Abstract

Pigment gallstones represent a heterogeneous group of concretions, classically divided into black and brown types, whose morphology and microstructure offer critical clues about their underlying pathogenesis. Gallstone formation (lithogenesis) is a complex process triggered when the physicochemical equilibrium of bile is disrupted. Background/Objectives: The spicules observed on the surface of certain black pigment gallstones have traditionally been attributed to the branching capacity of cross-linked bilirubin polymers. However, a growing body of experimental and spectroscopic evidence suggests that inorganic calcium salts, particularly calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate, play a central role in the formation of the distinctive spiculated or “coral-like” architecture. Materials and Methods: In our study, we examined a case series of 1350 consecutive patients with gallstone disease, identifying 81 patients who presented with solitary black pigment stones. We systematically explored the association between high calcium content, specifically calcium carbonate, and the occurrence of spiculated morphology. Our analyses demonstrated a robust correlation between an elevated concentration of calcium carbonate and the presence of well-defined spicules. Results: These results support the hypothesis that mineral elements, rather than organic bilirubin polymers, act as crucial determinants of the peculiar crystalline structure observed in a significant subset of pigment stones. Spiculated stones, due to their small size and sharp projections, have a higher likelihood of migrating, increasing the risk of potentially life-threatening complications, such as acute cholangitis and gallstone pancreatitis. Conclusions: Our findings, consistent with recent advanced crystallographic analyses, underscore the importance of considering mineral composition in the diagnosis and management of cholelithiasis. Understanding the factors that drive calcium carbonate precipitation is essential for developing new preventive and therapeutic strategies, aiming to modulate bile chemistry and reduce the risk of calcium-driven lithogenesis.

1. Introduction

Gallstone disease is one of the most prevalent digestive disorders worldwide, with a pathogenesis driven by complex genetic, metabolic, and geographical factors [1,2]. Currently classified within the spectrum of hepatolithiasis [3], it is subdivided into intrahepatic and extrahepatic forms [4]. While many cases remain asymptomatic, the chronic presence of stones invariably induces a persistent inflammatory state within the gallbladder [5]. This inflammatory cascade, triggered by the release of chemokines, angiogenic factors, and cytokines from macrophages and lymphocytes, can lead to severe complications such as acute cholecystitis, hydrops, perforation, or even malignant transformation [6,7].

Gallstones are categorized into cholesterol, pigment stones (black and brown) and mixed stones, according to their predominant chemical composition [8,9]. Pigment stones, though more frequent in Asian populations, account for up to 25% of cases in Western countries and are associated with significant clinical outcomes, including biliary colic and pancreatitis [2,4] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Gallbladder filled with numerous small stones.

Among these, black pigment stones typically develop in conditions of increased bilirubin load, such as chronic hemolysis or cirrhosis [7,10]. They are composed mainly of calcium bilirubinate polymers crosslinked by divalent cations (particularly calcium) [1]. A distinctive, yet inconsistent, morphological feature of these stones is the presence of spicules [11,12] (Figure 2). While traditionally attributed to the branching nature of bilirubin polymers, the absence of spicules in many samples suggests that other factors must contribute to this specific architecture. Clinically, the small size and irregular shape of these stones facilitate their migration into the bile ducts, leading to either intrahepatic obstruction or pancreatitis due to impaction at the sphincter of Oddi [9] (Figure 3).

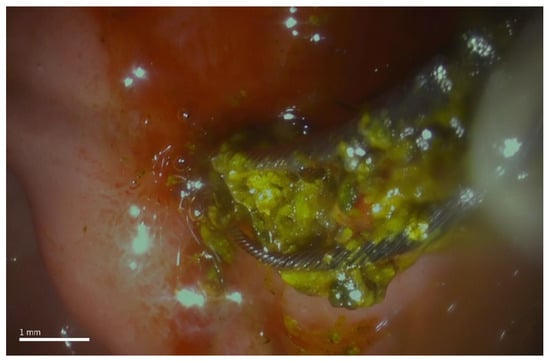

Figure 2.

Gallbladder with black pigment stones, characterized by their distinctive spicules.

Figure 3.

Extraction of a sharp-edged stone during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in a patient who had been admitted for edematous pancreatitis. The absence of a fully black finish is attributed to the lack of complete oxidation.

In contrast, brown pigment stones are linked to bile stasis and infection, typically impacting the infundibulum. Their composition—rich in calcium soaps of fatty acids and cholesterol—rarely exhibits spiculated surfaces (Figure 4). Recent research emphasizes that the polymorphic forms of calcium carbonate (calcite, vaterite, and aragonite) and calcium phosphate are critical in determining both the morphology and radiopacity of these stones [2,13,14,15]. Furthermore, calcium deposition is a key factor in the development of porcelain gallbladder, a condition predisposing to carcinoma through unrecognized chronic inflammation [16].

Figure 4.

Gallbladder with brown pigment stones and their “not spiculated” morphology.

Advanced spectroscopic analyses have confirmed that bilirubin, calcium salts, and mucin glycoproteins form the structural scaffold of these stones, though the exact contribution of each element to stone architecture remains a subject of investigation [17,18,19]. This study aimed to explore the relationship between spiculated morphology and calcium content in pigment stones, integrating clinical data with biochemical and spectroscopic evidence to further define gallstone heterogeneity.

2. Results

2.1. Study Cohort and Demographic Data

A total of 1350 consecutive patients undergoing cholecystectomy were analyzed. The cohort’s age ranged from 18 to 91 years, with a mean age of 63.5 years. The gender distribution showed a slight male predominance (55% male, 45% female). The most prevalent comorbidities among the subjects were hypertension and ischemic heart disease. Additionally, 10 patients (0.74%) had a documented history of malignancy, including colorectal cancer (n = 4), gastric cancer (n = 3), and single cases of renal cell carcinoma, ileal neuroendocrine tumor (NET), and appendiceal carcinoma.

2.2. Surgical and Clinical Outcomes

Approximately 90% of cholecystectomies were successfully completed via a laparoscopic approach. Operative times ranged from 30 to 120 min, with longer durations primarily associated with the presence of pericholecystic inflammation or the need for extensive adhesiolysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Profile of the Study Cohort (N = 1350).

Clinical indications for surgery included emergency admissions (ED), elective cases, and transfers from the gastroenterology department following stabilization for edematous pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis, or jaundice.

2.3. Black Pigment Stone Analysis

Among the total cohort, 81 patients (6.0%) were identified as having black pigment stones (38 men, 43 women; mean age 56 ± 1 years). IR spectroscopy confirmed characteristic bilirubin absorption bands in all these samples, validating their classification.

Morphological assessment revealed two distinct subtypes:

- Spiculated stones: 32 samples (39.5%) displayed superficial spicules.

- Non-spiculated (smooth) stones: 49 samples (60.5%) were classified as smooth.

Regarding stone size, mean dimensions were comparable between the two subtypes, with no statistically significant difference observed (4.2 ± 1.8 mm for spiculated vs. 3.9 ± 1.5 mm for non-spiculated).

2.4. Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Content and Mineralogy

Analysis of CaCO3 content revealed marked differences correlated with stone morphology. Spiculated stones exhibited significantly higher calcium concentrations: levels exceeding 10–15% were found in 71.9% (n = 23) of spiculated stones, compared with only 36.7% (n = 18) of smooth stones. This difference was highly statistically significant (χ2 = 8.2; p < 0.005).

In addition to black pigment stones, five patients (one man, four women; mean age 51 years) presented with mixed “coral-like” stones. These stones were characterized by large, hard spicules and consistently contained more than 10% CaCO3. XRD analysis of these samples identified three polymorphic phases of calcium carbonate—calcite, vaterite, and aragonite—indicating a complex and highly organized mineral structure that accounts for their hard, irregular appearance (Table 2).

Table 2.

Morphological and Compositional Analysis of Pigment Gallstones.

3. Discussion

Digestion, nutrient absorption, and the elimination of insoluble products of heme catabolism rely heavily on the coordinated secretion of bile by the liver. Bile, a complex fluid composed of bile acids, cholesterol, phospholipids, bilirubin, and various inorganic ions such as calcium and magnesium, plays a central role not only in the emulsification of dietary fats, but also in maintaining a delicate physical-chemical balance and the bile composition can variate with age and sex [20]. When this equilibrium is disrupted, particularly through changes in bile composition or flow, conditions may favor the formation of gallstones—a process collectively termed lithogenesis [21].

Among the various types of gallstones, black pigment stones represent a distinct biochemical and morphological entity. These stones arise primarily in the setting of altered heme metabolism, chronic hemolysis, or inefficient enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin [22], leading to an increased concentration of unconjugated bilirubin in bile. Once in the biliary tract, unconjugated bilirubin readily forms calcium bilirubinate salts through ionic interactions with divalent calcium ions. The resulting complexes are poorly soluble and tend to precipitate, initiating nucleation and subsequent stone growth. Calcium, therefore, emerges as a key player in the pathogenesis of pigment stones—not only by facilitating the precipitation of bilirubinate but also by participating in the formation of other inorganic salts, particularly calcium carbonate.

Since the 1990s, a growing body of experimental and spectroscopic evidence highlighted the pivotal role of bile acids in modulating calcium activity and precipitation dynamics [23]. Notably, bilirubin molecules contain reactive carboxyl and lactam groups, which can dissociate under physiological conditions and form ionic bonds with calcium. However, the coordination chemistry is highly variable: bilirubin can exist in mono- or dianionic forms depending on pH, and calcium may bind in 1:1 or 1:2 molar ratios. Additionally, the presence of other organic molecules—such as glycoproteins, mucins, or bacterial β-glucuronidases—and inorganic ions like phosphate and magnesium further complicates the stoichiometry and mineral phase composition. This chemical complexity is reflected in the morphological diversity of pigment stones, which may appear smooth, laminated, granular, or notably spiculated.

Our findings demonstrated a robust correlation between high calcium carbonate content and the occurrence of spicules—thin, radiating projections that give stones a characteristic “coral-like” appearance. Bilirubin polymers are essential for the initial matrix formation and pigmentation of black stones, but they don’t explain the spiculated architecture observed in a significant subset of samples. In fact, we observed that some stones with relatively low bilirubin content still exhibited well-defined spicules, suggesting that calcium carbonate is not merely a passive component but may act as a morphological driver during stone maturation. The clinical implications of this architecture are significant. Spiculated pigment stones, owing to their small size and sharp projections, have a higher likelihood of entering and obstructing the common bile duct or the sphincter of Oddi. Such obstructions can precipitate a cascade of pathological events, including acute cholangitis and gallstone pancreatitis. The mechanical irritation of the ductal epithelium by spicules may promote fibrosis or strictures over time, further compromising biliary drainage and increasing the risk of recurrent episodes.

A key takeaway from our study concerns dimensional variation and its relationship with morphology. Although mean dimensions may not show extreme differences between the two subtypes (e.g., spiculated stones mean 3.9 ± 1.5 mm vs. non spiculated stones mean 4.2 ± 1.8 mm, p = 0.57), the spiculated morphology itself represents an additional dimension of clinical risk. The irregular geometry, rather than overall volume, may increase the likelihood of local trauma during stone migration. Therefore, the results suggest that morphological characterization (spiculated vs. smooth) should complement dimensional assessment alone.

These observations are supported by several key studies. Ostrow and Bogren [4,24] were among the first to characterize the polymorphic nature of calcium carbonate in gallstones, identifying aragonite and calcite forms. More recently, Taylor et al. [7] demonstrated that calcium carbonate crystallization is not confined to pigment stones; it can also occur within cholesterol stones, often contributing to mixed-type gallstone formation. Advanced imaging and spectroscopy techniques— including FTIR, XRD, scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy (LIBS)—have enabled high-resolution analyses of gallstone microstructure. These methods reveal complex layering patterns, with alternating strata of bilirubin polymers and mineral phases, often incorporating calcium, magnesium, phosphate, and even trace elements like iron and zinc [15,17,18,19]. Geographic and demographic studies further underscore the role of calcium in pigment stone morphology. Research conducted in East and Southeast Asia, regions with higher prevalence of pigment stones, consistently reports greater proportions of calcium bilirubinate and calcium carbonate, as well as higher rates of spiculated stones [10,11,12,13]. Dietary factors, genetic polymorphisms affecting bilirubin conjugation (e.g., UGT1A1 variants), and regional differences in intestinal microbiota [25] may all contribute to these trends. Taken together, data support a dual-pathogenesis model for black pigment stones. In this model, bilirubin polymers constitute the biochemical scaffold that initiates stone formation, while inorganic calcium salts, particularly calcium carbonate, influence the ultimate crystalline morphology—including the formation of spicules.

This differentiation enhances the understanding of gallstone heterogeneity and may guide future approaches to prevention and therapy. Nonetheless, our study has several limitations. The total number of spiculated pigment stones analyzed was modest, and while the association with calcium carbonate is compelling, we did not systematically quantify other mineral components such as phosphate, oxalate, or magnesium salts, which may also contribute to stone structure. Additionally, the cross-sectional design precludes causal inference. Longitudinal and mechanistic studies, ideally involving bile composition analysis, animal models, and real-time imaging of crystal formation, are needed to further elucidate the factors driving spiculated morphogenesis.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Patient Selection

We conducted a retrospective analysis of gallstone samples from 1350 consecutive patients who underwent cholecystectomy at a single tertiary center. The study population comprised three primary groups: (1) emergency department (ED) admissions, all of whom underwent common bile duct assessment via cholangiography or endoscopic ultrasound; (2) patients scheduled for elective surgery; and (3) patients transferred from the gastroenterology department following stabilization for edematous pancreatitis, choledocholithiasis, or jaundice.

4.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion was limited to patients over 18 years of age undergoing cholecystectomy for biliary disease. Exclusion criteria were applied to patients with necrotic–hemorrhagic pancreatitis (as bile duct clearance via ERCP had been performed prior to surgery), Mediterranean anemia, and Rett syndrome.

4.3. Surgical Approach

Cholecystectomies were performed using either a laparoscopic approach (approximately 90%) or an open technique, depending on clinical indications or intraoperative findings such as extensive adhesions or severe pericholecystic inflammation. Operative times typically ranged from 30 to 120 min.

4.4. Macroscopic and Compositional Analysis

All recovered gallstones underwent initial macroscopic examination by an experienced specialist to assess size, shape, color, surface texture, and consistency. To achieve definitive classification, samples were analyzed using the following advanced techniques:

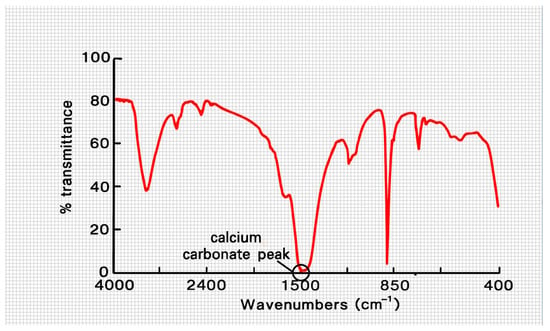

- Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR): Used to identify molecular peaks associated with bilirubinates, cholesterol, and calcium salts, allowing for the precise differentiation of organic and inorganic components (Figure 5).

Figure 5. FTIR of predominately calcium carbonate debris pellet.

Figure 5. FTIR of predominately calcium carbonate debris pellet. - X-ray Diffraction (XRD): Employed to confirm the crystalline structure of the stone components.

Black pigment stones were identified based on characteristic macroscopic appearance, the presence of diagnostic bilirubin absorption peaks, and the absence of signals attributable to crystallized cholesterol. Calcium content was quantified as a weight percentage, with calcium carbonate > 10% classified as elevated. Brown (bacterial) and yellow (cholesterol) stones were identified and subsequently excluded from further analysis to maintain the study’s focus on black pigment stone architecture.

4.5. Imaging and Visual Enhancement

Images of operative specimens and gallstone samples were captured during the study period. To ensure maximum clarity for publication, these images underwent a visual optimization process using Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) technologies. This process was utilized exclusively for non-manipulative post-production enhancement to improve resolution and lighting without altering the underlying clinical or morphological data.

5. Conclusions

Although only a minority of black pigment stones exhibit spiculated morphology, their occurrence is strongly and consistently associated with elevated calcium carbonate content. These “coral-like” stones, while often poor in bilirubin, are rich in inorganic calcium salts, suggesting that mineral components—rather than organic bilirubin polymers—play the predominant role in shaping their crystalline architecture. From a clinical standpoint, the morphology and size of gallstones have direct implications for patient outcomes. Spiculated stones, owing to their diminutive size and sharp projections, are more likely to migrate into the common bile duct and obstruct the sphincter of Oddi, predisposing patients to potentially life-threatening complications such as cholangitis and acute pancreatitis. The mechanical trauma inflicted by these stones may also induce lasting structural changes in the ductal epithelium, including fibrosis and sphincter dysfunction.

Our findings underscore calcium carbonate not merely as a component of pigment stones but as a key determinant of their morphology and clinical behavior. These results highlight the importance of considering mineral composition—particularly calcium carbonate—in the diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic paradigms of gallstone disease. Future research should aim to clarify the biochemical triggers of calcium carbonate precipitation, explore the role of dietary and microbiome factors, and investigate pharmacological strategies to modulate bile chemistry and reduce the risk of calcium-driven lithogenesis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.C., L.C. and M.Z.; data curation, N.C. and E.K.; formal analysis, G.E.P. and D.M.; investigation, L.C. and M.Z.; methodology, G.E.P. and L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, N.C. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, G.E.P., E.K. and D.M.; supervision, N.C., M.Z. and D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved on 25 March 2022 by the Institutional Review Board (AOUS Siena, A.DS.MD.139a).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available due to technical limitations. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini 2.5 Flash for image refinement to improve clarity and focus for presentation and did not alter the diagnostic or pathological features of the specimens depicted. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ERCP | Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| IR | Infrared Spectroscopy |

| LIBS | Laser-Induced Breakdown Spectroscopy |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| XRD | X-ray Diffraction |

References

- Vítek, L.; Carey, M.C. New Pathophysiological Concepts Underlying Pathogenesis of Pigment Gallstones. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2012, 36, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portincasa, P.; Di Ciaula, A.; Bonfrate, L.; Stella, A.; Garruti, G.; Lamont, J.T. Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Gallstone Disease: Expecting More from Critical Care Manifestations. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2023, 18, 1897–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calomino, N.; Carbone, L.; Kelmendi, E.; Piccioni, S.A.; Poto, G.E.; Bagnacci, G.; Resca, L.; Guarracino, A.; Tripodi, S.; Barbato, B.; et al. Western Experience of Hepatolithiasis: Clinical Insights from a Case Series in a Tertiary Center. Medicina 2025, 61, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogren, H.G. The Polymorphs of Calcium Carbonate in Human Gall Stones. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Investig. 1983, 43, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulrahman, R.; Hashem, J.; Walsh, T.N. A Review of Acute Cholecystitis. JAMA 2022, 328, 76–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadzhiev, D.N.; Tagiev, É.G.; Guseĭnaliev, A.G.; Gadzhiev, N.D.; Talyshinskaia, L.R. The Cytokine Profile in the Patients with Acute Calculous Cholecystitis and Correction of Its Disorders. Klin. Khir. 2013, 17–19. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, D.R.; Crowther, R.S.; Cozart, J.C.; Sharrock, P.; Wu, J.; Soloway, R.D. Calcium Carbonate in Cholesterol Gallstones: Polymorphism, Distribution, and Hypotheses about Pathogenesis. Hepatology 1995, 22, 488–496. [Google Scholar]

- Shoda, J.; Inada, Y.; Osuga, T. Molecular Pathogenesis of Hepatolithiasis—A Type of Low Phospholipid-Associated Cholelithiasis. Front. Biosci. (Landmark Ed.) 2006, 11, 669–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njeze, G. Gallstones. Niger. J. Surg. 2013, 19, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerakoon, H.; Navaratne, A.; Ranasinghe, S.; Sivakanesan, R.; Galketiya, K.B.; Rosairo, S. Chemical Characterization of Gallstones: An Approach to Explore the Aetiopathogenesis of Gallstone Disease in Sri Lanka. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ram Attri, M.; Ahmad Kumar, I.; Mohi Ud Din, F.; Hussain Raina, A.; Attri, A. Pathophysiology of Gallstones. In Gallstones—Review and Recent Progress; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichugina, A.A.; Tsyro, L.V.; Unger, F.G. IR Spectroscopy and X-Ray Phase Analysis of the Chemical Composition of Gallstones. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2018, 84, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramana Ramya, J.; Thanigai Arul, K.; Epple, M.; Giebel, U.; Guendel-Graber, J.; Jayanthi, V.; Sharma, M.; Rela, M.; Narayana Kalkura, S. Chemical and Structural Analysis of Gallstones from the Indian Subcontinent. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 78, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gazali, Z.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, T.; Kumar, R.; Tarai, A.K.; Rai, P.K.; Gundawar, M.K.; Rai, A.K. Effect of Mineral Elements on the Formation of Gallbladder Stones Using Spectroscopic Techniques. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2023, 415, 6279–6289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reshetnyak, V.I. Concept of the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Cholelithiasis. World J. Hepatol. 2012, 4, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calomino, N.; Scheiterle, M.L.P.F.; Fusario, D.; La Francesca, N.; Martellucci, I.; Marrelli, D. Porcelain Gallbladder and Its Relationship to Cancer. Eur. Surg. 2021, 53, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channa, N.A.; Khand, F.D.; Bhanger, M.I. Analysis of human gallstones by FTIR. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2008, 12, 552–560. [Google Scholar]

- Bilagi, A.; Godhi, A.S. An Analytical Study of Gallstones by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Technique. Int. Surg. J. 2022, 9, 584–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wosiewitz, U.; Schroebler, S. On the Chemistry of ‘Black’ Pigment Stones from the Gallbladder. Clin. Chim. Acta 1978, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Q.; Qu, C.; Ge, K.; Li, Y.; Jia, W.; Zhao, A. Profiling Bile Acid Composition in Bile from Mice of Different Ages and Sexes. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1626215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosch, A.R.; Imagawa, D.K.; Jutric, Z. Bile Metabolism and Lithogenesis. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 99, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wei, D.; Zhu, M.; Ying, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W.; et al. Gut Microbiota-Regulated Unconjugated Bilirubin Metabolism Drives Renal Calcium Oxalate Crystal Deposition. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2546158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulpekova, Y.; Shirokova, E.; Zharkova, M.; Tkachenko, P.; Tikhonov, I.; Stepanov, A.; Sinitsyna, A.; Izotov, A.; Butkova, T.; Shulpekova, N.; et al. A Recent Ten-Year Perspective: Bile Acid Metabolism and Signaling. Molecules 2022, 27, 1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrow, D.J. The Etiology of Pigment Gallstones. Hepatology 1984, 4, 215S–222S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichardt, F.; Lucas, L.N.; Okyere, L.; Choi, J.; Amador-Noguez, D.; Gaulke, C.A.; Anakk, S. Portal Bile Acid Composition and Microbiota along the Murine Intestinal Tract Exhibit Sex Differences in Physiology. Gut Microbes 2025, 17, 2540483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.