in any city. Talebpour and Mahamassani’s analytical studies, which are supported by microsimulation results, have indicated that CAVs can improve the stringency and stability of the flow of traffic [88]. In reality, other studies have established that the increase in the percentage of AVs in mixed traffic is directly associated with a reduction in congestion. This reduction can be attributed to the presence of AVs in mixed traffic, which can smooth the traffic flow since they accurately respond to changes in the velocity or acceleration. Moreover, automation in vehicles is more efficient in shockwave formation prevention and propagation in traffic than HDVs, which has a direct impact on traffic congestion [91,92]. A study by Fagnant and Kockelman [74] established that AVs are able to reduce congestion due to shorter headways, coordinated platoons, and more coordinated route choices. Ye and Yamamoto [89] used the three-phase traffic flow model to mimic the effect of AVs on freeways using different penetration rates. It was concluded that during the congestion phase, AVs have enhanced the capacity due to the relatively much smaller gap between successive AVs, when compared with HDVs. With up to a 30% penetration rate of AVs, the capacity increases gradually. After 30%, the capacity improvement is highly dependent on the desired net time gap of the AVs. Furthermore, other studies [74,93] were in agreement that AVs increase the capacity of freeways by reducing the headways and availing a platooning effect, which helps to create more space without incurring more costs in the infrastructure. Van Arem et al. [90] found that Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control (CACC) is able to improve traffic stability and throughput for a penetration rate of more than 60% in a merging scenario from four to three lanes in a highway traffic flow. But a very minimal effect on throughput resulted for a rate of less than 40% of AV penetration rates. Meanwhile, El Sahly and Abdelfatah [87] have investigated the effect of AVs on freeway traffic performance with different AV percentages in terms of market penetration using a microsimulation analysis. The results proved that AVs can improve average speed from 5% to 15% and reduce travel time by 1% to 12%, while the delay reduction ranges from 18% to 97% depending on the AV market penetration rate and demand-to-capacity ratios.

In general, the use of AVs with high penetration rates results in a significant improvement in the safety of roads, as proven by various studies [74,94,95,96,97]. According to statistical data, over 90% of the total crashes in the US are caused by human errors, as a primary factor [74]. The model created by Calvert et al. [94] revealed that automation leads to a reduction in accidents and, hence, results in fewer delays caused by road blockages and tailbacks created by traffic accidents. Similarly, Malik [97] has concluded that AVs are safer than HDVs since they can eliminate accidents caused by human errors. In addition, Fagnant and Kockelman [74] emphasized the safety enhancements that are provided by AVs and displayed that they could reduce fatality rates by up to 99%. This is due to the fact that AVs are capable of eliminating human driver errors, which might be caused by factors such as alcohol use, fatigue, drug use, etc. Another investigation by Morando et al. [96] assessed the safety level at signalized intersections using traffic volumes that ranged from 760 vph to 2260 vph of traffic volume at the intersection. The study concluded that at a 50% AV penetration rate, the number of conflicts is reduced by 20%, and at a 100% AV penetration rate, the number of conflicts is cut down by 65%. Meanwhile, at roundabouts, the number of conflicts declined by up to 64% at a 100% AV penetration rate [96].

Meanwhile, Dixit et al. [95] analyzed the data for a period of about 14 months to identify the accidents related to AVs and showed that all the accidents occurred at low speeds and near the intersections on urban streets. There were twelve different accidents recorded, and the fault in most of these accidents was attributed to the human drivers. Only one accident was caused by an AV, and the reason for that accident was that the AV had a wrong expectation that the other HDV would give it the way to pass. Meanwhile, the reason for the other accidents, which were caused by other vehicles, was that the other drivers thought that the AVs would behave in a way that was not normal or not like HDVs. In most of these accidents, there were no injuries, and there was no major damage to the vehicles since all collisions were rear-end collisions or side-swipe collisions caused by HDVs hitting AVs that were stopping in the front [95,98,99]. In addition, poor weather such as fog and snow, and reflective road surfaces from rain and ice, remains a challenge to AVs [74]. The speed at which human control is needed will be a substantial factor in the safety of those vehicles. After analyzing the safety aspects of AVs, most researchers acknowledge that AVs might be promising in spite of the fact that they might be affected by environmental conditions.

3. Methodology

This study employed a simulation-based approach to explore the operational implications of AV deployment at a signalized intersection. The simulation methodology was designed to model realistic traffic scenarios at an intersection under different AV penetration rates and traffic demand conditions. The microsimulation approach was adopted because it has the capability to represent individual vehicle behaviors, heterogeneous traffic flows, and signal control logic with an acceptable temporal and spatial resolution. The simulation analysis involved three steps, including the intersection geometry and control settings definition, simulation model development and calibration, and running simulation scenarios to evaluate the changes in the average control delay and LoS.

3.1. Geometric Characteristics

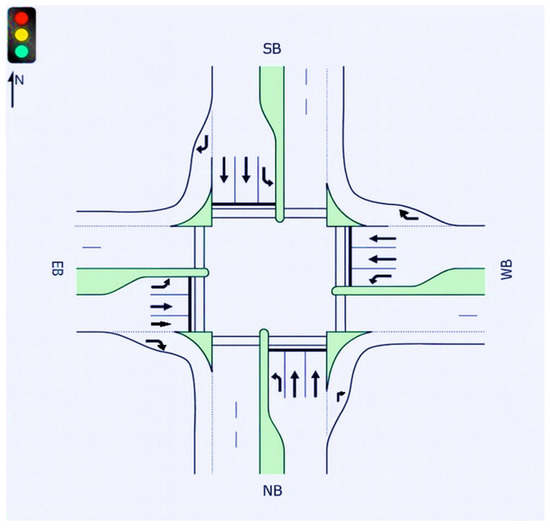

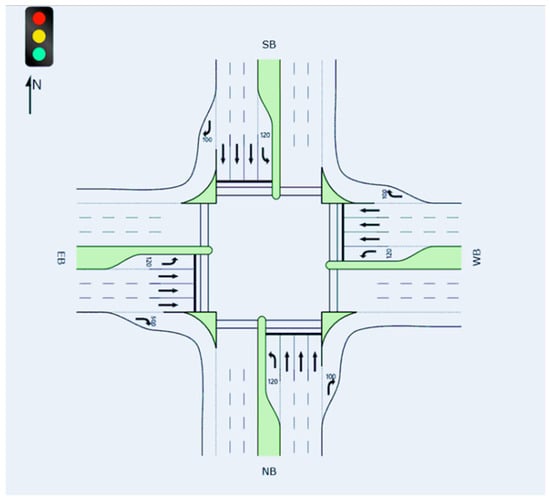

The considered intersection was a typical isolated 4-leg intersection with two configurations. In the first case, each approach consisted of two through lanes, one left-turn lane and one right-turn lane, as shown in Figure 1. In the second case, each approach consisted of three through lanes, one left-turn lane and one right-turn lane, as shown in Figure 2. The purpose of this experiment was to examine the intersection from the perspective of signal timing and delay evaluation, considering various AV penetration levels within different traffic volumes and turning percentages. Hence, a microscopic simulation was utilized to assess the impacts of various AV penetration levels on average delay and LoS. The geometric characteristics of the intersection are summarized in Table 1. The intersection layouts were hypothetical but representative of typical urban arterial intersections, designed in accordance with standard geometric and operational parameters commonly used in real-world practice.

Figure 1.

Intersection with two through lanes per approach.

Figure 2.

Intersection with three through lanes per approach.

Table 1.

Geometric characteristics of the analyzed intersection.

3.2. Signal Control

The proposed signal was an isolated signal control type with 4-split phases in all the traffic arrangements. The LoS at a signalized intersection was quantified based on the average control delay per vehicle in accordance with the Highway Capacity Manual (HCM), 7th Edition (2022) [100]. The relevant parameters, such as the peak hour factor, saturation flow rate, and critical lane group volumes, were applied in Synchro for signal optimization to ensure consistency with HCM-based delay and capacity estimation.

3.3. Analysis Tools

Delay and LoS at an intersection were assessed using Synchro and PTV VISSIM 2020. Synchro, a macroscopic optimization tool, was used to optimize signal timings and conduct capacity analysis for the base case of 0% AVs, applying the settings in Table 2. The optimized timings were then programmed into VISSIM 2020, a microscopic traffic simulation software developed in collaboration with the European Commission’s CoExist project, which models AVs with cautious, normal, and aggressive driving profiles based on empirical and field data [101,102]. VISSIM was used to simulate traffic under varying AV penetration rates, with performance measured by average vehicle delay and the corresponding LoS for each scenario.

Table 2.

Intersection settings for Synchro.

3.4. Integrated Microsimulation Framework

This paper formulated and utilized a detailed microsimulation framework for the evaluation of SAE Level 5 AV deployment scenarios at a typical urban signalized intersection, with two layouts, as shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2. The first layout was simulated with traffic volumes of 3500, 4500, and 5500 vph, while the second one considered traffic volumes of 5000, 6000, and 7000 vph. Both intersection layouts were evaluated under variations in approach distribution and left-turn percentages. The full range of penetration rates from 0% to 100% was modeled to account for both marginal and cumulative benefits and saturation effects across a large operational envelope.

This study’s contribution lies in integrating high-fidelity SAE Level 5 AV behavioral modeling with realistic urban intersection geometries, optimized baseline signal control, and a factorial experimental design covering 324 distinct scenarios. It directly addresses the research gap on AV impacts at signalized intersections with mixed traffic, incorporates operational constraints reflective of urban conditions, and links findings to policy frameworks. The following research questions support the aim:

1: How do different AV penetration rates (0–100%) affect average delay and level of service at an urban signalized intersection under varying traffic conditions?

2: How do traffic volume, approach distribution, and left-turn percentage interact with AV penetration to influence operational performance?

3: What are the sustainability and policy implications of the observed performance changes to the deployment strategies?

4. Experimental Design

The experimental setup in this research considered different parameters that are more likely to occur in real-life scenarios at traffic signals. The varying factors considered in this research were the total traffic volume at the intersection, the traffic distribution in each approach, the percentage of left-turn movement, and different penetration rates of AVs. The primary aim of this representation was to assess most of the critical cases in the real world. This was to have a better understanding of the impacts of AVs on the performance of traffic signals.

4.1. Percentages of AVs Considered

The analysis considered AV penetration rates from 0% to 100% in 20% increments, reflecting the expected gradual market adoption. Previous studies on mixed traffic suggest that AV shares below 20% have minimal impact, while 20% intervals provide clearer insights into performance trends [77,86,87,103,104,105].

4.2. Traffic Volume and Distribution Scenarios

The total volumes selected for the intersection were to reflect three congestion levels for the proposed signalized intersection. After testing various volumes, three representative values were selected to reflect typical traffic conditions. The three volumes were moderate, high, and very high congestion. The three total volumes for the first layout of the intersection were 3500, 4500, and 5500 veh/h, while these volumes were 5000, 6000, and 7000 veh/h, for the second layout, respectively. These values were selected using the intersection delay results for each case. To maintain a consistent approach to estimate the congestion levels, three base cases were defined with an equal proportion of the total traffic in all approaches. The turning movements were defined as 25% left turns (east–west) and 30% left turns (north–south), 65% through movements (east–west) and 60% through movements (north–south), and 10% right turns on all approaches. The three base cases were named B.I.1, B.II.2, and B.III.3. Each case was then evaluated using Synchro under the stated assumptions. The selected volumes resulted in an LoS “D” for moderate congestion, “E” for high congestion, and “F” for very high congestion levels.

The selected traffic volumes were simulated alongside varying factors, including different traffic distributions on each approach and varying left-turn percentages in the dominant traffic directions. These distributions and turn percentages, based on previous research on signalized intersections [86], aimed to represent a wide range of realistic traffic scenarios.

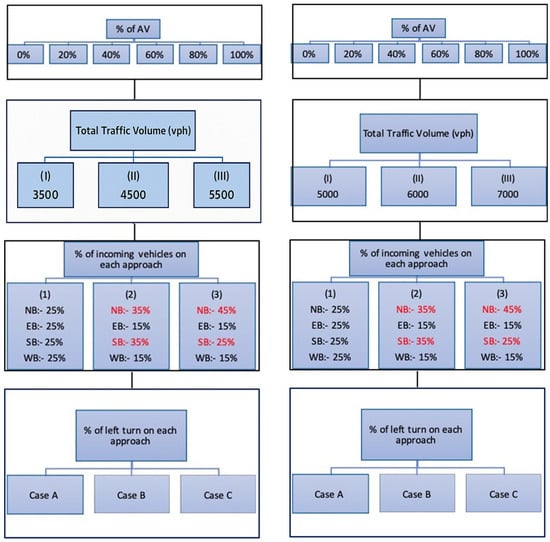

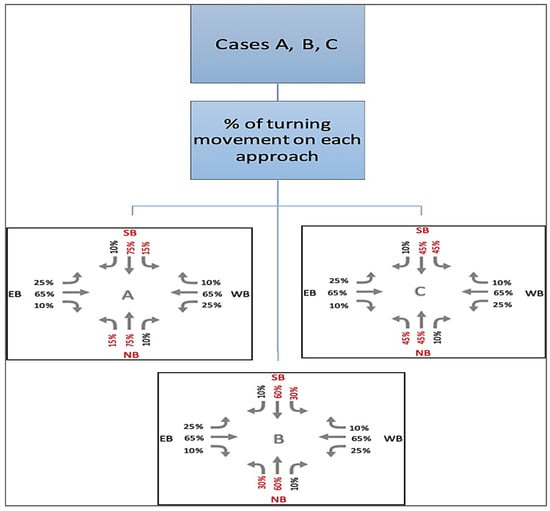

Figure 3 and Figure 4 present all cases tested in this study for a typical isolated four-leg intersection. The identification number for each simulation run was defined through different levels. The first level represents three variations of left-turn percentages (A, B, and C) on the two dominant traffic directions (northbound and southbound), as illustrated in Figure 4. The second level reflects the total traffic volume (I, II, or III), as shown in Figure 3. The third level represents three traffic distribution patterns, 1, 2, and 3, as shown in Figure 3. The latter two distributions (2 and 3) approximate typical urban intersections where a major road intersects with a minor road during peak hours.

Figure 3.

Schematic showing different scenarios analyzed. Values highlighted in red indicate unbalanced directional traffic scenarios, where the northbound (NB) and southbound (SB) approaches carry greater proportions of the total volume to simulate peak-directional demand conditions.

Figure 4.

Representation of cases A, B, and C. Values highlighted in red denote unbalanced directional traffic conditions, where northbound (NB) and southbound (SB) approaches carry higher proportions of turning volumes to emulate peak-directional demand and evaluate intersection performance under asymmetric loading.

The fourth level corresponds to the different AV penetration rates described earlier. For example, the simulation identification A.I.1-20% for the first intersection layout configuration denotes a scenario where

- A indicates a left-turn percentage of 15% in the dominant traffic direction.

- I corresponds to a total intersection volume of 3500 vph.

- One represents equal traffic distribution of 25% per approach.

- Twenty percent specifies the AV penetration rate being tested.

The various combinations of traffic distributions were selected to ensure that the signalized intersection studied was as close as possible to real-life conditions. A total of 27 traffic distribution cases were simulated for each AV penetration rate for a total of 324 cases to study the impact of the increasing share of AVs on intersection performance. Each simulation was run for one hour using five different random seeds, with the trimmed mean of the three central results used for comparison, consistent with previous similar studies [86,87].

Scenario identification key (example: A.I.1-20%)

Each scenario label had four components:

- Left-turn percentage in dominant approaches: A = 15%, B = 30%, and C = 45%.

- Total intersection volume level: I = low (first layout: 3500 vph; second layout: 5000 vph), II = moderate (4500/6000 vph), and III = high (5500/7000 vph).

- Approach distribution pattern: 1 = balanced (25% per approach), 2 = two-dominant approaches, and 3 = single-dominant approach.

- AV penetration: suffix “20%” indicated the AV share in that run (0–100% in 20% steps).

The decoded example (A.I.1-20%) represented 15% left turns in dominant approaches; a low total volume (3500 vph in layout 1 or 5000 vph in layout 2); a balanced 25% approach distribution; and 20% AV penetration.

In order to better facilitate the comparative analysis, combinations of cases were created so as to focus on the most salient patterns found in the data and, as such, offer a more lucid perspective on the repercussions of AVs on signalized intersection performance. These groupings or “groups” were specifically formulated to neutralize the effect of pivotal variables (thereby ensuring comparability across the different cases) and allow for their isolated influences on the different performance metrics to be fully discerned. Table 3 depicts the structure of the groupings (across the three group levels) as well as the nomenclature adopted for each group. The groups were formed by fixing all variables except for one, which was varied as the AV penetration rate also changed. In groups A1, B1, etc., the left-turn percentage was held constant, and the total intersection volume was modified in order to increase traffic demand; in groups ABC.I.1, ABC.II.2, etc., the total traffic volume was fixed, and the left-turn percentage was increased so as to evaluate its impact on signal performance.

Table 3.

Proposed combination and groups and their notations.

4.3. Modeling AVs

Simulations of mixed traffic of AVs and HDVs were performed in the PTV VISSIM 2020 software to study how the different levels of AV penetration rates (0–100% in 20% increments) impact the operational performance of signalized intersections. AVs were modeled at SAE Level 5 automation to remove the human driver from the simulation environment, as the AV models in VISSIM do not consider the implicit stochastic car-following and lane-changing behaviors to represent human imperfection [102,106].

Table 4 highlights the main differences between the HDV, normal AV, and aggressive AV. In this study, the normal AV driving profile was chosen as it is similar to HDVs and suitable for urban intersections [102].

Table 4.

Comparison of driving behavior of HDVs and AVs.

5. Results and Analysis

The analyses were carried out to determine the effect of different AV penetration rates on the performance of a signalized intersection under different traffic conditions. Signal timings were first optimized in Synchro to minimize the average intersection delay for the 0% AV case following the procedures described in the HCM [100]. The optimized timings were then adopted in VISSIM 2020 to capture the intersection performance for all of the AV penetration scenarios. The average delay per vehicle was the performance measure used to quantify the impact of different market shares of AVs on the intersection operation while accounting for different traffic volumes, approach distributions, and left-turn percentages on the dominant approach.

5.1. Signal Optimization and Intersection Delay

Synchro was used to optimize the signal timings for the first intersection layout configuration under the given traffic conditions. The delays for the intersection, for the 0% AV cases, and all cases are given in Table 5. The corresponding results for the second intersection layout configuration are presented in Table 6. As expected, the results show that the average delay increased as volume increased and as the left-turn percentage in the dominant approach increased.

Table 5.

Synchro results for the base case scenario of 0% AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 6.

Synchro results for the base case scenario of 0% AVs (second intersection layout configuration).

Delays across groups ABC1, ABC2, and ABC3 increased on average with increasing left-turn percentages, with the largest increase in delay at 45% LT demand. The differences between 15% and 30% LT were small, especially at higher volumes when the two-lane design was already at or near saturation. Groups ABC2 and ABC3 had a concentration of demand in two approaches or one approach, respectively, and Synchro’s tendency to allocate green time to meet demand replicated the delay pattern observed in ABC1. The delay across all three groups increased with the total demand volume, but the three-through lane intersection always performed best.

5.2. Microscopic Simulation

The intersection scenarios were simulated using VISSIM 2020 to understand the impact of increased AV penetration. VISSIM is a stochastic microsimulation package with the ability to simulate both HDVs and AVs and their interactions. The 0% AV cases were also re-evaluated with VISSIM, as the output generated by the deterministic software Synchro does not account for differences in traffic distribution and driver behavior. A microsimulation model was built for each. Each scenario was run five times, with the minimum and maximum being removed from the dataset, and the average of the remaining three used for analysis. Cases followed the A, B, and C configuration for left-turn percentages (15%, 30%, and 45%) with groups 1, 2, and 3 representing balanced, two-dominant, and single-dominant approach distributions, respectively. The VISSIM delay outputs were post-processed to determine the effects of AV penetration, traffic volume, turning movements, and approach distributions on intersection performance for both two- and three-lane geometries [86,87].

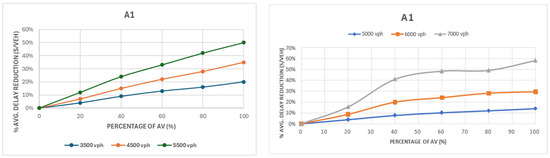

Table 7 and Table 8 present the delay comparisons for groups A1, A2, and A3, where the left-turn percentage was fixed at 15% in the dominant approaches and 25% in the others. The difference between groups A1, A2, and A3 lies in the traffic distribution across approaches, as described in the experimental design. In all cases, increasing AV penetration reduced the average delay, though the magnitude varied with both total volume and traffic distribution. Larger reductions were observed at higher volumes and in more unbalanced patterns (such as group A3), reflecting the capacity of AVs to improve efficiency under saturated and asymmetric demand conditions. Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the delay comparisons for each group.

Table 7.

Results for group A under varying percentages of traffic volume and AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 8.

Results for group A under varying percentages of traffic volume and AVs (second intersection layout configuration).

Figure 5.

Comparison of delay for group A1: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

Figure 6.

Comparison of delay for group A2: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

Figure 7.

Comparison of delay for group A3: first intersection layout configuration (left) and first intersection layout configuration (right).

Figure 5 shows the delay comparison for group A1 for the two intersection layouts. Group A1 included the cases with 15% left turns in the major approaches and an equal traffic distribution of 25% in each approach. Performance improvements with higher AV penetration were more consistent, as indicated in Figure 5. Up to 20% delay reduction was observed at 3500 vph and more significant improvements at higher traffic volumes, up to nearly 50% at 5500 vph in the first intersection layout case, and 58% at 7000 vph in the second layout. The more significant improvement with higher AV penetration at higher traffic volumes was likely related to the lower AV headways releasing more capacity before it was saturated. We observe that AVs can potentially lead to a significantly lower average delay in balanced cases with a low percentage of left-turn traffic. The improvement percentage increased directly with the penetration rate and the overall volume.

Figure 6 illustrates the delay comparison for the A2 groups for the two layouts. Group A2 (35% of traffic in two major approaches and 15% in minor approaches) had a greater range of delay reductions than A1, peaking at 62% for 5500 vph in the first layout case and 44% for 7000 vph in the second layout case. For the second layout, the maximum rate of improvement change was seen at 0–40% AVs, after which it tapered off at high volumes near capacity. The improvement at 6000 vph was greater than at 7000 vph due to oversaturation effects, which was also consistent with previous studies [86,87].

Figure 7 shows the comparison of delay for group A3, which considered heavily unbalanced traffic (45% in one major approach, 25% in the other, and 15% left turns), and achieved the largest delay reductions, up to 78% at 5500 vph with 100% AVs in the first layout and 46% at 6000 vph in the second layout case. The first layout showed a consistent and approximately linear rate of improvement. Meanwhile, the improvements for the second layout were steepest between 0 and 40% AVs and then became more linear at higher penetrations. Similar to A2, the benefits at 6000 vph exceeded those at 7000 vph, as oversaturation and spillback at very high volumes limit further gains. These results align with previous studies [66,104].

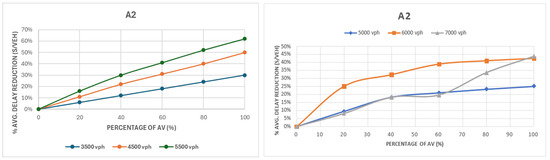

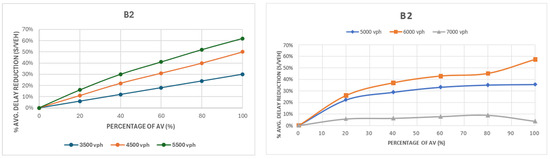

Table 9 and Table 10 present the delay comparisons for groups B1, B2, and B3, where the left-turn percentage was fixed at 30% in the dominant approaches and 25% in the others. The groups differed only in their traffic distribution, as described in the experimental design. For the first layout of the intersection, the average delay decreased steadily with higher AV penetration, with the greatest reduction of up to 75% observed in case B.III.3 (5500 vph). For the second layout of the intersection, similar trends were observed, though one case (B.III.2) showed a delay increase between 80% and 100% AVs, reflecting instability at oversaturated volumes. Overall, improvements were more substantial at higher volumes and penetration rates, confirming the strong interaction between traffic load, distribution, and AV share.

Table 9.

Results for group B under varying percentages of traffic volume and AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 10.

Results for group B under varying percentages of traffic volume and (second intersection layout configuration).

Figure 8 shows the comparison of delay for group B1 with 30% left turns and a uniform 25% traffic distribution, showing consistent delay reductions as AV penetration increased. At 5500 vph in the first intersection layout, delays fell by about 50%, while at 7000 vph in the second layout case, the reduction reached 60%. Improvements were mainly linear at lower volumes, with sharper gains between 0 and 40% AVs. At higher volumes, spillback from heavy left-turn demand limited further benefits, though the cooperative behavior of AVs still provided noticeable capacity gains at 80–100% penetration.

Figure 8.

Comparison of delay for group B1: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

Figure 9 presents the comparison of delay for group B2 with 30% left turns and an uneven distribution (35% in the two major approaches and 15% in the minor ones), showing strong delay reductions at moderate-to-high volumes. Reductions reached 62% at 5500 vph for the first intersection layout and 57% at 6000 vph for the second intersection layout. Gains were uniform at lower volumes but peaked before capacity was reached, while at 7000 vph, improvements fell to below 10% due to oversaturation and spillback on the left-turn lanes. In some cases, at high AV penetration (80–100%), delays even increased slightly, reflecting the relatively conservative AV behavior under oversaturated turning conditions compared with HDVs.

Figure 9.

Comparison of delay for group B2: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

Figure 10 shows the comparison of delay for group B3 with 30% left turns and uneven traffic (45% in one major approach and 25% in the other). The results show the largest benefits at moderate volumes, with delay reductions of up to 78% at 5500 vph and 49% at 5000 vph. As the figure shows, improvements were highest between 20 and 40% AVs but flattened or became irregular at higher penetrations due to oversaturation and spillback effects. At 6000–7000 vph, benefits were limited, and simulation anomalies under extreme congestion further constrained results.

Figure 10.

Comparison of delay for group B3: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

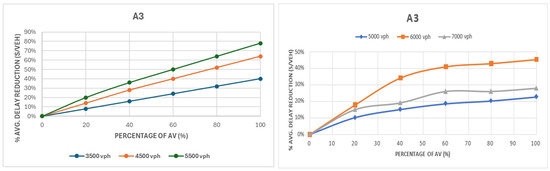

Table 11 and Table 12 present the delay comparisons for groups C1, C2, and C3, with left turns fixed at 45% in the dominant approaches and 25% in the others. The groups differed only by traffic distribution, as described in the experimental design. For both layouts of the intersection, average delays decreased with higher AV penetration, though the magnitude varied with both volume and distribution. In a few oversaturated cases (C.III.2 and C.III.3), delays increased slightly from 80% to 100% AVs, reflecting instability at very high penetration rates.

Table 11.

Results for group C under varying percentages of traffic volume and AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 12.

Results for group C under varying percentages of traffic volume and AVs (second intersection layout configuration).

The trends of delay variations for C1, C2, and C3 were similar to those observed for B1, B2, and B3.

Table 13 and Table 14 show the effect of increasing left-turn percentages (15%, 30%, and 45%) under fixed volumes and traffic distributions. Groups ABC.I, ABC.II, and ABC.III represent equal, moderately uneven, and highly uneven distributions. Delays decreased with higher AV penetration in all cases, though gains were small at low volumes, moderate at medium volumes, and largest at high volumes, with reductions exceeding 70% in some scenarios at 100% AVs.

Table 13.

Results for groups ABC under varying percentages of left-turn movement and AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 14.

Results for groups ABC under varying percentages of left-turn movement and AVs (second intersection layout configuration).

5.3. LoS Comparison

Table 15 and Table 16 summarize the level of service (LoS) results across all scenarios for the first and second intersection layouts, respectively. The LoS, calculated from the control delay following HCM 2022, reflects the combined effects of the signal phasing, cycle length, and volume-to-capacity ratio. The results show that higher left-turn percentages significantly degrade LoS, limiting the benefits of AV penetration under oversaturated conditions where spillback and geometric constraints dominate. Case A consistently outperformed B and C, while evenly distributed flows (case 1) achieved better LoS than unbalanced distributions (cases 2 and 3). The color coding from green (C) to red (F) provides an intuitive view of how LoS rapidly declined as both left-turn demand and traffic volume increased.

Table 15.

Delay and LoS comparison for all of the 27 cases, at each penetration rate of AVs (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 16.

Delay and LoS comparison for all of the 27 cases, at each penetration rate of AVs (second intersection layout configuration).

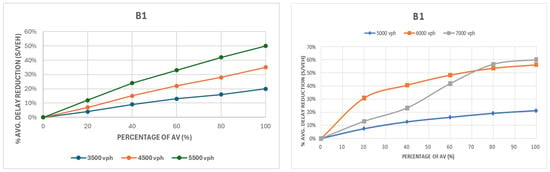

5.4. Impact of Aggressive Behavior of AVs

AVs were first modeled with normal driving behavior, which assumes conservative attributes suitable for mixed-fleet conditions. In some extreme cases with high volumes and heavy left-turn demand, 100% AV penetration unexpectedly increased delay. These cases were re-simulated using aggressive AV behavior, defined by a shorter standstill distance, a reduced following distance, and higher acceleration and deceleration rates. The results shown in Table 17 and Table 18 indicate that aggressive behavior reduced the delay in all critical cases, with improvements ranging from 4% to over 30%. The largest gain was in case B.III.2 at 5500 vph and full AV penetration, where the delay dropped by 18%. This indicates that more dynamic AV strategies can deliver extra efficiency under severe congestion.

Table 17.

Improvement in delay after applying aggressive AV driving behavior (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 18.

Improvement in delay after applying aggressive AV driving behavior (second intersection layout configuration).

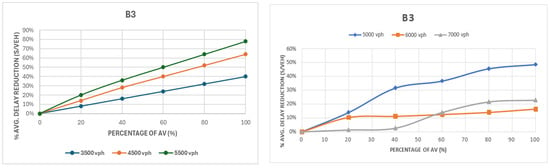

Case C.III.3, with 45% left turns, showed limited gains under normal AV behavior, with delay reductions plateauing at high penetration rates. To test whether driving style influenced this, the case was re-simulated with aggressive AV behavior at 100% penetration (Figure 11, left and right). The results showed improvement, with the average delay reduction rising from about 19% to 23–25%. The gains at lower penetration levels were modest, since interactions with human-driven vehicles still constrained flow. These findings suggest that in fully automated conditions, more dynamic AV parameters, shorter standstill distances, reduced following gaps, and quicker acceleration can unlock extra efficiency, though pedestrian and cyclist phases must be preserved to ensure safety.

Figure 11.

Case C.III.3 revisited with aggressive driving behavior at 100% AV: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

5.5. Average Delay Reduction Across All Cases

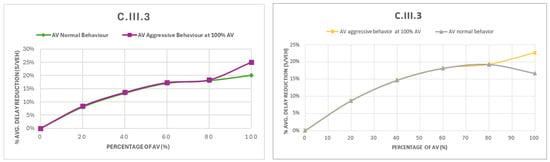

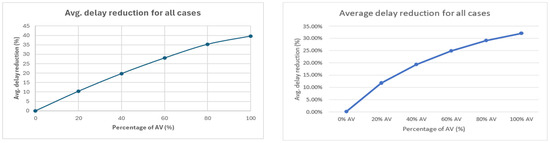

Table 19 and Table 20 summarize the average percentage reduction in delay across all evaluated cases, using 0% AV penetration as the benchmark case. The results show that AVs can reduce average delay by up to 32–40% at full penetration. The greatest incremental improvement occurred between 0% and 20% AVs, with reductions of around 10%. Beyond this early stage, the rate of improvement declined steadily, dropping to 8–9% between 20 and 40% AVs, about 5–7% between 40 and 60% AVs, 4–5% between 60% and 80% AVs, and only 3–4% from 80% to 100% AVs. This indicates that the most significant efficiency relative gains were realized during the early adoption phase, while benefits tapered off as saturation was approached.

Table 19.

Average delay reduction combining 162 simulations (first intersection layout configuration).

Table 20.

Average delay reduction combining 162 simulations (second intersection layout configuration).

Figure 12 (left and right) shows the average delay reduction across all cases as AV penetration increased. Consistent with earlier studies [86,87], the largest benefit occurred at 100% AVs, with an average reduction of around 40%. While the overall trend was nearly linear, the actual range of improvements varied widely across scenarios (4–60%), depending on traffic volumes, turning percentages, and operating conditions.

Figure 12.

Average delay reduction combining 162 scenarios: first intersection layout configuration (left) and second intersection layout configuration (right).

6. Discussion of the Approach, Limitations, and Future Work

The following limitations may have affected the results and should be considered when interpreting them. The modeling of AV behavior in VISSIM, although calibrated to alternative driving behavior profiles (cautious, normal, or aggressive) as an output of a previous European Commission-funded project, does not fully capture some real-world complexities, such as the interactions with HDVs during cooperative merging and other maneuvers, the potential variability in human driver reactions and behaviors in response to AVs, and the impact of weather conditions and poor visibility on AV performance. The simulation was not calibrated against real-world observed traffic data, as empirical data for AV operation at higher penetration levels are currently unavailable. This limitation reflects a common challenge in AV simulation studies and should be considered when interpreting the quantitative outcomes. This study focused on isolated intersections and did not consider network-wide effects, coordination, or adaptive signal control, which may influence AV benefits in real-world urban networks. In particular, the role of adaptive or cooperative signal control remains unexplored, even though such systems are increasingly deployed in urban networks and could amplify (or reduce) the marginal gains from AV penetration. It also did not explicitly consider environmental sustainability impacts, such as emissions or energy consumption. Although these impacts may be indirectly affected by changes in delay, direct quantification would provide a more complete assessment. To address this limitation, future research should integrate explicit environmental performance modeling within the simulation framework. This could involve coupling the VISSIM outputs with established emission and energy consumption models, such as MOVES, COPERT, or VERSIT+, to capture changes in fuel use, carbon dioxide, and pollutant emissions under varying traffic scenarios. Such integration would enable a direct quantification of environmental effects beyond delay-based inference and align the analysis with the objectives of smart and sustainable cities, where operational efficiency is linked to measurable reductions in energy use and emissions. Future work should explicitly quantify emission reductions and energy savings from AV adoption, as such evidence would directly support policy frameworks like SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 13 (climate action).

Furthermore, the analysis assumed that AV technology and performance are consistent across all penetration levels. It did not consider transitional-phase effects, such as the evolution of AV software and algorithms, the potential coexistence of different levels of automation (SAE Levels 2–4), and the impacts of driver behavior and adaptation. Moreover, most near-term deployments will involve SAE Levels 2–4 rather than full automation, and mixed fleets of varying automation capabilities may produce different dynamics than those modeled here. Behavioral and social factors, such as mode shift, public perception, trust, and acceptance of AVs, which may strongly influence their actual uptake and performance, were not captured by the simulation. Finally, the simulation design only considered one intersection type. It is likely that the impact of AVs varies with intersection design and geometry, which should be explored in future work. It will also be important to consider intersections with unconventional geometries, multimodal crossings, and varying infrastructure quality, especially in low- and middle-income contexts where AV adoption pathways may differ.

Future work should aim to provide empirical calibration of AVs based on long-term field trials in mixed-traffic conditions. Operational assessment should also integrate a range of sustainability metrics and include more network-scale studies that can identify the broader effects across corridors and the city as a whole. Cross-context validation of these findings in varying road geometries, driving cultures, and regulatory environments, with a particular focus on low- and middle-income countries, would also be necessary to create a globally relevant and transferable evidence base. Through these efforts, future research can provide more robust and generalizable insights to support the global commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities) and SDG 13 (climate action). Ultimately, the findings call for a phased and context-sensitive deployment strategy, underpinned by rigorous evaluation and policy integration, to ensure AVs contribute meaningfully to resilient, sustainable, and inclusive urban mobility.

7. Conclusions and Recommendations

This study provides a comprehensive exploration of operational and policy considerations for the deployment of SAE Level 5 AVs at a typical urban signalized intersection. Utilizing both Synchro and PTV VISSIM to model the same intersection has allowed this study to account for both high-level, optimized control inputs from the HDV baseline modeled in Synchro, as well as for the granular vehicle-to-vehicle interactions in mixed HDV–AV traffic provided by PTV VISSIM. This has established a thorough and validated base model for both control-centric and microsimulation approaches that is reflective of the network and allows for fine-tuned and detailed behavior of AVs at the intersection to be investigated. This dual approach enhances the robustness of the findings and provides a methodological template that can be adapted in future urban AV evaluations.

The results of this study have shown that the introduction of SAE Level 5 AVs can be expected to have a beneficial impact on average delay at signalized intersections, with a potential total average delay reduction at 100% AV penetration of nearly 40%. The results of this study, however, also show that these benefits are not guaranteed to be evenly distributed across all AV penetration rates or across all intersection scenarios. The introduction of AVs resulted in the largest change in delay reduction when AV penetration increased from 0% to 20%, with the rate of reduction decreasing incrementally as AV penetration increased, with a delay reduction of around 4% when AV penetration increased between 80% and 100%. These findings are in line with a number of other simulation-based studies that have been highlighted in the literature review [78,87,103]. The relatively small increment in the percentage gain for AVs in the high penetration rates is expected to be due to the existence of geometric and other intersection-level constraints that cannot be overcome by AV technology, but also may be caused by residual vehicle-to-vehicle interaction that is not entirely eliminated by the SAE Level 5 AV penetration. It must also be noted that the benefit achieved in each scenario varied significantly, from one scenario performing consistently worse to one achieving a benefit exceeding 60% across all AV penetration rates. This variance in performance can be due to the characteristics of the intersection in each scenario, with the lower left-turn proportion and more equal approach volumes showing the highest benefits. This confirms that intersection-specific geometry and traffic composition are critical determinants of AV performance and that uniform deployment strategies may risk underperformance in many contexts. It is important to note, however, that many trial sites do not fit this description, with a number of high-turning-volume and oversaturated intersections likely to exist within typical urban areas. As a result, it is unclear whether the high performance seen in these scenarios could be replicated at trial sites or in reality. The limited generalizability of results from a single intersection trial site also points to the dangers of using isolated deployments as a basis for scaling AV technology across an urban area and calls into question how these results can be used to extrapolate to larger areas. In particular, the lack of benefit seen at many intersections with a high turning volume and oversaturated flows means that benefits are unlikely to be realized without localized fine-tuning to the traffic composition, intersection geometry, and control system capability. Therefore, staged deployment guided by empirical performance monitoring is essential to avoid misallocation of infrastructure investment.

In the context of policy and planning, the most significant finding of this study is that the deployment of AVs should be selective. As has been shown in the results, the greatest rate of improvement for the benefits can be achieved in the early stages of AV deployment in intersection scenarios that benefit most from these changes, without requiring AVs to reach 100% market penetration. These sites are prime targets for the early introduction of AVs. As AV penetration increases beyond these levels, additional measures may be required to achieve the same levels of improvement in change rates. These measures may include geometric redesigns, adaptive or cooperative signal control approaches, and dynamic lane allocation, among others. In this way, the deployment of AVs can be achieved in a way that quickly achieves significant benefits for the city in the early stages, and as AVs become more capable, additional improvements can be made as AV technology develops. Furthermore, the importance of links between simulation and real-world trials, also highlighted in the results, suggests that the behavior and characteristics of AVs should be carefully studied through these deployment strategies, and assumptions regarding AVs should be calibrated through empirical evidence and validated prior to any attempt to scale up these results. Policymakers should also recognize that AVs are not a stand-alone solution; integration with broader sustainable mobility strategies, such as public transport enhancement and demand management, will be crucial to maximize benefits while advancing climate and equity goals.

A summary of the findings from the literature review, the detailed results from this study, and recommendations for implementation in a policy-friendly format are shown in Table 21. This includes the list of targeted actions and the stakeholder responsible for their implementation, as well as the relevant deployment context for each of the measures.

Table 21.

Recommendations for AV deployment at urban signalized intersections.

The method presented in this research provides a more operationally relevant means of assessment, although necessarily at the cost of oversimplifying certain aspects of AV technology and traffic system behavior in the real world. Behavioral parameters for AVs (such as reaction time, gap acceptance behavior, and adherence to signal optimization) are calibrated on best-practice simulation settings rather than long-term, real-world operational data. Interactions with pedestrians and other road users, as well as more nuanced multi-modal conflicts, were beyond the scope of this study. The optimization process based on Synchro should also be considered a lower bound to the true potential for efficiency improvements, as the modeling was not used to investigate more adaptive, real-time control in the presence of AVs to its full extent, which could identify potential synergies with cooperative vehicle and signal technologies. A stronger integration of simulation outputs with adaptive signal systems in future studies would provide clearer operational guidance for cities considering AV deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.N. and A.A.; methodology, H.Y.M., M.N. and A.A.; validation, H.Y.M. and M.N.; formal analysis, H.Y.M. and M.N.; investigation, H.Y.M. and M.N.; resources, H.Y.M. and A.A.; writing—original draft preparation, H.Y.M.; writing—review and editing, M.N. and A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported, in part, by the Open-Access Program from the American University of Sharjah. The APC was funded by the same program.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This paper represents the opinions of the author(s) and does not mean to represent the position or opinions of the American University of Sharjah. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the School of Engineering at the University of Birmingham and the Department of Civil Engineering at the American University of Sharjah. Their resources and academic assistance were instrumental in the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

Autonomous Vehicle (AV), Human-Driven Vehicle (HDV), Vehicles per Hour (vph), Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Connected and Autonomous Mobility (CAM), Department for Transport (DfT), British Standards Institution (BSI), Level of Service (LoS), Global Positioning System (GPS), Vehicle-to-Everything (V2X), Cooperative Intelligent Transport System (C-ITS), Highway Capacity Manual (HCM), Microsimulation (MS), Intelligent Transport System (ITS), Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Passenger Car Unit (PCU), Signalized Intersection (SI), Travel Time Index (TTI), Synchro Traffic Signal Optimization Software (Synchro), PTV Verkehr In Stadten–Simulation (PTV VISSIM), United Kingdom (UK), European Commission (EC), aand Wiedemann 99 Car-Following Model (W99).

References

- United Nations. 68% of the World Population Projected to Live in Urban Areas by 2050, Says UN. 16 May 2018. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-revision-of-world-urbanization-prospects.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Rahmati, Y.; Talebpour, A. Towards a collaborative connected, automated driving environment: A game theory based decision framework for unprotected left turn maneuvers. In Proceedings of the IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 11–14 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gallo, M. Combined Optimisation of Traffic Light Control Parameters and Autonomous Vehicle Routes. Smart Cities 2024, 7, 1060–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarran, S.; Hassan, Y. Intersection Sight Distance in Mixed Automated and Conventional Vehicle Environments with Yield Control on Minor Roads. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, N.A.; Salmon, P.M. Human error taxonomies applied to driving: A generic driver error taxonomy and its implications for intelligent transport systems. Saf. Sci. 2009, 47, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumminello, M.L.; Zare, N.; Macioszek, E.; Granà, A. Assaying Traffic Settings with Connected and Automated Mobility Channeled into Road Intersection Design. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almusawi, A.; Albdairi, M.; Qadri, S.S.S.M. Integrating Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) into Urban Traffic: Simulating Driving and Signal Control. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkanani, M.; AlAjmi, A.; Alhayyan, A.; Esmael, Z.; AlBedaiwi, M.; Nadeem, M. A Self-Adaptive Traffic Signal System Integrating Real-Time Vehicle Detection and License Plate Recognition for Enhanced Traffic Management. Inventions 2025, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Qian, X.; Guo, S.; Yang, C.; Jones, S. Envisioning shared autonomous vehicles (SAVs) for 374 small and medium-sized urban areas in the United States: The roles of road network and travel demand. J. Transp. Geogr. 2025, 127, 104302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, W.F.; Fuchs, S. Multimodal Transport Networks; FRB Atlanta: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology Acceptance Model 3 and a Research Agenda on Interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorhauge, M.; Rich, J.; Mabit, S.E. Charging behaviour and range anxiety in long-distance EV travel: An adaptive choice design study. Transportation 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, T.; Cao, J. Examining motivations for owning autonomous vehicles: Implications for land use and transportation. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 102, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP. Sustainable Development Goals. 2015. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Taamneh, M.M.; Makahleh, H.Y. The prospects of adopting electric vehicles in urban contexts: A systematic review of literature. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 31, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNFCC The Paris Agreement. 2015. Available online: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Stilgoe, J.; Cohen, T. Rejecting acceptance: Learning from public dialogue on self-driving vehicles. Sci. Public Policy 2021, 48, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soteropoulos, A.; Berger, M.; Ciari, F. Impacts of automated vehicles on travel behaviour and land use: An international review of modelling studies. Transp. Reviews 2019, 39, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sietchiping, R.; Permezel, M.J.; Ngomsi, C. Transport and mobility in sub-Saharan African cities: An overview of practices, lessons and options for improvements. Cities 2012, 29, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2018. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565684 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Del Rosario, L.; Laffan, S.W.; Pettit, C.J. The 30-min city and latent walking from mode shifts. Cities 2024, 151, 105166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimbault, J.; Batty, M. Estimating public transport congestion in UK urban areas with open transport models. In Proceedings of the 29th GISRUK, Cardiff, UK, 14–16 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Thill, J.-C. Impacts of connected and autonomous vehicles on urban transportation and environment: A comprehensive review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 96, 104649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pojani, D.; Stead, D. Sustainable Urban Transport in the Developing World: Beyond Megacities. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7784–7805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkin, J.; Zhang, X. Urban networks and autonomous vehicles. In Cities for Driverless Vehicles; ICE Publishing: Miami Lakes, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, G.N.; Tsappi, E. Development of an Active Transportation Framework Model for Sustainable Urban Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. Implementing Sustainable Urban Travel Policies in China. In Proceedings of the International Transport Forum, Leipzig, Germany, 25–27 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Othman, K. Exploring the implications of autonomous vehicles: A comprehensive review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solutions 2022, 7, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuuyandja, H.; Pisa, N.; Masoumi, H.; Chakamera, C. A systematic review of the interrelations of urban form and mode choice in African cities. J. Transp. Land Use 2024, 17, 855–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S.; de Winter, J.; Kyriakidis, M.; van Arem, B.; Happee, R. Acceptance of Driverless Vehicles: Results from a Large Cross-National Questionnaire Study. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 5382192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordhoff, S.; Kyriakidis, M.; van Arem, B.; Happee, R. A multi-level model on automated vehicle acceptance (MAVA): A review-based study. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci. 2019, 20, 682–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordfjærn, T.; Egset, K.S.; Mehdizadeh, M. “Winter is coming”: Psychological and situational factors affecting transportation mode use among university students. Transp. Policy 2019, 81, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordbakke, S.; Schwanen, T. Transport, unmet activity needs and wellbeing in later life: Exploring the links. Transportation 2014, 42, 1129–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouratidis, K.; Peters, S.; van Wee, B. Transportation technologies, sharing economy, and teleactivities: Implications for built environment and travel. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2021, 92, 102716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monios, J.; Bergqvist, R. The transport geography of electric and autonomous vehicles in road freight networks. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 80, 102500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milakis, D.; Arem, B.V. Policy and society related implications of automated driving: A review of literature and directions for future research. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2017, 21, 324–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makahleh, H.Y.; Ferranti, E.J.S.; Dissanayake, D. Assessing the Role of Autonomous Vehicles in Urban Areas: A Systematic Review of Literature. Futur. Transp. 2024, 4, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litman, T. Autonomous Vehicle Implementation Predictions: Implications for Transport Planning; Victoria Transport Policy Institute: Victoria, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- D’APuzzo, M.; Nardoianni, S.; Cappelli, G.; Nicolosi, V. Towards the Development of Injury Matrix: Preliminary Analysis Through Multi-body Codes for Vulnerable Users. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 62–79. [Google Scholar]

- SAE International. SAE Levels of Driving Automation. 3 May 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/blog/sae-j3016-update (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- SAE International. Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles. 30 April 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/j3016_202104/ (accessed on 13 February 2025).

- NHTSA. Automated Vehicles for Safety. 2023. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/vehicle-safety/automated-vehicles-safety (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- NHTSA. Levels of Automation. 2023. Available online: https://www.nhtsa.gov/document/levels-automation (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Bansal, P.; Kockelman, K.M.; Singh, A. Assessing public opinions of and interest in new vehicle technologies: An Austin perspective. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 67, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diba, D.S.; Gore, N.; Pulugurtha, S.S. Integrating Autonomous Shuttles: Insights, Challenges, and Strategic Solutions from Practitioners and Industry Experts’ Perceptions. Futur. Transp. 2025, 5, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, F.; Axhausen, K.W. Predicting the use of automated vehicles. [First results from the pilot survey]. In Proceedings of the 17th Swiss Transport Research Conference, Monte Verità Ascona, Switzerland, 17–19 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Arup. Research Insights into an Autonomous Future: Investigating the Potential and Merits of Connected and Automated Mobility for Public Transport. 2023. Available online: https://www.arup.com/globalassets/downloads/insights/r/research-insights-into-an-autonomous-future.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Fonzone, A.; Fountas, G.; Downey, L. Automated bus services–To whom are they appealing in their early stages? Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 34, 100647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonzone, A.; Fountas, G.; Downey, L.; Olowosegun, A. How Autonomous Bus Trials Affect Passengers’ Views: Exploring The Gap Between Pre-Ride Expectations and Real Word Experience. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 115, 103311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stagecoach. Ferrytoll to Edinburgh Park with AB1. Available online: https://www.stagecoachbus.com/promos-and-offers/east-scotland/autonomous-bus (accessed on 8 July 2025).

- BBC. UK’s First Driverless Bus Begins Passenger Service in Edinburgh. 15 May 2023. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-65589913 (accessed on 6 July 2025).

- Ohmio. The Future of Autonomous Transport. Available online: https://www.ohmio.com/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Waymo LLC. That’s a Wrap! Waymo’s 2024 Year in Review. 18 December 2024. Available online: https://waymo.com/blog/2024/12/year-in-review-2024 (accessed on 18 March 2025).

- WeRide Inc. WeRide to Announce Fourth Quarter and Full Year 2024 Financial Results. 4 March 2025. Available online: https://ir.weride.ai/news-releases/news-release-details/weride-announce-fourth-quarter-and-full-year-2024-financial (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Innovate UK. SCALE. Available online: https://iuk-business-connect.org.uk/projects/connected-automated-mobility/scale/ (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- ZENZIC. SCALE. Available online: https://zenzic.io/innovation/deployment/scale/ (accessed on 14 April 2025).

- Zenzic. Self-Driving Shuttle Route Goes Live in Solihull. 19 March 2025. Available online: https://zenzic.io/news/self-driving-shuttle-route-goes-live-in-solihull/ (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Solihull Metropolitan Borough Council. SCALE. 2024. Available online: https://www.solihull.gov.uk/about-solihull/scale (accessed on 23 March 2025).

- Solihull Council. SCALE Route Map. Available online: https://www.solihull.gov.uk/sites/default/files/2025-03/SCALE-route-map.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- Solihull Council. Self-Driving Shuttle Route Goes Live in Solihull. 19 March 2025. Available online: https://www.solihull.gov.uk/news/self-driving-shuttle-route-goes-live-solihull (accessed on 12 April 2025).

- Martínez-Díaz, M.; Carbó, M.-M.M. Assessing User Acceptance of Automated Vehicles as a Precondition for Their Contribution to a More Sustainable Mobility. Sustainability 2024, 16, 895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenblatt, J.B.; Saxena, S. Autonomous taxis could greatly reduce greenhouse-gas emissions of US light-duty vehicles. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 860–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díaz, M.; Soriguera, F. Autonomous vehicles: Theoretical and practical challenges. Transp. Res. Procedia 2018, 33, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Huizenga, C. Implementation of sustainable urban transport in Latin America. Res. Transp. Econ. 2013, 40, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Hu, Z.; Liu, L. A survey on public acceptance of automated vehicles across COVID-19 pandemic periods in China. IATSS Res. 2023, 47, 482–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavieri, P.S.; Bhat, C.R. Modeling individuals’ willingness to share trips with strangers in an autonomous vehicle future. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2019, 124, 242–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janatabadi, F.; Ermagun, A. Empirical evidence of bias in public acceptance of autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 84, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haboucha, C.J.; Ishaq, R.; Shiftan, Y. User preferences regarding autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 78, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latham, A.; Nattrass, M. Autonomous vehicles, car-dominated environments, and cycling: Using an ethnography of infrastructure to reflect on the prospects of a new transportation technology. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 81, 102539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; de Winter, J.C.F. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 32, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.; Rashidi, T.H.; Rose, J.M. Preferences for shared autonomous vehicles. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 69, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraedrich, E.; Lenz, B. Societal and Individual Acceptance of Autonomous Driving. In Autonomous Driving; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 621–640. [Google Scholar]

- Fagnant, D.J.; Kockelman, K. Preparing a nation for autonomous vehicles: Opportunities, barriers and policy recommendations. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2015, 77, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, M.J. Three Revolutions: Steering Automated, Shared, and Electric Vehicles to a Better Future. In The Dark Horse: Will China Win the Electric, Automated, Shared Mobility Race? Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Coppola, P.; Silvestri, F. Autonomous vehicles and future mobility solutions. In Autonomous Vehicles and Future Mobility; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Şentürk Berktaş, E.; Tanyel, S. Effect of Autonomous Vehicles on Performance of Signalized Intersections. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04019061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, T. Recent Trends in the Public Acceptance of Autonomous Vehicles: A Review. Vehicles 2025, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.U.; Huang, Y.; Lu, P. A Review of Car-Following Models and Modeling Tools for Human and Autonomous-Ready Driving Behaviors in Micro-Simulation. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 314–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Public Transport. Autonomous Vehicles: Integration in Urban Transport Systems; International Association of Public Transport: Brussels, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- DfT. UK Connected and Automated Mobility: Call for Evidence. 16 July 2021. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/calls-for-evidence/the-future-of-connected-and-automated-mobility-in-the-uk-call-for-evidence/uk-connected-and-automated-mobility-call-for-evidence (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- DfT. Implementation and Process Evaluation: Wave 1 Report National Evaluation of Future Transport Zones. 10 March 2022. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66feb0f630536cb927482be2/dft-ftz-evaluation-ipe-wave-1.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2025).

- British Standards Institution. PAS 1881:2022 Assuring the Operational Safety of Automated Vehicles–Specification. BSI Standards Limited. 30 April 2022. Available online: https://www.bsigroup.com/en-GB/insights-and-media/insights/brochures/pas-1881-assuring-the-operational-safety-of-automated-vehicles/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- ADAS & Autonomous Vehicle International. SCALE Self-Driving Shuttle Trial Begins in Birmingham, UK. 20 March 2025. Available online: https://www.autonomousvehicleinternational.com/news/mobility-solutions/scale-self-driving-shuttle-trial-begins-in-birmingham-uk.html (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Greenham, S.; Workman, R.; McPherson, K.; Ferranti, E.; Fisher, R.; Mills, S.; Street, R.; Dora, J.; Quinn, A.; Roberts, C. Are transport networks in low-income countries prepared for climate change? Barriers to preparing for climate change in Africa and South Asia. Mitig. Adapt. Strat. Glob. Change 2023, 28, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.; Abdelfatah, A. Impact of using indirect left-turns on signalized intersections’ performance. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 44, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSahly, O.; Abdelfatah, A. Influence of Autonomous Vehicles on Freeway Traffic Performance for Undersaturated Traffic Conditions. Athens J. Technol. Eng. 2020, 7, 117–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talebpour, A.; Mahmassani, H.S. Influence of connected and autonomous vehicles on traffic flow stability and throughput. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 71, 143–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Yamamoto, T. Modeling connected and autonomous vehicles in heterogeneous traffic flow. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2018, 490, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Arem, B.; van Driel, C.J.G.; Visser, R. The Impact of Cooperative Adaptive Cruise Control on Traffic-Flow Characteristics. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2006, 7, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, E.; Olstam, J.; Schwietering, C. Investigation of Automated Vehicle Effects on Driver’s Behavior and Traffic Performance. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 15, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febbraro, A.D.; Sacco, N. Open Problems in Transportation Engineering with Connected and Autonomous Vehicles. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 14, 2255–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]