Abstract

Focusing on mediatized urban images, this examination of Jiangnan water towns analyzes 1000 user-generated posts on Xiaohongshu through word frequency statistics, content categorization, and textual interpretation to demonstrate how “Seeding Strategy” transforms the symbolic representation and cultural identity of ancient towns. The results reveal that mediatized conceptions of water towns operate within a four-dimensional symbolic framework—natural, cultural, interactive, and Sentiment symbols—shaped by user co-creation and local cultural assets. Through photo-taking and check-ins, users convert historic towns from static geographical locations into dynamic media environments with visual and emotional resonance. Platform algorithms amplify engaging content, reinforcing spatial imaginaries. The concept of “symbolic effects on media platforms” elucidates how local culture is reconstructed and disseminated within digital frameworks, offering theoretical insights and practical recommendations for cultural tourism branding and cross-platform place research in the digital age.

1. Introduction

Jiangnan water towns serve as essential vessels of traditional Chinese culture and regional identity, embodying profound historical memory and aesthetic legacy. With the ongoing progression of China’s national policy for cultural-tourism integration, ancient towns have evolved from simple historical sites or tourist attractions into vital platforms for cultural diffusion and identity formation [1]. Simultaneously, the extensive utilization of digital media—especially content-centric platforms like Xiaohongshu (translated as “Little Red Book”, a Chinese lifestyle-sharing and social commerce platform, also recognized globally as RED)—has markedly amplified the impact of social media on tourist perceptions and behaviors. Through visually compelling and sentimentally resonant “Seeding Strategy” content, such platforms are redefining the parameters of place perception, transforming conventional towns from static geographical locations into mediated experiencing environments [2]. On Xiaohongshu, users partake in activities such as photography, check-ins, personal narratives, and hashtag interactions to transform individual travel experiences into sentimentally impactful and visually captivating material. By doing so, individuals engage in the creation of imagined locality and, implicitly, in the symbolic reproduction of place [3]. This participatory method modifies the distribution model of old towns and facilitates their evolution from cultural heritage sites into symbolically rich, influencer-oriented environments. Nevertheless, contemporary research mostly emphasizes city branding [4] and destination marketing techniques [5], insufficiently addressing the semantic reconstruction and cultural rearticulation of historic cultural sites within platform logic frameworks. Within the saturated realm of visual culture, the “locality” of historic towns undergoes reinterpretation, encountering symbolic fragmentation and commodification while simultaneously conforming to digital platform structural logic.

This work aims to bridge this gap by selecting five exemplary historic towns in Jiangnan and analyzing user-generated content (UGC) on Xiaohongshu using word frequency analysis and textual interpretation. It establishes a four-dimensional symbolic framework—natural symbols, cultural symbols, interactive symbols, and Sentiment symbols—to examine the mediated production of ancient town imagery and the development of cultural identity. This study focuses on the subsequent fundamental inquiries: (1) In what manner does the logic of “Seeding Strategy” culture facilitate synergy among users, platforms, and local cultural resources? (2) In what manner may the suggested four-dimensional symbolic framework elucidate the mediatized fabrication of place imagery? (3) What are the theoretical implications of the “symbolic effects on media platforms”, and how do they elucidate the reconstruction of local culture in the digital realm? (4) In what ways may this paradigm yield novel theoretical insights and pragmatic solutions for cultural-tourism branding and cross-platform locality research?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Social Media and the Construction of Urban Imagery

In recent years, social media has become a potent medium for information diffusion and cultural production, significantly influencing urban imaging and local identity. In contrast to the linear, top-down dissemination model prevalent in traditional media, social platforms cultivate a “decentralized–highly interactive–visual” communication ecology through the interaction of user-generated content (UGC) and algorithmic distribution [6]. This process continuously amplifies and replicates users’ personal experiences, sentiments, and visual outputs, resulting in a novel spatial order where cities are progressively “seen”, “photographed”, and “imitated” [7]. In China, platforms like Xiaohongshu and Douyin have exacerbated this transition through the pervasive popularity of “Seeding Strategy” and “check-in” cultures. These activities augment users’ sensory interaction with physical environments and transform the creation of urban imaging from a government-driven, hierarchical process to one collaboratively developed and disseminated through platform dynamics and user actions [8]. Simultaneously, algorithmic intervention is crucial in establishing visibility hierarchies by dictating the prominence of specific content kinds. Via this “visibility mechanism”, platforms determine the prioritization and dissemination of urban representations [9], hence fostering the development of platformized spatial perceptions—forms of place recognition influenced by visual allure and affective impact.

2.2. Place Symbols, Media Construction, and Seeding Strategy

2.2.1. Conceptualizing Place Symbols

Place symbols serve as symbolic representations of spatial culture, acting as intermediates that connect geographic space with social identity. Traditionally, these symbols are rooted in historical culture, architectural landscapes, or regional products, and are manifested in static forms to express the distinctive attributes of a location. In the context of media transition, place symbols have become dynamic, adaptable, and widely disseminated cultural units, perpetually reorganized, reinterpreted, and nested by users on social media platforms [10]. These symbols embody collective memory and identity while increasingly serving as essential assets in the commodification of culture and tourism marketing [11]. Research indicates that the dissemination of place symbols transcends their initial cultural context; instead, it is restructured through platform aesthetics, affective markers, and visual norms. This has resulted in a process of mediated reterritorialization, wherein “place” transcends its actual location to become a perceptual space co-constructed by user experience and platform-driven content.

2.2.2. The Mediatization of Jiangnan Water Towns

Jiangnan water towns, as prominent spatial embodiments of traditional Chinese culture, have increasingly featured on social media platforms in recent years, showcasing the traits of mediatized tourist destinations. Current research suggests that user-generated images, videos, and sentimentally resonant posts on platforms like Xiaohongshu have progressively established a series of visual templates—focused on themes such as “misty rain”, “Hanfu”, and “aesthetic photo spots”—that transform the mediated representations of these towns [12]. These depictions frequently characterize the towns as “poetic Jiangnan”, “cultural homelands”, or “visual feasts”, thus surpassing their original geographical and historical characteristics and converting them into cultural landscapes influenced by platform scrutiny and reinterpretation [13]. Nevertheless, current research on the mediatization of historic towns predominantly emphasizes isolated elements, such as affective expression or tourist behavior, and fails to provide a comprehensive structural study of the overarching symbolic system. The synergistic interaction among interactive, affective, and cultural symbols is particularly underexplored.

2.2.3. Conceptualizing the Seeding Strategy

The term “Seeding Strategy” refers to the emergence of inner desires and comes from Chinese online slang. Simply, “generating desire” has given way to “stimulating the desires of others”. This idea is a fundamental component of Xiaohongshu, which has transformed a subculture-based expression into a widely used commercial application. According to Humphreys and Liao (2011) [14], “check-in” refers to location-based social media behaviors that transform individual travel paths into visible social interactions. The fundamental idea behind the “Seeding Strategy” on social media comes from research on electronic word-of-mouth, which emphasizes visual and emotional appeal over merely logical evaluation and suggests that unplanned user recommendations have greater sway than official advertising [15]. Because both emphasize the influence of content producers on audience decision-making, it is comparable to influencer marketing [16]. It encapsulates the key features of user-generated content (UGC), which blurs the distinction between sharing and promotion and is created by individuals rather than organizations [17]. The “Seeding Strategy” is implemented on the Xiaohongshu platform through a four-pronged mechanism: conversion orientation (algorithmically prioritizing high-conversion content), desire visualization (using the “favorites” feature), discourse normalization (e.g., using tags like “must check-in”), and content standardization (via “note” templates). Users effectively distribute material through the platform’s recommendation system and stimulate consumption impulses by using visual, emotional, and practical tools to communicate their trip experiences [18].

2.3. Theoretical Framework

This study synthesizes three theories to examine how social media platforms transform the symbolic depiction of traditional cultural settings. Mediatization theory illustrates the transformation of media from a communication tool into a fundamental cultural construct. The notion of “deep mediatization” introduced by Couldry and Hepp (2018) [19] posits that platforms have evolved into a “meta-media” environment, wherein users’ quotidian actions generate cultural significance [20]. Four dimensions of mediatization—extension, substitution, amalgamation, and adaptation—offer a framework for examining how Xiaohongshu transforms ancient towns: the platform broadens the towns’ perceptible boundaries, content partially replaces the role of physical visits, online imagination merges with offline experience, and cultural symbols are adaptively re-coded to align with platform aesthetics.

Semiotic theory, conversely, enhances mediatization theory by emphasizing the significance of symbols. Barthes’ (1977) [21] triadic semiotic framework—denotation (literal meaning), connotation (cultural association), and myth (ideology)—illustrates how symbols such as “water towns” and “stone bridges” evolve from denoting physical landscapes to embodying cultural significances like “therapeutic” and “poetic”, thereby reinforcing the notion that “Jiangnan signifies a slow-life utopia”. Eco’s (1979) [22] notion of “super-coding” illustrates how users perpetually generate meaning through the formation of novel symbolic combinations, shown by “Hanfu plus ancient towns”. Third, platform studies emphasize the distribution mechanisms inherent in technology structures. Van Dijck et al. (2018) [23] propose the notion of a “platform society”, while Gillespie (2018) [24] presents the theory of algorithmic visibility, suggesting that content is curated based on interaction metrics. This results in the systematic enhancement of visually prominent symbols, while knowledge-rich symbols are relegated, thus altering the valuation of cultural symbols. This study introduces the concept of the “symbolic effect of media platforms”. Within the realm of social media, local cultural symbols experience selective amplification, templated recombination, and decontextualized circulation due to the dynamic interplay of platform architecture, user practices, and cultural resources, thereby systematically transforming collective perception and cultural identity, and enhancing the comprehension of local cultural collective perception and identity in the digital age.

2.4. Research Gap and Questions

Despite the growing research on city branding, local identity, and media spatiality, a gap persists in the examination of the symbolic construction of traditional cultural locations on social media platforms. Despite substantial advancements in existing research—investigations into city branding and social media impact have demonstrated how platforms such as Instagram and Twitter alter urban imagery [4,5], user-generated content (UGC) and destination image studies have indicated how tourists’ online sharing influences destination perception [25], and analyses of mediatization and locality have examined how digital media reshapes perceptions and identities of locales [19]—three critical gaps remain to be addressed. Initially, there exists a disparity in research subjects: the current literature sufficiently examines the mediatization of contemporary urban environments and natural landscapes, yet it neglects the digital representation of traditional cultural spaces that embody significant historical memory and cultural identity, exemplified by the ancient towns of Jiangnan. Secondly, there exists a fragmentation of theoretical perspectives: contemporary research either concentrates on mediatization theory, which highlights technology’s influence on culture, or examines the representation of cultural symbols from a semiotic viewpoint, or investigates platform studies that uncover algorithmic power, yet fails to provide a theoretical framework that synthesizes these three perspectives to systematically elucidate the reconstruction mechanisms of local culture in the digital era. In addition, few studies have adopted a methodological framework that combines text mining with semiotics. This study selected five representative historical towns in Jiangnan and conducted a comprehensive analysis of user-generated content, using information from the Xiaohongshu platform to address these gaps.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Subjects

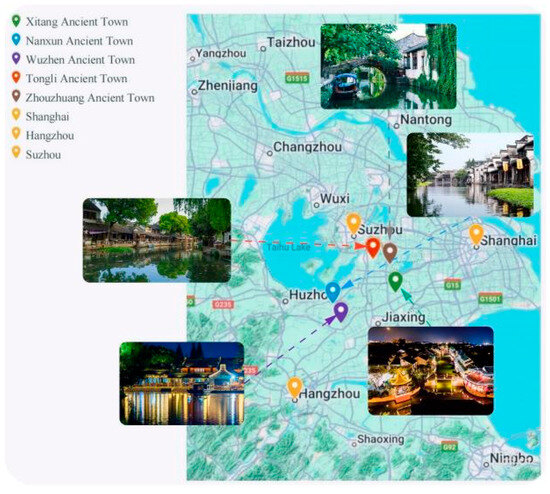

This study identifies five historical water towns in Jiangnan—Nanxun, Tongli, Wuzhen, Xitang, and Zhouzhuang—as subjects of investigation. The towns are situated in the Yangtze River Delta region of eastern China (30–32° N, 119–122° E), primarily encompassing Shanghai, southern Jiangsu Province, and northern Zhejiang Province. This region is distinguished by its intricate river systems, picturesque water-town scenery, and abundant cultural legacy, and is among the most economically advanced and urbanized areas in China. This study’s selection of ancient towns is grounded in a thorough assessment of data from platforms like Meituan and Dianping, encompassing overall ratings, review counts, and the tourist recommendation index. The five towns exhibit elevated exposure rates on the Xiaohongshu platform, with frequent references in user-generated content mirroring the conventional media portrayal of Jiangnan water towns and the attributes of the ‘Seeding Strategy’ recommendation mechanism. Figure 1 shows the geographic location of the five towns in Jiangnan and their spatial relationships with the surrounding major cities (Shanghai, Hangzhou, Suzhou).

Figure 1.

Geographic location of five Jiangnan ancient towns.

3.2. Data Collection and Analytical Methods

Data Sources and Sampling Techniques: The Xiaohongshu platform was chosen as the data source for this investigation. Xiaohongshu is a prominent lifestyle-sharing portal in China. A stratified random sample technique was employed, comprising the subsequent precise steps: Five ancient towns were individually typed into the platform’s search box, accompanied by terms such as ‘tourism’, ‘travel guide’, and ‘check-in’ for combined searches, rotating between ‘comprehensive ranking’ and ‘popular ranking’ methodologies. The duration was established from January 2021 to March 2025. Posts were randomly selected within each time frame to ensure balanced temporal distribution. A total of 1000 valid samples were obtained, with 200 posts selected from each historic town.

The screening criteria included the following: likes ≥ 1000 and comments ≥ 300, to guarantee a requisite level of user engagement and dissemination impact.

Attributes of Sample Participants

An analysis of the public profile information of the writers of the sampled posts revealed that the majority were users from mainland China. Regarding gender composition, around 75% of users were female and 25% were male. The age distribution indicates that the majority were aged between 18 and 35 years, with the predominant subgroup being those aged 20 to 28.

Data Acquisition and Examination

This research employed JavaScript (ES2017) with Node.js18.0 to create an automated browser extension, utilizing Puppeteer21.0 for data scraping and extracting fields including title, main content, topic tags, number of likes, number of comments, publishing time, and user information. During data cleaning, text similarity algorithms and hash comparisons were employed for deduplication, removing advertisements and duplicate content.

Data analysis was conducted utilizing Python 3.13, in conjunction with the Jieba segmentation module and the Pandas tools for text mining. The methodological framework encompasses word frequency analysis and symbol categorization.

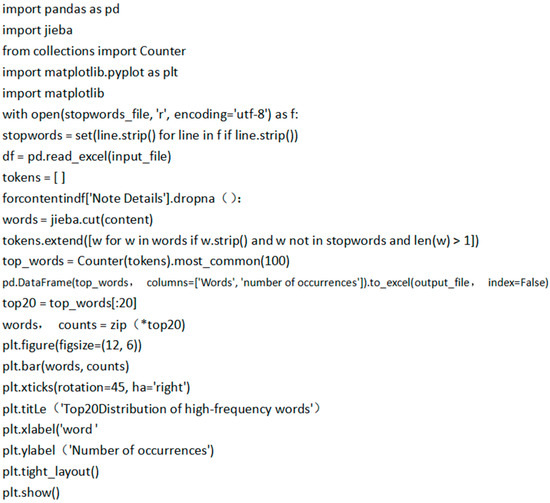

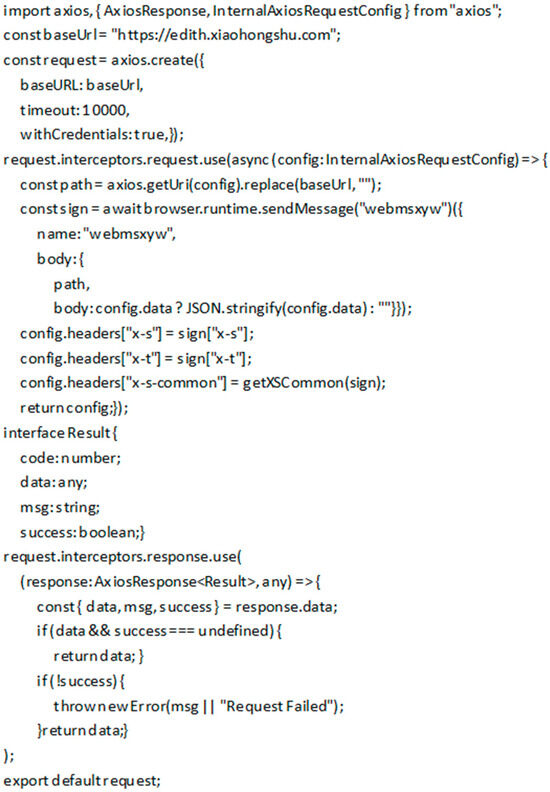

This research employed a mixed-methods approach, integrating quantitative word frequency analysis with qualitative semiotic examination. The analytical framework comprises three sequential tiers. The initial level involves a word frequency analysis layer that employs Jieba segmentation and frequency computation to discern high-frequency terms, which form the ‘explicit text’ of the media representation of ancient towns. The second level is the symbol classification layer, wherein high-frequency words are systematically divided into four dimensions—nature, culture, interaction, and sentiment—utilizing a pre-established classification dictionary, therefore transforming disparate words into an organized symbol system. The third level is the meaning interpretation layer, which, with Barthes’ three levels of semiotics, examines how various symbols are encoded and transmitted within the platform environment, uncovering the cultural logic underlying the symbols. An automatic categorization technique utilizing a theory-driven lexicon was employed to analyze 1000 postings, producing visual representations including word clouds and sunburst charts. In conjunction with qualitative content analysis, representative texts were thoroughly evaluated. Figure 2 and Figure 3 code snippet demonstrates the primary process.

Figure 2.

Chinese text word frequency analysis and visualization code.

Figure 3.

API request encapsulation code.

3.3. Construction of the Symbolic Coding Framework

A “media imagery symbol coding framework” was developed for ancient towns to systematically study the mediatized representation of town imagery in user-generated posts. This framework is based on the study of urban visual symbol dimensions by Sheng, R. (2022) [26] and has been regionally adapted to incorporate the geographical features of five case-study ancient towns as well as platform-specific modes of expression. The framework establishes a primary symbol hierarchy, including four types of symbols, specifically adapted to the unique environment of Jiangnan ancient cities. The structure of the framework follows a theory-driven inductive coding paradigm, ensuring that each symbol dimension aligns with a specific theoretical resource. The natural symbol dimension derives from Relph’s (1976) [27] ‘sense of place’ theory and Barthes’ ‘denotation’ layer, encompassing symbols that directly reference the physical landscape; the cultural symbol dimension aligns with the notion of ‘cultural capital’ in cultural heritage studies and Barthes’ ‘connotation’ layer, pinpointing symbols imbued with historical memory and cultural significance, thereby imparting a sense of identity to ancient towns through cultural associations; the interactive symbol dimension is informed by participatory culture theory and Eco’s ‘semiotic production’, capturing user behaviors and illustrating how users collaboratively shape the image of ancient towns; the Sentiment symbols dimension is grounded in affective geography and Barthes’ ’myth’ layer, identifying sentimentally charged evaluative terms and demonstrating how ancient towns are transformed into spaces of psychological belonging. This approach maintains equilibrium between theoretical sensitivity and data transparency, offering direction for coding. Throughout the coding process, each post was meticulously annotated to guarantee semantic precision and subjected to several verification rounds to ensure intercoder reliability, ultimately resulting in a standardized symbol categorization Table 1.

Table 1.

Symbolic encoding table for ancient town media images.

4. Research Findings

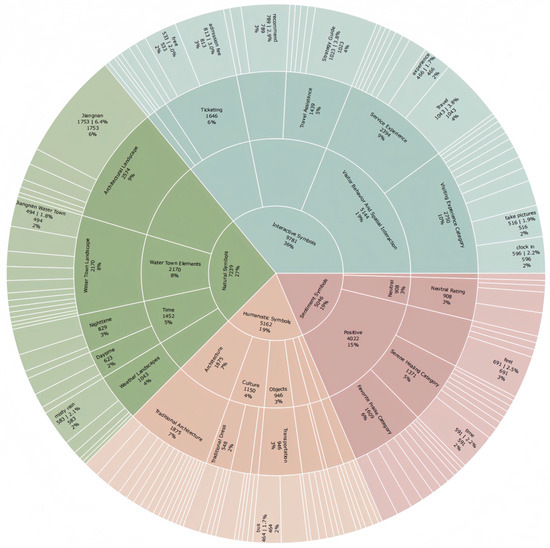

4.1. Overall Distribution of Symbolic Representations in Ancient Town Imagery

Textual mining and word frequency analysis reveal that the mediated imaginaries of the five Jiangnan ancient towns display the following structural characteristics: interpersonal predominance, nature emphasis, cultural diversity, and affective depth.

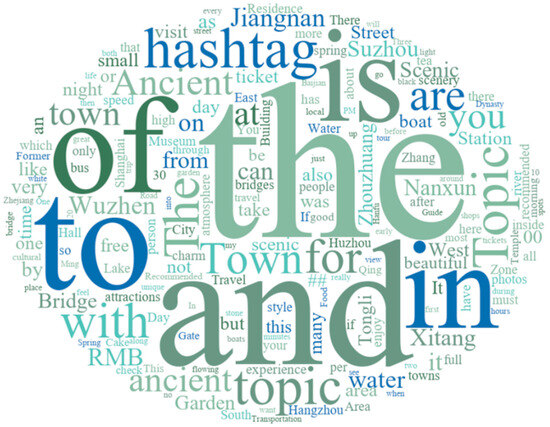

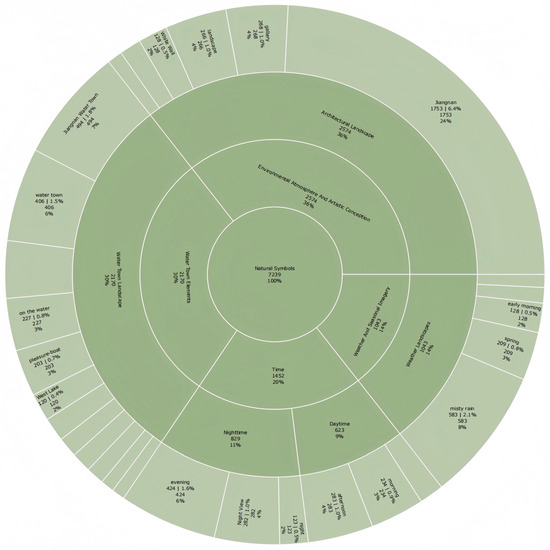

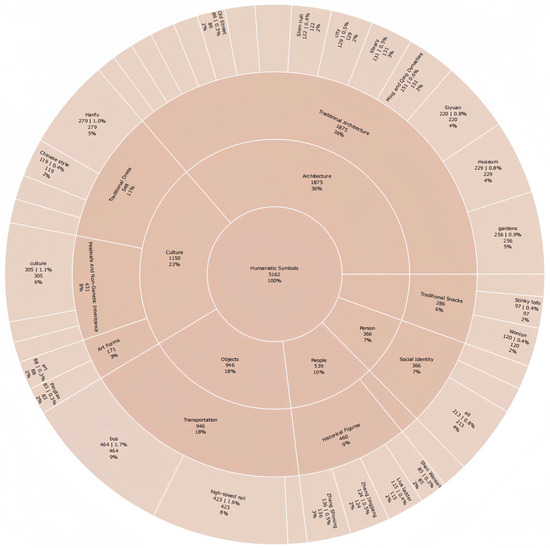

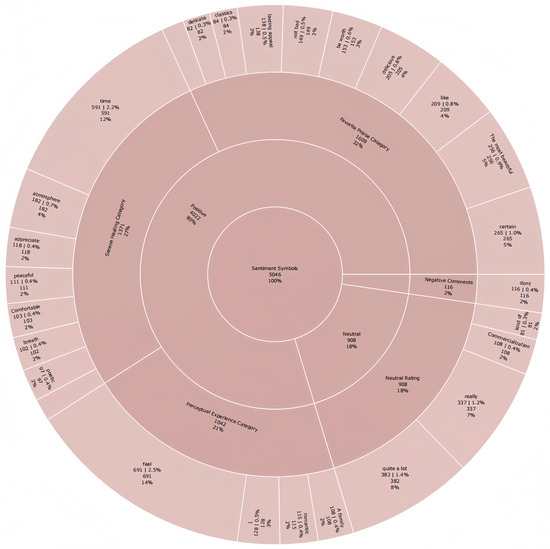

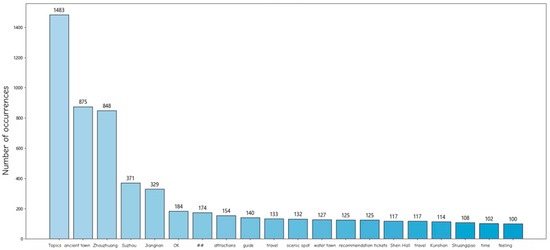

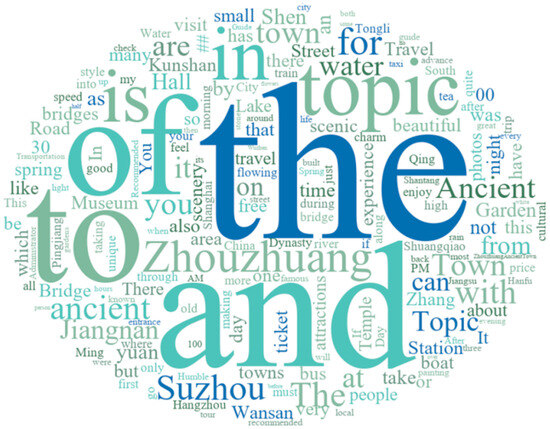

Figure 4: Four-Level Symbolic System of Ancient Town Media Imagery and Figure 5: Word Cloud of High-Frequency Keywords in Five Ancient Towns depict the high-frequency keywords derived from user-generated material along with their respective classifications within the four-dimensional symbolic framework. Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present the internal composition of each symbol category through a hierarchical visual framework—specifically encompassing Interactive symbols, Natural symbols, Humanistic symbols, and Sentimentl symbols.

Figure 4.

Four-level symbolic system of ancient town media imagery. Available online: https://www.imagehub.cc/image/66662.MlTWBt (accessed on 4 November 2025).

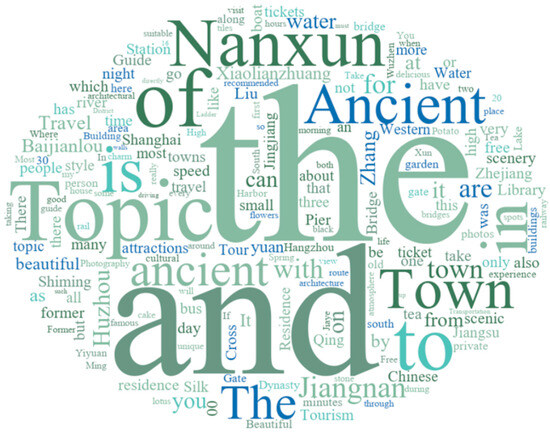

Figure 5.

Word cloud of high-frequency keywords in five ancient towns.

Figure 6.

Sunburst chart of interactive symbols. Available online: https://www.imagehub.cc/image/Interactive-Symbols.MlTNDv (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Figure 7.

Sunburst chart of natural symbols. Available online: https://www.imagehub.cc/image/Natural-Symbols.MlT61h (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Figure 8.

Sunburst chart of Humanistic symbols. Available online: https://www.imagehub.cc/image/Humanistic-Symbols.MlTn4G (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Figure 9.

Sunburst chart of Sentiment symbols. Available online: https://www.imagehub.cc/image/Humanistic-Symbols.MlTn4G (accessed on 4 November 2025).

Interactive symbols (9781 occurrences) predominantly focus on ‘guides’, ‘recommendations’, ‘take pictures’, and ‘check-ins’, illustrating users’ active engagement in shaping local perceptions through content creation and sharing.

Natural symbols (7239 occurrences) predominantly highlight ‘Jiangnan’, ‘water town’, and ‘misty rain’ to enhance the visual imagery of water towns in historical villages.

Humanistic symbols (5162 occurrences) include ‘gardens’, ‘Hanfu’, and ‘museum’, illustrating the re-production of cultural legacy within the context of ‘Seeding Strategy’.

Sentiment symbols (5046 occurrences) predominantly include ‘like’, ‘very’, and ‘comfortable’, to establish a ‘positive sentiment accumulation’ and local identity.

4.2. The “Seeding Strategy” Logic of Mediated Imaginaries

4.2.1. Nanxun Ancient Town: The Integration of Natural Imagery and Cultural “Seeding Strategies”

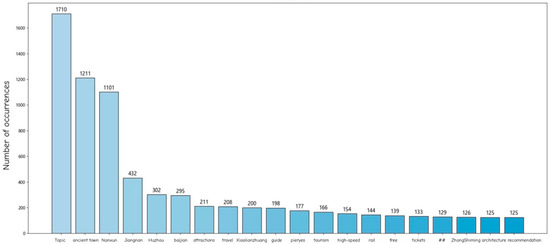

The symbolic depiction of Nanxun Ancient Town demonstrates a complex and interwoven nature of natural and cultural symbolism. The natural symbols ‘Jiangnan’ (432 occurrences), ‘on the water’ (96 occurrences), and ‘water town’ (61 occurrences) create a visual imagery axis, indicating users’ profound identification with the characteristic morphology of water towns. In accordance with Zhu, Y. (2015) [28]’s depiction of Nanxun’s ‘waterfront street pattern’ and the visual of ‘little bridges and flowing water with residential houses’, this underscores the town’s representative nature as a ‘conduit of Jiangnan cultural landscapes’. Simultaneously, cultural landmarks are extensively distributed. ‘Zhang Shiming Former Residence’ (126 occurrences) and ‘Library Building’ (119 occurrences) emerged as often-nominated cultural symbols. The Zhang Shiming Former Residence serves as both a representation of local aristocratic culture and a tangible testament to Nanxun’s old gentry society, thus enhancing the town’s cultural richness. The frequent occurrences of ‘taking photos’ (99 times), ‘checking in’ (85 times), and ‘recommending’ (125 times), as illustrated in Table 2, suggest that users, via visual production and spatial interaction, convert Nanxun from a static geographic space into a visualized symbolic domain. In conjunction with the study on the ‘user empowerment mechanism in Xiaohongshu visual communication’ [8,29], it is evident that this process fundamentally involves the co-creation of visual imagery produced by the platform’s content processes and users’ aesthetic inclinations. Nanxun’s ‘natural + cultural’ integrated distribution approach exemplifies the ‘dual gaze of media landscapes’ mechanism: it fulfills tourists’ immediate visual aesthetic requirements while simultaneously imparting a sense of cultural profundity through cultural landmarks. As illustrated in Figure 10 and Figure 11 and Table 2.

Table 2.

Statistics of high-frequency symbols in Nanxun Ancient Town.

Figure 10.

Top 20 high-frequency words in Nanxun Ancient Town.

Figure 11.

High-frequency word cloud of Nanxun Ancient Town.

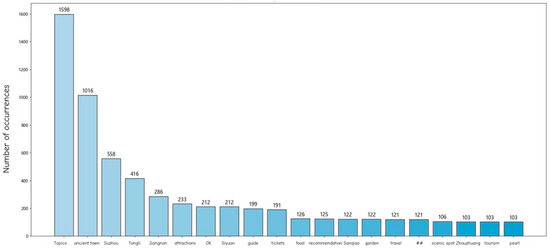

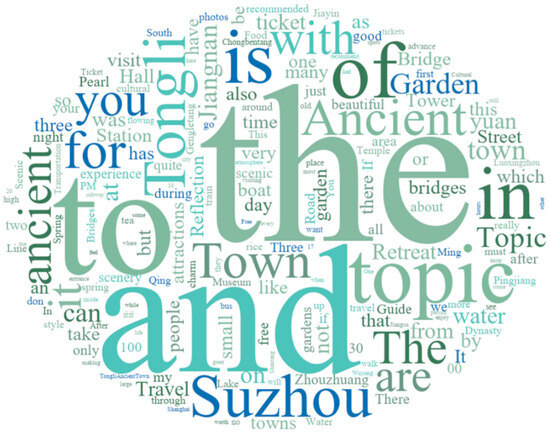

4.2.2. Tongli Ancient Town: Bridge-Water Imagery and the Logic of “Seeding Strategy” Narratives

Tongli Ancient Town exemplifies a quintessential ‘bridge and river cultural motif’. Terms like ‘Jiangnan’ (286 occurrences) and ‘little bridges and flowing water’ (61 occurrences) prominently appear, underscoring Tongli’s typical water town characterized by ‘water—bridges—alleys’. This corresponds with the (He & Henwood, 2015; Porfyriou, 2019) [1,13] characterization of Tongli’s spatial configuration as ‘water streets and alleyways as the framework, garden culture as the essence’.

Within the cultural dimension, ’Siyuan’ (212 occurrences) and ‘garden’ (122 occurrences) prominently feature, with people regarding classical gardens as key emblems of visual narrative. Siyuan exemplifies a conventional private garden, whose aesthetic framework has been identified by Zhu (2015) [28] as a significant representation of Jiangnan settlement culture. Interactions like ‘recommend’ and ‘photographing’ signify that tourists evolve from passive observers of the scenery to ‘constructors of local imagery’, reflecting the assertion in tourism studies of Tongli [2,25] that ‘tourists’ perception paths have transitioned from offline landscapes to online semantic landscapes.’

The media representation of Tongli Ancient Town gradually embodies the ‘ink-wash Jiangnan’ through the combined influences of ‘bridge and water images’ and ‘garden culture’. As illustrated in Figure 12 and Figure 13 and Table 3.

Figure 12.

Top 20 high-frequency words in Tongli Ancient Town.

Figure 13.

High-frequency word cloud of Tongli Ancient Town.

Table 3.

Statistics of high-frequency symbols in Tongli Ancient Town.

4.2.3. Wuzhen: Nocturnal Aesthetics and the “Seeding Strategy” Experience

Wuzhen showcases a “nightscape aesthetics” tableau, with user observations emphasizing the visual transmission of nocturnal experiences and culture. Wuzhen boasts a night tourist sector, with “night view” (90 occurrences) and “experience” (192 occurrences) as prevalent phrases, indicating that visitors are attracted to the nocturnal ambiance and multisensory encounters. This inclination corresponds with night tourism development research by Wang & Bramwell, 2012 [30], which suggests that “night lighting and spatial ambiance collectively form local attraction”.

The prevalence of “Drama Festival” (67 occurrences) indicates Wuzhen’s evolution from a traditional ancient town to a cultural intellectual property, as Chen & Tsai (2007) [31] observed that cultural events in destination image construction have progressed from a “supplementary project” to a “narrative hub”.

In terms of interactive behavior, phrases like “taking photos” (130 occurrences) and “checking in” (128 occurrences) are prevalent, reflecting Buhalis & Law (2008)’s [32] perspective on “spatial reconstruction driven by visual narratives”, as users disseminate their experiences through nocturnal photography, light recordings, and dynamic videos, thereby influencing the perception of “Wuzhen at Night”.

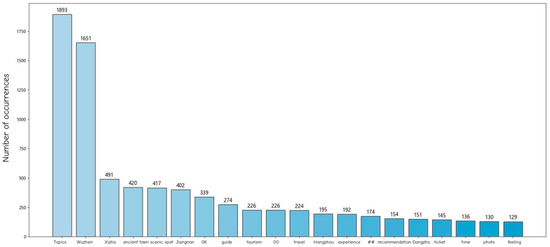

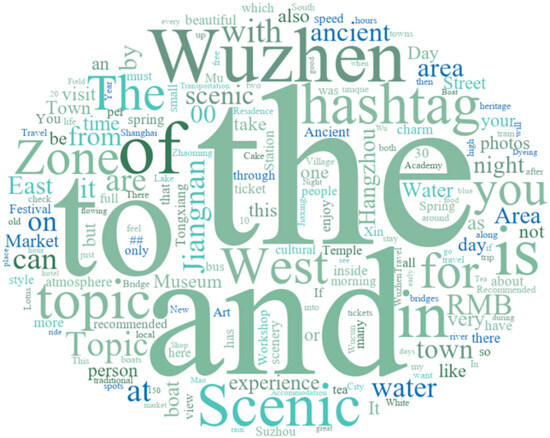

Utilizing the tripartite narrative structure of “night view—Drama Festival—experience”, Wuzhen has established a nighttime cultural brand characterized by current expression. This perpetuates Wuzhen’s recent developmental strategy of “night tourism economy + cultural intellectual property”. As illustrated in Figure 14 and Figure 15 and Table 4.

Figure 14.

Top 20 high-frequency words in Wuzhen.

Figure 15.

High-frequency word cloud of Wuzhen Ancient Town.

Table 4.

Statistics of high-frequency symbols in Wuzhen Ancient Town.

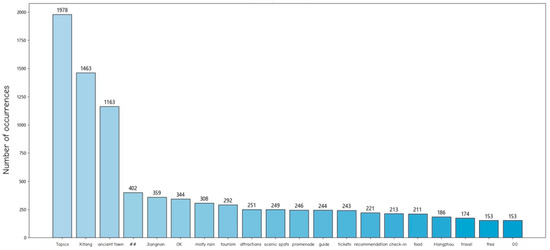

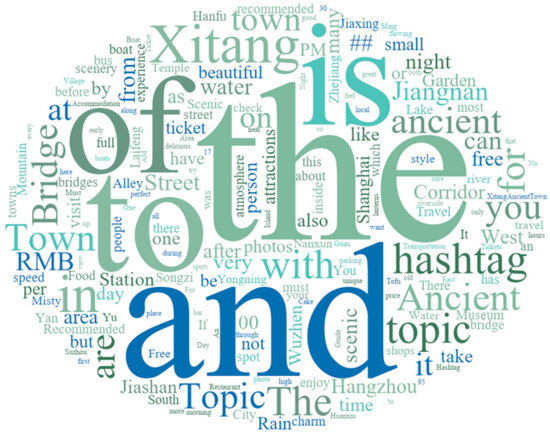

4.2.4. Xitang Ancient Town: Visual Performance and the Culture of “Seeding Strategy”

Xitang is distinguished by its ‘Mist and Rain Corridor’ and ‘Hanfu Photography’. The elevated occurrence of phrases like ‘mist and rain’ (308 instances), ‘corridor’ (246 instances), and ‘Hanfu’ (128 instances) signifies a concentrated manifestation of visual signals. This feature reflects a study on Xitang’s ‘transition to cultural performances’, which suggests a ‘visual theatricalization of local landscapes’: the ancient town evolves from a mere historical artifact into a cultural venue for performance through visitors’ physical interaction and costume reinterpretation. The terms ‘recommend’ (221 occurrences) and ‘check-in’ (213 occurrences) underscore users’ dependence on platforms for content generation, articulating personal experiences via the identification of ‘recommendation places’ and ‘check-in locations’. ‘Hanfu photography’ serves as a reimagining of the visual representation of the ancient town. Zong, Y (2025) [12] asserts that cultural identity in tourism social media is frequently manifested through the interplay of attire, context, and photographs, with Xitang’s ‘Hanfu experience’ serving as a prime illustration of this paradigm. Xitang has transitioned from conventional ‘historical reproduction’ to a ‘performative town’ focused on visual spectacle and cultural consumption. This discovery offers empirical validation for prior research that claims the ‘interconnection of landscape aesthetics and profound tourist involvement’ in Xitang [9]. As illustrated in Figure 16 and Figure 17 and Table 5.

Figure 16.

Top 20 high-frequency words in Xitang Ancient Town.

Figure 17.

High-frequency word cloud of Xitang Ancient Town.

Table 5.

Frequency symbol statistics of Xitang Ancient Town.

4.2.5. Zhouzhuang Ancient Town: Traditional Symbols and ‘Seeding Strategy’ Participation

Zhouzhuang highlights ‘aquatic town environment’ and ‘historical architecture’ as its principal imagery. Commonly mentioned terms like ‘water town’ (127 instances) and ‘Shen Hall’ (117 instances) indicate users’ focus on the ambiance of Jiangnan water towns and their distinctive culture. This corresponds with participatory tourism research (He & Henwood, 2015; Su et al., 2019) [1,13] on ‘participatory re-creation of historical space’ in local identity formation in Jiangnan ancient towns.

Shen Hall, as a quintessential example of Ming and Qing architecture in Zhouzhuang, is often referenced in activities such as ‘photography’ and ‘recommendation.’ This ‘immersive experience’ enhances users’ impression of the location and converts Shen Hall from a mere monument into a venue for cultural engagement. Integrating Urry’s (1992) [33] idea of ‘culture space in the tourist gaze’, the cultural architecture of Zhouzhuang benefits from substantial diffusion advantages in platform contexts owing to its ‘viewability, occupiability, and photographability’. In Zhouzhuang Ancient Town, user-generated content pertaining to cultural assets such as Shen Hall and water alleyways establishes a cultural media landscape that preserves historical memory and facilitates effective visual distribution. This depiction reinforces Zhouzhuang’s cultural status as a ‘prototype of Jiangnan old cities’ and enhances its significance as a cultural emblem [13]. As illustrated in Figure 18 and Figure 19 and Table 6.

Figure 18.

Top 20 high-frequency words in Zhouzhuang Ancient Town.

Figure 19.

High-frequency word cloud of Zhouzhuang Ancient Town.

Table 6.

Frequency symbol statistics of Zhouzhuang Ancient Town.

4.3. Comparison of Ancient Towns: Differentiated Patterns of Symbolic Representation and Structural Convergence

The five ancient towns exhibit marked differences, as shown in Table 7. Xitang is characterized by natural symbols (8 terms/1405 occurrences), with ‘mist and rain’ (308 occurrences) and ‘covered bridge’ (246 occurrences) serving as its primary visual identifiers. The cumulative frequency of its top 30 terms totals 3965 occurrences, the highest among the five towns. Wuzhen is defined by interactive symbols (12 terms/1386 occurrences), notably ‘travel guides’ (274 occurrences), “experiences” (192 occurrences), and ‘theatre festivals’ (67 occurrences), forming an experience-centric profile with higher interaction rates at night than during the day. Zhouzhuang possesses the highest number of cultural symbol entries (11 terms); however, it has only 2 emotional symbols, appearing 156 times, the lowest among the five cities. Tongli demonstrates a highly balanced symbolic fusion, with cultural symbols (9 terms/746 occurrences) and interactive symbols (9 terms/745 occurrences) appearing at similar frequencies. Nanxun possesses the highest number of interaction symbol entries (13 words); however, the interaction frequency of its cultural symbols, such as ‘Zhang Shiming’s Former Residence’ (126 occurrences) and ‘Library Building’ (119 occurrences), remains limited. Nevertheless, beneath these varied manifestations, two fundamental similarities emerge. All ancient towns exhibit interaction symbol entries ranging from 8 to 13, with ‘recommendation’ consistently ranking within the top three across all five towns’ TOP30 lists. Tool-oriented vocabulary, such as ‘check-in’ and ‘photography’, systematically outweighs culturally interpretive content. Secondly, ‘Jiangnan’ occupies the top position in the TOP30 of all ancient towns, indicating that user recognition primarily relies on this macro-regional symbol rather than individual place names. This pattern of ‘superficial variation, deep instrumentalism’ illustrates the dual logic of local culture in the platformisation process: while regions strive to create competitive advantages through unique symbols, these efforts are undermined by the homogenizing forces of the platform.

Table 7.

Statistics of symbol types for the Top 30 high-frequency words in five ancient towns.

5. Discussion

5.1. Symbolic Relations in the Mediated Imagery of Ancient Towns

This study presents a four-tier structure of symbolic construction: “natural symbols–cultural symbols–interactive symbols–Sentiment symbols”. Symbols are dynamic constructs that are perpetually reconstructed and reinterpreted within platform contexts [34]. This structure illustrates the visual representation of ancient settlements through text and video, emphasizing the intricate collaborative dynamics across platforms, users, and cultural resources.

Natural symbols like “misty rain”, “Jiangnan”, “water town”, and “small bridges over flowing water” elicit poetic imagery and constitute the aesthetic foundation of old town representations. This corresponds with Relph’s (1976) [27] theory of “sense of place”, which conceptualizes place as a cultural and affective amalgamation transcending mere physical area. Owing to their intrinsic sensory and imitative allure, such symbols typically disseminate mimetically among users.

Cultural emblems embody the richness and substance of historic local heritage. Elements such as “library pavilion”, “drama festival”, and “Hanfu” (traditional attire) embody knowledge-based cultural essences and function as pillars of local cultural identity. When combined with natural symbols, these produce a more potent visual and affective effect. This intersymbolic connection positions ancient settlements as intricate story landscapes [35].

Interactive symbols serve as a crucial mechanism in conveying imagery of ancient towns. Users transition from “photography” to “aesthetic output” and from “recommendations” to “warnings”, functioning not merely as content consumers but as co-creators and rewriters within symbolic realms. This reflects Van Dijck’s (2018) [23] notion of collective memory formation within platform societies.

Sentiment symbols enhance the representation of towns beyond mere structural aesthetics to significant affective and identity-related elements. Terms such as “lovely”, “worth it”, and “tranquil” commonly manifest in captions and comment sections, illustrating how people sentimentally invest in these places for self-identity and psychological restoration. These emotive discourses create a “digital affective landscape” [36], establishing the subtle cultural basis of place identity.

5.2. Four-Dimensional Symbol System: Structural Attributes of the Mediatized Formation of Local Imagery

The four-dimensional symbols indicate that the creation of symbols representing Jiangnan historic towns on social media adheres to a distinct logic of mediatization, contesting the linear premise in conventional local symbol research that “cultural depth dictates dissemination breadth”. The four categories of symbols do not exist concurrently but instead create a progressive hierarchy from “material foundation” to “meaning deepening”. Natural symbols (7239 occurrences), as fundamental signifiers, align with the “denotation” level articulated by Barthes (1977) [37], directly referencing the depicted actual landscape. High-frequency terms like “Jiangnan”, “water town”, and “misty rain” emerge as favored components for content creation due to their pronounced visual appeal and cultural significance, resonating with Relph’s (1976) [27] concept of “sense of place”, wherein a location transcends mere physical coordinates to embody a cultural construct shaped by sensory experiences. Nonetheless, their transmission advantage arises not from cultural profundity but from “visual conversion efficiency”, indicating the rapidity with which user response can be elicited. Cultural symbols, with 5162 occurrences, possess historical significance and cultural depth, although they are markedly less prevalent than natural and interactive symbols. The prevalence of interactive symbols (9781 occurrences) signifies a transition in the construction of local imagery from a “logic of representation” to a “logic of participation”, corroborating discourse on “participatory culture”, wherein user engagement does not entail a profound interpretation of local culture, but rather the conversion of personal experiences into replicable content templates via standardized action verbs (such as “recommend” and “check-in”). The occurrence of Sentiment symbols (5046 instances) indicates that the ancient town has evolved from a mere physical location into a site of affective psychological attachment, aligning with the “myth” layer in Barthes’ semiotic theory, which exemplifies how symbols are ideologized in dissemination and embody social values that transcend their literal significance [37]. The principal conclusion of the four-dimensional framework is that the efficacy of symbol transmission is collectively influenced by visuality, interactivity, and affective resonance. This finding offers a novel analytical framework for comprehending the mediatized development of local culture in the digital age.

5.3. The Symbolic Impacts of Media Platforms: From Selection to Decontextualization

The framework of ‘symbolic impacts of media platforms’ did not emerge spontaneously. Scholars investigate digital-age cultural transformations from multiple perspectives: media studies scholars examine technology’s influence on culture [19], semioticians analyze cultural symbol representation [22], and platform studies researchers explore algorithmic authority [23]. Nonetheless, these viewpoints frequently exist in isolation, devoid of an analytical framework that synthesizes technology, symbols, and power. This study seeks to address this gap by elucidating the digital reconstruction of local culture on social media via four distinct techniques. On the Xiaohongshu platform, local cultural symbols are influenced by the interplay of platform architecture, user practices, and cultural resources, resulting in selective amplification, templated reorganization, and decontextualized circulation, which systematically reshape collective perceptions and cultural identities associated with localities. A significant observation is made: the macro symbol ‘Jiangnan’ is more prevalent in the TOP30 content of five ancient towns than any particular local designation. The platform employs a gatekeeping selection system that functions as a ‘culture gatekeeper’. Macro symbols embody a wider cultural imagination, resonate with a larger audience, and inherently garner greater participation. Algorithms that organize content according to interaction data exemplify Gillespie’s (2014) [38] notion of ‘algorithmic visibility.’ The pairing of ‘Xitang’s Misty Rain Corridor + Hanfu Photos’ exemplifies a typical scenario: its significant visual appeal fosters high engagement, prompting the algorithm to disseminate it to a broader audience, so inciting imitation and establishing a positive feedback loop. The templating effect of symbols occurs simultaneously and subtly. The analysis of the TOP30 content from the five ancient towns reveals a frequent recurrence of terms such as ‘guide’, ‘recommendation’, ‘check-in’, and ‘photo’, appearing between 8 and 13 times, accompanied by notably similar narrative structures. This is not a coincidence; it illustrates the impact of platform discourse rules and the demonstrative effect of successful examples in shaping content creation. Users inadvertently emulate these templates. The circulation process also involves a decontextualization of symbols. Within the discourse concerning these five ancient towns, ‘Hanfu’ is commonly mentioned; yet, there is a paucity of talks regarding its linked dress culture or historical beginnings. It is frequently utilized as a prop in photography to augment visual allure. Appadurai (1996) [39] characterized this phenomenon as ‘cultural de-territorialization’, when local symbols dissociate from their original context via digital dissemination, resulting in a dilution of their cultural significance. The four interrelated effects jointly facilitate the digital restoration of local cultural symbols’ meanings.

5.4. The Platformization Dilemma of Local Attributes: The Paradox of Distinctive Endeavors and Uniform Outcomes

5.4.1. The Five Ancient Settlements Demonstrate Distinct Strategies

Although the five ancient towns exhibit distinct emphases—Xitang foregrounds visual performativity (TOP-30 total frequency = 3965); Wuzhen stresses immersive experiences (12 interactive terms; 1386 occurrences); Zhouzhuang highlights historical tradition (11 cultural terms); Tongli shows balanced complexity; and Nanxun underscores cultural depth—closer analysis reveals three convergences that narrow these differences: (1) the primacy of interactive symbols, with 8–13 interactive entries per town and “strategy” consistently in each TOP-30s top three; functional, guide-type vocabulary is easier to produce and garners more “favorites”, instrumentalizing representations from “a cultural space to understand” into “a site to navigate”; (2) the abstraction of macro-symbols, as “Jiangnan” ranks #1 across all TOP-30s and, as an inclusive and ambiguous meta-symbol, is algorithmically prioritized, generating symbolic upward drift that replaces local distinctiveness with a generic “Jiangnan ancient town” and erodes localness; and (3) the replication of proven templates, whereby Xitang’s “Hanfu photography” and Wuzhen’s night-tourism economy diffuse to peers, exemplifying institutional isomorphism under uncertainty, while “popular-post” features and algorithmic rewards further incentivize mimicry, accelerating homogenization and exposing a structural tension between local culture and platform logic.

5.4.2. Platform Characterization and Field Verification

Multi-day fieldwork in all five towns triangulates the digital findings. Heavily mentioned check-in points—Xitang’s Misty Rain Corridor, Nanxun’s Zhang Shiming Residence, Wuzhen’s nightscape—exist as described and draw significantly higher visitor density than adjacent areas. Many visitors used phones to reproduce identical camera angles from platform images, confirming that influencer strategies reshape on-site behavior and further instrumentalize cultural spaces.

Field observations also reveal gaps between platform narratives and physical realities. Xitang’s “Hanfu experience”, idealized online as traditional aesthetics, appears on site as a commercial cluster of rental shops and soliciting photographers—an approach quickly replicated by other towns. Zhouzhuang, cast online as the “prototypical Jiangnan ancient town”, aligns with posts critiquing it as crowded and congested. Overall, platforms selectively amplify visually pleasing elements—serene waterways, classical facades, staged performances—while systematically downplaying the frictions and constraints that shape actual visitor experience.

5.5. Research Contributions and Practical Implications

This study proposes the theoretical framework of the ‘Media Platform Symbolic Effect’, which is realized through four mechanisms: symbol selection, amplification, modeling, and decontextualization. This approach goes beyond current research that focuses only on mediatization, symbolization, or platformization, clarifying the internal logic of local cultural reconstruction in the digital age. It enhances understanding of the role of media in cultural reconstruction under mediatization theory [19], expands the application of semiotic theory [22,37] in digital media contexts, and elaborates on the theoretical discussion of ‘platform logic’ in platform studies [23,38]. This study demonstrates the integration of computational methods (word frequency statistics) with statistics, TF-IDF, co-word analysis, and theory-driven semiotic analysis, establishing a three-level analytical framework of ‘word frequency statistics—symbol classification—meaning interpretation’. This method naturally integrates the advantages of quantitative scale with the richness of qualitative interpretation, providing a reproducible research framework for cultural communication studies. Practically, it offers ideas for the digital transformation of cultural tourism. It maps out the intersection of ‘cultural connotation and platform preference’, for example, enhancing the composite narrative of Nanjing’s ‘gentry culture + architectural visuals’; creating immersive online-offline experiences similar to the Wuzhen Theater Festival model, turning traffic into cultural participation; and balancing ‘exposure’ with ‘cultural depth’.

6. Conclusions

Based on social media environments, this study constructs a four-dimensional framework—‘natural symbols, cultural symbols, interactive symbols, and emotional symbols’—and systematically analyzes the media construction logic of Jiangnan ancient towns on Xiaohongshu.

Through content mining and symbol coding of 1000 user posts, it reveals how the ‘Seeding Strategy’ mechanism drives the visual translation, emotional attachment, and identity construction of local culture. The study proposes the concept of ‘symbol effects on media platforms’, providing a new theoretical perspective and practical approach for understanding how social platforms reshape local imaginations.

6.1. Constraints

This study has developed a systematic analytical model; yet, it possesses several limitations. The data source is restricted; this study exclusively examines graphic content on the Xiaohongshu platform and omits other social media platforms such as Douyin and Bilibili. Secondly, the distinctiveness of geography and culture: the research concentrates exclusively on five historic towns in the Jiangnan region, which possess analogous cultural traditions (water town culture), geographical characteristics (Yangtze River Delta), and developmental phases (established tourist sites). This study utilizes lexical-level semiotic analysis. Although it can proficiently discern patterns of symbol distribution, its capacity to capture intricate narrative frameworks and discourse tactics is constrained.

6.2. Prospective Research Avenues

Future research may go in the subsequent avenues: Initially, incorporate a wider array of platforms to systematically analyze the variances in place representation across different social media types, thereby establishing a more universally applicable analytical approach. Secondly, integrate methodologies such as emotion detection, machine learning, and neural networks to measure the dynamic interplay between Sentiment symbols and place identification. Third, convert study findings into practical branding and distribution strategies for cultural tourism, providing operational assistance for the media transformation and sustained communication of local cultural venues. Fourth, engage with local administrations and cultural tourist agencies to conduct collaborative research, mutually investigating the equilibrium between algorithmic logic and cultural logic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.W. and H.Z.; methodology, X.W. and H.Z.; software, X.W. and H.Z.; validation, X.W.; formal analysis, X.W.; investigation, X.W.; resources, X.W. and H.Z.; data curation, X.W. and H.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, X.W.; writing—review and editing, H.Z.; visualization, H.Z.; supervision, H.Z.; project administration, X.W. and H.Z.; funding acquisition, H.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Research was supported by Macao Polytechnic University (RP/FCHS-02/2025).

Data Availability Statement

Authors may be contacted for further details if required.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- He, J.W.; Henwood, M. Understanding the urban form of China’s Jiangnan Watertowns: Zhouzhuang and Wuzhen. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2015, 26, 73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.-F.; Zhu, Y.-B.; Wu, H.-H.; Li, F. Are there any differences in the tourists’ perceived destination image between travel e-commerce platforms and social media platforms? Tour. Crit. Pract. Theory 2024, 5, 229–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, A.; Schade, M. Symbols and place identity: A semiotic approach to internal place branding–case study Bremen (Germany). J. Place Manag. Dev. 2012, 5, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavaratzis, M.; Ashworth, G.J. City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2005, 96, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pike, S. Destination brand positions of a competitive set of near-home destinations. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, A.M.; Haenlein, M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of Social Media. Bus. Horiz. 2010, 53, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, W.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yue, Y. User-generated content and its applications in urban studies. In Urban Informatics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 523–539. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, A. Imagining the Xiaohongshu City: Platform Urbanism, Social Media Practices and Urban Culture. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Macau, Macau, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Bailey, A. Affective encounters and urban heritage: Unpacking the interface/city assemblages of online Hanfu performances. Emot. Space Soc. 2024, 53, 101053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, T. Place: An Introduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Whelan, Y. Heritage, Memory and the Politics of Identity: New Perspectives on the Cultural Landscape; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, Y.; Chen, J.S.; Tsaur, S.-H. Destination experiencescape for Hanfu tourism: Scale development and validation. J. Vacat. Mark. 2025, 31, 314–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porfyriou, H. Urban heritage conservation of China’s historic water towns and the role of Professor Ruan Yisan: Nanxun, Tongli, and Wuzhen. Heritage 2019, 2, 2417–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, L.; Liao, T. Mobile geotagging: Reexamining our interactions with urban space. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2011, 16, 407–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hennig-Thurau, T.; Gwinner, K.P.; Walsh, G.; Gremler, D.D. Electronic word-of-mouth via consumer-opinion platforms: What motivates consumers to articulate themselves on the internet? J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 38–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freberg, K.; Graham, K.; McGaughey, K.; Freberg, L.A. Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality. Public Relat. Rev. 2011, 37, 90–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, T.; Eastin, M.S.; Bright, L. Exploring consumer motivations for creating user-generated content. J. Interact. Advert. 2008, 8, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munar, A.M.; Jacobsen, J.K.S. Motivations for sharing tourism experiences through social media. Tour. Manag. 2014, 43, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N.; Hepp, A. The Mediated Construction of Reality; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hjarvard, S. The Mediatization of Culture and Society; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Barthes, R. Image-Music-Text; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1977; Volume 6135. [Google Scholar]

- Eco, U. A Theory of Semiotics; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1979; Volume 217. [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijck, J.; Poell, T.; De Waal, M. The Platform Society: Public Values in a Connective World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T. Custodians of the Internet: Platforms, Content Moderation, and the Hidden Decisions that Shape Social Media; Yale University Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Munar, A.M.; Gyimóthy, S.; Cai, L. Tourism Social Media: Transformations in Identity, Community and Culture; Emerald Group Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, R.; Buchanan, J. Traditional visual language: A geographical semiotic analysis of indigenous linguistic landscape of ancient waterfront towns in China. Sage Open 2022, 12, 21582440211068503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, E. Place and Placelessness; Pion: London, UK, 1976; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. Cultural effects of authenticity: Contested heritage practices in China. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2015, 21, 594–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plantin, J.-C.; Lagoze, C.; Edwards, P.N.; Sandvig, C. Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media Soc. 2018, 20, 293–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Bramwell, B. Heritage protection and tourism development priorities in Hangzhou, China: A political economy and governance perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 988–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-F.; Tsai, D. How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions? Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, D.; Law, R. Progress in information technology and tourism management: 20 years on and 10 years after the Internet—The state of eTourism research. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 609–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urry, J. The tourist gaze “revisited”. Am. Behav. Sci. 1992, 36, 172–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S. Culture, Media, Language: Working Papers in Cultural Studies, 1972–79; Routledge: London, UK, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Thrift, N. Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect; Routledge: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, B. Affective atmospheres. Emot. Space Soc. 2009, 2, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthes, R. Image Music Text; Fictional-Critical Writing; Fontana Collins: London, UK, 1977; Volume 67. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, T.; Boczkowski, P.J.; Foot, K.A. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Appadurai, A. Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 1996; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).