Impact of a Failsafe Reminder Letter and Associated Factors on Correct Follow-Up After a Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Descriptive Analysis

2.2. Univariable and Multivariable Analyses

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

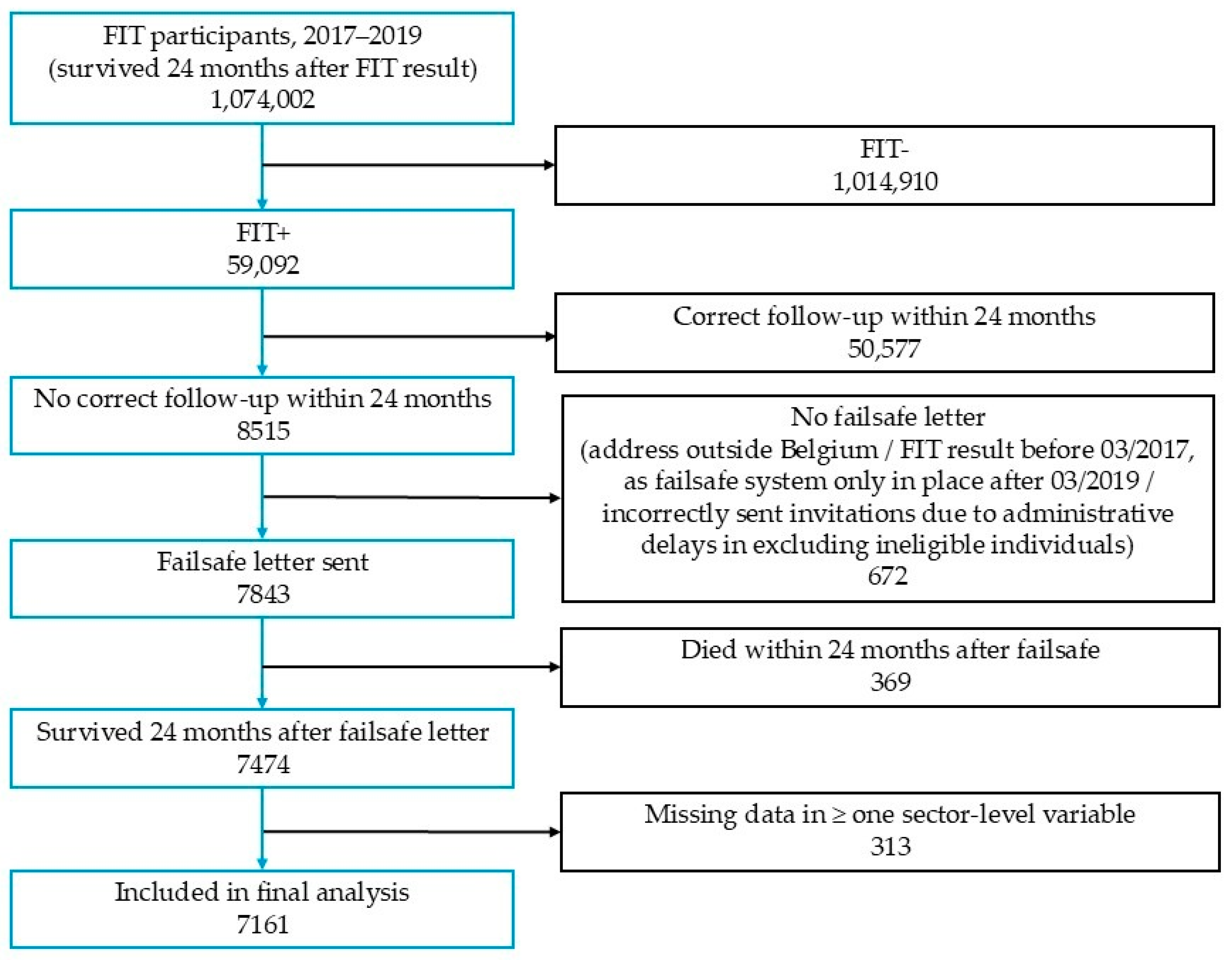

4.1. Study Population

4.2. Study Outcome

4.3. Study Determinants

- Age group (50–54; 55–59; 60–64; 65–69 & 70–74 years)

- Gender (male/female)

- Whether the failsafe letter was also sent to the person’s GP (no/yes)

- Belgian current nationality: percentage of residents with a Belgian current nationality (2024, continuous).

- Household size: average number of individuals per household (2024, continuous).

- Education level: percentage of residents aged 18–24 studying at a college/university (higher education), used as a proxy for education level (2023–2024, continuous).

- Average income: total net taxable income divided by the number of residents as of 1 January of the tax year (2022, continuous).

4.4. Statistical Analysis

4.4.1. Missing Data

4.4.2. Sample Size

4.4.3. Main Analyses

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hoeck, S.; Van De Veerdonk, W.; De Brabander, I. Do socioeconomic factors play a role in nonadherence to follow-up colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test in the Flemish colorectal cancer screening programme? Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 29, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centre for Cancer Detection (CCD); Belgian Cancer Registry (BCR). Monitoring Report of the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Programme. 2023. Available online: https://dikkedarmkanker.bevolkingsonderzoek.be/sites/default/files/2024-12/CVK24-027%20Verkorte%20Jaarfiche_DDK-BK-BHK(2024)-DEF(Hires).pdf (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Meeus, A.; Demyttenaere, B. Study Colonoscopy [Studie Colonoscopie]; Nationaal Verbond van Socialistische Mutualiteiten: Brussel, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zorzi, M.; Battagello, J.; Selby, K.; Capodaglio, G.; Baracco, S.; Rizzato, S.; Chinellato, E.; Guzzinati, S.; Rugge, M. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut 2022, 71, 561–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Gingold-Belfer, R.; Leibovitzh, H.; Boltin, D.; Issa, N.; Tsadok Perets, T.; Dickman, R.; Niv, Y. The compliance rate for the second diagnostic evaluation after a positive fecal occult blood test: A systematic review and meta-analysis. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019, 7, 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selby, K.; Senore, C.; Wong, M.; May, F.P.; Gupta, S.; Liang, P.S. Interventions to ensure follow-up of positive fecal immunochemical tests: An international survey of screening programs. J. Med. Screen. 2021, 28, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission; Moss, S.; Ancelle-Park, R.; Brenner, H. Chapter 3: Evaluation and interpretation of screening outcomes. In European Guidelines for Quality Assurance in Colorectal Cancer Screening and Diagnosis, 1st ed.; Segnan, N., Patnick, J., von Karsa, L., Eds.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hoeck, S.; De Schutter, H.; Van Hal, G. Why do participants in the Flemish colorectal cancer screening program not undergo a diagnostic colonoscopy after a positive fecal immunochemical test? Acta Clin. Belg. 2021, 77, 760–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutneja, H.R.; Bhurwal, A.; Arora, S.; Vohra, I.; Attar, B.M. A delay in colonoscopy after positive fecal tests leads to higher incidence of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 1479–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azulay, R.; Valinsky, L.; Hershkowitz, F.; Magnezi, R. Repeated Automated Mobile Text Messaging Reminders for Follow-Up of Positive Fecal Occult Blood Tests: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2019, 7, e11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cooper, G.S.; Grimes, A.; Werner, J.; Cao, S.; Fu, P.; Stange, K.C. Barriers to Follow-Up Colonoscopy After Positive FIT or Multitarget Stool DNA Testing. J. Am. Board Fam. Med. 2021, 34, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, S.; Tangka, F.K.L.; Hoover, S.; Mathews, A.; Redwood, D.; Smayda, L.; Ruiz, E.; Silva, R.; Brenton, V.; McElroy, J.A.; et al. Optimizing tracking and completion of follow-up colonoscopy after abnormal stool tests at health systems participating in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Colorectal Cancer Control Program. Cancer Causes Control 2024, 35, 1467–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coronado, G.D.; Kihn-Stang, A.; Slaughter, M.T.; Petrik, A.F.; Thompson, J.H.; Rivelli, J.S.; Jimenez, R.; Gibbs, J.; Yadav, N.; Mummadi, R.R. Follow-up colonoscopy after an abnormal stool-based colorectal cancer screening result: Analysis of steps in the colonoscopy completion process. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021, 21, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, M.K.; Brenner, A.T.; Crockett, S.D.; Gupta, S.; Wheeler, S.B.; Coker-Schwimmer, M.; Cubillos, L.; Malo, T.; Reuland, D.S. Evaluation of interventions intended to increase colorectal cancer screening rates in the United States: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zapka, J.; Taplin, S.H.; Anhang Price, R.; Cranos, C.; Yabroff, R. Factors in quality care—The case of follow-up to abnormal cancer screening tests—Problems in the steps and interfaces of care. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. Monogr. 2010, 2010, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tran, T.N.; Ferrari, A.; Hoeck, S.; Peeters, M.; Van Hal, G. Colorectal Cancer Screening: Have We Addressed Concerns and Needs of the Target Population? Gastrointest. Disord. 2021, 3, 173–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osseis, M.; Nehmeh, W.A.; Rassy, N.; Derienne, J.; Noun, R.; Salloum, C.; Rassy, E.; Boussios, S.; Azoulay, D. Surgery for T4 Colorectal Cancer in Older Patients: Determinants of Outcomes. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 12, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldach, B.R.; Katz, M.L. Health literacy and cancer screening: A systematic review. Patient Educ. Couns. 2014, 94, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Arnold, C.L.; Rademaker, A.; Bailey, S.C.; Esparza, J.M.; Reynolds, C.; Liu, D.; Platt, D.; Davis, T.C. Literacy barriers to colorectal cancer screening in community clinics. J. Health Commun. 2012, 17 (Suppl. S3), 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wools, A.; Dapper, E.A.; de Leeuw, J.R. Colorectal cancer screening participation: A systematic review. Eur. J. Public Health 2016, 26, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, T.Z.; Lau, J.; Wong, G.J.; Tan, L.Y.; Chang, Y.J.; Natarajan, K.; Yi, H.; Wong, M.L.; Tan, K.K. Factors predicting improved compliance towards colonoscopy in individuals with positive faecal immunochemical test (FIT). Cancer Med. 2021, 10, 7735–7746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, A.R.H. Incomplete diagnostic follow-up after a positive colorectal cancer screening test: A systematic review. J. Public Health 2018, 40, e46–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerrison, R.S.; Travis, E.; Dobson, C.; Whitaker, K.L.; Rees, C.J.; Duffy, S.W.; von Wagner, C. Barriers and facilitators to colonoscopy following fecal immunochemical test screening for colorectal cancer: A key informant interview study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2022, 105, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoeck, S.; Tran, T.N. Insights into Personal Perceptions and Experiences of Colonoscopy after Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Gastrointest. Disord. 2024, 6, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorzi, M.; Giorgi Rossi, P.; Cogo, C.; Falcini, F.; Giorgi, D.; Grazzini, G.; Mariotti, L.; Matarese, V.; Soppelsa, F.; Senore, C.; et al. A comparison of different strategies used to invite subjects with a positive faecal occult blood test to a colonoscopy assessment. A randomised controlled trial in population-based screening programmes. Prev. Med. 2014, 65, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fendrick, A.M.; Lieberman, D.; Chen, J.V.; Vahdat, V.; Ozbay, A.B.; Limburg, P.J. Impact of eliminating cost-sharing by Medicare Beneficiaries for follow-up colonoscopy after a positive stool-based colorectal cancer screening Test. Cancer Res. Commun. 2023, 3, 2113–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ding, L.; Jidkova, S.; Greuter, M.J.W.; Van Herck, K.; Goossens, M.; De Schutter, H.; Martens, P.; Van Hal, G.; de Bock, G.H. The Role of Socio-Demographic Factors in the Coverage of Breast Cancer Screening: Insights from a Quantile Regression Analysis. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 648278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peduzzi, P.; Concato, J.; Kemper, E.; Holford, T.R.; Feinstein, A.R. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 1996, 49, 1373–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Number (%) or Median (IQR) 1 |

|---|---|

| N = 7161 | |

| Individual-level variables | |

| Age group | |

| 50–54 | 934 (13.0%) 2 |

| 55–59 | 1439 (20.1%) |

| 60–64 | 1886 (26.3%) |

| 65–69 | 1409 (19.7%) |

| 70–74 | 1493 (20.8%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 4237 (59.2%) |

| Female | 2924 (40.8%) |

| Whether the failsafe letter was also sent to the person’s GP | |

| Yes | 6760 (94.4%) |

| No 3 | 401 (5.6%) |

| Statistical sector-level variables | |

| Percentage of Belgian current nationality | 91.4 (83.7–95.4) |

| Average household size | 2.43 (2.16–2.50) |

| Percentage of having higher education | 3.70 (2.90–4.60) |

| Average income (per 1000 EUR) | 23.0 (21.0–25.0) |

| Outcome | |

| whether a correct follow-up was performed after failsafe letter | |

| Yes | 1151 (16.1%) |

| No | 6010 (83.9%) |

| Characteristics | Having a Correct Follow-Up After Failsafe Letter Number (%) or Median (IQR) 1 | aOR (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (N = 6010) | Yes (N = 1151) | |||

| Age group | ||||

| 60–64 | 1563 (26.0%) | 323 (28.1%) | Ref | Ref |

| 50–54 | 779 (13.0%) | 155 (13.5%) | 0.95 (0.77–1.17) | 0.6272 |

| 55–59 | 1160 (19.3%) | 279 (24.2%) | 1.16 (0.97–1.38) | 0.1082 |

| 65–69 | 1175 (19.6%) | 234 (20.3%) | 0.96 (0.80–1.15) | 0.6569 |

| 70–74 | 1333 (22.2%) | 160 (13.9%) | 0.58 (0.48–0.72) | <0.0001 * |

| Percentage of Belgian current nationality | 91.3 (83.6–95.3) | 91.9 (84.4–95.6) | 1.011 (1.004–1.0194) | 0.0018 * |

| Average household size | 2.34 (2.16–2.50) | 2.35 (2.19–2.51) | 1.07 (0.85–1.34) | 0.5748 |

| Percentage of having higher education | 3.60 (2.90–4.60) | 3.80 (3.00–4.60) | 1.041 (1.002–1.080) | 0.0385 * |

| Average income (per 1000 EUR) | 23.0 (21.0–26.0) | 23.0 (21.0–25.0) | 0.976 (0.960–0.993) | 0.0045 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hoeck, S.; Tran, T.N. Impact of a Failsafe Reminder Letter and Associated Factors on Correct Follow-Up After a Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Gastrointest. Disord. 2025, 7, 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040061

Hoeck S, Tran TN. Impact of a Failsafe Reminder Letter and Associated Factors on Correct Follow-Up After a Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Gastrointestinal Disorders. 2025; 7(4):61. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040061

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoeck, Sarah, and Thuy Ngan Tran. 2025. "Impact of a Failsafe Reminder Letter and Associated Factors on Correct Follow-Up After a Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program" Gastrointestinal Disorders 7, no. 4: 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040061

APA StyleHoeck, S., & Tran, T. N. (2025). Impact of a Failsafe Reminder Letter and Associated Factors on Correct Follow-Up After a Positive FIT in the Flemish Colorectal Cancer Screening Program. Gastrointestinal Disorders, 7(4), 61. https://doi.org/10.3390/gidisord7040061