Highlights

- What are the main findings?

- Developed a blockchain-enabled Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platform using Hyperledger Fabric to enhance security, transparency, and operational efficiency in urban mobility systems.

- Demonstrated through load testing that the proposed system maintains consistent performance under varying data volumes and concurrent user requests, confirming its scalability for real-world applications.

- What is the implication of the main finding?

- Integrating blockchain technology into urban transportation systems can improve stakeholder collaboration and trust, leading to more efficient and secure smart city mobility solutions.

- The implementation suggests potential for expanding blockchain-enabled MaaS platforms to include freight logistics, supporting a unified, sustainable urban transportation ecosystem.

- Is data deletion possible in Hyperledger Fabric?

- Yes, but with limitations. Hyperledger Fabric’s storage is divided into the immutable blockchain ledger and the world state, which holds asset states. While data cannot be deleted from the ledger, an asset can be removed from the world state, with the deletion recorded on the ledger.

Abstract

As cities evolve into smarter and more connected environments, there is a growing need for innovative solutions to improve urban mobility. This study examines the potential of integrating blockchain technology into passenger transportation systems within smart cities, with a particular emphasis on a blockchain-enabled Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) solution. In contrast to traditional technologies, blockchain’s decentralized structure improves data security and guarantees transaction transparency, thus reducing the risk of fraud and errors. The proposed MaaS framework enables seamless collaboration between key transportation stakeholders, promoting more efficient utilization of services like buses, trains, bike-sharing, and ride-hailing. By improving integrated payment and ticketing systems, the solution aims to create a smoother user experience while advancing the urban goals of efficiency, environmental sustainability, and secure data handling. This research evaluates the feasibility of a Hyperledger Fabric-based solution, demonstrating its performance under various load conditions and proposing scalability adjustments based on pilot results. The conclusions indicate that blockchain-enabled MaaS systems have the potential to transform urban mobility. Further exploration into pilot projects and the expansion to freight transportation are needed for an integrated approach to city-wide transport solutions.

1. Introduction

In contemporary smart cities, incorporating innovative technologies into urban infrastructure is essential for enhancing transportation services and efficiently accommodating both passengers and goods [1]. One important aspect involves the development of multimodal transportation that combines different methods of transport into a unified system. This integration enhances mobility, traceability, and coordination. In this context, blockchain technology emerges as a solution that offers a transparent platform that boosts cooperation among various service providers and users in the transportation industry.

The goal of this research is to explore the development and implementation of a blockchain-enabled MaaS system. This study specifically examines whether blockchain technology can improve the security, transparency, and operational efficiency of urban mobility services, with a particular focus on payment and ticketing systems. The core hypothesis is that blockchain’s decentralized structure will enhance transaction integrity and stakeholder cooperation, creating a more efficient and secure urban transportation ecosystem. These systems use technology designed to transport people but can also handle shipping and moving goods. A key focus is on how blockchain technology can change payment and ticketing methods by enabling transactions between users and different service providers, such as buses, trains, bike-sharing programs, shipping companies, and ride-hailing services. Integrating this system into a city’s infrastructure, not only enhances user convenience but also helps support broader objectives like sustainability and better data security.

With the increasing need for secure, transparent, and efficient urban transport systems, various initiatives are exploring how blockchain can optimize MaaS platforms. A notable example is the European Union’s DELPHI project, which is part of Horizon Europe’s efforts to advance urban mobility and logistics using innovative technologies. This initiative aims to build a unified transport system that integrates multiple modes of transport, both for passengers and freight. By incorporating blockchain, the DELPHI project seeks to boost data security, streamline collaboration among stakeholders, and refine transport logistics. The project’s research focuses on establishing a blockchain-enabled platform that securely manages data across different transport modes. A key aspect is integrating payment and ticketing systems within urban mobility, which contributes to the development of the secure, transparent, and efficient MaaS framework that DELPHI envisions [2].

To fully understand blockchain’s potential in MaaS, it is important to examine both the general landscape of blockchain technology and the current challenges facing its integration into mobility systems. Issues such as scalability, security, and interoperability remain critical barriers, yet blockchain’s core features—decentralization, transparency, and immutability—position it as a promising solution for overcoming these obstacles.

The main part of this paper examines the design and structure of a MaaS system that uses blockchain technology. This section will delve into the technical aspects of the blockchain solution and its data model. We will also address challenges related to scalability to ensure the system’s technical robustness.

MaaS systems face several challenges, including security vulnerabilities, scalability issues, and inefficiencies. Our proposed blockchain-based platform directly addresses these concerns by creating a decentralized, secure, and scalable solution for urban mobility. Utilizing Hyperledger Fabric’s permissioned architecture and modular consensus mechanisms, the platform significantly boosts data security and transaction speeds, delivering reliable performance even under varying loads. Initially, the platform will focus on passenger transport, but future research will extend its application to freight logistics. This aligns with the DELPHI project’s broader objective of developing a unified and efficient transportation ecosystem.

2. Related Work

2.1. Blockchain Technology

Blockchain started as a proposal in 2008 [3] and was launched in early 2009. It operates as a public ledger, storing all committed transactions in a growing chain of blocks. Key traits of blockchain include decentralization, auditability, persistence, and anonymity. Blockchain uses the following advanced technologies: cryptographic hashes, asymmetric cryptography for digital signatures, and distributed consensus mechanisms. The use of these technologies supports the creation of decentralized transactions, resulting in cost reductions and efficiency improvements [4].

The blockchains’ information is stored in a linked chain of blocks, where each block is linked to the previous one and is secured through cryptographic methods. The peers in the network are linked through a P2P topology, thus ensuring the absence of a single point of failure. The network also uses a consensus mechanism to ensure universally agreed-upon transactions and block sequences. This maintains the consistency and the reliability of data across all nodes [5]. Every transaction on the blockchain is a discrete record in the blocks that make up this public ledger [6].

When smart contracts first emerged, as an integral part of blockchain technology, the second milestone in the blockchain began. This is referred to as Blockchain 2.0. Smart contracts are computer programs that run inside the blockchain network. These programs can express triggers, conditions, and business logic, enabling complex programmable transactions [7]. A smart contract was first mentioned under this name by computer scientist and cryptographer Nick Szabo, long before the blockchain concept was invented [8].

As the most well-known application of blockchain technology, Bitcoin is often mistakenly considered synonymous with blockchain itself. Despite this, the utility of blockchain extends beyond cryptocurrencies. The main trait of blockchain technology is the ability to facilitate transactions without relying on intermediaries. This means it can be used across various financial services such as online payments, digital assets, and remittances [9]. Smart contracts significantly expanded the range of industries that can benefit from this modern technology. Some new-use cases of blockchain beyond digital finance are logistics, supply chain management, IoT, healthcare, personal identity systems, music royalty processing, anti-money laundering initiatives, voting, agriculture, and many others [10,11,12].

There are two main types of blockchains: permissioned and permissionless. A permissioned blockchain restricts participation to authenticated members whose identities and privileges are managed by an authority or consortium. This approach offers greater privacy and performance but requires trust in the entity that governs membership. Hyperledger Fabric and R3 Corda are common examples of permissioned blockchains. By contrast, a permissionless blockchain is publicly accessible, allowing anyone to participate in validating transactions. This open model, exemplified by Bitcoin and Ethereum, fosters broad decentralization but may have lower throughput and less control over data visibility, making it suitable for more public or trustless scenarios.

Blockchain also stands ready to revolutionize other applications, such as art sales through digital media transfer, supply chains, the delivery of remote services like tourism and travel, and innovative platforms shifting computing towards data sources and distributed credentialing [13].

2.2. Blockchain in Public Transportation

References [14,15] explore the idea of MaaS and its potential to reshape contemporary transportation. The emphasis is on transitioning from owning private vehicles to utilizing a range of transportation options offered as services. It is emphasized that such a system could also accommodate and streamline goods transportation. MaaS combines different transport services into one unified, user-friendly platform. Blockchain technology can improve MaaS by offering a secure and transparent way to manage transactions and data across various transport modes. Additionally, the use of smart contracts and tokenization facilitates smoother integration and incentivizes users within the MaaS framework.

The application of blockchain technology in implementing a MaaS platform is explored in [16], with a focus on performance under various load scenarios. The authors explore and analyze two well-known and mature blockchain technologies: the Ethereum platform based on permissionless technology and the Hyperledger Fabric platform, which is based on permissioned technology. Ethereum offers decentralized consensus and broad developer support, but its permissionless nature can lead to scalability issues and slower transaction speeds, making it less suitable for high-throughput environments like urban mobility systems. In contrast, Hyperledger Fabric provides a permissioned network with customizable consensus mechanisms, better suited for environments requiring higher control, privacy, and performance, as found in MaaS systems. While both platforms can support MaaS, Hyperledger Fabric was chosen for its modularity, scalability, and enterprise-grade security features.

In [17], the authors propose a different method, utilizing the Hyperledger Indy [18] blockchain to create a multi-layered framework for a Smart Mobility Data Market (BSMD). This approach tackles major concerns like privacy, security, management, and scalability in the context of smart mobility. They point out the weaknesses of conventional data storage methods, such as central servers, which are prone to hacking and unauthorized data sharing. The BSMD framework offers a secure and transparent way for participants to share encrypted data on the blockchain, with transactions governed by mutually agreed-upon terms.

Enescu et al. [19] highlight the challenges and viable solutions related to the key subsystems of public transportation services. The effects of these services in densely populated urban areas are particularly emphasized. The study focuses on exploring blockchain-based innovations to enhance existing management platforms and drive future developments in the sector.

Multiple academic research works explore and propose implementations of blockchain technologies in various aspects of public transportation, like ticketing systems, supply chain management, data sharing and integration, and identity management.

The ticketing system can be streamlined by enabling secure, peer-to-peer transactions. Ticket issuance and ticket validation can be automated by leveraging smart contracts, reducing fraud and operational costs [20].

Public transport operators can use blockchain for tracking their assets (like vehicle fleet, parts, and components) throughout their lifecycle, ensuring accountability and efficiency in maintenance and operations [21].

Secure data sharing is crucial for modern smart city transportation systems. Blockchain can secure this process among different transportation agencies, resulting in better coordination and integration of services. This can lead to improved route planning and real-time updates for passengers [22].

Blockchain can provide secure digital means of user identification, allowing for seamless access to various transportation services without the need for multiple accounts or credentials [23].

There are several cities and organizations which have initiated pilot projects that intend to explore the benefits of blockchain in public transportation.

It is known that Dubai has the ambition to become a global leader in blockchain technology and smart transportation. The Dubai Roads and Transport Authority (RTA) is exploring blockchain for service efficiency and customer experience. It also seeks to promote transparency in operations. The Dubai RTA’s aim is to streamline various processes, such as vehicle registration, maintenance records, and driver licenses [24].

Singapore’s Land Transport Authority (LTA) collaborated with TransitLink to introduce a ticketing and fare management system utilizing blockchain technology. The system is designed to improve both efficiency and transparency. Commuters are able to use a mobile application or a contactless smart card powered by blockchain to pay for transportation across different modes. Fare validation becomes automated, enhancing the system’s connectivity, accountability, and transparency [25].

Estonia has implemented a smart ticketing system using blockchain technology to make public transportation smoother. Passengers can easily use the services of multiple transportation providers with a digital wallet, which securely keeps their tickets and payment information on a blockchain [26].

Denver’s Regional Transportation District (RTD) implemented a pilot program for public mobility which uses blockchain. “Go Denver”, the application that they developed, integrates various transit modes (buses, light rail, and ridesharing services) into one platform. Commuters can use it to plan, book, and pay for trips in one place [27].

The Seoul Metropolitan Government has incorporated blockchain technology into its public transportation systems as part of its ongoing smart city efforts. This technology boosts the security and transparency of fare payment systems by decentralizing and securing commuter data. Blockchain ensures that sensitive payment data are tamper-resistant and protected. By adopting blockchain, Seoul aims to increase trust and efficiency in public services, especially in transportation, where secure and transparent fare management is crucial. Seoul has also developed a cryptocurrency payment platform for public transportation (S-Coin), with plans to extend its use to other public services [28,29,30].

2.3. Blockchain Adoption Challenges

As blockchain technology continues to integrate into public transportation systems, the following challenges must be addressed: scalability concerns, interoperability between different platforms, evolving regulatory landscapes, high initial costs, and the need for user education and acceptance. Handling the high transaction volumes typical in public transportation systems can be a problem for most blockchain solutions [31]. The ever-increasing number of passengers requires a speed in transaction processing that is above what is currently available across the existing blockchain networks.

At the same time, various transportation agencies can use different platforms that are not compatible (not necessarily blockchain-based solutions). This failure to standardize the systems can prohibit the easy sharing of information and services [32].

The regulations around blockchain technology are still evolving. Public transportation groups might have legal issues with data privacy, security, and following current laws [33]. Dealing with these rules can delay the adoption of these modern technologies.

Even though blockchain has the potential to save a lot in terms of operational costs over time, the initial investment that it requires in the development of technology, upgrading infrastructure, and training is high. This could also deter smaller agencies from adopting blockchain solutions [34].

It is known that blockchain-based ticketing and transportation systems will only work successfully once users accept recent technologies. For that reason, training and support will be much more necessary and obligatory, increasing the overall cost of implementation [35].

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Blockchain Solutions

Hyperledger Fabric, Ethereum, R3 Corda, and Bitcoin are some of the most well-known blockchain technologies. Each of these solutions offers distinct features for industrial areas, including logistics, banking, and smart city transportation.

Bitcoin, the first public and permissionless blockchain, enables peer-to-peer digital transactions while ensuring limited data confidentiality in sensitive contexts. The proof-of-work consensus mechanism of Bitcoin can only handle about seven transactions per second and requires a lot of energy, making it unsuitable for high-throughput applications [36]. Additionally, Bitcoin’s narrow scripting capabilities limit the development of sophisticated smart contracts and thus curtail potential industrial use cases [37].

By contrast, Hyperledger Fabric possesses a permissioned network design and modular architecture, offering higher levels of scalability and privacy. Features like channels and private data collections permit confidential transactions limited to approved entities, safeguarding sensitive information. Its pluggable consensus mechanism further enhances throughput and facilitates customization for organizational needs [38].

Ethereum is a public, permissionless blockchain, therefore transaction data are inherently visible. This presents a disadvantage for sectors that require high confidentiality [39]. While the Enterprise Ethereum architecture attempts to solve the privacy concerns of permissioned networks, this solution adds complexity and falls short of Hyperledger Fabric’s extensive privacy controls [40]. Furthermore, Ethereum’s dependency on the Solidity programming language for smart contract development may present an extra challenge for developers used to more traditional programming languages [41].

R3 Corda is primarily tailored to financial services, prioritizing compliance and privacy by restricting transaction visibility to involved parties [42]. While this approach strengthens confidentiality, adapting Corda for broader applications might require significant modifications [43]. Its transaction-specific consensus mechanism ensures efficiency but could struggle to scale effectively in large MaaS systems.

Based on these distinctions, Hyperledger Fabric appears to be especially useful for smart city transportation applications because of its privacy restrictions, scalability, and flexible integration possibilities. Compared to Ethereum and R3 Corda, its main advantages are as follows:

- Fine-grained privacy controls: Channels and private data collection help ensure that only authorized participants can view sensitive information, which isimperative for sectors dealing with confidential data.

- High performance and scalability: Fabric’s architecture supports substantial transaction throughput, accommodating the operational intensity of large-scale industries.

- Modular, flexible design: Organizations can select the most suitable consensus mechanism and smart contract language, allowing each deployment to meet specific requirements.

- Enterprise integration: Compatibility with well-known programming languages and standardized APIs simplifies adoption and reduces both time and expense during rollout.

Such characteristics make Hyperledger Fabric particularly well suited for smart city initiatives, where operational efficiency, data protection, and interoperability are paramount.

3. Platform Design and Implementation

3.1. Functionality Overview

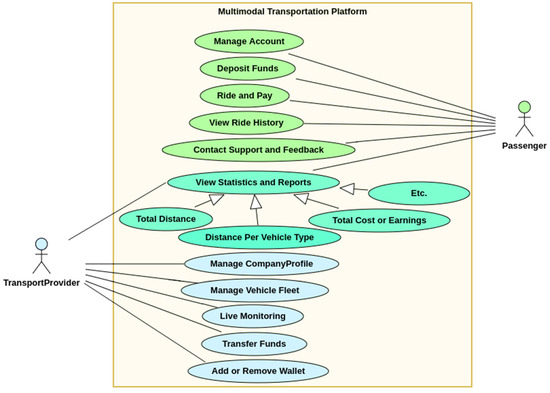

The primary goal of the proposed MaaS platform is to consolidate payments made to transport companies in a city into one application. This integration also allows the platform to track ride details and generate useful statistics for both transport operators and passengers. Figure 1 illustrates the main use cases of this solution.

Figure 1.

A use-case diagram of the proposed platform.

The proposed platform’s actors include transportation providers or companies, as well as entities that use the network to commute, such as individuals or items that can be conveyed by public transportation. Because these two user classes have access to different features, they will interact with the platform via various interfaces or client applications.

The user’s application employs a secure virtual wallet where passengers can deposit funds via external payment providers. This wallet facilitates internal payments within the platform, eliminating the need for cash or multiple tickets. Once the vehicle is boarded, the passenger will pay by transferring the due amount to the transport provider’s wallet. External payment providers are used to process deposits and withdrawals.

Passengers can view real-time information about their current rides, including the route progress and estimated time of arrival. The app also maintains a history of past rides for reference. The user application also allows passengers to rate their experiences, provide feedback, and access customer support for any issues encountered.

Both types of users will be able to see statistics, such as the distance per time period, earnings or costs per time period, the distance per vehicle, the distance per vehicle type, etc. For example, providing passengers with data regarding the vehicle type can encourage them to favor companies with a more environmentally friendly fleet for future rides. These insights can also assist providers in making informed decisions about fleet management and service improvements.

Like passengers, transport providers have one or multiple virtual wallets where they receive payments for services rendered. They can track earnings, process withdrawals, and manage financial transactions securely.

The providers can monitor active rides involving their vehicles, manage ride requests, and dispatch vehicles accordingly to optimize service delivery.

3.2. The System’s Architecture

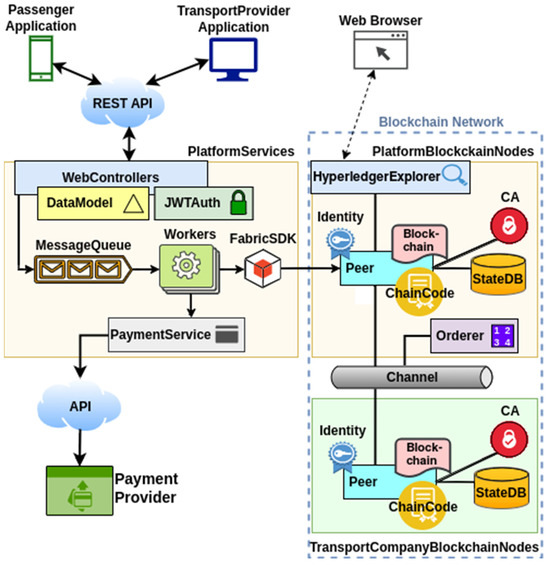

Figure 2 illustrates the system’s architecture, highlighting its main components. These include the client applications, the platform’s back-end, and the distributed ledger or blockchain network.

Figure 2.

The architecture of the system.

3.2.1. Client Applications

The system offers two distinct client applications: one designed for passengers and the other for transport providers. These apps enable users to engage with the platform’s key features, as outlined in the previous section, such as managing virtual wallets, processing payments, and viewing ride-related statistics.

By offering these tailored applications, the system ensures that both passengers and transport providers have the tools they need to efficiently interact with the platform, improving user experience and supporting more sustainable urban mobility practices.

3.2.2. Blockchain Network

The platform’s persistence layer is entirely built on blockchain. Multiple organizations maintain copies of both the state and the ledger databases, ensuring data immutability and security. Replicating the data across various network nodes enhances resilience against single points of failure.

The choice of blockchain technology is important for building an efficient and secure Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platform in smart cities. After assessing various blockchain options, Hyperledger Fabric v2.5 was selected for its enterprise-grade features. Numerous studies have highlighted its suitability for smart cities and transportation applications. R. Jabbar et al. [44] conducted an in-depth review of blockchain in public transport services. The study identified the advantages of Hyperledger Fabric regarding scalability, security, and privacy. Furthermore, Nguyen et al. [16] examined the integration of blockchain into MaaS platforms, demonstrating how Hyperledger Fabric enhances trust and transparency among stakeholders.

Some key features for choosing Hyperledger Fabric as the blockchain solution also include the following:

- Permissioned network with identity management: All participants are known and authenticated using certificates;

- Modular and configurable architecture: This allows for the pluggable implementations of components (such as consensus mechanism, state database, and services) [31];

- High throughput and scalability: Parallel execution of smart contracts (chaincode) and support for multi-channel networks [45];

- Support for privacy and confidential transactions: Confidential transactions between specific parties through private channels and data collections [46];

- Efficient querying and data management: State databases like CouchDB enable rich queries, real-time data access, and analytics [47].

The simplified architecture only includes two participating organizations within the network. While the Platform acts as the legal entity overseeing the system, the Transport Company serves as a second organization that endorses the transactions. Although participation is optional, it is strongly recommended that all transport providers actively engage in the network to help maintain the integrity and security of the shared data. As shown in the previous diagram, each organization operates its own peer, state database, and certificate authority.

The smart contracts or programs that define the business logic governing transactions on the blockchain network are called Chaincode in Hyperledger Fabric. This is the code that specifies the rules and procedures for interactions within the network, enabling the execution of transactions and the manipulation of the ledger’s state.

A peer is a node in the network that holds a copy of the ledger and smart contracts (chaincode). Peers are vital to the network as they endorse transactions, maintain the ledger, and take part in the consensus process.

The Certified Authority (CA) is responsible for user certificate management duties such as enrollment and revocation. Hyperledger Fabric is a permissioned blockchain network that uses X.509 standard certificates to establish rights, roles, and attributes for individual users. Users can execute queries or initiate transactions using channels that correspond to their permissions and roles.

The ledger is one of the primary components of Hyperledger Fabric, storing all transactions (state modifications) and the blockchain network state. The ledger layer includes the blockchain, an immutable record of all transactions, as well as the world state (StateDB). The blockchain is an ordered list of blocks that can only be written to, and are thus immutable, and the blockchain contains the transaction log, where every single transaction that has happened on the network is saved, providing a set of records crucial for auditability. The blockchain is stored on each peer in its file system. The world state keeps the state of all the assets in the ledger at any specific point in time. It is a key-value store containing the current values of the assets as modified by the transactions. They separate data retrieval and query operations from transaction history to facilitate efficient operations without requiring the whole transaction history to be processed. There are different pluggable implementations of state databases, like LevelDB or CouchDB, that work under Hyperledger Fabric. LevelDB, the default database, is an embedded key-value store and it can be used when simple key queries are sufficient. Alternatively, CouchDB provides rich queries regarding JSON stored documents, as well as complex data retrieval mechanisms like indexes [47,48].

A channel is a private and confidential communication line between specific network members, used to segregate transaction data and enable secure communication within a subset of the network.

The Ordering Service Node, or orderer, is essential for managing the process of grouping validated transactions into blocks, ensuring consensus, and adding these blocks to the distributed ledger.

Hyperledger Explorer is optional for Hyperledger Fabric, but it adds a lot of value by enhancing network transparency. It is an open-source tool developed under the Linux Foundation’s Hyperledger project specifically for monitoring and visualizing the ledger (blockchain) data within Hyperledger Fabric networks. This platform provides a web-based interface that allows users to efficiently access, query, and analyze transaction data, smart contracts, and network status [49,50].

3.2.3. Platform’s Backend

The system’s backend is built using Java with the Spring framework, which was selected for its robust enterprise features and wide adoption in scalable applications [51]. Java’s platform independence and extensive library support make it ideal for handling complex business logic and high-performance environments like MaaS. The Spring framework was chosen due to its flexibility, lightweight nature, and built-in support for creating secure, scalable REST APIs [52], which are essential for interfacing with both client applications and the Hyperledger Fabric blockchain. In Hyperledger Fabric, direct access to peers from the client application is restricted. The backend also utilizes a messaging queue and a payment gateway to support its operations.

The platform’s backend exposes a REST API based on JSON, allowing communication with client applications.

The Java Fabric SDK v2.1 [53] is used to link the API with the blockchain network.

Basic operations, such as ride payments or balance inquiries, are directly managed by the API through the Fabric SDK. However, more complex tasks, like generating statistics, are offloaded using a messaging system (RabbitMQ). When such a request is made, the API logs it into the messaging service, and a worker processes the message once available. The messaging queue distributes tasks among multiple workers, enabling load balancing and ensuring scalable, efficient resource use while avoiding bottlenecks [54].

3.2.4. Payment Service

The Payment Service is a vital component of the system architecture, allowing for easy connection with external payment providers. It connects the MaaS platform with financial institutions, allowing users to make safe fund deposits, payments, and withdrawals. This service enables real-time transaction processing, guaranteeing that all payments are confirmed and authorized using known financial procedures such as PCI-DSS (Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard).

Furthermore, to ensure secure and smooth transactions, the gateway must encrypt sensitive payment data during transfer, minimizing the risk of fraud and unauthorized access. It also manages tokenization processes to replace sensitive card information with a unique identifier, ensuring user privacy and security standard compliance.

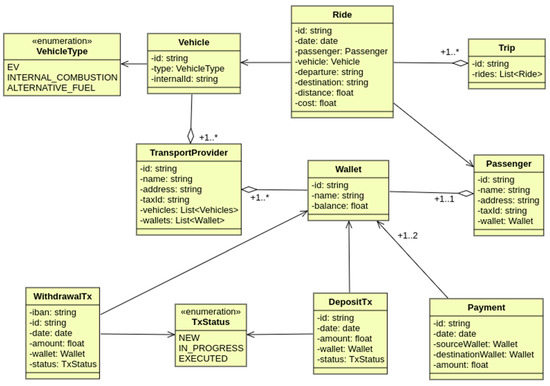

3.3. Data Model

Figure 3 provides a comprehensive illustration of the data model stored within the blockchain. This figure delves into the blockchain’s data architecture, presenting the main asset classes and their relationships.

Figure 3.

The data model of the platform.

TransportProvider and Passenger store the user details for transport companies and transportation users, respectively.

The Vehicle asset is responsible for storing data related to the company’s fleet. It includes three VehicleTypes: electric vehicles, internal combustion, and alternative fuel.

The Wallet asset is linked to an owner, which can be either a company or an individual user, and manages its balance. When a deposit or a withdrawal takes place, the balance is updated, and a corresponding transaction record is created. Similarly, when a payment is made, the balances of both involved wallets are adjusted, and the transaction is documented.

The Ride asset records comprehensive details for each transportation instance, including the user utilizing the service, the vehicle employed, the date of the ride, the starting and ending locations, the cost incurred, and the distance traveled. Additionally, multiple connected Ride records are grouped together to create a Trip, which represents a series of linked rides within a single journey.

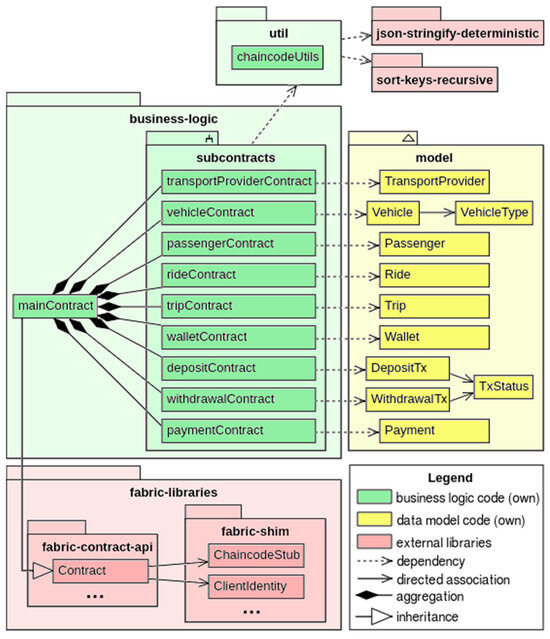

3.4. Chaincode Implementation

The Hyperledger Fabric chaincode is equivalent to smart contracts found in other blockchain platforms. It establishes the rules and logic that govern transactions within the network. Chaincode, which can be written in Go, Node.js, or Java, is a program that follows a predefined interface (API) provided by the fabric-contract-api library. Another key library for developing and deploying chaincode is fabric-shim, which provides the necessary implementation to enable communication between smart contracts created with fabric-contract-api and Hyperledger Fabric peers.

The business logic within the chaincode is implemented across multiple modules. Each module primarily implements the available operations for one of the assets defined in the data model (e.g., vehicleContract.js for Vehicle, rideContract.js for Ride, walletContract.js for Wallet, etc.). These are referred to as domain logic modules.

The chaincodeUtils.js module is utilized by the domain logic modules as it offers a generic implementation for operations such as create, read, update, delete, getAll, saveAll, exists, and getBySelector, which is used to execute complex queries.

The complete business logic is made accessible externally through the facade module chainCode.js. This module consolidates all the public operations implemented by the domain logic modules and it is implemented as a class that inherits from the Contract class provided by the fabric-contract-api library.

Figure 4 presents the chaincode structure for the proposed solution, which is implemented in Node.js.

Figure 4.

The chaincode structure diagram.

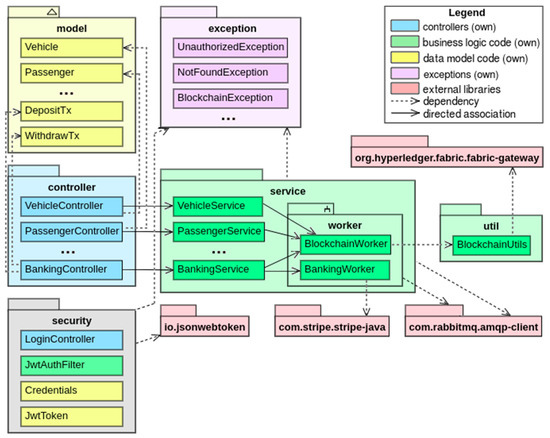

3.5. Backend Implementation

As mentioned earlier, the platform’s backend is implemented in Java v21 with Spring Boot v3.1.4. Figure 5 illustrates the modular architecture designed for the backend of the proposed Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) platform. The diagram categorizes components into distinct functional layers, highlighting their roles, dependencies, and interactions. This design follows established principles for developing software that is scalable, maintainable, and secure. Assets stored on the blockchain (as detailed in Figure 3) are processed by specialized components within each functional layer. Notably, Figure 5 displays only a subset of these components related to asset handling.

Figure 5.

The backend code structure diagram.

The data model layer encapsulates the core data entities of the platform, representing the system’s domain objects. These classes form the foundation for storing and manipulating data throughout the platform.

The controllers act as the entry point for HTTP requests, exposing RESTful API endpoints for external clients. Each controller delegates requests to the corresponding service layer for processing, ensuring a clean separation of concerns.

The service layer encapsulates the core business logic of the application, providing reusable and modular functionality. Services delegate asynchronous, computationally intensive, or time-consuming tasks to worker modules (BlockchainWorker and BankingWorker), which handle operations like blockchain integration and payment processing. These modules enhance modularity and scalability by offloading complex operations from the service layer. The decoupling of the services from the task-executing workers is conducted via RabbitMQ.

Security components manage authentication and authorization mechanisms for the platform. This layer ensures secure access to the platform while maintaining user data integrity.

Custom exception classes are defined to handle system-specific errors gracefully. These exceptions enhance error traceability and robustness by providing detailed feedback during runtime.

The platform integrates with external libraries to extend its functionality and simplify development. The BlockchainUtils module interfaces with the Hyperledger Fabric Gateway SDK (org.hyperledger.fabric.fabric-gateway) for secure and efficient communication with the blockchain network. While the library com.rabbitmq.amqp-client manages message queuing for asynchronous processing, com.stripe.stripe-java facilitates secure payment transactions. Finally, io.jsonwebtoken is used for managing JSON Web Tokens (JWTs) for user authentication and session management.

4. Tests and Results

4.1. Test Environment

The backend and blockchain network were installed on an Amazon EC2 t3.large instance with the following specifications:

- Instance Type: t3.large

- Processor: Intel® Xeon® Platinum 8175 M CPU @ 2.50 GHz with 2 virtual CPUs (1 physical core with Hyper-Threading)

- Architecture: 64-bit (x86-64)

- Memory: 8 GB RAM

- Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS

- Kernel Version: Linux 6.8.0-1018-aws

- Storage: 20 GiB NVMe SSD (Amazon EBS)

- Virtualization Platform: Amazon EC2

This setup replicates a practical cloud-based deployment environment, offering a reliable framework for testing the integration of blockchain technology into MaaS platforms. The choice of the t3.large instance reflects a deliberate effort to find a balance between performance and affordability, ensuring sufficient computational capacity while minimizing unnecessary costs.

The load and functional tests were executed remotely using a PC configured with the following specifications:

- Processor: Intel® Core™ i7-8565U CPU @ 1.80 GHz with 8 logical cores

- Architecture: 64-bit (x86-64)

- Memory: 16 GB RAM

- Operating System: Ubuntu 24.04.1 LTS

- Storage: 512 GB SSD

- Kernel Version: Linux 6.8.0-47-generic

Load and functional tests from a remote PC were conducted to simulate the experience of end-users accessing the platform via the Internet.

4.2. Functional Testing

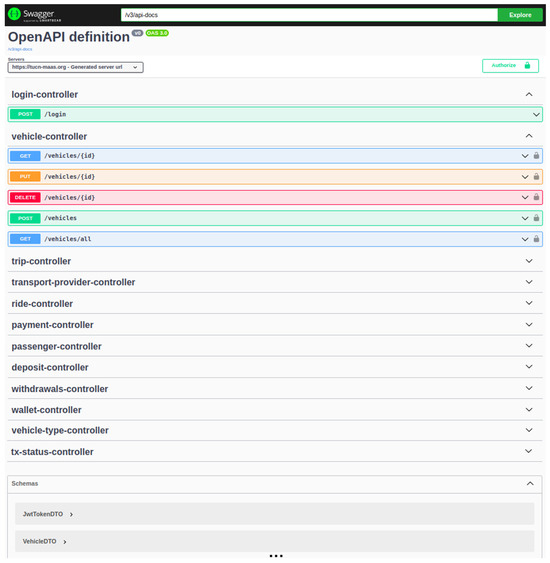

To verify the proper functionality of the platform’s REST API, backend services, and blockchain integration, thorough functional testing was conducted using OpenAPI v3.0.1 (formerly known as Swagger). This systematic approach ensured that each component operated as intended and that their interactions were seamless and error-free.

OpenAPI provides standard specifications for describing RESTful APIs in a machine-readable format, enabling the automatic generation of interactive documentation and client libraries. OpenAPI was integrated with the Java/Spring system’s backend by using the Springdoc OpenAPI library. This setup facilitates the automatic creation of comprehensive API documentation, accessible through SwaggerUI from browsers, which supports straightforward testing and the validation of backend services and blockchain interactions.

Tests were conducted on all critical endpoints, including the following:

- Authentication Endpoints: User registration, login, and token-based authentication mechanisms were verified.

- Transaction Endpoints: The creation, updating, and deletion of transactions were tested to ensure proper processing and accurate recording on the blockchain.

- Data Retrieval Endpoints: Functionality was confirmed for retrieving essential user data, such as ride histories and account balances.

Each test case involved sending requests with both valid and invalid data to evaluate the API’s response handling, error messaging, and data validation processes.

The functional testing yielded positive results:

- Correct Functionality: All endpoints performed as expected, with backend services accurately processing requests.

- Blockchain Interaction: Transactions were successfully recorded on the blockchain, maintaining data integrity.

- Error Handling: The API returned appropriate error messages and status codes in response to invalid inputs.

- Performance: Response times were satisfactory, demonstrating efficient backend processing and minimal overhead from blockchain operations.

Figure 6 shows a screenshot of the OpenAPI interface used during testing. It illustrates the available API endpoints grouped by controllers and the expanded vehicle controller with its available operations.

Figure 6.

OpenAPI interface displaying controllers and endpoints.

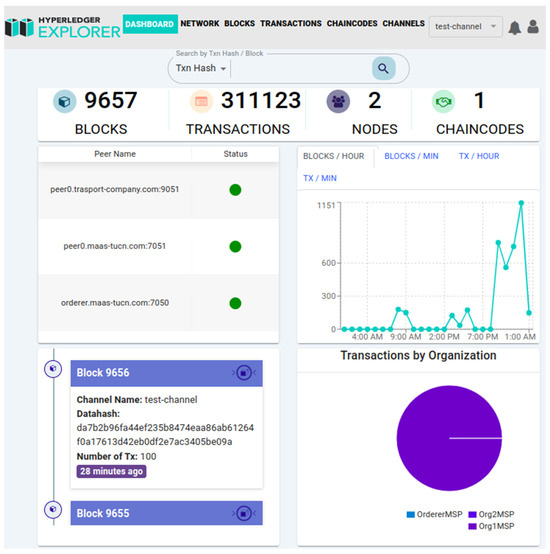

Hyperledger Explorer was employed to enable the verification and monitoring of blockchain transactions within the platform. This tool provides a user-friendly dashboard (see Figure 7) for viewing transaction details, block information, and the overall state of the blockchain network. Through the explorer, it was possible to confirm that transactions initiated by backend services were recorded on the blockchain, ensuring data integrity and transparency. Features such as real-time updates, transaction histories, and block summaries were used to validate the correct functioning of the blockchain integration within the system.

Figure 7.

Hyperledger Explorer dashboard.

Additionally, the dashboard shows transaction details such as timestamps, endorsements, and read/write sets. The timestamps and endorsements verify when a transaction is executed and which peers validate it, underscoring the decentralized consensus process. The read/write sets reveal which assets or records are updated in the ledger, providing a transparent audit trail of how data evolve over time.

Hyperledger Explorer also highlights network channel information, which is especially valuable in a permissioned context. Channels partition the network so that certain transaction data remain accessible only to authorized organizations, meeting privacy requirements in use cases such as MaaS. By monitoring channel-specific transactions and participants, stakeholders can confirm the correct partitioning of data and verify that confidentiality measures are functioning as intended.

Overall, these dashboard components reinforced the reliability of the proposed system by visually confirming that each transaction was securely recorded, properly endorsed, and immutably stored. Such transparency assists both providers and end users in tracking and auditing the lifecycle of on-chain data, strengthening confidence in the MaaS platform’s performance and trustworthiness.

4.3. Load Testing

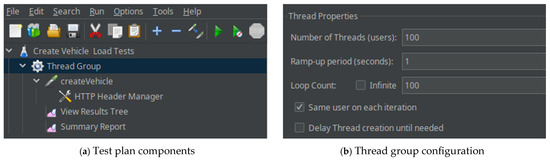

To understand how response times are influenced by the number of simultaneous requests and the volume of blockchain records, a comprehensive series of load tests were performed. It is important to note that during these evaluations, the entire system—including both the backend and the blockchain network—was hosted on a single machine. Consequently, the performance measurements obtained are relative and may vary once deployed in a production environment. These load tests were primarily aimed at assessing how response times fluctuate based on the intensity of concurrent requests and the size of the blockchain data. Apache JMeter 5.6.3 was used for implementing the load tests. Figure 8 shows the basic structure of all the employed test plans. A test plan is composed of a thread group, a http request, and two result views.

Figure 8.

Apache JMeter test plan example.

The tests assess two standard operations—getting the total monthly spending and retrieving the wallet by ID—that users can access through the client applications. The state database of Fabric is CouchDB, and an index was added for the second operation on its search criteria: [sourceWalletId, date]. Integrating the CouchDB index into the chaincode requires placing a JSON file in the chaincode’s main directory at the path: META-INF/statedb/couchdb/indexes. The content of the index is shown below:

- {

- “index”: {

- “fields”: [

- “sourceWalletId”,

- “date”

- ]

- },

- “ddoc”: “indexSourceWalletIdDate”,

- “name”: “indexSWalletDate”,

- “type”: “json”

- }

Following the addition of 10,000, 100,000, and 1,000,000 fictitious data records to the blockchain, respectively, the tests demonstrated that, provided the records are indexed by the search criteria, the response times are independent of the volume of data stored. The average blockchain response time for each number of concurrent requests is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Load test results.

At around 400 parallel requests, the response error rate (timeouts) averaged around 10% for both operations. This request limit can serve as a reference point for adjusting the number of workers in the messaging queue.

Table 2 shows the average response time (for 100 requests with one thread) for the primary operations supported by each asset in the data model, including Vehicle, Passenger, Ride, and others.

Table 2.

The temporal performances of main operations.

As shown in the table above, the performance of basic CRUD operations is not influenced by the number of existing blockchain records. Efficient retrieval by id is ensured through implicit indexing of assets. Create, update, and delete operations consistently take approximately 2 s each because they involve blockchain state modifications that require communication and validation processes. This consistent duration is primarily due to the BatchTimeout parameter, which is set by default to 2 s. The BatchTimeout defines the amount of time the blockchain network waits before creating a new block. Any new validated transactions are batched and added to a block every two seconds. In contrast, retrieving an asset by a different attribute (e.g., name) encounters substantial delays, which are proportional to the size of the dataset. This issue can be mitigated by indexing assets by name, improving retrieval efficiency.

4.4. Blockchain Network Tuning

Optimizing the performance of blockchain networks is critical for enterprise-level applications. This chapter delves into adjusting key Hyperledger Fabric parameters—MaxMessageCount and BatchTimeout—to enhance efficiency under high-traffic conditions.

MaxMessageCount (batch size) sets the maximum number of transactions in a block, while BatchTimeout determines the maximum delay before block creation if the transaction limit is not reached. Tuning these parameters directly influences transaction throughput and latency.

Performance evaluation involved the use of Apache JMeter with a fixed test plan configuration: 100 threads, a 1 s ramp-up time, and 100 iterations per thread. The operation used in these tests was create vehicle, but it can be any other type of transaction. The goal was to identify optimal configurations that balance processing speed and resource utilization.

The tests were conducted remotely, inherently incorporating network latency into the performance measurements. To ensure the validity and consistency of the results, the experiments were repeated at different times throughout the day. The outcomes remained consistently similar across these repetitions, confirming the reliability and relevance of the findings.

Table 3 presents the performance results from load tests conducted on the Hyperledger Fabric network. These tests varied the MaxMessageCount settings while keeping the BatchTimeout fixed at the default value of 2 s.

Table 3.

Performance metrics for varying MaxMessageCount.

The table demonstrates that increasing the batch size from 10 to 100 transactions per block reduces average latency significantly, from 4.6 to 2.9 s, indicating better performance. Beyond a batch size of 100, however, performance begins to decline. For instance, at batch sizes of 200 and 500, the average latency rises to 3.5 and 4 s, respectively. This suggests that for the current blockchain configuration and a constant rate of 100 requests per second, there is an optimal batch size of around 100. Beyond this value, the benefits of batching are outweighed by the increased waiting time.

Given the fixed transaction rate of 100 requests per second, selecting batch sizes of 75, 100, and 125 messages is a logical approach for tuning the BatchTimeout parameter. These batch sizes correspond to scenarios where the batch size is slightly below, equal to, and slightly above the transaction arrival rate. This selection allows for a comprehensive evaluation of how different batch sizes, relative to the transaction rate, impact network performance. Table 4 presents the performance metrics observed for various combinations of MaxMessageCount and BatchTimeout values.

Table 4.

Performance metrics for varying MaxMessageCount and BatchTimeout values.

The test results reveal that adjusting MaxMessageCount and BatchTimeout significantly impacts network latency. The lowest average latency of 2.9 s occurs with a MaxMessageCount of 100 and a BatchTimeout of 2 s, reflecting an ideal balance for a fixed transaction rate of 100 requests per second. When MaxMessageCount is reduced to 75, increasing BatchTimeout from 0.5 to 2 s further lowers latency, showing the benefit of the extended accumulation time in smaller batches. However, raising MaxMessageCount to 125 and setting BatchTimeout beyond 2 s increases latency, demonstrating how larger batches and excessive wait times can hurt performance. These results underscore the importance of aligning MaxMessageCount with transaction rates and carefully selecting BatchTimeout to optimize network efficiency.

4.5. Comparative Analysis with Other Emerging Technologies

When compared to other emerging technologies that aim to improve urban mobility (e.g., AI-driven systems, IoT sensor networks, or conventional cloud-based platforms) blockchain stands out primarily for its ability to establish decentralized trust among multiple stakeholders. AI-based systems are excellent for predictive analytics, route optimization, and dynamic scheduling. Unfortunately, they usually rely on centralized data storage, raising privacy concerns [55,56]. IoT sensor networks collect real-time vehicle and infrastructure data, which may aid in mobility planning; however, analyzing and safely transferring massive data streams across several entities may need strict interoperability standards [57,58]. Cloud-centric platforms have developed tool sets that allow for easy scaling, but they still concentrate data, potentially leaving systems subject to single points of failure or vendor lock-in [59]. By contrast, a blockchain-based MaaS platform mitigates these issues through distributed, tamper-resistant ledgers, thus reducing the risk of fraud and improving transparent collaboration across transport providers and users. Yet, challenges remain in achieving the high throughput or data storage capacities that purely centralized solutions can offer, making off-chain or hybrid approaches necessary in many practical scenarios.

Table 5 presents a summary comparison of blockchain to other upcoming technologies typically recommended for urban mobility. While blockchain has major benefits in terms of trust and transparency, it is not designed to replace these other technologies, but it can be a part of a broader ecosystem: AI can power predictive analytics, while blockchain ensures data integrity across diverse stakeholders; IoT sensors deliver timely mobility updates, while blockchain secures and validates this information in a shared ledger; and cloud-based solutions handle computationally intensive tasks, while the blockchain records transactions, payments, and tickets in a tamper-resistant manner. By combining strengths from multiple technologies, urban mobility systems can achieve a balance between efficiency, security, and resilience for both passenger and freight transport services.

Table 5.

Pros and cons of emerging technologies for urban mobility.

5. Conclusions

This study investigates the integration of blockchain technology into smart mobility systems, specifically focusing on Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS). It addresses the effectiveness of blockchain in improving the efficiency, safety, and environmental performance of urban transport systems. Our results suggest that blockchain, as a decentralized, transparent, and secure solution, can resolve trust and integration issues between different transport technologies and stakeholders.

The Hyperledger Fabric-based design has proven to be highly effective at managing high request volumes, which makes it a viable option for networked transport systems. The study also highlights how blockchain might improve safety and transparency by streamlining ticketing and payment procedures. Additionally, we investigated the main technological features of a blockchain-based MaaS platform, paying particular attention to its data types and system architecture.

The single-machine setup used for initial pilot testing was cost-effective but revealed scalability and resilience issues under load, with performance degrading at 400 concurrent requests. These limitations highlighted the need for a cloud-based, distributed architecture to support real-world use. In a second cloud-based test environment, tuning Hyperledger Fabric with a MaxMessageCount of 100 and a BatchTimeout of 2 s proved optimal for minimizing latency and maximizing throughput at 100 transactions per second. This configuration ensures efficient processing while maintaining low latency, essential for scalable blockchain-based MaaS platforms. Transitioning to this architecture enables dynamic scaling for larger user volumes, with features like load balancing and caching improving peak-time responsiveness. Strategies such as pruning and sharding will further ensure long-term efficiency, making the system viable for large-scale urban deployments.

To verify the scalability of these systems in distributed cloud environments, future research should give priority to pilot projects and field experiments. Additionally, it is necessary to investigate how blockchain technology might help integrate freight logistics into MaaS, guaranteeing safe and open coordination between passenger and freight services. With the further expansion of these systems, it will also be crucial to optimize blockchain transaction rates and minimize latency in real-time urban transit applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.M. and M.H.; methodology, V.M. and A.R.; software, R.M. and A.R.; testing, I.C. and R.M.; validation, V.M. and M.H.; formal analysis, M.H. and A.R.; investigation, V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.M.; writing—review and editing, I.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was conducted as part of the DELPHI project, which is funded by the European Union, under grant agreement No. 101104263.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The views and opinions expressed are only those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Climate, Infrastructure, and Environment Executive Agency (CINEA). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them. The authors acknowledge the use of AI tools, for assisting in editing and refining the manuscript. All intellectual contributions, including the design, content, and conclusions of the paper, are solely those of the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Orecchini, F.; Santiangeli, A.; Zuccari, F.; Pieroni, A.; Suppa, T. Blockchain Technology in Smart City: A New Opportunity for Smart Environment and Smart Mobility. In Intelligent Computing & Optimization, Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Vasant, P., Zelinka, I., Weber, G.-W., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- DELPHI Homepage. Available online: https://delphi-project.eu/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Nakamoto, S. Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System. Available online: https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, S.; Dai, H.N.; Chen, X.; Wang, H. Blockchain challenges and opportunities: A survey. Int. J. Web Grid Serv. 2018, 14, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Wang, F.Y. Blockchain and cryptocurrencies: Model techniques and applications. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 48, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschorsch, F.; Scheuermann, B. Bitcoin and beyond: A technical survey on decentralized digital currencies. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tuts. 2016, 18, 2084–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Pautasso, C.; Zhu, L.; Gramoli, V.; Ponomarev, A.; Tran, A.B.; Chen, S. The blockchain as a software connector. In Proceedings of the 2016 13th Working IEEE/IFIP Conference on Software Architecture (WICSA), Venice, Italy, 5–8 April 2016; pp. 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Saputri, F.A. Regulating the Use of Smart Contract in Indonesia. JHK J. Huk. Dan Keadilan 2024, 1, 42–50. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.; Panayi, E.; Chapelle, A. Trends in cryptocurrencies and blockchain technologies: A monetary theory and regulation perspective. J. Financ. Perspect. 2015, 3, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Manski, S. Building the blockchain world: Technological commonwealth or just more of the same? Strateg. Chang. 2017, 26, 511–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christidis, K.; Devetsikiotis, M. Blockchains and Smart Contracts for the Internet of Things. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 2292–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monrat, A.A.; Schelén, O.; Andersson, K. A Survey of Blockchain from the Perspectives of Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 117134–117151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casino, F.; Dasaklis, T.K.; Patsakis, C. A systematic literature review of blockchain-based applications: Current status classification and open issues. Telemat. Inform. 2019, 36, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bothos, E.; Magoutas, B.; Arnaoutaki, K.; Mentzas, G. Leveraging Blockchain for Open Mobility-as-a-Service Ecosystems. In Proceedings of the IEEE/WIC/ACM International Conference on Web Intelligence—Companion Volume, ACM, Thessaloniki Greece, 14–17 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen TPartala, J.; Pirttikangas, S. Blockchain-Based Mobility-as-a-Service. In Proceedings of the 2019 28th International Conference on Computer Communication and Networks (ICCCN), Valencia, Spain, 29 July–1 August 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.; Nguyen, H.; Partala, J.; Pirttikangas, S. TrustedMaaS: Transforming trust and transparency Mobility-as-a-Service with blockchain. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2023, 149, 606–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, D.; Farooq, B. A multi-layered blockchain framework for smart mobility data-markets. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 111, 588–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indy Homepage. Available online: https://www.hyperledger.org/projects/hyperledger-indy (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Enescu, F.M.; Birleanu, F.G.; Raboaca, M.S.; Bizon, N.; Thounthong, P. A Review of the Public Transport Services Based on the Blockchain Technology. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinaya Sree, P.; Sravan Kumar, K.; Yashwanth Reddy, M.; Rakshith Reddy, A. Ticketing System Using Blockchain Technology. Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2024, 13, 5315–5321. [Google Scholar]

- Terekhov, V. How to Implement Blockchain for Secure Transportation Transactions. 2024. Available online: https://attractgroup.com/blog/how-to-implement-blockchain-for-secure-transportation-transactions (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Jiang, S.; Cao, J.; Wu, H.; Chen, K.; Liu, X. Privacy-preserving and efficient data sharing for blockchain-based intelligent transportation systems. Inf. Sci. 2023, 635, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockburger, L.; Kokosioulis, G.; Mukkamala, A.; Mukkamala, R.R.; Avital, M. Blockchain-enabled decentralized identity management: The case of self-sovereign identity in public transportation. Blockchain Res. Appl. 2021, 2, 100014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roads and Transport Authority (RTA). Al Masar Magazine. 2020. Issue No. 142. Available online: https://www.rta.ae/links/magazine/masar/Al_Masar_142_Eng.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Valavan, A. Blockchain-Powered Transit: Transforming Public Mobility across Metro, MRTS, Railways and Buses. Metro Rail Today. 2024. Available online: https://metrorailtoday.com/article/blockchain-powered-transit-transforming-public-mobility-across-metro-mrts-railways-and-buses (accessed on 2 January 2024).

- Semenzin, S.; Rozas, D.; Hassan, S. Blockchain-based application at a governmental level: Disruption or illusion? Case Est. Policy Soc. 2022, 41, 386–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denver’s RTD. Transit Partner to Simplify Trip Planning, Fare Payment, Metro Magazine. 2024. Available online: https://www.metro-magazine.com/10219415/denvers-rtd-transit-partner-to-simplify-trip-planning-fare-payment (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Kim, S.; Zhang, A.; Liao, R.; Zheng, W.; Hu, Z.; Sun, Z. Sampling Blockchain-enabled Smart City Applications Among South Korea, the United States and China. J. Smart Cities Soc. 2022, 1, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y. Toward Sustainable Governance: Strategic Analysis of the Smart City Seoul Portal in Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Tamakloe, R.; Lee, S.; Park, D. Exploring the Topological Characteristics of Complex Public Transportation Networks: Focus on Variations in Both Single and Integrated Systems in the Seoul Metropolitan Area. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Ruan, W.; Jiang, H.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, L. A Survey of Blockchain Technology Applied to Smart Cities: Research Issues and Challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2794–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuš-Babič, N.; Guerra De Oliveira, S.F.; Tibaut, A. Interoperability of Infrastructure and Transportation Information Models: A Public Transport Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Böhme, R.; Christin, N.; Edelman, B.; Moore, T. Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance. J. Econ. Perspect. 2015, 29, 213–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhyay, N. Demystifying blockchain: A critical analysis of challenges, applications and opportunities. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 54, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhdoom, I.; Abolhasan, M.; Abbas, H.; Ni, W. Blockchain’s adoption in IoT: The challenges, and a way forward. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2019, 125, 251–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmad, M.; Alfouderi, A.D.E.L.; Alonaizi, A.H.M.A.D.; Aldhamen, M. Comparison Study of the Top 5 Leading Cryptocurrencies based on General Consensus Protocol: Bitcoin, Ethereum, Tether, XRP and Bitcoin Cash. WSEAS Trans. Comput. Res. 2023, 11, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonopoulos, A.M. Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Cryptocurrencies; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Hyperledger Fabric Docs—Introduction. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/whatis.html (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Buterin, V. Ethereum Whitepaper: A Next-Generation Smart Contract and Decentralized Application Platform. Ethereum Foundation. Available online: https://ethereum.org/en/whitepaper (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Enterprise Ethereum Alliance, Enterprise Ethereum Client Specification V7. Available online: https://entethalliance.github.io/client-spec/spec.html (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Ethereum Foundation, Solidity Documentation. Available online: https://docs.soliditylang.org/en/latest (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- R3, Corda: A Distributed Ledger R3 Whitepaper. Available online: https://www.r3.com/corda-platform (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Pervez, H.; Muneeb, M.; Irfan, M.U.; Haq, I.U. A Comparative Analysis of DAG-Based Blockchain Architectures. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Open-Source Systems and Technologies (ICOSST), Lahore, Pakistan, 19–21 December 2018; pp. 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbar, R.; Dhib, E.; Said, A.B.; Krichen, M.; Fetais, N.; Zaidan, E.; Barkaoui, K. Blockchain Technology for Intelligent Transportation Systems: A Systematic Literature Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 20995–21031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, P.; Nathan, S.; Viswanathan, B. Performance Benchmarking and Optimizing Hyperledger Fabric Blockchain Platform. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 26th International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis, and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 25–28 September 2018; pp. 264–276. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.; Kong, X.; Lan, Q.; Zhou, Z. The privacy protection mechanism of Hyperledger Fabric and its application in supply chain finance. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyperledger Fabric Docs—Using CouchDB. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/latest/couchdb_tutorial.html (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Hyperledger Fabric Docs—Ledger. Available online: https://hyperledger-fabric.readthedocs.io/en/release-2.2/ledger/ledger.html (accessed on 6 November 2024).

- Mangrulkar, R.S.; Chavan, P.V. Hyperledger. In Blockchain Essentials; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 167–201. [Google Scholar]

- Blockchain Explorer Repository. Available online: https://github.com/hyperledger-labs/blockchain-explorer (accessed on 7 November 2024).

- Blinowski, G.; Ojdowska, A.; Przybyłek, A. Monolithic vs. Microservice Architecture: A Performance and Scalability Evaluation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 20357–20374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, C. Spring in Action, 6th ed.; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2022; ISBN 978-1617297571. [Google Scholar]

- Hyperledger Fabric Gateway SDK for Java Homepage. Available online: https://hyperledger.github.io/fabric-gateway-java/ (accessed on 22 February 2024).

- Pathak, A.; Kalaiarasan, C. RabbitMQ Queuing Mechanism of Publish Subscribe model for better Throughput and Response. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies (ICECCT), Erode, India, 15–17 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov, I.P. Optimizing Public Transport Services using AI to Reduce Congestion in Metropolitan Area. Int. J. Intell. Autom. Comput. 2022, 5, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Artificial Intelligence Applied on Traffic Planning and Management for Rail Transport: A Review and Perspective. Discret. Dyn. Nat. Soc. 2023, 2023, 1832501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanella, A.; Bui, N.; Castellani, A.; Vangelista, L.; Zorzi, M. Internet of Things for Smart Cities. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Song, X.; Zhang, H. Chapter 8—MaaS and IoT: Concepts, methodologies, and applications. In Big Data and Mobility as a Service; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- Faieq, S.; Saidi, R.; Elghazi, H.; Rahmani, M.D. C2IoT: A framework for Cloud-based Context-aware Internet of Things services for smart cities. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2017, 110, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).