Abstract

An electrocardiogram (ECG) is a vital diagnostic tool that provides crucial insights into the heart rate, cardiac positioning, origin of electrical potentials, propagation of depolarization waves, and the identification of rhythm and conduction irregularities. Analysis of ECG is essential, especially during pregnancy, where monitoring fetal health is critical. Fetal electrocardiography (fECG) has emerged as a significant modality for evaluating the developmental status and well-being of the fetal heart throughout gestation, facilitating early detection of congenital heart diseases (CHDs) and other cardiac abnormalities. Typically, fECG signals are acquired non-invasively through electrodes placed on the maternal abdomen, which reduces risk and enhances user convenience. However, these signals are often contaminated via various sources, including maternal electrocardiogram (mECG), electromagnetic interference from power lines, baseline drift, motion artifacts, uterine contractions, and high-frequency noise. Such disturbances impair signal fidelity and threaten diagnostic accuracy. This scoping review adhering to PRISMA-ScR guidelines aims to highlight the methods for signal acquisition, existing databases for validation, and a range of algorithms proposed by researchers for improving the quality of fECG. A comprehensive examination of 157,000 uniquely identified publications from Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science have resulted in the selection of 6210 records through a systematic screening of titles, abstracts, and keywords. Subsequently, 141 full-text articles were considered eligible for inclusion in this study (from 1950 to 2026). By critically evaluating established techniques in the current literature, a strategy is proposed for analyzing fECG and calculating heart rate variability (HRV) for identifying fetal heart-related abnormalities. Advances in these methodologies could significantly aid in the diagnosis of fetal heart diseases, assisting timely clinical interventions and prevention.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) continue to pose the greatest global health challenge, resulting in roughly 17.8 million deaths each year [1]. This affects individuals across all demographics, including fetuses during gestation. Improper monitoring of fetal cardiac activity can lead to unnecessary cesarean sections or surgical vaginal deliveries. According to research by the American Heart Association (AHA), 2.65 million babies are stillborn annually, and approximately 8 out of every 1000 live births involve a heart defect. In addition, around 40,000 newborns are diagnosed with congenital cardiac diseases every year [2]. Furthermore, fetal hypoxia constitutes a significant concern, often leading to hypoxic–ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) [3,4]. To ensure proper health and development, assessing the fetal heart’s condition at various stages during pregnancy is vital for evaluating cardiac functionality and maturity [5].

The fetal heart rate (FHR) varies throughout pregnancy, starting at 110 bpm during the first trimester (5–6 weeks), increasing to 170 bpm at 9–10 weeks, then decreasing to 150 bpm from 14 weeks onward, 140 bpm after 20 weeks, and finally reaching 130 bpm in the last trimester [6]. In clinical settings, variations in the baseline, deceleration, late deceleration, etc., are used to identify fetal abnormalities [7,8]. For the precise and timely evaluation of fetal cardiac health, a variety of diagnostic techniques have been developed for effective identification and for monitoring cardiac anomalies. Among the available diagnostic modalities for detecting these anomalies are phonocardiography (PCG), cardiotocography (CTG), coronary angiography (CAG), and fetal electrocardiogram (fECG) [9]. PCG captures the acoustic signals of the heart, allowing for the analysis of systolic and diastolic activities; however, it suffers from significant inaccuracies [10]. In contrast, CTG utilizes Doppler-based ultrasound technology, which is extensively employed in clinical settings to monitor instantaneous FHR in conjunction with uterine contractions (UCs) [11,12]. Presently, a non-invasive and pain-free CTG machine is the most prevalent instrument for labor monitoring. This device provides a graphical representation of the FHR and UCs on thermal paper. Despite its widespread use, conventional CTG presents several limitations as it requires frequent repositioning of the probe to maintain accurate FHR readings. The encircling belt can cause discomfort for patients, and the device restricts patient mobility, necessitating confinement to a bed. The limitation in movement may increase the likelihood of unnecessary cesarean sections or deliveries involving vacuum devices or forceps [13]. Moreover, the device requires the expertise of skilled nurses to locate the fetal heart, which can change position as the fetus moves. In spite of innovations like mobile sensor integration for remote monitoring, CTG is still held back by high costs, bulkiness, and lesser accuracy, which does not seem to effectively lower rates of fetal stillbirth and hypoxia.

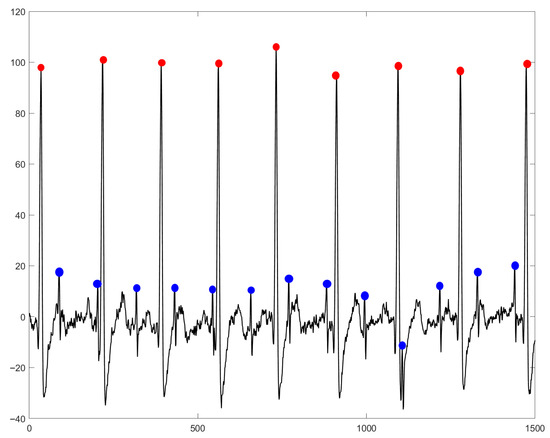

Taking into consideration the aforementioned limitations, fECG is an effective diagnostic tool for the timely detection of congenital heart disease (CHD), hypoxia, cardiac morphology and rhythm. The fECG can be obtained through invasive scalp electrodes (ISEs) [14] or non-invasive electrodes placed on the maternal abdomen. ISEs provide greater accuracy with heightened risks for both the mother and the baby compared to the safer non-invasive methods. Non-invasive approaches capture signals from the maternal abdomen, ideally known as abdominal electrocardiogram (aECG), which includes both maternal electrocardiogram (mECG) and fECG signals. However, both methods face the challenge of low-amplitude signals due to the high resistance of vernix caseosa [15]. Weak fECG signals are easily contaminated by various noises and the dominant mECG, as shown in Figure 1, which calls for the need of advanced techniques to effectively extract the desired signal from unwanted signals (such as mECG, maternal muscle activity, fetal movement etc.).

Figure 1.

Overlapping of mECG on fECG in an aECG signal. The R-peak positions for mECG are indicated by red dots, while fECG R-peaks are marked by blue dots. Sourced from the aECG signal available in the DaISy database [16].

The popular computer-aided automatic diagnosis (CAD) techniques used by researchers to denoise fECG signals are primarily categorized into several groups, such as template methods [17], hybrid approaches [18,19], adaptive filtering (AF) techniques [20,21,22], decomposition methods, blind source separation (BSS) [23,24,25], genetic algorithm (GA) [26], and recently, developed deep learning (DL) approaches [27,28,29,30]. Adaptive algorithms include multi-sensor adaptive noise cancelers (MSANC) [31], adaptive Volterra filters [32], adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) [33], event synchronous cancelers [34], and Type-2 ANFIS [35]. Popular BSS algorithms employed by researchers include independent component analysis (ICA), such as Infomax, Fast-ICA (FICA), space-time FICA, and robust ICA [36,37,38], as well as principal component analysis (PCA) [23,39,40,41]. Other notable methods are joint approximate diagonalization of eigen matrices (JADE), non-negative matrix factorization [42,43], time-scale imaging [44,45], periodic component analysis (CA) [46], tensor decomposition (TD) [47], and short-time Fourier transform (STFT). Moreover, researchers have also implemented projection techniques, such as affine transform [48]. The methods used in the literature have the potential to aid healthcare professionals in the effective diagnosis of fetal heart conditions.

1.1. Methods

A comprehensive review of the methodologies employed for fECG extraction from aECG was undertaken in accordance with PRISMA-ScR guidelines [49] to identify the potential strengths and limitations. This approach helped to develop a methodology with higher performance and lesser computation. The objective was to identify all pertinent research articles related to fECG extraction, utilizing databases, such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science. The initial query was meticulously crafted to capture a wide array of studies within the field, incorporating keywords, such as “fECG”, “fECG signal”, and “fetal ECG extraction”.

- Identification Phase:

The search yielded a total of 157,000 records across all databases (such as Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science). The identified articles were unique and qualified for further evaluation.

- Screening Phase:

The screening phase was carried out manually, without the use of any automated tools, to ensure a thorough examination of each article. A preliminary screening was performed utilizing titles, abstracts, and keywords to assess the relevance of various studies. The inclusion criteria encompassed studies that addressed at least one of the following aspects:

- A focus on the isolation of fECG from aECG signals.

- A report on novel methodologies for the identification of fECG.

- An inclusion of analysis of ECG biomarkers (such as R-R interval and FHR), specifically for analyzing fetal heart growth.

- An implementation of hardware-based techniques for the real-time acquisition and processing of fECG signals.

Additionally, research articles published prior to the year 2000 were systematically excluded from the analysis and articles that merely mentioned the specified keywords without contributing relevant content to the study were also eliminated from consideration. As a result of these criteria, the dataset was refined to include 6210 pertinent records, while a total of 150,790 records were deemed irrelevant and subsequently removed. As the screening was carried out manually by the authors, no computational processing time was recorded.

- Eligibility Phase:

The remaining 6210 records underwent a comprehensive full-text review, during which specific exclusion criteria were applied, including the following:

- Restating previously published data.

- Lack of in-depth analysis or novel insights.

- Insufficient focus on FHR, RR-interval processing, and diagnostic information identification.

As a result, 6069 articles were excluded, leaving 141 records that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

- Inclusion Phase:

The 141 articles that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were meticulously analyzed and incorporated into the final systematic review. This review encapsulated studies that provided significant insights into fECG extraction techniques.

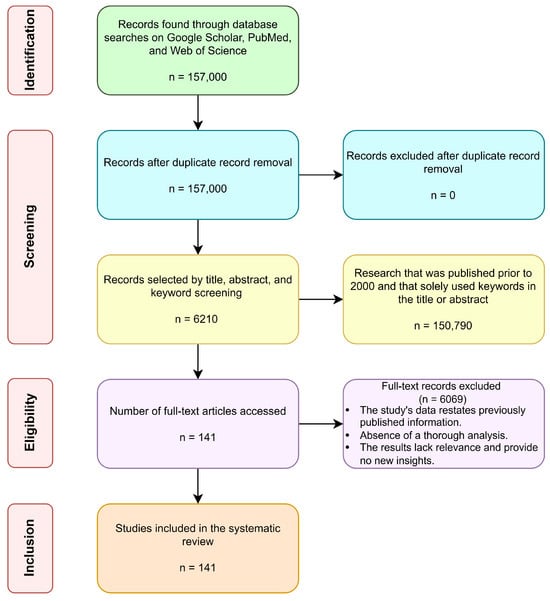

This systematic approach ensured the selection of high-quality, relevant studies, as illustrated in the attached PRISMA flow diagram, shown in Figure 2. This rigorous methodology facilitated a comprehensive synthesis of the existing literature, establishing a solid foundation for future advancements in the field of prenatal and neonatal healthcare.

Figure 2.

The information search conducted in a PRISMA flow diagram. Here, ‘n’ represents the number of searched articles from Google Scholar, PubMed, and Web of Science.

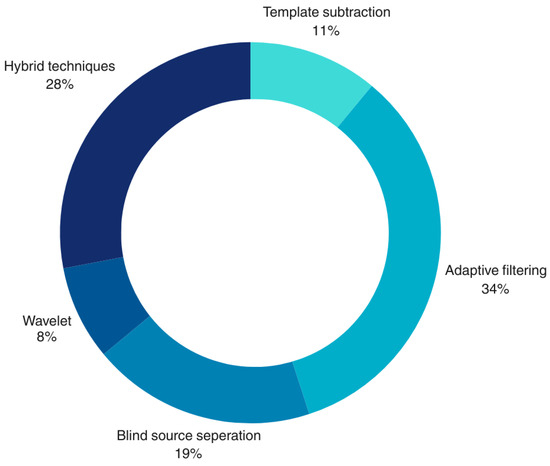

Overall, 11% of articles were based on template subtraction, 34% of articles were derived from AF, 19% of articles utilized BSS, 8% of articles were wavelet-based, and 28% of articles combined both traditional and AI techniques (classifying them as hybrid methods). The effectiveness of the aforementioned methods for fECG extraction from aECG was extensively investigated, and the corresponding strengths and weaknesses were analyzed in order to develop a reliable and computationally efficient algorithm. The pie-chart below (shown in Figure 3) depicts a pictorial representation of the distribution from each technique in terms of percentage.

Figure 3.

The percentage contribution of each technique from the literature search for fECG extraction.

1.2. Novel Contributions

The major contributions of this systematic study are as follows:

- Analysis of the growth of fetal hearts during the gestation period and its correlation with fECG signals.

- Summarization regarding the various defects associated with fetus and their complications during the gestation period.

- Summarization of the methods used for acquiring fECG from an expecting mother along with positioning electrodes.

- Development of the fetal heart and acquisition techniques of fECG signals for predicting fetal diseases.

- Summarization of the publicly available fECG databases for analysis.

- Descriptions of the various performance metrics for evaluating the efficacy of fECG extraction techniques along with their corresponding limitations.

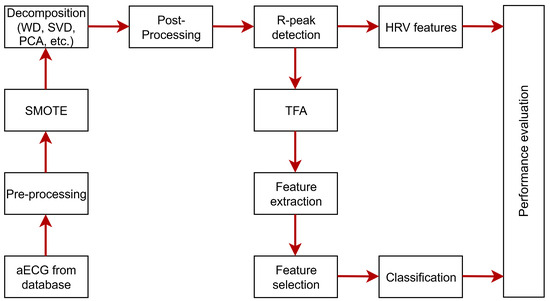

- A proposed technique that is achieved by considering the potential benefits of fECG analysis techniques.

The rest of the manuscript is structured as follows: the significance of fECG signals and the process of acquisition of fECG signals in clinical practice is discussed in Section 2. The details of publicly available databases are described in Section 3, followed by the delineation of quantitative metrics used for performance evaluation in Section 4. The algorithms utilized by researchers in the literature, their advantages, and their limitations are presented in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 and Section 7 include the discussion and conclusion.

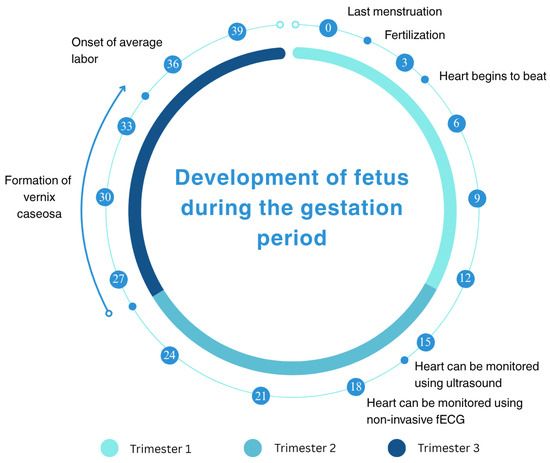

2. Significance of fECG Signal and Method of Acquisition

The healthy development of a fetal heart is essential for a child’s well-being. This process begins around the week of pregnancy and continues until the week of gestation. Figure 4 illustrates the timeline of fetal heart development throughout the three trimesters of pregnancy. The initial heart beat can be detected around the 4th week, with ultrasound monitoring commencing at the 16th week. By the 20th week, non-invasive fetal ECG signals can be used for monitoring. By the 28th week, a protective waxy layer known as vernix caseosa begins to form and gradually breaks down as the pregnancy approaches the 32nd week followed by average labor, which is around the 36th week [50].

Figure 4.

A timeline illustrating the development of a human fetus across the three trimesters of pregnancy, spanning from the last menstruation to 40 weeks of gestation. Key milestones include fertilization at week 0, the onset of heart beats around week 4, the ability to monitor the heart using ultrasound from week 16, and the use of non-invasive fetal electrocardiography (via non-invasive fECG) from week 20. The timeline also marks the vernix caseosa (a protective waxy coating) appearance around week 28 and average labor onset at week 36 [50,51].

Abnormalities during the development of a fetal heart can cause serious cardiac defects, endangering the baby’s life. Heart diseases are primarily influenced by certain medications taken during pregnancy, inadequate nutrition intake by the mother, inconsistent monitoring during pregnancy, lack of adequate health facilities, and associations with genetic and environmental factors [52].

There are various heart diseases that a fetus may develop. The major cardiac anomalies are fetal arrhythmia and CHDs. Fetal arrhythmias are defined as irregular heart rhythms that manifest in utero and significantly impact the electrical activity of the fetal heart [53]. CHDs are structural anomalies of the heart that are present at birth, manifesting a spectrum ranging from mild conditions (that are self-resolving) to severe malformations necessitating surgical or other therapeutic interventions [54]. The management of both fetal arrhythmias and CHDs necessitates meticulous monitoring by specialized healthcare professionals to ensure accurate diagnosis, timely intervention, and comprehensive management, providing potential implications of the health of infants both prenatally and postnatally. Early detection and appropriate therapeutic strategies are paramount in optimizing outcomes and mitigating long-term sequelae associated with these conditions [55].

In light of this, fECG can be utilized for identifying the aforementioned abnormalities by carefully assessing fECG segments (such as QT-intervals, ST-intervals, T/QRS ratio, etc.). The electrical activity of the fetal heart closely resembles an adult’s but differs mechanically. The heart’s electrical signals start at the sinoatrial (SA) node, and it is then transmitted through the atrioventricular (AV) node and the Bundle of His to reach the Purkinje fibers. An ECG displays this activity with waveforms, such as P-wave, QRS complex, ST segment, and T-wave, offering insights into heart functionality disorders. It is to be noted that features of the fECG signal keep changing because of the development of the fetal heart, but the signal gradually stabilizes over the course of pregnancy.

The P-wave signifies atrial depolarization, representing the electrical activity occurring in the atria. In the context of fetal monitoring, the P-wave indicates the electrical activity of the fetal atria, providing valuable information regarding the different phases of fetal heart development throughout a pregnancy. The QRS complex arises from ventricular depolarization and offers crucial insights into fetal ventricular activity, cardiac rhythm, and any other irregularities present. The ST-segment denotes the period of electrical inactivity, which is the interval between ventricular depolarization and repolarization. Following the ST-segment, the T-wave indicates ventricular repolarization, representing the recovery phase. The timing of T-waves in fECG is critical for evaluating cardiac repolarization patterns, particularly through the analysis of ST- and QT-intervals [56].

Recognizing the importance of fECG signals in assessing fetal well-being, it is essential to examine the techniques and challenges associated with obtaining these signals, the various techniques of which are detailed in Section Method of Acquisition of fECG Signal in Clinical Practice.

Method of Acquisition of fECG Signal in Clinical Practice

According to Oostendorp’s hypothesis [57,58], fetal heart signals are transmitted through the mother’s abdomen and maintain uniform conduction until the vernix caseosa forms. This signal strength increases as the vernix dissolves in the amniotic fluid around 37 weeks. Research shows the conduction pathway is through the umbilical cord, and the aECG strength rises after 34 weeks. Proper electrode placement on the mother’s abdomen can enhance fECG acquisition [59,60].

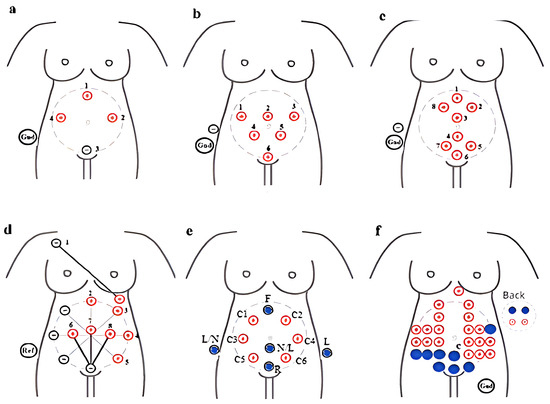

The effective method employs ECG electrodes on the abdomen of pregnant women. The recording quality depends on the arrangement and placement of these electrodes [61]. During the first two trimesters, the fetus moves within the uterus, making its orientation unpredictable; however, the fetal head is downwards (vertex position) 96.8% of the time [62]. Researchers in the biomedical field have proposed various configurations for electrode placement to obtain quality aECG. Some studies cover the entire abdomen to maximize signal strength, while others focus on specific placements [61,63]. A minimum of 4-bipolar electrodes in a circular arrangement, plus one reference electrode near the pubic area, is typically used (as shown in Figure 5a). For an 8-electrode setup, the electrodes are arranged in a triangular (as shown in Figure 5b) and circular (as shown in Figure 5c) setup [64]. In a 10-electrode configuration, 6 electrodes are arranged in a hexagonal pattern centered on the navel (as shown in Figure 5d), while the electrodes in a 32-electrode setup are distributed along the abdomen, sides, and back (as shown in Figure 5f). The MindChild Meridian monitoring system uses 32 electrodes for daily aECG analysis. In general, a few electrodes (8–10) are sufficient to capture essential fetal heart activity. Many studies have used 5-electrode configurations [16].

Figure 5.

Systematic strategy for the configuration and position of electrodes on a mother’s abdomen for capturing aECG recordings: (a) 5 electrodes, (b) 8 electrodes positioned in triangular shape, (c) 8 electrodes placed in a group of four above and below the naval point, (d) 10 electrodes placed in hexagonal shape with the naval as the center with a radius of 10, (e) 14 electrodes positioned on the circumference of the circle with the naval as the center, and (f) 32 electrodes covering the whole abdominal area along the sides and back [65].

Marchon et al. [65] presented three electrode placement configurations using a standard 12-lead setup (limb leads around the fetus for fECG and four precordial leads with V5 and V6 on the mother’s upper arm for mECG). The ECG monitoring system was created by Kallows Engineering in Goa. The authors recorded 18 m of data from a 24-year-old pregnant woman at 34 weeks of gestation over five days. Some researchers have used mixed configurations with 8- (five around the navel and three thoracic), 9- (six around the navel and three vertically placed thoracic), and 14-electrode (twelve horizontally around the navel and two on the mother’s shoulder) setups [66,67,68].

But, the acquired signals via a non-invasive approach are susceptible to mECG signals, power-line interference (PLI), baseline wander (BW), motion artifacts, UCs, high frequency noises, etc., making it challenging for healthcare professionals to diagnose [69]. The major challenges are as follows.

- Signal conduction barriers: Anatomical layers, such as amniotic fluid, fat tissues, and vernix caseosa, impede the signal conduction between the fetus and the mother’s abdomen. The layers include intestines, fetal membranes, fat, muscle, uterus, placenta, and amniotic fluid [70].

- Inconsistent heart rhythm: The fetal heart chamber’s growth from the 2nd to 37th week lead to variability in the rhythm.

- Fetal movements: Locating the fetal heart position is challenging due to the movement of the fetus inside the uterus. This leads to the improper positioning of electrodes on the maternal abdomen when capturing fECG signals.

- Signal disturbances: Noises, PLI, artifacts, and UCs degrade fECG signal quality. The dynamic growth of the fetal heart throughout gestation further complicates consistent signal recording.

3. Databases

Researchers have utilized publicly available databases for validating the performance of proposed algorithms for fECG extraction. Popularly used databases are fetal ECG synthetic (FECGSYN) [71,72], abdominal and direct fetal electrocardiogram (ADFECG) [72,73], non-invasive fetal electrocardiogram (NIFECG) [72], non-invasive fetal electrocardiogram arrhythmia (NIFEA) [72,74], computing in cardiology challenge 2013 (CinC 2013) [72], DaISy [16], and fetal electrocardiograms, direct and abdominal with reference heart beat annotations (FECGDARHA) databases [75].

Table 1 represents a comprehensive overview of various fECG databases, summarizing aspects, such as the dataset name, recording duration, and sampling frequency. The number of signals present in each dataset varies significantly, with some datasets containing as few as four signals, while others include up to 100. Additionally, it outlines the types of available signals, which encompass aECG, mECG, fECG, and direct fECG (electrodes placed over fetal scalps). This analysis indicates information about annotations (i.e., labeled data) and specifies the number of subjects that participated during data acquisition. A brief description of each database is provided below.

Table 1.

The publicly available fECG databases used for identifying fetal heart conditions.

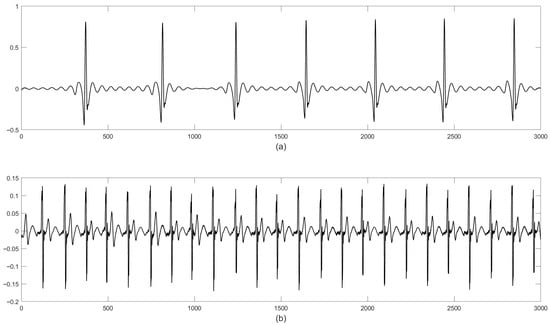

FECGSYN consists of 1750 synthetically generated abdominal signals of a 5 min duration, collected by 34 channels (32 abdominal and 2 maternal signals) having a sampling frequency of 250 Hz with 16-bit resolution. This database was created by simulating 10 different pregnancies having 07 different physiological events (such as the baseline and case0-case5). For each subject, five noise levels and seven noise cases were considered. These signals were generated for 0–12 dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in steps of 3 dB. Each signal was generated five times for statistical purposes. They consisted of fECG, mECG, Noise-1, and Noise-2. The synthetically generated mECG and fECG signals are represented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Representation of the signals in the FECGSYN database: (a) mECG and (b) fECG. The x-axis and y-axis represent the magnitude and time, respectively.

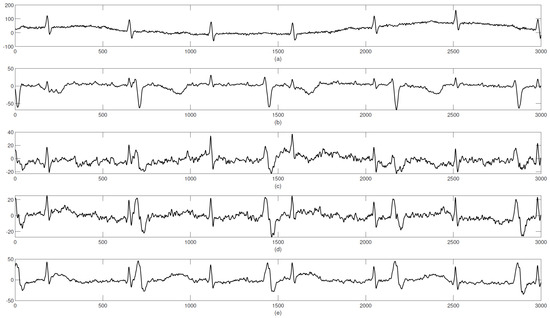

The ADFECG database was recorded at the Department of Obstetrics, Medical University of Silesia, using the KOMPOREL system from five different women in labor during 38–41 weeks of gestation. Each recorded dataset has four differential signals (collected by placing four electrodes around the navel region of the expecting mother) and one direct fECG signal, recorded from the fetal head. Each signal was recorded for a duration of 5 min and had a sampling frequency of 1 kHz. This database contains reference scalp fECG signals. The aECG recordings are represented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Graphical representation of the signals in the ADFECG database: (a–e) aECG signals.

NIFECG consists of 55 recordings (with a duration of 54 secs and a sampling frequency of 1 kHz) collected from a single pregnant women during 21–40 weeks of gestation. Each record has four abdominal and two thoracic signals.

The CinC 2013 database consists of 447 mins of data collected from five databases and named Challenge 2013 (grouped into training set-A and test set-B, having 25 and 100 recordings, respectively, with a sampling frequency of 1 kHz). The fetal QRS is annotated for set-A and is available publicly, whereas test set-B is not publicly available.

NIFEA includes arrhythmia conditions, with 4/5 abdominal signals and 1 thoracic maternal signal with a sampling frequency of 500 Hz or 1 kHz. These signals were recorded using Cardiolab CS software (version 8.0/8.1). Each data provides 26 fetus, 12 arrhythmic, and 14 normal recordings. The average duration for arrhythmic and normal rhythms were 783 s and 606 s, respectively. It has annotations related to diagnostic information and gestation age.

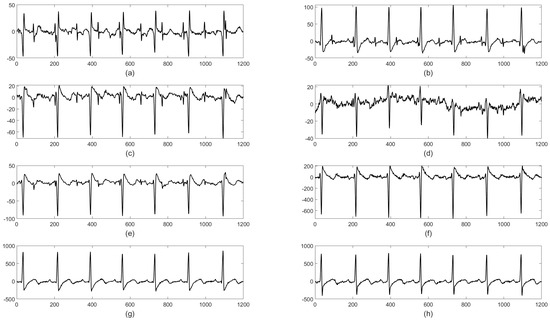

The DaISy database consists of eight signals, having 2500 samples each with a sampling frequency of 250 Hz. In this data, the first three channels represent fECG signals, whereas the remaining five channels represent aECG signals. The database has a higher SNR and the fECG component, which is clearly identified from the aECG. Noise associated with aECG is smooth. The signals are represented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Graphical representation of the ECG signals available in the DaISy database: (a–e) aECG and (f–h) mECG.

FECGDARHA consists of 10 instances of 12 min recordings during pregnancy and 12 instances of 5 min recordings during labor. These recordings were captured by the KOMPOREL system (consisting of a recorder module and computer). The recorder module exhibits low noise, high suppression ratio for common interference with an amplification of micro volts to several volts, along with overcoming the possible loss due to electrode contact with skin. The filter and amplification unit produces fECG signals in a frequency range of 0.05–150 Hz. These signals were digitized into a 16-bit resolution, whereas they were sampled @ 500 Hz and 1 kHz for aECG and direct-fECG, respectively. The information of the recorded signals are stored in binary/text/graphics files. In this case, the A1–A4 electrodes were positioned around the naval line along with a reference electrode ‘V0’ (placed above the pubic symphysis). An additional reference electrode (‘N’) was attached to the patient leg. These recorded signals were filtered for eliminating PLI for the detection of QRS. The B1 pregnancy signal consists of 10 records marked as B1_pregnancy_X (‘X’ represents record number, each having four files with duration of 20 min and sampling frequency of 500 Hz). The binary file B1_abSignals_X.ecg were saved in LabView format and text file format (i.e., B1_abSignals_X.txt). The B1_Maternal_R_X.txt contains information on fiducial points, indicating a maternal QRS complex. The pregnancy dataset contains a total 18,936 maternal-QRS and 28,405 fetal-QRS points. Labor signals were recorded during active labor (consisting of direct fECG and aECG) for the accurate estimation of FHR. It consists of 12 records marked as B2_Labor_X (where ‘X’ represents record numbers and each consists of five data files (r01, r04, r07, r08, and r10)). These were resampled @ 1 kHz for the purposes of comparing with fECG. Each binary file B2_abSignals_X.ecg saved in LabView format consist of four abdominal signals after preliminary filtering and after suppressing interfering mECG signals. These are available in B2_abSignals_X.txt and B2_dFECG_X.txt. The current data consists of 12 records with an amplitude relation of the individual components with abnormal signals.

4. Metrics Used for the Evaluation of the Model’s Performance

Many quantitative performance metrics are used to evaluate the effectiveness and accuracy of a system or model, particularly within fields such as machine learning (ML) and signal processing. These metrics offer valuable insights into how well a model or technique meets its intended objectives. Common performance metrics include the accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, sensitivity, specificity, etc. [76]. The necessity of evaluating models using performance metrics stems from their ability to provide a standardized means of comparing different approaches, ensuring that decisions are grounded in objective, measurable criteria [77]. Without adequate evaluation, it becomes challenging to discern a system’s strengths and weaknesses, potentially leading to models that do not generalize well to new, unseen data. Additionally, performance metrics are essential for identifying areas for improvement, facilitating continuous refinement and optimization of models to enhance their reliability and applicability in real-world scenarios. Table 2 summarizes the various metrics available in the literature to evaluate a model’s performance for fECG extraction.

Table 2.

Performance metrics used for fECG analysis.

5. Algorithms for Extracting fECG

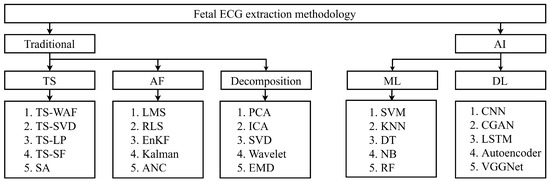

Researchers have proposed various techniques (i.e., traditional and AI) to combat challenges related to fECG extraction. Popularly used fECG analysis techniques in the literature are as follows: template subtraction (TS), AF, decomposition, ML- and DL-based techniques, etc. Figure 9 presents an overview of fECG extraction methodologies, categorized into traditional and AI-based approaches. Traditional methods include TS techniques like TS-weighted average filtering (TS-WAF) and TS-singular value decomposition, AF methods such as least mean squares and recursive least squares, and decomposition techniques like PCA and ICA. AI-based approaches are divided into ML methods, including SVM and KNN, and DL techniques such as CNN, LSTM, and VGGNet.

Figure 9.

An overview of the fECG extraction techniques proposed by researchers.

5.1. Template Subtraction-Based Methods

In the literature, researchers have used TS algorithms for fECG detection. The best performing and recently published methods are discussed. Jaros et al. [17] studied five TS approaches, including TS-without adaptation, TS-singular value decomposition (TS-SVD), TS-linear prediction (TS-LP), TS-scaling factor (TS-SF), and sequential analysis on a labor and pregnancy database, achieving the highest F1-score of 95.99% with SA. Their methodology involved the preprocessing of four aECG signals, the detection of maternal R-peaks using PCA and continuous wavelet transform (CWT), the extraction of fECG with a TS approach, and performance evaluation using F1-score. Preprocessing was performed by a FIR filter of an order of 500 with a BPF cut-off frequency of 5–70 Hz. Accurate R-peak detection in mECG was accomplished through PCA-CWT, followed by a fifth-level CWT decomposition using a Gaussian wavelet and the detection of local maxima and minima through adaptive thresholding and zero-crossing.

Sarafan et al. used TS on the PhysioNet Challenge 2013 database and reported an F1-score of 71.02% and 82.65% with and without motion noise, respectively [78]. The TS-SVD algorithm was used by Kanjilal et al. on composite mECG signals obtained from pregnant women [79]. Vullings et al. used TS-LP for identifying fECG signals from 49 synthetic and 7 real aECG recordings, and they reported 90.1% sensitivity [80]. Cerutti et al. [81] used TS-SF on aECG recordings obtained from 20 pregnant women. Martens et al. used SA on 20 pregnant women and obtained an accuracy of 85% [82]. Andreotti et al. used multiple TS techniques (i.e., TS-SVD and TS-SF), as well as the TS-extended Kalman filter (TS-EKF), on multi-channel synthetic signals, and they reported an F1-score of 96% [71]. Souriau et al. [83] applied discrete wavelet transform (DWT) on the FECGSYNDB dataset for extracting fECG signals. The TS technique was used for fECG extraction by Liu et al. and recorded an accuracy of 95% on the PhysioNet Challenge 2013 dataset [84]. NMF was used by Gurve et al. [43] on the ADFECG and PhysioNet databases for identifying fetal R-peaks, and they reported F1-scores of 94.8% and 84%. A combination of fractional Fourier transform (Fr-FT) and DWT was used for fECG peak detection by Krupa et al. on the DaISy, PhysioNet Challenge 2013, and real-time datasets for fECG analysis, and they obtained an overall accuracy of 98.12% [85]. In another work of Krupa et al. [86], the stationary transform (ST) approach was experimented with on the DaISy, PhysioNet Challenge 2013, ADFECG, and NIFEA datasets, and they reported an accuracy of 96.6%, 97.37%, 98.55%, and 99.87%, respectively.

The TS techniques have shown potential in certain applications; however, several challenges and limitations persist, which are detailed in Table 3. These include poor performance for some methodologies, particularly when applied to complex or noisy datasets. A significant constraint are the limited datasets available, which restricts the robustness and reliability of such techniques. Additionally, fetal diseases remain undetected in many cases, undermining their practical application in healthcare. These techniques often fail in the presence of noise and overlapping conditions, which are common in real-world data [87]. A significant challenge is the difficulty in selecting proper features for fECG and mECG signal extraction and analysis. Furthermore, most of the approaches fail to consider multi-class conditions, which limits their scalability and applicability in more diverse and demanding environments. These issues highlight the need for advancements and more robust solutions in this domain.

Table 3.

The challenges and limitations of template subtraction techniques in fECG analysis.

5.2. Adaptive Filtering-Based Methods

Dhas and Suchetha [20] developed a 38-tap adaptive non-causal filter to separate the fECG from aECG recordings available in the PhysioNet ATM and DaISy databases. They implemented it on a Virtex-VC707 FPGA, achieving a correlation coefficient of 0.9851, a peak root mean square difference (PRD) of 83.04%, a SNR of 8.52 dB, a root mean square error (RMSE) of 0.208, and a fetal R-peak detection accuracy of 97.09%. Additionally, the analysis for a 64-tap filter showed a maximum clock frequency of 139.47 MHz with a power consumption of 1.287 watts.

Xuan et al. [89] explored fetal ECG extraction using a combination of RLS and LMS adaptive filters from the DaISy database. The RLS filters utilized strategic forgetting factors for quick adaptation and effective signal processing. Their hybrid method showed enhanced convergence, stability, and tracking performance. Evaluating the model performance with the SNR and mean square error (MSE), the CRLS combination achieved the highest SNR and best noise suppression. By detecting fetal R-peaks, they reported 95.24% sensitivity, 87% accuracy, 90.91% positive predictive value, and 93.02% F1-score for channel-2 signals, demonstrating that combined adaptive filters are superior to single-filter approaches in fECG separation.

Sulas et al. [90] developed a multi-reference QRD-RLS adaptive filtering technique to extract fetal QRS complexes while suppressing mECG signals. The database was collected at S. Michele Hospital in Cagliari, Italy, and it made used of 9 electrodes from 10 healthy pregnant women. The researchers utilized the signal-to-interference ratio (SIR) as their primary analytical metric, calculating the ratio of maternal QRS-complex amplitude to its peak-to-peak value. Higher SIR values indicated more effective mECG cancellation, while lower values suggested significant mECG presence. By computing mECG attenuation through a logarithmic calculation of processed and unprocessed signal amplitudes, the authors achieved a maximum accuracy of 93%. However, the method produced high levels of residual noise, indicating potential for further refinement in fECG signal extraction.

Ma et al. [31] introduced an advanced non-linear MSANC for extracting fECG signals using multi-primary and multi-reference channels. MSANC combines linear and non-linear filters, such as FIR, Volterra filters, and a functional link artificial neural network (FLANN). The model uses non-linear expansions of reference signals as inputs, with RLS and LMS algorithms dynamically updating the weights. It was validated on PNIFECGDB from the PhysioNet ATM and DaISy databases, and the method achieved 99.33% sensitivity, 100% positive predictive value, 99.67% F1-score, and a mean heart rate of 93.29%.

Martinek et al. [91] performed a comprehensive investigation of LMS-based FIR adaptive filters, including normalized LMS (NLMS), block LMS (BLMS), and delay LMS (DLMS), for extracting the fECG from mECG signals using synthetic data in MATLAB (R2025a, 25.1). The authors evaluated the filter performance through the SNR, PSNR, RMSE, and PRD. These metrics were used to assess the signal similarity, noise reduction, and estimation accuracy, with lower values indicating better signal separation. For the LMS algorithm with a step size of 0.0006, they achieved minimal performance metrics: an SNR of 0.003, a PRD of 5.533, and an RMSE of 0.008. However, the study was limited to synthetic data and did not validate the approach with real-time recordings.

Niknazar et al. [92] proposed a non-linear decomposition method using EKF for extracting R-peaks from single-channel ECG signals. This approach employs backward recursive smoothing to detect fECG and mECG peaks. The technique involves a recursive decomposition process, where dominant mECG was first extracted from raw signals with Gaussian noise. By subtracting these extracted signals, residual signals were obtained, from which fECG is extracted through sequential EKF. The method was validated on DaISy and a non-invasive fECG database, and the performance was evaluated using SNR, SIR, amplitude, and heart rate metrics. However, the approach demonstrated limitations in multi-channel signal R-peak detection.

Fotiadou et al. [93] proposed a method to improve the quality of extraction of multi-channel fECG signals by using the TS-AF technique. The TS-AF method comprises a series of adaptive filters that work together to enhance each sample of the ECG signal. The process involves pre-processing, application of the TS-AF, and post-processing using overlapping filters. The TS-AF’s effectiveness was evaluated using simulated (i.e., FECGSYN) and real fetal ECG (i.e., ADFECGDB) databases. The performance was evaluated in terms of SNR, but it struggled with ectopic beats and failed in the accurate identification of the specific intervals within the ECG signal.

Kahankova et al. [94] assessed RLS-based FIR adaptive filters for extracting fECG from aECG signals. They employed multi-channel adaptive noise cancellation to optimize the RLS and FTF algorithms for removing mECG noise. The RLS algorithm, with a filter length of M = 10, achieved an SNR of −0.422 dB, with a PRD of 9.260% and an RMSE of 0.010. In contrast, the optimized FTF algorithm (step size = 0.0100) provided better results (PRD of 6.319% and RMSE of 0.009), but was computationally prolonged. (i.e., 38.439 s).

Dhas and Suchetha [95] introduced a linearization technique for fECG extraction within a non-causal filtering framework. This approach improves adaptive filtering performance by aligning abdominal and thoracic ECG baselines, leading to enhanced data analysis. The method utilizes slope detection and the Pan–Tompkins algorithm to locate maternal R-peaks, which are then used for slope estimation and linearization. A non-causal filter isolates fECG signals from the linearized abdominal signal, applying cumulative output estimation and weight updates. Their algorithm, tested on the DaISy and PhysioNet databases, achieved an FmSNR of 8.63 dB, a value of 0.9872, an RPDA of 97.21%, and a PRD of 81.98% on PhysioNet, with the DaISy database yielding an RPDA of 94.67%.

Kahankova et al. [96] employed an adaptive linear neuron (i.e., ADALINE) to derive fECG signals from aECG. This approach was tested on both the synthetic and real datasets available in PhysioNet. The effectiveness of this technique was assessed using SNR and RMSE.

Abel et al. [97] used multiple sub-filters (MSF) with adaptive noise cancellation (ANC) to extract the fECG signals from the DaISy database. Each sub-filter was updated via the LMS algorithm. A long filter was splitted into K lower-order sub-filters, which were updated in parallel to improve convergence. The authors reported an accuracy of 84.61% for MSF-ANC and 68.75% for SLF-ANC, with F1-scores of 91.66% for MSF-ANC and 81.48% for SLF-ANC.

Rodriguez et al. [98] utilized the MAX-ECG wearable device to collect the heart signals, body temperature, and motion from pregnant women, and transmitting the data to an Android device through Bluetooth for extracting fECG signals by SVD. They computed various maternal components (such as baseline signals, fetal and maternal heart rates, and uterine contractions), but they also reported poor performance that required validation on clinical data.

Mekhfioui et al. [99] developed an IoT-based system for capturing ECG recordings from both the mother and fetus. The system includes an acquisition block with electrodes placed on the thorax and abdomen, a communication link for signal transmission, and a mobile application created with Flutter for displaying health parameters. The ECG signals are processed via Arduino Due and MATLAB using BSS techniques to compute the heart rate, R-R interval, Q-T interval, blood oxygen saturation (SpO2), and body temperature. A wristband with an SpO2 sensor and OLED display transmits health data for real-time analysis over Wi-Fi. R-R intervals for the mothers were recorded to be 600–1200 ms, and it was 300–600 ms for the fetuses. Meanwhile, the heart rates were 60–100 bpm for mothers and 105–150 bpm for fetuses.

Faiz and Kale [100] used four adaptive noise canceler algorithms (such as the least mean mixed-norm (LMMN) and least mean fourth (LMF)) in cascade for the removal of four artifacts (such as the BW, motion artifacts, muscle artifacts, and 60 Hz PLI) from PhysioNet ATM (MIT-BIH noise stress test database (NSTDB)) and MIT-BIH arrhythmia database (MITDB), and they obtained an SNR improvement of 12.7319 dB.

Siew et al. [101] calculated mother and fetus heart rates from the DaISy database using a combination of a 3rd order Butterworth filter and a 6th order Savitzky–Golay filter (frame length = 31) followed by a windowing process. The authors reported that Chebyshev filters offered better roll-off than the Butterworth low-pass filter. The method involved computing the difference of the signals between the first and third leads for effective extraction of the dominant fECG signals for computing the heart rate for both the mother and fetus. The authors reported heart rates of 85.5 bpm and 132.5 bpm for the mother and fetus, respectively.

Sarafan et al. [102] proposed an ensemble Kalman filter (EnKF) with an ensemble size of 70 for single-channel non-invasive fECG separation using data from PhysioNet Challenge 2013 and recordings from 20 pregnant women. This variant of the Kalman filter performed better in the presence of motion noise, achieving an average positive predictive value (PPV) of 97.59%, a sensitivity of 96.91%, and an F1-score of 97.25% when detecting the R-peaks from the Challenge 2013 data.

A low-distortion adaptive Savitzky–Golay (LDASG) filter, designed by Huang et al. [103], separated fECG signals from the PhysioNet ATM database. It addressed the adaptability issues found in traditional Savitzky–Golay filters, enhancing denoising performance and accurately reproducing QRS complexes. The filter computes the curvature using tangent variations and the longest digital straight segments, retaining critical ECG information and reducing MSE by 33.33%.

Martinek et al. [104] optimized adaptive filter parameters (step size ‘’ and filter order ‘N’) for monitoring the fECG from aECG signals collected at 3M Corporate Headquarters using LabVIEW. By combining stochastic gradient and optimal recursive adaptation approaches for LMS and RLS algorithms, the authors identified the optimal electrode positions for detecting fetal hypoxia. The extraction quality of fECG was assessed through SNR, sensitivity, and PPV, with a focus on the output SNR relative to filter parameters, which were presented in optimization graphs.

Suganthy and Manjula [105] exploited the low-frequency nature of fECG signals through time-frequency transformations using stationary wavelet transform (SWT) and weighted least square regression (WLSR). These transforms were combined with a parallel EKF to extract the fECG signals from the DaISy database. SWT decomposes the aECG signal into low- and high-frequency components, and it avoids information loss. The EKF estimates mECG parameters, which are subtracted from the original signal to obtain fECG signals, reporting a peak SNR of 33.5858 dB for first signal in the DaISy database.

Taha and Raheem [106] utilized input-mode and output-mode adaptive filters (using RLS, LMS, and a single reference block) to extract fECG from aECG signals. In input-mode adaptive filtering (IMAF), aECG served as the primary input, while the windowed aECG at QRS locations in mECG acted as the reference. In output-mode adaptive filtering (OMAF), the primary signal was the output from BSS, with the reference being the windowed fECG corresponding to QRS locations. The authors employed an idempotent transformation matrix (ITM) for BSS, and they tested their methods on the DaISy and PhysioNet databases, evaluating performance by the SNR. OM-RLS outperformed OM-LMS in fECG separation, but a post-processing stage was required to enhance the fECG quality.

AF techniques, widely used for fECG extraction, face several limitations, which are summarized in Table 4. The performance of the AF technique is highly dependent on the accurate selection of the reference mECG signal and the effectiveness of the adaptive algorithm employed. Many studies in this domain are constrained by experimentation on limited datasets, reducing the generalizability of the findings [107]. Furthermore, these methods often exhibit poor performance in extracting fECG signals under challenging conditions, such as noise or overlapping signals [108,109]. They often end up removing critical and important information in fECG signals, which may lead to misdiagnosis and delayed treatment, resulting in life-threatening conditions for the fetus. Additionally, this method fails in detecting fetal heart abnormalities, which restricts their clinical applicability in prenatal diagnostics [110,111]. These challenges highlight the need for more robust and comprehensive techniques.

Table 4.

Analysis of the adaptive filtering techniques for fECG extraction.

5.3. Wavelet Decomposition-Based Methods

Darsana and Vaegae [114] devised a hybrid methodology that integrates AF (i.e., RLS) and WT, followed by spatially selective noise filtration (SSNF) to eliminate noise and extract fECG. The WT was utilized as a preliminary processing step to analyze the non-stationary and transient components of the fECG signal, which correspond to R-peaks, by breaking it down into low- and high-frequency elements. This approach enables a detailed examination of fECG signals in the time-frequency domain while effectively removing the associated noise. The authors carefully selected the appropriate mother wavelet and decomposition level, along with a suitable noise removal technique. In this study, a five-level wavelet decomposition was performed using a Bior 1.5 mother wavelet, which facilitates the extraction of finer details from both the approximation and detail coefficients. The coefficients were, subsequently, processed using the RLS algorithm. The abdominal signal served as input, while the thoracic ECG was used as the reference for AF. The filtered wavelet coefficients underwent SSNF, followed by an inverse WT to produce the fECG. This methodology was tested on the DaISy (excluding the fourth channel due to instability) and NIFECG databases. The R-peak detection performance was determined to be 97.01% for the DaISy database and 94.35% for the NIFECG database. However, this approach was not used to investigate abnormal heart rate activities.

Wu et al. [112] employed the WT and LMS algorithms to separate the R-peaks of fECG and mECG signals by using SSNF. The authors executed five-level wavelet decomposition on the processed aECG and thoracic ECG signals using a Bior 1.5 mother wavelet. The coefficients obtained at each scale were processed by the LMS adaptive algorithm. In this instance, coefficients derived from the abdominal signal were treated as the reference input for AF. These processed coefficients were then utilized to compute the correlation, with a threshold established to eliminate noise. The wavelet coefficients that had been processed were reconstructed using inverse SWT. The method’s feasibility was assessed using the DaISy database, and the quality of the predicted fECG was measured by SNR.

Sharma et al. [115] utilized an ANFIS combined with undecimated wavelet transform (UWT) to extract the fECG signals from a simulated aECG database. UWT is a linear shift invariant method employed to decompose signals into various frequency components. In this method, the noise, mECG signals, and fECG signals serve as inputs, while mECG acts as the reference. The authors applied soft thresholding to the detail coefficients obtained through UWT, followed by inverse UWT to estimate fECG. This technique did not completely eliminate noise from fECG. The method’s performance was assessed using MSE and comparing the denoised fECG (extracted fECG) with the original fECG signal.

Manea and Țarălungă [116] extracted fECG and FHR using a three-step process. The first step involved pre-processing through empirical mode decomposition (EMD), empirical wavelet transform (EWT), and normalization, which decomposed the signal into intrinsic mode functions (IMFs) to address high-frequency noise and artifacts. In the second step, Fr-FT and maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) were used to identify the mECG signals from the processed signals, helping to detect maternal R-peaks. The final step applied a band-pass filter (15–40 Hz) to extract the fECG signals while preserving fetal R-peaks. This method was validated using the PhysioNet Challenge 2013 database, achieving an accuracy of 93.47% and sensitivity of 94.91%.

Jallouli et al. [117] introduced a multi-wavelet approach combined with entropy measures to extract the fECG from aECG signals. The results were applied using Clifford wavelets, as developed by Arfaoui et al., and Haar–Faber–Schauder wavelets for comparative analysis. Their study was conducted on the DaISy and Challenge 2013 databases, and they achieved an overall sensitivity and PPV of 100% for both metrics.

Wavelet approaches have notable limitations. A key challenge lies in selecting the appropriate wavelet basis and decomposition level, as an improper choice can significantly affect performance [118,119]. Wavelet methods are sensitive to noise, which can distort the extracted signal, especially in real-world datasets with overlapping maternal and fetal signals. Moreover, these techniques often require high computational resources, making them less suitable for real-time applications [119,120]. Additionally, wavelet-based methods have largely focused on signal extraction rather than on detecting fetal heart abnormalities, limiting their diagnostic potential. Table 5 summarizes the wavelet techniques for fECG extraction used by researchers in the literature.

Table 5.

Comparative analysis of the wavelet methods for detecting fECG signals.

5.4. Blind Source Separation-Based Methods

Zhang et al. [113] proposed extensive ANC for removing noisy artifacts from aECG for clear extraction of fECG signals. It combined the strength of SVD and smooth window (SW) for estimating mECG from aECG signals, which was further used as an artificial reference signal in ANC. The combined approach consisted of pre-processing and QRS complex detection from mECG signals followed by two parallel steps (such as estimating QRS by SVD and SW for estimating inter-QRS). The output of the parallel steps were concatenated for estimating mECG signals. The model was validated on the ADFECG database available in PhysioNet ATM bank and the clinical data obtained by BIOPAC Acquisition Systems, Inc. (Goleta, CA, USA) equipped with an ECG100C module @ PLA Navy Anqing Hospital, Anhui, China. The authors reported an F1-score for the r01 and r07 signals from the ADFECG database, and on a private dataset. The F1-scores were 99.61%, 99.28%, and 98.58%, respectively, for fetal-QRS detection. Kanjial and colleagues [79] used SVD for estimating the principal components correlated to the mECG signals present in aECG and estimated mECG signals, which was later nullified to obtain clean fECG signals. Maximum accuracy recorded for the above mentioned databases was 98.57%.

Samuel and Hota [121] proposed a three-stage hybrid-cum-adaptive approach by fusing FICA, adaptive exponential functional link network (AEFLN), and wavelet thresholding on the PhysioNet ATM (Challenge 2013 and ADFECG) and DaISy databases for extracting fECG signals. The aECG signals were pre-processed using 4th order band pass filters with frequency range of 3–150 Hz for removing BW and high-frequency noise, and this was followed by FICA to obtain three independent components (such as approximated mECG, aECG (with dominant fetal component), and unwanted signals). The approximated mECG (i.e., the reference) and enhanced aECG (i.e., desired) signals were used by the AEFLN algorithm for producing residual fECG signals. This signal was thresholded using 3-level wavelet decomposition (by ‘db10’ mother wavelet) for identifying fetal R-peaks (f-R-peaks). In this step, adaptive thresholding value was computed (closely related with fetal-R-peaks) for approximation and detail coefficients. From the detected R-peaks, the authors computed an FHR of 29.72 bpm2. The method attained sensitivity, PPV, and F1-scores of 95.29%, 96.68%, and 95.92%, respectively, for R-peak detection.

Liu and Luan [84] proposed a combined algorithm of FICA, ensemble EMD (EEMD), and wavelet shrinkage (WS) for separating and denoising the fECG from aECG signals obtained by the OSET/ECGSYN and ADFECG databases. The ICA algorithm was used to separate the aECG signals into noisy fECG, which was partially cleared by EEMD and then later subjected to WS for reducing high-frequency noise and the baseline to obtain the fECG signals. EEMD was used on the data-driven basis function adaptively, and it did not require any prior knowledge. The denoising quality of the fECG signal was evaluated by SNR, MSE, and the correlation coefficient.

Islam and Tarique [122] used FICA and PCA along with whitening for extracting the fECG signals from the DaISy database, and they compared this with direct fECG by computing the SNR. The authors did not analyze the morphology of the extracted fECG signals.

Kaur and Dewan [123] compared the performance of three BSS algorithms, i.e., FICA, PCA, and SVD, for isolating the fECG from aECG signals present in the FECGSYN database (which consists of separate fetal, maternal, noise-1, and noise-2 components). These signals were added linearly to synthetically generate aECG signals, which were then subjected to preprocessing (by a 7th order Butterworth IIR high-pass filter for eliminating the baseline drift and low-frequency components). IIR notch was used for eradicating narrow band PLI, whereas a 3rd order IIR low-pass filter with a cut-off frequency of 100 Hz was used for removing residual noise, like electromyography, white-Gaussian noise, and motion artifacts). Decomposition was carried out by BSS algorithms (i.e., ICA, PCA, and SVD), and post-processing was performed by WD to identify the sharp changes, which was followed by filtering with a Savitzky–Golay filter (for preserving the morphology) and then by performance evaluation with various metrics (such as the kurtosis, skewness, entropy, accuracy, RMS, SNR, mean, and median). FICA performed better extraction in terms of accuracy, kurtosis, entropy, and RMS compared to PCA and SVD. PCA outperformed in terms of higher SNR for the signal quality. A positive skewness of 4.08 with a higher mean (0.0012) and a higher median value (0.0097) were recorded when separating the signals by SVD. This method needs to be validated on clinical data.

Barnova et al. [124] developed a technique integrating ICA, fast transverse filter (FTF), and complementary EEMD with adaptive noise (CEEMDAN) to extract fECG signals from the PhysioNet 2013 Challenge and FECGDARHA databases. They pre-processed aECG signals with higher fetal magnitude using a FIR BPF (a cutoff frequency of 3–150 Hz) to reduce noise, and they applied the FICA algorithm to decompose the signals, isolating the desired fECG. The FTF algorithm aligned the first two components, minimizing the error relative to mECG, which was then subtracted from the aECG to yield the fECG signals. This approach achieved a 92.98% accuracy, a 95.33% sensitivity, and a 95.86% F1-score on the extracted fECG signals (from FECGSYNDB). But, a lower accuracy of 78.47% was reported for the Challenge 2013 database. The highest accuracy (i.e., 97.30% for ADFECGDB and 97.08% for Challenge 2013) was found using WT with clustering. The authors suggested further experimentation on pathological records, but they did not categorize the fECG signals into physiological and pathological types.

Mirza and colleagues [125] used ICA and AF for extracting fECG signals from a customized personal database. Yerande et al. [126] proposed a hybrid approach (using FICA and LMS-AF) for extracting fECG signals and computing heart beats from the ADFECG database. The authors reported a 18.09 dB SNR for fECG extraction. This method was not applied to the fetal cardiac disease. Clemente and colleagues [127] used dimensionality reduction by PCA, followed by extraction of fECG signals by FICA and a post-processing stage. The authors used open-source synthetic data (generated by ECG Toolbox for the maternal and fECG signals, along with realistic noise) and the DaISy database. The performance of this approach was evaluated by the correlation coefficient. Ghazdali et al. [19] introduced bilateral total variation (BTV) for denoising, followed by minimization of the copula densities by Kullbark–Leibler divergence for the purposes of separating the fECG signals from the synthetic data.

Jaros et al. [3] studied 11 different types of ICA algorithms (AMUSE, ERICA, FICA, FlexICA, Infomax, JADE, KICA, RADICAL, Robust ICA, SIMBEC, and SOBI) with adaptive FTF for extracting the fECG signals from the recordings obtained from the Labour and Pregnancy dataset. This approach consists of pre-processing (by a 500th order FIR filter with a frequency range between 5 and 50 Hz for eradicating isoline fluctuations); ICA (for separating the mECG signals, aECG signals, and noise); automatic selection of aECG and mECG signals (based on amplitude and QRS complexes); a FTF filter (modifying mECG signals corresponding to its component in aECG signals for the subtraction of aECG to obtain fECG signals); the detection of R-peaks (using CWT); and statistical evaluation. The extraction of fECG signals was experimented with 11 ICA algorithms, out of which the FICA-FTF combination yielded the best results in terms of accuracy (83.72%), sensitivity (92.13%), PPV (90.16%), and F1-score (91.14%), with a computation speed of 0.452 s.

Taha and Rahmeen [128] used a variant of the BSS algorithm, i.e., null space ITM, for extracting the fECG signals from the DaISy database, Challenge 2013 database, and FECGSYN database. Initially, the aECG recordings were filtered by a cascade of low-pass Butterworth (cut-off frequency of 100 Hz), high-pass (cut-off frequency of 0.5 Hz), and notch filters for removing the baseline wander and PLI. The filtered signals were subjected to ITM for identifying the null space solution for obtaining raw fECG and mECG signals. The extracted raw fECG signals were post-processed using an adaptive comb filter, peak detection, control logic, and mECG removal. The R-peaks of the raw fECG and mECG signals were detected by the Pan–Tompkins algorithm. Control logic was used to remove the unwanted mECG peaks from the raw fECG signals. The mECG block helped obtain clean fECG signals using an adaptive comb filter. This method attained a mean accuracy of 97% for the Challenge 2013 database. This method could not completely remove the background noise from the signal.

It is essential to know the nature of noise before applying the BSS algorithm for a proper separation of fECG from mECG signals, especially in the presence of noise or overlapping components, which can compromise signal quality [129]. The performance of BSS methods is highly dependent on assumptions about the statistical independence or sparsity of the sources, which may not always hold in real-world scenarios [130,131]. Additionally, these techniques often demand substantial computational resources, making real-time applications difficult. The limitations and comparative analysis of various BSS techniques are discussed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Analysis of BSS techniques used for fECG extraction.

5.5. Machine Learning-Based Methods

Various ML techniques, such as Naive Bayes (NB), Fuzzy systems, random forests (RF), decision trees (DT), etc., are presented in the literature for fECG extraction. Some of the recent ML advances are described below.

Joseph et al. [132] used a multi-combi BSS algorithm for separating fECG from aECG signals (obtained from PhysioNet ATM bank), followed by the extraction of morphological features and classification by an enhanced NB classification technique for identifying five different classes of diseases (atrial fibrillation, first degree block, paced, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, ventricular tachycardia, and idioventricular rhythm). The authors used intervals (i.e., PR, PT, ST, TT, and QT), the maximum magnitude of the peaks (i.e., P, Q, R, S, and T), and the number of R-peaks as features for the classification algorithm. In this work, NB was used due to its simplicity, the uncorrelated nature of the features, and its requirement of needing few training samples. The method’s performance was evaluated by calculating PSNR for the BSS algorithm, whereas the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity were computed for the NB classifier. NB classification attained an accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of 96.56%, 89.56%, and 97.54%, respectively.

Sharma et al. [115] developed a composite model that integrates the advantageous features of the ANFIS and the UWT to extract the fECG signals from a simulated ECG database. ANFIS was utilized to estimate the fECG from mECG signals, using noisy mECG as a reference. Initially, the fECG signals were estimated using ANFIS, after which UWT was applied to derive both the approximation and detail coefficients. The high-frequency components, or detail coefficients, were thresholded, followed by the inverse UWT being applied to the approximation coefficient, resulting in the estimated fECG. This method was validated using a simulated database of both mECG and fECG signals.

AbuHantash et al. [133] used a swarm decomposition for isolating fECG from aECG signals. They used higher-order statistics for identifying R-peaks. This method consisted of pre-processing (by Butterworth and notch filters with a cut-off frequency of 3–80 Hz and 50 Hz, respectively), swarm decomposition (for converting aECG signals into eight oscillatory components (OCs)), followed by detection of R-peaks and a performance evaluation (by sensitivity and the positive predicative value). Swarm decomposition depends on swarm filters and the parameters’ control fine/coarse decomposition process. Iteration was stopped for a threshold limit between 0.1 and 0.05. The OCs lying below the frequency of 7 Hz were considered to be the maternal component and the residual was the fECG. The model’s performance was evaluated on the PhysioNet database, and the detected QRS complex from the fECG signals achieved a sensitivity and PPV of 97.4% and 98.6%, respectively.

Salini et al. [134] employed various ML models (such as RF, linear regression (LR), DT, SVM, voting classifiers, and KNN) to assess fetal health by analyzing patterns, such as the FHR, accelerations, decelerations, and uterine activity derived from CTG data [135]. This approach classified fetal health outcomes as abnormal, suspicious, or normal based on heart rate characteristics. The methodology included several steps: data pre-processing (normalization for scaling and enhancement of classification quality), feature selection, data splitting, model training, testing, and performance evaluation through metrics like the accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The method was evaluated on publicly available datasets (https://www.kaggle.com/dataset/andrewmvd/fetal-health-classification/data accessed on 3 August 2025), and it achieved a maximum accuracy of 93% using RF classifier. However, this method faced data-related challenges (such as noise, heterogeneity, and limited quantity), modeling issues (including over-fitting and under-fitting without adequate interpretability and explainability), clinical misinterpretations, and complexities arising from the intricate relationships between CTG features and fetal health due to variability and physiological factors.

An unsupervised learning-based approach was proposed by Shi et al. [136] for identifying the fECG quality (such as high, medium, low quality) by computing the entropy and statistical features. The overall structure of this method consisted of data acquisition (by maternal abdominal leads); pre-processing (i.e., centering, normalization, filtering by band-pass filter, and computation of spectograms); feature extraction (autoencoder, entropy, and statistical features); signal quality identification (computed based on the kurtosis, skewness, and relative power); and performance evaluation (by precision, recall, and F1-score). This technique attained an F1-score of 90% for identifying the fECG signal quality.

Bai et al. [137] utilized ML techniques (such as SVM, KNN, DT, RF, LR, NB, AdaBoost, XGBoost, bagging, stacking, and voting) to predict the fetal health status from CTG images. The CTG database was initially processed for feature extraction, resulting in 103 features that were computed according to FIGO guidelines. Subsequently, various ML classifiers were applied, and the results were evaluated using the accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, quality index, Brier score, and AUC. Their research achieved an AUC of 85.63% for 65 features on a publicly available database.

Telagathoti et al. [138] employed AF techniques for noise cancellation, which was integrated with block sparse Bayesian learning to extract fetal and maternal ECG signals. The authors utilized multiple adaptive noise cancellation methods, including LMS, NLMS, and leaky least mean squares (LLMS). This method incorporates block sparse Bayesian learning for reconstructing non-sparse signals, which consist of the following: pre-processing, interfacing mECG with fECG signals, and ANC, followed by Bayesian learning optimization to achieve the reconstructed signal.

Andreotti et al. [139] characterized the extracted fECG signals using signal quality indices (SQIs), and analyzed them with NB classifier. Their study was conducted on ECG recordings collected at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University Hospital of Leipzig, which included a database of 259 multi-channel recordings, each lasting 20 min, gathered from 107 pregnant women between 17 and 39 weeks of gestation. The fetal SQIs and fQRS annotations comprised 9605 segments (7 channels × 5 segments × 259 recordings) with a total of 465 min of data. The SQIs included the ratio of power across various spectral bands, agreement levels among different QRS detectors, consistency between beat detection across different leads, and the kurtosis of the ECG. Using these SQIs, the fECG was identified. The matrix was categorized into time-frequency methods, detection-based approaches, and fECG-specific techniques (including mxSQI, mpSQI, mcSQI, and miSQI). These features were used by a NB classifier. To enhance the classification performance, single-channel Kalman filtering and multi-channel data fusion were implemented. The efficacy of this technique was assessed through the classification accuracy (Cohen’s coefficient), FHR, heart beat detection rate, and RMSE.

ML techniques utilized for fECG extraction encounter several limitations that impede their effectiveness and clinical applicability (represented in Table 7). A primary challenge is the reliance on high-quality, labeled datasets for training, which are often scarce in this field [140]. This limited availability of data can result in overfitting, diminishing a model’s generalization ability for unseen scenarios [141,142]. Furthermore, ML models often struggle with noisy and overlapping signals that are typical in real-world fECG data, necessitating extensive pre-processing to perform effectively [143,144]. The selection of appropriate feature is also crucial for ML algorithms; however, identifying these features can be complex and highly domain-specific [145]. Many ML approaches concentrate solely on signal extraction and neglect the detection of fetal heart abnormalities, which limits their diagnostic value.

Table 7.

ML techniques used by researchers for fECG extraction: a comparative summary.

5.6. Deep Learning-Based Methods

Only a few of the researchers used DL techniques (such as GAN, CNN, RNN, and customized DNN) for reconstructing fECG, identifying fetal disorders from fECG, and computing FHR. A few of the successful methods are discussed below.

Basak et al. [146] used 1-D CycleGAN to reconstruct fECG signals while preserving the information about P-, Q-, R-, S-, and T-waves, as well as PR-, ST-, and QT-intervals. This method consisted of baseline correction, filtering, segmentation, lag cancellation, and normalization, followed by fECG reconstruction, f-QRS detection, signal morphology identification, and the computation of HRV. The 1-D-CycleGAN method maps mECG to fECG signals by generator. In this case, the authors used adversarial, spectral, temporal, and power loss for making the extracted signal morphology be identical to that of an actual ECG. This method was used to experiment on the ADFECG and FECGDARHA databases, and an average Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) and spectral correlation score (SCS) of 88.4% and 89.4%, respectively, was reported. This method detected the fetal QRS from the signal and achieved an accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score of 92.6%, 97.6%, 94.8%, and 96.4%, respectively. The technique was computationally complex, as it could not discard the excessive noise, and it was experimented with on a limited database.

Pachiyannan et al. [147] used a ML approach (consisted of CNN and Bi-LSTM) to identify CHDs in pregnant women for the purposes of accessing maternal and fetal health along with timely intervention. The important steps used in this technique consisted of data acquisition; pre-processing (i.e., segmentation, R-peak identification, and Z-score standardization); CNN; Bi-LSTM (identifying time-series information); attention (for screening out irrelevant data); classification; and performance evaluation (assessed by the accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, false positive rate, and false negative rate). This method was validated on publicly available database (obtained from the PhysioNet bank repository) and reported an average accuracy of 94.28%.

Arain et al. [148] reviewed ML approaches for predicting and diagnosing obstetric diseases, such as gestational diabetics, pre-eclampsia, pre-term birth, and fetal growth restriction, from ultrasound and MRI images. The authors used MRI images for extracting diagnostic information by a CNN network, followed by classification to predict fetal heart structures (such as the atrium and ventricle for both left and right).

Zhao et al. [149] proposed ballistocardiogram (BCG) signals for monitoring beat-to-beat intervals and HRV during sleep. This system used a single-mode fiber optic sensor under the mattress to capture the physiological changes (such as breath and heart beat) in the human body. The acquired signals were sampled at 256 Hz. The HRV monitoring algorithm consisted of pre-processing (performed by amplitude thresholding and a Butterworth band-pass filter); CWT (transformed the time domain signal to time-frequency representation for identifying prominent diagnostic features); Bi-LSTM (computed the heart beat along with prominent temporal information); and the identification of the J-peak, J-J interval, and computation of HRV. This method identified short-term and long-term HRV. This technique has recorded an accuracy for beat-to-beat interval estimation with a median error of 4.4 ms.

Liu et al. [150] used AF for identifying normal and other heart beats from single-lead ECG, and they were captured by a wireless body sensor network using an ensemble of LSTM and VGGNet. LSTM is a RNN network that overcomes the vanishing gradient problem and is much better in dealing with long-term sequences. VGGNet (i.e., VGG11 to VGG19) were mainly used for the classification of images. In this case, the 1-D time domain signal was converted to a 2-D representation by a spectogram and Poincare plot prior to classification by VGGNet. The output of LSTM and VGGNet were fed to a Bayesian weighted matrix and softmax layer for classification. The authors reported an overall F1-score of 90%. This model can be used to identify various diseases from fetal ECG signals.

Fang et al. [6] used a dual-channel neural network for AF identification from a single-lead ECG, where they experimented on the 2017 Challenge PhysioNet database and reported an F1-score of 83%, 90%, and 75% for AF, normal, and other beats, respectively. Initially, the 1-D ECG signal was subjected to normalization, followed by a Butterworth low-pass filter and wavelet denoising. This was then followed by 2-D representation and classification. In that case, the 1-D ECG signal was converted to 2-D time-frequency analysis (TFA), spectogram, and Poincare plot prior to classification.

Darmawahyuni et al. [151] proposed a deep neural model (consisted of a convolutional layer and bi-directional LSTM) for fetal QRS classification. Their technique consisted of fECG acquisition (i.e., the PhysioNet/CinC 2013 database); pre-processing (i.e., the removal of noise, the segmentation of beats, and the QRS complex); and tuning of the DL model, classification, and performance evaluation. The DL model made of Bi-LSTM was used for generating feature maps and for subsequently identifying the segments. The method identified the QRS complex of the fetus with 100% accuracy.

Habineza et al. [152] used DNN for identifying the patient’s baseline AF, future AF, with AF, and no AF from the CODE dataset. The DNN network has a convolutional layer followed by five residual blocks, a fully connected layer, and a softmax layer. The model was trained by minimizing the average cross entropy loss using an Adam optimizer. The authors used 70 epochs, a learning rate of with a decay of , and they reported an AUC score of 84.5%.

Ziani et al. [41] used a combination of DL, SVD, ICA, and non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) methods for identifying fECG signals and the separation of various components. The 1-D ECG signals available in the DaISy database were subjected to STFT and CWT to obtain 2-D representation. Images obtained by STFT were fed to SVD and ICA followed by CNN model for fECG extraction, whereas the images obtained by the CWT approach were decomposed by NMF for generating scalograms followed by CNN for the purposes of identifying fECG signals. The CNN model consisted of 2-convolution, 2-max pooling, 2-flatten, and 2-dense layers. This approach reported an accuracy of 94.29%.

Ghonchi and Abolghasemi [2] proposed a dual-attention mechanism composed of squeeze-and-excitation and channel-wise modules in autoencoder for the purposes of extracting fECG from aECG signals. This method followed pre-processing (consisting of band-pass filtering, windowing, and labeling) and pattern extraction (by autoencoder and Bi-LSTM). This method was used to experiment on three datasets (i.e., NIFECG-I, NIFECG-II, and ADFECG), and it reported an overall F1-score of 98.1% (trained on ADFECG and tested on NIFECG-I). The autoencoder extracted fECG patterns.

Lee and colleagues [153] proposed a W-Net architecture for extracting the fECG from aECG recordings from a simulated database (a mixture of mECG, fECG, noise, baseline signal, fetal movement, ectopic beats, uterine contraction, and condition for twins). The sequences for this technique were pre-processing (i.e., band-pass filtering having cut-off frequency 3 Hz to 90 Hz) and a W-Net architecture (consisting of two U-Net structures). The network used the mean absolute error (MAE) as the loss function for optimization and an Adam optimizer for optimizing the model. The network reported an F1-score, precision, and recall of 96.91%, 97.45%, and 95.74%, respectively, on the Challenge 2013 database, whereas the ADFECG database reported an overall F1-score, precision, and recall of 98.81%, 99.3%, and 98.23%, respectively. The method failed to extract fECG signals during the period, where the mECG signals overlapped with the fECG.