Abstract

St. Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church and churchyard, Toxteth, Liverpool, UK, is the focus of community efforts to research and conserve the heritage asset, and archaeologists at the University of Liverpool were invited to contribute their expertise to co-produce new understandings of this locally significant place. Roman Catholic vault burial in Britain has not previously been archaeologically investigated, and the use of rock-cut burial pits, visible in the churchyard, appeared to be a response to the massive demand for urban burial during the nineteenth century. The project has combined local knowledge with surface survey and recording memorials in the churchyard, mapping the crypt and recording the interior of the four vaults at the western end of the crypt after they had been temporarily opened by the community volunteers. This enabled standard and photogrammetric recording, and PXRF analysis of the in-situ coffin fittings. No human remains were revealed. Interviews with volunteers and key stakeholders at the church provided the community’s voice, presented here. This project demonstrates how collaboration enables the skills and abilities of specialists, students and the local community to combine to create new knowledge and enhance public understanding of local heritage, with academically important and locally empowering results.

1. Introduction

Community archaeology is now expanding to include more co-production of knowledge [1,2,3] rather than top-down, enabling the primary task of training and raising public awareness of heritage. This project, investigating the burial and commemorative practices of the Roman Catholic population served by St. Patrick’s Church, sits within the wider ambitions of citizen science, comprising elements that are collaborative and others that are co-created [4]. Each project should create distinctive dynamics in each context as the varied interests and desires of all stakeholders develop regarding the heritage research and management. This project is one form of public archaeology [5] which considers a democratic approach, where different actors can ‘develop their own enthusiasm’ [6], but there is also recognition that some forms of fieldwork and analysis require professional training and use of technical equipment, and so the project combines several of the types of public archaeology [7].

The Toxteth area of Liverpool lies beyond the city centre, and it is an area that includes dense working-class housing, which has had a history of deprivation but also of strong community feeling. Within this setting, the Roman Catholic church of St. Patrick’s is one of the most prominent and architecturally significant buildings in the area, and it has statutory protection having been classified as a Grade II listed building [8]. Discussions regarding diocesan reorganisation and rationalisation of places of worship meant that St. Patrick’s was one of the buildings under consideration for reuse, as its congregation no longer filled the building, and it required considerable investment to conserve its somewhat neglected structure. The local response was to raise funds for the immediate conservation requirements and commence volunteer enhancement of the building and its churchyard to complement ongoing historical research into the church, its priests and its congregation [9]. The University was contacted to see if any expertise could be provided to increase understanding, both for its own sake and to provide additional information on its heritage significance to assist with grant applications.

The archaeologists invited to investigate St. Patrick’s recognized the opportunity for the first examination of English nineteenth-century Roman Catholic vault burial practices through survey, thus providing important comparative evidence to set against the already-recovered evidence for the practices of various Protestant traditions. The research design focused on the material evidence of burial practice, setting this in the physical context of interior and exterior space (the crypt and the churchyard, respectively), with the principal purpose of examining the combination of intramural and extramural nineteenth-century Roman Catholic mortuary traditions for the first time in England. The field research methods combined cartographic and documentary sources with archaeological mapping and photogrammetry, standard memorial recording procedures, and recording of the burial vaults and their contents using non-invasive techniques. This has assisted with community understanding and affected their investigative practices and is also informing ongoing management and conservation planning for the building and the churchyard.

This paper outlines the multiple strands of collaboration and co-production that made this heritage asset better known to the University’s students, the local community, the managers of the building and site, and the academy. This understanding of the site and its history has been increased through the collaboration, and the community volunteers should be seen as co-producers of knowledge in the overall project. This paper largely concentrates on the archaeological contribution, which presents for the first time the range of burial and commemorative practices at a 19th-century Roman Catholic church and churchyard in England, but the ways in which this understanding enhances the community’s appreciation of the heritage has been presented in the volunteer interview data.

2. Historical Context

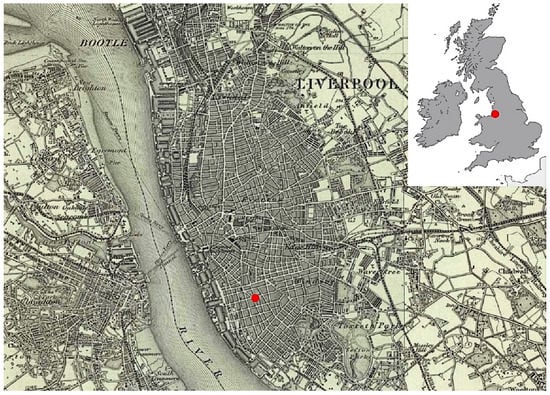

The Roman Catholic population of Liverpool grew during the early nineteenth century from over 21,000 in 1811 to an estimated 50–60,000 by 1830 [10]. Some were able to become successful merchants and businessmen as the city grew with the development of international trade, as first canals and then railways enabled the products of the industrial revolution to reach the docks to be exported across the globe. The typical mix of sophisticated Georgian town houses and slums (with a regional form comprising court housing) spread out from the small historic core of Liverpool, and districts such as Toxteth provided the housing needed for the rapidly growing population (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location map of St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Church, Toxteth, Liverpool, using the 1896 OS one inch to the mile map.

Burial for Roman Catholics in Liverpool was limited, and so once the church and its limited graveyard became available it was intensively used. Prior to this, all Catholics were interred without a service in Anglican churchyards or the Parochial Cemetery of St. Mary’s, except for the few after 1813 who could be interred with a service by a priest in St. Nicholas’ churchyard on Copperas Hill. The opening of St. Patrick’s in 1827 was, therefore, an important addition to the options for Catholics (together with St. Peter and Paul in Crosby in 1826), though two more Catholic churchyards opened by 1842.

Burial at the site continued until an 1854 Order of Council, for which provision was made under the 1853 Burial Act, as this prohibited most intramural burials in Liverpool. It was ordered that all burials in the churchyard of St. Patrick’s, as well as under the chapel, were to be discontinued [11]. It was only with the opening of the Roman Catholic Cemetery at Ford in 1859 that pressure in Liverpool began to ease on burial provision.

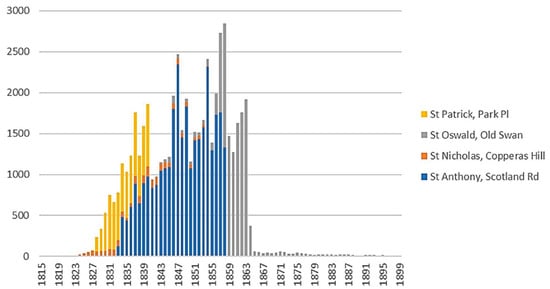

Burial registers for the church survive but they are incomplete, and are only extant for the years 1827–1841, meaning that there is no record of the burials that took place from that point until 1854. This gap in burial registers unfortunately leaves us without a definitive sense of the demand on burial provision after 1841, nor the impact of the Irish Famine and subsequent devastating epidemics. However, using burial registers from contemporary churchyards in Liverpool, we can confidently assume that the numbers of burials at St. Patrick’s continuously rose, with a peak in 1847 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Bar chart of burials per year in selected central Liverpool Roman Catholic churchyards based on extant burial register data. No data survives for St. Patrick’s after 1841; the drop in burial for all churchyards follows the prohibition of burial except in existing family plots in a few sites.

The situation only a few years before the prohibition of burial within the church is indicated by the report by the newly appointed Medical Officer of Health, which states that St. Patricks’ was one of seven Liverpool burial grounds where pits were used: ‘The pits vary in depth from 18 to 30 ft, being 7 to 12 ft long and 3½ to 9 ft wide. The number of bodies deposited in such pits varies from 30 in St. James and St. Mary’s cemeteries to 120 in St. Patrick’s’ [12].

The church has continued as a place of worship to the present; physical changes over time to the worship space of the church have not been recorded in this project.

3. Architectural Context

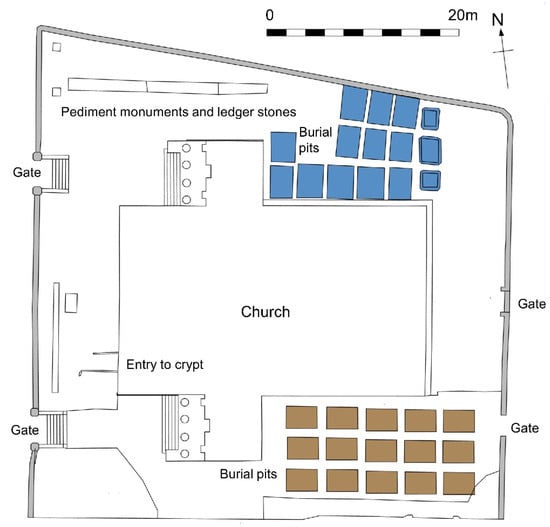

The church was designed by John Slater and was built between 1821 and 1827, a substantial building on a prominent rise with an impressive four-bay west front with wings fronted by Doric tetrastyle porches facing the road [6]. The interior includes a substantial gallery on three sides. The church is surrounded by a small churchyard. Most of the area south of the church has now been covered in tarmac and converted into a car park and main means of access to the building, though subsidence still indicates where some of the burial pits were located, and the paths shown on the nineteenth-century maps are no longer visible except from the access gates on Park Place to both sides of the church (Figure 3 and Figure 4).

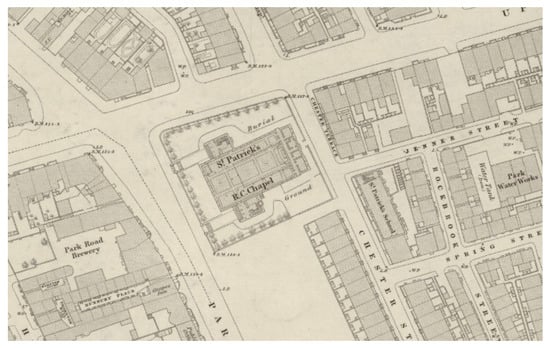

Figure 3.

Ordnance Survey map of St. Patrick’s Church, surveyed 1849, when the churchyard was still in use for burial. Liverpool town plan. Accessed via National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/view/229948173 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

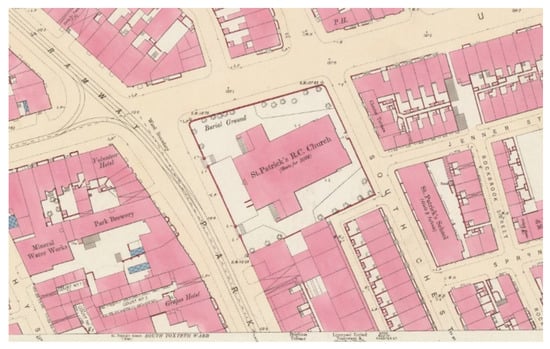

Figure 4.

Ordnance Survey map of St. Patrick’s Church, surveyed 1890, when the churchyard was closed to new burial. Lancashire Sheet CXIII.2.4. National Library of Scotland https://maps.nls.uk/view/229949105 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

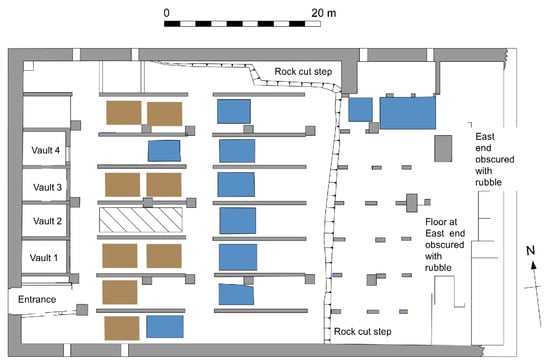

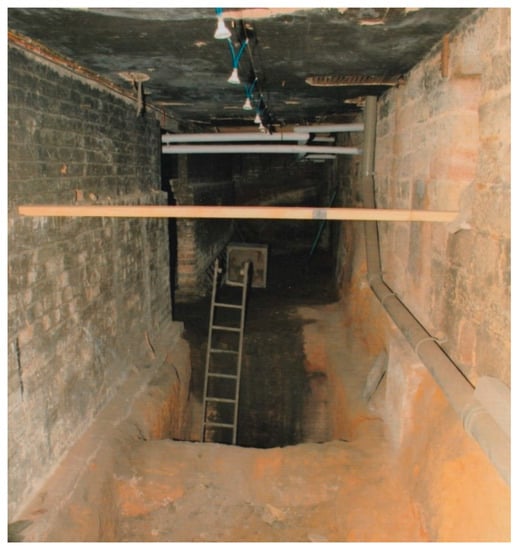

The church was designed and built with a large crypt, with the vaults constructed against the west wall, adjacent to the entrance with its massive iron door, and partially rock-cut at the eastern end. The entrance to the church is at ground level on the southern side, but the sloping ground means that the entrance to the crypt on the west wall is also at ground level.

The four vaults in the crypt were not constructed as part of the original design of the building, but they were added, the first by the parish for its clerics, the others by affluent local families, though all before the opening of the church, based on the date of 1828 on the door of Vault 4. Barrel-vaulted chambers were built against the west wall, butting up to the brick piers that comprised part of the structural support for the nave above. Whilst there are many similarities between the vault designs, each has some distinct features and, as with other English burial vaults [13], each has their own biography, but these have never been integrated into any architectural description of the building.

3.1. Surface Survey of the Churchyard

The churchyard of St. Patrick’s is a restricted area with maximum dimensions of 50 m east–west and 49 m north–south, much of which is taken up by the church itself. The various sources reveal a landscape which was transformed on several occasions. In 1849, the in-use burial ground is shown to both the north and south of the church, with small bushes round three sides of the perimeter (Figure 3). The now-demolished oratory at the east end of the church is defined in considerable detail. By 1890, only some of the bushes were present, though some of the burial areas were now partially planted (Figure 4). In both maps, there is no indication of the burial pits, and these and family burial plots are only first recorded in a schematic manner on an architect’s plan of the 1970s. A detailed modern plan was therefore necessary for both research and management purposes.

The burial ground and church exterior were surveyed by total station theodolite (TST) and some taped measurements to create a record of the location of burial pits and other monuments in relation to the main church building and the boundaries of the property. The surveys were downloaded from the TST as DXF files, the point data imported into AutoCAD and lines joined from key plans made in the field (Figure 5). A drone survey was also undertaken to record the church and graveyard by 3D photogrammetry, and the historical dimension was considered using vertical aerial photographs and historic Ordnance Survey maps.

Figure 5.

Plan of St. Patrick’s Church and churchyard, 2022, showing identified (blue) and inferred (brown) burial pits.

3.2. Survey of the Crypt—Methods and Results

The crypt survey was undertaken by a combination of direct taped measurements within a framework of TST points taken without the use of a reflecting prism. The overall framework of TST points enabled a cross-check of taped measurements and helped to tie together the taped points. The taped measurements were essential in the cramped confines of the eastern shelf—but here again, a series of key points established by TST created the framework to fit in the taped measurements.

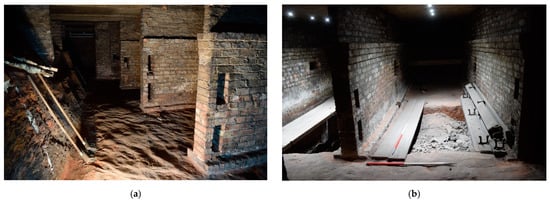

The crypt took the form of a large rectangular room around 18 m × 30 m in size, partly cut into the sandstone bedrock to the east creating irregular walling and uneven, stepped floor, with the remainder built up with sandstone foundation walls topped with brick on this sloping site. It occupied much of the footprint of the brick church above (Figure 6). Entered by a heavy iron doorway on the west side, the interior was divided into a series of eight east–west passages by brick walls that supported the joists of the main body of the church above. Two cross-passages running north–south created further subdivisions. In places, the passage walls had rectangular slots in pairs which may have been used to divide off areas of the crypt, probably to manage access to the burial pits (Figure 7a). Along the western side was a series of brick-built burial vaults which were built between the passage walls. To the south was a row of three sealed vaults, their brick frontages marked with a cross in relief by projecting bricks, and then a further vault which was sealed with a heavy cast-iron door. A limited photographic survey of the frontage of the vaults was undertaken in September 2022, after the openings into the vaults had been reinstated; this was used to create a 3D model of the vault frontage using Metashape software Standard version 1.8.4 (Figure 8).

Figure 6.

Plan of St. Patrick’s Church crypt indicating its structural features, burial vaults and rock-cut burial pits.

Figure 7.

(a) Brick passage walls with pairs of rectangular slots in St. Patrick’s Church crypt. (b) An unexcavated rock-cut pit between the passage walls in St. Patrick’s Church crypt.

Figure 8.

Photogrammetric image of the burial vaults in the crypt after the entrance blockings had been reinstated, with Vault 1 on the far left and Vault 4 with the cast iron door on the far right.

At the eastern end of the crypt, the sandstone bedrock was at a higher level and had been cut to create a level shelf, with only a narrow gap between the church floor joists above and the bedrock. This was difficult to access and examine in detail while the presence of much collapsed rubble and walling made the eastern end partly inaccessible. The origin of this rubble was probably the demolished sacristy that had been removed from the eastern elevation of the church. The passage walls were two bricks thick at the base, rising to a stepped spreader course and topped by a wall a single brick thick. Between the cross-passage walls was a series of burial pits, cut vertically into the bedrock floor (Figure 7b). They vary in size, but average about 2.3 m × 1.5 m in plan, though some require more clearing of loose material on the crypt floor to confirm their detailed dimensions. The depth of the pits is unknown, and more pits may be found as rubble is cleared from the crypt floor; one subsurface brick vault 5.3 m × 1.6 m in plan has now been identified in the crypt. Two further burial pits were discovered cut into the bedrock of the raised shelf to the east, where access must have been gained through the wooden church floor. A shallow curved brick floor is likely to be the roof of a further vault cut into the bedrock.

Several of the rock-cut pits were partially cleared out by the church volunteers (Figure 9). Their fills comprised cinders, probably from the boiler located in the crypt, as well as general rubbish, including discarded hymn and prayer books, newspapers, cigarette packets and other rubbish including fragments of the original altar rail, suggesting a clearance of materials of a range of dates, perhaps in the 1970s.

Figure 9.

One of the burial pits, partially emptied by community volunteers, in St. Patrick’s Church crypt.

Only two mortuary-related items were found in the pits. One was a fragment of coffin fitting (a copper-alloy cross that would have been placed on the lid) and the other a damaged slate memorial; a hole in the slab corresponded with a fragment of slate still attached to the south wall of the crypt interior, indicating where it had one been placed. No human remains have been recovered from the pits thus far, suggesting that the pits were probably emptied soon after Ford cemetery opened, when the charnel could have been reburied there.

3.3. Recording the Vaults and Identifying Individuals Interred

The recording of vaults beneath churches within Britain has taken place in advance of clearance, notably at three churches in London at Spitalfields [14], St. Luke’s, Islington [15] and at St. George’s, Bloomsbury [16], or as non-interventionist observational studies [17,18,19,20]. The project at St. Patrick’s belong to the latter, but more methods have been applied to the recording than previously, as recent innovations in recording have enabled fuller contextualisation of the evidence, even though no coffin could be moved. Archaeological research to date has created an understanding of mortuary practices within vaults, both those for families and larger parochial vaults and reveals varied patterns of use and management [13], though only in Protestant contexts in Britain. The large crypt area of St. Patrick’s was not used for parochial above-ground interment, but smaller vaults were constructed within the crypt space.

Each brick-lined vault at St. Patrick’s was recorded using tape measurements with sufficient reflector-less TST readings to integrate with the main crypt plan. Each coffin within the vaults was recorded using a standard record form and measurements were taken where possible for the outer wooden layer of what were, in nearly all cases, triple-shelled (layered) coffins, with a wooden outer and inner coffin and a lead intermediary layer. The positions of coffin fittings were marked on the record sheets, and coffins and their fittings were digitally photographed. In some cases, the fittings included inscribed breastplates that recorded the biographical details of the deceased. These are important in archaeological analysis, but also of great significance to the local community and the church congregation. The vaults were photographed to enable photogrammetric modelling, and all accessible fittings and the lead lining layer of the triple-shelled coffins was tested using PRXF (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Taking PXRF readings on the lead lining of the coffins and on the coffin fittings in the St. Patrick’s Church crypt vaults.

Three of the vaults were designed with entry points which were blocked up when no interment was being made, but these blockings were removed by the community volunteers and the archaeologists non-invasively recorded the vaults and their contents (Figure 11a,b and Figure 12a). The fourth vault can be accessed through a cast iron door and had been previously entered. It was archaeologically recorded in the same way as the others, but the contents had been more disturbed with some movement to reveal and open a lower chamber marked by two slabs with iron rings in the vault floor (Figure 12b). No details of any contents of the lower space were recorded when this took place, at a time before archaeological involvement.

Figure 11.

(a) View of Vault 1 containing coffins of priests and a Christian brother; (b) View of Vault 2.

Figure 12.

(a) View of Vault 3 containing coffins of the Bury family; (b) View of Vault 4 belonging to the Roberts family.

The details of the vaults and their significance as examples of nineteenth-century English Roman Catholic mortuary behaviour will be published elsewhere. Here, the heritage significance of the vaults and their contents primarily resides in the identification of the families that occupied them. The parish wished to be able to honour named individuals, and the vaults offered this opportunity, whereby the physical evidence of the coffin and nameplate gave an identity to individuals to a far greater degree than any entry in the burial register. Some individuals were identified by their name plate, but others from the same family were recognised through their burial register entry that noted a vault burial. Vault 1, in the most prominent location next to the entrance to the crypt, contained the coffins of four parish priests and a Christian Brother. A stone plaque with the names of three of the priests who died during the typhus epidemic of 1847, and another commemorating Brother Maher who died the year previously, are placed on the side wall of the vault, easily noted by anyone entering the crypt (Figure 13). Name plates on two of the coffins in Vault 3, to Jane Bury (died 1839) and Thomas Bury (died 1847), indicate the family owning that burial space. Vault 4 was built for the Roberts family, with the coffin name plates for Peter Reynolds (died 1828) and Richard Roberts (died 1831) identifying some of those interred there. Ongoing documentary research may enable more individuals who were placed in these vaults to be identified. This recovery of names, and linking them to specific burial locations, is of special significance to the St. Patrick’s community.

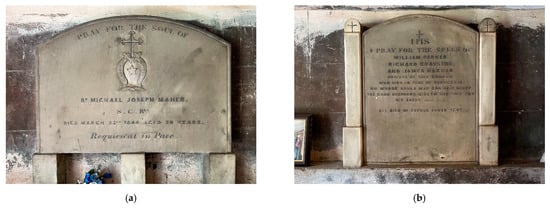

Figure 13.

(a) Wall-mounted memorial in the crypt to Brother Michael Joseph Maher (died 1846); (b) Wall-mounted memorial in the crypt to three priests at St. Patrick’s who died in the Typhus outbreak in 1847.

The four vaults had no memorial plaques on the walls which provided their access points, but the photogrammetric survey of this elevation (Figure 13) reveals clearly how each vault was individually designed and constructed, with each access point differing in size and form of lintel. Only Vault 4 was designed with a full height doorway and sealed with a cast iron door. The others were all accessed through a window-like aperture that was bricked up between interments. This lack of standardisation indicates that each vault was designed and built separately, and the small number of family vaults suggests only a tiny minority of the congregation could afford such interment options.

4. Results from Memorial Recording

A small number of memorials are still in situ in the churchyard, but many have been displaced and laid down in stacks with, at best, the topmost visible; many others are probably completely buried, and a few have been moved into the crypt. Memorials, however, always represented a tiny minority of those who were interred at the site. The churchyard was the scene of intense burial from 1828 until 1854, and further research will explore how this could have been achieved. In only the first 14 years that the churchyard was open, 7466 individuals were buried on the site. The state of local living conditions is revealed in the high incidence of infant and child deaths, with 2763 (37%) under two years of age and a further 1644 (22%) between two and six years old. The average age at death, including infants, was only 18 years old, but for those who survived beyond the age of six the average age at death was 41 years old. It is interesting to note that the average age of those commemorated on the memorials had the equivalent values of 30 and 39 years old, respectively, suggesting that the more affluent, who could afford a memorial, had no longer life expectancy than the average in Toxteth.

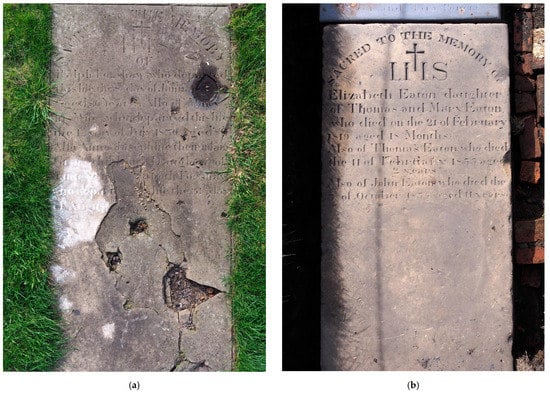

The survey has enabled those memorials permanently visible to be recorded, using a standard methodology [21,22]. Some others were only uncovered for a short time by the community volunteers and then were similarly archaeologically recorded prior to being placed back in the ground as there is insufficient space at present for them all to be permanently displayed. It is notable that some of those slabs that had been buried were in a much better state of preservation than those that had been exposed since their erection, indicating the level of erosion in this urban environment (Figure 14). More memorials lie beneath the surface in some parts of the burial ground and some of those already recorded lie on top of more than one more layer of slabs, but it was not safe to uncover them; their presence, however, suggests that a significant area of the burial ground may have been covered with such slabs, at least in the areas without burial pits.

Figure 14.

(a) Stone ledger that has been exposed since its erection and is suffering erosion. (b) Stone ledger which was buried and is still well preserved.

Although the sample is small (19 external memorials with legible inscriptions and eight more in the crypt) there is sufficient to consider the types of monument that were being erected, their geology, and the forms of inscribed text and motifs carved on them. There is also a transcription of some burial monuments that was undertaken before many were moved [23] which correlates with some of the known memorials but also provides information on others that are either buried or which have been lost.

As the monuments at St. Patrick’s are relatively early Roman Catholic memorials in an urban English context, they provide a valuable insight into the similarities and differences with the majority Protestant memorials that were erected in Liverpool in the early nineteenth century, and they can be compared with contemporary Roman Catholic memorials commissioned in large numbers in Ireland. Two were small pedestal monuments, the most elaborate memorials in the burial ground, remaining in situ close to the boundary and visible from the main road. Much of the remaining area where memorials were allowed would have been covered with the ledger slabs, but some headstones survive because they have been moved into the crypt. These show the same symbolism as the ledgers but, as is so often the case elsewhere, they can have further elaboration [21,24]. The headstone for Thomas Maguire (died 1846) has a horizontal top, but it has incised a more elaborate shape which encloses the IHS set within the top of the design (Figure 15a). This shape forms the headstone profile for John Rooney (died 1841) and Mary Moran (died 1844, Figure 15b) and is a shape found across northeast Ireland, used by both Catholic and Protestant communities.

Figure 15.

(a) Headstone for Thomas Maguire (died 1846); (b) Headstone for Mary Moran (died 1844).

The introductory terms on the memorials reveal a traditional attitude with several emphasising the burial location. Thus, the inscription for Elizabeth Bunbury (died 1846) starts with ‘Here lie interred the mortal remains of’; Mary Anne Turnbull (died 1847) ‘In this tomb are interred the remains of’. Perhaps because the ledger slabs covered the whole grave, presumably a rock-cut shaft, and were designed to prevent the reuse of the grave, a mention of the tomb is particularly significant, as is an explicit statement of ownership of the burial plot, which could also be noted at the foot of the stone, as with ‘The burial place of Thomas Macguire’. This ownership claim is commonly found in contemporary Irish memorials, but it is also relatively common for ledger stones in Britain. As with the vaults, the finding of memorials with named individuals commemorated created a greater level of empathy and significance for the community volunteers than the names only in the burial register; the materiality of the ledger stones reinforced the personhood of these deceased individuals and highlighted their names in the minds of the community, and whether they were still over that burial or not was not the highest priority.

Catholicism is demonstrated through two aspects of the inscription and decoration. The feature that was consistently used and which at the time was an explicit Roman Catholic symbol (though later it became popular in Protestant Anglican contexts with the rise of Anglo-Catholic liturgy within that denomination) was the IHS abbreviation, with a cross extending up from the cross bar of the H. In Ireland, many variations in the details of the IHS can be found, but here the monogram is relatively consistent, though one is more elaborate (Figure 16). The other aspect is the use of ‘Requiescat in Pace’ (for one person) or ‘Requiescant in Pace’ (for more than one individual). This phrase, ‘Rest in Peace’, is usually carved at the bottom of the memorial at St. Patrick’s and was also very common on Irish memorials in this location.

Figure 16.

The IHS monogram on stone ledgers in St. Patrick’s churchyard.

5. Community Perceptions—Evidence from Interviews

To evaluate community actors’ motivations and reactions to the archaeological investigations at St. Patrick’s, structured interviews were conducted with those prepared to take part. Most of the core community members were interviewed, and five responses are considered here. The responses are anonymous, and all participants were given an information sheet and signed a consent form to take part and agreeing to their responses being used in research and presentations. The sample size is significant in relation to the number of local people committed to contributing their time and effort to conservation and maintenance but can only be used to indicate the range of motivations and perspectives that are relevant at St. Patrick’s; not all volunteers agreed to or were available to take part in this survey.

The volunteers have different motivations but have a love for the building and their area, and whilst most are Roman Catholics, not all are. Some have been working on the site for years “20 years ago I came to this church with the missionaries’ charity… the church was looking a bit sad and lonely and very, very, unkempt… and I said, ‘you want me to do something with this wall’ and he went ‘if you like!’… there is not much I haven’t touched in this church, and in the gardens as well”. Others have joined quite recently: “It was August last year, we were just actually passing, we were walking past, and the crypt doors [were] open, and we were just fascinated… and we spoke to N [who] showed us around the crypt and that was it then… they were desperate for volunteers here, so, the following week we were back again, just helping”.

Community projects enable different actors to bring their own skills and interests to the enterprise: “The heritage that I’m doing at the moment is the lifting of the gravestones and preparing the burial pits for…well you people, who were coming, so we moved all the debris”. The excitement of discovery is also palpable in the responses: “looking into the history of it and then going outside, looking at the graves, and then, we just did a bit of digging, and that was it; we found more and more and then it was just amazing, you know the feeling of finding this, and some of the graves which are dated after. 1841… we are finding out other people who were actually buried here where there [were] no records of them”. Both these responses indicate that the materiality of the heritage—such as memorial stones or burial pits—engages the emotions more than documents, though they are also important. The names of the deceased are central in most responses: “every grave has got a story behind it… the names can live on, you know, the names don’t have to be in the past so that’s very important”. The wall tablets to the religious figures (Figure 12) are significant because they draw attention to the deaths of those who died in the service of the parish, particularly those who died from typhus whilst caring for their flock: “downstairs in the crypt we’ve got the martyred priests who paid the ultimate price: they went to the homes of the famine or the typhus victims, contracted it, and paid the ultimate price themselves. So, a lot of respect should be given to the men of the cloth for what they do, so that’s very important”.

The involvement of the trained archaeologists has also motivated and modified some of the activity, and is seen as a positive change: “it would just be nice to be able to prove that there are people here besides the priest and the other people in the crypt, that there are people out there buried,” often linked to the need to respect any disarticulated skeletal remains in the gardens “the archaeologists are such a breath of fresh air to what we’re doing because we’re not specialists… we’ve discovered bones and stuff you know, and… from a respectful point of view, we’ve stopped digging”. There was already concern over the human remains, but the archaeological ethics have combined with the religious attitudes to create a respectful environment: “these people who suffered in such a way can now be remembered and rededicated if you like in prayer”.

This project is an example of community archaeology where the specialists collaborate with already active local people, rather than initiating a project. The existing activity already provides some of the positives ascribed to community archaeology and engagement with local heritage [5,25], but the archaeological input enriches and consolidates these benefits and provides additional validation for the volunteer efforts. The archaeological component does not involve joining together in the fieldwork but rather sharing tasks (such as the volunteers preparing the churchyard for survey and lifting the buried stone ledgers for recording by the archaeologists) and sharing results and perspectives on the burial registers and other archival sources, as well as communal efforts to reveal pits in the crypt. The design of the archaeological fieldwork has including undertaking what is important for the community to know, as well as what would be the highest priority from an academic perspective, and the findings will be presented locally in a form that gives greatest attention to those aspects that interest the community.

The community efforts, and the combination with specialist fieldwork and analysis, creates a complex web of evidence and understanding which different actors use for their own purposes. Some of this selection is conscious, but other aspects relate to subconscious selective remembering and utilisation to support or refute an existing or desired narrative. This is likely to apply to the academic as much as the community actors, and the former must remain alert to selective prioritisation of archaeological knowledge over that from other sources. Sensitive collaboration and co-production projects enable academic researchers to appreciate other perspectives and priorities and to recognise the multiple agencies and perceptions in the present, just as we attempt to recover these multiple strands in the past.

6. Conclusions

The heritage outputs from the collaboration are tangible and significant. St Patrick’s Church is an architecturally notable building with enhanced heritage value because of its association with the development of a parish infrastructure as the Roman Catholic Church and its adherents became established within the social, economic and architectural landscapes of Liverpool [8,9]. The scale and architectural quality of St. Patrick’s demonstrated the material success of some Roman Catholic families, but also the local recognition that the largely poor, mainly Irish immigrant population in Toxteth deserved an appropriate place of worship and a focus for their identity. The architectural style of St. Patrick’s sits well within the first major phase of church building following the passing of the second Catholic Relief Act in 1791 but reflects what was seen as growing confidence by the 1820s in the street-facing façade and the scale of the building [26,27]. The survey of the crypt, an element of the building not previously considered by architectural historians, reveals how the slopes on the site were used to advantage to make the building highly visible from the street, but also demonstrates how the crypt could support an effective seating area at ground level and space for storage and burial below. Given the restricted plot on which the church and burial ground sits, this crypt area was a significant additional space for interment.

The survey of the burial pits within the crypt and in the churchyard, and the recognition that more of these exist under the car park area of the churchyard, indicate a continuing problem for many urban churches in the nineteenth century in dealing with the numerous interments required each year [28,29]. Archaeological evidence of the rock-cut pit form of management of mass interment has not been recovered previously, and it will require further investigation. The small number of family vaults reveals a strong class distinction between the tiny minority affluent enough (or in the case of the priests, sufficiently revered) to have private burial spaces defined by role or family; a small number had external individual graves with memorials, but the vast majority were interred together in the rock-cut pits. The excavations at the burial ground of the Catholic Mission of St. Mary and St. Michael, Tower Hamlets, London, revealed a well-organised system of grave digging with graves up to 4 m deep with coffins of adults at the bottom, those of adolescents higher up and with infants on top [30,31]. The survey of the pits at St. Patrick’s will now be combined with ongoing analysis of the burial registers to calculate the limited options for burial on the site. The organisation of communal burial seen at the Catholic Mission of St. Mary and St. Michael must have been paralleled in some way at St. Patrick’s, as for most years where the burial registers survive, over 500 interments took place every year. The family vaults revealed some named interments, which was significant to the local community, but academically their value lies in providing an insight into the relatively small number of Roman Catholic families who could afford a family vault. As with the memorials, many attributes of the coffins and fittings can be paralleled with those from Protestant contexts but there are also some differences in the selection of coffin lid motifs, notably the use of the cross on some of the designs, notably in Vault 4.

The memorials at St. Patrick’s reveal how Roman Catholic commemoration in England had many similarities with contemporary Protestant practice, but there were some distinct differences in phrasing and iconography that emphasised alternative theological priorities. That these can be paralleled in Ireland reflects both the same denominational distinctions but also that many of those being commemorated were first- or second-generation immigrants from Ireland and they may have influenced the design and content of the memorials.

This open access publication is just one way in which the project will more widely disseminate knowledge: “other parishioners… were unaware of the history that is now being uncovered… I’m hoping… your findings… will all come out for everyone to see, you know”. A half-day event with talks and tours, and the creation of posters for the refreshments room at the church will also cement the co-produced knowledge and understanding within the congregation and the wider local population. The results of community projects require open dissemination otherwise the collaborative activities are not followed through to accessibility of the knowledge thus generated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, H.M. and R.P.; data curation, H.M. and R.P.; funding acquisition, H.M.; investigation, H.M., R.P., A.F.N., E.B. and N.D.; methodology, H.M. and R.P.; project administration, H.M. and R.P.; supervision, H.M., A.F.N. and R.P.; validation, H.M., R.P., and A.F.N.; visualization, H.M., E.B., A.F.N. and R.P.; writing—original draft, H.M., R.P. and A.F.N.; writing—review and editing, H.M., R.P., A.F.N., E.B. and N.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The University of Liverpool funded two Undergraduate Research Scheme placements, and two Graduate Research Internships (E.B. and N.D.) who took part in this project, and the Department of Archaeology, Classics and Egyptology provided the necessary technical and logistical support for all stages of the project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

All community interviewees read and signed an information and consent form. The structured interviews took place in private within the premises at St Patrick’s, with questions set by H.M. and with E.B. and N.D. present. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed by N.D. and once the transcriptions were checked the recordings were deleted. Only fully anonymised transcripts are placed in the project archive.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Our first thanks should be to the parish of St Patrick’s whose members have been so welcoming and invited us in to record the crypt and graveyard. They supported us logistically and with copious refreshments; their enthusiasm in uncovering and sharing the history of the church was infectious. Michael O’Neill shared his enormous knowledge of the church. University of Liverpool students Sarah Edmunds, Elinor Griffiths, Jasmine Murphy and Lauren Spencer assisted with the vault and crypt recording. Departmental technicians J.R. Peterson undertook the photography from which the photogrammetric modelling could be achieved, and P. Gethin undertook the PXRF analyses.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ancarno, C.S.; Davis, O.; Wyatt, D. Forging Communities: The CAER Heritage Project and the dynamics of co-production. In After Regeneration: Communities, Policy and Place; O’Brien, D., Matthews, P.P., Eds.; Policy Press: London, UK, 2015; pp. 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, S. Community archaeology. In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology; Moshenska, G., Ed.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, J.; Armstrong, J.; Curtis, E.; Curtis, N.; Vergunst, J. Exploring co-production in community heritage research: Reflections from the Bennachie Landscapes Project. J. Community Archaeol. Herit. 2022, 9, 196–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecker, S.; Haklay, M.; Bowser, A.; Makuch, Z.; Vogel, J.; Bonn, A. (Eds.) Citizen Science. Innovation in Open Science, Society and Policy; UCL Press: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, M. Bridging the Gap: Classification, Theory and Practice in Public Archaeology. Public Archaeol. 2017, 16, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holtorf, C. Archaeology Is a Brand: The Meaning of Archaeology in Contemporary Popular Culture; Left Coast Press: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Moshenska, G. Introduction: Public archaeology as practice and scholarship where archaeology meets the world. In Key Concepts in Public Archaeology; Moshenska, G., Ed.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2017; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Historic England 2001, Official List Entry 1365832, Chapel of Saint Patrick, Park Lane. Available online: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1365832 (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- O’Neill, M. St Patrick’s, Park Place, Liverpool: A Parish History, 1821–2021; Gracewing: Leominster, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, T. Catholic History of Liverpool; C. Tinling & Co., Liverpool: Liverpool, UK, 1910. [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous. Closing of Burial Grounds in Liverpool. Liverpool Mail, 11 March 1854; 6. [Google Scholar]

- Interments in Town. Liverpool Mercury, 21 September 1859; 6.

- Mytum, H. Burial Crypts and Vaults in Britain and Ireland: A Biographical Approach. Folia Archaeol. 2020, 35, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, J.; Adams, A. The Spitalfields Project. Volume 1—The Archaeology. Across The Styx, Council for British Archaeology Research Report 85; Council for British Archaeology: York, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle, A.; Boston, C.; Witkin, A. The Archaeological Experience at St Luke’s Church, Old Street, Islington; Oxford Archaeology: Oxford, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, C.; Boyle, A.; Gill, J.; Witkin, A. “In the Vaults Beneath”. Archaeological Recording at St George’s Church, Bloomsbury; Oxford Archaeology Monograph 8; Oxford Archaeology Library: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Litten, J. Tombs fit for kings: Some burial vaults of the English aristocracy and landed gentry of the period 1650–1850. Church Monum. 1999, 14, 104–128. [Google Scholar]

- Litten, J. The Anthropoid Coffin in England. Engl. Herit. Hist. Review 2009, 4, 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mytum, H. A newly discovered burial vault in North Dalton church, North Humberside. Post-Mediev. Archaeol. 1988, 22, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redknap, M. Little Ilford, St Mary the Virgin. Lond. Archaeol. 1984, 5, 31–37. [Google Scholar]

- Mytum, H. Recording and Analysing Burial Grounds Advice Documentation. 2019. Available online: http://www.debs.ac.uk/ (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Mytum, H. forthcoming. An international mortuary monument recording system—From site analysis to international comparative studies. In Critical Reflections on New Approaches to Historic Mortuary Data Collection, Analysis and Dissemination; Mytum, H., Veit, R., Eds.; Berghahn: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, J. Epitaphs and inscriptions on tombstones and monuments in Liverpool churches, chapels, churchyards and cemeteries 9, pp. 463–497, not dated. Transcriptions manuscript, Liverpool Record office 929.5 GIB.

- Mytum, H. A Comparison of Nineteenth and Twentieth century Anglican and Nonconformist Memorials in North Pembrokeshire. Archaeol. J. 2002, 159, 194–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reilly, S.; Nolan, C.; Monckton, L. Wellbeing and the Historic Environment; Historic England: London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Derrick, A. 19th- and 20th-Century Roman Catholic Churches. Introductions to Heritage Assets; Historic England: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Little, B. Catholic Churches since 1623: A Study of Roman Catholic Churches in England and Wales from Penal Times to the Present Decade; Robert Hale: London, UK, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Jupp, P.C. From Dust to Ashes: Cremation and the British Way of Death; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2006; pp. 19–45. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, R. Death, Dissection, and the Destitute; Routledge and Kegan Paul: London, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, N.; Miles, A. Nonconformist identities in 19th-century London: Archaeological and osteological evidence from the burial grounds of Bow Baptist Chapel and the Catholic Mission of St Mary and St Michael, Tower Hamlets. In The Archaeology of Post-Medieval Religion; King, C., Sayer, D., Eds.; Boydell: Woodbridge, UK, 2011; pp. 233–248. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, M.; Miles, A.; Walker, D.; Connell, B.; Wroe-Brown, R. ‘He being Dead yet Speaketh’: Excavations at Three Post-Medieval Burial Grounds in Tower Hamlets, East London, 2004–10; Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) Monograph Series 64; Museum of London Archaeology: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).