Abstract

This article examines the processes of de-Sovietization of public spaces in Lithuania, focusing on the visual transformation of monuments after the collapse of the Soviet Union. While scholarship has primarily analyzed the dismantling of Soviet monuments as acts of iconoclasm, this study argues that de-Sovietization is a dual process involving both negative and positive dimensions: the removal of Soviet-era symbols and the creation of new monuments that articulate a post-Soviet national narrative. Drawing on Jacques Rancière’s framework of artistic regimes, the article explores how newly constructed or restored monuments embody the search for a new symbolic language of political and social communication. The analysis is based on qualitative content analysis of expert interviews with sculptors, architects, and artists involved in monument-making in Lithuania since 1990. Over the past three decades, more than 400 monuments have been erected in Lithuania, reflecting the tensions between continuity and rupture with Soviet monumentalism. While naturalistic monuments often avoided controversy, projects departing from realistic aesthetics—such as Regimantas Midvikis’ Exploded Bunker and Andrius Labašauskas’ Freedom Hill—became sites of conflict and public debate. By identifying the visual features of positive de-Sovietization, the article contributes to understanding how post-Soviet societies negotiate historical memory, identity, and aesthetic form in public space.

1. Introduction

In 1989–1990, following the collapse of the Iron Curtain, the map of Eastern and Central Europe was reshaped by the states that regained their independence from the former Soviet bloc. The change in regime brought transformations not only in politics and economics but also in social life, culture, historical consciousness, aesthetics, and public spaces. Aesthetic changes in public spaces were especially noticeable, as they were cleared of Soviet monuments that had promoted Soviet values and were known during the Soviet era as examples of monumental propaganda. Although the fate of Soviet monuments varied across former Soviet bloc countries after the fall of the Iron Curtain, many remained in public spaces in Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. In contrast, in the Baltic states and Poland, monuments symbolizing Soviet ideology were swiftly and widely dismantled as the Soviet Union began to collapse, making way for new monuments that reflected the emerging democratic regimes, their values, and aesthetics.

This process is commonly referred to as the de-Sovietization of public spaces, highlighting several waves of de-Sovietization [1]. The first wave of dismantling Soviet monuments coincided with the collapse of the Soviet Union, while the second one emerged in response to the 2014–2015 events in Crimea and its annexation, prompting a renewed removal of remaining Soviet monuments across Eastern and Central Europe. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 prompted several East–Central European countries to revisit their memory politics and reassess the fate of remaining Soviet-era monuments. Whether this was the third wave of de-Sovietization or a continuation of the second one is still a matter of disagreement.

In general, de-Sovietization of public spaces is typically analyzed in terms of the scale and process of removing Soviet monuments in former Soviet Union states such as Estonia [2,3], Poland [4,5], Ukraine [6,7,8], and Latvia [9], with particular attention to the fact that “regime change is often accompanied by the acts of iconoclasm or a purposeful destruction, removal or dismissal of monuments and symbols” [10]. Nevertheless, it is evident that the fate of monuments in the former Soviet bloc countries was neither uniform nor unequivocal, as demolition and removal were not consistent across the region. For example, in Belarus, Soviet monuments have been incorporated into the current narrative [11], while in Kyrgyzstan, they remain part of present-day discourse, although this is balanced by the growing influence of China in the region [12]. Meanwhile, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia have undertaken efforts to distance themselves from the Soviet era by removing Soviet monuments from public spaces. Furthermore, what fills the public spaces cleared of Soviet monumental art is also neither homogeneous nor beyond debate.

Replacing monuments from the old regime with new ones has often triggered contentious debates and societal divisions in East–Central Europe. As the case of Ukraine illustrates, reconciling with both the recent and more distant remains a significant challenge for political elites and ordinary citizens [13]. In Ukraine, discussions have largely centered on the remembrance of divisive figures and organizations, such as the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) and its military counterpart, the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) [6,14,15]. In Poland, contested memories of the Holocaust have sparked both internal disputes and international backlash. These cases highlight the uncertain dynamics between municipal and national efforts to shape collective memory [5,16,17,18]. The aforementioned cases of Ukraine and Poland are related to the contemporary political situation and, in the case of Poland, to the pronounced societal polarization.

In the Lithuanian context, academic attention has primarily focused on the processes and circumstances of monument dismantling [19,20,21]. At the same time, it is acknowledged that various practices of collective memory, including the erection of new monuments related to the Soviet and Nazi occupations, have also sparked criticism and public debate [22,23]. As Dovilė Budrytė noted, “although arguably the story about the Holocaust still has not been fully adopted by Lithuania, its impact on the state and society is huge, and it has intersected multiple times with the story about the Soviet crimes” [24]. Consequently, contemporary memory practices often involve debates over the commemoration of controversial historical figures and sometimes competing narratives of the Nazi and Soviet occupations.

In other words, while dominant research on de-Sovietization in the public sphere tends to focus on the removal of monuments, de-Sovietization cannot be fully understood without examining how the meanings of removed monuments are replaced through newly erected ones, or how earlier meanings are incorporated into the emerging narrative about the state. This reveals the dual nature of the de-Sovietization process, encompassing both negative and positive dimensions. The demolition of Soviet-era symbols reflects the negative aspect of de-Sovietization. However, engaging with the past means not only distancing from specific historical episodes and figures but also actively shaping a collective memory that aligns with the values of the renewed independent state. In this context, newly built or restored monuments established after the regime change contribute to shaping a post-Soviet national narrative and can be seen as the positive aspect of de-Sovietization [25].

In retrospect, the replacement of monuments from the previous political regime signaled “the search for a new symbolic language that may ensure meaningful political as well as social communication” [26]. Thus, the transformation of monuments following a regime change is related not only to a shift in meanings but also to a change in plastic and symbolic expression which alters Soviet monumentalism.

This article employs Jacques Rancière’s theoretical framework of artistic regimes to explore the duality of de-Sovietization. It examines how the transition of regimes following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990 influenced the visual (plastic) aspects of newly constructed or reconstructed monuments. The main task of this article is to reveal the visual (plastic) characteristics of positive de-Sovietization by distinguishing its distinct visual features and principles. To address the main research question, this study focuses on the case of Lithuania and applies an interpretive research design grounded in qualitative content analysis of expert interviews with sculptors, architects, and artists involved in monument making since 1990.

Since the restoration of independence and liberation from the Soviet Union in 1990, more than 400 [27] monuments have been erected in Lithuania’s public space over the past three decades, presenting a new political identity of the country. Even more interesting is that the emergence of new monuments was accompanied by public debate and disagreement. The visual (plastic) expression of these newly created monuments in Lithuania has faced considerable criticism. A similar visual expression seen in the monuments that replaced the Soviet-era ones, dominated by an exclusively realistic aesthetics, is also evident in academic analyses [28,29,30,31]. This is also confirmed by practical examples. For instance, the naturalistic monuments by Romas Kvintas—dedicated to Chaim Frenkel, Roman Gary, Cemachus Shabad, and others—did not provoke discussions and disagreements. In contrast, monuments that go beyond realistic expression, such as Regimantas Midvikis’ Exploded Bunker or Andrius Labašauskas’ Freedom Hill project, became an object of conflict. This article, therefore, identifies the visual (plastic) aspects of positive de-Sovietization and explains how the visual language of new monuments relates to the stylistic expressions of Soviet-era monuments.

2. Rancière’s Theoretical Framework and the Duality of De-Sovietization

According to Jacques Rancière, socially constructed limits of what can be seen, said, and done in a particular time and space can be defined by the term distribution of the sensible. This concept reveals what is shared and characteristic of certain communities within a given historical and special context. Politics and art play a particularly significant role in this space—especially through various forms of artistic expression, including monuments. “Politics and art, like forms of knowledge, construct ‘fictions’, that is to say material rearrangements of signs and images, relationships between what is seen and what is said, between what is done and what can be done” [32].

In Rancière’s framework, monuments—like art in general—play a key role in the distribution of the sensible, which refers to what is visible, audible, and thinkable within a society. Monuments participate in this distribution by making certain figures, histories, and ideologies visible, while leaving others hidden or suppressed.

Building on the premise of the distribution of the sensible and aiming to explore how different societies organize and understand the relationship between art, politics, and perception, Rancière developed the concept of regimes of art or artistic regimes. The central idea of his theory is that art is not just a matter of aesthetic judgment but is deeply tied to the social and political order.

In Rancière’s view, art possesses the power to shape how we perceive the world. Different historical periods, including different political regimes, have developed different ‘regimes’ or systems for organizing perception. As Rancière explains, “aesthetics refers to a specific regime for identifying and reflecting on the arts: a mode of articulation between ways of doing and making, their corresponding forms of visibility, and possible ways of thinking about their relationship” [32]. “There is no ‘art’ without a specific identification regime that delimits it, makes it visible and makes it intelligible as such” [33]. Therefore, it can be assumed that different political regimes in different historical periods can be associated with different forms of plastic expression, conveying political meanings.

Rancière identifies three major regimes of art. The first one is the ethical regime, where “art is not identified as such but is subsumed under the question of images <…> it is a matter of knowing in what way images’ mode of being affects the ethos” [32]. According to this regime, which prevails in classical antiquity, the purpose of art is to reflect or promote virtue. Art is often embedded in the moral and religious frameworks of the community, with an emphasis on its role in shaping virtuous citizens.

The second one is the representative (or poetic) regime, in which the concept of mimesis, or representation, organizes the practices of making, perceiving, and judging art. <…> It is a “regime of visibility regarding the arts” [32]. Emerging in the modern era, around the 18th century, this regime plays a hierarchical role in society—for example, legitimizing political power or representing certain social classes. The third one is the aesthetic regime, which is “based on distinguishing a sensible mode of being specific to artistic production <…> is the regime that strictly identifies art in the singular and frees it from any specific rule, from any hierarchy of the arts, subject matter, and genres” [32]. This is the regime that emerged in the 19th century, particularly with the rise of modern art. Within the framework of this regime, art becomes an autonomous field of knowledge production, in which art has the ability to question and challenge the status quo.

“Rancière’s concept fundamentally disrupts the established art periodization in the history of Western culture and art of the 19th and 20th centuries and offers an alternative to many attempts to theoretically reflect on the 20th century art” [34]. The crossing of periodization boundaries and the distribution of the sensible concepts, allowing us to connect visuality and aesthetics with the formation of specific social and political knowledge, can help understand the relationship between art and politics across different historical and political periods.

“The aesthetic forms and narrative means of art allow for the production of a new kind of memory culture, as well as for a new kind of understanding of how we are to conceive of what is to count as memory culture, in order to address complex issues of their uses today” [35]. In this case, Rancière’s concept of regimes of art can be applicable to the understanding of the duality of de-Sovietization in public spaces through monuments. The removal of Soviet-era monuments and their replacement with new ones or their incorporation into a new narrative marks the confrontation between the representative regime and the aesthetic regime. In other words, it shows that the negative aspect of de-Sovietization, i.e., the removal of old regime monuments from public spaces, is not the only and finite process. The visual artifacts of the old regime and their characteristic expression do not leave a void; rather, they are replaced by new monuments that, through their visual and formal (plastic) qualities, construct a narrative of the new political order.

Following World War II, the Soviet expansion in Central and Eastern Europe was accompanied by the goal of establishing a pro-Soviet regime in the countries incorporated into the Soviet Union. In the context of Sovietization, “monuments became a key part of Soviet strategy on the ideological front” [36]. As early as the immediate postwar years, many of these countries saw the implementation of the so-called ‘monumental propaganda plan’ [37], that remained in effect until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Without exception, all works of monumental propaganda were required to adhere strictly to the principles of Socialist Realism. The term social realism was first introduced in 1932 and was legitimized as the official artistic doctrine of the Soviet Union in 1934. One of the fundamental visual rules of social realism was as follows: “there was no clear distinction between the iconic sign and its referent” [38]. Moreover, “the iconic sign became a simulacrum of reality” [38]. This reflects a mimetic relationship between art and what it represents, aligning with Rancière’s concept of the representative regime of art.

According to the representative regime of art, a work of art is “a system of rules based on which reality is structured” [39]. In the case of Socialist Realism, “art was a reflection of reality” [38]. It was created by regulating the techniques and content of representation [38], thus very clearly defining the rules that must be followed in art when representing reality. During Sovietization, art was regarded as a tool for representing an official reality, adhering to the norms of Socialist Realism1, which emphasized clear and direct depictions of reality. Although the Soviet period cannot be viewed as uniform in terms of established artistic traditions, some space for flexibility emerged after Stalin’s death, and by the 1980s, artistic activities increasingly explored stylistic diversity that went beyond the strict rules of Socialist Realism. The arts were subordinated to the state’s ideological agenda and were expected to represent Soviet ideals such as progress, strength, and unity—often through idealized portrayals of workers, soldiers, and scenes from everyday Soviet life. Art functioned as a means of reaffirming and legitimizing the Soviet system.

The perestroika reform that began in the Soviet Union in 1985 gradually undermined existing artistic constraints while simultaneously liberating aesthetic forms and practices. It was precisely during this period (the 1980s) that Socialist Realism began to lose its official status and influence. In many former Soviet states, particularly in Central and Eastern Europe, de-Sovietization marked a period of political and cultural transition following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the late 20th century. As these post-Soviet nations regained their independence, they sought to break away from the oppressive legacies of Soviet rule and redefine their political, social, and cultural identities. In public spaces, this shift was reflected in the transformation of monuments, free from previous constraints on aesthetics and content.

This transition to a post-Soviet world can be understood as a shift toward the aesthetic regime of art. In the immediate aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse, many artists sought to explore new ways of expressing themselves outside the rigid constraints of Socialist Realism, experimenting with abstract, conceptual, and non-representational art. According to Rancière, “the aesthetic regime of arts, it can be said, is the true name for what is designated by the incoherent label ‘modernity’” [32]. Incoherent modernity is related to the incoherence of modern art, which, during the Soviet era, was banned for its autonomy from traditional structures of representation, morality, and social function, particularly in its embrace of abstract forms characteristic of modernism.

Moreover, the period following the collapse of the Soviet Union can be seen as a democratization of art, where art no longer served to represent the state’s ideological purity but became more open to different, sometimes conflicting, visions of society, identity, and history. Here, “the aesthetic regime of the arts stands in contrast with the representative regime” [32], once again underscoring the duality inherent in de-Sovietization. In the newly independent Central and Eastern European states, the rejection of ideological purity in public spaces after the Soviet Union’s collapse was most visibly expressed through the dismantling of Soviet monuments. It was an act symbolizing the liquidation of the representative regime of art, and, by nature, the negative aspect of de-Sovietization. Yet, this marked only the beginning, not the end, of the de-Sovietization process.

The removal of aesthetic symbols from the old regime was accompanied by a positive dimension of de-Sovietization, i.e., the construction of new monuments. These monuments were no longer constrained by the rigid formal and ideological requirements of Socialist Realism, academicism, or state-imposed realism. Instead, they showed new visuality (plasticity) and content that changed the Soviet one.

In Rancière’s “concept of aesthetics, the idea is rejected that fundamentally autonomous modern art could be political only when artists directly responded to a clearly defined political field” [34]. In this light, artists, such as sculptors and architects in the former Soviet states after independence, need not explicitly engage in political activity or present overt political agendas through their monuments. What matters is that their artistic production emerges within a specific political context, thereby influencing and operating within the political field. Aesthetic knowledge holds its own truth and significance [40], as Rancière emphasizes that in the aesthetic regime, “politicality is manifested through the very logic of the creation of artworks” [40].

Thus, the transformation of monuments following regime change reflects not only a shift in meaning, signaling the emergence of a new, independent state distinct from the Soviet Union, but also a change in visual (plastic) and symbolic expression, moving away from Soviet monumentalism and liberating the plastic form from the constraints of Socialist Realism. The negative aspect of de-Sovietization marks a separation from the previous regime’s content of art, while the positive aspect of de-Sovietization reveals what new content meanings and visual (plastic) aspects replace the aesthetic production of the old.

3. A Methodological Approach to Visual Meaning-Making

This research formulates an interpretive research design aimed at identifying the visual (plastic) features of positive de-Sovietization and the meanings they communicate. Methodologically, the primary focus is on the processes of meaning-making, specifically, how visual (plastic) elements of monuments are assigned meanings associated with the emerging post-Soviet state after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

“In interpretive research, meaning-making is key to the scientific endeavor: its very purpose is to understand how specific human beings in particular times and localities make sense of their worlds” [41]. Focusing on the specificity of the post-Soviet space and the local Lithuanian aspect, the central concern of the research is how certain visual (plastic) elements are connected to meanings that represent the new political regime and define the state’s identity, as well as its emerging social and political state. Based on the understanding that “knowledge is situated and contextual (or local)” [41], the research employs expert interviews as its primary method supplemented, when appropriate, by the analysis of monuments constructed after 19902 to further reveal context-specific meanings.

Expert interviews serve as the primary research method, grounded in the assumption that experiences, knowledge, and positions are conveyed through language. It is through the act of speech that articulated reflections emerge, helping to reveal how certain meanings are constructed [42]. In this case, the focus is on meanings that link visuality with definitions of the state’s political condition and/or identity. The aim of the expert interviews is not simply to ask questions and receive answers, nor to test pre-formulated hypotheses. Rather, in this context, the primary goal is to understand social phenomena and the meanings through which they are interpreted, including certain dominant intersubjective meanings that inform decisions about monument visuality and, through these, contribute to the construction of a state’s self-perception.

In interpretive research, the expert interview method is valued for its depth, complexity, and richness of data [43]—all of which are essential for analyzing both the process and content of meaning-making. Following Alexander Bogner, Beate Littig, and Wolfgang Menz, individuals with expert status are defined as those who understand how specific knowledge is formed and actively participate in its production [44]. In this analytical context, the experts are identified as the artists, sculptors, architects and creators who designed monuments in Lithuania after the collapse of the Soviet Union. According to Giedrė Jankevičiūtė, who has examined the work of artists in the context of regime change, “the artist must comprehend political transformations and the changed reality of social and cultural life, and internalize the themes, imagery, and modes of expression imposed by the commissioner” [45]. Therefore, the artists who created monuments in Lithuania after the collapse of the Soviet Union—those who won competitions and erected monuments in public spaces—become key informants. They possess the most in-depth knowledge of visual expression decisions that respond to the demands of the new political, social, economic, cultural, and different kinds of reality.

At the stage of selecting expert interview participants, the process does not rely on randomness or the principle of maximum diversity. Rather, it is grounded in the understanding that what qualifies an individual as an expert is determined by the specific needs of the research. This approach follows the logic proposed by Lee Ann Fujii in her work on interview methods in social science, which emphasizes that meaning-centered research demands a purposeful and reflective respondent selection based on criteria aligned with the research logic and the central research question [43]. The number of experts involved in this research is limited, as public monument design competitions at the national or municipal level are typically won by a recurring group of sculptors as well as architects, some of whom are now deceased. In such cases, previously conducted and published interviews, articles, and publicly available statements by deceased sculptors and architects are used. The list of sculptors who participated in the expert interviews is included in Appendix A.

While working with the interview material, two main steps distinguished by Steiner Kvale [46] are followed: transcribing the interviews and analyzing the transcribed data. The transcribed data is processed using qualitative content analysis. “Content analysis is a method of analyzing visual images that was originally developed to interpret written and spoken texts” [47]. In this case, the method is applied to work with textual material collected from expert interviews with artists about visual images, i.e., monuments. The content analysis aims to identify recurring patterns between visual (plastic) elements and the content units associated with them. When necessary, additional academic sources on visual analysis or contextual information about the monuments are consulted. This process results in the development of a set of categories used for coding the images (codes). To ensure the replicability of the codes, they are presented in the analysis section (see Chapter Positive De-Sovietization and the Aesthetic Turn). Finally, by examining the codes and the relationships between them, the aim is to identify the meanings of Lithuanian monuments built after 1990—the meanings that connect visuality with definitions of the political condition and/or identity of the state. In the words of Rancière, this involves determining the characteristics of the current aesthetic state of monuments and their visual vocabulary.

4. The End of the Representative Regime of Art: The Rejection of Socialist Realism

The negative aspect of de-Sovietization in Lithuania—following the restoration of independence in 1990, or even a couple of years earlier with the rise of the Sąjūdis movement around 1988—was associated with the dismantling of monuments erected during the Soviet era, or, using Rancière’s framework, the liquidation of the representative regime of art. This can be linked to a shift in the dominant distribution of the sensible, through political knowledge about state-building as expressed in artistic practices and their visual (plastic) aspects by rejecting Soviet narrative (thematic) and visual (plastic) elements.

Thematically, Socialist Realism was based on the categories such as ideology, class struggle, party-mindedness, and loyalty to the party. At the same time, categories like creative imagination, fantasy, and fiction were rejected [48]. Regardless of the country in which Socialist Realist monuments were erected, their political message was the same: to educate people about the Communist Party [49], to portray the Soviet regime as the best possible system, and to promote its vision of a ‘bright future’.

Within the aesthetic paradigm of Socialist Realism, art was viewed as “an active social agent, which had the potential to shape reality directly” [38]. As a result, the creation of political knowledge—both in terms of visual (plastic) expression and narrative (thematic/content) perspective—was governed by strict rules. The visual vocabulary was largely shaped by the principles of Socialist Realism, which required sculptures to adhere to naturalistic forms while restraining personal creativity and stylistic individuality [50]. Sharply defined visual codes and a controlled aesthetic order were characteristic of this approach [51,52].

When it comes to the themes developed through monuments—or, in other words, the narrative level through which the distribution of the sensible operated within the aesthetics of Socialist Realism—it is important to understand that foremost among these elements was the strict subordination of both art and the artist to state control in the name of ideological purity [53]. Creative and thematic freedom was minimal. The themes commonly developed in Lithuania included: “the long-standing history of our Homeland, the struggle of the popular masses for its freedom and independence, the revolutionary movement, the establishment and development of the Soviet socialist state”; “the events of the Great October Socialist Revolution and the Socialist Revolution in Lithuania, the Civil War and the Great Patriotic War, the labor achievements of the working class, collective farm peasants, and the intelligentsia, the fraternal friendship of the peoples of our country, and the struggle of the Soviet people for the creation of socialism and communism” [54]. Monumental aesthetics functioned as both a transmitter and enforcer of these themes within society.

During Soviet times, both the scale and quantity of monuments were crucial, serving as a representation of the regime’s strength [38]. After the restoration of independence in 1990, public spaces in Lithuania were actively cleaned of Socialist Realist monuments: statues dedicated to political ideology and Soviet heroes were systematically dismantled. This marks a clear rejection of the representative regime of art, as the number of visual symbols testifying to the former regime’s stability was actively reduced. Furthermore, the dismantling of the representative regime of art had already begun even before the restoration of independence.

As shown in Figure 1, between 1988 and 1990, public spaces in Lithuania saw the active restoration of monuments originally erected during the interwar period and later dismantled during the Soviet era. These monuments were dedicated to modern Lithuania, established in 1918, and commemorated various anniversaries of that occasion, i.e., the 10th and 20th anniversaries, as well as the interwar struggles for independence from 1918 to 1920. This process was particularly intense in 1989, when more than 50 monuments were rebuilt in various Lithuanian cities and towns. Although the sculptural expression of these restored monuments was realistic, their visual design mostly followed the forms of classical monuments (pyramids, obelisks). However, their symbolism, integration of visual elements, and other features did not align with the Soviet canon. These monuments were marked by strong and explicit national symbolism of the Lithuanian state—the symbols that had been established during the interwar period and prohibited under the Soviet regime. This meant that, both visually and thematically, the vocabulary of Socialist Realism was being diluted, thereby unsettling the illusion of regime stability and thematic uniformity that had been constructed in public space through monuments during the Soviet era.

Figure 1.

Independence Monument (also known as the Freedom Monument) in Siesikai, 1928, restored in 1989. Photo: by the author.

Similarly, after 1990, the modes of producing what Rancière calls the distribution of the sensible began to change significantly. In the context of authoritarian regimes, abstract art and its various movements signified chaos, resistance and criticism toward authoritarianism. The individualistic nature of such works stood in opposition to the collectivist ideals promoted by authoritarian movements and Socialist Realism [55], and was therefore actively criticized.

Based on the testimonies of sculptors and architects, the transition from the Soviet era marked a shift from state commissions assigned to specific authors to public competitions. In these competitions, an individualistic approach to such work prevailed, characterized by personal interpretations of the theme and the search for unique forms of plastic expression [56,57] unrestricted by either strictly realist or exclusively abstract styles. Moreover, what during the Soviet period in Lithuania was referred to as practices of semi-nonconformism—where artists officially and publicly produced works conforming to Soviet censorship, while privately in their studios creating without self-censorship works that in terms of theme and visuality did not comply with Soviet canons—began to be publicly exhibited and recognized.

5. Positive De-Sovietization and the Aesthetic Turn

The way we perceive art is shaped by a specific regime of identification that determines not only aesthetic forms but also the underlying politics and structures of community [32]. It becomes clear that the rejection of the Soviet order and aesthetics, which began even before 1990 and is often framed through the term de-Sovietization, is not a finite process. Changes in the distribution of the sensible are not sufficient to abolish the previous art regime—its partial or complete dismantling does not result in vacuum. As the sculptor Antanas Bagdonas emphasized in his memoirs, following the restoration of independence, “it was necessary to build something in Tauragė as soon as possible to remind people of the times of independent Lithuania, to bring back the spiritual values we once cultivated.” Therefore, priority was given to the restoration of monuments that had been demolished during the Soviet era [58].

A new form of political knowledge was constructed that required a new visual vocabulary. This is clearly evident in the way new monuments began to be erected following the demolition of the Soviet ones. Such developments confirm the dual nature of de-Sovietization—that the removal of Soviet monuments was accompanied by a constructive process, i.e., the building of new monuments. In terms of Rancière’s framework, this points to the establishment of a new, distinct regime of art.

Several overlapping features (methodologically, this could be referred to as disengaging codes) of a new visual vocabulary can be identified: (1) a transition from the expression of Socialist Realism and anti-modernism to symbolism, conceptualism, and the search of other forms of artistic expression; (2) the synthesis of state, national, and religious symbols; and (3) visual representations of the struggle for Lithuania’s freedom and independence.

5.1. A Transition from the Expression of Socialist Realism to Symbolism, Conceptualism, and the Search of Other Forms of Artistic Expression

Has Lithuania succeeded in freeing itself from the canons of Socialist Realism in the monumental art of public spaces after its liberation from the Soviet Union? This question is frequently raised in public discourse. Newly erected monuments commemorating events, individuals, or groups that contribute to the narrative of a free and independent Lithuania are often criticized for their realistic nature, i.e., a visual language deeply embedded in public commemorative practices since the Soviet era. A similar discussion is also observed in academic cycles: “Quite a few Lithuanian art critics are apt to view the proliferation of public monuments as a kind of continuity of the Soviet tradition” [59]. This critique is well summarized by Elona Lubytė, who has analyzed art in public spaces during the post-Soviet period:

“After the removal of symbols of the former political regime, efforts quickly turned to restoring monuments that had been demolished during the Soviet era and to creating new ones in their place. However, old artistic and organizational methods were employed in their realization.” [60]

The discourse among sculptors and architects responds to this discussion ambivalently. According to Rancière’s explanation, a change in the regimes of art should be associated with the establishment of a different mode of aesthetic expression. Nevertheless, in Lithuanian memorial monumental art, where realist expressions persist or even dominate in some cases, there are no significant fundamental changes in visual (plastic) expression, according to such sculptors as Mindaugas Šnipas. He notes that “<…> most still create figurative works out of inertia, as this approach is deeply ingrained—an entrenched prosthesis embedded in the bones and brain—so that alternative methods are scarcely even considered” [56]. Meanwhile, architect Gintaras Čaikauskas acknowledges that although examples of emerging figurative monuments can still be seen in public spaces, a shift has occurred: “Not only has the ideological foundation changed, but artists’ means of expression are also evolving. Today, everything is becoming more conceptually grounded than before, when the approach was primarily declarative in form” [57]. Sculptor Arūnas Sakalauskas, reflecting on contemporary monumental art, highlights its potential for diversity: “One can speak through symbols as well as through abstract, conceptual means. But sometimes a portrait or figurative work is needed. And creating an artistic harmony between abstraction and figurative elements is very challenging” [61].

Considering both the discourse of artists and the monuments that have appeared in Lithuania’s public spaces since 1990, it is not possible to assert unequivocally that the visual vocabulary has strictly abandoned realist expression. Thus, the assumption that Socialist Realism, dominant during the Soviet era and serving as the foundation of the representative regime of art, was frequently in opposition to abstract art [62], and that the aesthetic regime of art must therefore be exclusively associated with abstraction, is not fully supported in practice. Nevertheless, certain modes of visual (plastic) expression suggest that the visual vocabulary of the post-Soviet period is characterized by hybridity. Even in cases of realistic expression, it is important to emphasize that its use in the post-Soviet era reflects the sculptors’ own choices rather than adherence to imposed canons.

For example, the theme that dominated during the Soviet period—conscious Soviet heroes live at the intersection of the present and future [48]—was most often developed through figurative monuments. The motif of a bright future promised by the Soviet regime was typically conveyed in the visual (plastic) elements of monumental propaganda through the gaze of the represented hero, usually a human figure elevated on a pedestal, looking into the distance: “the gaze toward the horizon is a look metaphorically to the future and high ideals” [49].

Following the restoration of independence, figuration was no longer the sole means of representing heroes (Figure 2). The commemoration of partisan war heroes, which challenges the glorification of the Great Patriotic War promoted by the Soviet narrative by revealing the Soviet Union not as a liberator but as an occupier of Lithuania, marks a turn toward non-figurative forms of expression. Both figurative and symbolist visual solutions are employed in commemorating the leaders of the partisan war (Figure 3). The most representative examples are linked to the monuments created as part of the national remembrance program, which honors all partisan military districts and key heroes of the partisan struggle in Lithuania. These include monuments to General Jonas Žemaitis-Vytautas in Palanga; Žemaitis-Vytautas and Petras Bartkus-Žadgaila in Raseiniai; Adolfas Ramanauskas-Vanagas in Lazdijai, Leonardas Vilhelmas Grigonis-Užpalis in the village of Sėlynė; and Vytautas Gužas-Kardas in Kazliškis.

Figure 2.

A typical example of commemorating Soviet heroes—the monument to the Soviet partisan Marytė Melninkaitė in Zarasai, 1955, now dismantled. Photo: Wikipedia.org.

Figure 3.

Models of anti-Soviet partisan monuments created by Jonas Jagėla. Photo: by the author.

As recalled by Rūta Trimonienė, the wife of the monument’s author Jonas Jagėla, the creative process behind his works reflects a transition in visual expression from realism to symbolism [63]. “If we look at the monument to Jonas Žemaitis (in Palanga), its symbolism lies in the tent. His idea was that tent, the underground bunker, the hideout where all (the partisans) would take refuge—and, of course, the forest. According to the concept, there was only supposed to be that tent, the bunker, with the Vytis Cross above it and a small spruce tree. That is the forest—the forest is the home of the partisans” [63], Trimonienė explained, illustrating the shift toward symbolic representation.

The activation of symbolism is also prominent in the work of Daliutė Ona Matulaitė, whose aesthetic is characterized by the communication of symbolic meaning and movement. Commenting on one of her most notable monuments dedicated to the writer Ieva Simonaitytė in Priekulė, the sculptor stated: “In sculpture, there is a different kind of language of meaning: it is as if the figure were part of a tree, like a traditional wooden grave maker, like a loaf of bread… From a strong dynamic of volumes at the base, it transitions into complete stillness at the top” [64].

It can be observed that, based on the discourse of the artists themselves, symbolism in the search for visual (plastic) expression is often combined with a realist style. For example, sculptor Regimantas Midvikis, commenting on his monument to the Vileišis brothers, which employs a realist mode of representation to depict interwar Lithuanian cultural figures seated around a table, emphasized a symbolic element: “The table is a symbol uniting all three brothers as members of the same family. At the same time, the table connects them with the nation, as they address important questions of statehood, culture, and society” [65].

A synthesis of different modes of expression is also characteristic of the work of Vytautas Kašuba, where we see a “concrete interaction between figurative content and abstract meaning, one that decides the direction of its artistic interpretation of history” [66]. Klaudijus Pūdymas likewise highlights the pursuit of individualized solutions, even when working with a figurative framework. “My style is not hyperrealism. What matters to me is the dynamism of form. I might call it emotional realism so that the subject remains recognizable. But it depends on the task I set for myself. I choose what to emphasize. For me, dynamism is key” [67], the sculptor explained.

Another illustrative example is the visual representation of mourning. In the Soviet narrative, the Second World War and the postwar period were closely associated with pride in the present, associated with the great victory in the Great War [48]. Following the restoration of Lithuanian independence, however, the visual vocabulary used to depict this same historical period in monumental art shifted markedly—from expressions of pride to imagery grounded in mourning.

In commemorating the deportations carried out during the Second World War and the postwar years, the victims who perished in exile, and the partisans who fought for Lithuania’s freedom and independence from the Soviet Union, monuments incorporating the visual language of altars, often built from fieldstone, have been widely erected.

One of the primary functions of the altar type is to serve as a site for remembrance and tribute to deceased ancestors and family members. In essence, they serve as memorials to the dead and to the past [68]. In terms of emotional resonance, this mode of expression engages with the relationship between past and present through the lenses of sorrow and contemplation [69]. The visual approach is deeply symbolic, focusing not on pride in the memory of the Second World War and its associated events but rather on the articulation of pain and mourning. It is a profoundly visual (plastic) strategy intended to enable proper mourning and to express respect for the deceased, i.e., those whose deaths or suffering could not be acknowledged at the time they occurred.

The motif of respectful mourning, expressed through themes of sorrow and grief, is further evidenced in the visual (plastic) language of early post-independence memorial practices. During the five years following the restoration of Lithuanian independence, numerous monuments dedicated to participants of the partisan war began to appear in public spaces. Their form often resembled gravestones typically found in cemeteries, underscoring a direct connection between visual (plastic) expression and mourning, as well as the commemoration of death. These monuments were minimalist in design, typically consisting of stone, granite or concrete bases. Inscribed on them were the names, surnames, and, when known, birth and death dates of fallen partisans who, at the time of their death, could not be properly buried or commemorated.

Finally, even artists who employed the human figure as their primary mode of visual (plastic) expression have noted shifts in the recognition of their work following regime change. One of the most representative examples is Romualdas Kvintas, who, after the restoration of Lithuanian independence, created monuments dedicated to prominent cultural and historical figures such as singer Vytautas Kernagis, writer Romain Gary, singer Danielius Dolskis, physician Zemach Shabad, writer and singer Leonard Cohen, as well as Hermann Kallenbach and Mahatma Gandhi. Although Kvintas’s sculptures are characterized by highly refined realist expression, his work received limited acknowledgment during the Soviet period. As his wife notes, “There were years when he did not manage to sell a single piece” [70]. A significant turning point in the recognition of Kvintas’s work occurred only in the early years of restored independence.

Therefore, even while acknowledging that visual (plastic) expression in the post-Soviet period is associated with the emergence of the aesthetic regime of art, it still retains certain similarities with the realist tradition developed under the representative regime of art during the Soviet era. Nonetheless, one can observe a growing diversity in the visual vocabulary. As art historian Jankevičiūtė notes, the use or avoidance of specific forms does not, in itself, indicate an oppositional stance toward the regime [71]. Whereas works of Socialist Realism were required to be concrete in all dimensions—political, ideological, historical, social, and visual—the new visual (plastic) language is more liberal. One encounters figurative–realist, symbolist, abstract, and minimalist monumental practices, as well as monuments that combine several representational modes. As noted, “In the aesthetic regime, the criterion of art is no longer technical perfection, as in the representative regime”. It is precisely the abandonment of established technical perfection and the embrace of heterogeneity that, as Rodolfo Wenger [33] has observed, marks one of the defining features of the aesthetic regime of art.

Examining the visual vocabulary that emerged after the restoration of independence, it becomes evident that it began to produce a different kind of (political) knowledge. In contrast to the Soviet era, when strict rules dictated what and how subjects were to be represented, the shift in regime introduced a fundamentally different relationship between visual (plastic) expression and the themes or narratives being represented and constructed.

Within the discourse of sculptors and architects, there is a broad consensus that the current aesthetic regime of art is characterized by the primacy of the idea over visual (plastic) form. As expressed by practitioners themselves: “In the case of monumental art, at least, plastic expression is merely a means. Without the backbone provided by the idea, it would be fragmented” [56]; and “when making decisions, we consider not only the theme itself but also the context—where the theme will be situated” [57]. As Sakalauskas describes his creative process: “First, I delve into documentary and historical material. As I immerse myself in it, the creative process begins. Sometimes the idea for a sculptural expression emerges quickly. In any case, it is important to me, when creating a sculptural form, to thoroughly understand the personality, historical event, or theme—in other words, to grasp the inner content of the form. After all, in sculpture, the form must be tense from within. I try, in one way or another, to creatively evoke the vision of the idea’s visualization, its manifestation in consciousness” [61].

Thus, the prescriptive framework for how a particular theme must be visualized is no longer in place. The choice of visual vocabulary allows for diverse, individualized solutions shaped by the underlying idea—the theme, the meaning the artist seeks to convey. In this way, the very principle of creation implies a departure from the implementation logics of the previous artistic regime.

5.2. The Synthesis of State, National and Religious Symbols

“Soviet monuments were used for the semiotization of public urban space at a time when the church was denied its key role in the spacio-temporal structuring of social life” [38]. During the Soviet era, national and Catholic crosses, along with other forms of Catholic symbolism, were prohibited. In contrast, in the post-Soviet period, such religious and national symbols began to play a dominant role in monument design. Moreover, contemporary visual (plastic) expressions seek a distinctive harmony and internal coherence between state, national, and religious symbols. In this context, religious symbolism often transcends its Christian–Catholic boundaries and is linked to pre-Christian, pagan traditions. This search for synthesis is exemplified in the work of artist Jagėla:

“He used to say: ‘Look, this contains the entire code of Lithuania: serpents, paganism, crosses, the Vytis crosses. Everything is interconnected. The crosses, the Vytis crosses, the serpents—all of it is so organic, so inseparable. And we, Lithuanians, are children of nature, and for us, paganism truly holds deep significance. I believe that the earliest impulses for all these monuments dedicated to the struggles for freedom were those little serpents.” [63]

That the search for continuity and coherence in symbolic language is not accidental is further evidenced by analyses of monuments created by Midvikis: “The chance to immortalize pagan symbols in stone had a sacral meaning for this artist. On the other hand, Midvikis did not ignore Christian symbols” [72]. In this way, his monuments bring together Lithuanian identity, national symbols, and legends [72], merging them into a unified visual narrative.

A similar emphasis on personalized visual solutions is found in the recollections of architect Algimantas Nasvytis, who highlights the importance of reflecting Lithuania’s cultural specificity: “Sociology, customs, local characteristics, identity—these are all aspects that an architect must be able to understand, evaluate, integrate, and ultimately translate into a solution” [73]. This approach underscores a commitment to context-sensitive design rooted in national identity. National identity, combining elements of paganism and Christianity, is strongly associated with the depiction of crosses in Lithuanian monumental art. In the 19th and 20th centuries, roadside crosses and other types of sacred folk monuments were prohibited and destroyed by various occupying forces, as they represented public expressions of the Catholic faith and national identity [74].

Likewise, in the artistic practice of Konstantinas Bogdanas, there was a conscious effort to preserve the stylistic traits of the national school of sculpture, reinforcing the continuity of a distinct Lithuanian sculptural tradition even within evolving artistic paradigms [75].

This continuity and coherence are further evidenced by the deconstruction of visual (plastic) expression. Regardless of which historical events are commemorated in relation to Lithuanian freedom and independence—thus contributing to the post-Soviet narrative of the nation (including the partisan resistance, deportations, struggles for freedom, the interwar period of Lithuanian statehood, anniversaries of the 1918 founding of the Lithuanian state—its tenth, fifteenth, or twentieth anniversaries—the book smugglers (Lithuanian: knygnešiai), or the anniversaries of the re-establishment of independence in 1990)—monuments consistently feature the recurring motif of the cross. This may take the form of a minimalist, conventional cross symbol, or a stylized and ornamented cross, carved in stone or cast in metal, integrated into the monument’s overall composition.

Researchers of Lithuanian folk art agree that the decorative motifs of crosses in Lithuania can be categorized in two main groups: symbols derived from pre-Christian culture and Christian religious symbols [76]. Crosses associated with pre-Christian traditions are characterized by nature-inspired symbolism, including geometric patterns and ornaments (such as fir tree motifs, serrated lines, small crosses, lattice designs, circles, semicircles or arches, spirals, cords, and braids, as well as plant motifs (rosettes, flowers), animal motifs (serpent, bird), and cosmological symbols (sun, moon, stars)) [76]. In contrast, crosses adorned with Christian motifs feature symbols such as rays, halos, the Eye of Divine Providence, instruments of Christ’s Passion, the crown of thorns, angelic heads, liturgical chalices, and similar imagery [76].

The elements of paganism are strongly expressed in Lithuanian monumental crosses, particularly through the use of motifs such as solar discs, braids, and fir tree patterns (Figure 4). These visual (plastic) elements serve to symbolically link significant events and historical figures, commemorated through monuments, to the ancient, pagan origins of Lithuania. Within the framework of state-sponsored commemoration programs, monuments erected in Seirijai, the village of Minaičiai, and Svėdasai in honor of the partisan war exemplify this connection.

Figure 4.

An example of Christian and pagan symbolism: the 1000th Anniversary of the Name of Lithuania Monument in Reškutėnai. Photo: by the author.

In the work of sculptor Jagėla, the symbolism, most notably the serpent motif, evokes Lithuania’s pagan past and establishes a relationship between this heritage and the events of the 20th century. The serpent is one of the most significant symbols in the Lithuanian mythological universe. In Lithuanian folklore, it appears in both zoomorphic and anthropomorphic forms and is associated with divine or primordial knowledge, as well as with the symbolism of life and death. The serpent connects the visual lexicon not only to ancient, pre-Christian, i.e., pagan Lithuania, but also to the natural landscape, particularly to water and forests, where it was believed to dwell according to folk tradition [77].

Nature, and especially the forest, served as the principal setting for the partisan war, which was the most prominent form of anti-Soviet resistance. In this context, the cross functions as a symbolic bridge between pagan and Christian, specifically Catholic, iconography, representing Lithuania’s historical trajectory and its transition from a pre-Christian to a Christian state of being.

It is believed that mothers would place small crosses around the necks of their sons as they left for the forests to fight against the Soviet regime, entrusting their protection to God. Partisans who perished in the war were often buried in unmarked or improvised graves. After the restoration of Lithuanian independence, when efforts to locate and identify the remains began, these crosses became important tools for identifying the deceased [63].

Moreover, widely circulated accounts within society tell of deportees and political prisoners returning from Siberia who spoke of how prayer and faith helped them endure their suffering [63]. In this context, the relationship between the cross and Chirstian symbols takes on particular significance, especially considering the ideological conflict with the Soviet era, during which Christian, particularly Catholic, symbolism was prohibited.

Thus, the abundant and active use of Christian (Catholic) visual (plastic) symbols following the restoration of independence serves to underscore a conscious break with, and opposition to, the previous regime. At the same time, within Lithuanian symbolic culture, the cross also comes to embody the idea of resistance itself [76].

Although the cross is, first and foremost, undeniably a symbol of Christianity, “during the period of national revival in 1988–1989, Lithuanians, by erecting or placing crosses, expressed their desire to be independent from the Soviet Union” [78]. In this context, the cross had become a distinctive tool of resistance.

In the visual language of monuments, the cross is most often accompanied by national symbols: the Vytis, the double (Jagiellonian) cross, and the Columns of Gediminas. The Vytis, a knight in light armor bearing a shield, the double cross associated with Jogaila and the Jagiellonian dynasty, and the Columns of Gediminas have, since the Middle Ages, been among the most important emblems representing the Lithuanian state [79]. These symbols began to be used in the 14th century.

Through their incorporation into monuments, a visual (plastic) narrative is constructed that sends a clear message linking modern Lithuania to the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL), evoking a period in which the foundations of statehood were first established. The double cross and the Columns of Gediminaičiai gained renewed prominence in the early 20th century, particularly after the declaration of Lithuanian independence in 1918, when they were adopted as official state symbols [80,81].

Thus, in terms of meaning, the use of these symbols visually connects the state restored in 1990 with the modern Lithuanian republic that emerged in the early 20th century. This continuity emphasizes the unbroken thread of Lithuanian statehood, a history that was interrupted during the Soviet era, when both these symbols and their visual representation in public monuments were banned.

On the visual level, the complexity of symbols, i.e., pagan Lithuania, Christian Lithuania, and the state emblems that originated in the Middle Ages and are still actively used today, brings together different historical periods that do not conflict with one another but rather illustrate a transition from one era to the next. This layering emphasizes the longevity and continuity of the Lithuanian state, a continuity fundamentally incompatible with the Soviet occupation. The synthesis of national, religious, and state symbols reveals a distinctive Lithuanian identity, one that is constructed and communicated through monuments.

This interweaving of visual symbols is not an exception but rather a reaffirmation and continuation of a tradition. Even in monumental art, modern Lithuanian culture draws from two primary sources: the ethnic (folk heritage) and the historical (the legacy of the GDL) [82]. This principle is well illustrated in the monumental world of Kašuba, whose approach is based on the “archetype of symbolic, mythical, and artistic thought” and on the representation of two periods in the Baltic culture—the pagan and the Christian [66]. Another example is the monument to King Mindaugas created by sculptor Midvikis:

“The king holds in his hands the two royal regalia: the orb and scepter. The sculptor included pagan symbols on the scepter of Mindaugas, while he placed a Christian cross on the orb.” [72]

The figure of Mindaugas, the only crowned king of Lithuania, is closely associated with the Christianization of the country and its integration into the political map of medieval Europe. Historically and politically, this moment marked the early foundations from which the modern Lithuanian state would later emerge in the early 20th century, the foundations that were reaffirmed following the end of Soviet occupation. The visual (plastic) expression of such monuments reflects the interplay between different historical periods and their coexistence on a narrative (thematic) level.

5.3. Visual Representations of the Struggle for Lithuania’s Freedom and Independence

“This is most often connected to the struggles for freedom—arguably the most fundamental and enduring theme in Lithuania’s historical narrative. It appears to be a perpetual motif, one that holds a foundational, almost archetypal place in the nation’s collective memory. All other layers tend to emerge in addition to, and built upon, this core idea.” [57]

This central thematic focus in Lithuanian monumental art after 1990 was identified by architect Čaikauskas. The significance of commemorating the fight for freedom is also emphasized by sculptor Gediminas Piekuras, who highlights that memorializing these struggles holds deep personal and emotional meaning for him [83]. Similarly, sculptor Sakalauskas has stressed the importance of this theme when speaking about his monument The Warrior of Freedom, noting that the face of the statue “is modeled after Romas Kalanta, who fought for freedom” during Soviet times [84].

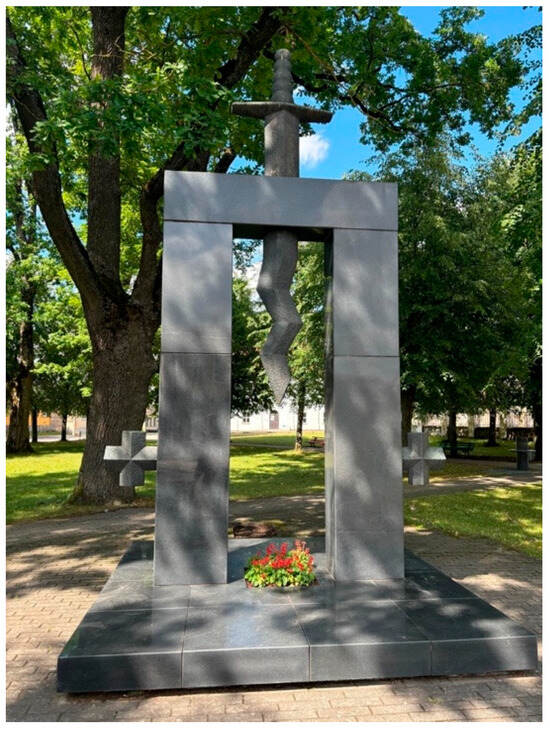

On the narrative (thematical) level, the visual (plastic) expression of the struggles for freedom and independence linked to the idea of statehood is often marked by the recurring motif of the sword in Lithuanian monuments. In the classical sense, the sword represents military power [85]. This aligns with the thematic significance of many monuments that incorporate sword symbolism to commemorate battles and armed resistance across various historical periods, beginning with the earliest stages of Lithuanian history. Examples include the monument to Duke Vykintas in Tverai, the monument to King Mindaugas in Druskininkai, the monument to Duke Kęstutis in Prienai, the monument to Duke Vytenis in Marijampolė, the monument to Duke Gediminas in Vilnius, and the monument commemorating the Battle of Pabaiskas. In these cases, the sword serves as a visual reference to the medieval era.

Sword symbolism is prominently employed in monuments commemorating the struggles for independence during the interwar period (1918–1920). This symbolism also reappears in monumental works dedicated to the partisan resistance associated with the anti-Soviet struggle.

As previously noted, in monumental art, the struggle for freedom is associated not only with military power but also with the idea of statehood, i.e., fight for the sovereign existence of the state. The diversity of historical periods represented, beginning with monuments that recall the Middle Ages, implies that this struggle is traced back to medieval times. This is further supported by visual choices, as the roots of modern sword symbolism can, in general sense, be traced to the Middle Ages [86]. The relationship between statehood and the visual symbol of the sword in Lithuanian monumental art is vividly illustrated by the monument to Grand Duke Gediminas in Vilnius, created by Kašuba. As noted in the monument’s analysis:

“Having chosen to present Gediminas as standing rather than riding the horse—the traditional depiction of military leaders—the sculptor presented Gediminas as a builder of the city and founder of the state. This thought is transmitted by entire bearing of the Grand Duke, the arm and the sword being held horizontally, as a symbol of protection rather than battle.” [66]

The position of the lowered, rather than raised, sword appears in monuments to Grand Duke Gediminas and, for instance, to Grand Dukes Vytautas and Kęstutis, as well as King Mindaugas. In this context, it is important to note that, in deconstructing the idea of statehood communicated through monuments, commemoration most actively employs those grand dukes who, in historiography, are associated with the notion of a sovereign medieval Lithuanian state. For example, unlike his uncle Kęstutis and cousin Vytautas—who are widely represented in Lithuanian art as symbols of sovereignty and resistance—Jogaila remains a more ambivalent figure. His role as the initiator of the Polish–Lithuanian union, often interpreted as a compromise of Lithuania’s autonomy, has made him less appealing to artists, particularly in the post-independence context.

Returning to the visual motif of the lowered sword, it also appears in memorials dedicated to the partisan war. Striking examples of this can be found in the Raseiniai Memorial to the Partisans, the Darbėnai monument to the Sword Company partisans, the Gelvonai monument to the partisans of the Great Fight District, the Troškūnai monument (Figure 5) to the Algimantas District partisans, etc.

Figure 5.

Monument to the Partisans in Troškūnai, 1996. Photo: by the author.

The visual vocabulary employed in monumental art reveals the intertextuality of the sword symbol: it signifies the struggle for freedom and statehood, conveying not so much military power as resistance against historical forces of evil. In Lithuanian historiography, “the insignia of the sword embodied several meanings: rule over the land, the defense of justice, the protection of the Church and the faithful, and elevation to knighthood. In general, whoever held the sword was obligated to defend truth within the state” [87].

This is further confirmed by Trimonienė’s recollections regarding Jagėla’s monuments to the partisans in Troškūnai and Gelvonai:

“When that cross appeared in Troškūnai, he also created the sword of Archangel Michael—not the one meant for combat, but the one that carries light. And in Gelvonai, the monument conveys a sense of peace, once again featuring a laid-down sword—the one that seems at rest, yet with the passage of time, if needed, it can be raised again. A lowered sword means it is resting but it can be lifted at any moment.” [63]

This idea has also been emphasized by sculptor Sakalauskas, who noted: “In the courtyard of Kaunas Castle, The Warrior of Freedom is not attacking; he is greeting his nation on the occasion of its regained freedom” [88].

The visual (plastic) representation of the sword thus implies both the act of fighting for freedom and the commemoration of its outcome—the existence of a free and independent state. In this context, visual references associated with the Soviet occupation and liberation from it became particularly significant.

In symbolism, the sword “received the status of a noble weapon, which demonstrates the personal courage and mastery of the owner in a fight” [86]. However, it is also acknowledged that the visualization of the sword plays a significant role not only in royal but also in religious iconography [89].

During the Soviet era, when Christian, particularly Catholic, practices and symbols were suppressed, the depiction of the sword in monuments commemorating the partisan war, i.e., the anti-Soviet resistance, reinforced a conscious detachment from the symbolic space of the Soviet Union. Furthermore, this choice of visual (plastic) expression can be interpreted as an allegory of the triumph over evil, a hostile force.

For example, the Troškūnai monument (Figure 5) dedicated to the partisans of the Algirdas District, according to the discourse of its creators, depicts the sword of Archangel Michael. In religious sculpture and visual art, Archangel Michael with a sword can be found in various locations across Lithuania. One notable example in monumental art is the monument to this religious figure in Musninkai (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Monument to Saint Archangel Michael in Musninkai. Photo: by the author.

Archangel Michael is regarded as the chef commander of God’s army, who fought against Satan [90]. In sacred art, his sword symbolizes the power to combat the forces of evil. Thus, metaphorically, through visual (plastic) expression, the anti-Soviet resistance is commemorated as a battle against evil (the occupier), a battle that ultimately ended in success—the restoration of a free and independent Lithuanian state.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

While much of the existing scholarship on de-Sovietization has centered on acts of destruction and removal—the symbolic gestures of iconoclasm—this study shifts attention to what comes after such erasures: the new visual and commemorative practices that fill the vacated spaces. By examining what replaces dismantled monuments, rather than solely what disappears, this article highlights the constructive and meaning-making dimension of de-Sovietization. The Lithuanian case shows that de-Sovietization is not only a project of removal but also one of creation—a process through which public space becomes a site of negotiation between memory, identity, and political transformation.

This focus on newly created monuments reveals what traditional analyses of monument demolition often overlook: the complex relationship between form, meaning, and political context. The monuments that have emerged in Lithuania since 1990 reflect not emptiness but continuity—a living landscape where history is rearticulated through new visual languages. These new artistic practices do not merely fill physical voids but also address symbolic ones, shaping how the state and society reinterpret their past and project their future. In the context of the former Soviet Union and its sphere of influence, such processes illuminate the trajectories of national identity formation and the ways in which cultural memory adapts to shifting ideological horizons.

Applying Rancière’s theoretical approach of the regimes of art, this article sought to reveal the visual (plastic) aspects of positive de-Sovietization by identifying distinct visual features and their underlying principles. The application of Rancière’s concept confirmed the dualistic nature of de-Sovietization in public spaces through monuments. As regimes change, so too does the distribution of the sensible and its visual expression. The removal of Soviet monuments and their replacement with new ones—or their incorporation into renewed narratives—marks the encounter between the representative and the aesthetic regimes. In this light, the negative dimension of de-Sovietization (removal) is only the beginning of a broader transformation that culminates in the emergence of a new visual vocabulary.

The analysis of monuments erected in Lithuania after 1990, based on expert interviews with sculptors and architects, revealed that public spaces were not left empty after the removal of Soviet monuments. Instead, they were redefined through new constructions and reconstructions that articulated fresh thematic narratives and distinct aesthetic expressions. When examined through Rancière’s lens, positive de-Sovietization reshapes public space not merely through physical renewal but through the creation of new visual vocabularies—forms and symbols that develop alternative cultural narratives and actively redefine collective memory.

The findings demonstrate that although the change in political regime might suggest a complete shift in visual expression, reality is more nuanced. Realistic and figurative forms continued to play a significant role in newly erected monuments. Yet, the characteristics of the aesthetic regime became increasingly evident: the heteronomy of artistic expression, a departure from the rigid canons of Socialist Realism, and the emergence of individualized approaches grounded in symbolism, abstraction, and conceptualism. The democratization of the monument-making process—from centralized state commissions to public competitions—reflected broader transformations in the relationship between art, politics, and society.

Ultimately, three key tendencies define the visual aspects of positive de-Sovietization in Lithuania: (1) a transition from the didactic realism of the Soviet era to explorations of symbolism and conceptual expression; (2) the integration of state, national, and religious motifs; and (3) visual narratives emphasizing the struggle for freedom and independence. These developments demonstrate how aesthetic practices act as a mirror to social and political change—moving from ideological prescription to pluralistic imagination.

Thus, the post-Soviet monumentscape emerges as a dynamic field where visual forms become agents of meaning, mediating between history and contemporaneity. The evolving visual vocabulary of Lithuanian monuments not only redefines the aesthetic order but also articulates the moral and political consciousness of a society still negotiating its past—proving that even in stone and bronze, dialog, reflection, and reinvention persist.

Funding

This project has received funding from the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT), agreement No. S-PD-24-47.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Interviews with Sculptors and Architects:

- Mindaugas Šnipas (1 July 2025)

- Rūta Trimonienė—wife and archivist of the late sculptor Jonas Jagėla (2 July 2025)

- Gintaras Čaikauskas (3 July 2025)

- Klaudijus Pūdymas (21 July 2025)

- Arūnas Sakalauskas (24 July 2025)

Previously conducted and publicly available interviews with sculptors:

- 6.

- Regimantas Midvikis (deceased)

- 7.

- Vytautas Kašuba (deceased)

- 8.

- Konstantinas Bogdanas (deceased)

- 9.

- Romualdas Kvintas (deceased)

- 10.

- Daliutė Ona Matulaitė (deceased)

- 11.

- Tadas Gutauskas

- 12.

- Gediminas Jokūbonis (deceased)

- 13.

- Vladas Vildžiūnas (deceased)

- 14.

- Alfonsas Ambraziūnas (deceased)

- 15.

- Algimantas Nasvytis (deceased)

- 16.

- Antanas Bagdonas (deceased)

- 17.

- Kęstutis Patamsis (deceased)

- 18.

- Gediminas Piekuras

- 19.

- Antanas Bosas

Notes

| 1 | In this context, it is important to emphasize that when discussing representations reflecting the canons of the socialist regime, the focus is primarily on the “plan of monumental propaganda” and the monuments that emerged within its framework, commemorating specific historical figures, events, and the like. These monuments are typically characterized by figurative expression in line with the socialist realist canon, with monumental propaganda continuing up to the Sąjūdis period (Grigoravičienė). Adhering to this perspective distinguishes this group of monuments from, for example, the decorative sculpture actively developed during the Soviet period, which featured more abstract, diverse forms of expression and sometimes employed a euphemistic visual language. |

| 2 | The research focuses on monuments characterized by long-lasting expression, i.e., made of granite, concrete, and similar materials, located in public spaces in Lithuania, such as city and town squares and other public areas. It does not include martyrological sites (monuments marking places of death, burial, or execution) or monuments situated in cemeteries, churchyards, forests, stadiums, sculpture parks, homesteads, or private or enclosed courtyards. Additionally, wooden monuments, crosses, roofed pillars (Lithuanian: stogastulpiai), chapel pillars (Lithuanian: koplytstulpiai), commemorative stones, standardized memorial markers, and memorial plaques are excluded from the analysis. |

References

- Gabowitsch, M. What Has Happened to Soviet War Memorials Since 1989/91? An Overview. Politika. 2021. Available online: https://www.politika.io/en/article/what-has-happened-to-soviet-war-memorials-since-198991-an-overview (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Ehala, M. The Bronze Soldier: Identity Threat and Maintenance in Estonia. J. Balt. Stud. 2009, 40, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehti, M.; Jutilaand, M.; Jokisipila, M. Never-Ending Second World War: Public Performances of National Dignity and the Drama of the Bronze Soldier. J. Balt. Stud. 2008, 39, 393–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldmann, N. Local Memories Dismantled: Reactions to De-communization in Northern and Western Poland. Cult. Hist. Forum 2018, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Belavusau, U. The Rise of Memory Laws in Poland. An Adequate Tool to Counter Historical Disinformation? Secur. Secur. Hum. Rights 2018, 29, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalov, M. When Lenin Becomes Lennon: Decommunization and the Politics of Memory in Ukraine. Eur.-Eur.-Asia Stud. 2022, 74, 709–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betlii, O. The Identity Politics of Heritage Decommunization, Decolonization, and Derussification of Kyiv Monuments after Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine. J. Appl. Hist. 2022, 4, 149–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlasenko, Y.; Ryan, B.D. Decommunization by Design: Analyzing the Post-Independence Transformation of Soviet-Era Architectural Urbanism in Kyiv, Ukraine. J. Urban Hist. 2022, 50, 247–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricci, A. Radicalizing Memories in Times of War: How Latvian Parties Narrated the Soviet Monuments’ Question after the Russian Invasion of Ukraine. J. Balt. Stud. 2024, 56, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrejevs, D. Where the Aura of a Tyrant Remains’: Absent Presence and Mnemonic Remains of Socialist-Era Monuments. Natl. Pap. 2024, 52, 1042–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beržiūnas, V. The Creativity of Monuments: The Case of Bistable Belarusian Identity. Creat. Stud. 2025, 18, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spake, W. Among the Steppes: A Societal Study of the Soviet Past in Kyrgyzstan. Alexandrian 2018, VII, 1–21. [Google Scholar]