Abstract

This study proposes a methodological approach to reinterpret the Outstanding Universal Value (OUV) of the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique, inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List since 1991 under criteria IV and VI. In view of emerging challenges that threaten the heritage-making process—namely, progressive interventions in the built fabric—a methodology of interrelated reading is presented, grounded in a critical and participatory perspective centered on the local community. This methodological structure is operationalized through an interrelated reading model that combines architectural, constructive and intangible layers within a multi-scalar analytical matrix. This approach is based on three interdependent dimensions: (i) material and immaterial; (ii) symbolic and identity-related; and (iii) functional and sustainable. The theoretical model developed, supported by the participation of multiple stakeholders, demonstrates that small adaptations—compatible with cultural values and local actors’ interpretations—can strengthen the recognition of the value of built heritage and foster sustainable human development. Given the existing typological diversity, the study concludes that it is essential to adapt the model of OUV reinterpretation to each specific context, acknowledging the plurality of possible solutions and promoting a balanced integration of material and immaterial values without compromising existing cultural significance.

1. Introduction

The Island of Mozambique, located on the east coast of Africa, is one of the continent’s oldest urban settlements [1]. As a crossroads of African, Asian, and European influences, it synthesizes knowledge of architectural and construction practices and processes. This sociocultural convergence is reflected in its inscription on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1991 under criteria IV and VI [2].

The insular part of the Island is composed of two distinct yet complementary zones. The northern area, known as the “stone and lime town”, is defined by coral-stone construction techniques. The southern area, the “macuti town”, is characterized by the use of more perishable materials such as earth, mangrove sticks, or wattle-and-daub, and palm leaves. The southern zone also served as the extraction site for the stone used in the construction of the “stone and lime town” [3]. In the local Emakhuwa language, “macuti” refers to the coconut palm leaf traditionally used for roofing [4].

The built heritage of the Island of Mozambique, understood as the outcome of historical, social, and technical processes, is more than a collection of preserved physical structures over time. The Island embodies the expression of cultural practices, everyday uses, and symbolic meanings that provide identity and a sense of belonging to the communities that inhabit it [5]. Nevertheless, for a long time, heritage approaches have primarily focused on material aspects such as wall types, roofing materials, and architectural elements (e.g., stone corner and frieze), often neglecting the intangible layers that sustain the lived experience of the place [5].

The growing recognition of intangible cultural heritage, promoted by international organizations including UNESCO [6] and ICOMOS [7,8], as well as by national Mozambican institutions such as the Ministry of Education and Culture and Mozambique Island Conservation Office (Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique, GACIM) [9], has raised critical questions about “traditional interpretations” proposing more integrated methodologies.

In this context, Alcolete [10] proposes for the Island of Mozambique an integrated approach that allows for the understanding of heritage attributes through the interplay of architectural and constructive variables, while also incorporating intangible symbolic dimensions, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Macuti house typology on the Island of Mozambique. Above: wattle-and-daub construction with a traditional Swahili-style palm-thatch roof (macuti). Below: veranda of a macuti house, a characteristic feature usually located at the front, functioning as a transitional space between public and private spheres, and as a place for social gathering and rest.

Building on the values and attributes proposed by Brand [11] and further developed by Kuipers and Jonge [12], where the method is structured to identify and classify the typical architectural and constructive characteristics of the building in its current state, making a systematic interpretation of these values and attributes for its safeguarding, this study intends to expand the analysis to the realm of cultural practices, highlighting the central role of the inhabitants of the Island as key actors in the heritage-making process. The case of the streets of “macuti town”, transformed into spaces for prayer, community celebration, and economic activities, provides a paradigmatic example of this relationship between the material and the symbolic.

Thus, this article aims to explore a participatory and integrated methodology that emphasizes the articulation between physical and social aspects, as well as the material and symbolic dimensions of the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique. Its central objective is to enhance the value of this heritage through the application of such an approach. Moreover, this work was part of a dynamic process of applied research carried out in partnership between Lúrio University (Mozambique), the University of Coimbra (Portugal), and Eduardo Mondlane University (Mozambique), reinforcing the interdisciplinary and transnational dimension of the study.

Despite the methodological contributions previously outlined, a theoretical framework is required to overcome the inconsistencies that emerge in the critical reinterpretation of the OUV in the Island of Mozambique. The reflection presented here understands the OUV as a relational and multiscale system of tangible and intangible values, shaped by practices, meanings, and materialities that are continually reconfigured through cumulative historical, sociocultural, and technical processes. Consequently, the focus shifts from monumentality to the centrality of communities in the production and legitimization of heritage values. By conceiving heritage as a living, performative, and continuously (re)produced phenomenon, this perspective enriches the understanding of heritage dynamics. At the same time, it provides a more robust theoretical foundation for management models capable of integrating the diverse agents, temporalities, and regimes of signification involved in contemporary heritage-making processes.

2. Materials and Methods

This research is framed within the PhD thesis of the Doctoral Program in Heritages of Portuguese Influence at the University of Coimbra—III/CES, entitled “Safeguarding and Valuing the Built Heritage of the Island of Mozambique. Contributions to a Sustainable Intervention Strategy” [10].

Within this framework, the first step of this research was the development of an initiative entitled “Oficina Muhipiti: Rediscovering the Built Heritage”, designed to stimulate the rediscovery and appreciation of the Island’s built heritage by promoting the direct involvement of local communities in the analysis and characterization of buildings. The initiative brought together multidisciplinary teams from Mozambique and Portugal, including professors, students, public institutions, community associations, professionals, residents, and researchers.

In Mozambique, technicians from the Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique (GACIM, Mozambique Island Conservation Office) played a central role, assisting in the preliminary selection of representative case studies. This selection followed technical-scientific criteria that prioritized, on the one hand, the state of conservation of the buildings (assessed according to their degree of deterioration) and, on the other, their urban and landscape integration—namely, their relationship with historical ensembles and their typological representativeness within the local context. Additionally, the Municipality of the Island of Mozambique not only provided access to several state-owned buildings but also offered logistical support. The Instituto Médio Politécnico da Ilha de Moçambique (IMPIM, Polytechnic Institute of Mozambique Island) contributed with its extensive knowledge of local construction techniques and building rehabilitation practices. Moreover, local students from IMPIM and from the Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas da UniLúrio (Faculty of Social and Human Sciences, UniLúrio) and Faculdade de Arquitectura e Planeamento Físico (Faculty of Architecture and Physical Planning, UniLúrio) acted as co-researchers, developing territorial-reading skills and engaging in experimental fieldwork. Finally, the local community and participants of other local organizations, contributed with empirical knowledge, memories, and lived uses of the built environment.

From Portugal, researchers from different fields—architecture, civil engineering, and geological engineering—provided the theoretical-methodological framework and mediated between academic epistemologies and local practices, deepening the interpretation of heritage meanings, which, in the present case, converged with the thesis previously referenced.

Over the course of three days in January 2022, the multidisciplinary teams worked collaboratively in the field, observing and recording the characteristics of 72 preselected buildings (40 in the “macuti town” and 32 in the “stone and lime town”) chosen according to their representative characteristics. Community participation was operationalized through participatory mapping, interpretative sketches produced by residents, joint façade readings, the identification of symbolic uses, and the public validation of preliminary results. To avoid conceptual ambiguities, the “Oficina” systematically adopted the terms “heritage meanings” and “cultural attributes,” in line with UNESCO and ICOMOS, reserving “value” for non-financial contexts. This choice strengthened conceptual rigor and intercultural clarity. The resulting materials—maps, photographic records, sketches, and narratives—formed a visual and interpretive corpus essential for understanding both the physical and lived dimensions of the territory. These observations were later analyzed, discussed, and synthesized into a report that was returned both to the community and to the participating institutions, reinforcing the collective and participatory nature of the process.

Altogether, this collaborative process helped to consolidate an integrated approach to conservation. The joint work of residents and researchers showed that interpreting heritage requires a multiscale perspective—one that relates material attributes, construction systems, spatial morphologies, and architectural elements with social practices, community uses, and symbolic frameworks that shape the experience of place. This shared analytical effort created a platform for cultural negotiation, strengthening heritage interpretation and supporting a critical reassessment of the OUV by recognizing heritage as a living, dynamic, and co-produced phenomenon.

2.1. Application of the Multi-Layered System

Understanding the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique benefits from approaches that conceive it not as a homogeneous and static object, but as a system of differentiated layers, each with its own rhythms of transformation, agents, and forms of meaning. This idea, reaffirmed daily on the Island, carries direct methodological and normative implications, shifting the focus from the mere isolation of material elements to the interpretation of the interrelationships between materiality, use, meaning, and collective memory.

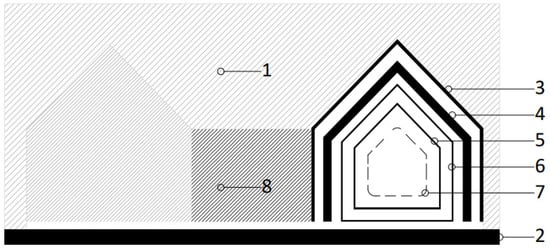

Thus, to clarify the relationship between theoretical foundations and operational procedures, the multilayer model was applied in two complementary phases. First the identification phase consisted in the transformation of these layers into observable parameters, systematically collected in the field and organized within a two-dimensional grid combining architectural and construction indicators (Table 1). In the conceptual phase—resulting from a critical adaptation of Brand’s model—the analytical layers were established (Figure 2—context, site, outer shell, structure, spatial organization, services, things, and spirit of place).

Table 1.

Systematic and interconnected interpretation of the values and attributes associated with the constructive components of the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique.

Figure 2.

Diagram of “Brand layers”, represented by Kuipers and Jonge [12] (adapted from Alcolete [10]): 1—Context/Surroundings; 2—Site; 3—Exterior cladding; 4—Structure; 5—Spatial organization; 6—Services; 7—Objects; 8—Spirit of place.

2.1.1. The Identification Phases

Starting from the dominant theoretical approaches in the field of heritage and from international normative frameworks—particularly those of ICOMOS and the World Heritage Convention—this study explores two complementary perspectives: the reading of physical attributes and the heritage values associated with the built environment of the Island of Mozambique, with emphasis on the constructive matrix of the “stone and lime town” and the “macuti town”. These two architectural matrices coexist within a unique insular territory whose richness, as noted by Leite [13], stems from centuries of cultural encounters, technical adaptations, and deeply rooted social practices.

The first perspective involved the local community and took as its starting point a pedagogical and scientific model, grounded in a systematic technical-constructive analysis, structured around the physical components of the built environment, including walls, roofs, floors, openings, and distinctive elements. This reading was integrated into the framework of heritage values defined by the legal instrument Decree No. 55/2016 of 28 November [14]: (i) historical-political; (ii) archeological; (iii) architectural; (iv) artistic; (v) landscape; (vi) sociocultural; (vii) environmental; and (viii) urbanistic. According to Alcolete [10], in the context of the Island, a more integrated reading of the built environment requires incorporating both symbolic and use values. The physical matrix reveals building systems as carriers of values—not merely as technical solutions, but as tangible and intangible expressions of local knowledge, environmental adaptations, and cultural identities.

The second perspective proposes a critical and comparative reading of two dominant constructive logics, one from the “stone and lime town” and the other from the “macuti town”. The analysis goes beyond the technical-material dimension, highlighting the contrasts and complementarities between two ways of inhabiting, building, and attributing meaning to space. The monumentality and permanence of the “stone and lime town” are set in dynamic dialog with the flexibility, lightness, and cyclical renewal of the “macuti town”. Both typologies express distinct yet equally relevant heritage values, requiring differentiated methodologies of observation and action, adjusted to the spirit of the place and the materials employed.

The initial systematization enabled a structured reading of physical attributes, providing a basis for an operative and integrated approach to the characterization of the Island’s built environment. When morphological, architectural, and constructive data are considered together with the meanings attributed by communities, the mediating role of built elements in the creation of heritage value becomes evident. A stone wall, a wattle-and-daub wall, or a macuti roof cease to be mere technical components and become carriers of memory, identity, and resilience. Following this step, a reading exercise supported by architectural inventories, participatory surveys, and historical document analysis allowed the identification of typologies and construction systems, as well as ongoing transformation processes and the meanings attributed by local communities.

Table 1 synthesizes the articulation of physical, value-related, and symbolic dimensions into five value categories—historical, technical/technological, esthetic, symbolic, and use—and analyzes walls, roofs, floors, openings, and distinctive elements. This matrix provides a solid basis for defining conservation strategies anchored in the local sociocultural reality. In the historical domain, emphasis is placed on the legacy of the colonial period—before Mozambique’s independence in 1975—alongside the persistence of traditional solutions, the Arab influence, and the historical embedding within the urban fabric. In the technical–technological domain, focus is given to the adaptation to the Island’s unique conditions, on the application of vernacular solutions and techniques together with contemporary structural reinforcement, and on climatic strategies such as ventilation and natural light. In turn, esthetic value is identified from structures and volumes, considering also the urban form of the roofs, the decorative modulation of pavements, the proportions of openings, and the ornamental details of singular elements. Damen’s and colleagues research [15] further explores the esthetic, architectural, and constructive attributes included in the list of heritage values of the Island presented by ICOMOS [16]—namely, (i) the consistent use of the same construction techniques; (ii) the consistent use of the same materials; and (iii) the consistent use of the same decorative principles.

The symbolic value, in this case, is expressed through local identity, cycles of renewal, continuity of ceremonial uses, expression of status, and the marking of specific functions, thereby reinforcing the cultural and communal dimension of the built heritage. Finally, the use value refers to functionality and the adequacy to everyday needs: those of habitability, thermal performance, accessibility, communication between spaces, and versatility. Thus, this matrix reveals the complexity and diversity of the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique, demonstrating how its components integrate multiple layers of value that interconnect tradition, innovation, and cultural identity.

The analysis of the constructive systems of the “stone and lime town” and the “macuti town” makes it possible to recognize, more broadly, the complexity and complementarity that characterize the urban fabric of the Island. On the one hand, the former materializes the permanence of historical monumentality and planned urban order, while the latter expresses the vitality of popular construction, rooted in ancestral techniques of high ecological, social, and cultural resilience.

Building on this basis, the central issue focuses on the values and attributes to be maintained, reinforced, or further systematized and recognized, grounded in a methodology that interrelates these very values. For example, an interrelated analysis of the constructive systems of walls and roofs can, in the case of the Island of Mozambique, allow an integrated reading of the heritage values associated with the built fabric. This is particularly visible on the coralline limestone masonry of the “stone and lime town” that provides stability, durability, and historical memory, revealing advanced technical knowledge and an architectural identity shaped by colonial contact and adaptation to the coastal environment. Moreover, according to Wynne-Jones [17], these stone houses correspond to the Swahili housing tradition. By contrast, the wattle-and-daub walls of the “macuti town” express a vernacular constructive logic, resilient and adaptable, marked by the connection to natural cycles and by local knowledge.

In terms of roofing, the reinforced concrete slabs of the “stone and lime town” indicate a process of technological hybridization, in which contemporary solutions rely on robust traditional structures, while the macuti roofs of the “macuti town” bear witness to refined knowledge of natural materials, climatic performance, and cyclical renewal—fundamental values of Swahili culture. Through this duality, it is possible to understand that this may be the path toward strengthening and enhancing the Island’s heritage asset within a comprehensive and systemic perspective. This approach acknowledges the complexity of its forms, functions, and meanings, according to ICOMOS [16], and proposes safeguarding interventions that are more conscious, contextually rooted, and sustainable.

It is important to emphasize that the methodology for studying the value of the built heritage of the Island of Mozambique should be understood as part of an interdependent system, in which each element, however modest or functional it may appear, carries meanings that go beyond its material dimension. This systemic approach makes it possible to understand the built heritage not merely as a set of isolated objects but as a living network of relationships between knowledge, practices, and values, fundamental to underpin conservation policies that are both balanced and culturally rooted.

2.1.2. The Conceptual Phase

The subsequent systematization constitutes a complementary development of the previous approach, oriented toward the goals of the progressive valorization of this heritage asset. The main challenge lies in reconciling conservation, functionality, and performance within a perspective of sustainable safeguarding. Accordingly, a methodology is proposed based on interrelated analysis, which makes it possible to identify the connections between constructive and architectural features.

This analysis is supported by Brand’s theoretical framework of layers [11], which conceives buildings as being composed of different strata, each with its own temporal horizon. This author argues that the ability of a building to “survive” depends on the compatibility among these strata and on their adaptability to the users’ needs over time. Methodologically, the “Brand layers” provide an analytical axis for understanding why some elements change rapidly while others are preserved as identity markers (Figure 2).

Following this line of thought, Kuipers and Jonge [12] develop the notion of multilayer analysis as an operative tool capable of distinguishing the essential characteristics, which require safeguarding, from those that are more permeable to adaptation. This distinction provides a basis for design decisions and intervention criteria that are better adjusted to the complexity of buildings and to their evolution over time.

The cross-analysis of attributes from two layers makes it possible to identify relationships that reinforce certain heritage values, allowing levels of importance to be assigned. This process leads to the hierarchization of relevant elements and provides an objective basis for conservation decisions. Second-order analysis constitutes, in this context, a central challenge, as it relates distinct variables from each set of architectural, constructive, or immaterial parameters, thereby broadening the understanding of the identified attributes. Moreover, this layer process can be based on a two-dimensional matrix, where the vertical axis represents the architectural parameters, such as spatial typology, hierarchy of volumes, formal elements, and stylistic or decorative features. In turn, the horizontal axis arranges the constructive parameters, including materials, construction techniques, structural systems, roofing, finishes, and technical adaptations resulting from maintenance or historical evolution. The crossing of the two dimensions enables the identification of second-order readings; that is, significant relationships between an architectural and a constructive parameter. For example, a macuti roof may be associated with a certain type of veranda or with the internal spatial organization (architectural), evidencing both functional and formal coherence. The analysis of these relationships provides criteria to hierarchize the importance of each element and its relevance for preservation. Unlike strictly typological approaches, which are limited to the individual description of components, this interrelated reading highlights the internal coherence of the building or the urban ensemble. Its contribution lies in showing how the interactions between form and technique constitute the essence of heritage identity, revealing patterns, redundancies, and complementarities that would not be captured by an isolated inventory.

Building on the previously identified layers, the next step consisted of attributing importance to the relationships resulting from second-order reading. The mapping, however, is not limited to the physical and tangible layers of the built heritage, but it also incorporates the intangible layer. This manifests itself in social and cultural practices that give life to space, such as the transformation of streets into places of prayer, community celebrations, or rites of passage. The introduction of the intangible layer is not merely a conceptual exercise, but a practical necessity, since the cultural meaning of places transcends physical forms, residing in everyday practices. In the “macuti town”, for example, the streets are not limited to spaces of circulation. At certain times, they become extensions of the mosques, hosting collective prayers. On other occasions, they are converted into ceremonial spaces associated with weddings, funerals, or initiation rites. These practices demonstrate how the city is experienced beyond its materiality, acquiring meanings that transcend conventional urban functions.

The distinction between physical and social layers should not be understood as a rigid dichotomy (Figure 1). The multilayer model offers, as its main analytical advantage, the capacity to reveal interfaces in which the constructive technique, the architectural form, and the social uses reinforce one another. Recognizing the intangible as a layer implies accepting its fluid and mutable nature. Unlike walls or structures, social practices do not leave lasting physical traces but create collective memories that are essential for the identity of a place. Hence, the analysis of the built heritage requires tools that go beyond simple physical description, while simultaneously considering the complexity of the relationships between architectural, constructive, and, where possible, social and symbolic elements. The interrelated reading can become a methodological tool capable of integrating these dimensions, providing an analytical matrix that organizes data systematically and enables qualitative interpretations.

2.2. Integration of the Intangible Layer into the Interrelated Analysis

In the last decade, the preservation of the Island’s heritage asset has evolved to incorporate the invisible layers, recognizing that cultural value lies not only in the walls, the macuti roofs, or the structures, but also in the lived relationships between the inhabitants and the place. This “invisible layer” refers to practices, memories, rituals, and uses that were not directly expressed in the materiality of the building, but shaped and sustained its cultural meaning. As Smith [18] argues, heritage is not only an objective inheritance but also a social construction—a continuous narrative that assigns value and identity. This approach regards heritage as a living process, in which the users play a central role in its interpretation and preservation.

The incorporation of the intangible layer was integrated through participant observation, interviews, and ethnographic field notes, triangulating community testimonies, allowing the capture and comparison of subjective perceptions through recurrent analytical categories (ritual practices, daily sociability, ceremonial uses of spaces, degree of appropriation). This approach grants the intangible component full analytical status and reveals verifiable correlations between materiality, cultural practices, and identity dynamics. The layer was later incorporated into the matrix as an additional dimension. While the vertical and horizontal axes represent architectural and constructive parameters, a third dimension (or supplementary layer of analysis) can map cultural practices, community events, religious rituals, and everyday uses, creating a conceptual three-dimensional matrix. This integration reveals how intangible practices interact with material elements, reinforcing or transforming the function and meaning of space [12,19]. The Island of Mozambique clearly exemplifies the relevance of the intangible layer. The built heritage, the houses, the fortifications, the mosques, and the streets acquire full meaning only when the daily life of the inhabitants and the cultural uses associated with them are considered. Some manifestations include: (i) prayer spaces in the streets: during periods of religious celebration, certain streets of the “macuti town” become extensions of the mosques, hosting collective prayer practices. This temporary use demonstrates how the spiritual dimension articulates with the urban configuration, influencing perceptions of spatial hierarchy and circulation. (ii) Community ceremonies: weddings, funerals, and initiation rites are frequently held in courtyards, streets, or specific public spaces. Such occasions reinforce social bonds, mark cultural continuity, and attribute meaning to physical spaces. (iii) Traditional economic practices: local trade and artisanal activities are carried out in particular corners of the historic city, maintaining spatial occupation patterns inherited from centuries of urban habitation. These practices shape space dynamically, constituting essential elements for understanding the cultural identity of the neighborhood (Figure 3). Such an example reinforces the idea that the intangible layer is often decisive in justifying the preservation of a place. Physical elements in isolation may lose relevance without the social and symbolic practices that confer meaning upon them.

Figure 3.

Social manifestations in the Island of Mozambique. Choreographies and performative expressions accompanying festivities and religious rituals. Above: Representation of Maulide dance (Credits to Miguel Ferreira). Below: Tufo dance (Credits to Saulo Mabota).

This structured methodological process aims to capture the dynamic interactions between social practices and the physical supports that sustain them, ensuring a more holistic and coherent approach to heritage conservation. To incorporate the intangible layer into the interrelated reading matrix, the proposal involves identifying relevant practices—that is, the systematic documentation of social practices that bring life to urban and built spaces. In the Island of Mozambique, for instance, the use of courtyards for collective cooking, circumcision ceremonies, and Islamic religious festivities constitutes central practices of community life. Once documented, these practices provide the cultural substratum necessary for interrelated reading. Another example can be the use of courtyards for cooking activities, where the arrangement of access and the presence of shading are directly related.

3. Results and Discussion

Although the initial survey covered 72 buildings during the Muhipiti workshops, it is important to clarify that this set functioned as a basis for the construction of an analytical matrix from which typological patterns, construction regularities and sociocultural recurrences emerged. The detailed analysis presented in this article focuses, however, on two representative case studies, one located in the “stone and lime town” (Figure 4) and the other in the “macuti town” (Figure 5). It should also be mentioned that this proposal was largely the result of “Oficinas de Muhipiti: rediscovering the built heritage” and discussed in the PhD thesis [10].

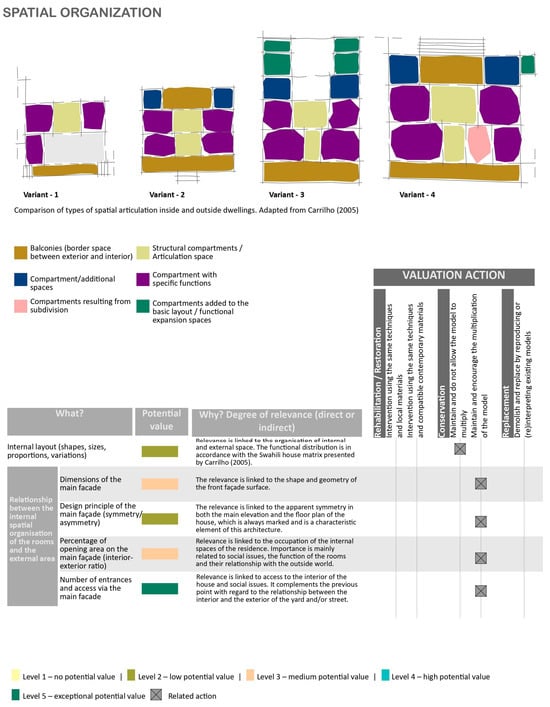

Figure 4.

Illustrations and matrix related with spatial organization (layer 5) of the “stone and lime town”. The potential value was classified in a five-level scale from no potential (1) to exceptional potential (5), nevertheless, not all levels were observed. It is also possible to see the degree of relevance of the value associated with layer 5. Adapted from Alcolete [10].

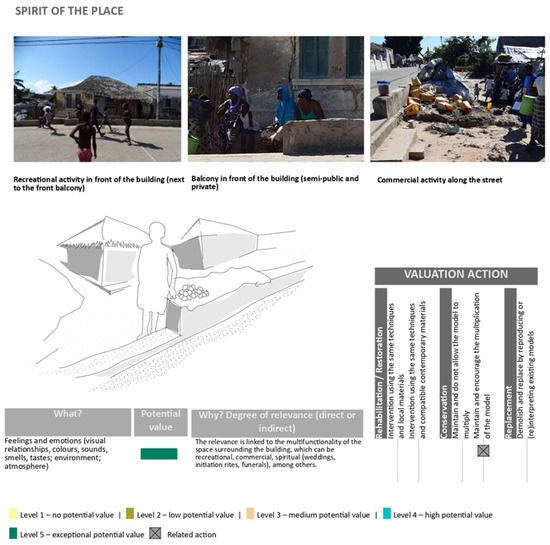

Figure 5.

Illustrations and matrix related with spirit of place (layer 8) of the “macuti town”. It is also possible to see the degree of relevance of the value associated with layer 8. Adapted from Alcolete [10].

To apply the model it is necessary to consider the processes involved by: (i) assessing the coherence between physical elements and their uses (for example, the maintenance of verandas allowing for different uses); (ii) identifying elements for rehabilitation, conservation, or replacement; and (iii) recognizing potential attributes and values of conflict, such as constructive, architectural, or urban interventions that may compromise collective dynamics or distort symbolic meanings.

The model was design to consider both the tangible and intangible layer, since this was the core question of this research. Figure 4 and Figure 5 represent a possible application of the model, considering the spatial organization—tangible—and the spirit of the place—intangible—respectively. The spatial organization relevance lies in the relationship between the arrangement of internal spaces and external areas. It is conceived from the inside out, with the internal function expressed on the façade. The relevance or the spirit of the place is to highlight how feelings and emotions connect to visual relations, colors, sounds, smells, and tastes. It concerns particularly to the distinctive and valued atmosphere of the place.

In case of the spatial organization (Figure 4) the diagrams represent the internal articulation of compartments and their relationship with exterior spaces, using a color-coded scheme to distinguish functional types: border or transitional spaces (balconies), basic structural compartments, specialized rooms, subdivisions, and expansion areas added to the original layout. These variants highlight the diversity of spatial arrangements and the ways in which households adapt, subdivide, or extend their living spaces in response to functional, social, and cultural needs.

The lower section of the figure presents an analytical matrix used to assess the heritage value of spatial attributes. Each attribute—interior layout, façade geometry, symmetry principles, opening ratios, and access points—should be scored by applying a five-point Likert Scale, where level (i) is considered as null potential value (very low), (ii) as reduced potential value (low), (iii) as medium potential value (medium), (iv) as high potential value (high), and (v) as exceptional potential value (very high). The matrix also links each attribute to five valuation actions, divided into three groups: (i) two strategies of rehabilitation and/or restoration; (ii) two strategies of conservation; and (iii) one strategy of replacement. The first, includes intervention using the same local techniques and materials or using the same techniques with compatible contemporary materials. Then, the conservation strategy is based on the principle of maintenance, not allowing either the multiplication of the model or its maintenance and encouragement. Finally, the replacement strategy involves demolition and substitution, either reproducing or reinterpreting the recommended existing models. The degree of relevance (direct or indirect) clarifies how each attribute pays to the significance of the dwelling, whether through its formal and geometric properties, its role in mediating interior–exterior relations, or its implications for social use and patterns of occupation [20]. Altogether, this operationalizes how spatial characteristics inform of the decision-making in heritage management.

The rationale of Figure 5 is similar, although focusing on the spirit of the place, highlighting the everyday practices, social interactions, and sensory atmospheres that shape the spaces. The photographs document different forms of appropriation, including recreational activities in front of façades, social interactions occurring in semi-public balconies, and spontaneous commercial practices along the street. These visual records demonstrate the multifunctionality of the built environment and show how residents continuously activate these spaces through social encounters, routine gestures, and small-scale economic activities. The matrix synthesizes this sensitive dimension—visual relationships, sounds, smells, colors, tastes, and environmental atmospheres. Here, the same Likert scale in 5 levels should be applied to the potential value of this intangible layer. The degree of relevance is in this case linked directly to the multifunctionality of the space surrounding the building, which encompasses recreational, commercial, spiritual, and ceremonial uses. These varied uses reinforce the cultural significance of the area and show how intangible practices are embedded in everyday spatial experience. Finally, and similarly to Figure 4, the valuation table associates the attribute with maintenance but in this case focusing in preserving existing practices, uses, and atmospheric qualities that are essential to safeguard the sociocultural dynamics that constitute the spirit of the place.

Overall, the matrices presented in Figure 4 and Figure 5 demonstrate how local experiences and ambient qualities form an integral part of heritage assessment. It is important to emphasize, however, that this case study was directed toward a more vernacular version, with significant expression but not representative of the Island’s built fabric as a whole; this is why Figure 2 was used to identify each layer for the two case studies. Moreover, statistical analysis was not performed since, at this stage, results are meant to be empirical and are to remain within a more qualitative and interpretative analysis.

The challenge in applying this model consists of testing its potential to determine the constructive and architectural significance, including the intangible dimensions that may assist in decision-making for rehabilitation, restoration, or replacement projects. In other words, it aims to support the notion of the management of change by clearly defining the extent to which attributes should be preserved. Moreover, this model aims to provide a detailed and clear analysis of the relevance of the building’s attributes or characteristics, framed within the broader perspective of the values credited to the built ensemble and the meanings they convey.

It is important to highlight that the strategies presented constitute dynamic components of a continuous process of critical reflection, intended to respond to social and technological transformations and to promote an integrated understanding of the tensions that characterize the values and attributes of the heritage under study. Recognizing the plural nature of the Property and the complexity of the interactions between sociocultural, material, and environmental dimensions, these actions should be framed, according to Milão [21], within a morphological vulnerability assessment framework. This approach is designed to guide conservation practices and support the resilient adaptation of the Island’s urban ensemble.

Even if with a more empirical aspect, the results allow for deeper reinterpretation of the OUV of the Island of Mozambique by demonstrating that the material and immaterial values underlying its inscription on the World Heritage List are continuously (re)produced by the interaction between constructive forms, social practices and symbolic regimes of appropriation of space. In the two case studies analyzed, it was found that apparently strictly architectural components, such as the morphology of houses in “stone and lime town” or the relationship between balconies, patios and circulation spaces in houses in “macuti town”, acquire exceptional value when interpreted in the light of everyday practices, ritual performances and dynamics of local sociability. This reading shows that authenticity and integrity do not derive from simple material persistence, but from the functional and cultural continuity activated by communities. Consequently, OUV should be understood as a relational and procedural quality, reinforcing the need for participatory approaches and inter-relational analytical matrices to guide the evaluation and future management of the site.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the effective preservation of cultural heritage depends on an integrated understanding of material, constructive, and intangible elements, as well as on the active participation of inhabitants as co-creators of heritage value. The interrelated methodology thus constitutes a robust, adaptable, and innovative instrument, capable of guiding conservation decisions that respect both materiality and the cultural life of the place, promoting sustainable and socially legitimate heritage management.

The interrelated reading shows that architectural and constructive elements gain value not only from their antiquity or rarity, but also from the way they are appropriated by the community. For example, a courtyard may be technically relevant for its typology but becomes heritage-significant when it is transformed into a space of conviviality, celebration, or ritual. This reading of the built heritage, when expanded to include the intangible dimension, provides a powerful tool for understanding the complexity of place. The intersection of architectural and constructive parameters reveals the material coherence of the buildings, while the inclusion of social and symbolic practices highlights their cultural vitality. This is clearly observed in the analysis of the “macuti town” that illustrates how seemingly ordinary streets can acquire symbolic and spiritual centrality, functioning as invisible yet fundamental layers of heritage. In the “stone and lime town”, where most monuments are located, this symbolic centrality manifests itself more subtly, due to the coexistence of mixed uses that combine institutional and residential functions. The recognition of the inhabitants as active actors reinforces the need for a participatory and inclusive approach. Heritage is no longer only what is seen and preserved in stone, but also what is practiced, celebrated, and transmitted from generation to generation.

This research, therefore, argues that the integration of the intangible dimension into heritage analysis methodologies is not merely a theoretical option but an ethical and practical requirement for safeguarding cultural heritage in its entirety. In this way, local actors—residents, community leaders, and religious figures—play a crucial role. They are not merely “users” of heritage, but co-authors of its meaning. Their participation must be integrated into conservation processes; otherwise, the result risks being a partial reading, disconnected from lived reality.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.A. and L.L.; Methodology, I.A., J.M.S. and L.L.; Validation, J.M.S., L.L. and L.C.; Formal Analysis, I.A., J.M.S. and L.L.; Investigation, I.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, I.A.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.M.S., L.L. and L.C.; Visualization, I.A.; Supervision, J.M.S. and L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

To the Faculty of Architecture and Physical Planning and Faculty of Social and Human Sciences from the Lúrio Universiy; to the PhD programe in Heritages of Portuguese Influence; to the Mozambique Island Conservation Office (GACIM); to the District Government of the Island of Mozambique; to the Municipal Council of the Island of Mozambique and the Museums of the Island of Mozambique; to Instituto Médio Politécnico da Ilha de Moçambique; to the Economic and Social Agents of the Island of Mozambique and the Maritime Museums; to the Sea Museum; to the Faculty of Architecture of Eduardo Mondlane University; to the Polytechnic University of Viseu; and to the Instituto Pedro Nunes (IPN).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GACIM | Mozambique Island Conservation Office |

| IMPIM | Polytechnic Institute of Mozambique Island |

References

- Duarte, R. Northern Mozambique in the Swahili World: An Archaeological Approach; Central Board of National Antiquities [Riksantikvarieämbetet]; Department of Archaeology and Anthropology, Eduardo Mondlane University, Department of Archaeology [Institutionen för Arkeologi]: Stockholm, Sweden; University of Uppsala: Uppsala, Sweden, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues, E.; Rocha, A.; Nascimento, A. Ilha de Moçambique; Alcance Editores: Maputo, Mozambique, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Secretaria de Estado da Cultura; Arkitektskolen i Aarhus. Ilha de Moçambique: Relatório—Report, 1982–85; Secretaria de Estado da Cultura: Moçambique; Arkitektskolen i Aarhus: Aarhus, Denmark, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Sollien, S.E. The Macuti House, Traditional Building Techniques and Sustainable Development in Ilha de Mocambique. In Proceedings of the ICOMOS 17th General Assembly and Scientific Symposium: Heritage as Driver of Development, Paris, France, 28 November–1 December 2011; pp. 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade, L.; Novela, M.; Araújo, R. Centro de Interpretação de Muhipiti. In Oficinas de Muhipiti: Planeamento Estratégico, Património, Desenvolvimento; Coimbra University Press: Coimbra, Portugal, 2018; pp. 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2003; Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/convention (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- ICOMOS. The Nara Document on Authenticity; ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1994; Available online: http://whc.unesco.org/events/gt-zimbabwe/nara.htm (accessed on 4 February 2025).

- ICOMOS. Approaches to the Conservation of Twentieth-Century Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS: Madrid, Spain; New Delhi, India, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- República de Moçambique. Decreto nr. 28/2006, de 13 de Julho: Cria o Gabinete de Conservação da Ilha de Moçambique e Aprova o Respectivo Estatuto Orgânico; Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Mozambique, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alcolete, I. Salvaguarda e Valorização do Património Edificado da Ilha de Moçambique. Contributos Para Uma Estratégia de Gestão Sustentável. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brand, S. How Buildings Learn: What Happens After They’re Built; Viking: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Kuipers, M.; Jonge, W. Designing from Heritage: Strategies for Conservation and Conversion; Delft University of Technology: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Leite, P. Casa Muss-Amb-Ike: O Compromisso No Processo Museológico. Ph.D. Thesis, Lusófona University of Humanities and Technologies, Lisbon, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- República de Moçambique. Decreto-lei nr. 55/2016 de 28 de Novembro: Regulamento Sobre a Gestão de Bens Culturais Imóveis. Boletim da República I Série, no 142; Publicação Oficial da República de Moçambique: Maputo, Mozambique, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Damen, S.; Roders, A.; Van Oers, R. Relating the State of Authenticity and Integrity and the Factors Affecting World Heritage Properties: Island of Mozambique as Case Study. Int. J. Herit. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. World Heritage Committee Nomination Documentation Ref. 599; ICOMOS: Carthage, Tunisia, 1991; Available online: https://whc.unesco.org/en/decisions/3526/ (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- Wynne-Jones, S. The Public Life of the Swahili Stonehouse, 14th–15th Centuries AD. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 2013, 32, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. Uses of Heritage; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jokilehto, J. A History of Architectural Conservation; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Eshrati, P.; Fadaei, N.; Eftekhari, S.; Azad, M. Evaluation of Authenticity on the Basis of the Nara Grid in Adaptive Reuse of Manochehri Historical House Kashan. Int. J. Archit. Res. ArchNet IJAR 2017, 11, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milão, S.; Ribeiro, T.; Correia, M.; Neves, I.C.; Flores, J.; Alvarez, O. Contributions to Architectural and Urban Resilience Through Vulnerability Assessment: The Case of Mozambique Island’s World Heritage. Heritage 2025, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).