Abstract

It goes without saying that when studying the corrosion behaviour of a component or structure, the experimental conditions should reflect the service environment to which the object will be exposed. However, all too frequently, “accelerated” conditions are used, involving applied potentials, elevated temperature, high solute concentrations, excessive strain or strain rates, etc., which complicates the prediction of the in-service behaviour or component lifetime. At best, it is necessary to extrapolate the results of these accelerated laboratory measurements to more realistic conditions, ideally based on a mechanistic understanding of the processes involved. At worst, accelerated laboratory tests may suggest corrosion processes that are not feasible or relevant to the service environment, potentially disqualifying a given material or design from consideration that would otherwise provide acceptable behaviour in service. Examples of the need to properly take into account the service environment and the potential negative consequences of accelerated testing are given for the case of the corrosion behaviour of nuclear waste container materials. For example, the use of bulk solutions to study the corrosion of copper by sulfide in the laboratory involves high sulfide fluxes and leads to localized corrosion and stress corrosion cracking mechanisms that are not possible under actual repository conditions. Similarly, accelerating the effects of γ-irradiation using high absorbed dose rates runs the risk of changing the mechanism of radiation-induced corrosion. Above all, it is imperative to develop a sound mechanistic understanding of the underlying corrosion mechanisms in order to confidently apply the results of short-term laboratory observations to the prediction of the long-term performance of nuclear waste containers.

1. Introduction

As in many other disciplines, lifetime prediction is an important aspect of corrosion science [1,2,3]. Predictive models may be empirical in nature or be based on the mechanism of the corrosion process(es) involved. Regardless of the approach, there is generally a need for experimental data, either to permit direct extrapolation for empirical models or to form the basis and serve as input for mechanistic approaches. In order to make as reliable a prediction as possible, it is important that those experiments are conducted under conditions that properly reflect the service environment to which the corrodible structure is exposed.

Because service environments are generally complex, laboratory tests are often conducted under simplified environmental conditions that represent only certain aspects of the real-life conditions. In addition, since component lifetimes are generally long compared with experimental timescales, accelerated testing is often used to compress the component life cycle into a much shorter exposure period. There is nothing inherently wrong in using simplified exposure environments or accelerated experimental conditions provided that such tests do not change the mechanism(s) of corrosion and provided that a suitable means of extrapolating to more realistic conditions is available.

There are obvious dangers to the use of inappropriate environmental conditions or overly accelerated test methods. Poor experimental choices may lead to over-design of the component, either in terms of the corrosion allowance built into the design or the exclusion of materials that are entirely suitable for the purpose but that are excluded because they perform badly in accelerated or poorly designed experiments. Improper testing is also a waste of R&D resources and there are many examples of irrelevant corrosion processes that have received far more attention than they deserve. Poor experimental design is also an example of “bad science” that can erode confidence in the ultimate lifetime prediction. This is particularly important for safety-critical components where a robust and reliable prediction is crucial.

Here, the importance of proper selection of testing environments and methods and the dangers of inappropriate choices are illustrated with examples from the literature on the corrosion behaviour of nuclear waste container materials. The waste management literature is replete with examples of poor experimental design, partly because the disposal environment is so unique and partly because the timescales involved are so long. Because containers for the disposal of spent fuel (SF) and high-level waste (HLW) from reprocessing have target lifetimes of up to 1 million years in some cases, the deep geological repository (DGR) is designed so that not very much happens in terms of corrosion or, if corrosion does occur, it proceeds extremely slowly on a laboratory timescale. Such slow processes are not conducive to authors wanting publications or to Ph.D. students wanting to complete their studies within the half-life of Co-60 (5 y) rather than Cs-137 (30 y). Inevitably, therefore, accelerated testing is often used. We have all been guilty of performing ill-conceived experiments, but we have been studying the corrosion behaviour of container materials for over 40 y, and we should have by now learned from the mistakes from the past, including those of the current author.

2. The Repository Environment

There have been a number of reviews of the nature of the near-field repository environment and the factors that impact the corrosion behaviour of the container [4,5]. The intent here is not to present a detailed discussion of the various parameters that affect the corrosion and mechanical performance of the container, but instead to focus on those conditions that have proven to be either difficult or inconvenient to replicate in the laboratory. Furthermore, the focus here is on environmental conditions for repository designs in which the container is embedded in a backfill material comprising highly compacted bentonite clay (HCB).

An important question that arises is the nature of the aqueous phase in contact with the container surface. Ignoring, for the time being, the initial thermal phase during which the bentonite buffer will be unsaturated, the near-field will eventually become water-saturated by incoming ground water. However, the presence of soluble mineral impurities in the bentonite and ion exchange processes between the clay and pore water mean that the composition of the aqueous phase initially differs from that of the ground water [6,7,8,9]. It may take many centuries or longer for the pore water to equilibrate with the ground water.

There is also the question of what we mean by bentonite pore water. The most common conceptual model for the structure of compacted bentonite is the so-called dual-porosity model in which the total pore volume is divided between interlamellar porosity between individual clay particles and larger macroscopic pores associated with voids between stacks of clay particles [10]. The distribution between the interlayer and bulk porosity depends on the buffer density [8]. Because of the high specific surface area of montmorillonite (500 m2/g), the predominant mineral in bentonite clay, the average thickness of the water layer in contact with the charged montmorillonite surfaces for saturated buffer with a density of 1600 kg/m3 and a water content of 23 wt.% is only 5 Å, or approximately 2 monolayers, thick. Thus, the majority of the H2O in compacted buffer will be highly structured due to the diffuse double layer associated with the charged clay particle. Water present in the larger bulk pores may have properties similar to those of bulk H2O, but the majority of the H2O present in the clay will not. Experiments in bulk solution, or even in bentonite slurries, therefore, are not necessarily representative of the aqueous environment in contact with the container surface. However, notwithstanding the complexities of the bentonite pore water structure, the corrosion behaviour of copper in contact with compacted bentonite has been satisfactorily interpreted as if the surface is in contact with bulk pore water with a chemistry determined by the composition of the fluids used to prepare the compacted buffer [11,12].

Another important property of the compacted buffer material is that it inhibits the rate of mass transport of reactants towards, and of corrosion products away from, the container surface. In the compacted state, the hydraulic conductivity of the buffer is such that mass transport is limited to diffusion, i.e., there is no advective transport of reactants or products. The limited porosity and tortuous nature of the material results in effective diffusivities DEFF of dissolved species approximately two orders of magnitude lower than in bulk solution [13]. As a consequence, the steady-state mass-transfer coefficient kM for diffusion through compacted bentonite in the repository is a factor of 104 to 105 times lower than in a stagnant bulk solution used in laboratory studies (Table 1). It is far more likely, therefore, that the anodic and/or cathodic reactions constituting the overall corrosion process will be transport-limited rather than controlled by the rate of the interfacial kinetics.

Table 1.

A comparison of steady-state mass-transfer coefficient kM for diffusion in compacted bentonite in the repository and bulk solution in the laboratory.

As will be shown by way of example in the next section, these important properties of the compacted buffer material are often not represented in laboratory experiments. The presence of compacted buffer makes electrochemical measurements difficult but not impossible to make because of the associated iR drop and other instrumental issues. It is also impossible to make certain in situ spectroscopic and optical measurements on corroding surfaces covered by compacted clay. However, as will be shown below, there is a danger in ignoring these properties of the bentonite that misleading conclusions may be drawn regarding corrosion mechanisms that are observed in the laboratory, but which are not relevant to the repository environment.

Another unusual aspect of the repository environment is the presence of a γ- (and neutron) radiation field at the container surface. Gamma dose rates for HLW/SF containers are modest compared with the MGy/h typical of PWR reactor cores [14] or the tens of Gy/h found in the primary containment vessel at the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station [15]. Maximum dose rates for most HLW/SF container designs are of the order of 1 Gy/h or less but can be as high as 25 Gy/h at the surface of the primary carbon steel vessel of the Belgian Supercontainer design [16]. The neutron fluence is many orders of magnitude less than that required to cause the radiation embrittlement of ferrous alloys [17], so the principal issue of concern is corrosion due to the production of radiolytic oxidizing (and reducing) species.

The generally modest dose rates are the result of the use of thick-walled container designs (with a total wall thickness of 10–20 cm in some cases) and because much of the activity of the SF and/or HLW has decayed away by the time the waste is encapsulated and disposed of in the DGR. The dose rate continues to decrease post-emplacement, typically with an effective half-life of approximately 30 y (corresponding to that of Cs-137, one of the major γ-emitters). Thus, after a few hundred years, the dose rate is of the order of a few mGy/h or less. However, the in-growth of γ-emitting daughter products results in a slight increase in dose rate after 10,000 y and is maintained at a level of 0.1–1 mGy/h indefinitely [18]. Thus, although the dose rates are very low for much of the lifetime of the container, the total accumulated dose is not insignificant, reaching several MGy after 1 million years.

In common with all natural environments, microbes will be present in the DGR. The act of constructing the repository will not only introduce various microbial species, in addition to the indigenous populations already present, but will also introduce nutrients in the form of oils and greases, vehicle exhausts, and the residues from blasting operations. However, the repository environment is inhospitable to microbial activity, partly because of the limited availability of nutrients but also because of environmental stressors such as the elevated temperature and γ-radiation from the decay of the waste. Compacted bentonite also suppresses microbial activity at sufficiently high density, because of either (i) the lack of physical space in the pore structure, (ii) the physical effects due to the swelling pressure that develops when saturated compacted buffer is constrained, or (iii) the low water activity in the clay pore water [19,20,21]. As a result, the extent of microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) is expected to be minimal in the repository.

The over-riding challenge when trying to properly represent the repository environment in laboratory experiments is the vast timescale of interest. For fractured host rocks where the geology does not provide a substantial barrier to the movement of radionuclides, the target container lifetime can be 1 million years [22]. Even for low permeability sedimentary formations, there may be a regulatory requirement for a minimum container lifetime, typically of the order of 1000 y, to allow for the retrieval of the waste if necessary or to ensure containment during the initial thermal transient.

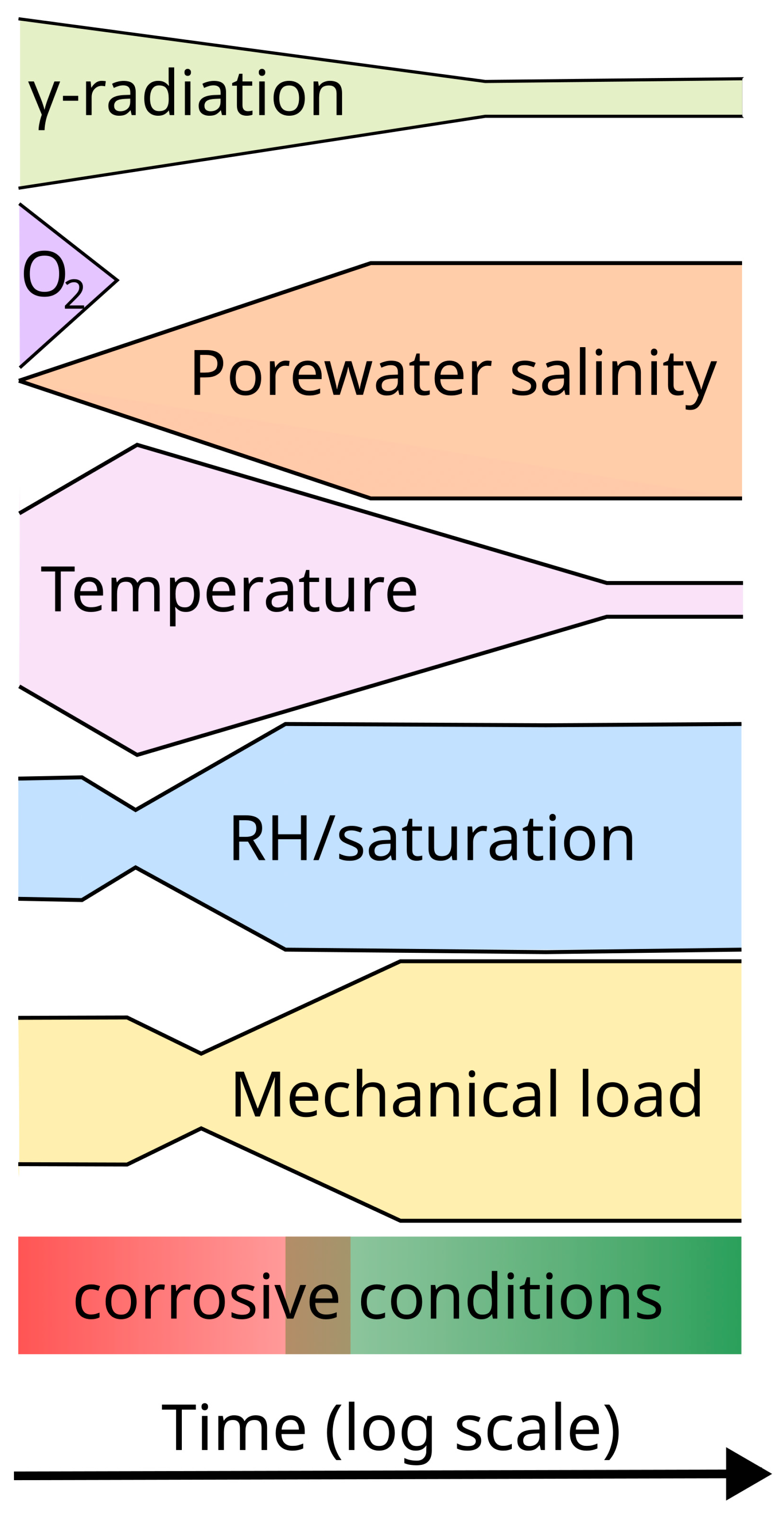

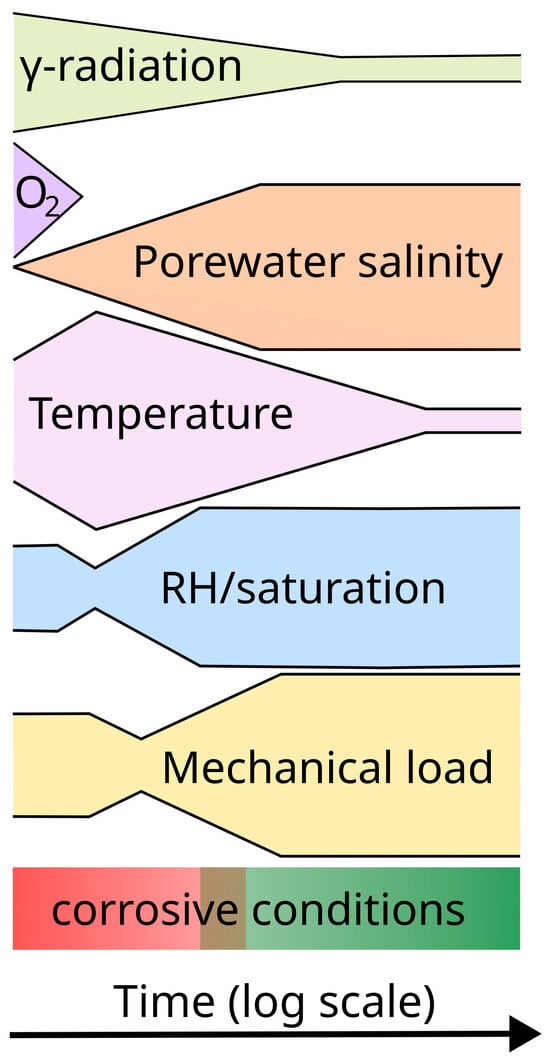

The nature of the near-field environment evolves throughout these time periods, but on different timescales for each environmental parameter (Figure 1) [4,5]. As already noted, the highest γ-dose rates will exist for a few hundred years, but the absorbed dose will continue to accumulate throughout the container service life. In contrast, the initially trapped O2 in the pores of the compacted buffer and other sealing materials may be consumed by corrosion, aerobic microbial activity, sorption by the bentonite, and by the oxidation of mineral phases in the host rock and bentonite clay within a matter of weeks or months following repository closure [23]. The initially dilute bentonite pore water will only slowly equilibrate with the ground water, and it may take hundreds or thousands of years for the salinity to increase. The peak container temperature is typically achieved 10–30 y post-closure, but the entire thermal transient may last a few tens of thousands of years before the temperature drops to ambient temperature. The bentonite is generally emplaced only partially water-saturated initially, and then further dries out closer to the container due to the heat generated by the decay of the waste. It may take a few decades or a few centuries for the buffer to fully saturate depending on the local hydraulic conductivity of the host rock. Lastly, apart from the possible presence of residual stresses from container sealing, the development of (largely compressive) external loads will generally follow similar timescales to those for the saturation of the buffer and the resulting development of the buffer swelling pressure and the hydrostatic load as the repository saturates.

Figure 1.

A stylistic representation of the timescales for the evolution of different environmental parameters of interest for the corrosion behaviour of the container. The width of each coloured outline provides a qualitative indication of the time-dependent magnitude for each of the parameters. In general, the corrosivity of the environment evolves from an initial period of warm, oxic, unsaturated conditions (red) to a less corrosive, cool, anoxic, saturated environment in the long term (green). (Figure modified based on an original concept by Kristel Mijnendonckx, private communication.).

The absolute values for each of the environmental parameters illustrated in Figure 1, and their evolution with time, will depend on the repository design and the nature of the host rock, but in general the corrosive conditions will evolve from an early period of warm, unsaturated, oxic conditions to a long-term cool, saturated, and anoxic condition. This overall evolution of conditions, and the different timescales for each environmental parameter, must be understood in order to define relevant test environments for laboratory investigations.

3. Examples of Injudicious Testing Conditions and Other Issues

In this section, several examples are given of the dangers that may arise from the inappropriate choice of testing conditions and the sometimes misleading conclusions that can arise. This presentation is not meant as a criticism of the researchers involved since, once again, the current author has made similar mistakes in the past, but is rather a warning to future investigators of the importance of relating laboratory conditions to those expected in service.

3.1. Corrosion of Copper in Sulfide Environments

Following the consumption of the initially trapped O2 (and the decay of the γ-radiation field), the corrosion of copper containers should essentially cease in the anoxic near-field environment. (Although there has been much debate about the possibility of sustained copper corrosion in O2-free pure H2O [24,25,26], this phenomenon has now been demonstrated, to the satisfaction of the Swedish regulatory authority, to be insignificant in terms of the safety of the repository [27]. This issue was never relevant to repository conditions and, had the arguments espoused here been adhered to, would never have received the level of attention that it did.) However, in the presence of sulfide ions, copper does corrode under anoxic conditions accompanied by the evolution of H2.

HS− + 2Cu + H2O → Cu2S + H2 + OH−

There are two sources of sulfide in the DGR [28,29]; namely, the ground water and remote microbial activity away from the canister surface in regions of the repository where such activity is possible (i.e., not within the HCB surrounding the container). In order for corrosion to occur, the sulfide must first diffuse through the buffer material to the container surface. Under repository conditions, it has been shown that this reaction is transport-limited due to the slow rate of diffusion of HS− through the compacted buffer material [30].

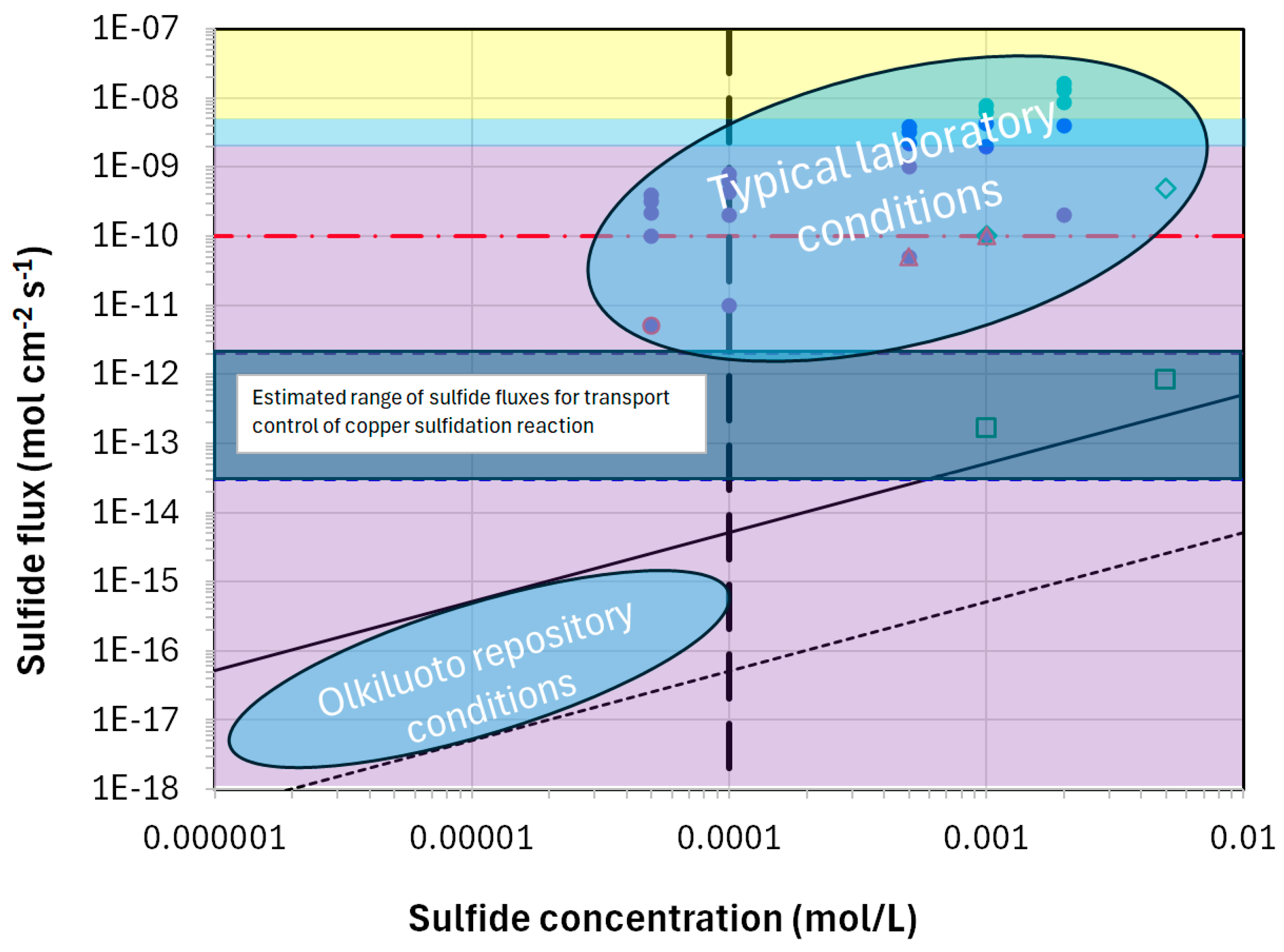

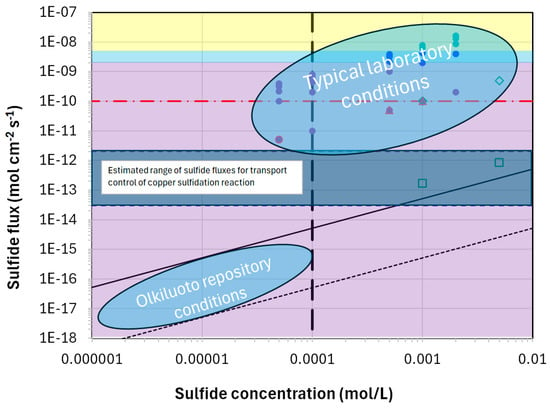

Figure 2 compares the sulfide concentrations and fluxes expected for the Olkiluoto repository site in Finland with those typically used in laboratory experiments [31,32,33]. The angled dashed and solid lines indicate the sulfide fluxes for intact and chemically eroded bentonite, respectively, and the vertical dashed line indicates the maximum sulfide concentration determined by the solubility of mackinawite. The blue horizontal bar indicates the sulfide flux for transport control of the corrosion reaction based on estimates from two different experiments [30] and the horizontal red dashed line represents the empirical threshold for the observation of crack-like defects on copper samples strained in sulfide environments [34]. The purple, blue, and yellow shaded areas correspond to the fluxes for the formation of porous (purple and blue) and compact (yellow) copper sulfide films based on electrochemical studies in bulk solutions which, along with the experimental studies indicated by the individual symbols, are discussed in more detail in [35].

Figure 2.

A comparison of the sulfide concentrations and fluxes typical of those used in laboratory experiments and those expected for the Olkiluoto repository site in Finland [31]. The angled dashed and solid lines indicate the sulfide fluxes for intact and chemically eroded bentonite, respectively, and the vertical dashed line indicates the maximum sulfide concentration determined by the solubility of mackinawite. The blue horizontal bar indicates the sulfide flux for transport control of the corrosion reaction based on estimates from two different experiments [30] and the horizontal red dashed line represents the empirical threshold for the observation of crack-like defects on copper samples strained in sulfide environments [34]. The purple, blue, and yellow shaded areas correspond to the fluxes for the formation of porous (purple and blue) and compact (yellow) copper sulfide films based on electrochemical studies in bulk solutions which, along with the experimental studies indicated by the individual symbols, are discussed in more detail in [35].

As noted above, laboratory studies are performed under accelerated conditions, in this case in terms of the sulfide flux to the corroding surface which is clearly higher in the laboratory than in the repository. The sulfide flux is important because the competition between the supply of HS− to the copper surface and the rate at which it is consumed by the interfacial reaction to form Cu2S determines the interfacial [HS−]. For sulfide fluxes greater than the transport limit (indicated by the blue horizontal band in Figure 2 and estimated to be of the order of 10−13–10−12 mol cm−2 s−1 based on two experimental studies [30]), the rate of the HS− supply is greater than the rate of consumption and the interfacial [HS−] is non-zero. In contrast, for sulfide fluxes lower than the transport limit, the rate of interfacial consumption exceeds the rate of supply and the interfacial [HS−] is zero. In turn, the interfacial [HS−] affects a number of processes and properties, including the following:

- The Cu2S film properties, with porous, non-protective films formed at low fluxes and compact, potentially passivating films formed at high fluxes [32,33] (the non-zero interfacial [HS−] associated with higher fluxes promotes more widespread nucleation, resulting in a more-compact surface film).

- The likelihood of localized corrosion since there is no driving force for the transport of HS− ahead of the uniform corrosion front if the interfacial concentration is zero. Therefore, localized forms of corrosion requiring the presence of sulfide within the pit are not possible for sulfide fluxes lower than the transport limit.

- The formation of crack-like features under tensile loading for the same reason as for localized corrosion described above [34].

Unfortunately, it is both inconvenient and time-consuming to perform laboratory experiments at low sulfide concentrations and fluxes and, inevitably, experiments are performed under accelerated conditions (Figure 2). As a result, there are reports of the formation of compact or passive Cu2S films on copper, the concern being that such films may be susceptible to localized film breakdown and pitting. There has been an extensive debate in the literature about whether such films can truly be considered to be passive, with one group arguing that the film properties and breakdown can be successfully interpreted in terms of the Point Defect Model for passive films [36,37,38], and another group arguing that the film will be porous and non-adherent due to the mismatch of the molar volumes of Cu2S and the Cu from which it is formed (the Pilling–Bedworth ratio), resulting in interfacial stresses [39,40]. Where passivity is observed in sulfide solutions, it is argued that this is the result of the formation of a Cu2O, rather than of a Cu2S, film [41].

What is clear is that passive films formed in bulk solution at relatively high [HS−] in the laboratory are formed at sulfide fluxes much higher than will exist in the repository and generally higher than the transport-limited corrosion rate (Table 1). The fact that the sulfide flux is important in determining film properties is highlighted by the properties of Cu2S films formed in the presence of compacted bentonite as reported by [42], indicated by the open green square symbols in Figure 2. In comparison to the adherent films formed in bulk solution, films formed in compacted bentonite were loosely adherent and easily removed from the copper coupons revealing bare metal beneath. Taniguchi and Kawasaki [42] also reported that the corrosion rate for the coupons in compacted bentonite were higher than those in bulk solution, despite the higher sulfide fluxes for the latter. This observation is consistent with the formation of compact (passive) films at high sulfide fluxes, but non-protective layers at the lower fluxes associated with the experiments in compacted bentonite.

There are also reports of the localized corrosion of copper in sulfide solutions under freely corroding conditions via a mechanism referred to as micro-galvanic corrosion [43,44,45]. Shallow penetrations ahead of the uniform corrosion front were observed when copper was exposed to sulfide solutions at a concentration of 5 × 10−4 mol/L but not at a concentration of 5 × 10−5 mol/L. Rather than a threshold sulfide concentration, it is suggested that this difference in behaviour reflects a threshold flux for localized attack with the lower concentration at which no localized corrosion was observed close to the transport-limited flux for copper corrosion (cf. Figure 2).

Another example of localized penetration of sulfide was reported by Yue et al. [46]. These authors reported enhanced transport of sulfur ahead of the uniform corrosion front for copper specimens exposed to a bulk solution of 10−3 mol/L HS− solution at 60 °C and suggested that these local penetrations represented a risk of embrittlement and crack initiation for copper canisters. Once again, however, these experimental conditions greatly accelerate the flux of sulfide that would be experienced by the canister. Comparison with Figure 2 suggests that the laboratory conditions corresponded to a sulfide flux greater than the transport limit and, as such, would permit local penetration of sulfide because of the non-zero interfacial sulfide concentration. As with the micro-galvanic corrosion mechanism described above, such observations are not relevant for the behaviour of a copper canister in the DGR which will experience sulfide fluxes that are 6–8 orders of magnitude lower.

Given these examples of misapplication of laboratory-scale measurements to infer the behaviour under repository conditions, the question arises how to resolve such issues. While it is feasible to conduct experiments with sulfide in the presence of compacted bentonite, as demonstrated by Taniguchi and Kawasaka [42], it is generally inconvenient and time-consuming to do so. It is certainly difficult to obtain the depth of mechanistic understanding that has been obtained from electrochemical studies in bulk solution [32,33,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Perhaps the best resolution is for researchers to be aware of the impact of the huge discrepancy in sulfide fluxes in the lab and in the repository and to be cautious about extending their results to the performance of the canister. Not all mechanisms observed in the laboratory are relevant to the repository.

3.2. Effect of γ-Irradiation

Although the extent of radiation-induced corrosion (RIC) of HLW/SF containers only amounts to a few tens of μm at most over a 1-million-year period [22], radiolysis effects have been studied more extensively than other, potentially more significant, processes [47]. However, experiments are generally performed under accelerated conditions and, in particular, at higher absorbed dose rates than those expected for the container. This use of high dose rates is partly because the concentrations of radiolysis products at repository-relevant dose rates are so low, and the resulting effect on corrosion so minimal, that any enhancement in the corrosion rate is difficult to measure. Compounding these difficulties is the fact that corrosion rates are generally measured using mass loss because of the challenges of making electrochemical measurements in a radiation field. As a result, the corrosion rates are time-averaged values, which makes it difficult to differentiate the effects of the dose rate and of the total dose, especially given the overall tendency for the corrosion rate to decrease with increasing exposure time due to film formation. Lastly, the majority of studies are conducted in solutions, whereas the presence of compacted bentonite is known to have a significant effect on the RIC of both copper [47] and carbon steel [48].

In order to predict the extent of RIC of HLW/SF containers, it is necessary to know whether the most important factor determining the corrosion behaviour is the dose rate or the total absorbed dose. If the dose rate is the most important factor, then it may be possible to define a critical value below which there is no significant effect of radiation, as is currently assumed by a number of waste management organizations [22]. If the total dose is the most important factor, then it is necessary to account for the effects of radiolysis for the entire assessment period, since a significant dose can accumulate due to irradiation at low dose rates over extended periods of time [18].

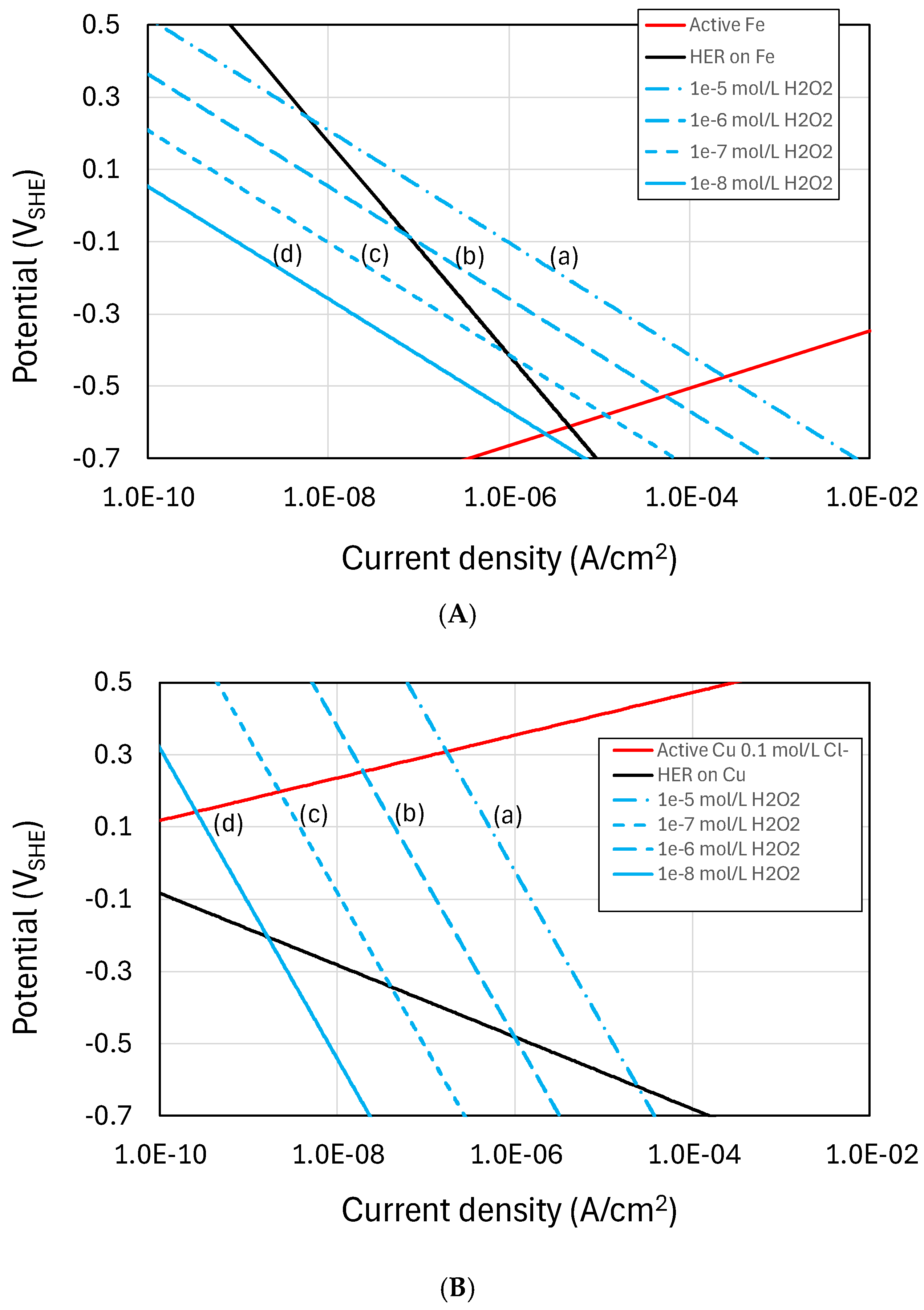

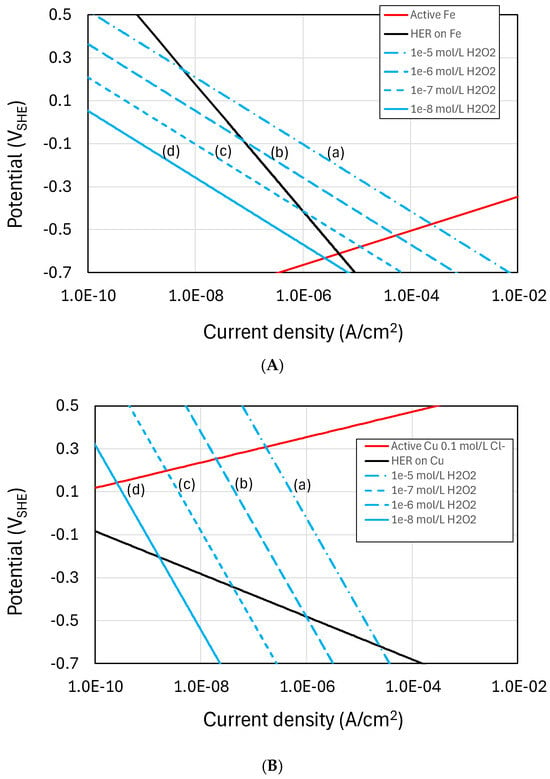

Figure 3 shows empirically based Evans diagrams for the two most important HLW/SF containers materials; namely, carbon steel and copper. The effects of irradiation are represented by the cathodic reduction of H2O2 which is one of the more important oxidizing radiolysis products and for which electrochemical kinetic data are available for carbon steel covered by a Fe3O4 film [49] and for copper [50]. Also shown are the current-potential curves for the H2 evolution reaction (HER), again based on experimental measurements [51,52], and for the active dissolution of Fe [53] and copper in Cl- solutions, the latter being diffusion-limited through 30 cm of compacted bentonite [54]. Tafel behaviour is assumed for all reactions.

Figure 3.

Evans diagram for the radiation-induced corrosion of (A) carbon steel and (B) copper. The effects of radiolysis are represented by the cathodic reduction of H2O2 for concentrations between (a) 10−5 mol/L and (d) 10−8 mol/L (based on the electrochemical kinetic data for the reduction of H2O2 from [49] and [50] for carbon steel and copper, respectively). The kinetics for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) are based on the kinetics for carbon steel given by [51] and for copper by [52]. Anodic polarization curves are shown for the active dissolution of Fe [53] and copper in Cl− solution, the latter under diffusion control in contact with 30 cm of compacted bentonite [54].

The figures show Tafel lines for the cathodic reduction of H2O2 for concentrations of (a) 10−5 mol/L to (d) 10−9 mol/L to illustrate the effect of decreasing dose rate. For this range of H2O2 concentrations, the degree of ennoblement of ECORR is insufficient to induce localized corrosion and the major impact of irradiation is the enhanced rate of uniform corrosion due to the formation of oxidizing radiolysis products. (As a guide, the predicted steady-state [H2O2] for the dose rates expected for a copper-coated steel used fuel container of Canadian design range from 6 × 10−7 mol/L to 3 × 10−9 mol/L, as the dose rate decreases with time from approximately 1 Gy/h initially to 0.1 mGy/h in the long term [55].) In the case of carbon steel, the rate of H2O2 reduction exceeds the rate of H2 evolution at the corrosion potential (ECORR) for [H2O2] greater than 10−7 mol/L (line (c) in Figure 3A). However, at lower [H2O2] corresponding to lower dose rates, the rate of H2 evolution exceeds the rate of reduction of radiolytically produced H2O2 and the effect of radiolysis would become increasingly insignificant. Because copper is more noble than carbon steel, however, the rate of H2O2 reduction exceeds the rate of H2 evolution at ECORR for all [H2O2] considered (Figure 3B) and there would be an effect of irradiation (albeit small and difficult to measure experimentally) even at low dose rates. Clearly, the effect of irradiation is more complex than suggested by these simple Evans diagrams, but this analysis would suggest that while there is a critical dose rate below which the effect of irradiation on the corrosion of carbon steel is insignificant, the same is not the case for copper and the effects of irradiation should be assessed regardless of the dose rate. In order to properly address this question of dose versus dose rate, measurements of the instantaneous corrosion rate should be made in the presence of irradiation as the dose rate is changed, rather than relying on time-averaged weight loss measurements as has typically been the case in the past.

3.3. Microbiologically Influenced Corrosion

Microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC) may take one of two broad forms [56,57]: electrical (electrochemical) microbiologically influenced corrosion (EMIC), in which electron transfer occurs directly between the metal and the organism in contact with the surface, or chemical microbiologically influenced corrosion (CMIC), in which corrosion is caused by a reaction with a corrosive metabolic by-product, such as an organic acid or sulfide. This distinction is important as, although models for predicting the impact of remote microbial activity (CMIC) are available [2,58], the corrosion science community is not currently capable of confidently predicting the extent or severity of EMIC underneath biofilms [59].

Among the numerous unique features of the repository environment considered here, the presence of highly compacted bentonite plays an important role in the MIC behaviour of the container. It has long been known that, at a sufficiently high density, HCB completely suppresses microbial activity [19,20,21]. The precise physiological reason for the suppression is still uncertain, but it is believed to be the result of either the high swelling pressure, low water activity, or the lack of physical space. Regardless, from an engineering perspective, near-field microbial activity can be suppressed through the use of HCB with a sufficiently high dry density in the range of 1400–1700 Mg/m3 depending upon the type of bentonite [21]. This suppression of near-field microbial activity has important implications for the long-term corrosion behaviour of HLW/SF containers, as it means that biofilm formation and the associated EMIC mechanisms are not possible in the repository, and only CMIC mechanisms involving the remote production of corrosive metabolic by-products and their subsequent transport to the container surface are of concern [60].

Apart from the suppression of microbial activity, the presence of compacted bentonite also complicates the application of modern DNA-based techniques used in microbial studies [61]. For this reason, many researchers have chosen to study the MIC of container materials using bentonite–water slurries, or even groundwater solutions, in order to be able to apply these sophisticated gene-sequencing techniques [62,63,64,65,66,67]. However, there is a danger in such studies as they misrepresent the nature of the near-field environment and result in biofilm formation on the metal coupons and various EMIC mechanisms that are irrelevant to the repository system. Although it is experimentally more challenging, studies of the MIC of container materials should be performed on compacted clay systems that properly represent the conditions to which the containers will be exposed [68,69].

3.4. Environmentally Assisted Cracking

It is generally accepted that the propagation rates of various environmentally assisted cracking (EAC) mechanisms are so fast compared with repository timescales that the possibility of, for example, stress corrosion cracking (SCC) can only be argued on the basis of non-initiation. This then raises the following question: how is it possible to accelerate the testing method so that non-initiation can be ensured for periods of up to 1 million years? Often, the answer is to conduct slow strain rate tests (SSRT) in suitably representative environments to assess the susceptibility to cracking. However, although such tests accelerate the mechanical loading conditions to which the container will be subjected, the test duration may be too short to allow for cracking to occur, especially if it involves the transport of hydrogen to the crack tip. Conversely, susceptibility to SCC may be revealed by SSRT but this may only be because cracks develop at plastic strains vastly greater than those relevant to the container.

In reality, it is not feasible to accelerate the EAC mechanism in a meaningful way that will allow for extrapolation over the extended timescales of interest. As with many other aspects of the long-term corrosion of HLW/SF containers, the only solution to this problem is to understand the underlying mechanisms of the cracking process and then to argue on the basis that the necessary factors for EAC either do not exist in the repository or will not exist for a very long time. For example, the laboratory observations of the “SCC” of copper in sulfide environments have been interpreted in terms of a threshold flux that must be exceeded in order for sulfide ions to be transported to the crack tip in order to sustain crack growth [34]. (“SCC” is described in quotation marks as there is a belief that the cracks observed are actually the result of intergranular corrosion with the sulfidized grain boundaries subsequently opened by excessive strain applied during SSRT [70].) Based on such mechanistic insight, it is then possible to demonstrate that the required flux of sulfide cannot be achieved under repository conditions (Figure 2).

Although it is typical to argue on the basis of non-initiation of EAC [2], it is perhaps easier to make long-term predictions of cracking based on the concept of limited propagation. This follows the general philosophy that it is easier to justify predictions over long periods of time on the basis that corrosion happens but not very fast than on the basis that it does not happen at all. Crack propagation may be limited by a number of factors associated with the near-field environment, such as the exhaustion of O2 to support crack-tip dissolution [2] (which may also manifest itself in terms of a decrease in ECORR below a threshold value for cracking) or, for cracking driven by secondary stresses, the reduction in the stress level as the crack grows. Again, a good mechanistic understanding of the EAC process is necessary to justify such predictions.

4. Summary and Conclusions

It makes common sense that researchers should do everything possible to properly replicate the actual service environment when investigating corrosion mechanisms and measuring corrosion rates. However, all too frequently, it is found that the experimental conditions are simplifications of the actual service environment and/or that inappropriate accelerated testing methods are used. Such experimental expedience may be necessary to obtain results within a reasonable period of time or, in the case of simplified environmental conditions, to be able to make measurements at all. However, there is then a danger that the experimental results may not properly represent the corrosion mechanisms or corrosion rates during service. Several examples of the misapplication of short-term laboratory observations to the prediction of the long-term performance of HLW/SF containers in deep geological repositories have been described. These examples have focused on repository designs in which the container is surrounded by a compacted bentonite buffer which has a significant effect on the evolution of the nature of the corrosive environment at the container surface. However, the conclusion that researchers should be cautious when applying the results of short-term laboratory studies to predict the long-term performance of HLW/SF containers applies to all repository designs, regardless of the container material or whether the near-field is backfilled or not. This problem is particularly acute for the nuclear waste field because of the huge timescales of interest and the inevitable need to accelerate experimental techniques in order to obtain data in a timely manner.

If it is not possible to closely replicate the service environment, then any interpretation of the observed behaviour should only be attempted on the basis of a sound mechanistic understanding of the processes involved.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to dedicate this paper to the memory of Digby Macdonald in whose honour this special edition has been published. Digby made many contributions in many areas of corrosion science, including to the prediction of the long-term performance of HLW/SF containers. Busy those he always was, Dibgy was never too busy to offer advice and share papers with colleagues.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Fraser King was employed by the company Integrity Corrosion Consulting Ltd. The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Macdonald, D.D. The role of determinism in the prediction of corrosion damage. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2023, 4, 212–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Kolàř, M.; Briggs, S.; Behazin, M.; Keech, P.; Diomidis, N. Review of the modelling of corrosion processes and lifetime prediction for HLW/SF containers—Part 1: Process models. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 124–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderko, A. Modeling of Aqueous corrosion. In Shreir’s Corrosion, 4th ed.; Cottis, R.A., Graham, M.J., Lindsay, R., Lyon, S.B., Richardson, J.A., Scantlebury, J.D., Stott, F.H., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 1585–1629. [Google Scholar]

- Shoesmith, D.W. Assessing the corrosion performance of high-level nuclear waste containers. Corrosion 2006, 62, 703–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Hall, D.S.; Keech, P.G. Nature of the nearfield environment in a deep geological repository and the implications for the corrosion behaviour of the container. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, M.V.; Cuevas, J.F.; Idiart, A.; Coene, E.; Zabala, A.B.; Ruiz, A.I.; Ortega, A.; Iglesias, R.; Melón, A.M.; Heino, V. Five-year thermos-hydro-mechanical and chemical evolution of compacted bentonite: Physical and mineralogical analysis. Appl. Clay Sci. 2025, 276, 107931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wersin, P.; Curti, E.; Appelo, C.A.J. Modelling bentonite-water interactions at high solid/liquid ratios: Swelling and diffuse double layer effects. Appl. Clay Sci. 2004, 26, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muurinen, A.; Karnland, O.; Lehikoinen, J. Ion concentration caused by an external solution into the porewater of compacted bentonite. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 119–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochs, M.; Lothenbach, B.; Shibata, M.; Yui, M. Thermodynamic modeling and sensitivity analysis of porewater chemistry in compacted bentonite. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, M.H.; Baeyens, B. Porewater chemistry in compacted re-saturated MX-80 bentonite. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2003, 61, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Litke, C.D.; Ryan, S.R. A mechanistic study of the uniform corrosion of copper in compacted Na-montmorillonite/sand mixtures. Corros. Sci. 1992, 33, 1979–1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swedish Corrosion Institute. Copper as a Canister Material for Unreprocessed Nuclear Waste—Evaluation with Respect to Corrosion; Swedish Nuclear Fuel Supply Co Report, KBS-TR-90; Swedish Nuclear Fuel and Waste Management Co: Solna, Sweden, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bourg, I.C.; Bourg, A.C.M.; Sposito, G. Modeling diffusion and adsorption in compacted bentonite: A critical review. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2003, 61, 293–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macdonald, D.D.; Engelhardt, G.R. A critical review of radiolysis issues in water-cooled fission and fusion reactors: Part II, Prediction of corrosion damage in operating reactors. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2022, 3, 694–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukaya, Y.; Watanabe, Y. Charcterization and prediction of carbon steel corrosion in diluted seawater containing pentaborate. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 498, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennet, D.G.; Gens, R. Overview of European concepts for high-level waste and spent fuel disposal with special reference waste container corrosion. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 379, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Behazin, M.; Nam, J.; Keech, P. Internal Corrosion of Used Fuel Container; Nuclear Waste Management Organization Technical Report, NWMO-TR-2019-02; Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO): Toronto, ON, Canada, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Morco, R.P.; Joseph, J.M.; Hall, D.S.; Medri, C.; Shoesmith, D.W.; Wren, J.C. Modelling of radiolytic production of HNO3 relevant to corrosion of a used fuel container in deep geologic repository environments. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroes-Gascoyne, S.; Hamon, C.J.; Maak, P.; Russell, S. The effects of the physical properties of highly compacted smectite clay (bentonite) on the culturability of indigenous microorganisms. Appl. Clay Sci. 2010, 47, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, H.M.; Bailey, M.T.; Lloyd, J.R. Bentonite barrier materials and the control of microbial processes: Safety case implications for the geological disposal of radioactive waste. Chem. Geol. 2021, 581, 120353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taborowski, T.; Bengtsson, A.; Chukharkina, A.; Blom, A.; Pedersen, K. Bacterial Presence and Activity in Compacted Bentonites. MIND (Microbiology In Nuclear waste Disposal) Report, Deliverable 2.4, Version 2, Issued 25 April 2019. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/research/participants/documents/downloadPublic?documentIds=080166e5c38ed173&appId=PPGMS (accessed on 9 April 2020).

- King, F.; Kolàř, M.; Briggs, S.; Behazin, M.; Keech, P.; Diomidis, N. Review of the modelling of corrosion processes and lifetime prediction for HLW/SF containers—Part 2: Performance assessment models. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2024, 5, 289–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroud, N.; Tomonaga, Y.; Wersin, P.; Briggs, S.; King, F.; Vogt, T.; Diomidis, N. On the fate of oxygen in a spent fuel emplacement drift in Opalinus Clay. Appl. Geochem 2018, 97, 370–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hultquist, G. Hydrogen evolution in corrosion of copper in pure water. Corros. Sci. 1986, 26, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakálos, P.; Hultquist, G.; Wikmark, G. Corrosion of copper by water. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2007, 10, C63–C67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedin, A.; Johansson, A.J.; Lilja, C.; Boman, M.; Berastegui, P.; Berger, R.; Ottosson, M. Corrosion of copper in pure O2-free water? Corros. Sci. 2018, 137, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strömberg, B.; Calota, E.; Liu, J.; Egan, M. Assessment of canister degradation for the encapsulation of spent nuclear fuel: Key research issues encountered in recent regulatory reviews and government decision making in Sweden. Adv. Geosci. 2023, 62, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Pekala, M.; Alt-Epping, P.; Pastina, B.; Maanoja, S.; Wersin, P. 3D modelling of long-term sulfide corrosion of copper canisters in a spent nuclear fuel repository. Appl. Geochem 2022, 146, 105439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Kolàř, M.; Puigdomenech, I.; Pitkänen, P.; Lilja, C. Modeling microbial sulfate reduction and the consequences for corrosion of copper canisters. Mater. Corros. 2021, 72, 339–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Shoesmith, D.; Lilja, C. Sulphide-transport control of the corrosion of copper canisters. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2017, 52, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koho, P.; King, F.; Prihti, T.; Salonen, T.; Koskinen, L.; Pastina, B. Treatment of canister corrosion in Posiva’s safety case for the operating licence application. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 1567–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Wu, L.; Noël, J.J.; Shoesmith, D.W. The influence of sulphide transport on the growth and properties of copper sulphide films on copper. Corros. Sci. 2014, 87, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Shoesmith, D.W. Key parameters determining structure and properties of sulphide films formed on copper corroding in anoxic sulphide solutions. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 415–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salonen, T.; Lamminmäki, T.; King, F.; Pastina, B. Status report of the Finnish spent fuel geologic repository programme and ongoing corrosion studies. Mater. Corros. 2021, 72, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posiva. Canister Evolution; Working Report WR-2021-06; Posiva Oy: Eurajoki, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, F.; Dong, C.; Sharifi-Asl, S.; Lu, P.; Macdonald, D.D. Passivity breakdown on copper: Influence of chloride ion. Electrochim. Acta 2014, 144, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Xu, A.; Dong, C.; Mao, F.; Xiao, K.; Li, X.; Macdonald, D.D. Electrochemical investigation and ab initio computation of passive film properties on copper in anaerobic sulphide solutions. Corros. Sci. 2017, 116, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Ghanbari, E.; Mao, F.; Rajala, P.; Carpén, L.; Macdonald, D.D. Kinetic properties of the passive film on copper in the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2018, 165, C450–C460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, T.; Smith, J.; Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Noël, J.J.; Shoesmith, D.W. The properties of electrochemically-grown copper sulfide films. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, C9–C18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martino, T.; Chen, J.; Guo, M.; Ramamurthy, S.; Shoesmith, D.W.; Noël, J.J. Comments on E. Huttunen-Saarivirta et al., “Kinetic Properties of the Passive Film on Copper in the Presence of Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria”, J. Electrochem. Soc. 165(9) (2018) C450–C460. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019, 166, Y13–Y16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Daub, K.; Dong, Q.; Long, F.; Binns, W.J.; Daymond, M.R.; Shoesmith, D.W.; Noël, J.J.; Persaud, S.Y. The early-stage corrosion of copper materials in chloride and sulfide solutions: Nanoscale characterization and the effect of microstructure. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2022, 169, 031509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taniguchi, N.; Kawasaki, M. Influence of sulfide concentration on the corrosion behaviour of pure copper in synthetic seawater. J. Nucl. Mater. 2008, 379, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Martino, T.; Shoesmith, D.W. Non-uniform film growth and micro-macro-galvanic corrosion of copper in aqueous sulphide solutions containing chloride. Corros. Sci. 2017, 114, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Qin, Z.; Martino, T.; Guo, M.; Shoesmith, D.W. Copper transport and sulphide sequestration during copper corrosion in anaerobic aqueous sulphide solutions. Corros. Sci. 2018, 131, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Pan, X.; Nie, H.Y.; Kobe, B.; Bergendal, E.; Lilja, C.; Behazin, M.; Shoesmith, D.W.; Noël, J.J. Topographical and statistical studies of the corrosion damage underneath a sulfide film formed on a Cu surface. Corros. Sci. 2025, 248, 112801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Malmberg, P.; Isotahdon, E.; Ratia-Hanby, V.; Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Leygraf, C.; Pan, J. Penetration of corrosive species into copper exposed to simulated O2-free groundwater by time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS). Corros. Sci. 2023, 210, 110833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behazin, M.; Briggs, S.; King, F. Radiation-induced corrosion model for copper-coated used fuel containers. Part 1. Validation of the bulk radiolysis submodel. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 1834–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagra. Design and Performance Assessment of HLW Disposal Canisters. National Cooperative for the Disposal of Radioactive Waste, Nagra Technical Report NTB 24-20. 2024. Available online: https://drbg.ch/rbg-gtl/referenzberichte/2768-ntb-24-20 (accessed on 22 June 2025).

- Calvo, E.J.; Schiffrin, D.J. The reduction of hydrogen peroxide on passive iron in alkaline solutions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1984, 163, 257–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazquez, M.V.; de Sanchez, S.R.; Calvo, E.J.; Schiffrin, D.J. The electrochemical reduction of hydrogen peroxide on polycrystalline copper in borax buffer. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1994, 374, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ede, M.C.; Angst, U. Tafel sloped and exchange current densities of oxygen reduction and hydrogen on steel. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi-Asl, S.; Macdonald, D.D. Investigation of the kinetics and mechanism of the hydrogen evolution reaction on copper. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2013, 160, H382–H391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asakura, S.; Nobe, K. Electrodissolution kinetics of iron in chloride solutions. Part I. Neutral solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1971, 118, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F.; Litke, C.D.; Quinn, M.J.; LeNeveu, D.M. The measurement and prediction of the corrosion potential of copper in chloride solutions as a function of oxygen concentration and mass-transfer coefficient. Corros. Sci. 1995, 37, 833–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S.; Behazin, M.; King, F. Validation of water radiolysis models against experimental data in support of the prediction of the radiation-induced corrosion of copper-coated used fuel containers. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2025, 6, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enning, D.; Garrelfs, J. Corrosion of iron by sulfate-reducing bacteria: New views of an old problem. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xu, D.; Chen, C.; Li, X.; Jia, R.; Zhang, D.; Sand, W.; Wang, F.; Gu, T. Anaerobic microbiologically influenced corrosion mechanisms interpreted using bio energetics and bioelectrochemistry: A review. J. Mater. Sci. Tech. 2018, 34, 1713–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciales, A.; Peralta, Y.; Haile, T.; Crosby, T.; Wolodko, J. Mechanistic microbiologically influenced corrosion modeling—A review. Corros. Sci. 2019, 146, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, B.J.; Blackwood, D.J.; Hinks, J.; Lauro, F.M.; Marsili, E.; Okamoto, A.; Rice, S.A.; Wade, S.A.; Flemming, H.-C. Microbially influenced corrosion—Any progress? Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F. Microbiologically influenced corrosion of nuclear waste containers. Corrosion 2009, 65, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mijnendonckx, K.; Monsieurs, P.; Černá, K.; Hlaváčová, V.; Steinová, J.; Burzan, N.; Bernier-Latmani, R.; Boothman, C.; Miettinen, H.; Kluge, S.; et al. Molecular techniques for understanding microbial abundance and activity in clay barriers used for geodisposal. In The Microbiology of Nuclear Waste Disposal; Lloyd, J.R., Cherkouk, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Rajala, P.; Bomberg, M.; Carpén, L. Corrosion of copper in oxygen-deficient groundwater with and without deep bedrock micro-organisms: Characterisation of microbial communities and surface processes. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 396, 1044–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen-Saarivirta, E.; Rajala, P.; Carpén, L. Corrosion behaviour of copper under biotic and abiotic conditions in anoxic ground water: Electrochemical study. Electrochim. Acta 2016, 203, 350–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushko, V.; Dressler, M.; Wei, S.T.-S.; Neubert, T.; Kühn, L.; Cherkouk, A.; Stumpf, T.; Matschiavelli, N. No signs of microbial-influenced corrosion of cast iron and copper in bentonite microcosms after 400 days. Chemosphere 2024, 363, 143007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, R.; Černoušek, T.; Stoulil, J.; Kovářová, H.; Sihelská, K.; Špánek, R.; Ševců, A.; Steinová, J. Anaerobic microbial corrosion of carbon steel under conditions relevant for deep geological repository of nuclear waste. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 800, 149539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, A.A.; Jalique, D.R.; Medihala, P.; Stroes-Gascoyne, S.; Wolfaardt, G.M.; McKelvie, J.; Korber, D.R. Bacterial diversity and production of sulfide in microcosms containing uncompacted bentonites. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černoušek, T.; Ševců, A.; Shrestha, R.; Steinová, J.; Kokinda, J.; Vizelková, K. Microbially influenced corrosion of container material. In The Microbiology of Nuclear Waste Disposal; Lloyd, J.R., Cherkouk, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam; The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 119–136. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, K.; Ford, S.E.; Binns, W.J.; Diomidis, N.; Slayer, G.F.; Neufeld, J.D. Stable microbial community in compacted bentonite after 5 years of exposure to natural granitic groundwater. mSphere 2023, 8, e00048-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maanoja, S.; Lakaniemi, A.-M.; Lehtinen, L.; Salminen, L.; Auvinen, H.; Kokko, M.; Palmroth, M.; Muuri, E.; Rintala, J. Compacted bentonite as a source of substrates for sulfate-reducing microorganisms in a simulated excavation-damaged zone of a spent nuclear fuel repository. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 196, 105746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taxén, C.; Núñez, A.M.; Lilja, C. Stress corrosion of copper in sulfide solutions: Variation on pH-buffer, strain rate, and temperature. Mater. Corros. 2023, 74, 1632–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.