Abstract

This study systematically investigates settlement sites that record living patterns of ancient humans, aiming to reveal the interactive mechanisms of human–environment relationships. The core issues of landscape archeology research are the surface spatial structure, human spatial cognition, and social practice activities. This article takes the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang, Neihuang County, Anyang City, Henan Province, as a typical case. It comprehensively uses ArcGIS 10.8 spatial analysis and remote sensing image interpretation techniques to construct spatial distribution models of elevation, slope, and aspect in the study area, and analyzes the process of the Yellow River’s ancient course changes. A regional historical geographic information system was constructed by integrating multiple data sources, including archeological excavation reports, excavated artifacts, and historical documents. At the same time, the sequences of temperature and dry–wet index changes in the study area during the Qin and Han dynasties were quantitatively reconstructed, and a climate evolution map for this period was created based on ancient climate proxy indicators. Drawing on three dimensions of settlement morphology, architectural spatial organization, and agricultural technology systems, this paper provides a deep analysis of the site’s spatial cognitive logic and the ecological wisdom it embodies. The results show the following: (1) The Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty settlement site reflects the efficient utilization strategy and environmental adaptation mechanism of ancient settlements for land resources, presenting typical scattered characteristics. Its formation mechanism is closely related to the evolution of social systems in the Western Han Dynasty. (2) In terms of site selection, settlements consider practicality and ceremony, which can not only meet basic living needs, but also divide internal functional zones based on the meaning implied by the orientation of the constellations. (3) The widespread use of iron farming tools has promoted the innovation of cultivation techniques, and the implementation of the substitution method has formed an ecological regulation system to cope with seasonal climate change while ensuring agricultural yield. The above results comprehensively reflect three types of ecological wisdom: “ecological adaptation wisdom of integrating homestead and farmland”, “spatial cognitive wisdom of analogy, heaven, law, and earth”, and “agricultural technology wisdom adapted to the times”. This study not only deepens our understanding of the cultural value of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang, but also provides a new theoretical perspective, an important paradigm reference, and a methodological reference for the study of ancient settlement ecological wisdom.

1. Introduction

In 2021, the National Cultural Heritage Administration issued the “14th Five-Year Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Major Sites”, proposing to perform a good job in the protection and utilization of significant sites, to make the heritage displayed on the vast land “come alive”, improve the level of display and utilization, and tell the story of Chinese characteristic sites well [1]. The core category of ecological wisdom focuses on the handling of the relationship between humans and nature. As carriers of human production and living activities, settlement sites provide detailed records of ancient human living patterns and farming methods, demonstrating a significant intersection with ecological wisdom research. Landscape archeology emphasizes the human understanding of the surrounding environment during the process of transforming nature, revealing the interactive relationship between human activities and the natural environment. Ecological wisdom research based on settlement sites exhibits typicality, and the combination of landscape archeology theory is prone to coupling effects. Therefore, within the theoretical framework of landscape archeology, systematically understanding the intrinsic value contained in archeological sites and interpreting their ecological wisdom to promote the adequate protection and utilization of these sites has become a research topic that urgently needs further exploration.

Landscape archeology emphasizes the examination of archeological sites within a broad geographical and cultural context, focusing on the long-term interaction between human activities and the natural environment and their shaping effect on cultural evolution. In addition to simply reconstructing ancient environments or describing the distribution of archeological sites, this theory attempts to interpret the deep meanings inherent in landscapes as carriers of social memory, cultural identity, and power relations.

However, the current interpretation of the value of settlement sites generally focuses on material remains and socio-economic aspects, lacking relevant research on the behavioral patterns and theoretical systems formed by ancient people in their long-term practice of adapting, utilizing, and transforming the natural environment, that is, the ecological wisdom contained therein.

Therefore, this study combines the analytical perspective of landscape archeology with the theory of ecological wisdom to deepen the understanding of the overall intrinsic value of settlement sites, and thus more comprehensively reveal the value composition of settlement sites, providing a new perspective and approach for further revealing the connotation and value of ancient cultural relics.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Analysis of Related Concepts

Landscape archeology is an important branch of archeology that mainly studies the material remains left by human activities in the landscape. Landscape archeology emphasizes the examination of sites within a broad geographical and cultural context [2], focusing not only on ancient sites themselves but also on the surrounding environment and regional background to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the interaction between humans and the environment [3]. In recent years, the theoretical development of landscape archeology has been rapidly advancing, Tim Ingold (1993) [4] proposed that landscape is essentially a temporal phenomenon, a product of continuous interaction between various life activities and the environment. It requires us not only to pay attention to the landscape state at a certain moment, but also to trace the formation trajectory and change rhythm of the landscape. In a 1994 book entitled A Phenomenology of Landscape Places, Paths and Monuments, Christopher Tilley [5] proposed a phenomenological approach to landscape, which specifically focuses on how the material attributes of landscapes are perceived and given meaning by human subjects, and how this meaning in turn affects human spatial behavior and social practices. The Encyclopedia of Archaeology [6] points out that different perspectives on landscape archeology share a central focus on how humans interact with the surrounding world. The characteristics of landscape archeology are comprehensive and interdisciplinary. Knapp, A. B. et al. [7] discussed that in sociology, landscape archeology mainly focuses on the inheritance of cultural memory; regarding ecological research, Godwin, H. [8] suggests restoring the regional topography of specific historical periods through archeological excavations of ancient environmental relics; in the field of settlement morphology archeology, Gosden, C. et al. [9] pointed out that the research perspective should gradually expand to a broader area beyond the site itself; and in the theoretical research of post process archeology, MacAnany, A. [10] explained that social relationships should be analyzed in depth, and the land where humans reside should be regarded as a medium for carrying and expressing various social relationships.

Settlement sites refer to various forms of valuable agricultural settlements of human beings [11]. As important places for ancient production and life, they objectively reflect the geographical spatial characteristics under the long-term interaction of human land relations [12]. Studying the historical evolution of the spatial distribution and form of settlement sites has enlightening significance for exploring ancient social structures [13]. The spatial form of settlement sites, as a concrete manifestation of ancient humans occupying the earth’s surface and carrying out a series of production, life, and social activities, interacts with natural environmental factors. It reflects the layout characteristics, construction techniques, and farming methods of settlements in a specific historical period. Liu, W. et al. [14] explored the relationship between different spatial organizational structures and their integration with the surrounding natural environment. Jiang, B. et al. [15] discussed the natural driving forces that affect the spatial distribution of settlements. Liu, H. [16] summarized the layout and form of Han Dynasty settlements in the Central Plains region, as well as the characteristics of residential courtyard layout and architectural level.

Ecological wisdom represents the wisdom generated by the harmonious coexistence between humans and nature under certain social conditions. It is the general term for the achievements of the relationship between humans and nature that humans have obtained through long-term production and life processes [17]. The goal of ecological wisdom is to foster a harmonious relationship between humans and the environment [18]. The theoretical source of ecological wisdom can be traced back to Aristotle’s description of phronesis, i.e., practical wisdom, he emphasized that practical wisdom should have the ability to make wise judgments in specific situations, it differs from Socrates’ proposal of sophia, i.e., theoretical wisdom. Arne Naess [19] proposed “ecosophy” in 1973, defined as “an individual’s personal ‘philosophy of ecological harmony or equilibrium’”, emphasizing the theoretical pursuit of ecological harmony by individuals. Baltes, P. B. et al. [20] defined wisdom as “an expertise in the conduct and meaning of life”. Flyvbjerg, B. et al. [21] elucidate that phronesis is the practical wisdom “on how to address and act on social problems in a particular context”. W. N. Xiang [22] proposed that ecological intelligence should include both sophia and phronesis: “the concept of ecological wisdom in the context of ecological research, planning, design, and management connotes both sophia and the Aristotelian concept of phronesis, and embraces both individual and collective knowledge”, he defined “ecophronesis” as “the master skill par excellence of moral improvisation to make, and act well upon, right choices in any given circumstance of ecological practice”. Yan, W. et al. [23] systematically discussed the ecological wisdom of Dujiangyan Irrigation Project Irrigation District as a model of traditional human settlement, and summarized the human water relationship and settlement mode from the historical evolution.

From the perspectives of core concepts and research approaches, both landscape archeology and ecological wisdom studies are dedicated to understanding and explaining the complex and profound interactive relationships between human systems and environmental systems. They employ holistic and cross-disciplinary modes of thinking, oppose examining issues in isolation, and pursue multidimensional, multiscale integrated comprehension.

In terms of the temporal dimension, both fields maintain a profound historical vision, focusing on the generation, accumulation, and evolution of wisdom rather than on a static state. Regarding practical orientation, ecological wisdom research grounded in landscape archeology transcends purely theoretical discourse. It places significant emphasis on concrete human practices, behavioral decision-making, and their tangible outcomes within specific environments. Moving beyond mere objective description, it delves into the cultural significance and social values underlying observable phenomena.

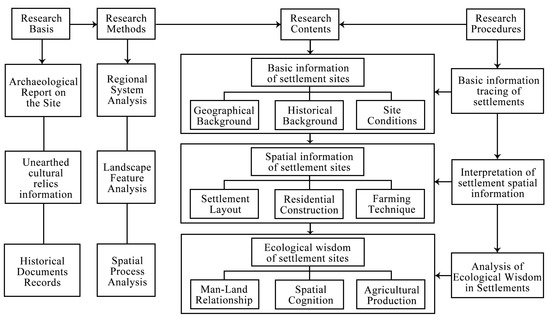

The ecological wisdom research of settlement sites from the perspective of landscape archeology can be broken down into three key components: basic information tracing, spatial information interpretation, and ecological wisdom analysis. Using research methods such as regional system analysis, landscape feature analysis, and spatial process analysis, this study interprets spatial features through literature analysis and image translation, summarizes the ecological wisdom of human land relationships, spatial cognition, and production methods, and comprehensively understands the development process of the Han Dynasty settlement in Sanyangzhuang (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A research framework for ecological wisdom of settlement sites based on landscape archeology.

2.2. Tracing the Basic Information of the Han Dynasty Settlement Site in Sanyangzhuang

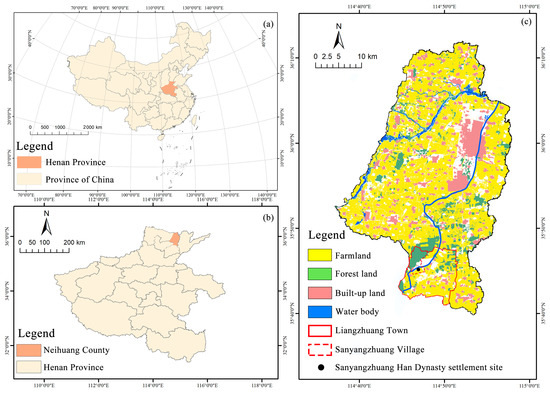

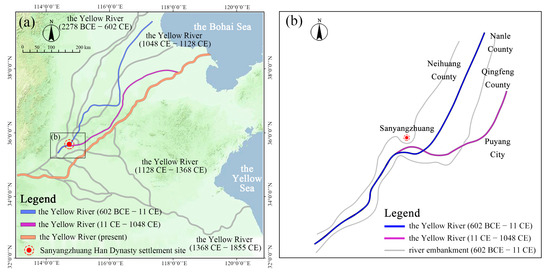

The Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty settlement site is located in Sanyangzhuang Village, Liangzhuang Town, Neihuang County, Anyang City, Henan Province. It is situated on the old course of the Yellow River and dates back to the late Western Han Dynasty to the early Eastern Han Dynasty (around 50 BCE to 50 CE) [24] (Figure 2). Within the scope of archeological exploration, 14 Han Dynasty courtyards, roads, lakes, ponds, farmland, and other remains have been discovered. Four of the courtyards have been excavated and cleared, with a total area of 9000 square meters. For the first time, the agricultural production status, rural social forms, and living conditions of farmers in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River during the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 8 CE) have been visually reproduced. It is a site of great value, rich connotation, and far-reaching influence [25]. In 2010, it was selected for the first batch of national archeological site park projects.

Figure 2.

Location analysis map of the research area. (a) Location of Henan Province on the map of China. (b) Location of Neihuang County on the map of Henan Province. (c) Location of the study area on the map of Neihuang County. The base map is taken from the standard map service system (http://bzdt.ch.mnr.gov.cn/index.html, accessed on 20 October 2025).

Landscape archeology is a comprehensive method that combines “on-site” and “off-site” research [26], which not only examines human activities themselves but also considers the spatial context of these activities. It is a truly comprehensive regional integrated surface study [3]. Based on the essence of this research, the basic information of the Sanyangzhuang site should be traced back to the geographical, historical, and site conditions of the area during the Western Han Dynasty. Among them, the geographical background should focus on the comprehensive information construction at the macro level, including terrain and landform characteristics, climate characteristics, and the historical changes in the Yellow River in the region.

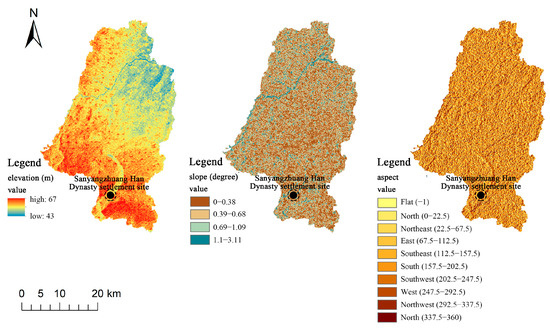

Sanyangzhuang is located in the old course of the Yellow River, in an open beach area downstream of the Yellow River. The surrounding terrain is relatively flat, but a sediment accumulation layer has formed after the Yellow River floods (Figure 3). From the late Western Han Dynasty to the early Eastern Han Dynasty (around 50 BCE to 50 CE), Sanyangzhuang was located in a relatively low-humidity environment on the North China Plain, characterized by a cold and arid climate with little precipitation (The figure of climate change can be found in the Supplementary File). During the Western Han Dynasty, the implementation of a system to cultivate farmland led to extensive cultivation, and forests in hilly and plain areas began to suffer severe damage.

Figure 3.

Elevation, slope, and aspect map of the research area.

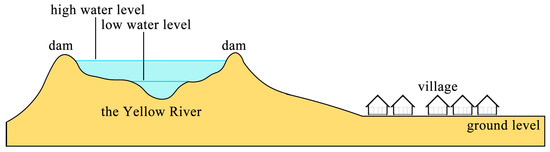

Under the dry climate in the inland it caused severe soil erosion and desertification, and the ecological environment deteriorated. Sedimentation in rivers caused the riverbed to rise constantly. The “Book of Han: Gully Records” records: “At the age of six or seven, the river water surged, increasing by seven zhang and seven chi (approximately 231 cm per zhang and 23.1 cm per chi during the Western Han Dynasty), damaging the south gate of Liyang and entering below the embankment. The water did not exceed two chi from the embankment. Looking north from the embankment, the river was higher than the houses of the people, and they walked up the mountain. After thirteen days of water retention, the embankment collapsed, and the officials and people blocked it.” [27]. This record shows that in the late Western Han Dynasty (around 7 BCE), the Yellow River had already formed a suspended river situation near Liyang (Xun County, Hebi City, about 5 km away from Sanyangzhuang), which was higher than the surrounding houses (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Diagram of the Yellow River becoming an above-ground suspended river.

The formation of settlements was influenced by the flooding of the Yellow River. From archeological investigations and excavations, it is evident that Sanyangzhuang was situated on the convex bank of the Yellow River bend during the Western Han Dynasty, and the accumulation of sediment was conducive to agricultural production activities [28]. After the mid-Warring States period (around 350 BCE), embankments were built on both sides of the Yellow River, and people began to cultivate within the embankments, forming a specific scale of settlements [29]. The “Book of Han: Gully Records” records: “At this time, it was filled with silt and fertile land, and the people cultivated the fields. It may have been harmless for a long time, and a few houses were built, thus forming a settlement [27]. In the third year of Xinmang’s founding (11 CE), after the “River Conquers Wei Commandery”, the location of Sanyangzhuang changed from a convex bank to a concave bank, becoming an object of river erosion (Figure 5), and was eventually buried by floods and sediment.

Figure 5.

(a) Diagram of each diversion of the Yellow River. (b) Diagram of the relationship between the Yellow River and Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty Settlement Site in the Western Han Dynasty. The grey line in (a) is the old courses of the Yellow River during other periods that are not within the research time range.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Interpretation of Spatial Information of Han Dynasty Settlement Site in Sanyangzhuang

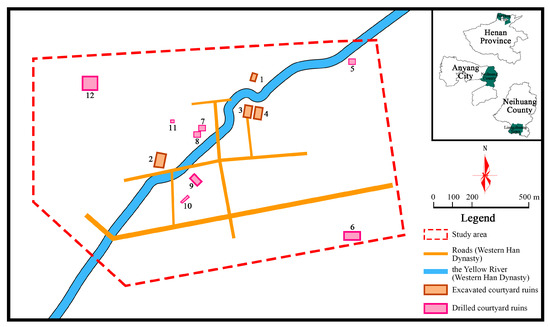

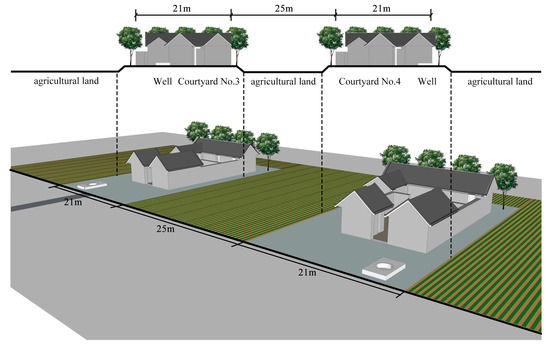

During the Han Dynasty (202 BCE to 220 CE), Neihuang County was part of Fanyang County and fell under the jurisdiction of Wei Commandery. The Han dynasty inherited the Qin dynasty’s system and implemented an administrative management system of commander, county, township, and village (li). As the most basic management unit, a “li” implements the system of “five households as neighbors, five neighbors as li, and twenty-five households as one li”. The excavation method is the large-scale exposure method, which involves meticulous cleaning layer by layer to protect and display the original site, and fully restores the spatial structure of the Han Dynasty agricultural settlement [30]. To date, 14 Han Dynasty courtyards, comprising 14 households, have been discovered at the Sanyangzhuang site. The four excavated courtyards all face north and south in the same direction (approximately 10° southwest), forming a two-courtyard layout [31] (Figure 6). Each family’s courtyard is situated in its own field, with large areas of farmland separating the courtyards, and clear ridges visible in the farmland. These courtyards are neither organized nor listed, and they are in a completely scattered form [32].

Figure 6.

Location and Composition of the Han Dynasty Settlement Site in Sanyangzhuang.

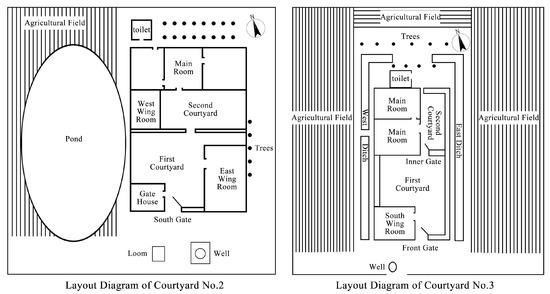

Courtyard No. 2 is located in the northwest direction of Sanyangzhuang Village, with an area of nearly 2000 square meters, and the site has been fully exposed. The first courtyard includes the courtyard wall, south gate, west gate room, and east wing room. Outside the south gate, there are weaving remains, a water well, and a brick-paved path leading from the water well to the south gate. The second courtyard includes the courtyard wall, the west wing room, and the main room. The toilet is located in the northwest, adjacent to the courtyard. An oval-shaped pond was excavated on the west side of the courtyard, surrounded by north–south ridges on the east, north, and west sides [33]. The area of the courtyard No. 3 is approximately 900 square meters. The first courtyard has a courtyard wall, a south gate, and a south wing room. The second courtyard features a main room facing west and a toilet located on the west side, outside the back gate. Multiple clear ruts and cow hoof marks were found in the open space outside the south gate. There are two rows of tree remains on the north side of the courtyard, which are judged to be mulberry and elm trees based on the remaining leaf traces. Field ridges surround them, and there are water ditches on the west and east sides (Figure 7). Courtyard No. 4 is located 25 m east of Courtyard No. 3, with a layout similar to that of Courtyard No. 3, except that there is no ditch on the west side of the courtyard, but a row of north–south trees [34].

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of courtyard layout for No. 2 and No. 3 of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang.

Among the four excavated courtyard sites, Courtyard 2 has a large number and area of houses, with a building length of 70 chi from east to west and a north–south length of 101.5 chi (approximately 23.1 cm per chi during the Western Han Dynasty). The layout, streamlined organization, and spatial composition all reflect the relatively mature level of construction at that time.

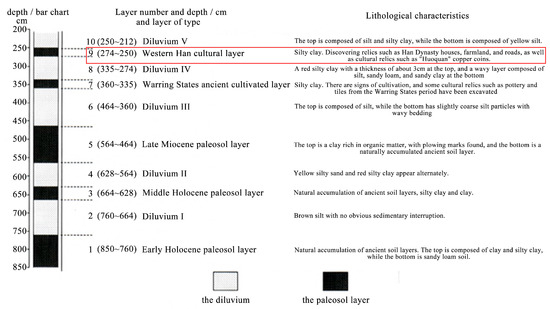

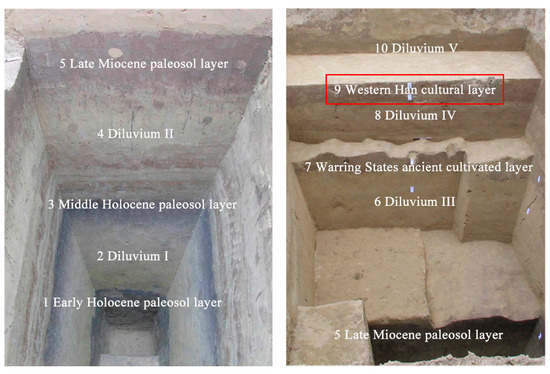

According to the analysis of the geological structure and soil texture of the Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty settlement site, the ancestors of the Han Dynasty cultivated on relatively fertile soil formed by flooding and alluvial deposits of the Yellow River. The cultural layer of the Han Dynasty was mainly composed of silty clay and silty loam, which were more conducive to agricultural production compared to the sandy land caused by flooding from the Yellow River. The soil had strong permeability, and the possibility of long-term waterlogging or surface runoff was relatively small (Figure 8). Therefore, at that time, residents risked being flooded by the Yellow River to cultivate farmland on the riverbank and eventually settled down [35] (Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the stratigraphic section of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang. The red box in the picture indicates the lithological characteristics of Western Han cultural layer.

Figure 9.

Archeological photos of the Han Dynasty settlement site section in Sanyangzhuang. The red box in the picture indicates the section of Western Han soil layer.

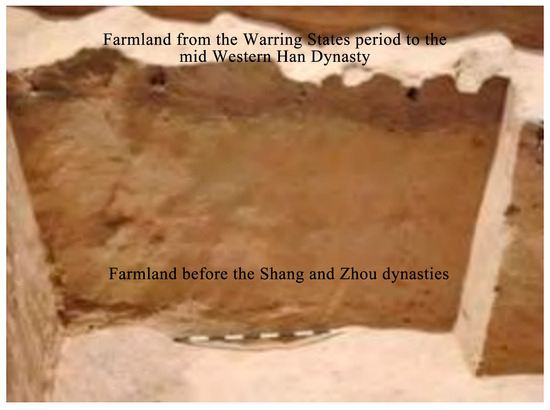

The vast remains of cultivated farmland revealed by the Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty settlement site provide valuable physical evidence for a deeper understanding of Han Dynasty agricultural cultivation techniques (Figure 10). The width of a ridge or ditch in the ruins is generally 60 cm, and the height from the highest point to the lowest point is about 6 cm. Large areas of farmland ruins were discovered around each courtyard, presenting a pattern of alternating ridges and ditches. Taking the courtyard No. 3 as an example, the overall direction of Tianlong has two directions: east–west and north–south, with the north–south direction being the most common [36] (Figure 11).

Figure 10.

Archeological photo of the farmland site on the west side of Courtyard No. 3 of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang (from northwest to southeast).

Figure 11.

Archeological photos of farmland profiles discovered at the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang.

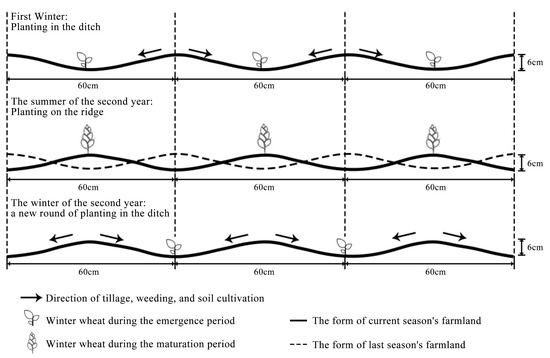

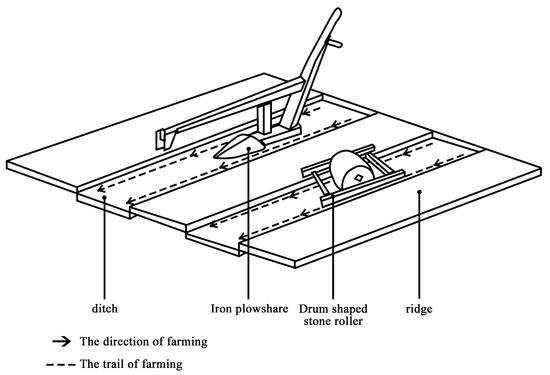

The farmland cultivation in Sanyangzhuang employs the Daitian method, which is a farming method invented and promoted by the agricultural scholar Zhao Guo during the mid-Western Han Dynasty. The specific operation involves opening three trenches, each one foot wide and one foot deep, on a long strip of land measuring one acre in area. Firstly, the soil in the farmland is plowed and sorted. When sowing, the flat soil to be planted is trimmed into a pattern of alternating ridges and ditches. Then, crop seeds are sown in the ditches. During the implementation of weeding and soil cultivation, the soil on the ridges is gradually pushed into the ditches to cultivate crops. In the second year, the positions of the ditches and ridges are exchanged [37]. The positions of ditches and ridges rotate every year, hence they are called ‘daitian’ (‘dai’ means replace, ‘tian’ means farmland). Sow in the ditches in winter, and the seedlings grow up in summer. After soil cultivation, it becomes ridges tillage (Figure 12). Based on the analysis of geographical and environmental conditions in the previous text, agricultural production in Sanyangzhuang during the Han Dynasty was characterized by a northern dryland agricultural system, primarily focused on drought resistance and soil moisture preservation. This farming method is beneficial for maintaining soil fertility and plays a role in preventing wind and drought. It has the following technical characteristics: firstly, alternating ditches and ridges. The seeds are sown in the ditches, and after emergence, the soil on the ridges is filled into the ditches by combining with tillage and weeding. Its function is to prevent wind, lodging, moisture, and drought. The second is the exchange of ditches and ridges. The positions of ridges and ditches rotate year by year, and since crops are always sown in ditches, the exchange of ridges and ditches achieves the purpose of land rotation and utilization. Therefore, the Daitian method is actually a precision farming technology system, which is adopted to address the problems of soil fertility decline, drought, and other conditions encountered in agricultural production. It is a systematic technology that integrates soil fertility, drought resistance, moisture retention, wind resistance, and lodging prevention, thereby improving production efficiency and increasing crop yields.

Figure 12.

Schematic diagram of farmland planting methods in the Han Dynasty settlement site of Sanyangzhuang.

3.2. Ecological Wisdom Analysis of the Han Dynasty Settlement Site in Sanyangzhuang

The origin of agricultural ecological wisdom in China can be traced back to ancient times. “Zhuangzi” is a work of philosopher Zhuang Zhou during the Warring States period (around 300 BCE) and a classic of Taoism. The statement in Zhuangzi’s “Qi Wu Lun” that “heaven and earth coexist with me, and all things are one with me” reflects the philosophical idea of the unity of heaven and human, which holds that humans and the natural world are interdependent entities. This concept emphasizes respect for natural laws and is manifested in the harmonious unity of heaven, earth, and human in the agricultural system, forming the foundation of agricultural ecology, namely the “Three Talents” theory. Among them, “heaven and earth” refer to the external environment in which crops grow and develop; ‘human’ refers to social practice [38], and the fundamental purpose of agricultural production is to meet the basic needs of human survival. The ancients emphasized actively adapting to the natural environment and pursuing harmony between humans and the natural environment from a people-oriented perspective, forming a unique ancient Chinese agricultural ecological wisdom [39].

The forms of agricultural settlements in the Han Dynasty were divided into three types: walled inner settlements within cities, relatively concentrated inner settlements outside cities, and scattered natural settlements [40]. During the Qin and Han dynasties, the Lüli system was a management system implemented in cities, which divided residents into regions and implemented strict household registration management and residential restrictions. After the mid-Western Han Dynasty, with economic development and social stability, population growth led to the continuous emergence of new settlements, resulting in diverse settlement forms characterized by dispersion, openness, and close integration with agricultural production.

The courtyards of Sanyangzhuang are closely connected to farmland, with farmland separating the courtyards, presenting a layout of “land and houses connected, and houses built in fields” [25] (Figure 13). This form is significantly different from traditional Lüli settlements: Lüli settlements are usually closed, with walls and gates, and residents live in concentrated areas; However, Sanyangzhuang does not have walls, and the courtyards are scattered across vast fields, with a relatively long distance between neighbors. Unlike other places that require government household registration management, Sanyangzhuang was spontaneously formed to accommodate the convenience of agricultural production and daily life. Due to its location on the Yellow River beach and sparse population, it is suitable for scattered living. Farmers building houses in the fields not only facilitates production but also reduces commuting costs, reflecting their efficient utilization of land resources.

Figure 13.

Schematic diagram of the relationship between the courtyard and farmland of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang.

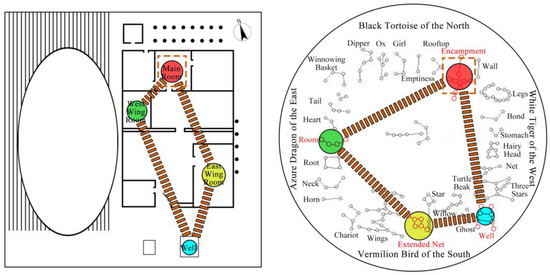

The Twenty Eight Mansions, as a core component of the ancient Chinese astronomical system, are closely related to the layout of courtyards, as reflected in the profound influence of the philosophical concept of “unity of heaven and human” on architectural space. Through directional symbolism, they indirectly shape the order of architectural space. The excavated Courtyard No. 2 has the main room corresponding to the “room” of the Northern Seven Mansions, the west wing room corresponding to the “room” of the Eastern Seven Mansions, and the south side well and east wing room corresponding to the well and Zhang of the Southern Seven Mansions [41] (Figure 14). The four mansions of room, house, well, and Zhang are, respectively, responsible for the core functions of living, storage, water source management, and social etiquette within the courtyard. This layout combines astronomical symbols with practical needs, reflecting the wisdom of ancient architecture’s “analogy of heaven and law of earth”. From a semiotic perspective, the star system centered around the twenty eight mansions is deeply connected to the layout of ancient courtyards, constructing a symbolic coordinate system for ancient architectural spaces. This spatial planning not only meets the needs of daily life but also achieves the translation of astronomical concepts into architectural vocabulary through the symbolic meaning of mansions, endowing buildings with deep cultural connotations and spiritual sustenance.

Figure 14.

Schematic diagram of mansions corresponding to the layout of Han Dynasty courtyards.

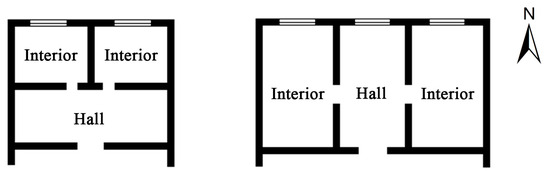

The “one hall and two interiors” is a typical residence for ordinary people in the Han Dynasty (Figure 15), consisting of a “hall” and “two interiors”, with the “hall” as the main space. Reflected in the plane layout, it is usually divided into one “hall” in the center, with “two interiors” on both sides, or one “hall” in the front and “two interiors” in the back. The “hall” is a place for receiving guests and conducting daily activities, while the “interior” is a private space for rest. This layout reflects the ancient family’s emphasis on privacy, as well as their concept of creating functional and dynamic zones.

Figure 15.

Schematic diagram of two planar forms of “one hall, two interiors”.

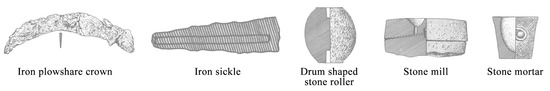

The iron plowshare crown and drum shaped stone roller unearthed from the Sanyangzhuang site are essential agricultural production tools for local farming practices (Figure 16). The double wings of the iron plow are 34–44 cm long and are used for digging ditches and ridges; The drum shaped stone roller is used to press and cover the soil after sowing, with a length of 35 cm when laid flat [24], which is consistent with the pattern of alternating ridges and ditches in the farmland within the site (Figure 17). The use of stone mortar and stone mill for grain threshing and precision grinding, as well as the popularization of iron plowshare and iron sickle, marked the widespread application of iron farming tools during the Western Han Dynasty, providing a solid foundation for the adjustment of farming methods and reflecting a significant improvement in agricultural productivity.

Figure 16.

Farm tools unearthed from the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang.

Figure 17.

Schematic diagram of iron plowshare crown and drum shaped stone roller in farmland cultivation process.

According to the analysis of the climate background in the Sanyangzhuang area in the previous text, drought is the primary factor affecting crop cultivation in this region. Based on the agricultural production situation at that time, it can be observed that dryland crops such as wheat, especially winter wheat, have been widely promoted in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River. The sowing period of winter wheat is generally from late September to early October, and the harvest period is generally in early June of the following year. Therefore, planting winter wheat avoids the rainy season in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River, which also avoids the flood season, reflecting the ancient people’s profound understanding and coordinated adaptation to regional climate.

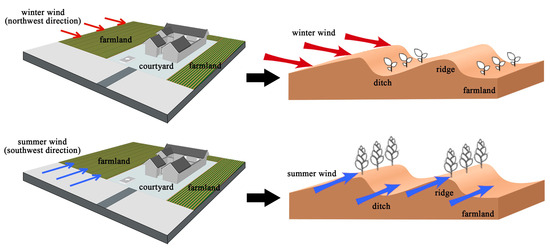

When winter arrives, the Mongolian high pressure system moves from the mainland to the sea, and the northwest wind generated causes a temperature drop in the North China Plain, which can lead to crops suffering from cold and other disasters. Most of the farmland in Sanyangzhuang is surrounded by courtyards, the farmland and courtyards are oriented towards the southwest [36], with a significant angle difference from the winter wind direction, which can to some extent resist the invasion of severe cold and provide protection for seedlings. Under the current conditions of low precipitation and arid climate, sowing winter wheat seeds in ridges and ditches can effectively maintain soil moisture.

In early summer, the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River often experience an arid climate. By implementing tillage management measures, new ridge structures can be formed at the roots of crops, promoting their deep development and improving their resistance to drought, moisture retention, and lodging resistance. In addition, the region is susceptible to dry hot winds, with the influence of southwest winds being the most significant. Given that the layout of the farmland tends towards the southwest, this design is beneficial for improving ventilation conditions in crop fields. (Figure 18). After the summer, the rainy season arrives in the North China Plain, and at this time, farmland gradually undergoes the “replacement” of ridges and ditches, with crops growing on the ridges. The previous ridge was transformed into a ditch, which also serves as a drainage system and is beneficial to prevent waterlogging [42]. Therefore, the carefully designed changes in farmland morphology in Sanyangzhuang are highly conducive to the planting of winter wheat, reflecting the ecological wisdom of ancient people in planting crops in a targeted manner to adapt to different climatic conditions. This is not only an inevitable result of the development of agricultural science and technology itself, but also a reflection of ancient agricultural production adapting to changes in ecological environmental factors [43].

Figure 18.

Schematic diagram of the relationship between winter and summer wind direction and field ridges.

Lastly, climate change not only brings about adaptive changes in agricultural technology, but also profoundly alters people’s theoretical understanding of the regularity of agricultural economic activities, and necessitates agricultural technology measures that adapt to ecological environment changes in the development of social organizational structures. The ecological wisdom of integrating homestead and farmland, the spatial cognitive wisdom of analogy, heaven, law, and earth, and the agricultural technological wisdom adapted to the times are profound manifestations of the “three talents” principle in traditional Chinese agricultural theory. During the Western Han Dynasty, the dryland agriculture culture in the Yellow River Basin of northern China was well-established, as reflected in the people’s philosophical understanding of the objective world. The development of the “Three Talents” theory fully reflected the ancient people’s basic understanding of the dialectical relationship between the material and spiritual, as well as the subjective and objective worlds of heaven, earth, and human, and their adaptive cognition of the changing objective world [44].

4. Conclusions

This study conducted an in-depth analysis of the basic characteristics of changes in the middle and lower reaches of the Yellow River in northern China during the Western Han Dynasty. It systematically revealed the interactive effects of various climate and environmental influencing factors, including temperature and precipitation changes, changes in the old course of the Yellow River, and evolution of domiciliary control system. The gradual shift towards a dry and cold climate led to the abandonment of farming areas and the migration of border residents, which promoted the development of drought prevention and moisture preservation technologies, as well as changes in crop planting structures. Agricultural production activities have gradually adapted and undergone technological changes in response to climate and environmental shifts, reflecting the ecological wisdom of human social behavior in adapting to the natural world and gradually developing practices, understanding, and insights. The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

(1) “ecological adaptation wisdom of integrating homestead and farmland”: The layout of the Han Dynasty settlement site in Sanyangzhuang, where “fields and houses meet, and houses are built in fields”, is a typical scattered form, which originated from the economic development and social stability in the mid-Western Han Dynasty. The scattered settlement form reflects the efficient utilization of land resources by farmers.

(2) “spatial cognitive wisdom of analogy, heaven, law, and earth”: The courtyard layout combines astronomical symbols with practical needs, shaping the order of architectural space through the correspondence of star directions. The “one hall, two interiors” layout reflects considerations for functionality and dynamic and static zoning.

(3) “agricultural technology wisdom adapted to the times”: The ionization of agricultural tools has created the basic conditions for the promotion and development of iron plows and cow plowing, and the development of the Daitian method reflects the corresponding adjustments made by human agricultural activities to adapt to climate change. The ancient people chose the geographical location of crop cultivation and the direction of farmland arrangement based on different climatic conditions to resist the invasion of natural disasters, which, to some extent, reflects the development and maturity of dryland farming systems and agricultural cultures in the Yellow River Basin in the north.

The construction process of ancient settlements demonstrates the ancient people’s understanding, adaptation, and development of the natural environment. In-depth exploration of the interactive effects and adaptation mechanisms between settlement sites and the environment is of great significance for promoting the sustainable renewal and development of traditional settlements. The transmission of knowledge about the historical development and ecological changes in a landscape to current inhabitants establishes a crucial foundation for environmental stewardship [45]. During the critical period of protecting and utilizing large archeological sites in China, this study is based on landscape archeology theory to explore the intrinsic value of settlement sites and analyze the ecological wisdom contained in settlement sites. In this way, it helps to expand the spatial order of historical and cultural heritage [46]. This study offers significant practical implications for the effective implementation of settlement site protection work and provides a broader research perspective to enrich the humanistic connotation of settlement sites.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/heritage8110466/s1, Figure S1: (a) The temperature changes in the eastern and central regions of China during the Qin and Han dynasties in the winter half year; (b) The dry and wet changes in the eastern and central regions of China during the Qin and Han dynasties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T. and H.J.; data curation, Y.C. and H.J.; formal analysis, G.T. and H.J.; funding acquisition, G.T.; investigation, Y.C. and H.L.; methodology, Y.C. and H.J.; resources, Y.C.; supervision, H.J., X.W., E.M., and M.A.M.C.; validation, Y.C.; visualization, Y.C. and H.J.; writing—original draft, Y.C.; writing—review and editing, G.T. and H.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Henan Province Foreign Expert Studio, grant number GZS2025012; research on digital protection and design transformation of agricultural cultural heritage in Henan Province, supported by the humanity and social research funds for the Henan Universities, grant number 2025-ZDJH-570; research on the inheritance and development path of agricultural language in the Central Plains from the perspective of ecolinguistics, supported by the humanity and social research funds for the Henan Universities, grant number 2025-ZDJH-889.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support received from Wei-Ning Xiang for proposing the theory of ecological wisdom in “Ecophronesis: The ecological practical wisdom for and from ecological practice”, which provides important guidance and constructive suggestions for the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- National Cultural Heritage Administration. Notice of the National Cultural Heritage Administration on the Issuance of the “14th Five-Year Plan” Special Plan for the Protection and Utilization of Major Sites; Technology Report; The Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Zhao, J.; Liu, B. Landscape Archeology: Theoretical Evolution, Methodological Applications and Disciplinary Prospects. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2025, 41, 24–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Landscape Archaeology—Theory, Methods, and Practice. Cult. Relics South. China 2010, 4, 8–17. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, T. The temporality of the landscape. World Archaeol. 1993, 25, 152–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, C.Y. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths, and Monuments; Berg: Oxford, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Branton, N. Landscape Approaches in Historical Archaeology: The Archaeology of Places. In International Handbook of Historical Archaeology; Gaimster, D., Majewski, T., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, A.B.; Ashmore, W. Archaeological landscapes: Constructed, conceptualized, ideational. In Archaeologies of Landscape: Contemporary Perspectives; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Godwin, H. History of the British Flora. In A Factual Basis for Phytogeography; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gosden, C.; Head, L. Landscape-a usefully ambiguous concept. In Archaeology in Oceania 29; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1994; pp. 113–116. [Google Scholar]

- MacAnany, A. Living with the Ancestors: Kinship and Kingship in Ancient Maya Society; University of Texas Press: Austin, TX, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, M. List of Chinese Agricultural Cultural Heritage; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 42–43. [Google Scholar]

- Li, N.; Yang, L.; Shen, J.W.; Zhengfang, Z.H.; Yang, Q. Simulating the optimal migration paths between prehistoric settlement sites. J. Geo Inf. Sci. 2019, 21, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W. The Settlement Archaeology and Research of Prehistory. Cult. Relics 1997, 6, 27–35+1. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Liu, D. Interpreting the Information of Spatial Organization and Distribution of Settlements from a Perspective of Landscape Archaeology A Case Study on the Historic Sites of Settlements in Han and Wei Dynasties on Sanjiang Plain. Archit. J. 2019, 11, 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, B.; Cui, J. Spatial characteristics of the Yangshao-Longshan sites and its environmental background in Qishuihe basin. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2017, 31, 63–68. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. Exploration of Han Dynasty settlements in the Central Plains region. Cult. Relics Cent. China 2016, 5, 31–37+47. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, L. Ecological Wisdom and Contemporary Development of Traditional Settlements; Southwest Jiaotong University Press: Chengdu, China, 2019; pp. 53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, W.-N.; Zhou, T. Traditional Ecological Wisdom and Modern Urban Green Space Construction. North. Hortic. 2015, 16, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Næss, A. The shallow and the deep, long-range ecology movement: A summary. Interdiscip. J. Philosophy. 1973, 16, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltes, P.B.; Staudinger, U.M. Wisdom—A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flyvbjerg, B.; Landman, T.; Schram, S. (Eds.) Introduction: New directions in social science. In Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis; Cambridge Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, W.-N. Ecophronesis: The ecological practical wisdom for and from ecological practice. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 155, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Xiang, W.; Yuan, L. Exploring Ecological Wisdom of Traditional Human Settlements in a World Cultural Heritage Area: A Case Study of Dujiangyan Irrigation Area, Sichuan Province. China Urban Plan. Int. 2017, 32, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, H.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, F. Excavation Report on the Second Courtyard of the Han Dynasty Settlement Site at Sanyangzhuang, Neihuang, Henan Province. Huaxia Archaeology 2010, 3, 19–31+158–165+169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Exploring the spatial distribution of “farmland and residences” in the Han Dynasty through the discovery of the Sanyangzhuang site. In Archaeology of the Nanyue Kingdom in the Western Han Dynasty and Han Culture; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, L.; Fu, D.; Zhang, H. Research on wild food resource domains in early agricultural settlements: A case study of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and the Central Plains region. Quat. Sci. 2010, 30, 245–261. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, G. Book of Han; Zhong Hua Book Company: Beijing, China, 1962; pp. 1491–1492. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K. The formation and abandonment of the Han Dynasty settlement at the Sanyangzhuang site. West. Hist. 2021, 2, 176–192. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. A Study on the Agricultural Environment of the Sanyangzhuang Relic in Han Dynasty. Agric. Hist. China 2014, 33, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Zhu, R.; Song, G.; Qiao, L. The Han Dynasty Courtyard Site in Sanyangzhuang, Neihuang County, Henan Province. Archaeology 2004, 7, 34–37+101–102+2. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K. On the Settlement Pattern of the Sanyangzhuang Site in the Han dynasty. Agric. Hist. China 2019, 38, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. Archaeological Research on Agriculture and Rural Settlements in the Pre-Qin and Han Dynasties; Cultural Relics Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2017; pp. 279–280. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.; Cui, Z. Research and Probing Discussion on Reconstruction of the Han Architectural Site of Courtyard Complex 2, Sanyangzhuang Village, Neihuang, Henan Province. Hist. Archit. 2014, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Z.; Lin, Y. Study on the Han Architectural Site of Courtyard Complex 1,3,4, Sanyangzhuang Village, Neihuang, Henan Province. Archit. Cult. 2014, 9, 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K. On the Cultivation Environment and Tillage Method of the Settlement of the Sanyangzhuang Site in the Han Dynasty. Agric. Hist. China 2017, 36, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H. First Discovery of the Han Dynasty Agricultural Neighborhood Site—An Initial Understanding of the Sanyangzhuang Han Dynasty Settlement Site in Neihuang, Henan, China. In French Sinology; Zhong Hua Book Company: Beijing, China, 2006; pp. 69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, K. On the Pattern of the Agricultural Settlement and the Agricultural Technology in Qin and Han Dynasties: Taking Sanyangzhuang Site as the Center for Discussion. Ph.D. Thesis, Zhengzhou University, Zhengzhou, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. Research on Various Issues in the Agricultural Society of the Han Dynasty; China Social Sciences Press: Beijing, China, 2024; pp. 96–97. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Xiao, L. The environmental cognitive basis and related behavioral characteristics of land development in ancient China. J. Shaanxi Norm. Univ. (Philos. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2007, 5, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X. An Archaeological Study of the Agricultural Settlement Pattern in the Han Period. Southeast Cult. 2011, 6, 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Q. An Analysis of the Structure and Layout of Courtyards in the Han Dynasty. Relics Museolgy 2012, 2, 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fu, K. On the Cultivation Technology of the Farmland Trace at the Han Dynastical site of Sanyangzhuang. Agric. Hist. China 2013, 32, 9–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Shang, Q. The Interaction Between Ecological Environment Changes and Social Transformations, Centered on the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yellow River from the Xia Dynasty to the Northern Song Dynasty; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2016; pp. 222–224. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. Climate Change and the Development of Agricultural Technology in the Middle and Lower Reaches of the Yellow River From the Qin and Han Dynasties to the Song and Yuan Dynasties; People’s Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 17–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rossano, P. Paesaggio, culture e cibo. Mutamenti territoriali e tradizioni alimentari in Italia; Istituto Alcide Cervi: Gattatico, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Tian, G.; Wei, K.; Zhang, S.; Huang, Y.; Yao, X. The Influence of Environment on the Distribution Characteristics of Historical Buildings in the Songshan Region. Land 2022, 11, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).