Abstract

Background/Objectives: Children with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) are managed with multi-modal treatment strategies, including non-clinical components such as the development of self-management skills. Assessment tools have been developed to quantify such traits, and parents may be asked to provide proxy reports on behalf of their child. The aim of this study was for child/parent dyads to complete a self-management skills assessment tool [IBD-STAR] to assess the agreement level between reports. Methods: Children aged ≥10 years with IBD, and one parent/caregiver, were recruited from three tertiary care centers in New Zealand, Australia, and Italy [translated version]. IBD-STAR is scored as completing skills independently [score = 2], with help [score = 1], or not at all [score = 0]. Individual agreement was assessed as a proportion of the maximum agreement on items, category agreement as inter-rater reliability using Gwets AC1 coefficient, and aggregate agreement as a Bland–Altman plot and correlations between child/parent percentage scores. Results: Fifty child/parent dyads participated; child mean age of 14.5 years (±2.4), 31 (62%) female, and 31 (62%) had Crohn’s disease and 19 (38%) ulcerative colitis. At the individual level, the mean proportional agreement was 0.70 (±0.15), equating to complete agreement on ≥12 IBD-STAR items. Category agreement was in the range of 44–94% for items, parents were more likely to underestimate self-management skills, and inter-rater reliability ranged from poor to very good for items, and ‘good’ overall. Aggregate agreement showed high correlation between child/parent % scores (R 0.77, p < 0.001, CI 0.63 to 0.87), and 47 (94%) of the pairs had % scores within two standard deviations of each other. No level of agreement was associated with any independent variable. Conclusions: Parental proxy reports of self-management skills using IBD-STAR had acceptable agreement. The trend towards parental underestimation should be considered when child self-report cannot be assessed.

1. Introduction

The incidence and prevalence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is increasing globally [1]. Children diagnosed with IBD typically present with disease that is more extensive and severe than people diagnosed as adults for both Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) [2,3]. There are also differences in treatment regimens, with children being exposed to more intensified drug therapies than adults, including higher use of advanced therapies [3]. Clinical management strategies for children with IBD aim to achieve histological remission to minimize disease complications, eliminate symptoms, and reduce psychosocial comorbidities [4,5].

Non-clinical management strategies are also gaining traction as an important component in the treatment armamentarium, with factors such as self-management increasingly recognized as playing a role. Self-management is a multi-modal approach consisting of health behaviors and processes that children and their family engage in when dealing with a chronic health condition [6,7]. Self-management centers on the development of health autonomy that eventuates in a paradigm shift of responsibility from disease management by the parent/family, to that of the child as their age and cognitive ability increases [7]. The practical aspect of self-management involves the child/adolescent with IBD learning to gradually take control of disease management tasks and develop the necessary skills to coordinate their own treatment and clinical management independently, in particular prior to transition to the adult healthcare system [8,9,10].

The assessment of self-management skills for children with IBD is an important way to monitor development of health autonomy, with longitudinal measurements enabling implementation of interventions to address identified skill deficiencies. It is increasingly recognized that children are the gold-standard source of information when it comes to their own healthcare management, with parents shown to misestimate several clinical outcomes for their child with IBD. Symptom reports generally have good agreement between parents and their child [11,12,13,14]. Parental reports of medication adherence have been shown to overestimate actual adherence by their child when measured objectively, and as dyad reports [15,16]. Parents underestimate IBD transition readiness [17], and chronic pain levels [18]. Parents consistently rate their child’s IBD health-related quality of life as being worse than their child’s self-report [12,19,20,21], as well as overestimating the presence of psychosocial symptoms [22]. While a number of self-management skills assessment tools for children with IBD have been developed [23], little is known of whether child self-report and parent proxy reports are congruent. The self-management skills assessment tool IBD-STAR [24] enables children with IBD to rate whether they can perform practical self-management skills and tasks independently. IBD-STAR was developed to be generalizable to all regions, excluding the skill of navigating, for example, health insurance systems as they are not utilized in all regions [24]. Additionally IBD-STAR was developed using an evidence-based approach that assessed other available self-management assessment tools and addressed identified issues such as being focused on adherence alone, being non-validated, and less suited to a pediatric population with IBD [7]. The aim of this study was to assess the level of agreement of IBD self-management skills reports among child/parent dyads to determine whether parents can provide reliable proxy reports.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Centres

This was a prospective multi-center observational study carried out in three tertiary care centers: Christchurch Hospital, New Zealand; Sydney Children’s Hospital, Australia; and the Pediatric Gastroenterology and Liver Unit, Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy.

2.2. Ethics and Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all parents of children participating in the study, and consent/assent was obtained from all participating children. Approval for the study carried in New Zealand was provided by the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (Health) [H16/116]. Approval for the study carried out in Australia was provided by the Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee [2020/ETH00562]. Institutional approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome, for the investigator in Italy to recruit participants from their out-patient clinics.

2.3. Populations

Parent/child dyads were recruited at specialist pediatric IBD clinics at each respective center in the years 2020 (Christchurch and Sydney) and 2022 (Rome). Children were invited to participate if they were aged 10–20 years of age, cared for by pediatric gastroenterologists, and had a formal diagnosis of IBD. One parent was recruited per child. Children were excluded if they had been diagnosed with IBD for less than three months as this will have limited their ability to develop self-management skills related to their condition. Dyads were also excluded from analysis if there were responses missing to any items on IBD-STAR.

2.4. Assessment Tool: IBD-STAR

IBD-STAR is a validated assessment tool designed to measure self-management skills in children aged 10 to 18 years with IBD [24]. IBD-STAR includes 18 scored items in five sections, answered according to whether children can carry out a self-management task by themselves (scores two), with help (scores one), or not at all (scores zero). There is a maximum score of 36 points, indicating that a child can carry out all IBD-STAR tasks independently. There is also an additional unscored section that acts as an indicator of which specific self-management facilitators may be implemented to help a child develop independence in certain skills.

2.5. Italian Cross-Cultural Adaptation

For the Italian cohort, IBD-STAR was translated into Italian using a validated methodology [25]. An expert panel of Italian gastroenterologists [N = 3] provided feedback on the cultural relevance and language/comprehension of each IBD-STAR item using a 1–10 scale. The proportion of the maximum possible score from all raters was calculated using an adapted content validity index (CVI). The individual CVI (I-CVI) for each item was required to be >0.78 with any scoring less to be reviewed, and for the tool overall the scale CVI (S-CVI) was required to be >0.8 [26]. Once ratings were complete and any edits made, IBD-STAR was translated to Italian using a forward–backwards translation process. Two independent translators interpreted IBD-STAR into Italian and then met to discuss items and decide on a final version, which was then back-translated to English by a third independent translator and sent to the New Zealand research team. Any discrepancies for individual items were addressed by discussion between the study teams in Italy and New Zealand. Due to IBD-STAR being a tool to report skills, a validation study was not possible as there are no correct/incorrect answers such as in a knowledge assessment tool.

2.6. Data Collection

Children and parents completed IBD-STAR independently, two weeks apart, to reduce the possibility of discussion/cross-contamination of scores if completed in proximity. Children completed IBD-STAR to report on their own self-management skills ability, and parents completed it to provide their opinion of their child’s self-management skills ability. Parents completed IBD-STAR straight after recruitment at IBD clinic in each center, with them being requested to conduct this without consulting their child. Children completed IBD-STAR two weeks later by completing either a paper or online version of IBD-STAR, with the instruction that they were to complete this without consulting their parent for answers/opinions. Parents were instructed that they were allowed to help children read the items but not to help with answers.

2.7. Analysis

Demographic and disease characteristic information were collected from children and their parents and presented as descriptive data: mean (standard deviation (SD)), number (N), and percentage. The child scores achieved on IBD-STAR were assessed against independent variables to test their association with age, sex, diagnosis, study center, age at diagnosis, and time since diagnosis. The agreement level between child/parent dyads for IBD-STAR items were then assessed at the individual, category, and aggregate levels.

At the individual level, the agreement score between each dyad was calculated as the proportion of identical answers provided to all scored IBD-STAR items, calculated by dividing the number of congruent scores (identical answers to IBD-STAR items by child and parent) by the number of total possible identical answer pairs. The perfect individual agreement score is 1.0, and a score of 0.0 indicates agreement on no items. The ideal agreement level score is >0.75. A univariate general linear model determined whether any single independent variable could predict the degree of agreement between the scores.

At the category level, each IBD-STAR item and section was examined using contingency tables to determine the percentage of identical scoring, and parents/children scoring higher for IBD-STAR items for the whole population sample. Gwet’s AC1 coefficient was then calculated to measure the level of inter-rater reliability between child/parent dyads [27,28]. The levels of agreement for reliability coefficients are considered as follows: 0 to 0.2 is poor, 0.21 to 0.4 is fair, 0.41 to 0.6 is moderate, 0.61 to 0.8 is good, and 0.81 to 1.0 is very good [29].

At the aggregate level, the answers from both child and parent completion of IBD-STAR were assigned the appropriate score in accordance with the scale development and raw composite scores transformed to percentages. The significance of the score differences at the total scale level for children and parents was tested with paired t-tests and Pearson correlation (R), and the difference between percentage scores assessed against independent variables. The difference in percentage scores was further explored as a Bland–Altman plot to display the mean score of the child and parent scores against their difference, with data points expected to lie between 2 standard deviations from the mean [30]. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS for Windows 30.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York, NY, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Italian Cross-Cultural Adaptation

Three gastroenterology specialists reviewed each IBD-STAR item in English prior to translation, and all items were scored ≥0.97 thereby achieving an appropriate I-CVI for inclusion in the translated version. Each section scored ≥0.99 thereby achieving an appropriate S-CVI for inclusion (Appendix A). Minor edits were made to terminology to ensure equitable understanding according to the vernacular used in Italy; then, IBD-STAR was translated into Italian using a forward–backward process.

3.2. Demographics

A total of 54 child/parent dyads consented to participate in the study, and four were excluded due to incomplete IBD-STAR survey answers [missing answers to any IBD-STAR item], with a final cohort of 50 children: Christchurch = 13, Sydney = 14, Rome = 23. The mean age of the children was 14.5 years (SD 2.4), and 31 (62%) were female. Thirty-one (62%) of children had CD, and nineteen (38%) UC. The mean age at diagnosis was 10.3 years (SD 3.8), and mean time since diagnosis was 4.1 years (SD 3.6). The sex of the parent completing the study was collected in the Sydney and Christchurch cohorts, with 3 (11%) being male and 24 (89%) females.

The cohort mean % score of IBD-STAR for the children was 72% (SD 20), and parents 67% (SD 19). The children’s scores increased with age (R 0.47, p < 0.001, CI 1.8 to 6.0) but were not associated with any other independent variable (all p > 0.05): sex, diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, or study center.

3.3. Individual Agreement

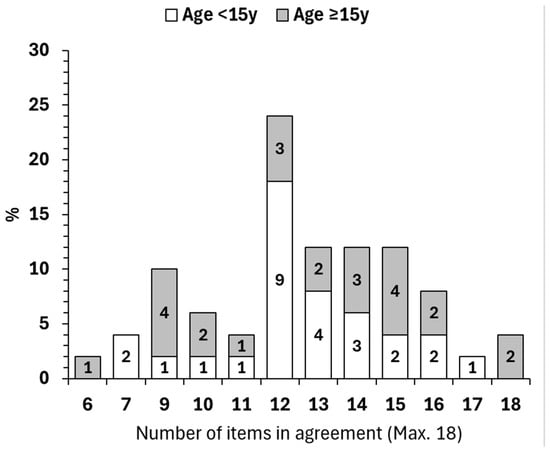

The mean proportional agreement for child/parent dyads was 0.70 (SD 0.15), indicating an acceptable level and equating to complete agreement on ≥12 IBD-STAR items. When the number of items in agreement were studied, the minimum number of items was six and maximum 18, and the number of items with highest frequency of agreement was 12 (Figure 1). There was no difference in the proportional agreement according to whether the child was aged 10–14 years (N = 26), or ≥15 years (N = 24) (χ2 12.4, p = 0.34), nor for any other independent variable (all p > 0.05): sex, linear age, diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, or study center. It was not possible to include parent sex as an independent variable as numbers were too small in the male sub-group.

Figure 1.

Individual agreement levels for each IBD-STAR item, divided into age groups of less than 15 years, or 15 years and over. Max = maximum.

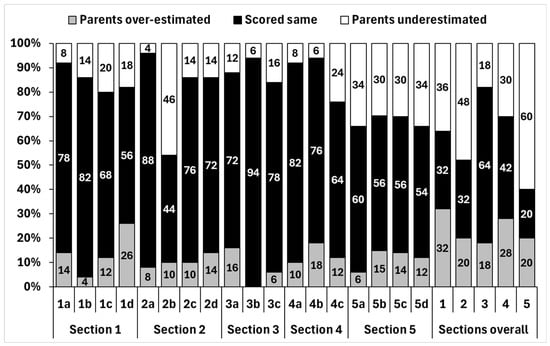

3.4. Category Agreement

When child/parent scores were compared for each IBD-STAR item agreement ranged from a low of 44% to a maximum of 94%, although only 8 (44%) of 18 items had an agreement level under 70% (Figure 2). Parents were likely to underestimate their child’s self-management skills more often than overestimate. The level of agreement for Section Three ‘My treatment’ was the highest overall at 64%, and lowest for Section Five ‘Managing my IBD’ at 20% agreement and 60% underestimation by the parent proxy report compared to child self-report (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Agreement level and parental under-/overestimation of each individual IBD-STAR item and for each section.

3.5. Inter-Rater Reliability

When the level of agreement for items and sections was assessed for inter-rater reliability, there was considerable variation. One item scored as ‘very good’ and ‘moderate’ was scored most frequently. The highest rated section was ‘My Treatment’ and the lowest rated section was ‘Managing my IBD’ (Table 1). The tool overall displaying ‘good’ inter-rater reliability. Those items rated as ‘poor’ were those that could be considered more subjective, such as the child keeping track of elements of their care, and less observable to a parent.

Table 1.

Inter-rater reliability scores and ratings for each IBD-STAR item, section, and for the tool overall.

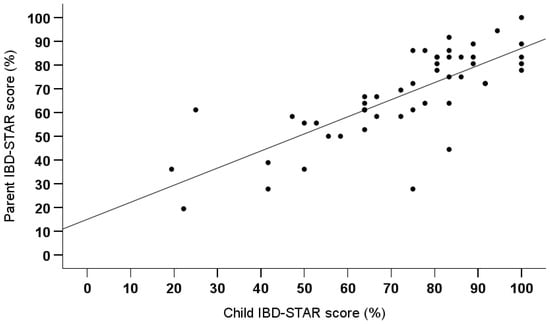

3.6. Aggregate Agreement

The overall scores for the child and parent completion of the tool were compared for correlation, and for % difference. The scores between each dyad were strongly correlated (R 0.774, p < 0.001, CI 0.63 to 0.87) (Figure 3), but the percentage scores differed (MD 5.3, p = 0.006, CI 1.6 to 9.0). The cohort mean % score of IBD-STAR for the children was 72% (SD 20), and parents 67% (SD 19). The score difference was not associated with any independent variable (all p > 0.05): sex, age group, linear age, diagnosis, age at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, or study center. It was not possible to include parent sex as an independent variable as numbers were too small in the male sub-group.

Figure 3.

Correlation between child and parent IBD-STAR percentage scores.

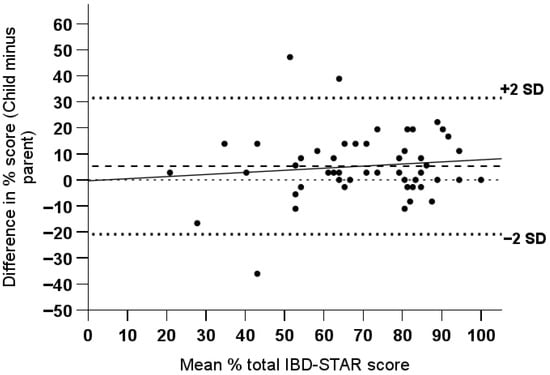

Overall, eight (16%) pairs achieved the same score, 12 (24%) parents scored higher thereby indicating overestimation of their child’s self-management skills, and 30 (60%) parents scored lower indicating underestimation. However, when assessed using a Bland–Altman plot to ascertain how many dyads were within two standard deviations of the cohort mean, only three pairs (6%) were outside the acceptable limit (Figure 4). The average mean difference in percentage score indicated low bias (MD 0.078, CI 0.02 to 0.13), and visually there was no heteroscedasticity (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Bland–Altman plot of the % score difference for child/parent dyads. Horizontal dashed line represents the cohort mean, and solid line the regression line of best fit.

3.7. Summary

To summarize, the child/parent dyads in this study demonstrated that they had acceptable agreement for items on IBD-STAR, with the majority in complete agreement on more than 12 of the 18 items. There was variability in whether parents under- or overestimated their child but there was a trend towards underestimation of self-management skills by parents (Table 2). This disparity was also shown when measuring inter-rater reliability with sections rated poor, moderate, or good inter-rater reliability (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of the section results of IBD-STAR for proportional agreement and inter-rater reliability.

4. Discussion

The current study assessed whether self-management skills self-reported by children with IBD were accurately reflected by parent proxy reports when both independently completed a self-management skills assessment tool (IBD-STAR). While there was some variation in reports, specifically for subjective IBD-STAR items, the level of individual agreement was considered acceptable, and inter-rater reliability for the tool overall between child/parent dyads was rated ‘good’. Scores were within two standard deviations of the cohort mean for 94% of the pairs, with the mean bias being small indicating the cohort overall had no directional bias in the between-dyad agreement levels, despite a trend towards underestimation.

While little is known about the agreement level between children with IBD and their parents relating to self-management skills, one previous study reported that parents underestimated this metric compared to their child [24], but overall agreement between parent/child reports are correlated [11,17], as in the current study. The current study provides further evidence to address the gap in knowledge for self-management skills and highlights that there may be better concordance for objective components than subjective, thereby promoting the child self-report being the gold-standard for such assessments. Greater agreement for objective self-management tasks is likely related to these being ‘observable’ by parents as opposed to subjective items that are more prone to parental perception. This finding is not unique to this study and has previously been reported among children self-reporting objective/subjective oncology-related symptoms [31] and children with chronic conditions, including IBD [32].

To account for disparities in child/parent assessments, several methods have been implemented. For parent proxy reported medication adherence estimates, a correction factor has been developed to allow for parental overestimation in order to obtain a more accurate estimate [16]. In addition, a number of parent report versions of pediatric assessment tools have been validated to enable optimal proxy reporting for metrics such as health-related quality of life, transition skills, and self-efficacy [17,19,33].

Disparities in child/parent dyads of self-management skills may negatively influence the development of child health autonomy due to parental perception that their child is not ready to take responsibility for disease management tasks [8,17]. Discrepancies between child/parental reports may be related to the perception of child vulnerability, parental stress and psychological well-being, and the uncertainty of the IBD trajectory, which may bias parents’ cognition about their child’s disease and management [34,35,36]. The current study demonstrates that parents may not always assess their child’s self-management skills accurately, which may also be a reflection of their concern for their child responsibly managing their own health tasks during the process of developing health autonomy [22,37]. It may also reflect children reporting a perception of their self-management skills as opposed to their demonstrated skills. The differences reported between child/parent dyads in the current study have a practical implication for clinical encounters, and this should be acknowledged during discussions with children and adolescents, in particular as they approach transition to adult services. However, tools such as IBD-STAR may be used to assess self-management skills reports and highlight such important disparities so that they may be addressed with the child and parent together.

The facilitation of self-management skills development tools, such as goal setting and digital interventions [38,39], may enable parents to observe their child’s progress for specific tasks and facilitate greater understanding and visibility between child/parent dyads of the process of incremental development of health autonomy. Using IBD-STAR, progress may be monitored as incremental positive changes to answers provided for individual items or categories that eventuate in health autonomy for individual tasks or overarching topics. This can also be checked by clinicians/parents to ensure that skill development is complete and can then be reinforced during subsequent visits, in particular for those children who are in the process of transition to adults services where there is a high expectation of autonomy and self-management [17,40].

Future research may incorporate a practical element of assessing self-management skills to ensure concordance between the child/adolescent self-reported ability, and their actual competence at specific skills. A component of cross-validation between children’s reported abilities and parental responses were carried out in the initial IBD-STAR development and validation study [24]. However, an additional practical element may further define whether parents are indeed underestimating their child’s self-management skills or children are overestimating their own autonomy. Subsequent research will also include a component of disease activity assessment to determine whether inflammation or symptom escalation is associated with self-management skills. This association has been reported previously for children with IBD whereby increased disease activity was negatively associated with self-management, specifically relating to adherence [41,42,43,44]. Among adults with chronic illness, it has been reported that health status, including comorbidities, condition severity, symptoms, and treatment side effects, negatively influence their ability to carry out self-management tasks [45].

Assessment of external validity of assessment tools, such as IBD-STAR between centers, countries, and languages, is important. This relates to ascertaining whether causal relationships can be generalized between measures, people, settings, and time [46,47]. In the context of healthcare, testing the generalizability of assessment tools may be carried out to facilitate standardized care, provide equitable access to resources for children with IBD, and facilitate comparisons between centers. The current study implemented the same study in three international centers, including an additional translation component, and in showing no difference between study centers for individual, category, or aggregate agreement, one can assume generalizability. While IBD-STAR is not scored as correct/incorrect answers, the current study confirms equitable understanding of items between centers and languages [47].

4.1. Limitations

The study did not collect the sex of caregivers in all centers, thus limiting analysis within this independent variable. There is evidence that parental characteristics, such as sex, level of education, and health literacy, may influence the level of agreement between a parent and their child. In future studies, these variables will be important to include to identify whether targeted education for specific groups may be beneficial. The overall cohort size was small, introducing the possibility of type II errors that may underestimate the effect size thereby underreporting the importance of child/parent dyad differences, and limits sub-group analyses. Study recruitment was affected by COVID-19 in two centers and the proposed sample sizes were not achieved. This has limited our ability to identify more nuanced differences within our study population, and limited generalizability to the wider pediatric IBD population. In addition, the studies having been carried out pre-, peri- and post-COVID-19 at the different centers may have introduced temporal change in line with increased family time that may have enhanced parental awareness of their child’s self-management skills. However, no differences were seen by center during sub-group analysis. The cross-cultural adaptation process of translation into Italian would have benefited from a pilot test or cognitive debriefing among the target audience and will be included in future translation studies. In asking children to complete IBD-STAR two weeks after their parent there is the potential for bias due to the possibility of learning new skills in the interim period. However, we considered that completing IBD-STAR at the same time may also introduce the possibility of cross-contamination if children/parents managed to discuss items, thus influencing agreement levels.

4.2. Strengths

In carrying out the current study in three international centers, the generalizability of IBD-STAR was able to be established, as well as the implementation of a translation protocol for future work. In utilizing IBD-STAR among child/parent dyads, direct comparisons could be made for individual items, thereby highlighting that scores differed between objective/subjectively measured items. Future work could build on IBD-STAR to add a practical component that could enable direct measures of specific IBD-STAR skills.

5. Conclusions

The incremental development of practical self-management skills is an important component in the lead-up to transition from pediatric to adult services for children with IBD. While this process was previously thought to be appropriate for older children and adolescents, the development of self-management skills also should be considered as an important attribute for younger children. Implementing self-management skill development at an earlier age will ensure ample time for these to progress from a state of having no ability to perform tasks independently, leading on to having health autonomy across multiple categories. Assessment tools such as IBD-STAR play an important role in monitoring incremental change. In assessing child self-reported skills, in contrast to parent-proxy reports, this will promote the importance of the child as being the gold standard for information relating to their condition and help minimize misestimates from parents/caregivers. Future research may see additional practical components added to IBD-STAR that can enable visualization of important skills that may improve transparency between child/parent dyads.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization A.V.-R. and A.S.D.; Methodology A.V.-R. and A.S.D.; Validation A.V.-R., F.M., M.A., N.B., D.L. and A.S.D.; Formal analysis A.V.-R.; Investigation A.V.-R., F.M., M.A., N.B., D.L. and A.S.D.; Resources A.V.-R., F.M., M.A., N.B., D.L. and A.S.D.; Writing—original draft A.V.-R.; Writing—Review and editing A.V.-R., F.M., M.A., N.B., D.L. and A.S.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional/Ethics Review Boards as follows: University of Otago Human Ethics Committee (Health) [H16/116], Sydney Children’s Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee [2020/ETH00562], and Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University of Rome.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest relating to this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Individual item and section content validity indices for IBD-STAR items prior to undergoing the translation process.

Table A1.

Individual item and section content validity indices for IBD-STAR items prior to undergoing the translation process.

| Item | I-CVI Cultural Relevance | I-CVI Language and Comprehension | Section | S-CVI Cultural Relevance | S-CVI Language and Comprehension |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 1b | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1c | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 1d | 0.97 | 0.97 | |||

| 2a | 0.97 | 0.97 | 2 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 2b | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 2c | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 2d | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 3a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 3 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| 3b | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 3c | 1.00 | 0.97 | |||

| 4a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| 4b | 0.97 | 0.97 | |||

| 4c | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 5a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 5 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 5b | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 5c | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 5d | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 6a | 1.00 | 1.00 | 6 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| 6b | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 6c | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 6d | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| OVERALL | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 0.99 |

I-CVI = item content validity index, S-CVI = section content validity index.

References

- Kuenzig, M.E.; Fung, S.G.; Marderfeld, L.; Mak, J.W.; Kaplan, G.G.; Ng, S.C.; Wilson, D.C.; Cameron, F.; Henderson, P.; Kotze, P.G.; et al. Twenty-first Century Trends in the Global Epidemiology of Pediatric-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 1147–1159.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, C.; Bartek, J.; Wewer, V.; Vind, I.; Munkholm, P.; Groen, R.; Paerregaard, A. Differences in phenotype and disease course in adult and paediatric inflammatory bowel disease—A population-based study. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2011, 34, 1217–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Granot, M.; Kopylov, U.; Loberman-Nachum, N.; Krauthammer, A.; Abaitbol, C.M.; Ben-Horin, S.; Weiss, B.; Haberman, Y. Differences in disease characteristics and treatment exposures between paediatric and adult-onset inflammatory bowel disease using a registry-based cohort. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 60, 1435–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackner, M.L.; Greenley, N.R.; Szigethy, A.E.; Herzer, A.M.; Deer, A.K.; Hommel, A.K. Psychosocial Issues in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Report of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2013, 56, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modi, A.C.; Pai, A.L.; Hommel, K.A.; Hood, K.K.; Cortina, S.; Hilliard, M.E.; Guilfoyle, S.M.; Gray, W.N.; Drotar, D. Pediatric self-management: A framework for research, practice, and policy. Pediatrics 2012, 129, e473–e485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Gearry, R.; Day, A. Overview of self-management skills and associated assessment tools for children with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastrointest. Disord. 2021, 3, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beacham, B.L.; Deatrick, J.A. Health Care Autonomy in Children with Chronic Conditions: Implications for Self-Care and Family Management. Nurs. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 48, 305–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, L.A.; Tuchman, L.K.; Hobbie, W.L.; Ginsberg, J.P. A social-ecological model of readiness for transition to adult-oriented care for adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2011, 37, 883–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantinidis, D.D.; O’Brien, C.L.; Hebbard, G.; Kanaan, R.; Castle, D.J. Healthcare transition and inflammatory bowel disease: The challenges experienced by young adults after transfer from paediatric to adult health services. Psychol. Health Med. 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Rouse, E.; Bowcock, N.L.; Lemberg, D.A.; Day, A.S. Agreement Level of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Symptom Reports between Children and Their Parents. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Nutr. 2023, 26, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loonen, H.J.; Derkx, B.H.F.; Koopman, H.M.; Heymans, H.S.A. Are parents able to rate the symptoms and quality of life of their offspring with IBD? Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2002, 8, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawton, R.C.; Colman, R.J.; Rothbaum, R.; LaRose-Wicks, M.; Washburn, J. “But I’m Feeling Fine!” A Comparison of Parent and Child Symptom-Report Among Pediatric Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 148, S–379–S–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcovitch, L.; Focht, G.; Horesh, A.; Shosberger, A.; Hyams, J.; Bousvaros, A.; Hale, A.E.; Baldassano, R.; Otley, A.; Mack, D.R.; et al. Agreement on Symptoms Between Children With Ulcerative Colitis and Their Caregivers: Towards Developing the TUMMY-UC. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2021; publish ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsous, M.M.; Hawwa, A.F.; Imrie, C.; Szabo, A.; Alefishat, E.; Farha, R.A.; Rwalah, M.; Horne, R.; McElnay, J.C. Adherence to Azathioprine/6-Mercaptopurine in Children and Adolescents with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Multimethod Study. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 2020, 9562192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.P.; Pai, A.L.H.; Gray, W.N.; Denson, L.A.; Hommel, K.A. Development and Reliability of a Correction Factor for Family-Reported Medication Adherence: Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease as an Exemplar. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2013, 38, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazareth, M.; Hart, L.; Ferris, M.; Rak, E.; Hooper, S.; van Tilburg, M.A.L. A Parental Report of Youth Transition Readiness: The Parent STARx Questionnaire (STARx-P) and Re-evaluation of the STARx Child Report. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanania, J.W.; George, J.E.; Rizzo, C.; Manjourides, J.; Goldstein, L. Agreement between child self-report and parent-proxy report for functioning in pediatric chronic pain. J. Patient-Rep. Outcomes 2024, 8, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, G.K.; Stolz, M.G.; Shih, S.; Blount, R.; Otley, A.; Talmadge, C.; Grant, A.; Reed, B. Parent IMPACT-III: Development and Validation of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease-specific Health-related Quality-of-life Measure. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 70, 205–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgel, S.; Norman, G.; Issenman, R.M.; Gold, N.; Irvine, E.J. Health-related quality of life in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A comparison of parent and child reports. Gastroenterology 1998, 114, A977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, R.J.; Grant, R.A.; Otley, R.A.; Orsi, R.M.; Macintyre, R.B.; Gauvry, R.S.; Lifschitz, R.C. Do Parents and Children Agree? Quality-of-Life Assessment of Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Their Parents. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2014, 58, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirinen, T.; Kolho, K.L.; Simola, P.; Ashorn, M.; Aronen, E.T. Parent–adolescent agreement on psychosocial symptoms and somatic complaints among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Acta Paediatr. 2012, 101, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Rouse, E.; Day, A. Systematic review of self-management assessment tools for children with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. Rep. 2021, 2, e075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Frampton, C.; Gearry, R.; Day, A. Development and validation of a self-management skills assessment tool for children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2020, 72, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernon-Roberts, A.; Musto, F.; Aloi, M.; Day, A.S. Italian Cross-Cultural Adaptation of a Knowledge Assessment Tool (IBD-KID2) for Children with Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastrointest. Disord. 2023, 5, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polit, D.; Beck, C.; Owen, S. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Res. Nurs. Health 2007, 30, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K.L. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring The Extent of Agreement Among Raters, 4th ed.; Advanced Analytics; LLC: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Wongpakaran, N.; Wongpakaran, T.; Wedding, D.; Gwet, K.L. A comparison of Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: A study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, D.G. Practical Statistics for Medical Research, 1st ed.; Chapman and Hall: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2010, 47, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, L.; McFatrich, M.; Lucas, N.; Walker, J.; Withycombe, J.; Hinds, P.; Sung, L.; Tomlinson, D.; Freyer, D.; Mack, J.; et al. Child and adolescent self-report symptom measurement in pediatric oncology research: A systematic literature review. Qual. Life Res. 2018, 27, 291–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, A.M.; Hayen, A.; Quine, S.; Scheinberg, A.; Craig, J.C. A comparison of doctors’, parents’ and children’s reports of health states and health-related quality of life in children with chronic conditions. Child Care Health Dev. 2012, 38, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsen, K.; Gordon, J.; Haddad, N.; Phan, B.; Dubinksy, M.; Keefer, L. Development of the Parent Version of the IBD Self-efficacy Scale for Adolescents and Young Adults with Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2017, 23, S72–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushman, G.; Shih, S.; Reed, B. Parent and Family Functioning in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Children 2020, 7, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, C.M.; Gamwell, K.L.; Baudino, M.N.; Perez, M.N.; Delozier, A.M.; Sharkey, C.M.; Grant, D.M.; Grunow, J.E.; Jacobs, N.J.; Tung, J.; et al. Youth and Parent Illness Appraisals and Adjustment in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 2019, 31, 777–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jesus, H.; Ooms, A.; Norton, C.; Dibley, L.; Croft, N. Development of self-management in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: A qualitative exploration. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 2019, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, T.; Sherman, E.; Mah, J.K.; Blackman, M.; Latter, J.; Mohammed, I.; Slick, D.; Thornton, N. Measurement of medical self-management and transition readiness among Canadian adolescents with special health care needs. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Health 2010, 3, 527–535. [Google Scholar]

- Hommel, K.A.; Noser, A.E.; Plevinsky, J.; Gamwell, K.; Denson, L.A. Pilot and feasibility of the SMART IBD mobile app to improve self-management in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2024, 78, 1273–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hommel, K.A.; Ramsey, R.R.; Gray, W.N.; Denson, L.A. Digital Therapeutic Self-Management Intervention in Adolescents With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 76, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hait, E.J.; Barendse, R.M.; Arnold, J.H.; Valim, C.; Sands, B.E.; Korzenik, J.R.; Fishman, L.N. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: A survey of adult gastroenterologists. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2009, 48, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenley, N.R.; Stephens, N.M.; Doughty, N.A.; Raboin, N.T.; Kugathasan, N.S. Barriers to adherence among adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 36–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingerski, L.M.; Baldassano, R.N.; Denson, L.A.; Hommel, K.A. Barriers to oral medication adherence for adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2010, 35, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva-Hemker, M.M.; Abadom, V.; Cuffari, C.; Thompson, R.E. Nonadherence with thiopurine immunomodulator and mesalamine medications in children with Crohn disease. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2007, 44, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schurman, J.V.; Cushing, C.C.; Carpenter, E.; Christenson, K. Volitional and Accidental Nonadherence to Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease Treatment Plans: Initial Investigation of Associations with Quality of Life and Disease Activity. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2011, 36, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman-Green, D.; Jaser, S.S.; Park, C.; Whittemore, R. A metasynthesis of factors affecting self-management of chronic illness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 1469–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, H.; Galiani, S. Assessing external validity. Res. Econ. 2021, 75, 274–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steckler, A.; McLeroy, K. The Importance of External Validity. Am. J. Public Health 2008, 98, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.