Abstract

Due to its very high theoretical specific capacity, lithium is still considered a promising anode material for innovative next-generation battery cells. The aim is to produce thin lithium metal anodes (LMAs) that are sufficient for the battery cell due to the lithium already present in the cathode and thus additionally increase the energy density of the cell. The production of thin lithium layers (<10 µm) is challenging with most processes, and very costly with decreasing thickness. In this study, the use of magnetron sputtering to deposit thin layers of lithium for the production of LMAs is tested. An innovative process—the deposition of lithium from a liquid phase via Hot Target Sputtering—will be presented that has the potential to overcome the previous limitations in the deposition rate, and enables the potential for industrial application. The process was successfully tested in terms of general process control, stability and reproducibility and used to produce lithium metal anodes. These were then successfully integrated in All-Solid-State-Battery (ASSB) cells and compared with a lithium reference foil in a C-rate test with regard to their electrochemical performance reaching ≈ 110 mAh g−1 at a 1C discharge rate.

1. Introduction

In the context of maximizing the energy density of lithium-ion batteries (LIBs), the use of lithium metal anodes (LMAs) has for a long time been a key area of battery cell-related research. By using lithium metal with its high theoretical specific capacity, both the gravimetric and the volumetric energy density of traction batteries can be increased, resulting in a longer range for battery electric vehicles (BEVs). However, the theoretical advantages of LMAs come with a number of challenges due to the mechanical and chemical properties that limit the processing and utilization of the technology in secondary batteries. All-Solid-State-Batteries (ASSBs) have been increasingly viewed as a promising successor technology to conventional lithium-ion batteries due to their potentially superior characteristics. The replacement of the liquid electrolyte with a solid-state electrolyte (SSE) is also expected to promote the application of LMAs by preventing dendrite growth through the solid interface. In addition to the prevention of dendrites, the production of very thin homogeneous lithium films (<10 µm) is another focus of investigation. The amount of lithium required on the anode side is potentially very small, and conventional rolling processes, that are being used to produce lithium foils, are limited towards low thicknesses and increase significantly in price with decreasing film thickness. Alternative processes for manufacturing high-quality LMAs at thin thicknesses are being investigated but have not yet been industrially demonstrated. Therefore, thin-film processes offer potential advantages with regard to the production of LMAs and other thin metallic anodes.

For a sustainable production of electrodes with optimized interfacial properties and improved long-term stability, coating technologies such as Physical Vapour Deposition (PVD) offer great potential due to their ability to deposit homogeneous thin films with precise control of the desired film thickness. Within PVD, sputter deposition is a well-known process in which an electrical gas discharge is ignited in an inert gas (typically argon) at low pressure (approx. 10−3 mbar). The resulting argon ions are accelerated towards the cathode (target) by an electric field. The impact impulse of the ions is transferred to the target material, causing an impact cascade. The target atoms are knocked off the surface by sufficient impact of the ion bombardment, resulting in a deposition of the material on the opposite substrate. To increase the plasma density and thus the deposition rate, a special water-cooled magnet arrangement is used below the cathode. This process, known as magnetron sputter deposition, has been identified as a cost- and resource-efficient manufacturing process for metallic ASSB anodes, e.g., in the form of pure lithium metal layers, as well as for the pre-lithiation of various anode structures and materials (e.g., silicon and sodium). Conventional PVD processes, however, are limited in the possible deposition rates that can be achieved, so that large-scale use is focused on specific applications (e.g., architectural glass). Hot Target Sputtering (HTS) is an innovative approach that enables significantly higher deposition rates by sputtering from a liquid phase target in a molten state. Due to the low melting temperature of lithium, the sputter target can be easily brought into a liquid state while using a sputter-up process. As the temperature increases, the sublimation energy of the target atoms decreases and atoms are knocked off more easily by ion impact. In addition to the sputtering process, additional evaporation takes place, leading to high-rate deposition in low-pressure magnetron sputtering (MS). In this study, we investigate HTS as a suitable process for the production of thin LMAs and compare it with the conventional magnetron sputter deposition. With its high deposition rates and the ability to form thin films, HTS has the potential to be applied on an industrial scale in the battery field.

The scope of our research is to compare conventional and Hot Target Sputtering of lithium for battery anodes. Furthermore, the identification of a standard HTS process procedure for the production of LMAs with optimized compositional and structural properties is investigated. By systematically varying the applied process parameters, such as sputtering power, specific process–product relationships are evaluated. Special attention is given to the influence of the varied parameters on the resulting deposition rate of the metallic lithium on the current collector. Increasing the deposition rate allows the process to be used economically and the possibility to precisely adapt the desired film thickness allows us to avoid a possible excess of lithium in the cell. Understanding the associated process–product relationships can significantly facilitate the development of resource- and performance-optimized battery anode production technologies.

2. State of Research

This section reviews the current state of the art in LMA fabrication, focusing on different fabrication methods. Special attention will be given to PVD processes for thin-film deposition and to previous approaches of liquid phase sputtering as a novel process for advantageous deposition behaviour.

The cell chemistry of a battery and the choice of materials at the component level are subject to constant change. In conventional state-of-the-art LIBs, graphite with a theoretical specific capacity of 372 mAh g−1 is commonly used on the anode side [1]. In addition to graphite as an active material, the graphite anode consists of several materials such as conductive carbon black, solvents, binders and additives. At the current state of research, a number of other anode active materials, such as silicon–carbon composites, are being considered for use depending on the cell concept and chemistry.

In addition to graphite, especially pure lithium metal with a theoretical specific capacity of 3860 mAh g−1 offers significant advantages as an anode material for batteries [2]. However, the use of LMAs is not yet widespread in commercial application because the morphology of the electrochemically deposited lithium can become a problem when lithium dendrites form during charging and discharging [2]. In the worst case, dendrite growth can puncture the separator and thus cause the battery to short-circuit. This effect is exacerbated by contamination or an uneven surface of the LMAs [3]. With regard to innovative battery technologies such as ASSBs, the LMA is experiencing a renaissance due to the potential to inhibit dendrite growth at the interface by using a solid electrolyte. Within the solid electrolytes, a distinction is generally made between oxides, sulphides and polymers as material systems. The individual materials have different advantages and disadvantages and also differ in their compatibility with lithium metal. Oxide solid electrolytes as Lithium Lanthanum Zirconium Oxide (LLZO) are well compatible with lithium, while sulphides are highly reactive towards it [4]. With polymers, on the other hand, the challenge of dendrite formation, not compatibility, remains the obstacle [5]. In order to combine the benefits of different SSE Materials, hybrid systems are used [6].

Besides the obstacles with dendrite growth and compatibility, the production of thin LMAs (<10 µm) is a major challenge in achieving high volumetric energy densities and reduced thickness at the cell level [7]. Conventional lithium foils (>10 µm) contain an excess of lithium on the cell level. As there is already sufficient lithium in the cell on the cathode side, only a very thin layer is required on the anode side. Moreover, lithium is highly reactive and must be processed in a dry room or under an inert gas atmosphere to avoid oxidation. Handling of the lithium foil is further hampered by the adhesive nature of the material and its tendency to stick to rollers and handling equipment, such as grippers [8,9]. The identification and implementation of scalable, efficient processes for the production of LMAs remains a challenge for the industrialization of the technology but is only focused on in a few publications. In terms of the current state of the art, lithium metal foils are commonly used and are commercially available between 20 and 500 µm—either, e.g., as a free-standing foil or laminated onto a copper substrate. Various methods for manufacturing thin lithium layers/films have been described in the literature and are briefly summarized below. It is important to note that these processing steps commonly take place under a closed protective atmosphere, as lithium is highly reactive [10].

- Rolling/Extrusion

Traditionally, lithium foil is produced by rolling, where lithium granules or molten lithium are first extruded and then compacted in several rolling steps to produce a homogeneous thin lithium foil. With this process, decreasing foil thicknesses are associated with a significant increase in cost, resulting in high prices. In addition, the process is limited when it comes to thicknesses below 50 µm due to the mechanical strength of lithium. The lithium foil produced can then be either applied to a current collector foil or directly laminated to a solid-state electrolyte.

- Melt infusion/coating

Melt coating or liquid lithium processing has been demonstrated as another coating process for the production of LMAs. In melt coating, the metallic lithium anode is produced by melt processing. The lithium can be infiltrated into a porous host lattice, such as carbon. In this process, a surface pretreatment in the form of a lithophilic coating can lead to improved wettability [2,11]. In liquid lithium processing, a pre-coated copper foil is coated with molten lithium in a roll-to-roll process using a heated bath.

- Lithium Plating

In lithium plating, the lithium is deposited in situ on the anode during the first charge cycle. The actual anode is initially free of lithium. The capacity losses during the first cycle are small compared to conventional Li-ion cells because there is no anode material to irreversibly consume a reversible part of the capacity [12]. The lithium that enters the anode after the first charge cycle comes from the cathode. This avoids the problem of material handling. However, it should be noted that there is a volume change at the anode due to the electrochemical plating.

- Magnetron sputtering

Thin metallic lithium films can also be produced by vacuum deposition. PVD processes are suitable for this purpose. Layer deposition in a vacuum is advantageous in terms of precisely creating the required thin layer thickness [9]. Cathode sputtering as a Physical Vapour Deposition process describes the atomic erosion of surfaces, which is caused by the bombardment of sufficiently energetic ions or atoms. The process takes place in a vacuum chamber [13,14].

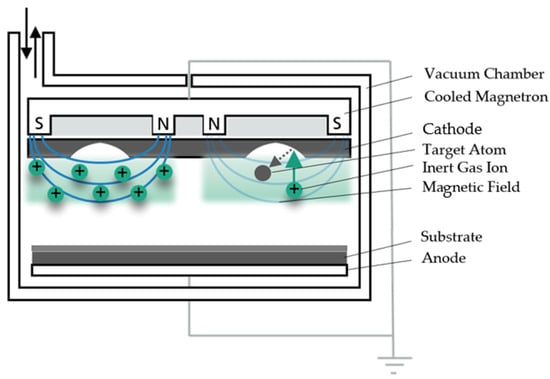

In sputtering, target atoms are ejected from a target surface, serving as the coating material. The target is provided with a negative bias voltage and thus switched as a cathode. Process gases are fed into the vacuum chamber. Due to the applied negative voltage, the atoms of the process gas are ionized by collisions with accelerated electrons. This releases more electrons to aid the ionization process. The positively charged gas ions, neutral gas atoms and the electrons form a plasma inside the vacuum chamber. The applied electrical voltage accelerates the positively charged ions towards the negatively charged cathode. As the ions impact the target surface, momentum is transferred from the high-energy ions. The ions collide with the target atoms on the surface, which in turn transfer their momentum to atoms that are still deeper in the target volume. This results in a cascade of collisions that knock out target atoms near the surface [14]. The ejected target atoms pass through the gas space of the vacuum chamber to the substrate. The target atoms are deposited on the substrate, forming a new solid film [14]. Figure 1 shows both a schematic representation of the general PVD process and a representation of a sputtering process. Inert gases are often used in these processes—most commonly argon. As an inert gas, argon prevents unwanted reactions on the target and substrate and is cost-effective.

Figure 1.

Basic principle of magnetron sputtering.

In MS, a permanent magnet is attached to the cathode to enhance the plasma near the cathode. Due to the magnetic field, electrons which move away from the cathode are deflected perpendicular to their velocity and the direction of the field line by the Lorentz force. The resulting longer dwell time of the electrons in the plasma near the cathode also increases the ionization effect of the individual electrons, which in turn leads to a higher local sputtering effect [14]. The locally enhanced plasma regions result in clearly visible sputtering trenches at the target. Increased material removal occurs in these areas. However, by using the magnetic field and the resulting intense plasma region, higher current and power densities can be achieved at low pressures and voltages. The sputtering trenches created during MS limit the material yield, so that only about 30 per cent of the target material can be used [14].

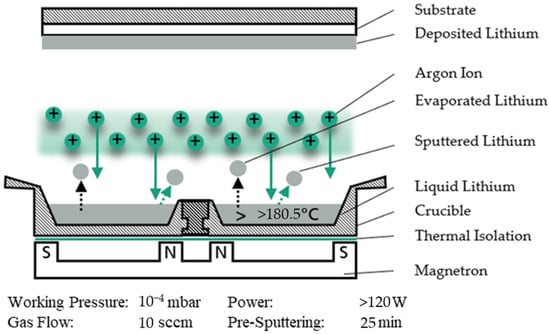

MS deposition rates are limited, ranging between 1 and 10 nm s−1 depending on the given parameters and materials. To deposit several microns of material, the resulting process time is only suitable for certain industrial applications. By heating up the target, deposition rates can be increased by local evaporation processes and reduced sublimation energy on the target surface. For low melting point materials, deposition rates can be further enhanced by increasing the simultaneous evaporation through a target in a liquid state. Deposition rates of 10–100 nm s−1 can be achieved, significantly extending the applicability of the method to thick films and larger scales. In conventional MS, the cathode, the sputter target and the permanent magnets are cooled during the process. In Hot Target Sputtering (HTS), the sputter target is thermally isolated from the cooled magnetron. The energy introduced into the target during the process is barely dissipated, resulting in a rising target temperature and subsequently a liquid target for materials with a low melting point, such as lithium (180.5 °C). A liquid target requires a sputter-up process, as shown in Figure 2, where the target is placed under the substrate to prevent the dripping of the molten metal. The crucible containing the liquid target material must have a respective high melting temperature and the target material must be insoluble in the crucible material. Working with hot targets is not entirely new—several published papers show the effect of a hot target, for example, on the deposition rate of magnetron sputtering systems. Sasaki and Koyama compared the MS process of a liquid and a solid tin target and achieved a three times higher deposition rate by Hot Target Sputtering [15]. For example, Coventry et al. demonstrate sputtering Sn from a liquid phase and show the temperature dependence using He and D as precursor gases [16]. Makarova et al. and Bleykher et al. show the high-rate deposition of copper (melting temperature of 108.5 °C) by MS from a liquid phase with an increased particle flux of 10 times and more [17]. The resulting values of the coating in terms of adhesion and hardness have been superior to conventional sputtering. Building on this, they have investigated the thermal processes and the atomic emission of MS from a liquid phase with copper targets in several publications [18,19,20,21,22]. Yuryeva et al. have demonstrated copper deposition rates of 200 nm/s, which exceed the conventional sputtering rates by a factor of twenty. They also investigate the effect of the crucible material on the operation of the liquid copper target sputtering process [23].

Figure 2.

Basic principle of Hot Target Sputtering.

For liquid phase sputtering of lithium, only a few publications have addressed the potential for high-rate deposition (Table 1). Allain et al. show the effect of sputtering lithium from both a solid and a liquid phase, focusing on the sputtering yields with D+, H+ and Li+ ions [24]. Here, a Colutron ion source is used to accelerate the said ions on metallic lithium with an angle of 45° that has been heated to 200 °C. In all cases shown, the sputtering yield was higher in the liquid state compared to a solid target. Particular attention has been paid to the role of the deuterium saturation of lithium and its effect on sputtering yield. A further advantage of using a liquid target is the material utilization that is not limited on the sputtering trenches usually created by the magnetron. The authors are not aware of any examples of HTS directly related to applications in the field of battery cell or component production.

Table 1.

Overview of publications focusing on sputtering of different materials in solid and liquid state.

With regard to the use of LMAs, commercially available components are often described in the literature and are electrochemically investigated in full cells with a cathode–separator composite. Anodes produced by sputter deposition or HTS are sparsely represented; accordingly, results from electrochemistry are hardly available. MS deposition is more commonly used in the deposition of protective coatings for battery components [33,34,35].

3. Materials and Methods

In this section, the used materials and methods are described. Beginning with target preparation, the preparation of the processes is described followed by the experimental setup for both conventional MS and HTS. The first step was to determine and compare the deposition behaviour of the two processes, and then to focus on the HTS process and to investigate its stabilization to enable reproducibility. Lastly, the cell manufacturing of ASSB coin cells is described to test the manufactured LMAs electrochemically towards their performance. The lithium used to produce the metallic lithium target was supplied by Sigma Aldrich (Taufkirchen, Germany) and has a purity of 99 per cent. A 100 g container was required for the series of experiments. The 99 per cent pure lithium foil was purchased from Rockwood Holdings (Langelsheim, Germany) (now Albemarle). The argon that is used in the sputtering processes is 99.999 per cent pure and was purchased from Linde (Pullach, Germany). The gas was stored in 50-litre cylinders at 200 bar.

- Target preparation

The molybdenum crucible used in this series of tests is an essential component of the sputtering process. The crucible is custom-made and consists of more than 99 percent molybdenum. The molybdenum is chosen for its high melting point to ensure that the crucible would not be damaged during the process. The crucible has an inner diameter of 9 cm and a centre hole in the middle for an M6 hexagon socket screw to secure the crucible to the magnetron source. In addition, the crucible has a wider rim at the top to prevent liquid lithium from leaking out of the crucible and causing a short circuit between the magnetron cathode and the protective shield. This ensures a more stable process.

The basic building block of this investigation is lithium, which is in the form of granules or foil and must therefore first be melted down to form a target. The molybdenum crucible is then placed on a hot plate in the glove box. A small quantity of lithium granules, approx. 10 g, is then filled into the crucible and the hotplate is set to a temperature above 180 °C. The temperature is then adjusted to 200–250 °C. The temperature of the hotplate is then set at 180 °C. During the melting process, the lithium granules are distributed in the crucible by means of Al2O3 platelets. As soon as some of the lithium melts, another 10 g of lithium is added. After a liquid lithium mass is formed, the hotplate is switched off. Finally, the crucible is cooled in the glovebox for 30 min.

- Experimental Setup

A Fraunhofer IST sputtering system is used to deposit the lithium layers on copper foil and to implement a standard sputtering processes procedure. The system consists of the vacuum chamber, an upstream glove box that can be purged with nitrogen or argon, a Pfeiffer Vacuum (Aßlar, Germany) Duo 20 MC rotary vane pump, an ILMVAC (Ilmenau, Germany) oil diffusion pump and two Advance Energy (Denver, CO, USA) MDX500 DC generators. The system is also equipped with an MKS (Andover, MA, USA) C674C Multi-Gas Controller to regulate the gas flow. The Blazers Total Pressure Controller 200 from Pfeiffer (Aßlar, Germany) is used to display the pressure, which is measured via the IKR 020 Penning tube from Pfeiffer (Aßlar, Germany) and the Pirani gauge TPR 010 Pirani, also from Pfeiffer Blazers (Aßlar, Germany). The sputter magnetrons used are water-cooled PPS-90 UV magnetrons from Ardenne Anlagentechnik GmbH (Dresden, Germany). In addition, Inficon (Bad Ragaz, Switzerland) quartz crystals with a frequency in the range of 6 MHz are placed in front of the sputter sources and are read out by an Inficon (Bad Ragaz, Switzerland) Q-Pod deposition monitor. The oscillating quartz can be used to determine the current sputtering rate and the film thickness during the process. The schematic structure inside the vacuum chamber can be seen in Figure 2.

- Conventional magnetron sputtering

Once base pressure has reached, the sputtering process was started. Depending on the sputtering projectile used, 10 sccm (standard cubic centimetre) of process gas is added to the chamber. The addition of gas increases the pressure in the vacuum chamber by approximately one to two orders of magnitude. The pressure does not adjust directly, so it takes 5 min from the start of the gas supply for the working pressure to be reached. This lies in the range of 10−4 to 10−3 mbar. After the gas flow is turned on, the DC generator for MS is started. As the whole process is power controlled, only the power at which the process is to take place is set on the generator. Both the current and the target voltage are derived from this. As soon as the generator is switched on, the power is regulated to 50 watts. After 5 min, the power is increased by 25 watts to 75 watts and again held constant for another 5 min. This sequence is repeated until the process reaches a power of 200 watts. The increase in power of 25 watts is arbitrary, so that the behaviour of the deposition rate in dependence to a constant increase in power can be studied in an orderly fashion. Finally, the generator is switched off and the gas supply is set to 0 via the mass flow controller. The running recording programs are also terminated. For the 10 sccm argon variants, three consecutive runs each are performed with a 15 min pause between each run. During this time, the generator and the gas flow are set to 0.

- Hot Target Sputtering

To ensure the comparability for determining the sputtering behaviour of the conventional MS and HTS, the same parameters were applied. Here, the increase in sputtering power is performed in steps of 25 W as well. Between the experiments, a cooling phase of 30 min was guaranteed to provide the same initial target temperature for each experimental run. Further experiments were carried out to determine whether a steady state of the deposition rate can be reached with a certain parameter window to produce a constant quality and thickness of deposited layers of lithium with a constant deposition rate after the pre-sputtering time has passed. Hence, the ideal pre-sputtering time for removing oxidized material and melting the target was also subject of the investigation, the same as the reproducibility of deposited layer thicknesses over certain sputtering times. For determining the necessary pre-sputtering time and the transition of the process to a steady state, sputter experiments with a duration of 45 min were carried out with a constant power of 135 W. Since the production costs of metallic lithium foil increase considerably with decreasing layer thickness, and layers < 10 μm in particular are difficult to realize with conventional rolling processes, this method is suitable for producing ultra-thin layers in the range of 1 μm–10 μm. For this purpose, different layer thicknesses are deposited and examined for different electrochemical properties. The thin layers produced are compared with commercial lithium foil with a layer thickness of 20 μm. Table 2 shows the experimental schedule for the stated investigations of the stabilization of the process.

Table 2.

Experimental schedule for the deposition of lithium metal.

- Cell assembly

Cell assembly takes place in a double-coupled M-Line inert gas complete system glovebox from GS GLOVEBOX Systemtechnik and is purged with 99.999 per cent purity argon from Linde. In addition to a lithium iron phosphate (LFP) cathode, the ASSB reference cells have a polyethylene oxide (PEO)-based solid-state electrolyte supplied by Dumont. LiTFSI is used as the conducting salt within the solid electrolyte. The reference components are manufactured as referenced in [36] and in two different ways. One uses metallic lithium anodes with a thickness of 10 μm deposited on copper foil by the HTS process. The other uses lithium foil from Goodfellow with a thickness of 500 μm as the reference anode. The ASSB reference cells produced are assembled into a CR2032 button cell with corresponding components such as bottom and top cases, spacers (500 µm) and wave springs from PiKEM. The electrodes (14 mm) and separators (16 mm) are stamped out using a specially designed laboratory press, operated by a hydraulic single piston hand pump type 4601.51000.330 from FKW-GmbH with a maximum force of 150 kN. To crimp the individual components into a complete button cell, a pneumatic crimper MSK-PN110-S from MTI Corporation is used, applying 7.5 bar for more than three seconds. Li‖Li half cells were manufactured in the same way as the ASSB reference button cells, using the CR2032 button cell format. In addition to sputtered electrodes with different layer thicknesses (2 µm, 3 µm, 5 µm, 10 µm), Whatman glass fibre filters GF/C from Cytiva are used as separators and LiPF6 in EC:EMC (30:70, wt%) from E-Lyte Innovations as electrolyte. One of two 500 μm spacers is placed inside. The die-cut substrate piece is positioned on top with the coated side facing up. This is followed by a double layer separator. In two steps, 75 μL of electrolyte is pipetted onto each layer using an Eppendorf pipette, so that the cell system contains 150 μL of electrolyte. The counter electrode is then placed on the separator with the coated side facing the separator. The second spacer, a tension spring and the top cover are placed on the cell stack and aligned on the crimper.

The BioLogics VMP300 potentiostat and associated EC-Lab V11.43 battery test software were used for electrochemical analysis. The Memmert IPP55 was used as a temperature control cabinet to monitor the ambient temperature. In order to demonstrate a proof-of-concept for HTS for the production of functional LMAs, the cells were cycled and a C-rate test was carried out after cell construction. This was performed by cycling both cell types at different C-rates. A total of 16 cycles was performed per ASSB cell. The first six and last four cycles were charged and discharged at 1C. Cycles seven to nine were tested at 2C and cycles ten to twelve at 5C. The intention here was to investigate whether the self-produced LMAs would function and perform similarly to a purchased component, without making any demands on long-term cyclization. Looking at similar systems in the literature with the same materials and components, discharge capacities of up to 140 mAh g−1 are achieved with pouch cells, which decrease to 70–50 mAh g−1 at an increased C-rate [36]. To evaluate the electrochemical stability of the sputtered LMAs and identify conditions that promote dendrite formation, the critical current density (CCD) was determined using symmetric Li‖Li cells. In this method, lithium is cyclically plated and stripped at incrementally increasing current densities while monitoring the cell voltage response. The cabinet temperature was kept constant at 25 °C throughout the cell test. The testing was performed with a constant current in relation to the anode surface. For this purpose, the required currents for the respective current densities to be measured were calculated in advance. The currents were applied alternately to the cells, meaning that the battery cells were first charged for 30 min and then discharged for 30 min. This cycle was repeated a total of five times per current density. The measurement was carried out up to a maximum current density of 3 mA/cm2.

4. Discussion

This section presents the results of the investigation of the sputtering behaviour in comparison with conventional MS and HTS, as well as the pre-sputtering time required. The stabilization of the process and its reproducibility, as well as the ability of the resulting lithium layer to function as an LMA in an ASSB cell, are also shown in the form of a C-rate test.

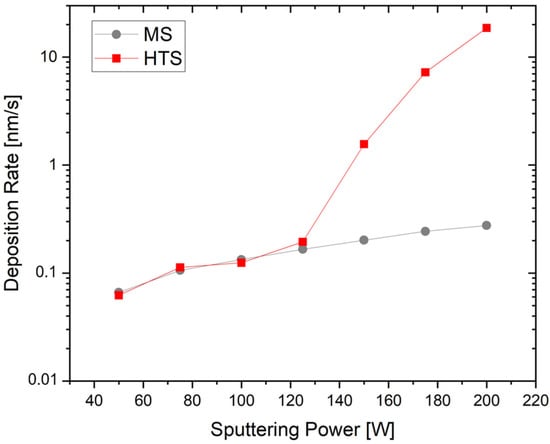

For both conventional MS and HTS, the deposition rate is plotted against the sputtering power in Figure 3. It can be seen that an increase in the sputter power of 25 W also resulted in an increase in the deposition rate for both processes. For conventional MS, the sputter rate increases approximately linearly with power, reaching a maximum of 0.32 nm/s at 200 W. For HTS, the deposition rate is similar to the conventional process up to 125 W and starts to lose its linear character at higher power. The maximum at 200 W is 22.5 nm/s. The direct comparison of the MS and HTS processes clearly shows how strongly the deposition rate increases in the HTS process due to the additional evaporation. The increased power causes the target to melt, resulting in the sputtering process being superimposed with the evaporation of the lithium, which leads to a rapid increase in the deposition rate. The rates observed in these experiments reach values that are almost up to two orders of magnitude higher than the rates from the MS processes.

Figure 3.

Increase in deposition rate over sputtering power for MS and HTS.

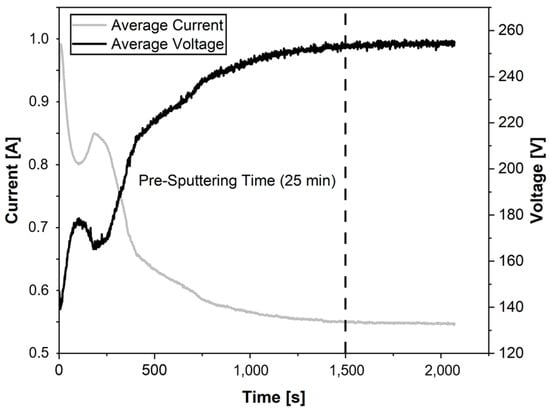

As part of further experimental investigations towards process stabilization, sputtering processes with a duration of 45 min were carried out. The current and voltage curves during the process are plotted in Figure 4. The curves are horizontally mirrored because the sputtering process takes place at constant power (135 W). At the start of the process, a high current and therefore a low voltage is applied to the target. This initially drops before reaching a local minimum after a sputtering time of about 200 s. The current then rises again until it reaches a local minimum. The current then increases again until a local maximum is reached after a coating time of about 250 s. From this point on, the current intensity decreases. This process is similar to a negative exponential growth. This behaviour is mirrored horizontally for the voltage curve, since the power supply is operated in constant power mode; therefore, the average voltage and current are not manually controlled but automatically adjust during the process to maintain the set power. From a sputtering time of about 1500 s (25 min), the current and voltage curves change only slightly. From this point on, both curves are approximately parallel. The average current in this range is about 540 mA, while the average voltage reaches a value of about 250 V. The high currents and low voltages at the beginning of the process indicate a passivation layer on the target surface, since, instead of target atoms, more secondary electrons are released from the target surface, thus increasing the number of electrons within the applied electric field. As the process starts, the ceramic passivation is removed atom by atom. This causes the current to decrease as fewer secondary electrons are released from the target. On this basis, the time for pre-sputtering the target is set at 25 min for the further experiments, as a constant behaviour of the current and voltage can be seen from 1500 s onwards. It can be assumed that the sputtering process is stable from this point on.

Figure 4.

Investigation of the pre-sputtering time and process stabilization through current and voltage.

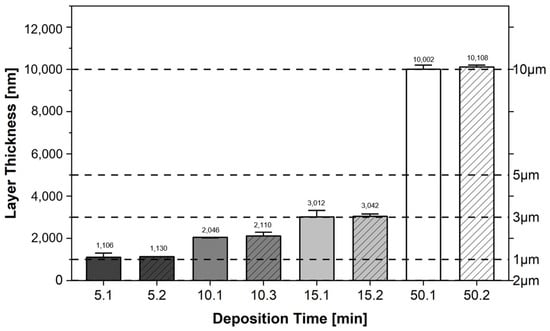

To further investigate the process stability, the resulting metallic lithium coatings produced are measured using a profilometer. The coatings are applied immediately one after the other, but not before a sputtering time of 25 min, so that two coatings are produced independently of each other. The first coating has a pre-sputtering time of 25 min. The second coating has a sputtering time of 25 min plus the time of the previous coating. Figure 5 shows the measured average coating thicknesses in the form of a bar chart, measured with DektakXT (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA). On the x-axis, the coating duration is indicated, followed by the coating sequence. In addition to the measured average coating thicknesses, which are given in nanometres, additional reference lines for different micrometre intervals are shown. It can be seen that for the same deposition time there is little variation in the film thickness. It can also be seen that the film thickness increases by approximately 1 μm for every 5 min of deposition time.

Figure 5.

Average coating thicknesses for coating times of 5 min, 10 min, 15 min and 50 min.

The averaged coating thicknesses of the substrates coated with lithium result in different coating rates in relation to the respective coating thicknesses and coating times. The averaged coating rate across all processes is 209.68 nm/min. This results in a linear relationship between the coating time and the growing layer thickness. The stabilization of the process is successfully achieved with the chosen parameters.

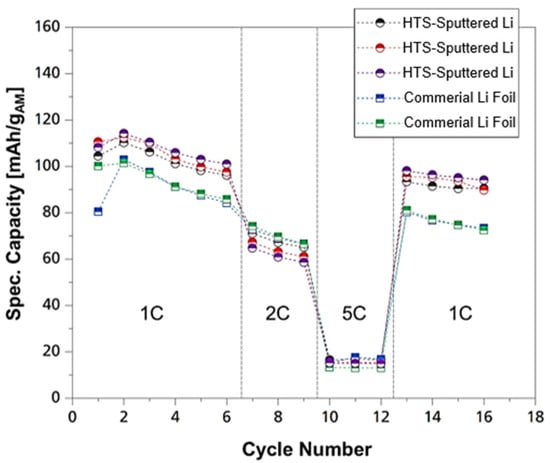

After the stabilization of the process was completed, LMAs with a layer thickness of 10 µm were produced and processed into cells, as described under Section 3. The cells with 500 µm LMAs served as a reference. In order to test the suitability of the process for the production of anodes for ASSBs and to identify how they behave in comparison to commercially acquired material, the performance was analyzed in relation to the specific capacity. Hence, the built PEO-based ASSB cells with the HTS-deposited LMAs and the reference cell were subjected to a C-rate test, showing the characteristics of the specific capacities at different C-rates, as illustrated in Figure 6. A C-rate test was used to evaluate battery performance by charging and discharging the cell at defined rates relative to its nominal capacity. The purpose was to assess capacity, efficiency and voltage behaviour under different current loads, providing insight into the battery’s rate capability and suitability for practical operating conditions.

Figure 6.

Specific capacity of the ASSB cells with 10 µm lithium (HTS) and 500 µm lithium anode.

Both anode types show a continuous decrease in the specific capacity at 1C with every cycle. This behaviour can be observed during the first C1 as well as during the second C1 segment. This may indicate irreversible deposition of lithium in the form of “dead” lithium. At a C5 rate, a loss of specific capacity was not observed on either ASSB type. The improved cycling behaviour may be due to the high currents and current densities resulting from the higher C-rates, as less lithium is irreversibly deposited. However, high C-rates reduce the usable specific capacity, which is why the individual capacities of lower C-rates reach higher values. It can also be seen from the C1 segments that the specific capacities of the sputtered LMAs performed even better than the specific capacities of the ASSB variants with a metallic lithium foil as the anode. For the cycles with a C-rate of two, however, it can be seen that the specific capacities of the lithium foils dominate. Yet, this difference is only marginal. The initial discharge capacity of approximately 110 mAh g−1 is not quite as high as the literature values of 140 mAh g−1, but the comparison shows that the anodes produced by HTS could be used functionally in full cells. A proof-of-concept for the HTS process for the production of LMAs has thus been successfully achieved. Furthermore, we have conducted electrical impedance spectroscopy for symmetrical cells with the sputtered anodes with different thicknesses against Li, to ultimately evaluate the resistances with regard to the layer thickness of the lithium metal anodes. The evaluation showed an advantageous working window with anode thicknesses of 5–10 µm across the impedances.

5. Conclusions

When it comes to the general comparison of different processes for the production of thin LMAs, it is demonstrated that thin-film processes, such as PVD, offer a high degree of flexibility in terms of the precise adjustability of the layer thickness, which is not limited even under 10 µm. However, if you look at the deposition rates of conventional MS processes, you can see that an industrial realization of the production of LMAs is questionable, even if low layer thicknesses can be achieved. By using the HTS process and the support of thermal evaporation, rates can be generated that could enable the industrialization of the process. Conventional MS processes are known for their stability and precise process control, which first had to be proven with the HTS and the respective innovative process execution. The investigation of the influencing parameters showed that reproducible layer production is possible. With regard to the suitability of using HTS for the production of LMAs for ASSBs, the first thing to be noted is that the components produced can match the reference with purchased lithium foil in terms of the C-rate test. The curves of the specific capacities show that higher specific capacities can be achieved here with the thinner, sputtered layers at 1C with a maximum capacity of ≈110 mAh g−1. The loss of specific capacity here is possibly due to irreversible lithium deposition. However, since the specific capacity of the sputtered anodes is higher than that of the reference foil and remains above that even after continuous cycling at 1C, it can be assumed that the sputtered anodes in the ASSB cells exhibit improved reversible lithium plating. With regard to the CCD measurements, it can be seen that lithium layers can be used for electrochemical investigations. The curves indicate the deposition of “dead” lithium in dendrite form and increasing pitting at higher current densities for the sputtered LMAs. Further investigations are necessary to demonstrate or verify a correlation between the amount of metallic lithium and the critical current density. In order to better understand the possible mechanisms and, e.g., long-term cycling tests, further electrochemical and post mortem characterizations must follow. Initially, the focus here was only on a proof-of-concept for the initial functionality of the sputtered LMAs.

Overall, it was shown that the LMA manufactured by HTS is suitable for ASSBs. Further aspects relating to the process (e.g., target temperature measurement, investigation of the relationship between sputtering and evaporation) and relating to product characterization (e.g., morphology, uniformity of layer thickness over larger areas) as well as further evaluation of the process–structure–property relationship will be the subject of further studies. The application is further to be continued on a pilot scale by scaling the process. Although HTS demonstrates industrial potential, several challenges must be addressed for scaled production. Target utilization is limited in conventional magnetron sputtering due to racetrack erosion; however, partial melting of the target during HTS may modify the erosion behaviour and enable more uniform target consumption. Equipment compatibility remains a challenge, as HTS requires lithium-compatible vacuum systems, plasma sources that differ from conventional lithium foil rolling, while continuous plasma operation and vacuum pumping may increase energy consumption. These challenges could be mitigated by optimized target designs to improve utilization, the development of lithium-compatible large-area or roll-to-roll sputtering systems, and process integration strategies that enhance throughput and reduce operational costs. Finally, it can be noted that the process is not only suitable for the production of LMAs, but can also be transferred to other applications due to the general flexibility in material selection (low melting materials). For example, the process can be used for pre-lithiation or pre-sodiation, or for the production of silicon or sodium anodes for alternative battery technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.D., M.K., J.B., J.J. and T.N.; methodology, N.D., M.K., J.B., J.J. and T.N.; validation, N.D., M.K., J.B., J.J., T.N. and S.Z.; investigation, N.D., M.K., J.B., J.J. and T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.D.; writing—review and editing, N.D., M.K., T.N. and S.Z.; visualization, N.D. and M.K.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, N.D., J.J. and T.N.; funding acquisition, S.Z. and N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank the German Federal Ministry of Research and Education for funding the Projects BiSSFest (03XP0412F) and PolySafe (03XP0408D), same as the Fraunhofer Gesellschaft and the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture for funding the project MaLiFest (11–76251-99-2/17 (ZN3402)).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LIB | Lithium-Ion Battery |

| LLZO | Lithium Lanthanum Zirconium Oxide |

| LMA | Lithium Metal Anode |

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| ASSB | All-Solid-State-Battery |

| SSE | Solid-State-Electrolyte |

| PVD | Physical Vapour Deposition |

| HTS | Hot Target Sputtering |

| MS | Magnetron Sputtering |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| PEO | Polyethylene Oxide |

References

- Nzereogu, P.U.; Omah, A.D.; Ezema, F.I.; Iwuoha, E.I.; Nwanya, A.C. Anode materials for lithium-ion batteries: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 9, 100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Ma, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhu, L.; Zhang, X. Growth of lithium-indium dendrites in all-solid-state lithium-based batteries with sulfide electrolytes. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Zheng, Y.; Cui, Z.; Tao, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, W. Recent progress of functional separators in dendrite inhibition for lithium metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Lou, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Kakar, A.; Emley, B.; Ai, Q.; Guo, H.; Liang, Y.; Lou, J.; et al. Current status and future directions of all-solid-state batteries with lithium metal anodes, sulfide electrolytes, and layered transition metal oxide cathodes. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106081. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, X.; Guo, R.; Zhai, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, F.; Wu, C.; Bai, Y. Protecting Lithium Metal Anodes in Solid-State Batteries. Electrochem. Energy Rev. 2024, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Luo, J.; Sun, Q.; Yang, X.; Li, R.; Sun, X. Recent progress on solid-state hybrid electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 21, 308–334. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, W.; Luo, W.; Huang, Y. Less is more: A perspective on thinning lithium metal towards high-energy-density rechargeable lithium batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2023, 52, 2553–2572. [Google Scholar]

- Heimes, H.H.; Kampker, A.; Vom Hemdt, A.; Schön, C.; Michaelis, S.; Rahimzei, E. Produktion Einer All-Solid-State-Batteriezelle, 1st ed.; PEM der RWTH Aachen; VDMA: Aachen, Gemany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, J.; Günther, T.; Knoche, T.; Vieider, C.; Köhler, L.; Just, A.; Keller, M.; Passerini, S.; Reinhart, G. All-solid-state lithium-ion and lithium metal batteries—Paving the way to large-scale production. J. Power Sources 2018, 382, 160–175. [Google Scholar]

- American Chemical Society; Division of Industrial. Handling and Uses of the Alkali Metals: A Collection of Papers Comprising the Symposium on Handling and Uses of the Alkali Metals. In Proceedings of the 129th Meeting of the American Chemical Society, Dallas, TX, USA, 8–13 April 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, Z.; Lin, D.; Zhao, J.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, K.; Tao, X.; et al. Composite lithium metal anode by melt infusion of lithium into a 3D conducting scaffold with lithiophilic coating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 2862–2867. [Google Scholar]

- Neudecker, B.J.; Dudney, N.J.; Bates, J.B. “Lithium-Free” Thin-Film Battery with In Situ Plated Li Anode. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2000, 147, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behringer, U.; Gärtner, H.; Grün, R.; Kienel, G.; Knepper, M.; Lugscheider, E.; Oechsner, H.; Wahl, G.; Waldorf, J.; Wolf, G.K.; et al. Vakuumbeschichtung 2; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Schultrich, B. Beschichtungsverfahren: Teil 1—Physikalische Dampfphasenabscheidung. VIP 2006, 18, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, K.; Koyama, H. Magnetron sputtering of liquid tin: Comparison with solid tin. Appl. Phys. Express 2018, 11, 36201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coventry, M.D.; Allain, J.P.; Ruzic, D.N. Temperature dependence of liquid Sn sputtering by low-energy He+ and D+ bombardment. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004, 335, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Borduleva, A.O.; Yuryeva, A.V.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Lančok, J.; Bulíř, J.; Drahokoupil, J.; Klimša, L.; Kopeček, J.; Fekete, L.; et al. Features of copper coatings growth at high-rate deposition using magnetron sputtering systems with a liquid metal target. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 324, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Yurjeva, A.V.; Sadykova, I. Energy and substance transfer in magnetron sputtering systems with liquid-phase target. Vacuum 2016, 124, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Yuryeva, A.V. Magnetron deposition of coatings with evaporation of the target. Tech. Phys. 2015, 60, 1790–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Yuryeva, A.V. Thermal Processes and Emission of Atoms from the Liquid Phase Target Surface of a Magnetron Sputtering System. Russ. Phys. J. 2015, 58, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Yuryeva, A.V.; Shabunin, A.S.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Sidelev, D.V. The role of thermal processes and target evaporation in formation of self-sputtering mode for copper magnetron sputtering. Vacuum 2018, 152, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleykher, G.A.; Yuryeva, A.V.; Shabunin, A.S.; Sidelev, D.V.; Grudinin, V.A.; Yuryev, Y. The properties of Cu films deposited by high rate magnetron sputtering from a liquid target. Vacuum 2019, 169, 108914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuryeva, A.V.; Shabunin, A.S.; Korzhenko, D.V.; Korneva, O.S.; Nikolaev, M.V. Effect of material of the crucible on operation of magnetron sputtering system with liquid-phase target. Vacuum 2017, 141, 135–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.P.; Ruzic, D.N.; Hendricks, M.R. D, He and Li sputtering of liquid eutectic Sn–Li. J. Nucl. Mater. 2001, 290, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.P.; Ruzic, D.N.; Hendricks, M.R. Measurements and modeling of D, He and Li sputtering of liquid lithium. J. Nucl. Mater. 2001, 290, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumova, Y.Y.; Logacheva, V.A.; Khoviv, A.M.; Solodukha, A.M. Phase Composition and Dielectric Properties of Thin Films Produced by Annealing Sn/Pb/Ti/Si and Pb/Sn/Ti/Si Heterostructures. Inorg. Mater. 2004, 40, 1079–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, J.P.; Ruzic, D.N.; Alman, D.A.; Coventry, M.D. A model for ion-bombardment induced erosion enhancement with target temperature in liquid lithium. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2005, 239, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borduleva, A.O.; Bleykher, G.A.; Sidelev, D.V.; Krivobokov, V.P. Magnetron sputtering with hot solid target: Thermal processes and erosion. Acta Polytech 2016, 56, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidelev, D.V.; Yuryeva, A.V.; Krivobokov, V.P.; Shabunin, A.S.; Syrtanov, M.S.; Koishybayeva, Z. Aluminum films deposition by magnetron sputtering systems: Influence of target state and pulsing unit. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 741, 12193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaziev, A.V.; Tumarkin, A.V.; Leonova, K.A.; Kolodko, D.V.; Kharkov, M.M.; Ageychenkov, D.G. Discharge parameters and plasma characterization in a dc magnetron with liquid Cu target. Vacuum 2018, 156, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, M.; Moiseev, K.; Nazarenko, A.; Luchnikov, P.; Dalskaya, G.; Katakhova, N. Technological Features of the Thick Tin Film Deposition by with Magnetron Sputtering Form Liquid-Phase Target. KEM 2018, 781, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mochalov, S.E.; Nurgaliev, A.R.; Kuzmina, E.V.; Ivanov, A.L.; Kolosnitsyn, V.S. Specifics of magnetron sputtering of lithium from liquid-phase target. Vacuum 2019, 168, 108816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhou, D.; Li, M.; Wang, C.; Wei, W.; Liu, G.; Jiang, M.; Fan, W.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, X. Surface Engineered Li Metal Anode for All-Solid-State Lithium Metal Batteries with High Capacity. ChemElectroChem 2021, 8, 386–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Ma, Z.; Wang, D.; Yang, S.; Fu, Z. Functional multilayer solid electrolyte films for lithium dendrite suppression. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2022, 121, 223901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lin, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Han, J.; Wu, D.; Kang, F.; Yang, Q.-H.; Lv, W. A Protective Layer for Lithium Metal Anode: Why and How. Small Methods 2021, 5, e2001035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmers, L.; Froböse, L.; Friedrich, K.; Steffens, M.; Kern, D.; Michalowski, P.; Kwade, A. Sustainable Solvent-Free Production and Resulting Performance of Polymer Electrolyte-Based All-Solid-State Battery Electrodes. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2000923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.